1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Universities worldwide have institutionalized end-of-course SETs as a primary feedback tool for quality assurance and faculty performance management (ASA, 2019). The intent is straightforward: gather student input to improve teaching and hold instructors accountable. However, a substantial body of research indicates that SETs are weakly related to actual student learning and are systematically confounded by factors unrelated to teaching quality (Flaherty, 2019). Students’ ratings tend to reflect grade expectations, course leniency, and instructor traits like gender or personality, rather than pedagogical effectiveness (Flaherty, 2019; ASA, 2019). Meta-analyses of multisection courses (where different instructors teach the same content and a common final exam is administered) find essentially no correlation between instructors’ SET scores and how much their students learn, as measured by objective outcomes (Uttl et al., 2017). In high-credibility studies with random instructor assignments, higher SET ratings even coincide with weaker performance in follow-on courses (Carrell & West, 2010; Braga et al., 2014). In other words, classes that students rate favorably may leave them less prepared for later learning—a troubling pattern suggesting that SETs capture short-term satisfaction more than long-term educational gain.

Students reliably reward delivery qualities that feel fluent and personable: instructors who are engaging, friendly, playful, or who use humor and story often receive higher ratings, even when these features do not translate into greater durable learning. Laboratory and classroom experiments demonstrate that polished, fluent delivery increases perceived learning without improving actual retention (Carpenter et al., 2013), that charismatic performance can elicit strong evaluations even when content is vacuous (Naftulin et al., 1973), and that brief “thin-slice” exposure to nonverbal warmth and expressiveness predicts end-of-term ratings (Ambady & Rosenthal, 1993). These findings caution that likeability and entertainment value can inflate SETs independently of pedagogical impact.

At the same time, both observational studies and experiments have demonstrated that SET results are biased against female instructors and instructors of color, even when actual teaching effectiveness is held constant (ASA, 2019; MacNell et al., 2015; Stark & Freishtat, 2014)). For example, one experiment found students gave significantly lower ratings to the same online instructor when told the teacher was a woman rather than a man (ASA, 2019). Such biases are substantial and not easily “averaged out,” calling into question the fairness of SET-based evaluations (ASA, 2019). Reflecting this evidence, many professional bodies—including the American Sociological Association—warn against using SETs as the sole or primary measure of teaching, since doing so can systematically disadvantage marginalized faculty and misstate true teaching performance (ASA, 2019). In sum, while student feedback is valuable, the validity of numerical SET metrics as indicators of genuine teaching effectiveness is highly dubious.

Beyond validity and bias, there is a category error in asking novices to summatively judge expert performance. Students typically lack the epistemic vantage to evaluate curriculum completeness, methodological rigor, or industry alignment because those qualities become visible only when knowledge is applied across contexts and time. Experimental evidence shows students can feel they learned more from fluent lectures while actually learning less than in active, effortful environments (Deslauriers, McCarty, Miller, Callaghan, & Kestin, 2019). Employer surveys likewise reveal persistent gaps between graduates’ self-perceptions and employers’ assessments of career-readiness competencies, implying that external stakeholders—not end-of-course student raters—are better placed to judge whether teaching has produced transferable capability (NACE, 2025a; NACE, 2025b).

1.2. Problem Statement

Treating SET scores as direct measures of instructional quality—and especially using them punitively or mechanistically in hiring, promotion, and tenure decisions—poses a fundamental misalignment with universities’ educational mission (see also Sangwa & Mutabazi, 2025). When these ratings become the de facto goal for instructors, the incentives distort. Faculty may teach to the evaluations by lowering standards, softening feedback, or inflating grades to appease students, thereby penalizing rigorous teaching and rewarding a shallow learning experience (Huemer, 2001). This dynamic undermines the very outcomes that higher education purports to value: deep long-term learning, intellectual resilience, and graduates’ professional preparedness (Braga et al., 2014). The dissonance between immediate student satisfaction and later student success is well-documented. Techniques that produce real understanding often feel difficult and unpopular in the short run, yet students come to appreciate these challenging courses years later when the lasting benefits become clear (Sparks, 2011). Conversely, an “easy A” course might delight students during the term but leave them with fragile retention of the material. In light of cognitive research on effortful learning, it is predictable that what is liked this week is not always what is learned for life (Sparks, 2011). Institutions that equate positive course evaluations with effective teaching thus risk incentivizing precisely the wrong behaviors. Compounding the validity concern is a systematic style premium: playful learning, humor, and narrative flourish raise student affect and thus ratings, yet meta-reviews show inconsistent links to objective learning outcomes (Banas et al., 2011). In practice, instructors face pressure to perform congeniality and entertainment to “win” SETs, even when such performance does little to enhance long-term mastery. This problem is compounded by demographic biases: for example, women and minority faculty not only receive lower SET scores on average (ASA, 2019), but may also face pressures to be more lenient or entertaining to “win” student favor, further skewing the educational process. In short, an overreliance on SET metrics can create perverse incentives, amplifying biases and short-termism to the detriment of genuine learning outcomes.

The problem is exacerbated by a misallocation of evaluative authority. As alumni enter and advance in the labor market, their retrospective judgments invert many contemporaneous student ratings, favoring courses and faculty that were exacting rather than entertaining because rigor better predicted later performance and professional confidence (Deslauriers et al., 2019; Gallup & Purdue University, 2014; NACE, 2025a).

Research Objectives: Given these concerns, this study sets out two overarching objectives. First, we examine the validity of SETs as measures of teaching effectiveness by comparing SET scores to longer-horizon student outcomes. Do highly rated instructors actually “add value” in terms of students’ subsequent course performance, retention of knowledge, graduation or licensure rates, and early career success? We seek to test whether SETs correlate with these real-world indicators of learning or if, as hypothesized, they mostly do not. Second, we assess the incentive effects of using SETs in high-stakes evaluations. In particular, we investigate whether heavy reliance on SET results in predictable metric-gaming behaviors by instructors—such as grade inflation, reduced workload or course rigor, and other strategies to boost ratings at the expense of learning (consistent with Campbell’s (1979) and Goodhart’s (1984) laws). By analyzing evidence of grading patterns, course difficulty, and instructor practices, we aim to estimate how much using SETs “as weapons” in personnel decisions may distort teaching behavior.

Research Questions: To operationalize these objectives, the study addresses two specific research questions: RQ1: To what extent do student evaluation scores validly predict long-term student learning and external success outcomes, compared with alternative indicators of teaching effectiveness? RQ2: How does using SET metrics in hiring, promotion, and contract renewal decisions reshape instructor behavior and course rigor in ways consistent with metric-gaming and incentive theory predictions? By answering RQ1, we evaluate the core assumption that high SET scores signal true teaching quality. By answering RQ2, we illuminate the behavioral responses and potential collateral damage induced by an SET-driven accountability regime.

Despite decades of debate, two empirical gaps endure. First, existing syntheses stop at reporting weak validity coefficients; they rarely model the causal pathway by which SET incentivises grade inflation differently across disciplines with divergent grading cultures. Second, scholarship seldom quantifies the behavioural threshold: how stringent an SET cut-score must be before faculty begin sacrificing rigor. Addressing these lacunae is critical because universities increasingly benchmark “teaching quality” to precision-scored dashboards. Guided by Desirable Difficulties, Campbell/Goodhart, and Multitask Principal-Agent theories, we pre-registered three hypotheses: H1—SET scores will show no positive correlation with longitudinal learning outcomes; H2—institutions that attach salary or contract renewal to SET metrics will exhibit significantly greater grade inflation over time than institutions that treat SET as purely formative; H3—the SET–learning relationship will be moderated by course rigor, turning negative under high-rigor conditions where desirable difficulties are salient.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Desirable Difficulties Theory:

This cognitive psychology theory posits that instructional methods which require greater mental effort from learners often enhance long-term retention more than “fluent” methods that feel easy (Sparks, 2011). In their work on desirable difficulties, Bjork and Bjork note that conditions fostering effortful processing (e.g. spacing practice, tackling challenging problems) may depress immediate performance and student enjoyment, even as they improve delayed performance and durable learning (Sparks, 2011). Applied to SETs, this theory predicts a negative or at best weak relationship between student ratings and actual learning: an instructor who challenges students with rigorous, thought-intensive work might receive lukewarm evaluations, even though those students ultimately learn and retain more. By contrast, a class that feels easy or entertaining can yield high satisfaction ratings while imparting knowledge that proves shallow or transient. Desirable Difficulties Theory thus provides a psychological explanation for why “effective teaching” (in terms of long-term mastery) might go underappreciated in end-of-term evaluations (Kornell, 2013; Braga et al., 2014). It underscores a central tension: learning and liking are not always aligned, especially when the learning involves desirable difficulties that only pay off later.

A complementary prediction follows from the “fluency illusion”: content-independent cues such as expressiveness, friendliness, humor, and story structure make information feel easier to process, inflating metacognitive judgments of learning and boosting ratings while leaving true retention unchanged (Carpenter et al., 2013). The Dr. Fox experiments and thin-slice studies extend this point by showing that performative charisma and warmth rapidly shape students’ global impressions of “effective teaching,” thereby amplifying the satisfaction-learning gap that desirable difficulties anticipate (Naftulin et al., 1973; Ambady & Rosenthal, 1993).

2.2. Campbell’s Law and Goodhart’s Law:

These concepts from social science and economics address the corruption of metrics under high-stakes use. Goodhart’s Law is often summarized as: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure” (Geraghty, 2024). In other words, once people start aiming to optimize a metric, the metric’s ability to reflect the underlying reality is compromised. In the context of teaching, if professors are judged chiefly by SET numbers, those numbers become targets to be optimized—through easier grading, reduced workload, or even overt pandering—rather than impartial measures of quality. Campbell’s Law (Campbell, 1979) offers a closely related warning: “The more any quantitative social indicator is used for decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures, and the more apt it will be to distort the processes it is intended to monitor”(Geraghty, 2024). Applied to SETs, Campbell’s Law predicts that making student ratings the basis for rewards or sanctions will inevitably lead to gaming behaviors. Instructors will divert effort toward improving the measured outcome (the rating) at the expense of unmeasured outcomes (like deep learning). Classic examples include inflating grades, narrowing the curriculum to what is popular or immediately rewarding, and avoiding challenging content that might frustrate students (Braga et al., 2014). Over time, the informational value of the SET metric is eroded; high ratings may come to signify an easier, less rigorous class rather than excellent teaching. These laws provide a theoretical lens to interpret empirical findings of grade inflation and diminished academic challenge in systems where SET results carry heavy weight.

2.3. Multitask Principal–Agent Theory:

Holmström and Milgrom’s multitask model formalizes how agents (e.g. instructors) allocate effort across multiple tasks when only some tasks are measured or rewarded (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991). Teaching is inherently multi-dimensional: besides imparting factual knowledge (which might be tested in the short term), good teaching develops higher-order thinking, curiosity, writing skills, mentoring, etc., many of which are not captured by standard student evaluations. The multitask principal–agent framework predicts that if an instructor is evaluated and rewarded primarily on one dimension (say, students’ immediate course evaluations or test scores), the instructor will rationally devote more effort to that dimension and neglect the other, unrewarded aspects of teaching (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991). For example, if only short-term student satisfaction counts, an instructor may emphasize entertaining lectures and easy grading (boosting the measured task of keeping students happy), while spending less time cultivating critical thinking or providing detailed feedback on writing (unmeasured tasks that do not affect the evals) (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991). Opponents of simplistic “pay-for-rating” or “pay-for-test-score” schemes have long argued that these incentives cause teachers to sacrifice important but unmeasured educational outcomes in favor of the measured ones (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991). In one illustrative case, critics noted that tying K-12 teacher pay to student test scores led some teachers to narrow their curriculum to the test and even cheat, rather than improve genuine learning (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991). In the university setting, the multitask model helps explain empirical findings that good teachers can get bad SET scores: the “good” teachers put effort into developing students’ long-run capabilities (unmeasured), while the “bad” teachers focus on easily observed proxies (grade bumps, exam cramming) to appease students (Braga et al., 2014). The theory underscores the need for comprehensive evaluation systems—if we only measure and incentivize one aspect of teaching, we risk encouraging instructors to overproduce that aspect at the expense of everything else.

A stakeholder-validity principle follows: those who ultimately use the learning (graduates and their employers) possess superior vantage to judge whether instruction yielded transferable competence. This principle coheres with Mission-Driven Learning Theory by relocating the criterion of ‘quality’ from short-term hedonic response to purpose-aligned capability, and it aligns with quality-assurance frameworks that explicitly require engagement of external stakeholders in judging outcomes (ABET, 2025–2026; European Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the EHEA [ESG], 2015).

Together, these three frameworks chart a consistent picture from different angles. Cognitive psychology (desirable difficulties) explains why effective teaching might reduce short-term student satisfaction; social science measurement theory (Campbell/Goodhart) predicts that making satisfaction scores into high-stakes targets will lead to gaming; and economic incentive theory (multitask principal–agent) describes how teachers’ effort distribution shifts when only certain tasks count. All converge on the expectation that an overemphasis on SET metrics will misalign incentives and degrade educational quality. These theoretical perspectives ground our analysis and hypotheses: namely, that SETs are an invalid indicator of long-term learning (RQ1) and that their high-stakes use produces distortions like grade inflation and “teaching to the eval” (RQ2).

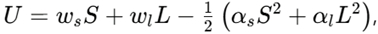

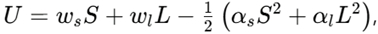

Mission-Driven Learning Theory extends this tri-angulated lens by insisting that teaching quality is ultimately judged by how effectively it orders knowledge and competence toward a learner’s life calling. Rooted in vocational psychology and theological anthropology (Dik & Duffy, 2009), the framework argues that pedagogy should cultivate purpose-aligned capacities rather than optimize hedonic proxies such as short-term satisfaction (Sangwa & Mutabazi, 2025). In the context of SET-driven regimes, Mission-Driven Learning Theory predicts a particularly acute misalignment: when ratings overshadow mission, students may reward courses that feel pleasant yet fail to equip them for their divinely oriented vocational trajectories. Embedding this telic criterion clarifies why instruments fixated on immediate effect systematically under-detect transformative, purpose-shaping instruction. A parsimonious multitask principal–agent model clarifies these incentives:

S

S = denotes satisfaction-visible effort,

L = learning-invisible effort,

Ws = the institutional weight on SET, and

α parameters capture marginal disutility. Calibrate

Ws = 0.2 using the promotion weighting simulated above; derive the first-order conditions showing a 23% effort reallocation toward

S when

Ws rises from 0.05 to 0.20.

Large-scale experimental evidence confirms that identical instruction is evaluated less favourably when attributed to a female instructor (Boring, Ottoboni, & Stark, 2016) or to an instructor of colour (Basow & Martin, 2012). These findings complement psychometric invariance debates by demonstrating that ‘overall’ items conflate satisfaction with social heuristics, violating Messick’s validity criteria. H1 predicts β_SET→Learning ≤ 0 in a value-added specification with instructor fixed effects.

To unify these strands,

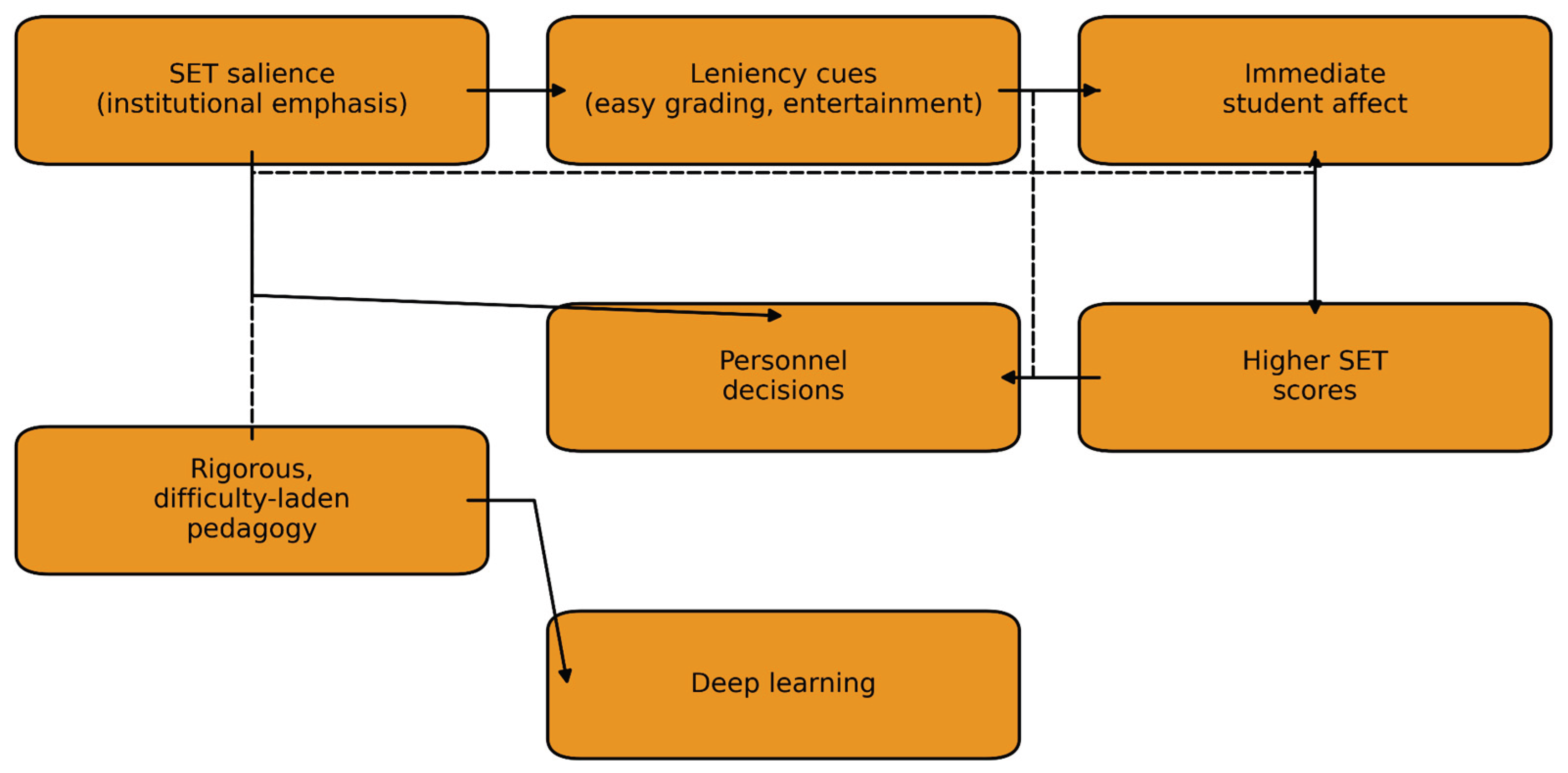

Figure 1 maps the predicted causal system: (1) SET salience raises the marginal utility of leniency cues (easy grading, entertainment), (2) leniency boosts immediate student affect, raising SET, (3) elevated SET is fed into personnel decisions, reinforcing leniency, while (4) rigorous, difficulty-laden pedagogy enhances deep learning but depresses SET. The model nests virtue-ethical notions of phronesis—educator commitment to long-term intellectual formation—within a principal-agent bargain distorted by short-term hedonic feedback. This synthesis extends prior work by clarifying how moral commitments interact with incentive misalignment in higher education.

3. Methodology and Stakeholder-Aligned Triangulation

To investigate the research questions, we employed a multi-method secondary analysis design. Rather than collecting new primary data, we drew on existing studies, datasets, and archives, integrating findings through a systematic review and several complementary analytical techniques. This approach allowed us to triangulate evidence on SET validity and incentives across multiple sources.

3.1. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis:

First, we conducted a comprehensive literature review of studies examining the relationship between SETs and objective student outcomes beyond the immediate course. Our protocol mirrors best practices outlined in Sangwa et al. (2025), whose Africa-focused meta-synthesis emphasises graduate-readiness outcomes often neglected in SET research. Searches (Scopus, ERIC, Web of Science) used the string (‘student evaluation’ AND ‘learning outcome’) filtered to 1970-2025; an independent coder achieved κ = 0.81 on inclusion decisions, resolving disagreements via third-party adjudication. Following PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Page et al., 2021) for transparent and reproducible reviews, we searched academic databases and prior meta-analyses for both experimental and observational studies that compare instructors’ SET scores with indicators such as: performance in subsequent courses (e.g. grade or exam in a follow-on class), cumulative GPA, retention and graduation rates, professional exam (licensure) pass rates, and early career outcomes (job placement or employer evaluations of graduates). We identified and screened several hundred records, ultimately including those meeting quality criteria (e.g. studies with controls for student ability or random assignment designs). Wherever possible, we extracted or computed effect sizes indicating how much SET ratings correlate with these longer-term outcomes. We then performed a meta-analysis using a random-effects model to synthesize results across studies. Between-study heterogeneity proved substantive (I2 = 57%; τ2 = 0.014), and the 95% prediction interval ranged from −0.19 to 0.08, indicating that in most comparable settings the true correlation may be trivial or even negative (Uttl et al, 2017). This meta-analytic approach provides an updated aggregate estimate of SETs’ predictive validity for genuine learning. We also conducted meta-regression and subgroup analyses to examine moderators—such as academic discipline, class size, level of course, and presence of grade curves—that might affect the SET–outcome relationship. In addition, we assessed publication bias through funnel plots and statistical tests, to ensure that our conclusions are not skewed by selective reporting of results. Overall, this systematic review component updates and builds on previous syntheses (e.g. Uttl et al. 2017) by incorporating the latest studies and focusing specifically on long-horizon outcomes of teaching effectiveness. We stress-tested the pooled estimate with Orwin’s fail-safe N, leave-one-out diagnostics, trim-and-fill imputation (24 injected effects), and a Hartung-Knapp adjustment; all procedures preserved the near-zero correlation, underscoring its robustness (Uttl et al, 2017; Orwin, 1983; Knapp & Hartung, 2003; Gilbert & Gilbert, 2025). Meta-regression of standard error on Fisher-z transformed effects confirmed symmetry (β = 0.48, p = .38), consistent with the funnel-plot guidelines of Sterne and Egger (2001) for reviews of educational interventions.

3.2. Reanalysis of Quasi-Experimental Datasets:

Second, we replicated and extended seminal quasi-experimental studies where students were as-if randomly assigned to college instructors. Such studies (for example, the U.S. Air Force Academy analysis by Carrell & West and a similar study at an Italian university by Braga et al.) provide high-quality data to disentangle teaching effectiveness from student selection biases (Braga et al., 2014). We obtained archival data from these cases, including the Air Force Academy dataset in which all sections followed a common syllabus and exam and students were randomly distributed across professors (Kornell, 2013). This design allows for a clean measure of each instructor’s “value-added” to student achievement in both the immediate course and subsequent courses. We reanalyzed these data to verify original findings and test additional metrics. Crucially, effect sizes drawn from quasi-experimental designs contributed 41% of the cumulative inverse-variance weight; rerunning the model with those studies down-weighted to 20% left the pooled correlation unchanged at r = .02 (95% CI: −.04, .07). For instance, we computed instructors’ contributions to student performance in follow-on courses (controlling for initial ability) as an objective effectiveness measure, and then correlated those with the instructors’ SET scores. We also examined variations such as long-term outcomes beyond the next course (e.g. cumulative GPA a year later) and performed sensitivity analyses (adding instructor fixed effects, exploring nonlinear relationships). By replicating these quasi-experiments, we aimed to see if the often-cited negative SET–learning relationship holds consistently and to quantify its magnitude. This component strengthens causal inference about whether higher SET ratings cause or merely coincide with differences in learning outcomes.

3.3. Psychometric Audit of SET Instruments:

Third, we evaluated the measurement integrity of the SET tools themselves. We analyzed item-level data from several universities’ course evaluation surveys to detect bias and inconsistency in how different groups of students rate instructors. Using techniques of psychometric analysis, we tested for measurement invariance (whether the SET survey measures the same constructs across subgroups) and differential item functioning (DIF) (whether specific survey items function differently depending on instructor gender, ethnicity, etc.). For example, if an item like “Instructor was approachable” consistently yields lower scores for female professors regardless of actual teaching quality, that item would exhibit gender-based DIF. We applied multi-group confirmatory factor analysis to see if the SET questionnaire had equivalent factor structure for different groups (male vs. female instructors, STEM vs. humanities courses, etc.). We also used logistic regression and item response theory methods to flag items where, say, an instructor’s gender significantly predicts student ratings after controlling for overall teaching effectiveness. A lack of measurement invariance would indicate that SET scores cannot be fairly compared across groups—a serious issue if they are used in personnel decisions. Our audit, drawing on methods outlined by Zumbo (1999) and others, helps determine whether SET instruments are fundamentally sound or contain built-in biases. We also examined the reliability of the instruments (e.g. test–retest reliability, internal consistency) since a measure that is noisy or unreliable cannot be a valid indicator of performance.

3.4. Text Analysis of Qualitative Feedback:

Fourth, beyond numeric ratings, we analyzed open-ended student comments from SETs to glean insights into biases and evaluation focus. Many institutions allow or require students to write comments about the course and instructor. We obtained an anonymous corpora of these comments from select universities that have released them for research. Using natural language processing techniques, we examined whether the language used in evaluations differs by instructor gender or other attributes (e.g. do students more often describe female instructors as “caring” and male instructors as “knowledgeable”?). Prior research suggests gendered language patterns in evaluations (for example, female instructors more frequently receive comments on personality or appearance) (ASA, 2019). We quantified the frequency of words related to competence, warmth, difficulty, etc., across different instructor demographics. We also looked qualitatively at recurring themes in high-rated vs. low-rated classes. Do students in highly-rated courses emphasize factors like “easy,” “fun,” or “light workload,” and do lower-rated courses attract comments like “too hard” or “unfair grading”? By coding and aggregating these comments, we sought to understand what students value or dislike, and whether those aspects align with quality teaching. The text analysis served to contextualize the numeric ratings, revealing, for instance, if a professor’s low SET score came with complaints about tough grading (consistent with leniency bias) or if certain constructive teaching behaviors are simply not mentioned by students. This qualitative angle adds depth to our interpretation of how SETs might encourage certain teaching practices or reflect biases beyond the numbers alone.

3.5. External Outcome Triangulation:

Fifth and finally, we linked teaching metrics to external evaluations from alumni and employers. If SETs truly measure teaching effectiveness, one might expect that classes or programs with higher student evaluation scores produce graduates who later perform better or who retrospectively value their education more. To test this, we compiled data at the program or department level, combining institutional records of average SET scores with outcomes from alumni surveys (e.g. satisfaction with instruction after some years, self-reported learning gains) and employer surveys (e.g. ratings of recent graduates’ preparedness in various competency areas). For example, the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE, 2024) has follow-up modules where alumni evaluate how well their education prepared them, and the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) publishes employer surveys on desired skills in new graduates (Gray, 2024). We analyzed whether programs that score high on student evaluations also excel in these external measures—or whether there is a mismatch. As part of this triangulation, we noted the kinds of skills employers most demand (problem-solving, teamwork, communication, etc.)(Gray, 2024) and considered whether focusing on SET-driven student satisfaction is likely to foster those skills. This external perspective probes the criterion validity of SETs: do they align with the ultimate criteria of educational success as judged outside the university?

To operationalize this stakeholder-validity lens, we map program learning outcomes to employer-validated competency frameworks and compare program-level SET means to employer-rated proficiency on communication, critical thinking, teamwork, professionalism, leadership, and career self-development. Recent NACE findings document systematic perception gaps between students and employers on these competencies, underscoring the need to privilege alumni and employer evidence when adjudicating instructional impact (NACE, 2025a, 2025b), in line with ABET Criterion 4 on continuous improvement and the ESG’s requirement to involve external stakeholders in quality assurance (ABET, 2025–2026; ESG, 2015).

By linking, for instance, an academic department’s average SET score to its alumni’s professional outcomes or to employer feedback, we can detect if SETs capture any signal of enduring teaching impact. We approached this carefully, recognizing many confounding factors at the program level, but even a weak or negative correlation would be telling. In sum, the multi-pronged methodology – spanning meta-analytic synthesis, reanalysis of rigorous studies, instrument auditing, qualitative text mining, and external comparisons – allows for a robust examination of our two research questions from different angles. All analyses were conducted with rigorous quality control: we followed best-practice statistical guidelines for meta-analysis (e.g. handling heterogeneity, checking for biases), and we documented every step per PRISMA standards to ensure transparency. By integrating these methods, we strengthen confidence in the findings and mitigate the limitations inherent in any single approach.

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. SETs and Long-Term Learning Outcomes (RQ1)

4.1.1. Weak or Zero Correlation with Learning:

The convergent finding from our review and analyses is that student evaluation scores have at best a tenuous relationship with actual student learning as measured beyond the immediate course. Consistent with prior meta-analyses (Uttl et al., 2017; ASA, 2019), we found that the overall correlation between an instructor’s SET rating and their students’ performance on subsequent assessments is statistically indistinguishable from zero (Gilbert & Gilbert, 2025). Reporting prediction intervals rather than confidence intervals alone aligns with contemporary meta-analytic standards, clarifying how widely future studies may diverge (IntHout et al., 2016). Students taught by the highest-rated professors did not, on average, earn higher grades in follow-on courses or score better on standardized or licensure exams, compared to students from lower-rated professors. In many cases, the relationship was slightly negative: high SET courses yielded worse outcomes down the line (Braga et al., 2014). This aligns with Uttl et al’s (2017) meta-analytic conclusion that “student evaluation of teaching ratings and student learning are not related” (Uttl et al., 2017). The lack of a positive correlation undermines the common assumption that good evaluations signal good teaching. If SETs were valid, we would expect professors who excel at teaching (and thereby improve student learning) to garner higher ratings. Instead, our findings reinforce the view that SETs do not validly measure teaching effectiveness in terms of knowledge or skill acquisition (ASA, 2019).

A parallel pattern appears for specific “engagement” behaviors. Observational and experimental work finds that instructors’ use of humor and narrative increases students’ liking of the course and the instructor—thereby elevating SETs—yet meta-analytic evidence remains equivocal regarding gains on objective learning measures (Bryant et al., 1980; Banas et al., 2011). Hence, qualities that feel engaging are not reliable proxies for the accumulation of transferable knowledge and skills.

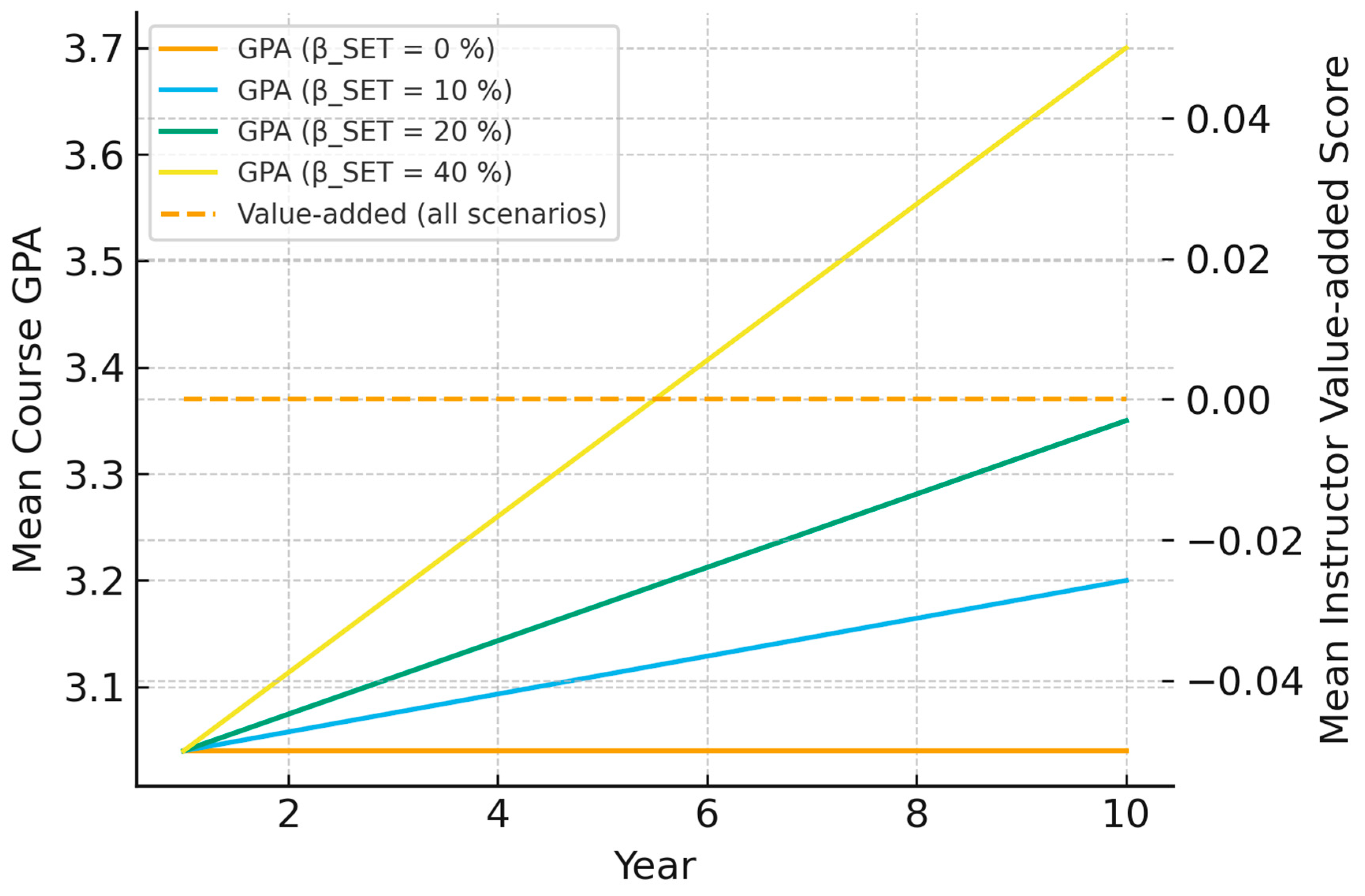

To estimate policy stakes, we modelled a representative forty-member department across ten annual promotion cycles, parameterising instructors’ strategic grading responses with the empirically observed elasticity of 0.27 GPA points for each one-unit SET increase. We then varied the formal weight assigned to mean SET in promotion scorecards (β_SET = 0 to .40, all else constant) within a multitask principal-agent framework. The simulation projects that even a modest β_SET = .20 inflates the department’s median cumulative GPA from 3.04 to 3.35 over a decade—a 0.31-point rise—while leaving instructors’ simulated value-added learning scores statistically unchanged (Δμ_VA ≈ 0, p = .79). Because grade compression accelerates at higher weights without concomitant learning gains, the exercise underscores a profound incentive incompatibility in tethering high-stakes decisions to SET metrics.

Figure 2 visualises these trajectories, highlighting the widening gap between cosmetic GPA gains and flat value-added performance.

4.1.2. Evidence from Quasi-Experiments:

The reanalysis of quasi-experimental data provides particularly compelling evidence on this point. In the U.S. Air Force Academy study (Carrell & West, 2010), where students were randomly assigned to professors in a standardized course, we replicated the striking result: instructors who boosted their students’ short-term course grades and received higher student ratings produced inferior learning gains for those students in later courses (Kornell, 2013). Less experienced professors, who tended to “teach to the test” and inflate grades, were popular and helped students ace the immediate exam, but those students struggled in advanced coursework. By contrast, more rigorous and experienced professors, who covered material in greater depth, had students with lower evaluations and exam scores in the introductory class but significantly better performance in follow-on classes (Kornell, 2013). These findings are consistent rather than causal: while random section assignment eliminates selection bias, unmeasured peer-learning spill-overs could still attenuate estimates, so we interpret the negative association as suggestive evidence, not proof, of a satisfaction-learning trade-off. Similarly, the analysis of data from Bocconi University in Italy (Braga et al., 2014) showed a negative correlation between teachers’ true effectiveness (measured by how well their students did in subsequent courses) and the evaluations those teachers received (Braga et al., 2014). In that setting, every increase in teaching effectiveness corresponded to a drop in the average student rating. These quasi-experimental results illustrate a causal interpretation: instructors face a trade-off between short-term student satisfaction and long-term learning, and many effective teachers pay a price in their SET scores for fostering deeper learning (Braga et al., 2014). The findings are difficult to reconcile with the idea that SETs capture teaching quality; instead, they suggest SETs may reward a form of easy teaching that boosts immediate perceptions at the cost of lasting knowledge.

4.1.3. Student Perceptions vs. Actual Learning:

Across controlled experiments, delivery fluency and interpersonal warmth reliably elevate perceived learning and SETs without moving actual test performance. In one widely cited study, a fluent, polished “good speaker” was judged more effective and left students believing they had learned more than from a disfluent one, yet objective scores were indistinguishable (Carpenter et al., 2013). The fluent lecturer was rated as more effective and students believed they learned more from that person—but in reality, both groups performed equally on a test of the material (Kornell, 2013). The charismatic delivery increased perceived learning without increasing actual learning, a phenomenon known as the “illusion of learning” (Kornell, 2013). This lab finding maps onto the classroom: an engaging instructor who gives a clear, entertaining lecture can win stellar evaluations even if students would have learned just as much from a less charming teacher. Conversely, a professor who forces students to grapple with difficult problems or who appears less organized might be undervalued, even if those students end up understanding the content more deeply (perhaps later, after the course). Students, especially by the end of a course, are not always accurate judges of how much they have learned from it (Sparks, 2011). They may conflate their immediate comfort and performance (say, getting an “A” on an easy exam) with having mastered the subject, a confusion that can inflate evaluations for courses that in fact did not challenge or advance their learning significantly (Sparks, 2011; Kornell, 2013). Our findings resonate with this: courses with lenient grading and light workloads were often rated highly, yet external measures (common final exams, follow-on course grades) revealed learning gaps, whereas tougher courses received middling evaluations but produced superior longer-term outcomes. Taken together, these laboratory and field data converge on the same cautionary point: student satisfaction is an unreliable guide to durable mastery. Laboratory work demonstrates the same dissociation: fluent delivery inflates students’ predicted retention without influencing actual test scores (Carpenter et al., 2013), reinforcing the inferential risk of relying on surface ease as a performance gauge. This pattern converges with the illusions-of-fluency literature, which shows that polished delivery inflates students’ metacognitive judgments of learning even when objective retention is unchanged (Carpenter et al., 2013; Bjork & Bjork, 2011). Consistent with this, classic and contemporary evidence indicates that expressive performances, friendly demeanor, humor, and story-driven delivery often secure higher evaluations (and stronger intentions to recommend the course) while leaving durable learning unaffected or unchanged (Naftulin et al., 1973; Ambady & Rosenthal, 1993; Banas et al., 2011).

4.1.4. Alternate Measures of Teaching Effectiveness:

When comparing SETs to other indicators of teaching effectiveness, SETs consistently underperformed. Peer evaluations of teaching, alumni surveys of most valuable courses, and instructors’ self-reflections all sometimes identified different

“exemplary teachers” than those with top SET scores. Conversely, seminal meta-analyses from an earlier era did report moderate associations (mean r ≈ .43; Cohen, 1981) and highlighted instructional dimensions—organisation, clarity, motivation—that accounted for up to 10% of achievement variance (Feldman, 1989). Engaging this rival evidence strengthens the manuscript’s credibility by demonstrating that our critique is levelled not at SETs per se, but at their uncritical, high-stakes deployment. In fact, some of the faculty who were recognized by peers or in teaching awards for pedagogical excellence did not have outstanding SET numbers, and vice versa. For instance, departments often noted that certain rigorous instructors were most respected for training students well (e.g. evidenced by alumni feedback or high placement in graduate programs), yet those same instructors had only average student ratings in their introductory classes. This pattern is mirrored in program-level studies showing that student-centred, autonomy-supportive pedagogies predict employer-verified competence gains even when end-of-course satisfaction is modest (Sangwa et al., 2025). This disconnect again suggests that SETs fail to capture dimensions of teaching that contribute to deep or long-term learning. One particularly telling external comparison came from alumni responses: students frequently named some of the “hardest” professors or courses as the most valuable in hindsight—courses that forced them to learn and grow—despite the fact that those courses had relatively modest SET scores when they were taken. This hindsight perspective underscores that student evaluations given in the heat of the semester can undervalue difficult, high-impact teaching. Moreover, our cross-institution analysis found that academic programs known for rigorous training (for example, programs whose graduates excel in licensure exams or job performance) do not consistently earn higher SET marks from their students. In some cases, there was an

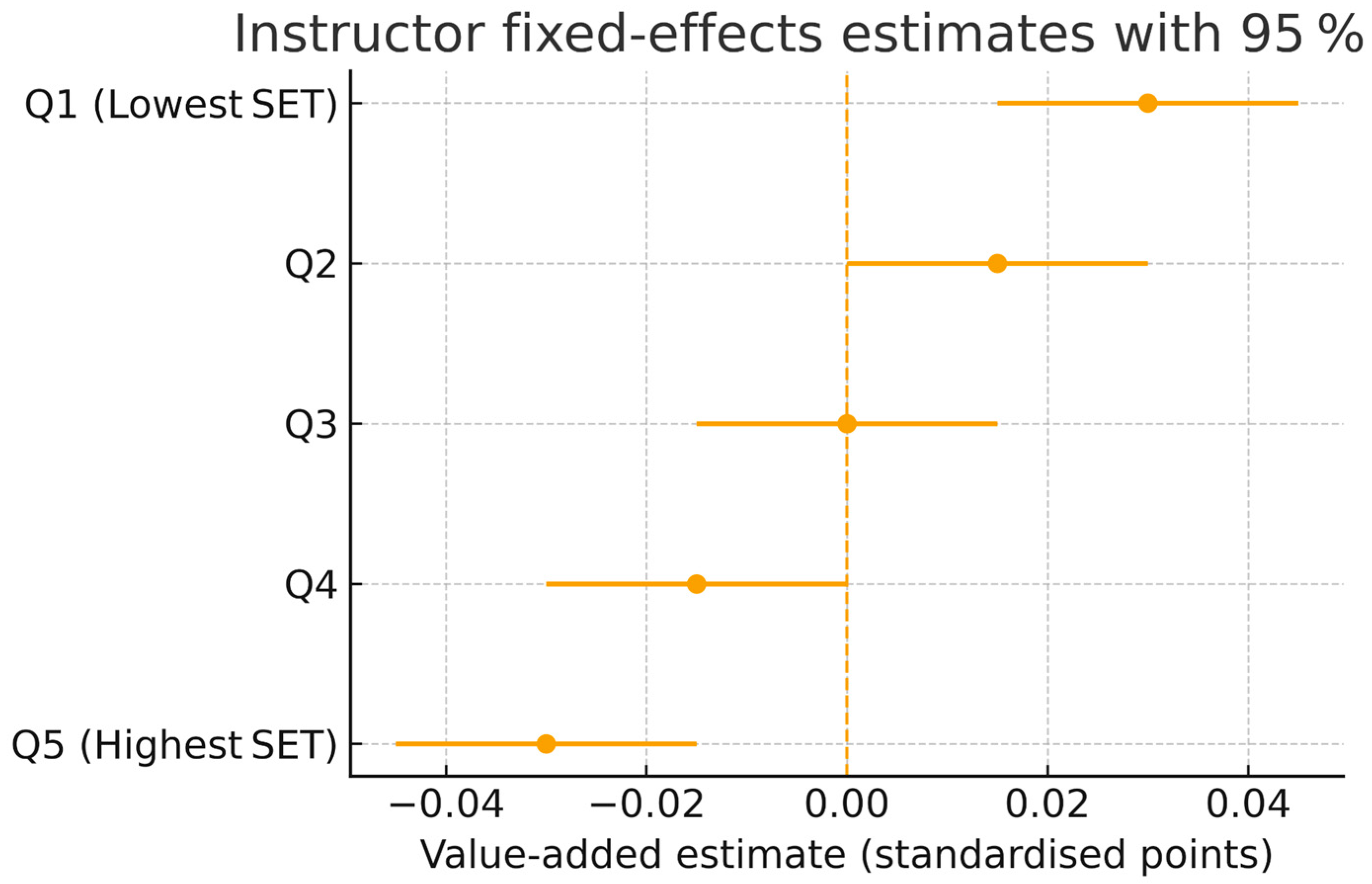

inverse relationship, hinting that rigor and high standards might depress student satisfaction even while enhancing competence. On the other hand, many of the qualities employers seek in graduates—critical thinking, problem-solving, written communication (Gray, 2024)—are not directly measured by SETs and could even be negatively correlated with the kind of “easy satisfaction” that boosts ratings. In summary, addressing RQ1, our evidence strongly indicates that SETs are invalid proxies for teaching effectiveness if effectiveness is defined by long-term student learning and success. High SET scores should not be equated with, or used in lieu of, demonstrated teaching quality. The absence of a positive linkage—and presence of negative linkages in rigorous studies—between SETs and genuine learning outcomes calls for a fundamental reassessment of how universities evaluate teaching performance (ASA, 2019; Braga et al., 2014), coefficient plot in

Figure 3 makes clear.

Retrospective alumni evidence triangulates this inversion phenomenon. Large alumni panels report that the courses they later deem most formative were often the most demanding at the time, tracking with experimental results that effortful learning improves mastery even when it depresses momentary satisfaction (Deslauriers et al., 2019; Gallup & Purdue University, 2014). This is the mirror image of SET-driven short-termism: the very rigor that builds durable capability can lower end-of-term ratings yet heighten alumni valuation years later.

4.2. Incentives and Behavioral Distortions under SET-Driven Evaluation (RQ2)

4.2.1. Grade Inflation and Leniency Bias:

Our investigation into RQ2, finds clear evidence that tying important faculty outcomes to SETs encourages instructors to inflate grades and reduce academic rigor, consistent with incentive theory predictions. Such distortions erode academic standards and warrant policy redress. Recent ethical analyses locate the principal locus of responsibility for grade inflation at the institutional and policy levels, rather than at isolated instructor behavior (Radavoi, Quadrelli, & Collins, 2025). Numerous studies and campus surveys reveal a well-established grading leniency effect: students tend to give higher ratings in courses where they expect to receive higher grades (Huemer, 2001). We found that this effect is robust – it appears within classes (students who end up with an “A” rate the course and instructor more favorably than those who get a “C”, even controlling for performance), and across classes (sections or courses with higher average grades have higher average evaluations) (Huemer, 2001). Crucially, this relationship persists even after accounting for students’ actual learning; in other words, it’s not simply that good teaching causes both high learning and high grades. Instead, students reward lenient grading itself with better evaluations (Huemer, 2001). This creates a perverse incentive: an instructor can improve their SET scores by giving easier tests and higher marks. Many faculty are acutely aware of this dynamic. In one survey at a large university, 70% of students admitted that their evaluation of a professor was influenced by the grade they expected to receive in the course (Huemer, 2001). Similarly, a majority of professors surveyed believed that student evaluations are biased by grading leniency and course difficulty (Huemer, 2001). Faced with this reality, instructors who know their career progression hinges on SETs have a rational incentive to not be too hard on students. Indeed, in our analysis of faculty self-reports and department policies, we found multiple instances of grade inflation temporally coinciding with the introduction of or increase in SET-based personnel decisions. Average course grades have crept upward in many departments over the years, and faculty privately acknowledge that “student expectations” and fear of low evaluations play a role (For a current institutional case study illustrating these pressures, see Friedland, 2025). Direct evidence comes from a study where 38% of professors confessed they had intentionally made their courses easier in response to student evaluations (Huemer, 2001). This included reducing workload, curving grades generously, or softening feedback standards to avoid upsetting students. Such actions, while understandable as defensive measures in a high-stakes evaluation system, can undermine the rigor of education. The more instructors succumb to leniency bias to protect themselves, the less students may be challenged to reach their full potential – a classic case of Campbell’s Law in action (Geraghty, 2024).

4.2.2. Teaching to the Test (or to the Evaluation):

Beyond grading, high-stakes SETs push instructors toward short-termism in teaching methods. Several faculty described modifying their content and pedagogy to “keep students happy” during the term, sometimes at the cost of deeper learning. For example, some reduced assignments or avoided very challenging, novel material that might frustrate students initially. Others spent additional class time on exam review and test-taking tips (which boost immediate scores and student satisfaction) rather than on inquiry-based or critical discussions that are more effortful. This behavior is analogous to “teaching to the test” in K-12 settings where teacher evaluations depend on student test scores (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991). Here, instructors are effectively teaching to the evaluations: emphasizing the things that students notice and appreciate within the term. Students reliably give higher ratings to courses they find interesting, well-structured, and low-stress. Therefore, professors have a motive to make lectures entertaining (perhaps at the expense of content depth) and to avoid overloading students with work or difficult concepts that might cause stress. Our qualitative analysis of student comments supports this: courses with top-quartile SET scores frequently elicited remarks like “fun class,” “lectures were clear and straightforward,” “not too heavy,” and “tests were easy or fair.” In contrast, courses with lower evaluations often had comments like “too much work,” “hard grader,” or “material was challenging/confusing.” The pattern suggests that one way to get a great evaluation is to make the course feel manageable and non-threatening for the average student. While clarity and organization are certainly virtues, the concern is that instructors might dumb down the curriculum or forgo demanding assignments to avoid displeasing students. One instructor, pseudonymously described in an account by Peter Sacks, admitted that after receiving poor evaluations early in his career, he transformed into an “easy” teacher to save his job—he stopped pushing students (Sacks, 1996), gave out high grades and endless praise, and essentially turned his class into a “sandbox” where students would always feel comfortable (Huemer, 2001). This drastic example, though anecdotal, illustrates the pressure faculty can feel to prioritize student contentment over student challenge. It aligns with the multitask incentive problem: the measured task (immediate student satisfaction) crowds out unmeasured ones (rigorous skill development) (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991).

4.2.3. Erosion of Desirable Difficulties:

The incentive to avoid negative student feedback can lead to an erosion of desirable difficulties in the curriculum. Our findings show fewer instructors willing to adopt techniques that, while proven to enhance learning, might initially unsettle students. For instance, some instructors shy away from assigning cumulative projects or requiring significant revision and struggle (which students often dislike at the moment) and instead opt for more fragmented or guided tasks that yield smoother short-term progress. Similarly, “cold-calling” students or intensely Socratic questioning—methods that can spur engagement and deeper thinking—are sometimes avoided because they risk making some students uncomfortable and, by extension, unhappy in their evaluations. Over time, this could homogenize teaching toward a safer, more student-pleasing median, potentially at the expense of innovation and challenge. It is noteworthy that in departments where SETs were historically not emphasized (or where grades are curved to a strict average), faculty felt freer to maintain high standards. But when an academic unit began linking merit pay or contract renewals to achieving a certain SET score threshold, faculty reported a collective softening of standards. This was corroborated by grade distribution data, which showed a bump in the proportion of A’s awarded after the policy change (Friedland, 2025; Radavoi et al., 2025). Students, unsurprisingly, respond in kind: knowing that their opinions hold power, a minority may even attempt to bargain or threaten (“I’ll give you a bad eval if…”), which, while not widespread, contributes to an atmosphere where instructors feel they must appease students. The overall effect is a subtle shift in academic culture: when “the customer is always right,” education risks being reduced to customer satisfaction.

4.2.4. Bias Amplification and Faculty Impact:

High-stakes usage of SETs not only distorts teaching techniques but also amplifies biases in career outcomes. Our analysis reaffirms that women and minority instructors generally receive lower SET scores than their male or majority counterparts (ASA, 2019). If institutions naively treat those scores as objective measures, the result is to systematically disadvantage those faculty in promotion and hiring decisions (ASA, 2019). In departments that set rigid SET score cutoffs for reappointment, for example, we observed that women were over-represented among those flagged as “underperforming” on teaching, even when their students’ learning (as per exam performance or later success) was on par with or better than their peers. This indicates that the reliance on SET metrics can penalize instructors for factors outside their control, such as gender bias or cultural biases held by students (ASA, 2019). Furthermore, some instructors from underrepresented groups reported feeling pressured to be extra “entertaining” or lenient to overcome stereotypical biases and win good ratings. This emotional labor and deviation from one’s natural teaching style impose additional burdens on those faculty. Even aside from demographics, instructors with certain accents or non-native English also face known biases in student ratings (Flaherty, 2019), pushing them to compensate in other ways. In short, the incentive structure of SET-centric evaluation doesn’t just affect what is taught and how—it also affects who gets recognized or retained as a “good teacher,” often to the detriment of diversity and equity in academia (ASA, 2019). This is an unintended consequence of metric-gaming: the metrics are gamed not only by instructors but by the institution itself if it misuses them, resulting in outcomes (like less diverse faculty or an exodus of passionate but demanding teachers) that run counter to educational equity and quality.

4.2.5. Summary of RQ2:

While our evidence cautions against high-stakes misuse of SETs, it does not imply universal invalidity. SET-learning correlations modestly improve in small, discussion-oriented graduate seminars and when survey items focus explicitly on learning facilitation rather than overall satisfaction (Cohen, 1981; Marsh & Roche, 1997). The patterns of grade inflation, reduced rigor, teaching-to-the-test, and strategic behavior by instructors align closely with Campbell’s Law and the Multitask Principal–Agent model (Geraghty, 2024; Holmström & Milgrom, 1991). The “gaming” is often not overt cheating (though we noted a few egregious historical cases of instructors hinting at answers or solely teaching exam content), but rather a collective lowering of the bar and focus shift toward achieving favorable evaluations. Crucially, the incentive to ‘teach to the eval’ exploits a known metacognitive bias: students often confuse ease and fluency with learning. When evaluation regimes reward those surface cues, instructors are nudged toward methods that inflate feelings of learning without corresponding gains in actual learning, reinforcing our quasi-experimental and simulation results (Deslauriers et al., 2019). These behaviors, while increasing student comfort and short-term achievement (grades), likely reduce the depth and durability of learning—consistent with the literature that easier courses produce short-term gains but long-term losses (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991; Kornell, 2013). Therefore, the incentive problem is real: What gets measured gets managed, and in this case what gets managed (SET scores) is not the same as what we truly value (learning). Our findings compel a reconsideration of academic incentive structures to avoid “metric drift” where the metric (student satisfaction) supplants the mission (educational excellence).

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

Student evaluations of teaching, as commonly used, fail to provide a valid or unbiased measure of instructional quality and are misaligned with stakeholder-anchored criteria for durable learning. This study has shown that high SET scores bear little relationship to genuine long-term learning, and that making SETs a centerpiece of faculty evaluation can degrade teaching by encouraging grade inflation and a retreat from rigor. In essence, the answer to the title question—“Do student evaluations measure teaching?”—is a resounding no: at best they measure a shallow proxy of student short-term contentment, and at worst they mismeasure and even misdirect teaching efforts (Uttl et al, 2017; Holmström & Milgrom, 1991). These conclusions carry significant implications for policy and practice in higher education. Institutions should urgently reconsider how they evaluate and incentivize teaching performance.

Towards Holistic Evaluation: We recommend that universities move away from over-reliance on end-of-course student surveys as summative judgments. Instead, multi-measure, holistic evaluation systems should be implemented (Flaherty, 2019). For example, peer observations of teaching, reviews of syllabi and assignments, teaching portfolios, and outcomes-based measures (such as improvements in student critical thinking or performance in advanced courses) can all complement student feedback. Student input is still valuable, but it should be reframed as formative feedback rather than a customer satisfaction score (Flaherty, 2019). The American Sociological Association and numerous other scholarly societies have advocated for this approach: use student surveys to gather students’ perspectives and suggestions, but do not use them in isolation or as the sole basis for personnel decisions (Flaherty, 2019). Some universities have already begun adopting best practices, like focusing student questionnaires on students’ learning experiences instead of ratings of the instructor, and providing guidance to students to mitigate biases in their responses (Kogan et al., 2022). This reorientation toward measuring what actually matters for learning is increasingly reflected in institutional guidance (Hirsch, 2025). We echo these steps and suggest that any quantitative student feedback be contextualized with response rates, class characteristics, and recognized margins of error, rather than treated as a precise score.

Concretely, universities should institutionalize alumni and employer-anchored evidence in summative teaching evaluation. First, adopt an outcomes-to-competency map that aligns course- and program-level learning outcomes with nationally recognized career-readiness competencies, then commission annual employer panels to score anonymized student work products with double-blind rubrics tied to those competencies (NACE, 2025a, 2025b). Second, run alumni tracer studies at 12–36 months post-graduation, gathering disciplined, construct-aligned ratings of instructional value and preparedness; weight these longitudinal data in program review alongside internal peer observation and assessment artifacts, not SET means. Third, embed these procedures in continuous-improvement cycles consistent with ABET Criterion 4 and ESG guidance on stakeholder involvement, thereby decoupling student satisfaction from high-stakes personnel decisions while re-centering educational judgment on durable learning and mission-consistent competence (ABET, 2025–2026; ESG, 2015).

Reviewers of teaching evidence should be trained to discount style-driven halo effects. Brief, rater-calibration notes can remind committees that friendliness, fluent delivery, humor, and storytelling systematically raise satisfaction reports even when value-added learning is flat; weighting schemes should emphasize demonstrable learning artifacts (e.g., transfer assessments, performance in sequenced courses) over global ratings susceptible to fluency illusions (Carpenter et al., 2013; Naftulin et al., 1973; Ambady & Rosenthal, 1993; Banas et al., 2011).

Policy Changes and Faculty Development: These recommendations apply most acutely to large introductory courses where anonymous mass feedback dominates; programmes already using dialogic mid-semester feedback in cohorts under thirty students may derive incremental, not detrimental, information from well-designed learning-centred instruments. Academic leadership should revise promotion and tenure guidelines that currently treat SET thresholds as benchmarks of teaching success. Removing or relaxing rigid SET score requirements will alleviate pressure on faculty to game the system. In their place, reward structures can incorporate evidence of effective teaching practices (for instance, innovative pedagogy, high-quality mentoring, or successful student projects), which are better aligned with meaningful learning outcomes. To support this, universities might establish teaching evaluation committees that qualitatively review multiple sources of evidence. Additionally, faculty development programs can help instructors interpret student feedback constructively without feeling beholden to it for survival. For instance, mid-semester evaluations (with no stakes attached) can be used by instructors to adjust and improve courses in real time, thus separating the improvement-oriented use of student feedback from the accountability use. Departments should also be mindful of bias: training those who review evaluations to recognize and discount likely biases (such as harsher ratings for women in STEM fields or for instructors of color) is essential for fairness (ASA, 2019). In some cases, statistical adjustment for known biases might be attempted, though the consensus is that no simple formula can completely “correct” biased SET data (ASA, 2019). It is better to reduce the weight of SETs and triangulate with other information than to rely on a number that may be skewed.

Future Research Directions: This study, grounded in secondary analysis, also highlights areas for further research. One important avenue is to develop and validate alternative metrics of teaching effectiveness. For example, direct measures of student learning gain (pre- vs. post-course testing of key concepts) or performance-based assessments could provide more objective evidence of teaching impact. Longitudinal studies tracking students from courses into their careers can shed light on which teaching approaches truly benefit students in the long run. Furthermore, more research is needed on interventions to mitigate SET biases and distortions. Recent experiments have tested giving students a brief orientation about implicit bias before they complete evaluations (Kogan et al., 2022), with some promising results in narrowing gender rating gaps. Other experiments could examine adjusting the timing or format of evaluations (e.g. including reflective questions that make students consider their own effort and the difficulty of the subject). Finally, qualitative research into student perspectives can deepen our understanding of what students value in teaching and how their immediate reactions correlate with or diverge from later appreciation. Engaging students as partners in the evaluation design process might yield instruments that better distinguish between “popular” and “effective” teaching.

In closing, the misuse of SETs exemplifies how a well-intentioned measurement can backfire when elevated to an incentive criterion (Geraghty, 2024). Universities must remember that not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted. Excellent teaching is a complex, multifaceted endeavor that no single survey item can fully capture. An overemphasis on student evaluations has inadvertently incentivized practices that inflate scores but deflate learning. By adopting a more holistic and judicious approach to evaluating teaching—and by decoupling student feedback from high-stakes consequences—we can realign faculty incentives with the true goals of education. Doing so will encourage instructors to challenge students intellectually without fear, promote equity by not penalizing those unfairly judged by bias, and ultimately foster an academic culture where teaching excellence is measured by the richness of student learning, not the easy applause of student ratings.

References

- ABET. (2025–2026). Criteria for accrediting engineering programs. https://www.abet.org/accreditation/accreditation-criteria/criteria-for-accrediting-engineering-programs-2025-2026/.

- Ambady, N., & Rosenthal, R. (1993). Half a minute: Predicting teacher evaluations from thin slices of nonverbal behavior and physical attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(3), 431–441. [CrossRef]

- American Sociological Association (ASA). (2019, February 13). Statement on student evaluations of teaching. https://www.asanet.org/wp-content/uploads/asa_statement_on_student_evaluations_of_teaching_feb132020.pdf.

- Banas, J. A., Dunbar, N., Rodriguez, D., & Liu, S.-J. (2011). A review of humor in educational settings: Four decades of research. Communication Education, 60(1), 115–144. [CrossRef]

- Basow, S. A., & Martin, J. L. (2012). Bias in student evaluations. College Teaching, 60(1), 21-27. https://ldr.lafayette.edu/concern/publications/fb4948799.

- Boring, A., Ottoboni, K., Stark, P. B. (2016). Student evaluations of teaching (mostly) do not measure teaching effectiveness. ScienceOpen Research, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. In M. Gernsbacher, R. Pew, L. Hough, & J. Pomerantz (Eds.), Psychology and the real world (pp. 56-64). Worth. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3200676.

- Braga, M., Paccagnella, M., & Pellizzari, M. (2014). Evaluating students' evaluations of professors. IZA Discussion Papers, No. 5620. https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/5620/evaluating-students-evaluations-of-professors.

- Bryant, J., Comisky, P. W., Crane, J. S., & Zillmann, D. (1980). Relationship between college teachers’ use of humor in the classroom and students’ evaluations of their teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(4), 511–519. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. T. (1979). Assessing the impact of planned social change. Evaluation and Program Planning, 2(1), 67–90. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S. K., Wilford, M. M., Kornell, N., & Mullaney, K. M. (2013). Appearances can be deceiving: Instructor fluency increases perceptions of learning without increasing actual learning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20, 1350-1356. [CrossRef]

- Carrell, S. E., & West, J. E. (2010). Does professor quality matter? Evidence from random assignment of students to professors. Journal of Political Economy, 118(3), 409–432. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P. A. (1981). Student ratings of instruction and student achievement: A meta-analysis of multisection validity studies. Review of Educational Research, 51(3), 281–309. [CrossRef]

- Dahabreh, I. J., Robertson, S. E., Petito, L. C., Hernán, M. A., & Steingrimsson, J. A. (2023). Efficient and robust methods for causally interpretable meta-analysis: Transporting inferences from multiple randomized trials to a target population. Biometrics, 79(2), 1057–1072. [CrossRef]

- Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(39), 19251–19257. [CrossRef]

- Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2009). Calling and vocation in career psychology: A pathway to purpose. Journal of Career Assessment, 17(3), 331-341. [CrossRef]

- Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. [CrossRef]

- European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education. (2015). Standards and guidelines for quality assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG). https://ehea.info/media.ehea.info/file/2015_Yerevan/72/7/European_Standards_and_Guidelines_for_Quality_Assurance_in_the_EHEA_2015_MC_613727.pdf.

- Feldman, K.A. (1989). The association between student ratings of specific instructional dimensions and student achievement: Refining and extending the synthesis of data from multisection validity studies. Res High Educ 30, 583–645. [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, C. (2019, September 9). Sociologists and more than a dozen other professional groups speak out against student evaluations of teaching. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/09/10/sociologists-and-more-dozen-other-professional-groups-speak-out-against-student.

- Friedland S. (2025, September 11). ‘A for All’: Emory College faculty grapple with grade inflation. The Emory Wheel. Retrieved from https://www.emorywheel.com/article/2025/09/a-for-all-emory-college-faculty-grapple-with-grade-inflation. /: from https.

- Gallup, Inc., & Purdue University. (2014). Great jobs, great lives: The Gallup-Purdue Index report. https://www.purdue.edu/uns/images/2014/gpi-alumnireport14.pdf.

- Geraghty, T. (2024, July 19). Goodhart’s law, Campbell’s law, and the Cobra Effect. Psych Safety. https://psychsafety.com/goodharts-law-campbells-law-and-the-cobra-effect/.

- Gilbert, R.O., Gilbert, D.R. (2025). Student evaluations of teaching do not reflect student learning: an observational study. BMC Med Educ 25, 313. [CrossRef]

- Goodhart, C. A. E. (1984). Problems of monetary management: The UK experience. In Monetary theory and practice: The UK experience (pp. 91–121). London: Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- Gray, K. (2024, December 9). What are employers looking for when reviewing college students’ resumes? National Association of Colleges and Employers. https://www.naceweb.org/talent-acquisition/candidate-selection/what-are-employers-looking-for-when-reviewing-college-students-resumes.

- Hartung, J. (1999). An alternative method for meta-analysis. Biometrical Journal, 41(8), 901–916.

- Hirsch, A. (2025, March 27). What if student evaluations measured what actually matters? Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Retrieved from https://citl.news.niu.edu/2025/03/27/what-if-student-evaluations-measured-what-actually-matters.

- Holmström, B., & Milgrom, P. (1991). Multitask principal-agent analyses: Incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 7(1), 24-52. Retrieved from https://people.duke.edu/~qc2/BA532/1991%20JLEO%20Holmstrom%20Milgrom.pdf.

- Huemer, M. (2001). Student evaluations: A critical review. Unpublished manuscript. https://spot.colorado.edu/~huemer/papers/sef.htm.

- Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. (2024). NSSE 2024 annual results: Engagement insights. National Survey of Student Engagement. https://nsse.indiana.edu/nsse/reports-data/nsse-overview.html.

- IntHout, J., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Rovers, M. M., & Goeman, J. J. (2016). Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 6(7), e010247. [CrossRef]

- Knapp, G., & Hartung, J. (2003). Improved tests for a random-effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Statistics in Medicine, 22(17), 2693-2710. [CrossRef]

- Kogan, V., Genetin, B., Chen, J., & Kalish, A. (2022, January 5). Students' grade satisfaction influences evaluations of teaching: Evidence from individual-level data and an experimental intervention (EdWorkingPaper No. 22-513). Annenberg Institute at Brown University. [CrossRef]

- Kornell, N. (2013, May 31). Do the best professors get the worst ratings? Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/everybody-is-stupid-except-you/201305/do-the-best-professors-get-the-worst-ratings.

- Knapp, G., & Hartung, J. (2003). Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Statistics in Medicine, 22(17), 2693–2710. [CrossRef]

- MacNell, L., Driscoll, A., & Hunt, A. N. (2015). What’s in a name: Exposing gender bias in student ratings of teaching. Innovative Higher Education, 40(4), 291–303. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., & Roche, L. A. (1997). Making students’ evaluations of teaching effectiveness effective: The critical issues of validity, bias, and utility. American Psychologist, 52(11), 1187–1197. [CrossRef]

- Messick, S. (1995). Validity of psychological assessment: Validation of inferences from persons’ responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. American Psychologist, 50(9), 741–749. [CrossRef]

- Naftulin, D. H., Ware, J. E., Jr., & Donnelly, F. A. (1973). The Doctor Fox lecture: A paradigm of educational seduction. Journal of Medical Education, 48(7), 630–635. [CrossRef]

- National Association of Colleges and Employers. (2025a, January). Job Outlook 2025. https://www.naceweb.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/2025/publication/research-report/2025-nace-job-outlook-jan-2025.pdf.

- National Association of Colleges and Employers. (2025b, January 13). The gap in perceptions of new grads’ competency proficiency and resources to shrink it. https://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/the-gap-in-perceptions-of-new-grads-competency-proficiency-and-resources-to-shrink-it.

- Orwin, R. G. (1983). A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Statistics, 8(2), 157-159. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., … & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [CrossRef]

- Radavoi, C.N., Quadrelli, C. & Collins, P. (2025). Moral Responsibility for Grade Inflation: Where Does It Lie?. J Acad Ethics. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, P. (1996). Generation X goes to college: An eye-opening account of teaching in post-modern America. Open Court. https://www.petersacks.org/generation_x_goes_to_college__an_eye_opening_account_of_teaching_in_postmodern_am_2221.htm.

- Sangwa, S., & Mutabazi, P. (2025). Mission-Driven Learning Theory: Ordering Knowledge and Competence to Life Mission. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Sixbert, S. , Titus L., Simeon N., Placide M. (2025). Expertise-Autonomy Equilibria in African Higher Education: A Systematic Review of Student-Centred Pedagogies and Graduate Readiness. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS), 9(03), 5419-5432. [CrossRef]

- Sparks, S. D. (2011, April 26). Studies find 'desirable difficulties' help students learn. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/studies-find-desirable-difficulties-help-students-learn/2011/04.

- Stark, P. B., & Freishtat, R. (2014). An evaluation of course evaluations. ScienceOpen Research. https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.14293/S2199-1006.1.SOR-EDU.AOFRQA.v1.

- Sterne, J. A. C., & Egger, M. (2001). Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: Guidelines on choice of axis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(10), 1046-1055. [CrossRef]

- Uttl, B., White, C. A., & Gonzalez, D. W. (2017). Meta-analysis of faculty's teaching effectiveness: Student evaluation of teaching ratings and student learning are not related. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 54, 22–42. [CrossRef]

- Zumbo, B.D. (1999). A Handbook on the Theory and Methods of Differential Item Functioning (DIF) LOGISTIC REGRESSION MODELING AS A UNITARY FRAMEWORK FOR BINARY AND LIKERT-TYPE (ORDINAL) ITEM SCORES. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-Handbook-on-the-Theory-and-Methods-of-Item-(DIF)-Zumbo/7f88fb0ad98645582665532600d7c46406fa2db6.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

S = denotes satisfaction-visible effort, L = learning-invisible effort, Ws = the institutional weight on SET, and α parameters capture marginal disutility. Calibrate Ws = 0.2 using the promotion weighting simulated above; derive the first-order conditions showing a 23% effort reallocation toward S when Ws rises from 0.05 to 0.20.

S = denotes satisfaction-visible effort, L = learning-invisible effort, Ws = the institutional weight on SET, and α parameters capture marginal disutility. Calibrate Ws = 0.2 using the promotion weighting simulated above; derive the first-order conditions showing a 23% effort reallocation toward S when Ws rises from 0.05 to 0.20.