Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Nomenclature (in Alphabetical Order; Greek Symbols First)

| Relaxation factor used in adjusting the progression rate to account for the effect of a foundation year (if applicable) | |

| Discount factor for extrapolating first-year retention rates, from 0 to 1 | |

| Discount factor for extrapolating first-year progression rates, from 0 to 1 | |

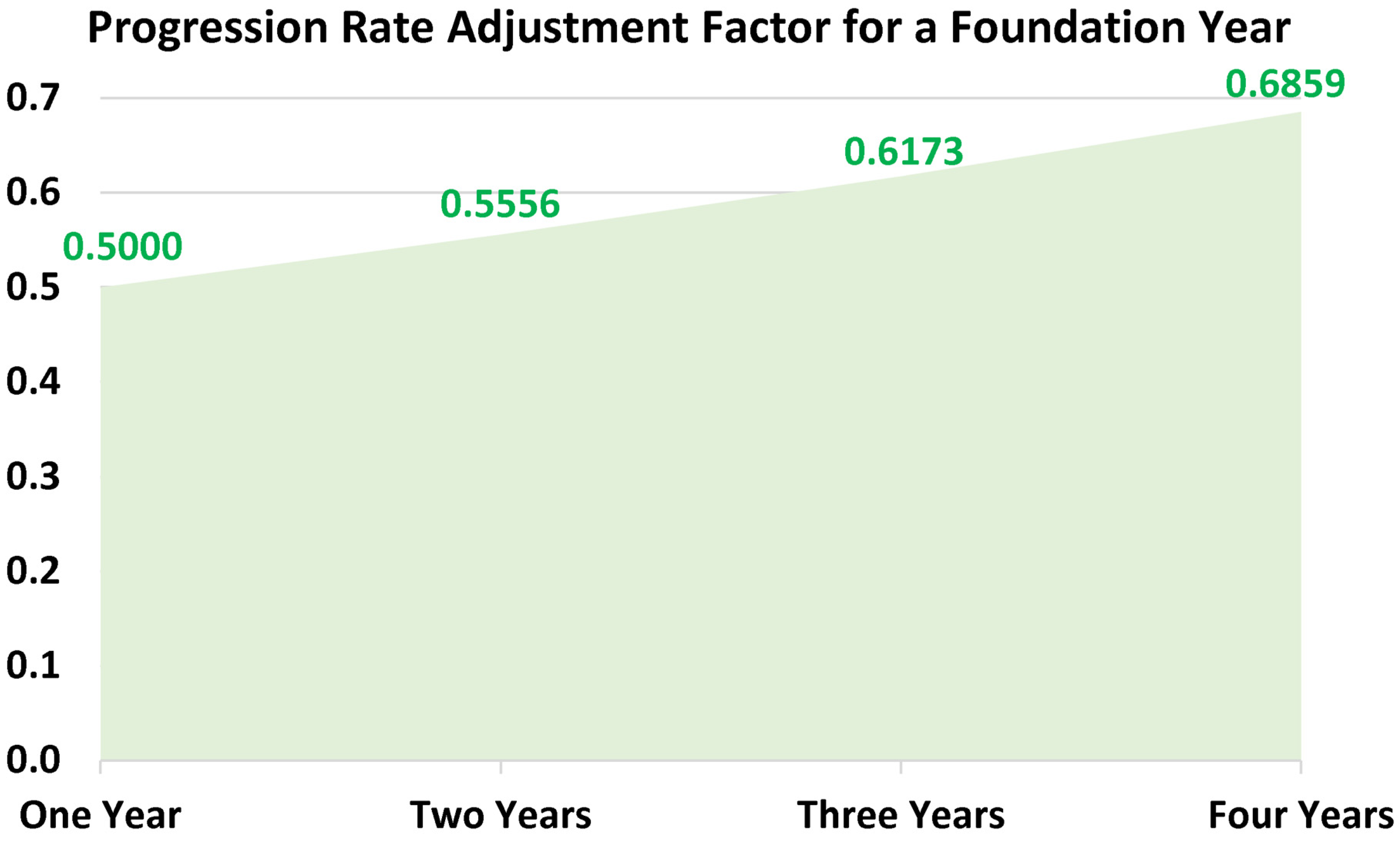

| Progression rate adjustment factor (or penalty factor) to account for the effect of a foundation year (if applicable) | |

| AR | Attrition rate (the complement of the retention rate; their sum is always 100%) |

| CR | Completion rate (same as the graduation rate) |

| CR′ | Scaled completion rate for a perfect 0-100% range (proposed, but not used here) |

| DR | Dropout rate (same as the attrition rate) |

| ED | United States Department of Education |

| GR | Graduation rate, equivalently called “completion rate” |

| GR′ | Scaled graduation rate for a perfect 0-100% range (proposed, but not used here) |

| HE | Higher education (equivalently “postsecondary education” or “tertiary education”) |

| HEI | Higher education institution (a university, academic institute, academy, or a standalone college) |

| IES | Institute of Education Sciences (part of ED) |

| NCEE | National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (one of four centers under IES) |

| NCER | National Center for Education Research (one of four centers under IES) |

| NCES | National Center for Education Statistics (one of four centers under IES) |

| NCSER | National Center for Special Education Research (one of four centers under IES) |

| IPEDS | Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (a system of annual data collection about higher education, conducted by NCES) |

| NSC-RC | National Student Clearinghouse – Research Center (located in the state of Virginia, USA) |

| PR | Progression rate (when defined as a modified version of the retention rate; we refer to this form of progression rate as the “expanded retention rate”), equivalently called “persistence rate” or “progress rate” (this is the type actually adopted in the date used by this study) |

| Average progression rate over four consecutive years | |

| Progression rate (when defined as a measure of the satisfactory pace of students’ advancement in their study within the same institution or degree program; we refer to this form of progression rate as the “within-institution/program study advancement” or simply the “within-institution/program”), equivalently called “persistence rate” or “progress rate” (explained, but not used here) | |

| Adjusted for the influence foundation year | |

| ′ | Scaled for a perfect 0-100% range (proposed, but not used here) |

| ′′ | Scaled performance-based (proposed, but not used here) |

| RR | Retention Rate |

| Average retention rate over four consecutive years |

2. Introduction

2.1. Background

2.2. Goal of the Study

3. Research Method

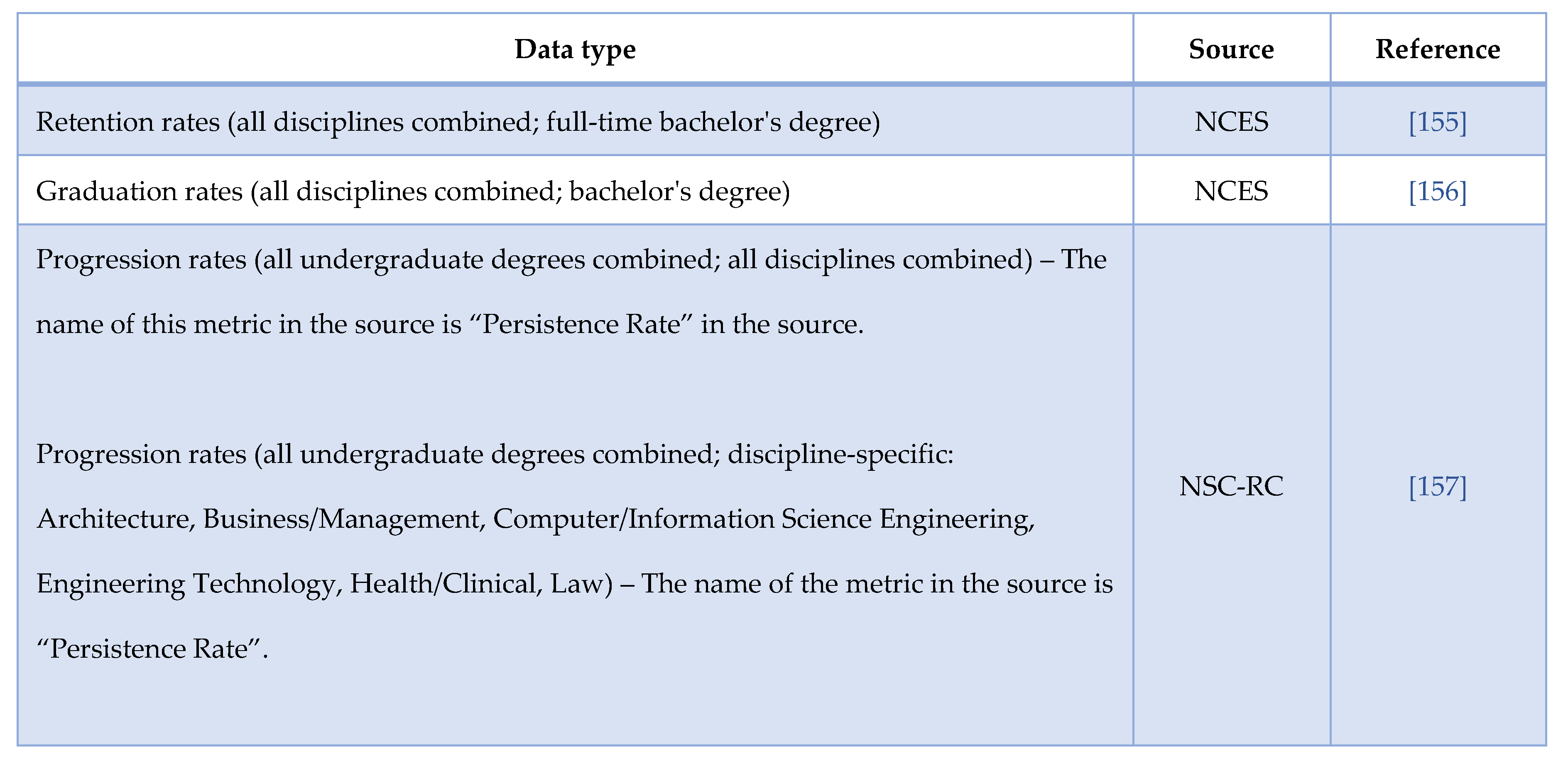

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Retention and Progression Extrapolation

3.3. Progression Adjustment for Foundation Year

4. Results

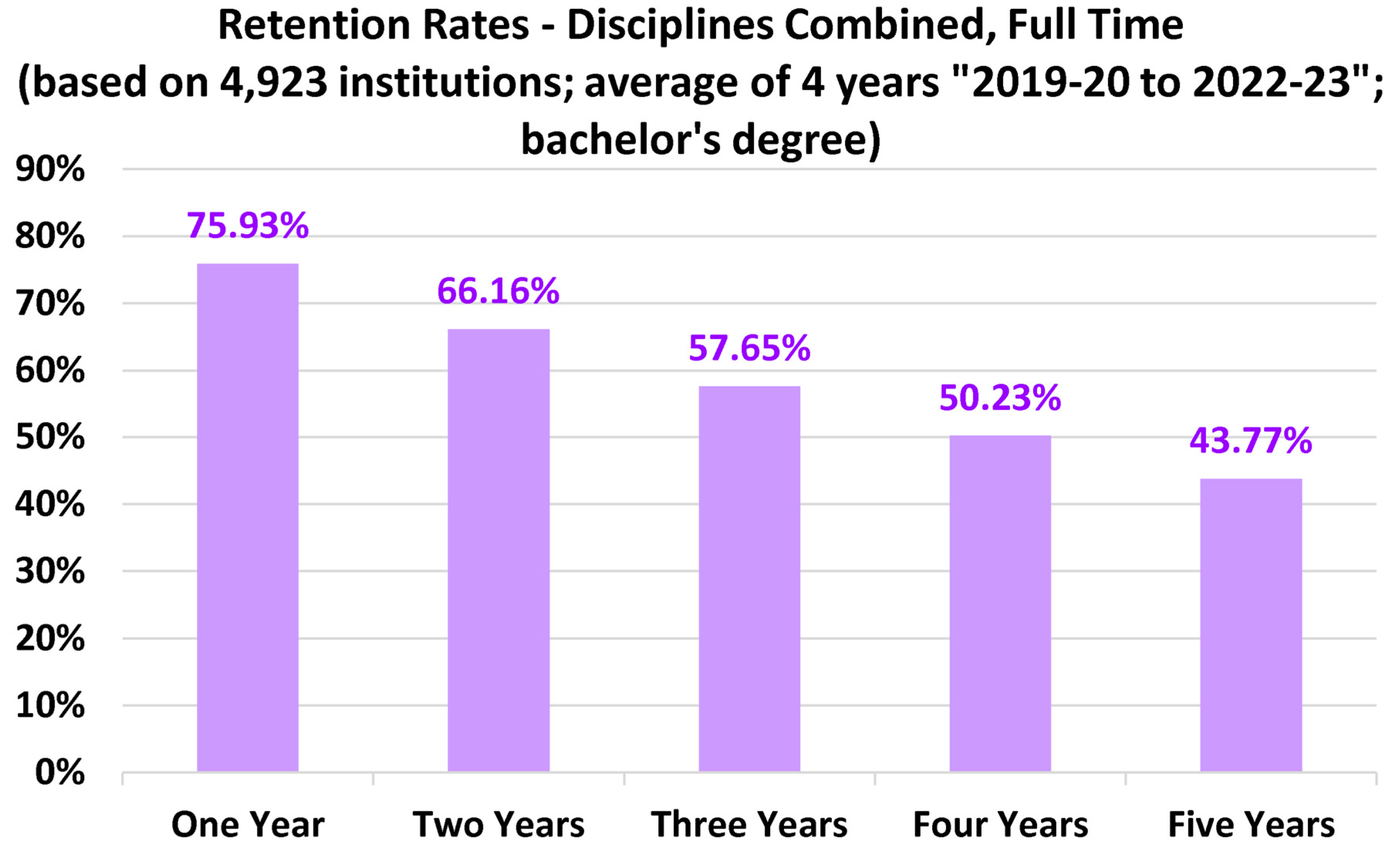

4.1. Overall Full-Time Bachelor’s Degree Retention Rates

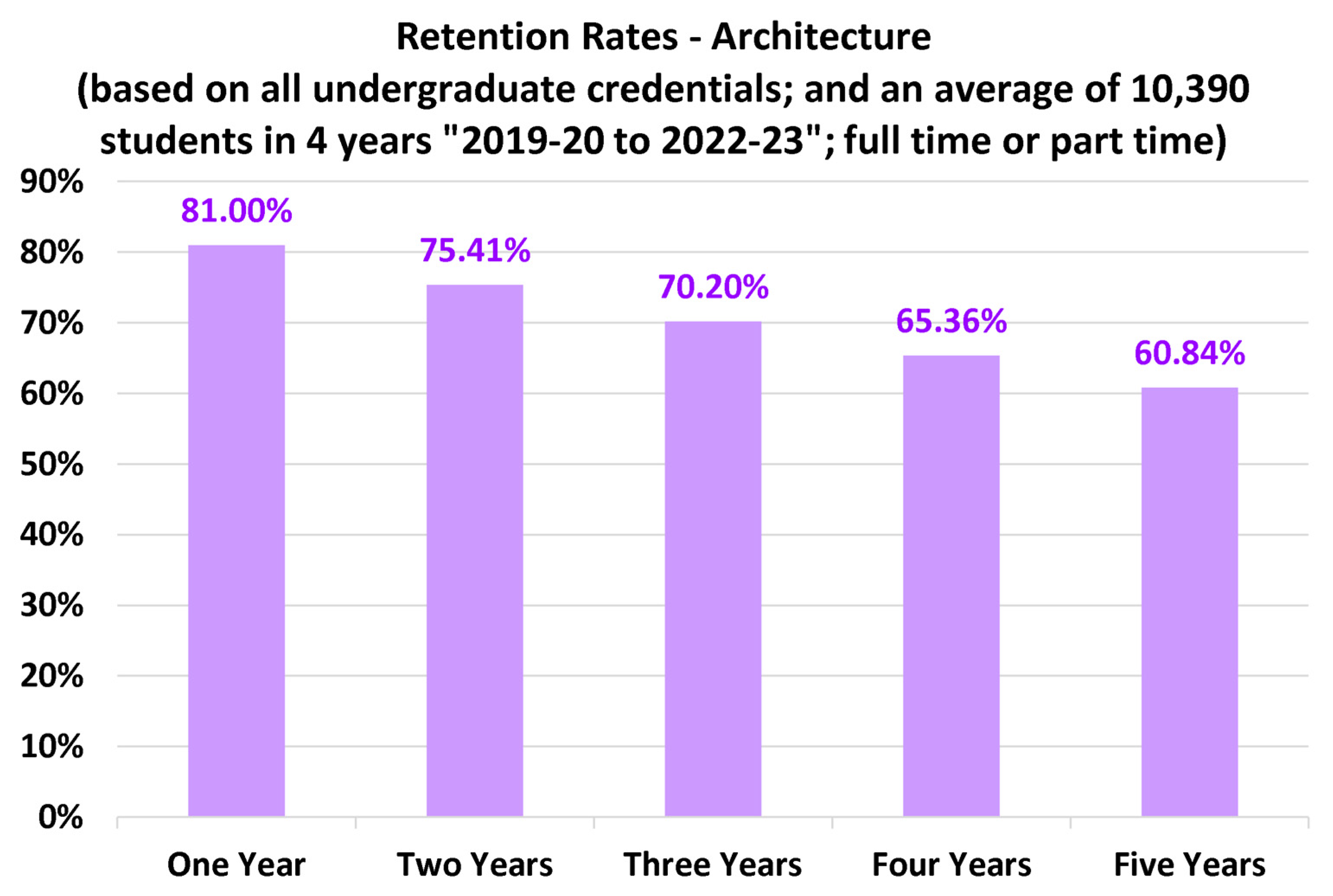

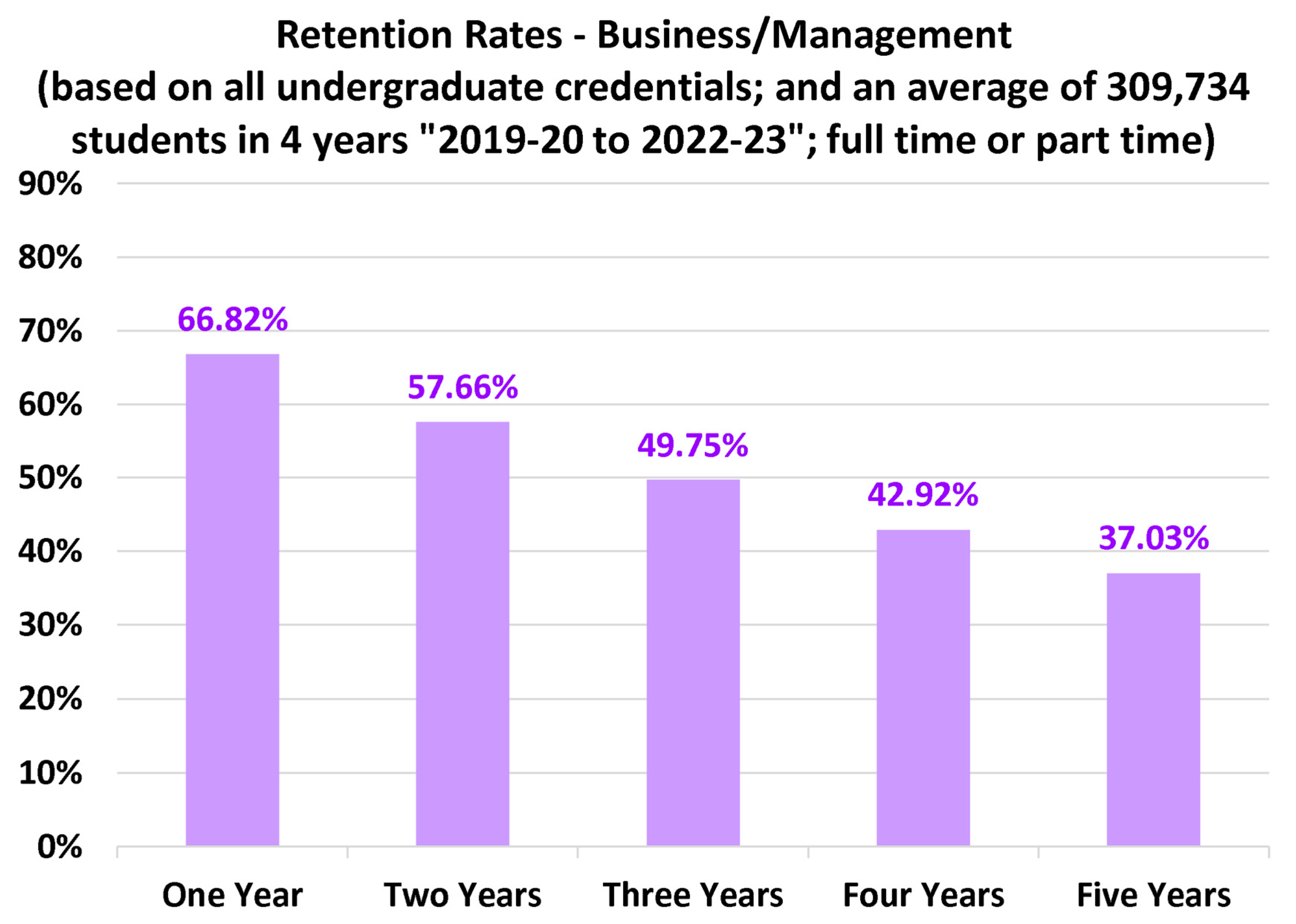

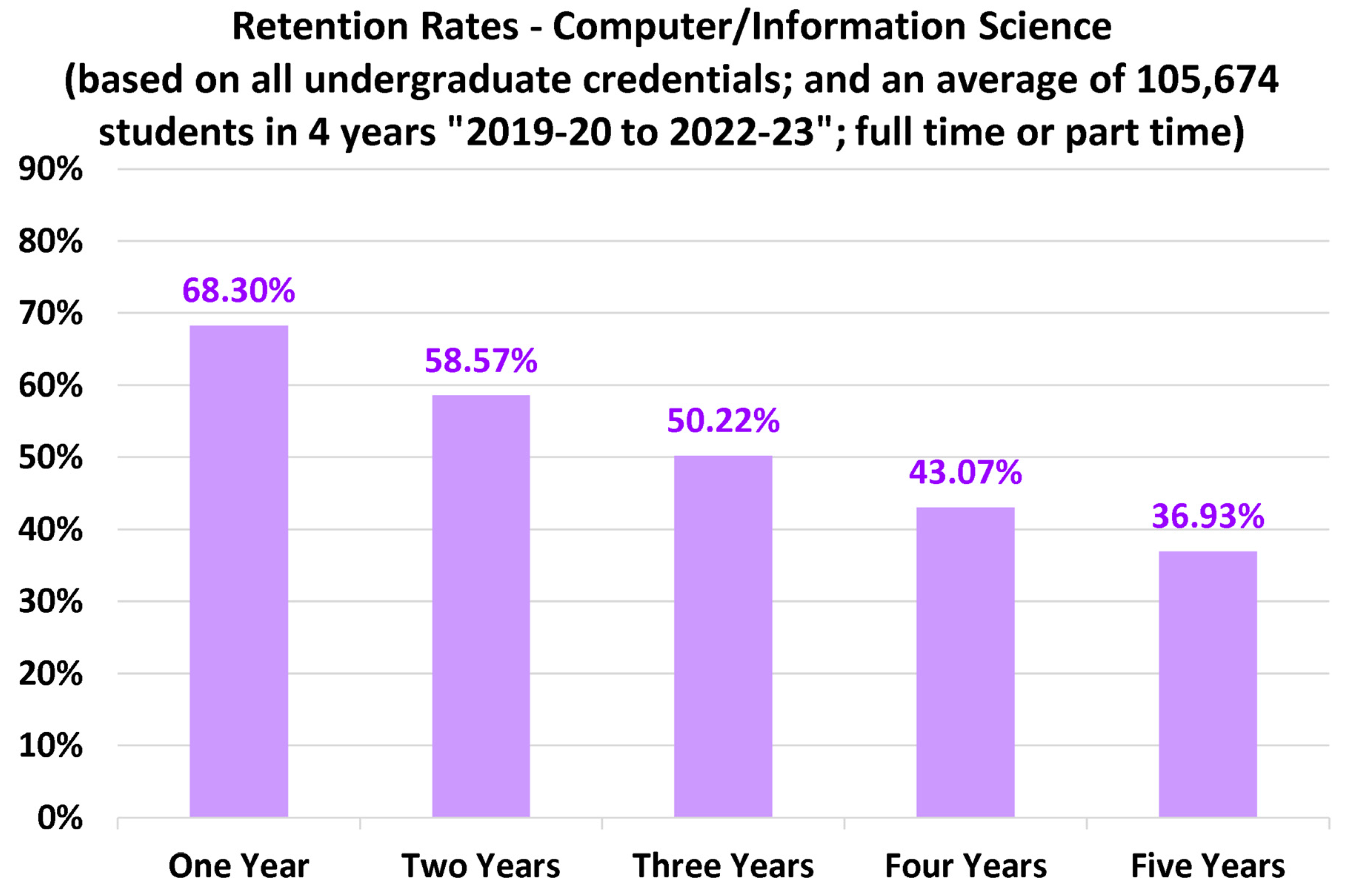

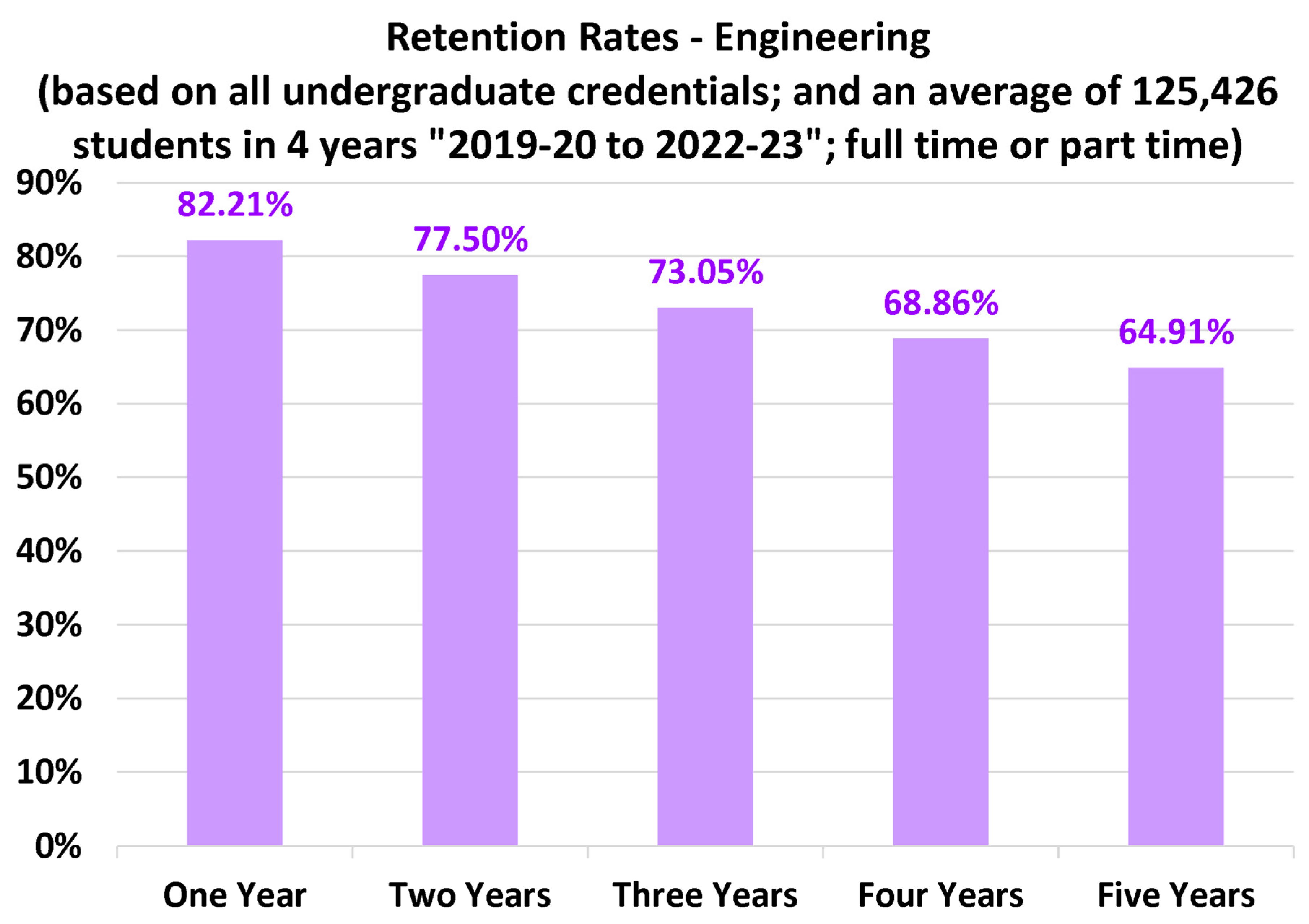

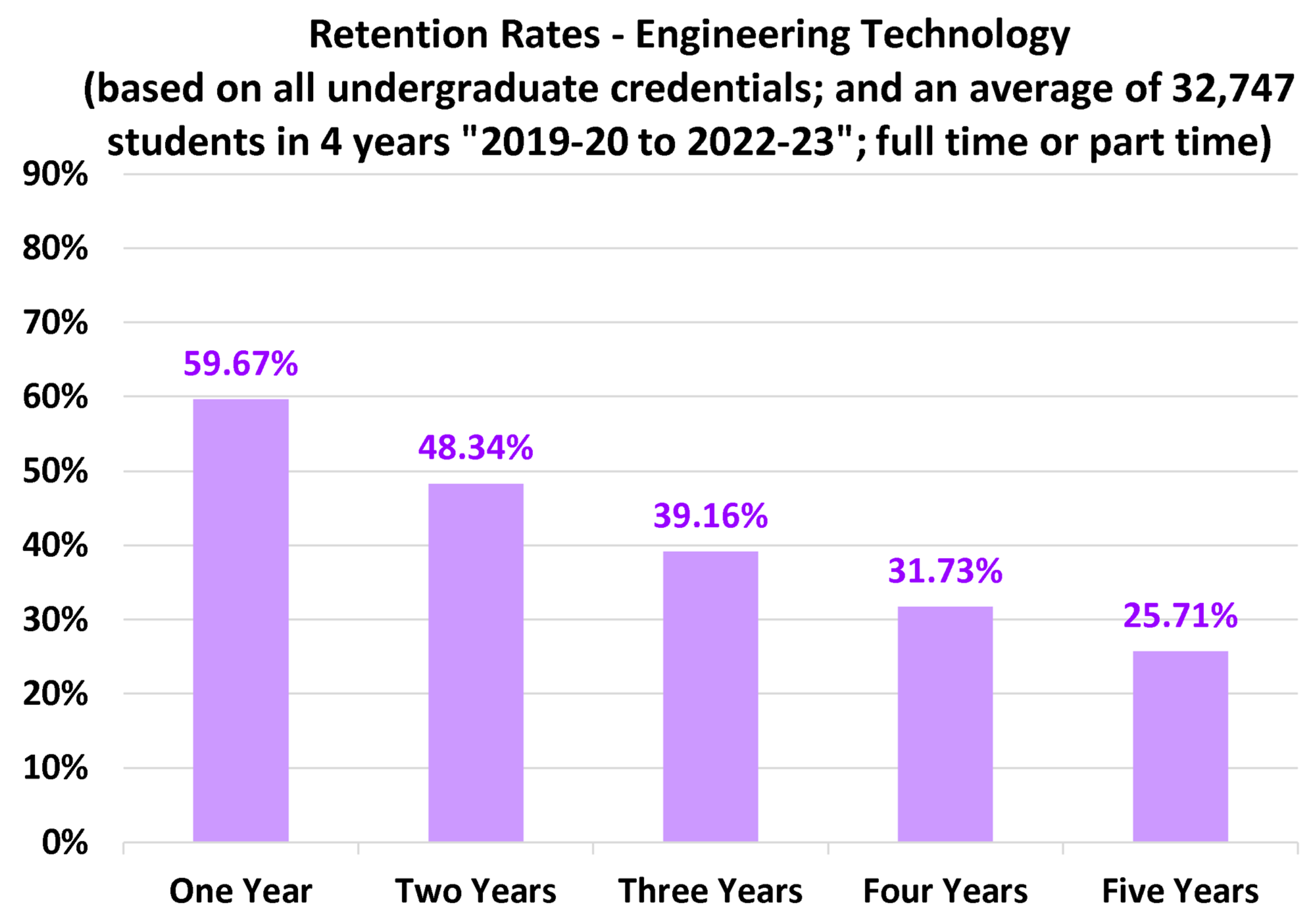

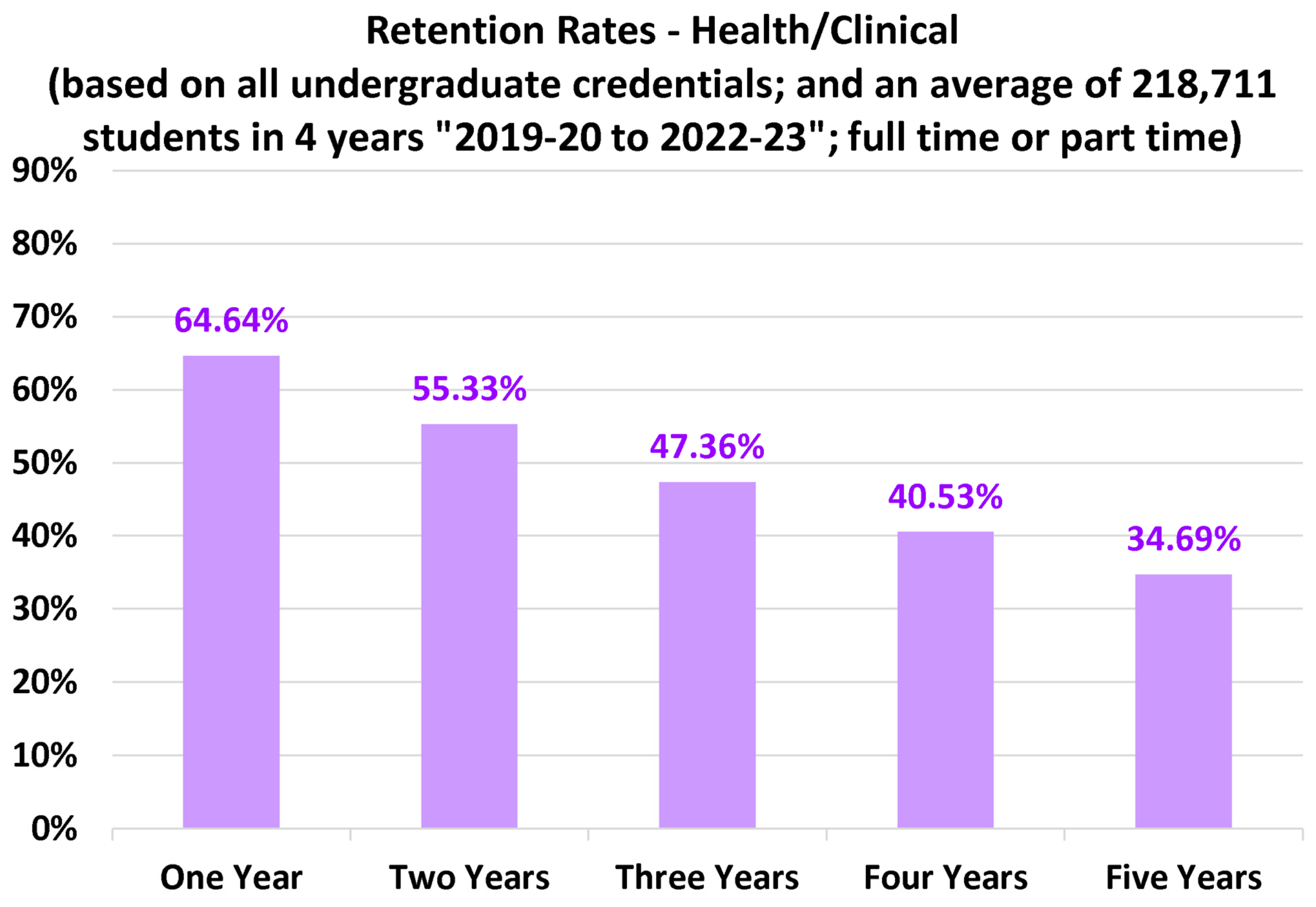

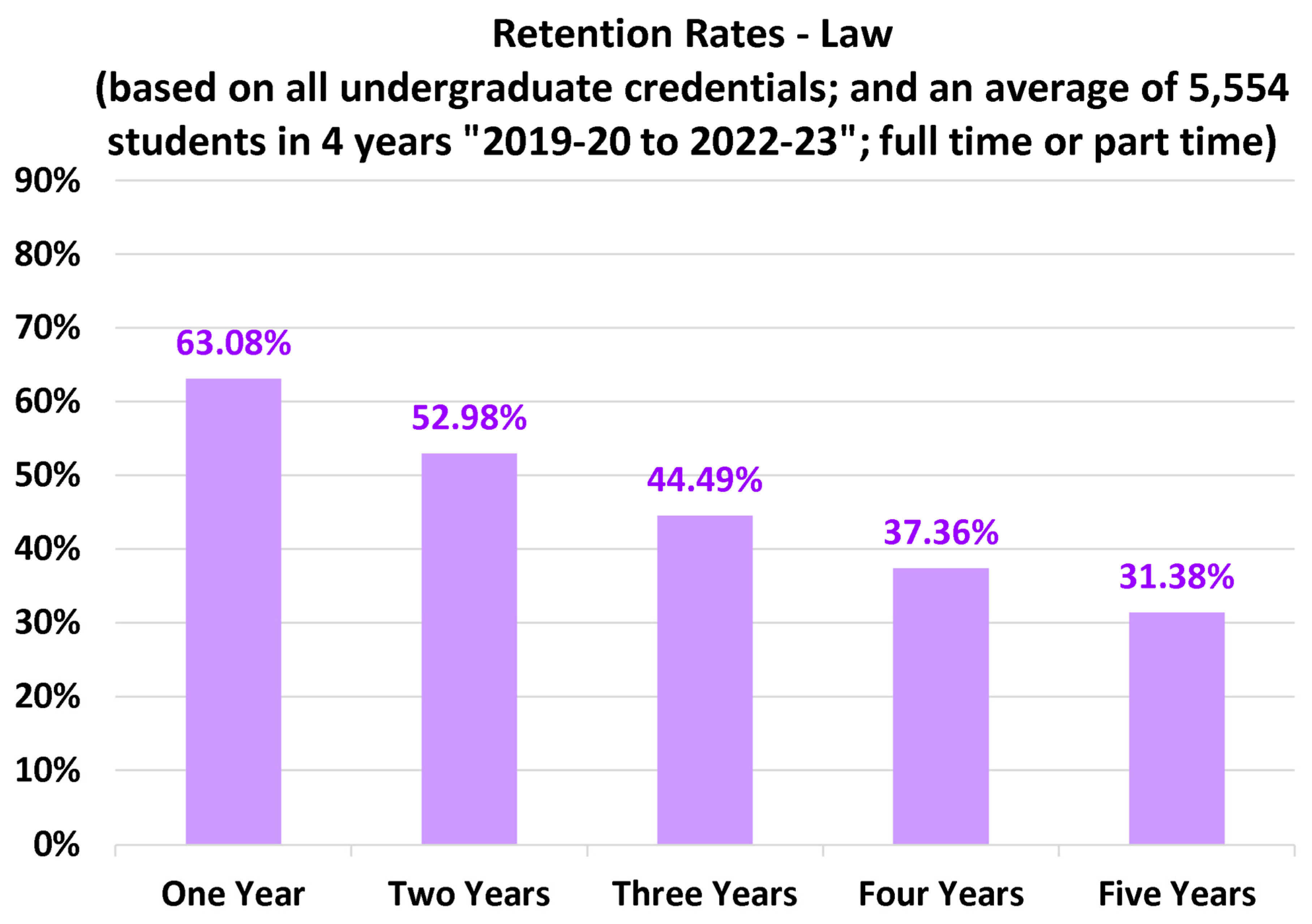

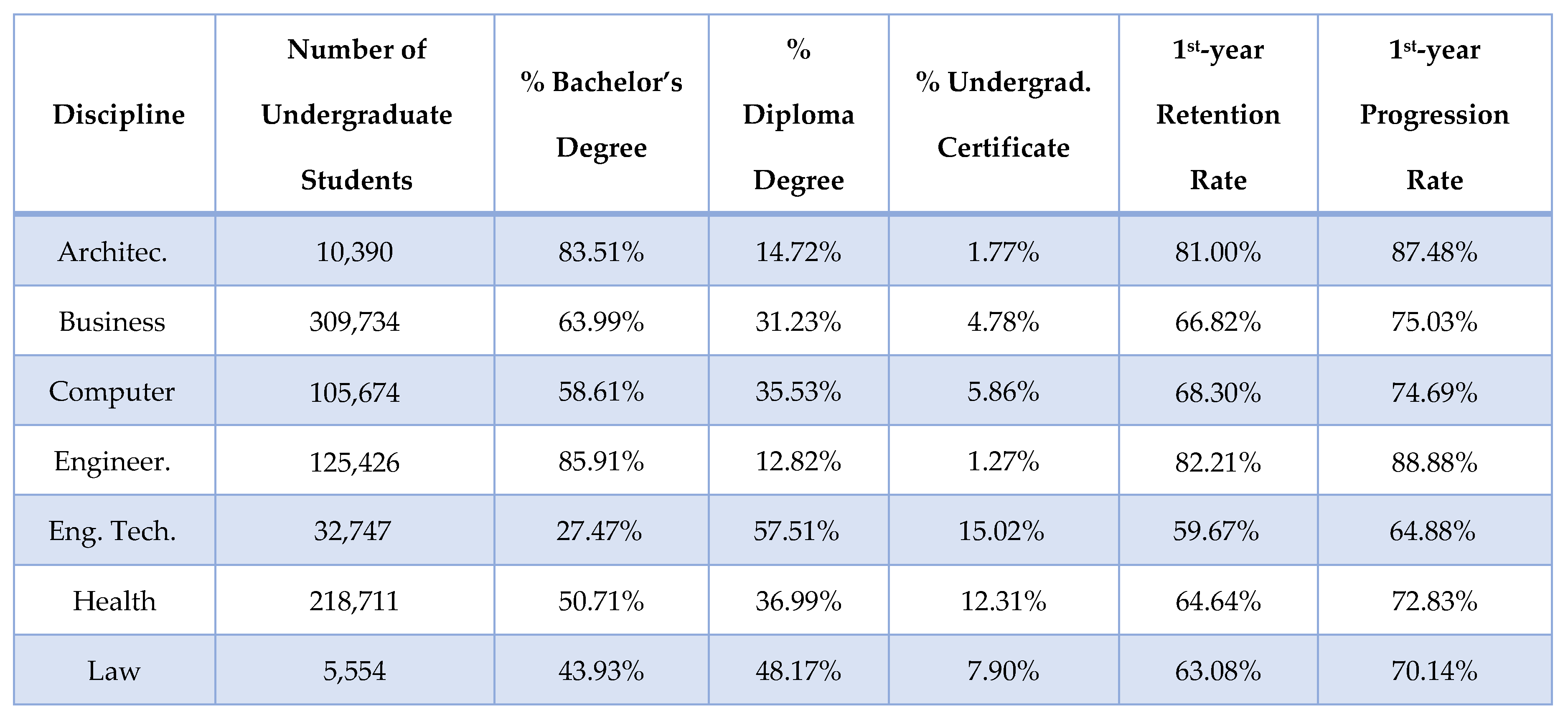

4.2. Discipline-Specific Retention Rates

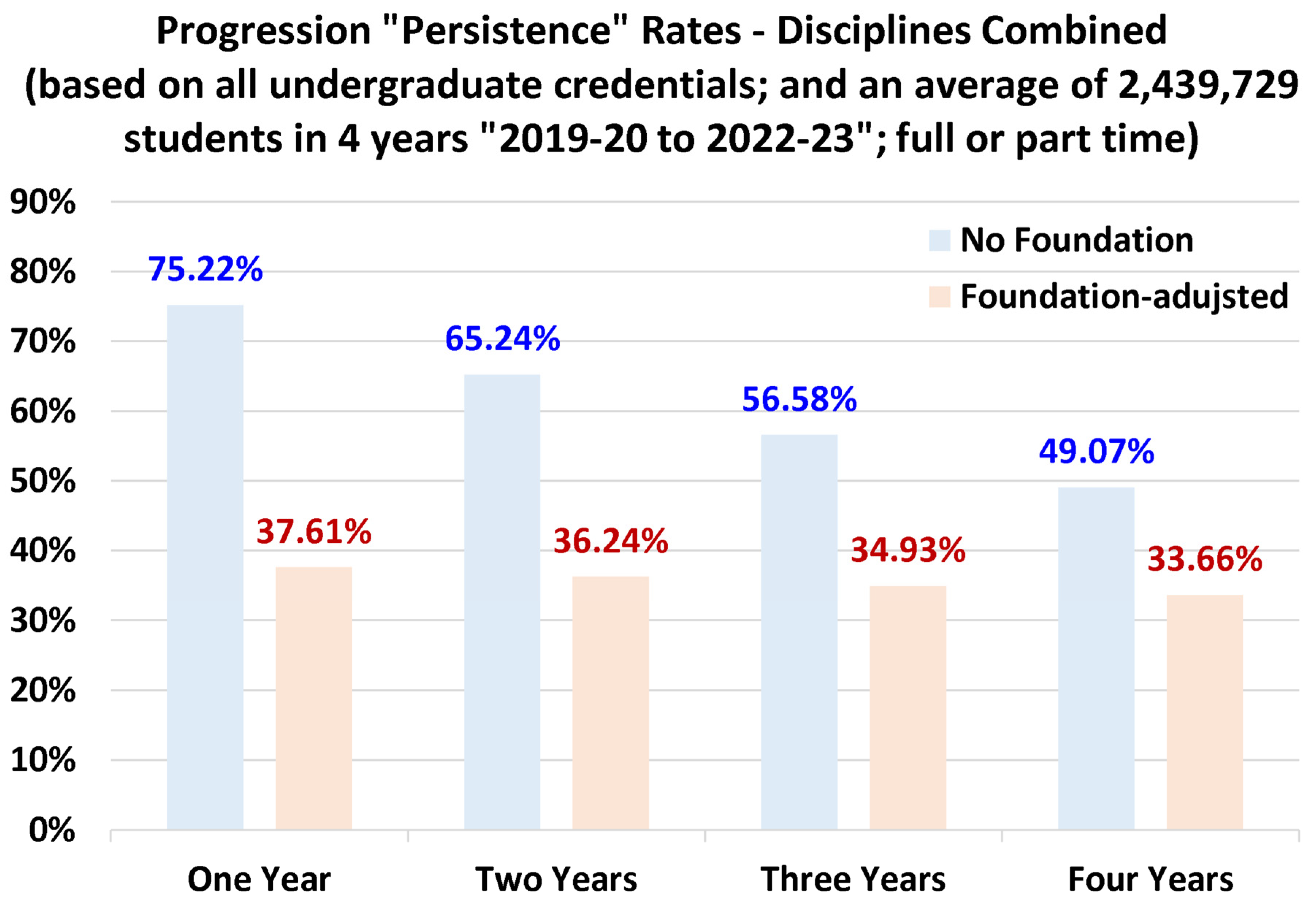

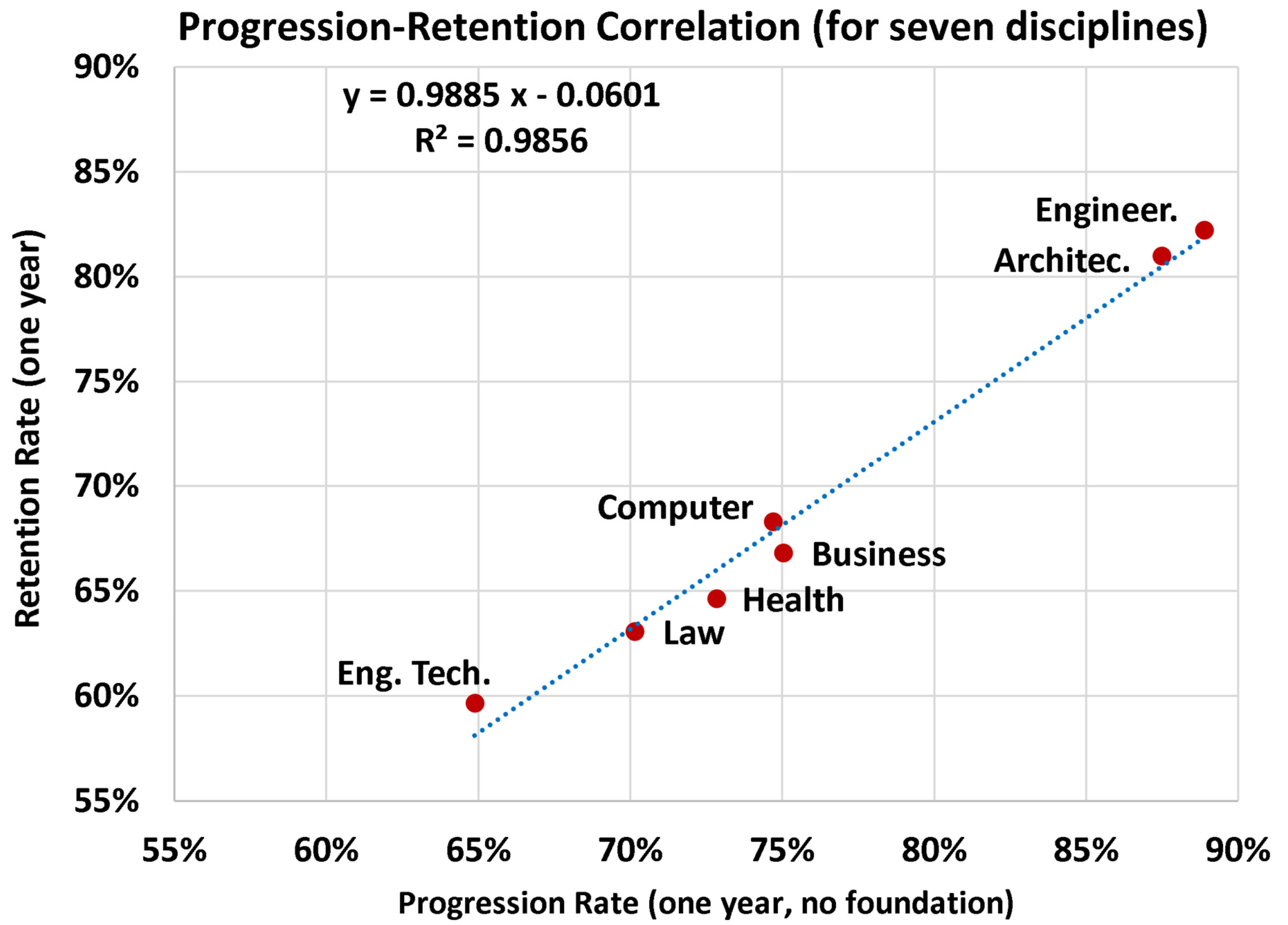

4.3. Overall Progression Rates

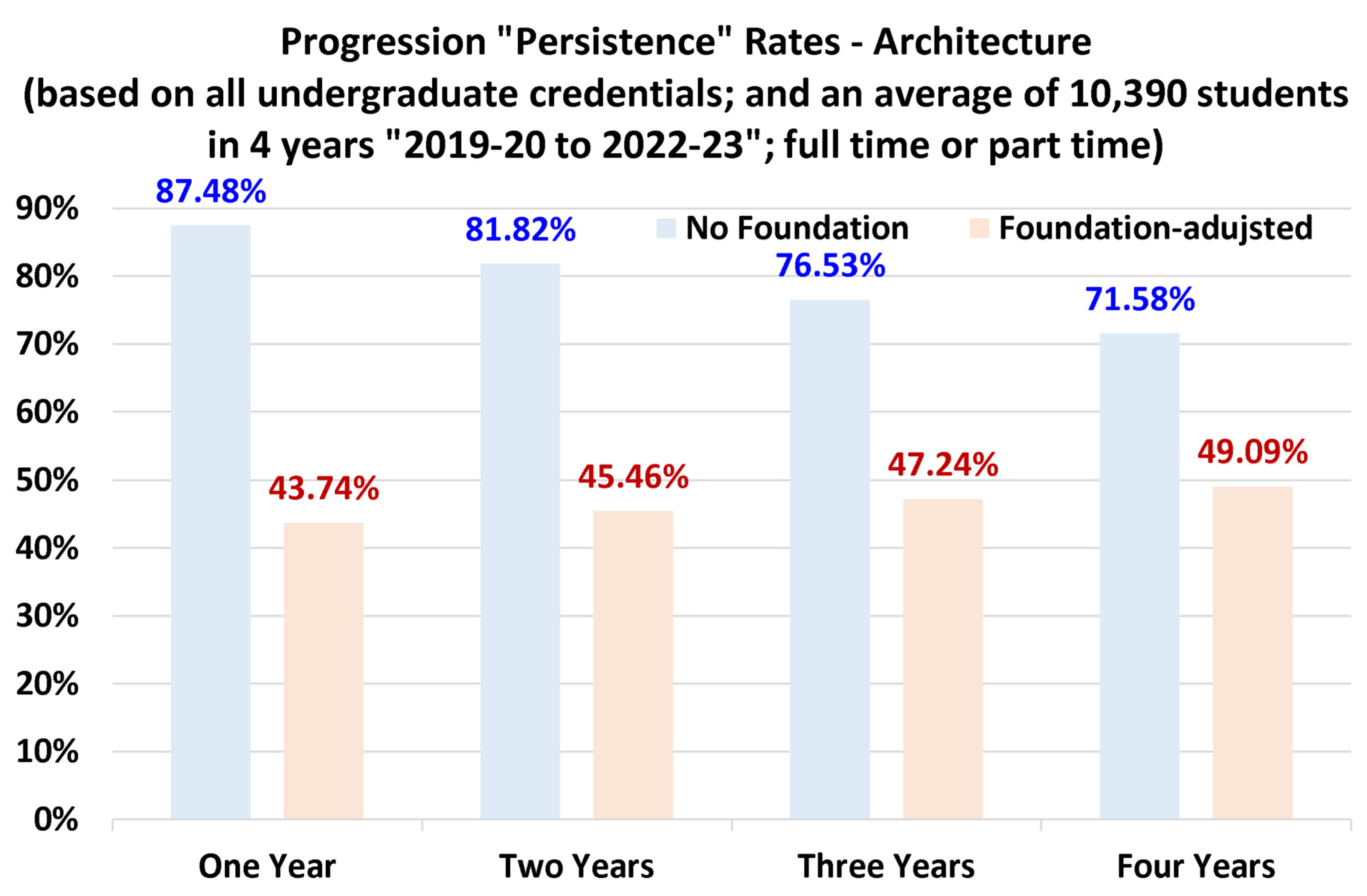

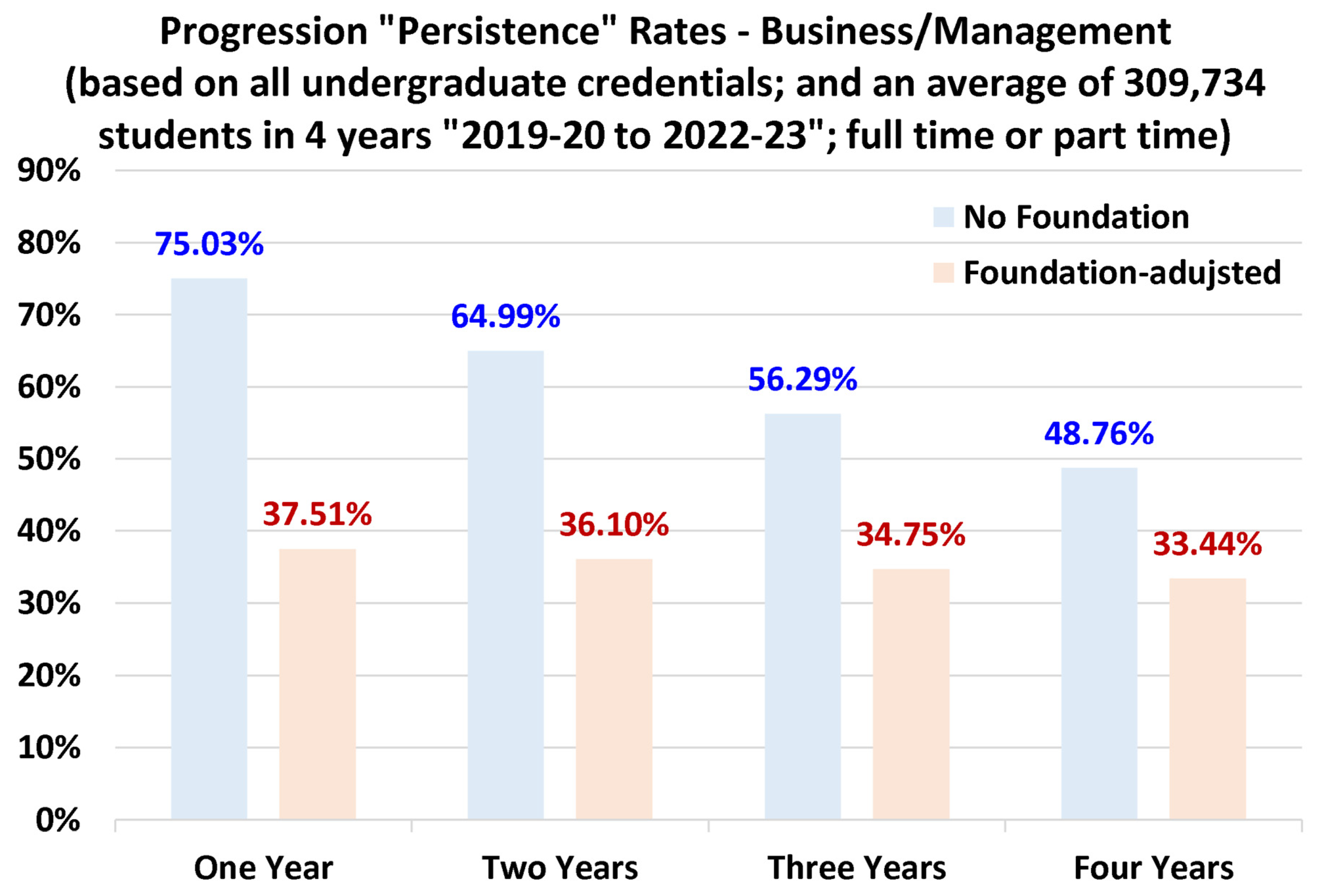

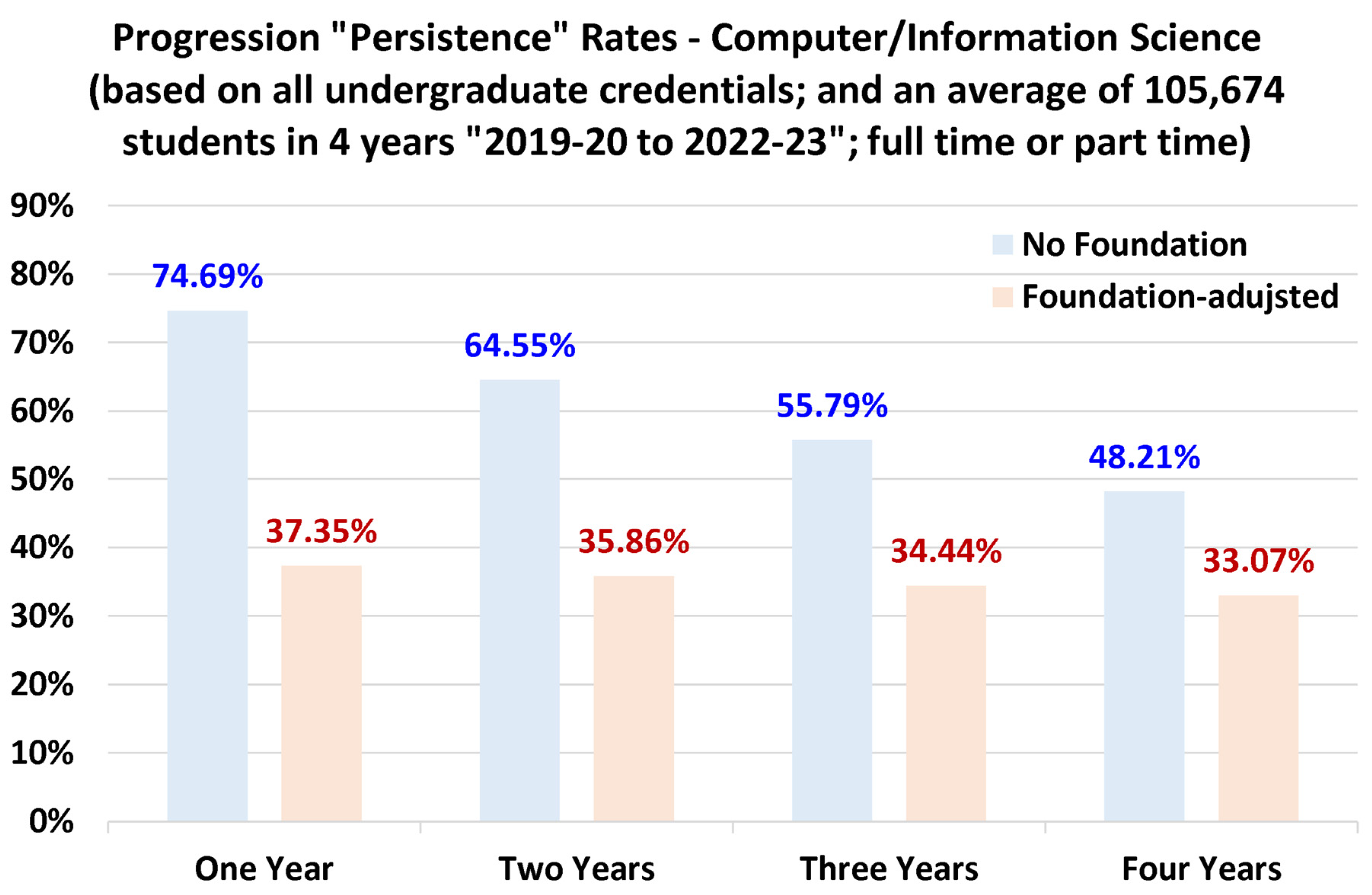

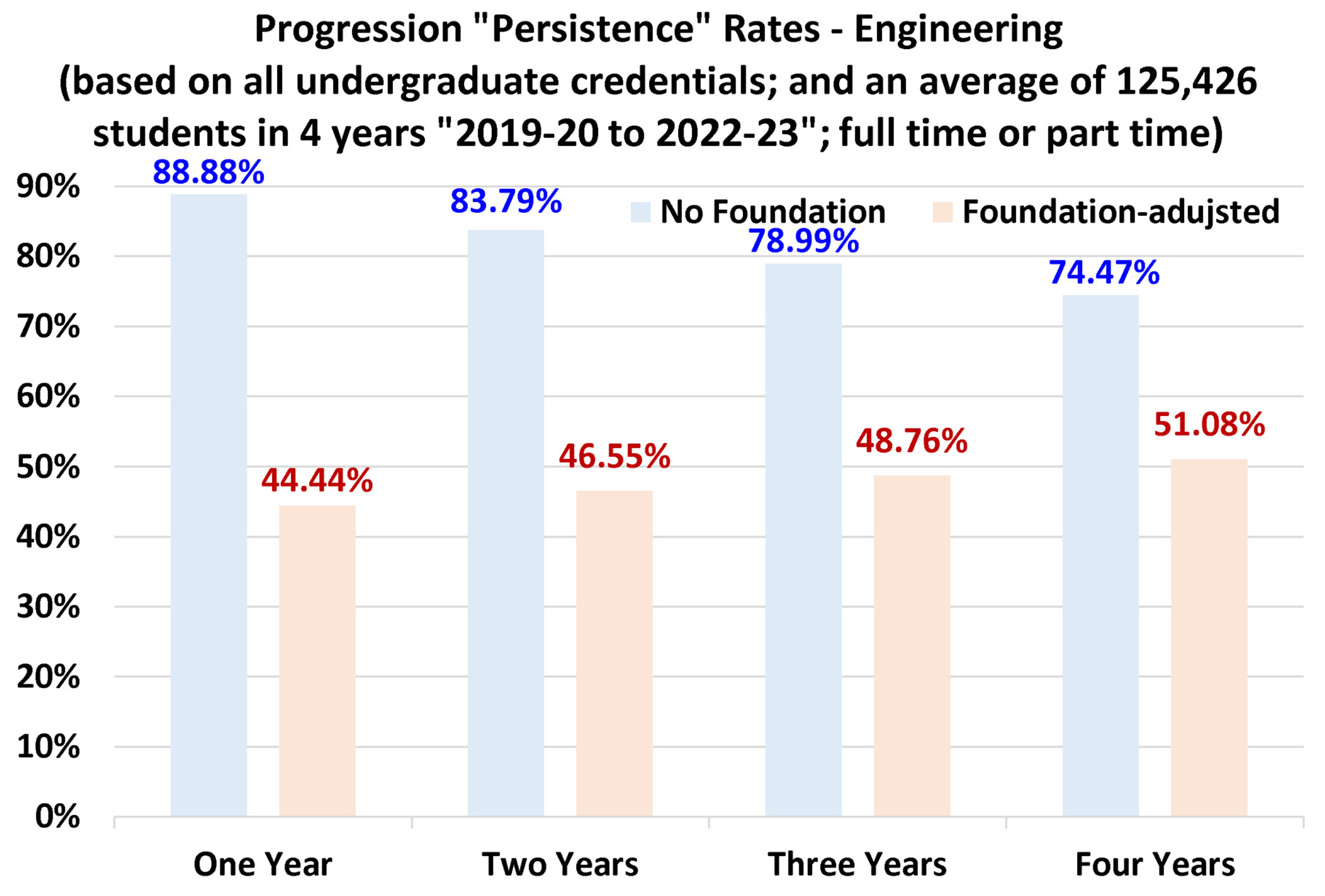

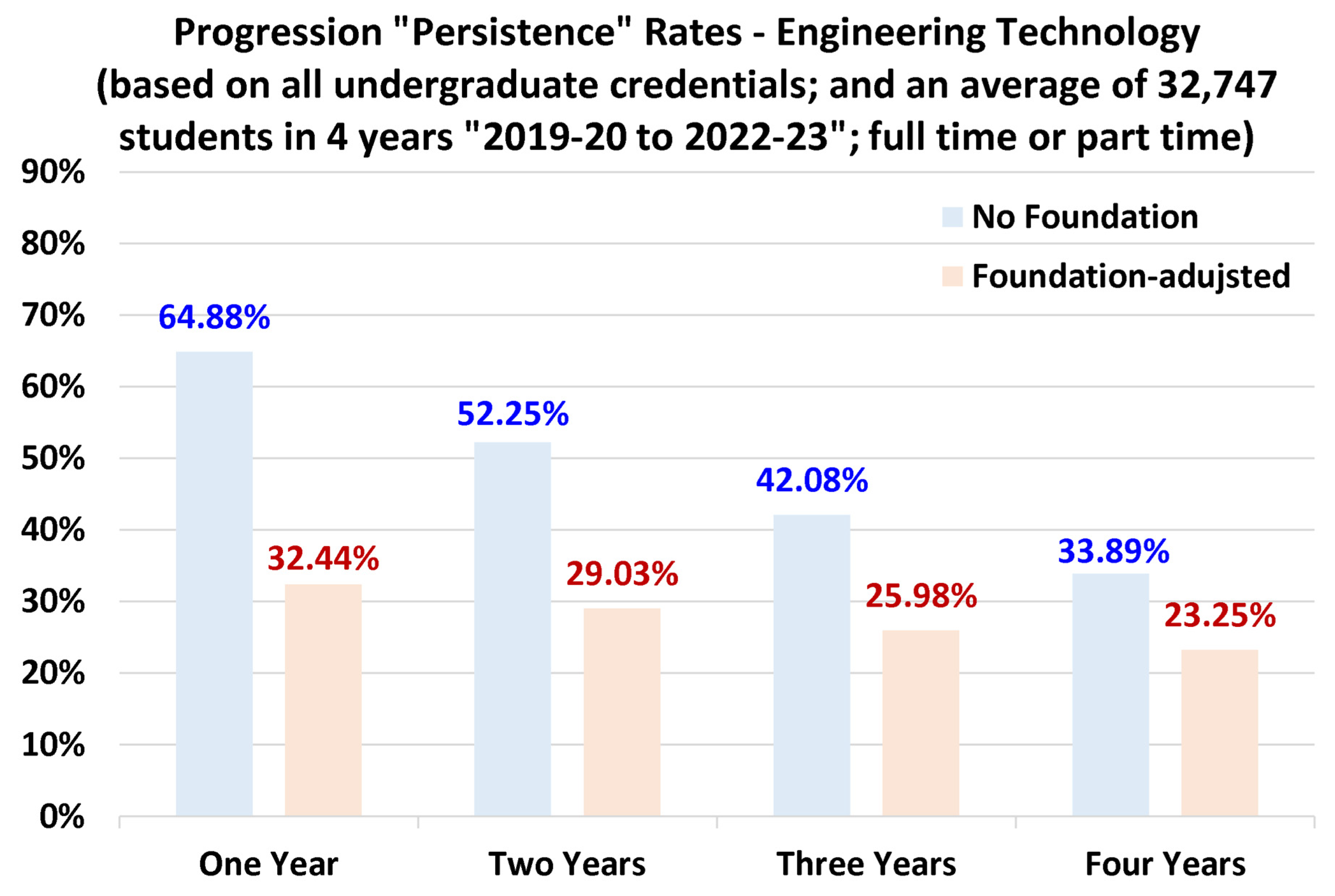

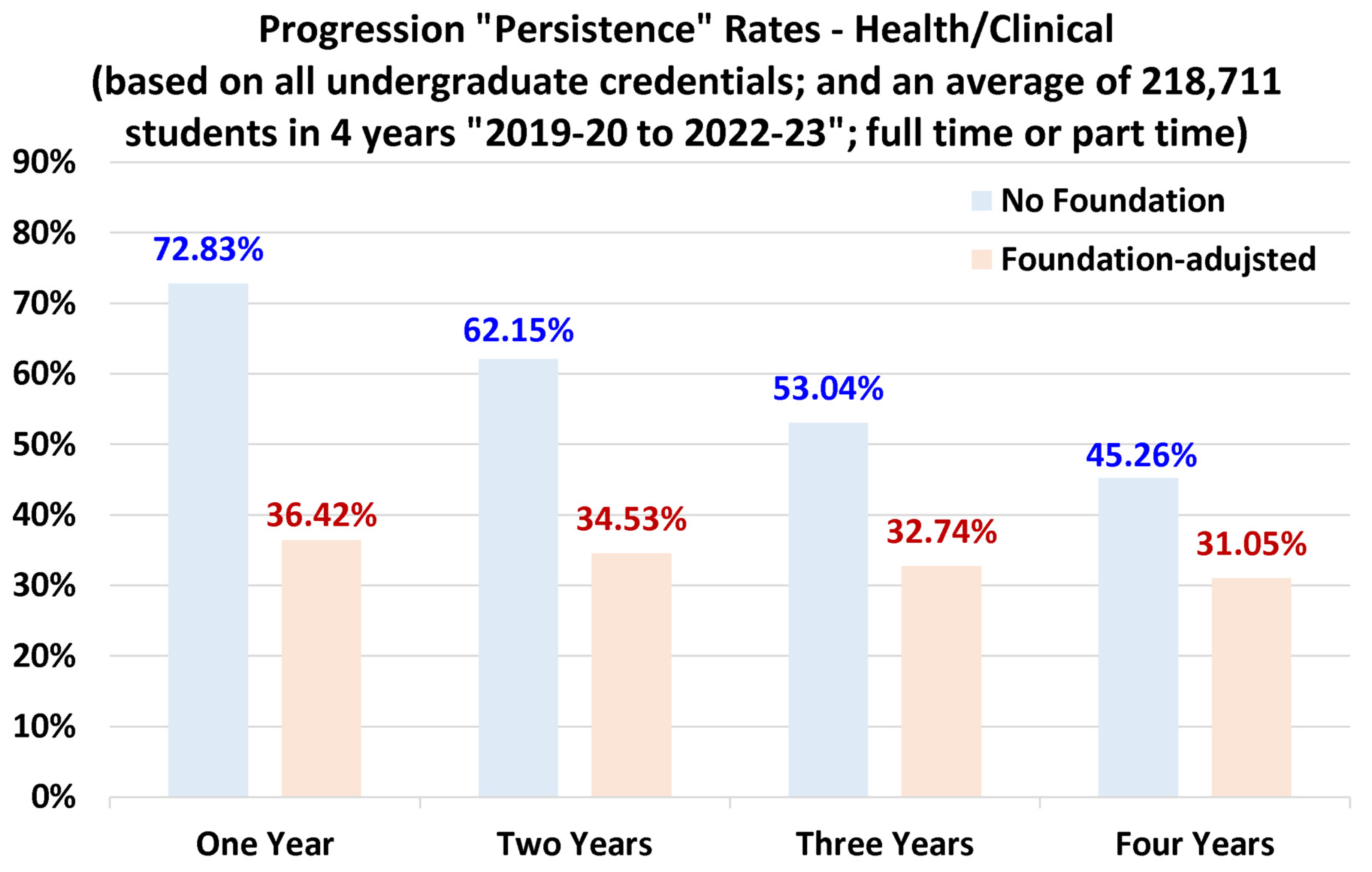

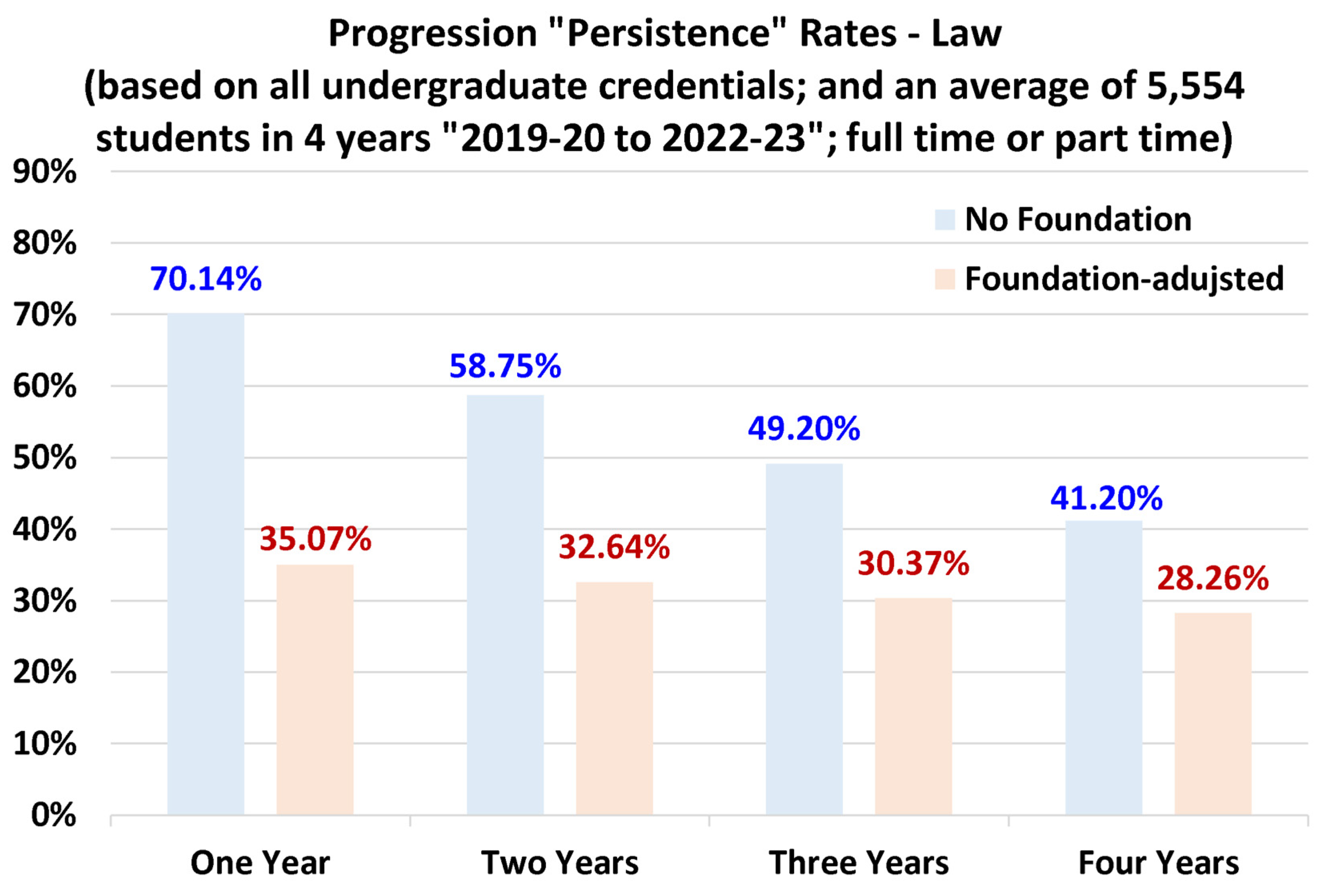

4.4. Discipline-Specific Progression Rates

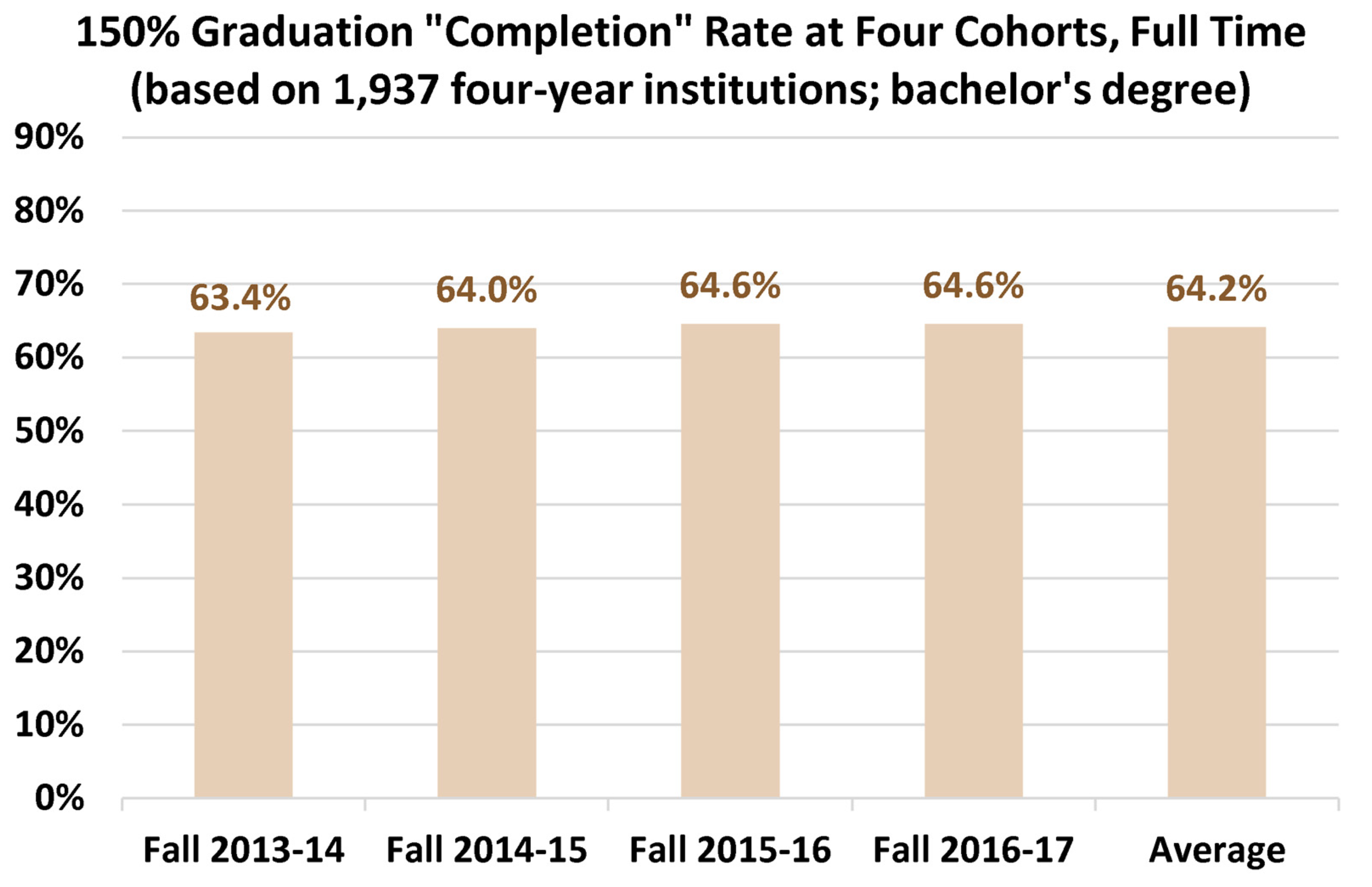

4.5. General Full-Time Bachelor’s Degree Graduation Rates

4.6. Retention-Progression Correlation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Overall, the recommended benchmarking first-year retention rate for bachelor’s degree students is 76%.

- Overall, the recommended benchmarking first-year progression rate for undergraduate students admitted directly to the degree program is 75%.

- Overall, the recommended benchmarking graduation rate for bachelor’s degree students within 150% of the nominal study period is 64%.

- Among the seven disciplines examined here, engineering and architecture have similarly high retention rates, progression rates, as well as portions of bachelor’s degree students (as compared to diploma/associate degree students).

- Among the seven disciplines examined here, engineering technology has the lowest retention rates, progression rates, as well as the portion of bachelor’s degree students (as compared to diploma/associate degree students).

- The progression (or persistence) rate is more ambiguous compared to the retention rate and the graduation rate, with multiple definitions existing in the literature for it. Thus, one should be more cautious when dealing with reported progression (persistence) rates. The other two rates can also be defined differently by different sources, but their overall purpose seems to be less scattered.

Supplementary Material or Data Availability Statement

Declaration of Competing Interests Statement

Funding

References

- [Oman Authority for Academic Accreditation and Quality Assurance of Education] OAAAQA, Oman Qualifications Framework (OQF) Document, Version 3, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2023. https://oaaaqa.gov.om/getattachment/5b4dda1a-c892-48bc-afb9-7b39d1d8611f/OQF%20Document.aspx (accessed October 8, 2024).

- L. Wheelahan, From old to new: the Australian qualifications framework, Journal of Education and Work 24 (2011) 323–342. [CrossRef]

- M. Young, Qualifications Frameworks: some conceptual issues, European Journal of Education 42 (2007) 445–457. [CrossRef]

- M.F.D. Young, National Qualifications Frameworks as a Global Phenomenon: A comparative perspective, Journal of Education and Work (2003). [CrossRef]

- E. Davenport, B. Cronin, Knowledge management, performance metrics, and higher education: Does it all compute?, New Review of Academic Librarianship (2001). [CrossRef]

- D. Palfreyman, Markets, models and metrics in higher education, Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education 11 (2007) 78–87. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Benchmarks for the Omani higher education students-faculty ratio (SFR) based on World Bank data, QS rankings, and THE rankings, Cogent Education 11 (2024) 2317117. [CrossRef]

- C. Spence, ‘Judgement’ versus ‘metrics’ in higher education management, High Educ 77 (2019) 761–775. [CrossRef]

- A. Gunn, Metrics and methodologies for measuring teaching quality in higher education: developing the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), Educational Review 70 (2018) 129–148. [CrossRef]

- I.J. Pettersen, From Metrics to Knowledge? Quality Assessment in Higher Education, Financial Accountability & Management 31 (2015) 23–40. [CrossRef]

- J. Wilsdon, Responsible metrics, in: Higher Education Strategy and Planning, Routledge, 2017.

- P. Andras, Research: metrics, quality, and management implications, Research Evaluation 20 (2011) 90–106. [CrossRef]

- W.E. Donald, Merit beyond metrics: Redefining the value of higher education, Industry and Higher Education (2024) 09504222241264506. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, The Sod gasdynamics problem as a tool for benchmarking face flux construction in the finite volume method, Scientific African 10 (2020) e00573. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Langan, W.E. Harris, National student survey metrics: where is the room for improvement?, High Educ 78 (2019) 1075–1089. [CrossRef]

- G. Haddow, B. Hammarfelt, Quality, impact, and quantification: Indicators and metrics use by social scientists, Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 70 (2019) 16–26. [CrossRef]

- J.-A. Baird, V. Elliott, Metrics in education—control and corruption, Oxford Review of Education 44 (2018) 533–544. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, W.A.M.H.R. Jul, A.M.K.A. Jabri, H.A.M.A. Al-ghaithi, Construction of a Small-Scale Vacuum Generation System and Using It as an Educational Device to Demonstrate Features of the Vacuum, International Journal of Contemporary Education 1 (2018) 1–11. [CrossRef]

- R. Chugh, D. Turnbull, M.A. Cowling, R. Vanderburg, M.A. Vanderburg, Implementing educational technology in Higher Education Institutions: A review of technologies, stakeholder perceptions, frameworks and metrics, Educ Inf Technol 28 (2023) 16403–16429. [CrossRef]

- R. Clemons, M. Jance, Defining Quality in Higher Education and Identifying Opportunities for Improvement, Sage Open 14 (2024) 21582440241271155. [CrossRef]

- P. Chaudhary, R.K. Singh, Quality of teaching & learning in higher education: a bibliometric review & future research agenda, On the Horizon: The International Journal of Learning Futures ahead-of-print (2024). [CrossRef]

- K. Khairiah, Digitalization, Webometrics, and Its Impact on Higher Education Quality During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Esiculture (2024) 802–815. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Globalization and diversity requirement in higher education, in: WMSCI 2007 / ISAS 2007, International Institute of Informatics and Systemics (IIIS), Orlando, Florida, USA, 2007: pp. 101–106.

- A.M. Dima, R. Argatu, M. Rădoi, Performance Evaluation in Higher Education – A Comparative Approach, Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence 18 (2024) 2453–2471. [CrossRef]

- M.J.B. Ludvik, M.J.B. Ludvik, Outcomes-Based Program Review: Closing Achievement Gaps In- and Outside the Classroom With Alignment to Predictive Analytics and Performance Metrics, 2nd ed., Routledge, New York, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Herrera-Limones, J. Rey-Pérez, M. Hernández-Valencia, J. Roa-Fernández, Student Competitions as a Learning Method with a Sustainable Focus in Higher Education: The University of Seville “Aura Projects” in the “Solar Decathlon 2019,” Sustainability 12 (2020) 1634. [CrossRef]

- P.C. Wankat, Undergraduate Student Competitions, Journal of Engineering Education 94 (2005) 343–347. [CrossRef]

- M. Gadola, D. Chindamo, Experiential learning in engineering education: The role of student design competitions and a case study, International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education 47 (2019) 3–22. [CrossRef]

- G. Nabi, F. Liñán, A. Fayolle, N. Krueger, A. Walmsley, The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education in Higher Education: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda, AMLE 16 (2017) 277–299. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Zero Carbon Ready Metrics for a Single-Family Home in the Sultanate of Oman Based on EDGE Certification System for Green Buildings, Sustainability 15 (2023) 13856. [CrossRef]

- R.T. Syed, D. Singh, D. Spicer, Entrepreneurial higher education institutions: Development of the research and future directions, Higher Education Quarterly 77 (2023) 158–183. [CrossRef]

- C. Sam, P. van der Sijde, Understanding the concept of the entrepreneurial university from the perspective of higher education models, High Educ 68 (2014) 891–908. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hunter-Johnson, B. Farquharson, R. Edgecombe, J. Munnings, N. Bandelier, N. Swann, F. Butler, T. McDonald, N. Newton, L. McDiarmid, Design and Development of Virtual Teaching Practicum Models: Embracing Change During COVID 19, International Journal of Multidisciplinary Perspectives in Higher Education 8 (2023) 1–29. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Urban air mobility and flying cars: Overview, examples, prospects, drawbacks, and solutions, Open Engineering 12 (2022) 662–679. [CrossRef]

- C.N. Lippard, C.D. Vallotton, M. Fusaro, R. Chazan-Cohen, C.A. Peterson, L. Kim, G.A. Cook, Practice matters: how practicum experiences change student beliefs, Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education 45 (2024) 371–395. [CrossRef]

- B. Rivza, U. Teichler, The Changing Role of Student Mobility, High Educ Policy 20 (2007) 457–475. [CrossRef]

- T. Kim, Transnational academic mobility, internationalization and interculturality in higher education, Intercultural Education 20 (2009) 395–405. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Expectations for the Role of Hydrogen and Its Derivatives in Different Sectors through Analysis of the Four Energy Scenarios: IEA-STEPS, IEA-NZE, IRENA-PES, and IRENA-1.5°C, Energies 17 (2024) 646. [CrossRef]

- C. Holdsworth, ‘Going Away to Uni’: Mobility, Modernity, and Independence of English Higher Education students, Environ Plan A 41 (2009) 1849–1864. [CrossRef]

- U. Teichler, Internationalisation Trends in Higher Education and the Changing Role of International Student Mobility, Journal of International Mobility 5 (2017) 177–216. [CrossRef]

- H. Hottenrott, C. Lawson, What is behind multiple institutional affiliations in academia?, Science and Public Policy 49 (2022) 382–402. [CrossRef]

- H. Hottenrott, M.E. Rose, C. Lawson, The rise of multiple institutional affiliations in academia, Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 72 (2021) 1039–1058. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Compilation of Smart Cities Attributes and Quantitative Identification of Mismatch in Rankings, Journal of Engineering 2022 (2022) 1–13. [CrossRef]

- A. Bernasconi, Does the Affiliation of Universities to External Organizations Foster Diversity in Private Higher Education? Chile in Comparative Perspective, High Educ 52 (2006) 303–342. [CrossRef]

- M. Kosior-Kazberuk, W. Pawlowski, The Role of Student Initiatives in the Process of Improving the Quality of Higher Education, in: Seville, Spain, 2019: pp. 3432–3440. [CrossRef]

- A. Innab, M.M. Almotairy, N. Alqahtani, A. Nahari, R. Alghamdi, H. Moafa, D. Alshael, The impact of comprehensive licensure review on nursing students’ clinical competence, self-efficacy, and work readiness, Heliyon 10 (2024). [CrossRef]

- D.M. Salvioni, S. Franzoni, R. Cassano, Sustainability in the Higher Education System: An Opportunity to Improve Quality and Image, Sustainability 9 (2017) 914. [CrossRef]

- Žalėnienė, P. Pereira, Higher Education For Sustainability: A Global Perspective, Geography and Sustainability 2 (2021) 99–106. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, One-way and two-way couplings of CFD and structural models and application to the wake-body interaction, Applied Mathematical Modelling 35 (2011) 1036–1053. [CrossRef]

- D.T. Jefferys, S. Hodges, M.S. Trueman, A Strategy for Success on the National Council Licensure Examination for At-Risk Nursing Students in Historically Black Colleges and Universities: A Pilot Study, International Journal of Caring Sciences 10 (2017) 1705–1709.

- M. Millea, R. Wills, A. Elder, D. Molina, What Matters in College Student Success? Determinants of College Retention and Graduation Rates, Education 138 (2018) 309–322.

- M. Dagley, M. Georgiopoulos, A. Reece, C. Young, Increasing Retention and Graduation Rates Through a STEM Learning Community, Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice 18 (2016) 167–182. [CrossRef]

- M.R. Jeffreys, Tracking students through program entry, progression, graduation, and licensure: Assessing undergraduate nursing student retention and success, Nurse Education Today 27 (2007) 406–419. [CrossRef]

- S. Robertson, C.W. Canary, M. Orr, P. Herberg, D.N. Rutledge, Factors Related to Progression and Graduation Rates for RN-to-Bachelor of Science in Nursing Programs: Searching for Realistic Benchmarks, Journal of Professional Nursing 26 (2010) 99–107. [CrossRef]

- T.I. Poirier, T.M. Kerr, S.J. Phelps, Academic Progression and Retention Policies of Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 77 (2013) 25. [CrossRef]

- [Oman Authority for Academic Accreditation and Quality Assurance of Education] OAAAQA, Programme Standards Assessment Manual (PSAM) - Programme Accreditation, Version 1, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2023. https://oaaaqa.gov.om/getattachment/4359b83e-5ab9-4147-8e73-1ff0f9adcfae/Programme%20Standards%20Assessment%20Manual.aspx (accessed October 8, 2024).

- [Oman Authority for Academic Accreditation and Quality Assurance of Education] OAAAQA, Institutional Standards Assessment Manual (ISAM) - Institutional Accreditation: Stage 2, Version 1, Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2016. https://oaaaqa.gov.om/getattachment/c63fde93-150b-430d-a58f-9f68e6dc2390/Institutional%20Standards%20Assessment%20Manual.aspx (accessed October 8, 2024).

- S.A. Barbera, S.D. Berkshire, C.B. Boronat, M.H. Kennedy, Review of Undergraduate Student Retention and Graduation Since 2010: Patterns, Predictions, and Recommendations for 2020, Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice 22 (2020) 227–250. [CrossRef]

- J. Salmi, A. D’Addio, Policies for achieving inclusion in higher education, Policy Reviews in Higher Education 5 (2021) 47–72. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Ortiz-Lozano, A. Rua-Vieites, P. Bilbao-Calabuig, M. Casadesús-Fa, University student retention: Best time and data to identify undergraduate students at risk of dropout, Innovations in Education and Teaching International 57 (2020) 74–85. [CrossRef]

- C.A. Palacios, J.A. Reyes-Suárez, L.A. Bearzotti, V. Leiva, C. Marchant, Knowledge Discovery for Higher Education Student Retention Based on Data Mining: Machine Learning Algorithms and Case Study in Chile, Entropy 23 (2021) 485. [CrossRef]

- M. Tight, Student retention and engagement in higher education, Journal of Further and Higher Education 44 (2020) 689–704. [CrossRef]

- A.W. Astin, How “Good” is Your Institution’s Retention Rate?, Research in Higher Education 38 (1997) 647–658. [CrossRef]

- E. Tatem, J.L. Payne, The impact of a College of Nursing Retention Program on the graduation rates of nursing students, ABNF J 11 (2000) 59–63.

- M. Kanoğlu, Y.A. Çengel, I. DinCer, Efficiency Evaluation of Energy Systems, Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- O.A. Marzouk, Subcritical and supercritical Rankine steam cycles, under elevated temperatures up to 900°C and absolute pressures up to 400 bara, Advances in Mechanical Engineering 16 (2024) 1–18. [CrossRef]

- I. Dincer, M. Temiz, Integrated Energy Systems, in: I. Dincer, M. Temiz (Eds.), Renewable Energy Options for Power Generation and Desalination, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2024: pp. 319–361. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Performance analysis of shell-and-tube dehydrogenation module: Dehydrogenation module, Int. J. Energy Res. 41 (2017) 604–610. [CrossRef]

- F.O. Ifeanyieze, K.R. Ede, E.C. Isiwu, Effect of Career Counseling on Students’ Interest, Academic Performance and Retention Rate in Agricultural Education Programme in Universities in South East Nigeria, Interdisciplinary Journal of Educational Practice (IJEP) 10 (2023) 64–77. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Land-Use competitiveness of photovoltaic and concentrated solar power technologies near the Tropic of Cancer, Solar Energy 243 (2022) 103–119. [CrossRef]

- T. Bruckner, I.A. Bashmakov, Y. Mulugetta, H. Chum, A. De la Vega Navarro, J. Edmonds, A. Faaij, B. Fungtammasan, A. Garg, E. Hertwich, D. Honnery, D. Infield, M. Kainuma, S. Khennas, S. Kim, H.B. Nimir, K. Riahi, N. Strachan, R. Wiser, X. Zhang, Chapter 7 - Energy systems, in: Cambridge University Press, 2014. http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg3/ipcc_wg3_ar5_chapter7.pdf (accessed October 8, 2024).

- O.A. Marzouk, Tilt sensitivity for a scalable one-hectare photovoltaic power plant composed of parallel racks in Muscat, Cogent Engineering 9 (2022) 2029243. [CrossRef]

- A.E.M. van den Oever, D. Costa, G. Cardellini, M. Messagie, Systematic review on the energy conversion efficiency of biomass-based Fischer-Tropsch plants, Fuel 324 (2022) 124478. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Lookup Tables for Power Generation Performance of Photovoltaic Systems Covering 40 Geographic Locations (Wilayats) in the Sultanate of Oman, with and without Solar Tracking, and General Perspectives about Solar Irradiation, Sustainability 13 (2021) 13209. [CrossRef]

- J. Peckham, P. Stephenson, J.-Y. Hervé, R. Hutt, M. Encarnação, Increasing student retention in computer science through research programs for undergraduates, in: Proceedings of the 38th SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2007: pp. 124–128. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, A.H. Nayfeh, Characterization of the flow over a cylinder moving harmonically in the cross-flow direction, International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics 45 (2010) 821–833. [CrossRef]

- M.K. Burns, Test-retest reliability of individual student acquisition and retention rates as measured by instructional assessment, Doctor of Philosophy, School of Education, Andrews University, 1999.

- O.A. Marzouk, Characteristics of the Flow-Induced Vibration and Forces With 1- and 2-DOF Vibrations and Limiting Solid-to-Fluid Density Ratios, Journal of Vibration and Acoustics 132 (2010) 041013. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, M. Yang, Investigation of the key factors that influence high-achieving students’ enrolment and retention rate into a small honours programme and their satisfaction level towards the programme, Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education 28 (2024) 46–54. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Energy Generation Intensity (EGI) of Solar Updraft Tower (SUT) Power Plants Relative to CSP Plants and PV Power Plants Using the New Energy Simulator “Aladdin,” Energies 17 (2024) 405. [CrossRef]

- D. Singh, B. Singh, Investigating the impact of data normalization on classification performance, Applied Soft Computing 97 (2020) 105524. [CrossRef]

- D. Delen, Predicting Student Attrition with Data Mining Methods, Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice 13 (2011) 17–35. [CrossRef]

- G.G. Smith, D. Ferguson, Student attrition in mathematics e-learning, Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 21 (2005). [CrossRef]

- C. Beer, C. Lawson, The problem of student attrition in higher education: An alternative perspective, Journal of Further and Higher Education 41 (2017) 773–784. [CrossRef]

- R.C. Harris, L. Rosenberg, O.M.E. Grace, Addressing the Challenges of Nursing Student Attrition, Journal of Nursing Education 53 (2014) 31–37. [CrossRef]

- L. Grebennikov, M. Shah, Investigating attrition trendsin order to improvestudent retention, Quality Assurance in Education 20 (2012) 223–236. [CrossRef]

- S. Stewart, D.H. Lim, J. Kim, Factors Influencing College Persistence for First-Time Students, Journal of Developmental Education 38 (2015) 12–20.

- S.E. Childs, R. Finnie, F. Martinello, Postsecondary Student Persistence and Pathways: Evidence From the YITS-A in Canada, Res High Educ 58 (2017) 270–294. [CrossRef]

- J.C. Somers Patricia, Within-Year Persistence of Students at Two-Year Colleges, Community College Journal of Research and Practice 24 (2000) 785–807. [CrossRef]

- J. Su, M.L. Waugh, Online Student Persistence or Attrition: Observations Related to Expectations, Preferences, and Outcomes, Journal of Interactive Online Learning 16 (2018) 63–79.

- Newlane University, How We Calculate Progress, Rentention, and Completion Rates, (2024). https://newlane.edu/how-we-calculate-progress-rentention-and-completion-rates (accessed September 28, 2024).

- J. Burrus, D. Elliott, M. Brenneman, R. Markle, L. Carney, G. Moore, A. Betancourt, T. Jackson, S. Robbins, P. Kyllonen, R.D. Roberts, Putting and Keeping Students on Track: Toward a Comprehensive Model of College Persistence and Goal Attainment, ETS Research Report Series 2013 (2013) i–61. [CrossRef]

- S. Prakash, D.K. Saini, L. Suni, Factors influencing Progression Rate in Higher Education in Oman - Data Engineering and Statistical Approach, in: Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering 2013, IAENG [International Association of Engineers], London, UK, 2013: pp. 1–6. https://www.iaeng.org/publication/WCE2013/WCE2013_pp299-304.pdf (accessed October 15, 2024).

- [Irish Higher Education Authority] HEA, Non Progression and Completion Dashboard, (n.d.). https://hea.ie/statistics/data-for-download-and-visualisations/students/progression/non-progression-and-completion-dashboard (accessed September 27, 2024).

- [Rock Valley College - Office of Institutional Research and Effectiveness] RVC-OIRE, Persistence and Retention Rates, Rock Valley College, Rockford, Illinois, USA, 2023. https://rockvalleycollege.edu/_resources/files/institutional-research/reports/BoT-Persistence-Retention-Jan-2023.pdf (accessed October 15, 2024).

- L.N. Williams, Grit and Academic Performance of First- and Second-Year Students Majoring in Education, Doctor of Philosophy, Curriculum and Instruction with an emphasis in Higher Education Administration, University of South Florida, n.d. https://www.proquest.com/openview/bc1ff37842b340f8c4b0efc4eaa07ff1/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750 (accessed October 15, 2024).

- E.J. Gosman, B.A. Dandridge, M.T. Nettles, A.R. Thoeny, Predicting student progression: The influence of race and other student and institutional characteristics on college student performance, Res High Educ 18 (1983) 209–236. [CrossRef]

- X. Hu, X. Zhang, S. McGeown, Foreign language anxiety and achievement: A study of primary school students learning English in China, Language Teaching Research (2021). [CrossRef]

- R.C.P. Silveira, M.L.C.C. Robazzi, Impacts of work in children’s and adolescents school performance: a reality report, Injury Prevention 16 (2010) A150–A150. [CrossRef]

- K.M. Lewin, Access to education in sub-Saharan Africa: patterns, problems and possibilities, Comparative Education 45 (2009) 151–174. [CrossRef]

- I. Coxhead, N.D.T. Vuong, P. Nguyen, Getting to Grade 10 in Vietnam: does an employment boom discourage schooling?, Education Economics 31 (2023) 353–375. [CrossRef]

- J. Smith, S. Paquin, J. St-Amand, C. Singh, D. Moreau, J. Bergeron, M. Leroux, A remediation measure as an alternative to grade retention: A study on achievement motivation, Psychology in the Schools 59 (2022) 1209–1221. [CrossRef]

- [University of Sharjah] UoSh, Retention and Graduation Rates (College of Communication) │ UoSh, [University of Sharjah, Sharjah, UAE, 2023. https://www.sharjah.ac.ae/en/academics/Colleges/Communication/Documents/Retention_Graduation_Rates_2023.pdf (accessed October 16, 2024).

- [New York University Abu Dhabi] NYUAD, Facts and Figures (Retention and Graduation Rates) │ NYUAD, New York University Abu Dhabi (n.d.). https://nyuad.nyu.edu/en/about/facts-and-figures.html (accessed October 16, 2024).

- [Zayed University] ZU, Graduation & Retention Rates │ ZU, (2024). https://www.zu.ac.ae/main/en/colleges/colleges/__college_of_comm_media_sciences/accreditation/graduation-and-retention-rates (accessed October 16, 2024).

- [United States National Center for Education Statistics] NCES, College Navigator │ NCES - California Institute of Technology, (2024). https://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator/?q=california+institute&s=all&id=110404 (accessed October 8, 2024).

- O.A. Marzouk, Temperature-Dependent Functions of the Electron–Neutral Momentum Transfer Collision Cross Sections of Selected Combustion Plasma Species, Applied Sciences 13 (2023) 11282. [CrossRef]

- B. Miller, More Is Less: Extra Time Does Little to Boost College Grad Rates, Education Secto, 2010. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/publications/EDS006%20CYCT-MoreIsLess_RELEASE.pdf (accessed October 9, 2024).

- T. Bailey, J.C. Calcagno, D. Jenkins, T. Leinbach, G. Kienzl, IS STUDENT-RIGHT-TO-KNOW ALL YOU SHOULD KNOW? An Analysis of Community College Graduation Rates, Res High Educ 47 (2006) 491–519. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Estimated electric conductivities of thermal plasma for air-fuel combustion and oxy-fuel combustion with potassium or cesium seeding, Heliyon 10 (2024) e31697. [CrossRef]

- S. Boumi, A.E. Vela, Improving Graduation Rate Estimates Using Regularly Updating Multi-Level Absorbing Markov Chains, Education Sciences 10 (2020) 377. [CrossRef]

- R. Larocca, D. Carr, The Effect of Higher Education Performance Funding on Graduation Rates, Journal of Education Finance 45 (2020) 493–526.

- O.A. Marzouk, Radiant Heat Transfer in Nitrogen-Free Combustion Environments, International Journal of Nonlinear Sciences and Numerical Simulation 19 (2018) 175–188. [CrossRef]

- B.B. Gresham, M. Thompson, K. Luedtke-Hoffmann, M. Tietze, Institutional and Program Factors Predict Physical Therapist Assistant Program Graduation Rate and Licensure Examination Pass Rate, Journal of Physical Therapy Education 29 (2015) 27.

- L.E.C. Delnoij, K.J.H. Dirkx, J.P.W. Janssen, R.L. Martens, Predicting and resolving non-completion in higher (online) education – A literature review, Educational Research Review 29 (2020) 100313. [CrossRef]

- [Oman Authority for Academic Accreditation and Quality Assurance of Education] OAAAQA, Requirements for Oman’s System of Quality Assurance (ROSQA), Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2013. https://oaaaqa.gov.om/getattachment/66516266-7fe6-43bd-8fd0-8b0e38b83441/ROSQA%20-%20Requirements%20for%20Oman%60s%20System%20of%20Quality%20Assurance.aspx (accessed October 25, 2018).

- M.L. Skolnik, Higher Vocational Education in Canada: The Continuing Predominance of Two-Year Diploma Programmes, in: E. Knight, A.-M. Bathmaker, G. Moodie, K. Orr, S. Webb, L. Wheelahan (Eds.), Equity and Access to High Skills through Higher Vocational Education, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022: pp. 103–124. [CrossRef]

- M. Skolnik, The Origin and Evolution of an Anomalous Academic Credential: The Ontario College Advanced Diploma, Canadian Journal of Higher Education 53 (2023) 1–15. [CrossRef]

- J. Wood, Institutes and Colleges of Advanced Education, Australian Journal of Education 13 (1969) 257–269. [CrossRef]

- S. Nasser, Current status, challenges, and future career pathways of diploma-prepared nurses from the stakeholders’ perspective: a qualitative study, BMC Nurs 23 (2024) 542. [CrossRef]

- L.M. Blair, M.G. Finn, W. Stevenson, The Returns to the Associate Degree for Technicians, The Journal of Human Resources 16 (1981) 449–458. [CrossRef]

- S. Hussain, F.U. Zaman, S. Muhammad, A. Hafeez, Analysis of the Initiatives taken by HEC to Implement Associate Degree Program: Opportunities and Challenges, International Research Journal of Management and Social Sciences 4 (2023) 193–210.

- E. Mahaffey, The Relevance of Associate Degree Nursing Education: Past, Present, Future, Online J Issues Nurs 7 (2002). [CrossRef]

- [United States National Center for Education Statistics] NCES, Trend Generator - Graduation rate within 150% of normal time at 4-year postsecondary institutions, (2024). https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/TrendGenerator/app/answer/7/19 (accessed September 28, 2024).

- A.D. Young-Jones, T.D. Burt, S. Dixon, M.J. Hawthorne, Academic advising: does it really impact student success?, Quality Assurance in Education 21 (2013) 7–19. [CrossRef]

- V.N. Gordon, W.R. Habley, T.J. Grites, Academic Advising: A Comprehensive Handbook, John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- S. Hoidn, M. Klemenčič, eds., The Routledge International Handbook of Student-Centered Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, Routledge, London, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K.H.D. Tang, Student-centered Approach in Teaching and Learning: What Does It Really Mean?, Acta Pedagogia Asia 2 (2023) 72–83. [CrossRef]

- S.B. Merriam, G. Ntseane, Transformational Learning in Botswana: How Culture Shapes the Process, Adult Education Quarterly 58 (2008) 183–197. [CrossRef]

- S. Choy, Transformational Learning in the Workplace, Journal of Transformative Education 7 (2009) 65–84. [CrossRef]

- M.C. Clark, Transformational learning, New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 1993 (1993) 47–56. [CrossRef]

- F. Boyle, J. Kwon, C. Ross, O. Simpson, Student–student mentoring for retention and engagement in distance education, Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning 25 (2010) 115–130. [CrossRef]

- A. Gunter, G. Polidori, STEM Graduation Trends and Educational Reforms: Analyzing Factors and Enhancing Support, American Journal of STEM Education 1 (2024). https://ojed.org/STEM/article/view/7026 (accessed October 10, 2024).

- B. Tesfamariam, C. Alamo-Pastrana, E.H. Bradley, Four-Year College Completion Rates: What Accounts for the Variation?, Journal of Education 204 (2024) 527–535. [CrossRef]

- M.L. Breyfogle, K.A. Daubman, Increasing Undergraduate Student Retention with “Psychology of Success”: A Course for First-Year Students on Academic Warning, Student Success 15 (2024) 86–91. [CrossRef]

- J. Gu, X. Li, L. Wang, Undergraduate Education, in: J. Gu, X. Li, L. Wang (Eds.), Higher Education in China, Springer, Singapore, 2018: pp. 117–144. [CrossRef]

- D.P.K. Tripathi, Attitude Of Under- Graduate Students Towards Choice Based Credit System (Cbcs) In Relation To Their Academic Achievements- A Case Study., Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences (2021) 153–158. [CrossRef]

- T. Hotta, The Development of “Asian Academic Credits” as an Aligned Credit Transfer System in Asian Higher Education, Journal of Studies in International Education 24 (2020) 167–189. [CrossRef]

- T.C. Mason, R.F. Arnove, M. Sutton, Credits, curriculum, and control in higher education: Cross-national perspectives, Higher Education 42 (2001) 107–137. [CrossRef]

- K. Thomas Baby, Integrating Content-Based Instruction in a Foundation Program for Omani Nursing Students, in: R. Al-Mahrooqi, C. Denman (Eds.), English Education in Oman: Current Scenarios and Future Trajectories, Springer, Singapore, 2018: pp. 247–257. [CrossRef]

- E. Davison, R. Sanderson, T. Hobson, J. Hopkins, Skills for Success? Supporting transition into higher education for students from diverse backgrounds., Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning 24 (2022) 165–186. [CrossRef]

- R. Khalil, A Re-evaluation of Academics’ Expectations of Preparatory Year Egyptian Students: A Reconstructed Understanding, The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Educational Studies 7 (2013) 55–72. [CrossRef]

- H.B. Khoshaim, A.B. Khoshaim, T. Ali, Preparatory Year: The Filter for Mathematically Intensive Programs, International Interdisciplinary Journal of Education 7 (2018) 127–136. [CrossRef]

- [United States National Center for Education Statistics] NCES, About Us │ NCES, (2024). https://nces.ed.gov/about (accessed October 12, 2024).

- [United States National Center for Education Statistics] NCES, History │ NCES, (2024). https://nces.ed.gov/about/?sec=nceshistory (accessed October 12, 2024).

- [United States Institute of Education Sciences] IES, About Us │ IES, (2024). https://ies.ed.gov/aboutus (accessed October 12, 2024).

- C.S. Chhin, K.A. Taylor, W.S. Wei, Supporting a Culture of Replication: An Examination of Education and Special Education Research Grants Funded by the Institute of Education Sciences, Educational Researcher 47 (2018) 594–605. [CrossRef]

- [United States National Center for Education Statistics] NCES, IPEDS (Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System) - Use The Data, (2024). https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/use-the-data (accessed September 28, 2024).

- [United States National Center for Education Statistics] NCES, IPEDS (Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System) - Glossary, (2024). https://surveys.nces.ed.gov/ipeds/public/glossary (accessed September 28, 2024).

- C. Zong, A. Davis, Modeling University Retention and Graduation Rates Using IPEDS, Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice 26 (2024) 311–333. [CrossRef]

- [United States National Center for Education Statistics] NCES, IPEDS (Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System) - Trend Generator User Guide, Institute of Education Sciences (IES) at the U.S. Department of Education, Washington, DC, USA, 2018. https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/TrendGenerator/Sources/IPEDS_Trend_Generator_User_Guide.pdf (accessed September 28, 2024).

- [United States National Center for Education Statistics] NCES, College Navigator │ NCES, (2024). https://nces.ed.gov/collegenavigator (accessed September 28, 2024).

- [National Student Clearinghouse Research Center] NSC-RC, About Us │ NSC-RC, (2024). https://nscresearchcenter.org/aboutus (accessed September 28, 2024).

- [National Student Clearinghouse Research Center] NSC-RC, Publications │ NSC-RC, (2024). https://nscresearchcenter.org/publications (accessed September 28, 2024).

- [United States National Center for Education Statistics] NCES, Trend Generator - Full-time retention rate in postsecondary institutions, (2024). https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/trendgenerator/app/answer/7/32 (accessed September 28, 2024).

- [United States National Center for Education Statistics] NCES, Trend Generator - Graduation rate within 150% of normal time for bachelor’s or equivalent degree-seeking undergraduate students who received a bachelor’s or equivalent degree at 4-year postsecondary institutions, (2024). https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/trendgenerator/app/answer/7/20 (accessed October 4, 2024).

- [National Student Clearinghouse Research Center] NSC-RC, Persistence and Retention: Fall 2022 Beginning Postecondary Student Cohort, 2024. https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/PersistenceandRetention2024_Appendix.xlsx.

- S.J. Daniel, Education and the COVID-19 pandemic, Prospects 49 (2020) 91–96. [CrossRef]

- S. Pokhrel, R. Chhetri, A Literature Review on Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Teaching and Learning, Higher Education for the Future 8 (2021) 133–141. [CrossRef]

- M. Ciotti, M. Ciccozzi, A. Terrinoni, W.-C. Jiang, C.-B. Wang, S. Bernardini, The COVID-19 pandemic, Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences 57 (2020) 365–388. [CrossRef]

- C.H. Liu, S. Pinder-Amaker, H. “Chris” Hahm, J.A. Chen, Priorities for addressing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health, Journal of American College Health 70 (2022) 1356–1358. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Lederer, M.T. Hoban, S.K. Lipson, S. Zhou, D. Eisenberg, More Than Inconvenienced: The Unique Needs of U.S. College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Health Educ Behav 48 (2021) 14–19. [CrossRef]

- T. Karalis, Planning and Evaluation During Educational Disruption: Lessons Learned From COVID-19 Pandemic for Treatment of Emergencies in Education, European Journal of Education Studies (2020). [CrossRef]

- [Oman Authority for Academic Accreditation and Quality Assurance of Education] OAAAQA, Oman Academic Standards for General Foundation Programs (GFP), Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2008. https://oaaaqa.gov.om/getattachment/54ac4e6a-0d27-4dd9-b4a2-ba8759979c25/GFP%20Standards%20FINAL.aspx (accessed October 16, 2024).

- [Gulf College] GC, General Foundation Programme (GFP) │ GC, Gulf College (2024). https://gulfcollege.edu.om/programmes/general-foundation-programme/ (accessed October 16, 2024).

- R. Ravid, Practical Statistics for Educators, Rowman & Littlefield, 2024.

- O.A. Marzouk, Adiabatic Flame Temperatures for Oxy-Methane, Oxy-Hydrogen, Air-Methane, and Air-Hydrogen Stoichiometric Combustion using the NASA CEARUN Tool, GRI-Mech 3.0 Reaction Mechanism, and Cantera Python Package, Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 13 (2023) 11437–11444. [CrossRef]

- G. Casella, R. Berger, Statistical Inference, CRC Press, 2024.

- O.A. Marzouk, Direct Numerical Simulations of the Flow Past a Cylinder Moving With Sinusoidal and Nonsinusoidal Profiles, Journal of Fluids Engineering 131 (2009) 121201. [CrossRef]

- T. Elsayed, R.M. Hathout, Evaluating the prediction power and accuracy of two smart response surface experimental designs after revisiting repaglinide floating tablets, Futur J Pharm Sci 10 (2024) 34. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, A.H. Nayfeh, New Wake Models With Capability of Capturing Nonlinear Physics, in: American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, 2009: pp. 901–912. [CrossRef]

- J. Karch, Improving on Adjusted R-Squared, Collabra: Psychology 6 (2020) 45. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, A.H. Nayfeh, A Study of the Forces on an Oscillating Cylinder, in: American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, 2009: pp. 741–752. [CrossRef]

- I. Khalismatov, R. Zakirov, S. Shomurodov, R. Isanova, F. Joraev, Y. Ergashev, Correlation analysis of geological factors with the coefficient of gas transfer of organizations, E3S Web Conf. 497 (2024) 01018. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Contrasting the Cartesian and polar forms of the shedding-induced force vector in response to 12 subharmonic and superharmonic mechanical excitations, Fluid Dyn. Res. 42 (2010) 035507. [CrossRef]

- M. Fiandini, A.B.D. Nandiyanto, D.F.A. Husaeni, D.N.A. Husaeni, M. Mushiban, How to Calculate Statistics for Significant Difference Test Using SPSS: Understanding Students Comprehension on the Concept of Steam Engines as Power Plant, Indonesian Journal of Science and Technology 9 (2024) 45–108.

- P. Fryzlewicz, Robust Narrowest Significance Pursuit: Inference for Multiple Change-Points in the Median, Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 42 (2024) 1389–1402. [CrossRef]

- M. Moland, A. Michailidou, Testing Causal Inference Between Social Media News Reliance and (Dis)trust of EU Institutions with an Instrumental Variable Approach: Lessons From a Null-Hypothesis Case, Political Studies Review 22 (2024) 412–426. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Assessment of global warming in Al Buraimi, sultanate of Oman based on statistical analysis of NASA POWER data over 39 years, and testing the reliability of NASA POWER against meteorological measurements, Heliyon 7 (2021) e06625. [CrossRef]

- A. Olawale, The impact of capital market on the economic growth of Nigeria, GSC Advanced Research and Reviews 21 (2024) 013–026. [CrossRef]

- A. Salih, L. Alsalhi, A. Abou-Moghli, Entrepreneurial orientation and digital transformation as drivers of high organizational performance: Evidence from Iraqi private bank, Uncertain Supply Chain Management 12 (2024) 9–18. [CrossRef]

- Z.T. Rony, I.M.S. Wijaya, D. Nababan, J. Julyanthry, M. Silalahi, L.M. Ganiem, L. Judijanto, H. Herman, N. Saputra, Analyzing the Impact of Human Resources Competence and Work Motivation on Employee Performance: A Statistical Perspective, Journal of Statistics Applications & Probability 13 (2024) 787–793.

- H. Tannady, C.S. Dewi, Gilbert, Exploring Role of Technology Performance Expectancy, Application Effort Expectancy, Perceived Risk and Perceived Cost On Digital Behavioral Intention of GoFood Users, Jurnal Informasi Dan Teknologi (2024) 80–85. [CrossRef]

- B. Uragun, R. Rajan, Developing an Appropriate Data Normalization Method, in: 2011 10th International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications and Workshops, 2011: pp. 195–199. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, A two-step computational aeroacoustics method applied to high-speed flows, Noise Control Eng. J. 56 (2008) 396. [CrossRef]

- P. Källback, M. Shariatgorji, A. Nilsson, P.E. Andrén, Novel mass spectrometry imaging software assisting labeled normalization and quantitation of drugs and neuropeptides directly in tissue sections, Journal of Proteomics 75 (2012) 4941–4951. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Detailed and simplified plasma models in combined-cycle magnetohydrodynamic power systems, Int. j. Adv. Appl. Sci. 10 (2023) 96–108. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, X. Zhang, S. Gombault, S.J. Knapskog, Attribute Normalization in Network Intrusion Detection, in: 2009 10th International Symposium on Pervasive Systems, Algorithms, and Networks, 2009: pp. 448–453. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, A.H. Nayfeh, Loads on a Harmonically Oscillating Cylinder, in: American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, 2009: pp. 1755–1774. [CrossRef]

- L. Bornmann, L. Leydesdorff, J. Wang, Which percentile-based approach should be preferred for calculating normalized citation impact values? An empirical comparison of five approaches including a newly developed citation-rank approach (P100), Journal of Informetrics 7 (2013) 933–944. [CrossRef]

- O.A. Marzouk, Flow control using bifrequency motion, Theor. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 25 (2011) 381–405. [CrossRef]

- D.P. Bills, R.L. Canosa, Sharing introductory programming curriculum across disciplines, in: Proceedings of the 8th ACM SIGITE Conference on Information Technology Education, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2007: pp. 99–106. [CrossRef]

- N.M. Ide, J.C. Hill, Interdisciplinary Majors Involving Computer Science, Computer Science Education 2 (1991) 139–153. [CrossRef]

- E. Anthony, Computing education in academia: toward differentiating the disciplines, in: Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Information Technology Curriculum, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2003: pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- F.-M.E. Uzoka, R. Connolly, M. Schroeder, N. Khemka, J. Miller, Computing is not a rock band: student understanding of the computing disciplines, in: Proceedings of the 14th Annual ACM SIGITE Conference on Information Technology Education, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2013: pp. 115–120. [CrossRef]

- K.R. Demarest, J.R. Miller, J.A. Roberts, C. Tsatsoulis, Electrical engineering vs. computer engineering vs. computer science: developing three distinct but interrelated curricula, in: Proceedings Frontiers in Education 1995 25th Annual Conference. Engineering Education for the 21st Century, 1995: p. 4b2.1-4b2.5 vol.2. [CrossRef]

- J. Courte, C. Bishop-Clark, Do students differentiate between computing disciplines?, SIGCSE Bull. 41 (2009) 29–33. [CrossRef]

- [Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology] ABET, Program Eligibility Requirements │ ABET, ABET (2024). https://www.abet.org/accreditation/what-is-accreditation/eligibility-requirements (accessed October 15, 2024).

- [Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology] ABET, Bylaws, Constitution and Rules of Procedure │ ABET, ABET (2024). https://www.abet.org/about-abet/governance/bylaws-constitution-and-rules-of-procedure (accessed October 15, 2024).

- [Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology] ABET, ABET Constitution, 2015. https://www.abet.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Ratified-ABET-Constitution-2015-Public.pdf (accessed October 15, 2024).

- R. Gouia-Zarrad, R. Gharbi, A. Amdouni, Lessons Learned from a Successful First Time ABET Accreditation of Three Engineering Programs, in: 2024 IEEE World Engineering Education Conference (EDUNINE), 2024: pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- N. Juneam, R. Greenlaw, Spawning Four-Year, ABET-Accreditable Programs in Cybersecurity from Existing Computer Science Programs in Thailand, International Journal of Computing Sciences Research 8 (2024) 2612–2634.

- J. DeBello, P. Ghazizadeh, F. Keshtkar, Special Topics Courses in ABET Accredited Computer Science Degree Curriculum: Benefits and Challenges, in: Valencia, Spain, 2024: pp. 7535–7535. [CrossRef]

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).