Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

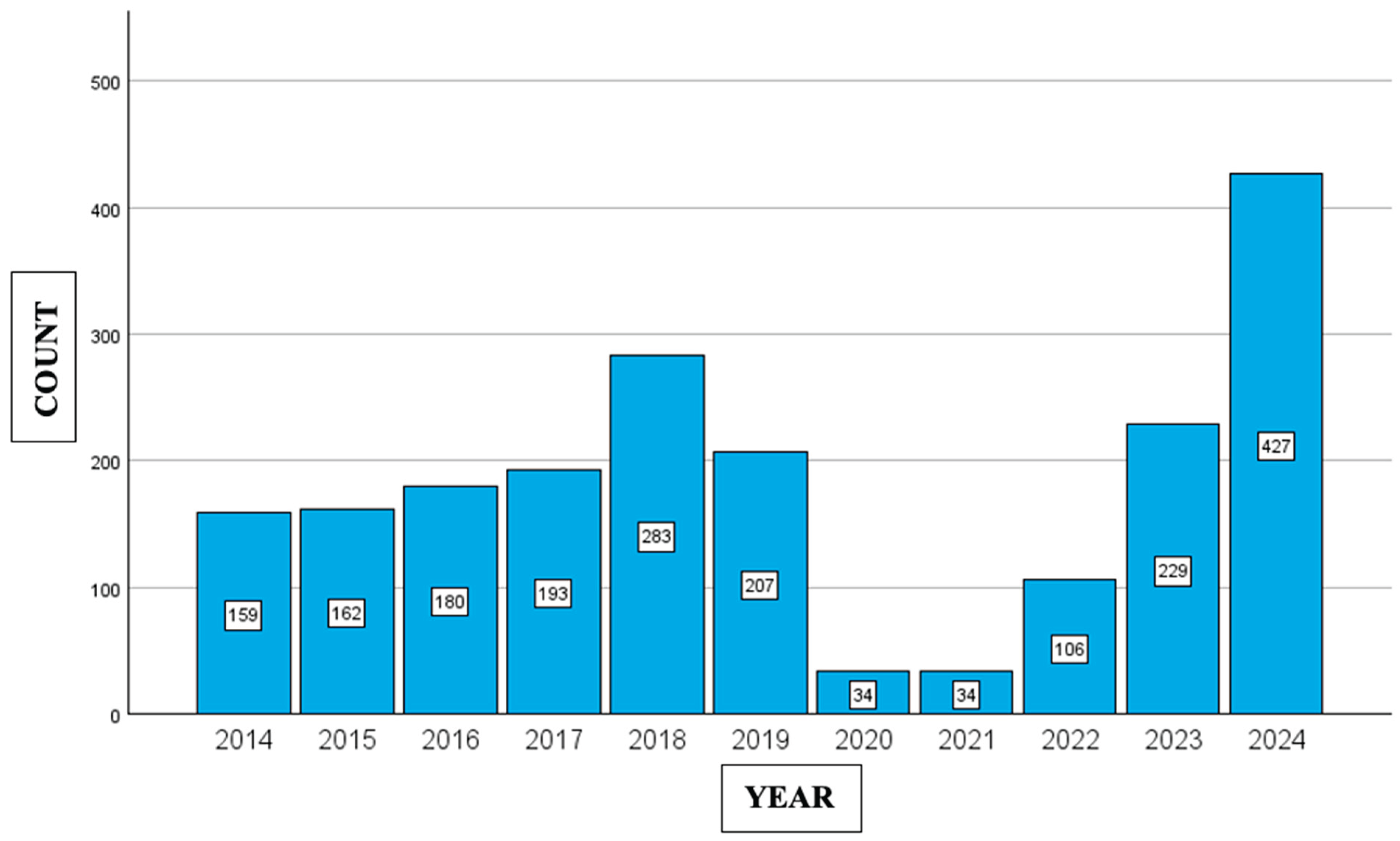

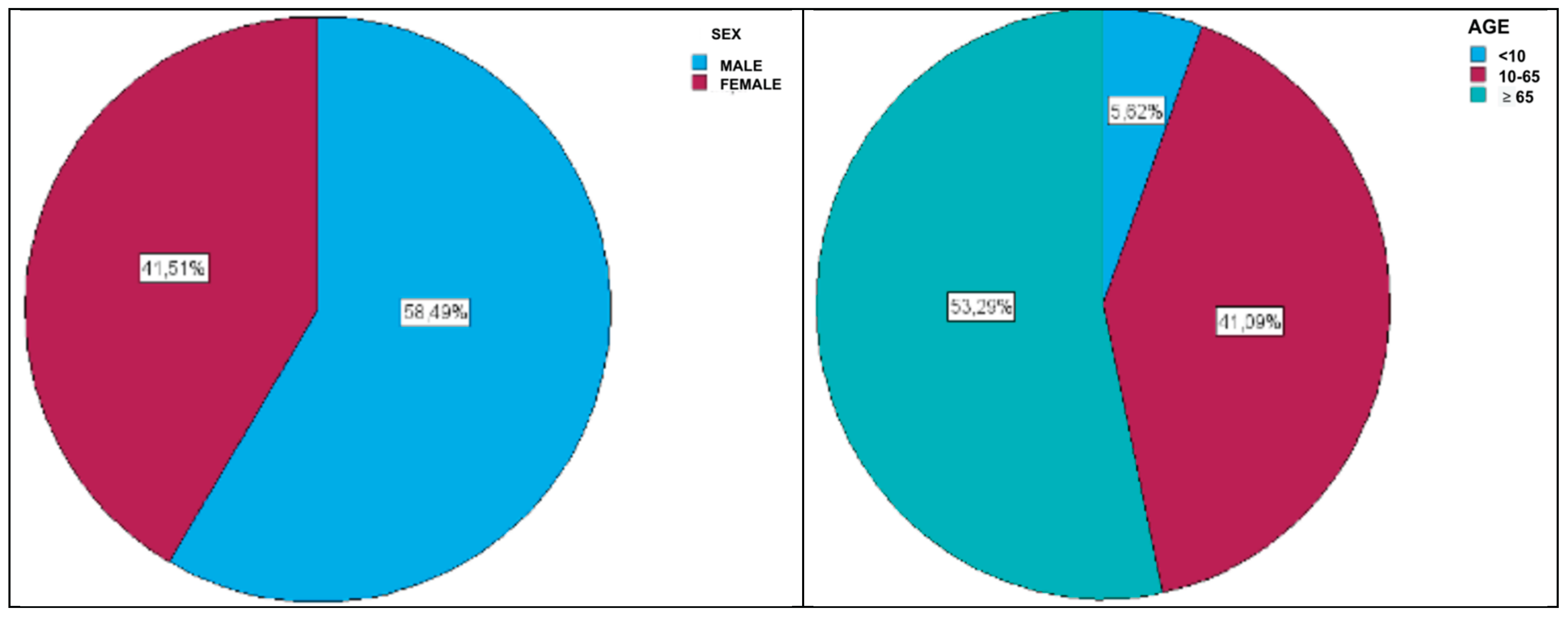

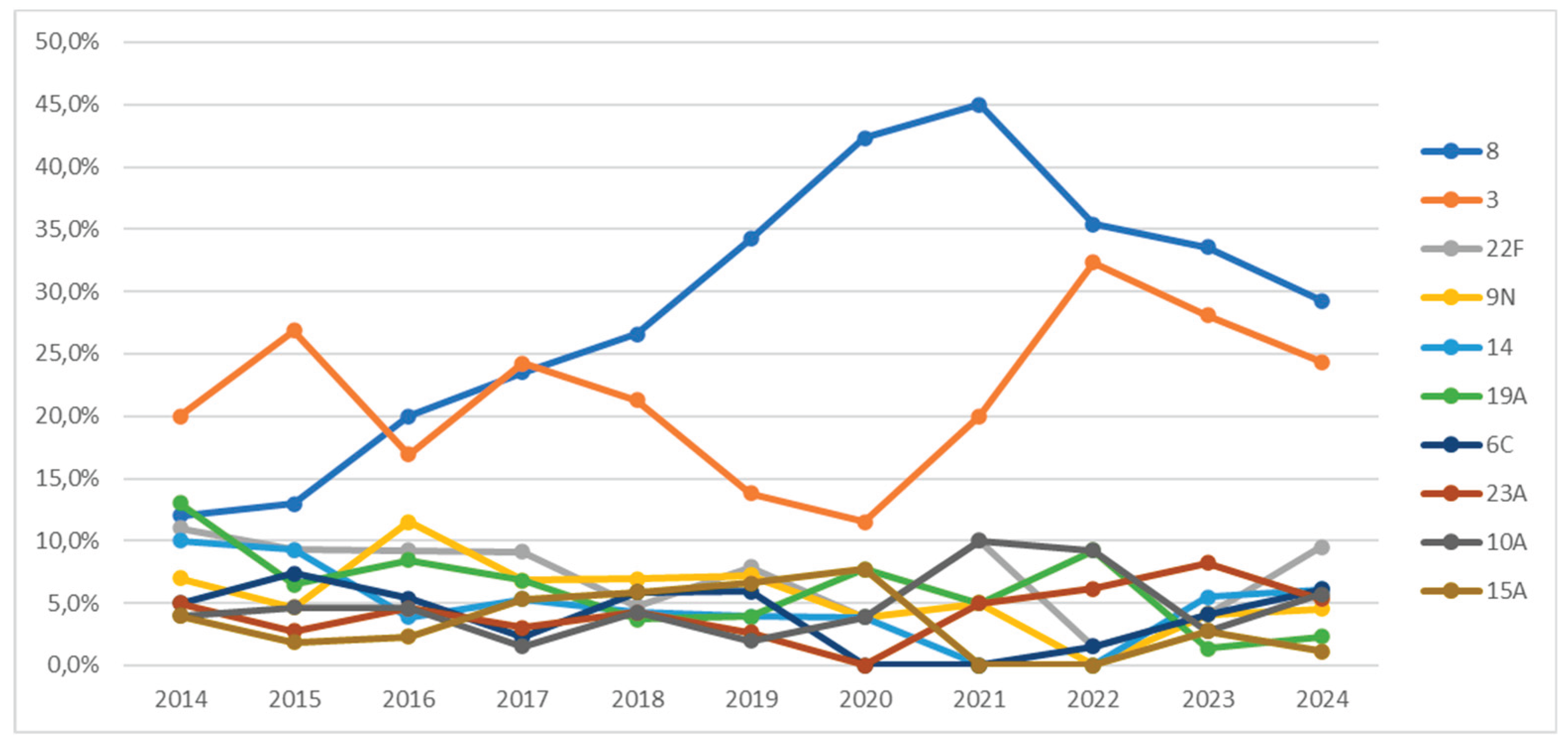

Background/Objectives: This study analyzes the epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) and the dynamics of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes in the Comunidad Valenciana (CV), Spain, over a 10-year period (2014–2024), with particular focus on vaccine coverage and effectiveness of PCV13 compared to the newer PCV20 and PCV21 formulations. Methods: A total of 2,014 isolates were collected from sterile clinical samples and characterized by serotype, patient demographics, and vaccination status. Results: Overall vaccination coverage was low (22.6%), with the highest rates observed in children under 10 years (78%) compared to only 16% in those aged 10–64 years and 22% in those over 64. Serotype distribution revealed 120 distinct serotypes, with serotype 8 (17.6%) and serotype 3 (14.7%) being the most frequent. Serotype 8 predominated among unvaccinated individuals, while serotype 3 remained highly prevalent despite inclusion in PCV13, reflecting limited vaccine effectiveness. Other relevant serotypes included 22F, 9N, 19A, 6C, and 23A. Temporal analysis showed increases in serotypes 8, 3, and 23A in recent years, while 9N, 19A, 15A, and 11A significantly declined. Among serotypes with <2% incidence, some such as 4, 12F, 16F, and 24F showed upward trends. Conclusions: The findings suggest that PCV20 currently provides broad coverage of dominant serotypes, but PCV21 may offer advantages should serotypes like 23A, 9N, or 15A increase further due to serotype replacement. Continuous epidemiological surveillance is essential to guide evidence-based vaccine policy and anticipate future vaccine reformulations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

2.2. Sociodemographic and Clinical Data

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- 0.00–0.09: negligible

- 0.10–0.29: small

- 0.30–0.49: medium

- ≥0.50: large

3. Results

3.1. Vaccination Status Overview

| Age | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | <10 | 10-64 | >64 | ||||||

| Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | ||

| Total | 1993 | 100.0% | 112 | 100.0% | 819 | 100.0% | 1062 | 100.0% | |

| Not vaccinated/Unknown status | 1542 | 77.4% | 25 | 22.3% | 689 | 84.1% | 828 | 78.0% | |

| Vaccinated with PPV23 | 226 | 11.3% | 3 | 2.7% | 45 | 5.5% | 178 | 16.8% | |

| Vaccinated with PCV13 | 125 | 6.2% | 53 | 47.4% | 51 | 6.3% | 21 | 2.0% | |

| Vaccinated, but vaccine type unknown | 73 | 3.7% | 30 | 27% | 26 | 3.2% | 17 | 1.5% | |

| Vaccinated with both PCV13 and PPV23 | 27 | 1.4% | 1 | 0.9% | 8 | 1.0% | 18 | 1.7% | |

3.2. Pneumococcal Serotypes

- Serotype 8 was more common in individuals over 10 years of age, particularly those aged 10–64 years.

- Serotype 3 was more frequent in individuals over 64 years than in those aged 10–64 years.

- Serotypes 10A and 23B were more frequent in children under 10 years of age (small effect size, Cramer’s V = 0.186).

3.3. Serotypes and Vaccination

| Vaccination status | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Not vaccinated/Unknown | Vaccinated PCV13 | Vaccinated PPV23 | Vaccinated with PCV13 and PPV23 | Vaccinated, but vaccine type unknown | ||||||||

| Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | ||

| Serotypes (>2% incidence) | Total | 2014 | 100.0% | 1563 | 100.0% | 125 | 100.0% | 226 | 100.0% | 27 | 100.0% | 73 | 100.0% |

| Others | 669 | 33.2% | 472 | 30.2% | 61 | 48.8% | 87 | 38.5% | 14 | 51.9% | 35 | 47.9% | |

| 8 | 354 | 17.6% | 308 | 19.7% | 11 | 8.8% | 23 | 10.2% | 5 | 18.5% | 7 | 9.6% | |

| 3 | 297 | 14.7% | 243 | 15.5% | 12 | 9.6% | 32 | 14.2% | 3 | 11.1% | 7 | 9.6% | |

| 22F | 101 | 5.0% | 86 | 5.5% | 5 | 4.0% | 8 | 3.5% | 2 | 7.4% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 9N | 80 | 4.0% | 71 | 4.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 8 | 3.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.4% | |

| 14 | 71 | 3.5% | 60 | 3.8% | 3 | 2.4% | 7 | 3.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.4% | |

| 19A | 70 | 3.5% | 54 | 3.5% | 5 | 4.0% | 6 | 2.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 6.8% | |

| 6C | 66 | 3.3% | 51 | 3.3% | 2 | 1.6% | 13 | 5.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| 23A | 61 | 3.0% | 46 | 2.9% | 1 | 0.8% | 9 | 4.0% | 1 | 3.7% | 4 | 5.5% | |

| 10A | 56 | 2.8% | 35 | 2.2% | 12 | 9.6% | 5 | 2.2% | 1 | 3.7% | 3 | 4.1% | |

| 15A | 46 | 2.3% | 29 | 1.9% | 6 | 4.8% | 6 | 2.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 6.8% | |

| 31 | 45 | 2.2% | 36 | 2.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 3.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 2.7% | |

| 11A | 43 | 2.1% | 28 | 1.8% | 4 | 3.2% | 9 | 4.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 2.7% | |

| 23B | 40 | 2.0% | 31 | 2.0% | 3 | 2.4% | 5 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.4% | |

| Invalidated | 15 | 0.7% | 13 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.4% | 1 | 3.7% | 0 | 0.0% | |

3.4. Serotype Trends Over Time

| Year | |||||||||

| Total | 2014-2019 | 2020-2022 | 2023-2024 | ||||||

| Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | ||

| Serotype | Total | 1330 | 100.0% | 810 | 100.0% | 111 | 100.0% | 409 | 100.0% |

| 8 | 354 | 26.6% | 185 | 22.8% | 43 | 38.7% | 126 | 30.8% | |

| 3 | 297 | 22.3% | 164 | 20.2% | 28 | 25.2% | 105 | 25.7% | |

| 22F | 101 | 7.6% | 66 | 8.1% | 4 | 3.6% | 31 | 7.6% | |

| 9N | 80 | 6.0% | 60 | 7.4% | 2 | 1.8% | 18 | 4.4% | |

| 14 | 71 | 5.3% | 46 | 5.7% | 1 | 0.9% | 24 | 5.9% | |

| 19A | 70 | 5.3% | 53 | 6.5% | 9 | 8.1% | 8 | 2.0% | |

| 6C | 66 | 5.0% | 43 | 5.3% | 1 | 0.9% | 22 | 5.4% | |

| 23A | 61 | 4.6% | 30 | 3.7% | 5 | 4.5% | 26 | 6.4% | |

| 10A | 56 | 4.2% | 28 | 3.5% | 9 | 8.1% | 19 | 4.6% | |

| 15A | 46 | 3.5% | 37 | 4.6% | 2 | 1.8% | 7 | 1.7% | |

| 31 | 45 | 3.4% | 32 | 4.0% | 3 | 2.7% | 10 | 2.4% | |

| 11A | 43 | 3.2% | 37 | 4.6% | 2 | 1.8% | 4 | 1.0% | |

| 23B | 40 | 3.0% | 29 | 3.6% | 2 | 1.8% | 9 | 2.2% | |

| Year | |||||||

| Total | 2014-2021 | 2022-2024 | |||||

| Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | ||

| Serotype | Total | 1330 | 100.0% | 856 | 100.0% | 474 | 100.0% |

| 8 | 354 | 26.6% | 205 | 23.9% | 149 | 31.4% | |

| 3 | 297 | 22.3% | 171 | 20.0% | 126 | 26.6% | |

| 22F | 101 | 7.6% | 69 | 8.1% | 32 | 6.8% | |

| 9N | 80 | 6.0% | 62 | 7.2% | 18 | 3.8% | |

| 14 | 71 | 5.3% | 47 | 5.5% | 24 | 5.1% | |

| 19A | 70 | 5.3% | 56 | 6.5% | 14 | 3.0% | |

| 6C | 66 | 5.0% | 43 | 5.0% | 23 | 4.9% | |

| 23A | 61 | 4.6% | 31 | 3.6% | 30 | 6.3% | |

| 10A | 56 | 4.2% | 31 | 3.6% | 25 | 5.3% | |

| 15A | 46 | 3.5% | 39 | 4.6% | 7 | 1.5% | |

| 31 | 45 | 3.4% | 33 | 3.9% | 12 | 2.5% | |

| 11A | 43 | 3.2% | 39 | 4.6% | 4 | 0.8% | |

| 23B | 40 | 3.0% | 30 | 3.5% | 10 | 2.1% | |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- PCV20 covers the main circulating serotypes currently, including 8, 3, 22F, 14, 19A, 11A, and 10A.

- PCV21 could be superior if serotypes such as 9N, 23A/B, 15A, and 31 increase in incidence as a consequence of serotype replacement following the introduction of PCV20. This study provides preliminary data that must be confirmed with further follow-up. At present, the rise in serotypes not included in PCV20 appears residual. It remains to be seen what collateral impact PCV20 inclusion in vaccination programs may have.

- Future research should assess immune responses to PCV20, especially against serotype 3, one of the most lethal and evasive serotypes not well controlled by PCV13.

- It is essential to select vaccines based on local epidemiological data.

- This study underscores the importance of ongoing epidemiological surveillance of IPD to evaluate the evolution of vaccine and non-vaccine serotypes, analyze vaccine effectiveness, and guide future evidence-based vaccine reformulation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Pneumococcus. In: Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Surveillance Standards. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Disponible en: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/immunization/vpd_surveillance/vpd surveillance-standards-publication/who-surveillancevaccinepreventable-17 pneumococcus-r2.pdf.

- Drijkoningen JJ, Rohde GG. Pneumococcal infection in adults: burden of disease. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(Suppl 5):45–51. [CrossRef]

- Musher DM, Anderson R, Feldman C. The remarkable history of pneumococcal vaccination: an ongoing challenge. Pneumonia (Nathan). 2022;14(1):5. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Pneumococcal disease: vaccine standardization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/teams/health-product-policy-and-standards/standards-and-specifications/norms-and-standards/vaccine-standardization/pneumococcal-disease.

- Scelfo C, Menzella F, Fontana M, Ghidoni G, Galeone C, Facciolongo NC. Pneumonia and Invasive Pneumococcal Diseases: The Role of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in the Era of Multi-Drug Resistance. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(5):420. [CrossRef]

- Davies LRL, Cizmeci D, Guo W, Luedemann C, Alexander-Parrish R, Grant L, et al. Polysaccharide and conjugate vaccines to Streptococcus pneumoniae generate distinct humoral responses. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14(656):eabm4065. [CrossRef]

- Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, Harrison LH, Bennett NM, Lynfield R, Reingold A, Cieslak PR, Pilishvili T, Jackson D, et al. Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein–polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2003;348 (18):1737–1746. [CrossRef]

- Platt HL, Cardona JF, Haranaka M, Sugayama SM, Rausch D, Greenberg D, et al. A phase 3 trial of a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41(5):345–52. [CrossRef]

- Essink B, Sabharwal C, Cannon K, Frenck RW, Lal H, Xu X, et al. Pivotal Phase 3 randomized clinical trial of the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults aged ≥18 years. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(3):390–8. [CrossRef]

- Jansen KU, Anderson AS, Scully IL, Tanimura D, Gruber WC. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of V116, a 21-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, in adults aged ≥50 years: a randomized, double-blind, phase 1/2 trial. Vaccine. 2022;40(43):6223–30. [CrossRef]

- Pfizer Inc. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. PREVNAR 20 (Pneumococcal 20-valent Conjugate Vaccine). Prescribing Information [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Disponible en: https://www.fda.gov/media/150386/download.

- Merck & Co., Inc. CAPVAXIVE™ (Pneumococcal 21-valent Conjugate Vaccine): FDA Approval Press Release [Internet]. 2023 Nov 28 [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Disponible en: https://www.merck.com/news/u-s-fda-approves-capvaxive-pneumococcal-21-valent-conjugate-vaccine-for-adults/.

- European Medicines Agency. Prevenar 20 (pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine—20 valent). EMA/80599/2024 [Internet]. Amsterdam: EMA; 2022 Feb 14 [citado 2025 Jun 8]. Disposable in: EMA pfizer.com+15.

- Generalitat Valenciana. El Consell adquiere 500.000 dosis de vacuna frente al neumococo para reforzar la protección infantil y de personas adultas. Comunica GVA [Internet]. 2024 Jul 28 [citado 2025 Jun 8]. Disponible en: https://comunica.gva.es/es/detalle?id=384988364&site=373422400.

- Comité Asesor de Vacunas de la AEP. Calendario de vacunaciones de la Comunidad Valenciana. Vacunas AEP [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 8]. Disponible en: https://vacunasaep.org/profesionales/calendario-vacunas/comunidad-valenciana.

- Muñoz,Isabel- Vanaclocha,Hermelinda- Martín-Sierra,Miguel y González,Francisco. Red de Vigilancia Microbiológica de la Comunidad Valenciana (RedMIVA). Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica. 2008; 26(2): 77-81.

- Diehl, J. M. / Kohr, H.U. (1999). Deskriptive Statistik. («Estadística descriptiva») 12ª edición. Klotz Eschborn, p.161.

- Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM, et al. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis 2010; 201:32–41. 15.

- Wiese AD, Griffin MR, Grijalva CG. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines on hospitalizations for pneumonia in the United States. Expert Rev Vaccines 2019; 18:327–41.

- ECDC. Invasive Pneumococcal Disease—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/invasive-pneumococcal-disease-annual-epidemiological-report-2018 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Conselleria de Sanitat. Orden 3 Abr 2015, de inclusión de la vacuna frente al neumococo en los niños nacidos a partir del 1 de enero 2015. Diari Oficial de la Generalitat Valenciana [Internet]. 13 Abr 2015 [citado 2025 Jun 12]. Disponible en: https://dogv.gva.es/datos/2015/04/13/pdf/2015_3241.pd.

- Perniciaro S, van der Linden M. Pneumococcal vaccine uptake and vaccine effectiveness in older adults with invasive pneumococcal disease in Germany: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021 Jun 3;7:100126. [CrossRef]

- Suaya, J.A.; Mendes, R.E.; Sings, H.L.; Arguedas, A.; Reinert, R.-R.; Jodar, L.; Isturiz, R.E.; Gessner, B.D. Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype distribution and antimicrobial nonsusceptibility trends among adults with pneumonia in the United States, 2009–2017. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 557–566.

- Diab-Casares L, Tormo-Palop N, Hernández-Felices FJ, Artal-Muñoz V, Floría-Baquero P, Martin-Rodríguez JL, Medina-González R, Cortés-Badenes S, Fuster-Escrivá B, Gil-Bruixola A, et al. Predominant pneumococcal serotypes in isolates causing invasive disease in a Spanish region: an examination of their association with clinical factors, antimicrobial resistance, and vaccination coverage. J Clin Med. 2025;14(5):1612. [CrossRef]

- Ciruela P, Broner S, Izquierdo C, Pallarés R, Muñoz-Almagro C, Hernández S, et al.; Catalan Working Group on Invasive Pneumococcal Disease. Indirect effects of paediatric conjugate vaccines on invasive pneumococcal disease in older adults [Erratum in: Int J Infect Dis.

- Domínguez Á, Ciruela P, Hernández S, García-García JJ, Soldevila N, Izquierdo C, Moraga-Llop F, Díaz A, de Sevilla MF, González-Peris S, Campins M, Uriona S, Martínez-Osorio J. Effectiveness of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in preventing invasive pneumococcal disease in children aged 7–59 months: a matched case-control study. PLoS One. 2017 Aug 14;12(8):e0183191. [CrossRef]

- Essink B, Sabharwal C, Cannon K, Pérez JL, Peng Y, Rupp R, et al. Pivotal phase 3 randomized clinical trial of the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults aged ≥18 years. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(3):390–8. [CrossRef]

- Platt HL, Bruno C, Buntinx E, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an adult pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, V116 (PCV21), in healthy adults: phase 1/2, randomised, double-blind, active comparator-controlled, multicentre, US-based trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24(11):1141–50. [CrossRef]

- Løchen A, Croucher NJ, Anderson RM. Divergent serotype replacement trends and increasing diversity in pneumococcal disease in high income settings reduce the benefit of expanding vaccine valency. Sci Rep. 2020 Nov 4;10(1):18977. [CrossRef]

- Red Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica (RENAVE). Situación de la enfermedad neumocócica invasiva en España. Año 2023. Boletín Epidemiológico Semanal [Internet]. 2024;32(2):17–31 [cited 2025 Jun 12]. Disponible en: https://revista.isciii.es/index.php/bes/article/view/1381/1685.

- Paavilainen H, Rantala S, Lyytikäinen O, et al. Second reported outbreak of pneumococcal pneumonia among shipyard employees in Turku, Finland, Aug–Oct 2023: a case–control study. Epidemiol Infect. 2025;153:e32. [CrossRef]

| Age | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | <10 | 10-64 | >64 | ||||||

| Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | ||

| Serotype | Total | 1319 | 100.0% | 60 | 100.0% | 532 | 100.0% | 727 | 100.0% |

| 8 | 353 | 26.8% | 5 | 8.3% | 188 | 35.3% | 160 | 22.0% | |

| 3 | 293 | 22.2% | 15 | 25.0% | 99 | 18.6% | 179 | 24.6% | |

| 22F | 99 | 7.5% | 5 | 8.3% | 40 | 7.5% | 54 | 7.4% | |

| 9N | 79 | 6.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 35 | 6.6% | 44 | 6.1% | |

| 14 | 71 | 5.4% | 5 | 8.3% | 21 | 3.9% | 45 | 6.2% | |

| 19A | 70 | 5.3% | 5 | 8.3% | 22 | 4.1% | 43 | 5.9% | |

| 6C | 64 | 4.9% | 1 | 1.7% | 21 | 3.9% | 42 | 5.8% | |

| 23A | 61 | 4.6% | 3 | 5.0% | 19 | 3.6% | 39 | 5.4% | |

| 10A | 56 | 4.2% | 10 | 16.7% | 24 | 4.5% | 22 | 3.0% | |

| 15A | 46 | 3.5% | 3 | 5.0% | 18 | 3.4% | 25 | 3.4% | |

| 31 | 44 | 3.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 15 | 2.8% | 29 | 4.0% | |

| 11A | 43 | 3.3% | 2 | 3.3% | 13 | 2.4% | 28 | 3.9% | |

| 23B | 40 | 3.0% | 6 | 10.0% | 17 | 3.2% | 17 | 2.3% | |

| Year | |||||||

| Total | 2014-2021 | 2022-2024 | |||||

| Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | ||

| Serotype | Total | 2014 | 100.0% | 1252 | 100.0% | 762 | 100.0% |

| 4 | 29 | 1.4% | 12 | 1.0% | 17 | 2.2% | |

| 38 | 23 | 1.1% | 9 | 0.7% | 14 | 1.8% | |

| 12F | 22 | 1.1% | 5 | 0.4% | 17 | 2.2% | |

| 16F | 16 | 0.8% | 3 | 0.2% | 13 | 1.7% | |

| 24 | 11 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.1% | 10 | 1.3% | |

| 17F | 11 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.1% | 10 | 1.3% | |

| 15B/C | 10 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.1% | 9 | 1.2% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).