1. Introduction

Pneumococcus is an important pathogen for its high morbidity and mortality, especially in patients of extreme ages or with underlying diseases that compromise their immunity. This can lead to invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) [

1,

2]. IPD is defined as any isolation

of S. pneumoniae in sterile fluids, such as blood, cerebrospinal fluid, synovial fluid, pleural exudate, or pericardial fluid. The risk of developing IPD in a previously colonized patient is related to the serotype [

2].

Polysaccharide and conjugate vaccines have been developed based on the most prevalent capsular serotypes in IPD, demonstrating high efficacy in preventing and reducing infection. The introduction of these vaccines has modified the epidemiology of the bacterial population, making continuous surveillance studies necessary [

3]. The pneumococcal serotypes causing invasive disease vary between geographical areas, and their distribution depends on the period studied [

4]. This is important as current vaccines are based on a selected number of serotypes.

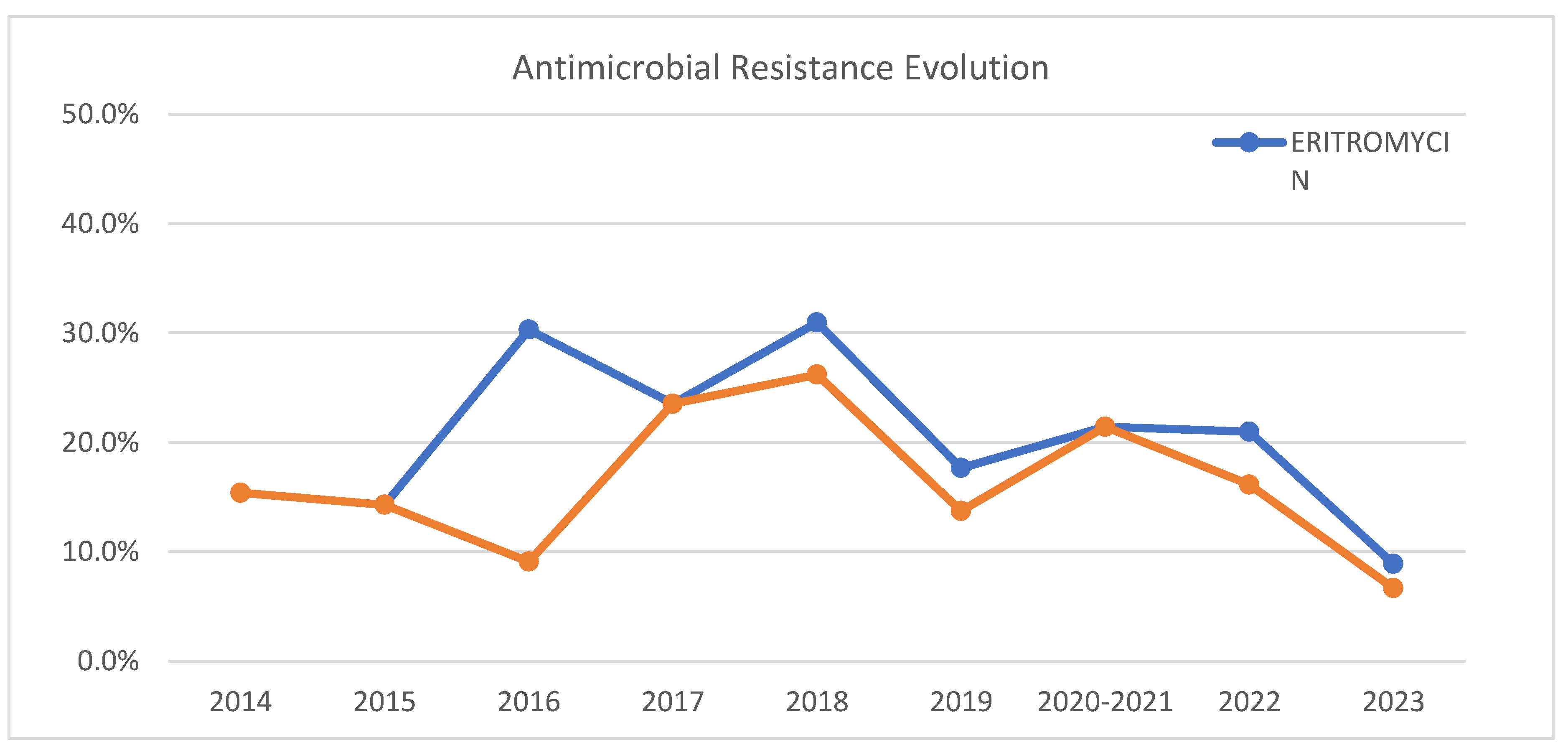

Another aspect that highlights the importance of studying this microorganism is the relationship between serotype and antimicrobial resistance. Certain serotypes show a higher frequency of resistance to penicillin and/or other antibiotics, underscoring the need for resistance surveillance. For many years, penicillin has been the treatment of choice for

S. pneumoniae due to its great bactericidal activity and low minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs). However, the prevalence of penicillin-resistant strains has increased worldwide, with Spain being one of the countries with the highest percentage of resistance, for example, in a study of pneumococcal disease in the Community of Madrid between 2007 and 2022, the percentage of penicillin resistance was 32.3% [

5]. Approximately 6% of isolates show resistance to cephalosporins in Europe [

6]. With respect to macrolides, the frequency of resistant strains in Spain has increased over the last two decades, reaching 33.2%-46.8% in non-invasive strains and 20-30% in invasive strains [

7,

8], mainly due to high consumption. Quinolones, despite being among the treatments of choice for non-severe pneumonia in adults, maintain very low resistance rates, around 3% of isolates in our geographical area [

9], probably because their use is not recommended in children, who are the major reservoir of pneumococcus. It is noteworthy that there is a lack of recent studies on pneumococcal antimicrobial susceptibility in our area.

The objective of this study has been to establish the epidemiology of the distribution of different Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes causing IPD and their prevalence in the Region of Comunidad Valenciana (CV). Additionally, the relationship among serotypes and clinical factors of the patients has been analyzed, differentiating between those with 0 or 1 comorbidity and those with more than 1. The study also examined serotypes that were more or less frequently associated with resistances. Moreover, next-generation sequencing of a representative group of pneumococcal isolates was performed to analyze clonal relationships.

2. Material and Methods

This is a retrospective longitudinal study analyzing 1587 isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae causing IPD from various hospitals in the CV during the years 2014-2023.

2.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Factors Associated with Patients

All the cases data come from IPD records reported to an epidemiological surveillance system (called AVE) from three sources: outpatient information systems, hospital preventive medicine services, and the RedMIVA network [

10], which incorporates real-time microbiological test results from hospitals in the CV into the AVE system. The following information was collected and analyzed: age, sex, serotype, infection focus, comorbidities, vaccine coverage, antimicrobial resistance and evolution.

2.2. Serotyping and Study of Antimicrobial Sensitivity

Although each laboratory linked to RedMIVA decides the bacteriological procedure to use for detecting the microorganism, the methods used are generally subjected to the same interpretation standards.

The serotyping of each pneumococcal isolate was performed using the Neufeld capsule test at the Microbiology Service of Hospital La Fe in Valencia or the National Microbiology Center from 2014 to 2021. From 2022 onwards, it was performed using PCR followed by reverse hybridization (S.PneumoStrip, Operon, Immuno & Molecular Diagnostics) by the current reference center for pneumococcal serotyping in the CV, the Consorcio Hospital General Universitario de Valencia.

Information on susceptibility to the following antimicrobials was obtained: penicillin, ceftriaxone, vancomycin, linezolid, levofloxacin, erythromycin, and clindamycin. Susceptibility determination followed the values established by the International Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST).

2.3. Whole Genome Sequencing Applied to Clinical Microbiology

Whole genome sequencing was performed on 104 representative pneumococcal isolates. DNA from all strains was purified using the MagCoreR Automated Extraction System DNA extraction kit (RBC Bioscience, New Taipei City, Taipei). DNA libraries were prepared using Nextera XT and sequenced using the NextSeq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, California, United States).

2.4. Bioinformatics Analysis: MLST, Serotype, and Antimicrobial Resistance

INNUca was used for quality assessment of reads, and

de novo assembly was performed with SPAdes. The obtained genome sequences were uploaded to Pathogenwatch (

https://pathogen.watch/) in FASTA format. This platform was used to obtain the MLST.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages are shown. Differences in parameters between groups were evaluated with Pearson's non-parametric Chi2 test, and only in the case of 2x2 tables, Fisher's exact test was applied. All multiple comparisons were adjusted using Bonferroni correction. All contrasts were accompanied by the effect size estimator to complete the interpretation of the results. For categorical variables, it was Cramer's V. The criteria for the classification of the magnitude of the effect was as follows:

Cramer's V1: 0.00-0.09 as negligible, 0.10-0.29 as low, 0.30-0.49 as medium, and 0.50 and above as high. The significance level used in the analyses was 5% (α=0.05)2.

1Diehl, J. M. / Kohr, H.U. (1999). Descriptive Statistics. 12th edition. Klotz Eschborn, p. 161. 2The p-value is, assuming there are no differences between groups, the probability that the obtained results could be due to chance. The smaller the p-value, the lower the probability that the obtained results are due to chance, and the greater the evidence against the null hypothesis (absence of differences). Any p-value less than 0.05 is indicative of a statistically significant relationship. Conversely, a p-value greater than or equal to 0.05 indicates the absence of a relationship.

4. Discussion

In this study, the incidence of IPD by gender followed the trend observed in previous studies [

11], being more frequent in males (60%) compared to females (40%). Additionally, age was found to be a significant risk factor for the development of this disease, with a mean patient age of 60 years, similar to what has been reported in other studies [

12], where more than 50% of cases occurred in individuals aged 65 years or older [

13]. The correlation between age and the serotype of the disease had also been documented in previous research [

14].

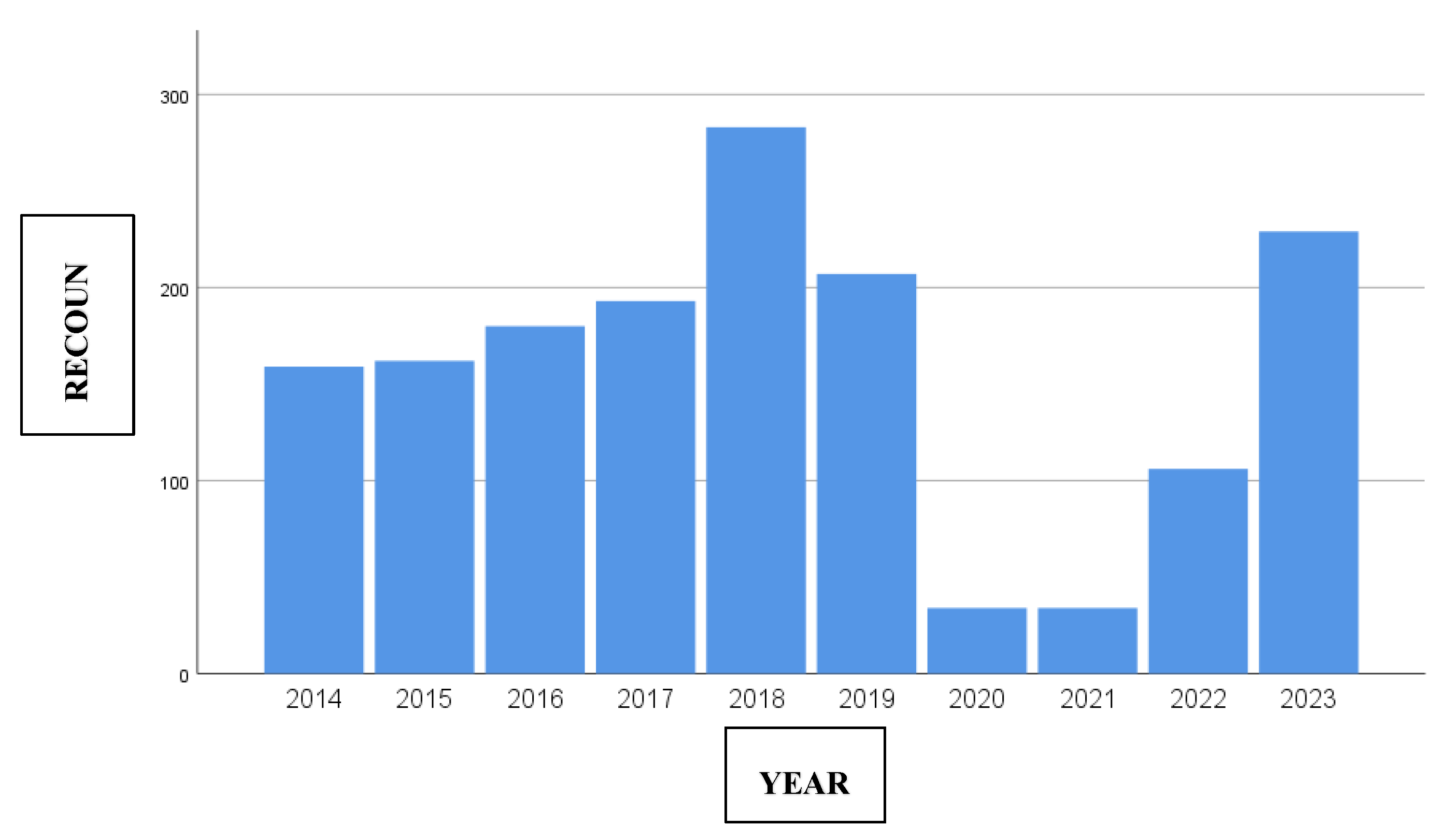

Regarding the incidence of IPD by year, despite the availability of pneumococcal vaccines, a slightly upward trend has been observed since 2014, with a peak in 2018 of 283 cases. During 2020 and 2021, due to the reduction in the number of reported cases and prevention measures implemented by the COVID-19 pandemic, a notable decrease was recorded, with 34 cases per year, representing an 84% decline compared to 2019. Subsequently, an upward trend was observed from 2022, reaching similar figures to those before the pandemic in 2023 (210 cases/year), coinciding with the relaxation of non-pharmacological measures to control the transmission of the virus.

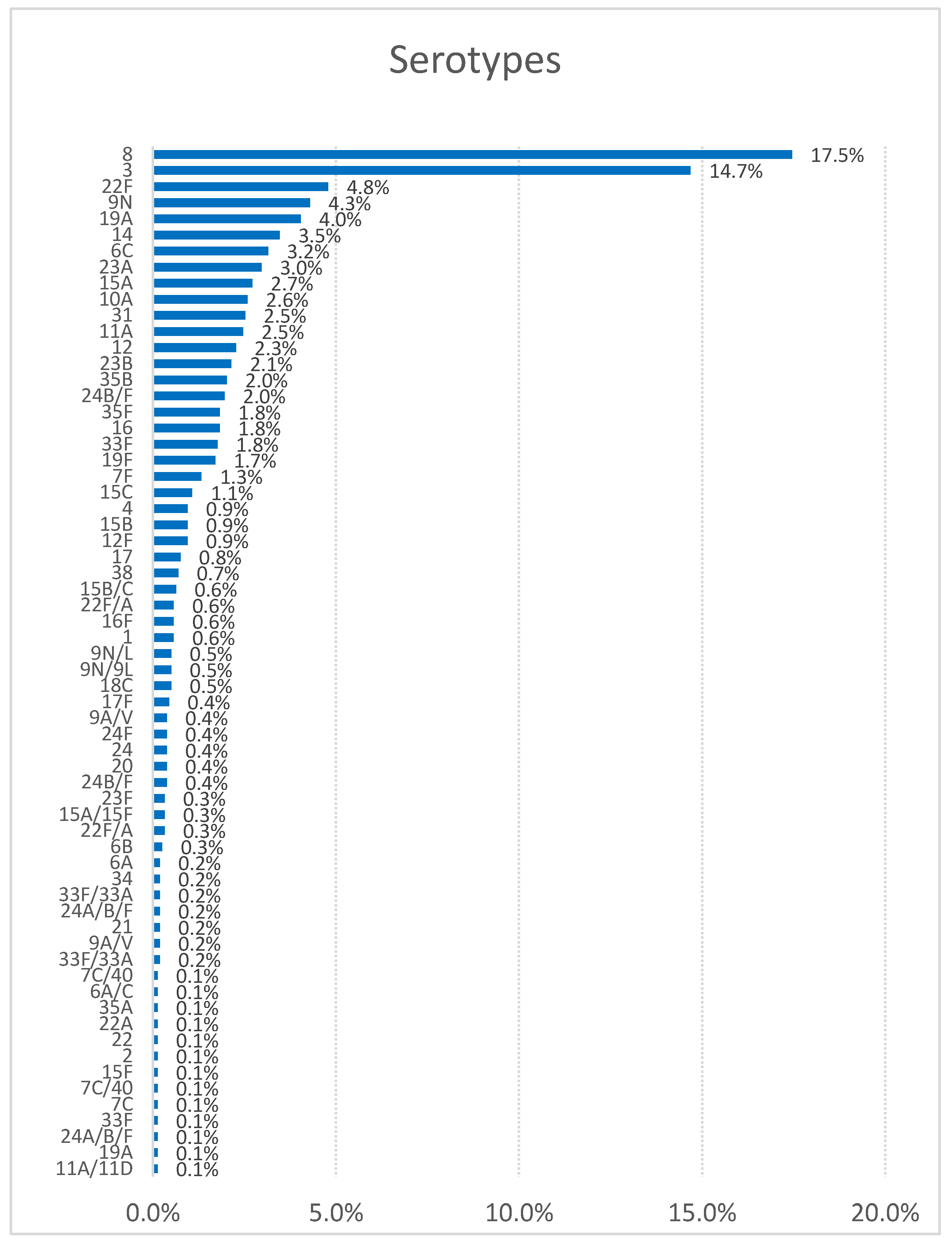

In respect of the distribution by serotypes, there are differences according to the study period and geographic region, underscoring the importance of close monitoring of IPD. Our data are consistent with the annual report of the ECDC [

13], where serotype 8 has been the most frequent in the last six years, followed by serotypes 3, 22F, 9N, 19A, 14, 6C, and 23A. In contrast, in other regions like Serbia (2010-2018), the predominant serotypes were 3, 19F, 14, 6B, 6A, 19A, and 23F [

15]. In the Canada report of 2021-2022, the most common

S. pneumoniae serotypes in cases of invasive disease were varied: in 2021, the predominant serotypes were 22F, 3, 19A, 11A, 6C, and 35B, and in 2022, the distribution changed slightly, with serotypes 22F, 3, 19A, 11A, 6C, and 35B again being prominent, but with some changes in the order of prevalence [

16]. Compared to our report, it can be observed that serotype 8 is not among the most prevalent serotypes in Canada in the period 2021-2022, suggesting geographic variability in the prevalence and response to treatment of different

Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes.

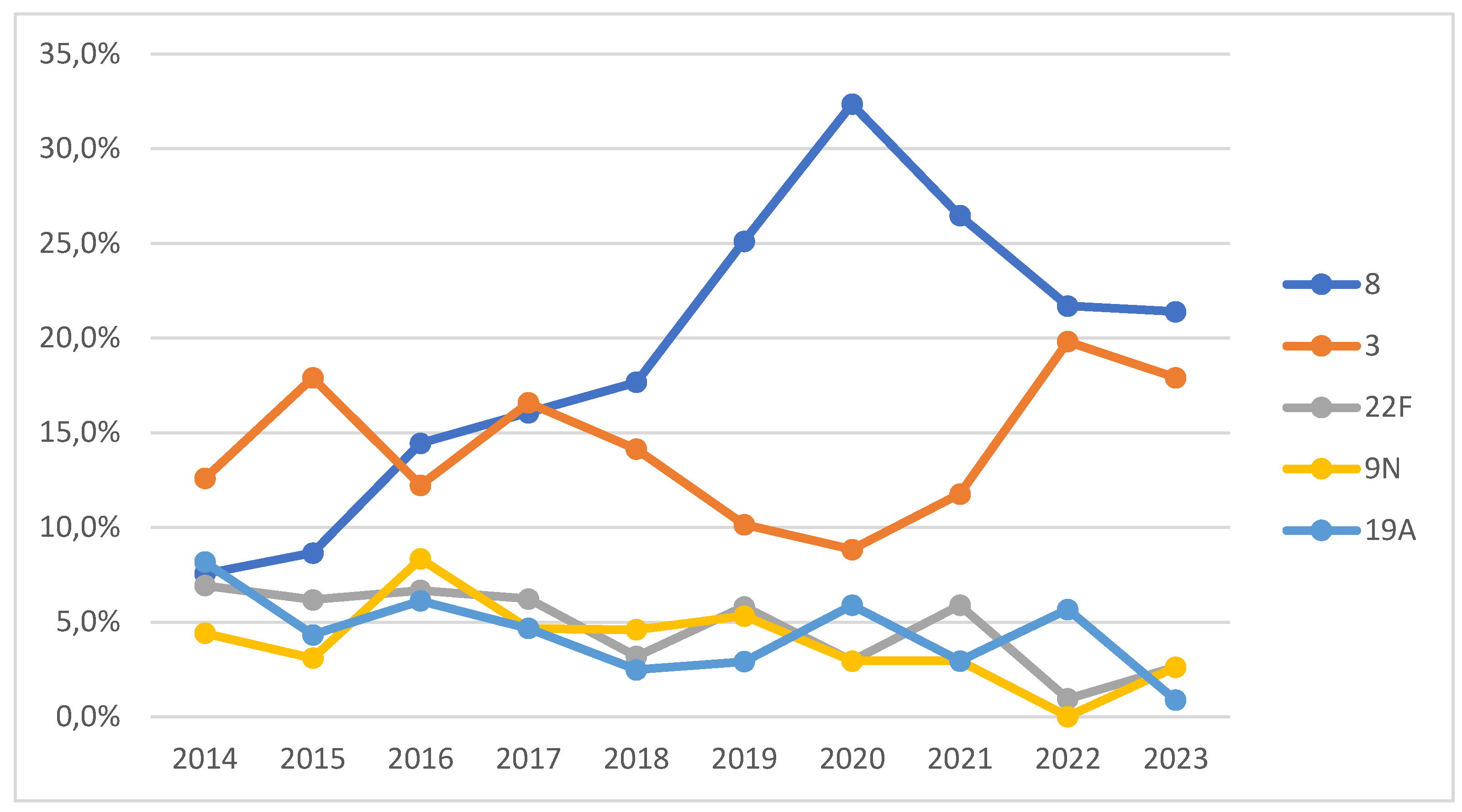

Breaking down by years and analyzing the five most common serotypes in our sample (8, 3, 22F, 9N, and 19A), our results support the phenomenon of indirect immunity following the introduction of the PCV13 vaccine in childhood vaccination in 2015 [

17], especially for serotypes 3 and 19A. This explains the decrease in the incidence of serotype 19A from 2014 to 2023 (from 8% to 1%). Serotype 3 was the most common in 2014, 2015, 2017, and 2018, but from that year onwards, serotype 8 became predominant, relegating serotype 3 to second place, reflecting the effect of PCV13. Over the past 10 years, there has been an increase in the prevalence of serotypes 8 and 3, due both to the increase in IPD cases in adults and children and to the reduction of other serotypes such as 22F, 19A, 14, and 6C. Serotype 8, included in the PPSV23 vaccine, has shown a significant increase since 2019, peaking in 2020 (32%). During the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2021), the serotype distribution was similar to previous years, with an increase in the incidence of serotypes 16F, 20, and 4. Other studies have noted a higher prevalence of serotypes 19A, 3, and 6C in both children and adults during this period [

18].

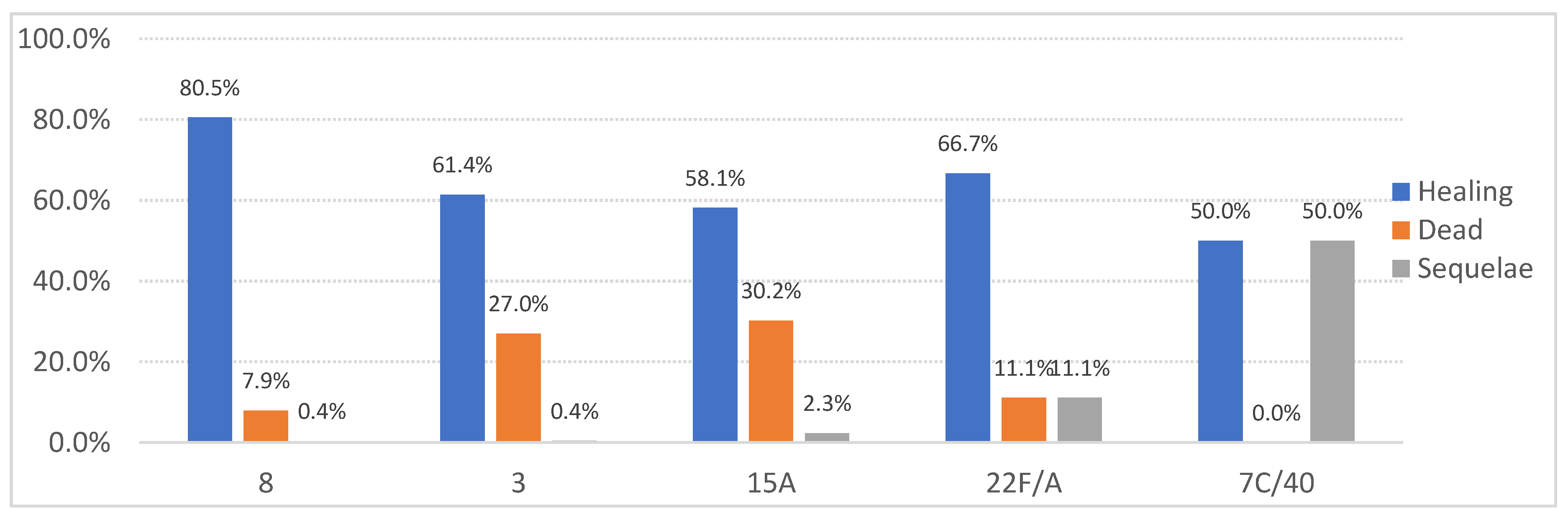

In our study, serotypes 3 and 6C were the most frequently isolated from patients with two or more comorbidities, while serotype 8 was predominant in patients with 0 or 1 comorbidity. When comparing these findings with a study conducted in CV during the period 2007-2012, the order of serotypes associated with the highest percentage of comorbidities was as follows: 22F, 3, 1, 8, 7F, 19A, and 14 [

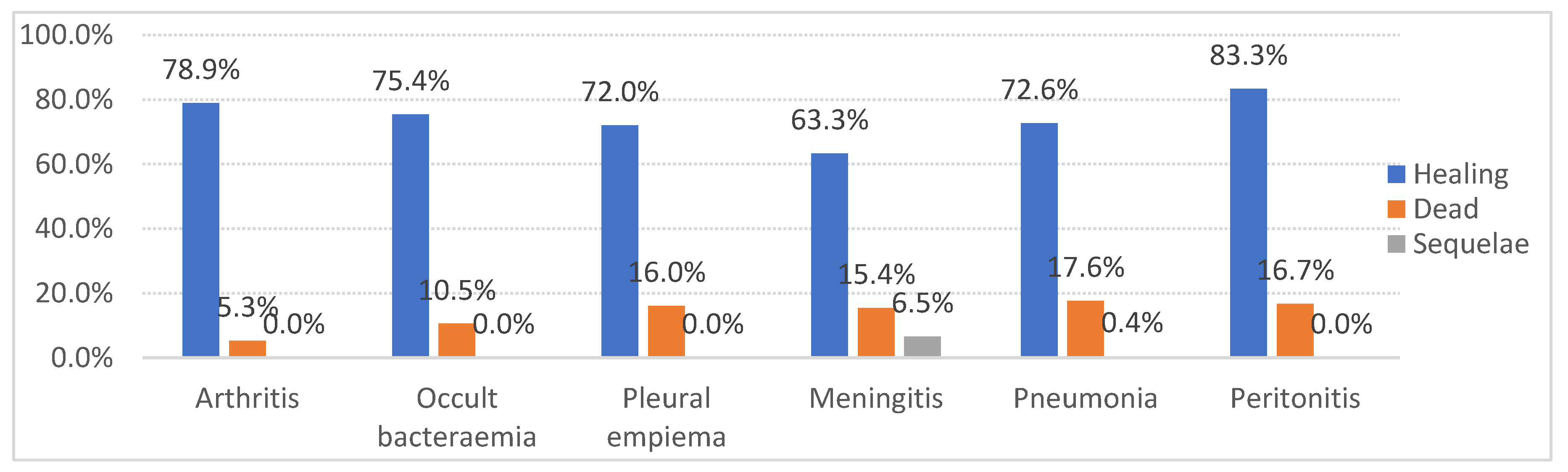

14]. This difference could likely be attributed to the decline in the prevalence of serotypes included in the PCV-13 vaccine, reflecting the impact of its introduction. Regarding mortality by serotype, the highest case-fatality rates in our study were observed for serotypes 3 and 15A. In contrast, the study conducted in the VC during the same period-maintained serotype 3 as one of the most lethal, while serotype 19A was also significant, likely as a secondary effect of the PCV-13 vaccine introduction.

Meanwhile, serotype 8 showed the highest cure rates, consistent with other studies [

19,

20], attributable to its greater susceptibility to standard antibiotic treatments and a lower association with severe comorbidities. These results are particularly significant, as they indicate that, in addition to being associated with severe comorbidities, these serotypes may also be linked to poorer clinical outcomes. This information is crucial for guiding clinical management and prioritizing interventions in high-risk patients.

Our data showed that 22.7% of the patients had received some form of pneumococcal vaccine, which is comparable to other studies, where vaccination rates generally range from 20-30%, depending on geographic location and health policies [

21,

22].

The incidence of pneumonia leading to IPD in our study was 79.1% among unvaccinated individuals and 75.4% among vaccinated individuals. In comparison, other studies reported incidences of 65% in unvaccinated individuals and 48% in vaccinated individuals [

21]. The smaller difference in IPD incidence between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in our study (79.1% vs. 75.4%) may be due to the high percentage of unvaccinated patients and those whose vaccination status is unknown.

A study published by the American Academy of Pediatrics found that pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV-10 and PCV-13) demonstrated high effectiveness against IPD in children under 5 years of age. However, the effectiveness varies depending on the specific serotype and the vaccination schedule, suggesting that the protection provided by these vaccines is not uniform across all serotypes or age groups. The study also emphasizes that significant differences in results can arise depending on the context and population studied, which may introduce potential bias when comparing vaccinated and unvaccinated groups [

23].

Additionally, an analysis of the epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal infections suggests that the incidence of IPD across different age groups may be influenced by factors such as comorbidities and vaccination coverage. In some studies, vaccine effectiveness may be overestimated due to serotype replacement, potentially creating a misleading impression of reduced IPD rates in vaccinated populations [43].

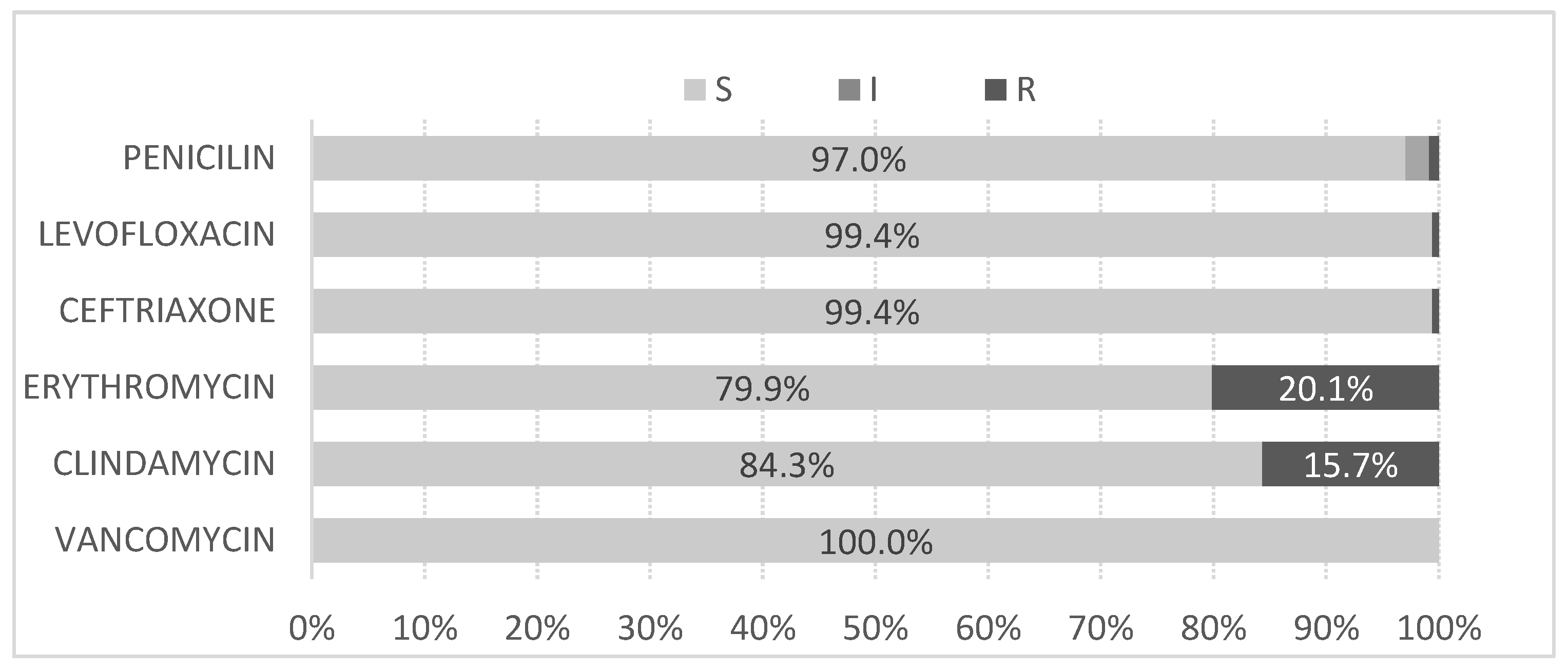

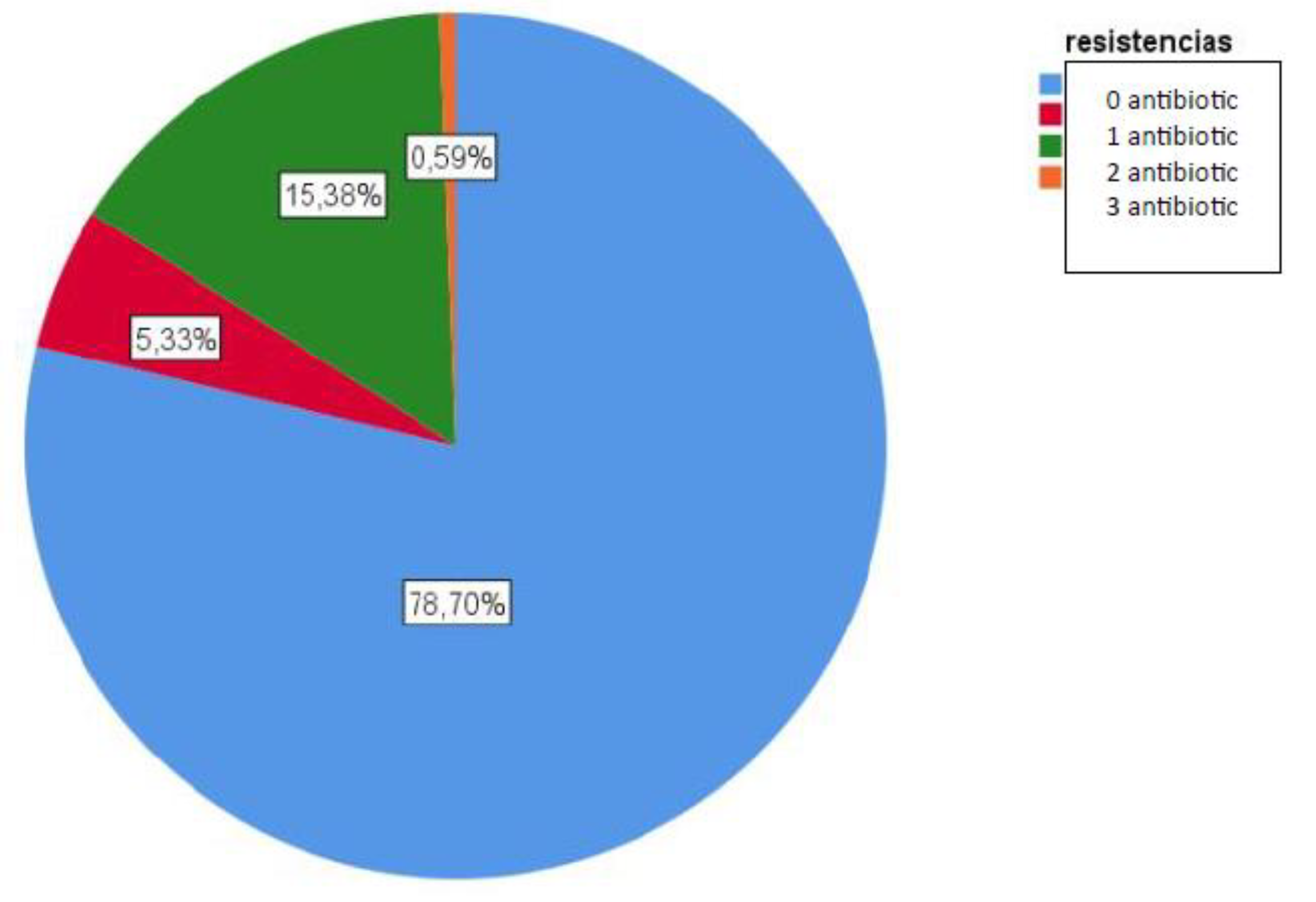

Concerning antimicrobial susceptibility all tested antibiotics showed less than 5% resistance, except erythromycin (20%) and clindamycin (16%). Other studies report lower resistance percentages in Morocco (2.5% for both antibiotics) [

25], and higher percentages for erythromycin in Oman (28.1%) [

26], Iran (71.4%) [

27], and Taiwan (80%) [

28]. Two of the serotypes with the highest resistance rates were 19A and 6C, possibly due to their less metabolic cost of their polysaccharide structure, allowing them to be more capsulated and evade the immune system, persisting as nasopharyngeal carriers [

29]. This behavior could explain the higher prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) lineages of serotypes 19A and 6C [

18,

30]. In our study, they are the only MDR serotypes detected. The serotypes most frequently isolated as susceptible to erythromycin and clindamycin were 3 and 8, with serotype 8 being the most commonly isolated among isolates susceptible to all the tested antimicrobials.

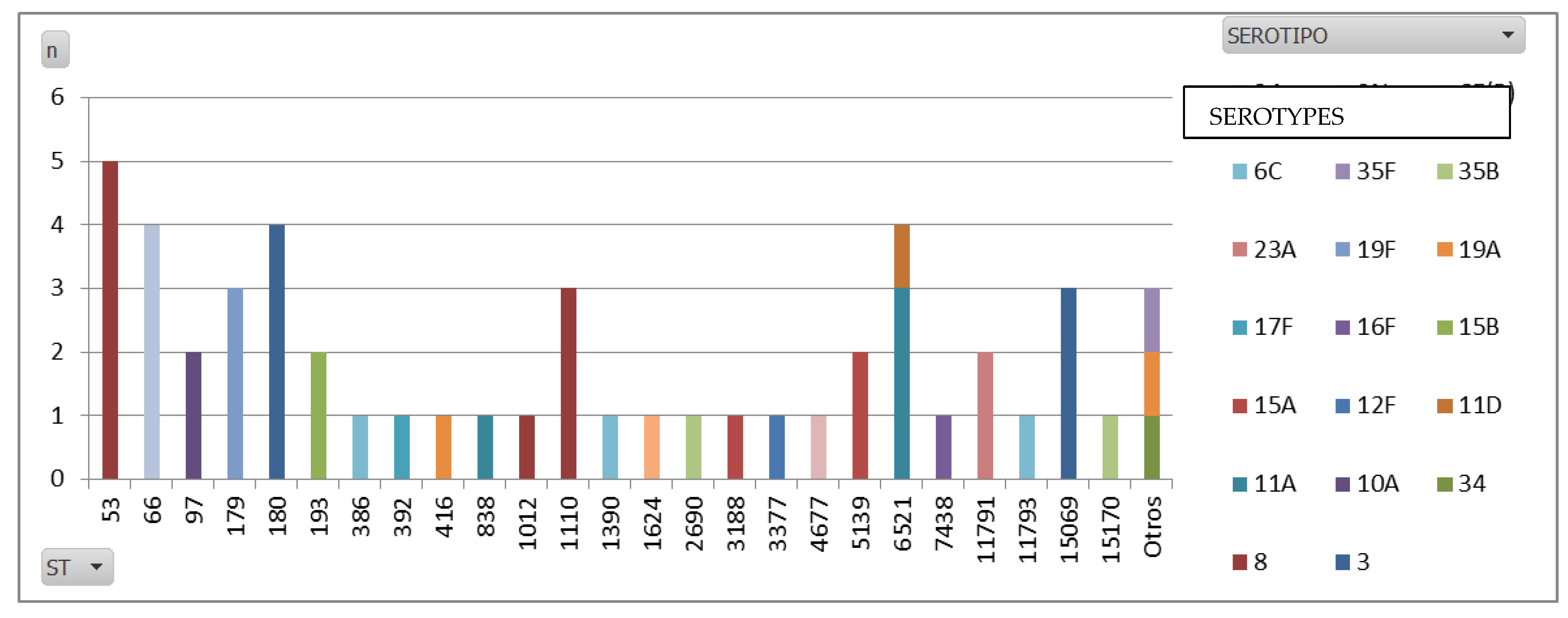

Regarding the whole genome sequencing (WGS) data, ST53 emerged as the predominant MLST in our study, mainly because it is the sequence type (ST) most commonly linked to serotype 8. This finding is in line with global data, as ST53 has consistently been associated with serotype 8, particularly across Europe. Known as the Netherlands8-33 clone, ST53 has been one of the dominant global pneumococcal clones. Additionally, ST1110, another frequent ST found in our serotype 8 isolates, is less reported in the literature. However, emerging regional studies suggest that ST1110 may be locally significant.

As for serotype 3, our data revealed that ST180 was the most prevalent ST, which is consistent with global trends. ST180 is widely recognized as the primary sequence type for serotype 3 [

32], and is also known as the Netherlands3-31 clone.

Differences in the prevalence of these STs could be influenced by local factors such as vaccine use, changes in public health policies, and local genetic diversity. The consistency in the results suggests that the molecular epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae, in terms of serotypes and sequence types, follows global patterns with specific regional variations. The findings underscore the importance of continuous surveillance to adapt vaccination strategies and disease control.

It is important to note that, although our findings are preliminary and have not been previously corroborated by other studies, they provide a valuable starting point for future research. Additional studies examining these associations in different populations and contexts are needed to validate our results and better understand the dynamics between specific serotypes, comorbidities, and clinical outcomes.