Introduction

Bacterial meningitis presents a significant public health challenge due to its potential for severe complications, including permanent sequelae [

1,

2]. While several bacteria can cause meningitis,

Streptococcus pneumoniae,

Haemophilus influenzae, and

Neisseria meningitidis are the primary pathogens involved Incidence and mortality rates vary by region and age group [

4], with pneumococcal meningitis being the predominant type globally, responsible for over 44,500 deaths and 2,720,000 years of life lost in 2019 [

5].

In Argentina, meningitis is a notifiable disease, requiring all suspected cases to be reported to the National Health Surveillance System (SNVS), by its acronym in Spanish) [[6], regardless of the underlying cause. The country also operates a laboratory-based surveillance system for bacterial invasive disease. This system involves a network of public health and private hospitals that refer isolates to the National Reference Laboratories, INEI-ANLIS ‘‘Dr Carlos G. Malbrán”- Clinical Bacteriology and Antimicrobial Agent Divisions – for serotyping, genomic analysis and antimicrobial susceptibility.

The National Immunization Program of Argentina serves as a cornerstone in protecting public health by strategically addressing pathogens linked to bacterial meningitis. In 2012, the program adopted the 13-valent pneumococcal vaccine (PCV13), effectively combatting pneumococcal meningitis and its related ailments. Such proactive measures underscore commitment of Argentina to mitigating the burden of pneumococcal disease and safeguarding the well-being of its population.

Regarding this clinical manifestation, additionally the World Health Organization (WHO) has committed to a roadmap with the ambitious aim of eradicating meningitis by 2030, highlighting the imperative of tackling its root causes [

[8]. Nevertheless, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has thrown a wrench into these plans, reshaping the landscape and affecting various facets, including vaccine coverage. In 2023, the Argentine Ministry of Health released an epidemiological bulletin on meningitis, reflecting their ongoing efforts to monitor and control the disease’s incidence in the country. This update provided valuable insights into the current situation and trends [

9]. Building on this, our study aimed to assess the impact of the PCV13 vaccine on pneumococcal meningitis by analyzing changes in serotype distribution and antimicrobial susceptibility over time. The research focused on children under 6 years old in Argentina, utilizing national disease surveillance data collected over an 11-years period.

Materials and Methods

In this study, we utilized a nationwide, population-based descriptive methodology complemented by a time-series analysis. We evaluated the distribution of serotypes causing meningitis in five periods since 2013 to 2023, it drew upon data from meningitis surveillance in Argentina: 2013-2014 (early post-PCV period), 2015-2016, 2017-2018, 2019-2020-2021 and 2022-2023 (late post-PCV period)

To better understand the possible gap between SNVS and the NRL cases mentioned above, we conducted a comparison between the isolates submitted to the NRL and the cases reported to SNVS by year.

Collection of Bacterial Isolates. From January 2013 to December 2023, invasive isolates Streptococcus pneumoniae from paediatric patients (<6 years old) were collected from 109 hospitals belonging to 24 jurisdictions, as part of the National Surveillance Program.

Isolates and epidemiologic data were submitted to the National Reference Laboratories (NRL), INEI-ANLIS ‘‘Dr Carlos G. Malbrán”- Clinical Bacteriology and Antimicrobial Agent Divisions- for serotyping, susceptibility testing and molecular analysis when required.

Isolates Analysis

Serotype Detection Methodology: The serotypes or groups of all isolates were initially identified using the Quellung reaction [

10,

11].

A minimal quantity of isolates that could not be serotyped via the Quellung reaction underwent confirmation through multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, as previously designed [

12]. Isolates were designated as non-typeable (NT) only if both the Quellung reaction and subsequent sequential multiplex PCR failed to classify them into one of the known serotypes, with confirmation via whole genome sequencing (WGS) validating this outcome.

Establishing Serotype Categories

To delineate serotype categories, cases were organized based on the serotypes covered by various pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs). Specifically, the categorization included serotypes encompassed in PCV13 (1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F and 23F), PCV15 (augmenting PCV13 with 22F and 33F) [

13], PCV20 (extending PCV15 with 8, 10A, 11A, 12F, and 15B/C) [

14], PCV24 (further including 2, 9N, 17F, and 20 to PCV20) [

15,

16]. Serotypes 15B and 15C were grouped as 15B/C due to their potential interchangeability arising from a slipped strand mispairing of a tandem thymine–adenine repeat [

17]. Any serotypes not covered by the specified vaccines were classified as non-vaccine type serotypes. We calculated the theoretical vaccine coverage by adding the proportion of each serotype included in each PCV for the first and last period.

Vaccination Status of the Cases

The vaccination status of the cases was obtained from the mandatory epidemiological forms submitted alongside each isolate to the INEI - ANLIS ‘‘Dr Carlos G. Malbrán”- Clinical Bacteriology Division.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted using the agar dilution method to penicillin, amoxicillin, cefotaxime, meropenem, ceftaroline (from 2014), ceftobiprole (from 2017), erythromycin, clindamycin, tetracycline, doxycycline, chloramphenicol, cotrimoxazole, levofloxacin, rifampicin and vancomycin following the guidelines outlined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [

18,

19]. Ceftobiprole was interpreted according to EUCAST break-points [

20]. Penicillin resistance was determined by a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ≥ 0.12 μg/ml, based on meningitis breakpoints. For cefotaxime, MIC values of 1 μg/ml and ≥ 2 μg/ml were classified as intermediate and resistant, respectively. Quality control strains included

S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 and

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213.

Isolates displaying intermediate or full resistance were categorized as non-susceptible (NS), while multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as non-susceptibility to three or more classes of antimicrobial agents [

21].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R Studio (RStudio Team, 2020). To evaluate changes in the proportions of serotypes and antimicrobial non-susceptibility between the early post-PCV period (2013-2014) and the late post-PCV period (2022-2023), we conducted hypothesis testing using Fisher’s exact test, with a significance threshold set at a p-value of <0.05.

Several plots were employed for their effectiveness in illustrating the variation in isolates received across all months of multiple years. This visual tool enables us to observe the distribution of isolates per month for each year, facilitating comparison and identification of temporal patterns.

To examine the temporal distribution of the data over the years, we utilized appropriate statistical methods and conducted ANOVA to assess the overall significance. The assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances were evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk and Bartlett tests on the residuals. Due to deviations of these assumptions, the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed as a non-parametric alternative to ANOVA. Statistical significance was determined at an alpha level of 0.05.

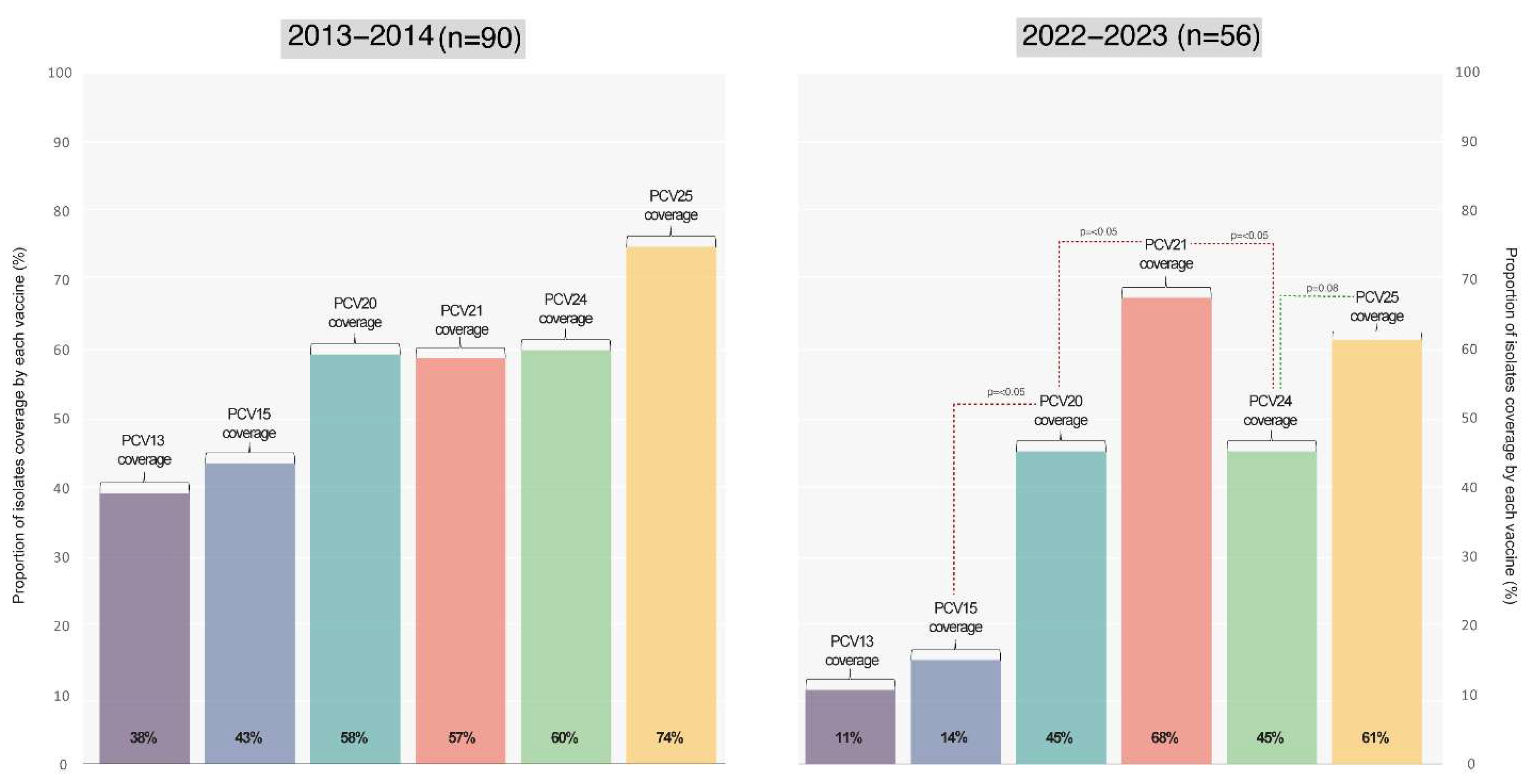

Theoretical Vaccination Coverage

The theoretical vaccination coverage for PCV13, PCV15, PCV20, PCV21, PCV24, and PCV25 was estimated by calculating the percentage of serotypes targeted by each vaccine relative to all isolates. We assessed this vaccine coverage and explored its correlation with the serotypes identified in the Spn isolates. Our goal was to connect each identified serotype to the potential coverage offered by both existing and future vaccines available in Argentina.

Results

Between January 2013 and December 2023, a total of 1,613 isolates from invasive pneumococcal disease in children under 6 years of age were summited to the National Reference Laboratory, INEI - ANLIS ‘‘Dr. Carlos G. Malbrán”. Of these isolates, 333 —representing 20.6% of the total— were obtained from meningitis cases.

Meningitis, as a notifiable disease, requires prompt reporting to the National Health Surveillance System (SNVS), therefore,

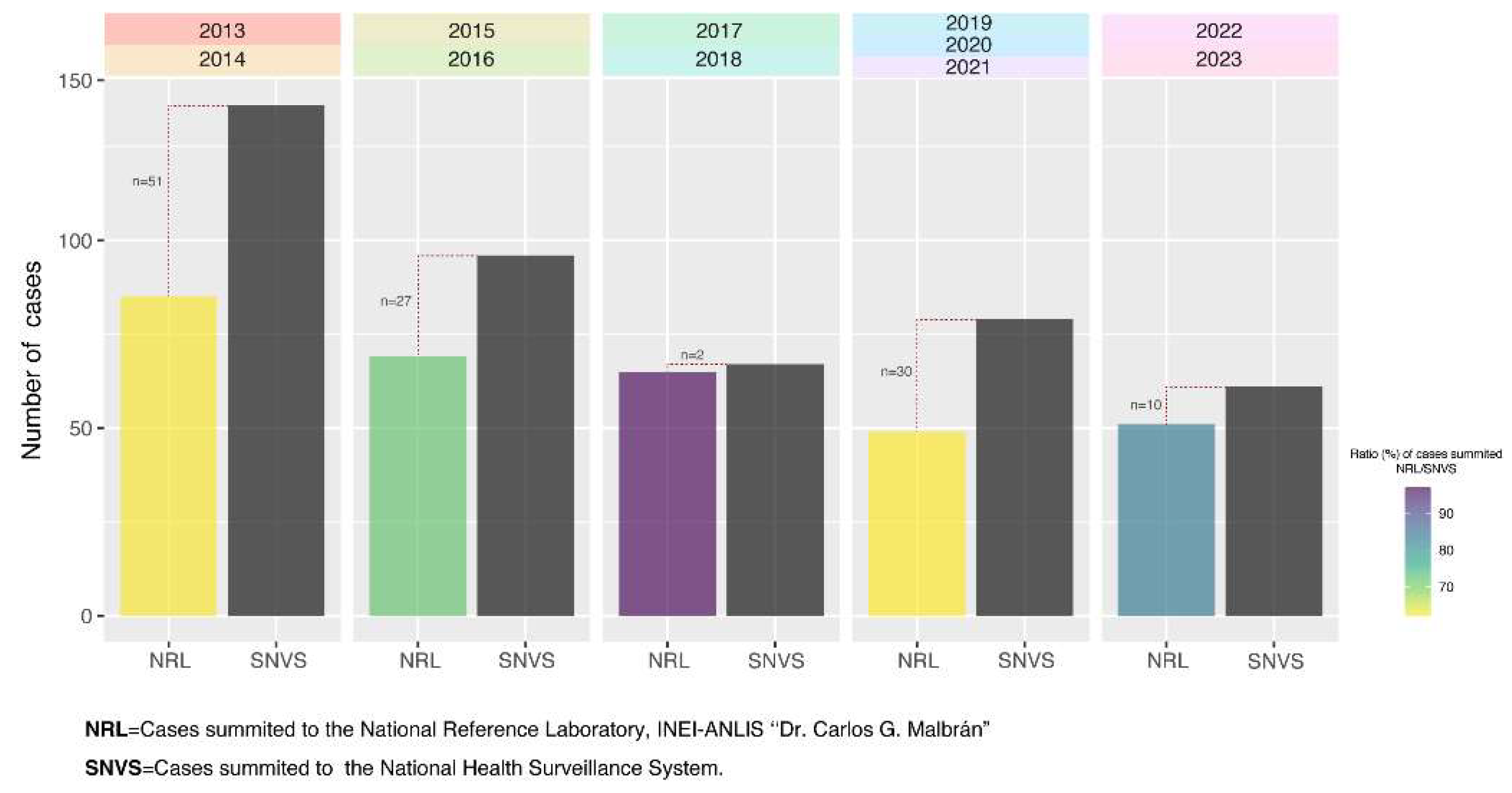

Figure 1 displays the correlation between the isolates submitted to the NRL and the cases reported to SNVS by period.

The average ratio of NRL cases to SNVS cases from 2013 to 2023 was 72.92%. However, this ratio increases to nearly 80% when excluding the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021.

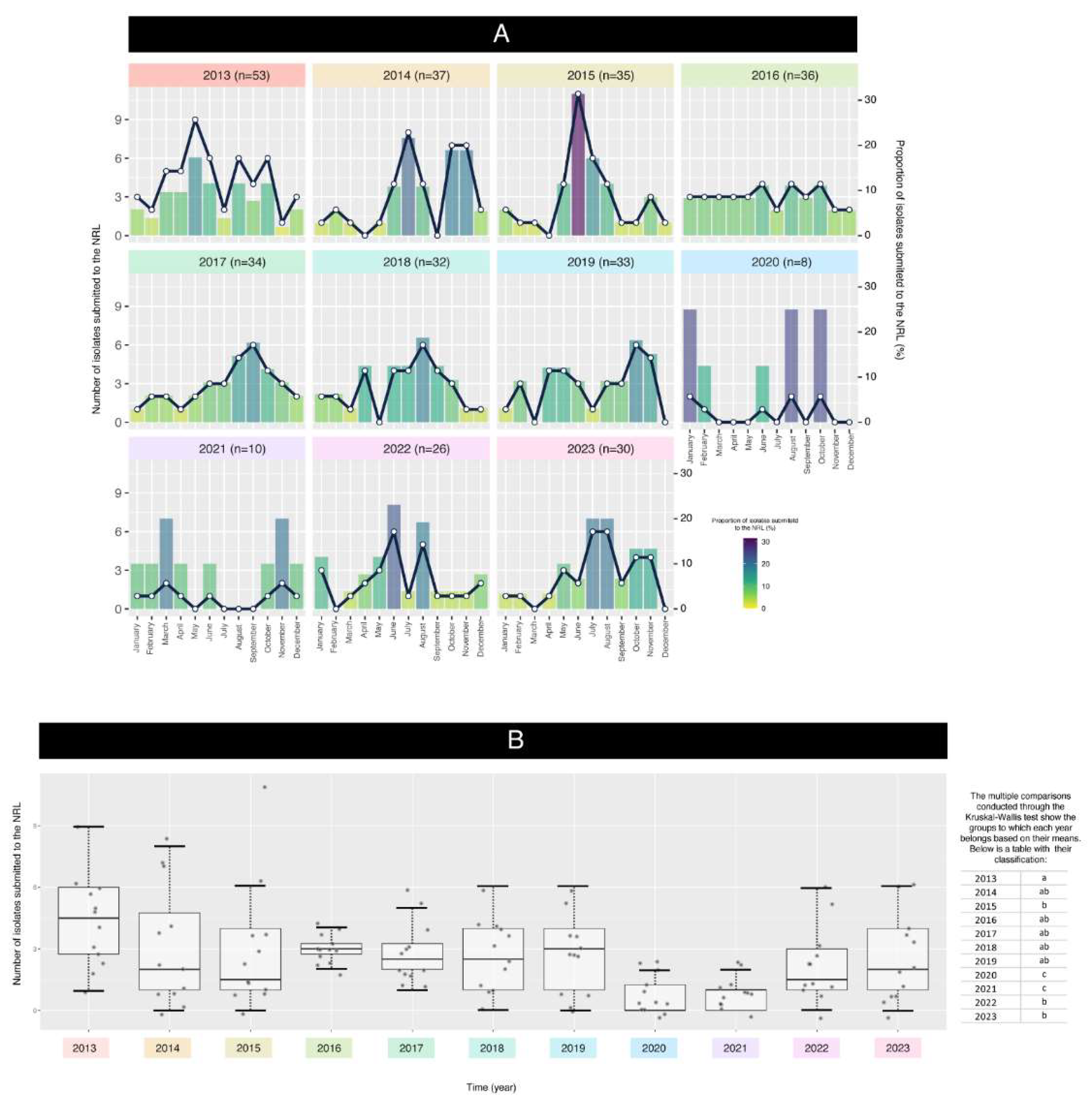

The plot and the boxplot depicted in

Figure 2 A-B highlight the variations in isolates date across different months over several years. Again, the submission of isolates was impacted by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, resulting in fluctuations in the proportion of isolates.

The data analysis aimed to assess the relationship between the year and the isolates submitted to the NRL. A linear regression model (LRM) was initially fitted to the data, revealing significant differences among years (ANOVA p-value = 0.0007). This indicates that the mean values varied significantly across the years.

Residual analysis was conducted to check ANOVA assumptions. The Shapiro-Wilk test showed non-normality of residuals (p = 4.139e-05), and the Bartlett test indicated heterogeneity of variances (p = 2.638e-06). These violations prompted the use of the Kruskal-Wallis test as a non-parametric alternative.

The Kruskal-Wallis test confirmed significant differences between groups (Chi-squared = 35.211, p = 0.000115). Post-hoc comparisons classified years into groups with similar means, represented by letters (e.g., “a,” “b,” “c”). For instance, 2016–2019 shared group “ab,” indicating comparable mean values, while 2020–2021 fell into group “c,” reflecting significantly lower means. These findings highlight the unique patterns of 2020–2021, likely influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Serotypes Distribution

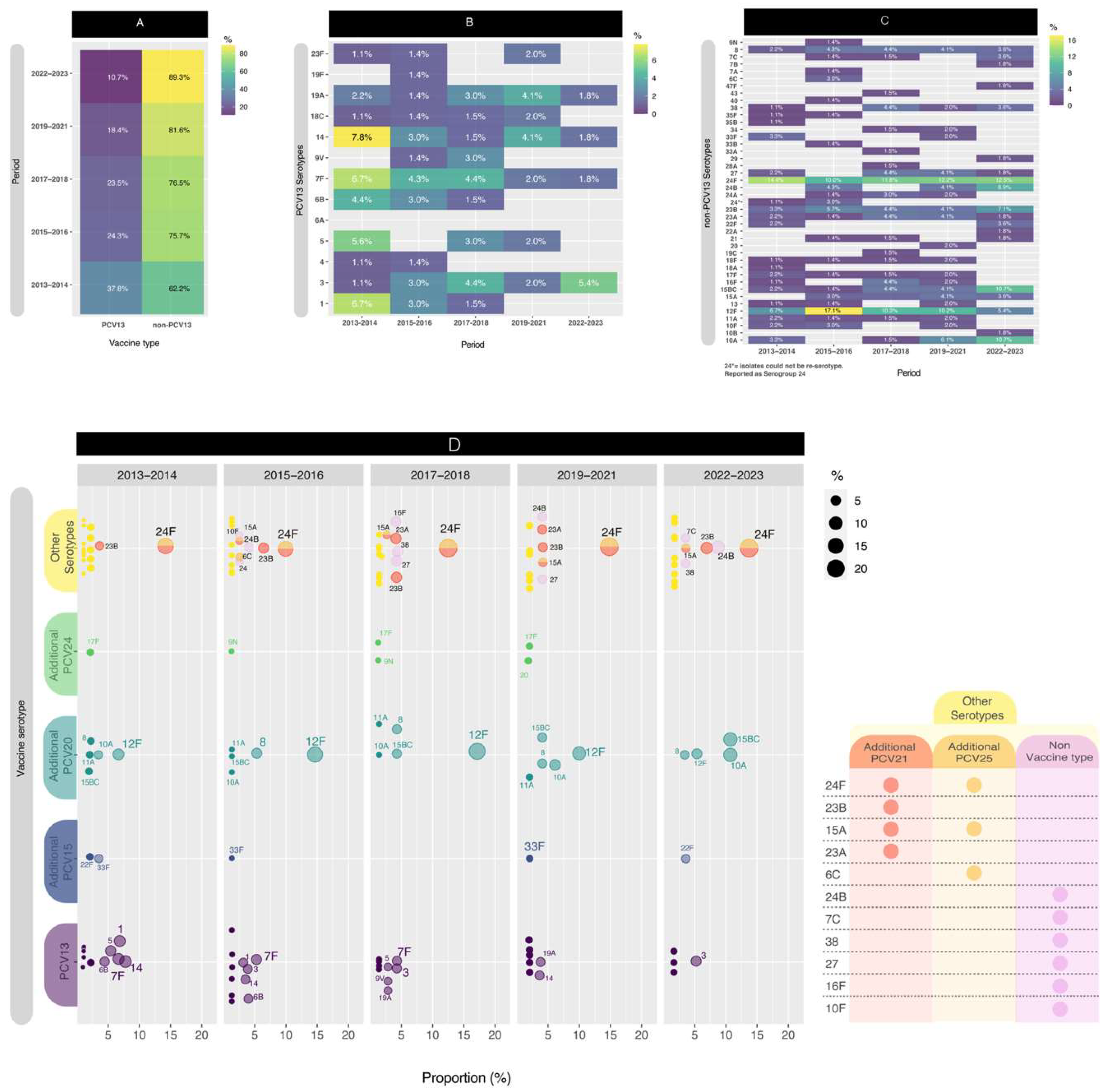

For this segment of the analysis, we conducted a comparison across five distinct periods to enhance data visualization. Initially, we computed the distribution of PCV13 isolates versus non-PCV13 isolates (

Figure 3A). Notably, since early post-PCV period (2013-2014), the proportion of PCV13 isolates has exhibited a consistent decrease, from 37.8% to 10.3% (p<0.05) in late post-PCV period (2022-2023). The PCV13 serotypes, depicted in

Figure 3B, revealed the presence of four serotypes (3, 7F, 14, and 19A) throughout all five comparison periods. When comparing the first period to the last period, significant decreases in PCV13 serotypes were observed for serotypes 1 (p<0.05), 5 (p<0.05), and 14 (p<0.1).

On the contrary, in

Figure 3C, among the non-PCV13 serotypes, notable considerations include serogroup 24, and serotypes 15B/C, 23B, 12F and 10A.

Although, the values are relatively small, serotype 8 still persist across the all periods evaluated.

Serotype 24F remained in high proportion in all periods, between 10.0% and 14.4% while serotype 24B increased from 0.0% to 8.9% (p<0.05). Serotype 23B also was present in all periods, but its higher proportion (7,1%) was the late post-PCV period. Whereas serotype 12F had a temporary increase from 6.7% in 2013-2014 to 17.1% in 2015-2016 (p<0.05) and then decreased in the late post-PCV period to 5.4% (p<0.05), with a value similar to the early-PCV period. On the other hand, serotypes 15B/C and 10A had a significant increase (p<0.05) from 2015-2016 (1,4% and 0,0% respectively) until the late post-PCV period (both 10,7%).

When comparing the early-PCV period to the late post-PCV period, significant decreases in PCV13 serotypes were observed for serotypes 1 (p<0.05), 5 (p<0.05), and 14 (p<0.1). Conversely, non-PCV13 serotypes that exhibited an increase in their proportion include 15B/C (p<0.05), 24B (p<0.05), and 10A (p<0.1).

In order to improve the visualization, we plotted the distribution of PCV13, PCV15, PCV20 and PCV24 serotypes by year (

Figure 3D),

In

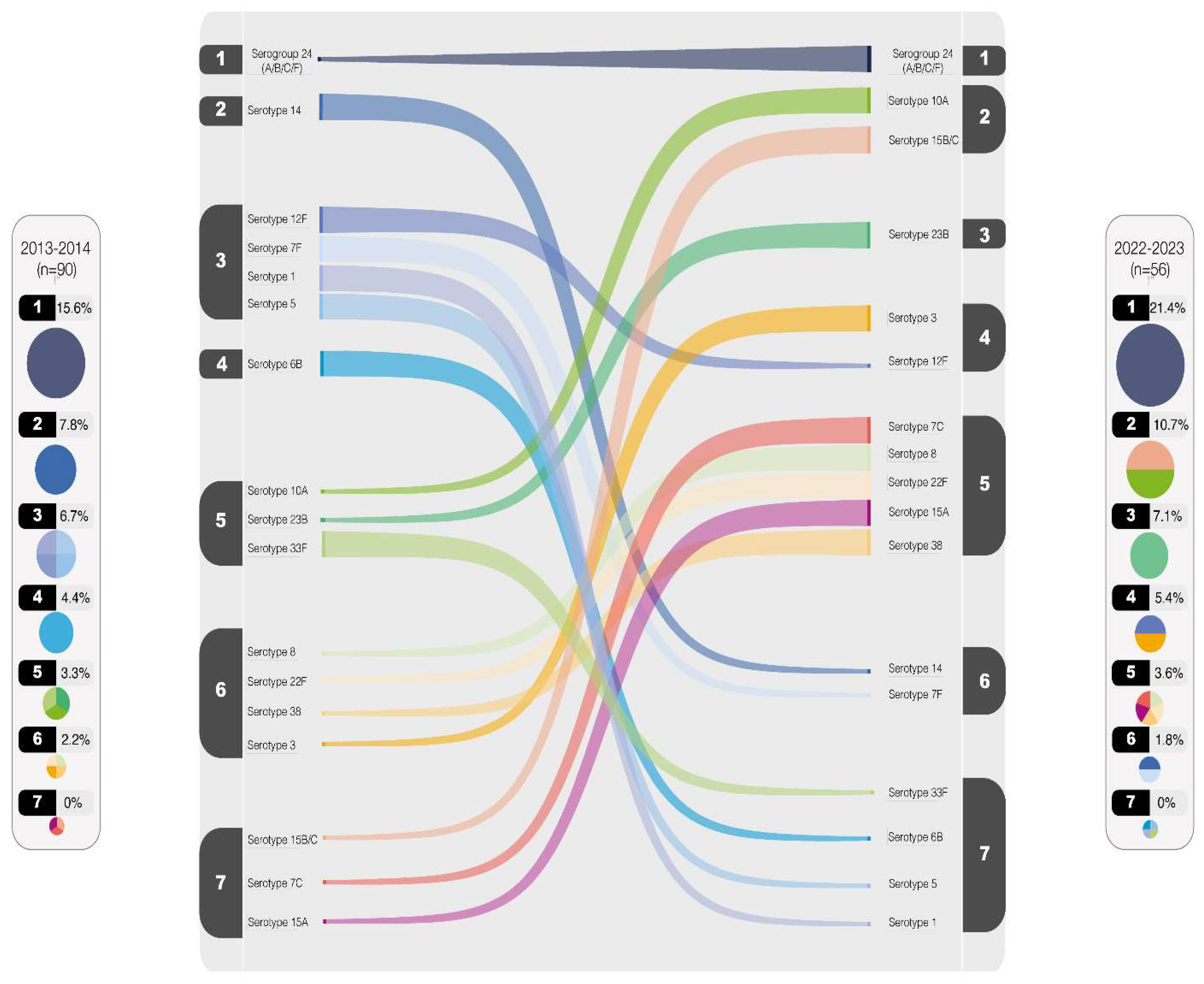

Figure 4, the comparison between serotype rankings in 2013-2014 and 2022-2023 is illustrated. Serotypes with values equal to or greater than 2% were included in the plot. Notably, serogroup 24 has consistently maintained the position as the most prevalent throughout the observed periods. Conversely, certain serotypes, such as serotypes 1, 5, 6B, and 33F, have witnessed a significant decline in circulation. However, other several serotypes persist among the top-rated, exemplified by serotype 3 emerging as the most predominant, with serotypes 7F and 14 following suits, albeit in lesser proportions.

The numbers from 1 to 7 represent the distribution of serotypes in descending order of prevalence, starting with the most frequent serotype (1) and progressing to the least frequent (7), based on their percentage

The varying theoretical vaccines coverages provided by the current PCV and those anticipated from upcoming vaccines entering the market is displayed in

Figure 5

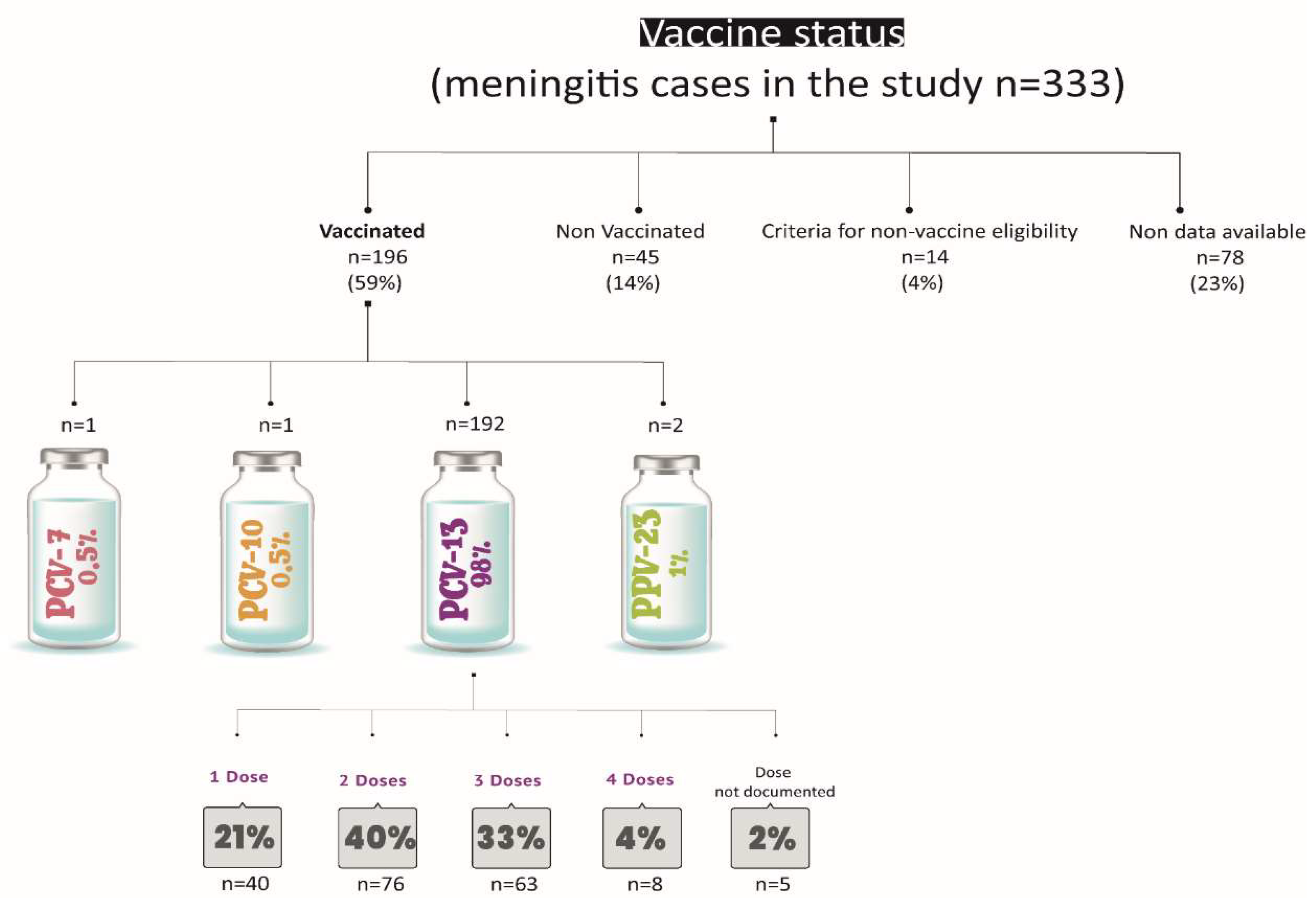

Assessment of Vaccination Status in Cases

Figure 6 provides a summary of the vaccination status of the cases.

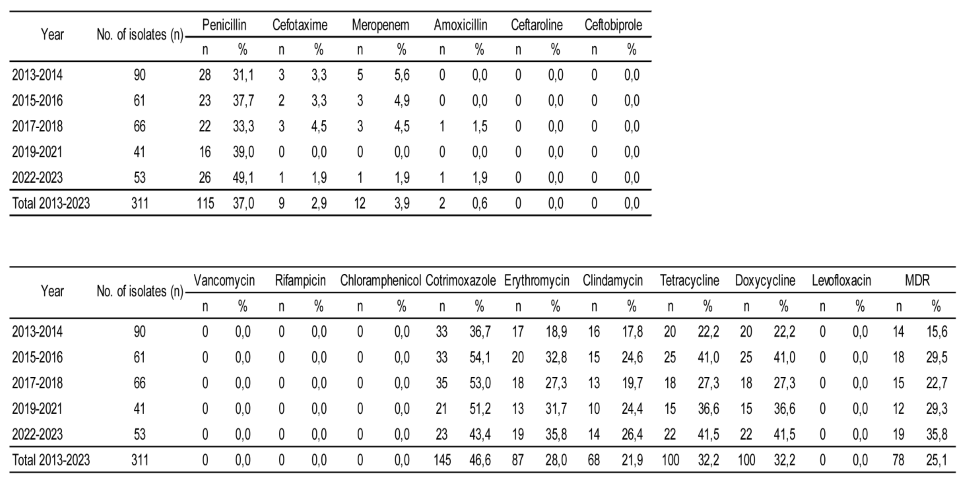

Antimicrobial Resistance Analysis

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed to 311 isolates. Although not all the antimicrobial agents evaluated are useful for the treatment of meningitis, susceptibility tests were performed as part of the National Surveillance.

Table 1 shows the antimicrobial resistance rates of the 311 pneumococcal isolates tested between 2013 and 2023. Considering the complete period of study, the resistance rates were penicillin 37%, cefotaxime 2.9%, meropenem 3.9%, amoxicillin 0.6%, cotrimoxazole 46.6%, erythromycin 28.0%, clindamycin 21.9%, tetracycline and doxycycline 32.2%. All the isolates were susceptible to ceftaroline, ceftobiprole, rifampicin, vancomycin, levofloxacin and chloramphenicol, 78/311 isolates (25.1%) presented multidrug resistance overall. Fifty seven isolates (18.3%) showed resistance to penicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline and cotrimoxazole, and 20 isolates (6.4%) showed resistance to three of them.

If we focus on antibiotics useful for the treatment of meningitis, when comparing the first period (2013-2014) with the last one (2022-2023), significant changes were observed for penicillin but not for cefotaxime or meropenem. Regarding the other antibiotics tested, when comparing both periods, a significant increase was observed in resistance to erythromycin, tetracycline and doxycycline (p < 0.05). MDR rates also showed a significant increase from 15.6% to 35.8% (p < 0.05).

Overall, serotypes 24A/B/C/F, 23B, 15B/C, 14, and 19A accounted for 75.6% of penicillin non-susceptible and serotypes 24A/B/C/F, 15B/C, 19A, 23A, and 6B accounted for 84% of multidrug resistant isolates

The distribution of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for erythromycin, penicillin, cotrimoxazole, and tetracycline by serotype is available in the supplementary data (Fig S1).

Discussion

This study delved into an 11-year span using a nationwide meningitis surveillance database to assess the impact of PCV13 on pneumococcal meningitis epidemiology within the paediatric population of Argentina.

The data analysis revealed that all isolates received by the National Reference Laboratory (NRL) offer a comprehensive understanding of pneumococcal serotype distribution at a national scale. Notably, the proportion of isolates submitted through the national surveillance network for invasive pneumococcal diseases, particularly meningitis isolates, showed a significant ratio between the SNVS report and isolates sent to the NRL. This ratio accounted for 73% of the total reported pneumococcal meningitis cases. However, when excluding 2020 and 2021—the pandemic years during which many laboratories and hospitals faced logistical challenges in submitting isolates to the NRL—this value rises to nearly 80%.

Following the introduction of childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs), our study aligns with previous research [

22,

23,

24,

25] by demonstrating a significant reduction in pneumococcal disease among children in Argentina. This mirrors the findings of the PSERENADE project [

26], which reported a decline in vaccine-targeted serotypes (≤26% across all ages) compared to the pre-vaccination era (≥70% in children). Argentina observed a similar shift, with the prevalence of PCV13 serotypes decreasing from approximately 87% in 2010 [

9] to 10.7% in 2022-2023.

The Argentinean Ministry of Health reported [

9] that cases of Pneumococcal meningitis in 2022 were more than doubled compared to the previous biennium (2020-2021), which had the lowest case count of the past decade. This low cases count during 2020-2021 could be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to lockdowns, social distancing, and personal protective measures. These measures resulted in a significant reduction in

S. pneumoniae isolates, hospital admissions, and the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD). While fluctuations in serotype circulation are evident, it remains uncertain whether these changes are directly linked to COVID-19 or reflect broader secular trends. The same report showed that in 2022 the incidence rate of pneumococcal meningitis in the global population was 0.3 per 100,000 inhabitants compared to pre-pandemic levels in 2019 (0.24/100,000 inhabitants individuals). Additionally, the 2022 data highlight a potential vulnerability within the 2-4 years age group, aligning with findings from the LNR (

see supplementary data, Fig S2). Here, incidence rates were slightly higher compared to the pre-pandemic level in 2019 (0.36 vs. 0.45 per 100,000 inhabitants). This trend coincides with documented declines in pneumococcal vaccination coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccination coverage for both the two-dose primary series and the booster dose declined in 2020, reflecting a similar trend observed throughout the National Immunization Schedule. This decline further exacerbated the coverage gaps observed in previous years. One possibility is that this group received their primary series vaccinations closer to the onset of the pandemic, potentially leading to waning immunity if booster coverage remains low. Additionally, disruptions in routine healthcare access during lockdowns or pandemic-related anxieties could have also played a role in missed vaccinations.

As of this report date, 2023 vaccination coverage for the primary series appears similar to 2021 levels, but coverage for the 12-month booster remains lower [

27]. These coverage rates pose a challenge for achieving optimal disease control. Increased public health efforts are necessary to address vaccine hesitancy, improve access to routine immunizations, and ensure high booster coverage rates across all age groups. Continued monitoring of pneumococcal disease incidence and serotype distribution, alongside vaccination coverage data, is crucial to inform national immunization strategies and improve the immunization coverage. This scenario predisposes to the accumulation of susceptible population, favoring the re-emergence of cases and the appearance of outbreaks caused by vaccine serotypes in the population at greater vulnerability.

Among our findings, notable declines were observed in serotypes 1, 5, and 14, which are included in the PCV13 formulation, between the initial post-vaccination period (2013-2014) and the most recent period (2022-23). However, it is noteworthy that serotypes 3, 7F, 14 and 19A remained present throughout 2019 - 2023, with a proportionate increase observed in serotype 3, although not statistically significant. This increase in serotype 3 requires continued monitoring in the coming years to determine if a closer attention is necessary.

A comparison of serotypes between the PSERENADE project [

26] and our study highlights the emergence of serotypes 24B, 7C, and 38 as notable “outliers,” identified in our work but absent from the investigation by Garcia Quesada et al. Consistent with their findings, we also found that serotype 19A, a PCV13 serotype, was infrequent in our data (1.8%). Conversely, non-PCV13 serotypes such as 15B/C, 8, 12F, 10A, and 22F—associated with higher-valency PCV formulations currently under development—were prevalent in both studies

(Table S1, supplementary data). Collectively, these serotypes accounted for 34% of pneumococcal meningitis cases during our most recent analysis period (2022-2023). Additionally, serotypes 24F and 23B, which are not included in the PCV15, PCV20, or PCV24 formulations, ranked among the most common serotypes in this timeframe.

A study by Lodi et al. from Italy, which examined only six cases of serotype 3 meningitis in children under 9 years old, suggests that serotype 3 may have varying impacts on different clinical presentations. In the post-PCV13 period, serotype 3 invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) demonstrated an overall reduction in cases by 13% [

28]. Particularly notable was the substantial reduction in cases of sepsis and meningitis, with a staggering 92% decrease among individuals born after the introduction of PCV13. While PCV13 appears to be effective against serotype 3 sepsis and meningitis in children, its efficacy against pneumonia is uncertain. However, De Wals et al. [

29], in their review of immunologic and effectiveness data, delve into the indirect effects of PCV13 on serotype 3 disease. The study posits that while PCV13 may provide some level of protection in vaccinated children, this protection is likely to be less robust and possibly short-term compared to protection against other vaccine serotypes. This is in concordance with the results obtained in the present study, where serotype 3 consistently remained prevalent across all periods examined, averaging 3.2%.

The 13-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (PCV-13) was incorporated into Argentina’s National Vaccination Schedule in 2012, utilizing a 2+1 scheme (administered at 2, 4, and 12-15 months of age) with the aim of mitigating the impact of pneumococcal pneumonia and IPD, thereby reducing morbidity and mortality associated with these conditions. Subsequently, in 2017, a sequential vaccination strategy was initiated targeting individuals aged between 5 and 65 years with risk factors for IPD. This strategy involves the administration of both the 13-valent conjugate vaccine and the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine and seeks to decrease the incidence, complications, sequelae, and mortality associated with pneumococcal pneumonia and IPD in these high-risk groups.

The current development and availability of the 20-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV20) presents an opportunity to reassess vaccination schedules, with the dual aim of enhancing coverage of circulating serotypes and facilitating compliance with vaccination programmes. In line with this, a new *Technical Guidelines and Vaccination Manual* has been developed in 2024 [

30]. This document outlines the national strategy for incorporating the 20-valent conjugate vaccine to replace the sequential PCV13-PCV23 schedule for individuals over 5 years of age with risk factors, as well as for those aged 65 and older.

Conjugated pneumococcal vaccines play a pivotal role in diminishing the prevalence of invasive pneumococcal diseases and curbing the circulation of various serotypes. Engineered to target specific polysaccharide capsules on Streptococcus pneumoniae surface, these vaccines enhance the immune response by conjugating polysaccharides with carrier proteins, thereby stimulating the production of protective antibodies. This immune response not only directly shields against targeted serotypes but also prompts a broader immune reaction, offering cross-protection against related serotypes. Consequently, conjugated pneumococcal vaccines exhibit efficacy in thwarting invasive pneumococcal diseases like meningitis and bacteremia, as well as reducing pneumococcal carriage and transmission within vaccinated populations. Given the dynamic nature of pneumococcal serotypes and the potential for serotype replacement post-vaccination, the use of conjugated pneumococcal vaccines proves invaluable in alleviating the burden of invasive pneumococcal diseases and managing serotype circulation, thereby contributing significantly to public health efforts aimed at curbing morbidity and mortality linked to pneumococcal infections.

In this manuscript, we conducted a thorough evaluation of the potential impact of both the current PCV (PCV13) and PCV15/PCV20, alongside promising vaccines (PCV21/PCV24/PCV25). The projected coverage outcomes of these vaccines align with our national epidemiological data, with PCV21 and PCV25 showcasing the highest anticipated coverage rates due to their serotype formulations.

While PCV21 and PCV25 offer expanded coverage by incorporating additional serotypes, it is essential to recognize that they exclude certain serotypes present in PCV13 such as serotypes 1, 4, 5, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F for PCV21, and serotype 6A for PCV25. The implications of a future transition to these vaccines, once they are available, remain uncertain. Such a shift could lead to the resurgence of previously excluded serotypes, adding complexity to the epidemiological situation.

Regarding antimicrobial resistance, a significant increases in the proportion of resistance to penicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline and doxicycline was observed throughout the study period, as well as in MDR. Non-PCV13 serotypes represented 88% of the MDR isolates, being 24F/A/B the most prevalent.

As discussed above, in Argentina, the upcoming next-generation vaccines that would have the greatest impact on reducing antimicrobial resistance would be PCV21 and PCV25, which include serotype 24F. Unfortunately, neither includes serotypes 24A and 24B, which are also associated with MDR meningitis isolates.

This study has some limitations. The epidemiological data relies on forms completed by laboratories and hospitals, resulting in incomplete information about patients’ vaccination status (missing data accounts for 23% of the vaccination status information), chronic diseases, and risk factors. Additionally, outcome data was partially complete. We documented 35 deaths (10.6%) within the study population; however, this figure may not accurately represent the true mortality rate for this condition. According to the Ministry of Health report, the overall mortality rate for pneumococcal meningitis across all age groups was 9.9% in 2022 [

9]. Of 35 deaths documented in this work, 45% (16/35) were among vaccinated individuals, as reported in the epidemiological forms. Among these vaccinated patients, 18% (3/16) received one dose of PCV13, 50% (8/16) received two doses, 25% (4/16) received three doses, and 7% (1/16) had unspecified doses; however, based on their age, two doses would be expected. Notably, 31% (5/16) of the deaths among vaccinated patients were due to PCV13 serotypes, including two cases due serotype 14 and three cases due serotype 3. Intensified efforts to improve the collection of these epidemiological data by the NRL would enable the goal of enriching national surveillance analysis to be achieved in the near future.

Furthermore, not all meningitis cases reported to the SNVS correspond with the isolates submitted to the National Reference Laboratory (NRL). Although it is true that not all cases reported in SNVS were submitted to the NRL, this work shows that more than 70% of the cases registered in SNVS were studied in the NRL. One factor that could contribute to this discrepancy is that only hospitals that participating in the National Surveillance Network typically submit isolates to the NRL. By other hand, the increasing use of molecular methods for detection of Spn, in cases where the culture is negative, could impact these observed differences. No doubt, these methods improve the surveillance of invasive pneumococcal disease.

Conclusion

This study offers a comprehensive analysis of pneumococcal meningitis trends over 11 years, primarily following the introduction of PCV13 vaccination in Argentina. Our findings align with existing evidence, demonstrating a significant reduction in pneumococcal meningitis incidence among children targeted by the National Immunization Program’s PCV13 vaccination schedule. This reinforces the program’s effectiveness in preventing this serious childhood illness. We emphasize the relevance of monitoring both, the disease incidence, the serotype distribution and its associated antimicrobial resistance to guide national pneumococcal vaccination policies and ensure optimal disease treatment and control.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Funding

This study received no specific funding.

Acknowledgments

Argentina Spn Working Group Claudia Hernández, Alejandra Blanco, Vanessa Reitjman: Hospital de Pediatria ‘‘Prof.Dr. Juan P. Garrahan”, Carlos Vay: Htal de Clinicas ‘‘Jose de San Martin‘‘, Claudia Alfonso: Hospital General de Agudos ”Donación Francisco Santojanni‘‘, Claudia Garbaz: Hospital General de Agudos ”Dr. Ignacio Pirovano‘‘, Claudia Etcheves: Sanatorio Franchin, Flavia Amalfa: Hospital General de Agudos” Dr. Parmenio Piñero‘‘, Debora Stepanik: Sanatorio Trinidad Palermo, Hospital Italiano, Liliana Fernandez Caniggia: Hospital Alemán, Marisa Turco, Adriana Procopio, Miryam Vazquez: Hospital de Niños ”Dr. Ricardo Gutiérrez‘‘, Mariela Soledad Zarate: Sanatorio Güemes, Marta Giovanakis: Hospital Británico, Marta Flaibani: Hospital General de Agudos ” Dr. Carlos.G. Durand‘‘, Nora Gómez: Hospital General de Agudos Dr. Cosme Argerich”, Rosana Pereda: Hospital de Niños‘‘ Pedro de Elizalde”, Liliana Guelfand: Hospital General de Agudos ‘‘ Dr. Juan A. Fernández”, Silvana Manganello: Hospital General de Agudos ‘‘ Dalmacio Vélez Sarsfield”, Iliana Martinez: Hospital Churruca Visca, Ana Togneri: HIGA Evita, Andrea Pacha: HIGA San Juan De Dios, Maria L Benvenutti, Mabel Rizzo: HIGA ‘‘Dr. Jose Penna”, Silvia Beatriz Fernandez: HIGA ‘‘Dr. Pedro Fiorito”, Maria Cervelli: HIGA ‘‘Dr. Diego Paroissien”, Mónica Machain: HIGA ‘‘Dr. Abraham F. Piñeyro”, Andrea Fascente: HIGA ‘‘Luisa C. de Gandulfo”, Laura Paniccia: Hospital Municipal de Agudos ‘‘Dr. Leónidas Lucero”, María Adelaida Rosetti: HIGA‘‘ Presidente Perón ”, Hebe Gullo, Maria Susana Commisso: HIGA ‘‘Vicente Lopez y Planes”; Nory Cerda, Carolina Vaccino: Hospital Zonal General de Agudos ‘‘Dr. Carlos Bocalandro”, Victoria Monzani, Laura Morvay: Hospital Materno Infantil ‘‘ Dr. Victorio Tetamanti”, Micaela Sogga: Hospital Municipal ‘‘Dr. Bernardo Houssay, Viviana Vilches: Hospital Universitario Austral, Ana Laura Mariñazky: Hospital ”Dr. Arturo Oñativia‘‘, Appendino Andrea, Laura Biglieri: Hospital Zonal Especializado de Agudos y Crónicos ”Dr. A. Cetrángolo‘‘, Sandra Bognanni: Hospital Zonal ”Gdor. Domingo Mercante‘‘, Cecilia Vescina: Hospital de Niños ”Sor Maria Ludovica‘‘; Johanna Pérez: Hospital Municipal de Pediatría ”Dr. Federico Abete‘‘, Liliana Meccia: Hospital del Niño de San Justo: Marisa Almuzara: HIGA ”Eva Perón‘‘, Alejandra Sale: Hospital Municipal ”Dr. Enrique Sturiz‘‘, Mónica Sparo: Hospital Municipal ” Ramón Santamarina‘‘, Sofía Murzicato: Hospital Municipal ” Dr. Emilio Zerboni‘‘, Gabriela Galán: Hospital Municipal ”Dr. Federico Falcón‘‘, Roxana Depardo: Hospital Municipal ”Ostaciana V. Lavignolle‘‘, Maricel Garrone: HIGA Simplemente Evita, Adriana Fernández Laussi, Graciela Priore: Hospital Nacional ”Prof. Dr. Alejandro Posadas‘‘, Mónica Vallejo: Hospital Privado de Comunidad, Cecilia Barrachia: Hospital Municipal ”Dr. Pedro Orellana‘‘, Adriana Melo: Hospital Zonal General de Agudos ”Virgen del Carmen‘‘, Victoria Ascua: Hospital Interzonal General de Agudos ”Dr. Enrique Erril‘‘, Patricia Lopez: Hospital Zonal Especializado Materno Infantil ”Argentina Diego‘‘, Daniela Carrizo: Laboratorio Central de Salud Pública, Patricia Valdez, Mariela Silvia Farfan: Hospital Interzonal de Niños ”Eva Perón‘‘, Viviana David: Hospital Interzonal ”San Juan Bautista‘‘, Leyla Guadalupe Gómez Capara, Mónica Graciela Sucin, Viviana Isabel Saito; Hospital Pediatrico ”Dr. Avelino Castelán‘‘, Laura Pícoli, Mariana Carol Rey, Isabel Ana Marques: Hospital ”Dr Julio C. Perrando”, Norma Ester Cech: Hospital 4 de Junio ‘‘ Dr. Ramón Carrillo”, Susana Ortiz: Hospital Regional ‘‘ Dr. Victor M. Sanguinetti”, Mario Flores: Lab.de la Dirección de Patología Prevalente y Epidemiologia, Teresa M Strella: Htal Zonal de Trelew, Omar Daher: Htal. Zonal de Esquel, Ana Littvik: Hospital ‘‘Dr. Guillermo Rawson”; Claudia Amareto De Costabella: Hospital Regional ‘‘Dr. Louis Pasteur”, Lidia Wolff De Jakob: Clínica Privada Vélez Sarsfield, Lilia Norma Camisassa: Hospital Regional ‘‘Domingo Funes”, Liliana González: Hospital Infantil Municipal, Patricia Montanaro: Hospital de Niños ‘‘Santísima Trinidad”, Marina Botiglieri: Clínica Universitaria ‘‘Reina Fabiola”, Paulo Cortéz: Hospital Pediátrico Del Niño Jesús, Ana María Pato: Hospital ‘‘Ángela Llano”, Juan Pellegrini: Hospital Pediátrico ‘‘Juan Pablo II”, Lorena del Barco, María Eugenia de Torres, María Silvia Díaz: Hospital Materno Infantil ‘‘San Roque”, María Ofelia Moulins, Luis Otaegui, Norma Yoya: Hospital ‘‘Delicia C. Masvernat”, Nancy Comello, Silvana Vivaldo: Hospital de La Madre y El Niño, Nancy Noemí Pereyra; Hospital Central, Marcelo Tóffoli, Gabriela Granados: Hospital de Niños ‘‘Dr. Héctor Quintana”, Beatriz Resina: Laboratorio Central de Salud Pública, Adriana Pereyra: Hospital ‘‘Gobernador Centeno”, Gladys Almada: Hospital ‘‘Dr. Lucio Molas”, Sonia Flores,Mónica Romanazi: Hospital Regional ‘‘Dr. Enrique Vera Barros”, Ada Zanusso, Adriana Edith Acosta: Hospital‘‘ Dr. Teodoro J. Schestakow”, Alfredo Matile, Beatriz Garcia: Hospital Pediátrico ‘‘Dr. Humberto Notti”, Lorena Leguizamón: Hospital Provincial de Pediatría ‘‘Dr. Fernando Barreyro”, Viviana Villalba: Hospital Escuela de Agudos ‘‘ Dr. Ramón Madariaga”, Cristina Pérez: Hospital Provincial ‘‘Dr. Castro Rendón”, Fernanda Bulgueroni. Hospital ‘‘ Dr. Horacio Heller”, Néstor Blazquez, María Laura Álvarez: Hospital Zonal Bariloche ‘‘Dr. Ramon Carrillo”, Cristina Carranza, Mariela Roncallo: Hospital Area Cipolletti, Gonzalo Crombas, Daniela Durani: Hospital ‘‘Francisco López Lima”, Graciela Stafforini, Maria Gabriela Rivolier: Hospital ‘‘Artémides Zatti”, Cristina Bono, Eloisa Aguirre: Hospital ‘‘Presidente Perón”, Ana Berejnoi: Hospital Público Materno Infantil, Silvia Amador: Hospital ‘‘San Vicente de Paul”, Norma Sponton: Hospital del Milagro, Hugo Castro: Hospital ‘‘Marcial Quiroga”, Marisa López: Hospital ‘‘Dr. Guillermo Rawson”, Ema María Fernández: Policlínico Regional ‘‘Juan Domingo Perón ”, Hugo Rigo: Hospital Privado, Josefina Villegas: Hospital Zonal de Caleta Olivia ‘‘Pedro Tardivo”, Vilma Krause, Alejandra Vargas, Mariel Borda: Hospital Regional de Río Gallegos, Andrea Badano, Adriana Ernst: Hospital de Niños ‘‘Dr. Victor J. Vilela”, Andrea Nepote, Maria Gilli: Laboratorio Central de Salud Publica, Emilce Mendez, Alicia Nagel: Hospital‘‘ Dr. José M. Cullen”, Maria Inés Zamboni: CEMAR, Noemi Borda: Hospital Español, Stella Virgolini, Maria Rosa Baroni: Hospital de Niños ‘‘Dr. Orlando Alassia”, Marciana Cragnolino: Htal. Regional ‘‘Dr. Ramón Carrillo”, Maria Elisa Pavón: Hospital de Niños (CePSI) ‘‘Eva Perón”, Manuel Boutureira: Hospital Regional, Marcela Vargas, Alejandra Guerra: Hospital Regional, Ana Maria Villagra De Trejo, José Assa: Hospital del Niño Jesús María, Fernández de Gandur: Hospital de Clínicas ‘‘Presidente Dr. Nicolás Avellaneda”, Norma Cudmani: Laboratorio de Salud Pública.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- Brouwer, M.C.; van de Beek, D. Epidemiology of community-acquired bacterial meningitis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 31, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiess, N.; Groce, N.E.; Dua, T. The Impact and Burden of Neurological Sequelae Following Bacterial Meningitis: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, T.C.A.; Costa, N.S.; Oliveira, L.M.A. World Meningitis Day and the World Health Organization0 s roadmap to defeat bacterial meningitis in the COVID-19 pandemic era. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 107, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2016 Meningitis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of meningitis, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 1061–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2022, 400, 2221–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Website:https://bancos.salud.gob.ar/recurso/sistema-nacional-de-vigilancia-de-la-salud-snvs-modulo-de-vigilancia-clinica-c2.

- Romanin, Viviana et al. Vacuna anti-Haemophilus influenzae de tipo b (Hib) en el Calendario Nacional de Argentina: portación nasofaríngea de Hib tras 8 años de su introducción. Arch. argent. pediatr. [online]. 2007, vol.105, n.6, pp.498-505. ISSN 0325-0075.

- World Health Organization. Global Vaccine Action Plan: Defeating Meningitis by 2030 Meningitis Prevention and Control; World Health Organization Seventy-third World Health Assembly: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Website: https://bancos.salud.gob.ar/recurso/boletin-epidemiologico-nacional-657-se-23.

- Lund E, Omni-serum Rasmussen P. A diagnostic Pneumococcus serum, reacting with the 82 known types of Pneumococcus. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1966;68(3):458–60.

- Satzke C, Turner P, Virolainen-Julkunen A, Adrian PV, Antonio M, Hare KM, et al. Standard method for detecting upper respiratory carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae: updated recommendations from the WorldHealth Organization Pneumococcal Carriage Working Group. Vaccine 2013;32(1):165–79).

- Carvalho MDG, Pimenta FC, Jackson D, Roundtree A, Ahmad Y, Millar EV, et al. Revisiting pneumococcal carriage by use of broth enrichment and PCR techniques for enhanced detection.

- Merck Sharp; Dohme Corp. A Phase 3, Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Active Comparator-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of V114 in Healthy Adults 50 Years of Age or Older (PNEU-AGE). 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03950622 (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Pfizer. A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of a 20-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Pneumococcal Vaccine-Naive Adults 18 Years of Age and Older. 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials. gov/ct2/show/NCT03760146 (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Skinner, J.; Kaufhold, R.; McGuinness, D. Immunogenicity of PCV24, a next Generation Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases, Melbourne, Australia, 15 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Affinivax. Affinivax Announces the Presentation of Phase 1 Clinical Data for Its MAPSTM Vaccine for Streptococcus Pneumoniae at IDWeek 2020. Available online: https://affinivax.com/press-release-october-21-2020/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- van Selm, S.; vac Cann, L.M.; Kolkman, M.A.B.; van der Zeijst, B.A.M.; van Putten, J.P.M. Genetic Basis for the Structural Difference between Streptococcus Pneumoniae Serotype 15B and 15C Capsular Polysaccharides-PubMed. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 6192–6198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 33th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2023.

- CLSI. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically M07-A9. Approved standard- ninth edition; 2012.

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 14.0, 2024. http://www.eucast.org.

- Magiorakos A-P, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrugresistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18(3):268–81. [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, L.H.; Shioda, K.; Valenzuela, M.T.; Janusz, C.B.; Rearte, A.; Sbarra, A.N.; Warren, J.L.; Toscano, C.M.; Weinberger, D.M. Declines in Pneumonia Mortality Following the Introduction of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines in Latin American and Caribbean Countries. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, D.L.; Kwong, J.C.; Chu, A.; Sander, B.; O0Reilly, R.; McGeer, A.J.; Bloom, D.E. Impact of Pneumococcal Vaccination on Pneumonia Hospitalizations and Related Costs in Ontario: A Population-Based Ecological Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severiche-Bueno, D.F.; Severiche-Bueno, D.F.; Bastidas, A.; Caceres, E.L.; Silva, E.; Lozada, J.; Gomez, S.; Vargas, H.; Viasus, D.; Reyes, L.F. Burden of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) over a 10-year period in Bogotá, Colombia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 105, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Deursen, A.M.M.; Schurink-Van0 t Klooster, T.M.; Man, W.H.; van de Kassteele, J.; van Gageldonk-Lafeber, A.B.; BruijningVerhagen, P.; de Melker, H.E.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Knol, M.J. Impact of infant pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on community acquired pneumonia hospitalization in all ages in the Netherlands. Vaccine 2017, 35, 7107–7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia Quesada, M.; Yang, Y.; Bennett, J.C.; Hayford, K.; Zeger, S.L.; Feikin, D.R.; Peterson, M.E.; Cohen, A.L.; Almeida, S.C.G.; Ampofo, K.; et al. Serotype Distribution of Remaining Pneumococcal Meningitis in the Mature PCV10/13 Period: Findings from the PSERENADE Project. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/2019/05/2024_08_26-cnv_2023-cierre-agosto-2024.pdf.

- Lodi, L.; Ricci, S.; Nieddu, F.; Moriondo, M.; Lippi, F.; Canessa, C.; Mangone, G.; Cortimiglia, M.; Casini, A.; Lucenteforte, E.; et al. Impact of the 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine on Severe Invasive Disease Caused by Serotype 3 Streptococcus Pneumoniae in Italian Children. Vaccines 2019, 7, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wals, P.; Gessner, B.D.; Isturiz, R.; Laferriere, C.; McLaughlin, J.M.; Pelton, S.; Schmitt, H.-J.; Suaya, J.A.; Jodar, L. Effectiveness of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Against Invasive Disease Caused by Serotype 3 in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 68, 2135–2143, Corrigendum to: Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/2018/02/lineamiento_tecnico_vcn20_2024.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).