1. Introduction

Higher education plays a pivotal role in shaping students’ academic and professional competencies, particularly in mathematics—a discipline often regarded as the “queen of science” underpinning numerous other fields [

21]. Calculus, as a foundational course in university-level mathematics curricula, is widely considered critical due to its frequent use as an indicator of academic success at the tertiary level [

22]. Despite its importance, many undergraduate students—and prospective mathematics teachers—continue to encounter significant difficulties in mastering calculus concepts [

23]. This persistent challenge underscores the need to identify and understand the factors that influence students’ academic performance in this subject. Consequently, examining internal psychological factors such as learning interest and learning creativity may offer valuable insights for enhancing calculus instruction and student outcomes. Therefore, investigating the interrelationships among interest, creativity, and academic achievement in calculus remains highly relevant. [

24,

25]

Higher education serves as a critical incubator for developing students’ cognitive, analytical, and professional competencies, particularly in disciplines that form the backbone of scientific and technological advancement. Among these, mathematics holds a distinguished position—often described as the “queen of science”—due to its foundational role in engineering, physics, economics, and data science [

26,

27]. Its abstract nature and logical rigor demand not only procedural fluency but also deep conceptual understanding, making it both a gateway and a barrier in academic trajectories. [

28]

Calculus, as a cornerstone of undergraduate mathematics curricula worldwide, exemplifies this dual role. It is frequently employed as a benchmark for academic readiness and success in STEM fields, with performance in calculus courses strongly correlated with persistence and achievement in engineering and science programs [

29]. Institutions often use calculus grades to predict student retention and progression, reinforcing its status as a high-stakes subject in higher education.

Despite its centrality, calculus remains a significant source of academic struggle for many undergraduates. Empirical studies consistently report high failure and withdrawal rates, particularly among first-year students [

30]. These difficulties are not limited to learners in technical programs; even prospective mathematics teachers demonstrate fragile conceptual grasp, especially in topics involving limits, derivatives, and integrals. Such findings highlight a systemic gap between instructional delivery and meaningful learning in calculus education. [

31]

Traditional, lecture-based pedagogies—often emphasizing symbolic manipulation over conceptual insight—may exacerbate these challenges. In response, scholars have called for a shift toward student-centered approaches that address the affective and cognitive dimensions of learning. This paradigm recognizes that academic performance is not solely a function of intellectual capacity but is deeply intertwined with motivational and dispositional factors. [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]

Among these, learning interest and learning creativity have emerged as pivotal predictors of success in mathematics. Interest functions as a catalyst for sustained engagement, driving students to invest cognitive effort, seek clarification, and persist through complex problems [

6]. Similarly, creativity enables learners to reframe problems, generate alternative solution pathways, and make meaningful connections between abstract concepts and real-world phenomena. [

7]

The interplay between interest and creativity is particularly salient in calculus, where success often hinges on the ability to visualize dynamic change, interpret graphical representations, and apply theoretical principles flexibly. Research suggests that students with high interest are more likely to engage in exploratory learning, while those with high creativity can construct novel mental models to navigate ambiguity. Together, these traits may buffer against the anxiety and disengagement commonly associated with calculus. [

8,

9,

10]

Empirically examining how learning interest and creativity jointly and individually influence calculus achievement is not only theoretically warranted but also pedagogically urgent. Such investigations can inform evidence-based instructional strategies—such as progressive visualization [

11] project-based learning with digital tools (e.g., GeoGebra), or variation theory–informed tasks—that simultaneously nurture motivation and creative thinking. Understanding these relationships is essential for designing inclusive, effective, and responsive mathematics education in contemporary higher education contexts. [

12]

According to [

13], learning interest serves as a robust predictor of academic achievement, accounting for approximately 49.8% of the variance in students’ performance. Similar findings have been reported in other studies linking intrinsic motivation to significantly improved mathematics learning outcomes [

14]. Among advanced undergraduate students, learning interest can reinforce intrinsic motivation, thereby encouraging more intensive and sustained engagement with course material [

15]. Thus, this study is grounded in theoretical evidence affirming that learning interest is instrumental in maximizing academic success. Nevertheless, empirical research explicitly connecting learning interest to calculus achievement in higher education contexts remains scarce. [

16]

According to [

17], learning interest functions as a robust predictor of academic achievement, explaining approximately 49.8% of the variance in students’ mathematics performance. This aligns with broader empirical evidence demonstrating that intrinsic motivation significantly enhances learning outcomes in mathematics [

18]. Among advanced undergraduate learners, interest not only reflects affective engagement but also reinforces intrinsic motivation, thereby fostering deeper cognitive investment and sustained interaction with complex course content [

19]. Collectively, these findings provide a strong theoretical foundation for positing learning interest as a critical determinant of academic success in higher education. Despite this consensus, however, empirical studies that explicitly examine the relationship between learning interest and calculus-specific achievement—particularly within university-level contexts—remain notably limited. This gap underscores the necessity of targeted investigations into how interest operates as a motivational driver in the domain of advanced mathematical learning. [

20]

While learning interest has long been recognized as a key motivational construct in educational psychology, its specific role in advanced mathematical domains like calculus warrants deeper empirical scrutiny. [

41] demonstrated that among first-year engineering students, intrinsic motivation—particularly the desire “to know”—was uniquely predictive of performance on conceptual exam items, even when it did not significantly affect overall scores. This suggests that interest may operate more subtly in higher-order thinking tasks, fostering deeper engagement with abstract principles rather than procedural fluency alone. In the context of undergraduate calculus, where conceptual understanding often lags behind algorithmic competence, nurturing genuine interest could be pivotal in bridging this gap. [

42,

43,

44]

Contemporary learners, especially Generation Z students, exhibit distinct cognitive and affective profiles that challenge traditional pedagogical norms. As [

43,

44] observed, these students are predominantly visual, experiential, and pragmatic learners who disengage from passive, lecture-based instruction. They thrive in environments that offer immediate applicability, interactive visualization, and opportunities for creative expression. When calculus is taught through static formulas and rote practice, it fails to resonate with their learning preferences, thereby dampening both interest and achievement. Conversely, when instructors integrate dynamic tools—such as GeoGebra or other mathematical software—students can

see the behavior of functions, manipulate variables in real time, and connect symbolic representations to graphical outcomes, thereby rekindling curiosity and reinforcing conceptual coherence. [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]

Moreover, creativity in learning mathematics should not be conflated with artistic flair but understood as the capacity to generate flexible, novel, and effective approaches to problem-solving. [

8,

9] argue that mathematical creativity involves divergent thinking, pattern recognition, and the ability to reframe problems—skills that are especially valuable in calculus, where multiple solution paths often exist. [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] further showed that self-regulated, creative learners are more likely to persist through complex integration tasks by constructing personal meaning and alternative representations. Thus, fostering creativity is not merely an enrichment strategy but a cognitive scaffold that supports resilience and adaptability in challenging mathematical contexts. [

16]

Critically, interest and creativity are not isolated traits but mutually reinforcing dimensions of engaged learning. A student intrigued by the real-world relevance of derivatives (e.g., modeling pandemic spread or optimizing business costs) is more likely to explore unconventional solution methods or visualize relationships through digital models—as evidenced in [

17,

18,

19,

20] three-stage pedagogy, where creative projects following software-based exploration led to marked increases in both comprehension and motivation. This synergy suggests that effective calculus instruction must move beyond content delivery toward designing

experiential ecosystems that simultaneously ignite curiosity and empower inventive thinking. Such an approach aligns with variation theory and information processing frameworks, positioning the learner as an active meaning-maker rather than a passive recipient of knowledge. [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]

Learning creativity also plays a crucial role in mathematical performance [

32]. Studies conducted at the secondary level indicate that creativity, in conjunction with learning styles, significantly influences student achievement [

31]. In calculus, which often demands flexible and divergent thinking to solve complex problems, creative problem-solving skills are essential [

33,

34,

35]. Such cognitive flexibility aligns with active learning approaches that encourage students to think creatively when confronting intricate mathematical tasks [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Despite its recognized importance, limited research has specifically examined the contribution of creativity to undergraduate calculus performance. [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]

Learning creativity is increasingly acknowledged as a vital cognitive asset in mathematics education, particularly in domains that require abstract reasoning and non-routine problem solving. [

41] posits that mathematical creativity—characterized by fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration in thought—is not merely an enrichment trait but a core component of deep mathematical understanding. At the secondary level, empirical studies have demonstrated that creativity, especially when interacting with individual learning styles, significantly predicts achievement in mathematics [

42]. These findings suggest that creative learners are better equipped to navigate ambiguity, reframe problems, and construct meaningful connections between concepts. [

43]

In university-level calculus—a discipline marked by its conceptual density and procedural complexity—the demand for creative thinking intensifies. Unlike algorithmic exercises, authentic calculus problems often lack predefined solution paths and instead require students to synthesize multiple representations (algebraic, graphical, numerical, and verbal) and adapt strategies dynamically. [

44] emphasize that both divergent thinking (generating multiple solutions) and convergent thinking (selecting optimal pathways) are essential for high performance in such contexts. This dual cognitive demand aligns closely with [

41,

42,

43,

44] model of successful intelligence, which underscores the interplay between analytical, creative, and practical reasoning in complex task environments. [

44]

Moreover, creativity in calculus learning is not an isolated cognitive function but is nurtured through pedagogical environments that promote exploration and autonomy. [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] argue that mathematical creativity serves as a vehicle for equity, enabling diverse learners to contribute meaningfully through alternative approaches rather than conforming to a single “correct” method. Similarly, [

25,

26,

27,

28] found that self-regulated learners who engage in creative problem-solving—such as constructing visual analogies or designing personal solution frameworks—demonstrate greater persistence and conceptual mastery in integration tasks. These insights resonate with [

29] three-stage progressive pedagogy, where students transition from passive reception to active creation, culminating in team-based development of visual models that embody calculus principles in tangible, inventive forms. [

27,

28,

29,

30]

Despite this growing theoretical and empirical support, research explicitly linking learning creativity to undergraduate calculus achievement remains scarce. Most existing studies focus on general mathematics performance or secondary education contexts, leaving a critical gap in understanding how creative dispositions operate within the unique epistemic culture of university calculus. Given the increasing emphasis on 21st-century skills—including innovation, adaptability, and systems thinking—investigating creativity’s role in advanced mathematical learning is both timely and necessary. Such inquiry can inform the design of inclusive curricula that value multiple ways of knowing and empower students to become not just competent calculators, but imaginative mathematical thinkers. [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]

Student academic achievement is a key metric of educational effectiveness and is commonly assessed through examination scores and standardized assessments at both national and international levels [

9]. Academic performance reflects students’ ability to apply mathematical knowledge analytically and logically [

6,

7,

8]. In contemporary educational discourse, achievement is no longer viewed solely through numerical grades but also encompasses critical and creative problem-solving competencies [

10,

11]. In calculus, deep conceptual understanding of fundamental principles is a decisive factor in determining academic success [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Hence, it is imperative to examine psychological variables—particularly learning interest and creativity—that shape students’ calculus achievement. [

17]

Student academic achievement remains a cornerstone indicator of educational quality and institutional effectiveness, routinely measured through examination scores, standardized tests, and large-scale assessments such as TIMSS and PISA [

9]. In Indonesia, national policy frameworks—such as those outlined by Kemendikbud (2017)—emphasize the use of both formative and summative evaluations to gauge learning outcomes across disciplines, including mathematics. However, contemporary scholarship increasingly challenges a narrow, score-based definition of achievement, advocating instead for a multidimensional view that includes conceptual mastery, reasoning fluency, and the capacity to transfer knowledge to novel contexts. [

7,

8,

9,

10]

In mathematics education, academic performance is not merely a reflection of procedural competence but also of students’ ability to engage in analytical, logical, and reflective thinking. [

18,

19,

20] underscores that high achievement in mathematics correlates strongly with the ability to interpret problems, justify solutions, and connect abstract concepts to real-world phenomena. This perspective aligns with [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] call for recentering numeracy education around critical and creative problem-solving, where success is measured not only by correctness but by depth of understanding and intellectual flexibility. Such competencies are especially vital in advanced topics like calculus, where symbolic manipulation alone is insufficient without conceptual grounding. [

31,

32]

Calculus, as a gatekeeper course in STEM pathways, demands more than algorithmic proficiency; it requires students to internalize dynamic notions such as limits, continuity, and rates of change. [

34] found that misconceptions in differential calculus often stem from superficial learning, where students memorize rules without grasping underlying principles. Consequently, academic success in calculus hinges on deep conceptual understanding—a dimension that is significantly influenced by affective and cognitive dispositions, including motivation, interest, and creativity. These internal variables shape how students approach learning, persist through difficulty, and construct meaningful knowledge. [

33,

34]

Given this, psychological factors—particularly learning interest and learning creativity—warrant rigorous empirical attention as predictors of calculus achievement. Interest drives sustained engagement and cognitive investment [

41], while creativity enables learners to reframe problems, generate alternative solution strategies, and visualize abstract relationships [

42]. In the context of Generation Z learners, who thrive on experiential and visual learning [

43], fostering these traits through innovative pedagogies—such as progressive visualization and project-based modeling—may be key to unlocking higher achievement. Thus, investigating the interplay between interest, creativity, and calculus performance is not only theoretically grounded but also pedagogically urgent in modern higher education. [

44]

Existing literature typically isolates these factors, focusing either on interest or creativity alone. To date, few studies have simultaneously investigated both constructs within a unified analytical framework. Multiple linear regression offers a suitable methodological approach to assess the combined and individual effects of learning interest and creativity on calculus achievement. This statistical technique enables researchers to quantify the unique contribution of each predictor while controlling for the other, thereby yielding a more comprehensive understanding of their joint influence. The existing body of research on mathematics achievement often examines motivational and cognitive factors in isolation. For instance, studies such as [

41,

42,

43,

44] have robustly established learning interest as a key predictor of performance, while others—like [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]—have foregrounded creativity as essential for non-routine problem solving. However, this compartmentalized approach overlooks the synergistic potential between affective and cognitive dimensions of learning. In real classroom contexts, students do not engage with calculus through interest

or creativity alone; rather, these constructs interact dynamically to shape engagement, persistence, and conceptual understanding. [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]

To date, empirical investigations that simultaneously model both learning interest and learning creativity within a single analytical framework remain scarce, particularly in the domain of undergraduate calculus. This gap is consequential: without examining their joint influence, educators risk implementing fragmented interventions—boosting motivation without fostering flexible thinking, or encouraging creativity without sustaining engagement. A more integrated perspective is needed, one that acknowledges the multidimensional nature of mathematical competence in the 21st century, where success increasingly depends on the convergence of intrinsic drive and innovative reasoning. [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]

Multiple linear regression provides a statistically robust and theoretically appropriate method to address this gap. By estimating the unique variance explained by each predictor while controlling for the other, this technique allows researchers to disentangle the relative contributions of interest and creativity to calculus achievement. Such an approach aligns with recommendations from educational measurement scholars who advocate for multivariate models that reflect the complexity of learning processes [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Moreover, the regression coefficients offer interpretable effect sizes—enabling not only hypothesis testing but also practical insights for instructional design, such as which factor yields greater marginal gains when targeted pedagogically. [

26]

This methodological choice is further justified by emerging pedagogical frameworks that treat interest and creativity as complementary levers for transformation. For example, [

27] three-stage progressive pedagogy demonstrates how visual software first captures interest (Stage II) and then scaffolds creative modeling (Stage III), suggesting a developmental sequence where interest may catalyze creative output. Similarly, [

28] found that self-regulated learners leverage interest to sustain effort during creative problem-solving tasks in calculus. By employing multiple regression, this study moves beyond binary comparisons to model how these intertwined constructs jointly shape academic outcomes—thereby contributing both empirical evidence and theoretical nuance to the discourse on effective mathematics education in higher education. [

29]

Related research in STEM education has explored variables such as motivation, self-efficacy, and learning strategies as predictors of academic outcomes [

30]. However, the specific combination of interest and creativity has received limited attention in the context of university-level calculus instruction. Most existing calculus studies emphasize student motivation rather than creative capacities [

31], creating a notable gap in the literature. This study seeks to address this gap by adopting a quantitative approach to empirically examine how interest and creativity jointly influence calculus performance among undergraduate mathematics education students. [

32]

Research in STEM education has long recognized that academic success is shaped not only by cognitive ability but also by a constellation of affective and metacognitive factors. Variables such as motivation, self-efficacy, learning strategies, and epistemological beliefs have been consistently identified as significant predictors of student performance across scientific and mathematical disciplines [

33]. These constructs influence how learners engage with content, persist through challenges, and regulate their own understanding—particularly in demanding courses like calculus, where abstract reasoning and procedural fluency must coexist. [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]

Within this landscape, motivation—especially intrinsic motivation—has received considerable empirical attention. Studies by [

39,

40] demonstrate that students who are internally driven to understand mathematical concepts tend to exhibit deeper engagement and better conceptual performance, even when overall grades remain unaffected. Similarly, [

41,

42,

43,

44] highlight how motivational deficits contribute to persistent misconceptions in differential calculus among both undergraduates and pre-service teachers. While valuable, this focus on motivation often sidelines other equally vital dimensions of the learning process. [

42,

43,

44]

Notably underexplored is the role of learning creativity—defined as the capacity to generate novel, flexible, and effective approaches to mathematical problem-solving—in university-level calculus contexts. Although creativity is increasingly acknowledged as a 21st-century skill essential for innovation in science and engineering [

31], its operationalization in advanced mathematics education remains sparse. Most calculus research treats creativity as peripheral or conflates it with general intelligence, rather than examining it as a malleable, domain-specific disposition that can be nurtured through pedagogy. [

32]

This oversight is particularly striking given the inherently creative nature of calculus itself. Solving non-routine problems involving optimization, related rates, or integration by parts often demands divergent thinking—such as reinterpreting a function’s behavior, constructing auxiliary graphs, or devising alternative substitution strategies. [

33] argue that high-performing students in mathematics leverage both convergent and divergent thinking, yet few instructional studies design tasks that explicitly elicit or assess such creative cognition in calculus settings. [

34]

Moreover, the interplay between interest and creativity—two constructs that are theoretically and empirically linked—has rarely been modeled simultaneously in quantitative studies of calculus achievement. Interest serves as a gateway to sustained cognitive investment [

35], while creativity provides the cognitive toolkit for navigating ambiguity and generating insight [

36]. When examined in isolation, each offers partial explanatory power; together, they may account for a more substantial and nuanced portion of variance in student outcomes.

Current literature reflects a methodological tendency to prioritize single-predictor models or qualitative case studies, limiting generalizability and obscuring interaction effects. For instance, [

37] innovative three-stage pedagogy—integrating lectures, visualization software, and creative modeling—demonstrated enhanced interest and comprehension among Generation Z learners, yet did not statistically isolate the unique contributions of interest versus creativity to final exam scores. Similarly, [

38] focused on error patterns without measuring dispositional variables that might explain those errors. [

39]

This gap is consequential for both theory and practice. From a theoretical standpoint, failing to model interest and creativity conjointly overlooks potential synergies—such as interest catalyzing exploratory behaviors that, in turn, foster creative solution pathways. Pedagogically, it leaves instructors without evidence-based guidance on whether to prioritize motivational interventions (e.g., relevance framing) or creativity-enhancing strategies (e.g., open-ended problem design) when seeking to improve calculus outcomes. [

40]

Addressing this lacuna requires a robust quantitative approach capable of disentangling individual and combined effects. Multiple linear regression is particularly well-suited for this purpose, as it allows researchers to estimate the unique variance explained by each predictor while controlling for the other—a methodological strength emphasized in educational statistics literature [

41]. Such an analysis yields not only statistical significance but also practical effect sizes that inform instructional priorities. [

42]

The present study responds to this need by investigating how learning interest (X

1) and learning creativity (X

2) jointly predict calculus achievement (Y) among undergraduate students in a Mathematics Education program at UIN Syekh Ali Hasan Ahmad Addary Padangsidimpuan, Indonesia. Grounded in self-determination theory and variation theory [

43,

44], the research adopts a correlational ex post facto design with a sample of 30 participants, analyzing data via SPSS to test both overall model fit and individual predictor significance. [

40]

By empirically modeling the dual influence of interest and creativity, this study contributes to a more holistic understanding of the psychological architecture underlying success in university calculus. It moves beyond fragmented accounts toward an integrated framework that acknowledges learners as both motivated agents and creative thinkers—thereby offering actionable insights for curriculum designers, teacher educators, and policymakers committed to enhancing STEM education in diverse, technology-rich learning environments. [

41]

Specifically, this research aims to test the simultaneous effect of learning interest and learning creativity on students’ calculus achievement. The study is contextualized within the Mathematics Education program at Universitas Negeri Medan, where calculus is a compulsory course [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Theoretically, this work contributes to the growing body of literature on mathematics education in Indonesia. Practically, it provides actionable insights for instructors seeking to design learning environments that foster both interest and creativity—key drivers of success in calculus instruction.

2. Method

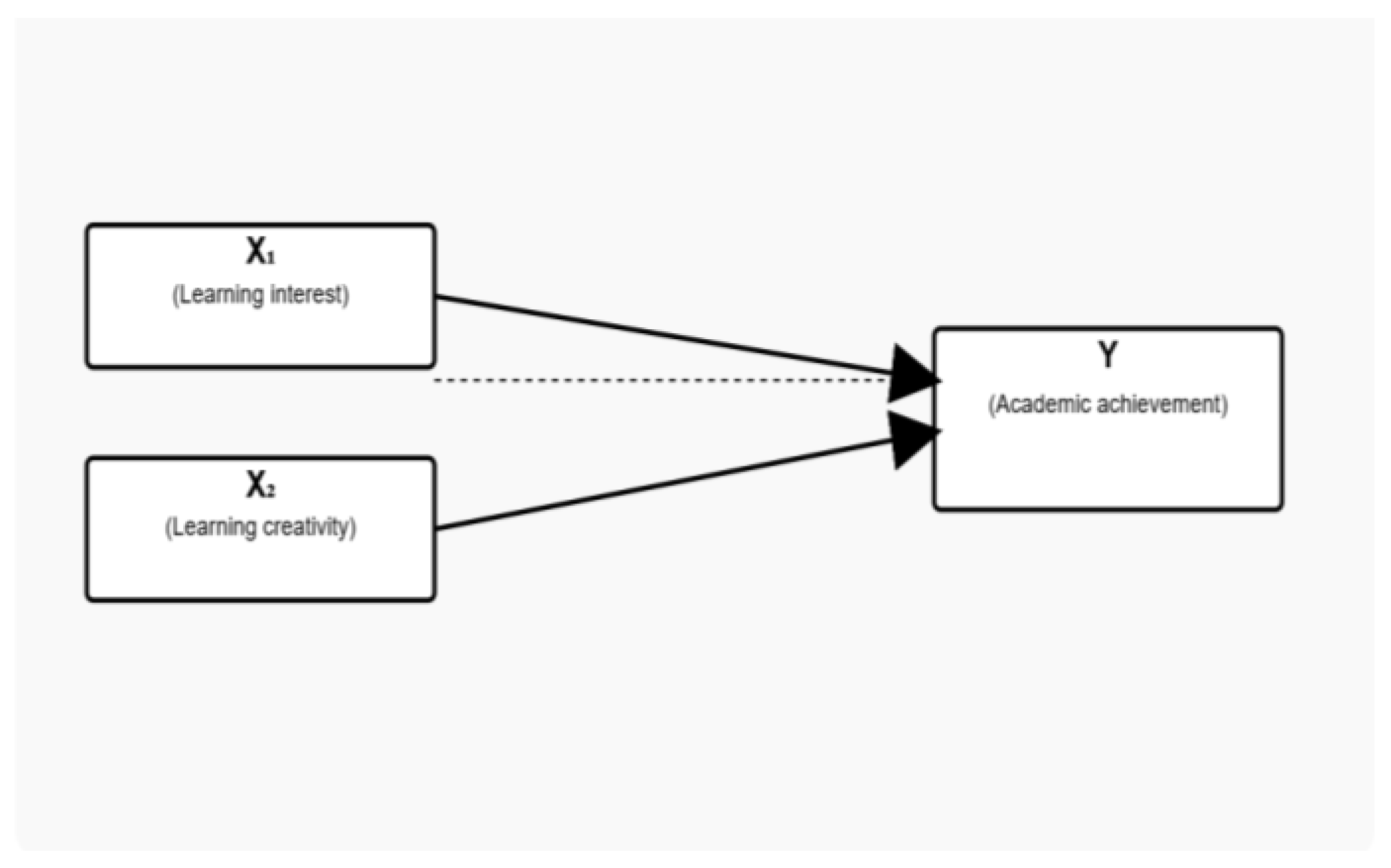

This study employed a quantitative approach using an ex post facto research design with a correlational nature. The research examined two independent variables—learning interest (X

1) and learning creativity (X

2)—and one dependent variable, namely calculus academic achievement (Y) (see

Figure 1).

The population of this study comprised all undergraduate students enrolled in the Calculus course within the Mathematics Education Study Program at Universitas Negeri Medan. A purposive sampling technique was employed, resulting in a sample of 30 students. Data were collected through two primary instruments: (1) self-report questionnaires to measure learning interest and learning creativity, and (2) documentary analysis of students’ academic records to assess calculus achievement.

Learning interest was measured using a 24-item Likert-scale questionnaire, while learning creativity was assessed via a 30-item instrument. Both questionnaires were developed based on established theoretical indicators of learning interest and creativity. Prior to data collection, the instruments underwent content validation by experts in mathematics education and empirical validation using Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient. Instrument reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s Alpha to ensure internal consistency of the items.

Academic achievement in calculus was operationalized as students’ final examination scores in the course. Achievement scores were categorized according to the following scale (see

Table 1):

The categorization of calculus achievement scores into five distinct levels—Very High (80–100), High (66–79), Moderate (56–65), Low (40–55), and Very Low (0–39)—provides a structured framework for interpreting student performance in a nuanced and pedagogically meaningful manner. This classification moves beyond a binary pass/fail interpretation and instead reflects a continuum of mastery, consistent with contemporary approaches to formative and summative assessment in higher education [

9]. Such granular differentiation enables educators and researchers to identify not only underperforming students but also those who demonstrate exceptional conceptual command, thereby supporting targeted instructional interventions. [

10]

This scoring rubric aligns with widely adopted grading conventions in Indonesian higher education, where a minimum passing threshold of 56 is commonly used for core academic courses, including mathematics [

9,

12]. The delineation between “Moderate” and “High” achievement at the 66-point threshold further corresponds to institutional benchmarks for satisfactory versus commendable performance. By anchoring the scale to these locally relevant standards, the study ensures ecological validity while maintaining comparability with international assessment practices that often employ similar quartile- or quintile-based classifications. [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]

From a psychometric perspective, the range-based categories facilitate the transformation of continuous achievement data into ordinal levels, which is particularly useful in correlational and regression analyses involving psychological constructs such as interest and creativity. Although the underlying exam scores are interval-level data, the categorical interpretation aids in communicating findings to diverse stakeholders—including curriculum designers, teacher educators, and policymakers—who may benefit from clear performance descriptors rather than statistical coefficients alone. [

14]

The “Very High” category (80–100) signifies not only procedural fluency but also deep conceptual understanding, as students in this range are likely able to solve non-routine problems, justify reasoning, and transfer knowledge across contexts—competencies emphasized in 21st-century mathematics education [

15]. In contrast, students scoring in the “Low” (40–55) and “Very Low” (0–39) ranges often exhibit fragmented understanding, reliance on rote memorization, and difficulty interpreting graphical or symbolic representations—patterns frequently observed in calculus education research [

16].

Notably, the threshold between “Moderate” and “High” (65 vs. 66) serves as a critical inflection point. In many STEM programs, a score of 65 may represent the minimum for course progression, while 66 or above often qualifies students for advanced coursework or teaching licensure pathways. Thus, this boundary carries both academic and professional significance, particularly for undergraduate mathematics education students who will soon become instructors themselves. Their mastery of calculus directly influences their pedagogical content knowledge and future classroom efficacy [

17].

The use of this five-tier scale also supports comparative analysis with large-scale assessments such as TIMSS and PISA, which similarly segment achievement into proficiency levels [

18]. While those international studies employ item response theory (IRT) to define cut scores, the present rubric offers a pragmatic, criterion-referenced alternative suited to institutional contexts with limited psychometric infrastructure. Despite its simplicity, the scale retains diagnostic utility by highlighting performance gaps that may be linked to affective variables like learning interest or cognitive traits such as creativity. [

19]

Finally, this categorization framework enhances the interpretability of regression outcomes. For instance, a predicted score of Y = 72.3 (falling in the “High” category) conveys more actionable insight than a raw coefficient alone, especially when evaluating the practical significance of a 0.502-unit increase in interest (X1). By mapping statistical predictions onto meaningful performance bands, the study bridges quantitative rigor with educational relevance—thereby fulfilling a key criterion for impactful scholarship in mathematics education research.

Data analysis was conducted in two phases: descriptive and inferential. Descriptive statistics—including measures of central tendency, dispersion, and frequency distributions—were used to summarize students’ levels of learning interest, learning creativity, and calculus achievement. Inferential analysis employed multiple linear regression to examine both the individual (partial) and combined (simultaneous) effects of learning interest and learning creativity on calculus achievement. [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]

Prior to regression analysis, the data were tested for classical assumptions, including normality (using the Shapiro–Wilk or Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), multicollinearity (via variance inflation factor, VIF), and heteroscedasticity (using scatterplots of residuals or the Breusch–Pagan test). All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version unspecified), with a significance level set at α = 0.05. This methodological design is expected to yield empirically robust insights into how learning interest and creativity jointly influence undergraduate students’ performance in Calculus. [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]