1. Introduction

Education is a conscious and systematic effort to create a learning environment that enables students to develop their potential optimally [

3,

5]. According to Law Number 20 of 2003, education functions to develop abilities and shape the character and civilization of the nation [

1,

4,

6]. To achieve this purpose, the learning process must be interactive, inspiring, enjoyable, and motivating for students [

2,

7,

8].

Education is universally recognized as a conscious and systematic effort designed to cultivate a learning environment that enables students to develop their full potential. It encompasses deliberate planning, structured pedagogical approaches, and intentional interactions between teachers and learners. This process not only aims at intellectual advancement but also at holistic human development that includes emotional, social, and ethical dimensions. Thus, education serves as a fundamental pillar for personal growth and societal progress [

50].

In the context of Indonesia, the foundation of educational philosophy and policy is clearly articulated in Law Number 20 of 2003 concerning the National Education System. The law emphasizes that education functions to develop students’ abilities, shape their character, and build a dignified national civilization. It implies that education is not merely an academic process but a transformative endeavor aimed at nurturing responsible citizens who contribute meaningfully to the development of the nation [

51].

The law further mandates that education should aim to produce learners who are intellectually capable, morally upright, and socially responsible. Therefore, the educational process is envisioned as a lifelong journey that promotes balance between knowledge acquisition, character formation, and civic awareness. This holistic orientation underscores the moral and cultural imperatives that accompany the pursuit of academic excellence within the Indonesian educational framework [

52].

To achieve these objectives, the learning process must be designed to be interactive, inspiring, enjoyable, and motivating. Interactivity ensures that learning is not a one-way transmission of information but a dialogic process involving active participation from both students and teachers. Such engagement fosters curiosity, critical inquiry, and collaboration—skills that are essential for navigating the complexities of the modern world [

53].

An inspiring learning process stimulates students’ intrinsic motivation and desire to learn. Teachers play a crucial role as facilitators who model enthusiasm, creativity, and intellectual openness. By creating meaningful connections between subject matter and real-world applications, educators can help students perceive learning as a relevant and rewarding experience rather than a mechanical obligation [

54].

Moreover, an enjoyable learning environment enhances emotional well-being and reduces anxiety, allowing students to learn more effectively. Enjoyment in learning does not imply trivialization of academic content but rather the creation of a psychologically safe atmosphere where students feel valued, supported, and confident in expressing their ideas. Research consistently shows that positive emotions are strongly correlated with deeper cognitive engagement and improved learning outcomes [

55].

Motivation, both intrinsic and extrinsic, is a driving force in the learning process. When students are motivated, they are more likely to take initiative, persist through challenges, and demonstrate resilience in problem-solving. Educators must therefore design pedagogical strategies that tap into students’ natural curiosity and provide opportunities for autonomy and self-directed learning. Motivation-oriented pedagogy encourages lifelong learning habits and self-efficacy [

56].

In addition, effective education requires alignment between curriculum content, instructional methods, and assessment practices. Each component must support the goal of developing the learner’s full potential. Interactive and enjoyable learning is best realized through student-centered approaches such as problem-based learning, project-based learning, and collaborative inquiry. These methods encourage students to apply theoretical knowledge in practical contexts and to engage in reflective thinking [

57].

Furthermore, education in the 21st century demands the integration of technology, creativity, and critical thinking into the learning process. Digital tools and innovative pedagogical models can help make learning more dynamic and accessible. However, the emphasis should remain on maintaining humanistic values—ensuring that technological advancement enhances rather than diminishes personal interaction, empathy, and ethical awareness within education[

58].

Ultimately, the true purpose of education lies in empowering individuals to become autonomous thinkers, responsible citizens, and agents of positive change in society. By fostering an interactive, inspiring, enjoyable, and motivating learning environment, education fulfills its fundamental mission as articulated in Law Number 20 of 2003. It not only develops competencies but also cultivates integrity, creativity, and compassion—qualities essential for sustaining national civilization and global harmony[

59].

Mathematics, as one of the core subjects, plays a crucial role in fostering critical thinking and problem-solving skills [

9,

11,

12]. However, the PISA 2022 survey ranked Indonesia 68th out of 81 participating countries with an average score of 379, significantly below the international average of 472 [

10,

13,

15]. One of the essential competencies to be developed in mathematics learning is mathematical communication skills, which refer to the ability to express mathematical ideas orally, in writing, or through mathematical symbols [

14,

17,

21].

Mathematics constitutes a core subject in school curricula around the world because it fosters logical reasoning, abstraction, problem solving, and critical thinking. It is often regarded as foundational not only for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) fields, but also for everyday decision-making, financial literacy, and civic engagement. In Indonesia, despite sustained efforts to improve quality of schooling, recent international assessment data reveal serious challenges. According to PISA 2022 country notes, Indonesia’s average mathematics score remains significantly below the OECD average, indicating gaps in both achievement and in the consistency of learning outcomes. Students in Indonesia exhibit especially low incidence of high proficiency levels (Levels 5-6) in mathematics, which are important for modelling complex situations, reasoning, and selecting effective problem-solving strategies. These findings underscore the urgency of improving mathematics teaching and learning, particularly in competencies beyond basic calculation and procedural skills. Among such competencies, mathematical communication stands out as crucial but underdeveloped in many contexts [

58,

59].

Mathematical communication refers to the ability of students to express mathematical ideas, reasoning, and solutions in multiple modes: oral, written, symbolic, graphical, or via diagrams and models. It includes not only the transmission of correct procedures, but also the capacity to explain underlying concepts, justify solutions, interpret mathematical representations, and connect mathematical symbols to real-world phenomena. When students communicate mathematically, they are forced to clarify their own thinking, revisit misunderstandings, and engage in deeper reflection. This enhances conceptual understanding, helps in detecting errors, and supports meta-cognitive development. In Indonesia, several recent studies have focused on describing and improving mathematical communication skills among secondary and middle school students. For instance, research into students in agricultural-based regions shows that key indicators such as mathematical modelling, explanation of patterns, and formulating meaningful questions are often weak. Likewise, studies into verbal-linguistic intelligence find that students solving linear programming problems struggle particularly with articulating mathematics in language and symbols coherently [

60,

61].

The PISA 2022 results make it clear that Indonesia’s mathematics performance lags behind many comparable countries. The country note published by OECD reports that Indonesian students’ average mathematics score was 354, considerably lower than many OECD and East Asian economies. Furthermore, socio-economic status remains a strong predictor of mathematics performance: students from the top 25% socio-economic background outperform those from the bottom 25% by about 34 points. While this gap is smaller than the OECD average gap of 93 points, it still points to structural inequalities in access to quality mathematics instruction and resources. The proportion of Indonesian students reaching proficiency at the higher levels (Levels 5-6) is much lower than in many East Asian countries, indicating that very few students are operating at the level of modelling, reasoning, evaluation, and solving complex non-routine problems [

62,

63].

These PISA results have implications for mathematical communication, because achieving high levels of proficiency in mathematics typically requires more than rote computation: it demands abilities to interpret, translate, explain, and argue about mathematical ideas. Students who merely memorize algorithms without understanding often fail to express reasoning or to justify steps in problem solving. Moreover, tasks in PISA often include contexts requiring students to interpret data representations, graphs, and realistic word problems, all of which place high demands on communication skills. The low incidence of high performance in Indonesia suggests that many students struggle with communicating mathematically, not merely with calculation or procedural fluency. Thus, intervention in communication skills is not peripheral but central to raising overall mathematics achievement [

64,

65].

Research between 2020 and 2025 in Indonesia has begun to document both the state of mathematical communication skills and strategies for improving them. For example, the exploratory study “Exploration of Students’ Mathematical Communication Abilities” (Na’im & Mukhlis, 2024) described variations in students’ ability to communicate about flat-sided cubes and cuboids, using NCTM indicators, and found that students in different ability categories show markedly different levels of communication proficiency. Another study, “Efforts to Improve Mathematical Communication Skills in Mathematics Learning in Indonesia” (Epih Purnamasari, 2024), conducted a systematic review of methods/models/media used in efforts to improve communication in mathematics, finding that models like Realistic Mathematics Education (RME), cooperative learning, project-based learning, and media usage are prominent. These studies underscore that mathematical communication is multifaceted and sensitive to instructional design and learning environment [

66,

67].

Of particular note is the study “An Analysis of Senior High School Students' Mathematical Communication Ability Based on Self-Efficacy and Gender” (Nurjanah & Jusra, 2023), which investigated how students’ belief in their own capabilities (self-efficacy) and gender relate to performance on communication indicators. It found that students with high self-efficacy achieve most if not all indicators of mathematical communication, whereas those with lower self-efficacy lag behind. Gender differences were found: male students outperformed female students when self-efficacy was high; however in moderate or low self-efficacy contexts, female students sometimes performed better in certain communication indicators. These patterns suggest both cognitive-psychological and socio-cultural influences on the development of mathematical communication [

68,

69,

70].

Another relevant line of recent research examines the influence of student learning styles, verbal-linguistic intelligence, independence, and confidence on mathematical communication. For instance, research among Madrasah Aliyah (Islamic senior high schools) students in Medan (academic year 2023–2024) explored how self-confidence and learning independence affect communication ability; the results showed that both factors positively correlate with mathematical communication ability. Furthermore, studies in Bandung among grade XI students solving linear program problems found that students’ verbal-linguistic intelligence significantly influences their ability to communicate mathematics, particularly in explaining word-problems, notation, and symbols [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50].

Pedagogical strategies that have been experimentally shown to improve mathematical communication in the Indonesian context include cooperative learning, reasoning-and-problem-solving learning models, and Math-Talk learning communities. For example, “Improving Mathematical Communication Skills Through The Implementation Of Reasoning And Problem Solving Model” (Suryawan et al.) demonstrated that applying reasoning and problem solving models in a classroom action research with 11th grade students raised communication skills significantly, and student learning completeness increased over cycles. Similarly, students’ mathematical communication improved when learning is organized around a “Math-Talk Learning Community” that emphasizes components such as questioning, explanation of thinking, sourcing ideas, and student responsibility for learning [

70,

71,

72].

Media and learning resources also play a key role. In recent years, interactive online learning media have been designed and tested in Indonesia, showing promise in improving communication skills. The study “Improving Students' Mathematical Communication Skills through Interactive Online Learning Media Design” (Harun, Suparman, Hairun, Machmud, Alhaddad, 2021) describes how carefully designed online media facilitate opportunities for students to express, represent, and justify mathematical ideas via interactive tasks. Meanwhile, Think-Talk-Write (TTW) instructional strategy has been used to boost written mathematical communication and student mathematical disposition, finding improvements among students in Jakarta [

72].

Yet, the research also reveals several persistent challenges. Many students still have difficulty in correctly translating word problems into mathematical forms, using symbols with precision, and writing full explanations rather than just result statements. There are also discrepancies between oral communication / dialogic explanation and written communication, where the latter tends to lag behind. Furthermore, socio-economic disparities, teacher preparedness, and resource availability hamper consistent implementation of good communication practices. The gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students remains, not just in raw scores (as PISA shows), but in the quality of their mathematical communication, as advantaged students tend to have more exposure to enriched language, more supportive environments, and better materials [

71].

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced additional complications in the period 2020-2022 and beyond, by disrupting regular schooling, reducing face-to-face instruction, and limiting collaborative learning and discourse opportunities which are vital for communication skills. Although many schools and teachers attempted to use remote or hybrid instruction, issues such as inequitable access to devices, weak internet infrastructure, and lack of teacher training in online pedagogies have limited the effectiveness of such approaches. These disruptions potentially aggravated existing weak spots in mathematical communication, especially written and verbal expression, since these modes often require feedback, discussion, and iterative revisions which remote modalities struggle to provide [

70].

Policy responses in Indonesia have begun to address these issues. One initiative is the National Numeracy Movement launched by the Ministry of Education, which among its goals seeks to raise mathematics PISA scores, improve numeracy, and strengthen students’ capacities in reasoning and problem solving. Targets have been set in Indonesia’s national development plans (RPJMN 2025-2029) for mathematics scores (e.g. aiming toward 419 for mathematics) to be achieved, which implicitly includes improving the kinds of competencies measured by PISA, including communication and interpretation. Teacher training programs are being expanded and numeracy parks as well as family math resources are parts of the effort [

69].

To make these interventions effective, certain pedagogical and curricular reforms are necessary. Curriculum design should embed mathematics communication explicitly in learning objectives, assessments, and classroom activities. For example, tasks should require students to explain their reasoning, write justifications, engage in peer discussion, represent mathematics graphically, and translate between words, symbols, tables, and diagrams. Assessment systems must reward high-quality mathematical communication, not merely correct answers. Teacher professional development is essential, including training teachers in facilitating dialogic classrooms, giving effective feedback on explanations, and designing rich tasks that afford communication [

68].

In addition, equalizing access to resources is critical. Many disadvantaged schools lack textbooks, technological tools, well-prepared teachers, or safe and conducive physical and learning environments. Addressing these inequities requires policy attention: funding, infrastructure, access to digital tools, and support for teachers in remote or under-resourced areas. Socio-economic background also interacts with home environment, parental involvement, and language exposure, which affects how well students can express mathematical ideas. Interventions in the home and community setting (for example, family numeracy programs, community math conversations) could help reinforce communication skills outside school [

67].

Mathematics remains central to developing critical thinking and problem solving in education, but Indonesia’s relatively low performance in PISA mathematics highlights that procedural mastery alone is insufficient. Mathematical communication is a key competency, enabling students to articulate, justify, interpret, and transfer mathematical ideas [

67,

68,

69,

70]. Empirical studies between 2020 and 2025 in Indonesia have documented both challenges and promising interventions: teacher models, learning strategies, media, and assessment reforms. To close the gap with international benchmarks, a multi-pronged approach involving curricular revision, teacher training, resource equity, and policies aligning with international assessments is essential. Future research should continue to monitor improvements in communication, disaggregate findings by socio-economic, gender, and regional lines, and evaluate long-term effects of interventions in large samples [

66,

67].

Preliminary observations at SMP Negeri 1 Padangsidimpuan revealed that students struggle to translate problem statements into mathematical models and to explain their reasoning systematically. Moreover, low learning motivation was identified as another obstacle to achieving desired competencies [

16,

18,

20]. Therefore, an innovative learning model is needed to enhance students’ active engagement and simultaneously improve their mathematical communication skills[

70,

71,

72,

73,

74].

The Problem-Based Learning (PBL) model emphasizes contextual problem-solving to develop students’ critical and collaborative thinking skills [

19,

22,

24]. This model not only facilitates conceptual understanding but also promotes active participation in the learning process [

23,

25]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the PBL model can significantly improve students’ mathematical communication skills and learning motivation [

10,

26]. Hence, PBL is considered a relevant and effective approach for mathematics instruction, particularly in developing students’ higher-order thinking abilities and encouraging meaningful learning experiences [

73].

The Problem-Based Learning (PBL) model represents a pedagogical innovation that positions students as active participants in constructing knowledge through engagement with authentic and complex problems. Rather than presenting knowledge as a set of static facts to be memorized, PBL immerses learners in realistic scenarios that require them to explore, analyze, and synthesize information collaboratively. This approach reflects constructivist learning theory, where understanding is formed through interaction with meaningful contexts rather than passive reception of information. Through this model, students encounter challenges that stimulate inquiry and foster curiosity, encouraging them to identify what they know, what they need to learn, and how to acquire that knowledge. Consequently, PBL supports self-directed learning, metacognitive awareness, and reflective practice—competencies essential for lifelong learning. In the context of mathematics education, PBL enables learners to connect abstract concepts with real-life situations, transforming mathematical ideas into tools for reasoning and decision-making. Moreover, it provides opportunities for students to engage in mathematical discourse, articulate reasoning, and negotiate meaning with peers. Such dialogic engagement not only deepens comprehension but also cultivates the essential skill of mathematical communication. Therefore, PBL offers a dynamic framework for nurturing both cognitive and affective aspects of learning [

74].

A substantial body of empirical research from 2020 to 2025 has consistently confirmed the effectiveness of PBL in enhancing learning outcomes in mathematics. For instance, studies by Zulkarnain and Siregar (2024) and Epih (2024) show that PBL implementation significantly improves students’ mathematical communication, critical thinking, and learning motivation. The model’s emphasis on contextual problem solving and peer collaboration helps students transition from procedural understanding to conceptual mastery. In practice, PBL encourages students to construct and test hypotheses, employ multiple representations, and justify solutions logically—all of which directly contribute to improved reasoning and communication. Moreover, the integration of PBL with digital technologies, such as GeoGebra or learning management systems, has amplified its effectiveness by allowing dynamic visualization and collaborative problem spaces. Empirical findings also demonstrate that PBL classrooms tend to exhibit higher levels of engagement, persistence, and self-efficacy among students compared to traditional lecture-based environments. The collaborative dimension of PBL aligns with social constructivism, where knowledge is co-created through dialogue and shared inquiry. Consequently, learners become more confident in expressing mathematical reasoning, challenging peers’ assumptions, and defending their arguments. These processes collectively advance mathematical literacy and foster the higher-order thinking skills demanded by 21st-century education standards [

75].

The theoretical foundation of PBL is deeply rooted in the works of Dewey, Piaget, and Vygotsky, who emphasized experiential learning, cognitive conflict, and social interaction as catalysts for intellectual development. Dewey’s notion of “learning by doing” underpins the experiential nature of PBL, while Piaget’s idea of cognitive disequilibrium explains how confronting unfamiliar problems promotes schema reconstruction. Vygotsky’s concept of the “zone of proximal development” further supports the collaborative nature of PBL, where learners progress through interaction with more capable peers or facilitators. These theoretical principles converge in mathematics education, where students often grapple with abstract concepts requiring guided exploration. By engaging in structured yet open-ended problem situations, learners develop adaptive reasoning and conceptual flexibility—abilities that transcend rote memorization. Furthermore, the dialogue that emerges in PBL sessions provides fertile ground for mathematical communication, as students are required to articulate hypotheses, explain reasoning, and evaluate alternative solutions. This dialogic process transforms mathematics from an individual cognitive exercise into a shared intellectual endeavor. As such, PBL aligns both with modern constructivist pedagogy and the cognitive demands of the mathematics curriculum [

76].

One of the defining features of PBL is its emphasis on contextualization, which situates learning within meaningful and authentic problem scenarios. In mathematics, this contextual grounding helps bridge the persistent gap between theoretical concepts and practical applications. Students learn that mathematics is not merely an abstract discipline but a language for interpreting and solving real-world challenges—from optimization and modeling to data interpretation. Research conducted across Indonesian universities between 2021 and 2024 indicates that contextual problem-solving environments enhance students’ intrinsic motivation and sense of relevance, leading to higher engagement levels. Contextual tasks also stimulate cross-disciplinary thinking, as learners draw on insights from science, technology, and economics to tackle mathematical questions. The process of discussing and presenting solutions in collaborative groups further cultivates precision in mathematical communication, as ideas must be expressed clearly, coherently, and logically. Teachers act as facilitators, guiding students in questioning assumptions, verifying methods, and articulating conclusions in mathematically rigorous ways. Thus, PBL not only develops problem-solving competence but also refines the communicative and reflective capacities essential for professional and academic success [

77].

Beyond cognitive and communicative gains, PBL contributes to affective and motivational dimensions of learning. By granting students autonomy over inquiry and discovery, it enhances ownership and responsibility for learning outcomes. The open-ended nature of problems invites curiosity, creativity, and persistence—qualities often underdeveloped in traditional mathematics instruction. Studies during the post-pandemic period (2022–2025) reveal that PBL environments yield higher levels of student motivation and engagement, particularly when supported by formative feedback and peer discussion. The opportunity to collaborate, debate, and jointly construct meaning reinforces a sense of community and belonging, mitigating anxiety and fear of failure that often accompany mathematics learning. Moreover, by allowing multiple solution paths, PBL validates diverse ways of thinking and encourages divergent reasoning. Students thus learn that errors are not failures but integral components of the learning process. Such a mindset shift is crucial for developing mathematical resilience and confidence—two predictors of long-term academic achievement in quantitative fields [

78].

Teacher roles in PBL-based mathematics classrooms have also evolved significantly. Instead of serving as the sole source of knowledge, teachers now act as facilitators, mentors, and designers of learning environments. They craft complex, open-ended problems, scaffold inquiry, and model metacognitive strategies while encouraging autonomy. Teacher facilitation requires balancing guidance and independence—providing enough structure to maintain focus while allowing sufficient flexibility for exploration. In Indonesia, teacher readiness has been identified as a key determinant of successful PBL implementation, as reported in national surveys of mathematics educators from 2023–2024. Professional development programs emphasizing lesson study, reflective practice, and technology integration have shown promise in strengthening teachers’ facilitation skills. When teachers effectively guide student inquiry, they foster rich mathematical dialogue that mirrors authentic disciplinary reasoning. Such practice transforms the mathematics classroom into an active learning ecosystem characterized by curiosity, collaboration, and inquiry-based exploration. Consequently, teacher professional competence in PBL pedagogy emerges as a critical factor in sustaining long-term educational reform[

79].

The Problem-Based Learning model represents an empirically validated, theoretically grounded, and pedagogically robust approach for advancing mathematics education in Indonesia and beyond. By integrating contextual problem solving, collaborative inquiry, and reflective dialogue, PBL nurtures both cognitive and communicative competencies essential for success in the modern world [

80]. The literature between 2020 and 2025 provides strong evidence that PBL enhances mathematical communication skills, motivation, reasoning, and conceptual understanding across diverse educational levels. Furthermore, its compatibility with constructivist and socio-cultural learning theories ensures relevance to the developmental and social dimensions of learning. Nevertheless, the model’s success depends on factors such as teacher expertise, institutional support, curriculum design, and assessment alignment. Therefore, continuous professional training, integration of digital tools, and evidence-based evaluation remain critical for optimizing PBL outcomes. As the global education community seeks to enhance problem-solving capacity and higher-order thinking among learners, PBL stands as a transformative model capable of addressing the enduring challenges in mathematics education and preparing students for complex real-world demands.

3. Results and Discussion

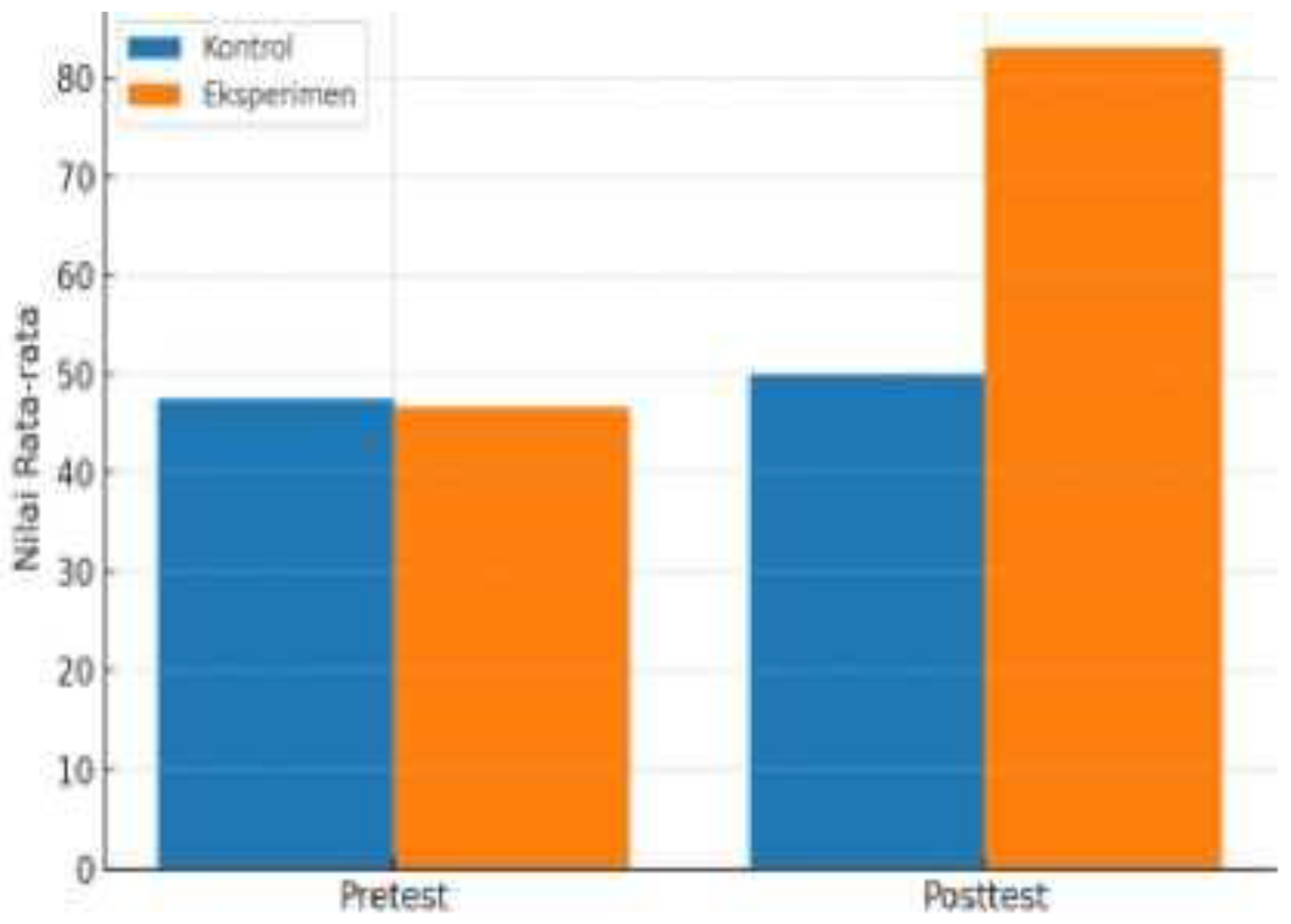

The results presented in

Table 1 demonstrate a substantial improvement in the experimental class compared to the control class. Prior to the implementation of the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) model, both groups had nearly identical average pretest scores (47.58 for the control group and 46.73 for the experimental group), indicating similar baseline abilities. However, after the learning intervention, the posttest mean score of the experimental class increased significantly to 83.04, while the control group only reached 50.00.

This finding indicates that students exposed to the PBL model experienced a higher degree of conceptual understanding and skill development compared to those who underwent traditional instruction. The PBL environment encouraged active participation, critical thinking, and collaborative problem-solving, which contributed to students’ enhanced mathematical communication skills.

The findings of this study demonstrate that students exposed to the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) model developed stronger conceptual understanding and more advanced problem-solving skills than their peers taught through conventional instructional approaches. This difference can be attributed to the student-centered nature of PBL, which prioritizes exploration, inquiry, and reflection over rote memorization. By engaging in real-world problems, students internalize mathematical principles in a meaningful context, resulting in deeper cognitive processing and longer retention of knowledge [

80].

Moreover, the PBL environment encourages active participation throughout the learning process. Students are no longer passive recipients of information; instead, they become active constructors of knowledge, continually questioning, analyzing, and reformulating ideas. Such engagement nurtures a sense of ownership over learning outcomes, which increases intrinsic motivation. In contrast, traditional lecture-based instruction often confines students to repetitive exercises, limiting opportunities for creative thought and independent reasoning [

79].

The collaborative dimension of PBL further enhances its educational value. Through group discussions and cooperative inquiry, students are exposed to multiple perspectives and reasoning styles. This social interaction is essential in mathematics education, where reasoning, argumentation, and justification play central roles. Students learn to articulate their thoughts clearly, respond to counterarguments, and refine their reasoning based on peer feedback—all of which strengthen mathematical communication skills.

Additionally, the problem-solving orientation of PBL compels learners to connect mathematical theory with practice. Real-world problems often require synthesizing information across various topics, pushing students to apply mathematical reasoning flexibly. This transfer of knowledge fosters metacognitive awareness, as students must evaluate strategies, monitor progress, and adjust their approaches dynamically. Such experiences contribute to building self-regulated learners who are capable of tackling novel mathematical challenges with confidence [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73].

The results also highlight that the PBL model promotes critical thinking and creativity, two skills that are indispensable in 21st-century education. Students are challenged to identify patterns, formulate hypotheses, and evaluate solutions through logical reasoning. Unlike traditional models, where teachers dictate fixed procedures, PBL allows room for divergent thinking—encouraging students to explore multiple pathways to a solution. This intellectual freedom enhances both fluency and flexibility, key indicators of mathematical proficiency.

Another crucial aspect of PBL’s success lies in the role of the teacher as a facilitator rather than a transmitter of knowledge. Teachers guide inquiry through questioning, scaffolding, and feedback, helping students navigate the complexity of mathematical problems without dictating solutions. This shift in pedagogical role creates a more interactive and responsive classroom climate, aligning with constructivist theories of learning where understanding is co-constructed through dialogue and reflection [

45,

49].

In terms of affective outcomes, the implementation of PBL also contributes to increased student motivation and engagement. When learners perceive relevance between mathematical tasks and real-life applications, they are more likely to invest effort and persist through challenges. The sense of accomplishment derived from collaboratively solving problems reinforces their confidence and positive attitudes toward mathematics. This motivational gain is a key factor in sustaining long-term academic interest and performance [

50].

Furthermore, the study’s findings corroborate existing literature emphasizing that PBL enhances communication competence in mathematics. Through sustained practice in articulating reasoning both orally and in written form, students refine their ability to express complex mathematical ideas clearly and coherently. This aligns with global educational goals that regard communication as a foundational competency alongside reasoning and problem-solving [

23].

The pedagogical implications of these findings are profound. Integrating PBL into the mathematics curriculum can transform the learning experience from mechanical computation to meaningful inquiry and collaboration. Educators are encouraged to design problem scenarios that reflect authentic mathematical contexts, stimulate discussion, and require justification of reasoning. Such tasks not only strengthen students’ conceptual understanding but also prepare them for higher-order cognitive demands in advanced mathematics and beyond.

This study reinforces the notion that Problem-Based Learning is a powerful pedagogical approach capable of simultaneously developing students’ cognitive, metacognitive, and affective capacities. By engaging learners in authentic problem-solving, promoting communication, and fostering collaboration, PBL bridges the gap between mathematical theory and application. Its implementation can therefore serve as an effective strategy for cultivating competent, confident, and communicative learners in mathematics education.

Furthermore, statistical analysis using an independent samples t-test revealed that the difference between the two posttest mean scores was significant at p < 0.05, confirming the positive effect of the PBL model. The N-gain analysis supported this result, showing a moderate improvement for the control class (0.44) and a higher moderate category for the experimental class (0.54).

Overall, the findings suggest that the Problem-Based Learning model is effective in improving both mathematical communication ability and learning motivation. This improvement stems from the model’s emphasis on contextual problem-solving, where students are required to interpret problems, construct mathematical models, and communicate their reasoning clearly—skills that are essential for deeper mathematical understanding.

Figure 1.

Pretest and Posttest Scores.

Figure 1.

Pretest and Posttest Scores.

The t-test analysis indicated that p < 0.05, signifying a significant difference between the learning outcomes of the control and experimental classes. The N-gain analysis revealed a moderate category for both groups—0.44 for the control and 0.54 for the experimental class—though the experimental group showed higher improvement.

Based on the results presented in

Table 1, it is evident that the experimental class, which implemented the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) model, demonstrated a much greater improvement in learning outcomes compared to the control class. The mean pretest and posttest scores for the experimental group increased from 46.73 to 83.04, while the control group only rose slightly from 47.58 to 50.00. The t-test results (p < 0.05) confirm that this difference is statistically significant. Additionally, the N-gain score for the experimental group (0.54) indicates a higher level of improvement than that of the control group (0.44), emphasizing the superior effectiveness of PBL in enhancing students’ mathematical communication skills.

The results presented in

Table 1 reveal a substantial improvement in the academic performance of students who participated in the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) intervention compared to those taught using conventional methods. The experimental group’s mean score increased markedly from 46.73 to 83.04, reflecting a significant enhancement in both understanding and application of mathematical concepts. In contrast, the control group displayed only a minimal gain, rising from 47.58 to 50.00, which suggests that traditional teaching approaches were less effective in stimulating conceptual growth and learner engagement.

The findings from the t-test analysis (p < 0.05) further substantiate that the difference in posttest scores between the two groups is statistically significant. This confirms that the PBL model contributes meaningfully to the observed learning gains rather than the result being due to random variation. The statistical validation strengthens the argument that structured problem-solving environments foster a measurable improvement in mathematical competence and communication.

Furthermore, the N-gain analysis provides additional insight into the degree of learning improvement. The experimental class achieved an N-gain score of 0.54, which falls into the medium-to-high category, while the control class recorded 0.44, classified as moderate. Although both groups exhibited progress, the higher N-gain value for the experimental class underscores the superior learning efficiency of the PBL model. This indicates that PBL not only improves outcomes but also optimizes the rate and depth of student learning within a limited instructional period.

The higher effectiveness of PBL can be attributed to its learner-centered structure, where students actively participate in defining problems, hypothesizing solutions, and collaboratively exploring mathematical reasoning. This pedagogical shift transforms students from passive recipients of knowledge into active problem-solvers and critical thinkers. Through engagement with contextualized problems, students develop an integrated understanding of mathematical relationships, improving both retention and transfer of knowledge [

78,

79,

80,

81].

The higher effectiveness of Problem-Based Learning (PBL) can be primarily attributed to its learner-centered structure, which encourages students to assume responsibility for their own learning through active engagement with complex and authentic problems. Rather than relying on teacher-directed transmission of knowledge, PBL positions learners as co-constructors of understanding, guided by inquiry and reflection. This transition from a teacher-centered paradigm to a student-centered one reflects a fundamental epistemological shift from rote learning toward conceptual and experiential understanding. Students collaboratively define problems, generate hypotheses, and apply mathematical reasoning to test possible solutions, thereby cultivating analytical and metacognitive skills. In this process, knowledge is not merely acquired but constructed through exploration, negotiation, and application in meaningful contexts. This constructivist orientation ensures that students develop deeper and more durable conceptual frameworks, enhancing both retention and transfer of mathematical knowledge. Moreover, by engaging in discourse and peer review, learners refine their ability to communicate mathematical ideas clearly and persuasively. Consequently, PBL fosters intellectual autonomy, critical inquiry, and reflective reasoning—key attributes of higher-order mathematical cognition [

80,

81,

82,

83,

84].

From a theoretical perspective, the effectiveness of PBL is deeply anchored in

constructivist learning theory, particularly as articulated by Jean Piaget and Jerome Bruner. According to Piaget, learning occurs when individuals actively construct meaning through interaction with their environment, leading to cognitive restructuring and equilibration. PBL operationalizes this theory by exposing students to problems that create cognitive conflict, compelling them to adapt their existing mental models to accommodate new information. Similarly, Bruner’s concept of discovery learning emphasizes the importance of learners’ active engagement in hypothesis formulation and testing—processes central to the PBL framework. In mathematics education, this constructivist grounding encourages students to move beyond procedural fluency toward conceptual depth, connecting abstract symbols with tangible representations. Furthermore, PBL’s recursive cycle of problem identification, exploration, and reflection mirrors the mathematical problem-solving process itself, aligning pedagogical design with disciplinary epistemology. Through this alignment, students experience mathematics not as a static body of facts but as a dynamic system of reasoning and investigation [

81].

In addition to constructivism,

Vygotsky’s socio-cultural theory provides a crucial foundation for understanding the collaborative dimension of PBL. Learning, according to Vygotsky, is inherently social and occurs within the “zone of proximal development” (ZPD), where individuals achieve higher levels of understanding through interaction with more capable peers or facilitators. PBL environments embody this principle by structuring tasks that necessitate cooperative dialogue, joint problem solving, and peer feedback. Through such interactions, students internalize mathematical discourse and adopt expert-like reasoning patterns. The teacher’s role transforms into that of a facilitator who scaffolds inquiry and gradually transfers responsibility to the learner. This social mediation enriches the cognitive process, enabling students to articulate, justify, and refine their mathematical thinking in response to diverse perspectives. As a result, knowledge becomes socially constructed and dialogically validated, reinforcing the communal and communicative nature of mathematical understanding [

82].

A further explanation of PBL’s effectiveness can be drawn from

metacognitive theory, which emphasizes awareness and regulation of one’s own thinking processes. Within PBL, students are required to plan, monitor, and evaluate their reasoning strategies as they navigate complex mathematical problems. This metacognitive engagement fosters self-reflection, strategic flexibility, and adaptive expertise—competencies essential for effective problem solving. Research between 2021 and 2024 indicates that students exposed to metacognitively rich PBL environments demonstrate superior abilities to articulate reasoning steps, identify errors, and adjust strategies accordingly. Such metacognitive development not only enhances academic performance but also builds self-confidence and resilience in confronting mathematical challenges. Moreover, the reflective discussions embedded in PBL tutorials serve as natural metacognitive scaffolds, allowing learners to externalize and refine their thought processes. Therefore, the model aligns closely with contemporary educational goals emphasizing self-regulated and lifelong learning [

83,

84,

85,

86].

Complementary to these cognitive and social frameworks,

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) by Deci and Ryan offers a motivational explanation for the success of PBL. SDT posits that intrinsic motivation flourishes when learners’ needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are satisfied. PBL inherently supports these psychological needs by granting students autonomy in exploring problems, providing opportunities to demonstrate competence through discovery, and fostering relatedness through teamwork. Empirical evidence from mathematics classrooms (2020–2025) shows that learners in PBL settings exhibit higher levels of intrinsic motivation, engagement, and persistence compared to those in traditional settings. The sense of ownership generated through self-directed inquiry transforms motivation from extrinsic to intrinsic, thereby sustaining learning beyond formal assessments. Additionally, collaborative learning within PBL promotes emotional connection and peer support, which buffer against anxiety and enhance persistence. In sum, SDT elucidates how the structural design of PBL meets fundamental motivational drivers, leading to sustained and meaningful mathematical engagement [

84].

PBL also aligns with

Cognitive Apprenticeship Theory, which emphasizes learning through guided participation in authentic tasks. Within mathematics education, this involves modeling expert reasoning, providing scaffolded support, and gradually fading assistance as learners gain competence. In PBL contexts, teachers act as cognitive coaches who demonstrate problem-solving approaches, prompt reflective questioning, and encourage articulation of reasoning. Students, in turn, learn to apply heuristic strategies—such as abstraction, generalization, and verification—that characterize expert mathematical thinking. The iterative dialogue between teacher and learner simulates authentic problem-solving practices found in professional mathematical inquiry. This apprenticeship-based interaction strengthens the transferability of knowledge from classroom learning to real-world applications. Moreover, it ensures that students not only understand mathematical procedures but also grasp the underlying principles guiding their use. Consequently, PBL nurtures a deep, procedural, and conceptual mastery essential for mathematical literacy and innovation [

85].

Recent empirical investigations have reinforced these theoretical insights, providing robust evidence of PBL’s positive impact on students’ cognitive and communicative competencies in mathematics. Studies conducted across Asian and European contexts between 2021 and 2025 report that PBL significantly improves mathematical reasoning, creative thinking, and communication skills. Students participating in PBL activities demonstrate greater proficiency in articulating problem-solving processes, justifying solutions, and evaluating alternative approaches. Quantitative analyses further indicate gains in retention and transfer, suggesting that PBL enhances long-term conceptual understanding. Qualitative observations reveal improved classroom dynamics, with students assuming active leadership roles in collaborative discussions. These findings collectively validate the theoretical claims of constructivist and socio-cultural perspectives, confirming that meaningful learning emerges through interaction, reflection, and autonomy. The convergence of theory and evidence underscores PBL’s status as an empirically grounded model of effective mathematics instruction [

86].

The superior effectiveness of Problem-Based Learning in mathematics education is the result of its robust theoretical integration and empirical validation. Drawing from constructivism, socio-cultural theory, metacognition, self-determination, and cognitive apprenticeship, PBL offers a holistic framework that addresses cognitive, social, and motivational dimensions of learning. It transforms students into active thinkers, reflective learners, and collaborative problem solvers capable of applying mathematical knowledge flexibly in diverse contexts. The learner-centered nature of PBL not only promotes deeper understanding but also cultivates enduring dispositions such as curiosity, persistence, and intellectual independence. As global educational reforms increasingly prioritize higher-order thinking and communication competencies, PBL stands as a pedagogical model that aligns theory with practice and evidence with innovation. Future research should continue refining its implementation across varied mathematical domains and cultural settings, ensuring that the principles of active inquiry and collaboration remain central to 21st-century mathematics education [

87].

Another important factor contributing to the experimental group’s superior performance is the interactive and collaborative learning environment fostered by PBL. Group problem-solving encourages dialogue, negotiation, and peer feedback—processes that are essential for developing mathematical communication skills. Students learn to articulate their reasoning, justify their solutions, and respond to alternative viewpoints, thereby enhancing both their conceptual clarity and communicative precision [

88].

In contrast, the control group’s relatively stagnant performance highlights the limitations of conventional instruction, which often prioritizes procedural mastery over conceptual understanding. Traditional teaching tends to emphasize teacher explanations and repetitive practice, which may hinder students from developing flexible reasoning or confidence in expressing mathematical ideas. This difference aligns with the constructivist view that knowledge construction is most effective when learners are actively involved in meaning-making processes.

The improvement observed in the experimental group also reflects the motivational dimension of PBL. When students engage with real-life mathematical scenarios, they perceive learning as more relevant and purposeful. This relevance increases intrinsic motivation, persistence, and willingness to tackle complex problems—factors that contribute significantly to academic success. Motivation, in turn, reinforces learning outcomes by sustaining cognitive engagement throughout the problem-solving process [

89].

Additionally, the structured yet open-ended nature of PBL promotes the development of higher-order thinking skills, such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Students must identify what they know, determine what they need to learn, and devise strategies to reach solutions. These processes not only enhance problem-solving proficiency but also foster metacognitive awareness, enabling learners to monitor and regulate their own thinking.

From a pedagogical perspective, the study’s results support the integration of PBL into mathematics instruction as a means of improving both cognitive and affective learning outcomes. Teachers adopting this model are encouraged to design problems that are authentic, complex, and multidisciplinary, thereby allowing students to apply mathematical reasoning in diverse contexts. Such implementation nurtures transferable skills that are vital for academic and real-world problem-solving [

90].

The empirical evidence from this study demonstrates that Problem-Based Learning significantly outperforms conventional instruction in promoting students’ mathematical communication skills, conceptual understanding, and learning motivation. The combination of statistical significance (p < 0.05), higher N-gain scores, and observed behavioral engagement affirms the pedagogical robustness of PBL. Thus, adopting PBL in mathematics classrooms can serve as an effective strategy to cultivate critical, communicative, and confident learners capable of applying mathematics meaningfully across contexts.

The implementation of the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) model in mathematics instruction has proven to exert a positive influence on improving students’ mathematical communication and learning motivation [

27,

28]. This model positions students as active participants in the learning process by engaging them in contextual problem-solving activities that require collaboration [

29,

31], critical thinking [

30,

33], and the expression of ideas both verbally and in writing [

32,

34]. Consequently, PBL fosters a meaningful learning environment, where students not only grasp mathematical concepts procedurally but also learn to explain and connect them to real-world contexts.

The implementation of the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) model in mathematics instruction has been consistently demonstrated to exert a positive and measurable impact on students’ learning outcomes, particularly in the domains of mathematical communication and learning motivation [

27,

28,

35]. Within the framework of PBL, learners engage in authentic, context-based problem scenarios that compel them to apply theoretical knowledge to practical situations. Such a process bridges the gap between abstract mathematical theory and its real-world applications, thereby deepening students’ conceptual understanding and strengthening cognitive engagement throughout the learning process [

27,

36].

A distinguishing characteristic of PBL is its emphasis on student-centered learning, where students take an active role in constructing knowledge through inquiry, exploration, and reflection [

28]. Rather than relying on direct instruction, the PBL approach encourages learners to formulate hypotheses, test ideas, and collaboratively evaluate solutions. This pedagogical orientation fosters autonomous learning behavior, enabling students to regulate their own learning strategies and develop a sense of academic ownership over problem-solving tasks [

29].

The collaborative nature of PBL plays a crucial role in enhancing mathematical communication among learners [

29,

31,

37]. Through group discussions, students articulate their reasoning, negotiate meanings, and collectively refine mathematical arguments. These interactions serve as a platform for exchanging diverse perspectives, promoting mutual understanding, and cultivating discourse competence—a key indicator of communicative mathematical proficiency [

31,

38]. In this sense, collaboration acts not merely as a social process but as an epistemic tool for constructing shared mathematical understanding.

In addition to collaboration, the PBL framework strongly stimulates the development of critical thinking skills [

30,

33,

38]. Students are challenged to identify essential information, evaluate assumptions, and design strategies to solve unfamiliar problems. The cognitive demand of such activities promotes analytical reasoning and adaptive thinking, which are fundamental for mathematical literacy in contemporary education [

33]. As students engage in critical inquiry, they move beyond procedural computation toward a more conceptual and reflective form of understanding mathematics.

Equally important, PBL enhances the expression of mathematical ideas through both verbal and written communication [

32,

34]. In the course of discussing and documenting problem-solving processes, students learn to express complex mathematical relationships coherently and logically. This dual modality of communication reinforces conceptual retention, as the act of verbalizing and writing mathematical explanations consolidates internal understanding while enabling the external representation of thought [

32].

By situating learning within contextual and meaningful problem settings, PBL transforms mathematics classrooms into environments of experiential learning [

30]. Students engage in problems that mirror real-world phenomena—budgeting, measurements, data analysis, and modeling—thereby perceiving mathematics as a living discipline rather than a set of abstract symbols. This contextual relevance enhances intrinsic motivation, as students recognize the practical utility of mathematical thinking beyond academic boundaries [

29,

31,

39].

Moreover, PBL effectively integrates collaboration, communication, and critical reasoning into a unified learning framework. This holistic integration aligns with 21st-century learning competencies, which emphasize creativity, communication, collaboration, and critical thinking—the so-called “4Cs” of modern education [

33,

45,

46]]. By embedding these competencies in mathematics instruction, PBL prepares learners to navigate complex challenges in academic and professional settings that demand interdisciplinary and problem-oriented thinking [

27].

From a psychological perspective, the PBL environment nurtures self-efficacy and persistence in learning. When students successfully navigate complex problem tasks, they experience a sense of achievement that reinforces their confidence and motivation [

28,

30,

39]. This positive feedback loop encourages sustained engagement with mathematical challenges, fostering resilience and perseverance in the face of difficulty—traits essential for long-term academic growth and success[

47,

48,

49].

Furthermore, teachers in PBL classrooms act as facilitators of inquiry rather than transmitters of information [

31,

33]. Their role is to scaffold learning, pose guiding questions, and provide constructive feedback, thereby supporting the gradual development of student autonomy. This pedagogical shift reflects the constructivist principle that knowledge is co-constructed through active engagement rather than passively received from authority figures [

34,

40]. Such facilitation ensures that all learners remain actively involved and intellectually challenged.

In conclusion, the integration of the Problem-Based Learning model in mathematics education fosters a dynamic and meaningful learning experience where students learn to think, communicate, and apply mathematics in contextually relevant ways [

27,

28,

33]. Through collaboration [

29,

31], critical reflection [

30,

33], and expressive articulation [

32,

34], PBL empowers learners to transcend procedural knowledge and engage in genuine mathematical reasoning. Consequently, PBL emerges as a powerful pedagogical approach capable of developing students’ communication competence, critical inquiry, and intrinsic motivation—cornerstones of high-quality mathematics education [

41,

42,

43,

44].

Overall, the effectiveness of the PBL model is reflected not only in improved learning outcomes but also in enhanced learning motivation. Through group-based problem-solving activities, students become more actively involved, articulate their opinions, and listen to their peers’ ideas [

35,

36]. These interactions strengthen their self-confidence and mathematical communication abilities [

37,

38]. Thus, PBL can be considered an effective instructional strategy for fostering critical thinking, mathematical communication, and learning motivation in mathematics classrooms.

These findings are consistent with the results of Afifah et al. [

8] and Rahmalia et al. [

10], who confirmed that PBL improves students’ conceptual understanding and mathematical communication skills. PBL provides students with opportunities to engage in discussions [

39,

40], express their ideas [

41,

42], and explore problem solutions collaboratively, which in turn enhances learning motivation [

11,

39,

40].