Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

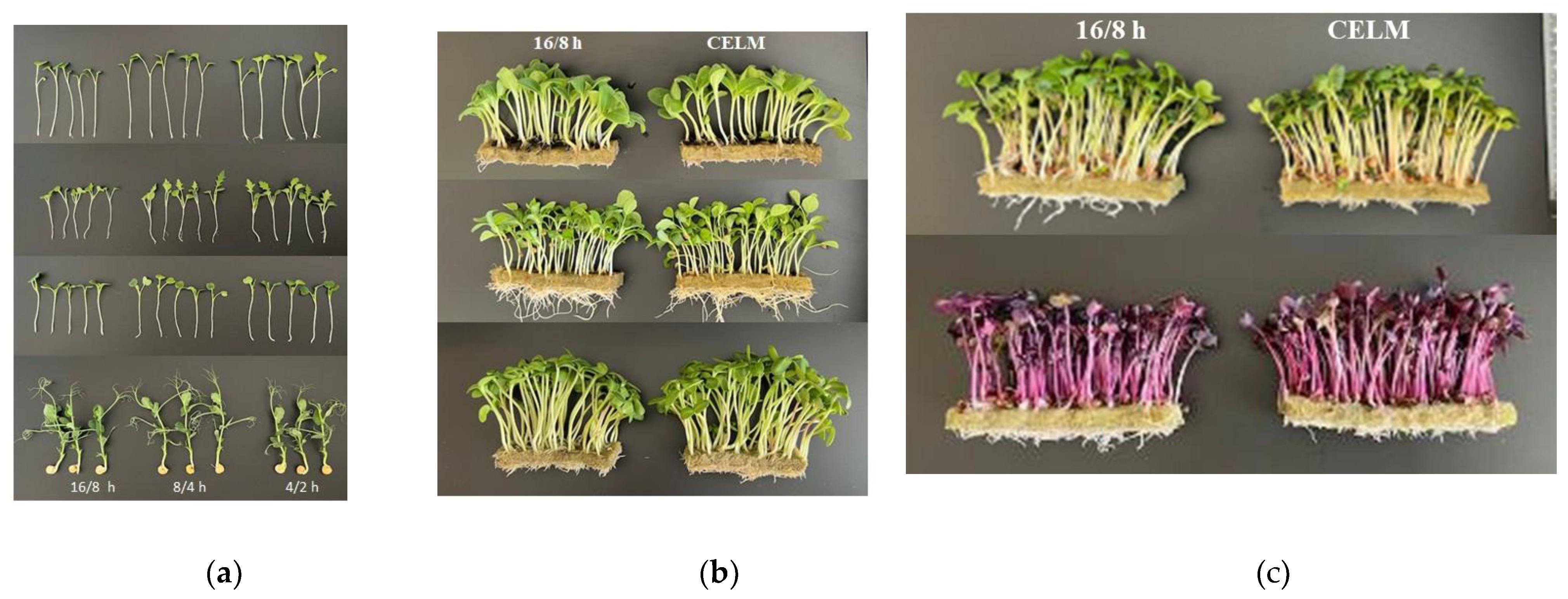

2.1. Plant Responses to Shortened Light/Dark Cycles 8/4 h and 4/2 h

2.2. Plant Responses to the Cost-Effective Lighting Mode (CELM)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

4.2. Light treatments

4.3. Growth and Yield Measurements

4.4. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Measurements

4.5. Measurement of Relative Electrolyte Leakage (REL)

4.6. Photosynthetic Pigment Content

4.7. Anthocyanins and Flavonoids Content

4.8. Malodialdehyde (MDA) Content

4.9. Hydrogen Peroxidase Content.

4.10. Proline Content

4.11. Antioxidative Enzyme Activity Assays

4.12. Soluble Sugar Content

4.13. Ascorbic Acid Content

4.14. Estimating Lighting Electricity Cost

4.15. Data Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAT | Catalase |

| CELM | Cost-effective lighting mode |

| DLI | Daily light integral |

| DW | Dry weight |

| FW | Fresh weight |

| GPX | Guaiacol peroxidase |

| L/D | Light/dark |

| LMA | Leaf mass per area |

| PFAL | Plant factory with artificial lighting |

| REL | Relative electrolyte leakage |

| RI | Robustness index |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Parameter | Light-dark cycle, h | ||

| 16/8 | 8/4 | 4/2 | |

| Borago | |||

| Anthocyanins, (А530 – 0.25А657) g-1FW | 0.46±0.02 a | 0.46±0.03 a | 0.41±2.72 a |

| Flavonoids, А300 g-1FW | 19.76±0.02 a | 18.77±1.40 a | 20.96±2.10 a |

| Proline, µmol g-1 DW | 114.4±3.3 a | 106.3±3.3 a | 112.2±7.1 a |

| Ascorbic acid, mg g-1FW | 96.9±8.5 a | 97.8±12.4 a | 110.4±15.0 a |

| Fenugreek | |||

| Anthocyanins, (А530 – 0.25А657) g-1FW | 0.55±0.08 a | 0.48±0.02 a | 0.47±0.03 a |

| Flavonoids, А300 g-1FW | 13.23±1.82 a | 12.16±1.76 a | 10.06±8.26 a |

| Proline, µmol g-1 DW | 205.6±10.2 a | 243.5±14.6 a | 207.1±4.0 a |

| Ascorbic acid, mg g-1FW | 92.9±5.0 a | 87.2±10.7 a | 82.6±1.6 a |

| Pea | |||

| Anthocyanins, (А530 – 0.25А657) g-1FW | 0.57±0.10 a | 0.50±0.06 a | 0.55±0.10 a |

| Flavonoids, А300 g-1 | 27.04±3.91 a | 25.40±2.17 a | 21.88±1.65 a |

| Proline, µmol g-1 DW | 918±28 a | 939±48 a | 874±15 a |

| Parameter | Light-dark cycle, h | ||

| 16/8 | 8/4 | 4/2 | |

| Arugula | |||

| Anthocyanins, (А530 – 0.25А657) g-1FW | 0.42±0.06 a | 0.52±0.04 a | 0.51±0.04 a |

| Flavonoids, А300 g-1FW | 16.44±0.89 a | 19.69±0.61 a | 17.33±0.77 a |

| Proline, µmol g-1 DW | 523±17 a | 534±29 a | 553±11 a |

| Broccoli | |||

| Anthocyanins, (А530 – 0.25А657) g-1FW | 0.59±0.03 a | 0.63±0.04 a | 0.51±0.03 a |

| Flavonoids, А300 g-1FW | 6.35±0.47 a | 5.07±1.02 a | 3.14±0.12 b |

| Proline, µmol g-1 DW | 620±25 b | 604±27 b | 761±20 a |

| Mizuna | |||

| Anthocyanins, (А530 – 0.25А657) g-1FW | 0.33±0.02 b | 0.41±0.02 a | 0.32±0.05 b |

| Flavonoids, А300 g-1FW | 11.12±2.35 a | 11.10±2.02 a | 5.37±0.49 b |

| Proline, µmol g-1 DW | 597±10 b | 574±16 b | 669±50 a |

References

- Liu, X.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Z.; He, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q. Innovative Application Strategies of Light-Emitting Diodes in Protected Horticulture. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avgoustaki, D.D.; Xydis, G. Energy cost reduction by shifting electricity demand in indoor vertical farms with artificial lighting. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 211, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graamans, L.; Tenpierik, M.; van den Dobbelsteen, A.; Stanghellini, C. Plant factories: Reducing energy demand at high internal heat loads through façade design. Appl. Energy 2020, 262, 114544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, N.; Krarti, M. Review of Energy Efficiency in Controlled Environment Agriculture. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 141, 110786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, T.; Yang, A.; Hamm, M.W. Ebergy Optimisation of Plant Factories and Greenhouses for Different Climate Conditions. Energy Conservation and Management 2021, 243, 114336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, R.; Wu, B.; Macpherson, S.; Lefsrud, M. How the distribution of photon delivery impacts crops in indoor plant environments: A review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, M.; Ito, T.; Maruo, T.; Suzuki, K.; Matsuo, K. Plant growth and physiological characters of lettuce plants grown under artificial light of different irradiating cycles. Environ. Control Biol. 1995, 33, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Sugumaran, K.; Atulba, S.L.S.; Jeong, B.R.; Hwang, S.J. Light intensity and photoperiod influence the growth and development of hydroponically grown leaf lettuce in a closed-type plant factory system. Hort. Environ. Biotechnol. 2013, 54, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, T.; Lu, N.; Takagaki, M.; Mao, H. Leaf area model based on thermal effectiveness and photosynthetically active radiation in lettuce grown in mini-plant factories under different light cycles. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 252, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, J.Z.; Hang, T.; Li, P.P. Photosynthetic characteristics and growth performance of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) under different light/dark cycles in mini plant factories. Photosynthetica 2020, 58, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, Q. Effects of intermittent light exposure with red and blue light emitting diodes on growth and carbohydrate accumulation of lettuce. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 234, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengasamy, N.; Othman, R.Y.; Che, H.S.; Harikrishna, J.A. Artificial lighting photoperiod manipulation approach to improve productivity and energy use efficacies of plant factory cultivated Stevia rebaudiana. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.H. Effect of photoperiod shortening on the nutrient uptake and carbon metabolism of tomato and hot pepper seedlings grown hydroponically. J. Bio-Environ. Control. 2003, 12, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Shibaeva, T.G.; Mamaev, A.V.; Sherudilo, E.G.; Ikkonen, E.N.; Titov, A.F. Responses of Tomato and Eggplant to Abnormal Light/Dark Cycles and Continuous Lighting. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2024. 71, 12. [CrossRef]

- García-Caparrós, P.; Sabio, F.; Barbero, F.J.; Chica, R.M.; Lao, M.T. Physiological responses of tomato and cucumber seedlings under different light–dark cycles. Agronomy 2020, 10, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, H.; Mochizuki, A.; Okuda, N.; Seki, M.; Furusaki, S. Intermittent light irradiation with second-or hour-scale periods controls anthocyanin production by strawberry cells. Enzyme. Microb. Technol. 2000, 26, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, G.; Heo, J.W.; Kozai, T.; Paek, K.Y. Effect of continuous or intermittent radiation on sweet potato plantlets in vitro. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2006, 81, 546–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibaeva, T.; Rubaeva, А.; Sherudilo, E.; Ikkonen, E.; Titov, A. The effect of shortened light/dark cycles on growth, yield and nutritional value of pea shoots. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems 2024, 1130. [Google Scholar]

- Urairi, C.; Shimizu, H.; Nakashima, H.; Miyasaka, J.; Ohdoi, K. Optimization of Light-Dark Cycles of Lactuca sativa L. in Plant Factory. Environ. Control Biol. 2017, 55, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, A.N.; Salathia, N.; Hall, A.; Kevei, E.; Toth, R.; Nagy, F.; Hibberd, J.M.; Millar, A.J.; Webb, A.A. Plant circadian clocks increase photosynthesis, growth, survival, and competitive advantage. Science 2005, 309, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, H.; Ukai, K.; Oyama, T. Self-arrangement of cellular circadian rhythms through phase-resetting in plant roots. Phys. Rev. E 2012, 86, 41917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, M.; Liu, W.; Zha, L.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B. Altering light-dark cycle at pre-harvest stage regulated growth, nutritional quality, and photosynthetic pigment content of hydroponic lettuce. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2021, 43, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-L.; Li, Y.-L.; Wang, L.-C.; Yang, Q.-C.; Guo, W.-Z. Responses of butter leaf lettuce to mixed red and blue light with extended light/dark cycle period. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibaeva, T.G.; Titov, A.F. Photoperiod Stress in Plants: A New Look at Plant Response to Abnormal Light-Dark Cycles. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2025, 72, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.; Cortleven, A.; Novak, O.; Schmulling, T. Root-derived trans-zeatin cytokinin protects Arabidopsis plants against photoperiod stress. Plant, Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 2637–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeber, V.M.; Bajaj, I.; Rohde, M.; Schmulling, T.; Cortleven, A. Light acts as a stressor and influences abiotic and biotic stress responses in plants. Plant, Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeber, V.M.; Schmulling, T.; Cortleven, A. The Photoperiod: Handling and Causing Stress in Plants, Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibaeva, T.G.; Sherudilo, E.G.; Ikkonen, E.; Rubaeva, A.A.; Levkin, I.A.; Titov, A.F. Effects of Extended Light/Dark Cycles on Solanaceae Plants. Plants 2024, 13, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibaeva, T.G.; Mamaev, A.V.; Titov, A.F. Possible Physiological Mechanisms of Leaf Photodamage in Plants Grown under Continuous Lighting. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 70, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuelsoud, W.; Cortleven, A.; and Schmulling, T. Photoperiod stress induces an oxidative burst-like response and is associated with increased apoplastic peroxidase and decreased catalase activities. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasensky-Wrzaczek, J.; Kangasjarvi, J. The role of reactive oxygen species in the integration of temperature and light signals. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3347–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuolienė, G.; Brazaitytė, A.; Jankauskienė, J.; Viršilė, A.; Sirtautas, R.; Novičkovas, A.; Sakalauskienė, S.; Sakalauskaitė, J.; Duchovskis, P. LED irradiance level affects growth and nutritional quality of Brassica microgreens. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2013, 8, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.-H.; Cheng, R.-F.; Yang, Q.-C.; Wang, J.; Lu, Ch. ; Continuous light from red, blue, and green light-emitting diodes reduces nitrate content and enhances phytochemical concentrations and antioxidant capacity in lettuce. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2016, 141, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zha, L.; Zhang, Yu. Growth and nutrient element content of hydroponic lettuce are modified by LED continuous lighting of different intensities and spectral qualities. Agronomy 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti, S.; Moscatello, S.; Riccio, F.; Downey, P.; Battistelli, A. Continuous lighting promotes plant growth, light conversion efficiency, and nutritional quality of Eruca vesicaria (L.) Cav. in controlled environment with minor effects due to light quality. Front. Plant Sci., 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibaeva, T.G.; Sherudilo, E.G.; Rubaeva, A.A.; Titov, A.F. Continuous LED lighting enhances yield and nutritional value of four genotypes of Brassicaceae microgreens. Plants 2022, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibaeva, T.G.; Rubaeva, A.A.; Sherudilo, E.G.; Titov, A.F. Continuous lighting increases yield and nutritional value and decreases nitrate content in Brassicaceae microgreens. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, S.; Cortleven, A.; Iven, T.; Feussner, I.; Havaux, M.; Riefler, M.; Schmulling, T. Circadian stress regimes affect the circadian clock and cause jasmonic acid-dependent cell death in cytokinin-deficient Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigment of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 1987, 148, 350–382. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Xing, T.; Wang, X. The role of light in the regulation of anthocyanin accumulation in Gerbera hybrid. Plant Growth Regul. 2004, 44, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogues, S.; Backer, N.R. Effect of drought on photosynthesis in Mediterranean plants under UV-B radiation. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Baroowa, B.; Gogoi, N. Biochemical changes in two Vigna spp. during drought and subsequent recovery. Ind. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 18, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolupaev, Y.E.; Fisova, E.N.; Yastreb, T.O.; Ryabchun, N.I.; Kirichenko, V.V. Effect of hydrogen sulfide donor on antioxidant state of wheat plants and their resistance to soil drought. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 66, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.L.; Packer, L. Photoperioxidation in isolated chloroplasts I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968, 125, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, V.; Yordanov, I.; Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant system in acid rain-treated bean plants: protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 2000, 151, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Merhods Enzymol. 1984, 105, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S.K. Superoxide dismutases: I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehly, A.C.; Chance, B. The assay catalases and peroxidases. In Methods of Biochemical Analysis; Glick, D., Ed.; Interscience Pub., New York, 1954, 1, 357–424. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunjal, M.; Singh, J.; Kaur, J.; Kaur, S.; Nanda, V.; Mehta, C.M.; Bhadariya, V.; Rasane, P. Comparative analysis of morphological, nutritional, and bioactive properties of selected microgreens in alternative growing medium. South African J. Bot. 2024, 165, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Light-dark cycle, h | ||

| 16/8 | 8/4 | 4/2 | |

| Borago | |||

| Yield, g FW dm-2 | 28.2±1.8 a | 28.8±3.2 a | 30.0±1.3 a |

| LMA, mg DW cm-2 | 2.26±0.11 b | 2.62±0.15 a | 2.43±0.04 a |

| Dry matter content, g kg-1 | 63.3±2.6 a | 67.2±2.8 a | 59.4±3.2 a |

| Fv/Fm | 0.831±0.002 a | 0.833±0.003 a | 0.830±0.003 a |

| Chl a+b, mg DW g-1 | 9.02±0.54 c | 10.76±0.70 b | 12.71±1.00 a |

| Carotenoids, mg DW g-1 | 1.26±0.09 a | 1.28±0.17 a | 1.03±0.27 a |

| REL, % | 16.05±0.23 a | 12.76±0.96 c | 14.91±0.37 b |

| MDA, µmol g-1 FW | 14.8±0.6 a | 16.2±1.0 a | 15.6±0.4 a |

| H2O2, µmol g-1 FW | 0.37±0.02 a | 0.40±0.01 a | 0.15±0.01 b |

| SOD, U mg-1 protein | 5.0±0.4 a | 4.2±0.6 a | 4.4±1.6 a |

| CAT, µmol/(mg protein min) | 31.5±1.4 a | 26.5±1.1 b | 23.4±1.9 b |

| GPX, µmol mg-1 protein min-1 | 5.1±0.6 b | 8.1±1.9 a | 8.8±1.8 a |

| Soluble sugars, mg g-1 DW | 250.4±4.9 c | 307.5±2.8 a | 276.9±8.1 b |

| Protein, mg g-1 FW | 168.4±4.1 b | 178.9±10.6 ab | 201.9±11.3 a |

| Fenugreek | |||

| Yield, g FW dm-2 | 24.6±0.8 a | 27.0±1.6 a | 24.9±2.0 a |

| LMA, mg DW cm-2 | 2.61±0.18 a | 2.49±0.10 a | 2.36±0.14 a |

| Dry matter content, g kg-1 | 92.6±0.3 a | 92.2±0.6 a | 92.8±0.2 a |

| Fv/Fm | 0.834±0.002 a | 0.829±0.010 a | 0.833±0.009 a |

| Chl a+b, mg DW g-1 | 10.62±0.94 b | 10.53±0.65 b | 13.01±1.01 a |

| Carotenoids, mg DW g-1 | 1.50±0.08 b | 1.83±0.14 a | 1.77±0.15 a |

| REL, % | 14.32±0.55 a | 14.96±0.50 a | 14.19±0.77 a |

| MDA, µmol g-1 FW | 18.6±0.7 a | 18.1±0.8 a | 17.8±0.9 a |

| H2O2, µmol g-1 FW | 0.87±0.13 a | 0.94±0.06 a | 0.78±0.07 a |

| SOD, U mg-1 protein | 6.7±0.4 a | 5.9±1.0 a | 5.4±1.3 a |

| CAT, µmol/(mg protein min) | 26.0±1.7 b | 34.2±1.8 a | 31.9±2.5 a |

| GPX, µmol mg-1 protein min-1 | 2585±102 a | 2347±143 a | 2101±131 a |

| Soluble sugars, mg g-1 DW | 288.5±36.4 b | 371.7±24.0 a | 361.9±6.6 a |

| Protein, mg g-1 FW | 213.7±10.6 a | 202.4±7.5 a | 241.1±19.2 a |

| Pea shoots | |||

| Shoot FW, g | 0.54±0.02 b | 0.65±0.02 a | 0.58±0.03 b |

| LMA, mg DW cm-2 | 1.68±0.08 a | 1.73±0.07 a | 1.56±0.06 a |

| Dry matter content, g kg-1 | 54.6±0.4 a | 60.5±0.6 a | 57.4±0.4 a |

| Fv/Fm | 0.790±0.002 a | 0.802±0.008 a | 0.799±0.008 a |

| Chl a+b, mg DW g-1 | 14.37±0.67 b | 16.40±1.23 a | 16.83±0.72 a |

| Carotenoids, mg DW g-1 | 1.82±0.10 a | 1.98±0.18 a | 1.99±0.12 a |

| MDA, µmol g-1 FW | 59.7±2.3 b | 61.6±2.6 b | 72.5±6.1 a |

| H2O2, µmol g-1 FW | 0.68±0.05 b | 0.85±0.09 a | 1.03±0.09 a |

| SOD, U mg-1 protein | 2.4±0.2 b | 3.5±0.1 a | 2.1±0.3 b |

| CAT, µmol/(mg protein min) | 21.2±1.9 b | 28.4±1.9 a | 24.8±2.7 a |

| GPX, µmol mg-1 protein min-1 | 498±68 b | 686±48 a | 718±62 a |

| Soluble sugars, mg g-1 DW | 320.9±11.4 a | 300.8±12.1 b | 300.2±14.6 b |

| Protein, mg g-1 FW | 36.0±2.1 a | 32.7±1.9 a | 34.6±1.2 a |

| Parameter | Light-dark cycle, h | ||

| 16/8 | 8/4 | 4/2 | |

| Arugula | |||

| Shoot FW, mg | 64.7±3.0 b | 77.4±3.0 a | 72.6±4.0 a |

| LMA, mg DW cm-2 | 1.83±0.07 b | 2.11±0.20 a | 2.07±0.05 a |

| Dry matter content, g kg-1 | 61.0±2.3 a | 57.0±2.6 a | 55.3±3.0 a |

| Robustness index | 10.2±0.5 a | 11.3±0.8 a | 10.5±0.6 a |

| Chl a+b, mg DW g-1 | 11.64±0.70 b | 16.43±0.29 a | 16.44±0.79 a |

| Carotenoids, mg DW g-1 | 1.33±0.04 b | 2.04±0.05 a | 1.90±0.10 a |

| MDA, µmol g-1 FW | 11.6±0.7 b | 14.4±1.4 a | 12.1±0.9 ab |

| H2O2, µmol g-1 FW | 0.65±0.03 a | 0.63±0.05 a | 0.60±0.04 a |

| SOD, U mg-1 protein | 2.8±0.2 a | 2.2±0.4 a | 2.4±0.6 a |

| CAT, µmol/(mg protein min) | 12.7±2.2 b | 17.2±1.9 a | 10.1±3.1 b |

| GPX, µmol mg-1 protein min-1 | 21.5±4.1 a | 17.9±3.2 a | 16.6±2.0 a |

| Soluble sugars, mg g-1 DW | 411.6±32.6 b | 521.8±18.9 a | 479.4±37.9 ab |

| Protein, mg g-1 FW | 21.8±1.5 b | 19.2±0.9 ab | 18.1±0.7 a |

| Broccoli | |||

| Shoot FW, g | 115.2±9.0 a | 114.9±7.0 a | 124.1±7.0 a |

| LMA, mg DW cm-2 | 1.87±0.05 b | 2.35±0.15 a | 1.83±0.04 b |

| Dry matter content, g kg-1 | 52.0±2.5 b | 59.0±2.2 a | 54.0±3.0 ab |

| Robustness index | 10.1±0.8 a | 9.7±0.7 a | 9.6±0.6 a |

| Chl a+b, mg DW g-1 | 12.68±0.69 a | 14.49±1.06 a | 12.84±1.25 a |

| Carotenoids, mg DW g-1 | 1.79±0.07 a | 1.68±0.07 a | 1.67±0.18 a |

| MDA, µmol g-1 FW | 19.6±3.3 a | 15.6±0.5 a | 15.1±0.7 a |

| H2O2, µmol g-1 FW | 0.66±0.06 a | 0.57±0.02 a | 0.63±0.14 a |

| SOD, U mg-1 protein | 4.9±0.9 a | 2.5±0.5 ab | 1.1±0.4 b |

| CAT, µmol/(mg protein min) | 22.5±3.5 a | 21.5±2.2 a | 17.7±1.4 b |

| GPX, µmol mg-1 protein min-1 | 108.9±13.4 a | 94.0±3.7 a | 99.3±7.9 a |

| Soluble sugars, mg g-1 DW | 292.3±19.2 b | 342.4±11.9 a | 296.3±22.2 b |

| Protein, mg g-1 FW | 18.8±1.6 а | 16.9±0.4 a | 16.3±1.3 a |

| Mizuna | |||

| Shoot FW, g | 75.0±4.0 a | 70.9±3.0 a | 72.2±4.0 a |

| LMA, mg DW cm-2 | 1.99±0.18 a | 1.91±0.10 a | 1.75±0.04 b |

| Dry matter content, g kg-1 | 53.1±2.4 a | 50.1±2.1 a | 51.0±2.5 a |

| Robustness index | 10.8±0.5 a | 9.8±0.7 a | 10.5±0.7 a |

| Chl a+b, mg DW g-1 | 11.83±0.39 a | 11.39±0.63 a | 10.27±0.48 b |

| Carotenoids, mg DW g-1 | 1.68±0.09 a | 1.47±0.12 a | 1.17±0.16 b |

| MDA, µmol g-1 FW | 18.6±1.1 b | 16.2±1.5 b | 25.1±2.1 a |

| H2O2, µmol g-1 FW | 0.47±0.03 c | 0.56±0.02 b | 1.14±0.06 a |

| SOD, U mg-1 protein | 6.8±0.5 a | 4.3±0.4 b | 5.9±0.2 ab |

| CAT, µmol/(mg protein min) | 26.0±8.3 a | 15.6±4.3 b | 10.6±1.2 b |

| GPX, µmol mg-1 protein min-1 | 148.6±16.0 a | 128.4±7.5 a | 195.6±15.0 a |

| Soluble sugars, mg g-1 DW | 438.1±22.6 b | 500.8±23.4 a | 293.9±18.0 b |

| Protein, mg g-1 FW | 16.7±0.7 b | 18.5±0.8 a | 14.7±0.3 c |

| Parameter | Lighting mode | Borago | Fenugreek | Sunflower |

Green radish |

Radish Sango |

| Yield, g FW dm-2 | 16/8 h CELM |

24.9±3.1 a 25.1±5.2 a |

14.6±0.7 a 16.0±0.8 a |

60.5±3.5 a 68.8±6.0 a |

27.2±1.7 a 25.1±3.7 a |

33.5±1.1 b 42.1±2.5 a |

| LMA, mg DW cm-2 | 16/8 h | 2.16±0.10 a | 2.17±0.10 a | 4.69±0.33 a | 4.3±0.3 a | 3.7±0.3 b |

| CELM | 2.38±0.17 a | 2.38±0.16 a | 4.74±0.31 a | 4.5±0.4 a | 4.7±0.3 a | |

| Dry matter content, | 16/8 h | 56.8±3.4 a | 77.2±4.1 a | 72.3±3.1 a | 92.1±2.3 a | 77.6±1.6 a |

| g kg-1 | CELM | 60.4±3.1 a | 78.3±3.6 a | 69.7±3.0 a | 91.6±2.5 a | 73.6±2.2 a |

| Fv/Fm | 16/8 h | 0.831±0.002 a | 0.836±0.001 a | 0.831±0.005 a | - | - |

| CELM | 0.833±0.002 a | 0.830±0.002 a | 0.833±0.006 a | - | - | |

| Chl a+b, mg g-1 DW | 16/8 h | 13.65±0.30 a | 10.16±1.03 a | 6.90±0.45 a | 9.8±0.5 a | 6.1±0.2 a |

| CELM | 12.40±0.49 a | 12.49±1.30 a | 5.79±0.70 a | 7.5±0.2 b | 6.1±0.3 a | |

| Carotenoids, mg g-1 DW |

16/8 h | 2.18±0.19 a | 1.44±0.22 a | 1.01±0.05 a | 1.0±0.1 a | 0.9±0.1 a |

| CELM | 1.98±0.12 a | 1.79±0.11 a | 1.01±0.14 a | 1.2±0.1 a | 0.8±0.1 a | |

| Anthocyanins, (А530 – 0.25А657) g-1FW | 16/8 h | 0.50±0.04 a | 0.68±0.03 a | 0.39±0.04 a | 0.7±0.1 a | 15.3±0.7 b |

| CELM | 0.47±0.03 a | 0.68±0.09 a | 0.35±0.03 a | 0.8±0.1 a | 21.2±1.0 a | |

| Flavonoids, А300 g -1FW |

16/8 h | 14.72±1.10 b | 14.59±1.36 a | 32.72±1.56 a | 23.2±3.2 a | 36.3±3.4 b |

| CELM | 15.76±0.64 a | 13.66±1.14 a | 30.02±3.82 a | 25.8±2.1 a | 44.0±2.3 a | |

| REL, % |

16/8 h CELM |

22.3±2.1 a 19.4±0.6 a |

25.4±5.9 a 25.5±6.1 a |

13.4±0.9 a 15.2±0.5 a |

18.8±0.8 a 17.5±1.2 a |

15.1±0.8 a 12.1±2.9 b |

| MDA, µmol g-1 FW |

16/8 h CELM |

14.5±0.6 b 19.3±1.6 a |

14.2±0.3 a 14.5±0.2 a |

28.5±1.2 a 28.6±1.3 a |

189±15 b 230±19 a |

482±67 a 487±70 a |

| H2O2, µmol g-1 FW |

16/8 h CELM |

0.67±0.08 a 0.68±0.07 a |

0.16±0.02 a 0.17±0 a |

1.41±0.12 a 1.28±0.11 a |

0.67±0.09 a 0.64±0.08 a |

1.38±0.07 a 1.29±0.05 a |

| SOD, U mg-1 protein | 16/8 h CELM |

5.2±0.8 a 4.3±1.9 a |

5.8±0.1 a 6.4±0.7 a |

3.3±0.3 b 5.9±0.2 a |

2.8±0.3 a 2.7±0.3 a |

2.0±0.4 a 1.9±0.1 a |

| CAT, µmol mg-1 protein min) | 16/8 h CELM |

25.1±1.1 a 22.6±0.7 b |

17.4±1.2 b 20.7±0.9 a |

13.3±1.6 a 14.6±0.4 a |

7.2±0.5 b 12.0±0.8 a |

10.1±1.1 b 16.4±2.2 a |

| GPX, µmol mg-1 protein min) | 16/8 h CELM |

17.7±1.6 b 28.7±2.2 a |

2119±203 a 2340±181 a |

53.5±12.5 b 119.8±8.9 a |

69.2±7.7 b 112.7±9.0 a |

37.1±4.6 b 47.6±4.9 a |

| Proline, µmol g-1 DW | 16/8 h CELM |

59.1±1.7 b 67.6±0.6 a |

219.0±24.7 a 247.2±9.0 a |

137.1±1.2 a 131.3±5.0 a |

523.0±34.0 a 549.0±48.0 a |

1374.0±13.0 a 1290.0±41.0 a |

| Soluble sugars, mg g-1 DW |

16/8 h CELM |

295.1±22.5 a 268.0±24.5 a |

254.7±24.8 a 289.9±15.2 a |

140.2±17.5 a 134.8±13.7 a |

114.0±8.0 a 116.0±8.0 a |

102.0±4.0 b 145.0±15.0 a |

| Protein, mg g-1 FW | 16/8 h CELM |

174.1±15.9 a 200.5±15.9 a |

195.3±13.9 a 193.8±2.6 a |

194.3±28.7 a 165.1±8.8 a |

168.7±17.4 b 205.5±11.9 a |

169.9±8.3 b 189.3±9.2 a |

| Ascorbic acid, mg g-1FW |

16/8 h CELM |

82.4±16.3 a 74.7±2.3 a |

135.6±5.3 a 140.4±12.4 a |

83.4±14.2 a 83.5±8.1 a |

275±18 a 303±23 a |

231±12 b 269±24 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).