1. Introduction

Breast cancer is characterized by significant heterogeneity, both between patients and within individual tumors, which poses substantial challenges for effective treatment strategies [

1,

2,

3]. Breast tumors are categorized into various molecular subtypes based on hormone receptor status, HER2 expression, and proliferation markers; however, these classifications often fail to capture the full complexity of the disease. Within a single tumor, multiple molecular subtypes can coexist, further complicating treatment approaches [

4]. This complexity is exacerbated by subtype plasticity, a phenomenon reflected by certain breast cancer cell lines, such as MCF7, which can switch between molecular profiles—such as from luminal-A to basal-like—depending on their microenvironment [

5,

6]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a critical role in driving this plasticity. Components of the TME, including signaling molecules, extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins/carbohydrates, and immune cells, significantly influence tumor behavior and subtype expression [

7,

8,

9]. As a result, traditional treatments targeting specific molecular subtypes often prove inadequate, particularly in cases where tumors exhibit the capacity for adaptation and evolution [

10,

11]. This highlights the urgent need for novel molecular targets and more sophisticated, combinatorial therapeutic strategies that account for the dynamic nature of tumor heterogeneity.

WNT inducible signaling protein 1 (WISP1), also known as CCN4, is a matricellular protein that influences key cellular processes such as differentiation, proliferation, migration, and survival [

12]. Although WISP1 does not have a direct structural role within the ECM, its expression during embryonic development and tissue repair suggests its involvement in maintaining tissue homeostasis. Abnormal WISP1 expression is associated with various pathological conditions, including cancer [

13,

14]. In breast cancer, WISP1 is notably overexpressed in primary tumors and correlates with advanced tumor stages, size, and lymph node metastasis [

15,

16]. Notably, WISP1 promotes tumor growth and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), characterized by changes in markers like E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Snail, and β-catenin [

17,

18]. Additionally, WISP1 represses the tumor suppressor NDRG1 and may act as a paracrine inhibitor of type 1 cell-mediated immunity, promoting type 2 immunity and thereby enhancing tumor progression [

15]. Furthermore, WISP1 levels increase following PTEN knockdown, facilitating cell migration and invasion [

14]. Consistent with these findings, elevated WISP1 expression has been associated with poor clinical outcomes and WISP1 has been characterized for its oncogenic functions, driving tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis in several cancer types.

Another key player in the TME is Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor (MIF), a 12.5 kDa trimeric protein encoded by the

MIF gene on human chromosome 22 [

19]. Initially identified for its ability to inhibit macrophage migration, MIF is expressed by a wide range of immune and non-immune cells [

20]. Elevated levels of MIF are found in several cancers, including breast cancer, where increased MIF concentrations in both tumor tissues and the bloodstream are associated with poor prognosis [

21]. MIF is secreted into the extracellular space in response to inflammatory stimuli or stress, where it influences tumor progression via autocrine and paracrine signaling mechanisms. MIF primarily exerts its effects through interaction with the CD74 receptor, which is frequently upregulated in breast cancer and has been particularly associated with aggressive tumor features, including increased lymph-node invasion [

22]. This association is more pronounced in more aggresive subtypes of breast cancer, such as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [

23]. CD74-mediated signaling is often co-activated by CD44, a major ECM receptor that also serves as a main cancer stem cell marker, leading to the activation of key oncogenic pathways, including the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways, which promote tumor cell proliferation, migration, and survival [

24]. Additionally, MIF inhibits p53-dependent apoptosis, and promotes the secretion of factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [

25,

26], facilitating angiogenesis and supporting the growth of metastatic lesions [

27,

28]. The interaction of MIF with the tumor stroma further contributes to an environment that favors tumor progression and metastasis [

29]. Interestingly, while extracellular MIF correlates with poor outcomes, cytosolic MIF is linked to improved survival, reflecting a context-dependent function [

30].

Understanding the complex roles of WISP1 could provide new avenues for targeted therapies and improve our approach to treating the heterogeneous nature of breast cancer. A current challenge is to explore how targeting WISP1 or its related pathways could help overcome current treatment limitations and address breast tumor plasticity. Given the established connection between WISP1 and MIF [

31] and their critical roles in shaping the TME to exacerbate tumor aggressiveness, this study aims to elucidate how this WISP1/MIF axis influences breast tumor plasticity and aggressiveness. Τhe findings aim to offer potential new targets for therapeutic interventions that address the dynamic and adaptive nature of breast cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Reagents

MCF7 (non-invasive, ER+) breast cancer cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). MCF7 cells were routinely cultured in complete medium [Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, #LM-D1110/500, Biosera) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, #FB-1000/500, Biosera) and a cocktail of antimicrobial agents (100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin)] at 37 °C, 95% humidified air/5% CO2. Every two days, medium was replaced with fresh one. When approximately 80% cell confluency was reached, cells were trypsinized for 3 min with trypsin-EDTA 1× in PBS (#LM-T1706/500, Biosera) and seeded in new Petri dishes. All experiments were conducted in serum-free conditions.

4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); PP2 (Src kinase inhibitor) and ISO-1 (MIF inhibitor) were from Tocris Bioscience (Bio-Techne Ltd, Abingdon Oxon, UK). Recombinant human WISP1, endotoxin-free, and active MIF were purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) and ImmunoTools (Friesoythe, Germany), respectively.

Primers for PCR were obtained from Biomers.net GmbH (Ulm, Baden-Württemberg, Germany). The RNA extraction kit (Nucleo Spin) was purchased from Macherey-Nagel (Düren, Germany); and the PCR reactions were carried out using the Prime Script RT Reagent Kit from Takara, Nippon (Japan) and the KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix kit from KAPA Biosystems (Boston, MA, USA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Handling and storage of all reagents was performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

2.2. Determination of Secreted Hyaluronan Concentration

MCF7 cells were cultured under serum-free conditions as described above. At the desired time points, culture supernatants were collected, centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min to remove cell debris, and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Secreted hyaluronan levels were quantified using the Hyaluronan ELISA Kit (Quantikine, R&D Systems, #DHYAL0) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader, and HA concentrations were calculated based on a standard curve generated with known concentrations of hyaluronan.

2.3. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA)

Secreted protein levels were quantified by ELISA according to the manufacturers’ instructions, with all samples run in technical duplicate on the same plate per analyte. The following kits were used: Mouse MIF Sandwich ELISA Kit (KE10027, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 96T), human MMP-1 ELISA Kit (EHMMP1, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA),total MMP-2 ELISA Kit (Quantikine, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA, #MMP200), human MMP-9 ELISA Kit (BMS2016-2, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), human MT1-MMP ELISA Kit (EEL068, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), human TIMP-1 ELISA Kit (Quantikine, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA, #DTM100), and human TIMP-2 ELISA Kit (Quantikine, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA, #DTM200). Standards and samples were prepared with kit-supplied diluents and diluted as needed to fall within each assay’s linear range. Absorbance was read at 450 nm with 540–570 nm reference correction using a microplate reader (Infinite M200, Tecan), and concentrations were calculated from 4-parameter logistic standard curves after background subtraction. Results are reported as pg/mL or ng/mL of conditioned medium and, where indicated, normalized to producing cell number or total cellular protein from matched wells. Biological replicate numbers and statistical tests are provided in the figure legends and Statistics subsection.

2.4. Detection of Phosphorylated Src Family Kinases by Capture ELISA

MCF7 cells were treated with WISP1 (500 ng/mL) for 24 h, washed with PBS, and lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (700 μL per 90 mm dish). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, and supernatants were collected. Ninety-six–well polystyrene plates were coated overnight at 4 °C with antibodies specific for c-Src (mouse monoclonal, Cat. No. 66606-1-Ig, Proteintech, Germany), Lyn (rabbit polyclonal, Cat. No. 18135-1-AP, Proteintech, Germany), or Fyn (rabbit polyclonal, Cat. No. 11097-1-AP, Proteintech, Germany) at 2 μg/mL in PBS (100 μL/well). Plates were washed three times with PBS-T (PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20) and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS-T (200 μL/well) for 1 h at 37 °C. Following three washes with PBS-T, cell lysates (100 μL/well, in duplicate) were added and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Plates were washed five times with PBS-T, and bound phosphorylated proteins were detected using HRP-conjugated anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (mouse monoclonal, Cat. No. APY03-HRP, Cytoskeleton, Inc., 1:2000 in PBS-T containing 0.25 M NaCl, 100 μL/well) for 2 h at 37 °C. After five washes with PBS-T containing 0.25 M NaCl, TMB substrate (100 μL/well) was added, and color development was allowed for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. The reaction was stopped with 2 M H₂SO₄ (100 μL/well), and absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Infinite M200, Tecan).

2.5. Immunofluorescence Microscopy

MCF7 cells (3 × 10⁴) were seeded on sterile glass coverslips in complete medium and incubated for 24 h, followed by overnight serum starvation. Cells were then stimulated with recombinant WISP1 (500 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of PP2 or ISO-1, or with recombinant MIF (100 ng/mL), for 24 h in serum-free medium. Following stimulation, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100/PBS-Tween 0.01% for 10 minutes, and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/PBS-Tween 0.01% for 1 h. Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a primary antibody against E-cadherin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; Cat. #3195) diluted in 1% BSA/PBS-Tween 0.01%, followed by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; Cat. #A-11008) for 1 h at 37 °C in the dark. F-actin was visualized using Phalloidin-iFluor™ 488 Conjugate (AAT Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA, USA; Cat. #23115, 1:40 dilution). Nuclei were counterstained and coverslips mounted with Vectashield Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA; Cat. #H-1200). Between each step after fixation, cells were washed three times with PBS-Tween 0.01%. Images were acquired using a fluorescence phase-contrast microscope (Olympus CKX41, QImaging Micro Publisher 3.3RTV) at 40× magnification.

2.6. Western Blotting

For analysis of secreted MIF, equal protein concentrations from conditioned medium were determined using the Bradford assay (Thermo Scientific, Cat. #23236) and enriched by ammonium sulfate precipitation [(NH₄)₂SO₄, 50% saturation]. Precipitates were dissolved in Laemmli sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol, boiled for 5 min, and subjected to SDS–PAGE on 15% polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes, blocked, and immunoblotted using an anti-MIF antibody (Proteintech, Cat. #20415-1-AP). For analysis of cellular proteins, MCF-7 cells were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (1×, Chemicon, Millipore, CA, #20-201) on ice for 30 min with intermittent vortexing. Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and supernatants were collected. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Thermo Scientific). Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS–PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (Macherey-Nagel). Membranes were blocked with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: E-cadherin (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. #3195), NDRG1 (Novus Biologicals, HRP-conjugated, Cat. #NB160805), and α-tubulin (Invitrogen, Cat. #322500). After three washes with PBS-T, membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit IgG, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. #A0545; or anti-mouse IgG, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. #A4416) for E-cadherin and α-tubulin. NDRG1 was detected directly using HRP-conjugated streptavidin (R&D Systems, Cat. #DY998) without additional secondary antibody. Immunoreactive protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Immunobilon® Crescendo Western HRP Substrate, Millipore/Merck, Cat. #WBLUR0100). Band intensity was quantified by densitometry using Scion Image PC software and expressed in arbitrary units (pixels).

2.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from MCF7 cells using a Nucleo Spin RNA kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was performed using the Prime Script RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Nippon, Japan) as per the provided protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis was conducted using the KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix (2×) kit (KAPA Biosystems, Boston, MA, USA), following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Assays were performed in triplicate on a Rotor-Gene Q detection system (Qiagen) in a total volume of 20 μL, comprising 10 μL KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix (2×), 0.5 μL of each primer at a concentration of 8 μM, 1–2 μL of cDNA (0.5–20 ng), and 7 or 8 μL of dH2O. The cycling conditions included 3 min enzyme activation at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 3 s and 50–60 °C for 20 s. GAPDH was used as an internal standard. Relative expression of different gene transcripts was calculated by the ΔΔCt method. The Ct of any gene of interest was normalized to the Ct of the normalizer (GAPDH). Fold changes (arbitrary units) were determined as 2

−ΔΔCt. Genes of interest and utilized primers are presented in

Table 1.

2.8. Wound Healing Assay

MCF7 cells were cultured in 6-well plates in complete medium until confluent monolayers. Cells were then serum starved for 16 h and the cell monolayer was scratched using a pipette tip. Cells were washed two times with PBS followed by the addition of serum free DMEM containing the desired factors [WISP1 (500 ng/mL), MIF (100 ng/mL), PP2 (1 μΜ), ISO-1 (100 μΜ)] plus cytarabine (Pfizer). For the pre-treatment with PP2 and ISO-1 inhibitors prior to WISP1 treatment, cells were pre-incubated with the inhibitors in serum free medium for 30 min. The cells were then incubated and photographed at various time points (0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h) using a colour digital camera (CMOS) mounted on a phase contrast microscope (OLYMPUS CKX41, QImaging Micro Publisher 3.3RTV) through a 10× objective. The images were quantified by measuring the wound area with Image J 1.50b Launcher Symmetry Software.

2.9. MTT Assay

The MTT assay was used to assess the effect of WISP1/MIF axis in the viability and proliferation of MCF7 cells. MCF7 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 10^4 cells per well and allowed to adhere for 24 hours. Cells were then treated with various concentrations of test compounds or inhibitors, diluted in serum-free DMEM. After 24, 48, or 72 h of incubation, the medium was removed, and the wells were washed with PBS to remove any residual test substances. Next, 100 μL of MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well and incubated for 4 hours at 37 °C. The formazan crystals formed in living cells were dissolved by adding 100 μL of DMSO to each well. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader. The results were expressed as the percentage of viable cells compared to control cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) alone. The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times to ensure reproducibility.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical differences were evaluated using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05. All analyses and graphs were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.5.0 software.

4. Discussion

One of the major hurdles in treating metastatic breast cancer lies in the molecular pathways that promote cancer cell aggressiveness and therapy resistance. This study underscores the critical role of the WISP1/MIF axis in promoting the malignant properties of MCF7 cells, a widely used model for non-invasive estrogen receptor-positive (ER

+) breast cancer, and demonstrates how this signaling axis may complicate therapeutic strategies aimed at controlling metastasis and resistance. WISP1 (CCN4) has been increasingly recognized for its oncogenic role across various cancers [

16,

36], while higher WISP1 expression correlates with advanced disease characteristics, such as larger tumors, lymph node metastasis, and HER-2/neu overexpression [

16,

37,

38,

39]. MCF7 cells express WISP1 that is primarily localized extracellularly aligning with WISP1’s classification as a secretory matricellular protein [

33,

40,

41]. The presence of WISP1 in non-invasive MCF7 breast cancer cells supports our rationale for utilizing this model.

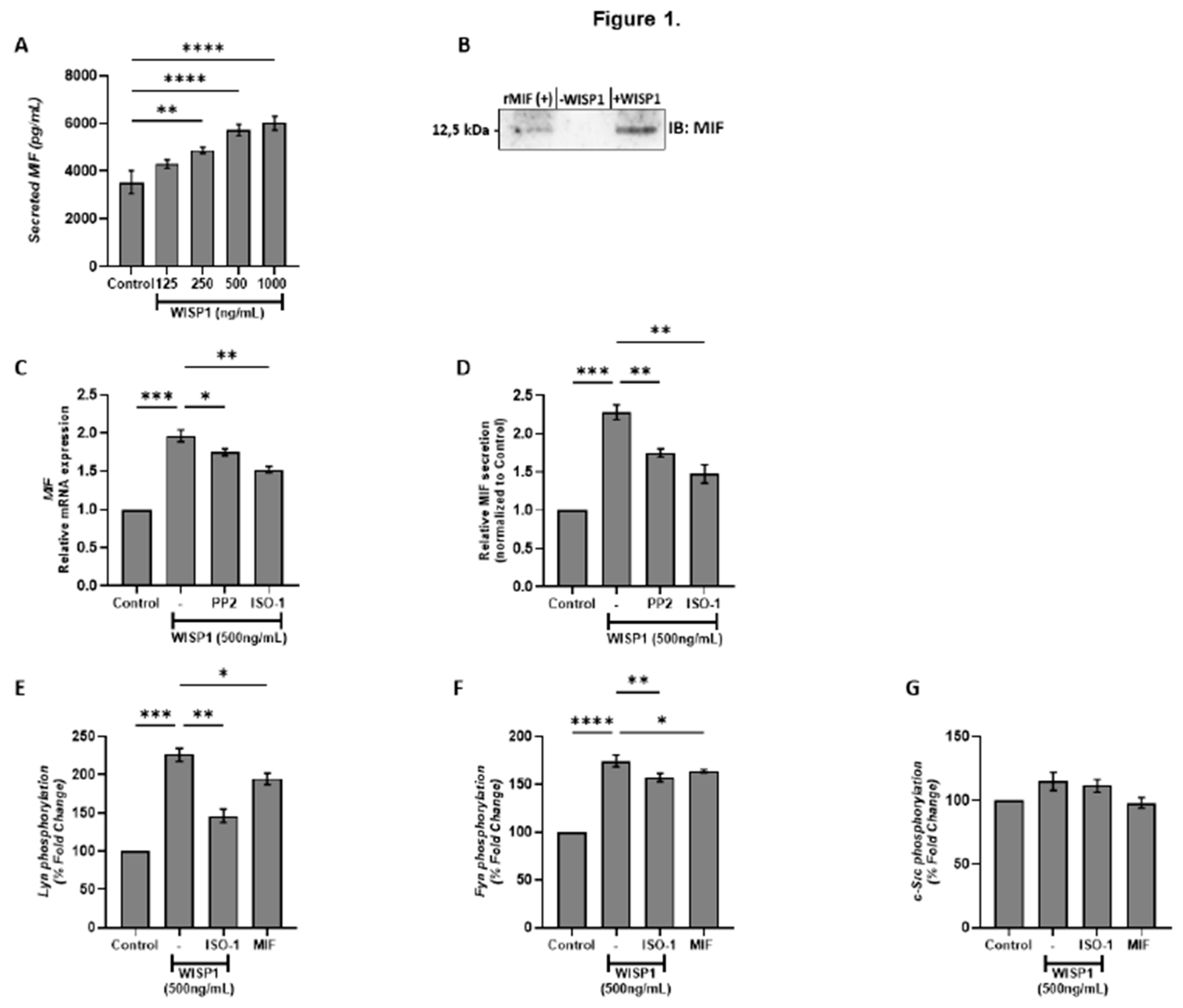

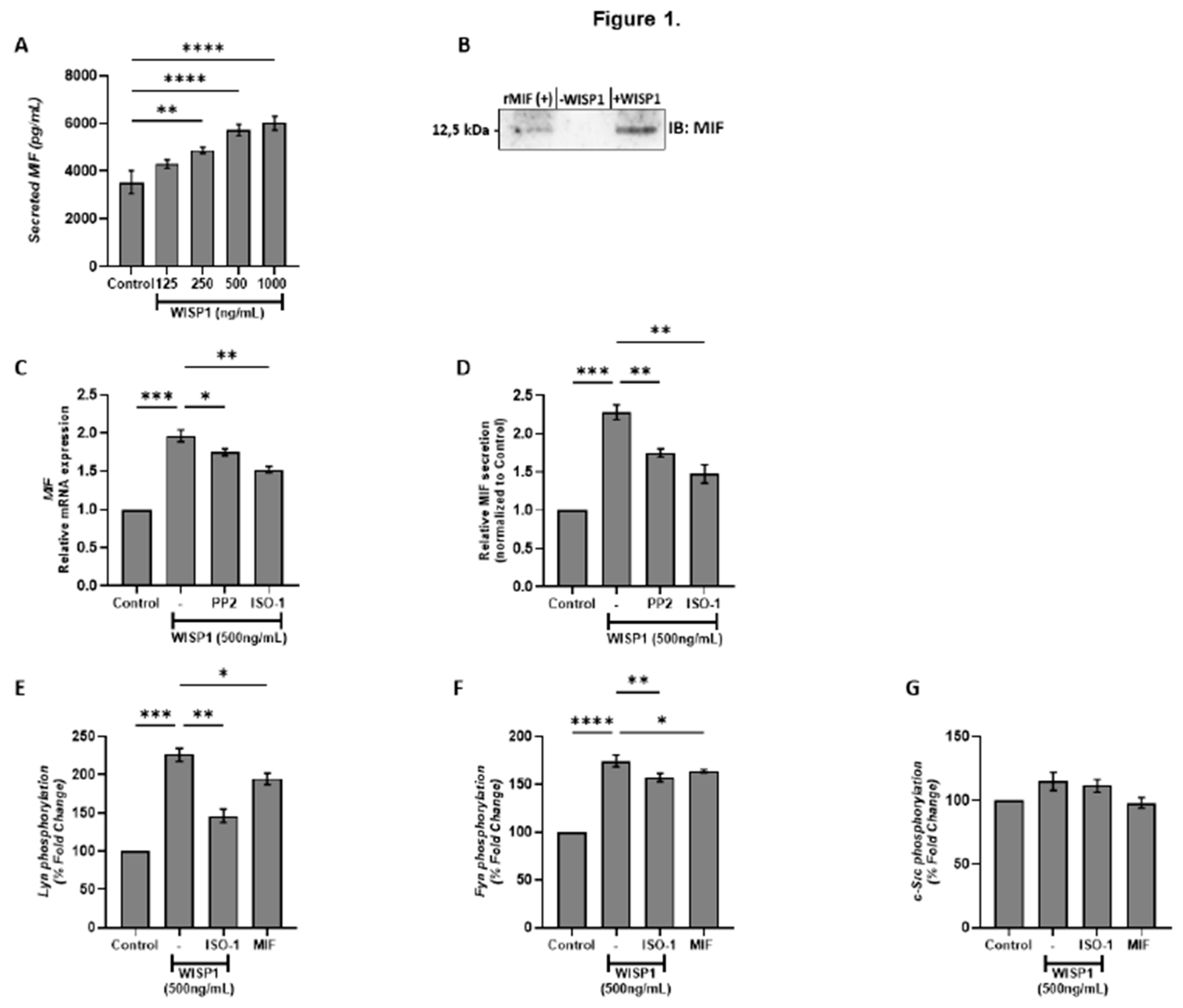

Our findings show that WISP1 induces the expression of MIF, a cytokine known to be linked to pro-tumorigenic and pro-metastatic activities in various cancers [

29,

42,

43,

44,

45]. The concentration of 500 ng/mL was identified as optimal for maximal MIF induction in MCF7 cells after 24 hours, providing a novel insight into WISP1’s effects in this context. As shown in

Figure 1, the induction of MIF by WISP1 is mediated through Lyn and Fyn, but not c-Src, kinase activation. Src kinases have been shown to facilitate the spread of cancer cells to distant organs and have been implicated in resistance to conventional therapies, such as chemotherapy and hormonal treatments, by sustaining survival signaling pathways in breast cancer cells [

46]. Furthermore, our study reveals that MIF itself can regulate its own expression through a feedback loop, since pre-treatment of MCF7 cells with ISO-1, a specific inhibitor of MIF activity, resulted in downregulation of the enhanced MIF expression induced by WISP1. This suggests that MIF can promote its own expression in response to WISP1 signaling, further reinforcing the role of the WISP1/MIF axis in driving tumor progression and therapy resistance. The above suggest that

dual targeting of Lyn/Fyn tyrosine kinases and MIF may be necessary to fully counteract WISP1-driven metastasis in breast cancer.

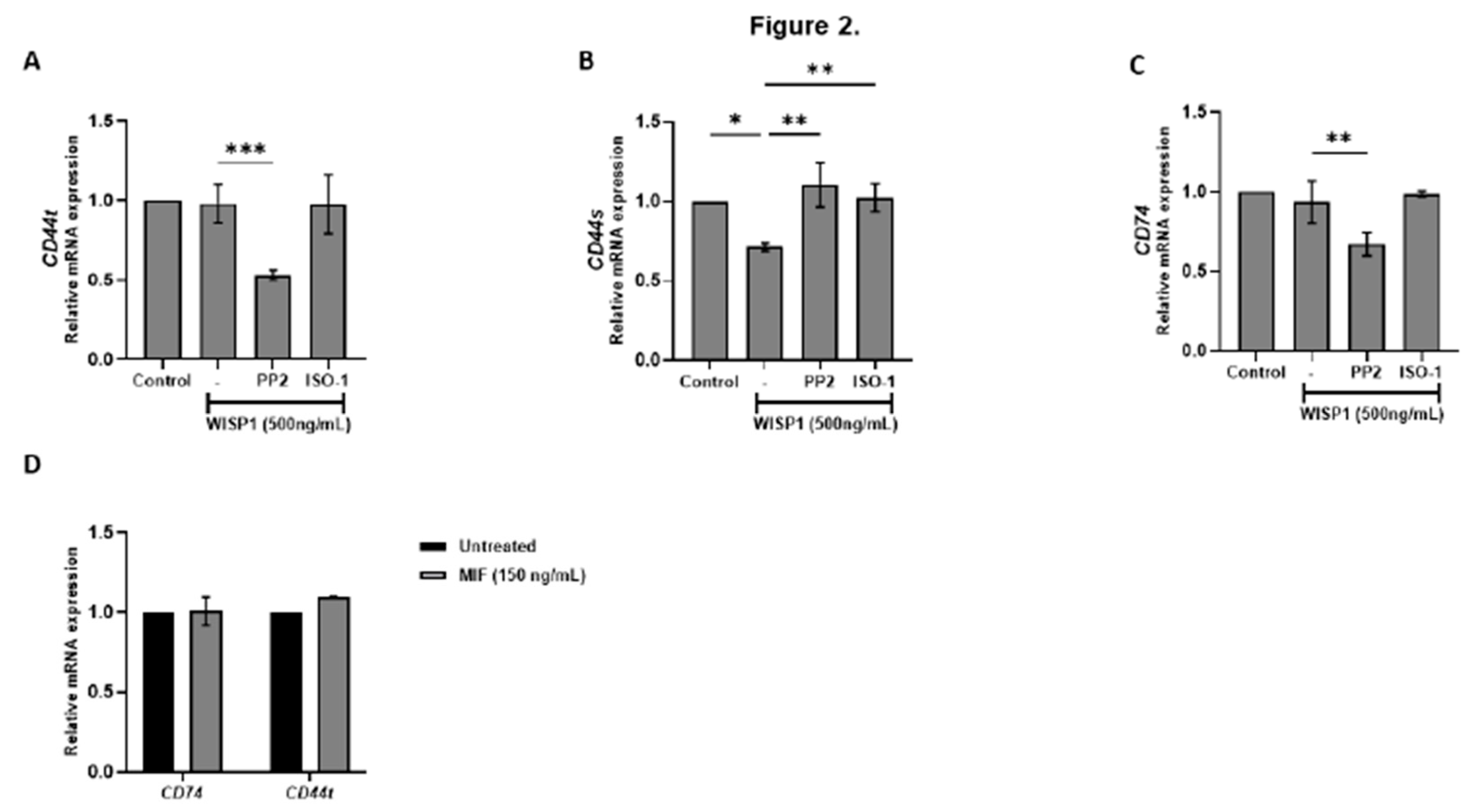

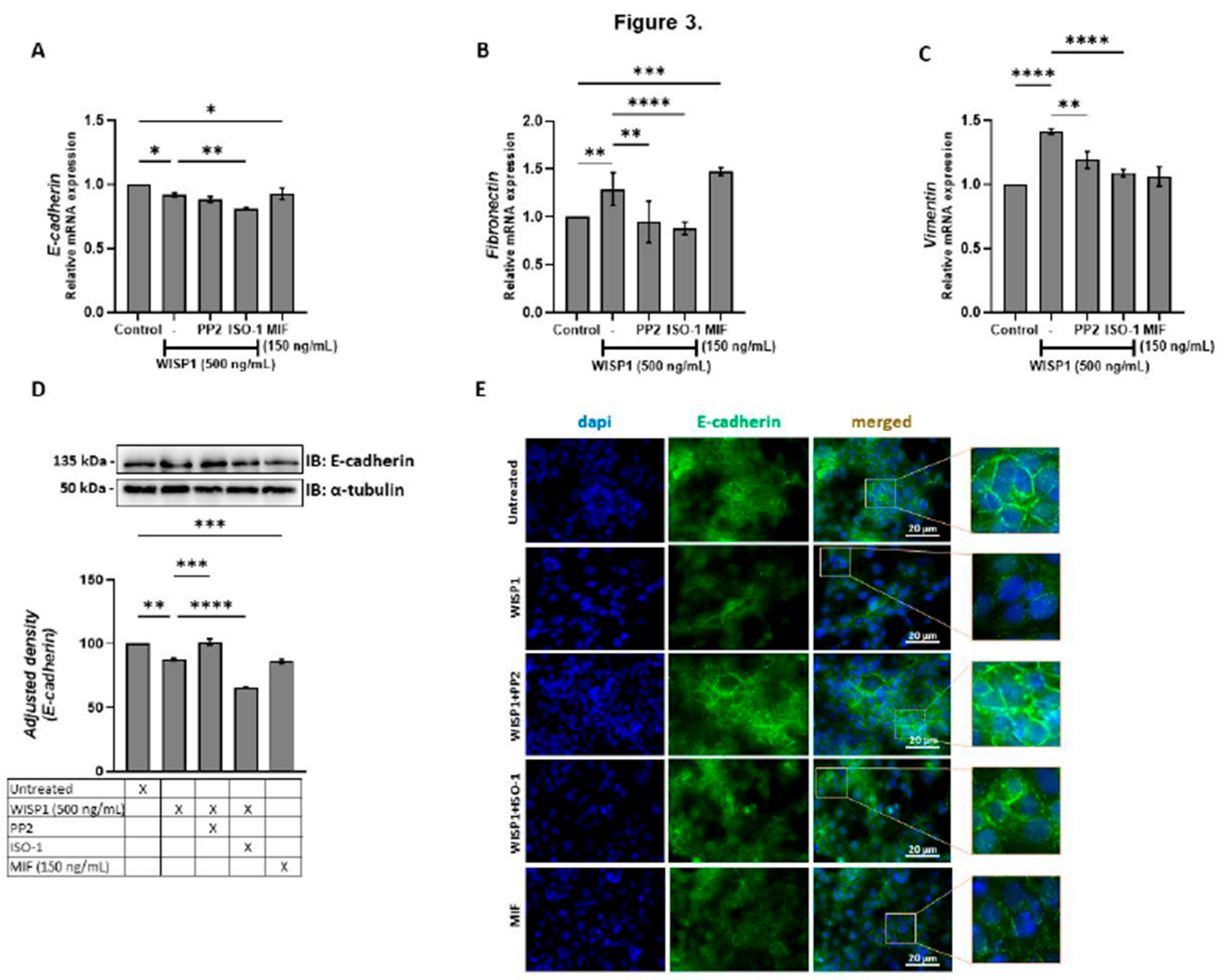

Moreover, our findings, establish that WISP1 enhances metastatic plasticity in ER⁺ breast cancer by amplifying MIF signaling and engaging Lyn/Fyn-mediated cytoskeletal remodeling, even in low-CD74 contexts. While invasive breast cancers typically rely on high CD74 to maximize MIF-driven EMT [

22], our results raise the possibility that ERα⁺ tumors such as MCF7 cells achieve similar outcomes through WISP1-mediated MIF amplification (

Figure 1A). Although WISP1 does not directly elevate CD74 (

Figure 2C), increased MIF likely strengthens CD74-MIF interactions via mass action in low-CD74 environments [

47]. WISP1 also selectively downregulated CD44s without altering total CD44, suggesting a compensatory upregulation of CD44v isoforms. This isoform switching, probably influenced by ERα status [

48,

49], may couple MIF/CD74 to cofilin-driven actin reorganization and EMT [

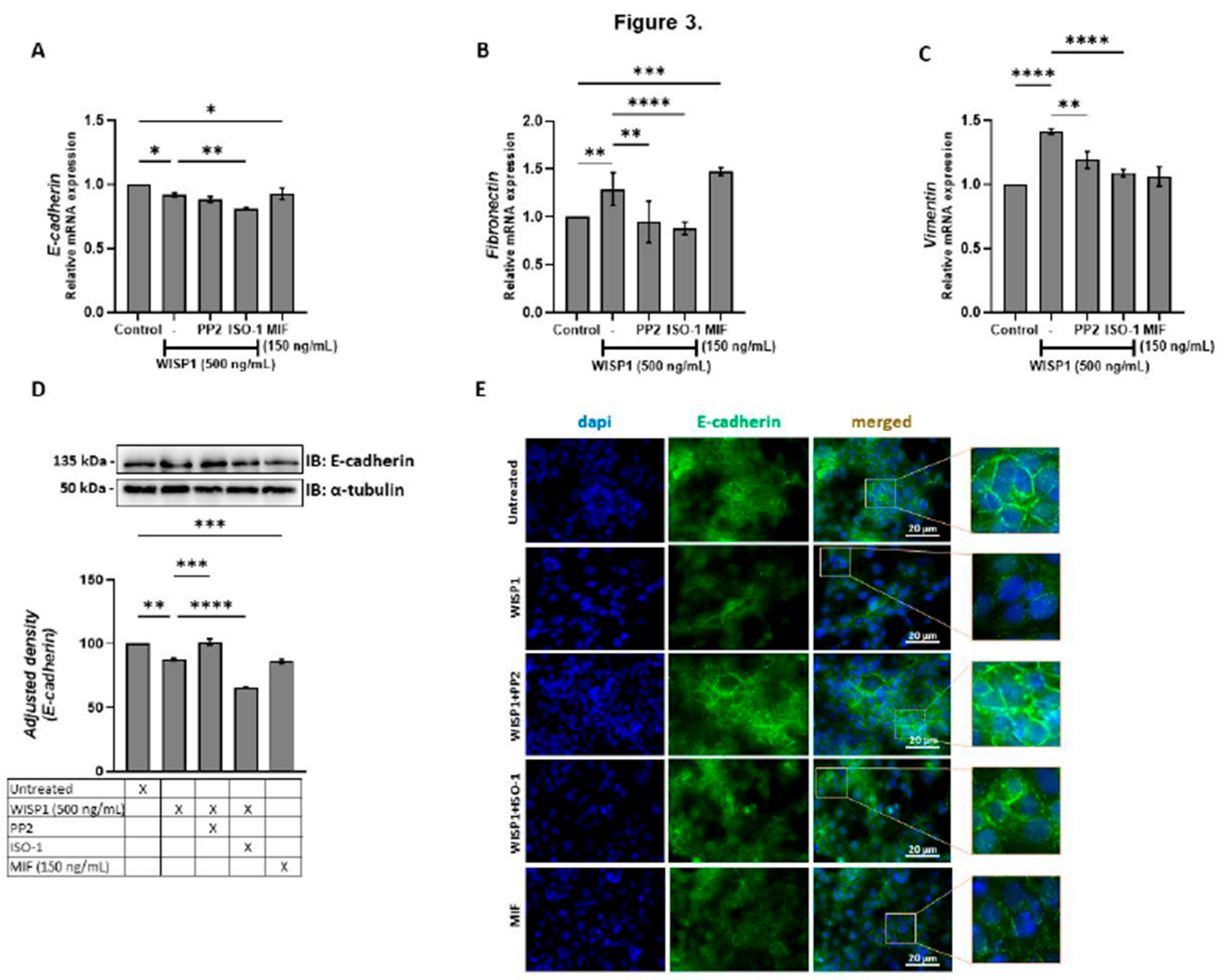

50]. Indeed, WISP1 treatment induced a partial EMT phenotype characterized by reduced membrane E-cadherin, increased fibronectin, and elevated vimentin, consistent with migratory yet adaptable tumor cell states [

51,

52,

53]. Critically, WISP1’s EMT program requires both MIF-CD74/CD44v signaling and Lyn/Fyn activation; MIF maintains mesenchymal traits through pathways previously tied to CD44v-mediated metastasis [

12,

54,

55], while Lyn/Fyn kinases—overexpressed in aggressive breast cancers (34–38,72)—orchestrate E-cadherin internalization and actin remodeling. The functional independence of these arms is evidenced by treatment with either ISO-1 (MIF inhibitor) or PP2 (SFK inhibitor) each reversing EMT markers, suggesting synergistic therapeutic potential. This dual mechanism aligns with established Src family kinase roles in FAK/Akt/ERK-driven migration (36,41,42) but uniquely positions WISP1 as an upstream integrator of inflammatory (MIF) and cytoskeletal (SFK) pathways in ERα⁺ contexts, suggesting synergistic therapeutic potential. While our data support a model where WISP1-induced CD44 isoform switching synergizes with MIF amplification and SFK activation to drive cytoskeletal reorganization and invasive protrusions in ER⁺ tumors, critical questions persist. Future studies must delineate [

1] how ERα regulates CD44 splicing to favor pro-invasive isoforms and [

2] whether CD44v-MIF complexes spatially coordinate with Lyn/Fyn kinases at invasive fronts to amplify protrusive activity. Resolving these mechanisms will clarify how WISP1 licenses metastatic plasticity in ERα⁺ contexts and identify strategies to uncouple inflammatory (MIF/CD74) from cytoskeletal (SFK) signaling—a therapeutic opportunity for limiting adaptive aggression in hormonally regulated tumors.

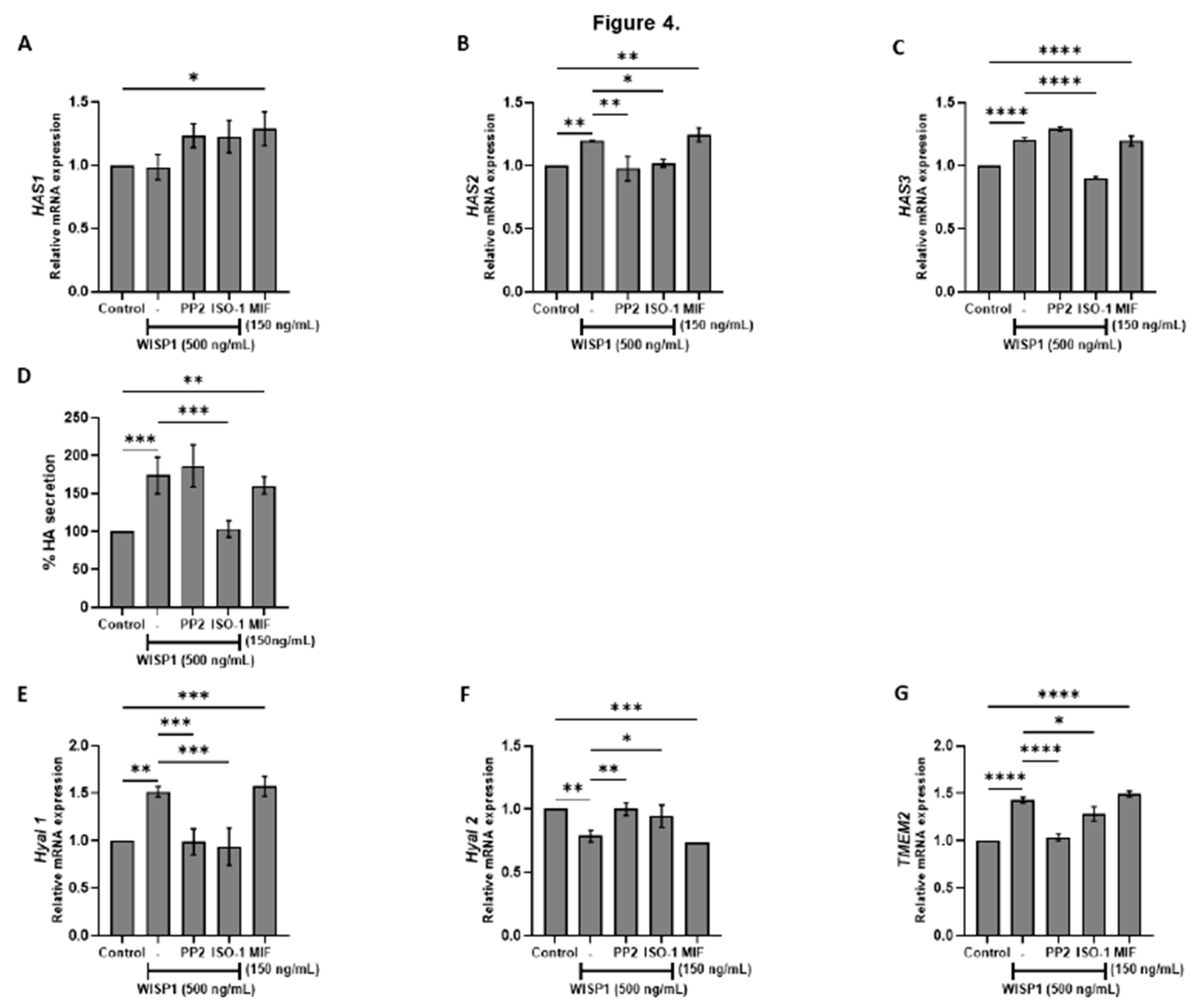

Beyond its role in EMT, WISP1 emerges as a critical regulator of hyaluronan metabolism, linking intracellular signaling to extracellular matrix remodeling in ERα

+ breast cancer. Our data revealed that WISP1 treatment significantly upregulated the expression of hyaluronan synthase genes HAS2 and HAS3, while suppressed

HYAL2 and induced

HYAL1 and

TMEM2 hyaluronidases. These alterations in the hyaluronan metabolizing enzymes led to an increased synthesis of high molecular weight HA (HMW-HA) while allowing the local production of low molecular weight hyaluronan fragments (LMW-HA). Critically, MIF/CD74 signaling sustains this catabolic imbalance, as MIF inhibition restored

HYAL2 expression, whereas Src inhibition attenuated

HAS2/3 induction. This HA landscape creates a hydrated, loose ECM (48,49) that facilitates invasion—a process amplified by CD44v isoforms, which bind HA to activate pro-metastatic pathways (12,48). Notably, HA fragmentation may further feed forward through CD44v-MIF crosstalk, as LMW-HA enhances CD44 clustering and inflammatory signaling [

56,

57]. The convergence of WISP1’s transcriptional control over HA metabolism with its regulation of MIF/SFK-driven cytoskeletal remodeling positions it as a central integrator of biochemical and biophysical cues in ER⁺ tumors, while suggesting WISP1-mediated HA remodeling as a potential therapeutic target.

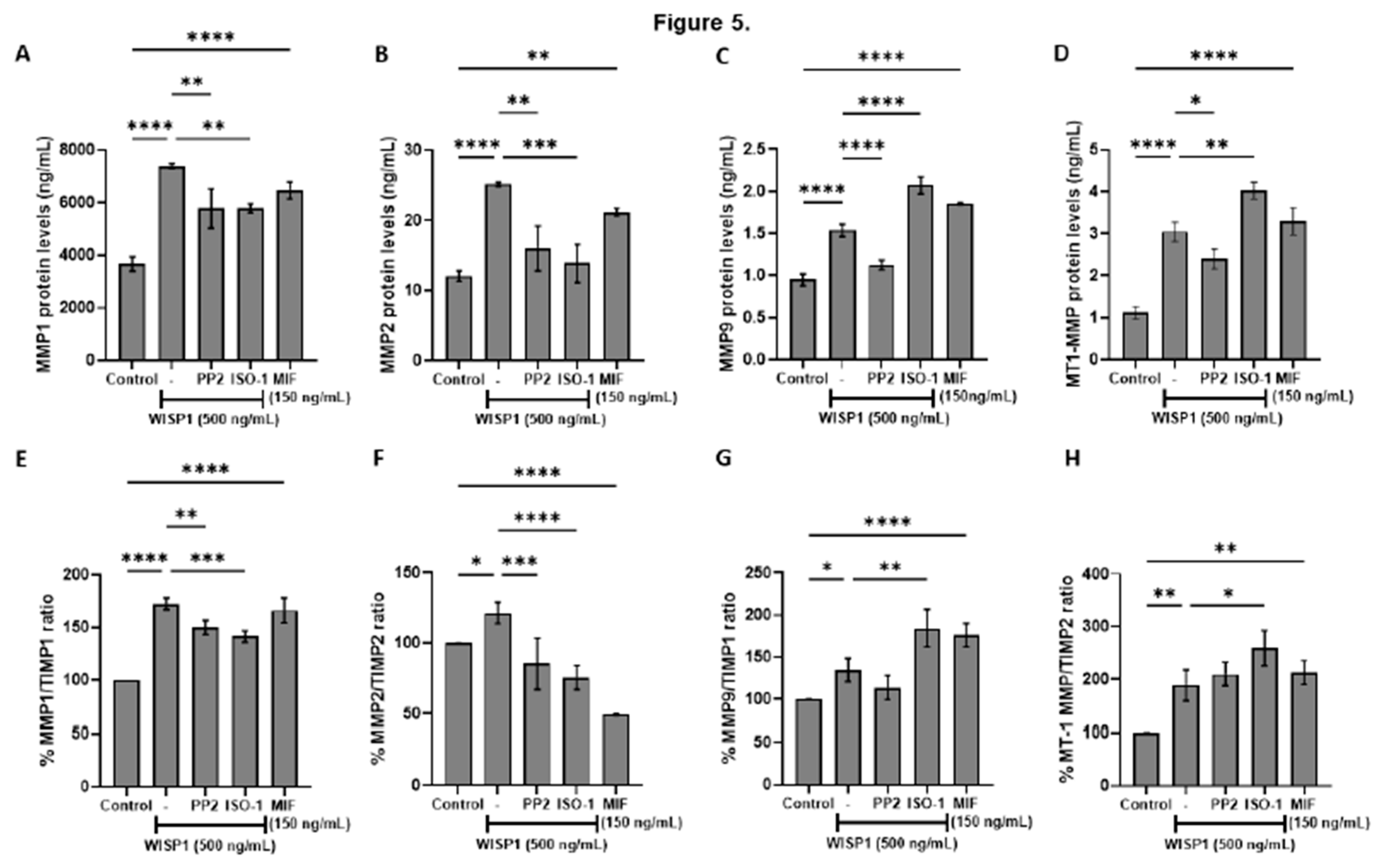

Furthermore, WISP1

acts as a regulator of extracellular matrix remodeling in breast cancer, broadly

increasing the protein levels of matrix metalloproteinases, including MMP1, MMP2, MMP9, and MT1-MMP, and shifting the MMP/TIMP balance toward a proteolytic phenotype [

34,

35]. This aligns with previous studies reporting that WISP1 promotes MMP2 and MMP9

in chondrosarcoma and osteosarcoma cells, thereby facilitating motility and invasion [

58]. MMP induction is further reinforced by HA–CD44 interactions, which

elevate MT1-MMP and contribute to invasive and metastatic phenotypes [

59,

60,

61]. Studies in PC3 prostate cancer cells

show that WISP1-induced β-catenin signaling

is linked to

HAS2 transcription, suggesting

coordinated regulation of hyaluronan metabolism and MMP activity during ECM remodeling [

62]. Src kinase inhibition with PP2 attenuated these effects, indicating that Src kinases are critical mediators of WISP1-induced MMP regulation [

31,

63,

64]. Src is a well-established regulator of MMP expression and activity and often cooperates with FAK to drive cancer cell invasion and migration [

65,

66]. In particular, Src–FAK signaling upregulates MMP2 and MT1-MMP, which degrade type IV collagen in the basement membrane, a key barrier to cancer invasion [

67,

68]. Thus, WISP1’s activation of Src facilitates ECM degradation and promotes tumor cell migration, consistent with mechanisms observed in other Src-driven invasive cancer models. Notably, blockade of MIF activity

reduced WISP1-induced MMP1 and MMP2 protein levels as well as MMP1/TIMP1 and MMP2/TIMP2 ratios, while exogenous MIF enhanced all examined MMPs, suggesting that

the WISP1/MIF axis broadly elevates MMPs in non-invasive breast cancer cells, contributing to a pro-invasive phenotype. However, MIF blockade further increased MMP9 and the MMP9/TIMP1 ratio, and it similarly increased MT1-MMP and the MT1-MMP/TIMP2 ratio, implying a more complex, context-dependent role for MIF in regulating MMP9 and MT1-MMP that warrants further investigation.

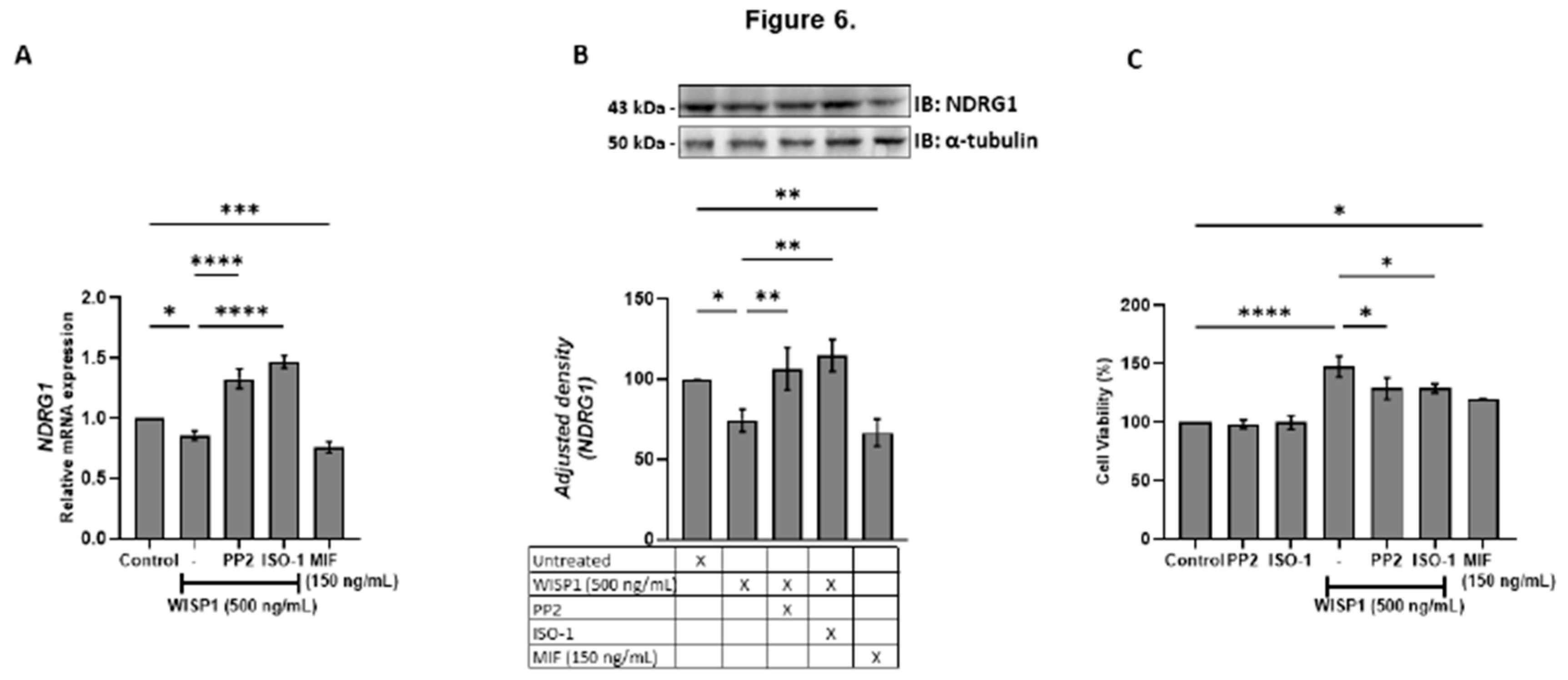

We also identified NDRG1 as a downstream target repressed by WISP1 and MIF. As a metastasis suppressor that stabilizes E-cadherin and restrains oncogenic pathways (PI3K/Akt, Src, NF-κB) [

69,

70], its suppression provides a mechanistic link between WISP1 signaling and loss of epithelial integrity. Both Src and MIF inhibition restored NDRG1 expression while attenuating survival, migration, indicating that both pathways act as intermediates in WISP1 signaling. The inverse relationship between NDRG1 expression and cell viability is consistent with reports linking NDRG1 to proliferative and metastatic pahenotypes [

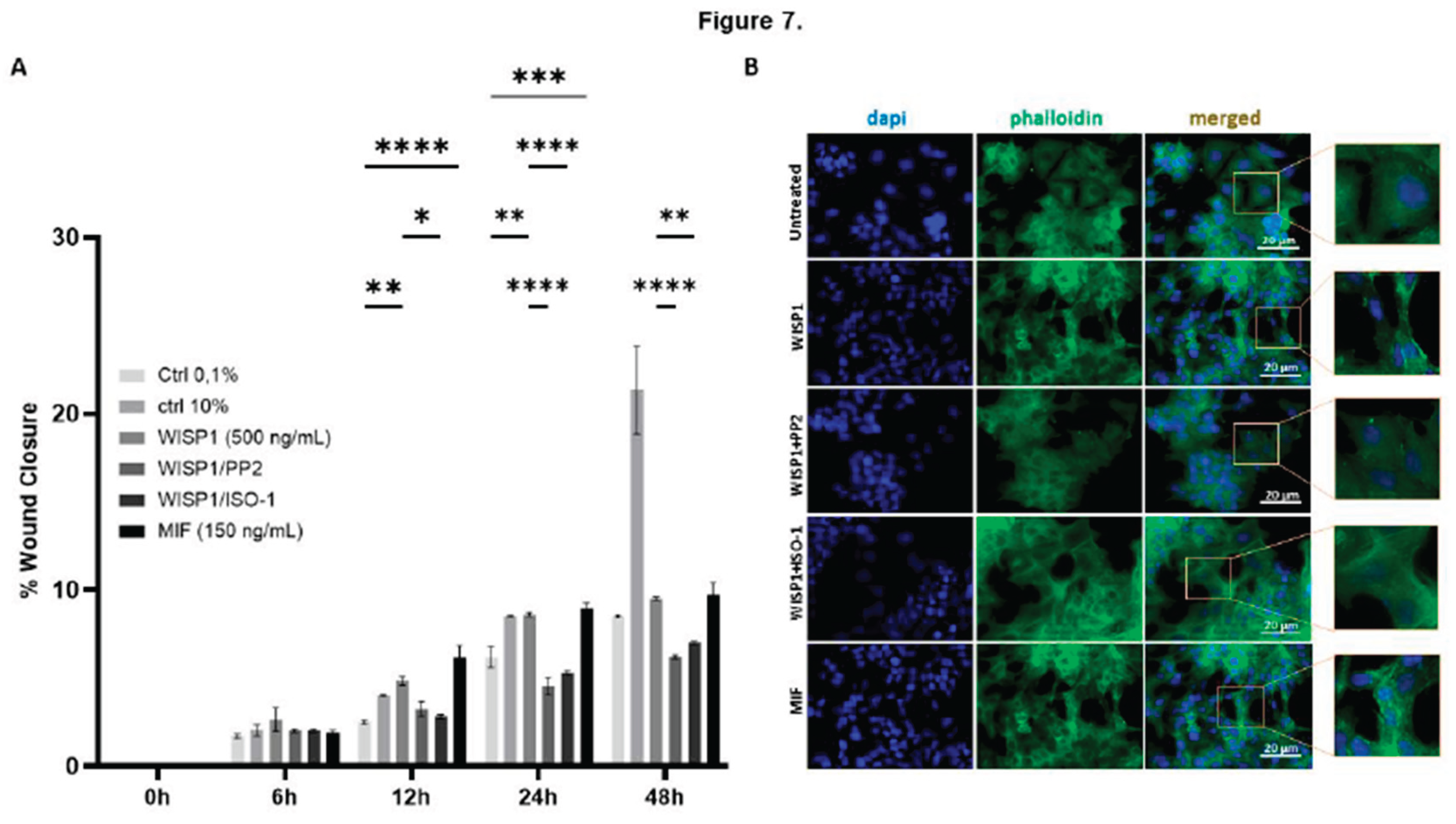

71]. Recombinant MIF alone similarly suppressed NDRG1 and enhanced survival, highlighting its dual role as both a mediator of WISP1 activity and an independent tumor-promoting factor. In parallel, WISP1 was found to significantly enhance breast cancer cell migration, accompanied by cytoskeletal remodeling characterized by actin filament reorganization, stess fiber formation and cell elongation, features typically associated with a motile phenotype. MIF induced a comparable response. These changes were attenuated by Src inhibition or MIF blockade, indicating that the same mechanisms mediating NDRG1 repression also regulate actin organization and motility. Given the central role of cytoskeletal dynamics in metastatic dissemination, these results extend the pro-survival functions of WISP1/Src/MIF axis to induce motility programs that enable invasion.

Figure 1.

WISP1 induces MIF expression and secretion via Src kinase activation. (A) MCF7 cells were cultured with increasing concentrations of recombinant WISP1 (0, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 ng/mL) for 24 h, and secreted MIF protein levels were measured in cell culture supernatants by ELISA. (B) Western blot analysis of secreted MIF in supernatants from MCF7 cells. Cells were untreated (–WISP1) or treated with WISP1 (+WISP1). Recombinant MIF (rMIF) was used as a positive control. Cell culture supernatants were collected and immunoblotted with an anti-MIF antibody. A band at ~12,5 kDa indicates secreted MIF. (C–D) MCF7 cells were pretreated for 30 minutes with the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 μM) or the MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 μM), followed by stimulation with WISP1 (500 ng/mL) for 24 h. (C) MIF mRNA expression was analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR). (D) Secreted MIF protein levels in the cell culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA. (E) In situ kinase assay of Lyn, Fyn, and c-Src phosphorylation in cells treated with WISP1 (500 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM), or recombinant MIF (150 ng/mL). Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Figure 1.

WISP1 induces MIF expression and secretion via Src kinase activation. (A) MCF7 cells were cultured with increasing concentrations of recombinant WISP1 (0, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 ng/mL) for 24 h, and secreted MIF protein levels were measured in cell culture supernatants by ELISA. (B) Western blot analysis of secreted MIF in supernatants from MCF7 cells. Cells were untreated (–WISP1) or treated with WISP1 (+WISP1). Recombinant MIF (rMIF) was used as a positive control. Cell culture supernatants were collected and immunoblotted with an anti-MIF antibody. A band at ~12,5 kDa indicates secreted MIF. (C–D) MCF7 cells were pretreated for 30 minutes with the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 μM) or the MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 μM), followed by stimulation with WISP1 (500 ng/mL) for 24 h. (C) MIF mRNA expression was analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR). (D) Secreted MIF protein levels in the cell culture supernatants were quantified by ELISA. (E) In situ kinase assay of Lyn, Fyn, and c-Src phosphorylation in cells treated with WISP1 (500 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM), or recombinant MIF (150 ng/mL). Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

WISP1 regulates CD74 and CD44 mRNA expression. MCF7 cells were treated for 24 h with WISP1 (500 ng/mL). Where indicated, cells were pre-treated for 1 h with the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 µM) or the MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM) prior to WISP1 stimulation; a recombinant human MIF (rhMIF, 150 ng/mL) condition was also included. (A–C) Relative mRNA expression of total CD44 (CD44t) (A), standard CD44 (CD44s) (B), and CD74 (C) under WISP1 ± inhibitor conditions, quantified by qPCR, normalized to GAPDH, and expressed relative to untreated control. (D) Relative mRNA expression of CD74 and CD44t in cells treated with rhMIF (150 ng/mL) for 24 h, analyzed as above. Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

WISP1 regulates CD74 and CD44 mRNA expression. MCF7 cells were treated for 24 h with WISP1 (500 ng/mL). Where indicated, cells were pre-treated for 1 h with the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 µM) or the MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM) prior to WISP1 stimulation; a recombinant human MIF (rhMIF, 150 ng/mL) condition was also included. (A–C) Relative mRNA expression of total CD44 (CD44t) (A), standard CD44 (CD44s) (B), and CD74 (C) under WISP1 ± inhibitor conditions, quantified by qPCR, normalized to GAPDH, and expressed relative to untreated control. (D) Relative mRNA expression of CD74 and CD44t in cells treated with rhMIF (150 ng/mL) for 24 h, analyzed as above. Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Figure 3.

WISP1 and MIF modulate EMT marker expression via Src kinases. MCF7 cells were treated for 24 h with WISP1 (500 ng/mL). Where indicated, cells were co-treated with the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 µM), MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM), or recombinant human MIF (150 ng/mL). (A–C) Relative mRNA expression of E-cadherin (A), fibronectin (B), and vimentin (C) quantified by qPCR, normalized to GAPDH, and expressed relative to untreated control. (D) Western blot analysis of E-cadherin in cell lysates from the same treatment conditions; α-tubulin served as a loading control. Densitometric quantification of band intensities is shown below the blots. (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of E-cadherin (green) and nuclei (DAPI, blue) under the indicated treatments; insets show higher-magnification (40X) views highlighting cell–cell junctions. Scale bars, 20 µm. Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

WISP1 and MIF modulate EMT marker expression via Src kinases. MCF7 cells were treated for 24 h with WISP1 (500 ng/mL). Where indicated, cells were co-treated with the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 µM), MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM), or recombinant human MIF (150 ng/mL). (A–C) Relative mRNA expression of E-cadherin (A), fibronectin (B), and vimentin (C) quantified by qPCR, normalized to GAPDH, and expressed relative to untreated control. (D) Western blot analysis of E-cadherin in cell lysates from the same treatment conditions; α-tubulin served as a loading control. Densitometric quantification of band intensities is shown below the blots. (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of E-cadherin (green) and nuclei (DAPI, blue) under the indicated treatments; insets show higher-magnification (40X) views highlighting cell–cell junctions. Scale bars, 20 µm. Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

WISP1 regulates hyaluronan metabolism via Src and MIF signaling. MCF7 cells were treated with WISP1 (500 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of the Src family kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 µM), MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM), or recombinant human MIF (150 ng/mL). (A-C, E-G) Gene expression analysis of HAS1 (A), HAS2 (B), HAS3 (C), Hyal1 (E), Hyal2 (F), and TMEM2 (G) by qPCR, normalized to GAPDH and expressed relative to untreated control. (D) Secreted hyaluronan (HA) quantified by ELISA from the same treatment conditions; HA is expressed as percent of untreated cells (control) and normalized to cell number. Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

WISP1 regulates hyaluronan metabolism via Src and MIF signaling. MCF7 cells were treated with WISP1 (500 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of the Src family kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 µM), MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM), or recombinant human MIF (150 ng/mL). (A-C, E-G) Gene expression analysis of HAS1 (A), HAS2 (B), HAS3 (C), Hyal1 (E), Hyal2 (F), and TMEM2 (G) by qPCR, normalized to GAPDH and expressed relative to untreated control. (D) Secreted hyaluronan (HA) quantified by ELISA from the same treatment conditions; HA is expressed as percent of untreated cells (control) and normalized to cell number. Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

Effects of WISP1 and MIF on MMP protein levels and MMP/TIMP ratios. MCF7 cells were treated for 24 h with WISP1 (500 ng/mL). Where indicated, cells were co-treated with the Src family kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 µM) or MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM); a recombinant human MIF (rhMIF, 150 ng/mL) condition was also included. (A–D) ELISA quantification of MMP1 (A), MMP2 (B), MMP9 (C), and MT1-MMP (D) protein levels (ng/mL). (E–H) Ratios of MMP1/TIMP1 (E), MMP2/TIMP2 (F), MMP9/TIMP1 (G), and MT1-MMP/TIMP2 (H), calculated from ELISA values and expressed as percentage relative to untreated control (set to 100%). Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

Effects of WISP1 and MIF on MMP protein levels and MMP/TIMP ratios. MCF7 cells were treated for 24 h with WISP1 (500 ng/mL). Where indicated, cells were co-treated with the Src family kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 µM) or MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM); a recombinant human MIF (rhMIF, 150 ng/mL) condition was also included. (A–D) ELISA quantification of MMP1 (A), MMP2 (B), MMP9 (C), and MT1-MMP (D) protein levels (ng/mL). (E–H) Ratios of MMP1/TIMP1 (E), MMP2/TIMP2 (F), MMP9/TIMP1 (G), and MT1-MMP/TIMP2 (H), calculated from ELISA values and expressed as percentage relative to untreated control (set to 100%). Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

WISP1 regulates NDRG1 expression and cancer cell viability via Src kinases and MIF. MCF7 cells were treated for 24 h with WISP1 (500 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 µM), MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM), or recombinant human MIF (150 ng/mL). (A) NDRG1 mRNA levels quantified by qPCR, normalized to GAPDH, and expressed relative to untreated cells (control). (B) Western blot analysis of NDRG1 protein; α-tubulin served as a loading control. Densitometric quantification of band intensities is shown below the blots. (C) Cell viability assessed by MTT assay. Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

WISP1 regulates NDRG1 expression and cancer cell viability via Src kinases and MIF. MCF7 cells were treated for 24 h with WISP1 (500 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 µM), MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM), or recombinant human MIF (150 ng/mL). (A) NDRG1 mRNA levels quantified by qPCR, normalized to GAPDH, and expressed relative to untreated cells (control). (B) Western blot analysis of NDRG1 protein; α-tubulin served as a loading control. Densitometric quantification of band intensities is shown below the blots. (C) Cell viability assessed by MTT assay. Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 7.

Effects of WISP1 and MIF on cancer cell motility. MCF7 cells were treated with WISP1 (500 ng/mL), MIF (150 ng/mL), or pre-treated with the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 µM) or MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM) prior to WISP1 stimulation (A) Migration was assessed by wound-healing assay over 48 h, with images acquired at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h; wound closure is expressed as the percentage of the initial wound area at 0 h. (B) Representative immunofluorescence images of F-actin (phalloidin, green) and nuclei (DAPI, blue) under the indicated treatments; insets show higher-magnification (40X) views highlighting cytoskeletal re-organization. Scale bars, 20 µm. Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 7.

Effects of WISP1 and MIF on cancer cell motility. MCF7 cells were treated with WISP1 (500 ng/mL), MIF (150 ng/mL), or pre-treated with the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 µM) or MIF inhibitor ISO-1 (100 µM) prior to WISP1 stimulation (A) Migration was assessed by wound-healing assay over 48 h, with images acquired at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h; wound closure is expressed as the percentage of the initial wound area at 0 h. (B) Representative immunofluorescence images of F-actin (phalloidin, green) and nuclei (DAPI, blue) under the indicated treatments; insets show higher-magnification (40X) views highlighting cytoskeletal re-organization. Scale bars, 20 µm. Data are mean ± SD from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed as described in Methods (one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, as appropriate). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for qPCR.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for qPCR.

| Gene |

Primer sequence |

Tannealing (oC) |

| CD44s |

F: 5‘-ATA ATA AAG GAG CAG CAC TTC AGG A-3‘

R: 5‘-ATA ATT TGT GTC TTG GTC TCT GGT AGC-3‘ |

60 |

| CD44t |

F: 5′-ATA ATT GCC GCT TTG CAG GTG TAT T-3′

R: 5′-ATA ATG GCA AGG TGC TAT TGA AAG CCT-3′ |

60 |

| CD74 |

F: 5′-TGC ATT CAC ATT TGT GCT GTA G-3′

R: 5′-TGT ACA GAG CTC TCC ACG GCT G-3′ |

60 |

| E-Cadherin |

F: 5‘-TAC GCC TGG GAC TCC ACC TA-3‘

R: 5‘-CCA GAA ACG GAG GCC TGA T-3‘ |

57 |

| Fibronectin |

F: 5‘-CAT CGA GCG GAT CTG GCC C-3‘

R: 5‘-GCA GCT GAC TCC GTT GCC CA-3‘ |

57 |

| GAPDH |

F: 5′-AGG CTG TTG TCA TAC TTC TCA T-3′

R: 5′-GGA GTC CAC TGG CGT CTT-3′ |

57 |

| HAS-1 |

F: 5’-GGA ATA ACC TCT TGC AGC AGT TTC-3’

R: 5’-GCC GGT CAT CCC CAA AAG-3’ |

61 |

| HAS-2 |

F: 5’-TCG CAA CAC GTA ACG CAA T-3’

R: 5’-ACT TCT CTT TTT CCA CCC CAT TT-3’ |

57 |

| HAS-3 |

F: 5’-AAC AAG TAC GAC TCA TGG ATT TCC T-3’

R: 5’-GCC CGC TCC ACG TTG A-3’ |

61 |

| Hyal1 |

F: 5’-GAT TGC AGT GTC TTC GAT GTG GTA-3’

R: 5’-GGG AGC TAT AGA AAA TTG TCA TGT CA-3’ |

61 |

| Hyal2 |

F: 5’-CTA ATG AGG GTT TTG TGA ACC AGA ATA T-3’

R: 5’-GCA GAA TCG AAG CGT GGA TAC-3’ |

61 |

| MIF |

F: 5′-CCG GAC AGG GTC TAC ATC AAC TAT TAC-3′

R: 5′-TAG GCG AAG GTG GAG TTG TTC C-3′ |

60 |

| MMP-1 |

F: 5′-TGT GAC CTC CAT CCC CAA CT-3′

R: 5′-AAC TCA GGT CAT CTT CTG TCC GT-3′ |

57 |

| MMP-2 |

F: 5′-ACT GTT GGT GGG AAC TCA GAA G-3′

R: 5′-CAA GGT CAA TGT CAG GAG AGG-3′ |

57 |

| MMP-9 |

F: 5‘-TTC CAG TAC CGA GAG AAA GCC TAT-3‘

R: 5‘-GGT CAC GTA GCC CAC TTG GT-3‘ |

57 |

| MT1-MMP |

F: 5′-ACT GTT GGT GGG AAC TCA GAA G-3′

R: 5′-CAA GGT CAA TGT CAG GAG AGG-3′ |

57 |

| TIMP-1 |

F: 5‘-CGC TGA CAT CCG GTT CGT-3‘

R: 5‘-TGT GGA AGT ATC CGC AGA CAC T-3‘ |

59 |

| TIMP-2 |

F: 5‘-GGG CAC CAG GCC AAG TT-3‘

R: 5‘-CGC ACA GGA GCC ATC ACT-3‘ |

60 |

| TMEM2 |

F: 5‘-GGAATAGGACTGACCTTTGCCAG-3‘

R: 5‘-TTCTGACCACCCTGAAAGCCGT-3‘ |

57 |

| Vimentin |

F: 5‘-GGC TCG TCA CCT TCG TGA AT-3‘

R: 5‘-GAG AAA TCC TGC TCT CCT CGC-3‘ |

60 |