1. Introduction

The Web has become a participatory place where everyone can contribute and interact with others [

1], in health in particular [

2,

3]. Facebook currently has 3.07 billion monthly active users worldwide, with 5.17 billion social media users globally, representing 59.38% of the total social media population. The analysis of online social networks such as Facebook in health research has grown markedly over the last 10–15 years [

4,

5]. For professionals, one reason for this growth is that social network research is invaluable for understanding care delivery such as how clinicians communicate, adopt new practices, collaborate, learn together and seek face-to-face advice on work related issues [

6,

7,

8]. In the same way, this analysis is relevant for healthcare organizations in order to improve communication to drive transformative change in the health service through informing choice and improving quality [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. For patients, virtual communities on-line succeed when there is a ’intrinsic desire’ to communicate and share health knowledge and experiences within the community [

15], in particular for rare diseases [

16]. Patients are organizing themselves in groups, sharing observations, and helping each other, although there is still little evidence of the effectiveness of these online communities on people’s health [

17,

18,

19]. Although people’s natural social network played an important role for emotional support, sometimes people chose not to involve their family, but instead interact with peers online because of their perceived support and ability to understand someone’s experience, and to maintain a comfortable emotional distance.

However, very few studies have looked at the content exchanged on these Facebook groups, particularly for the amelogenesis imperfecta (AI), especially in west Europe such as France.

1.1. Amelogenesis Imperfecta (AI) and Its Consequences

Amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) is a rare genetic disorder that affects the development and structure of tooth enamel in both primary (baby) and permanent teeth (

Figure 1). It leads to unusually thin, soft, discolored, or missing enamel, resulting in fragile, sensitive, and prone to wear or breakage. AI arises from mutations in a variety of genes associated with enamel formation, including AMELX, ENAM, MMP20, KLK4, FAM83H, WDR72, and others. These mutations alter enamel matrix production, mineralization, or maturation, leading to defective enamel [

20].

Individuals with AI may experience [

21] discolored teeth (yellow, brown, mottled), enamel fragility, resulting in rapid wear, chipping or breakage, tooth sensitivity to temperature and physical stimuli, increased risk of cavities, inflammation, gingival problems, and malocclusions of the occlusal system, such as open anterior bite (seen in 24–60\% of cases). The diagnosis of AI is based on family history and pedigree analysis, clinical dental examination, assessment of enamel appearance and thickness, radiographs, to evaluate enamel- dentin contrast and structure. In some cases, genetic testing can confirm specific gene mutations.

If AI has several impacts on physical dimensions such as pain, enamel fragility, resulting in rapid wear, chipping, or breakage, tooth sensitivity to temperature and physical stimuli, higher risk of cavities, inflammation, gingival issues, and occlusal problems, malocclusions, psychological impacts are also crucial.

A series of studies seem to demonstrate that people with AI report significantly lower quality of life than healthy controls, particularly due to aesthetics, tooth sensitivity, pain, and functional problems [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Patients report concerns about aesthetics, hypersensitivity, function, and general impact on well-being and social interaction. In particular, AI causes social anxiety and avoidance for patients who experience higher social distress, avoidance behavior, and discomfort about their oral condition compared to controls [

28]. Younger patients tend to show higher fear of negative evaluation [

29] and a UK survey conducted with 60 patients aged 5–17, 76\% show that older patients were also dissatisfied with their appearance and have difficulties with social awareness (fear of comments, self-consciousness) [

30]. The same impact of AI on self-esteem and social awareness has been found in 41 adult patients (aged 18-45 years) [

27]. And a 15-year follow-up of cases showed that untreated AI could cause emotional fatigue, motivation issues, and complex relationships with healthcare providers, highlighting the chronic psychological burden without proper care [

31].

Moreover, children and adolescents with aesthetic-related dental malformations such as AI are potential targets for bullies because a child’s smile reveals important aspects of their quality-of-life and how s/he interacts in his/her environment. For instance, one of the clinical cases presented in their paper, [

32] noticed the following case related to a 10-year-old female with AI: The child’s dental appearance was a source of teas- ing, especially at school. The patient was discriminated by the classmates at the break time and during group activities. The discriminatory behavior lasted for months and resulted in low learning performance, low self-esteem and introspectiveness. Negative comments about her teeth were routine, hindering the child’s social interaction. The school psychologist noticed that many embarrassing situations occurred due to the appearance of her teeth". A recent study confirms this strong relationship between malocclusion or structural defects and exposure to bullying among young adolescents [

33].

Other studies tend to show that AI can have negative impacts of psychological well-being of mothers and fathers of young patients with AI [

24,

34,

35], parents expressing feelings associated with passing on a hereditary disorder, related to guilt/shame. These studies support the need for emotional support for mothers and fathers who receive treatment for AI. In other words, psychological aspects of quality of life, which is a common feature in patients suffering from many kinds of enamel anomalies, are very important and can affect the life of all patients, from childhood to the elderly. Structural dental abnormalities and severe malocclusion should be managed, among others, for psychological questions because they crystallize loss of self-confidence and increase the risk of bullying for children and adolescents [

28,

29,

36]. Because low self-esteem, social anxiety, and emotional distress are commonly reported, AI causes substantial emotional and psychological impacts, particularly in children and teens. Early, empathetic, and multidisciplinary care (including psychological and social support) greatly reduces long-term harm. Patient testimonials reinforce the need for aesthetic and functional treatment, not just for oral health but also for emotional well-being.

1.2. Advantages of Online Social Network for Patients

Facebook groups have been adapted to form support groups for people with chronic disease (e.g.,[

37,

38,

39]) and for rare disease (e.g.,[

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]). Facebook allows patients to meet, discuss, and relate. This online social network is free and highly accessible via computer or smartphone. It is no wonder that Facebook groups are popular with patients. There is measurable value in the benefit of social support. Providing adequate social support for patients with rare diseases is likely to benefit patients, not only with subjective assessment of quality of life, but with objective measures of disease progression and severity. Facebook enhances support group accessibility for parents of children with rare diseases. Group participants perceive a reduction and elimination of distance, a common challenge in rare disease, and Facebook support groups create an environment of perceived privacy. More precisely, the analysis of online Facebook content can have several advantages:

Access to genuine, unprompted patient perspectives. Patients, life science industry and regulatory authorities are united in their goal to reduce the disease burden of patients by closing remaining unmet needs. Patients have, however, not always been systematically and consistently involved in the drug development process. Recognizing this gap, regulatory bodies worldwide have initiated patient-focused drug development (PFDD) initiatives to foster a more systematic involvement of patients in the drug development process and to ensure that outcomes measured in clinical trials are truly relevant to patients and represent significant improvements to their quality of life. Patients often share honest, detailed personal experiences—both emotional and physical—on Facebook and forums. These candid insights reveal what truly matters to them. Such organic conversations provide access to the “lay perspective,” capturing daily challenges, fears, treatment outcomes, and unmet needs that traditional surveys or clinical settings may miss [

45].

Identifying gaps in patient support and communication. Comment analysis helps uncover frequently asked questions, misconceptions, or frustrations among patients. For instance, the analysis of community exchanges threads shows which concerns recur most often, guiding the development of more relevant content, targeted educational materials, and improved support services. Patients and family members in rare disease social media groups appear interested in engaging with genetic counselors through social media [

46], particularly for individualized support. This form of engagement on social media is not meant to replace the current structure and content of genetic counseling (GC) services, but genetic counselors could more actively use social media as a communication tool to address gaps in knowledge and awareness about genetics services and gaps in accessible patient information.

Real-time insights and emerging trend detection. Unlike traditional feedback methods, social media comments arrive instantly—giving healthcare organizations a near real-time “pulse” on how patients feel about treatments, services, or public health issues. This allows for faster response to misinformation, sudden sentiment changes, or emerging health concerns.

Enhancing patient engagement [

5,

47]. Actively monitoring and responding to Facebook comments demonstrates that caregivers and organizations are listening and care, which builds trust. Engaging with comments—especially addressing negative feedback—can improve reputation and even boost content reach on platforms like Facebook.

Quantifying sentiment and satisfaction [

48,

49]. Sentiment analysis tools applied to Facebook data can help measure patient satisfaction, gauge overall sentiment trends, and spot early signs of issues. Studies have shown that hospitals with active Facebook engagement often receive higher patient satisfaction and recommendation rates.

Guiding product development and healthcare policy [

50,

51]. For pharmaceutical companies and drug developers, insights from Facebook can help inform patient- centric medicine development. It enables identification of unmet needs, emotional impact of diseases, treatment preferences, and real-world patient priorities—data which regulatory agencies increasingly view as essential.

Cost-effective and scalable feedback channel [

14,

52]. Collecting feedback via social media is much more scalable and less resource-intensive than focus groups or in-person surveys. It allows organizations to process large volumes of feedback continuously, enabling more agile decision-making.

Anonymity on social networking platforms such as Facebook can foster the expression of more intimate, personal, or emotionally charged content. When users feel less exposed to judgment or social consequences—especially in closed or private groups—they are often more willing to share sensitive experiences, personal struggles, or opinions they might otherwise withhold in face-to-face settings. This dynamic is particularly relevant in studies focused on health, stigma, or emotional well-being, where participants may use online spaces as safe environments for self-disclosure. In the context of this study, the semi-anonymous nature of the Facebook group likely contributed to the emergence of rich, affective narratives, enhancing the depth and authenticity of the collected corpus. As such, the platform’s affordances play a significant role in shaping the content and tone of user discourse and must be considered when interpreting the results of qualitative analyses.

So, Facebook enhances support group accessibility for parents of children with rare diseases [

42,

43] such as AI. Group participants perceive a reduction and elimination of distance, a common challenge in rare disease, and Facebook support groups create an environment of perceived privacy. The group’s privacy setting can be a critical factor for active support group participation. Sharing personal information and pictures on Facebook is very common among group participants, which shows the importance of discussing and protecting children’s privacy rights in this context. Because of the nature of rare diseases with affected individuals being widely geographically dispersed, finding an in-person/offline support group itself can be a challenge. Affected individuals therefore turn to social networking platforms such as Facebook for online support groups.

1.3. Limitations of Previous Studies and Our Objectives

Although all these previous studies have yielded valuable insights, several limitations remain, highlighting the need for further research specifically focused on amelogenesis imperfecta: To date, no study has been conducted with French patients and their families, which represents a significant gap in the literature and limits our understanding of how amelogenesis imperfecta is experienced and managed within the French healthcare and cultural context. The treatment of amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) varies significantly in cultural and healthcare settings [

22,

24,

53,

54]. In high- income countries, treatment often involves early diagnosis, multidisciplinary care (including pediatric dentists, orthodontists, prosthodontists, and geneticists), and access to advanced restorative materials and techniques such as full crowns, veneers, or implants. In contrast, in lower-resource settings, the treatment of AI may be limited by lack of access to specialized care, financial constraints, and low public awareness of the condition. Moreover, cultural perceptions of dental aesthetics and pain tolerance can influence how patients seek care and adhere to treatment plans. Finally, stigma and psychological distress related to visible dental anomalies may be addressed differently across societies, with some cultures showing greater sensitivity to facial appearance than others. These disparities highlight the importance of context-sensitive, equitable treatment strategies and the need for global collaboration to ensure that patients with AI receive timely, adequate care regardless of their cultural or economic background.

Moreover, although several authors acknowledge that Facebook content can offer valuable insights into the actual needs and expectations of patients, no rigorous study has yet been conducted to systematically analyze this material [

41].

While data collection in this field is often unidimensional (focusing primarily on economic, educational, or occupational variables), our present study is grounded in a multidimensional approach that integrates semantic, thematic, and contextual analyses to more fully capture the complexity of patient experiences.

In other words, the main objective of our study is to gain a deeper understanding of the actual needs and psychological factors affecting French patients living with amelogenesis imperfecta (AI), through a rigorous analysis of all the contents exchanged within a dedicated Facebook group for patients and their members family.

2. Materials and Methods

To explore the actual needs and mental representations of French patients and their families regarding amelogenesis imperfecta, we conducted a semantic and thematic analysis of a corpus derived from a dedicated Facebook group. Lexical proximity between key terms was examined using similarity analysis, while thematic patterns were identified through a Descending Hierarchical Classification (DHC) based on the Reinert method. The analysis was performed on a corpus comprising 881 texts, totaling 39,647 words and 3,276 unique word forms.

2.1. The French Facebook Group Amelogenesis Imperfecta

The French Facebook group Amelogenesis imperfecta (

https://www.facebook.com/groups/258243454375660/) was created in August 2016, are 535 members and the association was created two years later (in March 2018). This French Facebook group is private and is available as a safe space and resource for the patients and their families to have the conversations that matter to them.

The text in the homepage is the following: "Information and exchange on amelogenesis imperfecta - for patients and their families. In this group, people closely affected by the disease will be able to share information, testify, support and advise each other. We hope they will also be able to join forces to raise awareness of the disease, better defend their rights and raise public awareness".

2.2. Design and Tools

Thematic analysis is one of the most prominent methods used for the analysis of message content [

55,

56,

57]. Thematic analysis assumes that the recorded messages themselves (

i.e., the texts) are the data, and codes are developed by the investigator during close examination of the texts as salient themes emerge inductively from the texts. For our study, two specific software have been used (

Figure 2).

2.2.1. Data Extraction

The corpus was extracted using a custom-designed software called TEXTRA©, specifically created for the purposes of this study. Developed by a research team at the University of Lorraine, TEXTRA© was designed to enable the automatic extraction of all data from a Facebook group. This includes the retrieval of posts, comments, replies to comments, and user-related metadata. By capturing the full structure of interactions within the group—encompassing both content and engagement dynamics—TEXTRA© ensured a comprehensive and faithful representation of the discursive material shared by members. Prior to the development of this innovative tool, corpus extraction had to be performed manually, which was both time- consuming and prone to errors. TEXTRA© thus represents a significant methodological improvement, enhancing both efficiency and data accuracy.

2.2.2. Data Analysis

The second software used is IRaMuTeQ©: This software, developed by a research team in Toulouse University, allows for detailed statistical analysis of the text corpus, including classic text analysis, specificity analysis, similarity analysis, and word cloud. IRaMuTeQ© is a GNU GPL(v2) licensed software that provides users with statistical analysis on text corpus and tables composed by individuals/words [

58]. It is based on R software and on the Python language. This software provides the users with different text analyses, either simple ones, such as the basic lexicography related to lemmatization and word frequency; or more complex ones such as descending hierarchical classification, post- hoc correspondence factor analysis and similarity analysis. In our study, two text analyses provided by IRaMuTeQ© have been used:

Similarity analysis. This analysis, based on graph theory, is often used by social representations researchers. It allows to identify the words co-occurrences, providing information on the words connectivity thus helping to identify the structure of a text corpus content. It also allows to identify the shared parts and specificity according to the descriptive variables identified in the analysis.

Method of Descending Hierarchical Analysis (DHA). The content and text segments are clustered according to their vocabularies and distributed according to the reduced forms frequencies. Using matrices that cross reduced forms with textual segments, the DHA method allows you to obtain a definitive classification. It is aimed at obtaining clusters with similar vocabulary within, but different from other segments. A dendrogram will be dis- played showing clusters relations. The software calculates descriptive results of each cluster conforming to its main vocabulary (lexic) and words with asterisk (variables). Furthermore, it provides the users with another way of presenting data, derived from a correspondence factor analysis. Based on the chosen clusters, the software calculates and provides the most typical TS of each cluster, giving context to them.

2.3. Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Reims hospital (Study Protocol No. RN25016).

3. Results

To better understand the effective needs, opinions and representation of patients and families interested in amelogenesis imperfecta, an analysis of the semantic structure of the corpus issued from the Facebook group related to the French association and a thematic analysis based on a Descending Hierarchical Classification using the Reinert method analysis were performed. The analysis was based on a corpus of 881 texts, totaling 39,647 words and 3,276 unique forms.

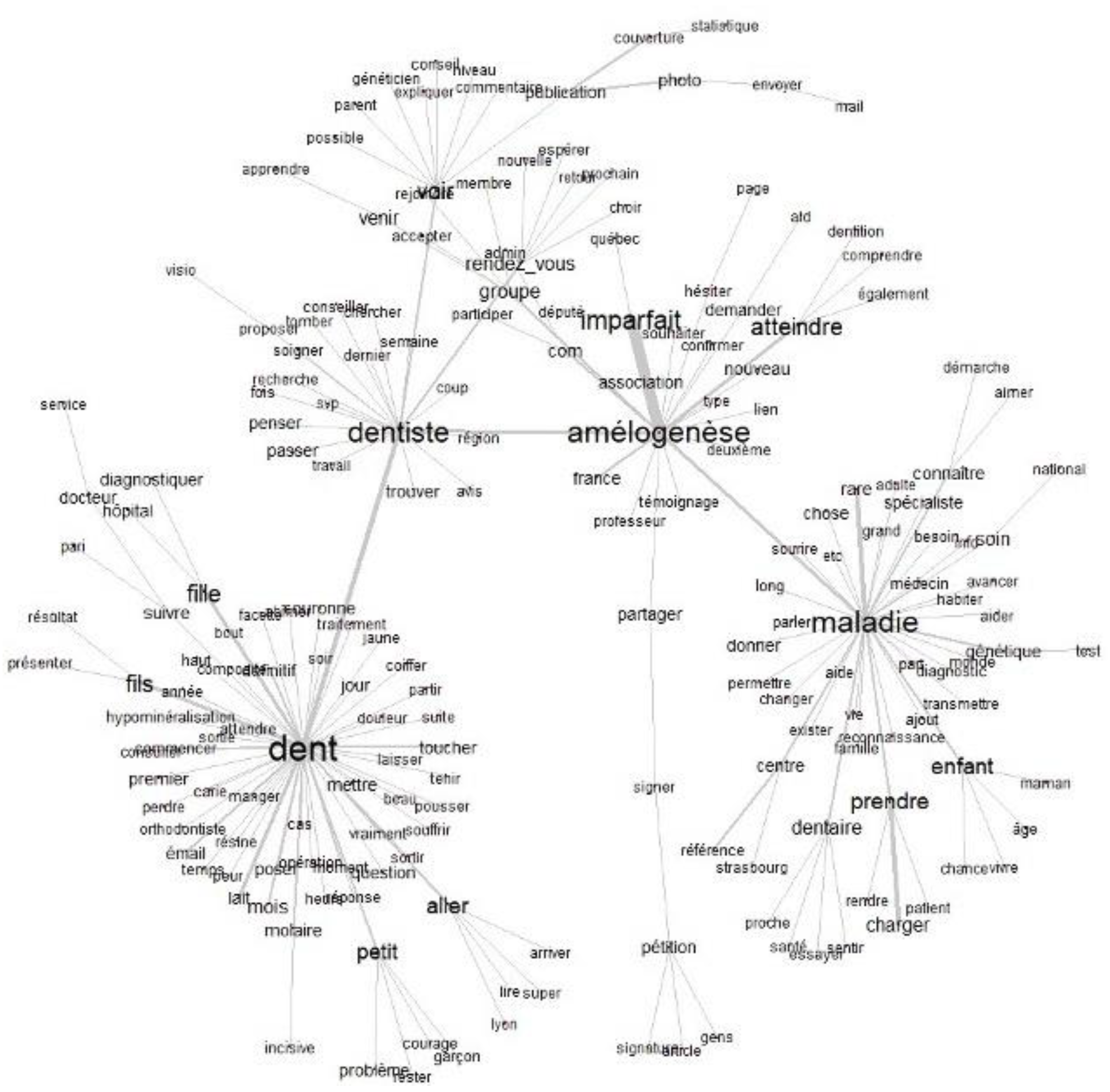

3.1. Similarity Analysis and Clustering

The similarity analysis conducted using IRaMuTeQ© to visualize significant co-occurrences between lexical forms in the corpus extracted from the French Facebook group amelogenesis imperfecta show several interesting results. The resulting graph (

Figure 3) reveals three well-defined lexical clusters that reflect how participants discuss and experience amelogenesis imperfecta (AI):

The word “dent” (tooth) forms the central lexical node, with numerous connections to everyday terms such as “fils” (son), “fille” (daughter), “mettre” (put), “perdre” (lose), “petit” (small), “problème” (problem), indicating real-life, family-centered experiences related to dental symptoms. This cluster is strongly linked to “dentiste” (dentist), which is in turn connected to terms like “traite- ment” (treatment), “rendez-vous” (appointment), “avis” (opinion), “diagnostiquer” (diagnose), highlighting the central role of healthcare and professional consultations;

A second semantic hub is organized around “maladie” (disease), connected to “génétique” (genetic), “enfant” (child), “rare”, “connaître” (to know). This reflects a medicalized view of the condition, often framed in terms of inheritance, diagnosis, and rarity. The presence of terms such as “pétition” (petition), “centre” (center), “changer” (change), “donner” (give) suggests a broader collective or advocacy dimension, possibly parental or patient-led efforts seeking recognition or policy change;

Finally, the word “amélogenèse” (amelogenesis) appears in direct connection with “imparfait” (imperfect), “atteindre” (affect), “association”, reflecting the shared awareness of the condition’s name and the need for information-sharing and support, as seen in related terms like “photo”, “groupe”, “partager” (share).

Overall, the graph related to the correspondence analysis of clusters highlights a dual discourse structure: one rooted in personal and familial experiences, the other centered on healthcare, diagnosis, and advocacy—typical of narratives surrounding rare and hereditary disorders.

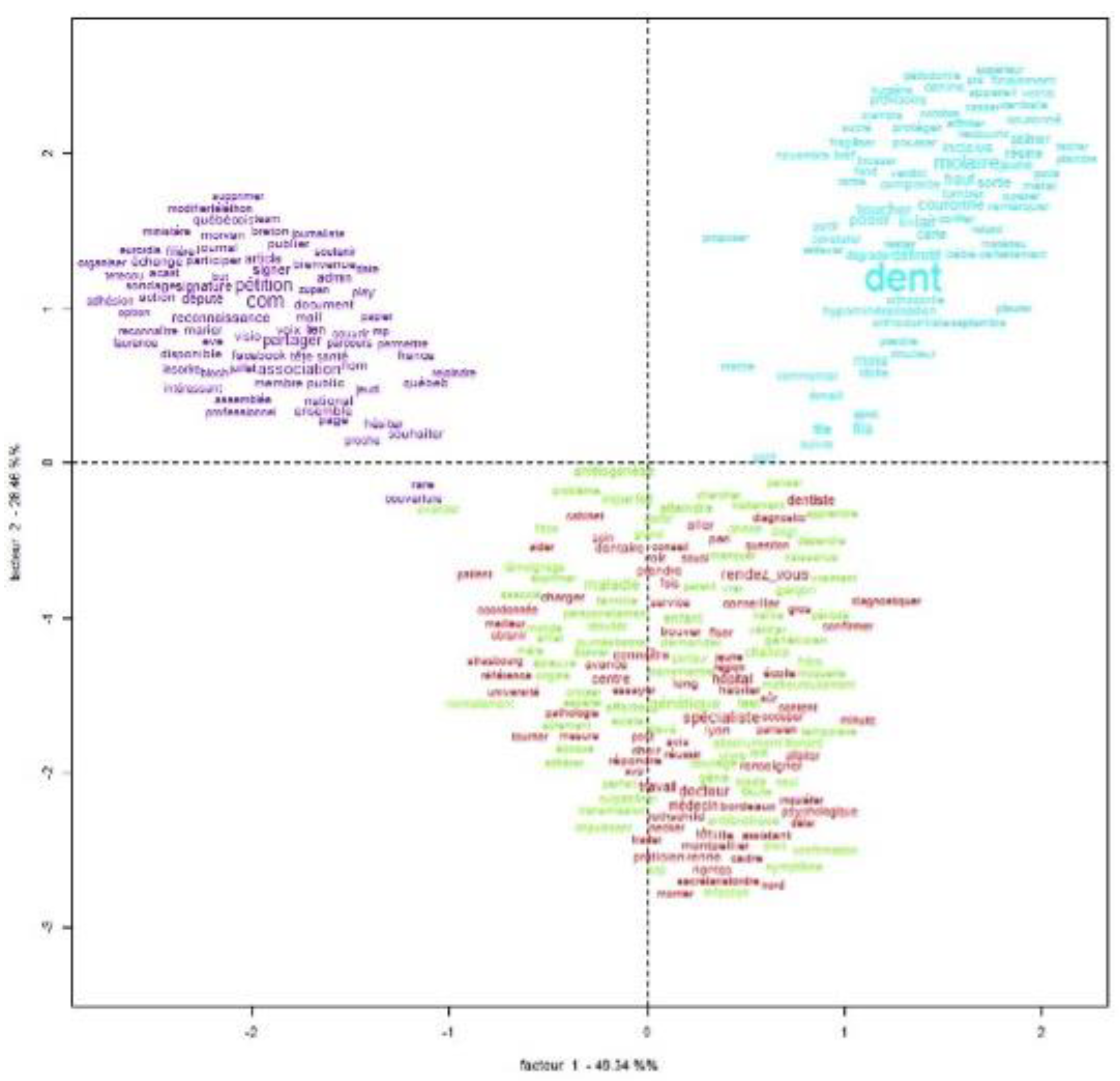

3.2. Correspondence Analysis and Factorization

The correspondence analysis of clusters has two main axes (

Figure 4):

Factor 1 (horizontal axis): Explains 49.34% of the variance. This factor 1 distinguishes Clinical vs. Activist Dimension. The right side (Red/Green/Blue) focuses on clinical, genetic, and symptom-based discourse; the left side (Purple) focuses on community, activism, media, and public communication This axis opposes individual/medical experience to collective/social mobilization;

Factor 2 (vertical axis): Explains 23.26% of the variance. This factor 2 distinguishes Technical vs. Personal/Descriptive Dimension. The top (blue) is related to lexicon rich in concrete dental symptoms and care (e.g., "molaire", "résine", "douleur"); the bottom (red/green) emphasizes institutional, procedural, or psychological aspects (e.g., "rendez-vous", "médecin", "traitement", "hôpital").

Together, these two axes explain 72.6% of the variance which is a solid basis for interpretation. The correspondence analysis highlights two primary axes organizing the corpus’ discourse. The first axis (49.34%) distinguishes a medical and individual discourse — ranging from personal symptoms (Class 3) to institutional navigation (Class 1), from a collective, activist discourse centered on public visibility and community mobilization (Class 4). The second axis (23.26%) separates a technically descriptive discourse focused on dental symptoms from more abstract, clinical, or genetic considerations (Classes 1 and 2). Notably, the activist class (Class 4) is the most distinct, forming its own quadrant and suggesting that community-driven narratives are lexically and semantically distant from medically oriented ones. Class 2 occupies a central position, bridging scientific understanding with patient-family experience.

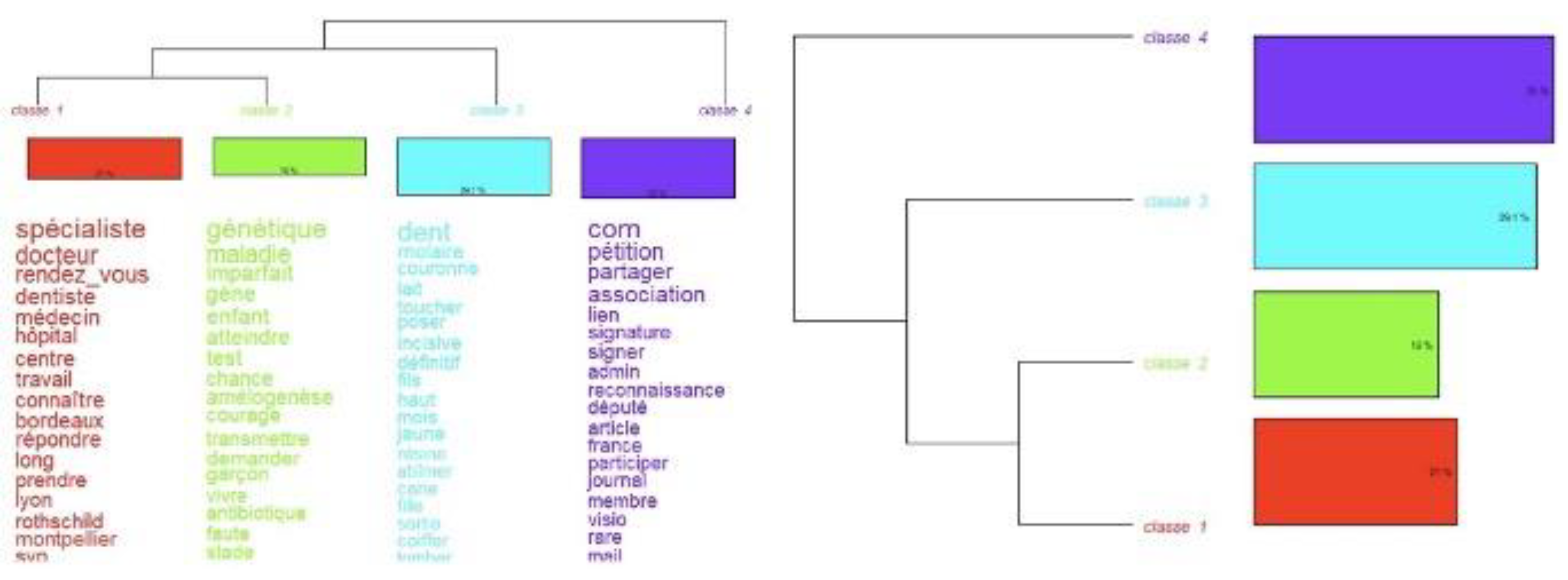

3.3. Thematic Analysis of Comments and Exchanges

The Descending Hierarchical Classification dendrogram from IRaMuTeQ© (

Figure 5), based on the Reinert method analysis, where the corpus is divided into thematically consistent lexical classes based on word co-occurrence, shows four disinct classes:

Class 1 (in red): Medical Professionals and Access to Care (21%), with the following top words: "spécialiste", "docteur", "rendez-vous", "dentiste", "médecin", "hôpital", "centre", "travail", "connaître", "répondre". This class reflects a discourse focused on accessing the healthcare system: it centers around interactions with special- ists, doctors, and institutions. The presence of location- specific terms (e.g., Lyon, Bordeaux, Montpellier) and verbs like répondre, prendre suggest issues related to appointments, delays, and logistics. We propose to label this class "Healthcare navigation and access difficulties";

Class 2 (in green): Genetic and Clinical Nature of the Disease (19%), with the following top words: "génétique", "maladie", "imparfaite", "gène", "enfant", "atteindre", "test", "amélogenèse", "transmettre". This class reflects a biomedical perspective of the condition. It includes genetic terms and refers to the transmission, testing, and emotional impact of amelogenesis imperfecta. Words like "chance", "vivre", "courage" suggest some existential or emotional framing of the diagnosis. We propose to label this class "Genetic disease framing and family impact";

Class 3 (in blue): Description of Dental Symptoms (29.1%), with the following top words: "dent", "molaire", "couronne", "lait", "toucher", "poser", "incisive", "fils", "carie", "abîmer", "jaune". This is the most concrete and symptom-centered class, focusing on dental manifestations and terminology. It includes references to deciduous teeth ("lait"), materials ("résine"), stages ("sortie"), and treatments ("couronne"). This suggests parents or individuals are detailing clinical signs and treatment attempts. we propose to label this class "Dental symptoms and treatment experiences";

Class 4 (in purple): Advocacy, Community, and Visibility (31%), with the following top words: "com", "pétition", "partager", "association", "signature", "signer", "reconnaissance", "député", "participer", "article". This class stands apart as a collective, activist discourse. It includes words related to online engagement, petitioning, awareness-raising, and media participation. The use of "com", "admin", "signature", "député" suggests efforts to gain recognition for the disease and mobilize institutional support. We propose to label this class "Community mobilization and advocacy".

Classes 3 and 4 are the most distinct, i.e., they split early in the tree. Classes 1 and 2 are closer lexically, suggesting that navigating the medical system and understanding the genetic basis of the disease often appear together in the same segments of discourse.

4. Discussion

The correspondence analysis performed on the content extracted from the Facebook group for French patients and families concerned by amalogenesis imperfecta (AI) provides a meaningful structural interpretation of the corpus, with the two primary axes accounting for 72.6% of the total variance, an analytically robust foundation. The first axis (49.34%) reveals a fundamental contrast between discourses rooted in medical and individual experience (notably Classes 1 and 3) and those centered on collective action and public advocacy (Class 4). This suggests a divergence between personal narratives—focusing on symptoms, care logistics, and medical engagement—and a broader discourse aimed at visibility, mobilization, and institutional recognition.

The second axis (23.26%) differentiates a technically descriptive lexicon, particularly related to dental manifestations (Class 3), from a more abstract, clinical, and genetic discourse (Classes 1 and 2). This gradient underscores the multifaceted nature of the corpus, ranging from concrete symptomatology to conceptual and etiological framing of the condition.

The Descending Hierarchical Classification (DHC) of the corpus revealed four distinct lexical classes. Class 1 ("Healthcare navigation and access difficulties", 21%) reflects a discourse focused on navigating the healthcare system, including interactions with specialists and logistical concerns around appointments. Class 2 ("Genetic disease framing and family impact", 19%) centers on the biomedical and genetic framing of amelogenesis imperfecta, highlighting issues of heredity, testing, and emotional responses to diagnosis. Class 3 ("Dental symptoms and treatment experiences", 29.1%) is grounded in concrete descriptions of dental symptoms and treatment experiences, including references to specific types of teeth and procedures. Finally, Class 4 ("Community mobilization and advocacy", 31%) captures a more collective discourse of advocacy and awareness, with participants mobilizing through petitions, online communities, and institutional outreach to increase the visibility of the disease.

The close lexical proximity of Classes 1 and 2 highlights how patients and families often combine discussions about accessing medical care with understanding the genetic nature of the disease. This suggests that interventions or information resources should address both practical healthcare navigation and biomedical education simultaneously to better support affected individuals. Class 3, focusing on dental symptoms and treatment experiences, represents the most concrete discourse. This indicates that lived experience with the physical manifestations of the disease remains a dominant concern for individuals and caregivers, underscoring the need for clear clinical communication and tailored treatment pathways. Finally, the distinct and largest class, Class 4, illustrates the important role of advocacy, awareness-raising, and collective action. This highlights how individuals affected by the condition engage beyond clinical settings to seek recognition, policy change, and social support, pointing to the potential impact of organized patient groups and campaigns.

In other words, "Community mobilization and advocacy" (Class 4) emerges as the most lexically and semantically distinct, occupying its own quadrant and illustrating the unique position of community-driven narratives. In contrast, "Genetic disease framing and family impact" (Class 2) is more centrally located, acting as a conceptual bridge between the scientific discourse and the lived experiences of patients and families. This centrality reinforces the integrative role of genetic and biomedical understanding in making sense of the condition across discursive domains.

Together, these findings emphasize the complexity of patient experiences that span medical, emotional, and social domains. Healthcare providers and policymakers should consider this multi-layered reality when designing services, ensuring they address not only clinical needs but also access challenges and psychosocial support.

5. Conclusions

Collecting data on the actual and concrete needs of patients with rare diseases is essential for improving clinical care, psychosocial support, and health policy planning. As the Web—and social networks such as Facebook—have increasingly become preferred spaces for health-related discussion forums and online communities, they now represent vast and rich sources of patient-generated data [

3]. These digital platforms provide unique access to the lived experiences, expectations, and concerns of individuals who are often underrepresented in traditional research, particularly in the context of rare disease such as amelogenesis imperfecta (AI). The types of emotions most frequently expressed by patients and parents of children with a rare disease include fear, worry, frustration, uncertainty, helplessness, and vulnerability [

10,

59]. Parents often feel dissatisfied with the overall level of support for their child with a rare disease. Affected individuals are often geographically dispersed, because rare diseases, by definition, have a very low prevalence. Therefore, many parents have never come into contact with another parent taking care of a child with a similar condition [

1]. Social isolation and the feeling of being disconnected from society are common experiences [

44]. For many rare diseases, medical and scientific knowledge remains scarce [

2]. At the same time, these diseases are often serious and chronic, thereby increasing psychological, social, economic, and cultural vulnerability. Consequently, parents of children with rare diseases such as AI face substantial challenges and have special supportive care needs.

Building on the findings of this study, the next phase of our research involves designing a survey and conducting semi-structured interviews with a panel of French patients and family members affected by amelogenesis imperfecta (AI), to deepen our understanding of their lived experiences and care expectations. In accordance to [

43], our study confirms that support groups existing on Facebook offer improved social support through befriending other people with similar experiences, learning about the disease, treatments, and coping skills, emotional support and feeling empowered [

60].

Funding

This research was funded by Fondation Maladies Rares, under the Social Sciences and Humanities program (grant agreement No.- SHS-2025-15511).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Reims hospital (Study Protocol No. RN25016).

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Fondation Maladies Rares, under the Social Sciences and Humanities program (grant agreement No.- SHS-2025-15511).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chirumamilla, S.; Gulati, M. Patient education and engagement through social media. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2021, 17, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Khan, A.; Kumar, A. Social media use by patients in health care: A scoping review. Int J Healthc Manag. 2022, 15, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.C.; et al. Needs of people with rare diseases that can be supported by electronic resources: A scoping review. BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e060394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Social media use for health purposes: Systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021, 23, e17917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddy, C.; Hunter, Z.; Mihan, A.; Keely, E. Use of Facebook as part of a social media strategy for patient engagement. Can Fam Physician. 2017, 63, 251–252. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, S.A.; Abidi, S.S.R. Applying social network analysis to understand the knowledge sharing behaviour of practitioners in a clinical online discussion forum. J Med Internet Res. 2012, 14, e1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; et al. Review of social networks of professionals in healthcare settings—where are we and what else is needed? Glob Health. 2021, 17, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan-Dabija, R.A.; Cernomaz, A.; Mihaescu, T.; Filipeanu, D. Developing a successful medical team using WhatsApp™ and social media (1 year follow up). 2019. [CrossRef]

- Francis, T.; et al. Exploring the use of social network analysis methods in process improvement within healthcare organizations: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024, 24, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomare, C.; Long, J.C.; Churruca, K.; Ellis, L.A.; Braithwaite, J. Social network research in health care settings: Design and data collection. Soc Netw. 2022, 69, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Las Heras-Pedrosa, C.; Rando-Cueto, D.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C.; Paniagua-Rojano, F.J. Analysis and study of hospital communication via social media from the patient perspective. Cogent Soc Sci. 2020, 6, 1718578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, A.; Fleming, J.; Powell, J.; Atherton, H. Exploring UK doctors’ attitudes towards online patient feedback: Thematic analysis of survey data. Digital Health. 2020, 6, 2055207620908148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherton, H.; Fleming, J.; Williams, V.; Powell, J. Online patient feedback: A cross-sectional survey of the attitudes and experiences of United Kingdom health care professionals. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2019, 24, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.Y.; et al. Social network analysis of patient sharing among hospitals in Orange County, California. Am J Public Health. 2011, 101, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G.; Powell, J.; Englesakis, M.; Rizo, C.; Stern, A. Health related virtual communities and electronic support groups: Systematic review of the effects of online peer to peer interactions. BMJ. 2004, 328, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, T.A.; Vershaw, S.L.; Conboy, E.; Halverson, C.M. Improving social media-based support groups for the rare disease community: Interview study with patients and parents of children with rare and undiagnosed diseases. JMIR Hum Factors. 2024, 11, e57833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colineau, N.; Paris, C. Talking about your health to strangers: Understanding the use of online social networks by patients. New Rev Hypermedia Multimed. 2010, 16, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, W.; Amuta, A.O.; Jeon, K.C. Health information seeking in the digital age: An analysis of health information seeking behavior among US adults. Cogent Soc Sci. 2017, 3, 1302785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Kong, H. Online health information seeking: A review and meta-analysis. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldred, M.; Savarirayan, R.; Crawford, P. Amelogenesis imperfecta: A classification and catalogue for the 21st century. Oral Dis. 2003, 9, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koruyucu, M.; Bayram, M.; Tuna, E.B.; Gencay, K.; Seymen, F. Clinical findings and long-term managements of patients with amelogenesis imperfecta. Eur J Dent. 2014, 8, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oz, U.; Altug, A.T.; Arikan, V.; Orhan, K. Radiographic evaluation of craniofacial structures associated with amelogenesis imperfecta in a Turkish population: A controlled trial study. Oral Radiol. 2010, 26, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelstrand, S.; Robertson, A.; Sabel, N. Patient-reported outcome measures in individuals with amelogenesis imperfecta: A systematic review. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2022, 23, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pousette Lundgren, G.; Karsten, A.; Dahllöf, G. Oral health-related quality of life before and after crown therapy in young patients with amelogenesis imperfecta. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015, 13, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Gowda, S.; Foster Page, L.; Thomson, W.M. Oral health-related quality of life in Northland Māori children and adolescents with Polynesian amelogenesis imperfecta. Front Dent Med. 2024, 5, 1485419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, T.S.; Vargas-Ferreira, F.; Kramer, P.F.; Feldens, C.A. Impact of traumatic dental injuries on oral health-related quality of life of preschool children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0172235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.; Kelly, A.; O’Connell, B.; O’Sullivan, M. Impact of moderate and severe hypodontia and amelogenesis imperfecta on quality of life and self-esteem of adult patients. J Dent. 2013, 41, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffield, K.D.; et al. The psychosocial impact of amelogenesis imperfecta. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005, 136, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, S.; Almehateb, M.; Cunningham, S.J. How do children with amelogenesis imperfecta feel about their teeth? Int J Paediatr Dent. 2014, 24, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyne, A.; Parekh, S.; Patel, N.; Lafferty, F.; Brown, C.; Rodd, H.; Monteiro, J. Patient-reported outcome measure for children and young people with amelogenesis imperfecta. Br Dent J. 2021, (1-6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentesaux, T.; Rousset, M.; Dehaynin, E.; Laumaillé, M.; Delfosse, C. 15-year follow-up of a case of amelogenesis imperfecta: Importance of psychological aspect and impact on quality of life. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2013, 14, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffel, D.L.S.; et al. Esthetic dental anomalies as motive for bullying in schoolchildren. Eur J Dent. 2014, 8, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broutin, A.; Blanchet, I.; Canceill, T.; Noirrit-Esclassan, E. Association between dentofacial features and bullying from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review. Children. 2023, 10, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, C.; Perera, I.; Jayasooriya, P.; Perera, M. Experiences of mothers of affected children on family impact of amelogenesis imperfecta: Findings of a qualitative explorative study from Sri Lanka. Interventions in Pediatric Dentistry Open Access Journal. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alqadi, A.; O’Connell, A.C. Parental perception of children affected by amelogenesis imperfecta (AI) and dentinogenesis imperfecta (DI): A qualitative study. Dentistry Journal. 2018, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Rodrigues, L.; et al. Oral disorders associated with the experience of verbal bullying among Brazilian school-aged children: A case-control study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020, 151, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, A.D.; Bruckner Holt, C.; Cook, M.; Hearing, S. Social networking sites: A novel portal for communication. Postgrad Med J. 2009, 85, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, J.L.; Jimenez-Marroquin, M.-C.; Jadad, A.R. Seeking support on Facebook: A content analysis of breast cancer groups. J Med Internet Res. 2011, 13, e15–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untas, A.; et al. The associations of social support and other psychosocial factors with mortality and quality of life in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011, 6, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilica, C.; et al. Identifying information needs of patients with IgA nephropathy using an innovative social media–stepped analytical approach. Kidney Int Rep. 2021, 6, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddy, A.; Topf, J. Facebook groups can provide support for patients with rare diseases and reveal truths about the secret lives of patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2021, 6, 1205–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titgemeyer, S.C.; Schaaf, C.P. Facebook support groups for rare pediatric diseases: Quantitative analysis. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2020, 3, e21694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titgemeyer, S.C.; Schaaf, C.P. Facebook support groups for pediatric rare diseases: Cross-sectional study to investigate opportunities, limitations, and privacy concerns. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2022, 5, e31411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprescu, F.; Campo, S.; Lowe, J.; Andsager, J.; Morcuende, J.A.; et al. Online information exchanges for parents of children with a rare health condition: Key findings from an online support community. J Med Internet Res. 2013, 15, e24–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimiano, P.; et al. Patient listening on social media for patient-focused drug development: A synthesis of considerations from patients, industry and regulators. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024, 11, 1274688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabumoto, M.; et al. Perspectives of rare disease social media group participants on engaging with genetic counselors: Mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2022, 24, e42084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Cañadas, J.; Galán-Valdivieso, F.; Saraite-Sariene, L.; Caba-Pérez, C. Committed to health: Key factors to improve users’ online engagement through Facebook. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glivenko, O.; Yaroslavska, O.; Demchuk, A.; Poberezhets, V.; Mostovoy, Y. Use of online questionnaires, social networks and messengers for quick collecting epidemiological data among young people. 2020.

- Kondylakis, H.; et al. Patient empowerment through personal medical recommendations. Medinfo. 2015, 216, 1117. [Google Scholar]

- David, C.C.; San Pascual, M.R.S.; Torres, M.E.S. Reliance on Facebook for news and its influence on political engagement. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0212263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, Z.A.; Ali, K.I.; Khan, S. Using Facebook for sexual health social marketing in conservative Asian countries: A systematic examination. J Health Commun. 2017, 22, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.; Bessin, M.; Gaymard, S. Social representations, media, and iconography: A semiodiscursive analysis of Facebook posts related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Commun. 2022, 37, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhaiem, M.; Chalbi, M.; Bousaid, S.; Zouaoui, W.; Chemli, M.A. Dental treatment approaches of amelogenesis imperfecta in children and young adults: A systematic review of the literature. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2024, 36, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindunger, A.; Smedberg, J.I. A retrospective study of the prosthodontic management of patients with amelogenesis imperfecta. Int J Prosthodont. 2005, 18, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, P. Advanced research methods for applied psychology. 2018.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K.A. Content analysis and thematic analysis. In: Brough P, editor. Advanced research methods for applied psychology. Routledge; 2018. p. 211-223.

- Mennani, M.; Attak, E. An overview of using IRAMUTEQ software in qualitative analysis designs. In: Principles of conducting qualitative research in multicultural settings. 2024. p. 149-170.

- Pelentsov, L.J.; Fielder, A.L.; Laws, T.A.; Esterman, A.J. The supportive care needs of parents with a child with a rare disease: Results of an online survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2016, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delisle, V.C.; et al. Perceived benefits and factors that influence the ability to establish and maintain patient support groups in rare diseases: A scoping review. Patient. 2017, 10, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).