1. Introduction

Trichotillomania, or hair-pulling disorder, is a chronic condition characterized by recurrent, difficult-to-control urges to pull out one’s own hair. It is associated with significant distress, functional impairment, and psychosocial burden. Although often underdiagnosed, epidemiological estimates suggest that it affects approximately 1–2% of the population (Christenson et al., 1991; Grant et al., 2017). Despite its impact, research on trichotillomania remains limited compared to other psychiatric or behavioral conditions, and systematic data from Spanish-speaking populations are especially scarce.

Previous studies have described key features of the disorder, including its frequent onset in childhood or adolescence, the reinforcing role of emotions such as anxiety and stress, and the persistent difficulties in achieving long-term remission. However, most existing work has focused on clinical samples in North America or Europe, often with small participant numbers and without systematically examining how emotional, developmental, and therapeutic factors interact in community-based contexts. In addition, very few studies have explored how digital support environments such as social networks contribute to awareness, emotional regulation, or help-seeking among individuals living with trichotillomania.

The rise of social software platforms has created new spaces where individuals affected by underrecognized conditions can share experiences, seek emotional support, and access health-related knowledge. In the case of trichotillomania, online support groups on platforms like Facebook and WhatsApp have become key ecosystems of peer learning and self-help, particularly in regions where specialized clinical services are limited. These digital communities not only facilitate communication and solidarity but also provide a valuable opportunity for inclusive and community-based research.

To address these gaps, the study analyzed responses from 198 Spanish-speaking individuals recruited through online support groups dedicated to trichotillomania. The goal was to examine the emotional, developmental, therapeutic, and social-digital dimensions of the disorder through one of the largest community-based datasets collected to date in this population.

This study addresses four central research questions:

How do emotional triggers relate to the frequency and persistence of hair-pulling episodes?

How does age of onset influence the severity and trajectory of trichotillomania?

What is the relationship between treatment type and remission rates in trichotillomania?

How does participation in online support communities (Facebook and WhatsApp) influence perceived helpfulness and emotional support among individuals with trichotillomania?

By integrating these four dimensions, this research aims to contribute a multidimensional understanding of trichotillomania that connects emotional, developmental, and clinical factors with the growing role of social-digital ecosystems in mental health support and knowledge sharing.

2. Theoretical Framework

Trichotillomania, classified in the DSM-5 as a body-focused repetitive behavior (BFRB), is conceptualized as a multifactorial condition involving emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and neurobiological components. Its theoretical foundations have evolved from early habit-formation models toward more integrative perspectives that emphasize emotion regulation, developmental vulnerability, and contextual learning mechanisms.

2.1. Emotional Regulation Perspective

The emotional regulation model provides one of the most widely accepted explanations for trichotillomania. It proposes that hair-pulling serves as a maladaptive way to manage internal tension or negative affect, especially anxiety and stress. Episodes often begin with a feeling of discomfort, restlessness, or emotional buildup, followed by a sense of relief or pleasure immediately after pulling (Diefenbach et al., 2008; Franklin et al., 2011). This cycle reinforces the behavior and helps explain why individuals continue pulling despite negative consequences.

From a neurobiological standpoint, researchers have identified irregularities in the frontostriatal circuits that are responsible for impulse control and reward processing (Chamberlain et al., 2009). These findings support the idea that trichotillomania is not simply a habit but part of a broader pattern of emotional dysregulation and difficulty delaying gratification.

In behavioral terms, the act of hair-pulling becomes negatively reinforcing because it temporarily reduces unpleasant emotional states. Over time, this relief strengthens the habit, turning emotional discomfort into a consistent trigger. The presence of positive reinforcement, such as pleasure or sensory satisfaction, further complicates the cycle, combining relief-seeking and reward-driven motivations.

This perspective directly supports the study’s first research question, which examines how emotional triggers relate to the frequency and persistence of hair-pulling episodes. By analyzing how anxiety, stress, boredom, loneliness, and other emotional contexts correlate with pulling intensity, this framework helps clarify the affective mechanisms that sustain trichotillomania across different levels of severity.

2.2. Developmental and Lifespan Factors

Trichotillomania typically begins in childhood or adolescence, during stages of high emotional reactivity and neurodevelopmental change. Several studies have identified the ages between 6 and 15 as the most common period of onset, which coincides with major psychological and social transitions such as increased academic pressure, identity formation, and sensitivity to stress (Christenson et al., 1991; Keuthen et al., 2007). These developmental characteristics may explain why early onset often leads to long-term behavioral patterns that are difficult to interrupt.

The developmental model suggests that hair-pulling behaviors may emerge as early strategies for managing anxiety, boredom, or emotional tension. If not addressed early, these behaviors can become ingrained as automatic responses to distress. Adolescence appears particularly critical because of its combination of heightened emotional intensity and increasing cognitive awareness, which may solidify the habit through repeated reinforcement.

While childhood and adolescent onset remain the most prevalent, some recent studies have also reported adult-onset cases that appear less common but often more intense (Grant et al., 2017). The present study builds on this observation by identifying a similar late-onset subgroup in its own dataset, characterized by higher pulling frequency despite smaller representation. This suggests that trichotillomania may follow multiple developmental trajectories rather than a single uniform pathway, with onset age interacting with environmental context and emotional regulation capacity.

These perspectives form the foundation for the study’s second research question, which examines how age of onset influences the severity and persistence of trichotillomania. By comparing developmental stages and current symptom patterns, the analysis aims to clarify whether early or late onset predicts greater chronicity, remission, or variability in behavior.

2.3. Treatment Models and Therapeutic Integration

Theoretical approaches to the treatment of trichotillomania have evolved from isolated habit-reduction methods to multimodal frameworks that combine behavioral, cognitive, and pharmacological strategies. Behavioral interventions such as Habit Reversal Therapy (HRT) and its expanded form, Comprehensive Behavioral Treatment (ComB), represent the core psychological approaches described in prior literature. Both correspond to the “psychological therapy” category assessed in this study’s survey.

HRT focuses on increasing awareness of hair-pulling urges and teaching competing responses and stimulus-control techniques to interrupt automatic behavior. ComB, developed as a more individualized extension of HRT, evaluates five functional domains (sensory, cognitive, affective, motoric, and environmental) to tailor interventions to each person’s behavioral pattern.

These behavioral approaches are often complemented by pharmacological treatments such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), clomipramine, or glutamate modulators, which target underlying neurochemical dysregulation. Evidence indicates that combined therapy and medication produce the highest remission rates (Woods et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2017). Despite these advances, overall remission remains low, supporting the need for integrative approaches that address both behavioral mechanisms and neurobiological factors. This framework directly informs the study’s third research question on treatment and remission outcomes.

2.4. Social-Digital Ecosystems and Peer Support

Digital environments have increasingly been recognized as important ecosystems for mental-health support. The social-software perspective, described by Valerio-Ureña and Pasquel-López (2022), conceptualizes online platforms as participatory systems that facilitate knowledge sharing, peer interaction, and collective learning. Within these environments, individuals co-construct understanding and exchange experiential knowledge, creating informal networks that complement formal education and, by extension, clinical care.

In mental health, this approach aligns with a growing body of evidence showing that online peer communities can provide emotional validation, reduce isolation, and promote help-seeking behaviors among individuals facing stigmatized or underrecognized conditions (Naslund et al., 2016; Pretorius et al., 2019). Platforms such as Facebook, Reddit, and WhatsApp enable continuous, accessible communication that extends beyond geographic and socioeconomic barriers. These networks often serve as auxiliary ecosystems for information exchange, empathy, and emotional resilience, particularly in disorders characterized by shame or concealment, such as trichotillomania.

This framework supports the study’s fourth research question, which examines how participation in digital support communities influences perceived helpfulness and emotional support. By integrating the social-software perspective with mental-health communication research, this study contributes to understanding how online peer engagement can complement professional treatment and foster inclusion among Spanish-speaking individuals with trichotillomania.

2.5. Integrative Perspective

Trichotillomania can be understood through multiple theoretical perspectives that together offer a comprehensive conceptual foundation for this study. Each framework explains a specific aspect of the condition: emotional regulation describes how internal states such as anxiety and stress trigger hair-pulling episodes (Diefenbach et al., 2008; Franklin et al., 2011); developmental models highlight the importance of age of onset in determining severity and chronicity (Christenson et al., 1991; Keuthen et al., 2007); treatment theories describe the mechanisms and effectiveness of behavioral and pharmacological interventions (Woods et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2017); and the social-digital perspective examines the emerging role of online communities in providing emotional and informational support (Valerio-Ureña & Pasquel-López, 2022; Naslund et al., 2016).

The present study applies each perspective independently to address its corresponding research question. This approach allows for a multidimensional understanding of trichotillomania while preserving analytical clarity for each domain. Together, these complementary perspectives create the conceptual foundation for examining emotional, developmental, therapeutic, and social-digital dimensions within the Spanish-speaking population.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study used a cross-sectional, community-based survey administered online. The instrument was designed to examine four key dimensions of trichotillomania corresponding to the study’s research questions: emotional, developmental, therapeutic, and social-digital. Data were collected anonymously in Spanish via Google Forms between July 28, 2025 (08:39) and August 12, 2025 (21:11). Recruitment occurred within digital support communities dedicated to trichotillomania on Facebook and WhatsApp. Participation was voluntary and informed consent was obtained on the first page of the survey.

3.2. Participants

A total of 198 individuals completed the survey and self-identified as having trichotillomania or recurrent hair-pulling behavior. For ethical compliance and to avoid the need for parental permission, respondents younger than 18 years were excluded from the analytic sample. Inclusion criteria for the analytic sample were age 18 years or older, provision of informed consent, and personal experience with hair-pulling behaviors. The resulting adult analytic sample, used for all analyses reported in this manuscript, reflects a diverse Spanish-speaking population with broad representation across genders and countries of residence.

3.3. Recruitment

Participants were recruited from two online communities created and administered by the first author of this study: the Tricotilomanía: Grupo de Apoyo Facebook group (

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1029843221602726), founded in January 2024, and the associated WhatsApp group established in February 2024.

At the time of data collection, these communities had approximately 2,100 and 400 members, respectively. Both groups are dedicated to providing a safe and supportive environment for Spanish-speaking individuals affected by trichotillomania and their families. The author, as the founder and administrator of both groups, published an invitation post describing the purpose of the study, emphasizing voluntary and anonymous participation, and providing a direct link to the Google Forms survey. Group members who identified as experiencing trichotillomania were invited to participate, and 198 individuals completed the questionnaire between July 28 and August 12, 2025. No compensation was offered, and participation was entirely voluntary.

3.4. Survey Instrument

The survey was developed in Spanish and administered through Google Forms. It consisted of 36 questions divided into eight thematic sections:

Section 1. Consent (Q1): Participants confirmed voluntary and anonymous participation, with data used exclusively for general analysis.

Section 2. Demographics, Onset, and Duration (Q2–Q7): Items on age, gender identity, country of residence, age of onset of hair-pulling, duration of the condition, and official diagnosis status.

Section 3. Affected Areas, Frequency, and Patterns (Q8–Q11): Questions about body areas affected, changes in pulling sites over time, current frequency of episodes, and times of day when urges are most common.

Section 4. Triggers and Sensations (Q12–Q15): Items addressing situational and emotional triggers, awareness before pulling, and emotions experienced during and after episodes.

Section 5. Psychological and Social Impact (Q16–Q21): Questions on self-esteem, avoidance of activities or places, social and relational effects, reactions from close contacts, and perceived family understanding.

Section 6. Diagnosis, Treatments, and Strategies (Q22–Q29): Items covering comorbid diagnoses, current treatment type, attempts to stop pulling, methods used, perceived effectiveness, access to professional care, and perceptions of clinician knowledge.

Section 7. Support Groups and Community (Q30–Q33): Questions about participation in support groups, type of group, frequency of participation, and perceived helpfulness.

Section 8. Personal Perspective and Future (Q35–Q36): Open-ended and close-ended items on messages participants wish to share about trichotillomania and willingness to participate in future studies.

The survey combined multiple-choice, single-response, multiple-response, Likert-type, and open-ended questions, allowing both quantitative and qualitative analysis.

The Google Forms platform automatically recorded responses in a linked Google Sheets file accessible only to the authors through a password-protected Google account. No names, emails, or IP addresses were collected. Each respondent could review and edit their answers before submission, ensuring voluntary and informed participation. For full transparency, the complete survey questionnaire is included in Appendix A for full transparency.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

All participants provided informed consent on the first page of the survey before responding to any items. The consent form explained the study’s purpose, voluntary nature, anonymity, and absence of any personal identifiers. Participants confirmed agreement by selecting “I agree” before continuing. No identifying information, including names, emails, or IP addresses, was collected, and data were analyzed only in aggregate form.

The study was designed and conducted in accordance with recognized ethical standards for research involving human participants, including respect for confidentiality, informed consent, and voluntary participation, as outlined in the American Psychological Association’s guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. All data were securely stored in a password-protected Google account accessible only to the authors, and a de-identified dataset is available for verification upon request.

3.6. Data Analysis

Data were exported directly from Google Forms into spreadsheet format for cleaning, organization, and subsequent analysis. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, were calculated for all variables. For multiple-response questions, each response option was analyzed independently to accurately represent the relative prevalence of different experiences.

Cross-variable analyses were then conducted to address the four research questions, examining the relationships between emotional triggers and pulling frequency, age of onset and severity, treatment type and remission, and online community participation and perceived helpfulness.

Visualizations such as heatmaps, stacked bar charts, and contingency tables were generated using Microsoft Excel. Both row- and column-normalized heatmaps were applied to highlight absolute counts and proportional distributions. Stacked bar charts were used to display relative compositions across categories.

This analytical approach provided both descriptive clarity and relational insight, enabling the identification of multidimensional patterns that extend beyond single-variable analyses.

4. Results

4.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 198 individuals completed the survey.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the sample. The majority identified as female (n = 177, 89.4%), followed by male (n = 16, 8.1%), non-binary (n = 1, 0.5%), and prefer not to say (n = 2, 1.0%). Two participants did not provide gender information (1.0%).

Participant ages ranged from 18 to 68 years (mean ± SD = 29.5 ± 10.5).

The largest proportion of respondents resided in Mexico (33.8%), followed by Peru (13.1%), Colombia (9.6%), Spain (7.6%), Bolivia (5.1%), Argentina (4.5%), and Chile (4.5%), with smaller proportions from other countries. Two respondents did not report their country of residence (1.0%).

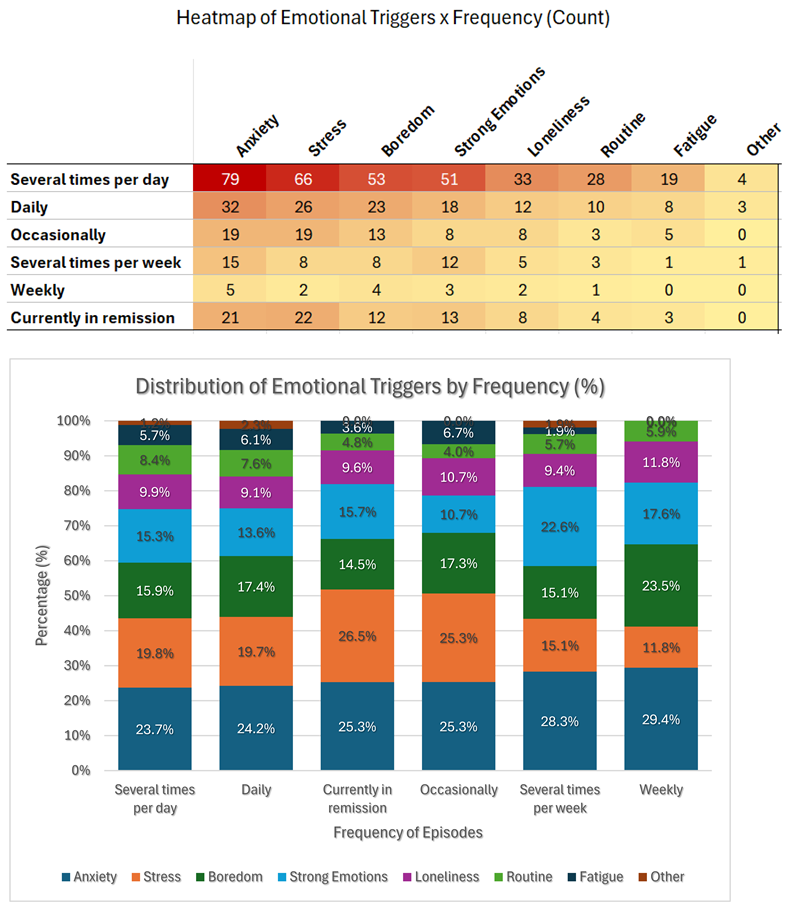

4.2. Research Question 1 - Emotional Triggers and Frequency of Pulling

Cross-variable item: When examining the relationship between emotional triggers and frequency of hair-pulling episodes, the results reflect the total number of trigger mentions rather than individual participants, since respondents could select more than one emotional situation. Thus, higher counts indicate that a given emotion was frequently reported within a frequency category, not that more people necessarily belonged to that group.

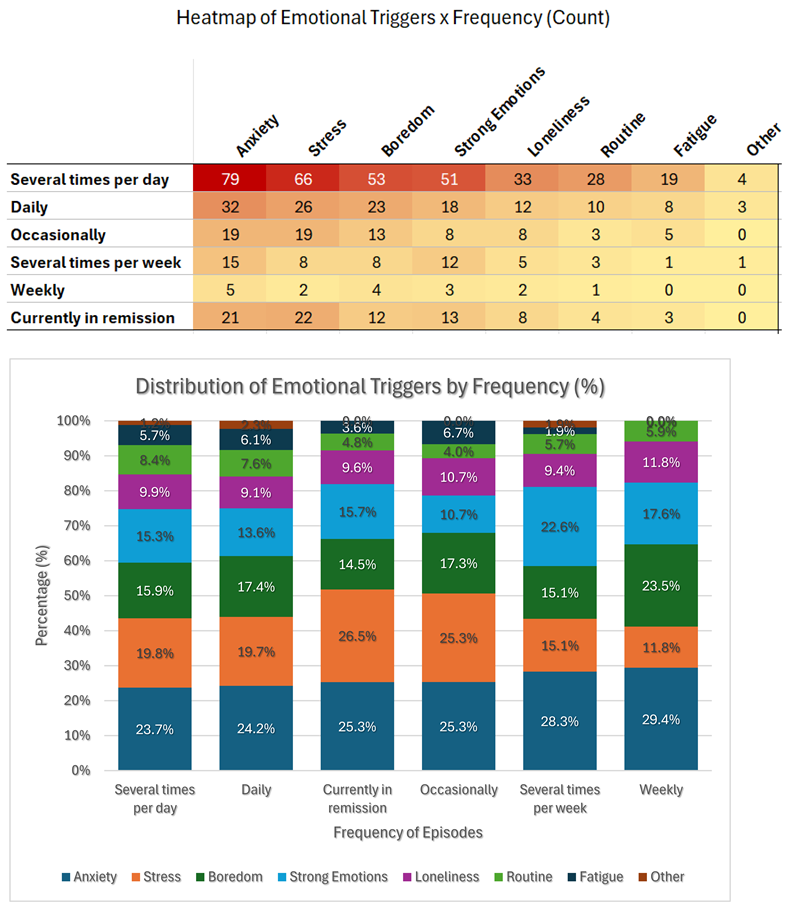

The data show a clear concentration among respondents who reported pulling several times per day, representing the highest cumulative number of emotional triggers (n = 333 mentions). Within this group, the most frequently cited emotions were anxiety (n = 79) and stress (n = 66), followed by boredom (n = 53) and strong emotions (n = 51). Participants who reported pulling daily also showed high mention counts for anxiety (n = 32) and stress (n = 26). Those pulling less frequently, such as occasionally or weekly, still mentioned anxiety and stress, but in smaller numbers.

Notably, participants who identified as being in remission (n = 83 mentions) continued to report emotional triggers, most often anxiety (n = 21) and stress (n = 22). These findings indicate that anxiety and stress remain central emotional drivers of hair-pulling behavior across all frequency levels, even among those who have temporarily stopped pulling.

Analysis

The visualizations show that anxiety and stress emerge as universal emotional triggers, present across all frequency categories but most concentrated among participants who pull several times per day. This concentration is evident in the Heatmap of Emotional Triggers × Frequency (Counts), where the darkest cells align with anxiety and stress in the highest-frequency group. The Distribution of Emotional Triggers by Frequency (%) further demonstrates that, proportionally, anxiety and stress dominate in every category. Strong emotions and loneliness appear as secondary triggers, especially pronounced in the highest-frequency group, suggesting that these emotions may reinforce chronic maintenance of the behavior. In contrast, boredom and routine are distributed more evenly across categories and appear at lower proportions, indicating a situational rather than sustaining role. Importantly, the persistence of emotional triggers among participants in remission highlights a latent vulnerability, in which the emotional context endures even when the behavior is inactive.

The figures replicate the expected centrality of anxiety and stress but also reveal four nuanced patterns in the composition of emotional triggers across frequency groups:

A trigger-composition gradient across frequency. As pulling frequency decreases, the relative weight of boredom grows, peaking in the weekly group (23.5%) and remaining lower in the highest-frequency group (15.9%). In contrast, fatigue is nearly absent at low frequency (0% weekly) but appears more often when pulling frequency is highest (5.7% several times per day). This gradient suggests two different ecosystems of risk: high-frequency pulling co-occurs with tension and overload, while low-frequency pulling may be more boredom-driven.

A “reactive-affect” profile at mid-frequency. The several times per week group shows a disproportionate spike in strong emotions (22.6%, the highest of any group) while stress remains comparatively lower (15.1%). This pattern may represent an episodic, surge-driven subgroup triggered by acute affect rather than chronic stress.

-

Anxiety-to-stress ratio tracks frequency and reverses in remission. The anxiety:stress ratio rises as frequency drops, except in remission, where the relationship flips:

- o

Several times per day = 1.20 Daily = 1.23 Occasionally = 1.00 Several times per week = 1.88 Weekly = 2.50 Remission = 0.95. In other words, anxiety tends to dominate over stress as episodes become less frequent, but among those in remission, stress slightly exceeds anxiety. This may indicate that anxiety is being managed more effectively, while stress persists as a residual vulnerability factor.

Secondary triggers linked to chronicity vs. situationality. Loneliness and routine are not the most common triggers, yet they accumulate noticeably within the highest-frequency group (loneliness = 9.9%, routine = 8.4%). Their presence suggests that social isolation and repetitive contexts may help sustain chronic behavior rather than simply spark isolated episodes.

Preliminary Conclusion

This cross-variable analysis shows that emotional triggers are closely linked with pulling frequency. Anxiety and stress appear as universal triggers across all groups but are most concentrated among participants who pull several times per day. Loneliness and strong emotions increase in weight in the highest-frequency group, suggesting a role in maintaining chronicity. By contrast, boredom and routine are present across groups but remain secondary. Even individuals in remission reported anxiety and stress, indicating that emotional vulnerability persists despite cessation of behavior. Distinct frequency-related profiles also emerged:

High-frequency cases concentrated on anxiety and stress, with additional fatigue and routine.

Mid-frequency cases showed a spike in strong emotions with lower stress, reflecting a more reactive profile.

Low-frequency cases showed greater proportional boredom.

Remission cases reported stress slightly outweighing anxiety, suggesting residual stress as a potential vulnerability factor.

Overall, these findings confirm that trichotillomania’s emotional landscape is dynamic and multidimensional. Even when behavioral symptoms subside, the persistence of stress and emotional sensitivity points to the importance of interventions that address both acute affect regulation and chronic background tension.

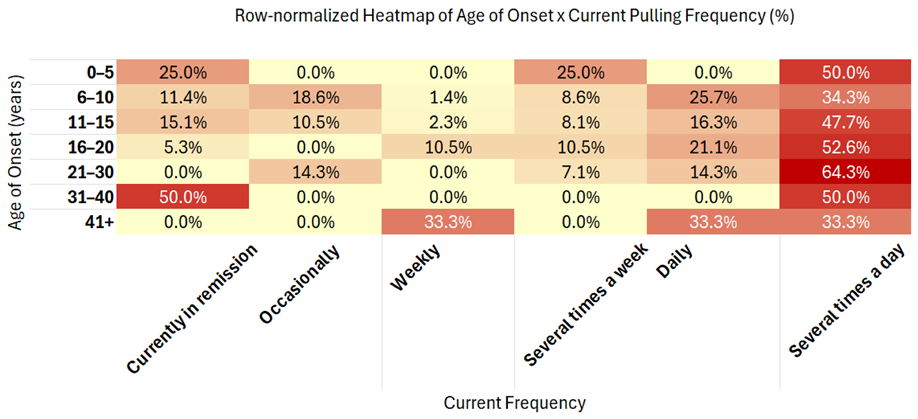

4.3. Research Question 2 - Age of Onset and Severity

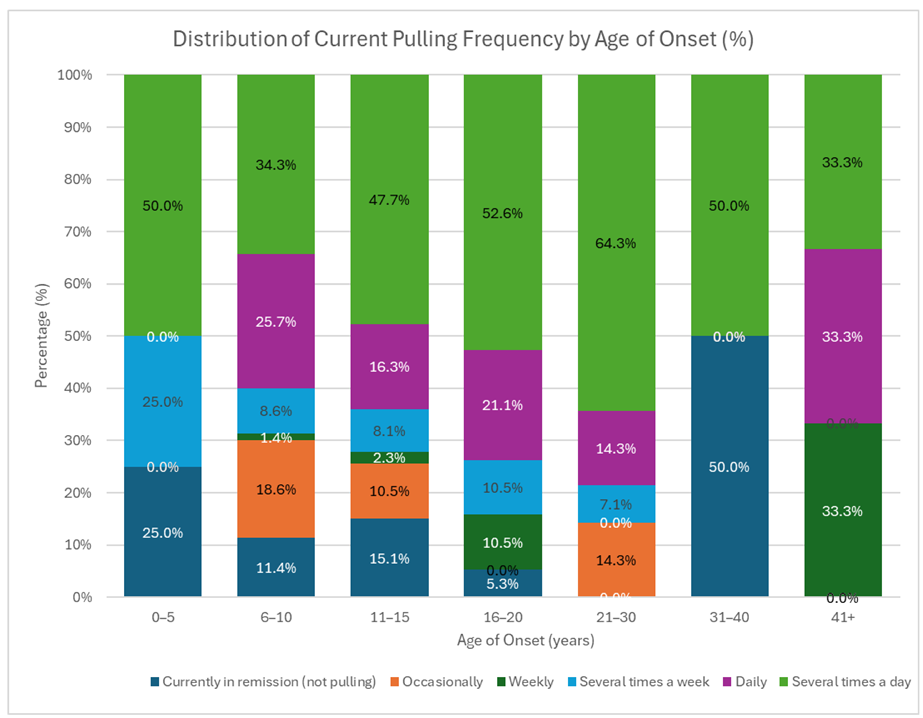

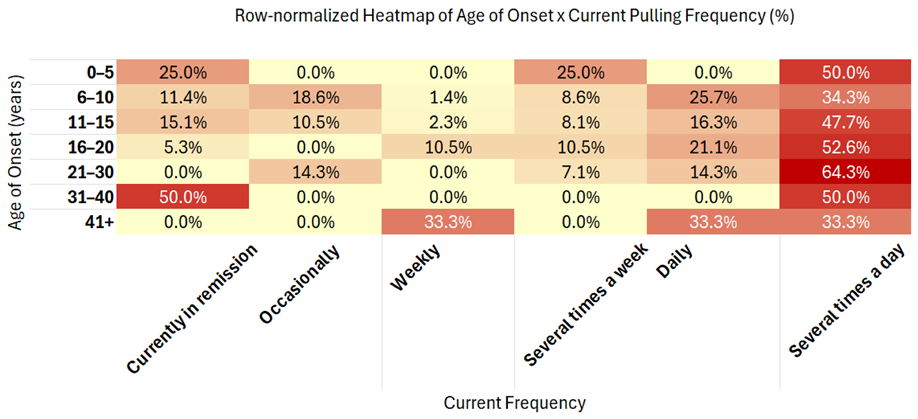

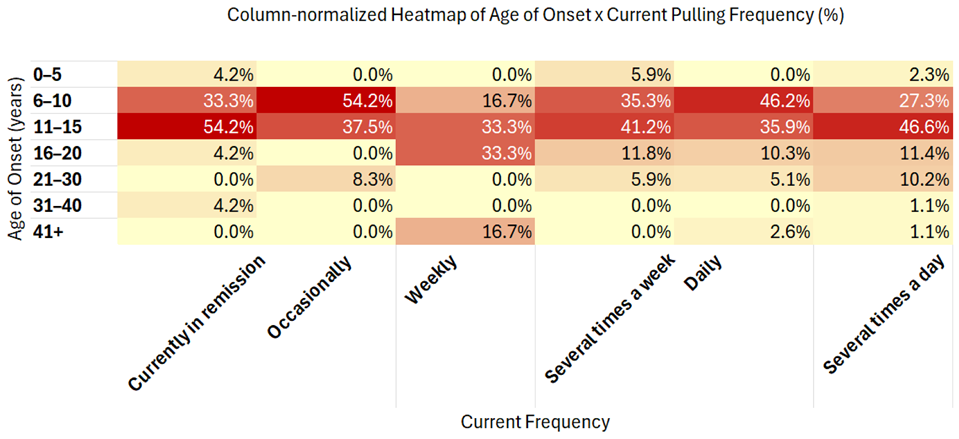

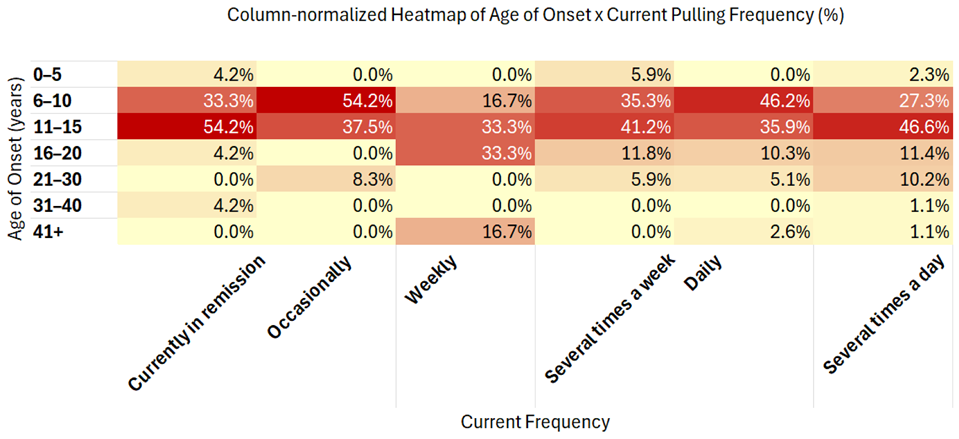

Cross-variable item: When examining the relationship between age of onset and the current frequency of hair-pulling episodes, the results confirm the widely reported pattern that trichotillomania most often begins in childhood and adolescence. The majority of participants reported onset between ages 11–15 (n = 86, 43%) and 6–10 (n = 70, 35%). Within these two age bands, a large proportion reported high-frequency pulling, either several times per day (11–15: 47.7%; 6–10: 34.3%) or daily (11–15: 16.3%; 6–10: 25.7%). Later-onset groups—16–20 years (n = 19) and 21–30 years (n = 14)—were smaller but continued to show high proportions of daily or near-daily episodes, suggesting that chronicity can emerge regardless of onset period. Very early onset (0–5 years, n = 4) and late onset (31 years and older, n = 5 combined) were rare and displayed mixed outcomes, ranging from remission to persistent severe pulling.

Analysis

The distribution (Graph Distribution of Current Pulling Frequency by Age of Onset(%)) reinforces established findings that adolescence represents the peak onset window for trichotillomania, but it also reveals developmental nuances and novel patterns:

- 2.

Adolescent onset as the strongest predictor of chronicity. Nearly half of participants with onset between 11–15 years pull several times per day. This confirms prior research identifying adolescence as a sensitive period for symptom entrenchment.

- 3.

Dual trajectory of childhood vs. adolescent onset. Although both 6–10 and 11–15 onset groups are large, their outcomes diverge: the 11–15 group clusters more tightly in high frequency, while the 6–10 group shows slightly more cases in occasional pulling or remission. This suggests that childhood onset may carry a higher chance of attenuation, whereas adolescent onset predicts more persistent trajectories.

- 4.

Late-onset severity paradox. While uncommon, the 21–30 onset group demonstrates the highest proportion in “several times per day” pulling (64.3%), exceeding adolescent groups. This indicates that adult-onset cases, though rare, may follow a distinct high-intensity phenotype.

- 5.

Remission clusters at the extremes. The highest relative remission rates appeared at the tails: 0–5 (25%) and 31–40 (50%). While based on very small n, this pattern suggests that extremely early or late onset may resolve more easily or appear in shorter bursts, in contrast to the entrenched adolescent-onset course.

The Row-normalized Heatmap of Age of Onset × Current Pulling Frequency (%) makes these gradients visible by showing how frequencies are distributed within each age-of-onset group. Darker concentrations cluster at the intersection of adolescent onset (11–15) and very high frequency (several times/day), while late-onset severity (21–30) also stands out despite smaller counts. Importantly, remission is still present in early-onset groups, underlining the heterogeneity of developmental trajectories.

The Column-normalized Heatmap of Age of Onset × Current Pulling Frequency (%) provides the complementary view, displaying the composition of age-of-onset groups within each frequency category. This perspective reveals that most individuals in every frequency band began pulling before age 16, for example, 82% of daily pullers and 74% of several-times/day pullers had onset by age 15. At the same time, the 21–30 group is overrepresented in the most severe category (10.2% of several/day cases despite only 7.1% of the sample overall), reinforcing the existence of a late-onset high-intensity phenotype. Together, these two normalizations confirm adolescence as the dominant entry point into trichotillomania, while highlighting nuanced severity and composition patterns across onset ages.

Preliminary Conclusion

This analysis reinforces adolescence (ages 11–15) as the peak onset window most strongly tied to chronic high-frequency pulling, while also showing that childhood onset (ages 6–10) is more heterogeneous, with a greater share of occasional or remission outcomes. Late-onset cases (21+) are rare but disproportionately severe, suggesting a distinct high-intensity variant. Extremely early (≤5) and late (≥31) onset are very rare and more often associated with remission. Overall, age of onset emerges as both a developmental marker and a predictor of severity, shaping distinct clinical trajectories.

4.4. Research Question 3 - Treatment and Remission

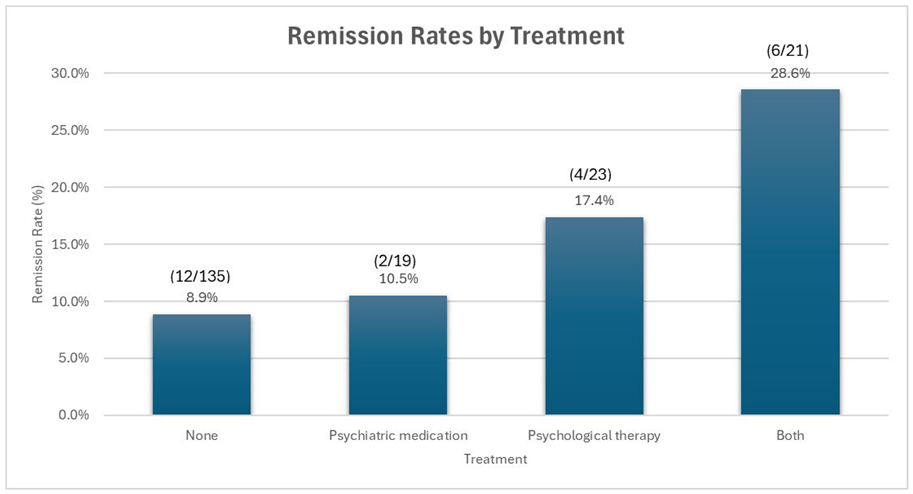

Cross-variable item: When examining the relationship between treatment received and remission status, the majority of participants reported not being in remission (n = 174, 87.9%), regardless of treatment type. Overall, only 12.1% (n = 24/198) of participants were in remission. The distribution by treatment group is shown below.

Analysis

The bar chart of remission rates by treatment illustrates clear differences among groups. Participants receiving both psychological therapy and psychiatric medication had the highest proportion in remission (28.6%, 6/21), followed by those receiving psychological therapy alone (17.4%, 4/23). In contrast, remission was less common among those receiving psychiatric medication alone (10.5%, 2/19) and lowest among those reporting no treatment (8.9%, 12/135).

This pattern suggests several important insights:

Combination treatment advantage. The highest remission rate was observed among those receiving both therapy and medication, indicating a potential additive or synergistic benefit.

Therapy outperforms medication alone. Psychological therapy showed higher remission rates than psychiatric medication alone, hinting at the relative importance of addressing behavioral and cognitive components in trichotillomania.

Low remission without treatment. Participants with no treatment still showed some remission (8.9%), suggesting natural attenuation for a minority, but the rate was lower than all treatment groups.

Overall remission is rare. Even with treatment, remission rates remain modest, underscoring the chronic nature of trichotillomania and the need for more effective interventions.

Preliminary Conclusion

This cross-variable analysis shows that remission remains rare across all groups, with only 12.1% of participants reporting recovery. The highest remission rates were observed among those receiving both psychological therapy and psychiatric medication, followed by psychological therapy alone, while psychiatric medication alone and no treatment showed the lowest remission. These results highlight clear differences in outcomes depending on treatment type, but also confirm that across groups, sustained remission is uncommon.

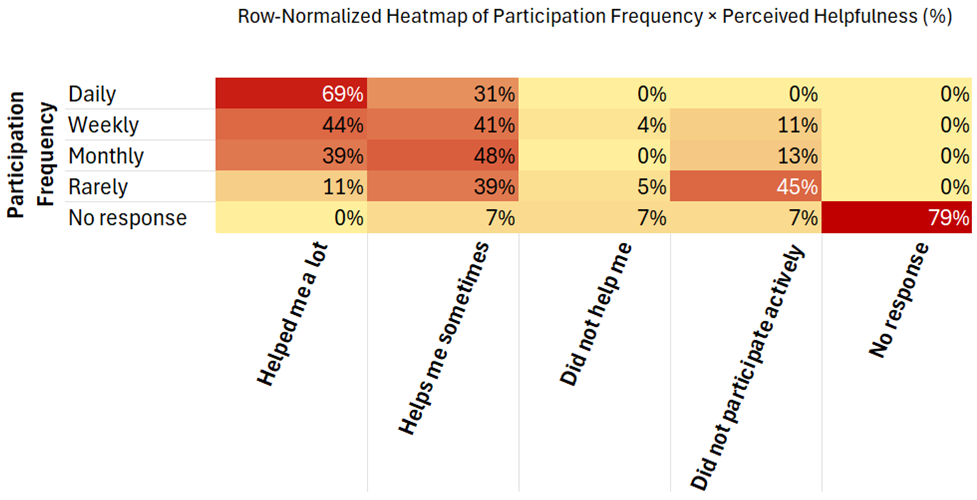

4.5. Research Question 4 – Online Community Participation and Perceived Helpfulness

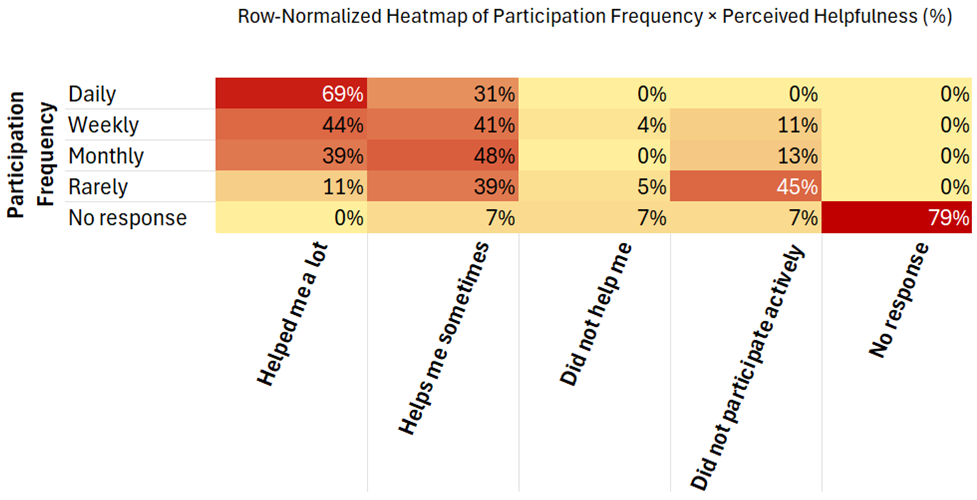

Cross-variable analysis: When examining the relationship between participation frequency in online support communities and perceived helpfulness, the results show a clear positive association between engagement intensity and perceived benefit. Among 198 respondents, 167 (84.3%) reported belonging to Facebook or WhatsApp groups. Within high-engagement categories, daily users reported that groups helped a lot (69%) or helped sometimes (31%), and weekly users reported similar patterns (helped a lot 44%; helped sometimes 41%). Monthly users displayed intermediate benefit levels (helped a lot 39%; helped sometimes 48%). In contrast, rare participants most frequently selected did not participate actively (45%) or did not help (5%).

Analysis

The heatmaps reveal graded engagement–benefit dynamics and several consistent patterns:

Benefit increases with engagement. Higher participation frequency aligns with greater perceived support, with daily and weekly users clustering in the helped a lot and helped sometimes categories.

Engagement threshold around monthly. Benefit remains high down to monthly participation (87% reporting some help), but drops sharply among rare participants, who concentrate in did not participate actively.

Latent nonparticipation subgroup. A sizeable minority reports minimal engagement or inactivity, mirroring the “observer” pattern seen in many online health communities, where informational exposure may occur without strong perceived emotional benefit.

No evidence of overexposure fatigue. Daily users do not report lower helpfulness than weekly users, suggesting that frequent interaction remains beneficial rather than overwhelming.

The row-normalized heatmap illustrates how helpfulness ratings are distributed within each participation level. Darker concentrations appear for daily and weekly participants in the helped a lot and helps me sometimes categories, while lighter tones dominate among rare participants in the did not participate actively column. This pattern visually reinforces the positive gradient between sustained engagement and perceived emotional benefit.

Preliminary Conclusion

This cross-variable analysis demonstrates that frequent participation in online support communities is strongly associated with higher perceived emotional and informational support. Participants who engage daily or weekly in Facebook and WhatsApp groups report significantly more benefit than those who interact only occasionally or rarely. These findings underscore the importance of social-software ecosystems as valuable, accessible environments that complement clinical care through peer interaction, shared learning, and mutual encouragement.

5. Discussion

This community-based survey of 198 adult Spanish-speaking individuals examined how emotional, developmental, therapeutic, and social-digital dimensions coexist and relate conceptually in trichotillomania. Guided by four research questions, the analyses revealed that (1) anxiety and stress dominate as emotional triggers across all severity levels, (2) childhood and adolescent onset predict the most chronic trajectories, (3) combined therapy + medication yields the highest remission rates, and (4) frequent participation in online support communities correlates with greater perceived emotional and informational benefit. Collectively, these findings outline a multidimensional profile of trichotillomania shaped by interconnected psychological, developmental, treatment, and digital-social factors.

5.1. Summary of Main Findings

Most participants reported high pulling frequency (daily or several times per day) and marked psychosocial impact, particularly on self-esteem.

Emotional dimension (RQ1): Anxiety (25%) and stress (21%) were the most frequent triggers; both persisted even in remission, underscoring enduring emotional vulnerability.

Developmental dimension (RQ2): Onset clustered between ages 6–15, with adolescent-onset cases showing the greatest chronicity. A smaller late-onset group (21–30 years) displayed unexpectedly high severity.

Therapeutic dimension (RQ3): Only 12.1 % of participants were in remission. Combined therapy + medication produced the highest remission proportion (28.6 %), followed by therapy alone.

Social-digital dimension (RQ4): Most respondents (84 %) engaged in online support groups, and regular participants (daily/weekly) reported that these groups “helped a lot” or “helped sometimes,” demonstrating measurable perceived benefit.

5.2. Interpretation in Context

Several of the patterns observed in this dataset replicate well-established findings in previous research. The predominance of anxiety and stress as the main emotional triggers (RQ1) echoes earlier studies identifying trichotillomania as closely linked to emotion-regulation difficulties and tension relief (Franklin et al., 2011; Diefenbach et al., 2008). The concentration of onset between ages 6 and 15 (RQ2) aligns with clinical evidence that late childhood and adolescence constitute a critical vulnerability window for the disorder’s emergence (Christenson et al., 1991; Keuthen et al., 2007). Likewise, the low remission rates and only partial effectiveness of single interventions (RQ3) correspond to prior descriptions of trichotillomania as a chronic condition often resistant to isolated treatment approaches (Woods et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2017).

At the same time, the present dataset contributes several novel insights that extend the literature.

The trigger-composition gradient (RQ1) revealed that boredom and routine were more common at low frequency, whereas fatigue, strong emotions, and loneliness clustered in high-frequency pulling, delineating situational versus chronic emotional profiles.

The age-of-onset × frequency analysis (RQ2) identified a late-onset high-intensity subgroup (ages 21–30), a rarely documented pattern suggesting that adult-onset cases may represent a distinct clinical trajectory.

The treatment × remission cross (RQ3) confirmed that combined therapy plus medication yielded the highest remission proportion (28.6 %), followed by therapy alone, emphasizing the advantage of multimodal care.

The emotions × frequency analysis highlighted pain and automaticity as transitional markers, more frequent in partial remission, possibly reflecting emotional instability rather than stable recovery.

Finally, the digital-community dimension (RQ4) showed that consistent participation in Facebook and WhatsApp groups was associated with higher perceived emotional and informational support, providing quantitative evidence for the role of social-software ecosystems in complementing professional treatment.

Additional micro-patterns refine this picture. In remission cases, stress slightly outweighed anxiety, suggesting that residual stress may persist as a latent vulnerability even after behavioral cessation.

Possible mechanisms underlying these differences include:

Developmental vulnerability: adolescence may coincide with heightened stress reactivity and identity formation, predisposing individuals to chronic trajectories once pulling begins.

Contextual moderators: situational pulling driven by boredom or routine may be less entrenched, whereas emotionally loaded pulling (anxiety, loneliness, strong emotions) sustains chronicity.

Treatment heterogeneity: the higher remission rates in the combined-treatment group indicate that multifactorial approaches addressing both behavioral and neurochemical pathways are more effective.

Phenotype variation: high-frequency pulling is not uniform; multiple-daily cases reflect reinforcement dominance, whereas daily cases reflect mixed motives and transitional instability.

Together, these interpretations support a multidimensional view of trichotillomania that considers emotional, developmental, therapeutic, and social-digital factors, offering a cohesive understanding of how biological, psychological, and social processes interact in this disorder.

5.3. Clinical and Policy Implications

The findings emphasize that trichotillomania should be conceptualized primarily as a disorder of emotional regulation rather than a simple habit.

Clinicians should systematically assess anxiety (and stress) linked urges during diagnosis and treatment planning.

Early detection efforts in pediatric and educational settings remain crucial, as intervention during the 6–15 age range may prevent chronicity.

Although adult-onset cases are rare, their severity indicates the need for more intensive, possibly trauma-informed, interventions.

Therapeutically, results support multimodal treatment frameworks that integrate behavioral therapy with medication when indicated.

Given the high perceived benefit of online peer communities, clinicians may consider recommending moderated digital groups as adjunctive supports, particularly in settings with limited access to specialized services.

At a policy level, these findings argue for increased access to behavioral therapists trained in habit-reversal and emotion-regulation approaches, as well as public campaigns reframing trichotillomania as a psychosocial condition that affects identity and self-worth.

5.4. Strengths

This study provides one of the largest community-based datasets on trichotillomania in adults and the first focused on Spanish-speaking online populations.

Its design integrated both descriptive and relational analyses, allowing identification of previously undocumented subtypes such as adolescent-onset chronicity and adult-onset high-intensity patterns.

By leveraging social-software recruitment, the study achieved high ecological validity and captured voices often absent from clinical research.

5.5. Limitations

Interpretation should consider several limitations. Data were self-reported and may be influenced by recall or desirability bias. Recruitment through online communities may overrepresent digitally engaged individuals and underrepresent those without internet access. Diagnoses were not clinically verified, and the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. Because all materials were in Spanish, cultural and linguistic differences may limit generalization. Finally, while minors were excluded for ethical reasons, this also prevents direct comparison across the full developmental spectrum.

5.6. Future Research

Future studies should use longitudinal designs to track symptom evolution and evaluate the durability of remission across onset groups. Randomized clinical trials are needed to assess multimodal interventions, particularly combinations of therapy and medication. Expanding research to multiple languages and cultural contexts will determine whether these patterns generalize beyond Spanish-speaking populations. Finally, systematic evaluation of digital peer-support ecosystems should quantify their psychological and behavioral effects, clarifying how online participation complements or enhances professional care.

6. Conclusions

This study presents one of the largest community-based analyses of trichotillomania among Spanish-speaking individuals, offering new empirical insights into emotional, developmental, therapeutic, and social-digital dimensions of the disorder. The results confirm several well-established patterns, such as the predominance of anxiety and stress as emotional triggers and the concentration of onset between ages 6 and 15. However, they also introduce novel findings that extend current understanding.

First, the proportional analysis of emotional triggers by frequency revealed a distinct emotional gradient, where anxiety and stress dominate across all levels but emotions such as loneliness and strong affect become more prominent in high-frequency pulling, suggesting a deeper emotional entrenchment in chronic cases. Second, a late-onset high-intensity subgroup (ages 21–30) was identified, an underreported pattern that may represent a unique developmental trajectory within adult-onset trichotillomania. Third, the analysis of treatment outcomes demonstrated that combined therapy and medication yielded the highest remission rates, quantitatively reinforcing prior hypotheses about multimodal efficacy. Finally, the study documented a measurable positive impact of online peer communities (Facebook and WhatsApp), where more frequent participation was associated with greater perceived emotional and informational support.

These findings contribute original data to the scientific literature on trichotillomania and highlight the potential of digital social environments as complementary support systems for individuals with body-focused repetitive behaviors. Beyond describing prevalence, the study underscores the need for culturally inclusive and digitally informed approaches to mental-health research, particularly in underrepresented linguistic populations. Future work should further explore these new subtypes and online engagement patterns through longitudinal and clinical methodologies to clarify causal mechanisms and long-term outcomes.

Author Contributions

This research was conducted as an independent, community-based study on trichotillomania by the authors. It was not completed as coursework or a class assignment.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymized dataset generated and analyzed during this study is available from the authors upon reasonable request for research verification purposes. To protect participant confidentiality, individual survey responses are not publicly shared.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Preregistration

This study was not preregistered.

AI/LLM Disclosure

Generative artificial intelligence tools were not used to generate, analyze, or interpret data in this study. Minor text editing and formatting refinements were performed with ChatGPT under the authors’ direct supervision. The author takes full responsibility for the originality, accuracy, and integrity of all content, in accordance with MDPI and Preprints.org publication ethics guidelines.

References

- Christenson, G. A., Mackenzie, T. B., & Mitchell, J. E. (1991). Characteristics of 60 adult chronic hair pullers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148(3), 365–370. [CrossRef]

- Diefenbach, G. J., Tolin, D. F., Hannan, S., Crocetto, J., & Worhunsky, P. (2008). Trichotillomania: Impact on psychosocial functioning and quality of life. CNS Spectrums, 13(4), 370–377.

- Duke, D. C., Keeley, M. L., Geffken, G. R., & Storch, E. A. (2009). Trichotillomania: A current review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 294–306. [CrossRef]

- Flessner, C. A., Conelea, C. A., Woods, D. W., Franklin, M. E., Keuthen, N. J., & Cashin, S. E. (2008). Styles of pulling in trichotillomania: Exploring differences in symptom severity, phenomenology, and comorbidity. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(3), 345–357. [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M. E., Edson, A. L., Ledley, D. R., & Cahill, S. P. (2011). Behavior therapy for pediatric trichotillomania: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(8), 763–771. [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M. E., Zagrabbe, K., & Benavides, K. L. (2008). Trichotillomania and its treatment: A review and recommendations. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 8(12), 1965–1974.

- Grant, J. E., Odlaug, B. L., & Chamberlain, S. R. (2017). Trichotillomania: Clinical characteristics, assessment, and treatment. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 13, 1343–1354.

- Keuthen, N. J., Rothbaum, B. O., Fama, J., Altenburger, E., Falkenstein, M. J., Sprich, S., & Welch, S. S. (2012). DBT-enhanced cognitive-behavioral treatment for trichotillomania: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43(4), 1083–1091. [CrossRef]

- Keuthen, N. J., Tung, E. S., Altenburger, E. M., Sprich, S. E., & Pauls, D. L. (2007). Trichotillomania: Behavioral symptom or clinical syndrome? American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(10), 1501–1509.

- Naslund, J. A., Aschbrenner, K. A., Marsch, L. A., & Bartels, S. J. (2016). The future of mental health care: Peer-to-peer support and social media. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 25(2), 113–122. [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, C., Chambers, D., & Coyle, D. (2019). Young people’s online help-seeking and mental health difficulties: Systematic narrative review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(11), e13873. [CrossRef]

- Valerio-Ureña, G., & Pasquel-López, C. (2022). EduTubers’s pedagogical best practices and their theoretical foundation. Informatics, 9(4), 84. [CrossRef]

- Woods, D. W., Flessner, C. A., Franklin, M. E., Keuthen, N. J., Goodwin, R. D., Stein, D. J., & Walther, M. R. (2006). The Trichotillomania Impact Project (TIP): Exploring phenotypic heterogeneity in a large international sample. Depression and Anxiety, 23(5), 319–328. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics of the sample (n = 198).

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics of the sample (n = 198).

| Characteristic |

n |

% |

| Gender |

|

|

| Female |

177 |

89.4% |

| Male |

16 |

8.1% |

| Non-binary |

1 |

0.5% |

| Prefer not to say |

2 |

1.0% |

| Missing/No response |

2 |

1.0% |

| Age (years) |

|

|

| Range |

18 – 68 |

– |

| Mean ± SD |

29.5 ± 10.5 |

– |

| Country of residence |

|

|

| Mexico |

67 |

33.8% |

| Peru |

26 |

13.1% |

| Colombia |

19 |

9.6% |

| Spain |

15 |

7.6% |

| Bolivia |

10 |

5.1% |

| Chile |

9 |

4.5% |

| Argentina |

9 |

4.5% |

| Guatemala |

6 |

3.0% |

| United States |

6 |

3.0% |

| Venezuela |

5 |

2.5% |

| Ecuador |

5 |

2.5% |

| Dominican Republic |

4 |

2.0% |

| Costa Rica |

4 |

2.0% |

| Uruguay |

3 |

1.5% |

| Iran |

2 |

1.0% |

| No response |

2 |

1.0% |

| Others combined |

6 |

3.0% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).