1. Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women [

1,

2]. Radiation therapy is an important treatment modality in cervical cancer, whether as a definitive or adjuvant treatment [

3,

4]. Although radiation therapy eliminates clinical and subclinical cancer cells, it can also damage the surrounding normal tissue. Lymphocytes are highly radiosensitive hematopoietic cells and can be depleted with an extremely low dose of 0.5–1 Gy [

5]. Depletion of lymphocytes is commonly induced in patients treated with radiation therapy; however, the clinical impact of radiation therapy-induced lymphopenia on cancer survival has recently been recognized in light of the advent of immunotherapy. Lymphocytes play an essential role in cancer immunity by detecting tumor antigens and directly killing tumor cells.

Recently, the unfavorable effect of lymphopenia on survival has been demonstrated in several solid tumors [

6,

7]. Although several studies have shown that pretreatment lymphopenia is associated with worse survival, the effect of treatment-induced lymphopenia on survival is controversial [

8,

9,

10]. Because it is a modifiable factor in the era of modern radiation therapy, the influence of radiation therapy-induced lymphopenia on survival outcomes deserves further investigation. It is well known that bone-marrow sparing RT decreases the severe lymphopenia in cervical cancer, and proton therapy is presumed to be able to further reduce the probability and severity of lymphopenia [

6,

11,

12]. The RT field is another selectively modifiable factor in cervical cancer. The RT field in cervical cancer typically extends from the caudal margin of the obturator foramen to the cranial margin of the L5 vertebral spine. In some patients with more advanced disease or paraaortic lymph node involvement, the cranial border of the RT field is extended to T12-L1 level.

In this study, we evaluated the impact of treatment-induced lymphopenia on survival in patients who underwent RT for cervical cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients with histologically confirmed cervical cancer who received RT between January 2001 and December 2017. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (no. 2022-11-140-002). Patients were excluded if they had the following: 1) RT alone, 2) distant metastases, 3) if patient does not consent to the use of personal data, 4) absence or lack of laboratory test results before or during RT course. Among the searched 400 patients, we identified 215 patients who satisfied the inclusion criteria (

Figure 1). Patients were staged according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2018 classification.

2.2. Treatment

All Patients received external beam radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy. A total of 50.4 Gy with daily fraction size of 1.8 Gy was administered five times per week to the whole pelvis or extended field. Four-field box technique using anteroposterior/posteroanterior and two lateral fields was used in 99.5% of the patients and only one patient received intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). The upper margin of whole pelvic RT was L4-5 junction or L5-S1 junction and that of extended field RT was T12-L1. Extended field RT was performed in case of suspected or positive para-aortic lymph node and the additional lymph node boost was delivered if necessary. High dose-rate intracavitary brachytherapy was started 4–5 weeks after the initiation of external beam radiation therapy in case of definitive treatment or close or positive vaginal resection margin after hysterectomy. The concurrent chemotherapy regimen was weekly cisplatin for six cycles or 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin every three weeks for two to three cycles.

2.3. Endpoints and Statistical Analysis

Patients underwent regular follow-up examinations, including physical examination, hematologic studies, and CT. The endpoints included disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). DFS is calculated from the start date of initial treatment to the date of recurrence, death, or last follow up. OS is calculated from the start date of initial treatment to the date of death or last follow-up.

To evaluate RT-induced lymphopenia, we used ‘ΔALC/preALC’ for analysis. ‘ΔALC/preALC’ was defined as (pre-treatment absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) – nadir ALC during CCRT/pre-treatment ALC) and converted to categorical variable. The optimal cut point of ΔALC/preALC was determined using a Contal and O’Quigley method [

13].

A T-test was used to compare the mean values between the groups. The Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used for survival curves. The Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and confidence intervals (CI) in univariable and multivariable survival analysis. A p-value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariable analysis was performed on variables that showed a probability value of <0.2 or on those that were thought to be relevant with backward selection method. Path analysis was performed using logistic model to examine the relationships between RT-field, lymphopenia, and survival outcome. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Patients’ characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. The median age was 53 years (range, 27–81). Seventy-seven patients (35.8%) had stage I disease, 43 (20.0%) had stage II disease, 91 (42.3%) had stage III disease, and 4 (1.9%) had stage IVa disease. Squamous cell carcinoma was the most frequent histology (n = 180, 83.7%), followed by adenocarcinoma in 30 patients (14.0%), adenosquamous cell carcinoma in 4 patients (1.9%), and mixed cell carcinoma in 1 patient (0.5%). Ninety-eight patients (45.6%) received adjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy. In terms of RT field, 179 (83.3%) patients received whole pelvis RT and 36 (16.7%) patients received extended field RT. The median pre-treatment ALC was 1.731

× 103/μL (0.862-3.940) and the median nadir ALC was 0.35 x 103/μL (0.03-0.93).

3.2. Cutoff Value of ΔALC/pre ALC

The median ΔALC/pre ALC was 0.804 (0.425-0.981). The optimal cutoff value of ΔALC/pre ALC for prediction of OS and DFS was analyzed and determined to be 0.88.

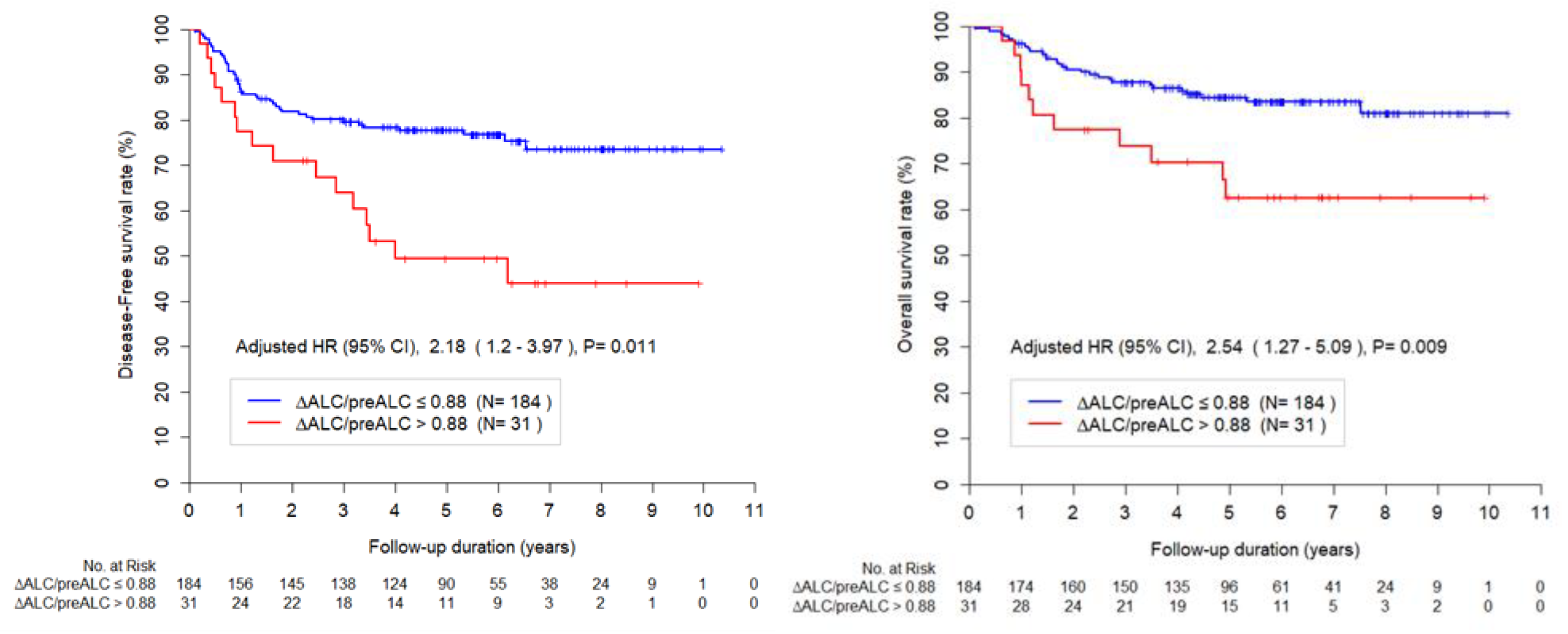

3.3. Survival Outcomes and Prognostic Factors

The median follow-up time was 61.04 months (range, 1.34-124.02). The DFS at 3-year and 5-year were 85.0% and 73.6%, and OS at 3-year and 5-year were % and 81.0%, respectively. Multivariable analysis for DFS revealed that pre-treatment SCC (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.00–1.03; p = 0.037), pathology (others

vs. squamous cell carcinomas, HR, 2.58; 95% CI, 1.37-4.83; p = 0.003) and ΔALC/preALC level (>.88

vs. ≤0.88, HR, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.20-3.97; p = 0.011) were independent prognostic factors (

Table 2).

Multivariable analysis for OS revealed that pathology (others

vs. squamous cell carcinomas, HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.22-4.75; p = 0.011) and ΔALC/preALC level (>.88

vs. ≤0.88, HR, 2.54; 95% CI, 1.27–5.09; p = 0.009) were independent prognostic factors (

Table 3).

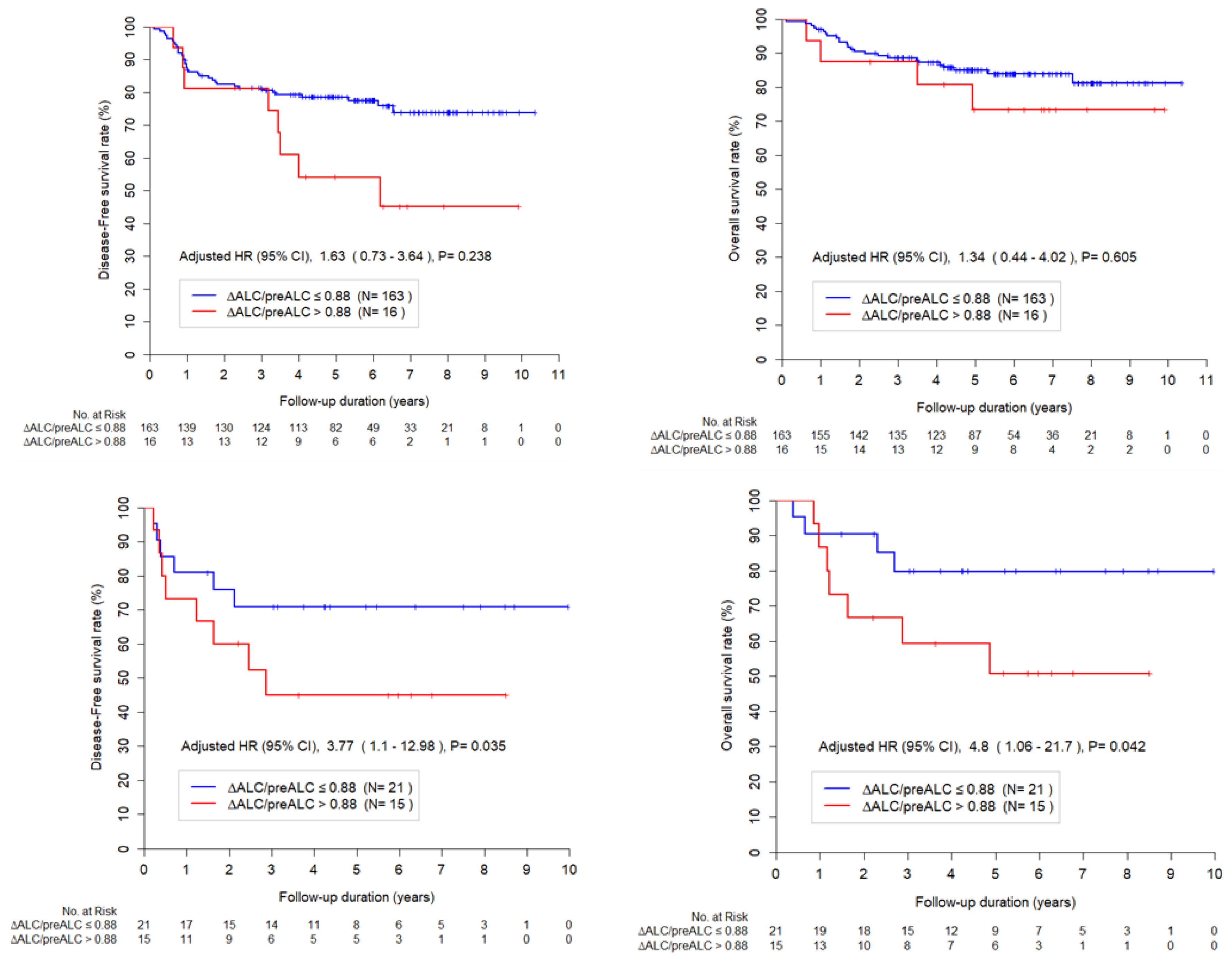

3.4. Lymphopenia and RT Field

The mean values of ΔALC/pre ALC according to the RT field were 0.77 and 0.85 in whole pelvis and extended RT group, respectively (p < 0.001). The effect of lymphopenia was evaluated in each subset of RT field and

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves according to ΔALC/preALC for survival in whole pelvis and extended RT group. In whole pelvis RT subgroup, ΔALC/preALC level was not a significant factor for DFS or OS. In extended RT subgroup, ΔALC/preALC level was a significant factor for DFS or OS.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the impact of lymphopenia during RT on survival in cervical cancer patients. We found that the severe lymphopenia (ΔALC/preALC level > 0.88) was associated with worse DFS and OS in all patients. The definition of RT-induced lymphopenia is heterogeneous in relevant studies [

6,

8,

14]. Several studies use CTCAE criteria and define severe lymphopenia as more than grade 3 or 4 lymphocytopenia while other authors used the cutoff value of 1000cm/L [

15]. In this study, we defined RT-induced lymphopenia as the ratio of an individual's pre-treatment ALC to their nadir ALC, in order to reflect the individual's baseline values. In this study, lymphocyte counts decreased by 80% on average from the baseline values during RT, and this is similar to the results from other studies [

14].

Furthermore, we found that the severity of lymphopenia and the impact of lymphopenia on survival differ according to the RT field. The degree of lymphopenia was more prominent in the extended RT field group compared to the whole pelvis RT group (mean 0.77 vs. 0.85, p < 0.001). The effect of lymphopenia on survival in cervical cancer is not yet established. Several studies showed that lymphopenia is related to worse survival, while others reported that the effect of lymphopenia was not significant after adjustment of other factors [

14]. We found that lymphopenia (ΔALC/pre ALC > 0.88) after RT was associated with worse OS in all patients. Because RT field and tumor burden are the most critical confounders for identifying the independent impact of lymphopenia, we examined the effect of lymphopenia in different RT fields. After controlling for all relevant parameters, the effect of lymphopenia (ΔALC/preALC level > 0.88) on survival was most pronounced in the extended field RT group (HR = 5.58) compared to the whole pelvis RT group (HR = 1.20). This finding suggests that we should pay greater attention to the RT-related lymphopenia in individuals who require extended field RT.

It is essential to determine the influence of treatment-induced lymphopenia on survival because it is a modifiable factor. There are several methods to prevent lymphopenia. Reducing the RT field as much as possible may be the simplest strategy to prevent lymphopenia. Although most guidelines do not recommend irradiating the para-aortic area in patients with just pelvic lymph node metastases, the role of prophylactic extended field RT remains controversial [

16,

17,

18]. When paraaortic area irradiation is inevitable, the upper margin of the extended RT field may be adjustable factor [

18,

19]. In this study, T12-L1 was the upper margin in all patients who received extended field RT; however, subrenal vein level (L2-3) could be an option for those with common iliac lymph node metastases or paraaortic lymph node metastases at low level [

20]. Bone-marrow sparing planning employing advanced RT techniques such as IMRT or proton therapy is another way to prevent lymphopenia. Recent systematic reviews reported that pelvic bone marrow-sparing radiotherapy significantly decreased severe lymphopenia in cancer patients [

21,

22]. Proton therapy is remarkably superior in sparing the irradiated volume of the spine and pelvic bone [

23]. Hypofractionation is an additional approach that may be utilized to prevent lymphopenia. Sun et al. showed that nadir-ALC was significantly higher in patients who received hypofractionated RT compared to conventional RT [

24]. However, whether avoiding lymphopenia with these methods could improve survival is another question that requires further investigation.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective study with a small number of patients, and potential bias might exist, although we did our best to adjust for confounders with multivariate analysis. In addition, a dosimetric study of irradiated bone marrow in relation to lymphopenia is lacking. Recent studies indicate that certain dosimetric factor of bone marrow are associated with lymphopenia [

25,

26]. In light of our finding that the RT field is associated with OS, particularly in extended field RT, we will analyze specific dosimetric parameters in a subsequent study. Despite several limitations, this study suggests that radiation oncologists should consider RT-related lymphopenia and try to prevent lymphopenia in cervical cancer patients as much as possible. More research is needed to determine the benefit of bone-marrow sparing IMRT/proton therapy, hypofractionation, or minimizing the RT field in reducing lymphopenia and improving prognosis.

In conclusion, lymphopenia (ΔALC/pre ALC > 0.88) was associated with worse PFS and OS in patients who received RT for cervical cancer; and it was prominent in those who received para-aortic radiation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.K.C. and W.P.; Methodology, B.P. Resources, W.P.; Writing – original draft, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (approval number:2022-11-140).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to its retrospective nature.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Torre, L.A.; Bray, F.; Siegel, R.L.; Ferlay, J.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015, 65, 87–108. [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.W.; Won, Y.J.; Kong, H.J.; Oh, C.M.; Cho, H.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, K.H. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2012. Cancer Res Treat 2015, 47, 127–141. [CrossRef]

- Cho, O.; Chun, M. Management for locally advanced cervical cancer: new trends and controversial issues. Radiat Oncol J 2018, 36, 254–264. [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.G.; Bundy, B.N.; Watkins, E.B.; Thigpen, J.T.; Deppe, G.; Maiman, M.A.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L.; Insalaco, S. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 1144–1153. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, N.; Kusunoki, Y.; Akiyama, M. Radiosensitivity of CD4 or CD8 positive human T-lymphocytes by an in vitro colony formation assay. Radiat. Res. 1990, 123, 224–227. [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, Y.; Fang, P.; Xu, C.; Song, J.; Krishnan, S.; Koay, E.J.; Mehran, R.J.; Hofstetter, W.L.; Blum-Murphy, M.; Ajani, J.A.; et al. Severe lymphopenia during neoadjuvant chemoradiation for esophageal cancer: A propensity matched analysis of the relative risk of proton versus photon-based radiation therapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 128, 154–160. [CrossRef]

- Campian, J.L.; Ye, X.; Brock, M.; Grossman, S.A. Treatment-related lymphopenia in patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Invest. 2013, 31, 183–188. [CrossRef]

- Onal, C.; Yildirim, B.A.; Guler, O.C.; Mertsoylu, H. The Utility of Pretreatment and Posttreatment Lymphopenia in Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients Treated With Definitive Chemoradiotherapy. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2018, 28, 1553–1559. [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; Kang, H.; Kim, W.Y.; Kim, T.J.; Lee, J.W.; Huh, S.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, B.G.; Bae, D.S. Prognostic value of baseline lymphocyte count in cervical carcinoma treated with concurrent chemoradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008, 71, 199–204. [CrossRef]

- Cho, O.; Noh, O.K.; Oh, Y.T.; Chang, S.J.; Ryu, H.S.; Lee, E.J.; Chun, M. Hematological parameters during concurrent chemoradiotherapy as potential prognosticators in patients with stage IIB cervical cancer. Tumour Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317694306. [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, K.; Giangreco, D.; Morrison, C.; Siddiqui, M.; Sinacore, J.; Potkul, R.; Roeske, J. Radiation-related predictors of hematologic toxicity after concurrent chemoradiation for cervical cancer and implications for bone marrow-sparing pelvic IMRT. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011, 79, 1043–1047. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Myoung Noh, J.; Lee, W.; Park, B.; Park, H.; Young Park, J.; Pyo, H. Proton beam therapy reduces the risk of severe radiation-induced lymphopenia during chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A comparative analysis of proton versus photon therapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 156, 166–173. [CrossRef]

- Contal, C.; O'Quigley, J. An application of changepoint methods in studying the effect of age on survival in breast cancer. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 1999, 30, 253–270. [CrossRef]

- Wu, E.S.; Oduyebo, T.; Cobb, L.P.; Cholakian, D.; Kong, X.; Fader, A.N.; Levinson, K.L.; Tanner, E.J., 3rd; Stone, R.L.; Piotrowski, A.; et al. Lymphopenia and its association with survival in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 140, 76–82. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesulu, B.P.; Mallick, S.; Lin, S.H.; Krishnan, S. A systematic review of the influence of radiation-induced lymphopenia on survival outcomes in solid tumors. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2018, 123, 42–51. [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Li, Y.; Ke, G.; Wu, X.; Huang, X. Extended field or pelvic intensity-modulated radiotherapy with concurrent cisplatin chemotherapy for the treatment of post-surgery multiple pelvic lymph node metastases in cervical cancer patients: a randomized, multi-center phase II clinical trial. Transl Cancer Res 2021, 10, 361–371. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.C.; Muller, D.A.; Dutta, S.W.; Corriher, T.J.; Ring, K.L.; Showalter, T.N.; Romano, K.D. Para-Aortic Nodal Radiation in the Definitive Management of Node-Positive Cervical Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 664714. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Park, W. Adjuvant radiotherapy for cervical cancer in South Korea: a radiation oncology survey of the Korean Radiation Oncology Group (KROG 20-06). Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 51, 1107–1113. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Park, W. Patterns of definitive radiotherapy practice for cervical cancer in South Korea: a survey endorsed by the Korean Radiation Oncology Group (KROG 20-06). J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 32, e43. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lin, J.B.; Chang, C.L.; Jan, Y.T.; Chen, Y.J.; Wu, M.H. Optimal prophylactic para-aortic radiotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer: anatomy-based versus margin-based delineation. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 32, 606–612. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesulu, B.; Giridhar, P.; Pujari, L.; Chou, B.; Lee, J.H.; Block, A.M.; Upadhyay, R.; Welsh, J.S.; Harkenrider, M.M.; Krishnan, S.; et al. Lymphocyte sparing normal tissue effects in the clinic (LymphoTEC): A systematic review of dose constraint considerations to mitigate radiation-related lymphopenia in the era of immunotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2022, 177, 81–94. [CrossRef]

- Danckaert, W.; Spaas, M.; Vandecasteele, K.; De Wagter, C.; Ost, P. Impact of radiotherapy parameters on the risk of lymphopenia in urological tumors: A systematic review of the literature. Radiother. Oncol. 2022, 170, 64–69. [CrossRef]

- Dinges, E.; Felderman, N.; McGuire, S.; Gross, B.; Bhatia, S.; Mott, S.; Buatti, J.; Wang, D. Bone marrow sparing in intensity modulated proton therapy for cervical cancer: Efficacy and robustness under range and setup uncertainties. Radiother. Oncol. 2015, 115, 373–378. [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.Y.; Wang, S.L.; Song, Y.W.; Jin, J.; Wang, W.H.; Liu, Y.P.; Ren, H.; Fang, H.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, X.R.; et al. Radiation-Induced Lymphopenia Predicts Poorer Prognosis in Patients With Breast Cancer: A Post Hoc Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial of Postmastectomy Hypofractionated Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020, 108, 277–285. [CrossRef]

- Hara, J.H.L.; Jutzy, J.M.S.; Arya, R.; Kothari, R.; McCall, A.R.; Howard, A.R.; Hasan, Y.; Cursio, J.F.; Son, C.H. Predictors of Acute Hematologic Toxicity in Women Receiving Extended-Field Chemoradiation for Cervical Cancer: Do Known Pelvic Radiation Bone Marrow Constraints Apply? Adv Radiat Oncol 2022, 7, 100998. [CrossRef]

- Corbeau, A.; Kuipers, S.C.; de Boer, S.M.; Horeweg, N.; Hoogeman, M.S.; Godart, J.; Nout, R.A. Correlations between bone marrow radiation dose and hematologic toxicity in locally advanced cervical cancer patients receiving chemoradiation with cisplatin: a systematic review. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 164, 128–137. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).