1. Introduction

Workplace bullying and employee well-being have increasingly become central topics in occupational health psychology, with growing evidence highlighting their profound impact on individual health and organizational functioning. Over the past two decades, researchers have documented how hostile workplace behaviors, such as repeated mistreatment or power harassment, can lead to critical mental and physical health problems, impaired team dynamics, and diminished organizational performance. Conversely, positive psychological states such as work engagement—characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption—have been shown to improve employee motivation, resilience, and productivity. However, existing literature has primarily treated these two constructs in isolation, and intervention-based studies that address both remain scarce, particularly in non-Western contexts such as Japan. Moreover, although the concept of psychological safety has gained traction as a critical antecedent to reduced bullying and enhanced engagement, empirical evidence on how to cultivate such safety in real-world workplace settings remains limited.

This study developed and tested the effectiveness of an intervention program designed to prevent workplace bullying and improve work engagement, defined as a positive, fulfilling work-related state. Workplace bullying not only harms physical and mental health (Leymann & Gustafsson, 1996; Mikkelsen & Einarsen, 2002; Kivimäki et al., 2003; Niedhammer et al., 2006) but also causes indirect damage such as a deteriorating work environment, reduced productivity, and increased turnover intentions (Nielsen & Einarsen, 2012). In contrast, higher work engagement is associated with better physical and mental health, stronger commitment and performance, and lower turnover intentions (Hakanen et al., 2008; Shimazu et al., 2015), benefiting both employees and organizations. In Japan, workplace bullying—often referred to as power harassment—has been the leading cause of civil individual labor dispute consultations for the past decade. It also ranked as the most common cause of mental disorder-related workers’ compensation claims in 2021, underscoring its status as a pressing social issue. Despite the urgent need for preventive measures and intervention research, few studies in Japan have demonstrated effective workplace bullying interventions. Most occupational stress research has traditionally focused on issues such as overwork and extended working hours, with limited practical or workplace-based intervention studies (Makita & Yamamoto, 2013). Similarly, most work engagement studies remain theoretical (Bakker & Leiter, 2010), and few have validated effective strategies for improving engagement in practice.

Workplace bullying and work engagement represent opposing workplace experiences, one negative, the other positive. Preventing bullying is expected not only to mitigate its harmful effects but also to help maintain and enhance work engagement (Kobayashi et al., 2024). Based on previous research (Law et al., 2011), fostering psychological safety is a shared approach to achieving both outcomes. Psychological safety refers to a team’s shared belief that the workplace is safe for interpersonal risk-taking (Edmondson, 1999), where individuals can express opinions openly without fear of rejection, punishment, or conflict. Such environments promote mutual respect, openness, and constructive dialogue, enhancing learning behaviors, engagement, and organizational performance (Edmondson, 1999). Psychological safety is also crucial for long-term organizational sustainability. Although practical efforts to enhance psychological safety are underway in Japan, there remains a lack of evidence-based intervention studies, signaling the need for further research.

The openness of managers and leaders, their approachability, and their ability to create opportunities for dialogue are regarded as key antecedents of psychological safety (Edmondson et al., 2004). Many practices aimed at enhancing psychological safety focus on managerial behavior. However, research suggests that among Japanese workers, the mere permission to express opinions does not necessarily translate into actual expression (Ochiai & Otsuka, 2022). Therefore, in addition to managerial openness and empathy, subordinates must also develop the skills and willingness to communicate their ideas and opinions. Psychological safety is associated with factors such as a proactive approach to problem solving, high stress tolerance, emotional stability, supportive interpersonal relationships, and interdependence in collaborative tasks (Edmondson & Lei, 2014). Based on this, it is suggested that coping strategies for proactive problem-solving, effective communication skills across various workplace contexts, and the cultivation of mutually supportive relationships through consultation and requests contribute to a high level of psychological safety. In turn, this promotes the prevention of workplace bullying and the enhancement of work engagement. Since psychological safety reflects a group-level belief, shared within organizations or teams, that one can speak openly and without fear (Edmondson & Lei, 2014), programs should be implemented at the group level rather than the individual level, fostering a shared understanding.

Therefore, this study developed an intervention program for general employees aimed at building psychological safety to prevent workplace bullying and enhance work engagement. I assessed its multifaceted effects among workers at a pharmaceutical company using a cluster randomized controlled trial.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

The survey and intervention were conducted with the cooperation of a pharmaceutical company, referred to here as Plant A. Plant A is one of the company’s pharmaceutical manufacturing sites and includes five major divisions: manufacturing, production engineering, quality control, quality assurance, and administration. The manufacturing sector in Japan is known for its high incidence of mental health issues (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2023). In pharmaceutical production, the demands for quality, cost reduction, and supply stability contribute to high work stress. Plant A was considered an appropriate target for the survey because high-stress environments are more prone to power harassment (Baillien et al., 2011), and limiting the study to a single site helped control for regional and organizational differences. No conflict of interest is declared. All employees at Plant A were surveyed at three time points: July 2023, November 2023, and February 2024. Since the study examined intervention effects on indicators closely related to organizational climate, such as workplace bullying and psychological safety, mixing intervention and control groups within the same department was considered inappropriate. Therefore, a cluster randomized controlled trial design was used, with departments randomly assigned to intervention or control groups. Employees in intervention departments received a face-to-face program in August 2023 and an e-learning follow-up in September 2023. Surveys were conducted using Cuenote Survey, a cloud-based web questionnaire platform. The questionnaire explained the study’s purpose, voluntary participation, anonymity, lack of individual consequences, support resources for any issues, and plans for publication. Only participants who selected “I agree” proceeded with the survey. The study received ethical approval from the Kyushu University Ethical Review Committee (202112).

The number of subjects collected at each survey time point was as follows: Time 1 – 494 (valid responses: 392), Time 2 – 488 (394), and Time 3 – 488 (395). In Study 1, 256 participants (115 males, 141 females; mean age = 37.8 ± 11.6 years) who completed all three surveys were included in the analysis. Participants with incomplete responses were excluded to enable the use of difference scores between work engagement and workplace bullying from T1 to T3. In Study 2, 368 participants were included in the analysis (

Table 1), excluding those who did not consent, transferred departments during the study, or submitted incomplete responses.

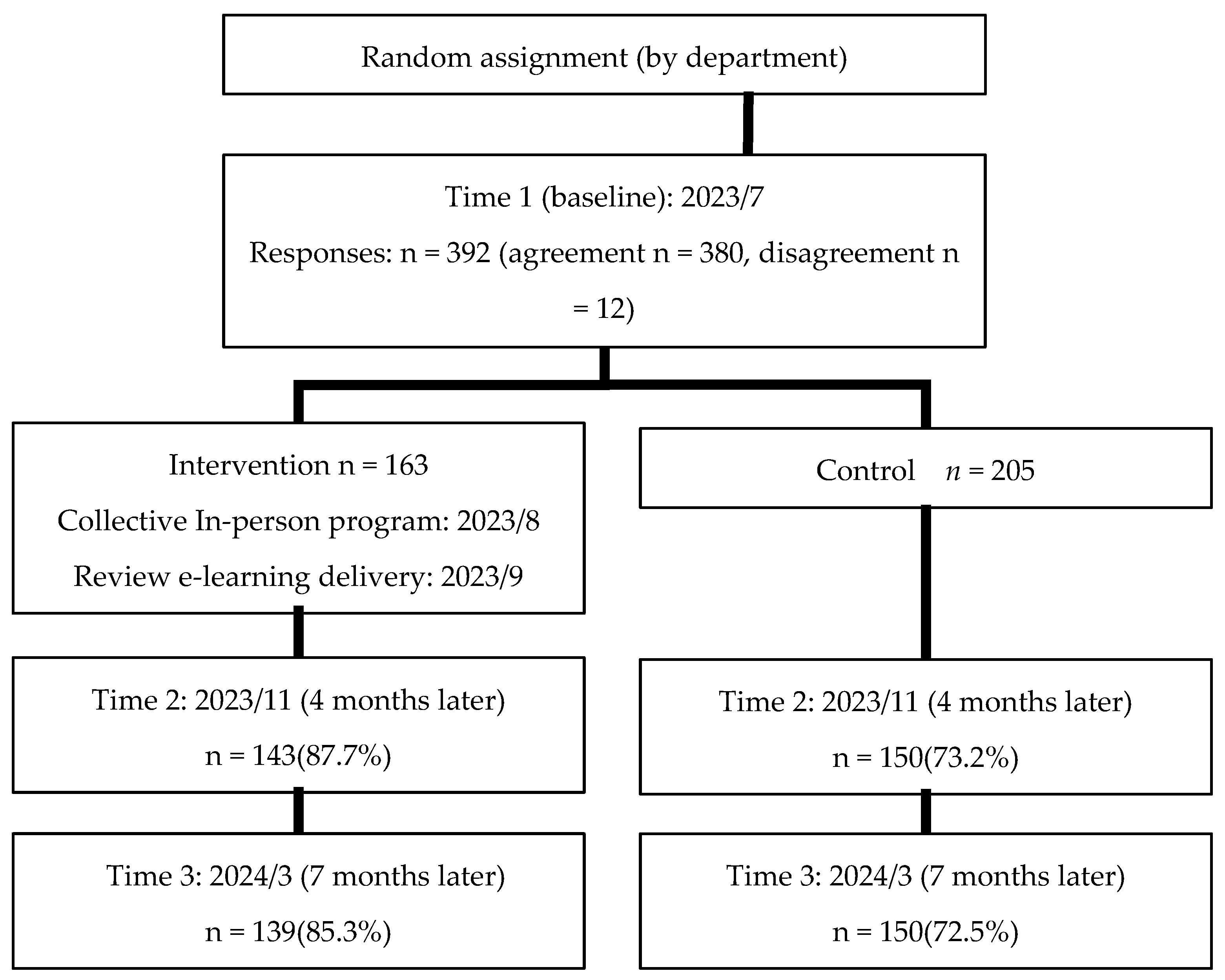

A flowchart of participants in Study 2 is shown in

Figure 1. The intervention program was delivered to the general employee group (n = 156) assigned to the intervention condition. Given that leadership traits and behavior are central to fostering psychological safety (Edmondson et al., 2004), a separate one-time training for all managers at Plant A was conducted in July 2023. This training focused on anger management and empathetic leadership, and its effectiveness was examined (Kobayashi et al., 2024). However, as it was conducted approximately a year before this study and included all managers, it was considered to have no differential effect on the intervention versus control group conditions in the present trial.

2.2. Intervention Program

A face-to-face intervention program was implemented with general employees (n = 156) in the intervention group to equip them with coping strategies for interpersonal stress and enhance communication skills for expressing opinions to supervisors and colleagues (

Table 2,

Figure 2). To minimize burden and maximize feasibility, the program was designed as a one-time session lasting three-five hours. In this study, a three-hour face-to-face program was conducted by clinical and licensed psychologists, combining lecture, group work, individual tasks, and hands-on training. To reduce infection risk and minimize workflow disruption, sessions were held across six groups (20–30 participants each), all within the same week to ensure consistency in content and delivery.

The program consisted of four components. Program 1 introduced three interpersonal stress-coping strategies, followed by specific instruction and exercises in Programs 2 through 4. Program 2 focused on stress coping using cognitive-behavioral techniques. Participants worked through interpersonal stress examples to reframe unhelpful thought patterns into realistic, objective perspectives. They also explored their own thought habits and practiced mindfulness to regulate emotions such as anxiety and anger. Program 3 introduced self-care techniques, including breathing exercises and relaxation methods. Program 4 focused on assertion, a communication strategy for clearly expressing thoughts and feelings to reduce stressors. Participants explored four situational examples, including (1) making a difficult request, (2) giving clear guidance, (3) feeling under-recognized, and (4) asking a colleague to adjust work expectations, and discussed how to express themselves effectively using assertive techniques. Sample responses and key communication points were provided.

The program had two primary aims: (1) to enhance individual communication and stress-coping skills, which are key factors in psychological safety and (2) to serve as a shared learning space where colleagues gained mutual understanding of the importance of sincere and necessary communication through extensive group work and practical activities.

To reinforce learning and workplace application, an e-learning review video was sent to intervention participants about one month after the session. To prevent contamination, participants were asked not to share program content with those in the control group. Control group employees were informed that they would receive the same training after the study period concluded.

2.3. Questionnaire

2.3.1. Individual Attributes

Participants provided demographic information, including self-identified gender (male, female), age, job position (general or managerial), department (1–14), years of service, and job type (production/technical, clerical, research/specialized, or other).

2.3.2. Work Engagement

Work engagement was assessed using the Japanese short version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Shimazu et al., 2008), which consists of nine items across three subscales, including vigor (e.g., “I feel energized when I work”), dedication (e.g., “I feel proud of my work”), and absorption (e.g., “I am enthusiastic about my work”), with three items per subscale. A seven-point Likert scale (0 = “never” to 6 = “always/every day”) was used. Reliability and validity have been verified. Scores were averaged to compute an overall engagement score (range: 0–6), with higher scores indicating greater engagement.

2.3.3. Experience of Workplace Bullying

The Workplace Power Harassment Perceptions and Experiences Scale (Nii et al., 2018) was used, developed in accordance with the Japanese definition of workplace bullying. The scale comprises 18 items across three dimensions: a) twelve items on bullying behaviors (e.g., “When angry, I lash out—punching, kicking, etc.,” or “Assigning clearly unnecessary tasks or withholding work out of dislike”), b) four items on bullying situations (e.g., “Subordinates are intimidated by their superiors”), and c) two items on bullying-related attitudes (e.g., “Superiors dismiss differing opinions or complaints”). Participants responded to two types of questions: (1) experience of workplace bullying over the past six months (1 = “never,” 2 = “once,” 3 = “repeatedly”) and (2) perception of exposure to bullying conditions (1 = “not applicable,” 2 = “applicable if repeated,” 3 = “applicable even once”). For analysis, subscale scores were averaged, resulting in bullying experience scores ranging from 0 to 3.

2.3.4. Psychological Safety

The Japanese version of the Workplace Psychological Safety Scale (Sasaki et al., 2022) was used. This is a translated and validated version of the original Psychological Safety Scale (O’Donovan et al., 2020), with its target population expanded to include general workers. As such, all employees could serve as survey participants. The scale includes nine items related to team leaders or supervisors (e.g., “I can communicate my opinions about work-related problems to the team leader [or supervisor]”), seven items concerning colleagues and other team members (e.g., “I feel comfortable telling my colleagues about mistakes I have made in this team”), and three items referring to the team as a whole (e.g., “We can exchange information with each other about work problems in the team”). Subscale scores were calculated by dividing the total score of each section by the number of items in that section. The overall psychological safety score was calculated by dividing the combined total by 19, the total number of items.

2.3.5. Brief Scale of Coping Characteristics for Workers (BSCP)

The BSCP is an 18-item, six-subscale instrument developed to measure coping characteristics of workers under stress (Kageyama et al., 2004). Its reliability and validity have been confirmed. The subscales include active solutions (e.g., “I investigate causes and try to solve problems”), seeking help for solutions (e.g., “I consult with trusted people for solutions”), changing perspective (e.g., “I have hope that I can manage”), changing mood (e.g., “I distract myself with hobbies and entertainment”), and emotional expression involving others (e.g., “blaming the person who put me in that situation”), and avoidance and suppression (e.g., “letting go or postponing the problem”). These subscales reflect coping categories identified in previous research (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Higher scores indicate more frequent use of those coping behaviors.

2.4. Analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0 was used for data analysis. To examine changes in work engagement, workplace bullying experiences (behaviors, attitudes, and conditions), psychological safety (supervisors, peers, and team), and BSCP subscales (active solutions, help-seeking, perspective change, mood change, emotional divergence, avoidance/suppression), linear mixed model analyses were conducted. Analyses were stratified by job position (managerial vs. general) because the intervention was implemented only for general employees. This separation allowed us to isolate the program’s effects from any influence associated with managers who did not receive the intervention. Each outcome variable was treated as the dependent variable, with intervention condition (yes/no) and survey time point (Time 1, Time 2, Time 3) as fixed effects. The interaction between intervention status and time point was used to assess the intervention’s effect, specifically examining whether significant changes occurred from the baseline (Time 1) to post-intervention points (Time 2 and Time 3). Additionally, a mediation analysis was conducted to explore which components of the intervention contributed to observed effects. In this analysis, intervention status (1 = present, 0 = absent) was the independent variable, psychological safety served as the mediator, and consultation for problem solving was the dependent variable. Indirect effects were evaluated using the bias-corrected bootstrap method with 2,000 samples to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI).

3. Results

3.1. Basic Analysis

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics for the intervention and control groups at each time point in the study.

3.2. Intervention Effects

Results of the linear mixed model analysis for each dependent variable are shown in

Table 4 and

Figure 2.

Work Engagement: No significant differences were found among managers. For general employees, the interaction between intervention presence and time of survey showed a trend toward significance (F(2, 689.42) = 2.95, p = .053). A simple main effect test revealed a significant effect of survey time in the control group (F(2, 381.73) = 6.07, p = .003). Bonferroni’s multiple comparison indicated significant decreases in work engagement at Time 2 and Time 3 compared to Time 1 (Time 2: p = .008, d = 0.29, 95% CI [−0.58, −0.07]; Time 3: p = .004, d = 0.28, 95% CI [−0.61, 0.10]). No significant main effects were observed in the intervention group.

Workplace Bullying: Among managers, no significant effects were found. For general employees, a significant interaction was found for workplace bullying conditions (F(2, 666.55) = 9.46, p < .001). Simple main effect tests showed significant time effects in both intervention (F(2, 356.34) = 5.67, p = .004) and control groups (F(2, 304.97) = 4.44, p = .013). Bonferroni’s test revealed a significant decrease in workplace bullying conditions at Time 3 in the intervention group (p = .006, d = 0.28, 95% CI [−0.26, −0.04]), and a significant increase at Time 3 in the control group (p = .002, d = 0.23, 95% CI [0.05, 0.25]). No significant interaction was found for bullying behaviors or attitudes.

Psychological Safety: For general employees, significant interactions were found for psychological safety toward supervisors (F(2, 653.55) = 7.25, p < .001) and teams (F(2, 637.88) = 5.27, p = .005). No significant results were observed for managers. Simple main effect testing showed a trend for the intervention group on supervisor-related psychological safety (F(2, 289.17) = 2.90, p = .056) and a significant effect for the control group (F(2, 341.91) = 5.15, p = .006). Psychological safety toward supervisors significantly increased at Time 3 in the intervention group (p = .033, d = 0.22, 95% CI [0.01, 0.43]), and decreased in the control group (p = .003, d = 0.22, 95% CI [−0.51, −0.09]). For team-level psychological safety, the intervention group showed a significant main effect (F(2, 291.01) = 3.23, p = .041), and the control group showed a near-significant trend (F(2, 340.36) = 2.56, p = .008). Psychological safety for the team significantly increased at Time 3 in the intervention group (p = .023, d = 0.20, 95% CI [0.03, 0.48]), while it significantly declined in the control group (p = .05, d = 0.14, 95% CI [−0.44, 0]). No significant interaction was found for psychological safety with coworkers.

BSCP (Coping Characteristics): No significant differences were found for managers. For general employees, significant interactions were found in consultation for problem solving (F(2, 653.65) = 4.64, p = .01) and mood regulation (F(2, 639.46) = 3.99, p = .019). Simple main effect tests showed a significant increase in consultation behaviors in the intervention group (F(2, 289.39) = 11.88, p < .001; p < .001, d = 0.30, 95% CI [0.13, 0.41]), with no significant change in the control group. For mood regulation, effects trended toward significance in both groups (intervention: F(2, 293.71) = 2.81, p = .062; control: F(2, 336.40) = 2.90, p = .057). Bonferroni’s test showed a marginal increase at Time 3 in the intervention group (p = .054, d = 0.18, 95% CI [−0.002, 0.29]) and at Time 2 (p = .066, d = 0.06, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.25]), though effect sizes were small. No significant interactions were found for other BSCP subscales.

In summary, the intervention program significantly improved consultation for problem solving among participating general employees. Psychological safety toward both supervisors and teams also increased, while experiences of workplace bullying, particularly intimidation by superiors, decreased. Although work engagement declined in the control group, it remained stable in the intervention group, suggesting the program helped maintain engagement, though it did not significantly improve it. Hypotheses 2-1 and 2-2 were partially supported.

3.3. Complementary Analysis

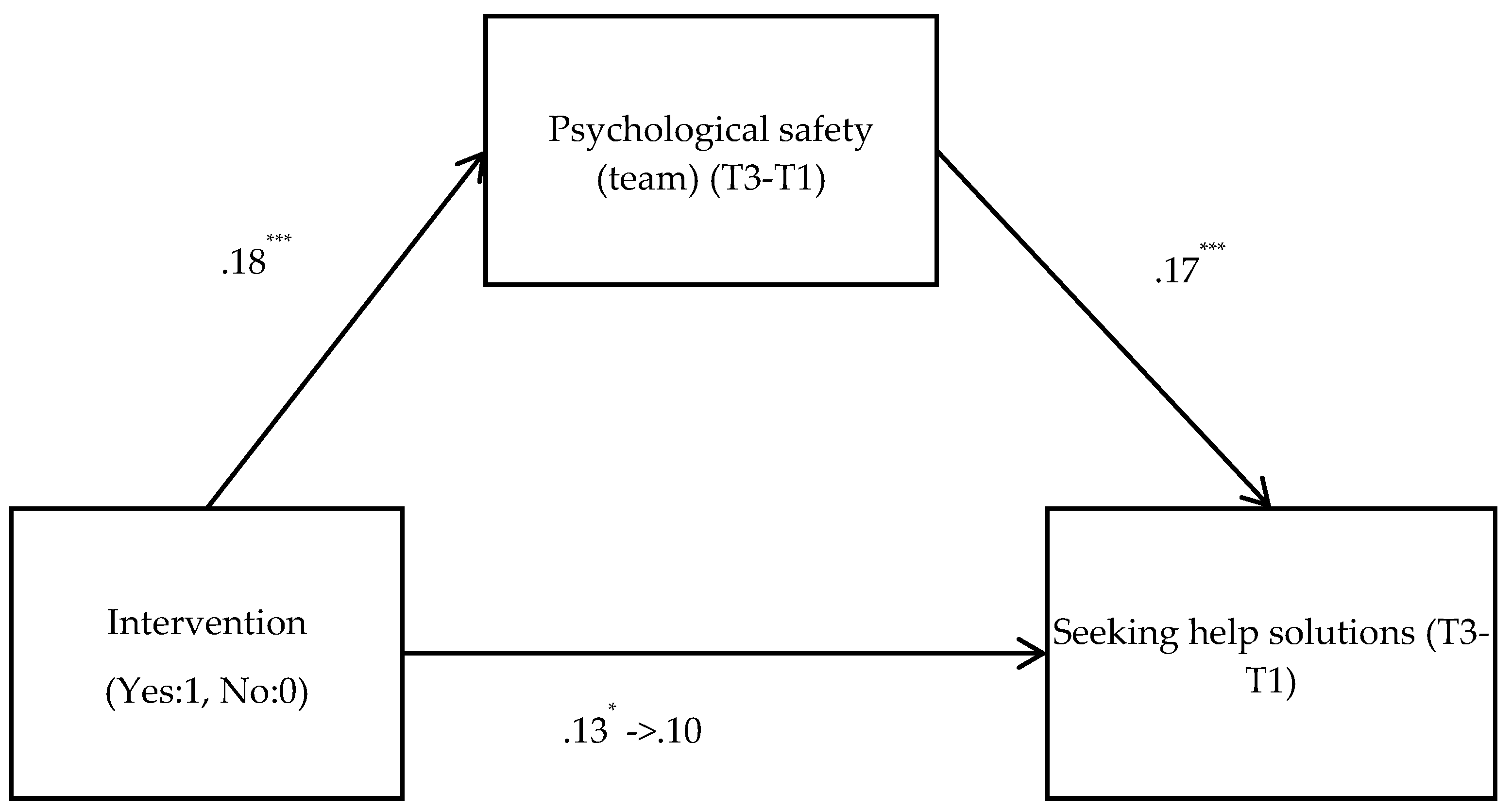

A mediation analysis was conducted to examine whether the intervention promoted consultation behaviors through improved psychological safety, or whether the intervention fostered consultation as a coping skill that then enhanced psychological safety. Results (Figure X) indicated that the intervention’s effect on problem-solving consultation was fully mediated by psychological safety (b = .049, BootSE = .032, 95% CI [.001,.109]). No significant mediation effect was found when the mediating variable was consultation and the dependent variable was psychological safety.

4. Discussion

This study developed an intervention program for general employees focused on building psychological safety to help prevent workplace bullying and enhance work engagement, and evaluated its multifaceted effects through a cluster randomized controlled trial. The findings showed that the program increased consultation behavior for problem solving as a stress-coping strategy, enhanced psychological safety toward superiors and teams, and reduced experiences of workplace bullying, characterized by excessive fear of superiors and withdrawal. Supplemental analyses supported Hypotheses 1 and 2. Notably, the intervention did not improve stress coping first and then lead to psychological safety; rather, psychological safety increased first, which then led to more consultative behaviors. General employees who participated in the program became more comfortable expressing opinions without excessive fear or hesitation toward supervisors and team members. Their tendency to consult others and take proactive steps in stressful situations also increased. These outcomes likely reflect not only improved individual communication skills but also broader organizational effects, as the group-based format allowed participants to exchange ideas and foster mutual understanding in real time. It is believed the program contributed to psychological safety and reduced workplace bullying by helping participants recognize the importance of open and sincere communication regarding consultations, requests, and reporting, along with strategies for doing so. While the intervention included several components, the assertion module may have played a key role, given its direct relevance to psychological safety, bullying prevention, and problem-solving consultation. Future studies should evaluate the specific contributions of individual modules to determine which elements are most effective. Although work engagement significantly declined in the control group, it remained stable in the intervention group, suggesting that the program may have buffered against decline, even if it did not enhance engagement. External organizational factors could have contributed to low initial work engagement in the intervention group. In Study 1, a reduction in bullying victimization and an increase in psychological safety were shown to support higher engagement. However, since the COVID-19 pandemic, employee engagement, particularly in small- to medium-sized enterprises with fewer than 900 employees, has been declining (Co, 2025), which may explain why engagement in the intervention group did not improve. Thus, maintaining engagement may represent a meaningful effect of the program under current conditions.

One limitation of this study is that all participants were from a single company and location, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. While focusing on one site allowed for better control of confounding variables, future research should include multiple companies, occupations, and industries. Additionally, because no clear improvement in work engagement was observed, further refinement of the program and study design is needed, including increasing the number of follow-up assessments to capture longer-term effects.

These findings have important implications for practice and policy. At the organizational level, this study demonstrates that psychological safety is a byproduct of individual resilience and can be actively cultivated through targeted, skill-based interventions. Companies should consider integrating such programs into their routine training for employees—to prevent workplace bullying and promote a culture of open communication and collective problem-solving. From a policy perspective, these results suggest that psychosocial risk management strategies mandated by occupational health regulations could benefit from explicitly incorporating psychological safety as a core objective. Considering the stability of work engagement in the intervention group despite broader downward trends, such programs may serve as a valuable buffer in times of organizational stress or economic uncertainty. Scaling this kind of evidence-based intervention across diverse sectors and company sizes could contribute to broader improvements in employee well-being and productivity.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from The Occupational Health Promotion Foundation and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 23KJ1686.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyushu University (protocol code 2023-002 and date of approval 2023/4/13).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns and confidentiality agreements. Access to the data is restricted in order to protect participants’ personal information in accordance with ethical guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all the employees who generously participated in this study. The author wishes to acknowledge Masahiro Irie, Shotaro Amano, Manami Tsukamoto, and Kenji Horino for their contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baillien, E., De Cuyper, N., & De Witte, H. (2011). W. Job autonomy and workload as antecedents of workplace bullying: A two-wave test of Karasek’s job demand control model for targets and perpetrators. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 191–208. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2010). Where to go from here: Integration and future research on work engagement. In A. B. Bakker, & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 181–196). Psychology Press. [CrossRef]

- Co, P. R. A. C. (2025). Employment and growth fixed-point survey of 10,000 working people. Available online: https://rc.persol-group.co.jp/thinktank/spe/pgstop/pgs/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. C., Kramer, R. M., & Cook, K. S. (2004). Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: A group-level lens. Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches, 12, 239–272.

- Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology & Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 23–43. [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ahola, K. (2008). The job demands-resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work & Stress, 22(3), 224–241. [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, T., Kobayashi, T., Kawashima, M., & Kanamaru, Y. (2004). Development of the Brief Scales for Coping Profile (BSCP) for workers: Basic information about its reliability and validity. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi, 46(4), 103–114. [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, M., Virtanen, M., Vartia, M., Elovainio, M., Vahtera, J., & Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2003). Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 60(10), 779–783. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M., Yamaguchi, H., Amano, S., & Irie, M. (2024). Examination of factors that prevent power harassment and improve work engagement: Focusing on perspective taking, anger expression, and workplace resources. Japanese Association of Industrial / Organizational Psychology Journal, 1, 15–34.

- Law, R., Dollard, M. F., Tuckey, M. R., & Dormann, C. (2011). Psychosocial safety climate as a lead indicator of workplace bullying and harassment, job resources, psychological health and employee engagement. Accident; Analysis & Prevention, 43(5), 1782–1793. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Leymann, H., & Gustafsson, A. (1996). Mobbing at work and the development of post-traumatic stress disorders. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 251–275. [CrossRef]

- Makita, K., & Yamamoto, S. K. (2013). Tomomi A pilot study of the relationship between 2 types of trainings for building up a better working environment and its effectiveness in preventing workplace bullying. Japan Bulletin Traumatic Stress Studies, 9, 31–38.

- Mikkelsen, E. G., & Einarsen, S. (2002). Relationships between exposure to bullying at work and psychological and psychosomatic health complaints: The role of state negative affectivity and generalized self-efficacy. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 43(5), 397–405. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2023). Overview of the 2021 occupational safety and health survey (fact-finding survey). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/r03-46-50b.html (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- Niedhammer, I., David, S., & Degioanni, S. (2006). Association between workplace bullying and depressive symptoms in the French working population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 61(2), 251–259. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. B., & Einarsen, S. (2012). Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work & Stress, 26(4), 309–332. [CrossRef]

- Nii, M., Tsuda, A., Tou, K., Yamahiro, T., & Irie, M. (2018). Development of a new power harassment questionnaire in workplaces. Stress Management Research, 14(2), 78–90.

- Ochiai, Y., & Otsuka, Y. (2022). Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the psychological safety scale for workers. Industrial Health, 60(5), 436–446. [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, R., Van Dun, D., & McAuliffe, E. (2020). Measuring psychological safety in healthcare teams: Developing an observational measure to complement survey methods. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20(1), 203. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, N., Inoue, A., Asaoka, H., Sekiya, Y., Nishi, D., Tsutsumi, A., & Imamura, K. (2022). The survey measure of psychological safety and its association with mental health and job performance: A validation study and cross-sectional analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 19(16), 9879. [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, A., Schaufeli, W. B., Kamiyama, K., & Kawakami, N. (2015). Workaholism vs. work engagement: The two different predictors of future well-being and performance. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 22(1), 18–23. [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, A., Schaufeli, W. B., Kosugi, S., Suzuki, A., Nashiwa, H., Kato, A., Sakamoto, M., Irimajiri, H., Amano, S., Hirohata, K., Goto, R., & Kitaoka-Higashiguchi, K. (2008). Work engagement in Japan: Validation of the Japanese version of the Utrecht work engagement scale. Applied Psychology, 57(3), 510–523. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).