1. Introduction

Workplace bullying, or mobbing, is a progressively acknowledged problem that has substantial personal, organisational, and societal ramifications. This problem compromises both employee well-being and the productivity and reputation of organisations. The detrimental consequences of mobbing encompass mental and physical health issues, such as anxiety, sadness, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and even somatic conditions like heart disease. These repercussions affect organisations, resulting in diminished employee engagement, reduced performance, and heightened turnover, culminating in financial losses. Mobbing adversely affects organisational culture, obstructing innovation and collaboration.

The occurrence of mobbing in public administration has garnered increasing attention due to the unique demands and rigid hierarchical structures that typify bureaucratic institutions [

1,

2]. While the phenomenon has been investigated in various sectors and countries, there remains a notable lack of empirical research specifically addressing mobbing within the Greek public administration.

Greece represents a compelling and underexplored case in this context. Following a prolonged period of economic crisis and austerity measures, Greek public institutions have experienced heightened organisational strain, reduced resources, and growing rigidity. These systemic pressures, combined with deeply entrenched hierarchical norms and limited internal mobility, may create conditions that exacerbate mobbing. Furthermore, Greece’s legislative and institutional responses to workplace bullying are still developing, leaving many employees vulnerable and without effective recourse. Studying this environment offers valuable insights not only for Greece but also for other countries grappling with similar bureaucratic and socio-economic challenges.

This deficiency in the literature and the urgency of the national context prompt our investigation. This research examines the manifestation of mobbing across various roles and departments within the Greek public sector, diverging from the predominant focus in existing studies on corporate or educational settings. Furthermore, although global research frequently highlights gender or racial disparities in bullying [

3], our data suggest alternative patterns in the Greek context, such as links to education and tenure, offering a novel contribution to the discourse.

This article has two objectives: (1) to investigate the causes and dynamics of mobbing in Greek public administration as experienced by employees, and (2) to propose practical, evidence-based strategies to reduce its prevalence. The study contributes to the field in three main ways. First, it provides a national-level analysis based on quantitative data gathered via a standardized questionnaire distributed across a wide spectrum of public sector personnel. Second, it identifies demographic and organisational factors—such as seniority and educational attainment—that exhibit a strong correlation with mobbing, contrasting with trends observed in international literature. Third, it offers targeted policy recommendations tailored to Greece’s administrative realities, which are currently underrepresented in both Greek and European research.

While studies such as [

4] have examined mobbing in European public sectors, they do not address the cultural and institutional specificities of the Greek bureaucracy. Our research addresses this regional and contextual gap through a quantitative survey methodology that captures the lived experiences of public administration employees. Key findings reveal that mobbing disproportionately affects individuals with higher educational qualifications and those with less than ten years of service. Organisational dysfunction and interpersonal envy emerged as primary contributing factors.

This paper is organised as follows:

Section 2 examines pertinent existing literature.

Section 3 delineates the approach, encompassing sample design and questionnaire framework.

Section 4 delineates the analysis of the findings. The last section of this article is the conclusion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Mobbing Definition

Mobbing, or workplace bullying, is a widespread problem that influences employees in all areas, including public organisations. The ramifications of mobbing are significant, influencing both individuals and organisations. Current evidence underscores the adverse impacts on employee well-being, organisational efficacy, and societal expenses. This review rigorously analyses the evidence on mobbing within public institutions, including its sources, effects, and mitigation techniques.

The term “mobbing” is used in order to describe the workplace bullying. It was initially used by Konrad Lorenz, who was an ethologist and zoologist, and used the term in order to describe the attacks of a herd of animals to a larger animal [

5]. The same terminology was used in 1969 by Dr Paul Heinemann, with which he characterized the phenomenon of bullying among students of a Norwegian school as the beginning of possible future adverse social phenomena [

6]. Following the aforementioned researchers, [

7] observed that corresponding behavior was taking place in the workplace, too. Therefore, the term “mobbing” described the bullying within the place of work, noting in a relevant to the subject article [

7] that the major difference between the terms “bullying” and “mobbing” is that in the first instance, which mainly takes place in school environments, there is physical violence accompanied by threats, while in the second instance no physical harassment takes place, but more psychological and social pressure [

7,

8]. An example could be the case of the employee who is alienated from their environment of work [

7,

8]. It must be noted, however, that some of the phenomenon researchers do not agree with the distinction between the terms and use them interchangeably [

9].

It is also worth pointing out that the terminology used for the description of the phenomenon in different countries of the world, varies. In the United Kingdom, Australia and the United States of America the phenomenon is called “workplace bullying”, while in Belgium, Spain and France it is described as “moral harassment”. In Canada, it is named “psychological harassment”, while in Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Italy it is described with the term “mobbing”. In Germany, it is called “mobbing”, as well as “psychoterror” [

10].

With regards to the term “mobbing”, Leymann, one of the pioneers in mobbing research, who used the term “work terror” [

7] to describe the phenomenon, defined that mobbing is the situation in which the person who is the victim is subjected to a type of communication that stigmatizes the recipient and violates their human rights [

7]. The specific communication can be characterized as immoral and at the same time hostile, with moral perpetrators being one or a group of abusers who direct their victim to such a position, so that they are not able to defend themselves and to remain in this situation due to the bullying that takes place [

7,

11]. In the end, the victim can be driven away or resign from their job [

7]. For this reason, one of the more recent researchers, [

12], implicitly agrees with Leymann and specifically mentions that this kind of bullying is one of the most serious forms of violation of the individual’s rights regarding work, society and their financial status. This opinion is expressed by earlier, as well as later researchers [

13] pointed out in her article that this phenomenon stigmatizes the employee and violates their rights as a citizen.

[

9], defined the workplace bullying as harassment, threat, resentment, social isolation or even delegating tasks that are offensive to the position and the knowledge of the victim, through which the victim ends up feeling disadvantaged or in an inferior position In some cases, apart from the above, the perpetrators comment on the victim behind their back and apply on them various kinds of pressure [

14]. In Zapf’s aforementioned article, it was further pointed out that in order for a case to be considered as mobbing, the phenomenon must be repeated at least once per week, but it must also last for a long time, which means that it should have at least six months duration [

9]. This point of view echoes [

7] definition in his relevant article where it is demonstrated that in the cases of the phenomenon occurrence, the duration and frequency play a major role. The frequency is defined by [

7] as at least once per week for a period of at least six months. [

15], also define as criteria the extent to which the malicious conduct is systematic, the severity of the mobbing, the degree to which the victim is subjected to the specific behavior so that they get isolated, as well as the extent to which the mobbing can cause harm to the victim’s health and well-being.

The Convention that was drawn up by the International Labour Organisation defines the “violence and harassment” at work [

16] from a slightly different point of view, as heaps of unacceptable behavior and bullying. These phenomena occur either as isolated incidents or are repeated, resulting in physical, psychological, sexual, as well as financial damage, while it may include violence based on matters of gender. Mobbing appears on both the public and the private sector [

16]. Other researchers have occasionally formulated similar definitions, like in the case of [

17] who characterized the mobbing as continuous and intense anxiety, which is experienced by the employees-victims and it is due to the adverse actions of a specific person, having negative sanctions for the employee, as well as the organisation and the society.

Researchers who have carried out studies with regards to the phenomenon of mobbing, have concluded that mobbing is separated in three categories. Specifically, [

18] came to the conclusion that the first category concerns the vertical mobbing, which occurs when the perpetrator is the Supervisor/Manager and the victim is the employee. The second category is about horizontal mobbing, which occurs only when a group of colleagues is the perpetrator. The third category is related to upward mobbing, where the employees bully the manager. [

19] also separated mobbing in two categories, which are the vertical and the horizontal mobbing. [

18] specifically determined that the first type pertains to vertical mobbing, in which the perpetrator is the Supervisor/Manager and the victim is the employee. The second category pertains to horizontal mobbing, which transpires when a collective of colleagues harasses an individual. The third kind, upward mobbing, transpires when subordinates harass their superior. This classification aligns with Leymann's [

7] results, which characterise mobbing as harassment perpetrated by superiors or colleagues within the organisation. Additionally, [

19] classified mobbing into two primary categories: vertical and horizontal mobbing, emphasising the significance of power dynamics in workplace harassment. Other scholars, like [

37] and [

15], have likewise underscored the importance of power disparities in these manifestations of workplace bullying. Moreover, certain research have suggested other subcategories, such as peer mobbing [

20] and organisational mobbing, which considers wider systemic elements influencing the issue [

21]. Other scholars, including [

15], have highlighted the interaction between these various forms and the environment of mobbing, indicating that organisational culture and leadership styles substantially affect the frequency of each type [

22].

Nonetheless, although these first definitions offer significant historical context, the discrepancies in language throughout nations and academic traditions hinder the establishment of a cohesive theoretical framework. For example, while Leymann highlights psychological abuse, others like [

9] encompass a wider array of behaviours. This mismatch may obstruct cross-national comparison studies and restrict the applicability of mitigation techniques across various contexts. Moreover, Leymann's frequency requirements (a minimum of once per week for six months) are frequently referenced; however, recent research (e.g., [

14]) challenges the notion that these levels adequately account for shorter-term yet significantly detrimental occurrences. This highlights difficulties about the operationalisation of mobbing in research, indicating a necessity for more adaptable or contextually sensitive definitions. The categorisation of mobbing into vertical, horizontal, and upward varieties [

18] is beneficial; nonetheless, the intersection with organisational and systemic mobbing [

21] is sometimes insufficiently examined. This suggests a potential gap in the literature, wherein the wider institutional or cultural background facilitating mobbing is inadequately explored.

2.2. Mobbing in Public Institutions

The occurrence of mobbing at public institutions has garnered heightened attention during the past few decades. Research consistently indicates that mobbing in public sectors adversely affects both employees and the overall efficacy of the organisations. Commonly claimed causes of mobbing include organisational culture, hierarchical structures, leadership styles, and workplace stress [

23,

24].

Public institutions, defined by inflexible hierarchies and bureaucratic frameworks, may intensify power disparities, fostering conditions conducive to mobbing behaviours. Employees in high-stress settings, such as public healthcare or administration, are more vulnerable to workplace bullying. [

25] and [

26] have identified a correlation between mobbing and inadequate organisational management, as well as a deficiency in transparency inside public institutions. Employees subjected to mobbing often indicate inadequate communication from management and a culture of silence that neglects to confront bullying behaviours [

17].

Research across several nations has revealed differing degrees of mobbing inside public institutions. [

18] discovered that public sector personnel in Eastern Europe experienced elevated instances of bullying relative to their private sector counterparts. The majority of studies primarily concentrate on descriptive or correlational data. There is scant causal research directly correlating specific public-sector management methods with the occurrence of mobbing. Furthermore, cross-national research (e.g., [

18]) indicates elevated rates of mobbing in Eastern Europe; however, it is uncertain whether these results represent actual frequency disparities or variations in cultural and systematic reporting practices. Moreover, the phenomenon of organisational silence—where employees abstain from reporting due to apprehension—is frequently acknowledged yet seldom quantified empirically, constraining comprehension of its actual magnitude. A significant deficiency in the literature is the lack of longitudinal studies monitoring mobbing from initiation to resolution.

2.3. Impact of Mobbing on Individuals

The repercussions of mobbing on individuals are extensively recorded in the literature. Victims of mobbing endure several psychological consequences, such as despair, anxiety, diminished self-esteem, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD [

27]. Mobbing has been associated with physical health complications, including migraines, gastrointestinal disorders, and cardiovascular illness, as noted by [

26] and [

28].

Individuals subjected to mobbing frequently experience social isolation and may contend with suicidal ideation or self-injurious behaviour [

18]. These profound psychological repercussions can lead to enduring mental health issues and may also diminish the employee's work capacity or precipitate early retirement [

27]. As a result, these individuals may struggle to re-enter the labour market, imposing a considerable fiscal strain on the state, as they necessitate assistance through social security or other benefits. Although the psychological and physical effects are well-documented, several research depend on self-reported data, which may be subject to personal interpretation or recollection bias. Furthermore, limited research investigates the cumulative impact of mobbing on employees with pre-existing mental health disorders or those belonging to marginalised groups. This indicates a gap in the present studies regarding intersectionality. Recent work has started to investigate the spillover effects on the victim's personal life, including familial stress and social disengagement; nevertheless, these domains remain inadequately explored in empirical research.

2.4. Impact of Mobbing on Organisations

Mobbing in public institutions adversely affects both the individuals involved and the institution's overall efficacy. Mobbing at the organisational level correlates with elevated absenteeism, diminished job satisfaction, decreased productivity, and heightened turnover rates [

24]). Employees who observe or are cognisant of mobbing frequently experience demotivation, which diminishes teamwork, creativity, and overall performance. Furthermore, mobbing can foster a detrimental work atmosphere that undermines organisational innovation and employee involvement. [

23] contend that neglecting mobbing can precipitate a cultural transformation inside an organisation, causing individuals to become alienated and hesitant to share ideas, ultimately leading to diminished growth and efficiency. Organisations affected by mobbing may experience reputational damage both internally and externally, thereby undermining trust with clients, consumers, and the public [

17]. Although there is broad consensus regarding the detrimental effects of mobbing, few research quantifies its financial impact on organisations, such as through employee turnover or legal proceedings. The absence of economic analysis may diminish the motivation for organisational leaders to invest in preventive measures. Moreover, there is less information regarding whether these organisational repercussions vary according to the type of mobbing (e.g., horizontal versus vertical), or based on organisational size or industry. A more sophisticated methodology is necessary to comprehend how mobbing affects various facets of institutional performance.

2.5. Mitigations Strategies for Mobbing in Public Institutions

Effectively addressing mobbing necessitates a comprehensive approach that incorporates both preventive and corrective measures. Preventive approaches emphasise establishing a climate that deters mobbing behaviours and equips staff with the resources to recognise and confront possible bullying events promptly.

A prevalent suggestion is the establishment of explicit anti-mobbing policies. [

29] underscore the necessity for organisations to establish extensive anti-bullying policies and integrate them into their organisational culture. These policies must delineate mobbing behaviours, establish explicit reporting procedures, and specify repercussions for offenders. Training programs for managers and employees are essential for raising awareness of mobbing and providing individuals with the tools to manage workplace conflicts [

28].

Implementing corrective measures, including offering psychological support to victims and executing comprehensive investigations into instances of mobbing, is essential for alleviating the repercussions. Consultant interventions, as advised by [

27], can offer expert help for organisations in effectively managing bullying incidents. Moreover, cultivating a culture of transparency and open communication is crucial, enabling employees to report instances without fear of retribution.

Organisations are advised to implement staff well-being programs designed to enhance work-life balance and mitigate stress, as these measures may decrease the probability of mobbing incidents [

23]. Moreover, leadership significantly influences the organisational climate. Leaders that exemplify positive behaviours and advocate for an inclusive, respectful workplace are less likely to create situations that facilitate mobbing [

17].

Mobbing in public institutions constitutes a grave concern with substantial repercussions for both individuals and organisations. The examined literature emphasises the psychological, physical, and social effects of mobbing, along with its organisational consequences. Despite the increasing research on mobbing in public institutions, there are still gaps in comprehending the problem across various sectors and geographies. Mitigation techniques, including as anti-bullying legislation, training, psychological support, and alterations in organisational culture, are essential for addressing [

30]. Subsequent research should investigate the long-term efficacy of these tactics and analyse the particular situations in which mobbing transpires within public institutions, particularly in Greece, where studies are scarce. Nevertheless, whereas the literature advocates many best practices, the actual execution and enforcement of anti-mobbing rules frequently remain inadequate. [

29] advocate for the incorporation of these policies into organisational culture; yet, few research evaluates their practical usefulness. Moreover, several proposed solutions are reactive—centered on harm mitigation—rather than proactive. Research assessing the long-term efficacy of staff well-being initiatives or leadership training in mitigating mobbing rates is scarce.

The concept of leadership is inadequately theorised in certain works. Although numerous authors acknowledge its significance, there is an absence of explicit direction for which particular leadership styles or behaviors are most effective in safeguarding against mobbing, aside from vague appeals for "positive leadership." Furthermore, the majority of solutions focus on individual assistance or managerial training, while structural factors—such as job instability, bureaucratic burden, or political interference—are hardly considered, despite their potential contribution to the creation of mobbing environments. In the next section a legal framework of Greece regarding mobbing will be analyzed. In Appendix 1 you can find information regarding the legal framework in Greece.

3. Data and Methodology

Mobbing, The research deals with the study of the phenomenon of mobbing in the public administration of the Hellenic Republic. Therefore, as part of the study, the effect of this phenomenon on the employees of the public administration, in combination with their demographic characteristics, will enable the employers to determine rational and effective ways of dealing with it. The range of the subject made it impossible for the Hellenic Republic’s whole public administration population to be examined, which amounted to 482,844 people in 2023 [

31]. This number represents employees in the central public administration, which means the personnel working in the Presidency of the Democracy, the Ministries, the Decentralised Administrations and the Independent Authorities. For this reason, the sample to which the questionnaire was distributed was carefully selected so that it represents all the civil servants that should have filled the questionnaire in, thus ensuring the homogeneity of the sample [

32]. It should be noted that the questionnaire was distributed to 250 employees, from whom 221 responses were received electronically via Google Forms (January-May 2024), thus increasing the response rate to 88.4%.

3.1. Methodology

The method used for the specific research is the quantitative one, due to the fact that the researchers that choose to use it, aim at gaining knowledge through the respondents’ way of thinking. At the same time, they are able to discover innovative ideas, which result from the answers given to specific hypotheses set by the researchers [

33]. Furthermore, the quantitative research is mainly used when the subject under study is complex and therefore it is considered necessary to extract data that will lead to the appropriate knowledge, especial when it is difficult for any other method to be used [

34]. The quantitative method was selected because the research for this work required a high sample size, while simultaneously necessitating the ability to draw inferences about the existence of the phenomena through cross-referencing the utilised variables.

3.2. Data

The research was conducted with the use of the questionnaire, which was the ideal quantitative research tool, taking into consideration the type and goals of the research questions, the resources and the limited timescale for completion of the study [

32]. The questionnaire was structured, following a strictly determined order of the questions, which could not be altered by the respondent. This way, the results comparability and the access to a large survey population were achieved [

35]. The survey was designed to maintain comparability with other studies, while conforming to the research objectives and the limitations of time and money. The questionnaire was organised in a systematic, preset sequence of questions, guaranteeing uniformity across all participants and facilitating the comparison of results with analogous studies in the domain [

35]. The constructs in the survey were based on prior research regarding workplace bullying and mobbing, emphasizing personal, organisational, and psychological aspects that affect bullying behaviours.

3.2.1. Constructs Used in Survey Development

Inquiry on Mobbing: Questions concentrated on the prevalence, nature, and duration of bullying situations encountered by participants. This instrument was developed to assess the magnitude of the phenomenon and correspond with research conducted by [

24] and [

26], which highlighted the psychological and emotional repercussions of mobbing.

Workplace Environment: Enquiries assessing the organisational culture, managerial approaches, and interpersonal dynamics inside the workplace. This framework is informed by prior research conducted by [

23], which identified organisational culture and leadership styles as critical determinants in the occurrence of mobbing.

Personal qualities: This concept examined demographic parameters including age, gender, tenure, education, and organisational position, consistent with the findings of [

20], who posited that individual qualities significantly influence the experience of workplace bullying.

Consequences of Mobbing: This concept seeks to elucidate the individual and organisational ramifications of mobbing, emphasising health (both psychological and physical), absenteeism, productivity, and turnover, as documented by [

27] and [

28].

3.2.2. Survey Methodology and Comparability

The implementation of a standardised questionnaire enabled systematic data collection and assured uniform responses from participants, hence facilitating comparisons with previous studies. The methodology allowed for online completion, facilitating a large and diverse sample, hence enhancing the generalisability of the [

32]. Anonymity was underscored to promote candid responses, reflecting the methodology of [

20] to mitigate social desirability bias.

3.2.3. Data Analysis

The acquired data was analysed with SPSS, utilising frequency tables to quantify responses and elucidate the distribution of answers. The chi-square test was employed to investigate the associations among variables, including the correlation between tenure and previous experience of mobbing, providing statistically significant results [

35].

By following the constructs and methodologies from prior research, this study ensures its findings are comparable to existing literature, while also contributing new insights into the context of mobbing within Greek public institutions. The advantage of the specific tool is that each respondent could fill in the questionnaire in their own time, while more honest responses came through, as the anonymity of the sample was ensured [

20]. It must be further noted that the specific method creates the appropriate conditions for carrying out the analysis easier and extracting trends from the responses [

32]. Please note that the questionnaires were completed online and the results were analysed through SPSS, using frequency tables, so that the percentage of the sample that chose specific answers will be noted. Furthermore, the chi-square test was used, which was adopted in order to determine whether there is a relation between two specific variables each time, when the “significance level” is lower than 0.05 [

35]. This study use the chi-square test to evaluate the association between two nominal variables. It aids in ascertaining the existence of a statistically significant correlation/effect among these variables. The article states that the chi-square test was utilised to examine the relationship between two variables. This may entail examining the correlation between tenure and the experience of mobbing or assessing the relationship between education level and the frequency of mobbing.

3.2.4. Statistical Method Used

The chi-square test is suitable for this study as it is intended for examining correlations between categorical/nominal variables. This may entail investigating whether specific demographic parameters (e.g., gender, educational attainment, job position) correlate with the probability or incidence of encountering mobbing. The study may aim to address enquiries such as:

The chi-square test offers a straightforward and effective method for assessing significant connections between categorical variables, aiding researchers in understanding the dynamics of mobbing in Greek public institutions.

To finalise the analysis, the chi-square test statistic (χ²) and the corresponding p-value (significance level) must be documented. This is often represented as follows in a results section:

Chi-square value (χ²): This signifies the magnitude of the relationship between the variables.

Degrees of freedom (df): This contextualises the chi-square value regarding its anticipated distribution.

P-value: This metric is utilised to evaluate the statistical significance of the observed relationship, often when p < 0.05.

Consequently, the test statistics (chi-square value, degrees of freedom, and p-value) are essential for interpreting the findings of the chi-square test and assessing the validity of the hypotheses regarding the correlations between variables.

3.3. Research Sample

The range of the subject made it impossible for the Hellenic Republic’s whole public administration population to be examined, which amounted to 482,844 people in 2023 [

31]. This number represents employees in the central public administration, which means the personnel working in the Presidency of the Democracy, the Ministries, the Decentralised Administrations and the Independent Authorities. For this reason, the sample to which the questionnaire was distributed was carefully selected so that it represents all the civil servants that should have filled the questionnaire in, thus ensuring the homogeneity of the sample [

32]. It should be noted that the questionnaire was distributed to 250 employees, from whom 221 responses were received electronically via Google Forms (January-May 2024), thus increasing the response rate to 88.4%.

4. Results and Discussion

The Chi-square (x²) test’s results highlighted points of interest that are worth studying. According to Chi-square (x²) test, it was indicated as you can see in the following table that years of service have a statistically significant effect on whether employees experience workplace bullying (mobbing) (x² = 37.205, df = 20, p = 0.011), In addition the Chi-square (χ²) test indicated that we cannot determine whether years of service affect the frequency with which respondents have experienced workplace bullying (mobbing) during the past 12 months (x² = 37.655, df = 25, p = 0.05). Through the specific method, it was prominent that the employee’s job position has a statistically significant effect on whether they experience workplace bullying (mobbing) (x² = 12.725, df = 4, p = 0.013), while age also appears to have an important influence on being a mobbing victim (x² = 19.616, df = 4, p = 0.001. It was also pointed out that the educational level affects the conditions under which an employee experiences mobbing (χ² = 10.471, df = 4, p = 0.015). Interestingly enough, the research results showed that the gender of an employee is a variable that is not playing major role on whether mobbing takes place (χ² = 6.225, df = 5, p = 0.285).

Table 1.

Chi-square (x²) Test’s Results.

Table 1.

Chi-square (x²) Test’s Results.

| Variable |

Chi-square (χ²) |

Degrees of Freedom (df) |

p-value |

Statistical Significance |

Interpretation |

| Years of Service (bullying occurrence) |

37.205 |

20 |

0.011 |

Significant |

Years of service significantly affects whether bullying occurs. |

| Years of Service (bullying frequency) |

37.655 |

25 |

0.050 |

Not Significant / Marginal |

Unclear if years of service affects bullying frequency in past 12 months. |

| Job Position |

12.725 |

4 |

0.013 |

Significant |

Job position significantly affects bullying experience. |

| Age |

19.616 |

4 |

0.001 |

Significant |

Age has a strong influence on being a mobbing victim. |

| Educational Level |

10.471 |

4 |

0.015 |

Significant |

Education level significantly affects mobbing conditions. |

| Gender |

6.225 |

5 |

0.285 |

Not Significant |

Gender does not significantly influence mobbing occurrence. |

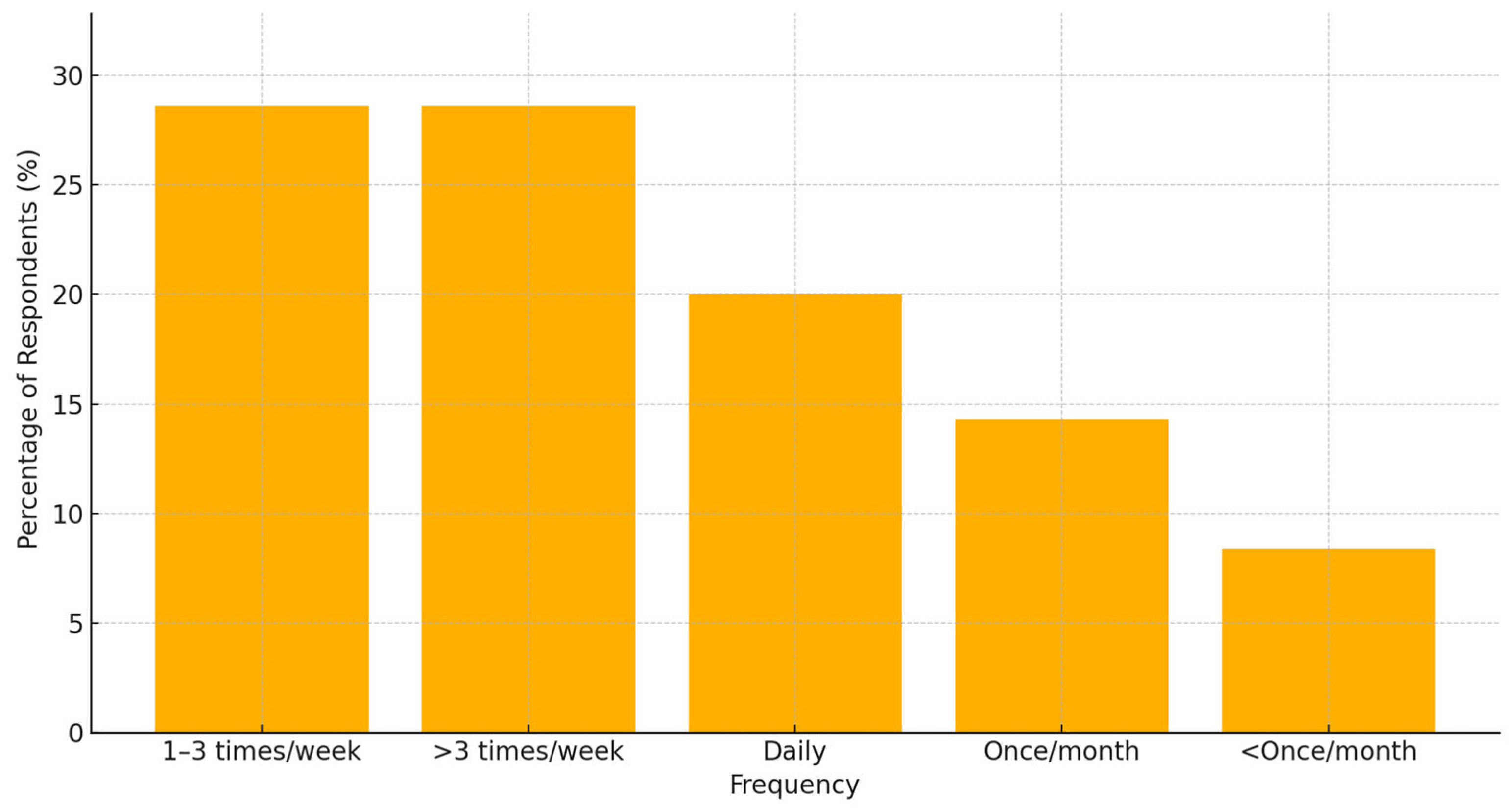

As you can see in the following chart, 53.8% of the sample, felt that they were receiving mobbing in their work environment, with 28.6% justified the frequency of the phenomenon to 1-3 times per week and another 28.6% over 3 times per week. A further 20% of the respondents felt that they were bullied daily, 14.3% once per month and lastly 8.4% less often than once per month. Consequently, the results of the current research follow Leymann’s definition [

7], which mentions that for an action to be considered mobbing, the employee must feel harassed at least once per week for a period of six months and above.

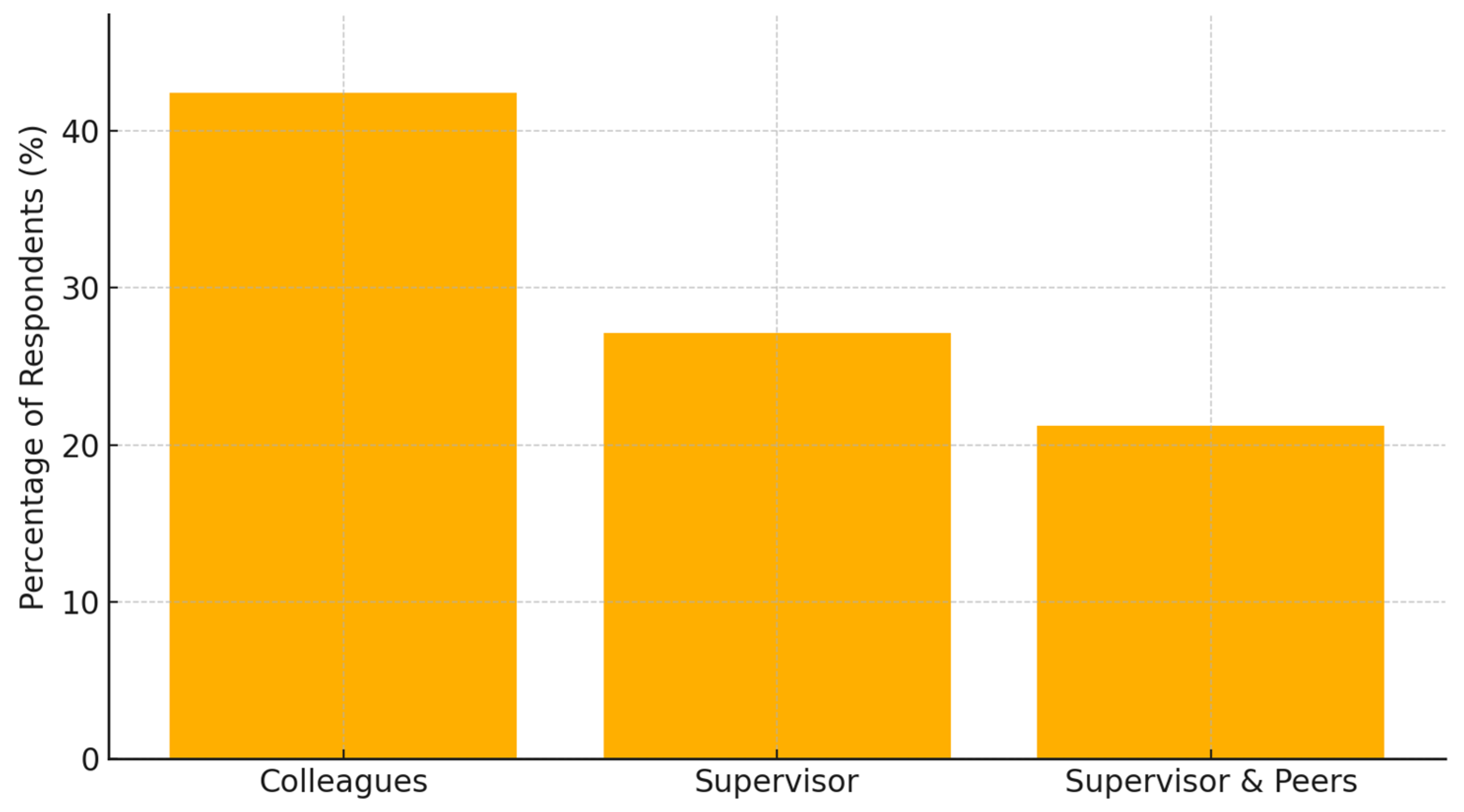

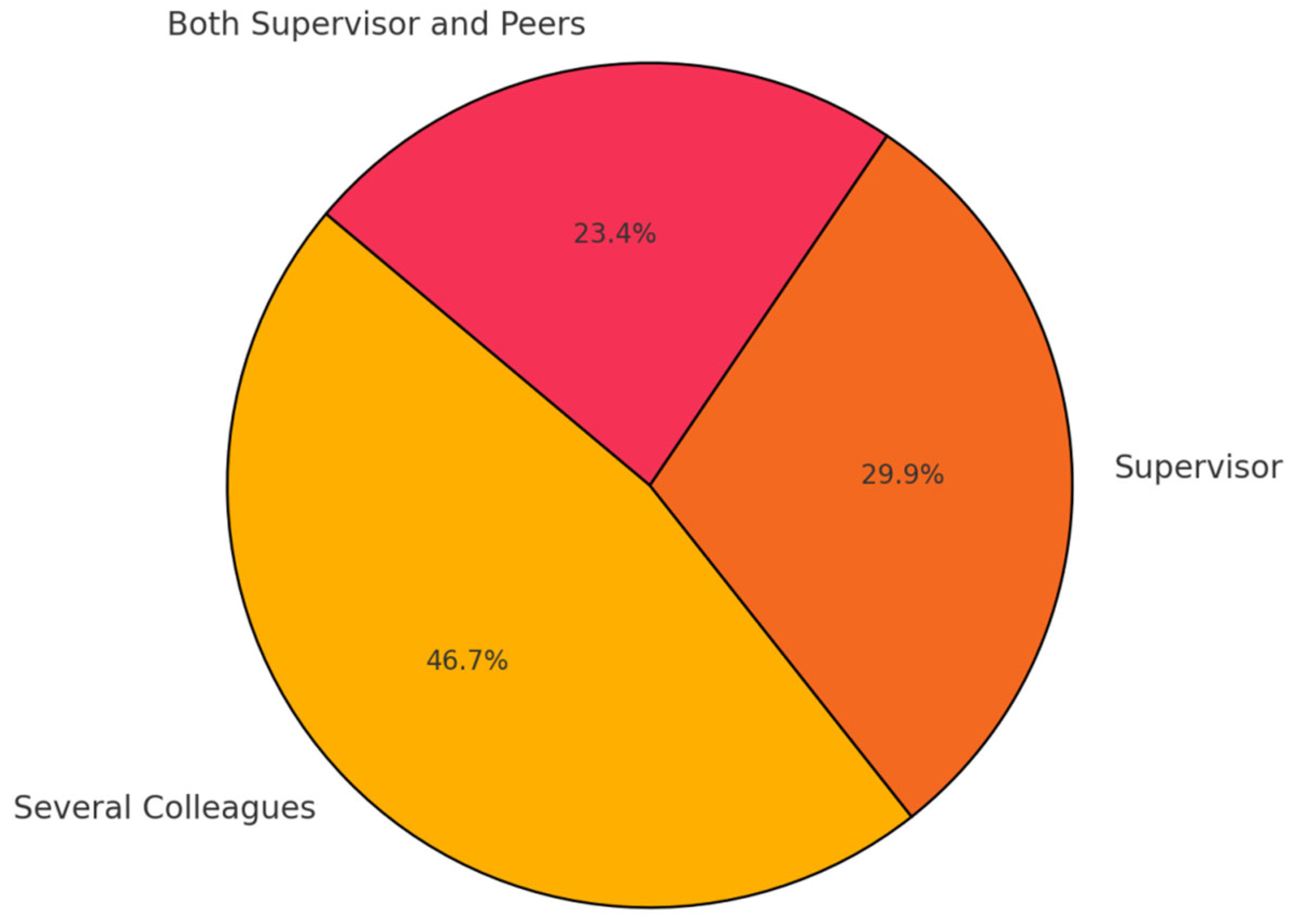

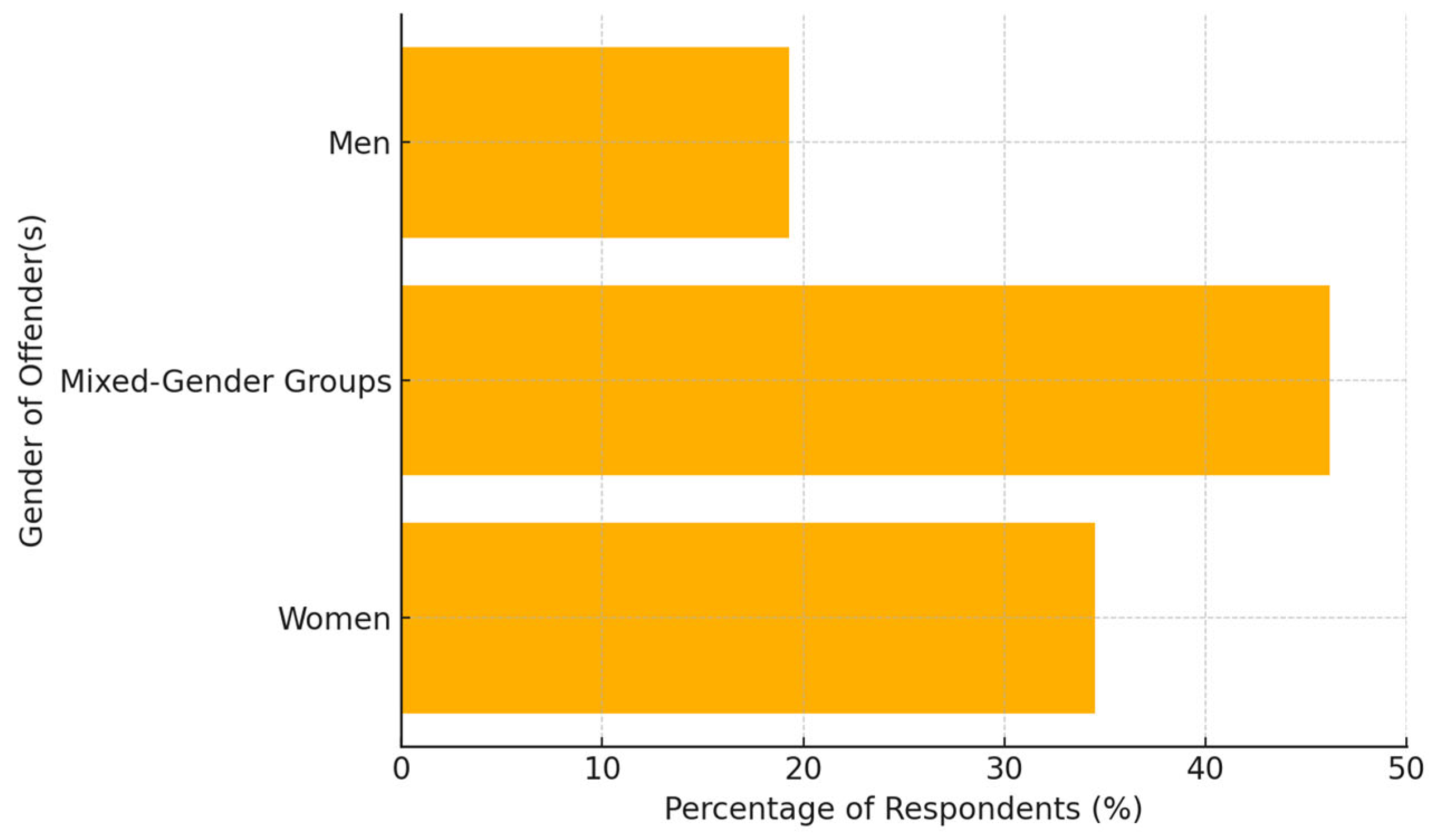

An interesting fact to note is that through the sample it became clear the highest percentages of mobbing were recorded in the cases where the employee was experiencing harassment by a number of colleagues. This corresponds to 42.4% of the sample. Mobbing from the Supervisor counted for 27.1% of the respondents and 21.2% of the sample answered that they received mobbing from the Supervisor and peers of the victim. Concerning the gender of the perpetrators, 34.5% were women, 46.2% were both men and women and 19.3% men (see the following diagrams).

Figure 1.

Frequency of Workplace Mobbing.

Figure 1.

Frequency of Workplace Mobbing.

Figure 2.

Source of Workplace Mobbing.

Figure 2.

Source of Workplace Mobbing.

Figure 3.

Gender of Mobbing Perpetrators.

Figure 3.

Gender of Mobbing Perpetrators.

This result indicates the social aspect of the phenomenon, portraying the image of the women as Supervisors to be stricter in their effort to impose themselves in the workplace, to the extent that they cause mobbing. Notably, the findings suggest that regarding women as colleagues of equal grade with the victim or even inferior to it, since again there is a tendency to gain more power in the work environment through discussing or commenting on the individual.

Further to the above information, as part of the more general information, there were some questions, which indicated the type of mobbing experienced by the employees. The reader was also informed for the fact that these particular statements were filled in by the entire sample, adding to the current research, the insight that some respondents were experiencing mobbing without realising it.

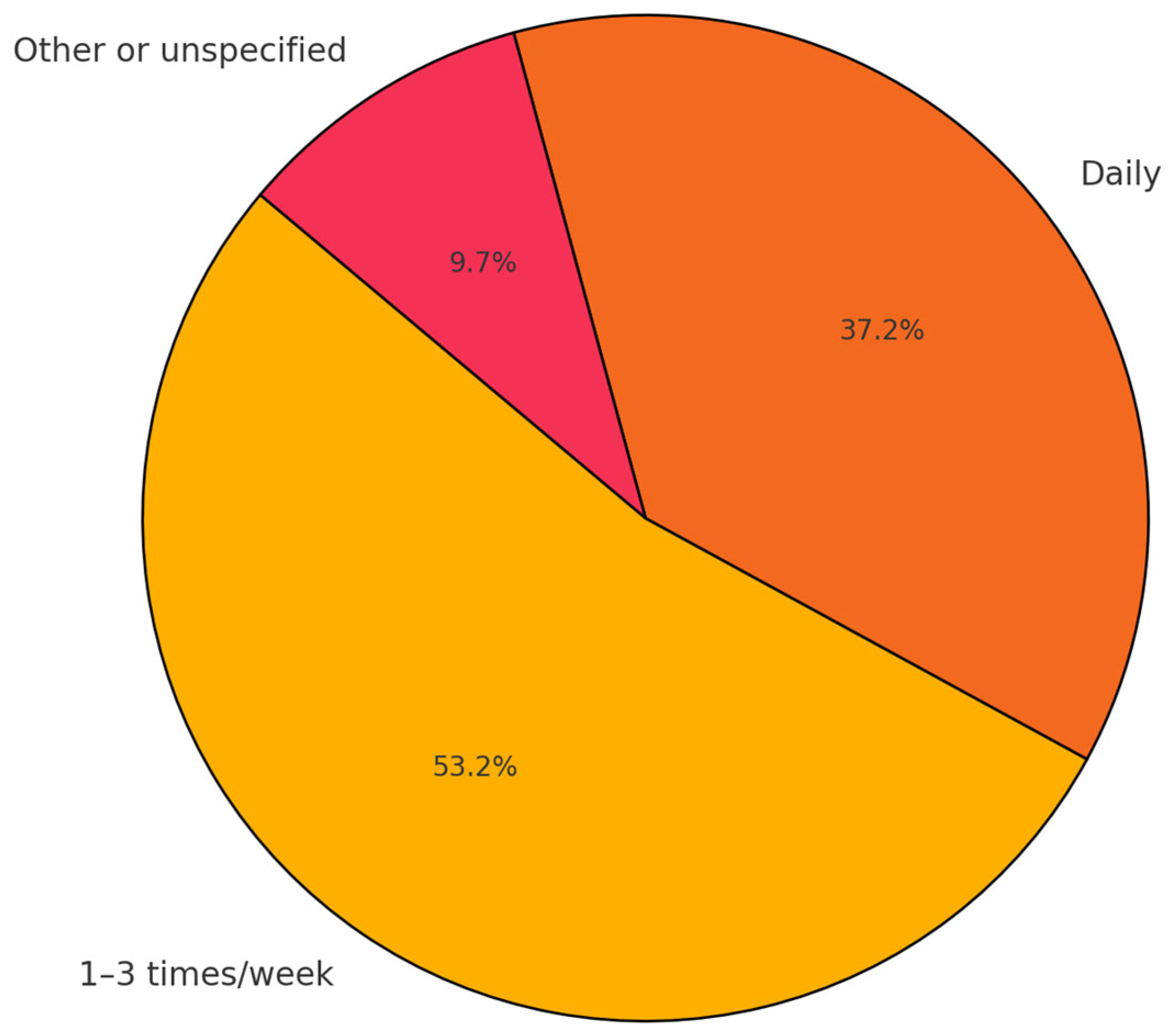

The study's findings indicate that a substantial percentage of the sample (53.8%) reports experiencing mobbing in their workplace, with 28.6% stating that it occurs 1-3 times per week and 20% reporting daily occurrences (see the following chart). This outcome aligns with [

7] research, which characterises mobbing as unpleasant behavior occurring at least weekly over a six-month duration. Consequently, the findings of the present study validate Leymann's characterisation, reinforcing the perspective that mobbing is a persistent, recurrent problem rather than a singular occurrence.

Figure 4.

Frequency of Mobbing Among Affected Respondents.

Figure 4.

Frequency of Mobbing Among Affected Respondents.

The frequency distribution (e.g., 28.6% experiencing mobbing 1-3 times weekly and 20% daily) corresponds with earlier research indicating that workplace bullying is frequently a recurrent, enduring issue. [

15] discovered that mobbing generally transpires weekly, whereas [

2] observed analogous trends, with bullying incidents regularly arising in public administration environments. The discovery that 42.4% of respondents indicated harassment by several colleagues and 27.1% by supervisors contributes to the current literature on the diverse origins of workplace bullying. Research by [

20] and [

2] corroborates that mobbing frequently entails several aggressors, encompassing both colleagues and superiors, aligning with the documented distribution of harassers in our study. That 21.2% of respondents indicated experiencing bullying from both bosses and peers underscores the intricacy of the mobbing phenomena (see the following chart). Prior research has frequently indicated that bullying is more prevalent among peers at equivalent hierarchical levels or between subordinates and their superiors. [

36] discovered that hierarchical bullying by supervisors is widespread, however peer-to-peer bullying can be equally detrimental. This study's findings enhance the existing research by offering a nuanced perspective on the dynamics of mobbing across various levels of organisational structure.

Figure 5.

Source of Mobbing Reported by Respondents.

Figure 5.

Source of Mobbing Reported by Respondents.

The discovery that 34.5% of offenders were women and 19.3% were men corresponds with [

37] research, indicating that women can serve as both perpetrators and victims of mobbing, especially in intensely competitive workplaces. The study's observation that women supervisors are stricter and contribute to mobbing aligns with the findings of [

23], who indicated that women in leadership roles may display behaviors intended to assert power or authority over subordinates, potentially resulting in bullying. The gender distribution as you can see the following chart, (34.5% women, 46.2% mixed-gender groups, and 19.3% men) corroborates the assertion that mobbing may be a social phenomenon influenced by gender dynamics. [

29] emphasised that mobbing is not limited to same-gender encounters but frequently encompasses mixed-gender dynamics, illustrating the intricacies of workplace relationships and power hierarchies. [

38] discovered that bullying perpetrators may be of either gender; nevertheless, power dynamics, rather than gender alone, influence the behavior.

Figure 6.

Gender Distribution of Mobbing Offenders.

Figure 6.

Gender Distribution of Mobbing Offenders.

The study revealed that certain respondents did not first identify the mobbing they were enduring. This discovery is significant as it underscores an underreported facet of workplace bullying. Numerous employees may fail to recognise specific behaviors as bullying owing to normalisation, unawareness, or apprehension of retaliation. [

29] discovered that victims of workplace bullying frequently do not identify the behavior as mobbing until it intensifies or results in significant psychological consequences. This conclusion aligns with [

20], who highlighted that numerous victims, particularly those newly employed or unacquainted with bullying, may fail to recognise or report mobbing until it results in enduring repercussions. The findings of the present study corroborate existing literature on workplace bullying, affirming Leymann’s [

7] definition of mobbing and emphasising analogous trends concerning the prevalence of bullying, its aggressors, and its social dynamics. Nonetheless, the study offers novel findings, especially concerning the influence of female supervisors on mobbing behaviors and the inadequate acknowledgement of bullying by certain employees. This enhances the comprehensive understanding of mobbing in public institutions and provides a distinctive viewpoint within the context of the Greek public sector.

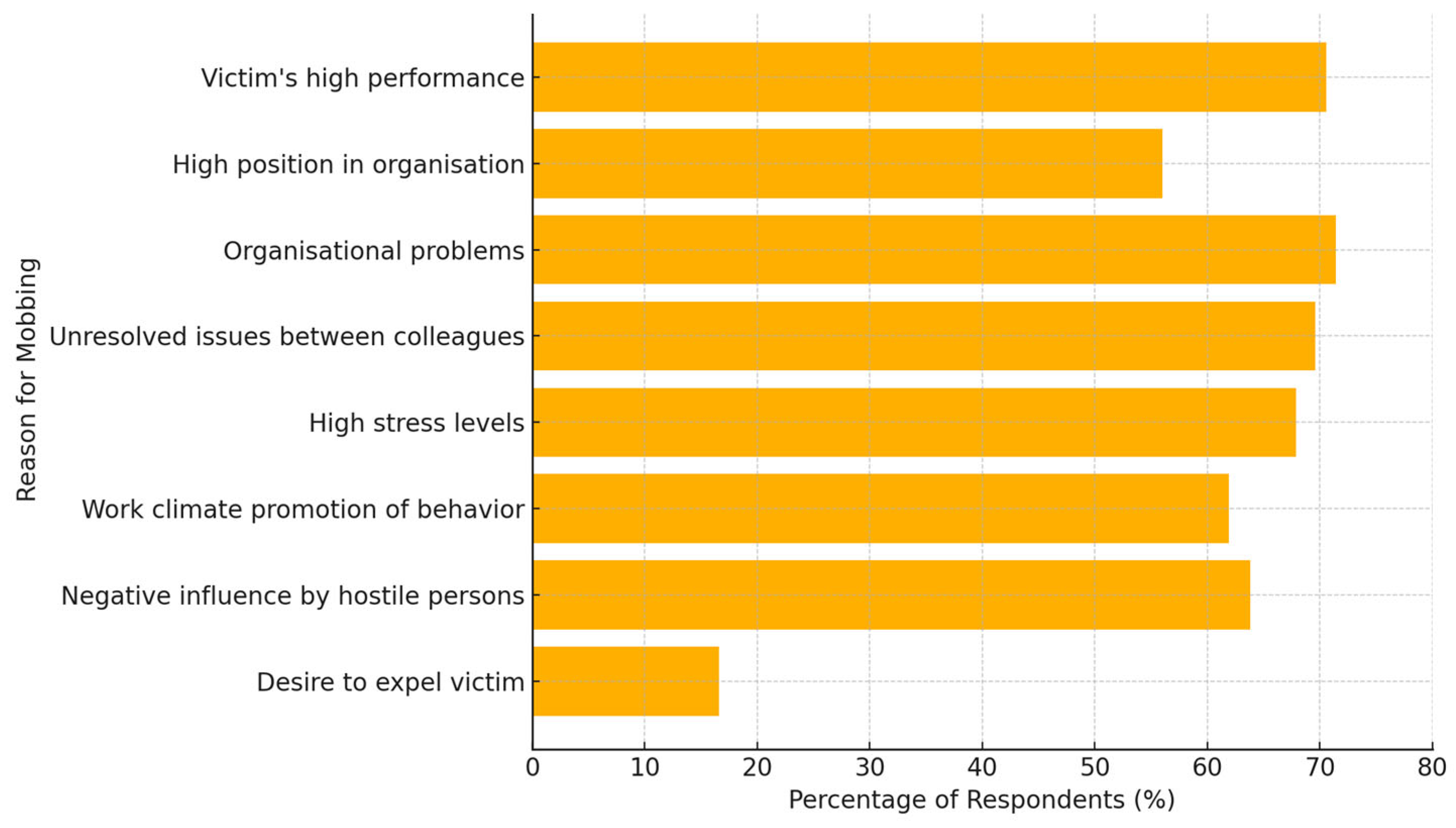

The data in the following chart indicate, only 16.6% of the respondents believe that the abuser’s purpose is the desire to expel the victim from the Service, 63.8% of the sample have the opinion that the victim’s colleagues can be negatively influenced by hostile persons, 61.9% of the respondents agreed that the abuser’s behavior was promoted by the work climate, 67.9% of the mobbing victims indicated that the high stress levels are the main cause for the existence of the phenomenon, while 69.6% of the population participating in the survey answered positively that the unresolved issues between colleagues can cause mobbing. Further to the above, 71.4% of the participants in the survey believe that the organisational problem can be the main reason for the appearance of mobbing, 56% of the sample stated that the received mobbing was due to the high position they hold in the organisation and finally 70.6% of the respondents agreed that the victim’s high performance could cause mobbing.

Figure 7.

Perceived Reasons Behind Mobbing Experiences.

Figure 7.

Perceived Reasons Behind Mobbing Experiences.

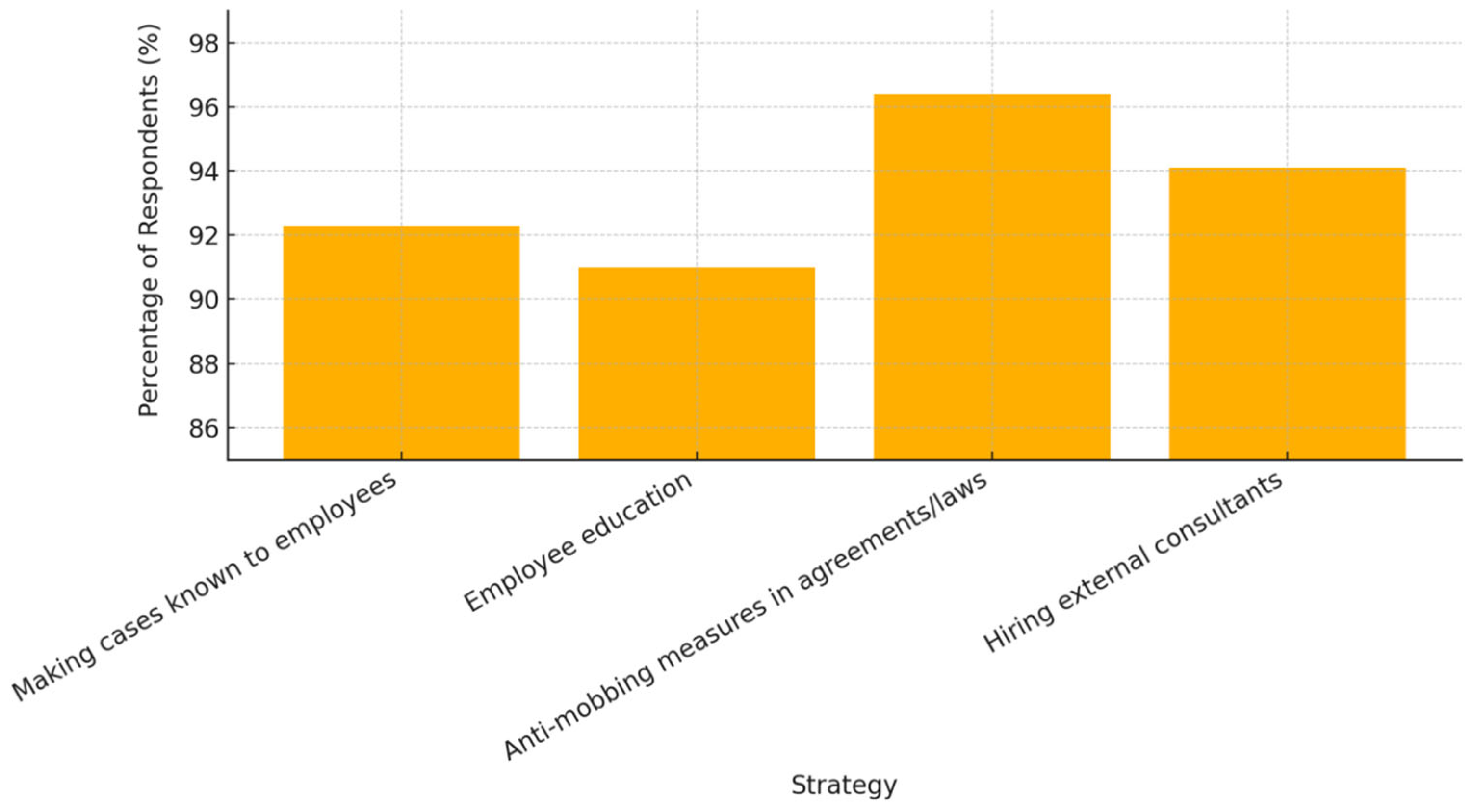

The outcomes of the survey regarding the strategies to confront mobbing are consistent with findings from previous research. The result that 92.3% of participants believe making cases known to employees is an effective measure aligns [

15], who emphasized the importance of transparency and open communication in preventing and mitigating mobbing. Similarly, the 91% of respondents who support employee education reflect [

39] argument that awareness and targeted training are essential in building a respectful workplace culture. The high percentage (96.4%) endorsing the integration of anti-mobbing measures into agreements and legislation corroborates the findings of [

40], who advocated for formal policies and legal frameworks as foundational elements in eradicating workplace bullying. Furthermore, the 94.1% agreement on hiring external consultants is supported by [

41], who noted that expert involvement can help manage complex interpersonal conflicts and ensure impartial assessments. Collectively, these findings confirm and extend the literature, emphasizing a holistic, multi-tiered approach to effectively addressing mobbing in organizational contexts.

Figure 8.

Support for Strategies to Confront Mobbing.

Figure 8.

Support for Strategies to Confront Mobbing.

5. Conclusion

Workplace bullying, sometimes known as "mobbing," is a detrimental occurrence impacting both public and commercial sectors. It encompasses antagonistic conduct towards staff members, eroding their dignity and sometimes resulting in resignation or absenteeism. Mobbing inflicts harm on individual, organisational, and societal levels, impacting employees' mental and physical well-being, self-esteem, and productivity. For organisations, it results in diminished earnings, decreased service quality, heightened absenteeism, and more resignations. Socially, it imposes increased unemployment and medical costs on the state.

This study provides insights into mobbing inside Greece's public administration, enhancing both theoretical and practical understanding. It contests the current literature by demonstrating that mobbing transpires irrespective of gender, opposing earlier conclusions that indicate women are more frequently victims. The data indicates that victims are typically aged between 31 and 50 years, possess up to 10 years of service, and endure harassment from both colleagues and bosses. The research indicates that mobbing is common among individuals with higher education and those in senior roles. The research indicates no association between gender, implying an absence of prejudice. The causes of mobbing encompass organisational problems, elevated performance expectations, unsolved conflicts, and workplace stressors. The report recommends amending legislation, employing seasoned consultants, enhancing awareness, and providing training for managers and staff members to address mobbing.

The current study enriched the existing literature with further knowledge, while it would be possible for more observations and conclusions to be drawn if it covered a wider range of the cognitive object, such as the consequences of the phenomenon and the abuser’s characteristics. It should also be given more time for completion and cover larger population for completing the questionnaires. For this purpose, it is of high importance the participation of the managers working in the administration of the organisation, as in this case the opportunity to study whether they experience mobbing from their inferiors, would be available. This is a subject that has not been analysed extensively in the literature.

It is further noted that for the time being the knowledge is limited to more general causes of the phenomenon. The requirement for the future is the development of more detailed questionnaires concerning the reasons for which the mobbing exists, as well as carrying out qualitative research through detailed interviews with both the victims and the abusers, as well as managers that are called to handle such complaints. In this way, all the terms will be simplified and deeper knowledge on the matter will be made possible, while tangible organisational issues, that cause concern, coming to the light, as well as the organisational climate that promotes the mobbing. Related to this suggestion is also the study of the leadership type implemented in the organisations that mobbing is existent, so that through a hybrid method of both questionnaires and interviews, it will be made possible to study whether the management techniques used are responsible and to what extent. This, will influence, in turn, the organisational culture, but also the appearance of the mobbing. A contribution of major importance for the promotion of the subject’s better understanding would be the systematic and continual annual monitoring of the implementation of the Law 4808/2021. An example is the monitoring of the equivalent article of the legislation, which refers to the employee removing themselves from the workplace when they feel that mobbing working conditions are developed, without reducing their wage. Therefore, it would be useful to record the conditions under which the specific Law was implemented and the consequences of these actions. Although the studies recognise the phenomenon of mobbing and try to create a rounder understanding on this matter, it should be primarily understood by decision-makers in the public administration that the human resource management in the public service differs by far from the private sector. Therefore, public servants ought to be treated differently, in order for the desired result of the phenomenon elimination to be obtained, taking into consideration that the public servants’ motives are different.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and C.P.; methodology, S.K. and S.A..; software, S.K.; validation, S.K., C.P. and S.A.; formal analysis, S.K. and C.P..; investigation, S.K. and C.P..; resources, S.K and C.P.; data curation, S.K. and C.P..; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.K., C.P. and S.A.; visualization, S.K. and C.P..; supervision, C.P. and S.A..; project administration, S.K., C.P. and S.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Neapolis University Pafos.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be requested from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PTSD |

Household Budget Survey Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

Appendix A

Legal Framework - Greece

The citizens’ fundamental rights are recorded in the Constitution of the Hellenic Republic of 2008, with Article 2 providing that the State must protect the honour and reputation of every citizen, Article 7 stating that the exercise of physical or psychological violence and the cause of any harm, even to the dignity of a citizen, are offences punishable by Law, while Article 22 combines all the above information and completes the perception that every citizen should have when facing mobbing, seeing that every citizen has the right to work (Hellenic Parliament, 2008).

Another piece of legislation which is very important for the protection of the employees from mobbing is the Law 4808/2021 for the Protection of Work. This Law that was voted by the Hellenic Parliament in 2021 primarily sanctioned “International Labour Organisation Convention 190” [

42], which provides protection to private and public sector employees in relation to incidents of harassment. The purpose of the second part of the Law is to combat violence and harassment by expressly providing for the obligations the employers have towards the employees, as well as the policies that the organisations ought to adopt in terms of how complaints, incidents and abusers are handled. This specific Law also protects the employees from any employer retaliation against victims who filed complaints [

42]. The means that can be used for the protection of the employees is to file a lawsuit against the perpetrator, to appeal to the Labour Inspection Body, which is an independent authority with the aim to control incidents of workplace intimidation, while the Greek Ombudsman can also examine such complaints. However, the Regulation that is pioneering is the right granted to the employee by the Law, to leave their workplace in the case they feel that their life or safety are endangered, without the employer having the right to deduct salary or impose any sanction [

42]. Moreover, the European Union (EU) legislative framework is protective of the Member States employees. In particular, according to Article 2 of the Treaty on the European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, its institution is governed by fundamental values, such as dignity, democracy, freedom, justice and respect for the rights of every citizen, while gender equality is additionally promoted [

43].

Article 1 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union also protects the rights of each person, such as its dignity, while the Article 31 protects each citizen’s right to work provided that in their work environment enjoys security and maintains their health and reputation [

43]. It is further noted that the International Labour Organisation drew up a Convention in 2019, which is the first treaty promotes at an international level the demand of every working individual to be employed in an environment without harassment and the use of any kind of violenc). Although the legal framework seems extensive in theory, the practical enforcement mechanisms and societal perceptions of workplace bullying in Greece are less often examined. Empirical data on whether victims of mobbing in Greece utilise legal protections is minimal, and it is unclear if fear of stigma or retaliation hinders reporting. Furthermore, Greece's comparative deficiency in academic literature about mobbing, in relation to other EU countries, indicates a significant study void. Future research may evaluate both workers' legal awareness and institutional reaction to grievances.

References

- Einarsen, S. V.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C. L. Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Developments in theory, research, and practice, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020.

- Giorgi, G.; Arcangeli, G.; Mucci, N.; Cupelli, V. Economic stress in the workplace: The impact of fear of the crisis on mental health. Work 2016, 53, 815–822.

- Salin, D.; Hoel, H. Organisational risk factors of workplace bullying. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace, 3rd ed.; Einarsen, S. V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C. L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 305–332.

- Notelaers, G.; De Witte, H.; Einarsen, S. Measuring exposure to bullying at work: The validity and advantages of the latent class cluster approach. Work Stress 2018, 32, 244–262.

- Rybak, C. J. The concept of mobbing: An overview and implications for counseling. J. Couns. Dev. 2008, 86, 131–138.

- Boge, C.; Larsson, A. Understanding pupil violence: Bullying theory as technoscience in Sweden and Norway. Nord. J. Educ. Hist. 2018, 5, 131–149.

- Leymann, H. The content and development of mobbing at work. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 165–184.

- Einarsen, S.; Skogstad, A. Prevalence and risk groups of bullying and harassment at work. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 185–202.

- Zapf, D. Organisational, work group related and personal causes of mobbing/bullying at work. Int. J. Manpow. 1999, 20, 70–85.

- Proskauer Rose LLP. Bullying, harassment and stress in the workplace: A European perspective. 2012.

- European Parliament. Bullying at work. Dir.-Gen. Res. 2001.

- Stefanović, G. Role of trade unions in the prevention of mobbing or bullying. J. Labour Soc. Aff. East. Eur. 2012, 3, 401–414.

- Quine, L. Workplace bullying in nurses. J. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 73–84.

- Nielsen, B. N.; Einarsen, S. V. What we know, what we do not know, and what we should and could have known about workplace bullying. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 42, 71–83.

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C. L. (Eds.). Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Developments in theory, research, and practice, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 3–53.

- International Labour Organization. (2019). C190 – Violence and Harassment Convention, 2019 (No. 190).

- Skurdenienė, N.; Prakapienė, D. Mobbing in the public sector: The case of the Ministry of National Defence of Lithuania and its institutions. Public Policy Adm. 2021, 20, 34–44.

- Pytel-Kopczyńska, M.; Oleksiak, P. Mobbing at the workplace and the sustainable human resource management in an organisation. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. 2022, 163, 445–455.

- Arnejčič, B. Mobbing in company: Levels and typology. Organizacija 2016, 49, 38–47.

- Cowie, H.; Naylor, P.; Rivers, I.; Smith, P. K.; Pereira, B. O. Measuring workplace bullying. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2002, 7, 33–51.

- Vartia, S. Organisational, work environment and personal factors in bullying at work. Work Stress 2001, 15, 215–236.

- Papademetriou, C.; Masouras, A. Social networking sites: The new era of effective online marketing and advertising. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Soliman, K. S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 443–448.

- Fox, S.; Stallworth, L. E. Building a framework for two internal organizational approaches to resolving and preventing workplace bullying: Alternative dispute resolution and training. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2009, 61, 220–241.

- Georgakopoulos, A.; Kelly, M. P.; Coffrey, M.; Karanika-Murray, M. Tackling workplace bullying: A scholarship of engagement study of workplace wellness as a system. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2017, 10, 450–469.

- Inuwa, M. Job satisfaction and employee performance: An empirical approach. Millennium Univ. J. 2016, 1, 90–103.

- Golab, S.; Bedzik, B.; Sieklecka, Z. The phenomenon of mobbing at work – Initial report from the research. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. 2023, 168, 133–142.

- Gembalska-Kwiecień, A. Mobbing prevention as one of the challenges of a modern organization. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2020, 144, 71–85.

- Donar, G. B.; Yesilaydin, G. The evaluation of mobbing cases in the healthcare sector based on Supreme Court case law in Turkey. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 2888–[28]96.

- León-Pérez, J. M.; Escartín, J.; Giorgi, G. The presence of workplace bullying and harassment worldwide. In Concepts, Approaches and Methods, 1st ed.; D’Cruz, P., Noronha, E., Notelaers, G., Rayner, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 49–78.

- Papademetriou, C.; Anastasiadou, S.; Ragazou, K.; Garefalakis, A.; Papalexandris, A. ESG and total quality management in human resources. IGI Global 2024.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Government at a Glance 2023: Greece. OECD 2023.

- Liargovas, P.; Dermatis, Z.; Komninos, D. Μεθοδολογία της έρευνας και συγγραφή επιστημονικών εργασιών [Research methodology and scientific writing]. Tziola: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2018.

- Curry, L. A.; Nembhard, I. M.; Bradley, E. H. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation 2009, 119, 1442–1452.

- Haq, M. A comparative analysis of qualitative and quantitative research methods and a justification for adopting mixed methods in social research. Annu. PhD Conf. Univ. Bradford Sch. Manag. 2014.

- Zafiropoulos, K. How to write a scientific paper? Scientific research and paper writing, 2nd ed.; Kritiki Publications: Athens, Greece, 2015.

- Hauge LJ, Skogstad A, Einarsen S. The relative impact of workplace bullying as a social stressor at work. Scand J Psychol. 2010 Oct;51(5):426-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosander, M.; Salin, D. A hostile work climate and workplace bullying: Reciprocal effects and gender differences. Employee Relat. 2023, 45, 46–61.

- Branch, S.; Ramsay, S.; Barker, M. Workplace bullying, mobbing and general harassment: A review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 280–299.

- Salin, D. The prevention of workplace bullying as a question of human resource management: Measures adopted and underlying organizational factors. Scand. J. Manag. 2008, 24, 221–231.

- Hoel, H.; Giga, S. I. Destructive interpersonal conflict in the workplace: The effectiveness of management interventions. Univ. Manchester Inst. Sci. Technol. 2006.

- Zapf, D.; Einarsen, S. Mobbing at work: Escalated conflicts in organizations. In Counterproductive Work Behavior: Investigations of Actors and Targets; Fox, S., Spector, P. E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 237–270.

- TaxHeaven. Law 4808/2021 codified with Law 5078/2023. TaxHeaven 2021.

- European Union. Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. Off. J. Eur. Communities 2000.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).