Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

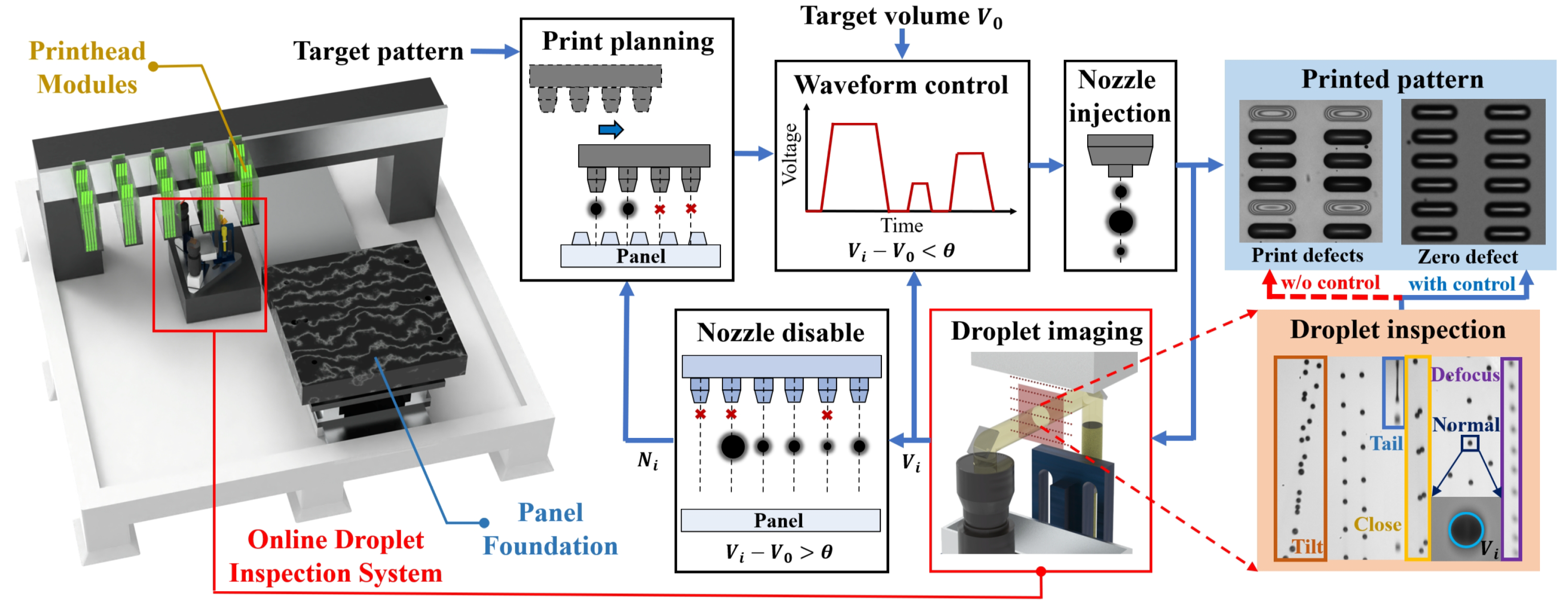

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Degradation Methods for Synthetic Image Generation

2.2. Metaheuristic Algorithms for Optimization

3. Methodology

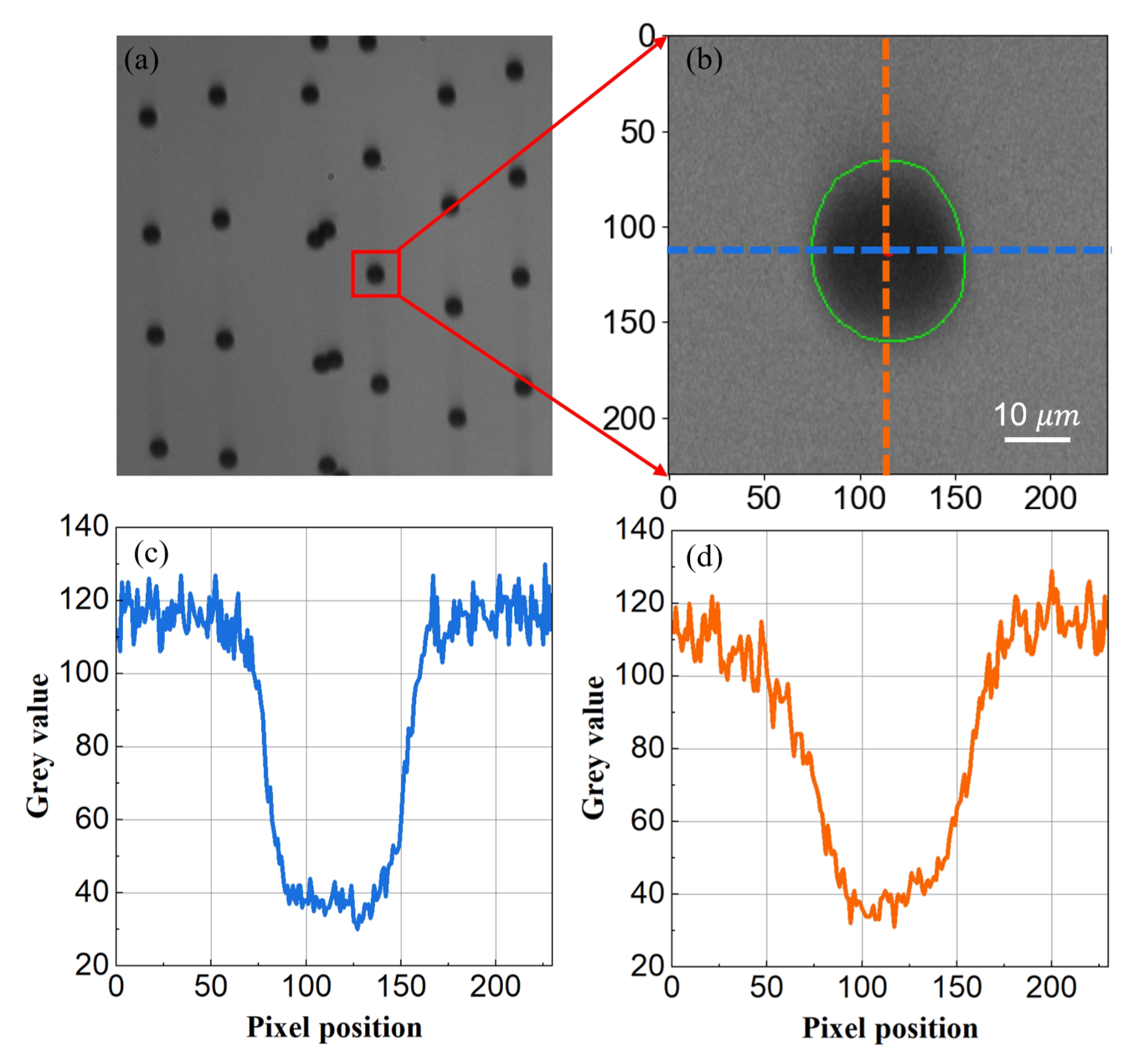

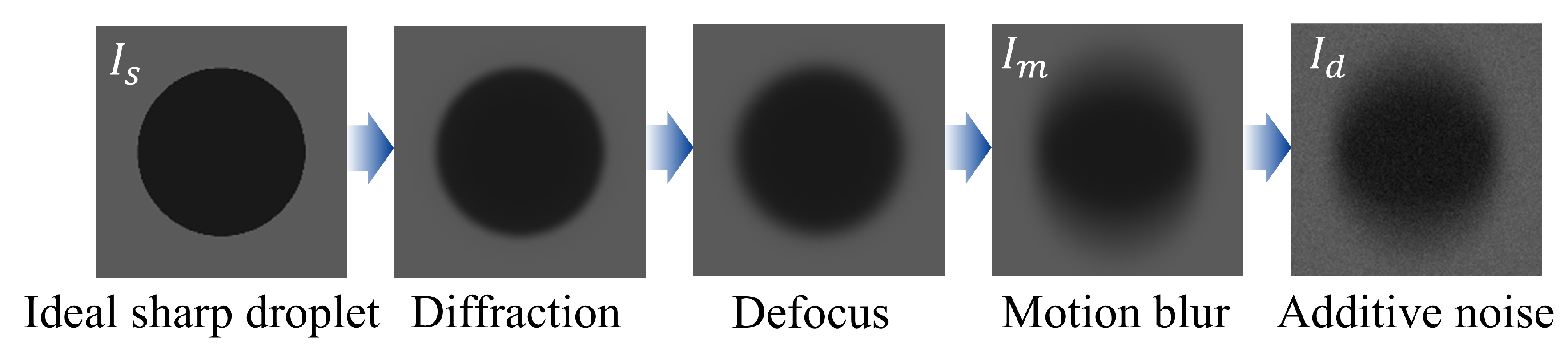

3.1. Physically-Informed DGMN Model of Droplet Image

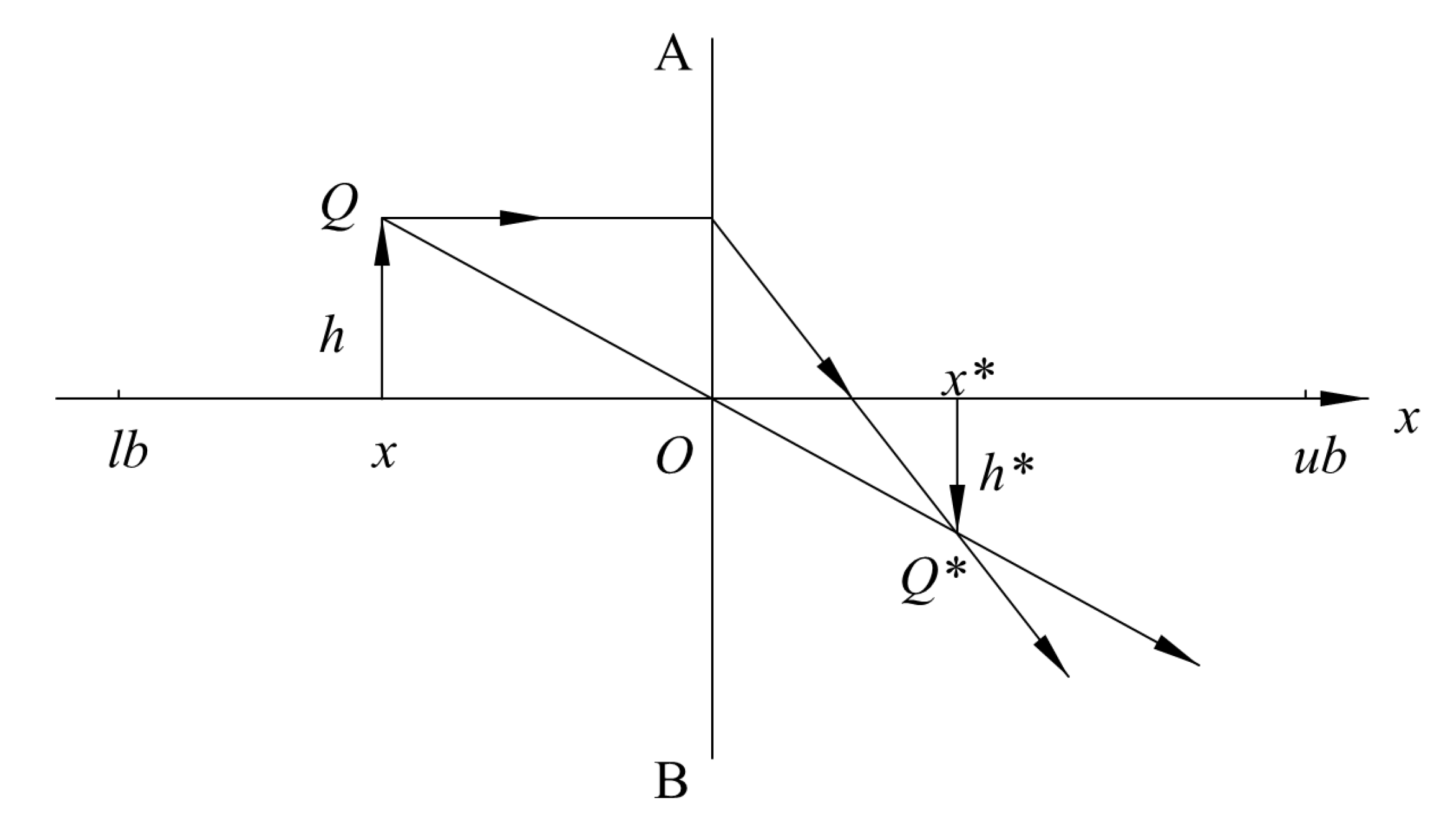

3.2. SABO Algorithm

3.3. The Proposed MISABO Algorithm

3.3.1. Sobol Sequence Initialization

3.3.2. Lens Opposition Based Learning

3.3.3. DLH Search Strategy

3.3.4. MISABO Algorithm Flow

| Algorithm 1:MISABO Algorithm |

|

4. Experiments and Results

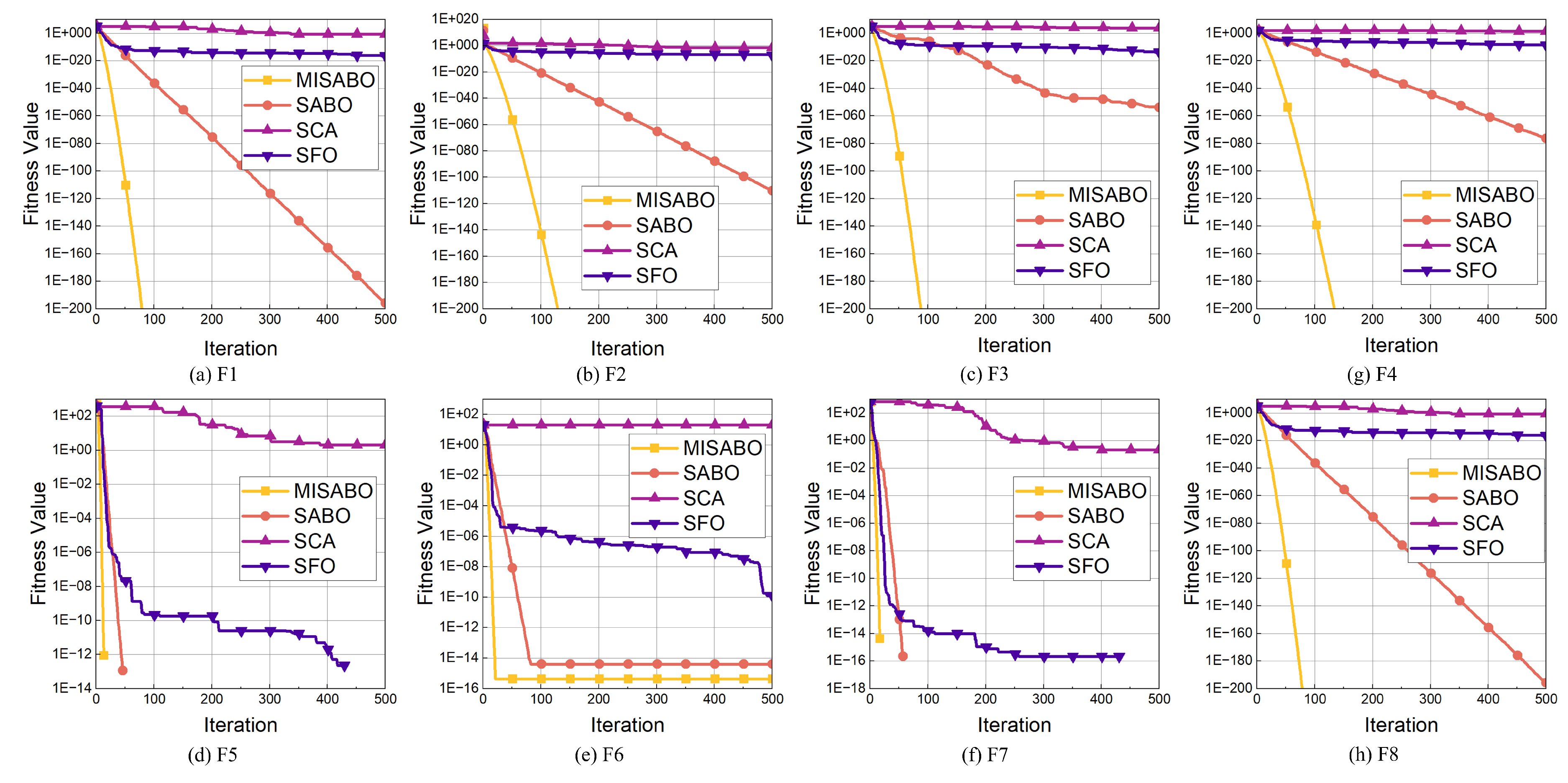

4.1. Performance of MISABO on Benchmark Functions

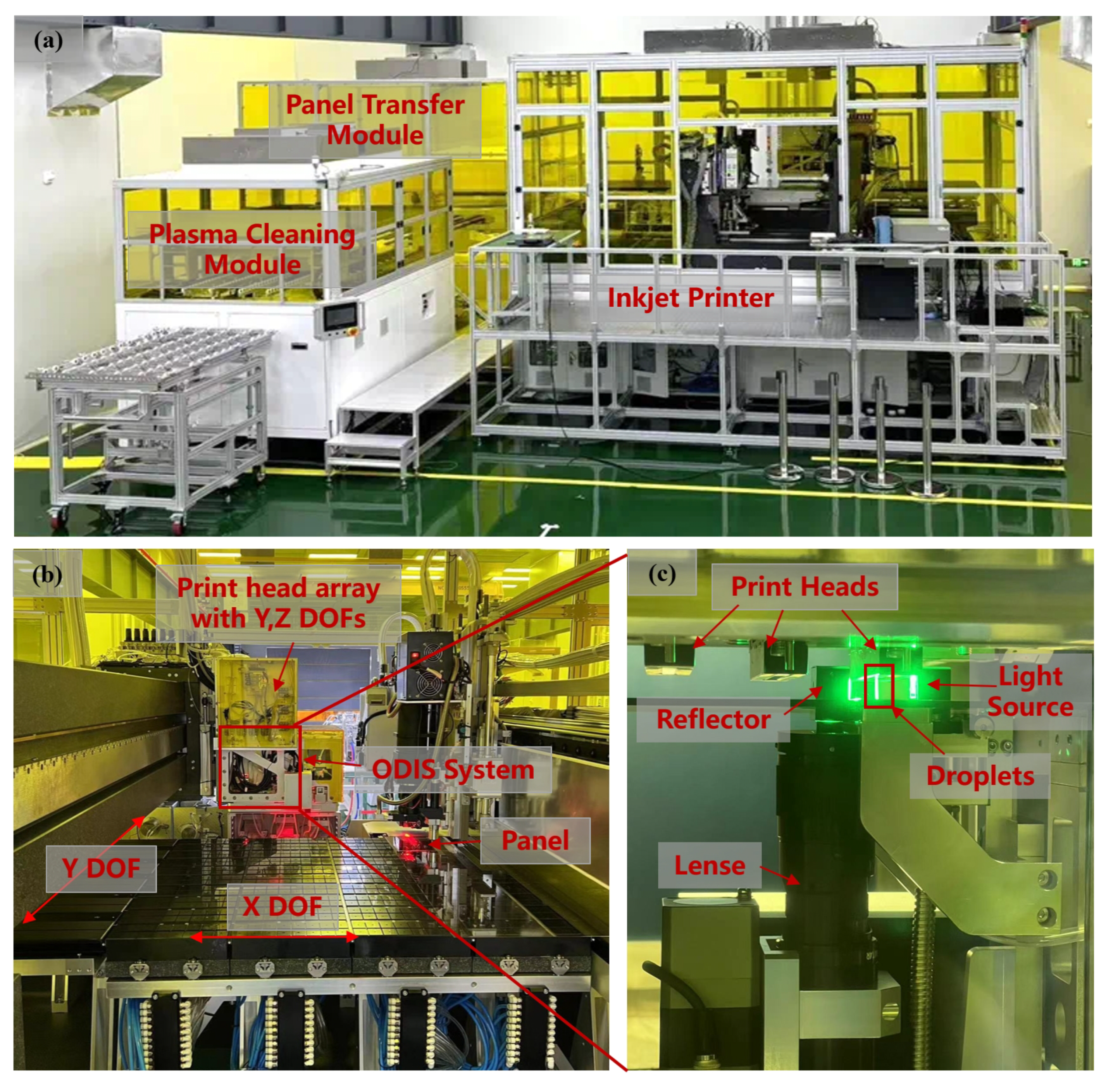

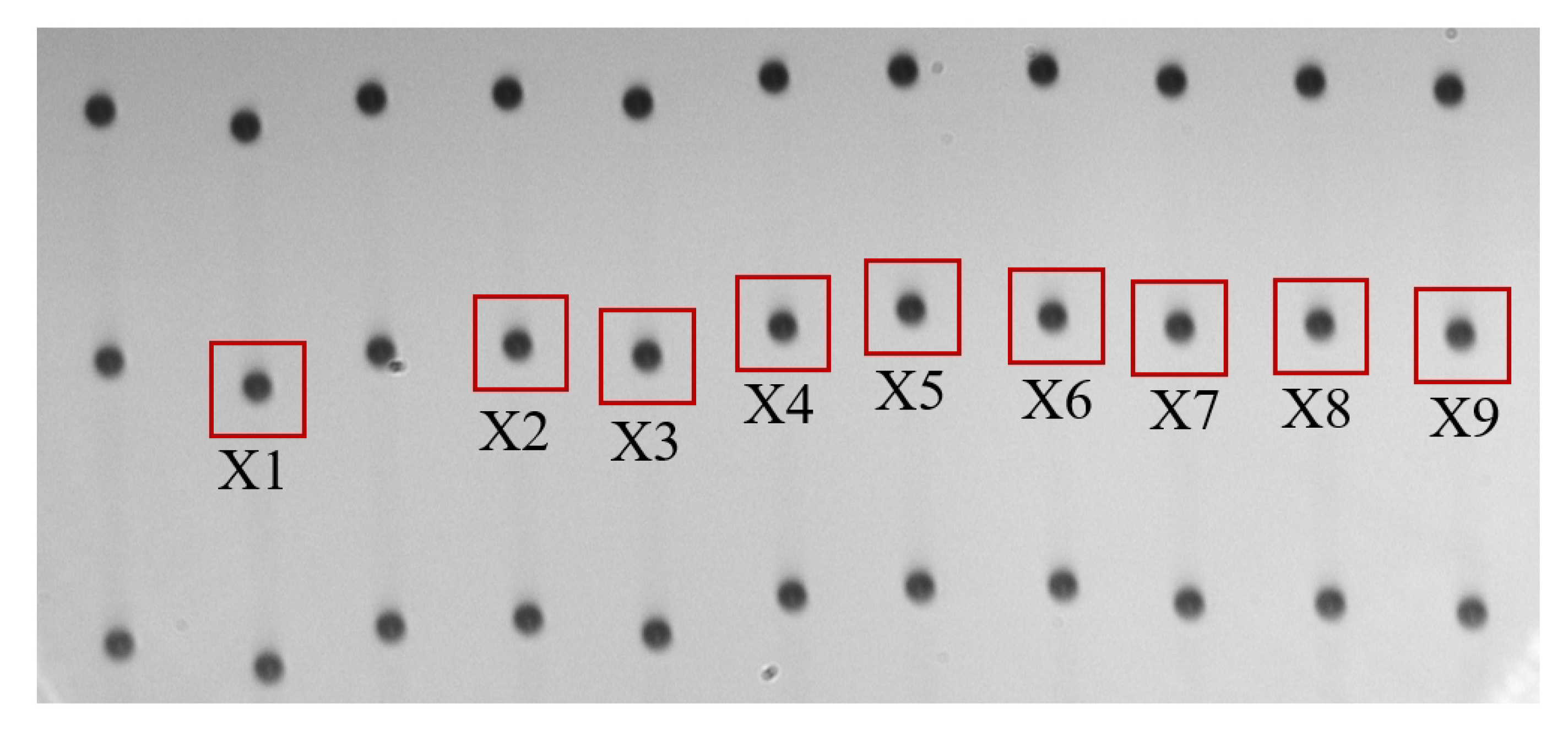

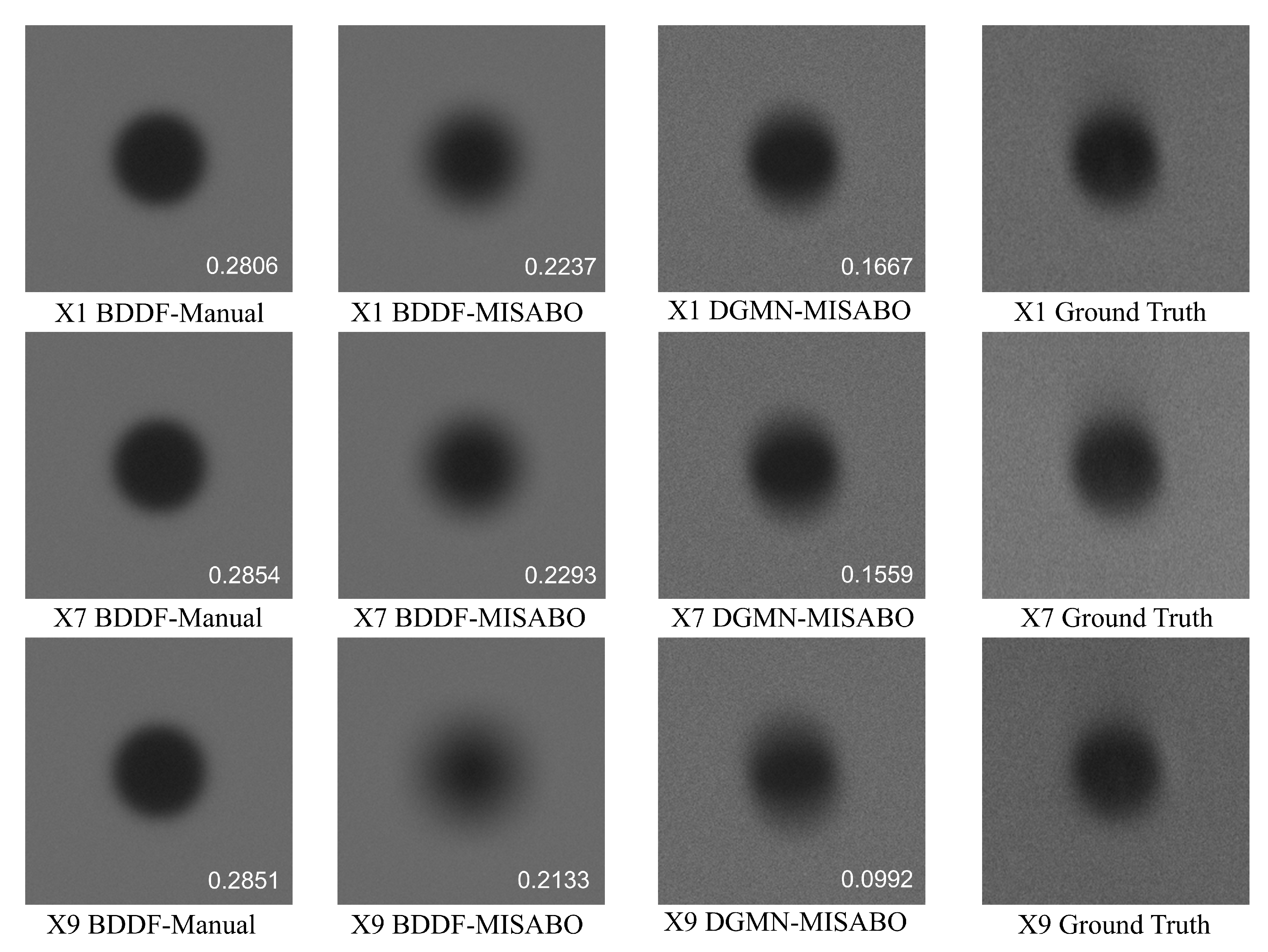

4.2. Performance of Synthetic Droplet Image Generation

4.2.1. Experimental Setup

4.2.2. Evaluation Metrics

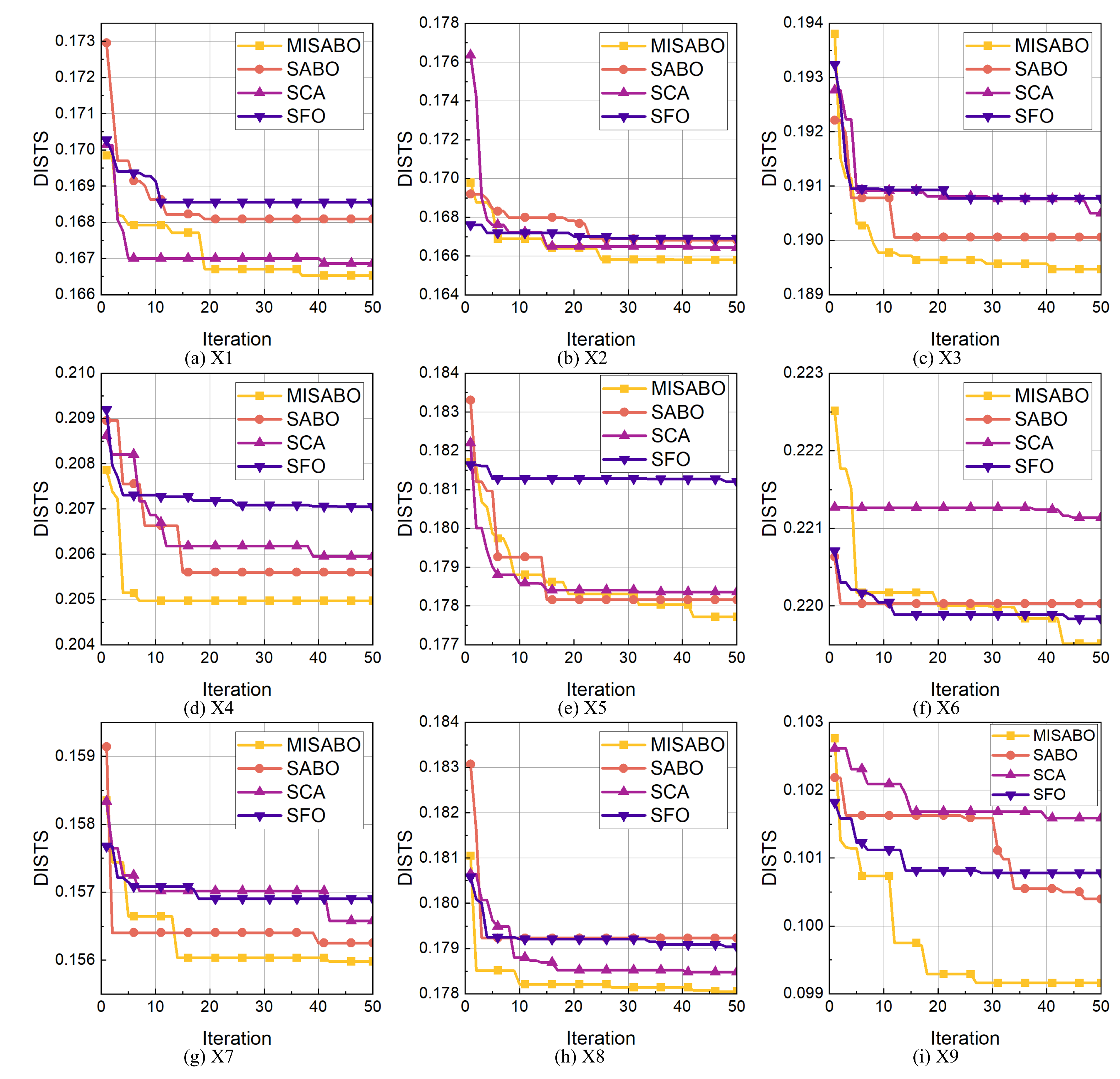

4.2.3. Experimental Results

4.3. Ablation study

4.3.1. Effectiveness of the Proposed DGMN Model

4.3.2. Effectiveness of Integrated Strategies in MISABO

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gather, M.C.; Reineke, S. Recent advances in light outcoupling from white organic light-emitting diodes. Journal of Photonics for Energy 2015, 5, 057607–057607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, G.; Lee, B.R.; Ji, S.; Kim, S.Y.; An, B.W.; Song, M.H.; Park, J.U. High-resolution electrohydrodynamic jet printing of small-molecule organic light-emitting diodes. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 13410–13415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, F.; Feng, C.; Yu, Y.; Hu, H.; Li, F. Efficient inkjet-printed blue OLED with boosted charge transport using host doping for application in pixelated display. Optical Materials 2020, 101, 109755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Ali, M.U.; Peng, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, D.; Zou, T.; Li, Y.; Jiao, S.; Chen, S.j. Inkjet printed uniform quantum dots as color conversion layers for full-color OLED displays. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 2103–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Song, K.; Mao, F.; Yin, Z. Autolabeling-enhanced active learning for cost-efficient surface defect visual classification. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2020, 70, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psarommatis, F.; Sousa, J.; Mendonça, J.P.; Kiritsis, D. Zero-defect manufacturing the approach for higher manufacturing sustainability in the era of industry 4.0: a position paper. International Journal of Production Research 2022, 60, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, W.; Yue, X.; Zhao, Z.; Yin, Z. Intelligent path planning algorithm system for printed display manufacturing using graph convolutional neural network and reinforcement learning. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2025, 79, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, J.; Yang, H.; Yin, Z. Accurate stereo-vision-based flying droplet volume measurement method. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2021, 71, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Jian-kui, C.; Xiao, Y.; Jing-kai, X.; Jia-con, X.; Guo-xiong, G. Forming control method of inkjet printing OLED emitting layer pixel pit film. Chinese Journal of Liquid Crystal & Displays 2022, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, X.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, H.; Yin, Z. Intelligent control system for droplet volume in inkjet printing based on stochastic state transition soft actor–critic DRL algorithm. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2023, 68, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Chen, J.; Yin, Z. Multi-scale conditional diffusion model for deposited droplet volume measurement in inkjet printing manufacturing. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2023, 71, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Chen, J.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Xiong, J.; Yin, Z. Multinozzle Droplet Volume Distribution Control in Inkjet Printing Based on Multiagent Soft Actor–Critic Network. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2024.

- Qiao, H.; Chen, J.; Huang, X. A Survey of Brain-Inspired Intelligent Robots: Integration of Vision, Decision, Motion Control, and Musculoskeletal Systems. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2022, 52, 11267–11280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.S.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.; Seong, D.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Chang, S.; Park, J.; Lee, S.J.; Shin, J.K. Effects of aperture diameter on image blur of CMOS image sensor with pixel apertures. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2019, 68, 1382–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, J.; Yang, H.; Yin, Z. Prior Guided Multi-Scale Dynamic Deblurring Network for Diffraction Image Restoration in Droplet Measurement. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023.

- Lin, X.; Ren, C.; Liu, X.; Huang, J.; Lei, Y. Unsupervised image denoising in real-world scenarios via self-collaboration parallel generative adversarial branches. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2023, pp.

- Liu, Q.; Yang, H.; Chen, J.; Yin, Z. Multiframe super-resolution with dual pyramid multiattention network for droplet measurement. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustsson, E.; Timofte, R. Ntire 2017 challenge on single image super-resolution: Dataset and study. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 2017, pp. 126–135.

- Zeyde, R.; Elad, M.; Protter, M. On single image scale-up using sparse-representations. In Proceedings of the Curves and Surfaces: 7th International Conference, Avignon, France, 2010, Revised Selected Papers 7. Springer, 2010, June 24-30; pp. 711–730.

- Hendrycks, D.; Dietterich, T. Benchmarking neural network robustness to common corruptions and perturbations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.12261 2019.

- Li, S.; Zhang, G.; Luo, Z.; Liu, J. DFAN: Dual Feature Aggregation Network for Lightweight Image Super-Resolution. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2022, 2022, 8116846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Tan, T. Efficient super resolution by recursive aggregation. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR). IEEE; 2021; pp. 8592–8599. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, M.C.; Ng, S.C.; Leung, M.F.; Che, H. A metaheuristic-based framework for index tracking with practical constraints. Complex & Intelligent Systems 2022, 8, 4571–4586. [Google Scholar]

- Rezk, H.; Fathy, A.; Aly, M.; Ibrahim, M.N. Energy Management Control Strategy for Renewable Energy System Based on Spotted Hyena Optimizer. Computers, Materials & Continua 2021, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abderazek, H.; Yildiz, A.R.; Mirjalili, S. Comparison of recent optimization algorithms for design optimization of a cam-follower mechanism. Knowledge-Based Systems 2020, 191, 105237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Chang, V.; Mohamed, R. HSMA_WOA: A hybrid novel Slime mould algorithm with whale optimization algorithm for tackling the image segmentation problem of chest X-ray images. Applied soft computing 2020, 95, 106642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadimi-Shahraki, M.H.; Taghian, S.; Mirjalili, S.; Zamani, H.; Bahreininejad, A. GGWO: Gaze cues learning-based grey wolf optimizer and its applications for solving engineering problems. Journal of Computational Science 2022, 61, 101636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, H.; Heidari, A.A.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Pan, Z. Orthogonal learning covariance matrix for defects of grey wolf optimizer: Insights, balance, diversity, and feature selection. Knowledge-Based Systems 2021, 213, 106684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadimi-Shahraki, M.H.; Taghian, S.; Mirjalili, S. An improved grey wolf optimizer for solving engineering problems. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 166, 113917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell-Kligler, S.; Shocher, A.; Irani, M. Blind super-resolution kernel estimation using an internal-gan. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zuo, W.; Zhang, L. Learning a single convolutional super-resolution network for multiple degradations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp.

- Gu, J.; Lu, H.; Zuo, W.; Dong, C. Blind super-resolution with iterative kernel correction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp.

- Huang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Tan, T. Unfolding the alternating optimization for blind super resolution. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 5632–5643. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Liang, J.; Zhang, M. A degradation model for simultaneous brightness and sharpness enhancement of low-light image. Signal Processing 2021, 189, 108298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, M.; Gu, S.; Timofte, R. Frequency separation for real-world super-resolution. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW). IEEE; 2019; pp. 3599–3608. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.; Hayashi, H.; Rundo, L.; Araki, R.; Shimoda, W.; Muramatsu, S.; Furukawa, Y.; Mauri, G.; Nakayama, H. GAN-based synthetic brain MR image generation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 15th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI 2018). IEEE; 2018; pp. 734–738. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani, M.; Montazeri, Z.; Malik, O. Optimal sizing and placement of capacitor banks and distributed generation in distribution systems using spring search algorithm. International Journal of Emerging Electric Power Systems 2020, 21, 20190217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehbozorgi, S.; Ehsanifar, A.; Montazeri, Z.; Dehghani, M.; Seifi, A. Line loss reduction and voltage profile improvement in radial distribution networks using battery energy storage system. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 4th International Conference on Knowledge-Based Engineering and Innovation (KBEI). IEEE; 2017; pp. 0215–0219. [Google Scholar]

- Bouaraki, M.; Recioui, A. Optimal placement of power factor correction capacitors in power systems using Teaching Learning Based Optimization. Algerian Journal of Signals and Systems 2017, 2, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S. Genetic algorithm. Evolutionary algorithms and neural networks: theory and applications 2019, pp. 43–55.

- Wang, D.; Tan, D.; Liu, L. Particle swarm optimization algorithm: an overview. Soft computing 2018, 22, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of ICNN’95-international conference on neural networks. ieee, 1995, Vol. 4, pp. 1942–1948.

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Advances in engineering software 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fister, I.; Fister Jr, I.; Yang, X.S.; Brest, J. A comprehensive review of firefly algorithms. Swarm and evolutionary computation 2013, 13, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kenawy, E.S.M.; Mirjalili, S.; Ibrahim, A.; Alrahmawy, M.; El-Said, M.; Zaki, R.M.; Eid, M.M. Advanced meta-heuristics, convolutional neural networks, and feature selectors for efficient COVID-19 X-ray chest image classification. Ieee Access 2021, 9, 36019–36037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourouis, S.; Band, S.S.; Mosavi, A.; Agrawal, S.; Hamdi, M. Meta-heuristic algorithm-tuned neural network for breast cancer diagnosis using ultrasound images. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12, 834028. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, M.A.; Bedi, S. Survey on SVM and their application in image classification. International Journal of Information Technology 2021, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canayaz, M. MH-COVIDNet: Diagnosis of COVID-19 using deep neural networks and meta-heuristic-based feature selection on X-ray images. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2021, 64, 102257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, S.P.; Alexandropoulos, S.A.N.; Pardalos, P.M.; Vrahatis, M.N. No free lunch theorem: A review. Approximation and optimization: Algorithms, complexity and applications 2019, pp. 57–82.

- Moustafa, G.; Tolba, M.A.; El-Rifaie, A.M.; Ginidi, A.; Shaheen, A.M.; Abid, S. A Subtraction-Average-Based Optimizer for Solving Engineering Problems with Applications on TCSC Allocation in Power Systems. Biomimetics (Basel) 2023, 8, El–Rifaie. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian, B.; Dirk, J.; Gregor P, H. Sampling Based on Sobol’ Sequences for Monte Carlo Techniques Applied to Building Simulations, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Guan, J.; Wu, H.; Chen, Y.; Xia, X. Lens imaging opposition-based learning for differential evolution with cauchy perturbation. Applied Soft Computing 2024, 152, 111211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tizhoosh, H.R. Opposition-Based Learning: A New Scheme for Machine Intelligence. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Modelling, Control and Automation and International Conference on Intelligent Agents, Web Technologies and Internet Commerce (CIMCA-IAWTIC’06), 2005, Vol. 1, pp. 695–701. [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S. SCA: a sine cosine algorithm for solving optimization problems. Knowledge-based systems 2016, 96, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.F.; da Cunha, S.S.; Ancelotti, A.C. A sunflower optimization (SFO) algorithm applied to damage identification on laminated composite plates. Engineering with Computers 2019, 35, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Ma, K.; Wang, S.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: Unifying structure and texture similarity. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2020, 44, 2567–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Function | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | ||

| 0 | ||

| 0 | ||

| 0 | ||

| 0 | ||

|

|

0 | |

|

|

0 | |

|

where, and |

0 |

| Function | Metric | MISABO | SABO | SCA | SFO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | mean | 0.00E+00 | 8.50E-201 | 4.36E+00 | 1.39E-18 |

| std | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 6.97E+00 | 3.25E-18 | |

| best | 0.00E+00 | 9.50E-204 | 4.24E-02 | 1.09E-21 | |

| worst | 0.00E+00 | 9.45E-200 | 3.12E+01 | 1.66E-17 | |

| F2 | mean | 0.00E+00 | 1.38E-113 | 7.91E-03 | 1.52E-19 |

| std | 0.00E+00 | 4.04E-113 | 1.25E-02 | 6.80E-09 | |

| best | 0.00E+00 | 4.14E-115 | 3.72E-04 | 7.52E-11 | |

| worst | 0.00E+00 | 2.19E-112 | 5.67E-02 | 3.13E-08 | |

| F3 | mean | 0.00E+00 | 1.96E-30 | 5.49E+03 | 5.03E-16 |

| std | 0.00E+00 | 1.06E-29 | 4.15E+03 | 8.83E-16 | |

| best | 0.00E+00 | 5.50E-83 | 4.25E+02 | 9.04E-20 | |

| worst | 0.00E+00 | 5.83E-29 | 1.69E+04 | 4.04E-15 | |

| F4 | mean | 0.00E+00 | 9.36E-78 | 2.62E-01 | 2.11E-10 |

| std | 0.00E+00 | 1.32E-77 | 1.12E-01 | 2.60E-10 | |

| best | 0.00E+00 | 5.62E-79 | 2.32E+00 | 3.62E-12 | |

| worst | 0.00E+00 | 4.82E-77 | 4.43E+01 | 1.11E-09 | |

| F5 | mean | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 3.09E+01 | 0.00E+00 |

| std | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 3.14E+01 | 0.00E+00 | |

| best | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 6.07E-04 | 0.00E+00 | |

| worst | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 9.06E+01 | 0.00E+00 | |

| F6 | mean | 4.44E-16 | 3.99E-15 | 1.18E-01 | 5.87E-10 |

| std | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 9.46E+00 | 6.32E-10 | |

| best | 4.44E-16 | 3.99E-15 | 8.22E-03 | 9.52E-12 | |

| worst | 4.44E-16 | 3.99E-15 | 2.04E-01 | 2.23E-09 | |

| F7 | mean | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 7.78E-01 | 0.00E+00 |

| std | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 2.28E-01 | 0.00E+00 | |

| best | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 2.72E-01 | 0.00E+00 | |

| worst | 0.00E+00 | 0.00E+00 | 1.09E+00 | 0.00E+00 | |

| F8 | mean | 7.08E-04 | 1.72E-01 | 1.36E+01 | 3.62E-01 |

| std | 2.46E-04 | 7.08E-02 | 2.64E+01 | 3.53E-01 | |

| best | 3.56E-04 | 5.88E-02 | 9.46E-01 | 7.91E-04 | |

| worst | 1.50E-03 | 3.52E-01 | 1.43E+02 | 1.33E+00 |

| Parameter | Value Range |

|---|---|

| Lense NA | |

| Diffraction kernel size | |

| Diffraction kernel scale | |

| Mixed Gaussian kernel size | |

| Mixed Gaussian kernel sigma | |

| Motion kernel size | |

| Droplet flying angle |

| Image | MISABO | SABO | SCA | SFO | Baseline* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 0.1665 | 0.1681 | 0.1669 | 0.1686 | 0.2806 |

| X2 | 0.1658 | 0.1668 | 0.1664 | 0.1669 | 0.2703 |

| X3 | 0.1895 | 0.1901 | 0.1905 | 0.1908 | 0.2734 |

| X4 | 0.2049 | 0.2056 | 0.2060 | 0.2071 | 0.2714 |

| X5 | 0.1777 | 0.1782 | 0.1784 | 0.1812 | 0.2831 |

| X6 | 0.2195 | 0.2200 | 0.2211 | 0.2198 | 0.2780 |

| X7 | 0.1559 | 0.1563 | 0.1566 | 0.1570 | 0.2854 |

| X8 | 0.1781 | 0.1792 | 0.1785 | 0.1790 | 0.2758 |

| X9 | 0.0992 | 0.1004 | 0.1016 | 0.1008 | 0.2851 |

| Average | 0.1730 | 0.1739 | 0.1740 | 0.1746 | 0.2781 |

| Methods | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 (Ours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | ||||

| Motion Blur | ||||

| Adaptive Noise | ||||

| DISTS | 0.2781 */0.1905 | 0.1884 | 0.1771 | 0.1730 |

| Methods | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Sobol | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| LensOBL | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| DLH | ✔ | |||

| DISTS | 0.1739 | 0.1737 | 0.1733 | 0.1730 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).