1. Introduction

Heart failure presents a major burden to society, affecting approximately 63 million people worldwide [

1,

2]. Hypertension is a significant risk factor for heart failure, and in the Framingham heart study, hypertension predated 91% of new-onset heart failure cases [

3]. Therefore, identifying the underlying mechanisms of cardiac remodeling and dysfunction in response to hypertension could help to prevent hypertension from progressing into heart failure.

Angiotensin-II (Ang-II) is a major part of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system that canonically regulates blood pressure [

4]. Ang-II has been shown to induce cardiac fibrosis by activating cardiac fibroblasts via the Angiotensin-II type I receptor [

5]. p53 has previously been shown to regulate the proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts in a model of pressure overload-induced cardiac remodeling [

6]. Furthermore, p53 signaling has been implicated in the pathophysiology of diabetes-induced cardiac fibrosis [

7]. p53 has previously been shown to be involved in Ang-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy [

8]; however, to our knowledge the therapeutic potential of blocking p53-mediated responses to Ang-II has yet to be investigated.

Acetylation mutant p53 (p53aceKO) mice have previously been extensively characterized in tumors [

9]. In this model, the p53 protein loses some, but not all, of its normal functions; in particular, p53-mediated apoptosis, growth arrest, and ferroptosis are not activated in this model [

9,

10]. Our lab has previously established that p53 acetylation is required for cardiac remodeling in a mouse model of heart failure [

11]. Therefore, we hypothesized that p53aceKO mice would be protected against cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction in response to Ang-II infusion.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals

Mice expressing p53 with mutations at lysine residues K98, K117, K161, and K162 (replacing lysine with arginine, p53

4KR, p53aceKO) on the C57BL/6J background were provided by Dr Wei Gu at the Columbia University. Wild-type Control mice of the 129S1/SvImJ strain were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (strain number 002448). All experimental mice were maintained in the Laboratory Animal Facility at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC), fed laboratory standard chow and water and housed in individually ventilated cages. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at UMMC (Protocol ID: 1564, 1189) and were in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Pub. No. 85-23, Revised 1996). Because there are known sex differences in response to Ang-II infusion [

12], this study utilized only male mice, with future studies to evaluate this pathway in females.

Mice received either a micro-osmotic pump implant or a sham procedure on Day 0. On Day 29, mice were weighed, euthanized and hearts excised, weighed, and fixed in 10% Neutral Buffer Formalin (Epredia #51401).

2.2. Micro-Osmotic Pump Implant or Sham Procedure

5-8-month-old male mice were divided into groups as follows (n=6 mice per group): Control + sham, Control + Ang-II, p53aceKO + sham, and p53aceKO + Ang-II. Ang-II was purchased from BACHEM (#4006473). Micro-osmotic pumps were purchased from Alzet (model 1004) and prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions to deliver 1μg/kg body weight/min of Ang-II for 28 days. Pump implant or sham procedures were performed on Day 0 as previously described [

13]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and the pump implanted subcutaneously. The sham procedure was identical except that no pump was implanted. Mice were administered carprofen at a dose of 5mg/kg body weight subcutaneously after the procedure and for two days following the procedure.

2.3. Blood Pressure Measurement

Blood pressure was measured via tail-cuff without anesthesia using the CODA Non-Invasive Blood Pressure System (Kent Scientific). Mice were trained to become acclimated to restraint for 20-30 minutes per day for 4 days prior to initial measurement.

2.4. Transthoracic Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed on mice as previously described [

14] on Days 0, 14, and 28. Anesthesia of mice was achieved via inhalation of 1–1.5% isoflurane mixed with 100% medical oxygen. The Vevo 3100 Preclinical Imaging Platform with an MX400 transducer (FUJIFILM Visual Sonics Inc.) was used for measurement. A heart rate between 450 and 500 beats per minute was maintained for the duration of measurement. Analysis of M-mode cine loops was performed using Vevo LAB software (FUJIFILM Visual Sonics Inc., Canada) to obtain ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), and myocardial parameters, including left ventricle (LV) end-systolic diameter (Diameter;s), LV end-diastolic diameter (Diameter;d), LV end-systolic volume (Volume;s), LV end-diastolic volume (Volume;d), thickness of the LV anterior wall at end-systole and end-diastole (LVAW;s and LVAW;d) and thickness of the LV posterior wall at end-systole and end-diastole (LVPW;s and LVPW;d), stroke volume (SV), and cardiac output (CO) [

15,

16,

17].

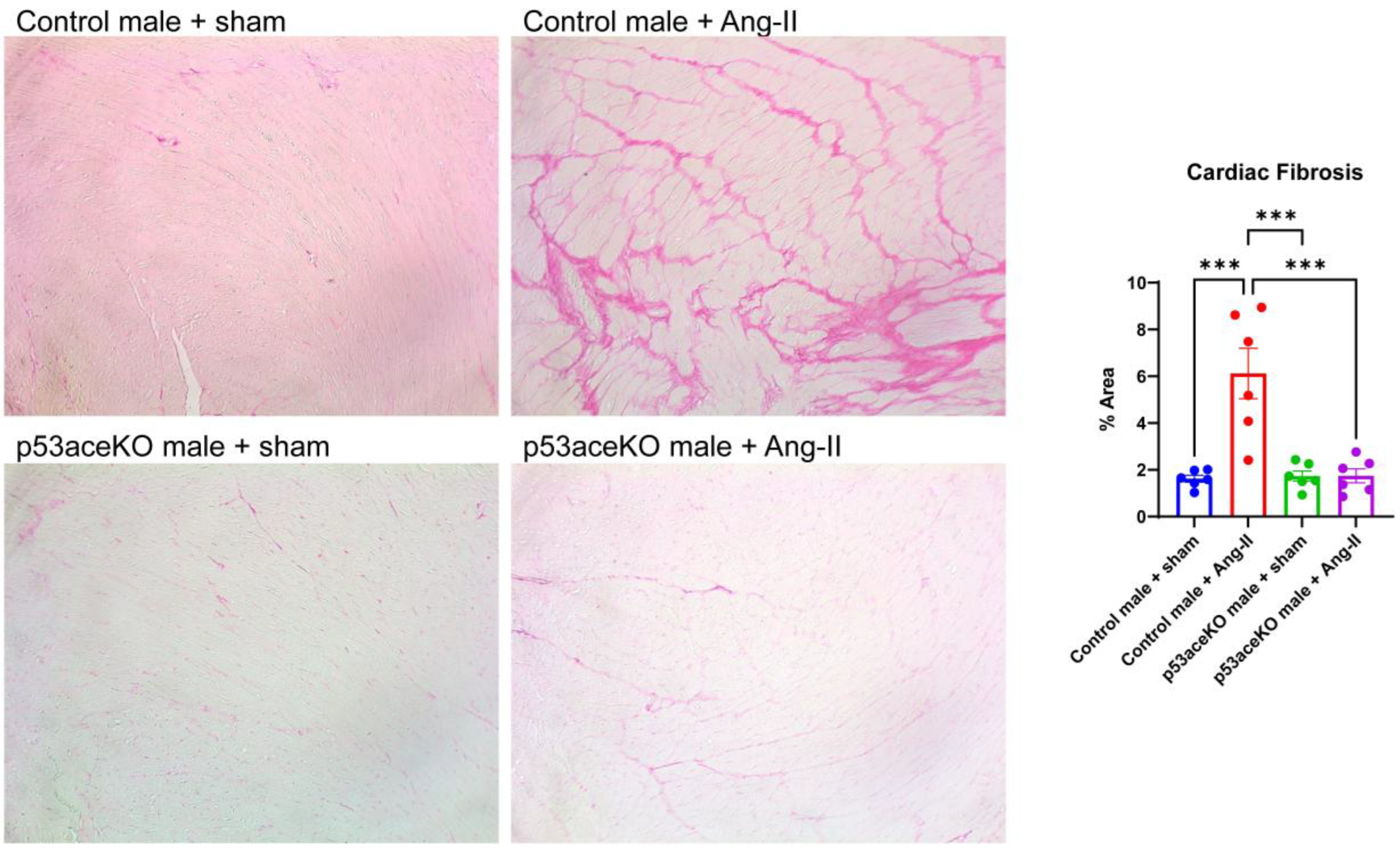

2.5. Histology

Formalin-fixed heart samples were processed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at a 5μm thickness. Picrosirius red staining was used to evaluate cardiac fibrosis. 15-20 fields were randomly selected per mouse using a Nikon Labophot microscope at 10x magnification with an AmScope camera. Fibrosis was quantified as a percent area using the ratio of Picrosirius red stained area to the total myocardial area using ImageJ software.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between multiple groups over time were performed using a Two-Way ANOVA. Comparisons between multiple groups at a single time point were performed using a One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

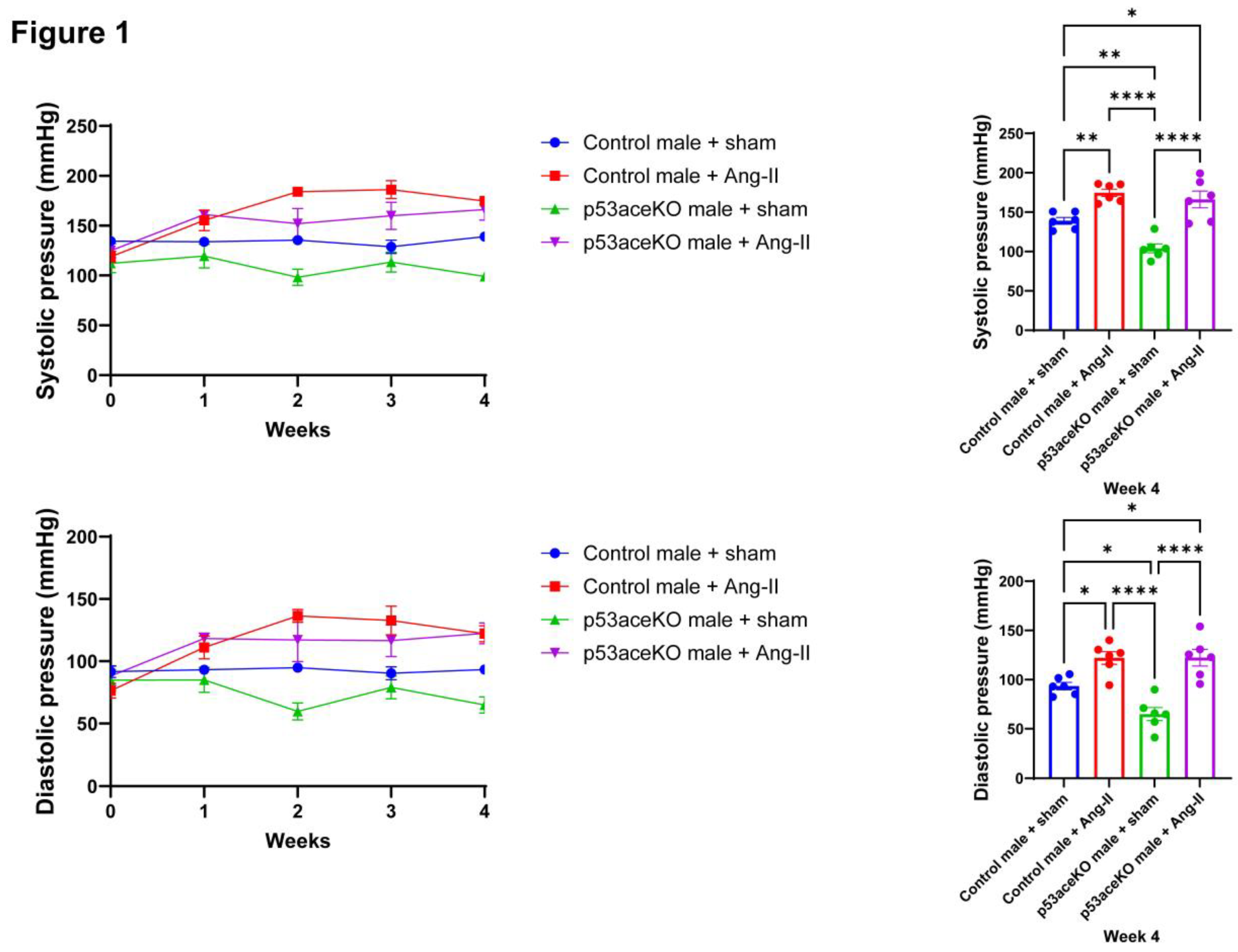

3.1. Both Control and p53aceKO Mice Exhibit Increased Blood Pressure Following Ang-II Infusion

Following four weeks of Ang-II infusion, both Control and p53aceKO mice exhibit significant increases in systolic and diastolic blood pressures compared to their sham counterparts. Intriguingly, p53aceKO mice exhibit lower baseline systolic and diastolic pressures compared to the Controls (

Figure 1).

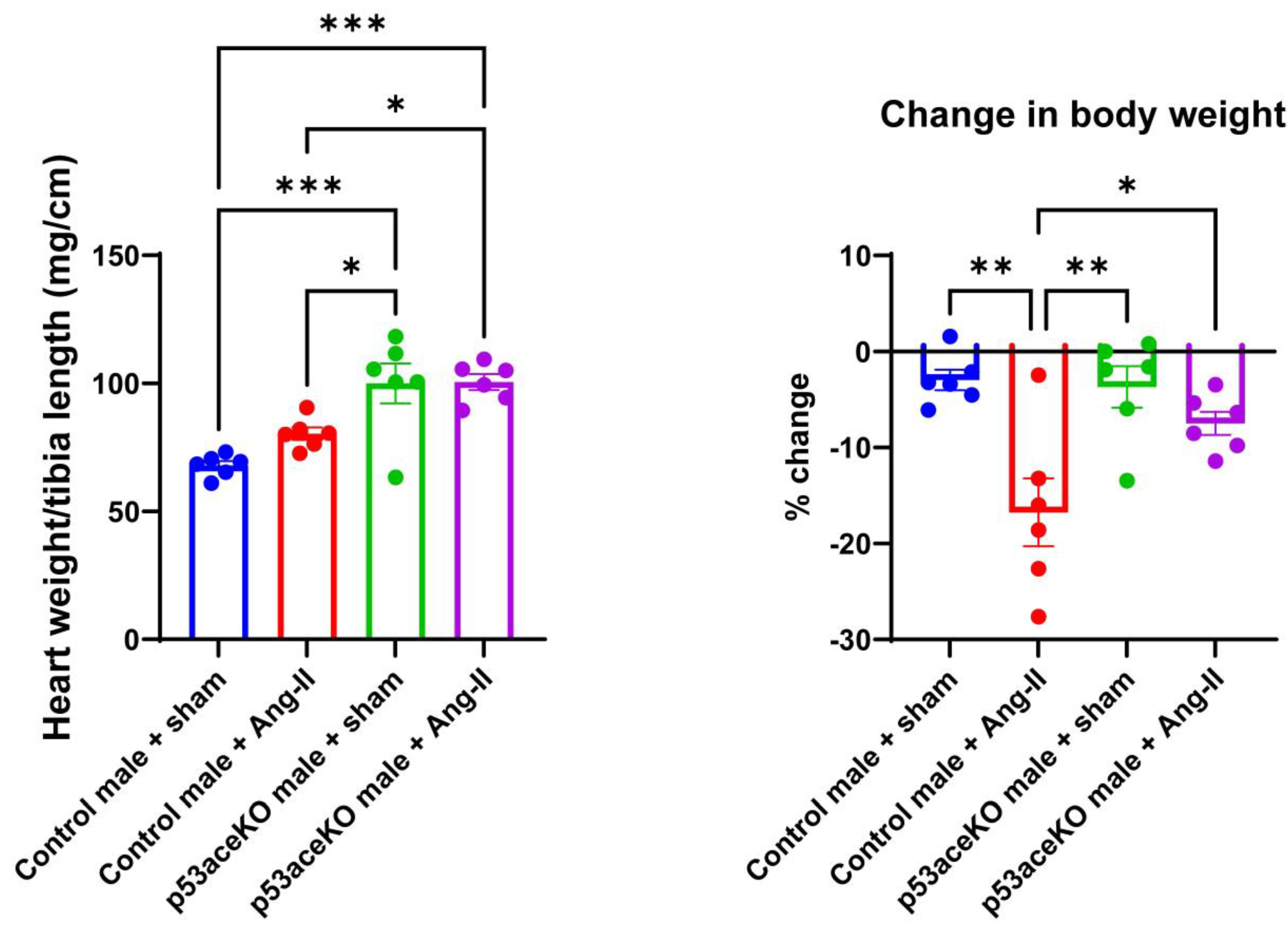

3.2. p53aceKO Mice Have a Higher Heart Weight to Tibia Length Ratio at Baseline and Lose Less Weight over the Course of Ang-II Infusion than Control Mice

Interestingly, p53aceKO mice have a significantly higher heart weight to tibia length ratio compared to Control mice. While Control mice receiving Ang-II have a trend towards increase in heart weight to tibia length, p53aceKO mice receiving Ang-II do not. Additionally, Control mice receiving Ang-II have a significant loss in body weight compared to the sham, while p53aceKO mice receiving Ang-II do not (

Figure 2).

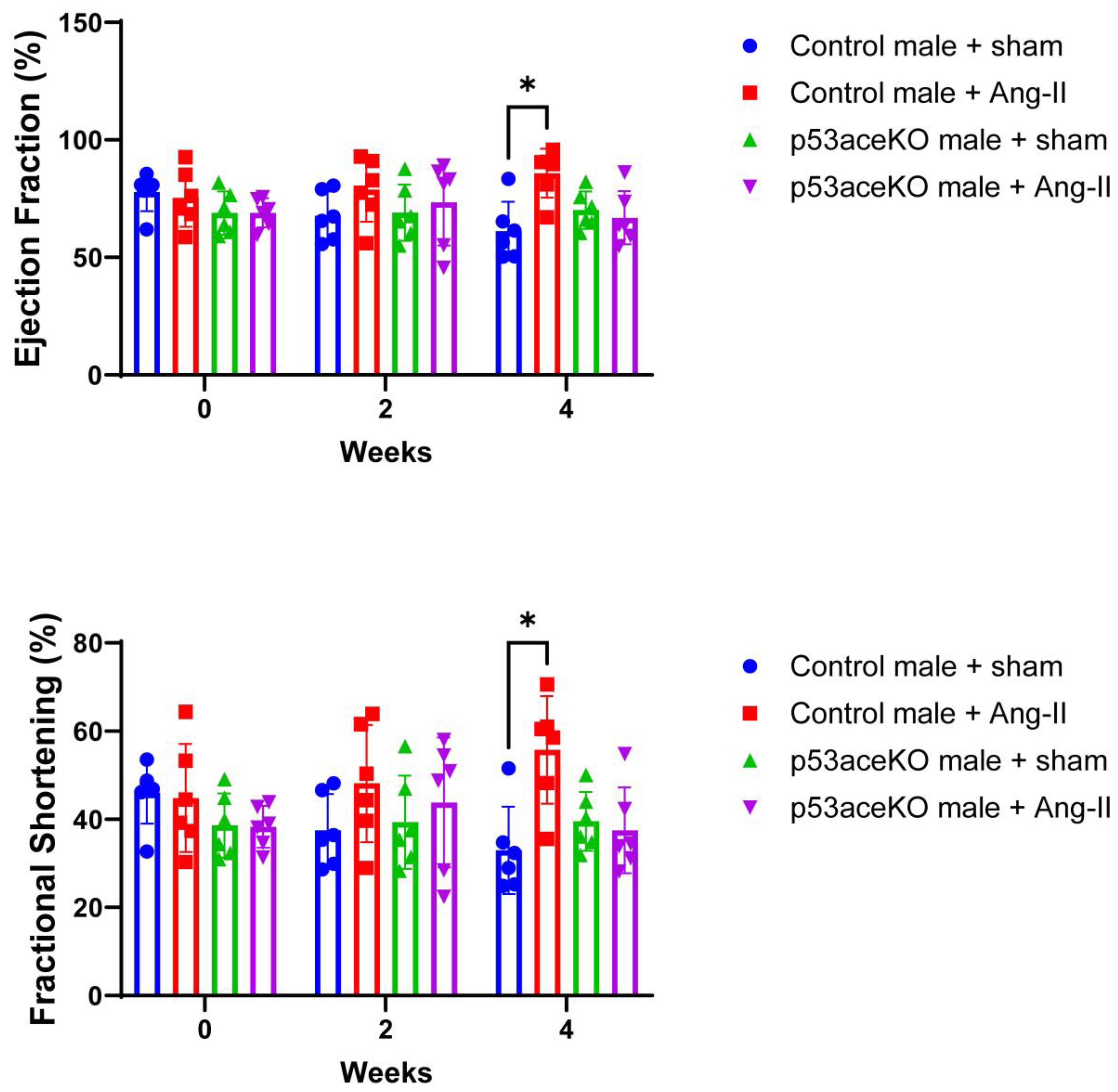

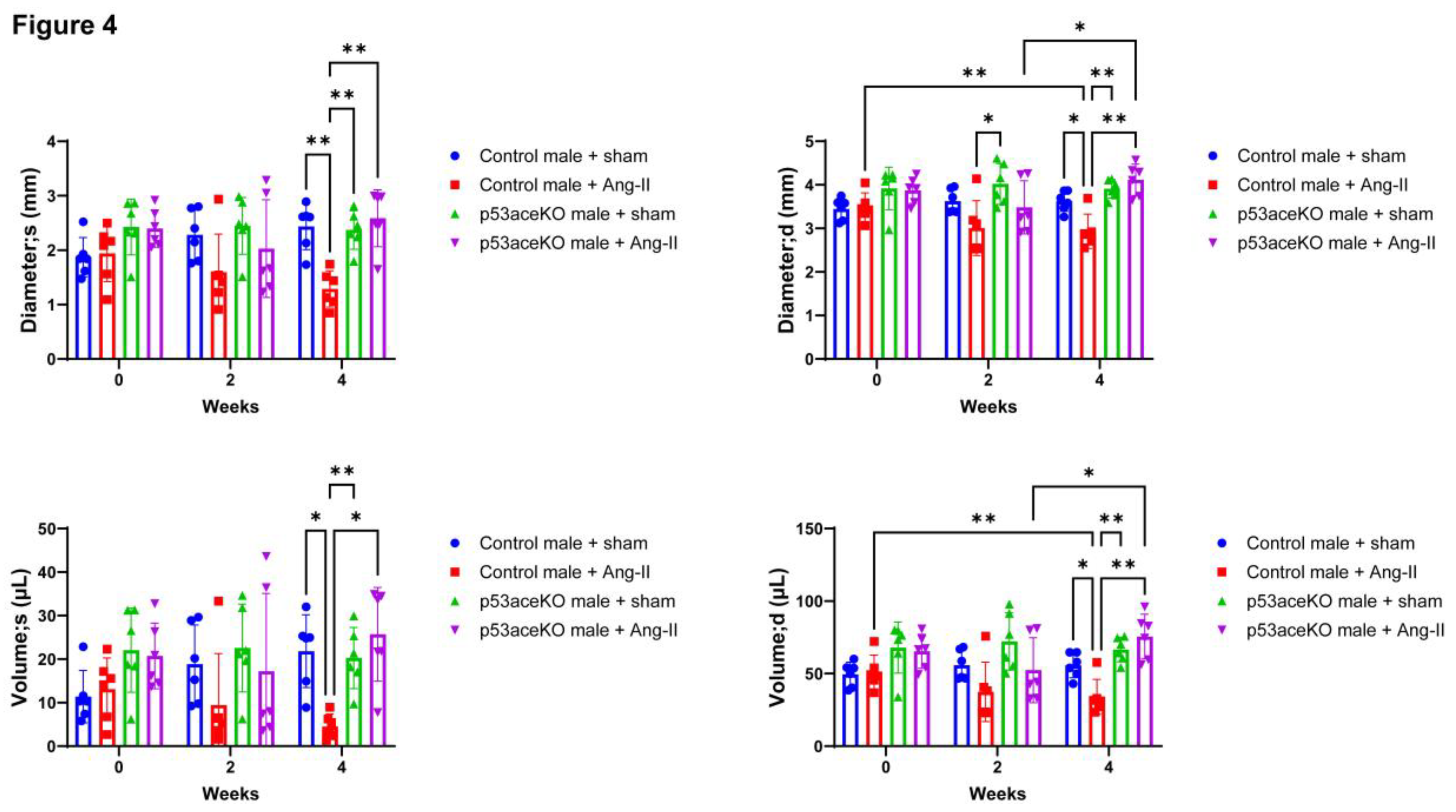

3.3. p53aceKO Mice Do not Exhibit the Ang-II Infusion-Induced Alterations in Cardiac Function Seen in Control Mice

Control mice receiving Ang-II exhibit increased EF and FS compared to the sham, while p53aceKO mice do not (

Figure 3). Furthermore, while Control mice treated with Ang-II have significant decreases in left ventricular diameter and volume both at end-systole and end-diastole, p53aceKO mice receiving Ang-II demonstrate no significant alterations in any of these parameters (

Figure 4). p53aceKO mice also exhibit no significant changes in LVAW;s, LVAW;d, LVPW;s, or LVPW;d following Ang-II infusion, while Control mice have significant increases in each of these following Ang-II infusion. Neither Control nor p53aceKO mice receiving Ang-II demonstrated significant alterations in CO or SV (

Table 1).

3.4. p53aceKO Mice Do Not Exhibit the Ang-II-Induced Cardiac Fibrosis Seen in Control Mice

Histological analysis demonstrated that, while Control mice receiving Ang-II have significant cardiac fibrosis, p53aceKO mice receiving Ang-II do not (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The present study identified for the first time that p53 acetylation mutation is protective against Ang-II infusion-induced cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis. The p53 acetylation mutation of p53aceKO mice has previously been extensively characterized [

9]. This model exhibits disruptions in the apoptosis and growth arrest functions of p53, as well as its ability to regulate various proteins, and its ability to induce ferroptosis [

9,

10].

Interestingly, p53aceKO mice receiving Ang-II did not lose as much weight compared to Control mice treated with Ang-II. Control mice receiving Ang-II exhibited increases in EF and FS, due to hypertrophy of the LV walls leading to decreased LV diameter and volume both at end-systole and end-diastole. p53aceKO mice were seemingly protected from this effect, as they exhibited no changes in these parameters following Ang-II treatment despite their significant elevations in systolic and diastolic blood pressures. Histologically, p53aceKO mice did not exhibit increased fibrosis in the heart following Ang-II treatment, suggesting that mechanistically p53 acetylation mutation prevents cardiac remodeling. It stands to reason that this is due to the inhibition of p53 activity in this model, and more work is necessary to further elucidate whether one or more of the impaired pathways is responsible for cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction in response to Ang-II. Our lab has previously identified that p53aceKO in SIRT3 knockout mice reduced cardiac fibrosis and activation of the ferroptosis cell death pathway in this model [

11]. We have also previously shown that p53aceKO mice exhibit improved endothelial cell function in a pressure overload-induced model of heart failure [

18]. These prior studies support the idea that p53 acetylation may mediate cardiac protection against Ang-II-induced cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis via suppressing p53-mediated ferroptosis and improving vascular function in the heart. Further studies are necessary to sufficiently elucidate the precise mechanism by which p53 acetylation mediates these beneficial effects on the heart.

p53 has been shown to regulate the proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts in a model of pressure overload-induced heart failure, with p53 knockout resulting in hyperproliferation of cardiac fibroblasts and ultimately extensive cardiac fibrosis [

6]. Because p53aceKO mice still express the p53 protein with many of its activities intact, it is possible that this model acts to suppress cardiac fibrosis in response to Ang-II infusion by suppressing cardiac fibroblast activity and proliferation. This is yet another pathway that remains to be elucidated, and the impacts of p53aceKO on specific cell types would benefit from in-depth study.

It is important to note that this study utilized only male mice, due to the known sex differences in response to Ang-II [

12]. Future studies are necessary to determine whether the protective effects of p53 acetylation mutation are universal between sexes, or if this effect is exclusive to males.

Here, we showed that mutation of p53 acetylation is protective against Ang-II infusion-induced cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction, suggesting a novel role for p53 acetylation in the pathophysiology of hypertension. Acetylation of p53 may therefore be a novel therapeutic target to treat cardiac complications in patients with hypertension, and is worth further investigation.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL151536, JX Chen) and the University of Mississippi Medical Center Intramural Research Support Program (IRSP, H.Z.).

References

- G. B. D. Disease, I. G. B. D. Disease, I. Injury, and C. Prevalence, “Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017,” Lancet, vol. 392, no. 10159, pp. 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. A. Heidenreich et al., “Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association,” Circ Heart Fail, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 20 May; -19. [CrossRef]

- D. Levy, M. G. D. Levy, M. G. Larson, R. S. Vasan, W. B. Kannel, and K. K. Ho, “The progression from hypertension to congestive heart failure,” JAMA, vol. 275, no. 20, pp. 1557-62, -29 1996. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8622246. 22 May.

- Y. C. Zhu, Y. Z. Y. C. Zhu, Y. Z. Zhu, N. Lu, M. J. Wang, Y. X. Wang, and T. Yao, “Role of angiotensin AT1 and AT2 receptors in cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac remodelling,” Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol, vol. 30, no. 12, pp. 2003; -8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Kawano et al., “Angiotensin II has multiple profibrotic effects in human cardiac fibroblasts,” Circulation, vol. 101, no. 10, pp. 1130; -7. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu et al., “p53 Regulates the Extent of Fibroblast Proliferation and Fibrosis in Left Ventricle Pressure Overload,” Circ Res, vol. 133, no. 3, pp. 2023; 21. [CrossRef]

- T. Peng et al., “LncRNA Airn alleviates diabetic cardiac fibrosis by inhibiting activation of cardiac fibroblasts via a m6A-IMP2-p53 axis,” Biol Direct, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 2022; 32. [CrossRef]

- C. Lv, L. C. Lv, L. Zhou, Y. Meng, H. Yuan, and J. Geng, “PKD knockdown mitigates Ang II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and ferroptosis via the JNK/P53 signaling pathway,” Cell Signal, vol. 113, p. 1109; 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. J. Wang et al., “Acetylation Is Crucial for p53-Mediated Ferroptosis and Tumor Suppression,” Cell Rep, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 2016; 4. [CrossRef]

- T. Li et al., “Tumor suppression in the absence of p53-mediated cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence,” Cell, vol. 149, no. 6, pp. 1269; -83. [CrossRef]

- H. Su, A. C. H. Su, A. C. Cantrell, J. X. Chen, W. Gu, and H. Zeng, “SIRT3 Deficiency Enhances Ferroptosis and Promotes Cardiac Fibrosis via p53 Acetylation,” Cells, vol. 12, no. 19 May 2023; 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Xue, A. K. B. Xue, A. K. Johnson, and M. Hay, “Sex differences in angiotensin II- induced hypertension,” Braz J Med Biol Res, vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 20 May; -34. [CrossRef]

- X. He, Q. A. X. He, Q. A. Williams, A. C. Cantrell, J. Besanson, H. Zeng, and J. X. Chen, “TIGAR Deficiency Blunts Angiotensin-II-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy in Mice,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 25, no. 2024; 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.C. Cantrell et al., “Ferrostatin-1 specifically targets mitochondrial iron-sulfur clusters and aconitase to improve cardiac function in Sirtuin 3 cardiomyocyte knockout mice,” J Mol Cell Cardiol, vol. 192, pp. 9 May 2024; -47. [CrossRef]

- X. He, H. X. He, H. Zeng, and J. X. Chen, “Ablation of SIRT3 causes coronary microvascular dysfunction and impairs cardiac recovery post myocardial ischemia,” Int J Cardiol, vol. 215, pp. 2016; -57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. K. Tao et al., “Notch3 deficiency impairs coronary microvascular maturation and reduces cardiac recovery after myocardial ischemia,” Int J Cardiol, vol. 236, pp. 2017; 1. [CrossRef]

- H. Zeng, X. H. Zeng, X. He, and J. X. Chen, “Endothelial Sirtuin 3 Dictates Glucose Transport to Cardiomyocyte and Sensitizes Pressure Overload-Induced Heart Failure,” J Am Heart Assoc, vol. 9, no. 11, p. 0158; e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. He et al., “p53 Acetylation Exerts Critical Roles in Pressure Overload-Induced Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction and Heart Failure in Mice,” Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).