1. Introduction

Several murine models of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) have been developed in recent years, most commonly using C57Bl/6 mice. These models typically combined hypertensive stress (e.g., L-NAME, Angiotensin II, DOCA-Salt) with metabolic alterations (e.g., high-fat or Western diets). Some of these models have been studied in males, females, or both. Combining multiple stresses (or hits) better reflects the multifactorial nature of HFpEF in human patients [

1,

2,

3,

4].

One key physiological difference between humans and mice is their thermoregulatory capacity. Thermoneutrality in mice is estimated to range between 26-32°C [

5,

6,

7]. Mice are typically housed at a temperature that creates a cold-stressful environment (22-23°C). Under these conditions, mice display elevated catecholamine levels, increased energy expenditure through adaptive thermogenesis, and increased brown adipose tissue (BAT) activity [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Chronically elevated catecholamines are known contributors to the development and progression of heart failure, suggesting that cold stress could accelerate cardiac dysfunction in susceptible mouse models. A recent study using a two-hit HFpEF model revealed onset of diastolic dysfunction in mice housed at 30°C compared to 23°C. However, housing temperature was not a differentiating factor if the stress persisted [

10].

BAT activation, often triggered by cold exposure, has been proposed have cardioprotective effects through the release of endocrine factors known “batokines”. These include FGF21, neuregulin 4, 12,13-diHOME, and BAT-derived microRNAs, all of which have been implicated in modulating cardiac or vascular function in the context of cardiovascular diseases [

11].

Thus, while cold exposure activates BAT thermogenesis and batokine secretion, it also induces physiological stress that may negatively impact cardiovascular health. [

12]. However, the impact of cold exposure on HFpEF pathophysiology remains unclear.

To address this, we used a recently developed two-hit mouse model of HFpEF [

13] to study the impact of housing temperature on cardiac structure and function. Male and female C57Bl6/J mice were housed for five weeks at 10°C (cold), 22°C (room temperature), or 30°C (thermoneutrality)). Half of the animals were subjected to the MHS protocol, consisting of an Angiotensin II (AngII) continuous infusion combined with a high-fat diet for 28 days (MHS) [

13].

We report that housing mice at 10°C is associated with BAT activation, cardiac hypertrophy, left ventricular (LV) remodelling, and increased cardiac output. In MHS-treated mice, cold exposure further exacerbated diastolic dysfunction. In contrast, thermoneutral housing decreased LV mass (as assessed by echocardiography and cardiomyocyte size) and attenuated the cardiac hypertrophic response. Furthermore, the expression of pathological gene markers was less pronounced at thermoneutrality compared to cold stress conditions.

4. Discussion

Most preclinical studies in mice are performed at standard housing temperatures (~22°C), which represent a cold stress for these animals [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

17]. Cold exposure increases energy expenditure, food consumption, and locomotion, while individual housing removes opportunities for huddling-based thermoregulation, adding futher physiological stress.

Compared to thermoneutrality, cold housing activates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAAS) system. Circulating catecholamines are increased by cold exposure [

18,

19] as well as plasma renin activity and AngII formation [

20,

21]. Nitric oxide production, a central vasodilator that controls BT and endothelial function, is reduced via decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression [

22]. Evidence also exists that endothelin-1 levels, a potent vasoconstrictor, increase in response to cold exposure [

23]. These adaptations to cold will cause increased hypertension (CIH) and heart rate [189].

Since CIH can cause cardiac hypertrophy, it is plausible that inhibiting the SNS or RAAS systems would block cold-induced cardiac hypertrophy (CICH). Although cold-induced hypertension can be reduced using β-blockers or RAAS inhibitors, this did not translate into blocking CICH [

12].

Cold exposure is also associated with an increase in circulating thyroid hormone levels, which are known to activate thermogenesis [

24,

25]. Interestingly, blockade of thyroid hormones’ action has been shown to reduce CICH in rats [

26]. Since thyroid hormones are also known for their implication in the postnatal cardiac growth, a form of physiological CH [

27], it is plausible that they, in part, control the development of CICH.

More recently, it was reported that increased oxidative stress could partly modulate CICH. Blocking the expression of the gp91phox-containing NADPH oxidase (Nox2), which is selectively expressed by endothelial cells, using RNA interference, inhibited CICH in rats. This NADPH oxidase is a significant source of oxygen radical generation in the arterial wall [

28]. Endothelin-1 inhibition using RNA interference was also shown to inhibit CICH [

29]. This also emphasizes the possible roles of myocardial endothelial cells in the development of CICH.

Although some authors consider CICH as a pathological phenotype [

12,

30,

31], others view it as a physiological adaptation to this stress. Increased myocardial capillarity, lipid uptake, and reversibility after stress removal, along with enhanced metabolic capacity, indicate physiological hypertrophy [

32]. These authors identify the capacity of a reversal toward a normal phenotype as a hallmark of physiological CH, along with the absence of activation of a myocardial gene profile associated with pathological hypertrophy.

Our results show that the continuous demand for cold adaptation can stretch the animal’s capacity, especially the myocardium, to respond to a pathological stress, such as the MHS, and exacerbate the severity of the induced phenotype. A similar observation was made in mice, showing that pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy was accentuated by cold housing [

33].

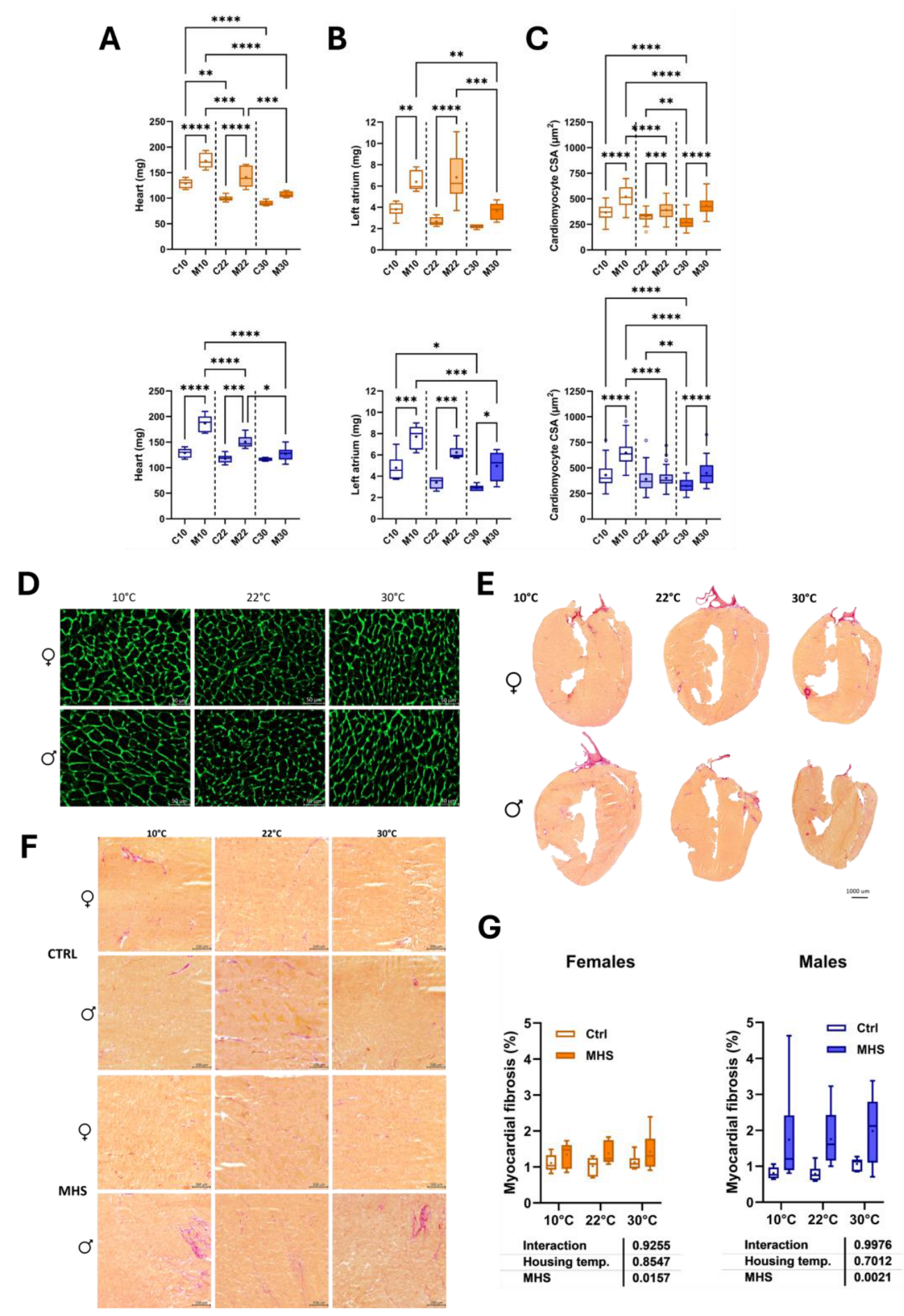

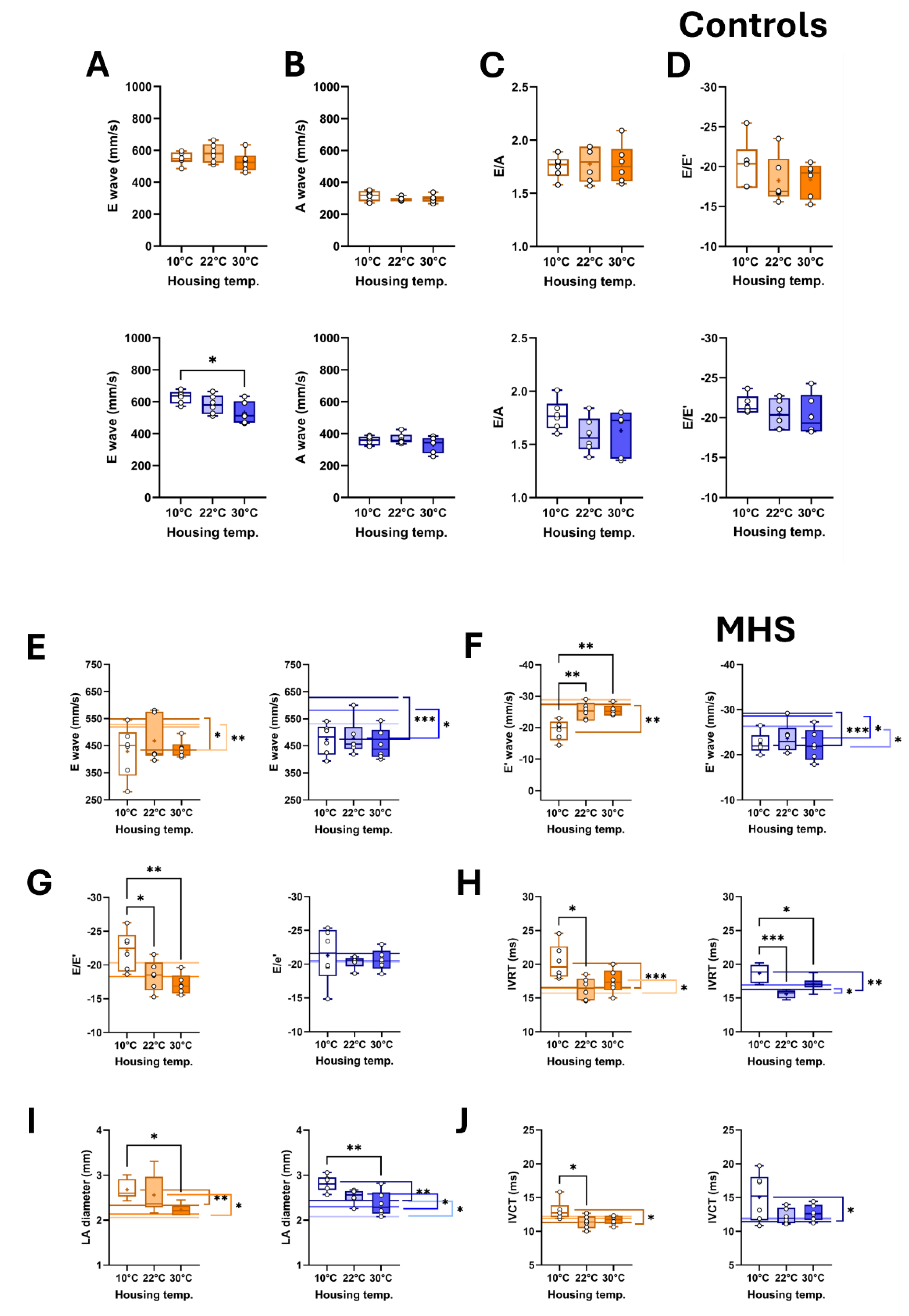

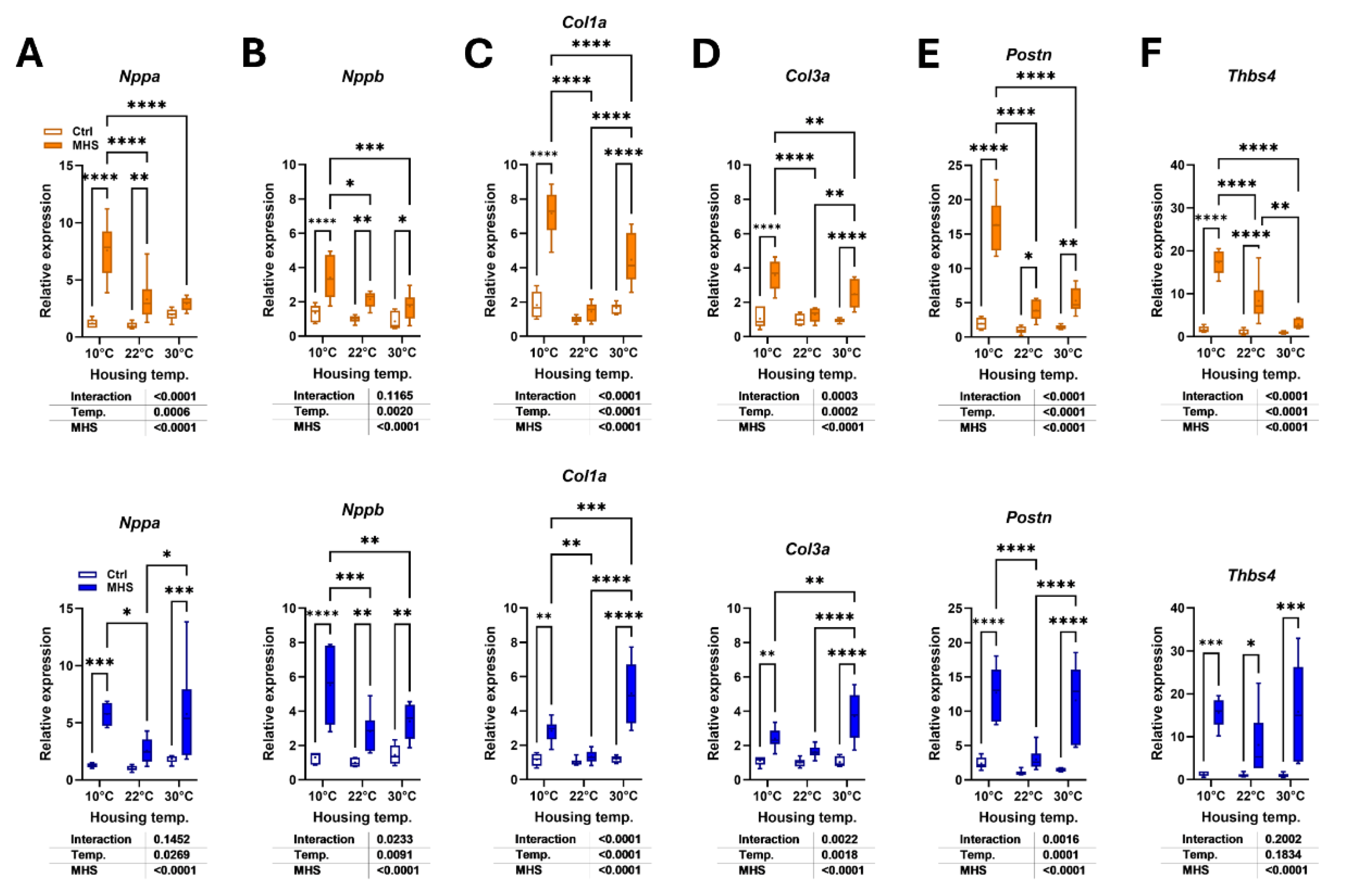

We observed that although CICH in animals housed at 10°C for five weeks was not associated with changes in the expression of the hypertrophy and fibrosis marker genes we measured, when the MHS was applied, the heart of both male and female mice showed exacerbated cardiac dysfunction compared to mice at thermoneutrality and at ambient room temperature.

This did not appear to be related to exaggerated myocardial fibrosis, as we did not observe higher levels in mice exposed to cold temperatures compared to groups housed at warmer temperatures. Other signs of a pathological phenotype related to the cold exposure include increased left atrial size and/or mass, lungs’ wet and dry weights, and dilated LV. This phenotype may only reflect a physiological volume overload induced by the need for a higher cardiac output for thermogenesis. On the other hand, the animals housed at 10°C were more susceptible to pathological stressors.

Adaptations to the cold were similar in male and female mice (increased food consumption and body fat content, dilated LV, higher cardiac output), but several differences were observed. Male mice increased their body weight, not females, and body growth (tibial length) slowed in males, not females. Cardiac adaptations to the cold were relatively similar between the sexes, however.

Housing mice at thermoneutrality provides an opportunity to assess the degree of stress that ambient housing temperatures represent for mice. Globally, for control mice, the differences between mice at 22°C and 30°C were relatively mild. Except for food consumption in mice housed at 22°C, we also observed that females had less lean mass and had an enlarged left atrium. Only food consumption was increased at ambient temperature in males.

Differences became evident when the mice were subjected to the MHS. Thermoneutral groups had a blunted hypertrophic response compared to those housed at 22°C, and left atrial enlargement was also reduced. The MHS also modulated fewer diastolic echocardiography parameters. Interestingly, these potential benefits of thermoneutrality were not observed in the expression of gene markers for hypertrophy and extracellular matrix remodeling. For instance, collagens were more expressed in the LV of MHS mice at 30°C compared to those at 22°C. Nppa and Postn were also more expressed in MHS males at thermoneutrality.

Cardiac adaptations during the acclimatization period of mice transiting from ambient room temperature to 30°C may have coincided with those induced by the MHS stress, since only one week separated the two. However, thermoneutrality helped reduce the hypertrophic response to MHS. Substantial morphological and functional changes in cardiac physiology are not induced by the cold stress of being housed at 22°C, but it may fragilize the mice exposed to the MHS.

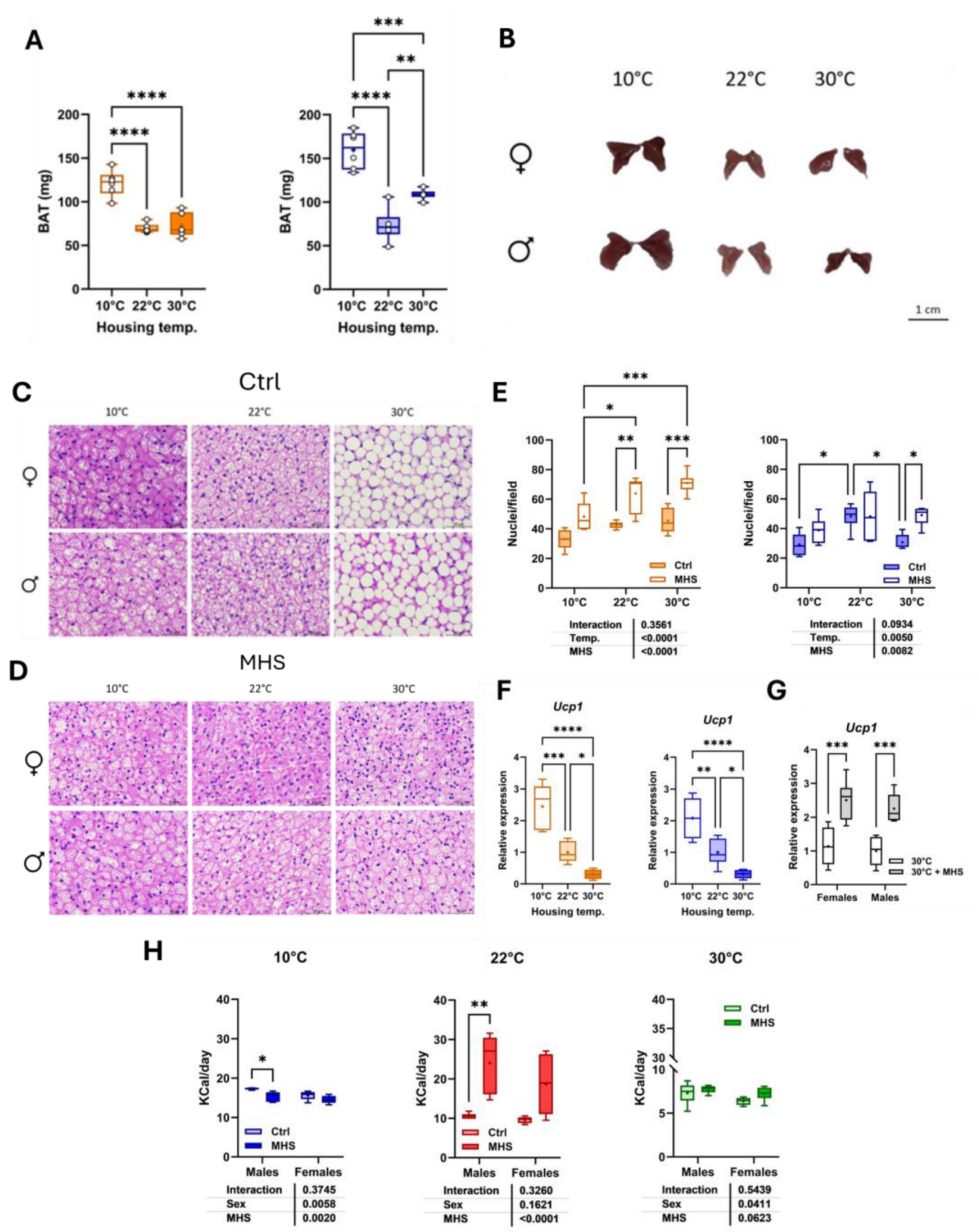

Cold exposure creates a demand for increased thermogenesis. Brown adipose tissue is an essential mammal heat producer activated by the β3-adrenergic receptor (β3-AR) in mice. The uncoupled protein 1 (UCP1) is central to this response to the cold. Cold stimuli are transmitted to the hypothalamus through the skin, indirectly releasing norepinephrine to activate the cAMP-protein kinase A (PKA) signalling pathway via the β3-AR. PKA phosphorylation activates factors that lead to the activation of PGC-1α expression. This activates intranuclear UCP1 production, which then migrates to the mitochondria to produce heat.

In addition to its role in thermogenesis, BAT has been shown to produce factors (batokines) that can protect the cardiovascular system, particularly the heart, in pathological situations. Evidence for the modulation of cardiovascular function exists in the context of pathological states, such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, and ischemia/reperfusion injury, for several of these batokines (FGF21, neuregulin 4, 12,13-diHOME, and BAT-derived microRNAs) [

11]. Activation of the β3-AR in BAT has been shown to exhibit cardioprotective effects by suppressing exosomal inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) originating from the BAT [

34].

As we observed here, the BAT in mice at thermoneutrality presents histological similarities with white adipose tissue, whereas browning is evident at 22°C and 10°C. This is accompanied by increased Ucp1 mRNA levels, which are more elevated as the cold stress is more intense.

The activation of the BAT by cold exposure may help produce cardioprotective factors or inhibit others, such as iNOS [

11,

34]. These putative benefits of BAT activation were entirely superseded by the heart’s obligatory response to increase its cardiac output in a cold environment. Those factors did not protect the heart against the MTS in the cold-stressed groups, although they may have helped limit the adverse response to low temperatures. It would be interesting to investigate the action of pharmaceutical agonists or antagonists of β3-AR to modulate this signalling pathway and test if BAT activation without a cold stress could benefit the response to MHS. For instance, Lin and colleagues observed that mirabegron, a β3-AR agonist, could activate the BAT and inhibit the release of exosomal iNOS in the Ang II mouse cardiac hypertrophy model [

34].

Interestingly, the main effect of thermoneutrality was to inhibit cardiac hypertrophy after the MHS. Several factors may contribute to this observation. Food consumption was reduced in mice housed at 30°C, resulting in fewer calories from fat being consumed. In our model, the HFD does not cause cardiac hypertrophy in males, but does in females. Only in mice housed at 22°C did we observe an increase in calories consumed in mice fed the HFD.

As previously described by Chen and collaborators [

35], housing mice at thermoneutrality reduces blood pressure (BP), but this reduction could be reversed by feeding mice with an HFD. They also test a pressure overload stress in their mice by performing a transverse aortic constriction (TAC). A significant increase in the indexed heart weight was noted in TAC mice at 22°C or thermoneutrality; however, CH tended to be less in the thermoneutral mice.

AngII is the primary hypertrophic stress in our model [

13], and its effects were almost completely blunted in mice under thermoneutral conditions. We did not record BP in this study. Still, AngII infusion alone or in the MHS was associated with significantly increased mean BP in males, and less in females [

13]. The cardiac hypertrophy induced by AngII was equivalent between the sexes, regardless of BP. It is thus possible that BP was lower in the MHS mice at 30°C, although feeding with the HFD should have partially counteracted the benefits of thermoneutrality on BP. This needs to be explored further, but apart from cardiac hypertrophy, the benefits of housing at thermoneutrality compared to standard room temperature were relatively mild in our mice.

The MHS induced browning of the BAT in mice at thermoneutrality, accompanied by elevated

Ucp1 gene expression and decreased adipocyte size, suggesting the activation of this fat depot. The MHS combines two factors with potential opposite effects on general adiposity. We previously observed that the HFD for four weeks increased body weight in mice compared to a standard diet, and AngII did the opposite in males. Females’ body weight remained unchanged after AngII. Combining the two, as for the MHS, resulted in similar body weights after four weeks in animals at 22 °C [

13].

The control of adiposity by the RAAS is believed to be mediated by the Angiotensin II receptor type II (AT2R). The knock-out of this receptor results in increased obesity in mice fed an HFD, and its activation with a specific agonist (C21) blunts weight gain [

36,

37,

38].

C21 can also lead to BAT activation (upregulation of

Ucp1) and the browning of white adipose tissue in mice [

38]. In our animals at thermoneutrality, it seems that the effects of AngII on the BAT were preponderant. It is unclear how it altered batokines production in our mice, which may have contributed to the reduction of CH in the MHS mice.

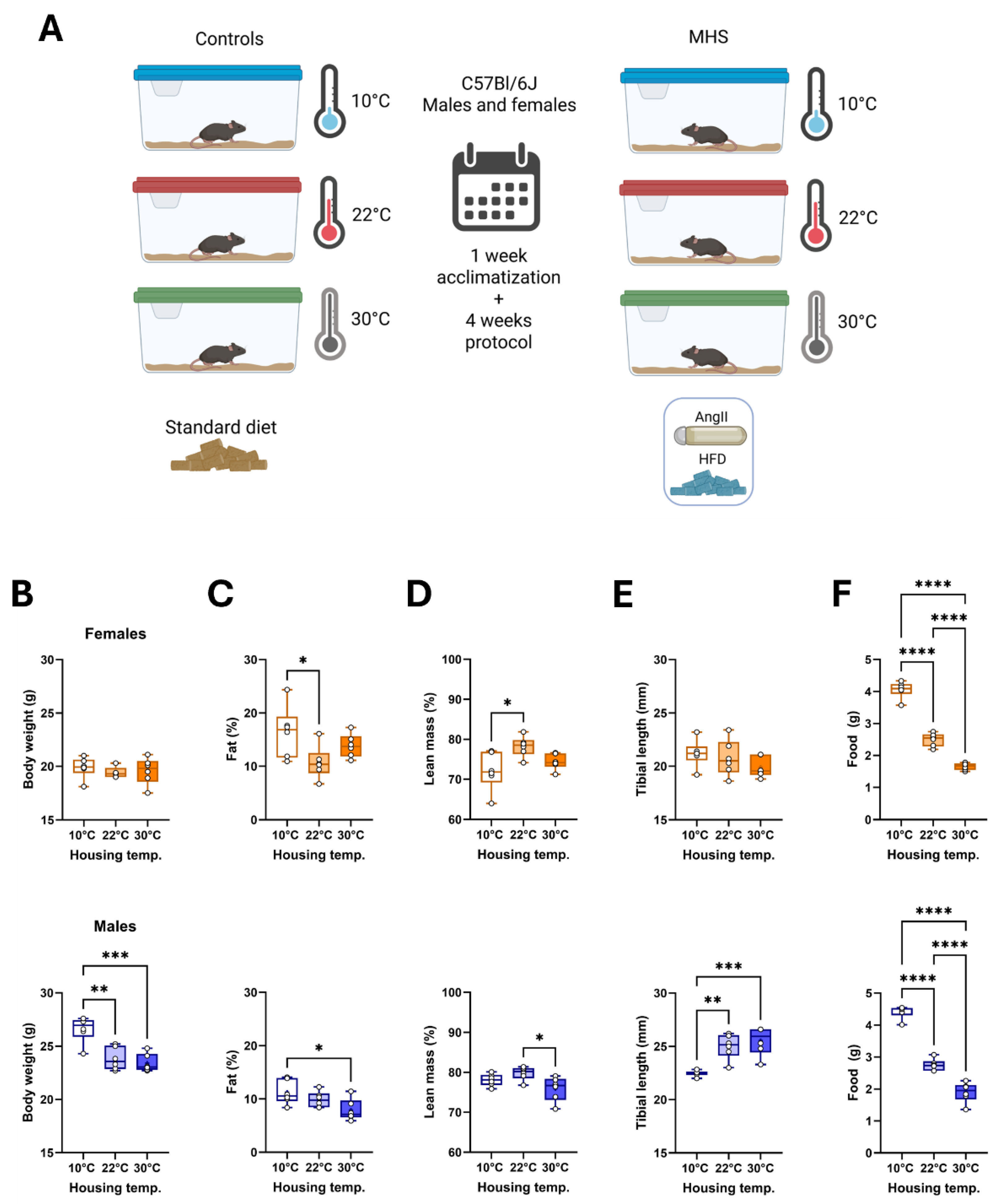

Figure 1.

Effects of three different housing temperatures (10°C, 22°C or 30°C) on mouse body composition and food consumption. A. Schematic representation of the experimental design (Created in BioRender. Couet, J. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/r27xz47). Eight-week-old C57BL/6J male and female mice were housed individually for 5 weeks (1 week of acclimatization and 4 weeks for the protocol). All mice were fed a standard diet described in the Materials and Methods section. After one week, the MHS was started in half of the mice for four weeks. B. Body weight, C. Body fat (%), D. Lean mass (%), E. Tibial length and F. Daily food consumption. Graphs of females (top, orange) and males (bottom, blue). Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups (n=6 mice/group).

Figure 1.

Effects of three different housing temperatures (10°C, 22°C or 30°C) on mouse body composition and food consumption. A. Schematic representation of the experimental design (Created in BioRender. Couet, J. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/r27xz47). Eight-week-old C57BL/6J male and female mice were housed individually for 5 weeks (1 week of acclimatization and 4 weeks for the protocol). All mice were fed a standard diet described in the Materials and Methods section. After one week, the MHS was started in half of the mice for four weeks. B. Body weight, C. Body fat (%), D. Lean mass (%), E. Tibial length and F. Daily food consumption. Graphs of females (top, orange) and males (bottom, blue). Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups (n=6 mice/group).

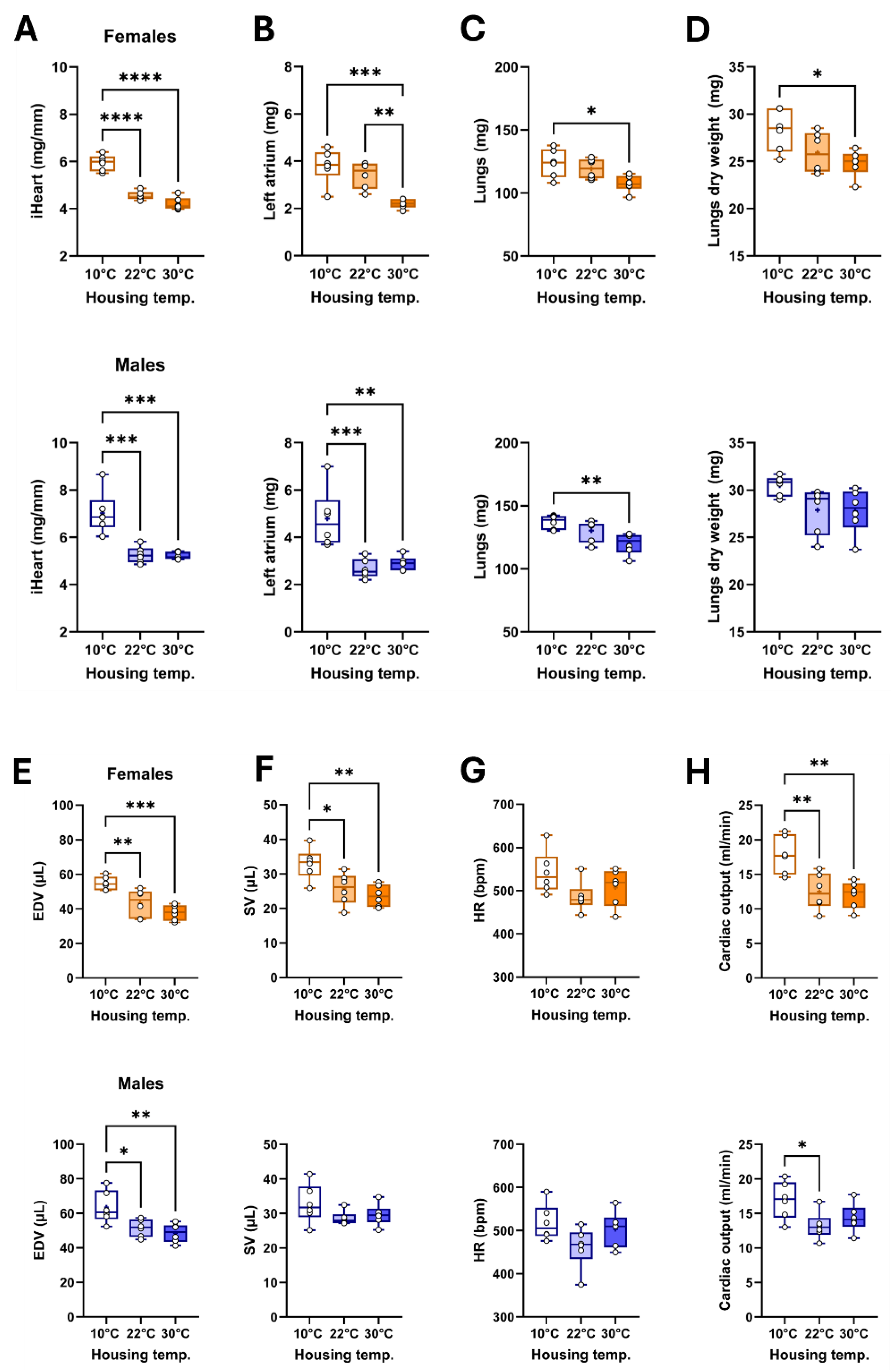

Figure 2.

Effects of three different housing temperatures (10°C, 22°C or 30°C) on mouse cardiac morphology and function. A. Indexed heart weight for the tibial length, B. left atrial weight, C. Lungs wet weight, D. Lungs dry weight, E. End-diastolic volume (EDV), F. LV stroke volume (SV), G. Heart rate (HR) and H. Cardiac output. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001, and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups (n=6 mice/group).

Figure 2.

Effects of three different housing temperatures (10°C, 22°C or 30°C) on mouse cardiac morphology and function. A. Indexed heart weight for the tibial length, B. left atrial weight, C. Lungs wet weight, D. Lungs dry weight, E. End-diastolic volume (EDV), F. LV stroke volume (SV), G. Heart rate (HR) and H. Cardiac output. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001, and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups (n=6 mice/group).

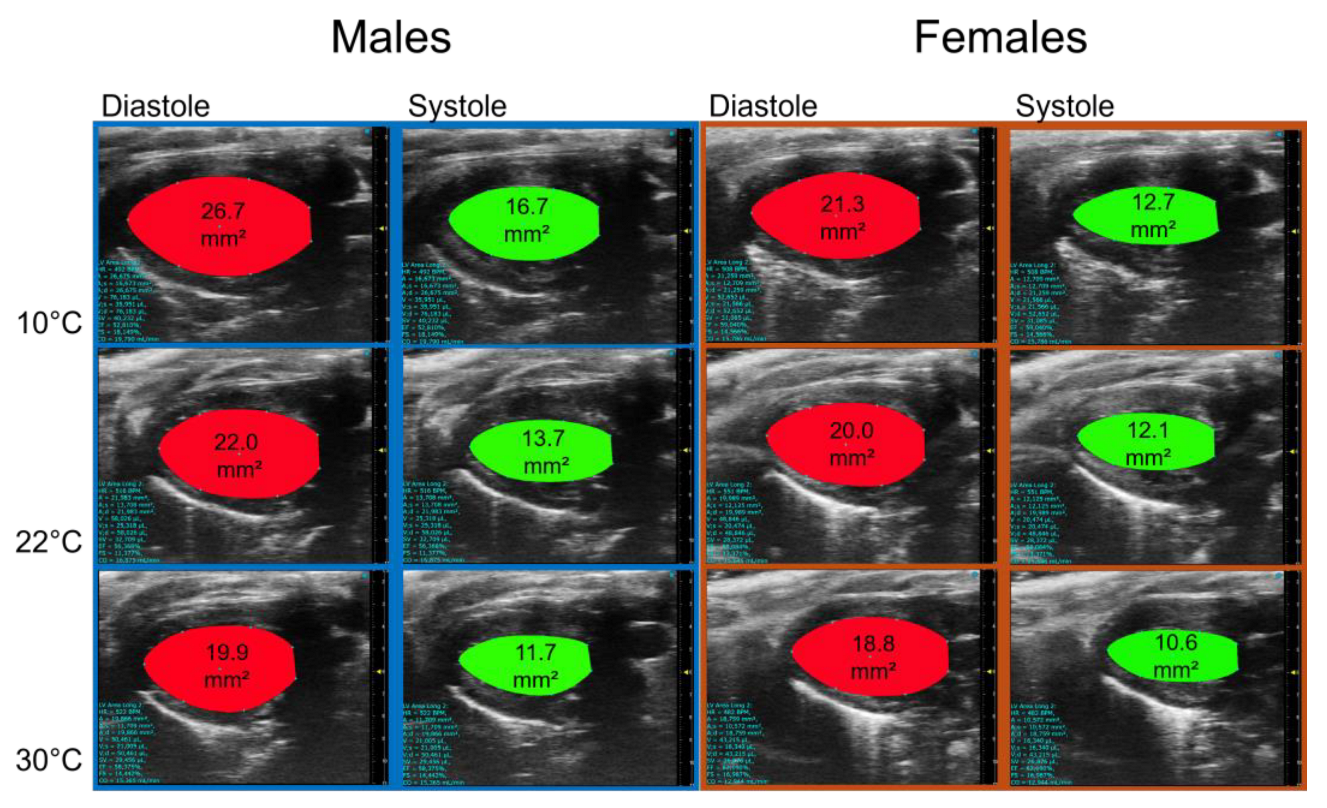

Figure 3.

Representative B-mode LV diastolic and systolic tracings of mice 5 weeks after being housed at 10°C, 22°C or 30°C.

Figure 3.

Representative B-mode LV diastolic and systolic tracings of mice 5 weeks after being housed at 10°C, 22°C or 30°C.

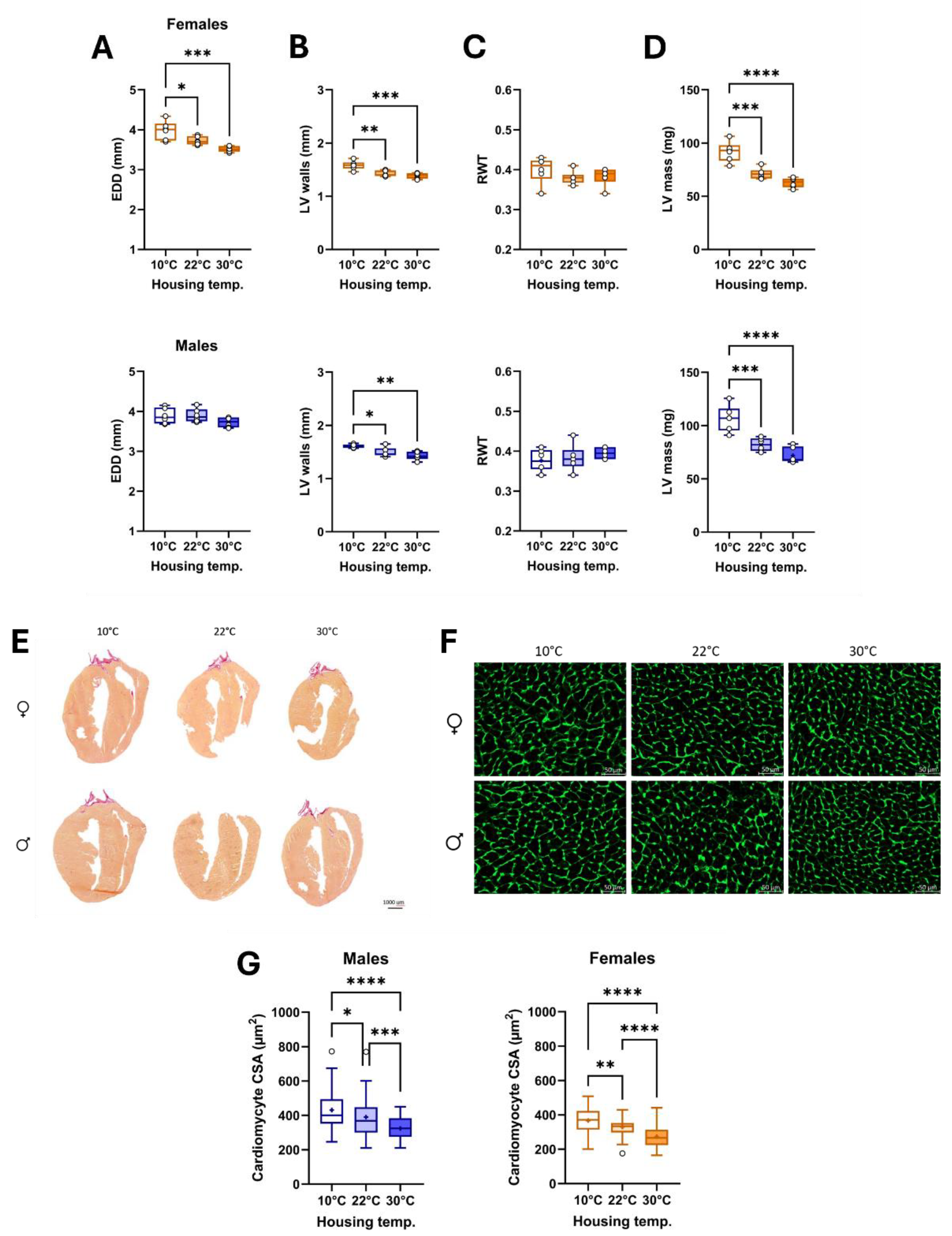

Figure 4.

Effects of three different housing temperatures (10°C, 22°C or 30°C) on LV dimensions and cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area (CSA). A. End-diastolic diameter (EDD), B. LV walls (posterior + septal) thickness, C. Relative wall thickness (RWT), D. LV mass. E. Representative images of picrosirius red staining of female and male heart sections, F. Representative images of WGA-FITC staining from LV sections of the various indicated groups. And G. CSA of cardiomyocytes was quantified by WGA-FITC staining. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups (n=6 mice/group).

Figure 4.

Effects of three different housing temperatures (10°C, 22°C or 30°C) on LV dimensions and cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area (CSA). A. End-diastolic diameter (EDD), B. LV walls (posterior + septal) thickness, C. Relative wall thickness (RWT), D. LV mass. E. Representative images of picrosirius red staining of female and male heart sections, F. Representative images of WGA-FITC staining from LV sections of the various indicated groups. And G. CSA of cardiomyocytes was quantified by WGA-FITC staining. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups (n=6 mice/group).

Figure 5.

Effects of MHS (M) on mice housed at three different temperatures (10°C, 22°C or 30°C) on cardiac morphology and cardiomyocyte area compared to controls (C). A. Heart weight, B. Left atrial weight, C. Cross-sectional area, D. Cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes stained with WGA-FITC, E. Representative images of picrosirius red staining of MHS female and male heart sections, F. Magnification of a mid-posterior wall section of control and MHS LV sections. Bar scale: 200 µm. G. Myocardial fibrosis (picrosirius red staining). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups (n=6 mice/group).

Figure 5.

Effects of MHS (M) on mice housed at three different temperatures (10°C, 22°C or 30°C) on cardiac morphology and cardiomyocyte area compared to controls (C). A. Heart weight, B. Left atrial weight, C. Cross-sectional area, D. Cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes stained with WGA-FITC, E. Representative images of picrosirius red staining of MHS female and male heart sections, F. Magnification of a mid-posterior wall section of control and MHS LV sections. Bar scale: 200 µm. G. Myocardial fibrosis (picrosirius red staining). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups (n=6 mice/group).

Figure 6.

Effects of MHS (M) on diastolic function echocardiography parameter in mice housed at three different temperatures (10°C, 22°C or 30°C). Controls. A. E wave velocity, B. A wave velocity, C. E/A ratio and D. E/E’ ratio. MHS. E. E wave velocity, F. E’ wave velocity, G. E/E’ ratio, H. Isovolumetric relaxation time (IVRT), I. LA diameter and J. Isovolumetric contraction time (IVCT). Lines in Graphs E to J represent the average value of this parameter in control mice. Darker to light colours: 10°, 22° and 30°C, respectively. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM—one-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. Comparisons to controls were analyzed using T-tests. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups (n=6 mice/group).

Figure 6.

Effects of MHS (M) on diastolic function echocardiography parameter in mice housed at three different temperatures (10°C, 22°C or 30°C). Controls. A. E wave velocity, B. A wave velocity, C. E/A ratio and D. E/E’ ratio. MHS. E. E wave velocity, F. E’ wave velocity, G. E/E’ ratio, H. Isovolumetric relaxation time (IVRT), I. LA diameter and J. Isovolumetric contraction time (IVCT). Lines in Graphs E to J represent the average value of this parameter in control mice. Darker to light colours: 10°, 22° and 30°C, respectively. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM—one-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. Comparisons to controls were analyzed using T-tests. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups (n=6 mice/group).

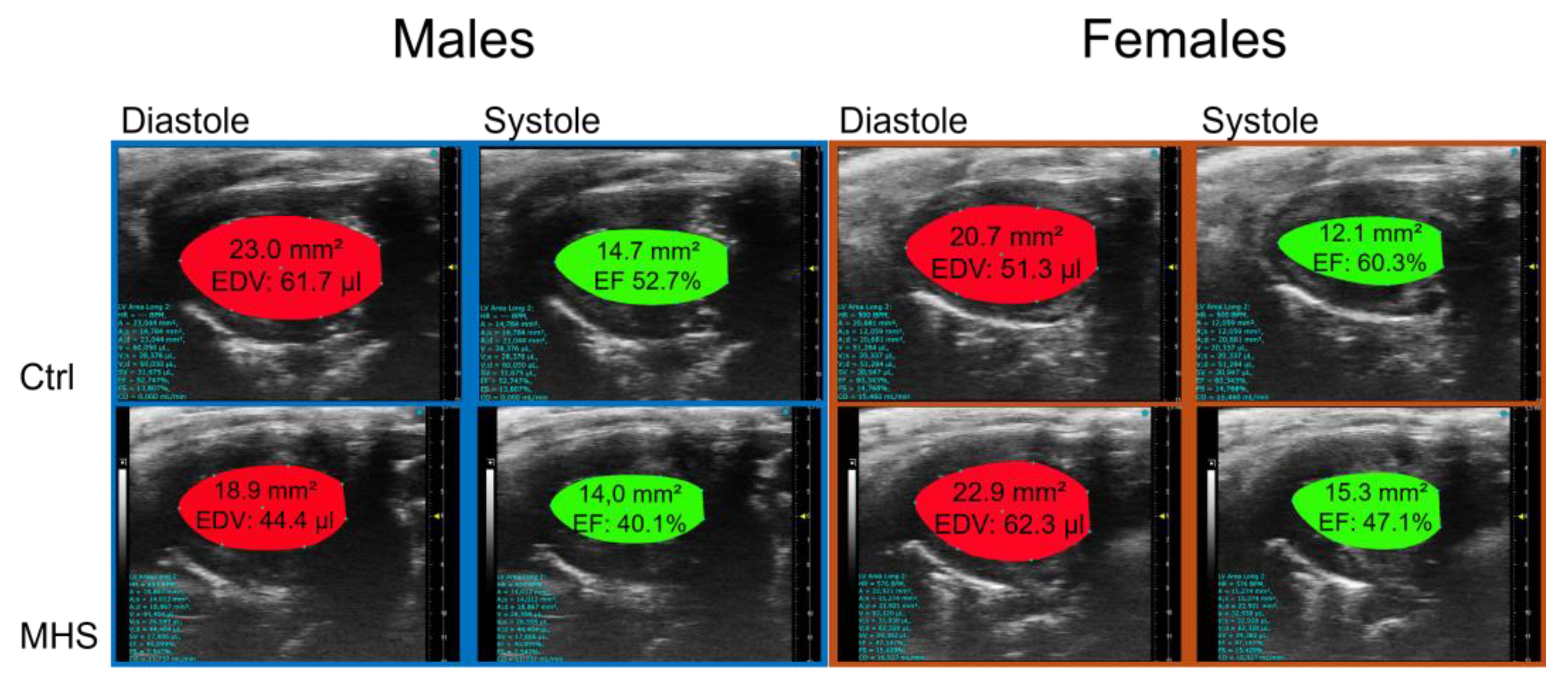

Figure 7.

Representative B-mode LV diastolic and systolic tracings of control (Ctrl) and MHS housed at 10°C.

Figure 7.

Representative B-mode LV diastolic and systolic tracings of control (Ctrl) and MHS housed at 10°C.

Figure 8.

Modulation of LV gene expression after MHS in mice housed at three different temperatures. A. Nppa, atrial natriuretic peptide. B. Nppb, brain natriuretic peptide. C. Col1a1, Collagen 1α1, D. Col3a1, Collagen 3α1, E. Postn, periostin and F. Tbsp4, thrombospondin 4. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=6 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 8.

Modulation of LV gene expression after MHS in mice housed at three different temperatures. A. Nppa, atrial natriuretic peptide. B. Nppb, brain natriuretic peptide. C. Col1a1, Collagen 1α1, D. Col3a1, Collagen 3α1, E. Postn, periostin and F. Tbsp4, thrombospondin 4. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=6 per group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 9.

Effects of housing temperature and MHS on brown adipose morphology. A. Scapular brown fat depot weight (BAT). B. Representative pictures of BAT depots for each control group. C. Hematoxylin/eosin staining of the BAT section from a mouse in each control group. D. Hematoxylin/eosin staining of BAT section from a mouse of each MHS group, E. Number of nuclei/field, F. Ucp1 or Uncoupled protein 1 gene expression in the BAT of control mice, G. BAT Ucp1 expression in mice at 30°C after the MHS. H. Average daily food consumption (KCalories per day; Kcal/day) for each mouse group. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=6 per group). One- or Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Figure 9.

Effects of housing temperature and MHS on brown adipose morphology. A. Scapular brown fat depot weight (BAT). B. Representative pictures of BAT depots for each control group. C. Hematoxylin/eosin staining of the BAT section from a mouse in each control group. D. Hematoxylin/eosin staining of BAT section from a mouse of each MHS group, E. Number of nuclei/field, F. Ucp1 or Uncoupled protein 1 gene expression in the BAT of control mice, G. BAT Ucp1 expression in mice at 30°C after the MHS. H. Average daily food consumption (KCalories per day; Kcal/day) for each mouse group. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n=6 per group). One- or Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test. *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 and ****: p<0.0001 between indicated groups.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used in this study.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used in this study.

| Symbol |

Description |

Forward sequence

Reverse sequence |

| Col1a1 |

Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Chain |

5’-CAT TGT GTA TGC AGC TGA CTT C-3’

5’CGC AAA CAC TCT ACA TGT CTA GG-3’ |

| Col3a1 |

Collagen Type III Alpha 1 Chain |

5’-TCT CTA GAC TCA TAG GAC TGA CC-3’

5’ TTC TTC TCA CCC TTC TTC ATC C-3’ |

| Nppa |

Natriuretic Peptide B |

5’-CTC CTT GGC TGT TAT CTT CGG-3’

5’-GGG TAG GAT TGA CAG GAT TGG-3’ |

| Nppb |

Natriuretic Peptide A |

5’-AGG TGA CAC ATA TCT CAA GCT G-3’

5’-CTT CCT ACA ACA TCA GTG C-3’ |

| Ppia |

Cyclophilin A |

5’-TTC ACC TTC CCA AAG ACC AC-3’

5’-CAA ACA CAA ACG GTT CCC AG-3’ |

| Postn |

Periostin |

5’-GCT TTC GAG AAA CTG CCA CG-3’

5’-ATG GTC TCA AAC ACG GCT CC-3’ |

| Thbs4 |

Thrombospondin 4 |

5’-GAT ACT GAC GGG GAT GGG AG-3’

5’-CGT CAC TGT CTT GGT TGG TG-3’ |

| Ucp1 |

Uncoupled protein 1 |

5’-GCT TCT ACG ACT CAG TCC AA-3’

5’-CTC TGG GCT TGC ATT CTG AC-3’ |

Table 2.

Echo data in male and female mice after MHS (M) at three different housing temperatures (10°C, 22°C and 30°C). Controls (C). Standard echo left ventricle parameters after 4 weeks of MHS and after 4 weeks. Control mice were studied in parallel Echo exams as described in the Methods section. PWd: diastolic posterior wall thickness, IVSd: diastolic interventricular septum, EDD: end-diastolic LV diameter, ESD: end-systolic LV diameter, RWT: relative wall thickness, EDV: end-diastolic volume, ESV: end-systolic volume, SV: stroke volume, HR: heart rate, EF: ejection fraction, CO: cardiac output. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. P values were calculated using Student’s T-test. a: p<0.05 vs controls, b: p<0.01, c: p<0.001 and d: p<0.0001.

Table 2.

Echo data in male and female mice after MHS (M) at three different housing temperatures (10°C, 22°C and 30°C). Controls (C). Standard echo left ventricle parameters after 4 weeks of MHS and after 4 weeks. Control mice were studied in parallel Echo exams as described in the Methods section. PWd: diastolic posterior wall thickness, IVSd: diastolic interventricular septum, EDD: end-diastolic LV diameter, ESD: end-systolic LV diameter, RWT: relative wall thickness, EDV: end-diastolic volume, ESV: end-systolic volume, SV: stroke volume, HR: heart rate, EF: ejection fraction, CO: cardiac output. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. P values were calculated using Student’s T-test. a: p<0.05 vs controls, b: p<0.01, c: p<0.001 and d: p<0.0001.

| Males |

|

| Parameters |

C10 (n=6) |

M10 (n=6) |

C22(n=6) |

M22(n=6) |

C30(n=6) |

M30(n=6) |

| PWd, mm |

0.85±0.012 |

1.11±0.035d |

0.78±0.017 |

1.05±0.032d |

0.76±0.011 |

1.10±0.038d |

| IVSd, mm |

0.76±0.010 |

0.93±0.024d |

0.71±0.017 |

0.94±0.043c |

0.67±0.019 |

0.89±0.027d |

| EDD, mm |

4.29±0.101 |

4.12±0.142 |

3.90±0.057 |

3.54±0.092b |

3.73±0.045 |

3.22±0.091c |

| ESD, mm |

3.25±0.104 |

3.18±0.128 |

2.93±0.088 |

2.42±0.116b |

2.57±0.051 |

2.09±0.102b |

| RWT |

0.38±0.009 |

0.50±0.031b |

0.38±0.012 |

0.57±0.032c |

0.38±0.008 |

0.62±0.023d |

| LV mass, mg |

133±5.2 |

171±3.8d |

103±2.6 |

132±5.0c |

90±3.1 |

115±8.7a |

| EDV, µl |

63±3.2 |

53±2.6a |

51±1.7 |

39±2.5b |

49±1.9 |

37±2.5b |

| ESV, µl |

31±1.9 |

29±1.6 |

23±1.4 |

17±2.0b |

19±1.3 |

14±1.7a |

| SV, mm |

32±1.9 |

24±1.8b |

29±0.7 |

22±1.3c |

30±1.1 |

23±1.1b |

| HR, bpm |

518±14.5 |

579±13.0 |

461±16.4 |

495±4.5 |

503±14.1 |

532±13.3 |

| EF, % |

52±1.8 |

44±1.8a |

56±1.6 |

58±1.1 |

62±1.6 |

63±1.4 |

| CO, ml/min |

16.9±0.93 |

13.7±0.94a |

13.9±0.69 |

9.8±0.75a |

14.4±0.71 |

12.4±0.54 |

Females

|

|

| Parameters |

C10 (n=6) |

M10 (n=6) |

C22(n=6) |

M22(n=6) |

C30(n=6) |

M30(n=6) |

| PWd, mm |

0.85±0.017 |

1.11±0.043c |

0.72±0.009 |

0.96±0.034d |

0.72±0.009 |

0.89±0.018d |

| IVSd, mm |

0.73±0.097 |

0.96±0.037c |

0.70±0.011 |

0.87±0.034c |

0.67±0.011 |

0.88±0.030d |

| EDD, mm |

3.98±0.020 |

3.89±0.067 |

3.73±0.037 |

3.75±0.148 |

3.51±0.025 |

3.27±0.050b |

| ESD, mm |

2.88±0.098 |

3.02±0.090 |

2.67±0.054 |

2.67±0.054 |

2.30±0.030 |

2.15±0.044b |

| RWT |

0.40±0.014 |

0.53±0.024c |

0.38±0.006 |

0.50±0.034 |

0.40±0.004 |

0.54±0.015d |

| LV mass, mg |

115±4.8 |

161±8.8b |

89±2.2 |

127±3.9d |

78±2.0 |

98±4.1b |

| EDV, µl |

55±1.6 |

52±2.4 |

43±2.7 |

50±3.3 |

38±1.5 |

34±2.25 |

| ESV, µl |

22±0.8 |

27±1.1b |

18±1.3 |

24±2.0a |

14±0.8 |

12±1.3 |

| SV, mm |

33±1.9 |

26±1.9a |

26±1.6 |

26±1.8 |

24±1.1 |

21±1.1 |

| HR, bpm |

542±20.1 |

531±15.3 |

486±12.1 |

515±11.5 |

508±14.8 |

513±8.4 |

| EF, % |

60±2.0 |

49±3.2a |

59±1.3 |

59±1.1 |

63±1.4 |

64±2.0 |

| CO, ml/min |

17.8±1.12 |

13.7±1.09a |

12.5±0.90 |

13.6±0.96 |

12.0±0.67 |

11.0±0.66 |