Submitted:

26 September 2025

Posted:

28 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Mirabegron, a β3-Adrenergic Receptor Agonist, Has Sex-Specific Effects on Body and Cardiac Growth in Young C57BL/6 Mice

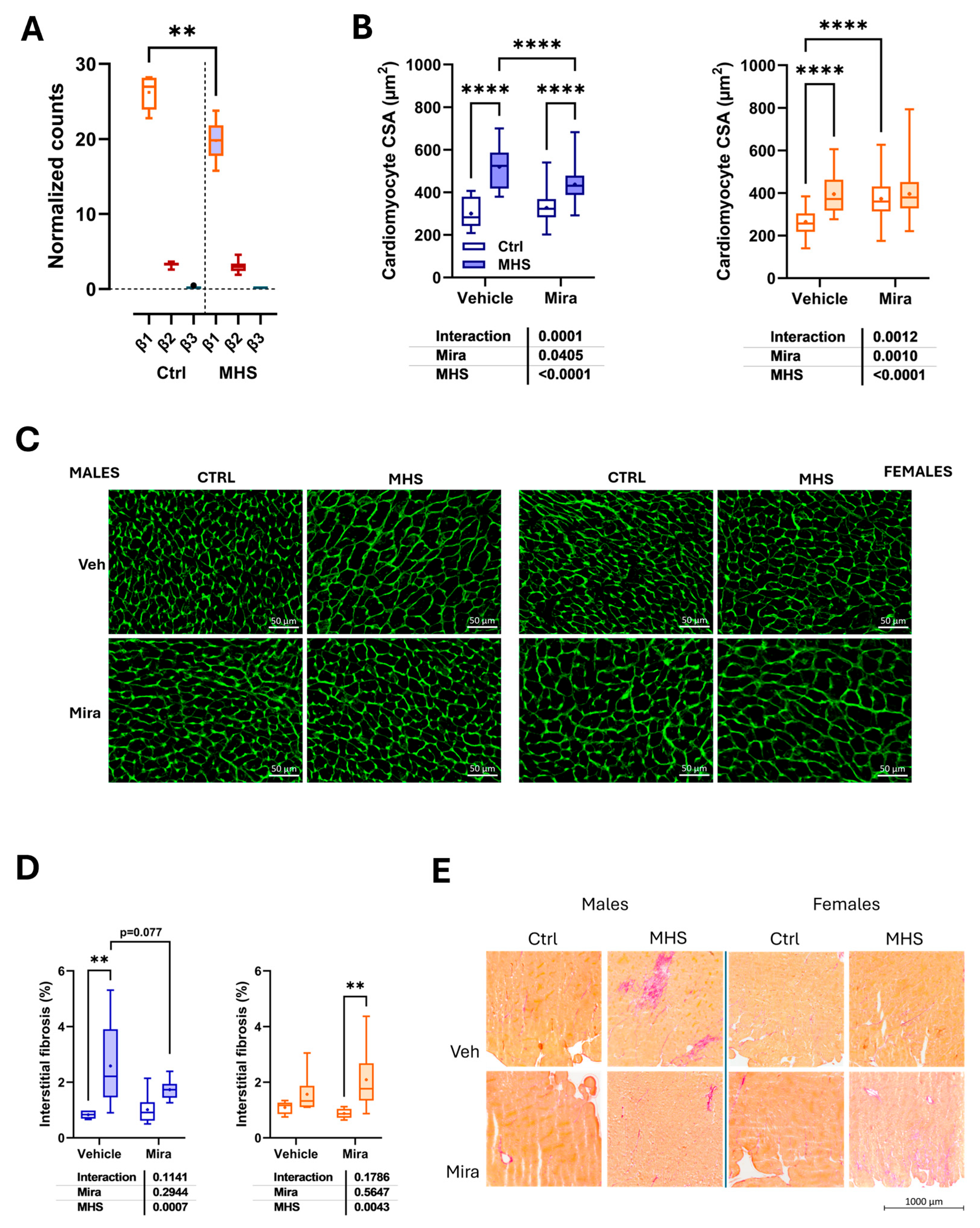

3.2. Mirabegron Effects on Cardiomyocyte and Extracellular Matrix Remodelling After MHS

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Abbreviations

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| AngII | Angiotensin II |

| MHS | Metabolic and hypertensive stress (AngII + HFD) |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| LA | Left atrial or left atrium |

| LV | Left ventricle |

| CH | Cardiac hypertrophy |

| EF | Ejection fraction |

| UCP1 | Uncoupled protein 1 |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EDD | End-diastolic diameter |

| ESD | End-systolic diameter |

| RWT | Relative wall thickness |

| SV | Stroke volume |

| CO | Cardiac output |

| BW | Body weight |

| CSA | Cross-sectional area |

| L-NAME | L-NG-Nitroarginine Methyl Ester |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| EDV | End-diastolic volume |

| ESV | End-systolic volume |

| Nppa | Atrial natriuretic peptide |

| Nppb | Brain natriuretic peptide |

| Col1a | Pro-collagen1 alpha |

| Col3a | Pro-collagen3 alpha |

| Postn | Periostin |

| Thbs4 | Thrombospondin 4 |

| PW | Posterior wall |

| IVSW | Interventricular septal wall |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| RWT | Relative LV wall thickness |

| Ppia | Cyclophilin A |

| RPL13 | L13 ribosomal protein |

| iNOS | Nitric oxide synthase, inducible |

| EF | Ejection fraction |

| β3-AR | Adrenergic receptor, beta 3 |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| RAAS | Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system |

| SNS | Sympathetic nervous system |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| AngII | Angiotensin II |

| MHS | Metabolic and hypertensive stress (AngII + HFD) |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| LA | Left atrial or left atrium |

| LV | Left ventricle |

| CH | Cardiac hypertrophy |

| EF | Ejection fraction |

| UCP1 | Uncoupled protein 1 |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EDD | End-diastolic diameter |

| ESD | End-systolic diameter |

| RWT | Relative wall thickness |

| SV | Stroke volume |

| CO | Cardiac output |

| BW | Body weight |

| CSA | Cross-sectional area |

| L-NAME | L-NG-Nitroarginine Methyl Ester |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| EDV | End-diastolic volume |

| ESV | End-systolic volume |

| Nppa | Atrial natriuretic peptide |

| Nppb | Brain natriuretic peptide |

| Col1a | Pro-collagen1 alpha |

| Col3a | Pro-collagen3 alpha |

| Postn | Periostin |

| Thbs4 | Thrombospondin 4 |

| PW | Posterior wall |

| IVSW | Interventricular septal wall |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| RWT | Relative LV wall thickness |

| Ppia | Cyclophilin A |

| RPL13 | L13 ribosomal protein |

| iNOS | Nitric oxide synthase, inducible |

| EF | Ejection fraction |

| β3-AR | Adrenergic receptor, beta 3 |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| RAAS | Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system |

| SNS | Sympathetic nervous system |

References

- Borlaug BA, Sharma K, Shah SJ, Ho JE. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: JACC Scientific Statement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023, 81, 1810–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, Seferovic P, Rosano GMC, Coats AJS, Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 3272–3287.

- Schiattarella GG, Altamirano F, Tong D, French KM, Villalobos E, Kim SY, Luo X, Jiang N, May HI, Wang ZV, Hill TM, Mammen PPA, Huang J, Lee DI, Hahn VS, Sharma K, Kass DA, Lavandero S, Gillette TG, Hill JA. Nitrosative stress drives heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature. 2019, 568, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith AN, Altara R, Amin G, Habeichi NJ, Thomas DG, Jun S, Kaplan A, Booz GW, Zouein FA. Genomic, Proteomic, and Metabolic Comparisons of Small Animal Models of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Tale of Mice, Rats, and Cats. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e026071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Withaar C, Lam CSP, Schiattarella GG, de Boer RA, Meems LMG. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in humans and mice: embracing clinical complexity in mouse models. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 4420–4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasińska-Stroschein, M. Searching for Effective Treatments in HFpEF: Implications for Modeling the Disease in Rodents. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao S, Liu XP, Li TT, Chen L, Feng YP, Wang YK, Yin YJ, Little PJ, Wu XQ, Xu SW, Jiang XD. Animal models of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF): from metabolic pathobiology to drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2024, 45, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidara ML, Walsh-Wilkinson É, Thibodeau SÈ, Labbé EA, Morin-Grandmont A, Gagnon G, Boudreau DK, Arsenault M, Bossé Y, Couët J. Cardiac reverse remodelling in a mouse model with many phenotypical features of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: effects of modifying lifestyle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2024, 326, H1017–H1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teou DC, Labbé EA, Thibodeau SÈ, Walsh-Wilkinson É, Morin-Grandmont A, Trudeau AS, Arsenault M, Couet J. The Loss of Gonadal Hormones Has a Different Impact on Aging Female and Male Mice Submitted to Heart Failure-Inducing Metabolic Hypertensive Stress. Cells 2025, 14, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau SÈ, Labbé EA, Walsh-Wilkinson É, Morin-Grandmont A, Arsenault M, Couet J. Plasma and Myocardial miRNomes Similarities and Differences during Cardiac Remodelling and Reverse Remodelling in a Murine Model of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau SÈ. , Legros ML., Labbé EA, Walsh-Wilkinson É, Morin-Grandmont A, Beji S, Arsenault M, Caron A, & Couet J. Cold Exposure Exacerbates Cardiac Dysfunction in a Model of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in Male and Female C57Bl/6J Mice. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran HH, Thu A, Fuertes A, Gonzalez M, Twayana AR, Basta M, James M, Mahadevaiah A, Mehta KA, Islek D, Weissman S, Frishman WH, Aronow WS. Mirabegron for Cardiac Disease: A New Therapeutic Frontier. Cardiol Rev. [CrossRef]

- Michel LYM, Farah C, Balligand JL. The Beta3 Adrenergic Receptor in Healthy and Pathological Cardiovascular Tissues. Cells. 2020, 9, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin JR, Ding LL, Xu L, Huang J, Zhang ZB, Chen XH, Cheng YW, Ruan CC, Gao PJ. Brown Adipocyte ADRB3 Mediates Cardioprotection via Suppressing Exosomal iNOS. Circ Res. 2022, 131, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang ZB, Cheng YW, Xu L, Li JQ, Pan X, Zhu M, Chen XH, Sun AJ, Lin JR, Gao PJ. Activation of β3-adrenergic receptor by mirabegron prevents aortic dissection/aneurysm by promoting lymphangiogenesis in perivascular adipose tissue. Cardiovasc Res. 2024, 120, 2307–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh-Wilkinson É, Aidara ML, Morin-Grandmont A, Thibodeau SÈ, Gagnon J, Genest M, Arsenault M, Couet J. Age and sex hormones modulate left ventricle regional response to angiotensin II in male and female mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022, 323, H643–H658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labbé EA, Thibodeau SÈ, Walsh-Wilkinson É, Chalifour M, Sirois PO, Leblanc J, Morin-Grandmont A, Arsenault M, Couet J. Relative contribution of correcting the diet and voluntary exercise to myocardial recovery in a two-hit murine model of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2025, 329, H51–H68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Lay S, Scherer PE. Exploring adipose tissue-derived extracellular vesicles in inter-organ crosstalk: Implications for metabolic regulation and adipose tissue function. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao S, Kusminski CM, Scherer PE. Adiponectin, Leptin and Cardiovascular Disorders. Circ Res. 2021, 128, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod K, Datta V, Fuller S. Adipokines as Cardioprotective Factors: BAT Steps Up to the Plate. Biomedicines. 2025, 13, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroya F, Cereijo R, Villarroya J, Giralt M. Brown adipose tissue as a secretory organ. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlin BS, Memetimin H, Confides AL, Kasza I, Zhu B, Vekaria HJ, Harfmann B, Jones KA, Johnson ZR, Westgate PM, Alexander CM, Sullivan PG, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Kern PA. Human adipose beiging in response to cold and mirabegron. JCI Insight. 2018, 3, e121510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel JS, Tai TC, Khaper N, Lees SJ. Mirabegron: The most promising adipose tissue beiging agent. Physiol Rep. 2021, 9, e14779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altınova, AE. Beige Adipocyte as the Flame of White Adipose Tissue: Regulation of Browning and Impact of Obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022, 107, e1778–e1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng HJ, Zhang ZS, Onishi K, Ukai T, Sane DC, Cheng CP. Upregulation of functional beta(3)-adrenergic receptor in the failing canine myocardium. Circ Res. 2001, 89, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moniotte S, Kobzik L, Feron O, Trochu JN, Gauthier C, Balligand JL. Upregulation of beta(3)-adrenoceptors and altered contractile response to inotropic amines in human failing myocardium. Circulation. 2001, 103, 1649–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treskatsch S, Feldheiser A, Rosin AT, Sifringer M, Habazettl H, Mousa SA, Shakibaei M, Schäfer M, Spies CD. A modified approach to induce predictable congestive heart failure by volume overload in rats. PLoS One 2014, 9, e87531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier C, Leblais V, Kobzik L, Trochu JN, Khandoudi N, Bril A, Balligand JL, Le Marec H. The negative inotropic effect of beta3-adrenoceptor stimulation is mediated by activation of a nitric oxide synthase pathway in human ventricle. J Clin Invest. 1998, 102, 1377–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerea Hermida, Lauriane Michel, Hrag Esfahani, Emilie Dubois-Deruy, Joanna Hammond, Caroline Bouzin, Andreas Markl, Henri Colin, Anne Van Steenbergen, Christophe De Meester, Christophe Beauloye, Sandrine Horman, Xiaoke Yin, Manuel Mayr, Jean-Luc Balligand, Cardiac myocyte β3-adrenergic receptors prevent myocardial fibrosis by modulating oxidant stress-dependent paracrine signaling. European Heart Journal 2018, 39, 888–898. [CrossRef]

- Michel LYM, Esfahani H, De Mulder D, Verdoy R, Ambroise J, Roelants V, Bouchard B, Fabian N, Savary J, Dewulf JP, Doumont T, Bouzin C, Haufroid V, Luiken JJFP, Nabben M, Singleton ML, Bertrand L, Ruiz M, Des Rosiers C, Balligand JL. An NRF2/β3-Adrenoreceptor Axis Drives a Sustained Antioxidant and Metabolic Rewiring Through the Pentose-Phosphate Pathway to Alleviate Cardiac Stress. Circulation. 2025, 151, 1312–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson KE, Martin N, Nitti V. Selective β₃-adrenoceptor agonists for the treatment of overactive bladder. J Urol. 2013, 190, 1173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balligand JL, Brito D, Brosteanu O, Casadei B, Depoix C, Edelmann F, Ferreira V, Filippatos G, Gerber B, Gruson D, Hasenclever D, Hellenkamp K, Ikonomidis I, Krakowiak B, Lhommel R, Mahmod M, Neubauer S, Persu A, Piechnik S, Pieske B, Pieske-Kraigher E, Pinto F, Ponikowski P, Senni M, Trochu JN, Van Overstraeten N, Wachter R, Pouleur AC. Repurposing the β3-Adrenergic Receptor Agonist Mirabegron in Patients With Structural Cardiac Disease: The Beta3-LVH Phase 2b Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundgaard H, Axelsson Raja A, Iversen K, Valeur N, Tønder N, Schou M, Christensen AH, Bruun NE, Søholm H, Ghanizada M, Fry NAS, Hamilton EJ, Boesgaard S, Møller MB, Wolsk E, Rossing K, Køber L, Rasmussen HH, Vissing CR. Hemodynamic Effects of Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate-Dependent Signaling Through β3 Adrenoceptor Stimulation in Patients With Advanced Heart Failure: A Randomized Invasive Clinical Trial. Circ Heart Fail 2022, 15, e009120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami HSZ, Hasselbalch RB, Søholm H, Thomsen JH, Sørgaard M, Kofoed KF, Valeur N, Boesgaard S, Fry NAS, Møller JE, Raja AA, Køber L, Iversen K, Rasmussen H, Bundgaard H. First-In-Man Trial of β3-Adrenoceptor Agonist Treatment in Chronic Heart Failure: Impact on Diastolic Function. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2024, 83, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Álvarez A, Blanco I, García-Lunar I, Jordà P, Rodriguez-Arias JJ, Fernández-Friera L, Zegri I, Nuche J, Gomez-Bueno M, Prat S, Pujadas S, Sole-Gonzalez E, Garcia-Cossio MD, Rivas M, Torrecilla E, Pereda D, Sanchez J, García-Pavía P, Segovia-Cubero J, Delgado JF, Mirabet S, Fuster V, Barberá JA, Ibañez B; SPHERE-HF Investigators. β3 adrenergic agonist treatment in chronic pulmonary hypertension associated with heart failure (SPHERE-HF): a double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023, 25, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poekes L, Gillard J, Farrell GC, Horsmans Y, Leclercq IA. Activation of brown adipose tissue enhances the efficacy of caloric restriction for treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Lab Invest. 2019, 99, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui W, Li H, Yang Y, Jing X, Xue F, Cheng J, Dong M, Zhang M, Pan H, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Zhou Q, Shi W, Wang X, Zhang H, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Cao Y. Bladder drug mirabegron exacerbates atherosclerosis through activation of brown fat-mediated lipolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019, 116, 10937–10942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres Valgas da Silva C, Calmasini F, Alexandre EC, Raposo HF, Delbin MA, Monica FZ, Zanesco A. The effects of mirabegron on obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance are associated with brown adipose tissue activation but not beiging in the subcutaneous white adipose tissue. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2021, 48, 1477–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu Y, Aoyama K, Yoneda M, Ito S, Sano Y, Kawai Y, Cui X, Yamada Y, Furukawa N, Ikeda K, Nagata K. Surgical ablation of whitened interscapular brown fat ameliorates cardiac pathology in salt-loaded metabolic syndrome rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2021, 1492, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang P, Cheng B, Wang Z, Zheng Z, Duan Q. Distinct effects of physical and functional ablation of brown adipose tissue on T3-dependent pathological cardiac remodeling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024, 735, 150844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao H, Chen X, Hu G, Li C, Guo L, Zhang L, Sun F, Xia Y, Yan W, Cui Z, Guo Y, Guo X, Huang C, Fan M, Wang S, Zhang F, Tao L. Small Extracellular Vesicles From Brown Adipose Tissue Mediate Exercise Cardioprotection. Circ Res. 2022, 130, 1490–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan CC, Kong LR, Chen XH, Ma Y, Pan XX, Zhang ZB, Gao PJ. A2A Receptor Activation Attenuates Hypertensive Cardiac Remodeling via Promoting Brown Adipose Tissue-Derived FGF21. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding Y, Su J, Shan B, Fu X, Zheng G, Wang J, Wu L, Wang F, Chai X, Sun H, Zhang J. Brown adipose tissue-derived FGF21 mediates the cardioprotection of dexmedetomidine in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 18292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod K, Datta V, Fuller S. Adipokines as Cardioprotective Factors: BAT Steps Up to the Plate. Biomedicines. 2025, 13, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang ZB, Cheng YW, Xu L, Li JQ, Pan X, Zhu M, Chen XH, Sun AJ, Lin JR, Gao PJ. Activation of β3-adrenergic receptor by mirabegron prevents aortic dissection/aneurysm by promoting lymphangiogenesis in perivascular adipose tissue. Cardiovasc Res. 2024, 120, 2307–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challa AA, Vidal P, Maurya SK, Maurya CK, Baer LA, Wang Y, James NM, Pardeshi PJ, Fasano M, Carley AN, Stanford KI, Lewandowski ED. UCP1-dependent brown adipose activation accelerates cardiac metabolic remodeling and reduces initial hypertrophic and fibrotic responses to pathological stress. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.; Patel, S.; Mani, S.; Hussain, T. Role of angiotensin type 2 receptor in improving lipid metabolism and preventing adiposity. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 461, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, S.; Khan, M.A.; Samuel, P.; Ali, Q.; Hussain, T. Chronic angiotensin AT2R activation prevents high-fat diet-induced adiposity and obesity in female mice independent of estrogen. Metabolism 2015, 64, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Than, A.; Xu, S.; Li, R.; Leow, M.-S.; Sun, L.; Chen, P. Angiotensin type 2 receptor activation promotes browning of white adipose tissue and brown adipogenesis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao XY, Liu Y, Zhang X, Zhao BC, Burley G, Yang ZC, Luo Y, Li AQ, Zhang RX, Liu ZY, Shi YC, Wang QP. The combined effect of metformin and mirabegron on diet-induced obesity. MedComm (2020). 2023, 4, e207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description | Forward sequence Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Col1a1 | Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Chain | 5′-CAT TGT GTA TGC AGC TGA CTT C-3′ 5′CGC AAA CAC TCT ACA TGT CTA GG-3′ |

| Col3a1 | Collagen Type III Alpha 1 Chain | 5′-TCT CTA GAC TCA TAG GAC TGA CC-3′ 5′ TTC TTC TCA CCC TTC TTC ATC C-3′ |

| Nppa | Natriuretic Peptide B | 5′-CTC CTT GGC TGT TAT CTT CGG-3′ 5′-GGG TAG GAT TGA CAG GAT TGG-3′ |

| Nppb | Natriuretic Peptide A | 5′-AGG TGA CAC ATA TCT CAA GCT G-3′ 5′-CTT CCT ACA ACA TCA GTG C-3′ |

| Ppia | Cyclophilin A | 5′-TTC ACC TTC CCA AAG ACC AC-3′ 5′-CAA ACA CAA ACG GTT CCC AG-3′ |

| Postn | Periostin | 5′-GCT TTC GAG AAA CTG CCA CG-3′ 5′-ATG GTC TCA AAC ACG GCT CC-3′ |

| Thbs4 | Thrombospondin 4 | 5′-GAT ACT GAC GGG GAT GGG AG-3′ 5′-CGT CAC TGT CTT GGT TGG TG-3′ |

| Ucp1 | Uncoupled protein 1 | 5′-GCT TCT ACG ACT CAG TCC AA-3′ 5′-CTC TGG GCT TGC ATT CTG AC-3′ |

| Adrb3 | Adrenoceptor Beta 3 | 5′-AGG AAG CTT GCT TGA TCC-3′ 5′-AGG AAG CTT GCT TGA TCC-3′ |

| Rpl13 | Ribosomal Protein L13 | 5′-CGG CTG AAG CCT ACC AGA AA-3′ 5′-GGA GTC CGT TGG TCT TGA GG-3′ |

| Males | |||||||

| Parameters | Ctrl/Veh(n=8) | MHS/Veh(n=8) | Ctrl/Mira(n=8) | MHS/Mira(n=7) | MHS | Mira | MHS X M |

| PWd, mm | 0.79±0.016 | 1.03±0.027d | 0.75±0.014 | 1.05±0.021d | <0.0001 | 0.52 | 0.087 |

| IVSd, mm | 0.75±0.013 | 0.91±0.023d | 0.75±0.013 | 0.99±0.020d,g | <0.0001 | 0.032 | 0.028 |

| ESD, mm | 2.79±0.075 | 2.77±0.098 | 2.40±0.085f | 2.01±0.071b,h | <0.0001 | 0.026 | 0.034 |

| LVM, mg | 106±1.8 | 134±5.1d | 100±2.5 | 123±5.2c | <0.0001 | 0.046 | 0.57 |

| SV, mm | 31±2.2 | 31±1.5 | 31±1.7 | 26±1.3 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.22 |

| HR, bpm | 498±10.4 | 513±17.0 | 518±14.0 | 561±11.7a,e | 0.044 | 0.021 | 0.31 |

| CO, ml/min | 15.2±1.07 | 15.8±1.05 | 15.9±0.60 | 14.6±1.22 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.37 |

| Females | |||||||

| Parameters | Ctrl/Veh (n=8) | MHS/Veh (n=8) | Ctrl/Mira(n=8) | MHS/Mira(n=8) | MHS | Mira | MHS X M |

| PWd, mm | 0.71±0.024 | 0.88±0.024b | 0.71±0.011 | 0.96±0.056c | <0.0001 | 0.23 | 0.27 |

| IVSd, mm | 0.70±0.020 | 0.84±0.015d | 0.67±0.010 | 0.81±0.031d | <0.0001 | 0.15 | 0.90 |

| ESD, mm | 2.52±0.105 | 2.33±0.061 | 2.34±0.096 | 2.20±0.076 | 0.0680 | 0.088 | 0.78 |

| LVM, mg | 88±1.7 | 109±3.2d | 81±2.9 | 103±4.0d | <0.0001 | 0.044 | 0.83 |

| SV, mm | 31±0.7 | 30±1.5 | 25±0.7g | 26±1.3e | 0.62 | 0.0022 | 0.26 |

| HR, bpm | 516±11.2 | 528±6.0 | 514±15.0 | 538±17.6 | 0.19 | 0.74 | 0.67 |

| CO, ml/min | 15.4±0.85 | 15.6±0.84 | 13.1±0.43e | 14.0±0.46 | 0.40 | 0.0061 | 0.64 |

| Males | |||||||

| Parameters | Ctrl/Veh(n=8) | MHS/Veh(n=8) | Ctrl/Mira(n=8) | MHS/Mira(n=7) | MHS | Mira | MHS X M |

| E, mm/s | 659±14.8 | 537±21.0c | 653±23.7 | 533±21.2c | <0.0001 | 0.81 | 0.97 |

| A, mm/s | 431±16.5 | 388±21.1 | 391±13.5 | 405±19.9 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.12 |

| E slope | -39160±2804 | -33681±1799 | -37444±1566 | -33247±2466 | 0.037 | 0.63 | 0.77 |

| IVRT, ms | 16.8±0.53 | 16.0±0.35 | 15.7±0.49 | 15.3±0.47 | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.80 |

| E’, mm/s | 29.4±0.99 | 24.0±1.90b | 30.0±0.77 | 22.8±0.75c | <0.0001 | 0.82 | 0.50 |

| A’, mm/s | 17.8±0.81 | 16.5±1.29 | 14.9±0.44e | 14.8±0.96 | 0.46 | 0.021 | 0.55 |

| E/A | 1.5±0.04 | 1.4±0.03a | 1.7±0.05e | 1.3±0.05d | <0.0001 | 0.40 | 0.020 |

| E/E’ | 20.8±1.17 | 21.1±0.90 | 21.9±0.94 | 23.7±1.20 | 0.32 | 0.96 | 0.58 |

| LA diam, mm | 2.34±0.049 | 2.46±0.081 | 2.18±0.041 | 2.42±0.067b | 0.0058 | 0.11 | 0.32 |

| Females | |||||||

| Parameters | Ctrl/Veh(n=8) | MHS/Veh(n=8) | Ctrl/Mira(n=8) | MHS/Mira(n=8) | MHS | Mira | MHS X M |

| E, mm/s | 560±23.9 | 604±28.9 | 532±11.3 | 650±45.2b | 0.012 | 0.76 | 0.22 |

| A, mm/s | 374±11.8 | 398±21.8 | 315±7.2 | 302±22.3 | 0.74 | <0.0001 | 0.29 |

| E slope | -38869±1323 | -35653±2291 | -36251±1234 | -39024±4731 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.29 |

| IVRT, ms | 15.1±0.29 | 16.1±0.57 | 15.9±0.47 | 16.0±0.43 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.32 |

| E’, mm/s | 30.5±0.29 | 24.1±1.10c | 29.6±0.67 | 26.5±1.20a | <0.0001 | 0.14 | 0.33 |

| A’, mm/s | 18.5±0.78 | 17.8±0.67 | 16.0±0.43e | 13.0±1.31a,f | 0.029 | 0.0003 | 0.31 |

| E/A | 1.6±0.04 | 1.5±0.07 | 1.7±0.06 | 2.2±0.20b,g | 0.0004 | 0.018 | 0.031 |

| E/E’ | 18.6±0.71 | 23.1±1.23b | 18.1±0.65 | 24.6±1.15c | <0.0001 | 0.20 | 0.43 |

| LA diam, mm | 2.13±0.0027 | 2.30±0.053a | 2.13±0.055 | 2.38±0.088b | 0.0017 | 0.48 | 0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).