1. Introduction. The Contemporary Landscape Between Mass Tourism and Digital Evolution: The Case of the Phlegraean Fields

The contemporary landscape represents the fundamental hub that connects the processes of building territorial identity with experiences of spatial enjoyment. Depending on how the landscape is structured, it can catalyse infinite forms of experience, amplifying its appeal to users in relation to the scale of the area, its geographical location and its historical and cultural qualities. These factors can determine the centrality of a certain landscape within the social framework, depending on its aesthetic and cultural values, its inner symbolic character, and the experiences it can offer to the community that uses it. Indeed, it is well known how strongly social and cultural factors can influence the collective imagination, thereby defining ordinary or tourist practices that are heterogeneous in terms of purpose and modalities [

1].

In this context, research is converging towards multidisciplinary studies aimed at understanding the extent to which tourist flows influence the very definition of landscape, from a functional and perceptive point of view [

2,

3,

4,

5], although it is important to focus on analytical and design models and frameworks that can interpret the complexity of the dynamics of mutuality between landscape assets and their use. It is inevitable that tourism exerts considerable pressure on the landscape. The effects can be seen both in quantitative terms, with an increase in visitor numbers, especially at specific moments of the year, and with a growing consumption of resources, and in terms of overall quality. One example is the real possibility that the identity of places could be gradually eroded by occasional consumers of ecological and cultural amenities, leading to a standardisation of landscape use and undermining the everyday practices of communities that live in these valuable spaces. Mass tourism, in particular, has exacerbated spatial polarisation dynamics, congesting specific landscape hotspots and contributing to the marginalisation of areas that are less accessible or perceived as less profitable in terms of territorial marketing [

6]. In this context, the concept of tourist carrying capacity, introduced by the World Tourism Organisation, is an essential tool for sustainably managing flows, with a view to providing an integrated and multi-scale reading of the critical issues and potential of the territorial system (

Figure 1) [

7].

This notion is divided into several dimensions — ecological, cultural, social, infrastructural and organisational — each of which contributes to defining the limits within which it is possible to ensure usage that is compatible with local resources and values. When properly regulated, tourist flows can nevertheless be a lever for urban regeneration and territorial enhancement, promoting investment in green infrastructure and sustainable mobility solutions that improve accessibility to important landscape areas while reducing anthropogenic impact [

8]. The tourist experience thus becomes an opportunity to rethink the balance between use and protection, between promotion and preservation, with a view to integrated development.

In any case, it is important to consider the evolution of methods of enjoying the landscape, due to the increasing digitalisation of the tourist experience, which has introduced new ways of accessing and representing the territory. Immersive technologies such as virtual and augmented reality, geo-storytelling tools and interactive platforms are gradually changing the very experience of visiting places, complementing direct enjoyment with other ways of interacting with the landscape that are parallel to, and sometimes even replace, physical presence [

9]: while on the one hand these tools amplify the accessibility of cultural and natural heritage even to distant users, effectively removing geographical barriers, on the other hand they raise doubts about the authenticity of the experience, understood as a direct relationship of knowledge between users and the space they experience.

The emergence of forms of virtual tourism, accelerated by the recent pandemic crisis, marks a paradigm shift that reinterprets tourist space as a hybrid and multi-level environment, in which the experience is mediated, narrated and georeferenced. Over time, the fragility of the globalised tourism model has been highlighted, opening up new possibilities for a more sustainable and responsible rethinking of tourism, oriented towards community well-being and territorial resilience [

10,

11]. However, there is still a need to consider digital tools, in all their forms, as complementary to the physical landscape, rather than a substitute for it, since knowledge can truly be experienced only in situ. In this sense, there is value in the hypothesis that landscape should not be understood as a mere backdrop to the tourist experience, but rather as a situated epistemic key, capable of broadening users’ cultural awareness and intensifying their sense of belonging and responsibility towards places. Therefore, it seems necessary to understand how crossing landscapes can become a means of spatial understanding, in direct contact with the environment but also through new technologies. In this sense, on the one hand, slow mobility practices that follow thematic itineraries are configured as devices through which the landscape manifests itself in its layered complexity as a dynamic palimpsest [

12]; on the other hand, the digital enjoyment of places takes the form of an experiential modality which, while not able to fully restore the importance of direct interaction, can nevertheless integrate the immersive dimension, enhancing the immaterial value of the landscape and acting as a mediating element between meta-sensory narration and spatial enjoyment [

13,

14].

Based on these considerations, the Phlegraean Fields, located on the western coast of the metropolitan area of Naples, represent a unique case study due to their unique landscape and geological features. They are the largest volcanic caldera in Europe and the second largest in the world after Yellowstone. From an archaeological point of view, the Phlegraean area is equally significant, as ruins and remains have emerged since the Renaissance that are almost intact compared to the urban sites found in Rome.

However, in recent decades, the natural integration between socio-cultural and ecological-environmental elements has been progressively overshadowed by widespread urbanisation, which is why the rich natural heritage (consisting of lakes, coastal areas, protected woodlands, various SPAs and SCIs) and cultural heritage is now highly fragmented and shows extensive signs of degradation, exacerbated by a weak mobility network dominated by car traffic, to the detriment of its accessibility by local users and tourists, leading to the deterioration of the interconnections between the key elements of the territory. Added to this is the significant volcanic risk, which is receiving increasing media attention and requires strategic and planning efforts in the medium and long term.

The fragmentation of the Phlegraean territory prevents an effective integration of its naturalistic and historical-archaeological areas, with a consequent loss of tourist and cultural value. Alongside the discontinuity of the main emergencies in the area, there is also widespread carelessness that hinders its enjoyment: from the point of view of accessibility, there are paths that are impossible to walk along due to overgrown vegetation, while street furniture is often subject to damage of various kinds, and signage is not always sufficiently visible to guide visitors. Several sites are currently closed to the public, depriving users not only of ecologically valuable spaces but also of elements of archaeological and identity value.

In light of these considerations, this contribution, included in the PNRR research project Changes ‘Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Sustainable Society’ - PE5Changes_Spoke1-WP4-Historical Landscapes Traditions and Cultural Identities, aims to define a framework for understanding the Phlegraean landscape and its intrinsic complexity, with a focus on exploring the theme of direct experience of places in synergy with digital enjoyment of the landscape. The objective is to provide a multi-level interpretation that allows, on the one hand, to get to know the Phlegraean Fields not only from a tourist point of view, but also from the perspective of ordinary use by local users, and on the other hand, to broaden the spectrum of information through technological and digital approaches that allow users to further explore the physical landscape, accessing and at the same time implementing the geolocalised database.

2. Walkability as a Lens to Understand Landscape Along Experiential Transects

It is worth emphasising how much the configuration of the territory affects the way in which space is used, also depending on the presence of certain significant cultural or physical assets: this brings back the possibility of studying and understanding the landscape through a visual approach based on direct experience of the places. Given the complexity of planning, this could facilitate understanding of the relationships between users and the environment in which they interact. Landscape areas are in fact a translation of individual perceptions, becoming true commons that condense shared meanings when they are generally shared by the community [

15].

In line with these premises, the concept of

walkability has become increasingly important in urban planning, sustainable mobility and, more recently, in the understanding of the urban landscape as a form of experiential knowledge: the theory indicates the degree of simplicity with which a service or place can be accessed by foot, with positive impacts on mental and physical health [

16,

17]. This concept measures the capacity of a given place to support and encourage the use of space through physical exploration, making it a privileged way of establishing a direct perceptive relationship with landscape assets. This relationship is consolidated through physical actions on site, such as observation, but also through social interaction, constituting the interpretative tools of the landscape itself and at the same time representing a dynamic experience for the user (

Figure 3) [

18].

The concept remains a topic for further exploration in decision-making processes, as it can serve as a link between the community’s desires with regard to certain goals, the actual willingness to travel a certain distance to achieve them, and the actual quality of the routes available. In terms of sustainability and social inclusiveness, walkability can describe the extent to which an area supports soft mobility, promoting a fair relationship between distances, times and accessibility, while enhancing not only the value of the assets to be reached but also the quality of the landscape in which the routes are located [

19]. The aesthetic, ecological-cultural and functional characteristics of the landscape are important incentives for the development of walkability, as they influence the sense of comfort and safety when crossing certain places, encouraging place attachment and a propensity for pedestrian exploration, also through the integration of specific landmarks within slow routes in order to implement processes of familiarisation with the context and the visual-sensory experience. These considerations suggest that walking can be intended as a multisensory tool for understanding space, especially in areas with a strong cultural and landscape character, as well as for identifying the specific critical issues of places [

20]. Walkability encodes an experiential mode of movement that rebuilds interaction with the landscape, recognising its characteristic signs, peculiarities and complexities, quantifying in a certain sense the degree of accessibility to shared knowledge of places, channelling elements of the community’s imagination of urban experience [

21].

This is particularly relevant in urban contexts with a rich historical and cultural matrix: the morphology of such places is often favourable to walkability, at least in terms of the inherent environmental and socio-cultural values that can promote an immersive experience in the urban landscape, through the lens of slow mobility as a tool for heritage enhancement and knowledge. However, critical issues such as the physical conformation of the territory, as well as growing anthropogenic pressure and related contemporary urban transformations, must be taken into account. These are linked to the progressive reduction of spaces intended for pedestrian use, to the advantage of increasingly prevalent road mobility, requiring integrated and sustainability-oriented approaches [

22]. The experience of walking therefore proves to be a cognitive device which, far from being a merely practical tool, allows to grasp the complexity of material and immaterial values: it is thus possible to interpret the landscape through direct interaction, combining the user’s visual-sensory and cognitive experience with the real space and the geographical narrative of the places themselves [

23]. This leads to the need, in the analytical and planning fields, to recognise walkability as a fundamental epistemic dimension, aimed at connecting the assets of the territory in an inclusive and conscious manner. For this reason, it is necessary to implement a dynamic and adaptive pedestrian network within complex landscape areas, based on temporal, morphological and socio-demographic factors [

24].

Since the enjoyment of the landscape depends on spatial knowledge, the landscape matrix of planning strategies can be implemented through the choice of an approach such as the

experiential transect (

Figure 4). In geography, a transect is a specific method of territorial analysis organised along a linear trajectory: this exploratory procedure requires careful analysis of the various anthropic and environmental elements that contribute to the definition of the landscape structure, studying in sequence the ecological-spatial relationships that connect them [

25]. For this reason, it is appropriate to refer to a real analytical-operational protocol that defines a methodological framework through which is possible to develop various narrative outputs that follow the conventional form of the territorial section, albeit through the personal and subjective lens of field exploration: in fact, this feature represents the distinctive and innovative trait of the proposed approach, which, while proposing direct lines of study that connect relevant points in space, maintains the importance of the user’s experience, so that it can enrich the system and, at the same time, enrich the user, who gains awareness of the potential but also the critical issues of the place [

26].

The act of crossing a transect reveals the prior knowledge and perceptions that each observer brings with them, bringing to the fore, on the one hand, their personal wealth of experience and, on the other, a set of collective expectations built up through comparison with previous explorations in environments perceived as similar, while taking into account differences in socio-morphological composition, economic dynamics and ecological and environmental issues [

27]. In this sense, the experiential transect can promote integrated involvement with the field of study, also in relation to the functional links that are established and highlighted [

28].

In this context,

cultural itineraries, recognised by institutions such as UNESCO and ICOMOS, take on strategic importance as operational and exploratory tools for the landscape: a cultural itinerary is a specific type of asset composed of various elements, tangible or intangible, interrelated in space, not necessarily characterised by geographical contiguity but fundamental for the creation of a system of knowledge [

29]. In fact, these itineraries can be likened to the notion of transect, as they are essentially linear and capable of activating an immersive cognitive process within a territorial area, integrating themselves into the planning dynamics related to slow mobility and the direct enjoyment of the widespread cultural heritage, activating complex cognitive processes in which sensory perception intertwines with memory and landscape narration. They structure an interpretative experience that combines subjective vision and collective references, constituting a means of communication and cultural exchange, a tool for consolidating identity in a process of reappropriation of the collective landscape [

30,

31].

In this sense, the value of cultural itineraries in contributing to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda is emphasised, through forms of responsible tourism that promote social inclusion, protection of cultural heritage, enhancement of local features and territorial cohesion. The experience of walking along thematic itineraries can activate forms of situated knowledge, capable of restoring meaning to places and promoting greater awareness of the link between landscape and social identity [

32].

Walking along these routes is therefore equivalent to embarking on a layered cognitive experience, which develops in continuity with the experiential transect approach: walking through places allows us to understand the landscape in its fundamental parts, which in turn acquire meaning within a network of relationships. The richness of these experiences lies in their ability to integrate observation, immersive knowledge and participation, generating widespread awareness that feeds the active consciousness of users [

33]. In conclusion, the experiential transect tool, applied to the theory of walkability and in the context of cultural itineraries, offers a theoretical and operational opportunity to renew landscape knowledge practices, combining the methodological rigour of territorial analysis with the subjective dimension of direct experience. This integration produces an epistemological model capable of restoring complexity and depth to the study of space, making the landscape not only an object of observation, but a system of cultural, ecological and social relationships.

3. Applied Methodology. Socio-Spatial Analysis and Phygital Development of Phlegraean Landscape

These premises led to the definition of a composite research methodology for the Phlegraean Fields that would allow for the analysis of the landscape complexity by connecting the various elements which make this place unique, in order to enhance them and expand the knowledge and awareness of the local community, exploiting both the exploratory potential of walkability and the digital implementation of the Phlegraean landscape.

In order to spatialise the network of local landscape assets and categorise the different ways in which they can be enjoyed, it is proposed to create a spatial data model. This tool, which is related to geographical disciplines, allows information related to a physical space to be georeferenced, classifying its various components into geometric objects with precise spatial features, which are useful for describing the distribution of elements and their functions across the territory, as well as the attributes that describe their main properties [

34]. In this context, the use of such a tool has significant strategic implications, as it proves invaluable for analytically addressing the issue of accessibility to certain assets, identifying the services and places of greatest interest within a given radius of action [

35].

Following these considerations, through which it is possible to create a comprehensive database of the study area, it may be useful to focus detailed studies on selected experiential transects of the Phlegraean Fields, in line with certain parameters linked to the actual use of the road infrastructure in relation to local main hotspots and local planning strategies (

Figure 5). The methodology has therefore identified a number of significant routes, based on their integration into the landscape and the network of local goods and services, especially in relation to their proximity to natural and cultural attractions. Using dedicated road sheets, the main features that influence the functionality and connectivity of the soft mobility system have been mapped, as well as the actual attractiveness of these connections for users.

The experiential transect thus translates into the selection of potential itineraries that can facilitate understanding of the Phlegraean landscape, with a view to soft mobility but also to enhancing its unique features. In this regard, the geospatial study is enriched by appropriate collaborative mapping actions aimed at expanding the database and involving users in the analytical and operational processes. The community has also been involved through specific surveys aimed at listening to demands and desires regarding the evolution of the Phlegraean area, as well as possible suggestions for improvement.

Tools to strengthen knowledge of the landscape have therefore been implemented through GIS-based tools that combine the analytical-planning component with experiential-participatory involvement, through the creation of a digital geo-storytelling. This concept brings the principles of ‘urban storytelling’ to the scale of the local spatial context, transforming geographical data and maps into real interactive stories. This results in narratives in which different multimedia data are integrated to provide a better understanding of spatial relationships, environmental phenomena, historical and socio-cultural processes [

36]. The mapping platform organises geolocated information relating to identified landscape assets, through which users can deepen their knowledge of the place, guided in an informed and engaging way [

37].

4. Experientiality and Spatial Analysis: Definition of a Participatory Geo-Database for the Phlegraean Landscape

The application of the research methodology led to the definition of a geo-database for the landscape of the Phlegraean Fields. The reflections presented here are clearly linked to the unique conditions of this landscape, and in particular to the complexities inherent in its management: despite the presence of important institutions and authorities responsible for heritage and environmental protection, the Phlegraean landscape is still largely in a state of spatial and functional disorder. Despite existing strategies to enhance the ecological and cultural networks, fragmentation is still one of the distinctive features of the study area, making it difficult for the average user to understand and appreciate it. The use of footpaths is often inhibited, as well as visits to several local archaeological sites. There is therefore a need to corroborate basic knowledge with technical data and experiential insights: this would clearly have a positive impact both on citizens who live in these places on a daily basis and on tourists who could enjoy this unique landscape in a more efficient and responsible manner.

The methodological approach therefore focuses on defining significant experiential transects in order to promote walkability as a fundamental cognitive element. For this reason, the spatial data model proposed here explores the needs of soft mobility in more depth, in line with the dynamics of sustainable planning from both an ecological and social point of view. This promotes community autonomy, favouring pedestrians in denser urban areas, where numerous critical issues are linked to inadequate road infrastructure, the growing number of functional requirements and the orographic and physical conditions of the terrain. Keeping in mind safety and usability as the main requirements for an adequate landscape experience system, the structure of the spatial data model is then divided into groups of layers, as summarised below:

Basic layers. These include aerial photogrammetry, various types of maps, and three-dimensional models dating back to different periods. They are useful for comparing the current situation with the past, but also for mapping the spatial data of the next layers.

Legal constraints. They highlight the main normative documents that influence and regulate the ways in which transects and the mobility system in general can be enjoyed, as well as the spaces and assets they connect. Reference is made to constraints related to environmental risks, but also to ecological constraints and limitations on vehicle accessibility and traffic, as well as the actual possibilities of accessing landscape assets.

Local main hotspots. They identify the most relevant points of interest in the reference area. Since dense city areas offer a number of services that are often scattered throughout the urban landscape, it is important to understand the actual location of the places that residents, commuters and tourists tend to visit, as this can lead to challenges related to an overloaded and not always adequate accessibility and service network.

Mobility system. They indicate the more or less extensive network through which users can reach the local main hotspots, either by road or rail, as well as by slow and sustainable means of transport. Parking spaces for cars and motorcycles are also identified, as well as spaces for bike sharing and electric scooter rental.

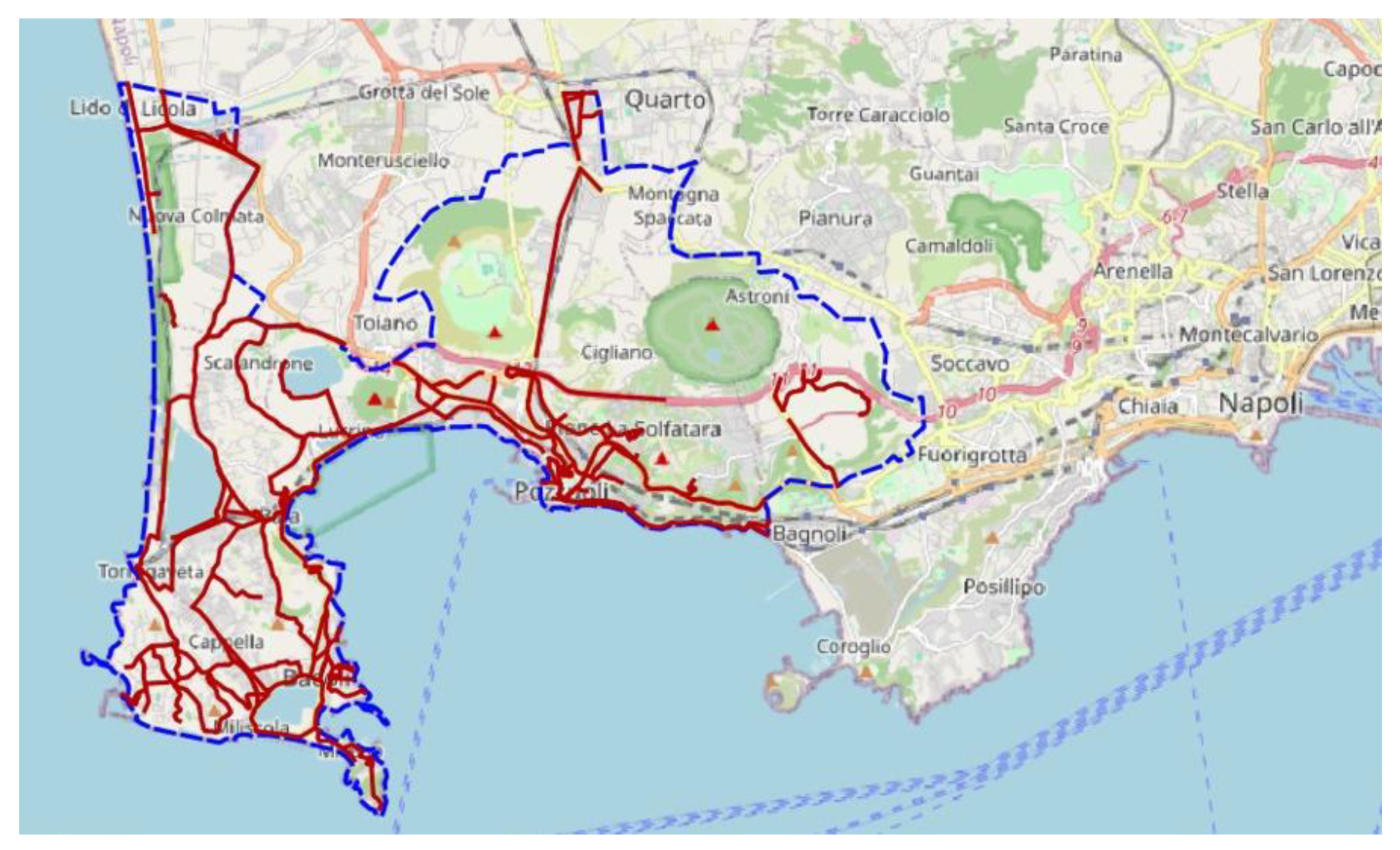

In accordance with the criteria established by the theoretical premises and methodological approach, approximately 13.8 linear kilometres of the Phlegraean mobility network were analysed, mainly in the municipalities of Pozzuoli, Bacoli and Monte di Procida, together with some neighbourhood in Napoli and Quarto: intended as possible experiential transects, these road sections connect cultural and environmental assets with each other, as well as basic services. The logic is to study the use of the landscape in a broad sense, considering on the one hand the riches and attractions of the area and, on the other, the common functions that serve both the everyday lives of citizens and occasional visitors.

Various aspects of the network connecting the Phlegraean hotspots were studied in situ in order to understand the quality of the routes and their actual efficiency (

Figure 6).

Most of these showed a fairly positive level of maintenance: approximately 90% of the routes analysed are in good condition, compared to 9% in poor condition and only 1% in very poor condition. These road sections appear to be almost entirely paved with asphalt (approximately 99%), with only 1% composed of stone material. This clearly reflects the generally good maintenance of the transects studied but also indicates a material standardisation that may tend to erase traces of pre-existing historic paving.

With regard to pedestrian accessibility, almost all of the road sections analysed are mainly dedicated to car transport, limiting the possibility of directly experiencing the landscape in terms of walkability: 37% of these have pavements on both sides, while only 11% have pavements on just one side and almost 20% have discontinuous pavements; however, a significant portion, equal to one third of the entire sample, is completely lacking in pavements or areas dedicated to pedestrian use.

Since the use of places, especially from a slow mobility perspective, is linked to perceptions of safety [

38], it is important to map the characteristics that can actually influence it negatively: these include the level of lighting, which is good in only 19% of road sections, while approximately 17% have a mediocre level of lighting and 15% have a poor level of lighting; this leaves 50% of the routes studied without any lighting at all, seriously compromising fruition of landscape assets.

In order to promote forms of experiential engagement with the Phlegraean landscape on the one hand, and to improve the quality of the geo-database on the other, user participation is essential, through the use of digital co-mapping techniques [

39,

40]. The validation of such data, as well as its progressive updating, thus requires the effective involvement of the community, which is called upon to actively suggest hypotheses and express needs, as well as to expand its own knowledge of the Phlegraean area.

To this end, a Google My Maps platform has been set up, following which the data has been refined in the processing phase and will be further updated based on the feedback collected. Users can then note down their personal impressions, preferably in photographic form with supporting notes, and share their non-expert knowledge, which is essential in providing an accurate and up-to-date picture of such a complex and varied landscape (

Figure 7).

At the same time, perceptive analysis makes use of questionnaires distributed throughout the survey area. This is useful for gathering specific perceptions, needs and, in general, the social representations of the reference community on the issue of accessibility, as part of an integrated development programme. This choice is potentially preferable as it allows citizens to take on greater responsibility within a complex framework of which they are active users. It also involves a diverse range of users, allowing for a greater exchange of knowledge and skills between the actors concerned, addressing areas and issues considered a priority by users and increasing the perceived usability of spaces. Finally, this approach allows for a more effective response to the planning and programmatic requirements of the institutions involved. A total of 133 questionnaires were disseminated, in generally equal proportions between men (43%) and women (57%), divided by age group. This may be considered sufficient to obtain results that can be generalised, according to the concept of representativeness: a relatively small social sample can provide empirically acceptable data, if its composition is homogeneous and representative of the context of reference, in relation to a given phenomenon in a specific context (de Singly, 2021).

The survey highlighted that the easiest way to travel across the Phlegraean landscape is by motorbike (25% of users consider this an easy way to get around), while a quarter of the sample believe that it is particularly difficult to reach local amenities by public transport (both rail and road) or by bicycle, probably also due to the terrain.

Pedestrian access to the Campi Flegrei is considered average easy, although 29% of users consider it their preferred mode of transport, second only to cars with 42%. This is noteworthy, as users complain strongly about the lack of parking spaces for vehicles, with 51% finding the current facilities deeply inadequate (

Figure 8).

Another interesting piece of data is the study of accessibility to key public social services and ecological and cultural assets, which is considered adequate in both cases (53% and 46% respectively), although a significant portion of the study sample considers this parameter to be lacking, with 27% for services and 33% for ecological-cultural assets in the Phlegraean area.

From a strategic point of view, although on-site surveys have shown that the reference road sections are in good condition, a significant 32% of the sample believe that this is the primary aspect for which priority action should be taken, followed by the development of cycling and walking paths (20%). This finding is emblematic of the importance of community perception in analyses involving such complex landscapes. It also demonstrates the importance of ensuring that a potential transect is properly managed, alongside the need to implement efficient spaces for pedestrian exploration and direct experience.

5. Phygital Approach to Amplify Landscape Fruition

The physical crossing of space, the awareness of dimensions and orography, shapes and distances is an irreplaceable direct exploration for knowledge, but the landscape in its broadest (and most complex) sense is not limited to the space inhabited by physical action, as it activates ever-changing multisensory perceptions, memories, and interpretative keys filtered through individual and collective knowledge. The experience of spatially crossing landscape can be considered as the interface that enables contact between the physical, material object, i.e., places, and its changing perceptions, individual and historical memories, activating an emotional aspect that constitutes the immaterial part of the experience.

If the experience of landscape is implemented through digital content, the typical linear flow of narration activates a network of possible points of knowledge to be interpreted and connected according to one’s personality and sensitivity. The phygital space, understood as a physical space blended with the digital, provides an experiential microsphere in which people, acting physically in places and interacting with digital content, increase their ability to connect with the immaterial aspects of landscape exploration. The journey thus becomes a physical performative act that is indispensable for the knowledge and creation of a narrative storytelling, unique to each exploration as it is independently decided through the multiple choices made possible by non-linear interactivity with digital content. The implementation of digital content can guide the physical experience of traversing space, highlighting latent aspects, recalling historical memories, bringing out distinctive features that are not immediately apparent, and thematically intertwining distant physical places through a guided journey of discovery. The augmented, immersive and virtual exploration of the landscape can transform physical spaces into places of a narrative that transcends and coexists with the limits of material reality. In particular, in highly stratified historical landscapes, such as the Phlegraean Fields, the cultural heritage of a community is characterised precisely by that inseparable link between its material component, which roots it to the territory, and its immaterial dimension, capable of arousing imagination and attributions of value. This dual nature, intertwined with the temporal dimension of history and anthropogenic transformations of the territory, contributes to defining its uniqueness. At the same time, the design and creation of digital content for a phygital experience require representation strategies that are able to hold together the complexity of all these aspects. We therefore asked ourselves how we could create a phygital space for the Phlegraean Fields that would be capable of communicating the inseparable intertwining of the natural ecosystem, representation and the sedimentation of historical and cultural processes.

Today, new models of territorial enhancement are constantly determined and conditioned by rapid advances in digital technology. The very notion of enhancement is undergoing a profound renewal thanks to the opportunities offered by new representation and communication technologies. In particular, for the Phlegraean Fields, the problem of the physical fragmentation of the landscape has been repeatedly highlighted, which is difficult to overcome with specific and targeted interventions. In this context, digital representation can be an effective strategy for re-establishing narrative links between places, artefacts and landscapes in order to rebuild relationships with local communities on the basis of emotional and interactive experiences, supporting the creation of a flexible digital network of spaces, data and information that are located in equally fragmented and distant physical contexts.

The choice therefore fell on a dynamic and interactive communication system, namely

Esri’s Storymaps, populated with pictorial images produced between the 18th and 19th centuries that formed the shared imagery of the Phlegraean Fields and now constitute an important testimony to a state that has completely changed as a result of the wild and chaotic construction that the area has undergone since the 20th century (

Figure 9). The pictorial images serve both as a frame for memory and as a guide for observation along the route. The artists who have depicted the Phlegraean Fields over time have been able to synthesise their distinctive elements, contributing to the formation of a collective imagination made up of identity, peculiarities and memories, referring not only to a physical landscape but also to a mental dimension. Depictions of the landscape are not simply expressions of the artist’s individual vision, but also reflect the tastes, knowledge and trends of a particular cultural, historical and geographical context [

41].

Through these images, the research aimed to develop a new narrative model for the representation of the Phlegraean Fields, returning it to the contemporary community to promote a more conscious and profound enjoyment of the landscape in experiential spaces made up of hybrid physical places. Telling stories through maps is certainly not new, but current webGIS applications are revolutionising traditional cartography by including multimedia content and diverse information on maps, thus recovering the plural meaning of landscape. Storymaps, from ESRi’s ArcGIS online platform, combines the specific features of web-GIS software with digital storytelling tools, allowing us to associate digital maps, and therefore the dynamic representation of the territory, with numerous multimedia contents, such as texts, images, hyperlinks and audio, which can be enjoyed on site with a simple smart device and with which to hybridise the physical experience of the landscape.

The dynamic and interactive structure of Storymaps allows for strategic support of communication and promotion of the landscape through creative and interactive methods of storytelling or, more correctly, placetelling.

In a constant relationship between territory and narrative through the tools of digital storytelling, the Storymaps created (that is available at the following link

https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/c33b7e2315f94c5d84fbccde0488743e) has been divided into five main sections, each dedicated to one of the thematic itineraries previously identified in the analysis of the paintings. The narrative proceeds through textual narratives, graphic diagrams, videos, and interactive maps (

Figure 10) and swipe images (

Figure 11). The latter are a digital window for the informed interpretation of the transformations undergone by the Phlegraean landscape, often unrecognisable after decades of illegal building and uncontrolled settlement growth. The swipe window provides, on site, the possibility of intuitively comparing a current photograph of what can be seen from that point of view with what the artist was able to see in his time, filtered, of course, through his artistic and interpretative act. The ancient and contemporary forms of these places are linked through a comparison guided by the interactive technology of Storymaps, while at the same time connecting the phygital experience of the individual place to thematic paths of knowledge through the dynamic interface of GIS maps produced with a narrative approach.

6. Conclusions

The research experience in the Phlegraean Fields described here tries to show that the landscape can be reinterpreted through practices that blend physical exploration and digital storytelling, integrating material and immaterial values in a coherent and understandable way. Through the lens of the phygital approach, diving into the landscape takes on a deeper meaning, as the user can tap into additional, situated and multi-level forms of knowledge that are fundamental for building a strong territorial identity and landscape consciousness. The walkability approach, applied to experiential transects in physical or dematerialised form, can act as a counterbalance to the technological aspect of the framework, anchoring it to a basis of knowledge derived from reality, fitting perfectly into the phygital theory.

The integration of this dual approach with forms of community participation through co-mapping and digital geo-storytelling therefore allows us to rethink the enjoyment of the landscape not only in aesthetic terms, but also in terms of the relationality on which it is based. In this sense, the construction of an integrated geo-database of the Phlegraean landscape, based on complementary layers, represents not only analytical support for territorial strategies, but also an educational and dialogic platform aimed at promoting the empowerment and active involvement of local communities.

It should be noted that the main output is a means of supporting institutions and bodies operating in the area for the area, drawing on data collected in a participatory manner to encourage landscape promotion, also in relation to the most massive tourist flows, knowing the values and critical issues of the Phlegraean area, thanks to the production of maps informed by various local assets and the Storymaps repository.

In conclusion, the contribution therefore aims to highlight, on the one hand, the complexity of analysing landscape areas that are as stratified as they are subject to critical anthropogenic phenomena, such as tourist pressure and heavy urbanisation, to the detriment of the existing heritage and local communities, on the other hand, it has sought to provide an interpretation that takes into account the dynamics of landscape enhancement through direct experience and technological advances that can broaden the prospects for research and community involvement. In fact, the methodological framework could be implemented within participatory processes for the implementation of landscape awareness in the Phlegraean area, providing a geo-database that can be updated on multiple levels, both by citizens and by technicians and academics.

Author Contributions

The paper has been jointly developed by all authors. Specifically, A. Acierno has written paragraph 1, A. Pagliano has written paragraph 5, I. Pistone has written paragraphs 2 and 4. The methodology and conclusions are joint work by all authors.

Funding

This research was funded by the PNRR project aimed at promoting the resources of the Phlegraean area in a strategic way for local development and entitled: Changes “Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Sustainable Society“ “PE5. Humanities and cultural heritage as laboratories of innovation and creativity” Spoke 1 – Historical Landscapes, Traditions and Cultural Identities WP4 – Strategies of interventions on historical landscapes Codice progetto MUR: PE00000020 – CUP E53C22001650006

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Terkenli, T.S.; Skowronek, E.; Georgoula, V. Landscape and Tourism: European Expert Views on an Intricate Relationship. Land 2021, 10(3). [CrossRef]

- Radomskaya, V.; Bathi, A. Examining the legitimacy landscape of the right to tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives 2025, 57. [CrossRef]

- Terkenli, T.S. Tourism and Landscape. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Tourism, Hall C.M.; Wiley: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2024; pp. 161-165. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Maskivker, G.; Fornells, A.; Teixido-Navarro, F.; Pulido, J.I. Exploring mass tourism impacts on locals: A comparative analysis between Barcelona and Sevilla. European Journal of Tourism Research 2021, 29(2908), pp. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Greer, C.; Donnelly, S.; Rickly, J. Landscape Perspective for Tourism Studies. In Landscape, Tourism, and Meaning; Knudsen, D.C., Soper, A.K., Metro-Roland, M.M., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing/Taylor & Francis: Farnham, Surrey, United Kingdom, 2008; pp. 9–17. [CrossRef]

- Zekan, B.; Weismayer, C.; Gunter, U.; Schuh, B.; Sedlacek, S.; et al. Regional sustainability and tourism carrying capacities. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 339. [CrossRef]

- Pasková, M.; Wall, G.; Zejda, D.; Zelenka, J. Tourism carrying capacity reconceptualization: Modelling and management of destinations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Tourism Indicator System. ETIS toolkit for sustainable destination management. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Belgium, 2016. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2873/983087.

- Akhtar, N.; Khan, N.; Mahroof Khan, M.; Ashraf, S.; Hashmi, M.S.; Khan, M.M.; Hishan, S.S. Post-COVID 19 Tourism: Will Digital Tourism Replace Mass Tourism? Sustainability 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Russo, A.P. Anti-tourism activism and the inconvenient truths about mass tourism, touristification and overtourism. Tourism Geographies 2024, 26(8), pp. 1313–1337. [CrossRef]

- Valente, J.J.; Gannon, D.G.; Hightower, J.; et al. Toward conciliation in the habitat fragmentation and biodiversity debate. Landscape Ecology 2023, 38, pp. 2717–2730. [CrossRef]

- Jover, J.; Díaz-Parra, I. Who is the city for? Overtourism, lifestyle migration and social sustainability. Tourism Geographies 2022, 24(1), pp. 9–32. [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Fan, A.; Lehto, X.; Day, J. Immersive Digital Tourism: The Role of Multisensory Cues in Digital Museum Experiences. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2021, 47(6). [CrossRef]

- Benyon, D.; Quigley, A.; O’Keefe, B.; Riva, G. Presence and digital tourism. AI & Soc 2014, 29, pp. 521–529. [CrossRef]

- Hisschemöller, M.; Kireyeu, V.; Freude, T.; Guerin, F.; Likhacheva, O.; Pierantoni, I.; Sopina, A.; von Wirth, T.; Bojanić Obad Šćitaroci, B.; Mancebo, F.; Sargolini, M.; Shkaruba, A. Conflicting perspectives on urban landscape quality in six urban regions in Europe and their implications for urban transitions. Cities 2022, 131. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Y. Neighbourhood walkability: A review and bibliometric analysis. Cities 2019, 93(6), pp. 43-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.04.015.

- Speck, J. WALKABLE CITY: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time. North Point Press: New York, NY, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Gavrilidis, A.A.; Ciocănea, C.M.; Niță, M.R.; Onose, D.A.; Năstase, I.I. Urban Landscape Quality Index – Planning Tool for Evaluating Urban Landscapes and Improving the Quality of Life. Procedia Environmental Sciences 2016, 32, pp. 155-167. [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Wan, G.; Xu, L.; Park, H.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yue, W.; Chen, J. Walkability in urban landscapes: a comparative study of four large cities in China. Landscape Ecol 2018, 33, PP. 323-340. [CrossRef]

- Urrutia-Reyes, C.A.; Cruz-Cárdenas, G.; Lina-Manjarrez, P. et al. Urban landscape elements for better walkability in Xalapa’s historic circuit, Mexico. GeoJournal 2025, 90(92), pp. 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. Planning for Walkability in Johannesburg. In Transport and Mobility Futures in Urban Africa, Acheampong, R.A., Lucas, K., Poku-Boansi, M., Uzondu, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 245-258. [CrossRef]

- Elzeni, M.M.; ELMokadem, A.A.; Badawy, N.M. Impact of urban morphology on pedestrians: A review of urban approaches. Cities 2022, 129. [CrossRef]

- Bruzzese, A. Improving Walkability in the City: Urban and Personal Comfort and the Need for Cultural Shifts. In New Challenges for Sustainable Urban Mobility: Volume I. ECOOP 1987, Tira, M., Tiboni, M., Pezzagno, M., Maternini, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 171–182. [CrossRef]

- Sabesan, L.; Meetiyagoda, L.; Rathnasekara, S. Landmarks and walkability: wayfinding during nighttime in a tourism-based city. Case study of Jaffna, Sri Lanka. GeoJournal 2024, 89(212). [CrossRef]

- Cecik, M. Transect - A 21st Century Urban Design Tool. In 1st International Conference on Urban Planning - ICUP2016, 97, Mitkovic, P., Ed.; Faculty of Civil engineering and Architecture, University of Nis: Nis, Serbia, 2021; pp. 87-96. Nis: Faculty of Civil engineering and Architecture, University of Nis.

- Han, S. The use of transects for resilient design: core theories and contemporary projects. Landscape Ecology 2021, 36, pp. 1567–1582. [CrossRef]

- Hemmersam, P.; Morrison, A. Place mapping - Transect walks in Arctic urban landscapes. SPOOL - Journal of Architecture and the Built Environment 2016, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Tixier, N.; Melemis, S.; Brayer, L. Urban Transects. In R.L.Hayes, In The Place of Research / The Research of Place: Proceedings of the ARCC/EAAE 2010 International Conference on Architectural Research, V. Ebbert, Ed.; Architectural Research Centers Consortium (ARCC): Washington D.C., Washington, 2010; pp.1-8.

- Mariotti, A. Local System, Networks and International Competitiveness: from Cultural Heritage to Cultural Routes. Almatourism – Journal of Tourism, Culture and Territorial Development 2012, 3(5), pp. 81–95. [CrossRef]

- Pultrone, G. Transition Pathways and Cultural Itineraries for Sustainable, Resilient and Inclusive Tourism. In Networks, Markets & People. NMP 2024. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 1184, Calabrò, F., Madureira, L., Morabito, F.C., Piñeira Mantiñán, M.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 266-275. [CrossRef]

- Beltramo, S.; Cultural Routes and Networks of Knowledge: the Identity and Promotion of Cultural Heritage. The Case Study of Piedmont. Almatourism – Journal of Tourism, Culture and Territorial Development 2013, 4(7), pp. 13–43. [CrossRef]

- Cardia, G. Routes and Itineraries as a Means of Contribution for Sustainable Tourism Development. In Innovative Approaches to Tourism and Leisure. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics, Katsoni, V., Velander, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 17-33. [CrossRef]

- Shields, R.; Gomes da Silva, E.J.; Lima e Lima, T.; Osorio, N. Walkability: a review of trends. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 2021, 16(1), pp. 19-41. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P., Ed. Geospatial Technology and Smart Cities. ICT, Geoscience Modeling, GIS and Remote Sensing. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ivan, I.; Singleton, A.; Horák, J.; Inspektor, T., Eds. The Rise of Big Spatial Data. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kerski, J.J. Geo-awareness, Geo-enablement, Geotechnologies, Citizen Science, and Storytelling: Geography on the World Stage. Geography Compass 2015, 9(1), pp. 14-26.DOI. [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, V.; Ragia, L.; Nomikou, P.; Bardouli, P.; Lampridou, D.; Ioannou, T.; Kalisperakis, I.; Stentoumis, C. (2018). Creating a Story Map Using Geographic Information Systems to Explore Geomorphology and History of Methana Peninsula. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2018, 7(12). [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J.; Lättman, K.; van der Vlugt, A.L.; Welsch, J.; Otsuka, N. (2022). Determinants and effects of perceived walkability: a literature review, conceptual model and research agenda. Transport Reviews 2022, 43(2), pp. 303–324. [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A. Collaborative spatial learning for improving public participation practice in Indonesia. University of Twente, Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation (ITC): Twente, Netherlands, 2021.

- Pillai, J. Cultural Mapping: A Guide to Understanding Place, Community and Continuity; Strategic Information and Research Development Centre: Penang, Malaysia, 2022.

- Clark, K. 1985). Il paesaggio nell’arte. Garzanti: Milan, Italy, 1985.

Figure 1.

Mass tourism phenomenon in Rome. This phenomenon prevents common users from freely enjoying the landscape and may alter the identity value of cultural assets (from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC0, author: W.R. Rodriguez Hernandez, 2024).

Figure 1.

Mass tourism phenomenon in Rome. This phenomenon prevents common users from freely enjoying the landscape and may alter the identity value of cultural assets (from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC0, author: W.R. Rodriguez Hernandez, 2024).

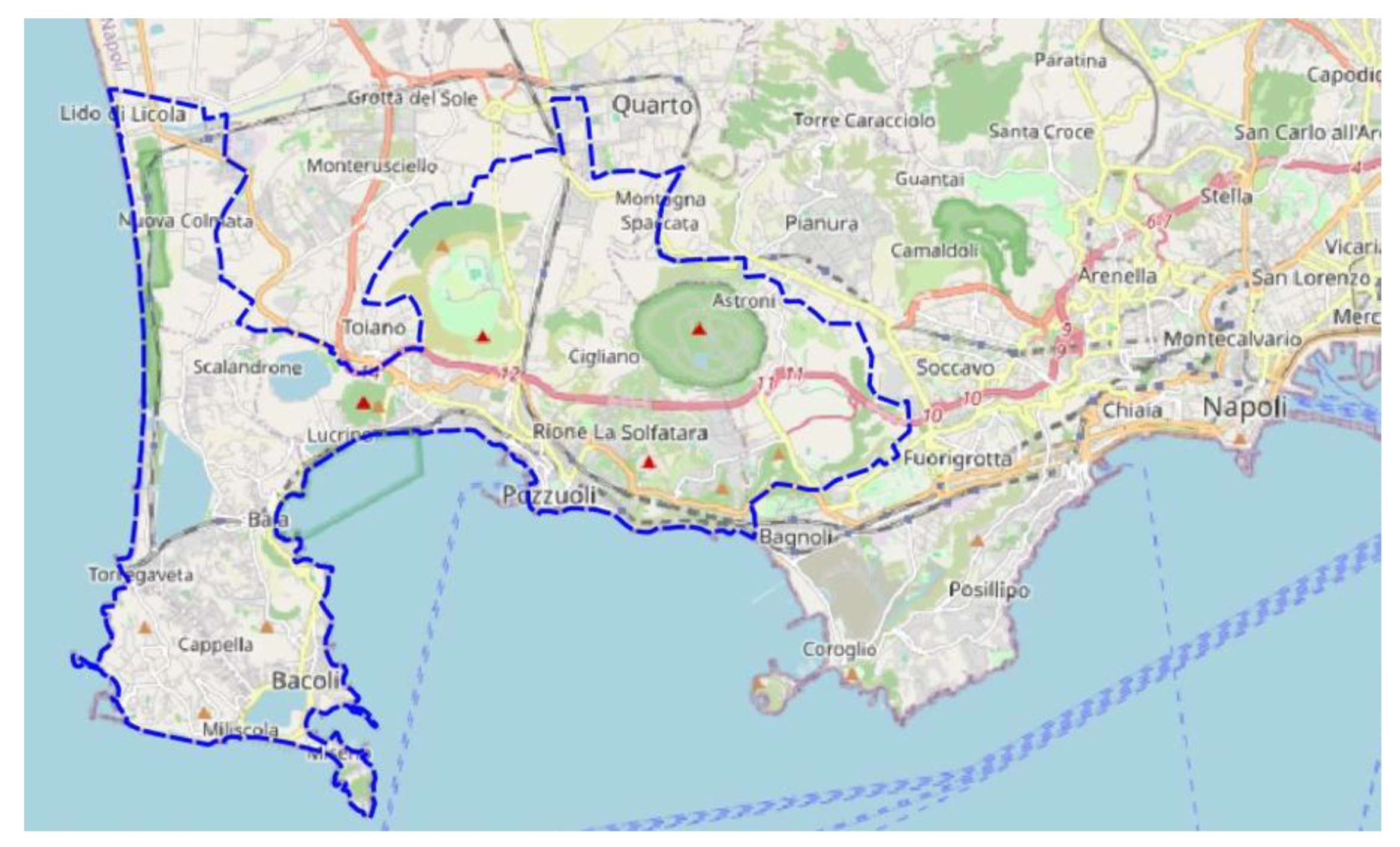

Figure 2.

The case study of the Phlegrarean Fields. Despite the proximity to the main city of Naples, this area suffers from scarce accessibility, while hosting large number of tourists due to its ecologicl and archaeological features (elaboration of A. Acierno).

Figure 2.

The case study of the Phlegrarean Fields. Despite the proximity to the main city of Naples, this area suffers from scarce accessibility, while hosting large number of tourists due to its ecologicl and archaeological features (elaboration of A. Acierno).

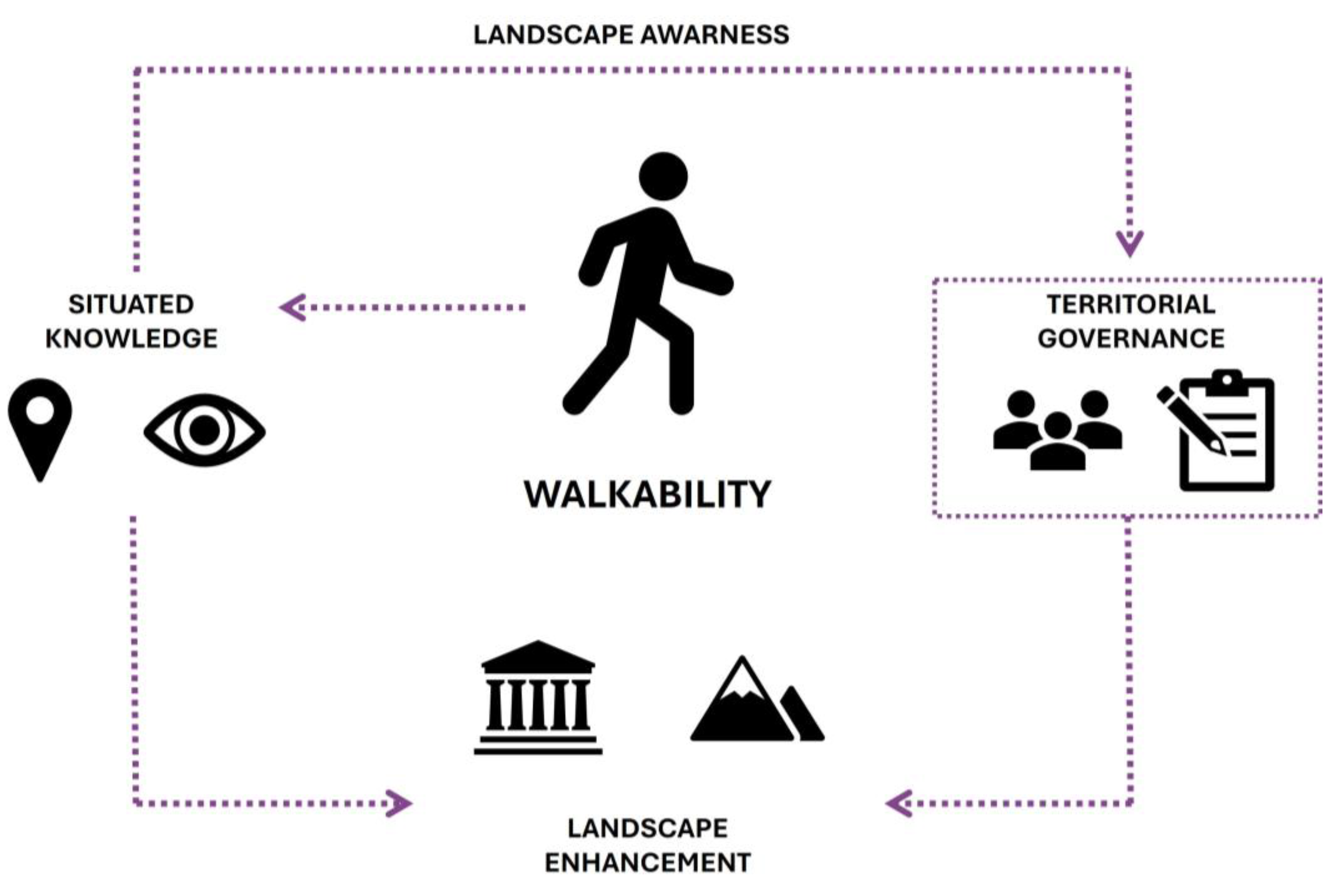

Figure 3.

Walkability may be intended as a way to channel community awareness of landscape in efficient governance and planning dynamics (elaboration of I. Pistone).

Figure 3.

Walkability may be intended as a way to channel community awareness of landscape in efficient governance and planning dynamics (elaboration of I. Pistone).

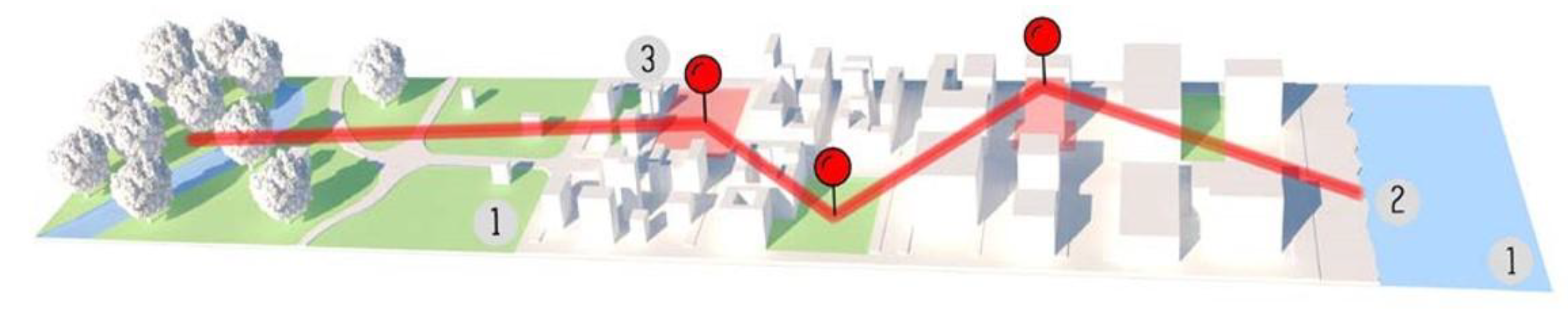

Figure 4.

The experiential transect is a tool for understanding the territory in each of its parts, as every movement is linear and involves direct contact with the landscape (elaboration of I. Pistone).

Figure 4.

The experiential transect is a tool for understanding the territory in each of its parts, as every movement is linear and involves direct contact with the landscape (elaboration of I. Pistone).

Figure 5.

Map of the analysed transects (in red) within the study area (elaboration of I. Pistone).

Figure 5.

Map of the analysed transects (in red) within the study area (elaboration of I. Pistone).

Figure 6.

Example of graphic representation of road sheets related to the Baia-Fusaro area, showing the existing degree of public lighting. The routes are linked to the presence of services or ecological-cultural assets (elaboration of I. Pistone).

Figure 6.

Example of graphic representation of road sheets related to the Baia-Fusaro area, showing the existing degree of public lighting. The routes are linked to the presence of services or ecological-cultural assets (elaboration of I. Pistone).

Figure 7.

The co-mapping platform elaborated for the research on Google My Maps. Users pinned elements divided by categories (elaboration of I. Pistone).

Figure 7.

The co-mapping platform elaborated for the research on Google My Maps. Users pinned elements divided by categories (elaboration of I. Pistone).

Figure 8.

Some of the results of the social survey. Slow mobility is a strong desire of the community but there is also the priority of maintaining the routes (elaboration of I. Pistone).

Figure 8.

Some of the results of the social survey. Slow mobility is a strong desire of the community but there is also the priority of maintaining the routes (elaboration of I. Pistone).

Figure 9.

Three-dimensional view of the Phlegraean Fields: the digital storytelling tool provides an immersive experience that integrates the physical experience (elaboration of A. Pagliano).

Figure 9.

Three-dimensional view of the Phlegraean Fields: the digital storytelling tool provides an immersive experience that integrates the physical experience (elaboration of A. Pagliano).

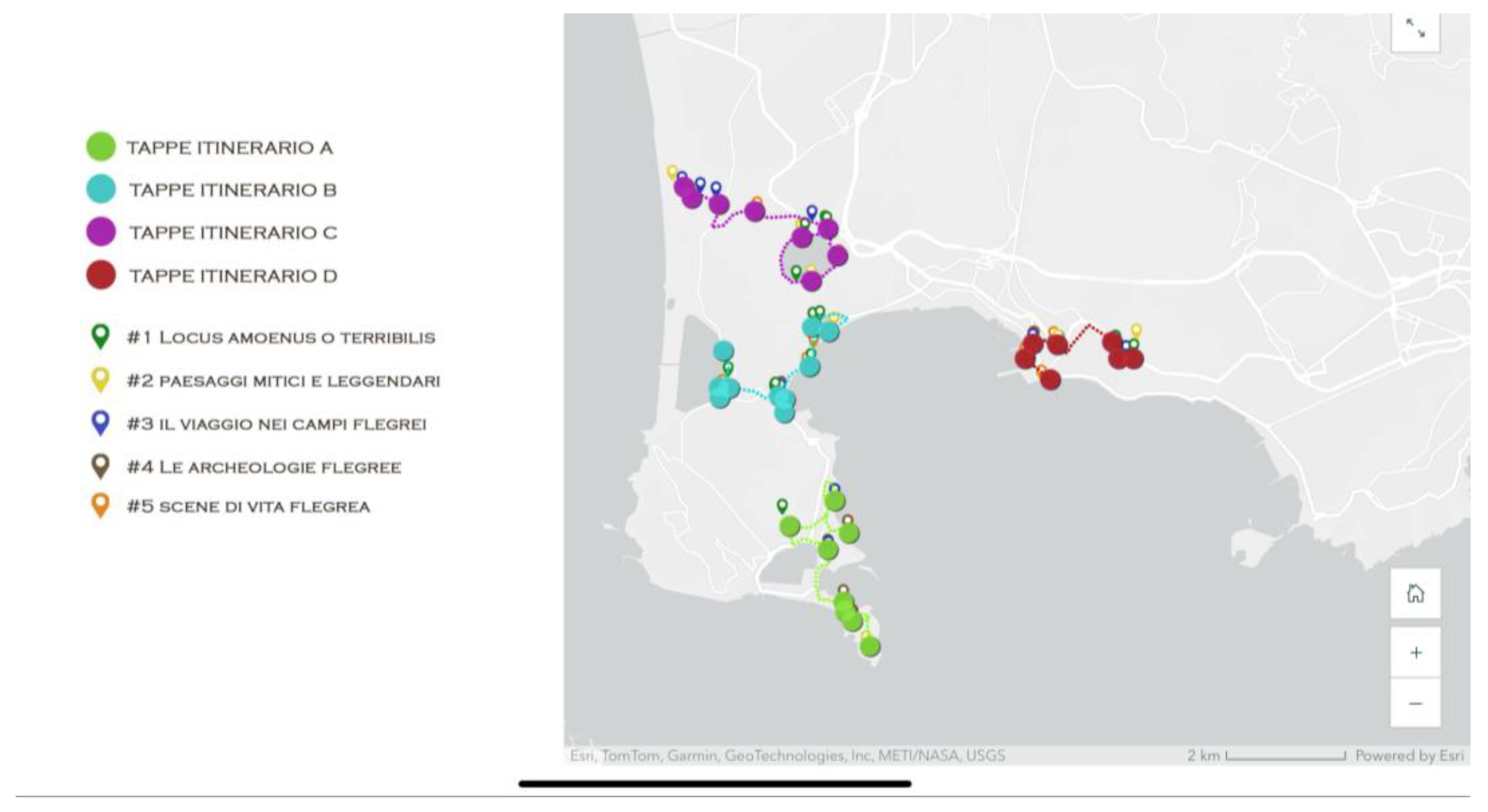

Figure 10.

The three routes that have been identified and further implemented on ArcGIS Storymaps in the form of digital geo-storytelling (elaboration of A. Pagliano).

Figure 10.

The three routes that have been identified and further implemented on ArcGIS Storymaps in the form of digital geo-storytelling (elaboration of A. Pagliano).

Figure 11.

Comparison between past and present landscape. On the left, View of Baiae with the Temple of Diana (painting by Carlo Bonavia, 1770); on the right, Temple of Diana in Baiae (photograph by Mario Ferrara, 2023) (elaboration of A. Pagliano).

Figure 11.

Comparison between past and present landscape. On the left, View of Baiae with the Temple of Diana (painting by Carlo Bonavia, 1770); on the right, Temple of Diana in Baiae (photograph by Mario Ferrara, 2023) (elaboration of A. Pagliano).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).