1. Introduction

The sustainability of European industry requires sustainable and environmentally friendly extractive activity in Europe, so that the European Union (EU) industry does not depend entirely on foreign sources and, consequently, overcomes the risks of outsourcing. This is the core idea of the Raw Materials Initiative [

1], after decades without a European policy for mineral resources. One of the pillars of this initiative focuses on the supply of mineral resources from domestic sources and highlights the importance of ensuring access to them, which points to the role of land use planning (LUP) for mineral policy. For the first time it was formally acknowledged the existence of many uncharacterized and unexplored mineral deposits in Europe and an existing economic and regulatory climate that, combined with a growing land use competition, limits the exploitation of the known deposits [

2].

Indeed, as noted by [

3], mineral resource governance is embedded in two policy fields: mineral policy and land use planning policy. This has relevance because LUP interconnects several competing land uses, such as urban sprawl, infrastructures development and nature protection, amongst others, that may have a negative effect on the available area for exploration and exploitation of mineral resources. Furthermore, LUP also links all of this to a social will that, although advocating a sustainable society, tends to be averse to all types of extractive activities, especially minerals. This is broadcasted almost daily through the media, being also the subject of several studies [

4,

5,

6,

7].

In this context the supply of mineral raw materials from domestic sources to European industry is at risk, calling for the need for minerals safeguarding [

8], which is a recent aspect of mineral resource governance that integrates mineral and LUP policies [

3,

9,

10,

11].

The criteria for defining which European mineral deposits deserve to be safeguarded and how to integrate mineral and LUP policies with a view to safeguarding these deposits were topics widely discussed in two relatively recent European projects: Minatura2020 – Mineral Deposits of Public Importance (

https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/642139) and Minland – Mineral Resources in Sustainable Land-Use Planning (

https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/776679). Several results have been achieved regarding the need to safeguard mineral deposits in Europe, which is to say, the need to ensure that mining companies have access to the European land where mineral deposits occur [

11,

12,

13] or there are reasonable prospects for their occurrence [

14,

15,

16].

The EU has been suffering consecutive losses of strategic autonomy and competitiveness since the beginning of the century [

17,

18,

19], which were exposed to public opinion with Russia's invasion of Ukraine. These losses refer to military defence issues, but also to the most varied fields of economic policy that are currently covered by the Green Deal umbrella policy. However, although not yet fully and frontally assumed, all these policies are mostly based on a common strategic basis: the need to ensure the supply of mineral raw materials.

The recently approved Critical Raw Materials Act [

20] reflects the EU’s acknowledgement that the soft policies aimed at promoting the supply of mineral raw materials from endogenous European sources, over the last two decades, have failed. An illustrative example is the set of countless recommendations that have accompanied the periodic raw materials’ criticality assessments carried out in Europe since 2010 (e.g., [

21,

22]).

Portugal is one of the EU countries where there are strong expectations for the extraction of Li ore, as well as other raw materials to support the energy transition in Europe [

19]. Therefore, being important to know to what extent these resources are available for mining exploitation, the main objective of this paper is to verify how mineral resources are safeguarded in the Portuguese land use planning practice. However, to understand it, a comprehensive knowledge of the underlying safeguarding concepts and legislative framework is necessary, which is why we start to present i) how minerals safeguarding is contextualized within the land use planning process and positioned in the life cycle of mineral projects; ii) an analytical summary of the mining and land use planning legislations; and iii) an analytical summary on the general practice of land use planning for minerals and on the role of the Portuguese geological survey. Finally, we present the current status of mineral safeguarding in Portugal through an analysis of data collected from a sample of the Municipal Master Plans currently in force, which are the land use planning tools with concrete effectiveness on the ground.

Background on the Minerals Safeguarding Concept

Taking that spatial planning and LUP are, in essence, the same thing [

23], LUP can be defined as the process of strategically organizing and regulating land development to reduce risks and promote economic, social, and environmental benefits [

24].

The importance of LUP for mineral resource governance was long time ago recognized [

25]: To secure the long-term supply of mineral resources to society there is a need to protect mineral resources from being sterilised during the LUP process, i.e., the loss of the option to exploit them.

Despite its literal interpretation, mineral resources safeguarding (Minerals Safeguarding) takes place during LUP and is the process of ensuring that areas containing or potentially containing mineral deposits are not needlessly occupied by other uses that may prevent their future extraction, including the places for installing mining/quarrying infrastructures [

8,

26]. Furthermore, it is widely accepted that mineral resources with an already known economic value are those that will supply the society in a near future, and many of the areas where they occur are already protected by some kind of land use easement (e.g., mining concessions). Hence, the long-term supply of the society depends on the undiscovered or poorly defined resources [

27,

28,

29,

30], which will only be mineable if the areas where they occur are also protected from unnecessary sterilisation. This means that areas currently containing non-economic and/or not yet enough studied resources, and promising target areas should also be considered in LUP in addition to known mineral deposits [

15,

16].

After Pendock’s recognition of the importance of LUP to prevent the sterilization of mineral resources [

25], this issue was not widely discussed in the literature. Attention has been paid mainly to the sustainability of the mining industry and its indicators [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35], and methodologies to assess the impact of mining activities [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. On the other hand, while repeatedly mentioning that the protection of mineral resources during the LUP process is a critical issue, the scientific literature has focused on geological, technological and economic discussions about quantitative mineral potential assessment methodologies [

27,

41,

42,

43,

44], and, more recently, on discussions about the scarcity and risk of supply, driven by concerns about a growing world population, the energy transition, and the social license to operate in a world competing for minerals [

7,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52].

The consideration of minerals in LUP is addressed mostly in policy documents and legislative acts regarding the management of national mineral resources and LUP itself. The most paradigmatic example comes from the United Kingdom where Minerals Safeguarding is a concept born on legislative acts for LUP, and it is being applied as guidance at all planning levels since 2006 [

8,

53]. More recent examples include the Austrian Mineral Resources Plan [

54] and the European policy documents on the need to safeguard minerals in land use planning, as is the case of the “Recommendations of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Exchange of Best Practices on Minerals Policy and Legal Framework, Land-Use Planning and Permitting”, which emphasises that accessibility to mineral resources in land use planning should remain unimpeded in order to avoid their sterilisation [

55].

Specifically, regarding scientific literature that focuses on the integration of mineral resources in LUP, three groups can be distinguished:

One strand of literature focusing on the spatial management of areas already designated for mineral developments by providing the background information to detailed land use plan maps [

56,

57,

58]. Based on a cross-case study research in Spain, some authors conclude that there is no universal way to address this issue [

59].

A second strand of literature mainly presents methodologies for the identification of favourable locations for the mining industry where conflicts with other uses of land are on a low level or minimal [

60,

61,

62,

63]. They assess the spatial extent of economically valuable mineral deposits after subtraction of the areas for which LUP already prohibits mining activities or for which strong land use conflicts are expected. The Austrian Mineral Resources Plan [

54] is the main example of application of this kind of methodologies.

The third strand of literature illustrates comprehensive methodologies addressing the valorisation of mineral resources regardless of any potential land-use conflicts. This strand of literature refers to the multi-criteria assessment methodologies such as proposed by [

14,

64,

65]. Their primary objective is to identify mineral deposits deserving to be safeguarded in land use planning and to delimit their respective Mineral Safeguarding Areas, i.e., areas where minerals are to be protected from unnecessary sterilization. The Swedish Deposits of National Interest [

66] and the Norwegian Consideration Zones for mineral deposits [

67] result from the application of such kind of methodologies.

What is especially important to remember is that in the so-called mineral resources value chain, interactions with LUP take place in the following stages:

Development and implementation of LUP policies and legislation.

Permitting for exploration (if a permit is required, which depends on the country).

Permitting for exploitation (concession, licensing, or another legal tool).

Rehabilitation (in what respects the reclamation for other land uses).

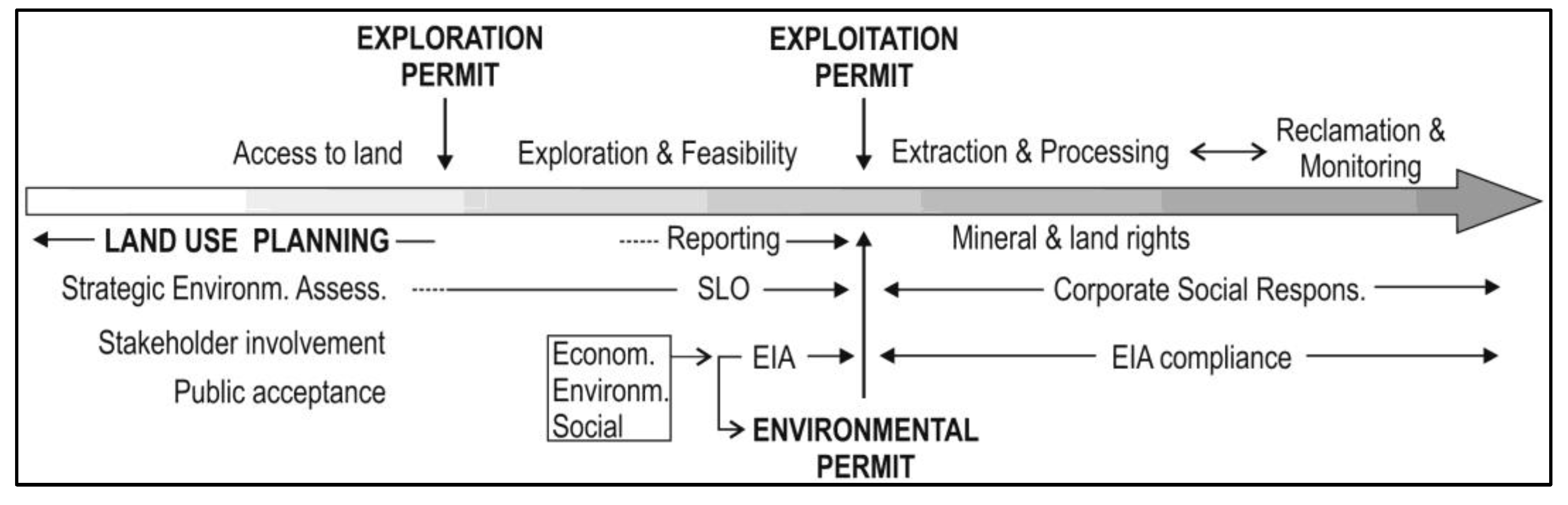

This is depicted by

Figure 1, which outlines the timing of many of the legal procedures and actions that may significantly affect mineral developments. The Exploration Permit allows a mining company to get access to land to conduct exploration works. If the exploration and the mining feasibility studies give positive results, then the awarding of a mining concession depends mainly on the Environmental Permit (a decision-making tool), which is obtained through an Environmental Impact Assessment process (a decision-aiding tool). This assesses not only the environmental and economic issues, but also the social ones, the latter being strongly conditioned by previous actions taken by the mining company with the local population and local authorities to obtain the so-called Social License to Operate.

Yet, whether all these procedures and actions are carried out depends on whether mining companies have access to the land to conduct exploration and exploitation, which is decided during the LUP stage, well before the start of any mining development project, that is, before granting the exploration permit. Therefore, the LUP decision-making process is critical to ensure access to land for mineral resource exploration and exploitation activities.

In short, for a mineral deposit to be discovered, access to land must be established in advance. Hence, there is no rational that can support LUP decisions that interdict access to minerals without a prior judgment on an equal footing with other competing interests. If extracting them is economically viable and an exploitation permit is requested, this becomes a matter of Environmental Impact Assessment, not of LUP.

2. The Legislative Framework for Minerals and Land Use Planning in Portugal

To understand the current mineral resource governance practice in Portugal, a compilation (

Table 1) and analysis of the existing legislation for mineral resources and LUP was made, focused on identifying the provisions relevant for the protection of mineral resources and the existing interconnections between mining legislation and LUP. It is important to note that in the Portuguese legislative framework, a Law is a legislative act issued by Parliament, while a Decree-Law is issued by the government. Furthermore, although this article refers specifically to mineral resources, Portuguese legislative acts mainly refer to the broader concept of geological resources, and for this reason geological resources are often mentioned in this paper interchangeably.

2.1. Findings in Mineral Resources Legislation

2.1.1. The Ownership of Mineral Resources

Law 54/2015 is the Portuguese mining act. Following the Portuguese Constitution, among geological resources, the mining act distinguishes public domain from private domain mineral resources. The public domain minerals, i.e., stated owned mineral resources, are designated as Mineral Deposits and correspond to mineral occurrences which, due to their rarity, high specific value or importance in the application of the substances contained therein in industrial processes, are of special economic interest. Decree-Law 30/2021 specifies that Mineral Deposits are the economically relevant occurrences of mineral substances that can be used to obtain metals, semi-metals, non-metals and radioactive substances contained therein. In addition, this Decree-Law informs that the occurrences of rare earth elements, precious and semi-precious stones, talc, chalk, coals, graphite, diatomite, barite, pyrites, phosphates, asbestos, lithium minerals, quartz, beryl, micas, feldspars and feldspathoids, silica sands, special clays (kaolin, bentonite, refractory clays, ball clays and fibrous clays), and evaporites are also Mineral Deposits. All the other mineral occurrences are private assets and are called Mineral Masses (e.g., red clays, sand and gravel, limestones, and granites).

Besides mineral resources, Law 54/2015 also refers to other geological resources: natural mineral waters, industrial mineral waters and geothermal resources are the property of the Portuguese State and therefore concessions can be granted for their exploitation, while spring waters are private assets for which licenses for their exploitation can be issued.

2.1.2. Granting Rights Over the Public Domain Minerals

According to Law 54/2015 and details in Decree-Law 30/2021, the granting of rights over the state-owned minerals can take several forms, all of them subject to an administrative contract between the Portuguese State and the private party:

Voluntary one-year preliminary land evaluation of the existing mineral resources.

Exploration permitting with a maximum duration of 5 years. It may be the initiative of a private party or can be initiated through a public tender by the government. When requested by a private party, the granting of this right is accompanied by an administrative easement for the use of the requested area, but exploration activities are not allowed in the beds and banks of waterbodies and respective protection perimeters, nor within a 1 km perimeter around urban and rural agglomerations, unless a specific authorization is granted annually. When initiated by a public tender, all nature conservation areas (nature parks, Natura 2000 Network, Ramsar sites, etc.) must be excluded from the areas designated for competition.

Voluntary Experimental Exploitation permitting. It is issued for a maximum period of 5 years and may be preceded by an environmental impact assessment procedure. This permit also implies an administrative easement for the use of the requested area.

Exploitation permit (Mining Concession). It can be granted for a maximum of 90 years and only to those who discovered the resources in one of the previous stages and, again, before issuing a mining concession, consultations with other authorities are mandatory. The granting of a mining concession depends on the existing provisions in land use planning tools, administrative easements and public utility restrictions, and must comply with the conditions imposed by an Environmental Impact Assessment. The holders of a concession may require an administrative easement for the exploitation of the resources, and the concession contract itself may include provisions for the exclusive use of land.

2.1.3. Granting Rights to Privately Owned Minerals

The granting of rights over the private domain minerals is subject to a licensing procedure, which can only be issued to the owner of the land or to whom has a lease agreement with the owner. Still according to the mining act and details in Decree-Law 270/2001 and respective amendments (Decree-Law 340/2007), there are two types of licenses:

Voluntary exploration permit – one-year validity, but with the possibility to be extended one more year. Issuing an exploration license depends on the compatibility provisions in the land use planning tools.

Exploitation Permit (License) – 4 years validity, but renewable for similar periods of time. In an initial stage, it depends on a formal consent from the Land Use Planning authority and, in a final stage, on the approval and conditions imposed by an environmental impact assessment procedure, which, once again, assesses whether the area required for extraction complies with the provisions of land use planning tools. After approval of the license, administrative easements may be imposed on the exploitation area to protect the mineral resources.

2.1.4. Integration with Land Use Planning Policy

For spatial planning purposes, the Portuguese mining act specifies that the geological resources policy should be expressed by sectoral programmes according to the law 31/2014. It also specifies that intermunicipal and municipal land use plans must include provisions for the integration of the areas for the exploitation of geological resources and that these plans must respect the existing sectoral programmes for geological resources.

Although the mining act was published ten years ago, no sectoral programme for geological resources has been designed to date.

2.2. Findings in Land Use Planning Legislation

2.2.1. The Land Management Framework

In a top-down approach, Law 31/2014 governs the soil and spatial planning policy in Portugal through a hierarchical network of land use planning tools, which consist of programmes and plans, the most decisive ones being presented in

Table 2. The former bind the public entities and establish the strategic framework for land development, its programmatic guidelines, and define the spatial effect of national policies to be considered at each planning level. The plans, on the other hand, bind public entities, private parties and individuals by establishing concrete options and actions in terms of planning and organization of the land, as well as defining the way it will be used (Law 31/2014).

Facultative intermunicipal programmes and plans, as well as Urban Plans and Detail Plans, also do exist aiming the strategic management and planning of intermunicipal communities, and the detailed planning of specific urban or rural areas.

2.2.2. The Classification of the Land

According to the general law (Law 31/2014), land is classified as rural land or urban land within the scope of intermunicipal and municipal plans. Rural land is land with recognized suitability for i) agricultural, livestock or forestry use; ii) the conservation, valorisation and exploitation of natural resources, geological resources or energy resources; iii) cultural, touristic-related, and risk protection uses, even if occupied by infrastructures; and iv) land which is not classified as urban. On the other hand, urban land is the land that is totally or partially urbanized or built on. It is worth noting that geological resources are not considered to be natural resources, as they are taken separately along with energy resources.

2.2.3. The Qualification of the Land

The qualification systematics for rural land comes from Decree-Law 80/2015. It specifies that the qualification is carried out through zoning of land into categories of dominant use, namely the following:

Agricultural spaces.

Forest spaces.

Spaces for the exploitation of energy and geological resources.

Spaces allocated to industrial activities directly linked to the aforementioned uses.

Natural spaces and those of cultural and scenic value.

Spaces intended for infrastructures or other types of human occupation, if they do not imply a classification as urban land (e.g., rural agglomerations, cultural spaces).

The criteria for this zoning according to dominant uses is established by the Regulatory Decree 15/2015, which also details a little more, the above-mentioned land categories. Essentially, the criteria refer to the need to comply with the options taken in the territorial programs that are in force, the prevention of natural and anthropogenic risks and respect for the current dominant use but developing the multifunctional use of the land. This regulatory decree also allows the division of the categories into subcategories.

2.2.4. The Municipal Master Plan (PDM)

The municipal master plan is the most important land use planning tool because, being mandatory, it defines the strategic framework for the development of the respective municipality and the corresponding spatial organization model through the classification and qualification of land. According to Decree-Law 80/2015, it also establishes the rules for the use and occupation of the land, considering the strategies drawn up at national and regional levels, as well as the existing sectoral programmes (e.g., National Water Plan and Natura 2000 Network Sectoral Plan), special programmes (e.g., programmes for public water reservoirs and programmes for each nature protected area), and all the existing easements and public utility restrictions from which the National Agricultural Reserve and the National Ecological Reserve are most relevant due to the vast areas they encompass.

Decree-Law 80/2015 establishes that each PDM must ensure the necessary compatibilities with all these programmes, easements and restrictions. Therefore, the PDM is a heavy and hard planning tool that congregates a wide range of studies and analyses at the municipal level, which represents in depth knowledge and capacity building for the municipality. Decree-Law 80/2015 specifies that each PDM consists of:

A regulation document.

A land use planning map (i.e., a zoning map) depicting the classification and qualification of the land at 1:25000 scale, as well as the areas respecting special and sectoral programmes.

A map of easements and public utility restrictions (Map of Constraints), that may constitute limitations or impediments to any specific form of land use.

Besides initial studies for the biophysical, social and economic characterization of the municipal territory, these main documents are supported by a general report, an environmental report resulting from a strategic environmental assessment, an execution programme, and a financing program. In the final stage of the PDM elaboration, each municipality submits the most relevant documentation to public discussion.

2.2.5. How Are Mineral Resources Addressed?

In this context of land use planning tools, mineral resources are not distinguished from other geological resources and are addressed together with energy resources. For the sake of simplicity, we refer only to geological resources.

Decree-Law 80/2015 and Regulatory Decree 15/2015 replicate Law 31/2014 regarding the criteria for the classification of land as rural land, one of which is the recognized suitability for the conservation, valorisation and exploitation of geological resources. When it comes to the qualification of the rural land, these legislative acts have a slightly different approach to that of the main law. They state that the municipal land use plans must delimit and regulate the areas allocated to the exploitation of geological resources, integrating them into a category called Spaces for the Exploitation of Geological Resources (SEGR).

This small difference in language between the geological suitability criterion used to classify land as rural and the one used to integrate land into the SEGR category raises the question of whether this category includes all the areas with recognized suitability for the exploitation of geological resources or only those where extraction actually takes place. As will be seen and discussed later, this has serious implications on the interpretations made by LUP practitioners with severe consequences for minerals safeguarding.

Unlike what is recommended for other land categories, these regulatory documents specify that the rules for this land use category must ensure the minimization of environmental impacts, compatibility of uses, and landscape restoration.

Geological resources and, consequently, the narrower group of mineral resources, are also addressed in two other land use categories, namely the agricultural spaces and forest spaces, for which compatibility with the exploitation of geological resources is foreseen.

Indirectly related to geological resources, Law 31/2014 also addresses the concession for the use and exploitation of public domain assets as well as the administrative easements. It establishes that the Portuguese state may enter into concession contracts for the private use of public domain assets. This legally frames the concessions for the exploitation of state-owned mineral deposits and the establishment of administrative easements to both public and private domain minerals.

3. Land Use Planning Practice for Minerals in Portugal

Currently, all the 278 municipalities of Portugal mainland have their respective PDM in force. The majority (62.8%) have already gone through a first revision process and a minor part (5.8%) through a second revision. The legislation does not establish a validity period for the PDM, but states that each one must be revised when changes in environmental, socioeconomic, and cultural conditions determine modifications to the current LUP model.

The PDM revision procedure is equivalent to the elaboration of a new plan. Due to its complexity, PDM revision procedures are usually very slow and lengthy, with an average time of 9 years [

68]. It involves the constitution of an Advisory Committee, whose composition is regulated by Ordinance no. 277/2015 (

Table 1), and the elaboration of a proposal by a multidisciplinary technical team. All produced documents are assessed by the advisory committee. A strategic environmental assessment runs parallel to the preparation of the proposal.

The Zoning Map is the graphic piece that reflects the strategic land use options. As the PDM must ensure compatibility with the higher order programs, in practice this means that the first land areas to be considered are those of sectoral and special programs in force.

Within the Advisory Committee, the topic of geological resources is assigned to the Portuguese mining authority (DGEG - Directorate General for Energy and Geology), which is responsible for providing data relating to the mining constraints in force and assessing the documentation that integrates the PDM proposal. Mining constraints to be considered are the areas allocated to concessions and licenses for the extraction of mineral, water, and geothermal resources, as well as the temporary areas allocated to the exploration and experimental exploitation of geological resources. These mining restrictions are drawn without modifications on the Map of Constraints of each PDM. During the last 5 years, DGEG has participated in about two hundred advisory committees (pers. comm.).

During the studies for the biophysical characterization of the municipal land, the collaboration of state departments and institutions, other than the ones integrating the Advisory Committee, may be requested. The same applies for the last stages of the PDM’s revision process, when a technical opinion on the compliance with legal requirements of the maps and other documentation that make up the PDM, may also be requested.

3.1. The Role of the Portuguese Geological Survey

Currently, the Portuguese geological survey is a department of LNEG, the National Laboratory for Energy and Geology. In addition to the systematic geological mapping, and among other responsibilities in the field of the geosciences, it is responsible for the inventory, characterization, and valorisation of national mineral occurrences, transferring knowledge about the country's mineral wealth to society.

Despite not integrating the advisory committee of each PDM revision procedure, LNEG is sometimes called upon to provide data for the biophysical characterization studies and to issue opinion on the legal compliance of the final PDM proposal. During the last 5 years, LNEG has been requested to provide data for 27 revision procedures and to issue an opinion relating to 24 final proposals. Compared with the 200 revision processes in which DGEG has participated, these numbers show that resorting LNEG is sporadic.

The scope of LNEG's intervention in the PDM is to promote the safeguarding of mineral deposits, namely through actions that prevent their sterilization, i.e., the loss of the option to exploit them by designating for incompatible uses the land where they occur, or there are reasonable prospects for their occurrence.

3.1.1. Data on Mineral Resources Provided by LNEG

When requested to provide data on geological resources, LNEG provides the existing data on mineral occurrences but also suggests that these data should be incorporated into PDM, according to a methodology already described in a report produced in the scope of the European project Minland. Named LUP-MR [

69], which is the improvement of a previous one developed by the Portuguese geological survey at the beginning of the century [

70], which foresees the subdivision of the Spaces for the Exploitation of Geological Resources into four land use subcategories to be considered in the Zoning Map, and respective provisions for the PDM’s Regulation (

Table 3).

It is clear that minerals safeguarding is effective through the implementation of complementary exploitation areas and potential areas.

3.1.2. LNEG’s Technical Opinions on the Compliance of PDM with Legal Requirements

In the last stage of some PDM revision processes, LNEG was requested to issue an opinion on the produced documentation, regarding its compliance with applicable legal and regulatory standards. The scope of the technical opinion to be issued is strongly limited, as only the verification of legal standards is required. Even with consequences for the planning strategy, any deficiencies found in biophysical characterization studies, including the failure to consider the mineral potential, can no longer be corrected, unless they also have legal or regulatory consequences.

Thus, LNEG's intervention in relation to mineral resources is focused on verifying the following: (i) The compliance of the Spaces for the Exploitation of Geological Resources outlined in the Zoning Map with the provisions of Decree-Law 80/2015, and (ii) the compliance of the PDM Regulation with the compatibility provisions of Regulatory Decree 15/2015 for agricultural and forest spaces.

4. Mineral Safeguarding in Municipal Master Plans: the Current Status

As mentioned before, LNEG's experience of the last five years is limited to issuing technical opinions on only 24 final PDM proposals, which does not allow for accurate recognition of how minerals are safeguarded. Furthermore, many of them have not yet been officially published, so their final content is unknown. Therefore, to better understand how mineral resources are currently safeguarded in LUP, data provided by the PDM in force were collected from a larger sample obtained from the National Territorial Information System (

https://snit-sgt.dgterritorio.gov.pt/igt) and the municipalities' websites.

As the most recent legislation for land classification and categorisation dates from 2015, the sampling focused on PDMs whose revision is later (year 2016) and up to the data collection deadline established for this work (end of March 2025). This deadline was established because the quantity of PDMs under revision is constantly being updated, making it necessary to limit the sampling process. In general, in the municipalities considered, the second revision process of the PDM was carried out, more rarely the third revision. All changes and modifications subsequent to the PDMs’ revisions were always considered, until the established deadline. For statistical purposes, it was considered the 2023 subdivision of Portugal into 7 regions (NUTS II): North, Central, West and Tagus Valey, Greater Lisbon, Setúbal Peninsula, Alentejo, and Algarve. For the sake of simplicity, the West and Tagus Valley, Greater Lisbon and Setúbal Peninsula regions are here taken as a whole under the obsolete but well-known name Lisbon and Tagus Valley region.

Under the aforementioned conditions, information was obtained on 57 municipalities out of a total of 278 in mainland Portugal, with the following distribution: 19 in the North region out of a total of 86; 11 in the Central region out of a total of 77; 9 in the Lisbon and Tagus Valley region out of a total of 52; 15 in the Alentejo region out of a total of 47; and 3 in the Algarve region out of a total of 16.

The PDM of each municipality was characterized by a set of parameters relating to the qualification of rural land that were taken from the respective zoning maps and regulatory documents. The respective maps of constraints were also used.

The analysis of the zoning map of each PDM focused on verifying how the Spaces for the Exploitation of Geological Resources (SEGR) were outlined considering the following:

As shown previously, national LUP legislation, particularly that of a regulatory nature, does not have straightforward provisions for minerals safeguarding. However, assuming that ensuring the compatibility of rural land with the extractive industry means that access to mineral resources (their safeguarding) is also guaranteed, the analysis of the PDM regulations focused on verifying this compatibility for categories of rural land other than the SEGR. Of these, agricultural and forest spaces, for which the legislation provides for compatibility with mineral extraction (Regulatory Decree 15/2015), and natural and landscape spaces are the most important due to the large areas they occupy. The analysis carried out considered the following variables:

Addressing/ignoring geological resources in the objectives and strategic options of the municipality.

Presence/absence of specific clauses regarding the SEGR.

Exploitation of geological resources allowed/forbidden in natural and landscape categories of land.

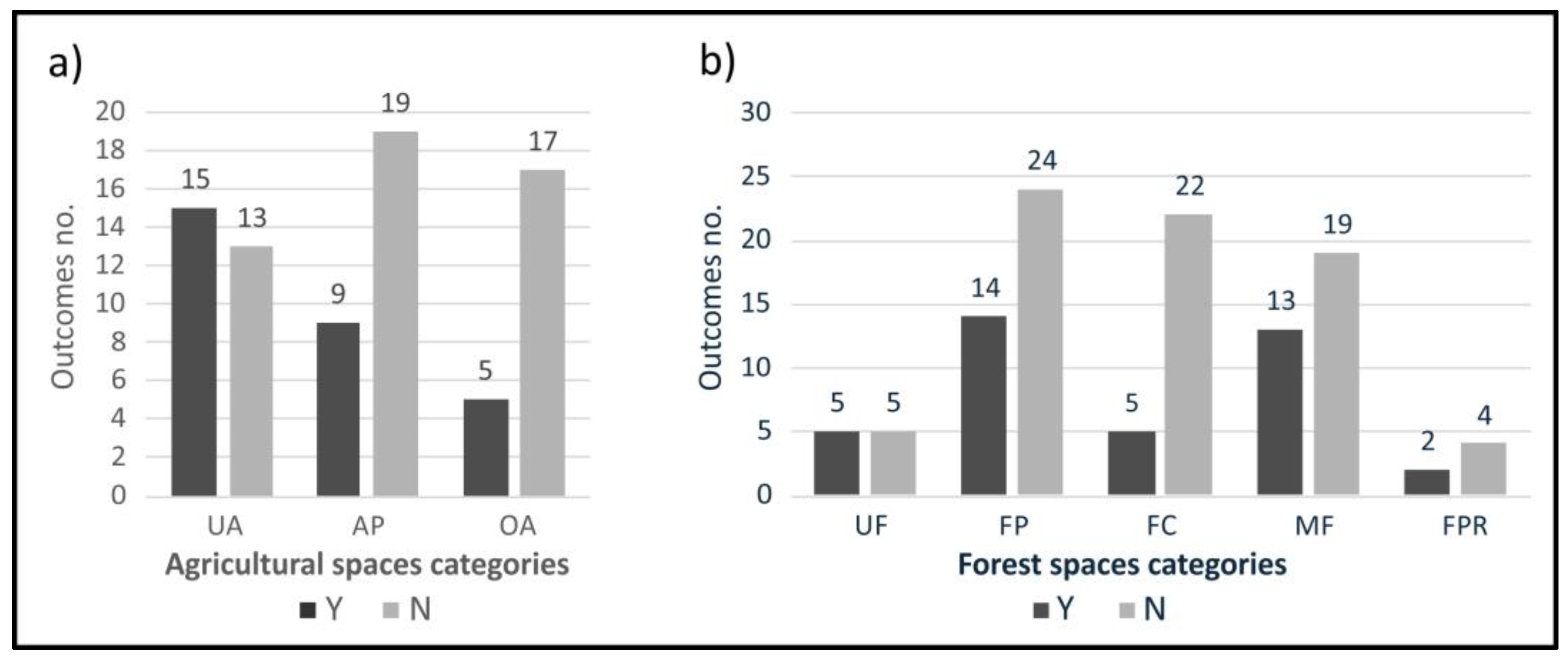

Exploitation of geological resources allowed/forbidden in agricultural land categories, which were subcategorized as Undifferentiated Agricultural areas (UA), Agricultural Production areas (AP), Agricultural Conservation areas (AC), and Other Agricultural areas (OA) (

Table 4).

Exploitation of geological resources allowed/forbidden in forest land categories, subcategorized as Undifferentiated Forest areas (UF), Forest Production areas (FP), Forest Conservation areas (FC), Mixed Forest areas (MF), and Forest Protection areas (FPR) (

Table 4).

5. Results and Discussion

The results obtained by a simple statistical analysis of the collected data allowed some straightforward interpretations on the way in which the SEGR were delimited in the zoning maps.

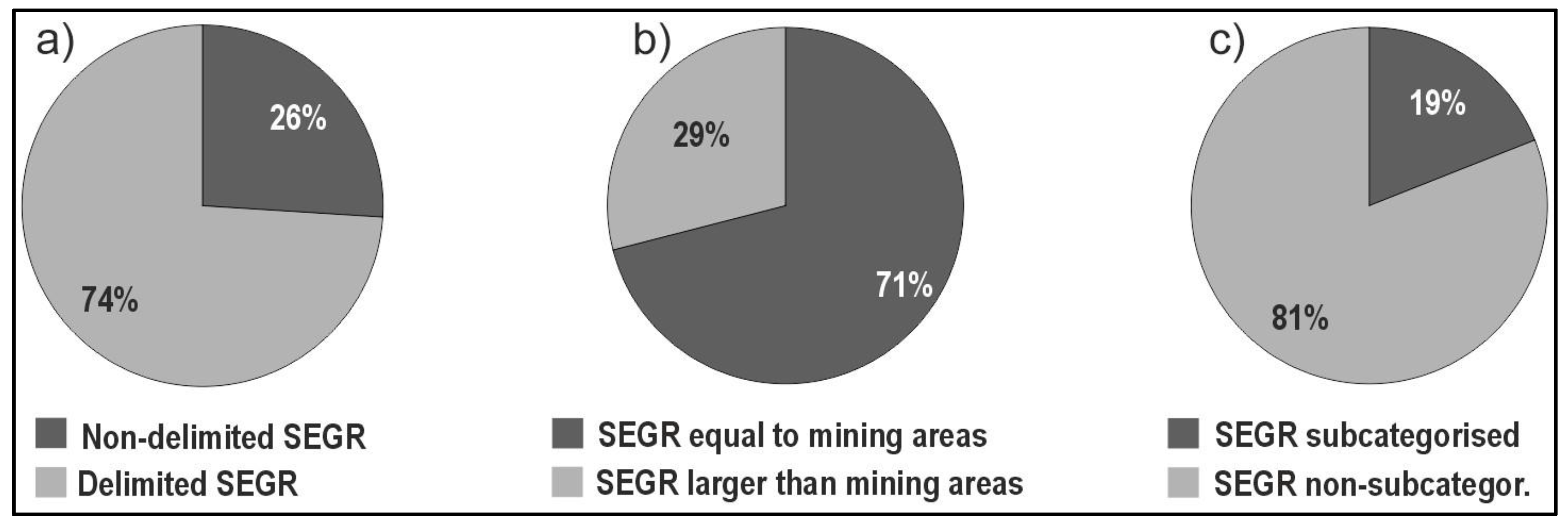

SEGR were not outlined in about one quarter of the zoning maps, which is a significant value, even considering that the sample includes 5 municipalities dominated by urban space (Aveiro, Porto, Matosinhos, Maia, and Espinho) (

Figure 2a). If not delimiting SEGR is understandable for these municipalities, in the remaining this may be due to political will or, simply, to lack of knowledge about the existence of mineral resources. In fact, as mentioned earlier, very few municipalities turn to LNEG during the initial PDM revision phase to obtain information on geology and mineral resources.

When comparing the SEGR with the granted mining areas outlined in the Map of Constraints,

Figure 2b shows that for most of the analysed municipalities (71 %) the areas are identical on both maps. Once again, this may be the result of simple political will to confine the extractive industry to these areas to prevent its development into larger areas or even other locations. Another possible interpretation, which seems more plausible, is the one that answers a question previously raised about the concrete meaning of the SEGR. Indeed, the result indicates that LUP technicians interpret the SEGR in a very restrictive way, that is, as corresponding only to the places where extraction actually occurs (as the name itself seems to indicate), not to areas with recognized suitability for the valorisation and exploitation of geological resources, which is one of the criteria for classifying land as rural. Therefore, SEGRs delimited in this restrictive manner cannot be considered as contributing to the safeguarding of mineral resources.

Most of the SEGR were outlined in the zoning maps as simple non-subcategorized areas (

Figure 2c). Again, this may be the result of municipalities not resorting to LNEG for specialized support on the integration of mineral resources into the PDM, particularly by adopting the subcategories presented in

Table 3, or it may simply be the result of choosing not to consider it. If these non-subcategorised SEGR are equal to the areas already granted for exploitation, then, once again, they do not serve minerals safeguarding.

A more in-depth analysis shows that among the zoning maps whose SEGR were subcategorized, the most common situation is the subcategorization into Consolidated Exploitation Areas and Potential Areas or into Consolidated Exploitation Areas and Complementary Exploitation Areas, depending on whether the mineral resources are state or private owned, respectively. In both cases, a direct match is made between the Consolidated Exploitation Areas and the existing excavations. However, when the minerals are state owned, a match is made between the Potential Areas and the concession area, excluding the excavations, whereas for privately owned minerals a direct correspondence is made between the licensed area and the Complementary Exploitation Area, also excluding excavations. All these inconsistencies result from a lack of knowledge about the real meaning of the subcategories proposed by LNEG (

Table 3).

The Regulation is one of the most important documents of each PDM. In addition to the regulatory provisions, it generally begins by presenting the municipality's development objectives and strategies. Therefore, the significance of mineral resources for municipalities can be expressed by their reference in this regulatory document. However, for the 57 analysed regulations, only 6 of them (≈ 10%) address minerals in the respective objectives or development strategies.

Regarding the compatibility of other categories of rural land with the exploitation of minerals, which is to say regarding the safeguarding of minerals, the analysis of the PDM’s regulations yielded interesting results.

For the so called Natural and Landscape Spaces the result is quite simple and instructive: The extraction of mineral resources in these areas is subject to very strict environmental restrictions and is only allowed in 5% of the analysed PDM.

A large part of the Natural and Landscape Spaces corresponds to areas covered by some type of nature protection regime (e.g., Natura 2000 Network, nature parks, National Ecological Reserve), which, in Portugal, do not follow the guidelines developed by the European Commission for the Natura 2000 Network decision-making framework, which underlines that there is no automatic exclusion of mineral extraction activities in or near Natura 2000 areas [

71]. As a matter of fact, the special and sectoral programs for nature protection include provisions for a ban on mineral extraction in most protected areas, which PDMs are required to comply with. Very recently, the situation has been worsening with specific legislation for certain sites of the Natura 2000 Network that, in addition to prohibiting the extraction of mineral resources in those sites, also requires PDM to prohibit exploration activities (e.g. Decree-Law 73/2025). From all this, we can infer that the Natural and Landscape Spaces of the few PDMs that allow the extraction of minerals do not include areas covered by nature protection regimes or that these PDMs need to adapt to the sectoral and special programs that have come into force in the meantime.

Regarding the agricultural and forest spaces,

Figure 3 shows the distribution of the number of cases in which they are compatible with the exploitation of geological resources, according to the subcategories presented in

Table 4. As in each PDM agricultural and forest spaces can be subdivided into several subcategories, the number of registered cases exceeds the total number of PDMs analysed. Despite some variation in the compatibility of each of these subcategories with the extractive industry, what is important to highlight is that compatibility is largely not accepted.

In addition, the study carried out also made it possible to verify other limitations to the safeguarding of mineral resources. In a significant number of PDMs, the respective regulation establishes the compatibility of all rural land with extractive activities, but a detailed analysis shows that this compatibility only refers to land subcategorized as Potential Area for minerals. For the Agricultural and Forest spaces where compatibility with mineral extraction is assured, usually this is strongly conditioned by special authorization from the municipal council or the national nature conservation authority or even only considered in cases of national strategic interest.

Given that the legislation specifically states that Agricultural and Forest spaces are compatible with the exploitation of geological resources, a conclusion that can be drawn from the results is that these PDMs are in an irregular situation, particularly those who do not consider any compatibility with mineral extraction. It does not seem that this is due to simple ignorance of the law, as that is not acceptable. It may be the result of some negligence on the part of the entities involved in the PDM revision processes to keep up with the NIMBY (i.e., Not In My Back Yard) trends that have dominated European policies in recent decades. Just as political will or uninformed political advice can be the reasons for not delimiting the SEGR or for their delimitation as a copy of the legally settled mining areas, aimed at preventing their expansion or the emergence of new ones, we may also be facing the same situation here. Indeed, considering the prevailing bad social reputation of mineral extraction activities, it is much easier, from a political point of view, to approve a PDM that does not address measures to minerals safeguarding than the other way around.

6. Implications of Policies for the Exploration and Extraction of Minerals in Portugal

The integration of mineral resources into land use policy is a “wicked” problem [

72,

73], i.e., for which there are no right or wrong solutions, but only good or bad options. The way this integration occurs within the Portuguese legislative framework seems to be a bad option, as mineral resources are not considered on an equal footing with other resources. This has several consequences for the municipal LUP practice, where ensuring the access to land for mineral activities is not the general rule, but the exception.

There are several aspects of the legislation that allow to verify this unequal treatment between geological resources and other territorial values.

First, it is worth noting that although geological resources are natural resources, the general law still follows a European spatial development perspective from the 90’s [

74] by distinguishing them from other natural resources.

Second, given the absence of a specific sectoral policy for geological resources, when the different competing interests for land use are considered, priority is given by law to values that are the target of sectoral or especial policies. Therefore, when outlining a PDM Zoning Map, the spaces that may be considered to integrate the SEGR are already conditioned by those related to sectoral or especial policies. As an example, in a PDM that covers a nature park located over mineral resources, priority is given to delimiting the nature park in the zoning map.

This would not be a problem if the areas covered by these programs provided for the safeguarding of mineral resources by considering the compatibility of uses with the extractive industry. However, as the several LUP interests are taken in a siloed approach where there is little interaction between government departments, this is not the case. As demonstrated previously, in most of the rural land categorised as Natural and Landscape Space, mineral exploitation activities are prohibited, and the EU recommendations to ensure the sustainable development of extractive activities even in environmentally protected areas [

71,

75] to meet the current demand for mineral raw materials are not adopted in any way.

Thirdly, geological resources are considered based on the activity that makes them available to society, rather than based on their intrinsic value as resources. Indeed, the legislation establishes that geological resources must be considered in a land use category called Spaces for the Exploitation of Geological Resources, confirming observation that geological resources are often a neglected component of comprehensive natural resources management, being typically addressed within the limited scope of resource extraction [

76].

Finally, as a consequence of the previous point, the areas designated for the exploitation of geological resources are considered anomalies to the use of the land. This is demonstrated by the fact that this category of rural land is the only one for which the legislation establishes the need to minimize environmental impacts and implement landscape recovery measures. Nothing is said, for example, about the need for more sustainable agricultural practices, when it is known that agriculture is one of the main sources of soil and aquifer pollution [

77].

As pointed out before, there is a problem in interpreting which type of areas should be included in the category Spaces for the Exploitation of Geological Resources (SEGR). As Regulatory Decree 15/2015 specifies that rural land to be included in this category is that allocated to the exploitation of geological resources, LUP professionals tend to consider that only the areas legally granted for extraction should be included in this category. Therefore, when thinking on safeguarding the access to mineral resources, this land use category only safeguards the access to minerals that have already been discovered, which results in an inconsistency: if they have been discovered, evaluated and their extraction licensed, it is because accessibility to them was already assured.

When attention is focused on mining laws, it is noteworthy that Decree-Law 30/2021 (amended by Law 10/2022), which regulates the exploration and exploitation of public domain minerals, includes provisions for the safeguarding of areas already protected by other legal instruments, thus preventing further acquisition of knowledge about mineral occurrences. These provisions relate to the prohibition of exploration activities in urban and rural agglomerations, in and around superficial water bodies, and in protected areas. Truly, the ban of mineral exploration from protected areas is only applied when the initiative for the exploration permitting process comes from a DGEG’s public tender. However, this is a sign that any proposal to ban mineral exploration will be accepted by DGEG during the exploration permitting procedures resulting from a private sector initiative. As most of the environmentally protected areas already prohibit mineral extraction, it is expected that the respective management bodies will propose a ban on mineral exploration too, when consulted by DGEG. As mentioned before, very recent legislation is already imposing the ban of mineral exploration activities in nature protected areas, which corresponds to a form of political censorship regarding the acquisition of geological knowledge about Portugal. Again, if the European Commission has developed guidelines to prevent an automatic exclusion of mining in or near the Natura 2000 Network sites, what is the reasoning behind banning mineral exploration? Even in the absence of these guidelines, what could be the reason for banning mineral exploration in protected areas or anywhere else in Portugal, knowing that no mining operation can take place without first undergoing an environmental impact assessment? A straightforward explanation could be that we are dealing with uninformed political decisions.

Now, if the mining legislation paves the way for mineral exploration to be excluded from protected areas and if the interpretation of the LUP legislation regarding the SEGR is the restrictive one, the only land use categories in which accessibility to minerals is legally guaranteed for the discovery of mineral deposits are agricultural and forest spaces. However, as the results obtained in this study demonstrate, compatibility with the extractive industry is not guaranteed in most of these areas. Therefore, there is no justification for mineral exploration investments when it is known that the extraction of any discovered mineral deposits will not be allowed.

7. Conclusions

In Portugal, both mining and LUP legislation address mineral resources within the broader group of geological resources. Their exploitation can be carried out under a mining concession (mine) if they are state-owned resources, or a license (quarry) if they are private-owned resources, but, in both cases, it depends on the results of an Environment Impact Assessment procedure.

Minerals safeguarding is a concept applied during LUP and can be understood in several ways, all of them aiming to make minerals available to society when needed: (i) The protection of mineral resources from being unnecessarily sterilised during the LUP process, i.e., preventing the loss of the option to exploit them, and (ii) ensure that the mining sector has access to the places where mineral resources occur or are strongly expected to occur.

The Portuguese LUP legislation distinguishes urban from rural land and establishes formal land use categories for the latter. Municipal Master Plans (PDM) are the executive LUP tools in which the land use categories are depicted in zoning maps. The rural land use policy is focused on the management of the so-called dominant uses, therefore, not open to disruptions that could lead to new forms of development. It is a ten-year-old legislation reflecting a rationale for minerals that prevails since the end of the last century: mineral extraction is seen as an anomaly in land use.

In LUP, mineral resources are not considered on their own, i.e., as a natural wealth that deserves to be safeguarded, but rather addressed through extractive activity in two distinct ways: the delimitation of a land use category called Spaces for the Exploitation of Geological Resources (SEGR) and the acknowledgment of the compatibility of other land use categories with the exploitation of minerals. In any case, this is how the safeguarding of minerals can be carried out in the Portuguese LUP framework. In a broad sense, the SEGR correspond to areas with recognised suitability for the valorisation and exploitation of geological resources. However, in most cases, LUP professionals mostly interpret this land use category as corresponding to the areas for which extraction permits have been issued, not extending it to places where other mineral resources exist or may exist.

The compatibility of some land use categories with the extractive industry is a way to safeguard mineral resources, because if they can be extracted, it is because access to them is ensured. The LUP legislation explicitly foresees this compatibility for agricultural and forest areas, but practice shows that this is not fulfilled in most PDMs.

Thus, for municipalities where the SEGR were considered equivalent to areas legally granted for mining and the compatibility of agricultural and forestry areas with the extractive industry is not assured, all remaining mineral resources are sterilized and there is no possibility for new mining operations.

From the mining industry point of view, the only areas available for mineral exploration in Portugal are those included in the SEGR, but not yet granted for extraction, and the agricultural and forest land use categories for which compatibility with minerals extraction has been assured. Outside these areas, investments in mineral exploration are not justified, because even if mineral deposits are discovered, their extraction is prohibited by the PDM without a prior assessment of the possible impacts on the environment and society.

If there is an intention to take advantage of Portugal's mineral wealth, what was demonstrated by this paper points to the need for a change in the Portuguese LUP and minerals legislative framework, as they are unfavourable to the extraction and even exploration of minerals. Furthermore, this change is urgent, otherwise the national exploration programme envisaged under the Critical Raw Materials Act will not make sense because the respective results will not trigger investments in detailed exploration activities by private operators due to the restrictions imposed on access to land. If these findings also apply to other European Union member states, it is very likely that the Critical Raw Materials Act’s target to produce at least 10% of critical raw materials in Europe will not be achieved.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.; methodology, J.C. and V.L.; validation, R.S.; formal analysis, V.L. and J.C.; resources, J.C., V.L. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.; writing—review and editing, J.C., V.L. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DGEG |

Directorate General for Energy and Geology |

| LNEG |

National Laboratory for Energy and Geology |

| LUP |

Land Use Planning |

| PDM |

Municipal Master Plan |

| SEGR |

Spaces for the Exploitation of Geological Resources |

References

- European Commission. The Raw Materials Initiative - Meeting Our Critical Needs for Growth and Jobs in Europe; Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council; COM(2008) 699, {SEC(2008) 2741}; European Commission: Brussels, 2008; Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2008:0699:FIN:en:PDF (accessed on 14 November 2019).

- European Commission. Report of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Defining Critical Raw Materials; European Commission: Brussels, 2014; Available online: https://rmis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/uploads/crm-report-on-critical-raw-materials_en.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Gugerell, K.; Endl, A.; Gottenhuber, S. L.; Ammerer, G.; Berger, G.; Tost, M. Regional Implementation of a Novel Policy Approach: The Role of Minerals Safeguarding in Land-Use Planning Policy in Austria. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badera, J. ; Kocoń,, P. Moral Panic Related to Mineral Development Projects – Examples from Poland. Resour. Policy 2015, 45, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyytimäki, J.; Peltonen, L. Mining through Controversies: Public Perceptions and the Legitimacy of a Planned Gold Mine near a Tourist Destination. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, A. Changing Social Perceptions on Mining-Related Activities: A Key Challenge in the 4th Industrial Revolution. Asp. Min. Miner. Sci. 2020, 5, 568–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, P.; Gugerell, K.; Poelzer, G.; Hitch, M.; Tost, M. European Mining and the Social License to Operate. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrighton, C. E.; Bee, E. J.; Mankelow, J. M. The Development and Implementation of Mineral Safeguarding Policies at National and Local Levels in the United Kingdom. Resour. Policy 2014, 41, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endl, A.; Gottenhuber, S. L.; Gugerell, K. Bridging Policy Streams of Minerals and Land Use Planning: A Conceptualisation and Comparative Analysis of Instruments for Policy Integration in 11 European Member States. In REAL CORP 2020 Proceedings; Schrenk, M., Popovich, V., V., Zeile, P., Elisei, P., Beyer, C., Ryser, J., Reicher, C., Eds.; RWTH Aachen, Germany (virtual conference), 15-, 2020; pp 95–105. 18 September.

- Endl, A.; Gottenhuber, S. L.; Gugerell, K. Drawing Lessons from Mineral and Land Use Policy in Europe: Crossing Policy Streams or Getting Stuck in Silos? Extr. Ind. Soc. 2023, 15, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wårell, L. Mineral Deposits Safeguarding and Land Use Planning—The Importance of Creating Shared Value. Resources 2021, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot-Niewiadomska, A.; Galos, K.; Kamyk, J. Safeguarding of Key Minerals Deposits as a Basis of Sustainable Development of Polish Economy. Resources 2021, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieć,, M. ; Radwanek-Bąk, B.; Koźma, J.; Kozłowska, O. Polish Approach to the Mineral Deposits Safeguarding. Experience and Problems. Resour. Policy 2022, 75, 102460. [CrossRef]

- Mateus, A.; Lopes, C.; Martins, L.; Carvalho, J.M.F. Towards a Multi-Dimensional Methodology Supporting a Safeguarding Decision on the Future Access to Mineral Resources. Miner. Econ. 2017, 30, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.M. F.; Ardvisson, R.; Raaness, A.; Dinis, P.; Lisboa, J. V.; Figueira, M. J.; Schiellerup, H. Safeguarding Mineral Resources in Europe: Existing Practice and Possibilities; MinLand - Mineral resources in sustainable land-use planning; Deliverable 2.3; 2019; p 69. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5beebdbd2&appId=PPGMS (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Carvalho, J.M. F.; Galos, K.; Kot-Niewiadomska, A.; Gugerell, K.; Raaness, A.; Lisboa, J. V. A Look at European Practices for Identifying Mineral Resources That Deserve to Be Safeguarded in Land-Use Planning. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngs, R. Europe’s Decline and Fall: The Struggle Against Global Irrelevance; Profile Books Ltd: London, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- European Economic Social, C.o.m.m.i.t.t.e.e. ; CEPS What Ways and Means for a Real Strategic Autonomy of the EU in the Economic Field? Publications Office: LU, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Draghi, M. The Future of European Competitiveness.; European Commission: Bruxels, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council. Regulation (EU) 2024/1252 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 April 2024 Establishing a Framework for Ensuring a Secure and Sustainable Supply of Critical Raw Materials; 2024. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1252/2024-05-03 (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- European Commission Critical Raw Materials for the, E.U. Report of the Ad-Hoc Working Group on Defining Critical Raw Materials.; European Commission: Brussels, 2010; Available online: https://www.euromines.org/files/what-we-do/sustainable-development-issues/2010-report-critical-raw-materials-eu.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- European Commission. Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards Greater Security and Sustainability. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions.; COM(2020) 474 Final; Brussels, 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0474 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Taylor, N. What Is This Thing Called Spatial Planning? An Analysis of the British Government’s View. Town Plan. Rev. 2010, 81, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas Palom, A.; Saurí Pujol, D.; Olcina Cantos, J. Sustainable Land Use Planning in Areas Exposed to Flooding: Some International Experiences. In Floods; Vinet, F., Ed.; Elsevier, 2017; pp 103–117. [CrossRef]

- Pendock, M.J. Sterilisation and Safeguarding of Mineral Deposits in Britain. Miner. Environ. 1984, 6, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knepper Jr, D.H. Planning for the Conservation and Development of Infrastructure Resources in Urban Areas—Colorado Front Range Urban Corridor: Things Planners, Decision-Makers, and the Public Should Know. U.S. Geological Survey circular 1219; USGS, 2002.

- Briskey, J.A. and Schulz, K.J. Proceedings for a Workshop on Deposit Modeling, Mineral Resource Assessment, and Their Role in Sustainable Development. U.S. Geological Survey circular 1294; USGS: Reston, Va, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nickless, E.; Ali, S.; Arndt, N.; Brown, G.; Demetriades, A.; Durrheim, R.; Enriquez, M.; Giurco, D.; Kinnaird, J.; Littleboy, A. Resourcing Future Generations: A Global Effort to Meet The World’s Future Needs Head-On.; International Union of Geological Sciences, 2015; p 2.

- Meinert, L.; Robinson, G.; Nassar, N. Mineral Resources: Reserves, Peak Production and the Future. Resources 2016, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, A.; Martins, L. Challenges and Opportunities for a Successful Mining Industry in the Future. Bol. Geológico Min. 2019, 130, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villas-Boas, R. C.; Shields, D.; Solar, Š.; Anciaux, P.; Önal, G. A Review on Indicators of Sustainability for the Mineral Extraction Industries; CETEM/MCT/ CNPq/CYTED/IMPC: Rio de Janeiro, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, J.; Cohen, B.; Stewart, M. Decision Support Frameworks and Metrics for Sustainable Development of Minerals and Metals. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2007, 9, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K. Application of Multi-Criteria Decision Making/Operations Research Techniques for Sustainable Management in Mining and Minerals. Resour. Policy 2015, 46, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marnika, E.; Christodoulou, E.; Xenidis, A. Sustainable Development Indicators for Mining Sites in Protected Areas: Tool Development, Ranking and Scoring of Potential Environmental Impacts and Assessment of Management Scenarios. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 101, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tost, M.; Hitch, M.; Chandurkar, V.; Moser, P.; Feiel, S. The State of Environmental Sustainability Considerations in Mining. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, R.; Bennett, J. Valuing the Environmental, Cultural and Social Impacts of Open-Cut Coal Mining in the Hunter Valley of New South Wales, Australia. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 2012, 1, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.-H.; Lin, Y.; Tseng, M.-L. Multicriteria Analysis of Sustainable Development Indicators in the Construction Minerals Industry in China. Resour. Policy 2015, 46, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, L.; Sala, S. Social Impact Assessment in the Mining Sector: Review and Comparison of Indicators Frameworks. Resour. Policy 2018, 57, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janikowska, O.; Kulczycka, J. Impact of Minerals Policy on Sustainable Development of Mining Sector – a Comparative Assessment of Selected EU Countries. Miner. Econ. 2021, 34, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoni, M. U.; Drielsma, J. A.; Ericsson, M.; Gunn, A. G.; Heiberg, S.; Heldal, T. A.; Nassar, N. T.; Petavratzi, E.; Müller, D. B. Mass-Balance-Consistent Geological Stock Accounting: A New Approach toward Sustainable Management of Mineral Resources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 971–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carranza, E.J. M.; Jerrysal, C. M.; Martin, H. Application of Mineral Exploration Models and GIS to Generate Mineral Potential Maps as Input for Optimum Land-Use Planning in the Philippines. Nat. Resour. Res. 1999, 8, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, D. A.; Menzie, W. D.; Sutphin, D. M.; Mosier, D. L.; Bliss, J. D. Mineral Deposit Density: An Update, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1640–A.; US Geological Survey: Reston, Virginia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Porwal, A.K. Mineral Potential Mapping with Mathematical Geological Models. PhD Thesis, Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University and International Institute for Geo-information Science and Earth Observation, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Carranza, E.J. M.; Xia, Q. Developments in Quantitative Assessment and Modeling of Mineral Resource Potential: An Overview. Nat. Resour. Res. 2022, 31, 1825–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henckens, M.L.C.M. Managing Raw Materials Scarcity : Safeguarding the Availability of Geologically Scarce Mineral Resources, Utrecht University, 2016. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/339827.

- Arndt, N. T.; Fontboté, L.; Hedenquist, J. W.; Kesler, S. E.; Thompson, J. F. H.; Wood, D. G. Future Global Mineral Resources. Geochem. Perspect. 2017, 1–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, K. M.; Wall, F.; Merriman, D. The Rare Earth Elements: Demand, Global Resources, and Challenges for Resourcing Future Generations. Nat. Resour. Res. 2018, 27, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilton, J. E.; Crowson, P. C. F.; DeYoung, J. H.; Eggert, R. G.; Ericsson, M.; Guzmán, J. I.; Humphreys, D.; Lagos, G.; Maxwell, P.; Radetzki, M.; Singer, D. A.; Wellmer, F.-W. Public Policy and Future Mineral Supplies. Resour. Policy 2018, 57, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, A.; Martins, L. Building a Mineral-Based Value Chain in Europe: The Balance between Social Acceptance and Secure Supply. Miner. Econ. 2021, 34, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.; Dahl, C. A.; Fleming, M.; Tanner, M.; Martin, W. C.; Nadkarni, K.; Hastings-Simon, S.; Bazilian, M. Projecting Demand for Mineral-Based Critical Materials in the Energy Transition for Electricity. Miner. Econ. 2024, 37, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, R.J. The Raw Material Challenge of Creating a Green Economy. Minerals 2024, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, S. Material World: How Europe Can Compete with China in the Race for Africa’s Critical Minerals; Policy Brief; European Council on Foreign Relations, 2024; p 21. https://ecfr.eu/publication/material-world-how-europe-can-compete-with-china-in-the-race-for-africas-critical-minerals/ (accessed 2024-12-11).

- McEvoy, F. M.; Cowley, J.; Hobden, K.; Bee, E.; Hannis, S. A Guide to Mineral Safeguarding in England.; OR/07/035; British Geological Survey Open Report, 2007; p 36.

- Weber, L. Der Osterreichische Rohstoffplan. Archiv für Lagerstättenforschung; Geologische Bundesanstalt: Wien, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- AHWG-RMSG Recommendations on the Framework Conditions for the Extraction of Non-Energy Raw Materials in the European Union; European Commission, Series Ed. ; Report of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Exchange of best practices on minerals policy and legal framework information framework, land-use planning and permitting; Ares(2014)2018646; European Commission: Brussels, 2014; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/5571/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/pdf (accessed on 14 November 2019).

- Falé,, P. ; Henriques, P.; Midões, C., Carvalho, J., Sobreiro, S., Martins, L. Use of Geological and Environmental Indicators in Mining Land Use Planning – A Case Study of the Estremoz Anticline. In Agua, Mineria y Medio Ambiente: libro homenage al profesor Rafael Fernandez Rubio, López-Geta, J. A., Bosch, A. P., Ubeda, J. C. B., Eds.; IGME: Madrid, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, J.M. F.; Meira, J.; Marques, C.; Machado, S.; Mergulhão, L. M.; Cancela, J. F. Nature Conservation, Land Use Planning and Exploitation of Ornamental Stones - The Case Study of Cabeça Veada (Portugal). Key Eng. Mater. 2020, 848, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.; Meira, J.; Marques, C.; Machado, S.; Mergulhão, L.; Cancela, J. Sustainable Exploitation of Mineral Resources within an Area of the Natura 2000 Network. Eur. Geol. 2016, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Duran, G.; Arranz-González, J. C.; Vega-Panizo, R. El Análisis Del Potencial Geológico de Rocas Industriales En Proyectos de Planificación Territorial: Una Revisión. Bol. Geológico Min. 2014, 125, 475–492. [Google Scholar]

- Marinoni, O.; Hoppe, A. Using the Analytical Hierarchy Process to Support Sustainable Use of Geo-Resources in Metropolitan Areas. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2006, 15, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamelas, M. T.; Marinoni, O.; Hoppe, A.; de la Riva, J. Suitability Analysis for Sand and Gravel Extraction Site Location in the Context of a Sustainable Development in the Surroundings of Zaragoza (Spain). Environ. Geol. 2008, 55, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałaś; S Environmental Valorisation of Mineral Deposits. In Ecology and environmental protection; Albena, Bulgaria, 2014; pp 267–274.

- Haines, S. S.; Diffendorfer, J. E.; Balistrieri, L.; Berger, B.; Cook, T.; DeAngelis, D.; Doremus, H.; Gautier, D. L.; Gallegos, T.; Gerritsen, M.; Graffy, E.; Hawkins, S.; Johnson, K. M.; Macknick, J.; McMahon, P.; Modde, T.; Pierce, B.; Schuenemeyer, J. H.; Semmens, D.; Simon, B.; Taylor, J.; Walton-Day, K. A Framework for Quantitative Assessment of Impacts Related to Energy and Mineral Resource Development. Nat. Resour. Res. 2014, 23, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwanek-Bąk, B. ; Nieć,, M. Valorization of Undeveloped Industrial Rock Deposits in Poland. Resour. Policy 2015, 45, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galos, K.; Tiess, G.; Kot-Niewiadomska, A.; Murguía, D. ; Wertichová,, B. Mineral Deposits of Public Importance (MDoPI) in Relation to the Project of the National Mineral Policy of Poland. Mineral Resources Management. 2018, pp 5–24.

- Wårell, L.; Häggquist, E. Defining Mineral Deposits of National Interest – The Case of Sweden. European Geologist Journal. 2016, pp 35–37.

- Raaness, A.; Aasly, K.; Schiellerup, H. Mineralske ressurser og vindkraft; 2018.008; NGU: Trondheim, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cavaco, C.; Mourato, J.; Costa, J. P.; Pereira, A.; Vilares, E.; Moreira, P.; Magalhães, M. Spatial Planning and Regional Development in Portugal; Direção-Geral do Território: Lisboa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Endl, A.; Gottenhuber, S. L.; Berger, G.; Arvanitidis, N.; Ardvisson, R.; Cormont, A.; Sluis, T. van der; Galos, K.; Carvalho, J.; Schiellerup, H.; Tost, M.; Luodes, N.; Dinis, P.; Figueira, M. J. Final Manual for Good Practice on Mineral Resources in Sustainable Land-Use Planning.; Project Deliverable Minland Project; 2019. https://www.minland.eu/wp-content/uploads/D6.2_Final-Manual_final-online-submission_6-12-2019.pdf (accessed 2024-10-10).

-

DGOTDU Vocabulário de Termos e Conceitos Do Ordenamento Do Território; Direção Geral de Ordenamento do Território e Desenvolvimento Urbano: Lisboa, 2005.

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Environment. EC Guidance on Undertaking Non-Energy Extractive Activities in Accordance with Natura 2000 Requirements.; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metlay, D.; Sarewitz, D. Decision Strategies for Addressing Complex, “Messy” Problems. The Bridge. 2012, pp 6–16.

- Endl, A. Addressing “Wicked Problems” through Governance for Sustainable Development—A Comparative Analysis of National Mineral Policy Approaches in the European Union. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy. ESDP – European Spatial Development Perspective: Towards balanced and sustainable development of the territory of the European Union, Publications Office, 1999. https://op.europa.eu/s/z6W5.

- Olmeda, C.; Barov, B. Non-Energy Mineral Extraction in Relation to Natura 2000 - Case Studies; N2K Group EEIG and the Institute for European Environmental Policy. Contract N° 07.0202/2017/766291/SER/D.3 for the European Commission; Brussels, 2019. Available online: https://www.aggregates-europe.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/NEEI_case_studies_-_Final_booklet.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Doss, P.K. Integrated Geological Resources Management for Public Lands: A Template from Yellowstone National Park. GSA Today 2008, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Bahar, M. M.; Naidu, R. Diffuse Soil Pollution from Agriculture: Impacts and Remediation. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 962, 178398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).