Introduction

Empathy has long been conceptualized within psychology and neuroscience as an automatic, emotionally driven mechanism enhancing prosocial behavior and social cohesion. Prevailing models often emphasize its reactive nature, linking empathic activation to shared neural representations and mirroring processes that occur in response to another’s distress (Keysers et al., 2024). In this context, systemic suffering refers to distress arising from structural, institutional or group-based injustices such as racism, inequality or political oppression typically implicating broader social systems. In turn, non-systemic suffering involves individual or situational pain such as illness or personal loss that lacks a clear socio-political context. The distinction reflects whether the suffering is perceived as embedded within collective structures or isolated from ideological or institutional dimensions. These frameworks have proven valuable in identifying neural correlates and behavioral outcomes of empathic engagement. However, they tend to understate the role of cognitive bias, ideological influence and contextual modulation (Hopp et al., 2023; Briganti et al., 2024).

Recent advances in political psychology and affective neuroscience indicate that empathy is neither universal nor morally neutral (Tesi & Passini, 2025; Barrett et al., 2025; Zaki, 2020; Zebarjadi et al., 2024), but subject to modulation by higher-order belief systems and situational variables. The integration of Bayesian brain theory has begun to challenge reactive models, offering a probabilistic and predictive framework in which perception and emotion are shaped by internal priors and contextual expectations (Friston et al., 2022; Parr et al., 2022; Keysers et al., 2024). Nevertheless, existing approaches remain limited in their capacity to capture the complex, multidimensional architecture through which empathy is constrained, deformed or facilitated by ideological, physiological and dispositional factors (Choma et al., 2022). This conceptual gap calls for a formal model that may account not only for the presence or absence of empathic behavior, but also for the structural transformations governing its variability.

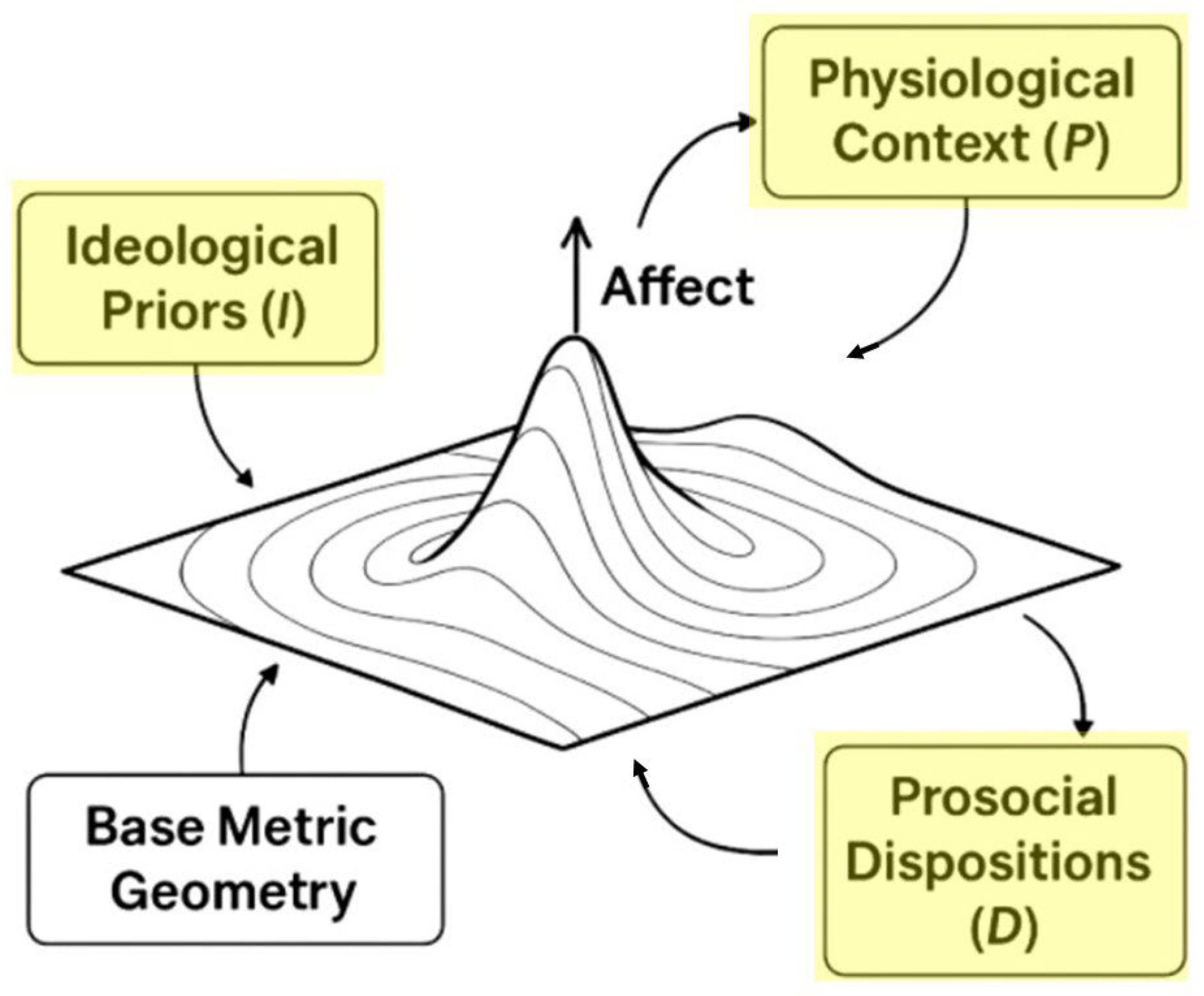

To address this, we introduce a topological model of empathy which frames affective response as a structured, continuous surface shaped by three primary determinants: internalized ideological priors, physiological modulation and prosocial regulatory traits. Drawing from geometric and computational principles, our approach treats empathy as a context-sensitive and deformable construct, where each determinant works as a distinct transformation acting upon an underlying affective field. Our model aims to formalize empathic bias as a warping of perception space, rather than a simple increase or decrease in emotional intensity. By characterizing ideological priors as curvatures, physiological variables as warping functions and prosocial traits as smoothing operators, we aim to build a unified, generative framework capable of representing empathic variability across individuals and situations. Within this structure, we hypothesize that empathic response patterns can be predicted based on the interaction of these parameters and suggest that shifts in prosocial disposition may significantly modulate the topological features of the empathic field.

We will proceed as follows: we first present the mathematical formulation of our topological model, then define the variables and their operationalization. This is followed by a simulation and visualization of empathic surfaces. We conclude with a discussion of structural implications and interpretative limits.

Materials and Methods

To formalize the mechanisms underlying empathic variability, we developed a topological framework grounded in differential geometry (Do Carmo, 1992; Gromov, 1986) which aims to integrate ideological, physiological and dispositional parameters into a continuous and deformable affective space.

Mathematical approach and general framework. We adopt a topological formalism to represent empathic responses as smooth mappings between latent affective states and observable behavioral expressions. Let M ⊂ ℝ³ be a manifold where each point (i, p, d) ∈ M corresponds to a triplet of latent variables: ideological priors, physiological modulation and prosocial disposition. We define an empathic response function E: M → ℝ, such that E(i, p, d) denotes the scalar affective intensity associated with this configuration. The underlying intuition is that empathy emerges as a topologically deformable surface ΣE whose geometry reflects the dynamic interplay of priors and modulators.

We treat E as a smooth, bounded and differentiable function, enabling the use of differential geometric tools for analysis. Overall, by embedding the affective function in a Riemannian manifold, we capture not only the magnitude but also the curvature, connectivity and local deformations of empathy in response to structural constraints.

Ideological priors as metric tensors. Ideological priors are modeled as metric tensors defining the local geometry of the manifold (Tesi & Passini, 2025; Choma et al., 2022). We formalize these priors using indices from Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) and Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) (Pratto et al., 1994; Altemeyer, 1996), represented as scalar fields s and r. These values determine the ideological curvature tensor:

where

and

encode curvature due to dominance and authoritarian priors, respectively. Higher values elongate the geodesic paths between affective states, especially those related to outgroup suffering, reducing empathic connectivity in ideologically constrained directions.

Physiological modulation as warping functions. Physiological states act as warping functions that modulate empathic gain by dynamically altering the geometry of the space (Keysers et al., 2024; Hopp et al., 2023). Let p = (b, s, d) be a vector of physiological dimensions, where b is Belief in a Dangerous World (BDW), s is Perceived Stress Reactivity Scale (PSRS) and d is Pathogen Disgust Sensitivity (PVD)

Each component maps to a scalar field wk(x) and the total warping is:

with α1 = 0.3, α2 = 0.3, α3 = 0.2. This produces a conformal transformation of the manifold:

Regions of high physiological arousal become stretched, exaggerating ideological curvature and distorting empathic inference (Zebarjadi et al., 2022).

Prosocial dispositions as smoothing operators. Prosocial traits such as dispositional empathy (measured via IRI) and cooperative preference (CPC) act as smoothing fields that regularize curvature and reconnect disjoint affective regions (Zaki, 2020; Wang et al., 2024). We define:

with β1 = 0.3, β2 = 0.3. These fields apply a Laplace-Beltrami smoothing kernel to reduce abrupt curvature shifts:

This operation reduces sectional curvature and restores affective accessibility across ideological and physiological divides.

Information-theoretic curvature and empathic cost. Empathic response may also be viewed as a periodic oscillation shaped by ideological and physiological phase shifts (Mohanta et al., 2024). Let E be defined as:

where A is the amplitude of affective responsiveness, ω is the resonance frequency (influenced by dispositional empathy and openness) and φ is a phase function altered by ideological rigidity and physiological arousal. This oscillatory model suggests that empathy is not a binary activation, but a modulated wave that can be reinforced, dampened or desynchronized by internal priors. This paves the way to modeling affective synchronization, entrainment and breakdown under social polarization.

Oscillatory formalization of affective resonance. Building on the predictive brain hypothesis, we formalize empathic processing as a probabilistic inference mechanism (Friston et al., 2022; Parr et al., 2022; Briganti et al., 2024). Let E denote the internal affective state and s a stimulus associated with suffering. The posterior probability of an empathic response can be defined as:

Here, P(E) is the prior probability distribution shaped by ideological factors such as RWA and SDO (Pratto et al., 1994; Altemeyer, 1996), while P(s|E) reflects perceptual likelihood modulated by physiological states (Keysers et al., 2024; Zebarjadi et al., 2022). This formulation allows ideological priors to act as cognitive filters that skew the plausibility of affective engagement. Bayesian curvature emerges when prior beliefs significantly constrain posterior variability, introducing ideological rigidity into the perception-action loop.

Bayesian framing of ideological priors. While the current models treat empathy as a static mapping from latent priors to affective intensities, we argue that empathic responses may be inherently dynamic and temporally modulated. To capture this, we introduce a partial time derivative into the empathic function:

This temporal formulation allows the empathic surface to evolve as ideological priors, physiological states and prosocial traits shift over time. This reflects changes in environmental context, cognitive framing and emotional learning (Barrett et al., 2025; Zhou & Jenkins, 2023). Therefore, incorporating time as a fourth axis transforms the empathic manifold into a dynamic field, enabling simulation of longitudinal trajectories and empathic plasticity.

Temporal dynamics and surface construction of empathic surfaces. To visualize the empathic topology, we construct a surface ΣE ⊂ ℝ³ by evaluating the scalar field E(i,p,d) over a discretized grid of parameter space. Let i,p,d ∈ [0,1] each be discretized into n = 100 steps, forming a 3D lattice of 10⁶ points. For each point, the empathic intensity is calculated using:

This functional form encodes the relative contribution of each determinant while maintaining differentiability across the space. The resulting scalar field can be rendered using surface plots and contour maps, capturing local maxima (facilitated empathy) and minima (inhibited empathy) as geometric features such as ridges, valleys and plateaus (

Figure 1). Topological features such as critical points, gradients and curvature tensors are derived using numerical differentiation (Mohanta et al., 2024). These visualizations allow an interpretation of empathic responses not as binary activations, but as continuous deformations in a high-dimensional affective surface.

Simulation and computational tools. We simulated empathic response surfaces generated using the proposed topological framework. We modeled empathic response as a scalar field over a three-dimensional parameter space defined by ideological priors, physiological modulation and prosocial dispositions. We used five hundred synthetic agents representing individuals with varying ideological, physiological and prosocial traits, enabling controlled exploration of their empathic response variability. We computed empathic intensity for two conditions, namely systemic and non-systemic suffering based on the Affective-Ideological Polarization Factor (FPAI). Empathic responses were calculated using a weighted function that integrated ideological curvature, physiological warping and prosocial smoothing. The resulting values were visualized through line graphs and histograms to capture topological features such as dispersion and response gradients.

All mathematical modeling and simulations were performed in Python 3.11 using a set of numerical and visualization libraries including NumPy, SciPy and Matplotlib. Tensor operations and differential geometry functions were implemented manually where not available in standard libraries. Surface smoothing, Laplacian computation and geodesic analysis were supported using custom code routines. Symbolic differentiation for verifying curvature formulations was carried out using SymPy. For grid-based evaluations of empathic surfaces, meshgrids were generated via NumPy’s meshgrid() function and empathic intensity was evaluated point-wise over the full domain. Visualization of empathic topologies was accomplished through Axes3D.plot_surface() and contourf() functions, with colormaps encoding empathic intensity (Ammons et al., 2025; Salatino et al., 2025). Code modularity was maintained using object-oriented practices to isolate metric definition, physiological warping and smoothing transformations. Computational stability was ensured by regularizing all scalar fields and applying bounded transformations to avoid divergence.

Overall, our methodological architecture provides a mathematical structure for analysing how empathy emerges from the interaction of cognitive, ideological and physiological variables. It enables systematic investigation of affective modulation as a function of topological deformation, capturing the dynamic reshaping of empathic accessibility within a multidimensional perceptual space.

Results

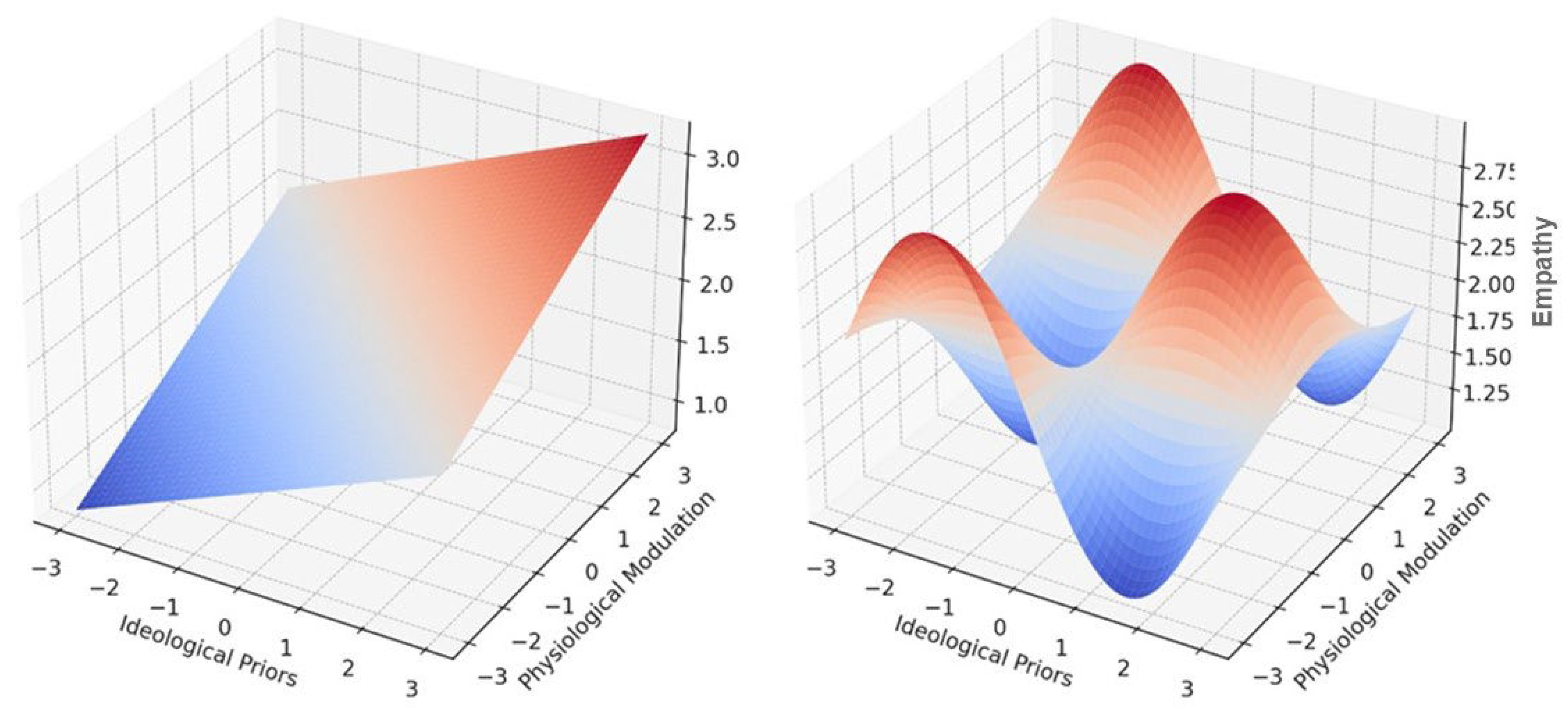

By manipulating ideological priors, physiological modulation and prosocial dispositions, we simulated how these factors interact to shape the structure of affective accessibility, visualizing their combined influence as geometric deformations within a continuous affective manifold that encodes the dynamic topology of empathic responsiveness.

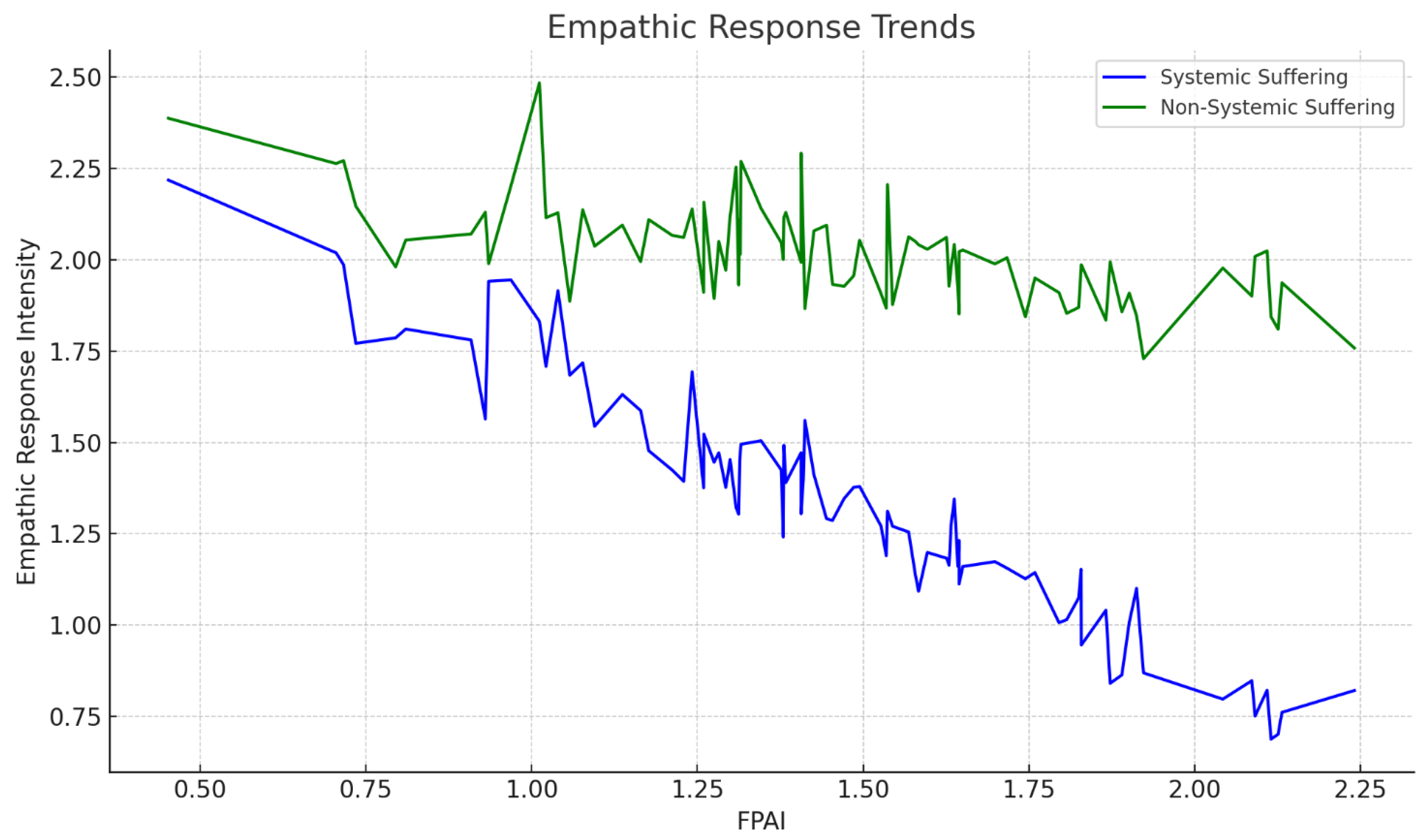

Empathy toward systemic suffering showed a marked inverse relationship with Affective-Ideological Polarization Factor (FPAI): individuals with higher FPAI scores exhibited significantly lower affective resonance (

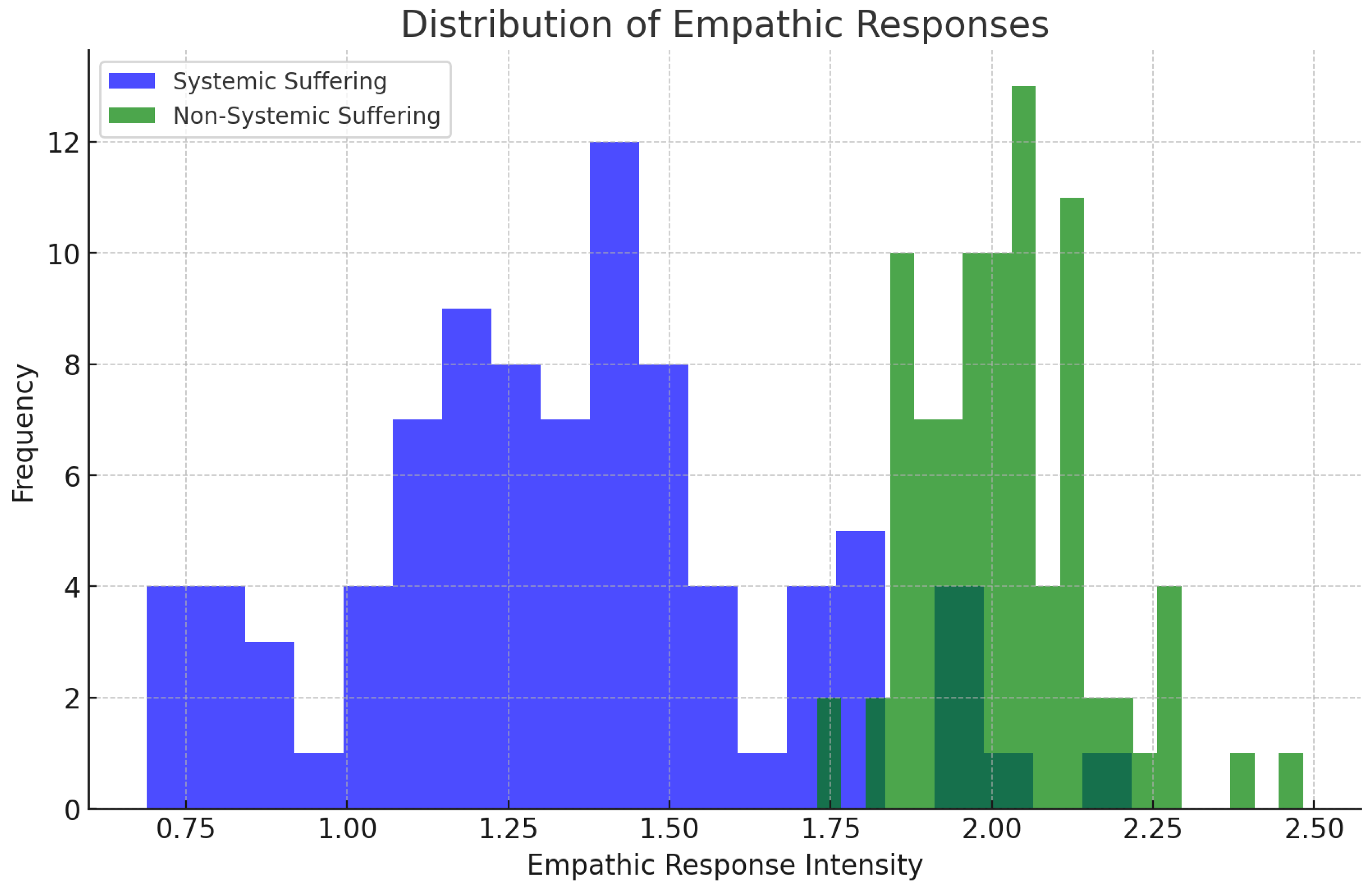

Figure 2). The mean empathic response for systemic suffering was 1.33 (SD = 0.33), compared to 2.02 (SD = 0.13) for non-systemic suffering, with a paired-sample t-test confirming a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001). This pattern suggests that ideological curvature, amplified by physiological warping, jointly produces measurable attenuation of empathy in response to politically charged or system-implicating stimuli. These effects were further visualized in a histogram (

Figure 3) which demonstrated that systemic suffering responses displayed broader dispersion and a lower central tendency, while non-systemic responses clustered more tightly around higher values. This suggests that systemic suffering, given its socio-political salience, may exhibit greater sensitivity to ideological priors, resulting in increased variability in empathic response.

Empathic response to non-systemic suffering revealed a relatively uniform topological profile with minimal curvature, reflecting weak modulation by FPAI. The gradient across the ideological-physiological parameter plane was notably shallow, indicating that responses to politically neutral suffering may be less influenced by internal ideological or physiological configurations. The mean empathic response for non-systemic suffering remained stable across individuals with a substantially lower standard deviation, supporting the interpretation of this region as a topologically flat segment of the empathic surface. In these regions, geodesic distances are short and curvature is near zero, facilitating unimpeded emotional access and consistent affective responses across the sample. This divergence in surface geometry—curved for systemic, flat for non-systemic—demonstrates the structured nature of empathic modulation. See

Figure 4 for an illustrative example.

Overall, our simulations point towards empathic responses not being evenly distributed across contexts or individuals, but instead emerging from structured interactions among ideological priors, physiological modulation and prosocial dispositions.

Conclusions

By embedding belief systems and stress factors into a continuous geometric space, we assessed the value of topological formalization as a method for analyzing affective bias and perceptual warping. We provided a mathematically grounded, topological account of empathy, revealing how ideological beliefs and physiological states may shape the accessibility and modulation of affective responses. Our simulations show that empathic responses to systemic suffering are significantly more sensitive to variations in the Affective-Ideological Polarization Factor (FPAI) than responses to non-systemic suffering (Tesi & Passini, 2025; Choma et al., 2022). Specifically, empathic intensity decreased as FPAI increased, with a significant mean difference between systemic and non-systemic suffering responses. This suggests that ideological priors and physiological states act not as linear dampeners, but as nonlinear structural deformations within an affective manifold (Barrett et al., 2025; Keysers et al., 2024). In turn, the stability of responses in non-systemic contexts supports the prediction of a flatter, ideologically neutral region in the empathic topology. These findings suggest that empathy is not a uniform or spontaneous reflex, but a shaped and context-dependent function emerging from structured internal constraints and affective configurations (Zaki, 2020).

To illustrate the framework in practice, we present a case example showing how the interaction of physiological dimensions—Belief in a Dangerous World (BDW), stress reactivity (PSRS), and pathogen disgust sensitivity (PVD)—can influence individual differences in empathic engagement during a public health emergency. By viewing these traits as a vector, we better understand why people differ in their capacity to relate to others’ experiences under the same stressful conditions. During a global pandemic, public health officials notice wide variation in citizens’ empathy toward vulnerable populations. Consider Jordan, a 35-year-old schoolteacher, whose psychological profile reflects a high vector across three physiological dimensions: b = high BDW, s = high PSRS, and d = high PVD. Jordan perceives the world as dangerous (high BDW), experiences intense emotional responses to stress (high PSRS), and is highly sensitive to contamination risks (high PVD). While he rigorously follows health guidelines, his intense internal reactivity also leads to emotional distancing. He struggles to empathize with those who resist restrictions, not out of indifference, but due to a cognitive-emotional overload that short-circuits his empathic engagement. In contrast, his colleague Ava, whose physiological profile is lower on all three dimensions, maintains a steadier emotional baseline. She expresses empathy not only toward immunocompromised individuals but also toward those struggling with compliance, recognizing their socioeconomic and psychological challenges. This example shows how the interaction of BDW, PSRS, and PVD shapes not only protective behavior but also one’s ability to emotionally resonate with others. Empathy, in this light, is not just a social virtue, rather it stands for a dynamic response shaped by deeper affective and perceptual systems.

Our topologically informed model of empathy integrates ideology, physiology and prosocial disposition within a unified and dynamic affective surface. The advantage of this framework lies in its capacity to integrate cognitive, emotional and bodily dimensions into a continuous representational structure, addressing a fundamental limitation of current psychological models—namely, their inability to capture the nonlinear, multidimensional and ideologically filtered structure of affective engagement. Unlike linear or modular approaches, which conceptualize empathy as a trait or dual-process response (Friston et al., 2022), our model treats it as a geometrically constrained field, shaped by curvatures and gradients that reflect internal biases and contextual salience (Briganti et al., 2024; Mohanta et al., 2024). This formalization provides a language for articulating affective occlusion, rigidity and resonance, i.e., dimensions that remain obscure in traditional neuroimaging or psychometric paradigms.

Several limitations warrant mention. First, the parameters and weights used in constructing the physiological vector (BDW, PSRS, PVD) are theoretically informed but not empirically calibrated, limiting the predictive power of the model. Second, the model is static and does not account for dynamic processes or feedback loops such as habituation to stress, social reinforcement or desensitization, which can significantly alter psychological responses over time. Third, it assumes continuous differentiability in trait-behaviour relationships, yet human emotions and decisions often involve discrete thresholds or tipping points that this model cannot capture. Fourth, the model operates at the individual level and fails to integrate network-level or collective dynamics like shared narratives, media ecosystems or social identities, which may play crucial roles in shaping behaviour (Nir & Halperin, 2025; Goldenberg et al., 2025). Fifth, each component is treated as a scalar value ignoring potential directionality, intensity gradients or multidimensional interactions. Future models could benefit from incorporating tensorial variable and, nonlinear cross-interactions to better reflect the complexity of human affect.

Our vector-based framework holds potential for a range of applied domains lile public policy, education, therapy and social communication, by modeling empathy as a dynamically modulated surface shaped by ideological priors, physiological sensitivity and prosocial traits. This allows for context-sensitive strategies reflecting individual differences in affective accessibility. For example, individuals high in BDW and PVD may benefit from targeted interventions emphasizing relational safety and empathic narratives (Zebarjadi et al., 2022). In polarized contexts, the model may help identify affective barriers to intergroup empathy and support cognitive reframing strategies (Goldenberg et al., 2025).

Several testable experimental hypotheses arise from our framework. Individuals high across the full vector may exhibit stronger autonomic responses (e.g., elevated heart rate variability or pupil dilation) during empathic tasks (Zhou & Jenkins, 2023). These individuals may display reduced spontaneous empathic concern under ambiguous or ideologically incongruent social cues. Still, targeted narrative interventions, especially those aimed at recontextualizing perceived threat, could reduce defensive closure and increase empathic flexibility in high-BDW subjects (Wang et al., 2024; Bloy et al., 2025). Next, integrating real-time physiological tracking with ideological profiling may enable predictive, individualized interventions based on adaptive affective technologies capable of addressing specific empathic bottlenecks.

Computationally, our model supports the use of topological data analysis and manifold learning to extract empathic geometries from high-dimensional data (Aldar et al., 2025). Longitudinal research could track changes in empathic curvature following trauma, social transitions, or ideological shifts (Levy et al., 2024). Phenomena like empathic hysteresis, where emotional responses lag behind external change due to topological inertia, may explain difficulties in adjustment during collective transitions. In these cases, moral directionality becomes distorted and empathy may be selectively blocked or attenuated based on ideological misalignment. This anisotropic configuration of the empathic space may reflect a fundamental shift in affective accessibility, distributing empathy not uniformly but in alignment with directional moral priors

Our model also frames resonance failures such as depersonalization or emotional numbing as disruptions in predictive affective cycles. Here, empathy may collapse or become directionally distorted by ideological misalignment. Incorporating information-theoretic metrics like Kullback–Leibler divergence could refine our ability to quantify empathic distortion and bias magnitude across cognitive domains. Future developments may enhance our framework through the integration of information-theoretic metrics such as Kullback–Leibler divergence or Fisher information, enabling quantitative characterization of empathic distortion and emotional prediction error. These refinements would support a more granular understanding of affective asymmetries, allowing researchers to assess not only the presence of empathic bias but the magnitude and informational structure of that bias across cognitive and ideological dimensions.

Taken together, these potential applications and research directions underscore the utility of modeling empathy as a structured, deformable field that is shaped, warped and sometimes blocked by layered individual and social constraints.

In conclusion, our vector-based approach reframed empathy as a dynamic, embodied construct shaped by underlying sensitivities, rather than a fixed moral trait. The central research question examined whether physiological traits, conceptualized as components of a multidimensional vector, can more effectively predict individual differences in empathic and affective responses when considered in interaction rather than isolation. Our findings suggest that the interplay among these physiological dimensions provides a powerful methodological lens for understanding variability in empathy, specifically, why some individuals exhibit heightened empathic inhibition or amplification in response to emotional or socially salient cues. By doing so, our approach paves the way to research, targeted intervention and informed public discourse aimed at fostering emotional understanding across social, ideological and cultural divides.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Authors.

Consent for publication: The Authors transfer all copyright ownership in the event the work is published. The undersigned authors warrant that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of data and materials: all data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests: The Authors do not have any known or potential conflict of interest, including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence, their work.

Authors' contributions: The Authors equally contributed to: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtaining funding, administrative, technical and material support and study supervision.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process: During the preparation of this work, the Authors used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the Authors reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Acknowledgments: none.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Aldar, L., Pliskin, R., Hasson, Y., & Halperin, E. (2025). Intergroup psychological interventions highlighting commonalities can increase the perceived legitimacy of critical voices. Communications Psychology, 3, Article 63. [CrossRef]

- Altemeyer, B. (1996). The Authoritarian Specter. Harvard University Press. Archive.org+24Harvard University Press+24SciSpace+24.

- Amari, S., & Nagaoka, H. (2000). Methods of Information Geometry. American Mathematical Society.

- Ammons, J., Shakya, S., & Zhukov, K. (2025). Covert regime change and ideology. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Atia, R., Balmas, M., Harel, T. O., & Halperin, E. (2025). Effects of framing counter-stereotypes as surprising on rethinking prior opinions about outgroups: The moderating role of political ideology. Media Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L. F., Atzil, S., Bliss-Moreau, E., & Westlin, C. (2025). The theory of constructed emotion: More than a feeling. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 20(3), 392–420. [CrossRef]

- Berthet, V., Teovanović, P., & de Gardelle, V. (2024). A common factor underlying individual differences in confirmation bias. Scientific Reports, 14, Article 27795. [CrossRef]

- Bhateri, & Kataria, H. (2024). A conceptual study on empathy. Indian Journal of Psychology, Book No.07 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/391605350.

- Bloy, L., Halperin, E., Nir, N., & Malovicki-Yaffe, N. (2025). Powerful victims: A dynamic approach to competitive victimhood between high- and low-power groups. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 28(2), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Briganti, G., Decety, J., Scutari, M., McNally, R. J., & Linkowski, P. (2024). Using Bayesian networks to investigate psychological constructs: The case of empathy. Psychological Reports. [CrossRef]

- Cawvey, M. (2022). Extraversion and external efficacy: The moderating role of corruption. Political Psychology. [CrossRef]

- ogitate Consortium, Ferrante, O., Gorska-Klimowska, U., Henin, S., Hirschhorn, R., Khalaf, A., et al. (2025). Adversarial testing of global neuronal workspace and integrated information theories of consciousness. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Do Carmo, M. P. (1992). Riemannian Geometry. Birkhäuser: Boston, Basel, Berlin. ISBN-13 : 978-0817634902.

- Dobbs, M., DeGutis, J., Morales, J., Joseph, K., & Swire-Thompson, B. (2023). Democrats are better than Republicans at discerning true and false news but do not have better metacognitive awareness. Communications Psychology, 1, Article 46. [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, A., Pinus, M., Cao, Y., Halperin, E., Coman, A., & Gross, J. J. (2025). Emotion regulation contagion drives reduction in negative intergroup emotions. Nature Communications, 16, Article 1387. [CrossRef]

- 16. Gromov, Mikhael. Partial Differential Relations. Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, vol. 9. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, London, Paris, and Tokyo: Springer-Verlag, 1986.

- Gur, T., Hameiri, B., & Maaravi, Y. (2024). Political ideology shapes support for the use of AI in policy-making. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 7, Article 1447171. [CrossRef]

- Han, J. (2025). Characteristics of digital capitalist ideology and its implications. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Literature, Language and Culture Development.

- Hebel-Sela, S., Hameiri, B., Moore-Berg, S., & Saxe, R. (2025). Virtual contact improves intergroup relations between non-Muslim American and Muslim students from the Middle East, North Africa and Southeast Asia in a field quasi-experiment. Communications Psychology, 3, Article 218. [CrossRef]

- Hjeij, M., & Vilks, A. (2023). A brief history of heuristics: How did research on heuristics evolve? Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10, Article 64. [CrossRef]

- Hopp, F. R., Amir, O., Fisher, J. T., Grafton, S., Sinnott-Armstrong, W., & Weber, R. (2023). Moral foundations elicit shared and dissociable cortical activation modulated by political ideology. Nature Human Behaviour. [CrossRef]

- Keysers, C., Silani, G., & Gazzola, V. (2024). Predictive coding for the actions and emotions of others and its deficits in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 167, 105877. [CrossRef]

- Kluge, A., Somila, N., Lankinen, K., & Levy, J. (2024). Neural alignment during outgroup intervention predicts future change of affect towards outgroup. Cerebral Cortex, 34, bhae125. [CrossRef]

- Laukkonen, R. E., Kaveladze, B. T., Protzko, J., Tangen, J. M., von Hippel, W., & Schooler, J. W. (2022). Irrelevant insights make worldviews ring true. Scientific Reports, 12, Article 2075. [CrossRef]

- Levy, J., Kluge, A., Hameiri, B., Lankinen, K., Bar-Tal, D., & Halperin, E. (2024). The paradoxical brain: Paradoxes impact conflict perspectives through increased neural alignment. Cerebral Cortex, 34, Article bhae353. [CrossRef]

- Liew, M., Larsen, E. M., Katz, J., Donaldson, K. R., Serody, M. R., & Mohanty, A. (2024). Acquiescing to intuition in individuals prone to delusions: Alterations in dual processes and cognitive control. Scientific Reports, 14, Article 25831. [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, S., Cleveland, D. M., Afrasiabi, M., Rhone, A. E., Górska, U., Cooper Borkenhagen, M., et al. (2024). Traveling waves shape neural population dynamics enabling predictions and internal model updating. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Nir, N., & Halperin, E. (2025). Politically-targeted intergroup interventions promote social equality and engagement. Communications Psychology, 3, Article 69. [CrossRef]

- Parr, T., Pezzulo, G., & Friston, K. J. (2022). Active inference: The free energy principle in mind, brain and behavior. The MIT Press. [CrossRef]

- Pedram, A., Besaga, V. R., Gassab, L., Setzpfandt, F., & Müstecaplıoğlu, Ö. E. (2024). Quantum estimation of the Stokes vector rotation for a general polarimetric transformation. New Journal of Physics, 26, 093033. [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2022). Accuracy prompts are a replicable and generalizable approach for reducing the spread of misinformation. Nature Communications, 13, Article 2333. [CrossRef]

- Pfänder, J., & Altay, S. (2025). Spotting false news and doubting true news: A systematic review and meta-analysis of news judgements. Nature Human Behaviour, 9, 688–699. [CrossRef]

- Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741–763.

- Prike, T., Butler, L. H., & Ecker, U. K. H. (2024). Source-credibility information and social norms improve truth discernment and reduce engagement with misinformation online. Scientific Reports, 14, Article 6900. [CrossRef]

- Salatino, A., Prével, A., Caspar, E., & Lo Bue, S. (2025). Influence of AI behavior on human moral decisions, agency and responsibility. Scientific Reports, 15, Article 12329. [CrossRef]

- Tesi, A., & Passini, S. (2025). Why don’t we care about others? A closer look at indifference through the lens of the dual process model and moral foundations theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 55(2), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Traberg, C. S., Harjani, T., Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2024). The persuasive effects of social cues and source effects on misinformation susceptibility. Scientific Reports, 14, Article 4205. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Yang, Q., Yu, X., & Hu, L. (2024). Effects of adolescent empathy on emotional resilience: The mediating role of depression and self-efficacy and the moderating effect of social activities. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 228. [CrossRef]

- Zaki, J. (2020). The war for kindness: Building empathy in a fractured world. Crown Publishing.

- Zebarjadi, N., Hameiri, B., Kluge, A., & Halperin, E. (2022). Examining implicit neural bias against vaccine hesitancy. Social Neuroscience, 17(6), 601–615. [CrossRef]

- Zebarjadi, N., Kluge, A., & Adler, E. (2024). New vistas for the relationship between empathy and political ideology. eNeuro. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., & Jenkins, A. C. (2023). Social influence modulates the neural computation of value. Nature Neuroscience, 26, 1129–1138.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).