Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

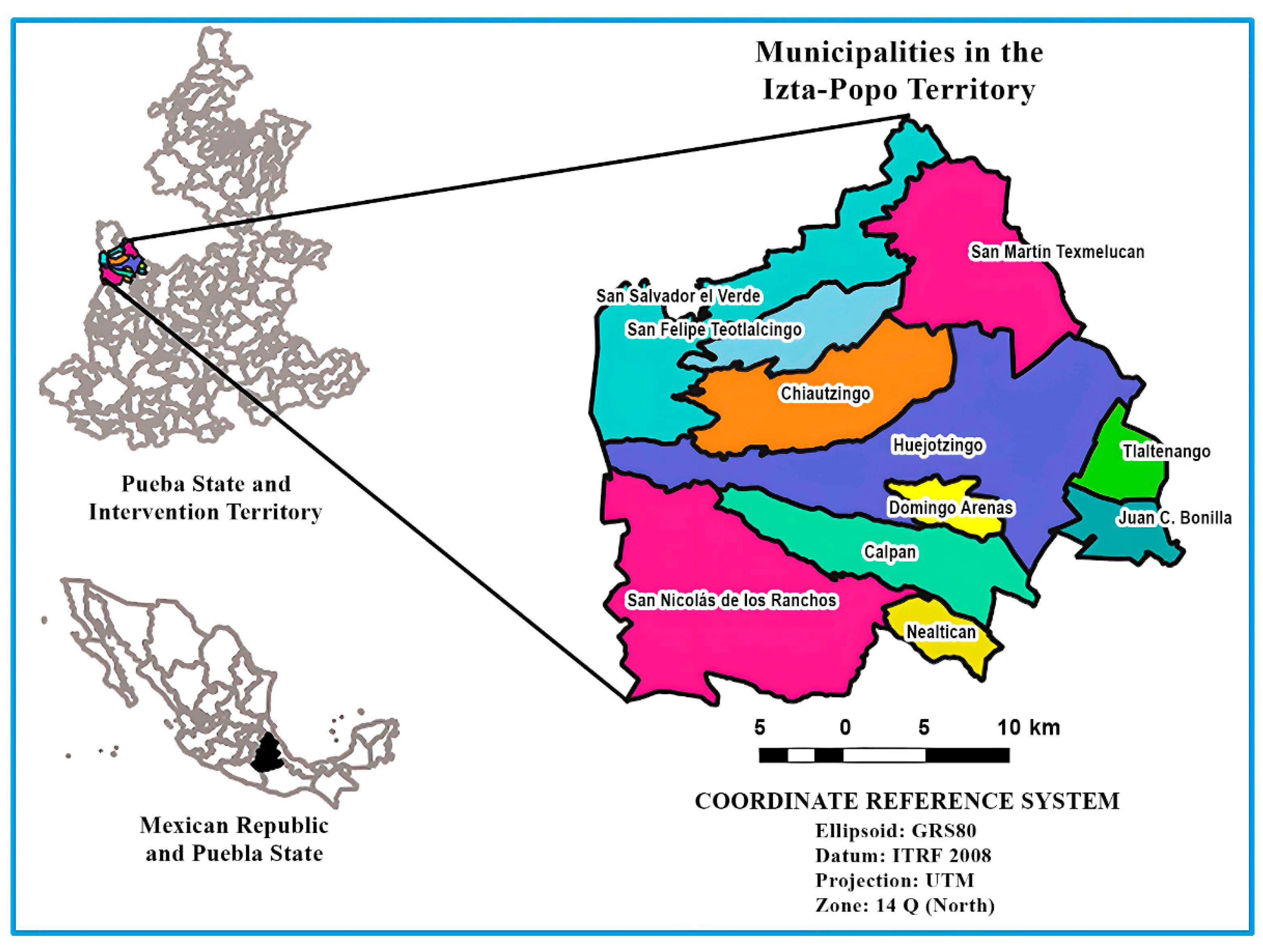

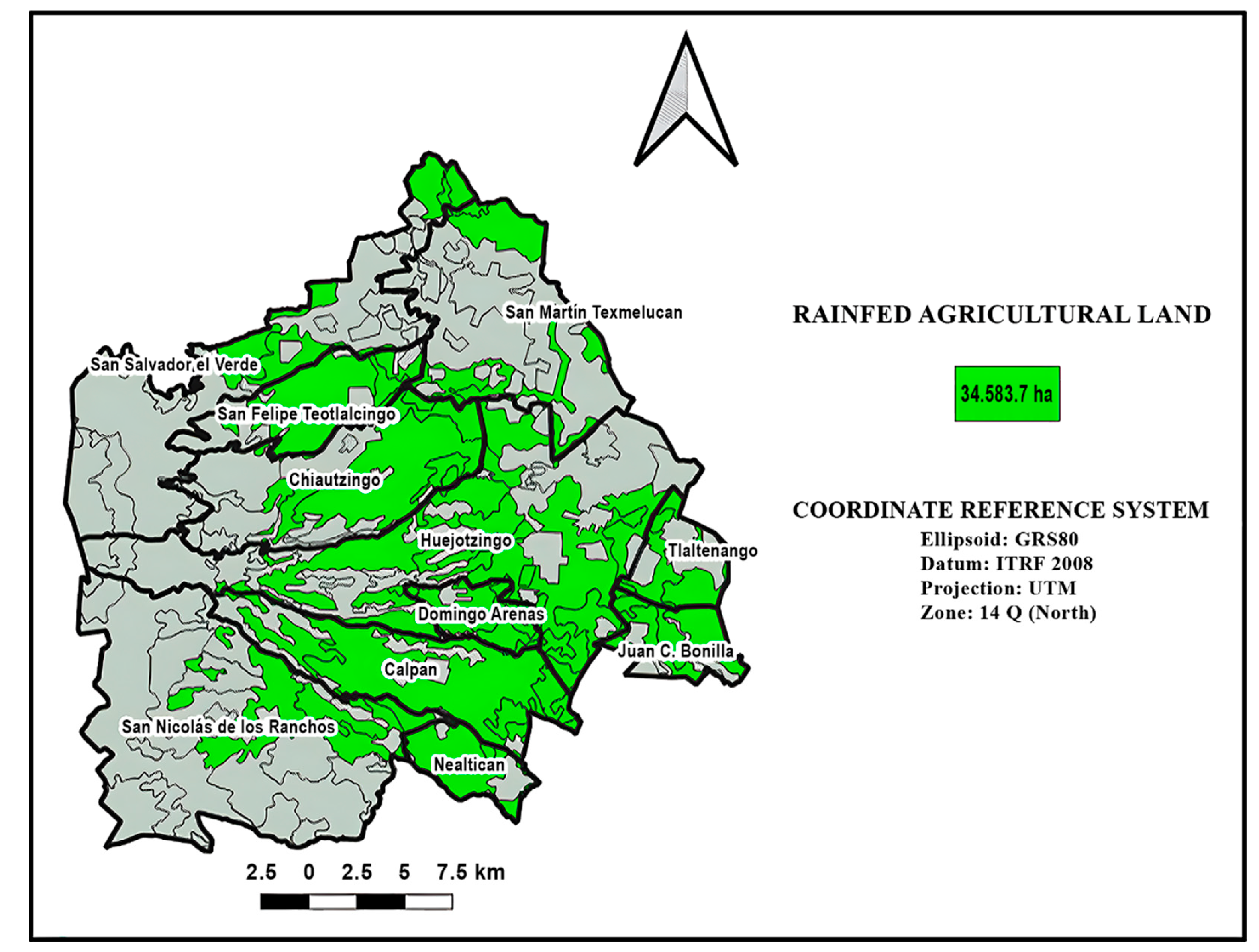

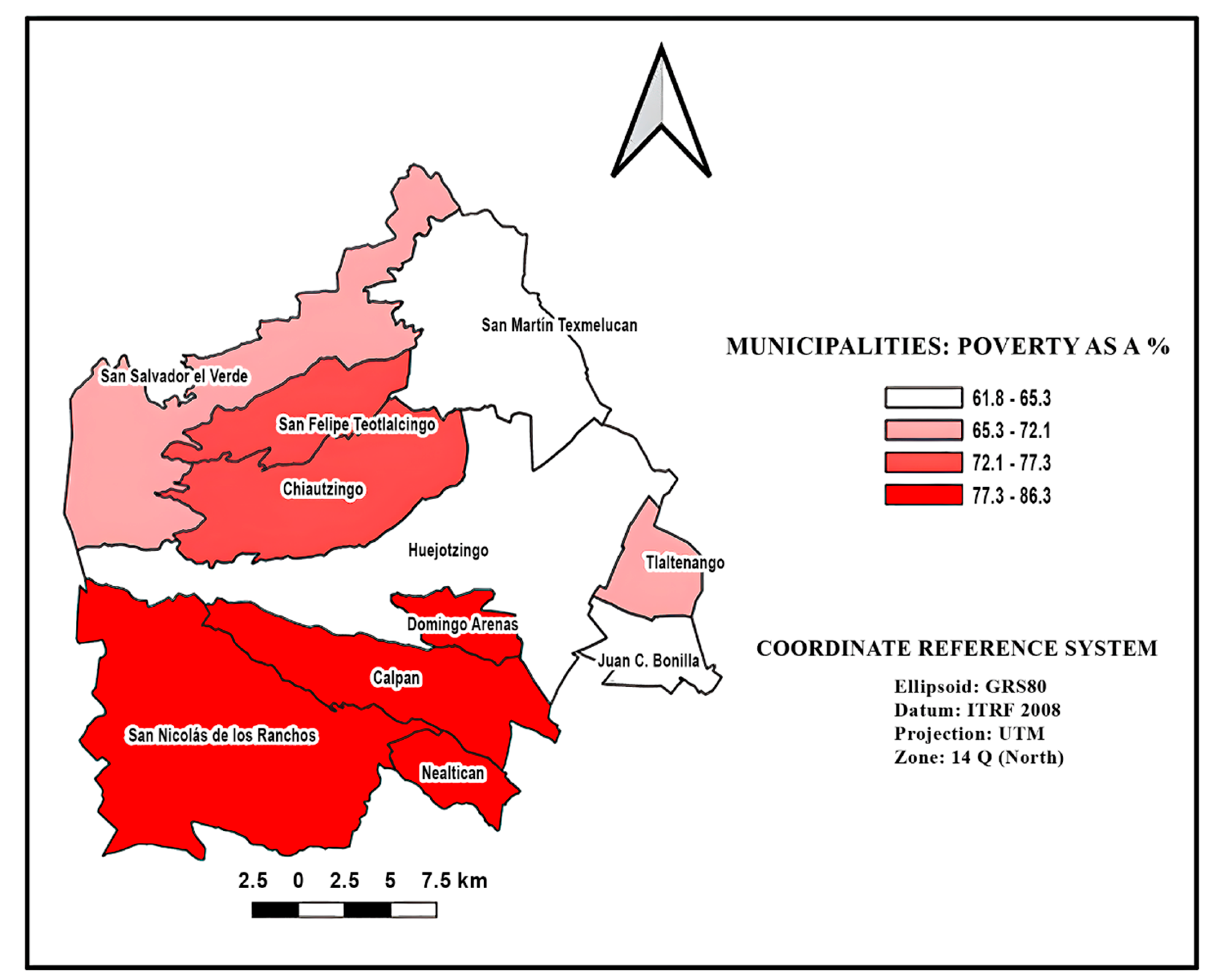

1.1. Intervention Territory

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

2.1.1. The WWP Model, PRIAs and Food Systems

2.1.2. Agri-Food Chain Models

3. Results

3.1. Case 1: Agri-food chain maize-bean guide bean association

3.1.1. Relationship of the family unit to the CFS-RAI principle

3.1.2. Characteristics of the Family Production Unit (FPU)

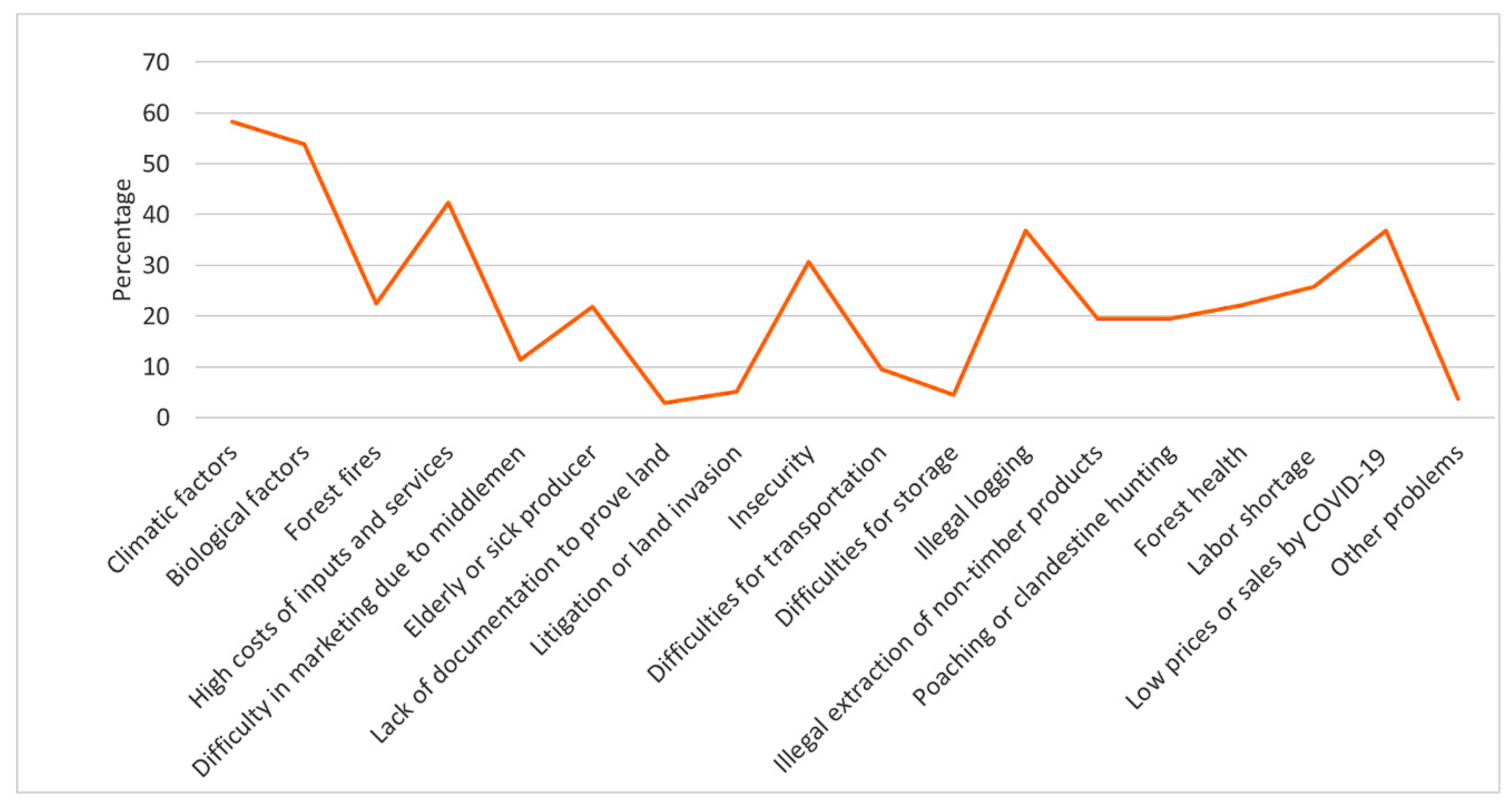

3.1.3. Production, a Component of the Corn-Beans and Ayocote Agri-Food Chain

3.1.4. Processing, Transformation

3.1.5. Commercialization, Marketing

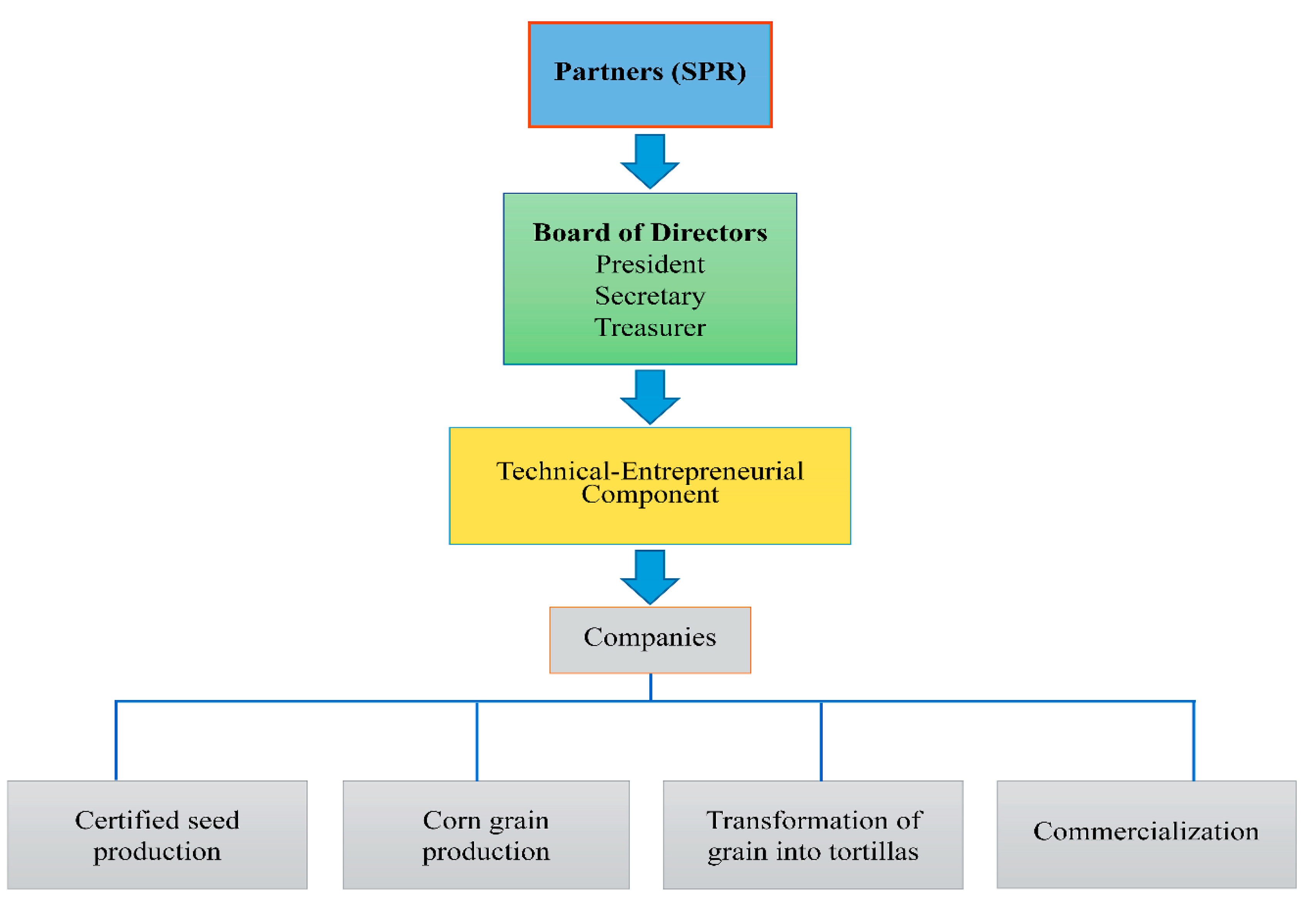

3.2. Case 2: Corn Agri-Food Chain and its Transformation Into Tortillas Through a Rural Production Society

3.2.1. Personal Characteristics of the Members of the Association

3.2.2. Production, Transformation and Commercialization; Components of the Maize Agri-Food Chain. The Group's Relationship with the CFS-RIA Principles

3.2.3. Seed Production and Commercial Plantings

3.2.4. Transformation and Commercialization

3.3. Case 3. Agri-Food Chain of Maize Produced at the Family Level, Transformed and Marketed Through a Cooperative

3.3.1. Relationship of the Cooperative's Activities with the CFS-RIA

3.3.2. Production

3.3.3. Transformation

3.3.4. Commercialization

3.4. Comparison of the 3 Agri-Food Chain Cases of the Izta-Popo Valley in Puebla

| A. Maíz-Frijol Guía | SPR Campo Lima | C. Guardianes Calpan | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Huejotzingo | Tlaltenango | Calpan |

| Irrigation | rainfed and well | well and rainfed | rainfed and well |

| Surface area | 6 ha | 45 ha | 8 ha |

| Members | 5 | 7 | 17 |

| Average age | 49 years | 46 years | 55 years |

| Schooling | 6 years | 8 years | 9 years |

| Production | MIAF* | seed, grain and corn | fruits, chile poblano |

| Transformation | tlacoyos y gorditas | tortilla de nixtamal | chiles en nogada, others |

| Marketing | local markets | tortillería shop, stores | restaurants, fairs |

| Production cycles | 2 de 6 months | 2 de 6 months | 3 de 4 months |

| Contract labor | 86 | 90 | 40 |

| Cost / Benefit | 3.5 | 3.4 | 4 |

| Associative figure | Family Unit | Rural Production Society | Cooperative |

3.5. Relationship Between the Application of the CFS-RIA Principles and Agri-Food Models

3.6. Relationship of the Application of the Working With People Model in Each Agri-Food Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI Resultados Oportunos del Censo Agropecuario 2022 Puebla, Boletín de Comunicado de Prensa; INEGI: México, 2023; p. 8;

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI Resultados Oportunos del Censo Agropecuario 2022 Puebla, Presentación; INEGI: México, 2023; p. 8;

- Regalado, J.; Pérez-Ramírez, N.; Ramírez Juárez, J.; Méndez Espinoza, J.A. Los Grupos de Acción y La Aplicación de Tecnología de Alta Productividad Para Maíz de Secano En Localidades Del Plan Puebla, México. lgr 2021, 34, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Carmenado, I.D.L.; Becerril-Hernández, H.; Rivera, M. La agricultura ecológica y su influencia en la prosperidad rural: visión desde una sociedad agraria (Murcia, España). Agrociencia 2016, 50, 375–389. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla, A.; de los Ríos, I.; Salvo, M. Working With People (WWP) in Rural Development Projects: A Proposal from Social Learning. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural 2013, 10, 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.E. El concepto de “institución”: usos y tendencias. Revista de estudios políticos 1962, 1. [Google Scholar]

- MacIver, R.M.; Page, C.H. Society. An Introductory Analysis; 1957th ed.; Macmillan & Co LTD.: London, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, G.M. ¿Qué son las instituciones? Rev.CS 2011, 17–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño Velásquez, E.; Regalado López, J.; Hernández González, T. La Asociación Campesina Independiente y Sus Relaciones Con El Estado e Instituciones. Regiones Revista Interdisciplinaria en Estudios Regionales 1998, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Comité de Seguridad Alimentaria Mundial (CSA) Principios para la Inversión Responsable en la Agricultura y los Sistemas Alimentarios 2014.

- García Winder, M.; Riveros, H.; Pavez, I.; Rodríguez, D.; Lam, F.; Arias Segura, J.; Herrera, D.; Agricultura (IICA), I.I. de C. para la Cadenas Agroalimentarias : Un Instrumento Para Fortalecer La Institucionalidad Del Sector Agrícola y Rural; COMUNIICA, 5.; Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura (IICA), 2009; ISBN 978-92-9248-146-9.

- Albisu, L.M. Las cadenas agroalimentarias como elementos fundamentales para la competitividad de los productos en los mercados. Revista Mexicana de Agronegocios 2011, 28, 451–452. [Google Scholar]

- Agencia Catalana de Seguridad Alimentaria La Cadena Alimentaria. Principios y los requisitos generales de la legislación alimentaria. Reglamento (CE) No 178/2002 Available online:. Available online: http://acsa.gencat.cat/es/seguretat_alimentaria/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ramírez-Juárez, J. Régimen Alimentario y Agricultura Familiar. Elementos Para La Soberanía Alimentaria. Remexca 2023, 14, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moctezuma-López, G.; Espinosa-García, J.A.; Cuevas-Reyes, V.; Jolalpa-Barrera, J.L.; Romero-Santillán, F.; Vélez-Izquierdo, A.; Bustos Contreras, D.E. Innovación tecnológica de la cadena agroalimentaria de maíz para mejorar su competitividad: estudio de caso en el estado de Hidalgo. Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas 2010, 1, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI Mapa digital de México para escritorio versión 6.3. Proyectos. Proyecto Básico de Información 2020 Available online:. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/mapadigital/#Descargas (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI Compendio de información geográfica municipal 2010, Huejotzingo, Puebla 2010.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI Compendio de información geográfica municipal 2010, Chiautzingo, Puebla 2010.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI Compendio de información geográfica municipal 2010, Tlaltenango, Puebla. 2010.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI Compendio de información geográfica municipal 2010, San Salvador el Verde, Puebla. 2010.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI Compendio de información geográfica municipal 2010, Juan C. Bonilla, Puebla. 2010.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI Compendio de información geográfica municipal 2010, Calpan, Puebla. 2010.

- ADICAP S.A de C.V. Atlas de Riesgos Del Municipio de San Martín Texmelucan; ADICAP & Gobierno Municipal de San Martín Texmelucan: San Martín Texmelucan, Puebla, México, 2018.

- Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural del Gobierno de México Sistema de Información Agroalimentaria de Consulta, SIACON. Available online: http://www.gob.mx/siap/documentos/siacon-ng-161430 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/#datos_abiertos (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Consejo Nacional de Población del Gobierno de México, CONAPO Índice de marginación (carencias poblacionales) por localidad, municipio y entidad. Available online: https://datos.gob.mx/busca/dataset/indice-de-marginacion-carencias-poblacionales-por-localidad-municipio-y-entidad (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social, CONEVAL Medición de La Pobreza Por Grupos Poblacionales a Escala Municipal 2010, 2015 y 2020 Available online:. Available online: https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/Paginas/Pobreza_grupos_poblacionales_municipal_2010_2020.aspx (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Méndez Espinoza, J.A.; Valencia Bastida, I.; Ramírez Juárez, J.; Pérez Ramírez, N.; Regalado López, J.; Hernández Flores, J.A. Caracterización y Tipificación de Las Unidades Domésticas Que Participan En La Cadena Agroalimentaria Maíz-Tlacoyo. ASYD 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimone-Celorio, J.A.; Regalado-López, J.; Gallego-Moreno, F.J.; Pérez-Ramírez, N.; Méndez-Espinoza, J.A. Comparative Analysis of Four Corn (Zea Mays L.) Varieties, Transformed from Grain Corn into Tortilla. AP 2024, 17, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado-López, J.; Castellanos-Alanis, A.; Pérez-Ramírez, N.; Méndez-Espinoza, J.A.; Hernández-Romero, E. Modelo Asociativo y de Organización Para Transferir La Tecnología Milpa Intercalada En Árboles Frutales (MIAF). Estudios Sociales 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coller, X. Estudio de Casos, Madrid, Cuadernos Metodológicos; Centro de Investigaciones sociológicas.; Madrid, España, 2005; Vol. 30; ISBN 978-84-7476-387-4.

- Ponce Andrade, A.L. El Estudio de Caso Múltiple. Una estrategia de Investigación en el ámbito de la Administración. Revista Publicando 2018, 5, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bulman, A.; Cordes, K.Y.; Mehranvar, L.; Merrill, E.; Fiedler, Y. Guía sobre incentivos para la inversión responsable en la agricultura y los sistemas alimentarios. Roma, FAO y Centro Columbia sobre Inversión Sostenible. Roma.; 1st ed.; FAO: Roma, Italia, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-134575-7. [Google Scholar]

- Regalado López, J.; Mendoza, R.; Ríos Carmenado, I. de los; Díaz Puente, J.M. Adaptación del modelo leader en el territorio huejotzingo, puebla: una nueva propuesta de desarrollo rural local. In Proceedings of the Actas del XV Congreso Internacional de Ingeniería de Proyectos | XV Congreso Internacional de Ingeniería de Proyectos | 06/07/2011 - 08/07/2011 | Huesca, España; E.T.S.I. Agrónomos (UPM): España, 2011; pp. 1533–1545. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla Montero, A.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Yagüe, B. Trabajando con la gente en los proyectos de desarrollo rural: una conceptualización desde el Aprendizaje Social. In Modelos para el desarrollo rural con enfoque territorial en México; Altres Costa-Amic Editores, S.A. de C.V.: México, 2011 ISBN 978-968-839-585-1.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía, Estadística e Informática, INEGI Panorama Sociodemográfico de Puebla. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. 2021; 1st ed.; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía de México: México, 2021; Vol. 1, ISBN 304.601072 (en trámite). [Google Scholar]

- Turrent Fernández, A.; Cortés Flores, J.I.; Espinosa Calderón, A.; Hernández Romero, E.; Camas Gómez, R.; Torres Zambrano, J.P.; Zambada Martínez, A. MasAgro o MIAF ¿Cuál Es La Opción Para Modernizar Sustentablemente La Agricultura Tradicional de México. Remexca 2017, 8, 1169–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centro Internacional de maíz y Trigo. CIMMYT; Ministry of Agriculture, Government of Mexico; Government of the State of Puebla The Puebla Project: Seven Years of Experience, 1967-1973; 1st ed.; CIMMYT: Puebla, México, 1974; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal-Rodríguez, J.; Villanueva-Verduzco, C.; Sahagún-Castellanos, J.; Acosta Ramos, M.; Martínez Martínez, L.; Espinosa Solares, T. Ensayos de producción de huitlacoche (Ustilago maydis Cda.) hidropónico en invernadero. Revista Chapingo. Serie horticultura 2010, 16, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés Flores, J.I.; Turrent Fernández, A. La Milpa Intercalada en Árboles Frutales (MIAF) Tecnología multiobjetivo para el desarrollo de la agricultura en laderas; Colegio de Postgraduados: México, 2021; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ordoñez-Ovalle, J.; Gómez-Martínez, E.; Soto-Pinto, L.; González-Santiago, M.V. El sistema milpa intercalado con árboles frutales (MIAF): evaluación agroecológica a diez años de su implementación en Chamula, Chiapas, México. Revista Campo-Território 2022, 17, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Hernández, L.M.; Almeraya-Quintero, S.X.; Guajardo-Hernández, L. La producción de tlacoyos como alternativa de desarrollo en San Miguel Tianguizolco, Puebla, México. Agro Productividad 2017, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Cárdenas, T.; Thomé-Ortiz, H.; Ávalos De La Cruz, D.A.; Escalona-Maurice, M.; Gómez-Merino, F.C. El Tlacoyo Como Recurso Alimentario, y Su Relación Con La Oferta Turística Local: Casos Texcoco y Chiconcuac, Estado de México En México. AP 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Economía del Gobierno de México Tlaltenango: Economía, empleo, equidad, calidad de vida, educación, salud y seguridad pública Available online:. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/tlaltenango (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Cabral Martell, A. Las figuras asociativas como alternativa en los Agronegocios. Revista Mexicana de Agronegocios 2004, VIII, 378–389. [Google Scholar]

- Apolo Tortilladoras Ficha técnica de Máquina Tortilladora Apolo 30 básica 2024.

- Secretaría de Economía del Gobierno de México Calpan: Economía, Empleo, Equidad, Calidad de Vida, Educación, Salud y Seguridad Pública Available online:. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/calpan (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Littaye, A. The Role of the Ark of Taste in Promoting Pinole, a Mexican Heritage Food. Journal of Rural Studies 2015, 42, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleta, M.; Gebremedhin, B.; Hoekstra, D. Smallholder Commercialization: Processes, Determinants and Impact. Discussion Paper No. 18. Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project 2009, 55.

- Cazorla Adolfo, A.; De Los Ríos Carmenado, I. Jornadas de diálogo para la inclusión de los Principios para la Inversión Responsable en la Agricultura (IAR) y las Directrices Voluntarias de Gobernanza de la Tierra (DVGT) en el ecosistema universitario de Latinoamérica. Conclusiones; Grupo GESPLAN. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid: España, 2018; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- GESPLAN, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid Programa Internacional sobre los Principios de Inversión Responsable en la Agricultura y los Sistemas Alimentarios FAO. Valoración de Objetivos de los Principios CSA-IRA en la Tercera Edición del Programa. 2024.

- Jiménez Aliaga, R.; De Los Rios Carmenado, I.; Cazorla Montero, A.; Huamán, C.; Amparo, E. Definición de objetivos prioritarios para la implementación de los Principios CSA-IRA en la sierra central de Perú.; 2023.

- Jiménez Aliaga, R.; De Los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; San Martín Howard, F.; Calle Espinoza, S.; Huamán Cristóbal, A. Integration of the Principles of Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems CFS-RAI from the Local Action Groups: Towards a Model of Sustainable Rural Development in Jauja, Peru. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Aliaga, R.; De Los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Huamán Cristóbal, A.E.; Aliaga Balbín, H.; Marroquín Heros, A.M. Competencies and Capabilities for the Management of Sustainable Rural Development Projects in the Value Chain: Perception from Small and Medium-Sized Business Agents in Jauja, Peru. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Planning as Social Learning. Working Paper 1981, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Winch, G. Rethinking Project Management: Project Organizations as Information Processing Systems? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the PMI Research Conference; Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute: London, England, 2004.

- Midgley, J. Social Development: Theory and Practice; SAGE Publications Ltd: 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4129-4778-7. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta Mereles, M.L.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Ávila Cerón, C.A.; Castañeda Sepulveda, R. Inversión responsable en procesos de sustitución de cultivos ilícitos desde el modelo “Trabajando con Personas”: estudio de caso Guaviare (Colombia). In Proceedings of the Comunicaciones presentadas al XXVII Congreso Internacional de Dirección e Ingeniería de Proyectos, celebrado en Donostia-San Sebastián del 10 al 13 de julio de 2023; AEIPRO, Asociación Española de Dirección e Ingeniería de Proyectos: Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain, 2023; Vol. 197. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla Montero, A.; De Los Ríos Carmenado, I. Rural Development as “Working With People”: A Proposal for Policy Management in Public Domain; 1st ed.; E.T.S.I. Agrónomos (UPM): Madrid, España, 2012; ISBN 978-84-615-7154-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla-Montero, A.; De Los Ríos-Carmenado, I. From “Putting the Last First” to “Working with People” in Rural Development Planning: A Bibliometric Analysis of 50 Years of Research. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Rivera, M.; García, C. Redefining Rural Prosperity through Social Learning in the Cooperative Sector: 25 Years of Experience from Organic Agriculture in Spain. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur Nuño, C.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I. Hacia una “Gobernanza basada proyectos” desde los ODS y los criterios ASG: el caso de los Bancos de Alimentos.; Jaén, España, 2024; pp. 1775–1793.

- Requelme, N.; Afonso, A. The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture (CFS-RAI) and SDG 2 and SDG 12 in Agricultural Policies: Case Study of Ecuador. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.; Velasquez-Fernandez, A.; Rodriguez-Vasquez, M.I.; Cuervo-Guerrero, G. Territorial Analysis Through the Integration of CFS-RAI Principles and the Working with People Model: An Application in the Andean Highlands of Peru. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachipuendo, C.; Requelme, N.; Sandoval, C.; Afonso, A. Sustainable Rural Development Based on CFS-RAI Principles in the Production of Healthy Food: The Case of the Kayambi People (Ecuador). Sustainability 2025, 17, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.; Gibbon, D.P.; Gulliver, A.; Hall, M. Sistemas de Producción Agropecuaria y Pobreza: Como Mejorar Los Medios de Subsistencia de Los Pequeños Agricultores En Un Mundo Cambiante; FAO ; World Bank: Rome : Washington, D.C, 2001; ISBN 978-92-5-104627-2. [Google Scholar]

| Elements | National, México | State, Puebla |

|---|---|---|

| Total production units | 4,440,265 | 440,752 |

| Surface area for agricultural use | 26,104,422.68 | 1,015,173.77 |

| Sown area | 20,547,097.17 | 926,890.58 |

| Receiving “senior adults” support | 895,837 | 85,728 |

| Tractor use | 1,793,338 | 187,816 |

| Credit use | 265,508 | 14,437 |

| Insurance use | 78,140 | 621 |

| Agricultural Species | Planted Surface (ha) | Production | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (tons) |

Value (thousands of pesos) |

||

| Corn | 21,178.7 | 38,579.1 | 269,672.8 |

| Beans | 1,791.2 | 1,767.9 | 26,323.3 |

| Peach | 543.1 | 3,775.1 | 31,607.4 |

| Apple tree | 191.8 | 1,203.5 | 9,525.9 |

| Pear tree | 796.4 | 6,646.2 | 22,895.3 |

| Hickory | 127.0 | 534.7 | 15,673.1 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Territory | Municipality | Huejotzingo | Tlaltenango | Calpan |

| Locality | Miguel Tianguizolco | No location | San Andrés | |

| Production | Product | Corn, beans, ayocote and pumpkin. | Corn | Fruits, poblano peppers and corn |

| Farmers | 50 | 500 | 250 | |

| Surface | 100 ha | 1200 ha | 208 ha | |

| Transformation | Product | Tlacoyo and tortilla | Tortilla and tostada | Chile en Nogada |

| Families | 600 | 100 | 80 | |

| Commercialization | Points of sale | 50 markets in CDMX y Edo. de México | 280 places, e.g. Miscellaneous, schools, others. | 150 restaurants and 5 events. |

| CFS-RIA Principle | Progress Indicators* | AM α |

SL β |

GC θ |

Identified Strengths | Identified Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Contribute to food security and nutrition | ◾ Increase in corn yields per hectare. | 84 | 90 | 80 | There has been an increase in the production of corn and other staple foods, as well as an increase in crop diversification, local consumption and self-consumption of nutritious foods. | Dependence on external inputs (fertilizers and seeds) for corn. Limited access to fair markets. |

| ◾ Crop diversification through polyculture strategies. | 80 | 74 | 88 | |||

| ◾ Increased availability of food for family consumption. | 88 | 88 | 94 | |||

| ◾ Promote local consumption. | 86 | 96 | 94 | |||

| ◾ Include simple and nutritionally balanced foods in the market. | 94 | 94 | 94 | |||

| GLP** | 86 | 88 | 90 | |||

| 2. Contribute to sustainable and inclusive economic development and the eradication of poverty | ◾ Diversification of products derived from or transformed from crops (innovation). | 90 | 90 | 96 | Family income is strengthened through crop diversification and the sale of surpluses and by-products. The action groups optimize the use of resources and improve profitability in corn and polycrop production. Increased adaptation of technologies and practices to local needs. |

Prioritization of economic profitability over sustainability. Lack of access to credit or savings banks. Difficulty competing with large producers and companies, or switching to a high value-added market through product transformation. |

| ◾ Promotion of action groups. | 84 | 86 | 96 | |||

| ◾ Encourage local business relationships and improve business and production practices. | 80 | 88 | 94 | |||

| ◾ Adoption and awareness of basic sustainable practices. | 82 | 80 | 90 | |||

| GLP** | 84 | 86 | 94 | |||

| 9. Incorporate inclusive and transparent governance structures, processes, and grievance mechanisms | ◾ Creation of Territorial Action Groups (TAGs) for participatory development management. | 80 | 84 | 90 | The association of small producers is the main objective of the interventions, encouraging their participation in decision-making and their association in cooperatives or societies. The relationship with academic institutions is strengthened through research projects and field training. |

Limitations of governmental structures. Lack of formalization due to the absence of specific laws. |

| ◾ Strengthening producer organizations and strategic collaboration networks. | 78 | 92 | 94 | |||

| ◾ Sharing useful and relevant information. | 82 | 88 | 96 | |||

| ◾ Promoting mediation mechanisms to provide solutions | 84 | 86 | 94 | |||

| GLP** | 82 | 88 | 94 |

| WWP Model | Application indicator |

AM α |

SL β |

GC θ |

Identified Strengths | Identified Challenges |

| 1. Technical-Entrepreneurial Component | ◾ The participation of the technical market component in the stages of the production chain. | 74 | 82 | 98 | The application of this component is high, especially in the “Campo Lima” and “Guardianes de Saberes Sabores de Calpan” groups, because they have a high level of associativity within their groups. | Consolidate the entrepreneurial component of the Campo Lima group. Replicate the experience of the “Guardianes de Saberes y Sabores de Calpan” Cooperative in the other two agri-food cases. Generate commercial synergies among the three groups. |

| ◾ Structuring and business organization for transformation | 80 | 88 | 92 | |||

| ◾ Acceptance of strategic support from universities and their academic integration with rural groups. | 90 | 90 | 90 | |||

| ◾ Coordination of meetings as an incentive for joint actions. | 80 | 92 | 94 | |||

| ◾ Quality and standardization of the groups' products. | 88 | 96 | 94 | |||

| GLP** | 82 | 90 | 94 | |||

| 2. Ethical-Social Component | ◾ Creation of Local Action Groups (LAGs) and rural development councils. | 80 | 84 | 90 | The participation of rural groups in decision-making is promoted and gender equity is fostered, although inequalities persist. | Inequality in access to resources and opportunities. Persistence of traditional gender roles. Difficulty in achieving a balance in the participation of all stakeholders. Lack of trust in institutions and agents for dialogue. Abuse of intermediaries that affect fair trade. |

| ◾ Implementation of participatory planning processes. | 82 | 90 | 92 | |||

| ◾ Inclusion of women and young people in workshops and productive activities. | 80 | 80 | 96 | |||

| ◾ Promotion of dialogue and negotiation between stakeholders. | 82 | 84 | 86 | |||

| ◾ Approach and mediation with rural groups to promote and strengthen organizational work behavior and attitudes. | 88 | 90 | 94 | |||

| GLP** | 82 | 86 | 92 | |||

| 4. Social Learning process-approach | ◾ Use of participatory methodologies such as workshops and focus groups for group and stakeholder development. | 78 | 82 | 88 | Collective learning and the adaptation of strategies based on experience are encouraged, as well as interdisciplinary reflection and analysis of the actions undertaken. | Difficulty in systematizing information and learning. Need to strengthen monitoring and evaluation capacities. Resistance to evaluation and feedback. |

| ◾ Exchange of knowledge and experiences to promote social dynamics between producers and universities. | 92 | 90 | 90 | |||

| ◾ Participatory monitoring and evaluation of projects. | 88 | 88 | 90 | |||

| ◾ Adaptation of development models to local conditions through innovation. | 84 | 92 | 90 | |||

| GLP** | 86 | 88 | 90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).