Introduction

The supportive functions of seagrass such as habitat, shelter, and trophic provide extensive support for biodiversity (Unsworth et al., 2019). In addition, seagrass meadows also provide regulatory services such as carbon storage, nitrogen cycling and coastal protection. Literature around these services commonly suggests seagrass as their sole provider, however, it is far more likely that the responsibility for such services instead lies with its overarching holobiont assemblage (Wilkins et al., 2019).

Seagrass ameliorates surrounding sediment via oxygen expulsion from root pores (Cardini et al., 2019; Cúcio et al., 2018), allowing the formation of distinct local microenvironments where oxygen is no longer limiting (Cúcio et al., 2018). Negating oxygen limitation is key to seagrass success, as important activity by chemolithotrophic and aerobic detoxifying microorganisms are then thought to prevent die-offs through prevention of sulphide accumulation (Ugarelli et al., 2017).

Similarly, evidence suggests Zostera-mediated root exudates (formed principally of labile organic matter) attract a diverse range of heterotrophic bacteria such as Gamma and Deltaproteobacteria (Ugarelli et al., 2017;Cúcio et al., 2018). These heterotrophic bacteria then negatively influence oxygen balance, enhancing the cycling of carbon. Seagrasses also live across a range of nutrient environments from offshore and island calcareous sands low in nutrients to muddy organic rich lagoons awash with nutrients. In many parts of the world such environments have become increasingly eutrophic (Maúre et al., 2021), however seagrasses are poorly adapted to uptake of nitrate instead requiring ammonia (Burkholder et al., 2007). Cycling of this nitrate and making it more bio-available requires microorganisms, with seagrass-associated micro-organisms thought to be involved in the nitrification, denitrification and nitrogen-fixing processes (Herbert, 1999).

Z. marina root systems assemble two dis5tinct populations (i.e. microbiome) from existing sediment-microbe reservoirs: rhizosphere (surrounding roots) and endosphere (within roots) (Fitzpatrick et al., 2018). Although there is generally a limited literature into root-endosphere community diversity such as Fidalgo, et al., (2016), Garcias-Bonet et al., (2012) suggest high proportions of sulphate-reducing bacteria colonize root tissues. There is increasing evidence that these seagrass associated microbial communities change with respect to environmental differences (Kardish and Stachowicz, 2023) and may play a key role in improving the resilience of the plants to disease (Graham et al., 2024).

There are many knowledge gaps within how seagrass root-associated communities develop, with many studies being temporally isolated with a limited understanding of seagrass life history stages. Local environmental differences have been found to create rapid shifts in associated microbial community composition (Ettinger et al., 2017;Kardish and Stachowicz, 2023) with small scale spatial differences known to exist, suggesting host-selection of some functional taxa (Ettinger et al., 2017). However, no indication is made as to whether these communities persist over time within seagrass meadows, or if these microbes are involved with Z. marina development. These bacterial assemblages interact directly with Z. marina across all stages of their lifecycle. They are evident in seed germination, all subsequent successional development stages, and adult plants, whilst they have also been observed to play a role in the degradation of detrital plant matter(Turner et al., 2013;Shade et al., 2017;Fitzpatrick et al., 2018;Nelson, 2018).

Knowledge of the role of microbial communities in seagrass meadows has direct links to the emerging field of Blue Carbon, as seagrasses have the capacity to act as both sinks and sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Microbes that are involved with or influence the breakdown of organic matter, production of methane, and conversion of nitrate to nitrous oxide have potential to alter these roles (Ugarelli et al., 2017;Macreadie et al., 2019). Understanding of the drivers behind the productivity of these organisms has potential to influence how these systems are managed into the future.

The emerging view of the seagrass holobiont and the factors that influence it are also of increasing importance given the growth of activity in seagrass restoration (Unsworth et al., 2023). Failure in seagrass restoration is widespread, and in many examples there remains limited understanding as to why a project failed, and as a result many practitioners are looking at alternative explanations such as the role of the microbiome (Unsworth et al., 2019). In other marine ecological fields, such as coral reef restoration and aquaculture, there is increasing hope that probiotics can be developed that can improve growth and survival of corals, particularly in the context of extreme environmental conditions (Blackall et al., 2020;Thatcher et al., 2022). In seagrasses, if probiotics could be developed or conditions altered to facilitate improved colonisation by the most appropriate microbes then there is hope that some of the bottlenecks for seagrass restoration could be overcome (Unsworth et al., 2023). These hypothetical innovations first necessitate a better understanding as to the key functional communities and species of microbes present in seagrass at different stages of their development and in natural environments. It is also important that this understanding is developed based on an understanding of real-world field experiments as many of the experiments and studies conducted on the seagrass microbiome have bee conducted in controlled laboratory conditions.

Given the limited understanding of the seagrass microbiome with respect to different stages of life history and the recognition that filling gaps in this knowledge may help improve our understanding of blue carbon as well as the recovery and restoration of these systems, the following experiment sought to examine the seagrass microbiome at different stages of plant development. This study aimed to examine whether such a community exists within young seedlings and whether the functional role of these communities develops and changes with the age of the plant.

Materials and Methods

Study Sites

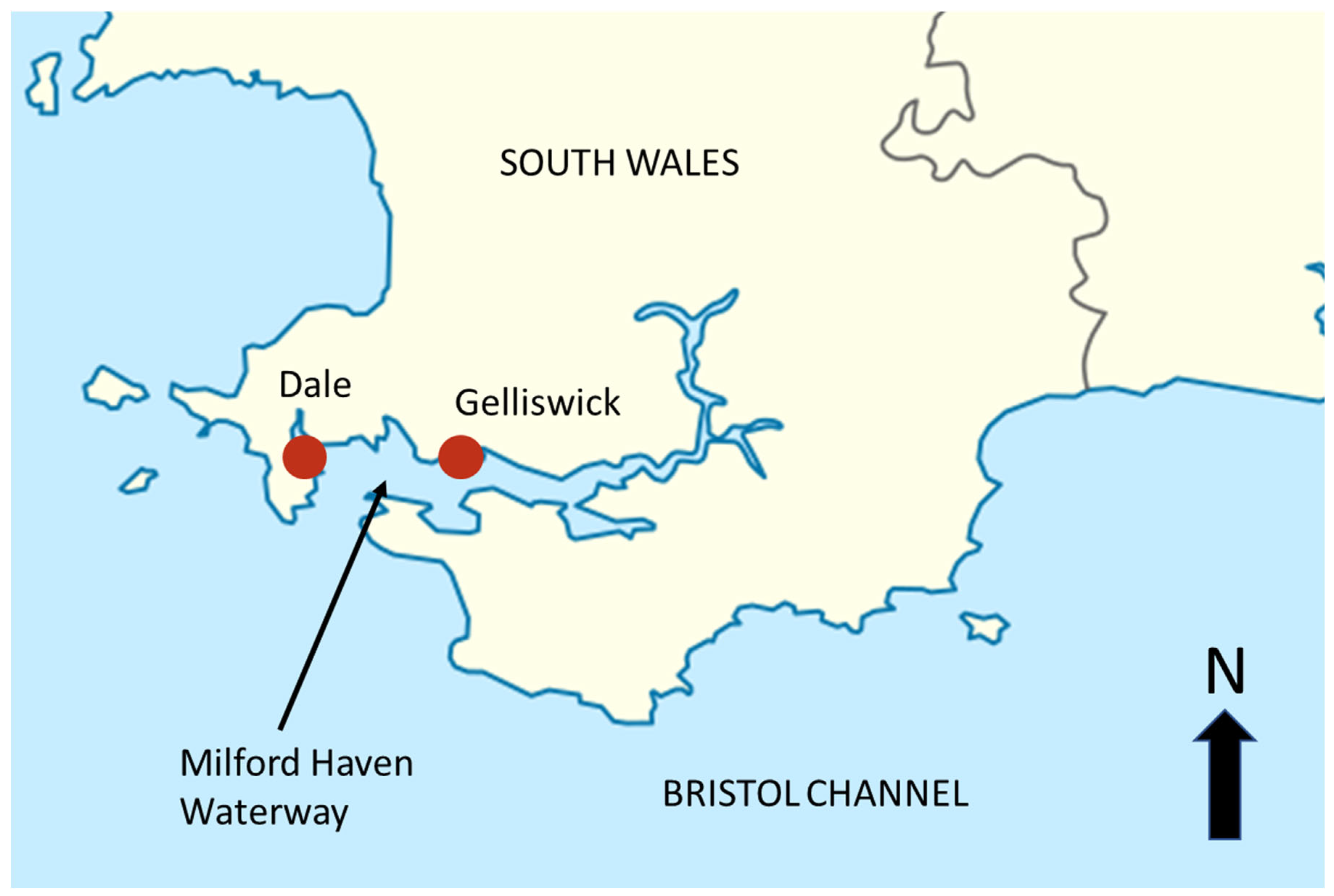

Samples of

Zostera marina and adjacent sediments associated with the plant were collected from two seagrass planting (restoration) sites and two natural seagrass meadow sites located in Milford Haven Waterway, South Wales (

Figure 1). All sites within the Milford Haven Waterway observe an annual temperature range of 8°C-17°C peaking in August (Carey et al., 2015). The temperate seagrass

Z. marina covers large areas of mostly subtidal soft sediment substrate while experiencing high water renewal with a maximum tidal range of 7.68m. Gelliswick Bay has predominantly fine-very fine sand overlying silt/clay (Carey et al., 2015). All sites associated with the Dale tidal lagoon (treatments, restoration, Dale patch) (

Figure 1.) are dominated by fine to very fine sandy sediments at depths ranging 1-3m (Unsworth et al., 2019). Existing

Z. marina meadows found in Gelliswick have been dated back over 100 years (Kay, 1998) suggesting prime conditions for seagrass growth. The Dale tidal lagoon was at the time of the study largely devoid of any seagrass except for the presence of an isolated patch of dense

Z. marina (approx. 5m

2) surrounded by bare sediment. Prospecting studies by (Unsworth et al., 2019) confirming reports from as early as the mid-1950s (Kay, 1998) as well as ratifying model outputs that predicted

Z. marina presence in this area (Brown, 2015).

Seagrass planting sites (restoration trials) located no further than 50m from the Dale patch observe very similar conditions. The restoration sites represents a random scattering of hessian bags loaded with Z. marina seeds and Z. marina-derived detrital inoculant as described by Unsworth et al. (2019). Deployment of the restoration materials (seeds) occurred during the summer of 2017. Deployment was performed by wading out on low tides with lines that were weighted down and buoyed (described in (Unsworth et al., 2022)

Figure 1.

Location of sampling sites in Milford Haven Waterway, South Wales, UK.

Figure 1.

Location of sampling sites in Milford Haven Waterway, South Wales, UK.

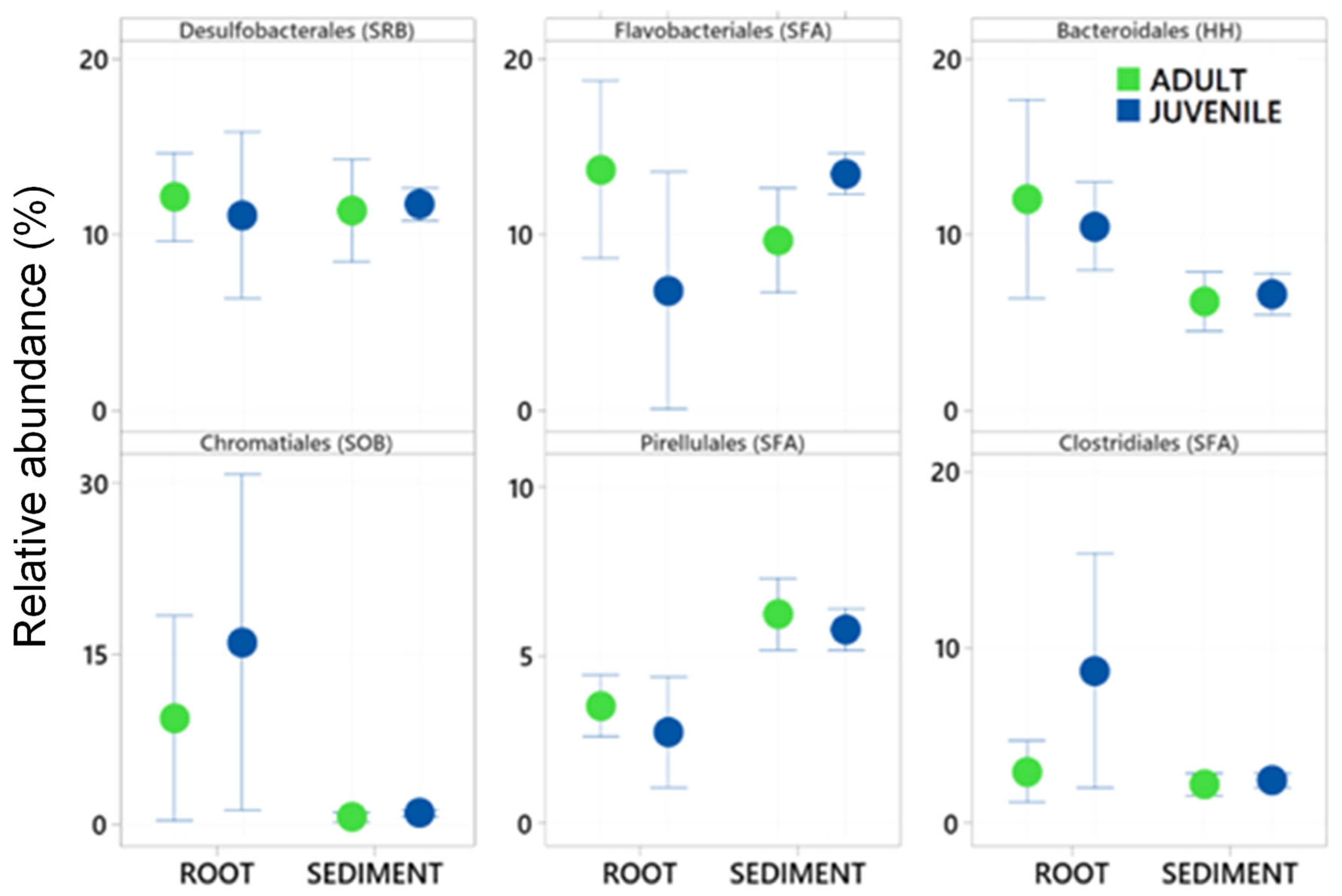

Figure 2.

Mean relative abundance ± standard deviation of the six most abundant Bacteria taxa (Order level) in 16S rRNA gene libraries generated from samples of roots and adjacent sediments of juvenile (seedlings) and adult plants of the seagrass Zostera marina planted in Dale in the Milford Haven Waterway in West Wales. Green circles are adult plants and blue circles are juvenile plants (seedlings).

Figure 2.

Mean relative abundance ± standard deviation of the six most abundant Bacteria taxa (Order level) in 16S rRNA gene libraries generated from samples of roots and adjacent sediments of juvenile (seedlings) and adult plants of the seagrass Zostera marina planted in Dale in the Milford Haven Waterway in West Wales. Green circles are adult plants and blue circles are juvenile plants (seedlings).

Sample Collection

Seagrass plants were sampled randomly from the restoration trial within their respective age ranges. Tissue from

Z. marina roots, rhizomes and associated sediments were collected in water during March, May and July 2019 (see

Table 1), with collectors wearing nitrile gloves and clear protocols ensuring no cross-contamination between samples. The base of the plant was accessed by gently loosening sediment until whole root-rhizome structure was removed. Plants were then immediately rinsed with filter sterilised saline solution of 35ppt to remove remaining sediment from the plants. Sediment samples were collected from random locations adjacent to the sampled seagrass plants. Sediment samples were collected using 5mL syringes modified with the ends cut off to form mini-corers (Surface area 1cm

2), 5 cm depth. Samples were then immediately frozen in dry-ice (-60°C) and transferred to the freezer -80

oC until extraction.

DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification and High-Throughput Sequencing

DNA extractions of root and rhizome tissue samples and associated sediment samples were extracted using a DNeasy PowerSoil kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Root and rhizome samples were thawed from -80°C storage tubes, transferred to sterile petri dishes and cut into equal ~0.5cm segments using a blade sterilized under flame and cleaned with 70% ethanol. Tissue samples were then directly loaded into several PowerBead tubes with 3-5 roots or rhizome segments from each plant. Sediment samples were voided from syringes and separated at a fixed depth of 5cm. Sediment was then homogenized using a Vortex-Genie 2.2 briefly. PowerBead tubes were then loaded with 0.4g of homogenized sediment.

DNA extracts were then sent to Integrated Microbiome Resource (Nova Scotia, Canada) for PCR and sequencing. The Bacteria community was amplified using PCR primers for the 16S rRNA V4 amplicon fragments using high-fidelity Phusion polymerase and fusion primers containing Illumina sequencing adapters and the primer sequences Forward 515FB 5’-GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3’, Reverse 806RB = 5’- GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT-3;(Walters et al. 2015). Amplicon fragments were PCR-amplified from the DNA in duplicate using separate template dilutions (1:1 & 1:10) using the high-fidelity Phusion Plus polymerase. PCR products are verified visually by running on a high-throughput Hamilton Nimbus Select robot using Coastal Genomics Analytical Gels. The PCR reactions from the same samples are pooled in one plate, then cleaned-up and normalized using the high-throughput Charm Biotech Just-a-Plate 96-well Normalization Kit. Libraries were then sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq using 300+300 bp paired-end V3 chemistry (Illumina, Inc).

Sequence Processing

Sequences were analysed using a combination of Quantative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) v 1.9.0 (Caporaso et al., 2010) and USEARCH v11 (Edgar, 2010). Chimeras were identified using USEARCH v11 and were filtered out. Remaining sequences were grouped into zOTUs (zero-radius Operational Taxonomic Units or amplicon sequence variants) using UNOISE3 (Edgar, 2010). Taxonomy was assigned using assign_taxanomy.py QIIME script against Silva 132 16S database (Quast et al., 2012) using USEARCH. Archaeal, mitochondrial, chloroplast-derived sequences were removed from the data using filter_taxa_from_otu_table.py script, leaving only bacterial zOTUs. After filtering, root and sediment samples retained high numbers of bacterial reads and zOTU tables were rarefied at 5000 reads for comparison between these two fractions. Rhizome samples contained fewer reads with high levels of chloroplast and mitochondrial reads. For statistical comparisons of data with rhizomes, a lower rarefaction depth of 1000 was used.

Data Analysis

All the summary data are presented as means ± sample standard deviations. To understand the dominant functional groups present within these bacterial communities we only analysed those taxa found to contribute a greater than 0.5% of the total data set. From the initial list of 204 taxa at the Order and Class level (including unclassified taxa) this left 34 taxa (see Appendix 1). Those taxa were classified into functional groups according to Table 2 to enable further analysis, this followed information contained within the Prokaryote reference collection by Rosenberg et al. (2014), the FAPROTAX database (Louca et al., 2016) and Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology by Garrity et al. (2009). Data analysis and visualization was performed in MiniTab v22 and Primer v7 (Clarke et al., 2014).

Univariate analysis of zOTUs of the functional taxonomic groupings was conducted using permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA+) (Anderson, 2001) using a Euclidean resemblance matrix was employed to analyse the differences in relative abundance between plant age (adult vs juvenile) and structure (roots vs sediment). Community composition was analysed on square-root transformed data using a Bray-Curtis similarity resemblance measure and visualised using non-metric multidimensional scaling ordination (nMDS).

Data Accessibility

Sequence data has been uploaded to the European Nucleotide Archive under Bioproject Accession number: PRJEB81660

Results

A total of 29 samples were successfully sequenced, with 7 samples from Juvenile roots, 6 samples from adult roots and 16 from sediments. The total number of zOTUs in the total dataset was 8089 in a total of 725,762 sequences. After rarefying the data set to 1000 sequences per sample, a total of 5647 zOTUs remained, 200 different taxa with certain taxonomy at the Order and family level were characterised. Thirty-four of these taxa contributed more than 0.5% to the total dataset and were subsequently used in further analysis. The six most abundant of these taxa were Desulfobacterales, Bacteroidales, Chromatiales, Pirellulales, and Clostridiales (see

Figure 2). These six taxa comprised 46% of the total dataset.

Of these abundant taxa only the relative abundance of Clostridiales and Flavobacteriales were significantly effected by plant age whereas all had significantly different relative abundance between the root and the sediment (

Table 1 and

Figure 2). Chromatiales, Clostridiales and Bacteroidales had higher relative abundance on roots , where as Pirelluales had higher relative abundance in the sediment (

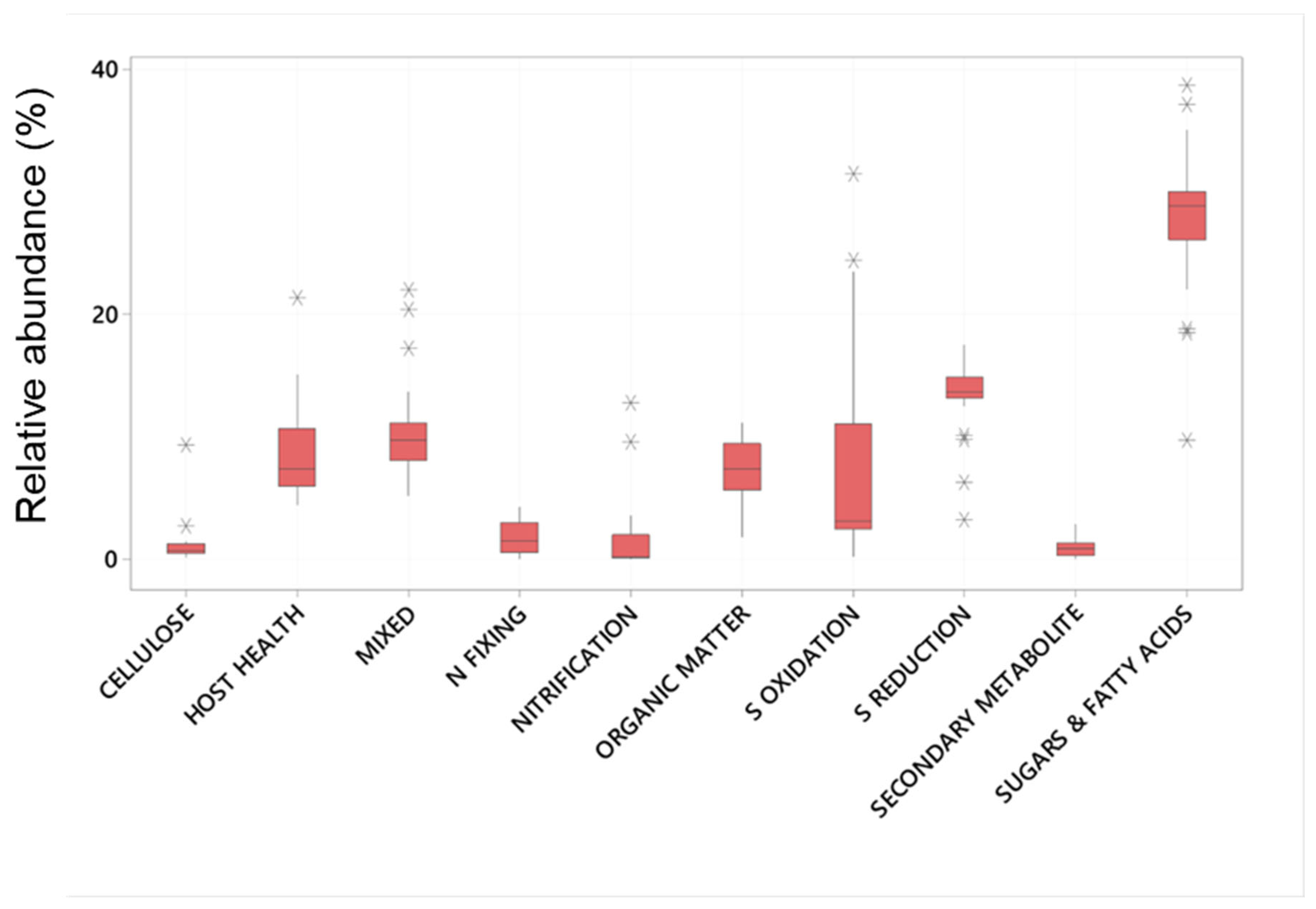

Table 1). In the context of the seagrass microbiome, and based on a review of literature, three of these are organisms known to focus their nutrition on the processing of fatty acids and sugars (Flavobacteriales, Pirellulales, and Clostridiales), whilst two are involved with sulphur cycling (Desulfobacterales generally reduce sulphur and Chromatiales generally oxidise sulphur). Bacteroidales are thought to play roles in nutrient uptake and host fitness. The abundant taxa were classified into ten functional groups (see Appendix 1), and the total relative abundance of each functional group calculated for each sample. This finds that taxa involved with the breakdown of complex sugars and fatty acids are the most abundant (27.7±5.7%) followed by Sulphur Reducing Bacteria (13.4±3.0 %) and Sulphur Oxidising Bacteria (8.6± 12) (

Figure 3).

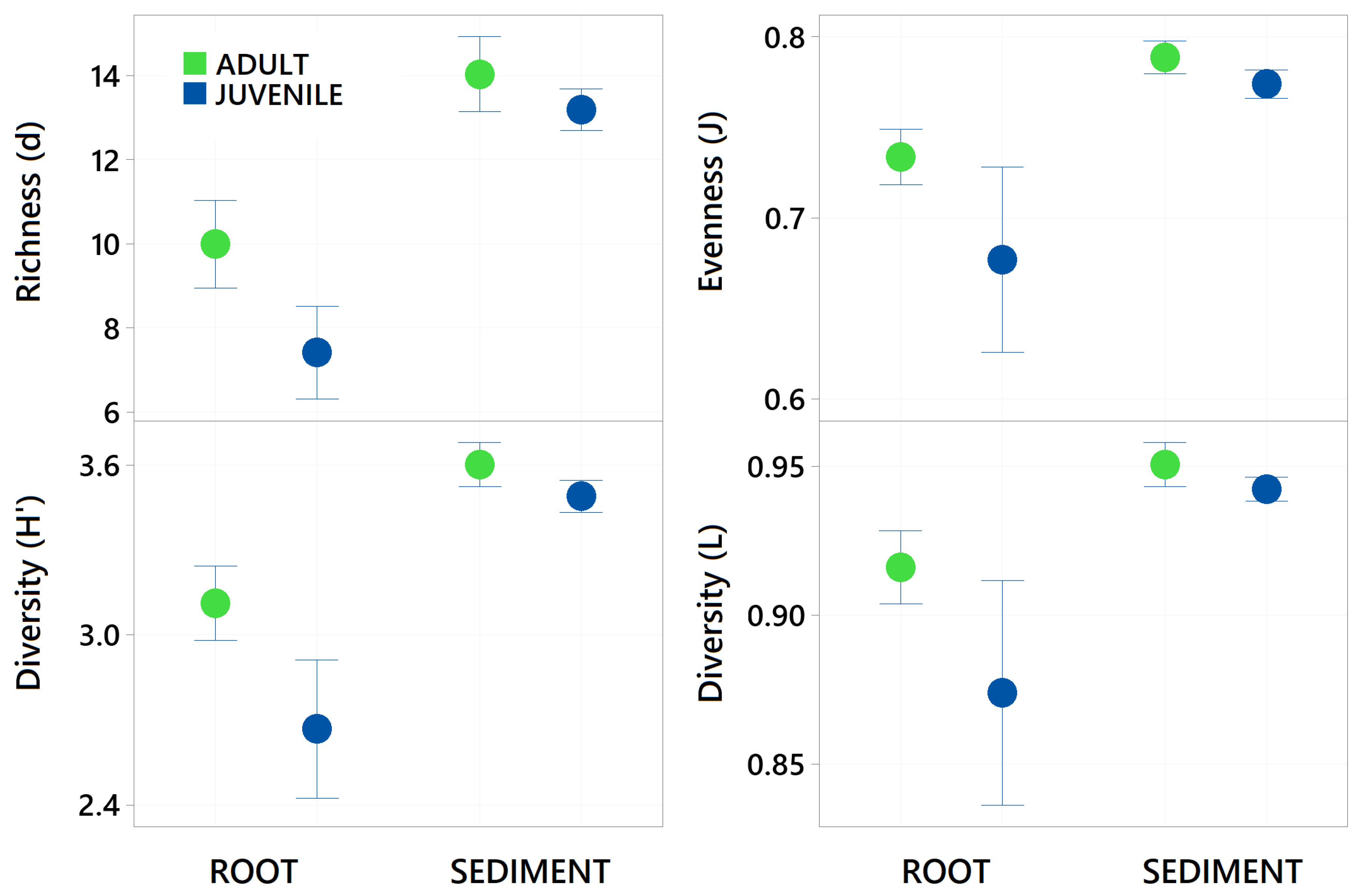

Sediment samples were found to have significantly higher zOTU richness (margalefs) (

p=<0.001), Evenness (Pielou’s) (

p=<0.001), Shannon (

p=<0.001) and Simpsons diversity (

p=<0.001) than root samples (

Table 1 and

Figure 4). There were some significant interactions though as evenness in the juvenile root samples was high variable and limited difference between adult and juvenile sediment for simpsons diversity and richness. There was also a significant effect of age, with juvenile plants for all these diversity metrics having a lower value than adult plants (

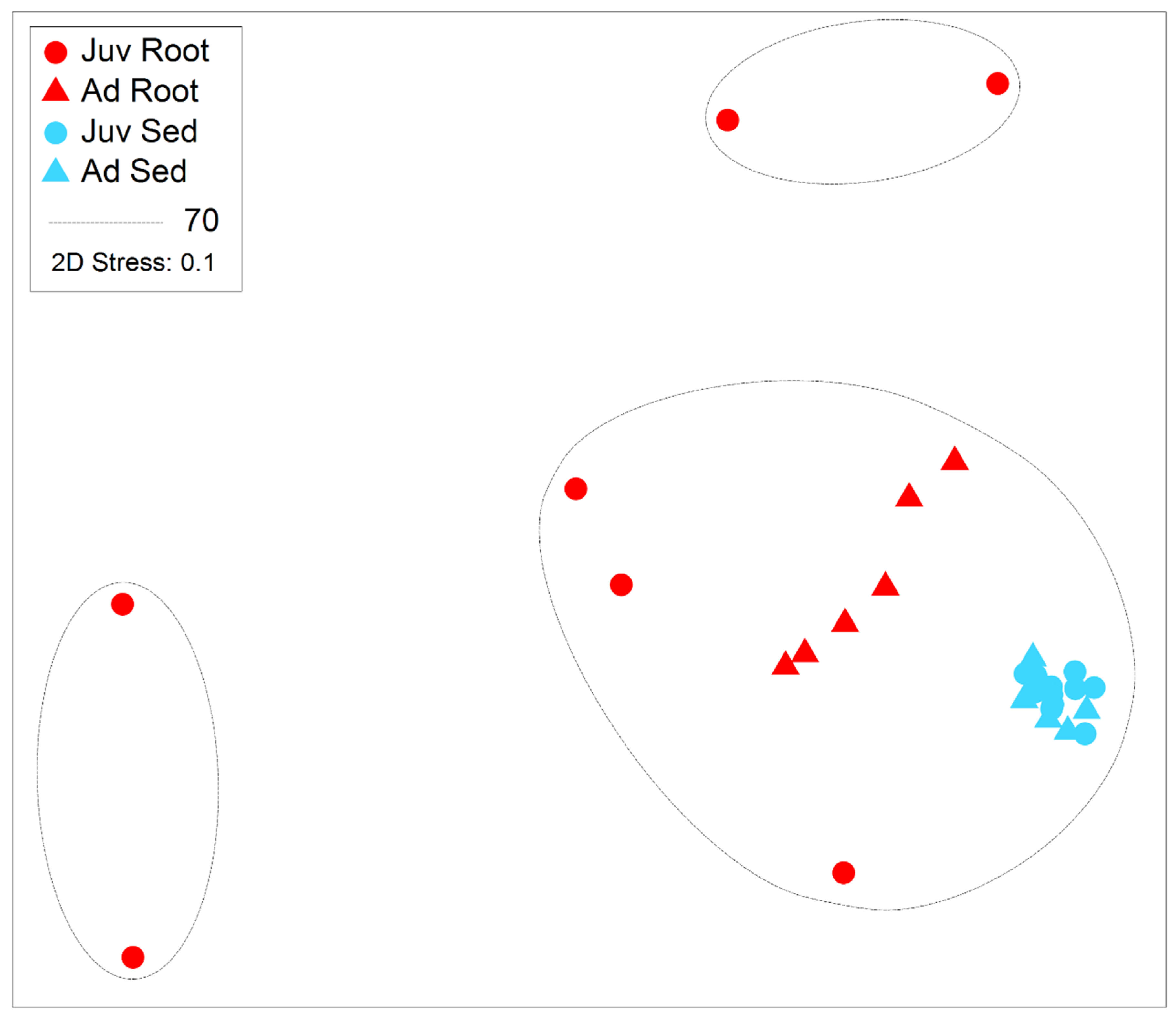

p=<0.001). The community assemblage of the bacterial communities was also significantly affected by age and structure (see

Table 1). The nMDS show how the sediment samples are all tightly clustered into one similar community irrespective of age (

Figure 5), but the root samples are highly variable relative to the sediment samples and with respect to their age. Imposing 70% similarity clusters onto the associated nMDS show that these differences are most likely influenced by a range of outliers as some of the juvenile root samples are in separate 70% similarity clusters.

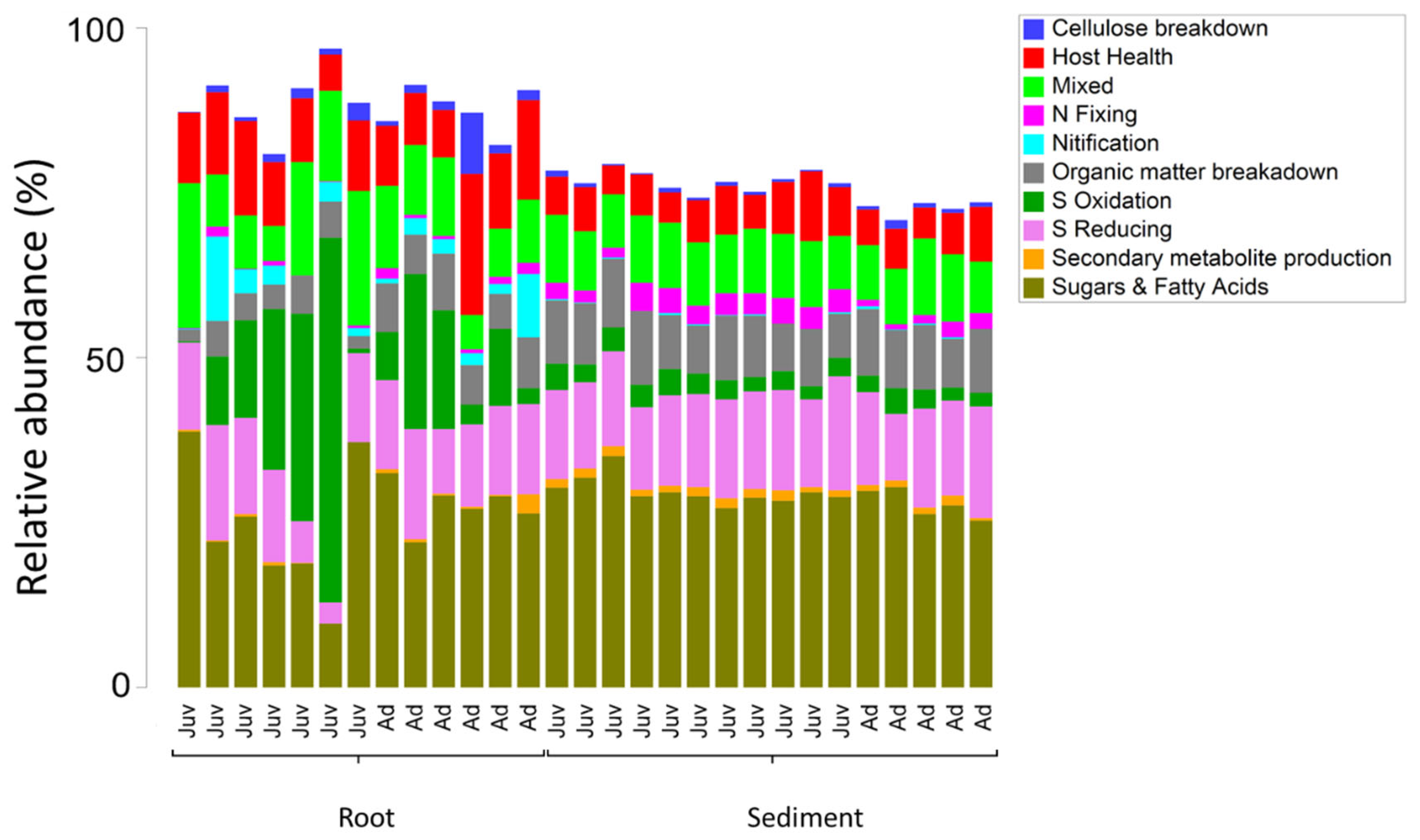

Within root communities some key functional groups were significantly more abundant than in sediment environments, specifically the nitrifiers, and those involved with host health, sulphur oxidation and cellulose breakdown. This was also the case with those bacteria involved with the breakdown of sugars and amino acids (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Nitrogen fixers, those involved with organic matter breakdown and those that produce secondary metabolites all had significantly higher relative abundance in the sediment environments relative to the roots (

Table 1 and

Figure 6). Sulphur reducing bacteria and microbes with mixed functional did not significantly differ with respect to root vs sediment environments (

Table 1) in abundance from root to sediment environments.

Age of the plant did not significantly affect the relative abundance of many of the functional groups. Nitrogen fixing bacteria were significantly more abundant in juvenile plants whilst those involved with cellulose breakdown were significantly more abundant in adult plants. This significant increase in nitrogen fixing bacteria interacted with respect to the root vs sediment environments (See

Figure 6). There was also a significant effect of age on the zOTUs of those taxa involved with the breakdown of organic matter.

Figure 6.

Relative abundance of each of the ten assigned functional microbial groupings to zOTUs within 16S rRNA gene libraries generated from roots and adjacent sediments of juvenile (seedlings) and adult plants of the seagrass Zostera marina planted in Dale in the Milford Haven Waterway in West Wales. Significant differences between root and sediment are shown by letters (A &B) whereas significant differences between age classes are shown with a *.

Figure 6.

Relative abundance of each of the ten assigned functional microbial groupings to zOTUs within 16S rRNA gene libraries generated from roots and adjacent sediments of juvenile (seedlings) and adult plants of the seagrass Zostera marina planted in Dale in the Milford Haven Waterway in West Wales. Significant differences between root and sediment are shown by letters (A &B) whereas significant differences between age classes are shown with a *.

Figure 7.

Relative abundance of dominant functional groups of Bacteria in 16S rRNA gene libraries generated from twenty-nine samples collected on the roots and adjacent sediments of juvenile (seedlings) and adult plants of the seagrass Zostera marina planted in Dale in the Milford Haven Waterway in West Wales.

Figure 7.

Relative abundance of dominant functional groups of Bacteria in 16S rRNA gene libraries generated from twenty-nine samples collected on the roots and adjacent sediments of juvenile (seedlings) and adult plants of the seagrass Zostera marina planted in Dale in the Milford Haven Waterway in West Wales.

Discussion

Seagrass meadows have significant functional roles in biogeochemical cycling, particularly in the context of nitrogen and sulphur cycling, as well as in the accumulation and breakdown of carbon (Holmer, 2019). The microbiome associated with seagrass plays a significant part in these processes but remains poorly understood (Ugarelli et al., 2017;Tarquinio et al., 2019) Tarquino et al. 2019). In the present study, we provide a novel functional breakdown of the microbial communities associated with the seagrass rhizosphere and endosphere relative to changes in plant development. Whilst differences with respect to plant development are limited to a higher relative abundance of N Fixing Bacteria, in seedlings and a lower abundance of those involved with organic matter breakdown, there exist large differences in the diversity of the taxa present within the microbiome of seedlings in comparison to mature plants. We also record the relative abundance and composition of microbes to be far more variable within young plants relative to adult ones. In line with previous literature, greater microbial diversity in the present study is observed from sediment samples (relative to roots) (Fraser et al., 2018;Jansson and Hofmockel, 2018), highlighting how different niche environments likely exist within these regions near to seagrass roots (Brodersen et al., 2024).

Although the juvenile plants (seedlings) observed here were only a few months old, their microbial communities of key functional taxa (e.g Chromatiales generally oxidise sulphur) was no different to that of adult plants but much more abundant than within the surrounding sediment. We hypothesise that these assemblages develop rapidly on the roots to aid with their capacity to deal with the harsh anoxic sulphide environment whilst enabling them to overcome insufficient resource availability ammonium (Vieira et al., 2022).

Seagrass root systems are typically found anchoring in sediments with anoxic and sulphuric conditions (Hemminga and Duarte, 2000); this environment of harsh redox gradients necessitates that seagrasses manipulate their root environment via exudation (Martin et al., 2019) and radial oxygen loss (ROL) (Jensen et al., 2007), imposing selection pressures on microbial communities within surrounding sediments (Ettinger et al., 2017).

The abundance of Sulfate Reducing Bacteria observed in the present study within the roots and sediments of seedlings and mature plants highlights the harsh environment for seagrass plants to develop and survive, as the SRB potentially produce an abundance of toxic H2S. Seawater contains an abundance of sulphur, leading to the tendency for anoxic conditions to drive the production of hydrogen sulphide aided by an abundance of Sulphide Reducing Bacteria. The ROL from seagrass roots has been shown to drive the balance of microbes within the rhizosphere, leading to lower Hydrogen Sulphide concentrations and, therefore, lower relative abundance of sulphide-reducing bacteria. Within individual young seedlings, the relative production of ROL is likely lower than that of mature plants, essentially due to lower photosynthetic production (Martin et al., 2019;Brodersen and Kühl, 2023). It is for this reason that we hypothesise that the rapid accumulation of species of Chromatiales is essential for juvenile plants to survive.

This abundance highlights the harsh environment to which a young seedling must endure to develop into a mature plant. This abundance of SRB in the seedling roots might also have other benefits as many SRBs are capable of di-nitrogen (N2) fixation, creating ammonium. The toxicity of the H2S may therefore be offset by the production of a stable supply of nutrients. This aligns with the presence of an increased relative abundance of targeted N2 fixing organisms (Rhizobiales) on the roots of young plants relative to mature ones.

The presence of ammonium in the rhizosphere from fixation not only creates a source of nitrogen for the plants, but also creates a substrate for an abundance of nitrifying bacteria (Nitrosococcales) which is also then potentially broken down into N2O via denitrification from species of Gammaproteobacteria and Rhodobacterales (that have mixed functional roles but have abundant taxa that are involved with denitrification). An abundance of denitrifying bacteria within these root and sediment environments creates potential for nitrous oxide production to be significant. Seagrasses within the experimental site are enriched with excess nitrogen as a result of highly elevated nitrate concentrations (Jones and Unsworth, 2016) and values well above 1mg/L have been observed at the experimental sites (NRW, 2024). Although data on nitrous oxide emissions from seagrass is weak, knowledge from mangroves and other systems indicates that elevated nitrate concentrations lead to such emissions.

In contrast to the high potential for the production of nitrous oxides from these seagrass meadows, we also find limited evidence of an abundance of microorganisms likely to produce methane (although a targeted analysis has not been conducted), another possible greenhouse gas emission from seagrass (Schorn et al., 2022).

The microbial assemblages around the roots and sediments were dominated throughout by taxa commonly thought to be involved with the breakdown of complex sugars and amino acids, the most abundant of these being the Flavobacteriales, Pirellulales and Clostridiales. This is not surprising given the high levels of sucrose sugars commonly observed in seagrass-associated sediments as a result of root exudation into the rhizosphere (Sogin et al., 2022). The relative abundance of this functional group didn’t alter significantly with respect to the plant’s age or between root and sediment (however abundance was more variable within juvenile roots), suggesting that the whole wider rhizosphere and endosphere region around the plant is awash with these sugars. Heterotrophic microbial degradation of sugars and amino acids is likely to lead to an increased pull down of Oxygen, although not shown to be differing between plant ages, such reduction in oxygen may have a consequential role of causing the reduction of elemental sulphur to hydrogen sulphide, exacerbating the toxicity of what is already a harsh sedimentary environment.

We observed a far more variable microbial assemblage in terms of taxa abundance and competition in the juvenile seagrass relative to adult systems. This may simply be because older, more mature meadows establish a more integrated and active microbiome over time, as seen in their terrestrial counterparts (Wagner et al., 2016). The higher numbers of observed bacterial OTUs isolated in adult samples may suggest an increased metabolic requirement of established seagrass meadows, as the formation of more complex micronutrients is known to progress with plant age (Bressan et al., 2009). Adult plants also had higher relative abundance of microbes involved with breakdown of cellulose, likely the result of the established turnover of plant material within a mature meadow rather than individual seedlings.

The microbiome associated to the roots of both juvenile and adult plants is consistently different to the assemblage present in the sediment rhizosphere, highlighting the niche separation between these environments, but also the likely presence of a holobiont community. Nitrifying bacteria, microbes involved with host health and sulphur oxidizing bacteria all had relative abundance elevated at the roots relative to those in the sediment. This classification we use here approximates the functions of these organisms that is an oversimplification of the abundant species present within each taxonomic grouping. To fully understand these groupings and the exact roles being undertaken (e.g. in terms of host health) requires a far deeper look at the individual grouping as well as more of a metagenomics, metatranscriptomics or metabolomics pipeline approach for the mechanistic interrogation of the microbiome (Han et al., 2021).

In summary, this study highlights the dynamic relationship between seagrass (Zostera marina) and its microbiome, revealing significant differences in microbial communities and functions across plant developmental stages.

Juvenile seagrass roots showed higher abundances of nitrogen-fixing bacteria, aiding in nutrient availability and reducing anoxic stress. In contrast, mature plants exhibited more stable and diverse microbial communities. Sediment samples consistently had higher microbial diversity than root samples, indicating distinct niche environments within seagrass meadows. These findings highlight the crucial role of the seagrass holobiont in nitrogen and sulphur cycling, with implications for seagrass restoration and blue carbon strategies. Although the present study tease out the exact microbial species present on juvenile seagrass plants it highlights that these communities are very different in composition to those on established adult plants, whether this is an adaptive response to life as seedling in a harsh environment or a desperate attempt to play microbial ‘catch’up’ to develop an effective microbiome remains to be seen. What we do know is that the re-establishment of seagrass populations through various types of restoration activity is riddled with failures and that processes of scale help plants overcome feedbacks in the system. Better understanding of the specific functions of microbial taxa and the seagrass holobiont in overcoming these feedbacks might facilitate employing advanced techniques to improve seagrass ecosystem conservation and restoration.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Functional classification of taxa applied to analysis of seagrass and sediment microbial data obtained from samples collected in Milford haven, Pembrokeshire, Wales.

Table A1.

Functional classification of taxa applied to analysis of seagrass and sediment microbial data obtained from samples collected in Milford haven, Pembrokeshire, Wales.

| Desulfobacterales |

S Reducing |

| Flavobacteriales |

Sugars & Fatty Acids |

| Bacteroidales |

Host Health |

| Chromatiales |

S Oxidation |

| Pirellulales |

Sugars & Fatty Acids |

| Clostridiales |

Sugars & Fatty Acids |

| Chitinophagales |

Organic matter breakadown |

| Gammaproteobacteria |

Mixed |

| Cytophagales |

Organic matter breakadown |

| Campylobacterales |

Mixed |

| Spirochaetales |

Sugars & Fatty Acids |

| Gammaproteobacteria Incertae Sedis |

Mixed |

| Rhizobiales |

N Fixing |

| Cellvibrionales |

Mixed |

| Steroidobacterales |

Sugars & Fatty Acids |

| Nitrosococcales |

Nitification |

| B2M28 |

Unclear |

| Rhodobacterales |

Mixed |

| Thiomicrospirales |

S Oxidation |

| Thermoanaerobaculales |

Sugars & Fatty Acids |

| Ectothiorhodospirales |

S Reducing |

| Thiotrichales |

S Oxidation |

| Myxobacteria |

Secondary metabolite production |

| MSBL9 |

Sugars & Fatty Acids |

| Alteromonadales |

Organic matter breakadown |

| Oceanospirillales |

Organic matter breakadown |

| Sphingobacteriales |

Sugars & Fatty Acids |

| Microtrichales |

Organic matter breakadown |

| Ignavibacteriales |

Cellulose breakdown |

| Moduliflexales |

Sugars & Fatty Acids |

| Betaproteobacteriales |

Mixed |

| Desulfuromonadales |

S Reducing |

| Kiritimatiellales |

Sugars & Fatty Acids |

| Fibrobacterales |

Cellulose breakdown |

References

- Anderson, M.J. (2001). A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecology 26, 32-46.

- Blackall, L.L., Dungan, A.M., Hartman, L.M., and Van Oppen, M.J. (2020). Probiotics for corals. Microbiology Australia 41, 100-104.

- Bressan, M., Roncato, M.-A., Bellvert, F., Comte, G., Haichar, F.E.Z., Achouak, W., and Berge, O. (2009). Exogenous glucosinolate produced by Arabidopsis thaliana has an impact on microbes in the rhizosphere and plant roots. The ISME Journal 3, 1243-1257. [CrossRef]

- Brodersen, K.E., and Kühl, M. (2023). Photosynthetic capacity in seagrass seeds and early-stage seedlings of Zostera marina. New Phytologist 239, 1300-1314. [CrossRef]

- Brodersen, K.E., Mosshammer, M., Bittner, M.J., Hallstrøm, S., Santner, J., Riemann, L., and Kühl, M. (2024). Seagrass-mediated rhizosphere redox gradients are linked with ammonium accumulation driven by diazotrophs. Microbiology Spectrum 12, e03335-03323. [CrossRef]

- Burkholder, J.M., Tomasko, D.A., and Touchette, B.W. (2007). Seagrasses and eutrophication. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 350, 46-72.

- Caporaso, J.G., Kuczynski, J., Stombaugh, J., Bittinger, K., Bushman, F.D., Costello, E.K., Fierer, N., Peña, A.G., Goodrich, J.K., Gordon, J.I., Huttley, G.A., Kelley, S.T., Knights, D., Koenig, J.E., Ley, R.E., Lozupone, C.A., Mcdonald, D., Muegge, B.D., Pirrung, M., Reeder, J., Sevinsky, J.R., Turnbaugh, P.J., Walters, W.A., Widmann, J., Yatsunenko, T., Zaneveld, J., and Knight, R. (2010). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature Methods 7, 335-336.

- Carey, D.A., Hayn, M., Germano, J.D., Little, D.I., and Bullimore, B. (2015). Marine habitat mapping of the Milford Haven Waterway, Wales, UK: Comparison of facies mapping and EUNIS classification for monitoring sediment habitats in an industrialized estuary. Journal of Sea Research 100, 99-119. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R., Gorley, R.N., Somerfield, P.J., and Warwick, R.M. (2014). Change in marine communities: an approach to statistical analysis and interpretation. 3rd edition. PRIMER-E, Plymouth, 260pp.

- Cúcio, C., Overmars, L., Engelen, A.H., and Muyzer, G. (2018). Metagenomic Analysis Shows the Presence of Bacteria Related to Free-Living Forms of Sulfur-Oxidizing Chemolithoautotrophic Symbionts in the Rhizosphere of the Seagrass Zostera marina. Frontiers in Marine Science 5. [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460-2461. [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, C.L., Voerman, S.E., Lang, J.M., Stachowicz, J.J., and Eisen, J.A. (2017). Microbial communities in sediment from Zostera marina patches, but not the Z. marina leaf or root microbiomes, vary in relation to distance from patch edge. PeerJ 5, e3246.

- Fitzpatrick, C.R., Copeland, J., Wang, P.W., Guttman, D.S., Kotanen, P.M., and Johnson, M.T.J. (2018). Assembly and ecological function of the root microbiome across angiosperm plant species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, E1157-E1165. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, M.W., Gleeson, D.B., Grierson, P.F., Laverock, B., and Kendrick, G.A. (2018). Metagenomic Evidence of Microbial Community Responsiveness to Phosphorus and Salinity Gradients in Seagrass Sediments. Frontiers in Microbiology 9. [CrossRef]

- Garrity, G.M., Staley, J.T., Boone, D.R., Brenner, D.J., Devos, P., Goodfellow, M., Krieg, N.R., Rainey, F.A., and Schlefer, K. (2009). Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Springer.

- Graham, O.J., Adamczyk, E.M., Schenk, S., Dawkins, P., Burke, S., Chei, E., Cisz, K., Dayal, S., Elstner, J., Hausner, A.L.P., Hughes, T., Manglani, O., Mcdonald, M., Mikles, C., Poslednik, A., Vinton, A., Wegener Parfrey, L., and Harvell, C.D. (2024). Manipulation of the seagrass-associated microbiome reduces disease severity. Environmental Microbiology 26, e16582. [CrossRef]

- Han, S., Van Treuren, W., Fischer, C.R., Merrill, B.D., Defelice, B.C., Sanchez, J.M., Higginbottom, S.K., Guthrie, L., Fall, L.A., Dodd, D., Fischbach, M.A., and Sonnenburg, J.L. (2021). A metabolomics pipeline for the mechanistic interrogation of the gut microbiome. Nature 595, 415-420. [CrossRef]

- Hemminga, M.A., and Duarte, C.M. (2000). Seagrass Ecology. Cambridge University Press.

- Herbert, R.A. (1999). Nitrogen cycling in coastal marine ecosystems. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 23, 563-590.

- Holmer, M. (2019). "Chapter 13 - Productivity and Biogeochemical Cycling in Seagrass Ecosystems," in Coastal Wetlands (Second Edition), eds. G.M.E. Perillo, E. Wolanski, D.R. Cahoon & C.S. Hopkinson. Elsevier), 443-477.

- Jansson, J.K., and Hofmockel, K.S. (2018). The soil microbiome—from metagenomics to metaphenomics. Current Opinion in Microbiology 43, 162-168.

- Jensen, S.I., Kühl, M., and Priemé, A. (2007). Different bacterial communities associated with the roots and bulk sediment of the seagrass Zostera marina. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 62, 108-117. [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.L., and Unsworth, R.K.F. (2016). The perilous state of seagrass in the British Isles. Royal Society Open Science 3. [CrossRef]

- Kardish, M.R., and Stachowicz, J.J. (2023). Local environment drives rapid shifts in composition and phylogenetic clustering of seagrass microbiomes. Scientific Reports 13, 3673. [CrossRef]

- Kay, Q.O.N. (1998). "A review of the existing state of knowledge of the ecology and distribution of seagrass beds around the coast of Wales". Countryside Council for Wales, Science Report 296, Bangor, Wales.).

- Louca, S., Parfrey, L.W., and Doebeli, M. (2016). Decoupling function and taxonomy in the global ocean microbiome. Science 353, 1272-1277. [CrossRef]

- Macreadie, P.I., Atwood, T.B., Seymour, J.R., Fontes, M.L.S., Sanderman, J., Nielsen, D.A., and Connolly, R.M. (2019). Vulnerability of seagrass blue carbon to microbial attack following exposure to warming and oxygen. Science of The Total Environment 686, 264-275. [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.C., Bougoure, J., Ryan, M.H., Bennett, W.W., Colmer, T.D., Joyce, N.K., Olsen, Y.S., and Kendrick, G.A. (2019). Oxygen loss from seagrass roots coincides with colonisation of sulphide-oxidising cable bacteria and reduces sulphide stress. The ISME Journal 13, 707-719. [CrossRef]

- Maúre, E.D.R., Terauchi, G., Ishizaka, J., Clinton, N., and Dewitt, M. (2021). Globally consistent assessment of coastal eutrophication. Nature Communications 12, 6142. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.B. (2018). The seed microbiome: Origins, interactions, and impacts. Plant and Soil 422, 7-34. [CrossRef]

- Nrw (2024). Access our data, maps and reports [Online]. Available: https://naturalresources.wales/evidence-and-data/accessing-our-data/access-our-data-maps-and-reports/?lang=en [Accessed].

- Quast, C., Pruesse, E., Yilmaz, P., Gerken, J., Schweer, T., Yarza, P., Peplies, J., and Glöckner, F.O. (2012). The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Research 41, D590-D596.

- Rosenberg, E., Delong, F.E., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E., and Thompson, F. (2014). The Prokartyotes. Springer.

- Schorn, S., Ahmerkamp, S., Bullock, E., Weber, M., Lott, C., Liebeke, M., Lavik, G., Kuypers, M.M.M., Graf, J.S., and Milucka, J. (2022). Diverse methylotrophic methanogenic archaea cause high methane emissions from seagrass meadows. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119, e2106628119. [CrossRef]

- Shade, A., Jacques, M.-A., and Barret, M. (2017). Ecological patterns of seed microbiome diversity, transmission, and assembly. Current Opinion in Microbiology 37, 15-22. [CrossRef]

- Sogin, E.M., Michellod, D., Gruber-Vodicka, H.R., Bourceau, P., Geier, B., Meier, D.V., Seidel, M., Ahmerkamp, S., Schorn, S., D’angelo, G., Procaccini, G., Dubilier, N., and Liebeke, M. (2022). Sugars dominate the seagrass rhizosphere. Nature Ecology & Evolution 6, 866-877. [CrossRef]

- Tarquinio, F., Hyndes, G.A., Laverock, B., Koenders, A., and Säwström, C. (2019). The seagrass holobiont: understanding seagrass-bacteria interactions and their role in seagrass ecosystem functioning. FEMS Microbiology Letters 366. [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, C., Høj, L., and Bourne, D.G. (2022). Probiotics for coral aquaculture: challenges and considerations. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 73, 380-386. [CrossRef]

- Turner, T.R., James, E.K., and Poole, P.S. (2013). The plant microbiome. Genome Biology 14, 209.

- Ugarelli, K., Chakrabarti, S., Laas, P., and Stingl, U. (2017). The Seagrass Holobiont and Its Microbiome. Microorganisms 5, 81. [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, R.K.F., Bertelli, C.M., Coals, L., Cullen-Unsworth, L.C., Den Haan, S., Jones, B.L.H., Rees, S.R., Thomsen, E., Wookey, A., and Walter, B. (2023). Bottlenecks to seed-based seagrass restoration reveal opportunities for improvement. Global Ecology and Conservation 48, e02736. [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, R.K.F., Bertelli, C.M., Cullen-Unsworth, L.C., Esteban, N., Jones, B.L., Lilley, R., Lowe, C., Nuuttila, H.K., and Rees, S.C. (2019). Sowing the Seeds of Seagrass Recovery Using Hessian Bags. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 7. [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, R.K.F., Rees, S.C., Bertelli, C.M., Esteban, N.E., Furness, E.J., and Walter, B. (2022). Nutrient additions to seagrass seed planting improve seedling emergence and growth. Frontiers in Plant Science 13. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, V.M.N.C.S., Lobo-Arteaga, J., Santos, R., Leitão-Silva, D., Veronez, A., Neves, J.M., Nogueira, M., Creed, J.C., Bertelli, C.M., Samper-Villarreal, J., and Pettersen, M.R.S. (2022). Seagrasses benefit from mild anthropogenic nutrient additions. Frontiers in Marine Science 9. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.R., Lundberg, D.S., Del Rio, T.G., Tringe, S.G., Dangl, J.L., and Mitchell-Olds, T. (2016). Host genotype and age shape the leaf and root microbiomes of a wild perennial plant. Nature Communications 7, 12151. [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, L.G.E., Leray, M., O’dea, A., Yuen, B., Peixoto, R.S., Pereira, T.J., Bik, H.M., Coil, D.A., Duffy, J.E., Herre, E.A., Lessios, H.A., Lucey, N.M., Mejia, L.C., Rasher, D.B., Sharp, K.H., Sogin, E.M., Thacker, R.W., Vega Thurber, R., Wcislo, W.T., Wilbanks, E.G., and Eisen, J.A. (2019). Host-associated microbiomes drive structure and function of marine ecosystems. PLOS Biology 17, e3000533. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).