Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

28 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

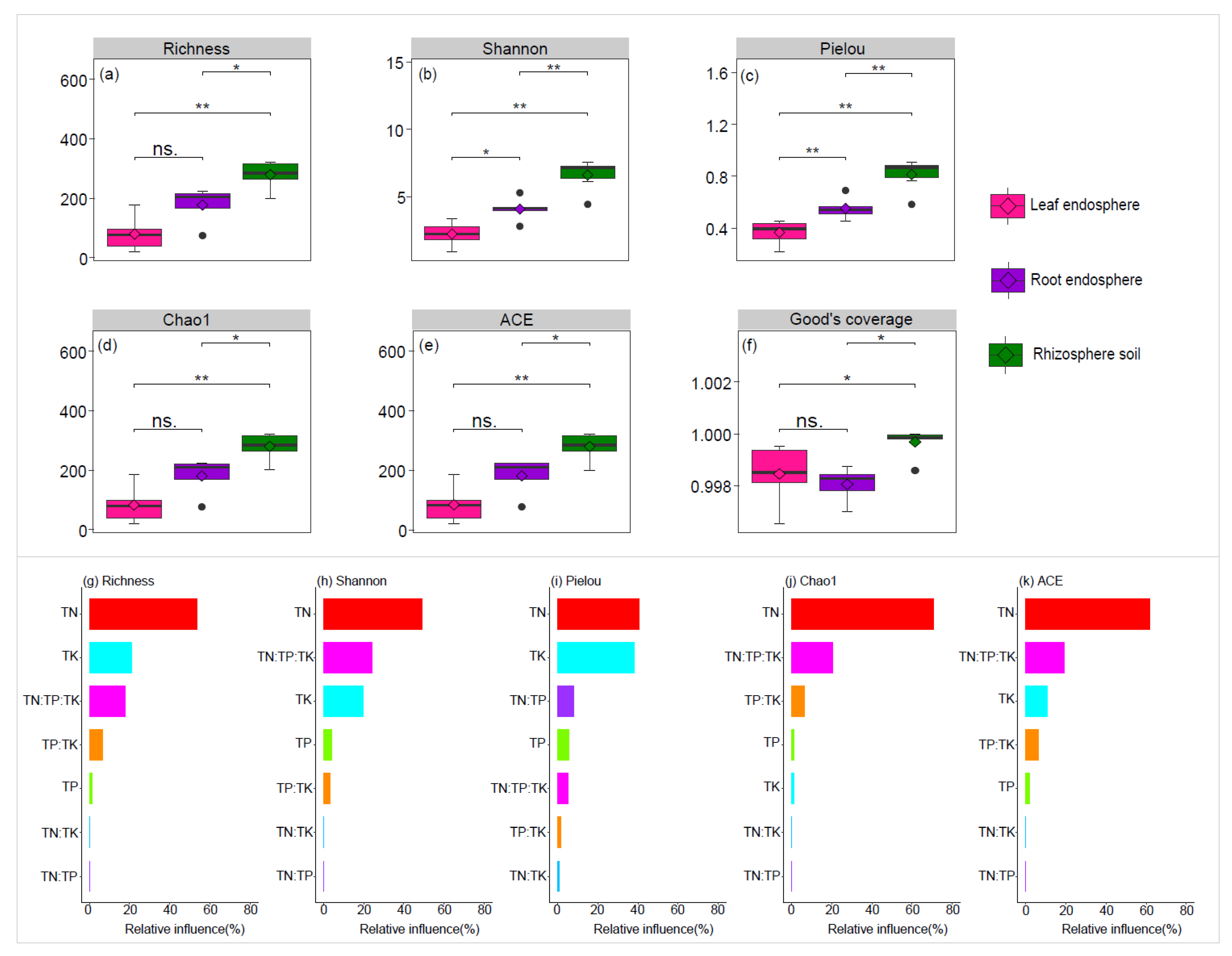

2.1. Bacterial Community Diversity Across Different Plant Compartment Niches

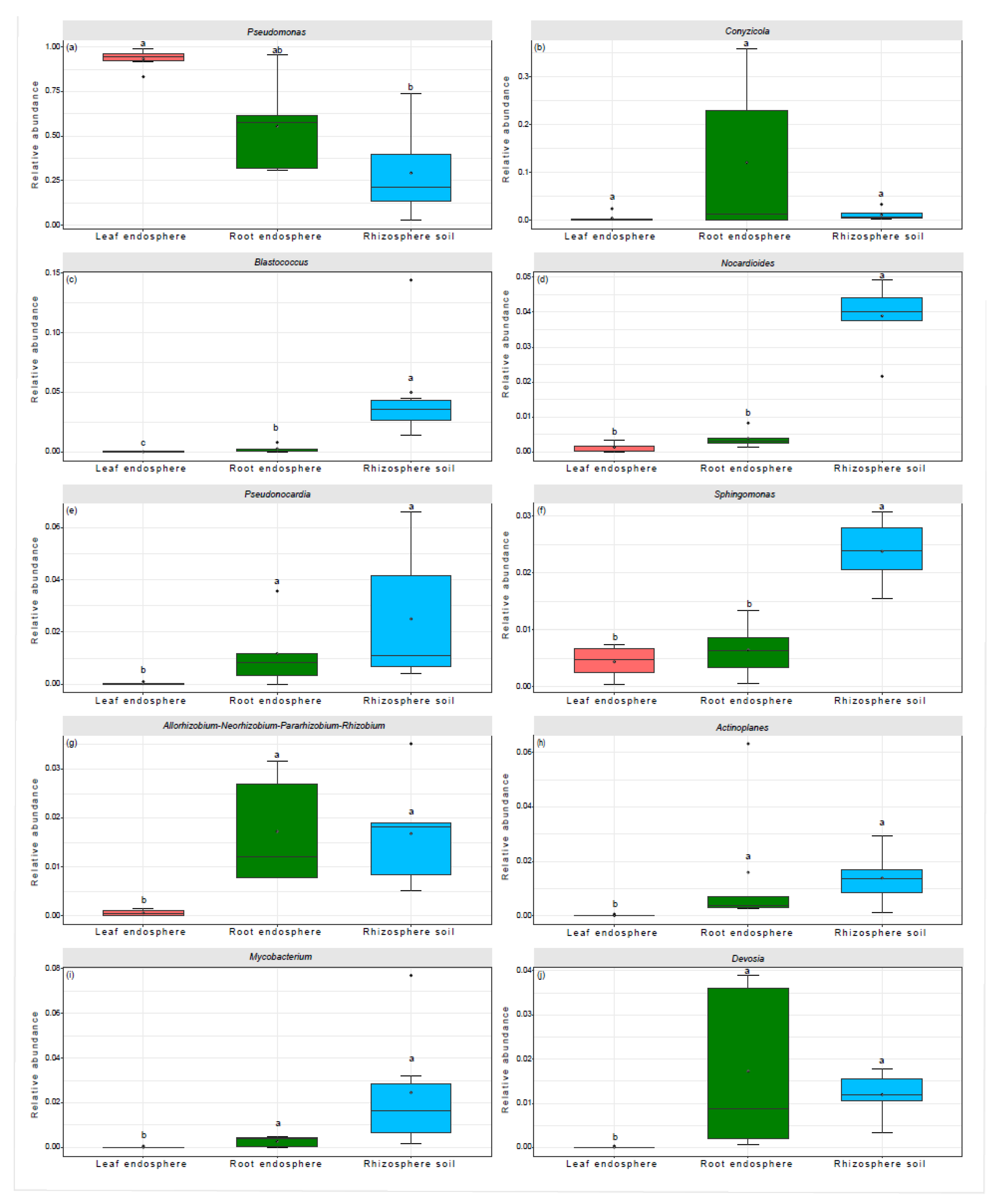

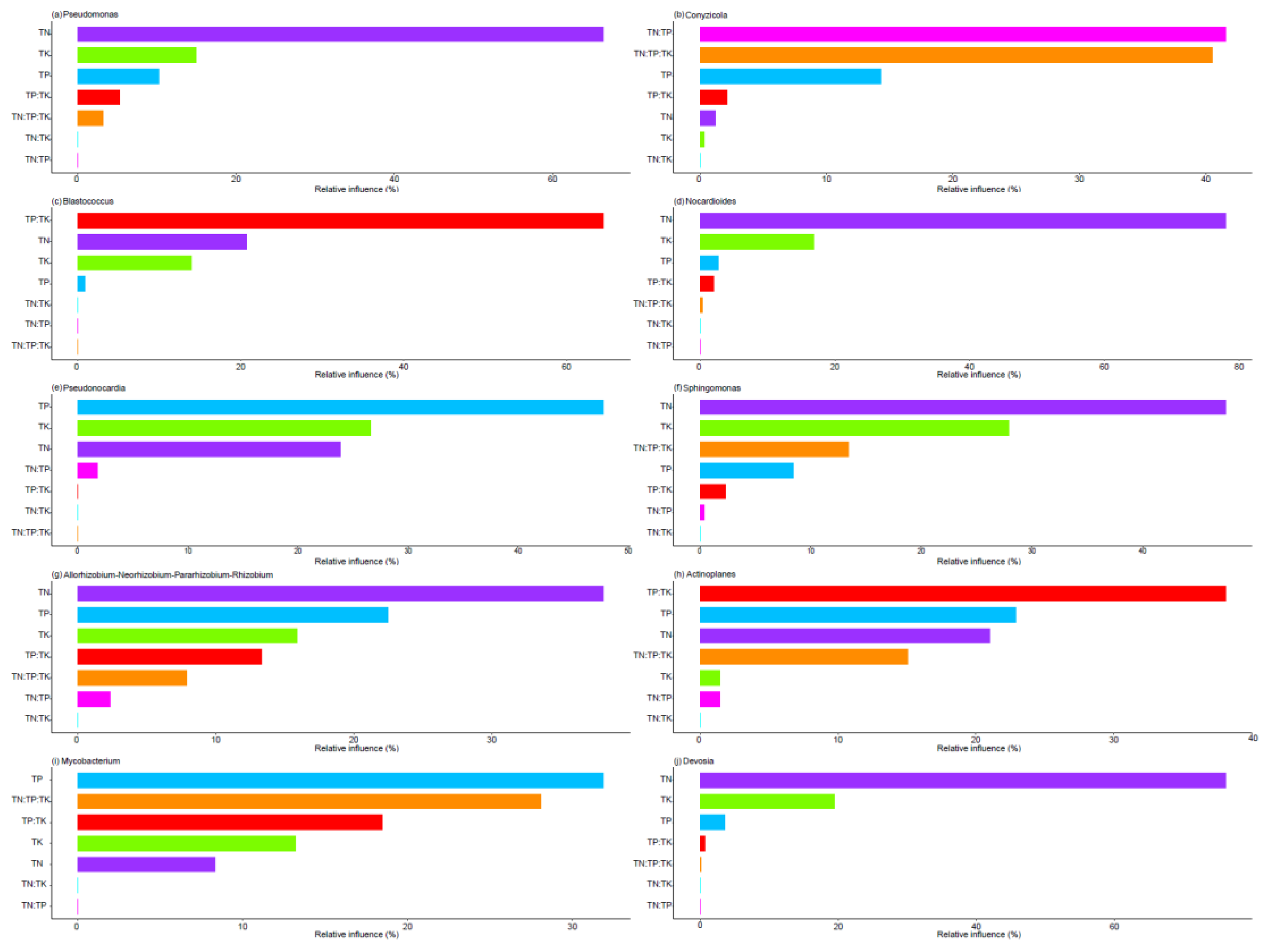

2.2. Bacterial Community Composition Across Different Plant Compartment Niches

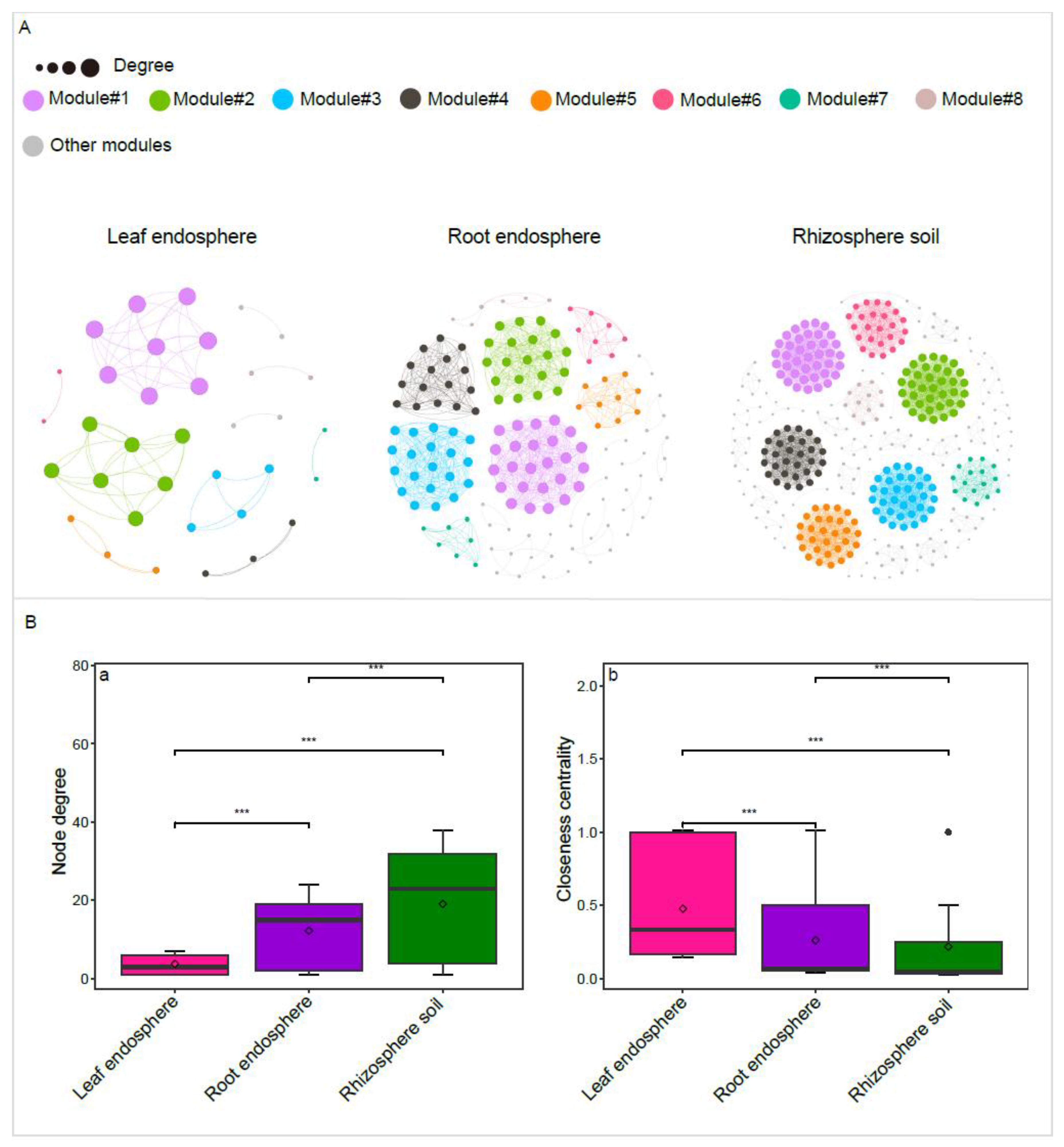

2.3. Bacterial Community Co-Occurrence Networks Across Different Plant Compartment Niches

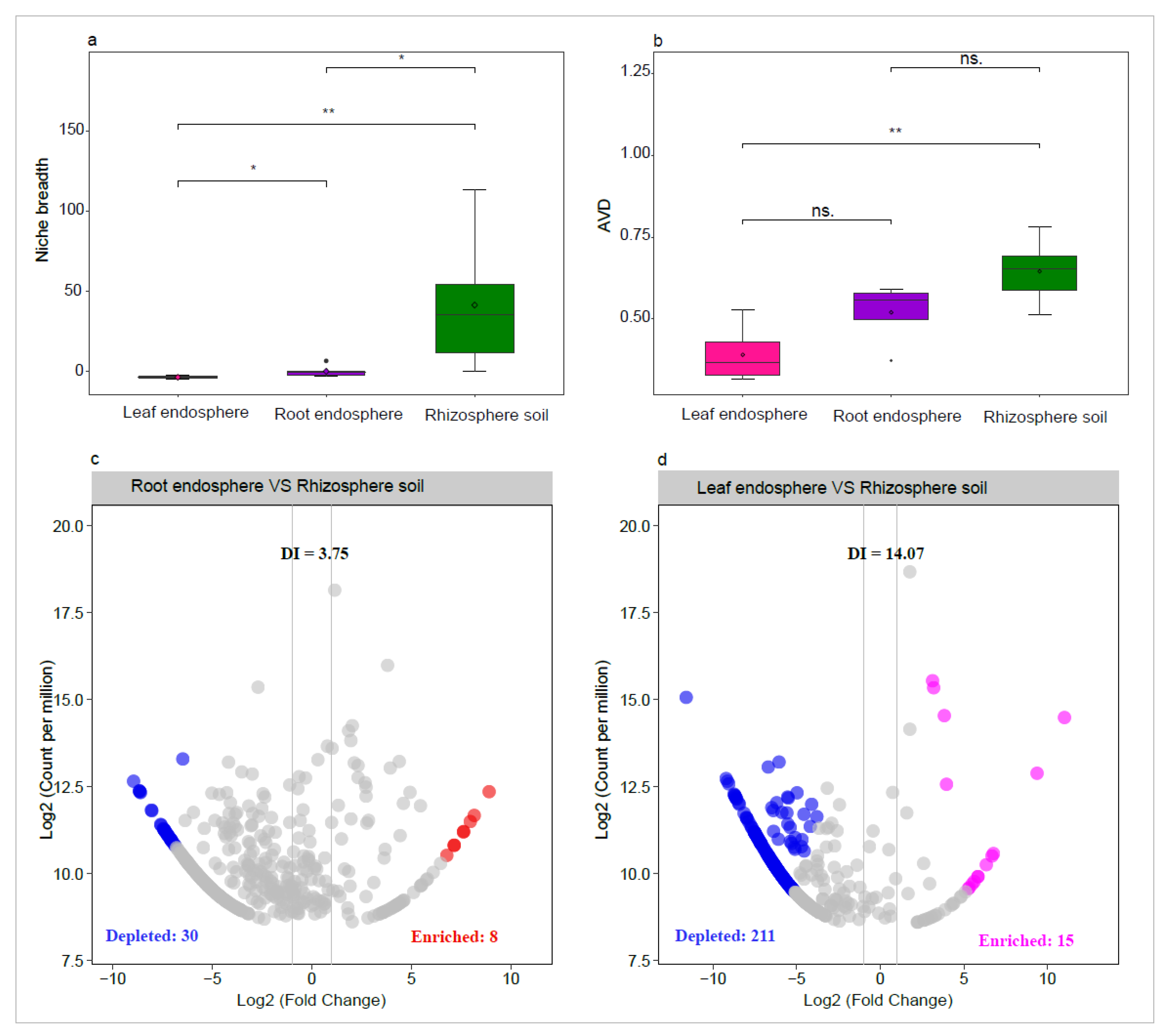

2.4. Bacterial Community Niche Breadth, Stability and Host Selection Processes Across Different Plant Compartment Niches

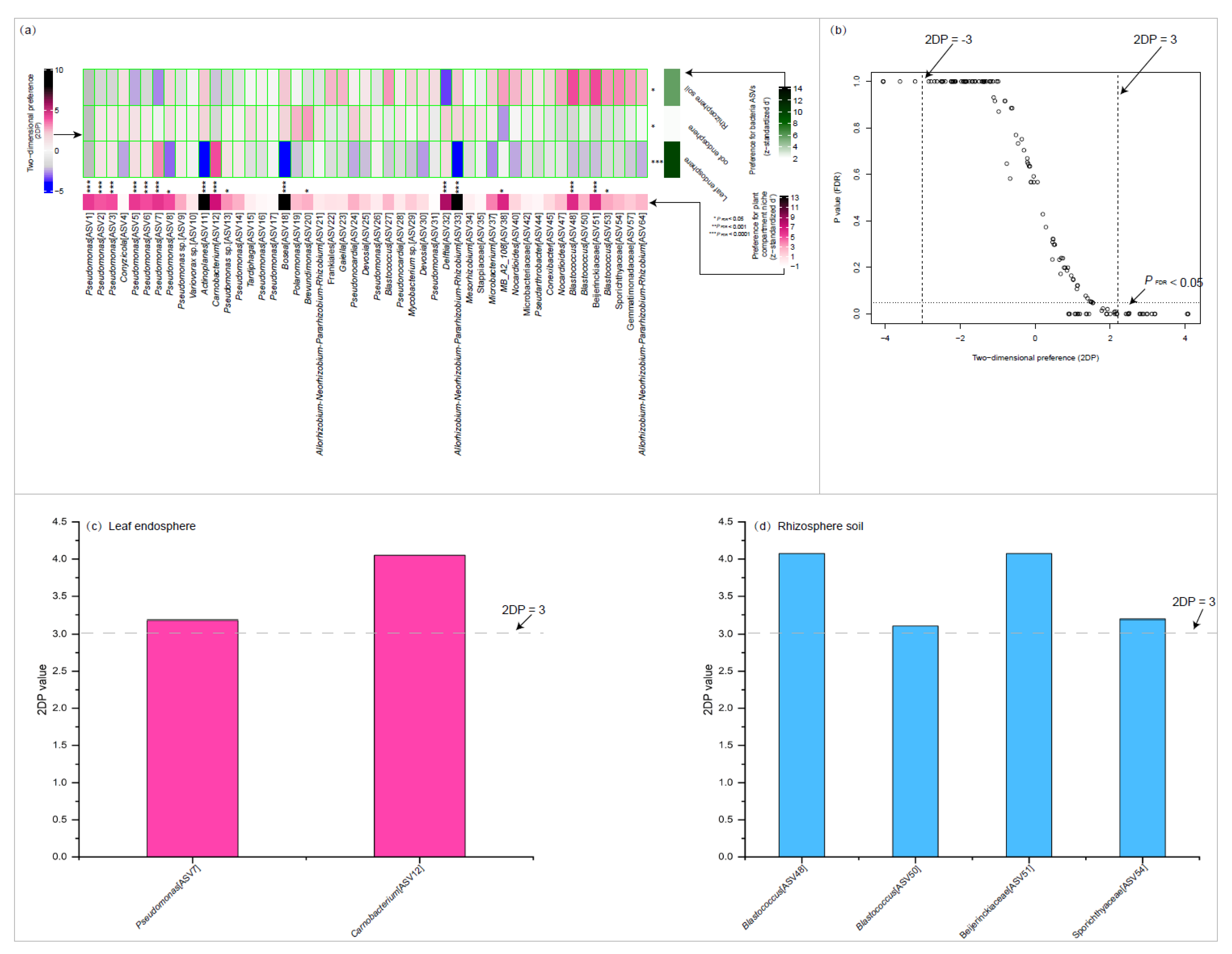

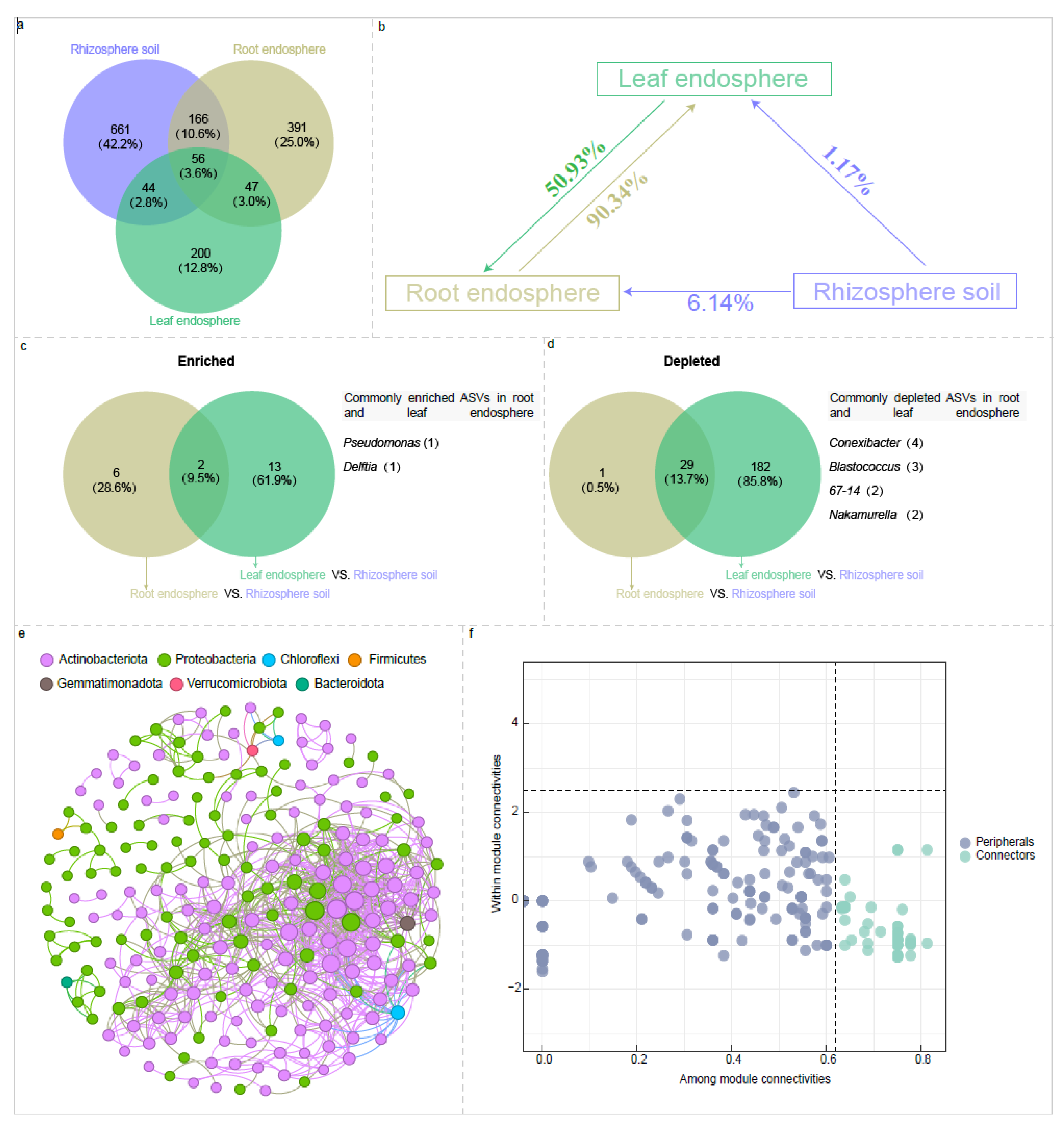

2.5. The Connections Among Bacterial Communities Within Different Plant Compartments

3. Discussion

3.1. Variations in Bacterial Community Across Different Plant Compartment Niches

3.2. The Relationship Between Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium Levels and Ratios and the Diversity and Composition of Bacterial Communities

3.3. The Connection of Bacterial Communities Across Various Plant Compartment Niches

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Site Depiction and Sampling

4.2. Sample Collection of Rhizosphere Soil, Root Endosphere, and Leaf Endosphere Fractions

4.3. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

4.4. Quantification of Total Nitrogen, Total Phosphorus, and Total Potassium Contents in Soil, Roots, and Leaves

4.5. Bioinformatic Analysis

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, J.; Jiang, H.; Dong, H.; Liu, Y. A Comprehensive Census of Lake Microbial Diversity on a Global Scale. Sci. China Life Sci. 2019, 62, 1320–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.K.; Huang, Y.; Morrill, C.; Zhao, J.; Wegener, P.; Clemens, S.C.; Colman, S.M.; Gao, L. Abundant C4 Plants on the Tibetan Plateau during the Lateglacial and Early Holocene. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2014, 87, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, C.; Häikiö, E.; Kumar, M.; Nissinen, R. Tissue-Specific Dynamics in the Endophytic Bacterial Communities in Arctic Pioneer Plant Oxyria Digyna. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenkoornhuyse, P.; Quaiser, A.; Duhamel, M.; Le Van, A.; Dufresne, A. The Importance of the Microbiome of the Plant Holobiont. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 1196–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant–Microbiome Interactions: From Community Assembly to Plant Health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, P.; Mattupalli, C.; Eversole, K.; Leach, J.E. Enabling Sustainable Agriculture through Understanding and Enhancement of Microbiomes. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 2129–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Batista, B.D.; Bazany, K.E.; Singh, B.K. Plant–Microbiome Interactions under a Changing World: Responses, Consequences and Perspectives. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1951–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Müller, D.B.; Srinivas, G.; Garrido-Oter, R.; Potthoff, E.; Rott, M.; Dombrowski, N.; Münch, P.C.; Spaepen, S.; Remus-Emsermann, M.; Hüttel, B.; McHardy, A.C.; Vorholt, J.A.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Functional Overlap of the Arabidopsis Leaf and Root Microbiota. Nature 2015, 528, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Sun, X.; He, C.; Maitra, P.; Li, X.C.; Guo, L.D. Phyllosphere Epiphytic and Endophytic Fungal Community and Network Structures Differ in a Tropical Mangrove Ecosystem. Microbiome 2019, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; He, J.Z.; Singh, B.K.; Zhu, Y.G.; Wang, J.T.; Li, P.P.; Zhang, Q.B.; Han, L.L.; Shen, J.P.; Ge, A.H.; Wu, C.F.; Zhang, L.M. Rare Taxa Maintain the Stability of Crop Mycobiomes and Ecosystem Functions. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 23, 1907–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgarelli, D.; Rott, M.; Schlaeppi, K.; Ver Loren van Themaat, E.; Ahmadinejad, N.; Assenza, F.; Rauf, P.; Huettel, B.; Reinhardt, R.; Schmelzer, E.; Peplies, J.; Gloeckner, F.O.; Amann, R.; Eickhorst, T.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Revealing Structure and Assembly Cues for Arabidopsis Root-Inhabiting Bacterial Microbiota. Nature 2012, 488, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.B.; Vogel, C.; Bai, Y.; Vorholt, J.A. The Plant Microbiota: Systems-Level Insights and Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2016, 50, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, G.; Zhu, C.; Alam, M.S.; Tokida, T.; Sakai, H.; Nakamura, H.; Usui, Y.; Zhu, J.; Hasegawa, T.; Jia, Z. Response of Soil, Leaf Endosphere and Phyllosphere Bacterial Communities to Elevated CO2 and Soil Temperature in a Rice Paddy. Plant Soil 2015, 392, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Jiao, X.Y.; Chen, Q.; Wu, A.L.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, Y.X.; He, J.Z.; Hu, H.W. Microbial Communities in Crop Phyllosphere and Root Endosphere Are More Resistant than Soil Microbiota to Fertilization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 153, 108113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.Q.W.; Sorensen, P.O.; Zhu, G.Y.; Jia, X.Y.; Liu, J.; Shangguan, Z.P.; Wang, R.W.; Yan, W.M. Differential Microbial Assembly Processes and Co-Occurrence Networks in the Soil-Root Continuum along an Environmental Gradient. iMeta 2022, 1, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, L.; Li, X.; Xiao, T.; Lu, T.; Li, J.; Deng, J.; Xiao, E. Variations in Microbial Assemblage between Rhizosphere and Root Endosphere Microbiomes Contribute to Host Plant Growth under Cadmium Stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e00960–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, T.R.; James, E.K.; Poole, P.S. The Plant Microbiome. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Zhu, Y.G.; Wang, J.T.; Singh, B.; Han, L.L.; Shen, J.P.; Li, P.P.; Wang, G.B.; Wu, C.F.; Ge, A.H.; Zhang, L.M.; He, J.Z. Host Selection Shapes Crop Microbiome Assembly and Network Complexity. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1091–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonam, W.; Liu, Y.; Guo, L. Endophytic Bacteria in the Periglacial Plant Potentilla Fruticosa Var. Albicans Are Influenced by Habitat Type. Ecol. Process. 2023, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonam, W.; Liu, Y. Plant Compartment Niche Is More Important in Structuring the Fungal Community Associated with Alpine Herbs in the Subnival Belt of the Qiangyong Glacier than Plant Species. Symbiosis 2024, 92, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Li, N.; Shao, J.; Zhou, X.; van Groenigen, K.J.; Thakur, M.P. Phenological Mismatches between Above- and Belowground Plant Responses to Climate Warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miniaci, C.; Bunge, M.; Duc, L.; Edwards, I.; Bürgmann, H.; Zeyer, J. Effects of Pioneering Plants on Microbial Structures and Functions in a Glacier Forefield. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2007, 44, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, L.C.R.S.; Peixoto, R.S.; Cury, J.C.; Sul, W.J.; Pellizari, V.H.; Tiedje, J.; Rosado, A.S. Bacterial Diversity in Rhizosphere Soil from Antarctic Vascular Plants of Admiralty Bay, Maritime Antarctica. The ISME Journal 2010, 4, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knelman, J.E. Bacterial Community Structure and Function Change in Association with Colonizer Plants during Early Primary Succession in a Glacier Forefield. Soil Biol. 2012, 46, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccazzo, S.; Esposito, A.; Rolli, E.; Zerbe, S.; Daffonchio, D.; Brusetti, L. Different Pioneer Plant Species Select Specific Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities in a High Mountain Environment. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massaccesi, L.; Benucci, G.M.N.; Gigliotti, G.; Cocco, S.; Corti, G.; Agnelli, A. Rhizosphere Effect of Three Plant Species of Environment under Periglacial Conditions (Majella Massif, Central Italy). Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 89, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapelli, F.; Marasco, R.; Fusi, M.; Scaglia, B.; Tsiamis, G.; Rolli, E.; Fodelianakis, S.; Bourtzis, K.; Ventura, S.; Tambone, F.; Adani, F.; Borin, S.; Daffonchio, D. The Stage of Soil Development Modulates Rhizosphere Effect along a High Arctic Desert Chronosequence. The ISME Journal 2018, 12, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praeg, N.; Pauli, H.; Illmer, P. Microbial Diversity in Bulk and Rhizosphere Soil of Ranunculus Glacialis Along a High-Alpine Altitudinal Gradient. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Ma, B.; Wang, G.; Tan, X. Linking Microbial Biogeochemical Cycling Genes to the Rhizosphere of Pioneering Plants in a Glacier Foreland. Sci.TotalEnviron. 2023, 872, 161944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.R.; Schluter, J.; Coyte, K.Z.; Rakoff-Nahoum, S. The Evolution of the Host Microbiome as an Ecosystem on a Leash. Nature 2017, 548, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.M.; Uroz, S.; Barker, D.G. Ancestral Alliances: Plant Mutualistic Symbioses with Fungi and Bacteria. Science 2017, 356, eaad4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordovez, V.; Dini-Andreote, F.; Carrión, V.J.; Raaijmakers, J.M. Ecology and Evolution of Plant Microbiomes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 73, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman-Derr, D.; Desgarennes, D.; Fonseca-Garcia, C.; Gross, S.; Clingenpeel, S.; Woyke, T.; North, G.; Visel, A.; Partida-Martinez, L.P.; Tringe, S.G. Plant Compartment and Biogeography Affect Microbiome Composition in Cultivated and Native Agave Species. New Phytol. 2016, 209, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Gong, X. Niche Differentiation Rather than Biogeography Shapes the Diversity and Composition of Microbiome of Cycas Panzhihuaensis. Microbiome 2019, 7, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, H.; Lei, L.; Zhang, X.; Han, D.; Wang, J.; Yao, M. The Assembly of Wheat-Associated Fungal Community Differs across Growth Stages. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 7427–7438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Bei, Q.; Dzomeku, B.M.; Martin, K.; Rasche, F. Genetic Diversity and Community Composition of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Associated with Root and Rhizosphere Soil of the Pioneer Plant Pueraria Phaseoloides. iMeta 2022, 1, e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Chai, X.; Wang, X.; Gao, B.; Li, H.; Han, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, T.; Wang, Y. Niche Differentiation Shapes the Bacterial Diversity and Composition of Apple. Hortic. Plant J. 2023, 9, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, C.P.; Uhde-Stone, C.; Allan, D.L. Phosphorus Acquisition and Use: Critical Adaptations by Plants for Securing a Nonrenewable Resource. New Phytolo. 2003, 157, 423–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, W.T. Potassium Influences on Yield and Quality Production for Maize, Wheat, Soybean and Cotton. Physiol. Plant. 2008, 133, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Fan, X.; Miller, A.J. Plant Nitrogen Assimilation and Use Efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, M.L.; Porter, S.S.; Stark, S.C.; Wettberg, E.J. von; Sachs, J.L.; Martinez-Romero, E. Microbially Mediated Plant Functional Traits. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. S. 2011, 42, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Masoudi, A.; Wang, M.; Yang, J.; Shen, R.; Man, M.; Yu, Z.; Liu, J. Community Structure and Diversity of the Microbiomes of Two Microhabitats at the Root–Soil Interface: Implications of Meta-Analysis of the Root-Zone Soil and Root Endosphere Microbial Communities in Xiong’an New Area. Can. J. Microbiol. 2020, 66, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qiu, Y.; Yao, T.; Han, D.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X. Nutrients Available in the Soil Regulate the Changes of Soil Microbial Community alongside Degradation of Alpine Meadows in the Northeast of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 792, 148363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molefe, R.R.; Amoo, A.E.; Babalola, O.O. Communication between Plant Roots and the Soil Microbiome; Involvement in Plant Growth and Development. Symbiosis 2023, 90, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Pan, B. Numerical Reconstruction of Three Holocene Glacial Events in Qiangyong Valley, Southern Tibetan Plateau and Their Implication for Holocene Climate Changes. Water 2020, 12, 3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; Bai, Y.; Bisanz, J.E.; Bittinger, K.; Brejnrod, A.; Brislawn, C.J.; Brown, C.T.; Callahan, B.J.; Caraballo-Rodríguez, A.M.; Chase, J.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Kaehler, B.D.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.; Bolyen, E.; Knight, R.; Huttley, G.A.; Gregory Caporaso, J. Optimizing Taxonomic Classification of Marker-Gene Amplicon Sequences with QIIME 2’s Q2-Feature-Classifier Plugin. Microbiome 2018, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Gae ̈l, V.; Alexandre, G.; Vincent, M.; Bertrand, T. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA Ribosomal RNA Gene Database Project: Improved Data Processing and Web-Based Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2 – Approximately Maximum-Likelihood Trees for Large Alignments. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Ren, Y.; Xiong, W.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Miao, Y.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Specialized Metabolic Functions of Keystone Taxa Sustain Soil Microbiome Stability. Microbiome 2021, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knights, D.; Kuczynski, J.; Charlson, E.S.; Zaneveld, J.; Mozer, M.C.; Collman, R.G.; Bushman, F.D.; Knight, R.; Kelley, S.T. Bayesian Community-Wide Culture-Independent Microbial Source Tracking. Nat Methods 2011, 8, 761–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toju, H.; Tanabe, A.S.; Ishii, H.S. Ericaceous Plant–Fungus Network in a Harsh Alpine–Subalpine Environment. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 3242–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdös, P.; Rényi, A. On the Evolution of Random Graphs. In The Structure and Dynamics of Networks; Princeton University Press, 2011, 38–82, ISBN 978-1-4008-4135-6.

- Guimerà, R.; Nunes Amaral, L.A. Functional Cartography of Complex Metabolic Networks. Nature 2005, 433, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De’ath, G. Boosted Trees for Ecological Modeling and Prediction. Ecology 2007, 88, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; He, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y. Differences in Soil Bacterial Diversity: Driven by Contemporary Disturbances or Historical Contingencies? The ISME Journal 2008, 2, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.G.I.; Berga, M.; Lindström, E.S.; Langenheder, S. The Spatial Structure of Bacterial Communities Is Influenced by Historical Environmental Conditions. Ecology 2014, 95, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Lemanceau, P.; Van Der Putten, W.H. Going Back to the Roots: The Microbial Ecology of the Rhizosphere. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, B.; Wu, M.; Chen, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shi, M.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, L.; Zhang, D. Leaf and Root Endospheres Harbor Lower Fungal Diversity and Less Complex Fungal Co-Occurrence Patterns Than Rhizosphere. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Sun, X.; He, C.; Li, X.C.; Guo, L.D. Host Identity Is More Important in Structuring Bacterial Epiphytes than Endophytes in a Tropical Mangrove Forest. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buée, M.; De Boer, W.; Martin, F.; van Overbeek, L.; Jurkevitch, E. The Rhizosphere Zoo: An Overview of Plant-Associated Communities of Microorganisms, Including Phages, Bacteria, Archaea, and Fungi, and of Some of Their Structuring Factors. Plant Soil. 2009, 321, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, B.; Op De Beeck, M.; Weyens, N.; Boerjan, W.; Vangronsveld, J. Structural Variability and Niche Differentiation in the Rhizosphere and Endosphere Bacterial Microbiome of Field-Grown Poplar Trees. Microbiome 2017, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loreau, M.; de Mazancourt, C. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Stability: A Synthesis of Underlying Mechanisms. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratou, M.; Maitre, A.; Abuin-Denis, L.; Piloto-Sardiñas, E.; Corona-Guerrero, I.; Cano-Argüelles, A.L.; Wu-Chuang, A.; Bamgbose, T.; Almazan, C.; Mosqueda, J.; Obregón, D.; Mateos-Hernández, L.; Said, M.B.; Cabezas-Cruz, A. Disruption of Bacterial Interactions and Community Assembly in Babesia-Infected Haemaphysalis Longicornis Following Antibiotic Treatment. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D.J.; David, A.S.; Menges, E.S.; Searcy, C.A.; Afkhami, M.E. Environmental Stress Destabilizes Microbial Networks. The ISME Journal 2021, 15, 1722–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, A.; Das, S.; Chakdar, H.; Varma, A.; Saxena, A.K. Diversity of Bacterial Endophytes of Maize (Zea Mays) and Their Functional Potential for Micronutrient Biofortification. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 79, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Khatun, A.; Islam, T. Promotion of Plant Growth by Phytohormone Producing Bacteria. Microbes in action; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purtschert-Montenegro, G.; Cárcamo-Oyarce, G.; Pinto-Carbó, M.; Agnoli, K.; Bailly, A.; Eberl, L. Pseudomonas Putida Mediates Bacterial Killing, Biofilm Invasion and Biocontrol with a Type IVB Secretion System. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1547–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellagi, A.; Quillere, I.; Hirel, B. Beneficial Soil-Borne Bacteria and Fungi: A Promising Way to Improve Plant Nitrogen Acquisition. J. Exp. Bot 2020, 71, 4469–4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nuland, M.E.; Peay, K.G. Symbiotic Niche Mapping Reveals Functional Specialization by Two Ectomycorrhizal Fungi That Expands the Host Plant Niche. Fungal Ecol. 2020, 46, 100960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, Q.; Xiukang, W.; Haider, F.U.; Kučerik, J.; Mumtaz, M.Z.; Holatko, J.; Naseem, M.; Kintl, A.; Ejaz, M.; Naveed, M.; Brtnicky, M.; Mustafa, A. Rhizosphere Bacteria in Plant Growth Promotion, Biocontrol, and Bioremediation of Contaminated Sites: A Comprehensive Review of Effects and Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, C.; Guan, C.; Feng, X.; Yan, D.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, Y.; Xiong, S.; Zhang, W.; Cai, X.; Hu, L. Analysis of the Composition and Function of Rhizosphere Microbial Communities in Plants with Tobacco Bacterial Wilt Disease and Healthy Plants. Microbiol. spectr. 2024, 12, e00559-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, Q.; Shen, Q.; Guo, S. The Critical Role of Potassium in Plant Stress Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7370–7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarraonaindia, I.; Owens, S.M.; Weisenhorn, P.; West, K.; Hampton-Marcell, J.; Lax, S.; Bokulich, N.A.; Mills, D.A.; Martin, G.; Taghavi, S.; van der Lelie, D.; Gilbert, J.A. The Soil Microbiome Influences Grapevine-Associated Microbiota. mBio 2015, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.R.; Lundberg, D.S.; del Rio, T.G.; Tringe, S.G.; Dangl, J.L.; Mitchell-Olds, T. Host Genotype and Age Shape the Leaf and Root Microbiomes of a Wild Perennial Plant. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, A.; Tack, A.J.M.; Lobato, C.; Wassermann, B.; Berg, G. From Seed to Seed: The Role of Microbial Inheritance in the Assembly of the Plant Microbiome. Trends. Microbiol. 2023, 31, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Amico, E.; Cavalca, L.; Andreoni, V. Improvement of Brassica Napus Growth under Cadmium Stress by Cadmium-Resistant Rhizobacteria. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berney, M.; Cook, G.M. Unique Flexibility in Energy Metabolism Allows Mycobacteria to Combat Starvation and Hypoxia. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e8614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, G.; Sbodio, A.; Tech, J.J.; Suslow, T.V.; Coaker, G.L.; Leveau, J.H.J. Leaf Microbiota in an Agroecosystem: Spatiotemporal Variation in Bacterial Community Composition on Field-Grown Lettuce. The ISME Journal 2012, 6, 1812–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, R.A.; Mahnert, A.; Berg, C.; Müller, H.; Berg, G. The Plant Is Crucial: Specific Composition and Function of the Phyllosphere Microbiome of Indoor Ornamentals. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.T.; Zhang, Z.F.; Li, W.; Chen, W.; Cai, L. Microbiota in the Rhizosphere and Seed of Rice From China, With Reference to Their Transmission and Biogeography. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, G.; Kim, I.; Kang, M.; Kim, J.; So, Y.; Seo, T. Devosia rhizoryzae sp. nov., and Devosia oryziradicis sp. nov., Novel Plant Growth Promoting Members of the Genus Devosia, Isolated from the Rhizosphere of Rice Plants. J Microbiol. 2022, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asaf, S. Osmoprotective Functions Conferred to Soybean Plants via Inoculation with Sphingomonas sp. LK11 and Exogenous Trehalose. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, J.; You, Y.; Wang, R.; Chu, S.; Chi, Y.; Hayat, K.; Hui, N.; Liu, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, P. When Nanoparticle and Microbes Meet: The Effect of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on Microbial Community and Nutrient Cycling in Hyperaccumulator System. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 126947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, R.; Ulrich, K.; Behrendt, U.; Schneck, V.; Ulrich, A. Genomic Characterization of Aureimonas altamirensis C2P003—A Specific Member of the Microbiome of Fraxinus Excelsior Trees Tolerant to Ash Dieback. Plants 2022, 11, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, V.V.; Monsalud, R.G.; Yokota, A. Devosia yakushimensis sp. nov., Isolated from Root Nodules of Pueraria Lobata (Willd.) Ohwi. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr. 2010, 60, 627–632. [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, G.; Kim, I.; Kang, M.; So, Y.; Kim, J.; Seo, T. An Isolated Arthrobacter sp. Enhances Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Plant Growth. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.H.; Cao, R.; Fazal, A.; Zheng, K.; Na, Z.; Yang, Y.; Sun, B.; Yang, H.; Na, Z.-Y. Composition and Diversity of Root-Inhabiting Bacterial Microbiota in the Perennial Sweet Sorghum Cultivar at the Maturing Stage. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 99, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.H.; Yoon, A.R.; Oh, H.E.; Park, Y.G. Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganism Pseudarthrobacter sp. NIBRBAC000502770 Enhances the Growth and Flavonoid Content of Geum Aleppicum. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiyama, Y.; Thao, N.K.N.; Vinh, H.V.; Giang, N.M.; Miyadoh, S.; Hop, D.V.; Ando, K. Pseudonocardia babensis sp. nov., Isolated from Plant Litter. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 2336–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatmough, B.; Holmes, N.A.; Wilkinson, B.; Hutchings, M.I.; Parra, J.; Duncan, K.R. Microbe Profile: Pseudonocardia: Antibiotics for Every Niche. Microbiology 2024, 170, 001501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desnoues, N.; Lin, M.; Guo, X.; Ma, L.; Carreño-Lopez, R.; Elmerich, C. Nitrogen Fixation Genetics and Regulation in a Pseudomonas stutzeri Strain Associated with Rice. Microbiology 2003, 149, 2251–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; He, Y.; Feng, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, S. Pseudomonas fluorescens Inoculation Enhances Salix matsudana Growth by Modifying Phyllosphere Microbiomes, Surpassing Nitrogen Fertilization. Plant. Cell. Environ. 2025, 48, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y. Pseudonocardia profundimaris sp. nov., Isolated from Marine Sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micr. 2017, 67, 1693–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Chen, J.; Ren, S.; Shen, H.; Rong, B.; Liu, W.; Yang, Z. Complete Genome Sequence of Mycobacterium Mya-Zh01, an Endophytic Bacterium, Promotes Plant Growth and Seed Germination Isolated from Flower Stalk of Doritaenopsis. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 1965–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Multiple comparison | ADONIS | ANOSIM | MRPP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | P | R | P | δ | P | ||

| Bray–Curtis dissimilarity | Le vs. Re vs. Rs | 0.453 | 0.001 | 0.661 | 0.011 | 0.502 | 0.001 |

| Le vs. Re | 0.307 | 0.001 | 0.475 | 0.004 | 0.416 | 0.006 | |

| Le vs. Rs | 0.509 | 0.004 | 0.850 | 0.002 | 0.462 | 0.005 | |

| Re vs. Rs | 0.282 | 0.004 | 0.661 | 0.011 | 0.631 | 0.008 | |

| Unifrac dissimilarity | Le vs. Re vs. Rs | 0.236 | 0.001 | 0.532 | 0.001 | 0.803 | 0.001 |

| Le vs. Re | 0.143 | 0.028 | 0.245 | 0.034 | 0.839 | 0.021 | |

| Le vs. Rs | 0.218 | 0.001 | 0.702 | 0.002 | 0.804 | 0.004 | |

| Re vs. Rs | 0.195 | 0.003 | 0.651 | 0.003 | 0.766 | 0.005 | |

| ASV | Taxonomy | Plant compartment niche | Indval value (>0.7) |

p.value (< 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASV1 | Pseudomonas | Leaf endosphere | 0.736 | 0.003 |

| ASV2 | Pseudomonas | Leaf endosphere | 0.886 | 0.005 |

| ASV5 | Pseudomonas | Leaf endosphere | 0.850 | 0.009 |

| ASV7 | Pseudomonas | Leaf endosphere | 0.939 | 0.003 |

| ASV12 | Carnobacterium | Leaf endosphere | 1.000 | 0.001 |

| ASV4 | Conyzicola | Root endosphere | 0.965 | 0.047 |

| ASV19 | Polaromonas | Root endosphere | 0.834 | 0.023 |

| ASV20 | Brevundimonas | Root endosphere | 0.775 | 0.02 |

| ASV32 | Delftia | Root endosphere | 0.805 | 0.041 |

| ASV22 | Frankiales | Rhizosphere soil | 0.987 | 0.001 |

| ASV23 | Gaiella | Rhizosphere soil | 0.968 | 0.001 |

| ASV27 | Blastococcus | Rhizosphere soil | 0.873 | 0.003 |

| ASV33 | Allorhizobium-Neorhizobium-Pararhizobium-Rhizobium | Rhizosphere soil | 0.820 | 0.007 |

| ASV38 | MB-A2-108 | Rhizosphere soil | 0.983 | 0.001 |

| ASV40 | Nocardioides | Rhizosphere soil | 0.964 | 0.001 |

| ASV42 | Microbacteriaceae | Rhizosphere soil | 0.811 | 0.024 |

| ASV47 | Nocardioides | Rhizosphere soil | 0.970 | 0.001 |

| ASV48 | Blastococcus | Rhizosphere soil | 1.000 | 0.001 |

| ASV50 | Blastococcus | Rhizosphere soil | 0.899 | 0.003 |

| ASV51 | Beijerinckiaceae | Rhizosphere soil | 1.000 | 0.001 |

| ASV53 | Blastococcus | Rhizosphere soil | 0.816 | 0.014 |

| ASV54 | Sporichthyaceae | Rhizosphere soil | 0.967 | 0.001 |

| ASV57 | Gemmatimonadaceae | Rhizosphere soil | 0.939 | 0.001 |

| ASV64 | Allorhizobium-Neorhizobium-Pararhizobium-Rhizobium | Rhizosphere soil | 0.839 | 0.013 |

| Network properties | Leaf endosphere | Root endosphere | Rhizosphere soil |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed networks | |||

| Edges | 66.00 | 932.00 | 3424.00 |

| Nodes | 35.00 | 152.00 | 359.00 |

| clustering coefficient | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| Average path length | 1.00 | 1.01 | 1.00 |

| Modularity | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.86 |

| graph.density | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Diameter | 1.00 | 1.97 | 1.00 |

| Average degree | 3.77 | 12.26 | 19.08 |

| Random networks | |||

| Average path length | 0.69 ± 0.09 | 0.29 ± 0.004 | 0.29 ± 0.002 |

| Clustering coefficient | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.004 | 0.05 ± 0.002 |

| Modularity | 0.397 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.007 | 0.19 ± 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).