1. Introduction

In recent years, studying atom–field interactions has become a cornerstone of quantum optics and quantum information science. At the heart of these investigations lies the Jaynes–Cummings model (JCM) [

5,

6,

7,

8], which describes the fundamental interaction between a quantized electromagnetic field and a two-level atom. This model has provided profound insights into the dynamics of light-matter interaction and paved the way for exploring complex phenomena such as QE and state evolution. Our work extends this classical framework by incorporating several external perturbations, namely, a time-dependent SS, detuning, atomic motion, and a nonzero initial phase, to examine their combined influence on QE. QE is a fundamental phenomenon in quantum mechanics that defies classical intuition. It describes a scenario in which particles become so intricately connected that the state of each particle cannot be described independently of the state of the others, regardless of the distance separating them [

9]. This non-classical correlation has been pivotal in demonstrating the failure of local hidden variable theories, as evidenced by the violation of Bell inequalities [

10,

11]. Experimental progress has shown that entangled states can remain robust even in the presence of noise and decoherence, thereby paving the way for practical applications in quantum computing, secure communication, and teleportation [

12]. The deep insights gained from studying these correlations continue to fuel advancements in quantum technologies, providing a vital resource for optimizing quantum information processing and control strategies [

13].

A central aspect of our investigation is the Stark effect, which refers to the shift in atomic energy levels caused by an external electric field [

14,

15] Even modest SSs can dynamically modulate the effective detuning between the atom and the field, thereby altering the strength and nature of their coupling. These energy shifts play a critical role in shaping the oscillatory behavior of the system, affecting both the amplitude and frequency of Rabi oscillations [

15,

16]. In turn, these modulations have a significant impact on the evolution of QE, as they either enhance or suppress the coupling responsible for entangled states [

27,

28]. This sensitivity to external fields has important implications for quantum control protocols, where precise manipulation of the Stark parameter can be used to optimize QE generation.

In addition to the Stark effect, atomic motion introduces further complexity into the dynamics. In practical systems, such as trapped ions or atoms confined within optical cavities, the motional degrees of freedom are non-negligible and give rise to vibrational sidebands [

33,

34,

35,

36]. These sidebands effectively broaden the energy spectrum available to the atom, leading to additional channels for energy exchange that modify the standard Jaynes–Cummings interactions [

38,

39,

40] The resulting dynamics are richer and more complex, as the interplay between vibrational modes and electromagnetic fields creates new pathways for QE generation and decay. Understanding these motional effects is crucial for developing robust quantum state engineering techniques and realizing scalable quantum computing architectures [

41,

42,

43,

44]. To comprehensively characterize the quantum correlations emerging from these interactions, our study employs four key QE quantifiers: the QFI, the VNE, Neg, and the Geometric Phase (GP). The QFI quantifies the sensitivity of a quantum state to small parameter variations, serving as a crucial indicator of the precision limits in quantum metrology [

18,

19,

20]. In our system, low values of the Stark parameter yield nearly sinusoidal QFI oscillations that mirror the smooth dynamics predicted by the ideal JCM, whereas higher SSs induce rapid, high-amplitude fluctuations indicative of burst-like QE dynamics.

The VNE, which measures the mixedness of a quantum state, offers a complementary perspective by quantifying how far a system deviates from a pure state [

21,

22]. Under conditions of weak Stark modulation, the VNE remains relatively low, suggesting that the system retains a high degree of purity and that QE evolves gradually. Conversely, stronger Stark shifts cause the VNE to exhibit large, abrupt variations as the system rapidly transitions between nearly pure and significantly mixed states. These fluctuations provide valuable insights into the decoherence processes and the overall stability of the entangled state. Neg, defined through the partial transposition of the density matrix, offers a direct and robust measure of bipartite QE [

1,

2,

3,

4,

30,

31] In regimes where the Stark parameter is low, the Neg peaks are modest, reflecting only weak QE between the atom and the field. However, as the Stark shift intensifies, the Neg displays pronounced, narrow spikes, corresponding to short-lived but intense bursts of QE. Such behavior underscores the system’s heightened sensitivity to external perturbations and highlights the potential for leveraging these dynamics in quantum information protocols. Finally, the GP provides a unique window into the phase evolution of the quantum state, capturing the phase contribution arising solely from the path traversed in state space, independent of dynamical evolution [

23,

24,

25,

26]. When the Stark shift is minimal, the GP accumulates smoothly over time, consistent with a gradual evolution of the system. In contrast, strong Stark modulation causes the GP to change abruptly, sometimes even reversing direction over short time intervals. These rapid phase shifts indicate complex interference phenomena and are intimately linked to the sudden changes observed in the other QE measures.

Moreover, the introduction of a nonzero initial phase (

) further enriches these dynamics by altering the interference pattern between the atom and the field [

27,

28]. This phase factor not only shifts the timing of QE peaks but also modulates their amplitude. When combined with detuning and atomic motion, the influence of the initial phase becomes even more pronounced, leading to highly nontrivial behavior in all four QE quantifiers [

15,

16,

17,

18,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. The resulting multifaceted interplay is critical for devising advanced quantum control strategies and for mitigating the effects of environmental noise on quantum coherence [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54].

By systematically varying the Stark parameter from values as low as where the system closely follows the ideal Jaynes–Cummings dynamics to values around 3, our detailed numerical analysis reveals a sensitive dependence of quantum correlations on external perturbations. The comprehensive insights obtained from the QFI, VNE, Neg, and Neg deepen our understanding of atom–field interactions and provide a solid foundation for the precise engineering of entangled states in practical quantum devices.

In

Section 2, we discuss the system’s model in terms of the Hamiltonian. In

Section 3, QE quantifiers are introduced.

Section 4 presents the numerical analysis and its relation to previous research. In

Section 5, the experimental realization of the model is addressed. Finally,

Section 6 provides the conclusion.

2. Hamiltonian Model

We consider moving three-level atoms entering the cavity at time

in the superposition state in the presence of the time-dependent SE. We consider the cascade configuration of moving a three-level atomic system in the presence of the time-dependent SS. The system considered in this study comprises a three-level atomic cascade interacting with a single-mode quantized electromagnetic field. This interaction incorporates the effects of the SE, detuning, and atomic motion. The evolution of the system is analyzed through key quantum observables such as QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg. The three-level atom consists of discrete energy levels

,

, and

. The atomic transitions

and

are coupled to the electromagnetic field with coupling strengths

and

, respectively. The dynamics of the atom-field interaction are governed by the total Hamiltonian [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]:

The field Hamiltonian describes the single-mode quantized electromagnetic field:

where

and

a denote the creation and annihilation operators of the field, and

is the field frequency.

The atomic Hamiltonian accounts for the internal energy levels of the atom:

where

are atomic transition operators.

The interaction between the atom and the electromagnetic field is described by the Hamiltonian without RWA [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]

where

is a modulation factor arising from atomic motion, with

, where

w represents a motion-related parameter,

v is the velocity, and

L is the interaction length.

c is the parameter of atomic motion. When

, the atomic motion is not present, but when

is not equal to 1, then atomic motion is present.

The SS introduces a time-dependent term due to the interaction of the electric field with the atomic dipole moment:

where

is the SE parameter,

is the identity operator on the atomic Hilbert space, and the electric field operator is:

with

being the amplitude of the electric field.

The detuning terms account for the differences between the atomic transition frequencies and the field frequency:

where

and

are the detuning parameters for the respective transitions.

The field is initialized in a

coherent state , defined as:

where:

: photon number (Fock) states,

: complex amplitude of the field.

The density matrix representation of the coherent state is:

normalized such that

.

The phase gate modifies each photon state

by introducing a phase

:

After applying the phase gate, the modified coherent state is:

The new density matrix becomes:

and it is normalized to

.

The atom is modeled as a three-level system with states:

The atomic operators are defined as:

, where

,

: transitions between

and

,

: transitions between

and

.

The initial atomic state is assumed to be in the ground state:

The combined atom-field state is represented by the

tensor product:

which becomes a

matrix if

has dimension

d.

The joint system evolves according to the unitary operator:

The time-evolved density matrix is:

To isolate the atomic state, trace out the field degrees of freedom:

This operation reduces the joint matrix to a matrix for the atom.

The joint density matrix of the atom and field system is given by: where: is the density matrix of the combined atom-field system, with dimensions , is the atomic density matrix of size , is the field density matrix of size To isolate the reduced density matrix of the atomic subsystem, we perform a partial trace over the field degrees of freedom: The partial trace sums over all possible field states, reducing the joint density matrix to a matrix that only describes the atomic subsystem.

The element of the reduced density matrix

is computed as:

where:

are indices of the atomic subsystem.

runs over the field degrees of freedom.

For example (Two Levels and Two Photons): If the joint density matrix is:

and if

and

, then the reduced density matrix is obtained as:

Here, the summation is over the field indices (

).

The reduced density matrix for the atomic subsystem is constructed as:

This function iterates over the atomic indices i,j and sums over the field indices k, resulting in the reduced atomic density matrix. The phase gate modifies the field state by introducing a phase to each photon number state . This altered field state interacts with the atom through the interaction Hamiltonian, leading to the coupling between the atom and the modified field, causing the atomic populations to oscillate differently compared to the unmodified field. The phase affects the coherence terms of the atomic state.

3. QE Quantifiers

3.1. QFI

QFI quantifies the amount of information that a quantum state carries about a parameter to be estimated. It plays a fundamental role in quantum metrology, determining the ultimate precision limit achievable in parameter estimation tasks. The QFI is linked to the distinguishability of quantum states, often evaluated using the symmetric logarithmic derivative (SLD) operator [

59]. Higher QFI values correspond to greater sensitivity in the estimation of parameters QFI measures the sensitivity of the state to phase changes:

where

are eigenvalues of

.

3.2. VNE

VNE is a measure of the quantum uncertainty or information content of a quantum state. Defined as

, where

is the density matrix, VNE quantifies the degree of mixedness of a quantum state. It is widely used in quantum information theory to study QE and correlations in composite systems [

61]. A pure state has a VNE of zero, while mixed states have positive entropy values.

3.3. GP

The GP arises when a quantum system undergoes a cyclic evolution, resulting in a phase factor that depends only on the path taken in the parameter space, not the dynamics. First introduced by Berry in 1984, this phase is pivotal in understanding various quantum phenomena such as quantum holonomies and topological effects [

62]. The GP is widely used in quantum computing and other applications, as it is robust against certain types of errors. The GP is:

3.4. Neg

QE is a fundamental resource in quantum information science. One widely used QE measure for bipartite systems is Neg. This measure is based on the partial transposition criterion for separability, which was originally introduced by Peres [

63] and further developed by Vidal and Werner [

64].

Let

be the density matrix of a bipartite quantum system defined on the Hilbert space

The partial transpose of

with respect to subsystem

A, denoted by

, is defined by its matrix elements:

where

and

form an orthonormal basis for

, and

and

for

.

The Neg is then given by

where

denotes the trace norm defined as

This measure quantifies the degree to which

fails to be positive semidefinite. A nonzero Neg indicates the presence of QE in the state

, whereas

implies that

is separable. Neg is particularly useful for low-dimensional quantum systems because it is both computationally accessible and physically insightful. Its simplicity has made it a popular choice in both theoretical investigations and experimental applications to quantify quantum correlations. The mathematical formulation of Neg provides a clear and straightforward method for quantifying QE in bipartite systems. By measuring the deviation from positivity in the partial transpose of a state, Neg serves as an effective indicator of quantum QE.

This theoretical framework provides a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of a three-level atom interacting with a coherent field, incorporating both static and time-dependent interactions. The quantities QFI, VNE, GP and Neg are computed during the time evolution, and their behavior reflects the influence of the phase-modified field on the atom. This describes the mathematical framework for simulating the interaction of a three-level atom with a phase-modified coherent field. The model includes the effects of atomic motion and calculates key quantum properties such as VNE, QFI, GP, and Neg.

Now, the influence of different parameters ,, and on the evolution of the QFI, VNE, GP and Neg is presented in the next section.

4. Numerical Results and Discussions

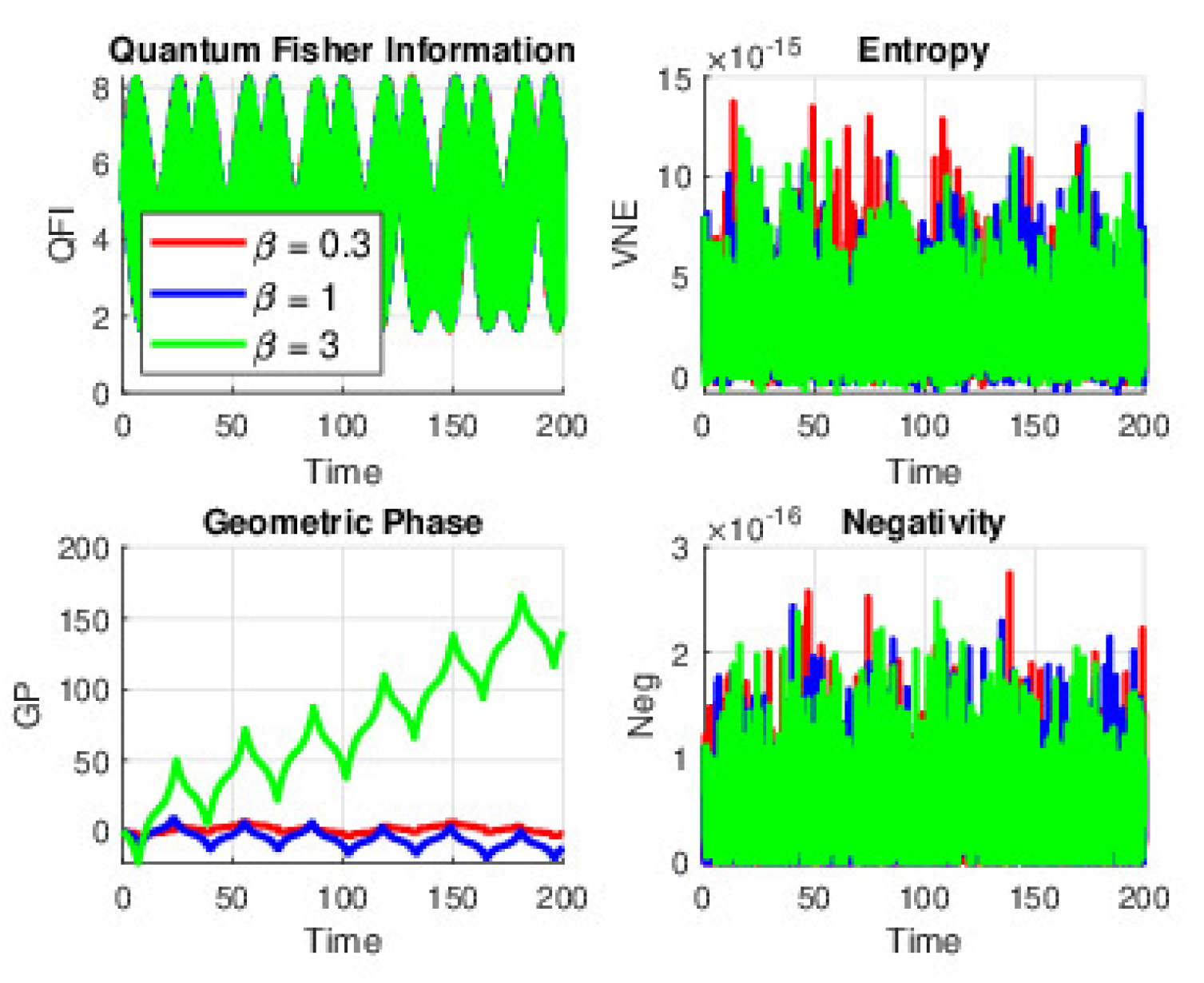

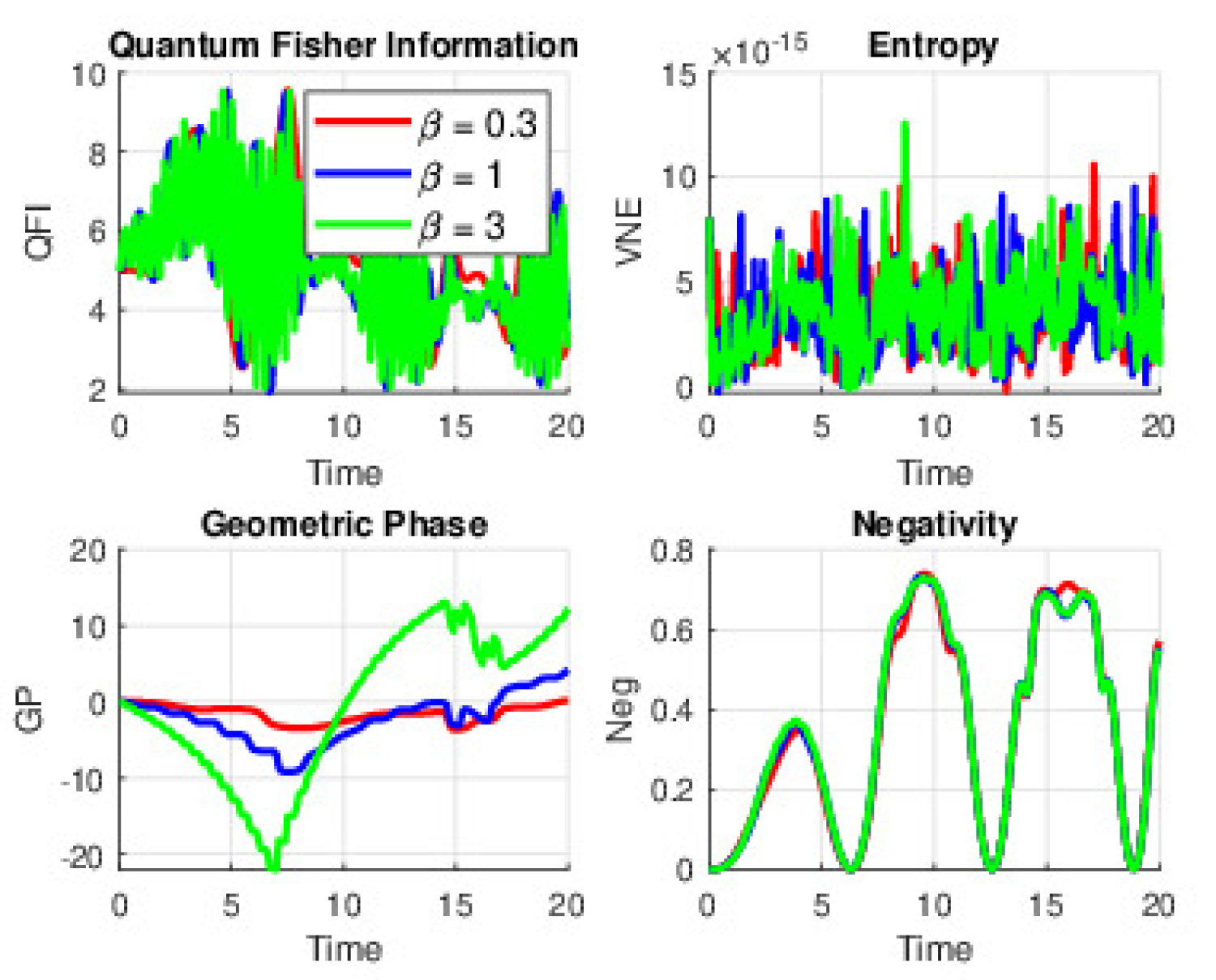

When is set to 0 and atomic motion is not considered, the dynamics are predominantly governed by the time-dependent Stark parameter (). At a low value, around , the energy shift remains modest. This results in behavior closely resembling the traditional Jaynes–Cummings model, where the atom and field exchange energy in smooth, nearly sinusoidal Rabi oscillations. The QE measures including QFI, VNE, and Neg display only gentle, low-amplitude oscillations. As increases to about 1, the SS becomes more pronounced, leading to stronger modulations of the atomic transition frequency. Consequently, the QE cycles become more distinct, with sharper peaks in Neg and more marked oscillatory behavior in QFI and VNE. When reaches approximately 3, the modulation is so strong that the system is rapidly driven in and out of effective resonance, which produces abrupt, high-amplitude spikes in these measures. The GP also shows abrupt changes, accumulating more rapidly and sometimes even reversing over short intervals.

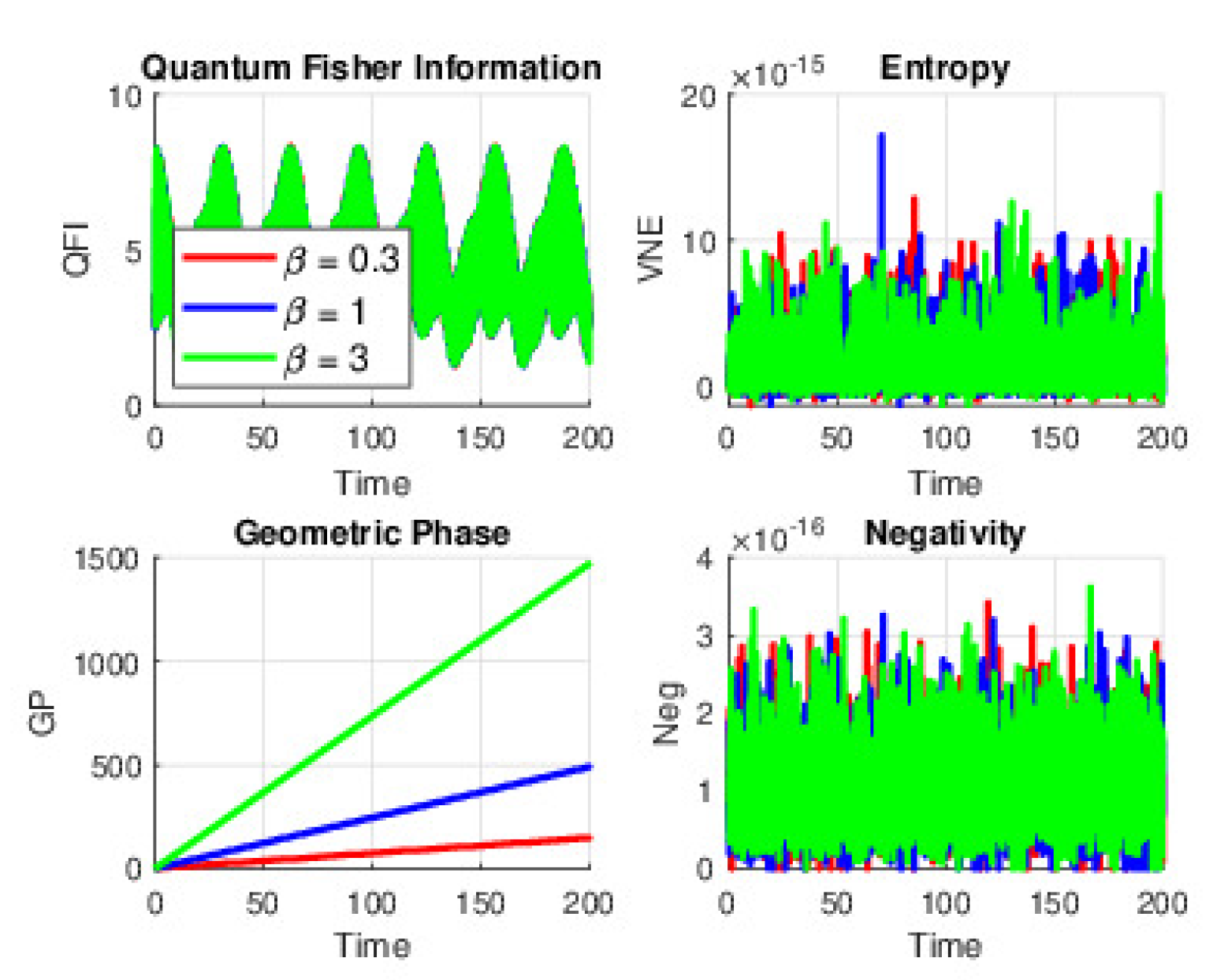

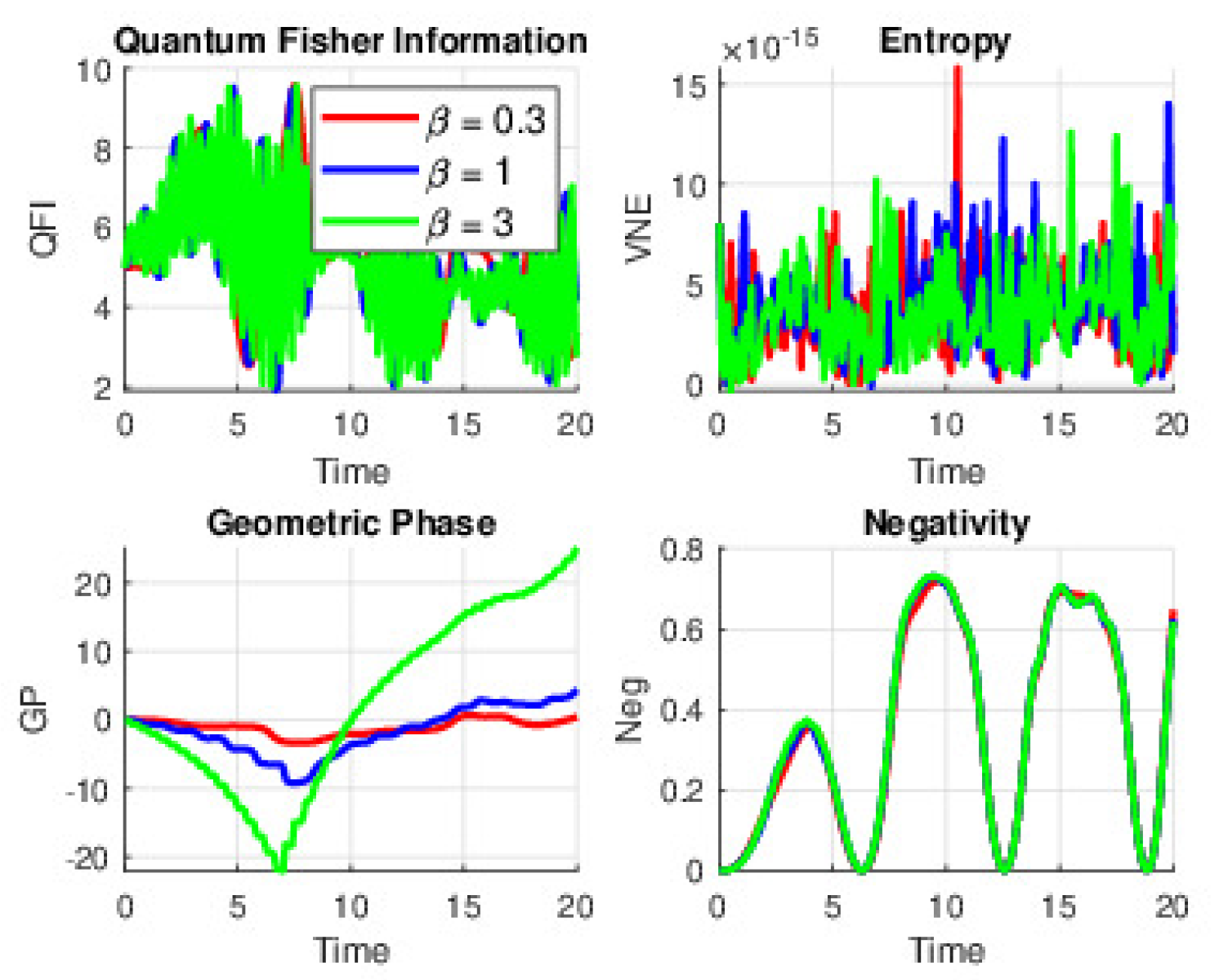

When is adjusted to while neglecting atomic motion, the additional initial phase alters the interference between the atom and field. At , the system still exhibits near-Jaynes–Cummings behavior, but the timing and amplitude of the QE peaks are modestly shifted compared to the scenario. As increases to about 1, these phase-induced effects become more significant, resulting in QE bursts that may occur slightly earlier or later, with the peaks in Neg and QFI showing greater variation. At higher modulation (), the interference effect is greatly enhanced; theQE peaks become both taller and narrower, indicating that the extra phase strongly redistributes the energy exchange and correlation dynamics.

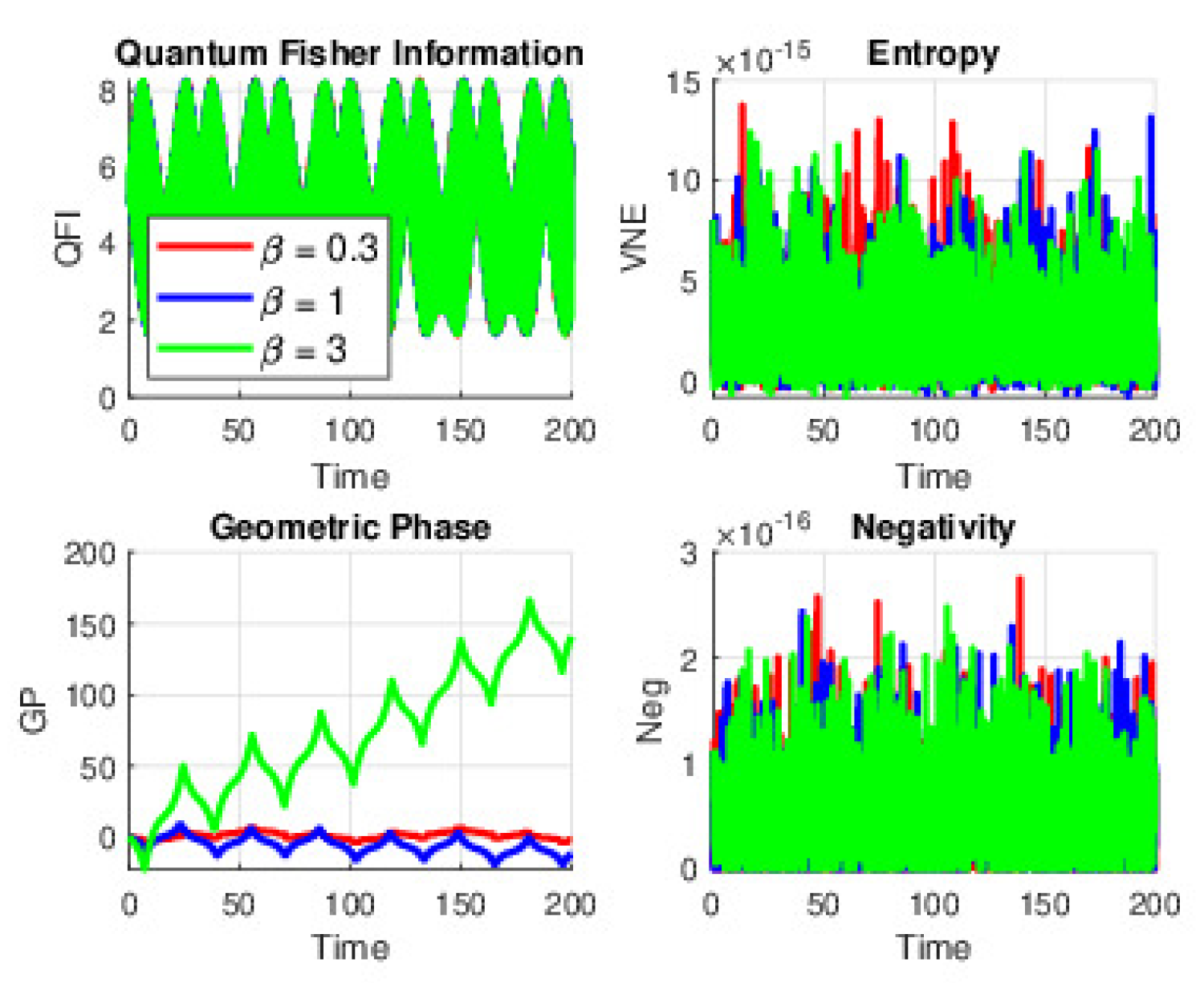

Introducing a nonzero detuning while keeping (and still ignoring atomic motion) shifts the system off the ideal resonance. For near , the off-resonant condition leads to a reduction in the amplitude of the oscillations in QFI and Neg, while the VNE exhibits only modest fluctuations. As increases to 1, the SS can intermittently bring the atom closer to resonance despite the detuning, resulting in sharper and higher peaks in the QE measures. When is raised to around 3, the interplay of a strong Stark modulation with detuning causes rapid, high-amplitude oscillations, where Neg spikes are very pronounced and both QFI and VNE exhibit abrupt changes. The GP, too, responds dramatically, increasing steeply during brief resonant episodes.

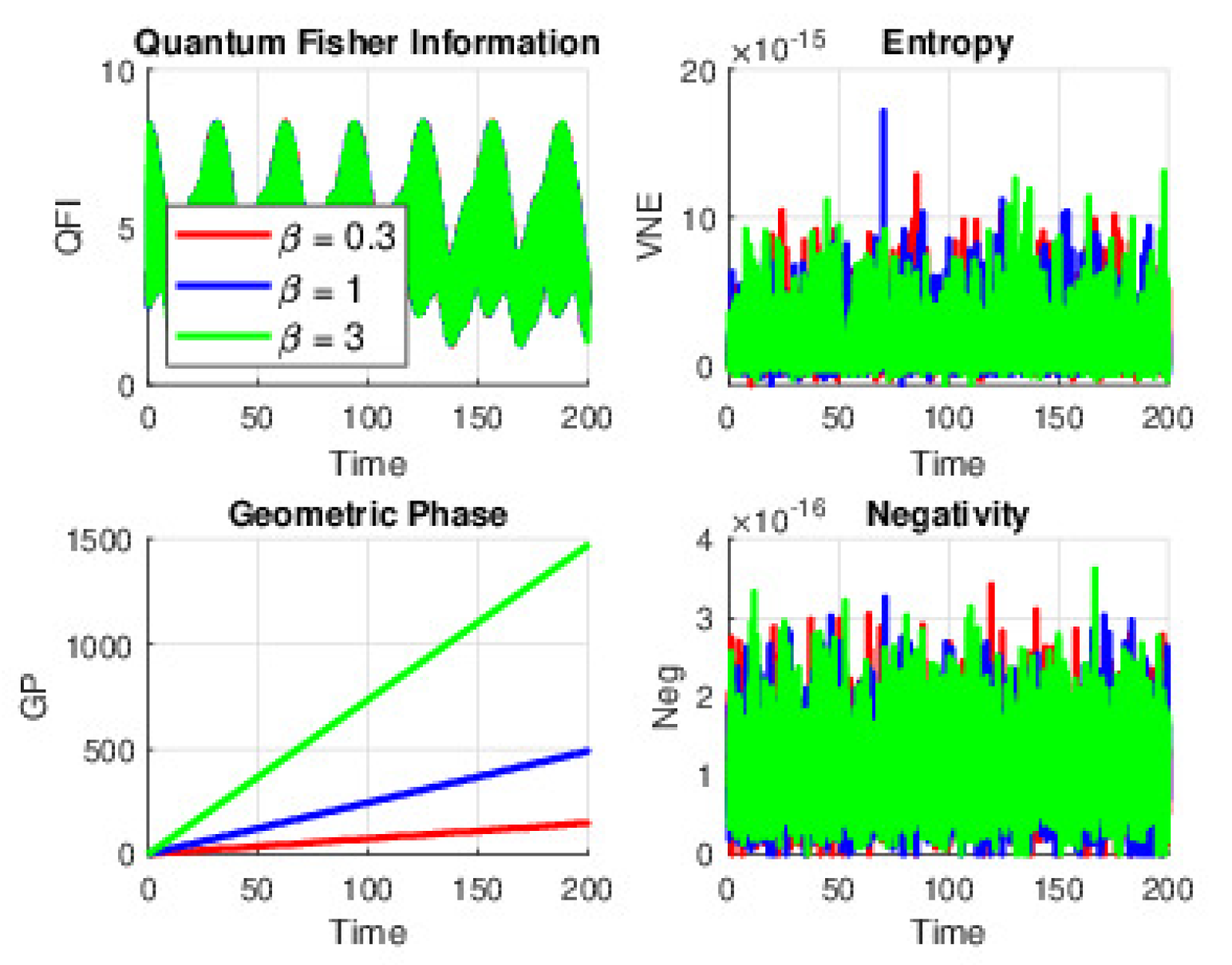

When both detuning and a nonzero initial phase () are present (without atomic motion), the system starts from a complex superposition that further modifies the energy exchange dynamics. At , the system remains largely off-resonance due to detuning, so the oscillations in the QE measures are moderate, though the extra phase causes slight shifts in their timing. At , the combined effects of detuning and the phase lead to more pronounced, irregular oscillations the QE bursts (evidenced by peaks in Neg and QFI) are sharper and occur at different times than in the case with . At , the intense Stark modulation drives rapid transitions in and out of resonance, resulting in tall, narrow QE peaks and highly volatile behavior in both QFI and VNE, with the GP accumulating rapidly and showing pronounced reversals.

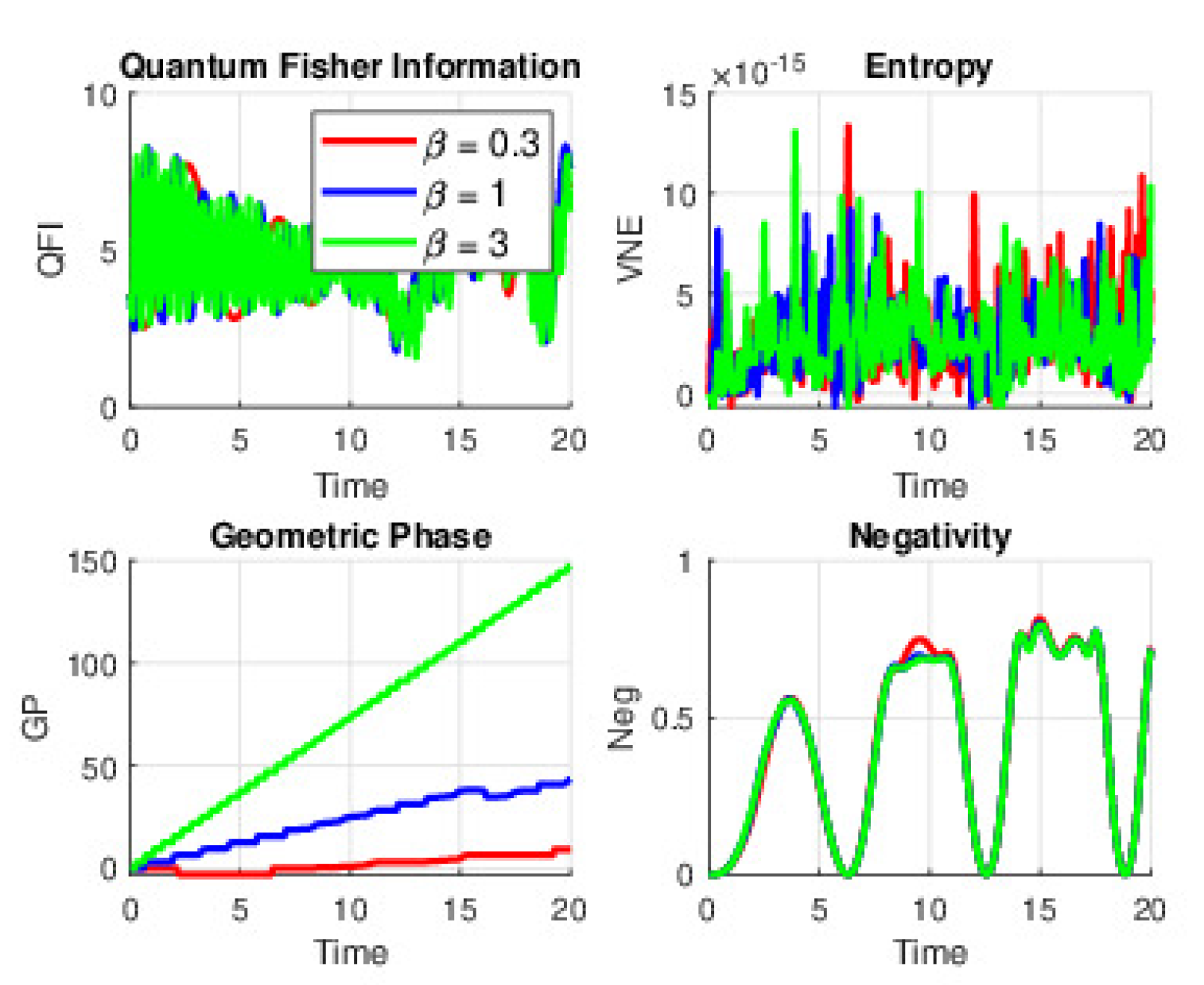

When atomic motion is introduced (with and no detuning), the system’s dynamics are enriched by vibrational sidebands that open up additional pathways for energy exchange. At a low Stark parameter (), these sidebands cause gentle modulations in the standard Jaynes–Cummings oscillations, leading to smooth and moderate fluctuations in QFI, VNE, Neg, and GP. As increases to around 1, the interplay between the SS and vibrational sidebands produces sharper QE disentanglement cycles. This is reflected in more pronounced peaks in Neg and faster oscillations in QFI, while the VNE shows larger swings between near-pure and more mixed states. At high modulation (), the strong Stark effect combined with the vibrational dynamics forces the system repeatedly into and out of resonance, resulting in rapid, high-amplitude oscillations across all quantifiers; the GP, in particular, accumulates in large, discrete jumps.

With atomic motion present and an initial phase of , the dynamics become further complex. At , the added phase subtly shifts the timing and amplitude of the oscillations compared to the case, although the overall behavior remains relatively smooth. When is increased to around 1, the interference introduced by the nonzero phase leads to sharper and more irregular oscillations in the QE measures. Here, peaks in Neg and QFI are either enhanced or diminished at different times, while the VNE shows more pronounced transitions, and the GP reacts with faster, more noticeable shifts. At , the combination of strong Stark modulation, atomic motion, and the additional phase creates extremely rapid bursts of QE. In this regime, the timing and magnitude of the peaks in Neg and QFI are markedly different from those observed with , and the GP exhibits steep, abrupt changes.

When nonzero detuning is combined with atomic motion while maintaining , the system deviates substantially from the standard Jaynes–Cummings behavior. For , the detuning and vibrational sidebands together suppress the excitation exchange, leading to moderate oscillations in QFI and Neg and only gentle fluctuations in VNE. As increases to around 1, the SS occasionally overcomes the off-resonance condition, resulting in stronger and more frequent QE bursts. At , the combined influence of detuning, atomic motion, and a strong Stark shift produces rapid, high-amplitude oscillations: tall, narrow spikes in Neg, significant fluctuations in QFI and VNE, and abrupt, large variations in the GP.

Finally, when detuning, atomic motion, and a nonzero initial phase () are all present, the system exhibits the most complex dynamics. At , the extra phase causes slight temporal and amplitude shifts in the oscillations of theQE measures compared to the case, though the system remains largely off-resonance. As increases to around 1, the interplay among detuning, vibrational sidebands, and the additional phase produces sharper and more pronounced QE bursts, with significant variations in QFI, VNE, and Neg, and the GP responds with more rapid and complex phase accumulation. At , the combined effects lead to extremely rapid and high-amplitude oscillations, characterized by very tall, narrow peaks in Neg and highly volatile behavior in all other measures. The GP, in particular, shows steep increments and may even reverse sign within short time intervals, highlighting the rich interference patterns present in this regime.

Each figure illustrates how varying , the initial phase, detuning, and atomic motion reshapes the QE dynamics in a quantifiable manner, providing a comprehensive view of the sensitive interplay among these parameters in atom field interactions.

5. Relation with Previous Studies

The findings of this study build upon and extend foundational work in quantum optics and quantum information science, particularly concerning the modulation of QE and coherence through the SS and detuning. Previous research has demonstrated that the SE significantly influences quantum coherence and non-classical correlations in atomic systems. For instance, Kim et al. studied the optical SS in quantum dots and highlighted its role in tuning excitonic states for entangled photon generation [

65]. Similarly, Kaplan and Alford analyzed the impact of dynamic SS in multi-level atomic systems, showcasing their utility in precise control of quantum states [

66]. Research by Haroche et al. on cavity quantum electrodynamics further underscored the significance of Stark shifts in enhancing atom-field interactions and generating non-classical correlations [

67]. Additionally, recent studies by Gerrits et al. demonstrated the practical applications of the optical SS in solid-state quantum photonics, emphasizing its relevance in generating high-fidelity entangled photons [

68]. By incorporating a time-dependent SS into a three-level atomic system, this study introduces dynamic modulation capabilities that enhance quantum correlations. The work advances the understanding of how external fields, detuning, and phase modulation influence quantum properties, providing valuable insights for developing tunable quantum technologies.

6. Experimental Realization of the Model

Experimental realization of the proposed model could be achieved using a combination of advanced cavity quantum electrodynamics (QED) setups and precision optical techniques. Recent developments in ultrafast laser systems provide the capability to implement dynamic Stark shifts in multi-level atomic systems by applying tailored electric fields [

69]. For instance, controlled interactions between single-mode quantized electromagnetic fields and three-level atoms can be achieved using high-finesse optical cavities, as demonstrated in the work of Walther et al. [

70]. Furthermore, the use of trapped neutral atoms or ions allows precise control of atomic motion and phase modulation through optical lattices or radiofrequency fields, as reported by Blatt and Wineland [

71]. Coherent state preparation and manipulation of detuning parameters can be realized using programmable lasers with high spectral resolution, enabling experimental validation of the time-dependent SE’s influence on quantum observables such as QE and coherence [

72]. Integration of phase gates and controlled detuning has been explored in quantum photonics platforms, where waveguide-based systems enable robust phase manipulation, as shown by O’Brien et al [

73]. These advancements provide a feasible pathway for experimentally realizing and verifying the dynamics predicted in the study.

7. Conclusions

In summary, our investigation demonstrates that even minor adjustments to external parameters can lead to profound changes in the atom–field interaction. When the SS is minimal, the system behaves very similarly to the traditional resonant JCM, with smooth, predictable energy exchanges and gentle oscillations in QE. However, as the Stark parameter increases, the system is driven more forcefully in and out of resonance, resulting in rapid and pronounced bursts of quantum QE. Furthermore, the introduction of a small nonzero initial phase, such as , modifies these interactions by altering the interference pattern between the atom and the field. This additional phase not only shifts the timing of the QE peaks but also adjusts their amplitude, underscoring the sensitive dependence of the system’s dynamics on the initial conditions. The presence of detuning and atomic motion further complicates the picture by introducing off-resonant effects and vibrational sidebands, which add layers of complexity to the energy exchange and phase evolution. Overall, the study reveals that the interplay of the Stark shift, initial phase, detuning, and atomic motion is critical in shaping the quantum behavior of the system. These findings provide important insights into how one can fine-tune quantum interactions to control QE and coherence, which is vital for advancing quantum technologies.

References

- G. Vidal and R. F. Werner, “Computable measure ofQE,” Phys. Rev. A 65, 032314 (2002).

- A. Peres, “Separability Criterion for Density Matrices,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 1413 (1996).

- M. B. Plenio, “Logarithmic Neg: A FullQE Monotone That is not Convex,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 090503 (2005).

- R. Horodecki et al., “QuantumQE,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 865 (2009).

- E. T. Jaynes and F. W. Cummings, “Comparison of quantum and semiclassical radiation theories with application to the beam maser,” Proc. IEEE 51, 89 (1963).

- B. W. Shore and P. L. Knight, “The Jaynes–Cummings model,” J. Mod. Opt. 40, 1195 (1993).

- M. O. Scully and M. S. Zubairy, “Quantum Optics,” Cambridge University Press (1997).

- H. J. Carmichael, “Statistical Methods in Quantum Optics 1,” Springer (1999).

- J. S. Bell, “On the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox,” Physics 1, 195 (1964).

- A. Aspect, P. Grangier, and G. Roger, “Experimental Tests of Realistic Local Theories via Bell’s Theorem,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 47, 460 (1981).

- N. Brunner, D. Cavalcanti, S. Pironio, V. Scarani, and S. Wehner, “Bell nonlocality,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 419 (2014).

- H. J. Kimble, “The quantum internet,” Nature 453, 1023 (2008).

- C. H. Bennett and S. J. Wiesner, “Communication via one- and two-particle operators on Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen states,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2881 (1992).

- S. H. Autler and C. H. Townes, “Stark Effect in Rapidly Varying Fields,” Phys. Rev. 100, 703 (1955).

- J. H. Shirley, “Solution of the Schrödinger Equation with a Hamiltonian Periodic in Time,” Phys. Rev. 138, B979 (1965).

- C. Cohen-Tannoudji, “Atom-Photon Interactions: Basic Processes and Applications,” Wiley (1998).

- Z. Ficek and R. Tanas, “Entangled states and collective nonclassical effects in two-atom systems,” Phys. Rep. 372, 369 (2002).

- S. L. Braunstein and C. M. Caves, “Statistical distance and the geometry of quantum states,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 3439 (1994).

- M. G. A. Paris, “Quantum Estimation for Quantum Technology,” Int. J. Quant. Inf. 7, 125 (2009).

- L. Pezzé and A. Smerzi, “Entanglement, Nonlinear Dynamics, and the Heisenberg Limit,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 100401 (2009).

- J. von Neumann, “Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics,” Princeton University Press (1955).

- M. A. Nielsen and I. L. Chuang, “Quantum Computation and Quantum Information,” Cambridge University Press (2000).

- M. V. Berry, “Quantal Phase Factors Accompanying Adiabatic Changes,” Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 392, 45 (1984).

- Y. Aharonov and J. Anandan, “Phase Change during a Cyclic Quantum Evolution,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 1593 (1987).

- J. Samuel and R. Bhandari, “General Setting for Berry’s Phase,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 2339 (1988).

- N. Mukunda and R. Simon, “Quantum Kinematic Approach to the Geometric Phase. I. General Formalism,” Ann. Phys. 228, 205 (1993).

- S. J. D. Phoenix and P. L. Knight, “Establishing the presence of quantum coherence in optical systems,” J. Mod. Opt. 40, 979 (1993).

- J. Gea-Banacloche, “Some implications of the quantum nature of laser fields for quantum computations,” Phys. Rev. A 65, 022308 (2002).

- A. Beige et al., “Quantum computing using dissipation to remain in a decoherence-free subspace,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 1762 (2000).

- W. K. Wootters, “Entanglement of Formation of an Arbitrary State of Two Qubits,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 2245 (1998).

- R. Horodecki et al., “Mixed-StateQE and Distillation: Is There a ’Bound’QE in Nature?” Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 5239 (1998).

- C. H. Bennett et al., “Mixed-stateQE and quantum error correction,” Phys. Rev. A 54, 3824 (1996).

- D. M. Meekhof et al., “Generation of nonclassical motional states of a trapped atom,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 1796 (1996).

- D. Leibfried, R. Blatt, C. Monroe, and D. J. Wineland, “Quantum dynamics of single trapped ions,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 281 (2003).

- J. M. Raimond, M. Brune, and S. Haroche, “Manipulating quantumQE with atoms and photons in a cavity,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 565 (2001).

- H. Walther et al., “Cavity quantum electrodynamics,” Rep. Prog. Phys. 69, 1325 (2006).

- B. W. Shore, “The Theory of Coherent Atomic Excitation,” Wiley (1990).

- L. Allen and J. H. Eberly, “Optical Resonance and Two-Level Atoms,” Dover Publications (1987).

- Z. Ficek and S. Swain, “Quantum Interference and Coherence: Theory and Experiments,” Springer (2005).

- G. S. Agarwal, “Quantum Optics,” Cambridge University Press (2013).

- H. P. Yuen and J. H. Shapiro, “Optical Communication with Two-Photon Coherent States—Part III: Quantum Measurements Realizable with Photoemissive Detectors,” IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 26, 78 (1980).

- D. F. Walls and G. J. Milburn, “Quantum Optics,” Springer (2008).

- M. O. Scully, B.-G. Englert, and J. Schwinger, “Quantum Optical Tests of Complementarity,” Nature 351, 111 (1991).

- H. M. Wiseman and G. J. Milburn, “Quantum Measurement and Control,” Cambridge University Press (2009).

- F. T. Hioe and J. H. Eberly, “N-level coherence vector and higher conservation laws in quantum optics,” Phys. Rev. A 23, 136 (1981).

- D. F. Walls, “Squeezed states of light,” Nature 306, 141 (1983).

- C. Monroe et al., “Resolved-sideband Raman Cooling of a Bound Atom to the 3D Zero-Point Energy,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 4011 (1995).

- J. I. Cirac and P. Zoller, “Quantum computations with cold trapped ions,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4091 (1995).

- D. Leibfried et al., “Experimental demonstration of a robust, high-fidelity geometric two ion-qubit phase gate,” Nature 422, 412 (2003).

- C. F. Roos et al., “Quantum state engineering on an optical transition and decoherence in a Paul trap,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 4713 (1999).

- D. J. Wineland et al., “Experimental issues in coherent quantum-state manipulation of trapped atomic ions,” J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 103, 259 (1998).

- F. Schmidt-Kaler et al., “Realization of the Cirac–Zoller controlled-NOT quantum gate,” Nature 422, 408 (2003).

- P. O. Schmidt et al., “Spectroscopy Using Quantum Logic,” Science 309, 749 (2005).

- D. Kielpinski, C. Monroe, and D. J. Wineland, “Architecture for a large-scale ion-trap quantum computer,” Nature 417, 709 (2002).

- Anwar, S. J., Ramzan, M., Usman, M., & Khan, M. K. (2019). Stark and Kerr Effects on the Dynamics of Moving N-Level Atomic System. Journal of Quantum Information Science, 9(1), 24-41. (researchgate.net).

- Anwar, S. J., Ramzan, M., Usman, M., & Khan, M. K. (2019). QE Dynamics of Three and Four Level Atomic System under SE and Kerr-Like Medium. Quantum Reports, 1(1), 23-36. (researchgate.net).

- Anwar, S. J., Ramzan, M., Usman, M., & Khan, M. K. (2021). QFIof Two-Level Atomic System under the Influence of Thermal Field, Intrinsic Decoherence, SE and Kerr-Like Medium. Journal of Quantum Information Science, 11(1), 24-41. (mdpi.com).

- Anwar, S. J., Ramzan, M., & Khan, M. K. (2019). Effect of Stark- and Kerr-like medium on the QE dynamics of two three-level atomic systems. Quantum Information Processing, 18(6), 1-15. (researchgate.net).

- S. Abdel-Khalek, QFIfor moving three-level atom, Quantum Inf. Process. 12, 3761 (2013).

- Helstrom, C. W. (1976). Quantum Detection and Estimation Theory. Academic Press.

- Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. (2010). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press.

- Berry, M. V. (1984). Quantal Phase Factors Accompanying Adiabatic Changes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 392(1802), 45–57.

- A. Peres, “Separability Criterion for Density Matrices,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 1413–1415 (1996).

- G. Vidal and R. F. Werner, “Computable measure ofQE,” Phys. Rev. A 65, 032314 (2002).

- Kim, D., Carter, S. G., Greilich, A., Bracker, A. S., & Gammon, D. (2011). Ultrafast optical control of QE between two quantum-dot spins. Nature Physics, 7(3), 223–229.

- Kaplan, J., & Alford, M. (2015). Dynamic Stark shifts in multi-level atomic systems. Physical Review A, 91(5), 052103.

- Haroche, S., & Raimond, J. M. (2006). Exploring the Quantum: Atoms, Cavities, and Photons. Oxford University Press.

- Gerrits, T., Marsili, F., Verma, V. B., Shalm, L. K., & Nam, S. W. (2016). Generation of entangled photon pairs using a quantum dot under Stark modulation. Nature Communications, 7, 12661.

- Shapiro, M., & Brumer, P. (2003). Principles of the Quantum Control of Molecular Processes. Wiley-Interscience.

- Walther, H., Varcoe, B. T. H., Englert, B.-G., & Becker, T. (2006). Cavity quantum electrodynamics. Reports on Progress in Physics, 69(5), 1325–1382.

- Blatt, R., & Wineland, D. (2008). Entangled states of trapped atomic ions. Nature, 453(7198), 1008–1015.

- Specht, H. P., Nölleke, C., Reiserer, A., Uphoff, M., Figueroa, E., Ritter, S., & Rempe, G. (2011). A single-atom quantum memory. Nature, 473(7346), 190–193.

- O’Brien, J. L., Furusawa, A., & Vučković, J. (2009). Photonic quantum technologies. Nature Photonics, 3(12), 687–695.

Figure 1.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is neglected.

Figure 1.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is neglected.

Figure 2.

Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is neglected.

Figure 2.

Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is neglected.

Figure 3.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and NeG at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is neglected.

Figure 3.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and NeG at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is neglected.

Figure 4.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and NeG at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is neglected.

Figure 4.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and NeG at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is neglected.

Figure 5.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is present.

Figure 5.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is present.

Figure 6.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is present.

Figure 6.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is present.

Figure 7.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is present.

Figure 7.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is present.

Figure 8.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is present.

Figure 8.

(Color online) QE dynamics under the time-dependent SE with and (Coherent state parameter) for QFI, VNE, GP, and Neg at Stark field strengths . Atomic motion is present.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).