3.1. QFI at Zero Temperature

In this section, we utilize the Quantum Fisher Information (QFI) given in Eq. (

2) to explore the quantum phase transition occurring at zero temperature, specifically within the limit where

. For clarity, let’s denote the eigenstates of

as

and the eigenstates of

as

.

To commence our investigation, we calculate the QFI linked to the normal phase of the Hamiltonian (

1) in the range of

. We employ a strategy that involves seeking a unitary Schrieffer-Wolff transformation [

30]. This transformation, given by

, decouples the two spin subspaces (namely,

and

) in the transformed Hamiltonian

. As a result, we derive the effective low-energy form of the Hamiltonian (

1) in its normal phase:

The eigenvalues

and eigenstates

of this effective Hamiltonian

can be determined analytically. The eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian (

5) are given by:

where

. The corresponding eigenstates, related to Eq. (

6), can be represented as

. Here,

is the squeezing operator, with

as the squeezing parameter.

Note that the eigenvalues

in Eq. (

6) are real only when the atom-field coupling

y is less than or equal to the critical value

, and they vanish precisely at this critical point. For the parameter range where

, we can substitute the derived

and the corresponding eigenstates

into Eq. (

2). This allows us to obtain the analytical expression for Quantum Fisher Information (QFI), given by:

From Eq. (

7), it is evident that QFI diverges as

y approaches

, indicating a quantum phase transition. Importantly, Eq. (

2) is not applicable for

.

Moving on, we explore the QFI associated with the superradiant phase of the model Hamiltonian (

1) for

. In this phase, the number of photons within the cavity field becomes proportional to

N. To capture the essential low-energy physics, we apply a similarity transformation

to the Hamiltonian (

1). Here,

is the displacement operator, and

represents a rotation transformation [

19,

30]. By choosing

and

, we obtain the effective low-energy form of the Hamiltonian (

1) in the superradiant phase:

where

,

, and

. Equation (

8) bears structural similarity to the original Hamiltonian (

1), but with rescaled parameters

and

. This allows us to routinely derive the eigenstates of Eq. (

8) as

, with

. The corresponding eigenvalue is given by:

For the standard parameters where

,

, and

, the eigenvalue expressed in Eq. (

9) corresponds to that of the Hamiltonian (

8) in the superradiant phase. This eigenvalue is real only if

y surpasses the critical value

. Based on Eq. (

2), we can derive the analytical expression for Quantum Fisher Information (QFI) in the super-radiant phase as follows:

It’s worth noting that in the regime where

, the advanced corrections in Eqs. (

5) and (

8) become negligible [

30]. Consequently,

from Eq. (

5) and

from Eq. (

8) emerge as the precise low-energy effective Hamiltonians for the normal phase (

) and the superradiant phase (

) respectively. This implies that Equations (

7) and (

10) precisely represent the QFI of the Hamiltonian (

1) in its respective phases.

Leveraging Equations (

7) and (

10), we can devise a method to detect the quantum phase transition inherent in the Hamiltonian (

1). Let’s explore some pivotal characteristics of this transition and its relationship to QFI as defined in Eq. (

2). Firstly, the rescaled cavity photon count, denoted as

, serves as an order parameter. It remains zero when

and becomes finite, with a value of

, when

. Secondly, the rescaled ground state energy, computed as

, demonstrates continuity at the critical point

. However, a discontinuity arises in its second derivative, highlighting the second-order nature of the quantum phase transition. Thirdly, as we approach the critical point, the excitation energies in both phases vanish, proportional to

and

as indicated by Eqs. (

6) and (

9). Consequently, the QFI (

2) diverges in a manner proportional to

, aligning with the findings of Eqs. (

7) and (

10). This divergence is a hallmark of critical behavior associated with symmetry breaking, where the system’s response to external perturbations becomes singular. In

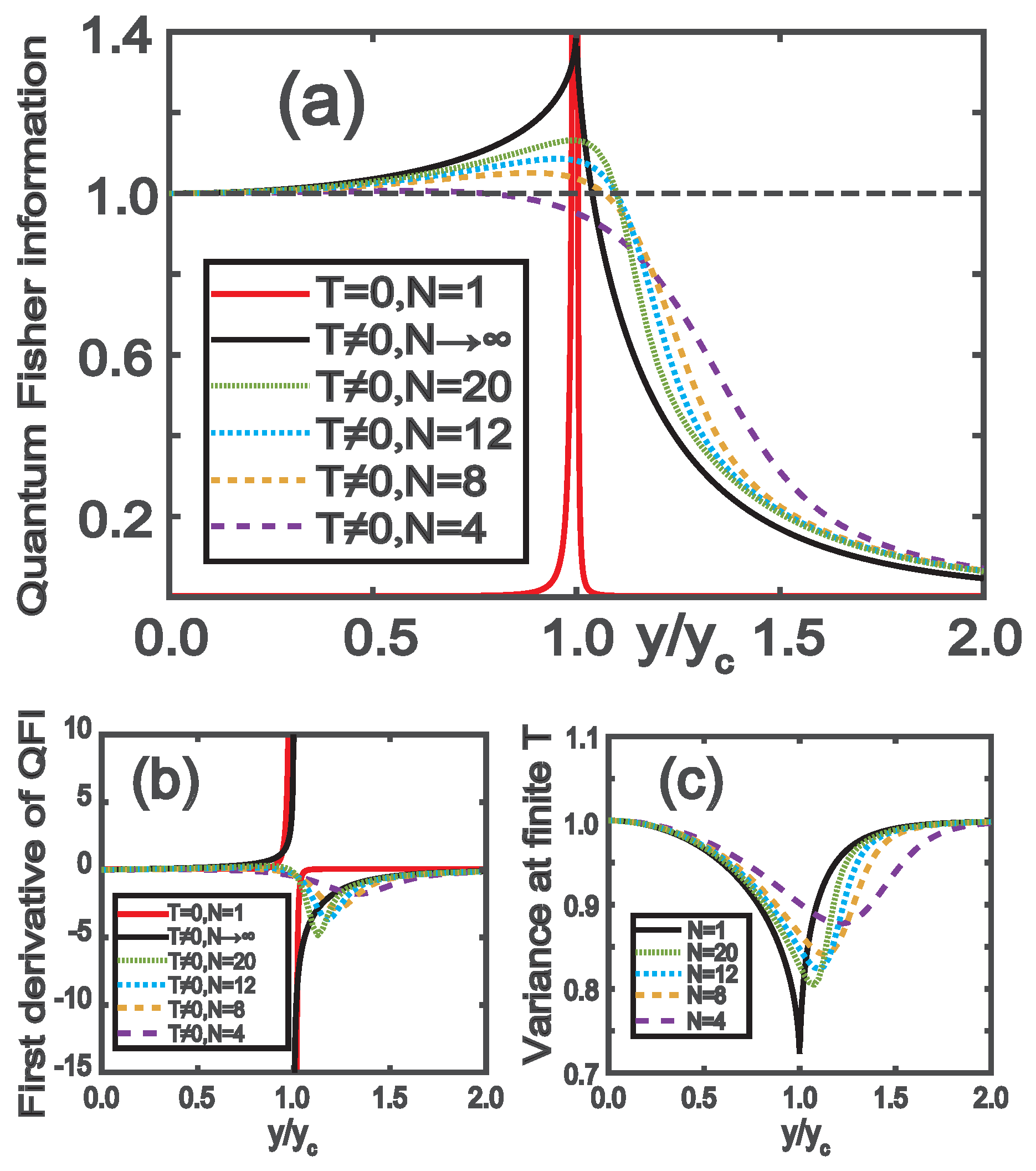

Figure 1 (a) and (b), we illustrate the outcomes for QFI and its first derivative based on Equations (

7) and (

10). The red solid curves prominently showcase the divergence of QFI at the critical point

, a direct consequence of the narrowing energy gap above the ground state as expressed in Eq. (

4). In contrast, both QFI and its first derivative rapidly diminish to zero when

y moves away from

. This trend can be understood through Eq. (

2). When the system is not in the vicinity of the quantum phase transition’s critical point, it becomes highly resistant to external perturbations represented by

. As a result,

approaches unity, indicating a negligible QFI according to Eq. (

2). Finally, it’s worth mentioning that the QFI depicted in

Figure 1 (a) and its first derivative in

Figure 1 (b) can be empirically determined by analyzing the squared Hellinger distance between probability distributions, as outlined in Ref. [

28].

3.2. The QFI at Finite Temperatures

In

Section 3.1, we analytically derived the QFI for the Hamiltonian (

1) at zero temperature, as seen in Eqs. (

7) and (

10). Now, in this

Section 3.2, our intention is to explore the influence of finite temperature on the QFI, utilizing Eq. (

3), particularly in the thermodynamic limit where

N and

V tend to infinity while maintaining a constant atom density

.

Drawing from the work presented in Ref. [

19], we adopt the Holstein-Primakoff transformation, specifically,

and

, to recast the atomic freedoms in terms of the bosonic operator

. Through this lens, the Hamiltonian (

1) can be reframed as:

This reformulated Hamiltonian (

11) elegantly describes the dynamics between two intertwined harmonic oscillators, denoted by the operators

and

respectively.

Shifting our focus to the system’s normal phase, we introduce the position and momentum operators defined as

and

. Through this lens, Hamiltonian (

11) transforms into:

Here,

corresponds to

and

equals

. In contrast to the original Dicke-model Hamiltonian explored in Ref. [

29], which emphasized the coupling of coordinates with coordinates, Eq. (

12) showcases a coupling between coordinates and momenta (evident in the penultimate term of Eq. (

12)). This distinction necessitates a fresh approach in analyzing the Hamiltonian, distinct from the methodologies employed in Ref. [

29].

In order to compute the QFI based on Eq. (

3) in relation to the normal phase, obtaining the density matrix of

from Eq. (

3) in the energy basis is crucial. We achieve this by following a three-step process: (i) Firstly, we decouple the two harmonic oscillators in Hamiltonian (

12) using Bogoliubov’s transformations. The excitation energies

(

) are determined as

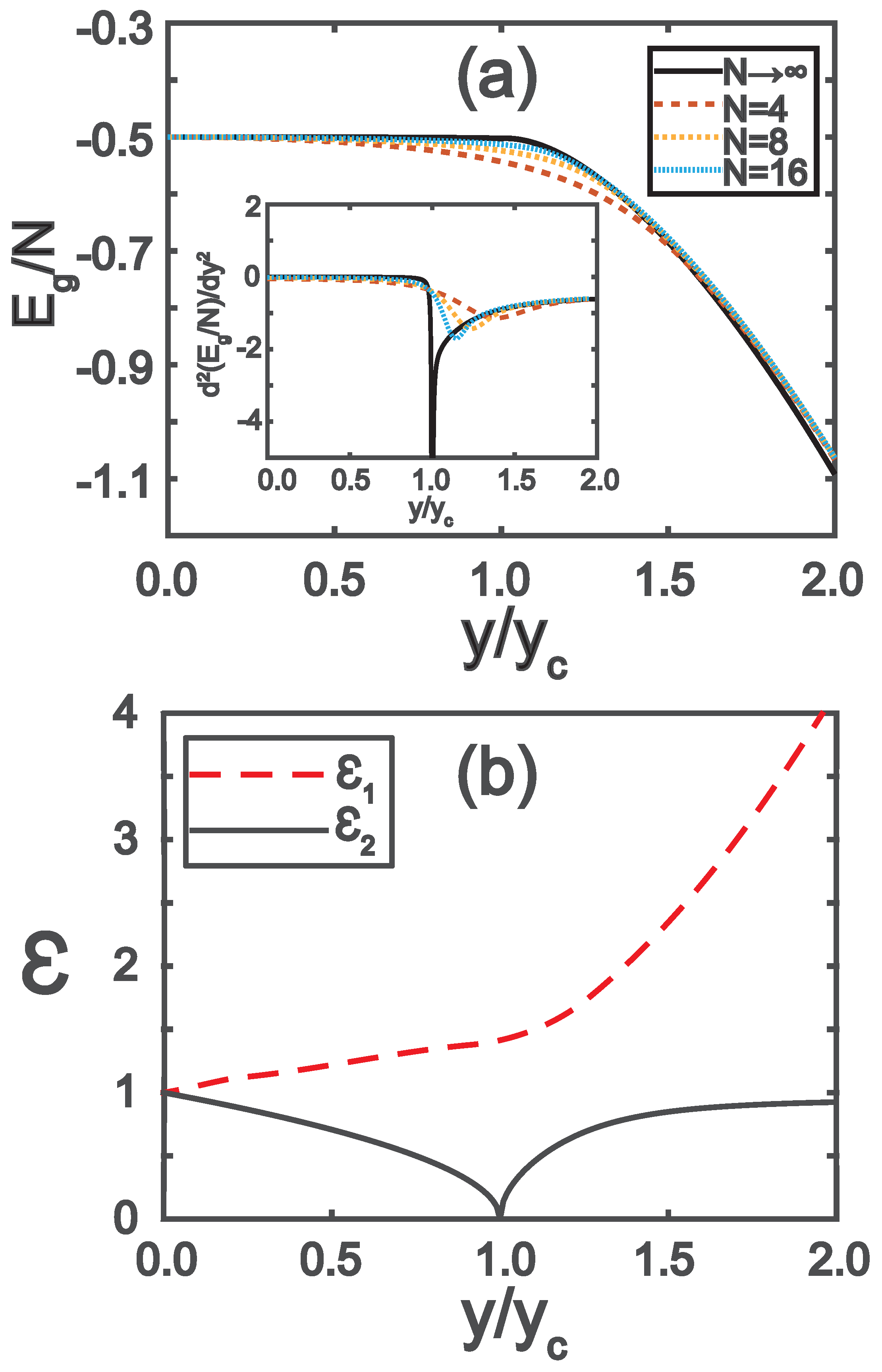

. With this knowledge, we can plot the ground state energy and excitation energies, represented by solid black curves in

Figure 2 (a) and (b) respectively. It’s worth noting that the ground state energy remains continuous across the critical point, whereas the second derivative of the ground state energy diverges, serving as an indicator of the superradiant quantum phase transition. (ii) Secondly, we obtain the reduced density matrix of the atoms in spatial coordinates as follows:

where

,

,

,

, and

. (iii) Finally, we derive the eigenvalues of the population

corresponding to the energy eigenstate

in Eq. (

3) as

.

Subsequently, one can calculate the squeezing parameter of the atoms, given by

. The detailed variances are expressed as:

Consequently, the squeezing parameter is:

depicted by the solid black curves in

Figure 1 (c). As anticipated,

diverges at the critical point of the quantum phase transition.

Now we are ready to calculate the QFI associated with the normal phase. If we choose

as the phase-shift generator, we can obtain the corresponding QFI as follows

For a different choice

, we can obtain the corresponding QFI

. Obviously, it is better to choose

as the phase-shift generator due to

, and the corresponding QFI is given by Eq. (

16), which has been plotted into the solid black curves in

Figure 1 (a) and (b). As is expected, QFI is divergent across the critical point of the quantum phase transition.

We proceed to compute the Quantum Fisher Information (QFI) in the superradiant phase. In this phase, considering the population inversion that occurs across a multitude of atoms, one can decompose the operators

and

from Hamiltonian (

11) as follows:

Here,

and

represent the mean-field components, while

and

denote the quantum fluctuations for each subsystem. For clarity, we’ll adopt the notation

and

, noting that both choices of shifts yield consistent results. There exist a pair of real values for

and

that eliminate the linear terms in the Hamiltonian (

11) within the displaced phase space. These values are determined by:

The trivial solution, where

, corresponds to the normal phase. For the non-trivial case where

and

, a physically meaningful solution arises:

This solution exists within the range

if and only if

y exceeds

, defined as

. By approximating the Hamiltonian (

11) to the second order and substituting Eq. (

19) into it, we obtain the effective Hamiltonian in the superradiant phase at finite temperature:

where the coefficients and ground state energy

are defined as follows:

,

,

,

, and

Utilizing Eq. (

21), we have plotted the ground state energy and its second derivative, depicted as solid black curves in

Figure 2 (a). As shown in the inset of

Figure 2 (a), the second derivative of the ground state energy diverges at the critical point of

, as expected.

Similar to the treatment in the normal phase, we typically introduce operators

and

, where

and

. Then, by defining

and

, we rewrite Hamiltonian (

20) as follows:

Equation (

22) has the same structure as Eq. (

12) with the rescaled frequencies and coupling coefficient,

,

and

. Therefore, by employing the same procedure used to derive

, we find the eigenvalues of the density operator as

, where

,

and

with

,

and

. We proceed to calculate the analytical expression of the squeezing parameter in the superradiant phase at the finite temperature

which is routine to be plotted into

Figure 1 (c). Again, the squeezing parameter is divergent as

as a signature of the superradiant quantum phase transition.

Lastly, we compute the Quantum Fisher Information (QFI) of atoms in the superradiant phase at finite temperature. Choosing

as the phase-shift generator yields the corresponding QFI:

In

Figure 1 (a), the black solid curves represent the results obtained from Equations (

16) and (

24). Evidently, the QFI diverges at the critical point

, indicating a significant change in the quantum state of the system.

3.3. Probing Quantum Phase Transition of a Quantum-Gas Cavity QED by Quantum Fisher Information

In

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2, we analytically derived the quantum Fisher information (QFI) for the Hamiltonian in Eq. (

1)—at zero temperature [Eqs. (

7), (

10)] and finite temperature in the thermodynamic limit [Eqs. (

16), (

24)]. In

Section 3.3, we extend this to finite atom numbers by numerically computing QFI via Eq. (

3) and analyzing its use for detecting quantum phase transitions (QPTs) in quantum-gas cavity QED.

To compute QFI numerically, we first find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the density operator

. Using the method of Ref. [

29], we solve for the ground state

of the finite-

N Hamiltonian (Eq.

1), where

N is the cutoff photon number. We minimize Eq. (

1) to obtain

, then trace out the bosonic field to get the atomic density operator:

. With

, we compute its eigenvalues/eigenvectors for

and substitute into Eq. (

3). We plot QFI (

Figure 1(a,b)) and ground-state energy (

Figure 2(a)) from these numerics.

Utilizing the data presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, we are poised to devise a methodology for detecting quantum phase transitions in the Hamiltonian of Eq. (

1) through QFI. Let’s highlight some key aspects of the quantum phase transition and QFI as defined in Eq. (

2). Firstly, the rescaled cavity photon number, denoted as

, serves as an order parameter. It vanishes for

and becomes finite with

for

. This order parameter directly reflects the symmetry breaking. Secondly, the rescaled ground state energy approaches a limit as

, indicating continuity at the critical point

, as illustrated in

Figure 2(a). However, the second derivative of the ground state energy exhibits a discontinuity, as evidenced by the inset curves of

Figure 2(a), revealing the second-order nature of the quantum phase transition. Thirdly, in proximity to the critical point, as demonstrated in Eqs. (

7) and (

10), the excitation energies in both the normal and superradiant phases tend to zero, proportional to

as shown in

Figure 2(b). Consequently, the QFI in Eq. (

2) is expected to diverge as

, which is corroborated by Eqs. (

7) and (

10).

Figure 1(a) is the heart of our QPT detection: it shows QFI for the Eq. (

1) Hamiltonian. Solid red/black curves are thermodynamic-limit (

,

fixed) analytical QFI for zero/finite temperature; dashed curves are numerical QFI for finite

N. As

N grows, numerical QFI converges to the thermodynamic limit—matching our analytics. Most critically, both approaches show QFI **diverging at

**—unambiguous proof of the superradiant quantum phase transition.