Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Hamiltonian Model

3. Discussions and Numerical Outcomes

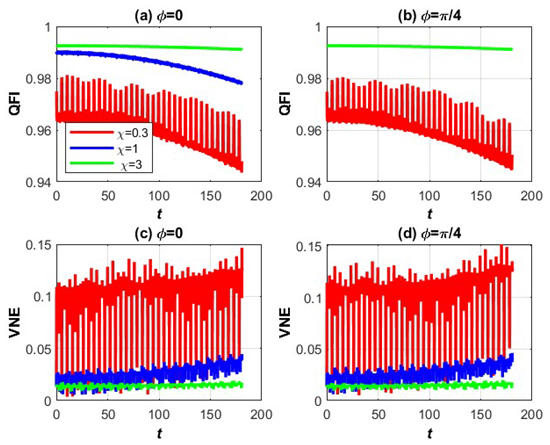

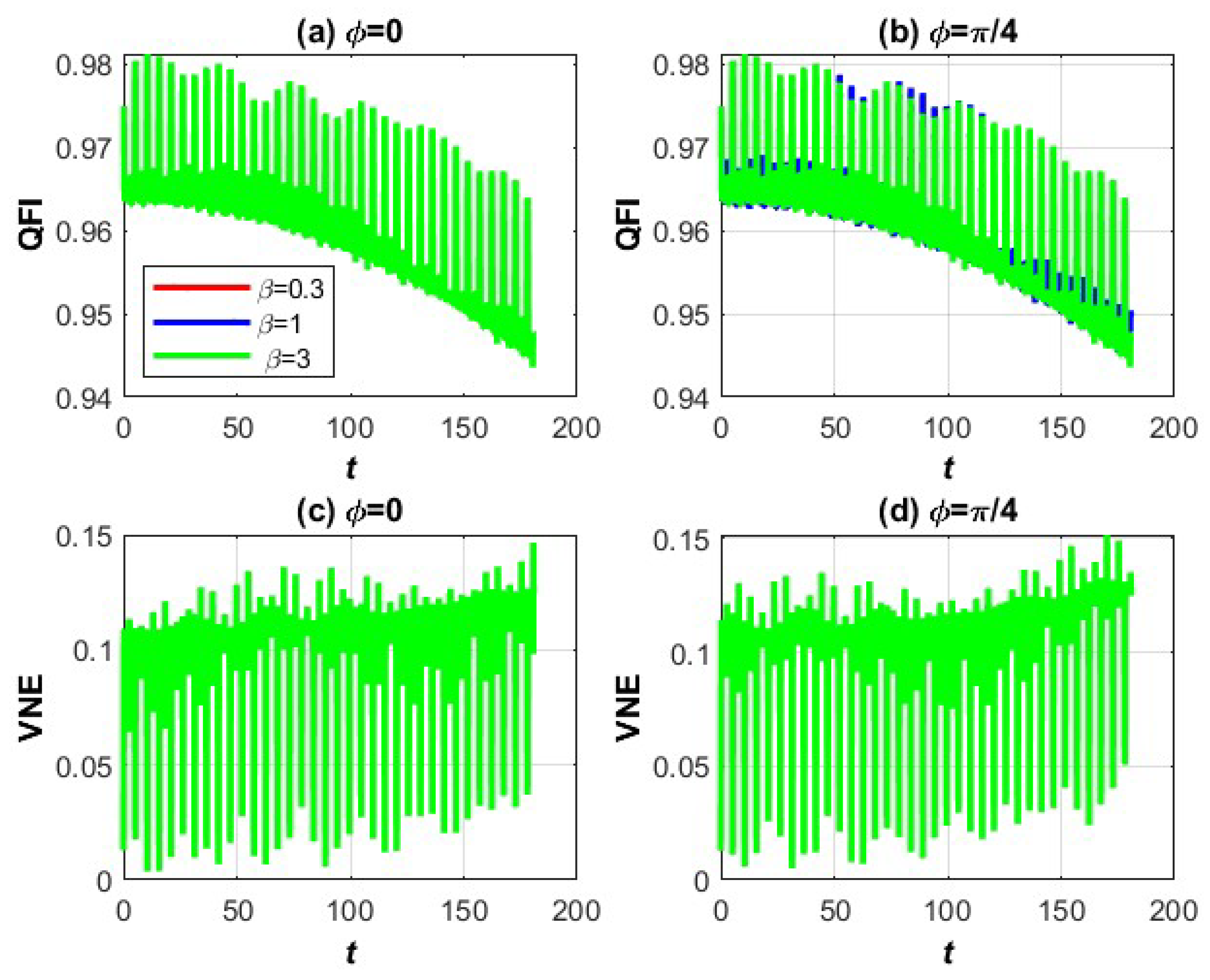

3.1. VNE and QFI of Three-Level Stationary Stark Shifted Atomic Systems Under the Influence of NLKM

3.1.1. Explanation of the Graphs

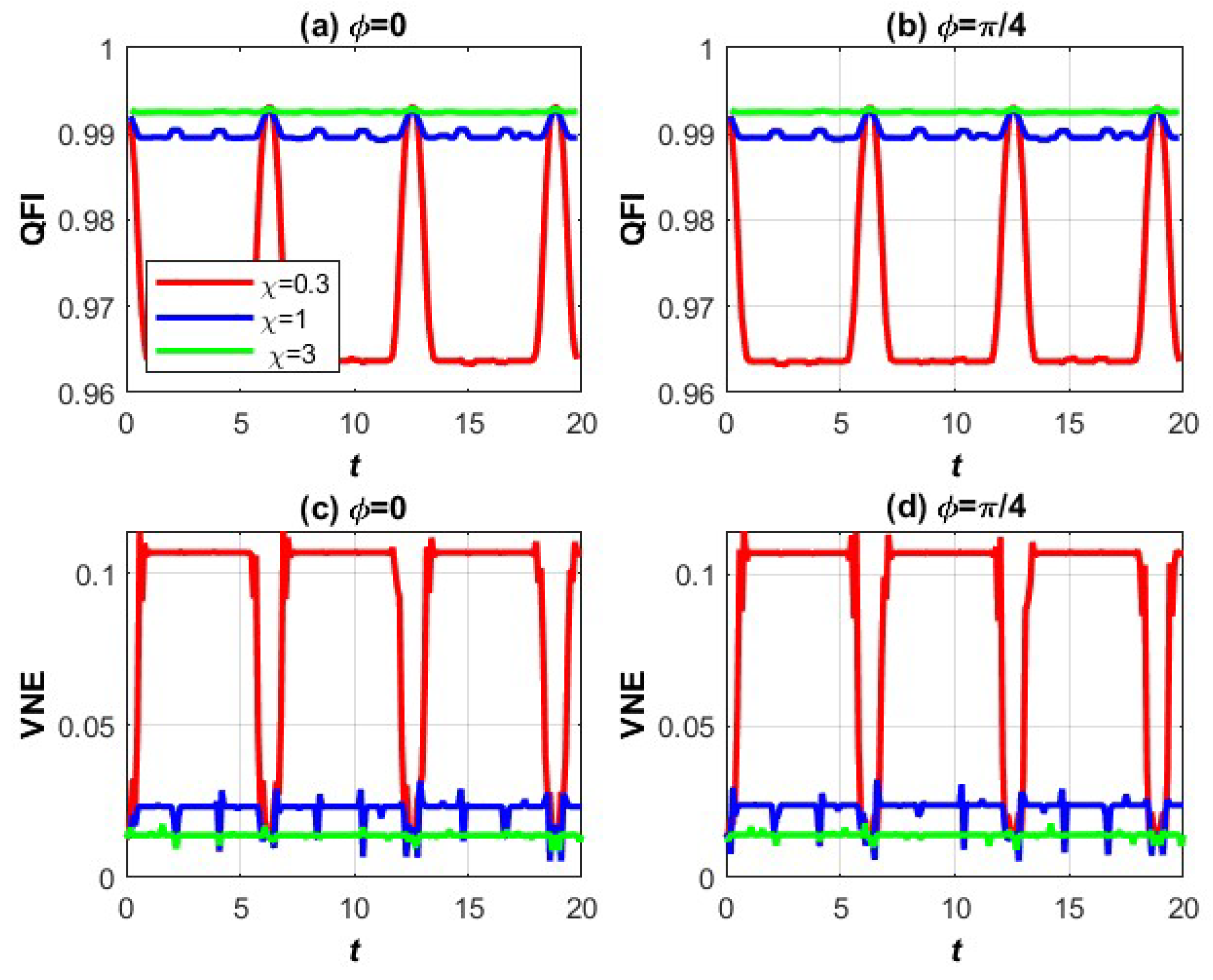

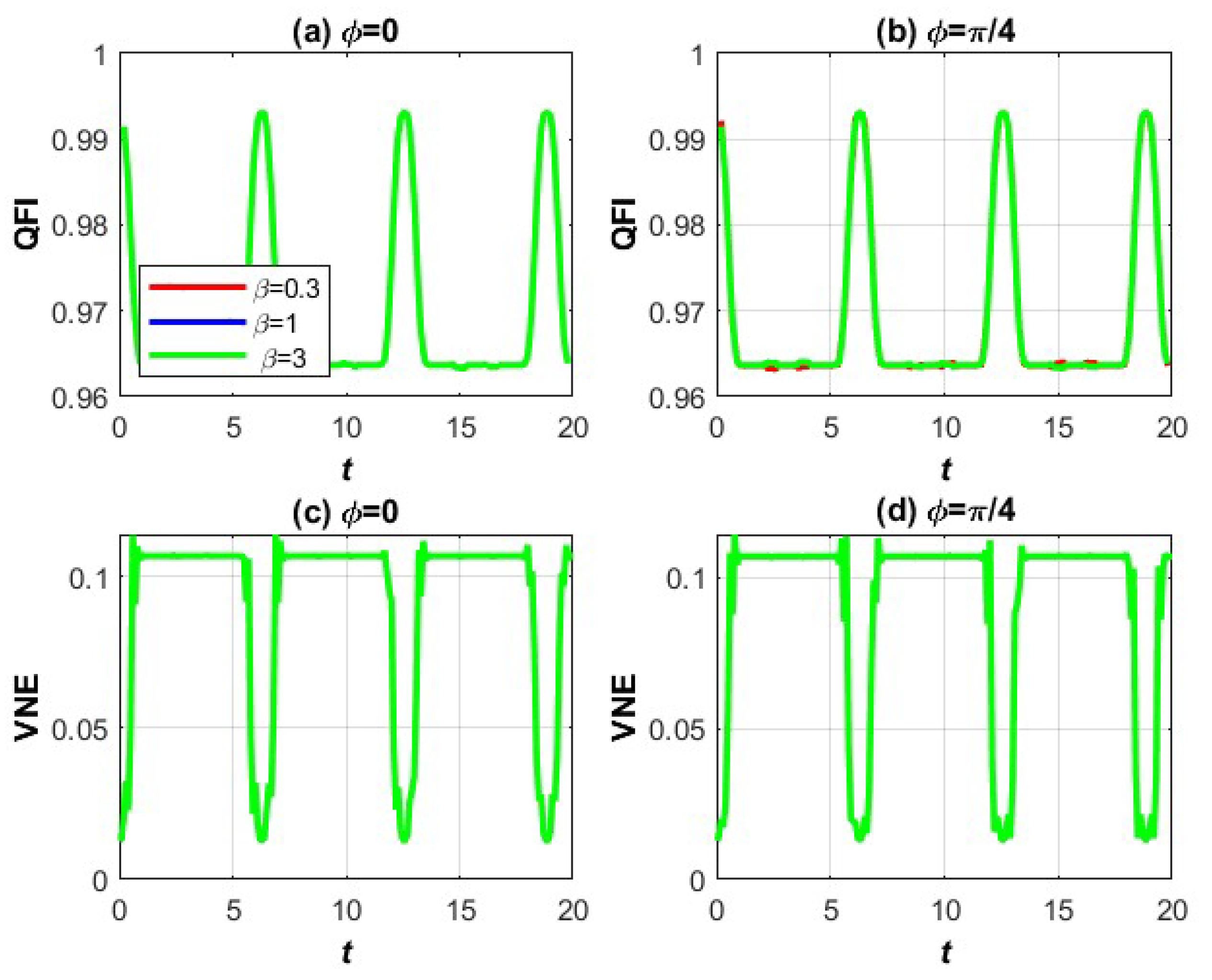

3.2. VNE and QFI of Three-Level Moving Stark Shifted Atomic Systems Under the Influence of NLKM

3.2.1. EXPLANATION OF GRAPHS:

4. Conclusions

References

- Shore, B.W.; Knight, P.L. The jaynes-cummings model. Journal of Modern Optics 1993, 40, 1195–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqannas, H.S.; Abdel-Khalek, S. Nonclassical properties and field entropy squeezing of the dissipative two-photon JCM under Kerr like medium based on dispersive approximation. Optics & Laser Technology 2019, 111, 523–529. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard, R.; Walther, H.; Klein, N. Observation of quantum collapse and revival in a one-atom maser. Physical review letters 1987, 58, 353. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, H-I.; Eberly, J.H. Dynamical theory of an atom with two or three levels interacting with quantized cavity fields. Physics Reports 1985, 118, 239–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lin, D.L. Nonresonant interaction of a three-level atom with cavity fields. I. General formalism and level occupation probabilities. Physical Review A 1987, 36, 5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hafez, A.M.; Obada, A.S.F.; Ahmad, M.M.A. N-level atom and (N- 1) modes generalized models and multiphons. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 1987, 144, 530–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hafez, A.M.; Obada, A.S.F.; Ahmad, M.M.A. N-level atom and (N-1) modes: an exactly solvable model with detuning and multiphotons. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 1987, 20, L359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hafez, A.M.; Abu-Sitta, A.M.M.; Obada, A.S.F. A generalized Jaynes-Cummings model for the N-level atom and (N- 1) modes. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 1989, 156, 689–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.A. Entanglement degree of a three-level atom interacting with pair-coherent states with a nonlinear medium. Laser physics 2001, 11, 871–878. [Google Scholar]

- Obada, A.S.F.; Hanoura, S.A.; Eied, A.A. Entanglement for a general formalism of a three-level atom in a V-configuration interacting nonlinearly with a non-correlated two-mode field. Laser Physics 2013, 23, 055201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Wahab, N.H.; Salah, A. A novel solution procedure for a three-level atom interacting with one-mode cavity field via modified homotopy analysis method. The European Physical Journal Plus 2015, 130, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Wahab, N.H.; Salah, A. The influence of the classical homogenous gravitational field on interaction of a three-level atom with a single mode cavity field. Modern Physics Letters B 2015, 29, 1550175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y. Velocity-selective population and quantum collapse-revival phenomena of the atomic motion for a motion-quantized Raman-coupled Jaynes-Cummings model. Physical Review A 1996, 54, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faghihi, M.J.; Tavassoly, M.K.; Hatami, M. Dynamics of entanglement of a three-level atom in motion interacting with two coupled modes including parametric down conversion. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2014, 407, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zait, R.A.; Abd El-Wahab, N.H. Nonresonant interaction between a three-level atom with a momentum eigenstate and a one-mode cavity field in a Kerr-like medium. Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics 2002, 35, 3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.S.; Abdel-Gawad, H.I. Multi-wave solutions of the (2+ 1)-dimensional Nizhnik-Novikov-Veselov equations with variable coefficients. The European Physical Journal Plus 2015, 130, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, R. Alternating current and superconductivity quantum entanglement of waves replaces nuclear fusion as the power source in stars. Available at SSRN 4556339, (2023).

- Feng, T. , Song, Z.,Wu, T., Lu, X. & Li, L. Quantum entanglement source model pumped by low-power laser diode. In Conference on Infrared, Millimeter, TerahertzWaves and Applications (IMT2022) Vol. 12565 (ed. Feng, T.) 362–370 (SPIE, 2023).

- Sun, W.-Y.; Wang, D.; Fang, B.-L.; Ye, L. Quantum dynamics characteristic and the flow of information for an open quantum system under relativistic motion. Laser Phys. Lett. 2018, 15, 035203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goradia, S.G. The quantum theory of entanglement and Alzheimer’s. J. Alzheimers Neurodegener. Dis. 2019, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, D. Entangling the social: Comments on alexander wendt, quantum mind and social science. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2018, 48, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S. , Das, A., Banerjee, A. & Chakrabarti, A. Comparative study of noises over quantum key distribution protocol. In International Conference on Data Management, Analytics & Innovation (ed. Bhattacharyya, S.) 759–782 (Springer, 2023).

- Jong Yeon Lee, Yi-Zhuang You, and Cenke Xu. Symmetry protected topological phases under decoherence. arXiv:2210.16323, (2022).

- Khalid, U.; Jeong, Y.; Shin, H. Measurement-based quantum correlation in mixed-state quantum metrology. Quantum Inf. Process. 2018, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triggiani, D.; Facchi, P.; Tamma, V. The role of auxiliary stages in gaussian quantum metrology. Photonics 2022, 9, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apellaniz, I.; Kleinmann, M.; Gühne, O.; Tóth, G. Optimal witnessing of the quantum fisher information with fewmeasurements. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 032330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckey, J.L.; Cerezo, M.; Sone, A.; Coles, P. J. Variational quantum algorithm for estimating the quantum fisher information. Phys. Rev. Res. 2022, 4, 013083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, A.; Branciard, C.; Minguzzi, A.; Vermersch, B. Quantum fisher information from randomized measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 260501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li-Yun, H.; Rao, Z.-M.; Kuang, Q.-Q. Evolution of quantum states via weyl expansion in dissipative channel. Chin. Phys. B 2019, 28, 084206. [Google Scholar]

- Naikoo, J.; Banerjee, S.; Srikanth, R. Quantumness of channels. Quantum Inf. Process. 2021, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falaye, B.J.; et al. Investigating quantum metrology in noisy channels. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Jin, D.Y.; Qiu, Y.; Lam, C.H.; You, J.Q. Cross-Kerr effect on an optomechanical system. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 93, 023844. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Fan, X.-G.; Xiong, W.; Wang, D.; Ye, L. Nonreciprocal entanglement in cavity-magnon optomechanics. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, 024105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zheng, Q. Enhancing stationary optomechanical entanglement with the Kerr medium. Chinese Physics B 2013, 22, 064206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagel, D.; Alvermann, A.; Fehske, H. Dynamic Stark effect, light emission, and entanglement generation in a laser-driven quantum optical system. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.03788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal Anwar, M.R.; Khalid Khan, M. Effect of Stark- and Kerr-like medium on the entanglement dynamics of two three-level atomic systems. Quantum Information Processing 2019, 18, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, S. Quantum Fisher information for moving three-level atom. Quantum Inf. Process. 2013, 12, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, C.P. Quantum Fisher information flow and non-Markovian processes of open systems, X. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 042103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barndorff-Nielsen, O.E.; Gill, R.D.; Jupp, P.E. On quantum statistical inference. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 2003, 65, 775–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).