Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introductıon

1.1. Artificial Intelligence in Education

1.2. Artificial Intelligence in Elementary Schools

1.3. Purpose and Significance of the Study

- Quantitative dimension: Meta-analysis

- Qualitative dimension: Meta-thematic analysis

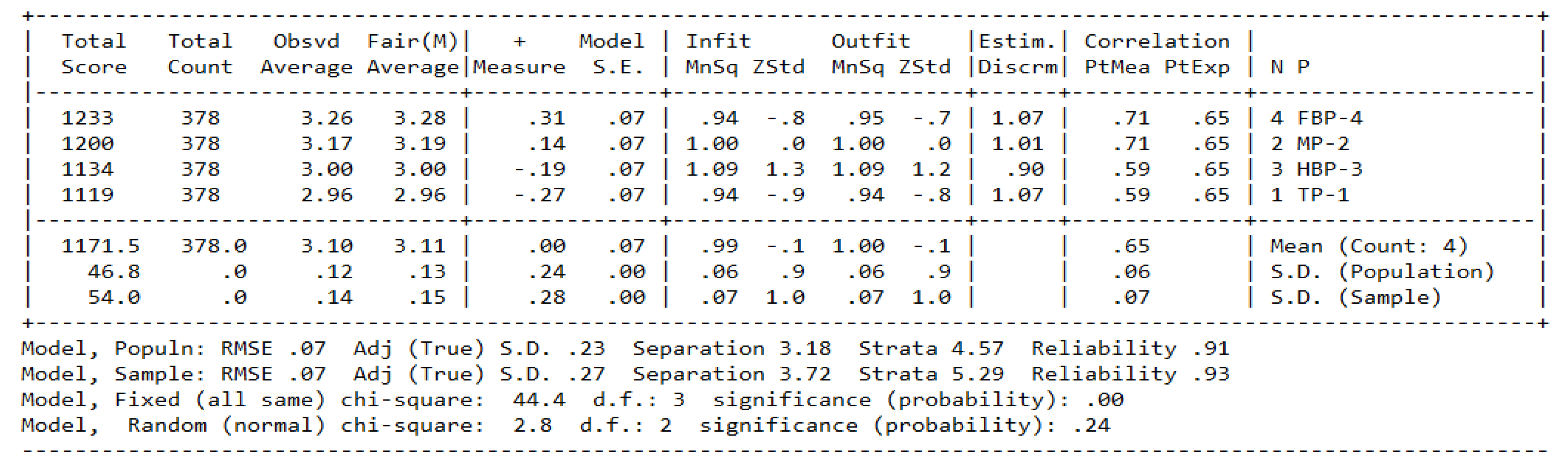

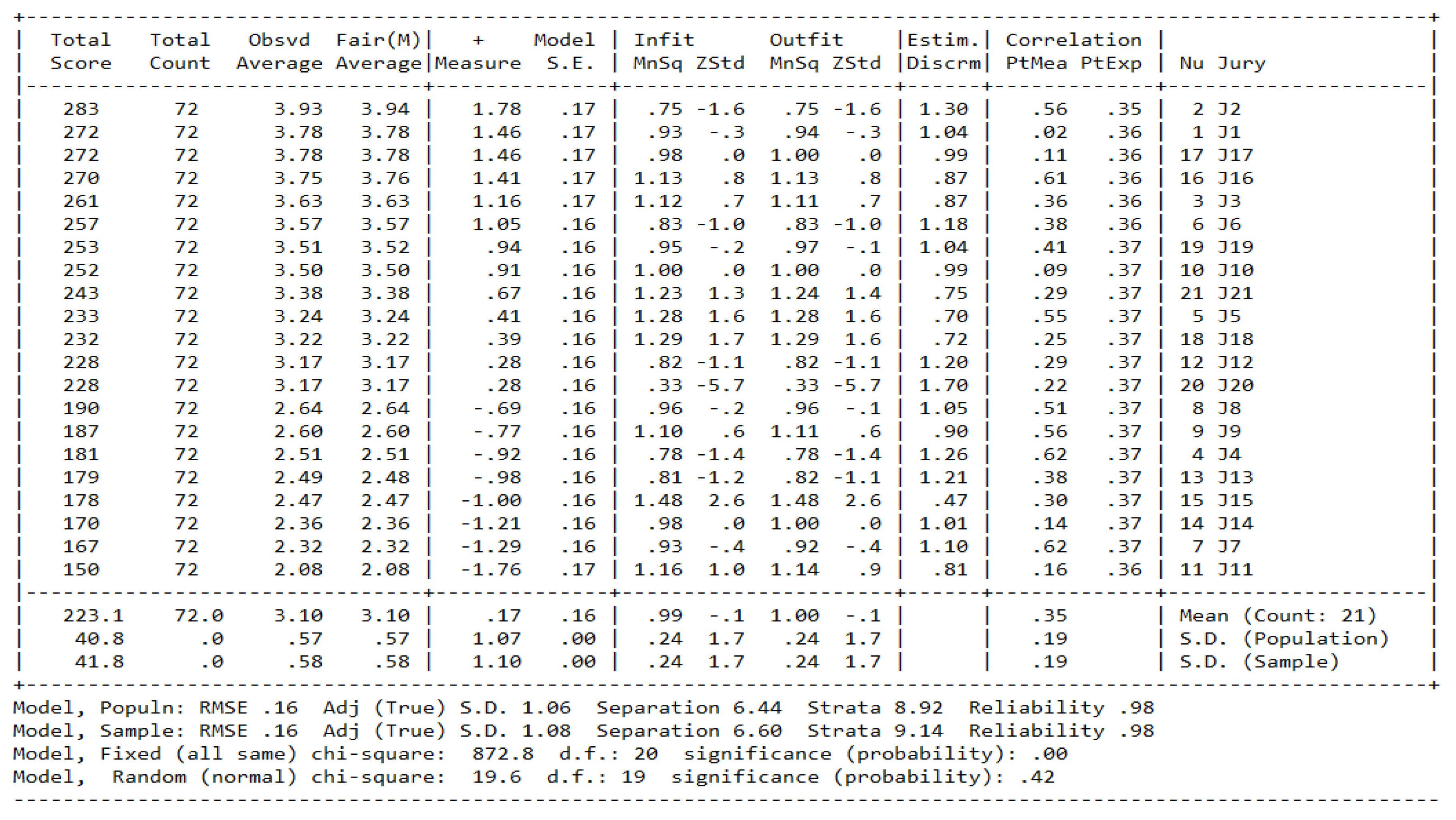

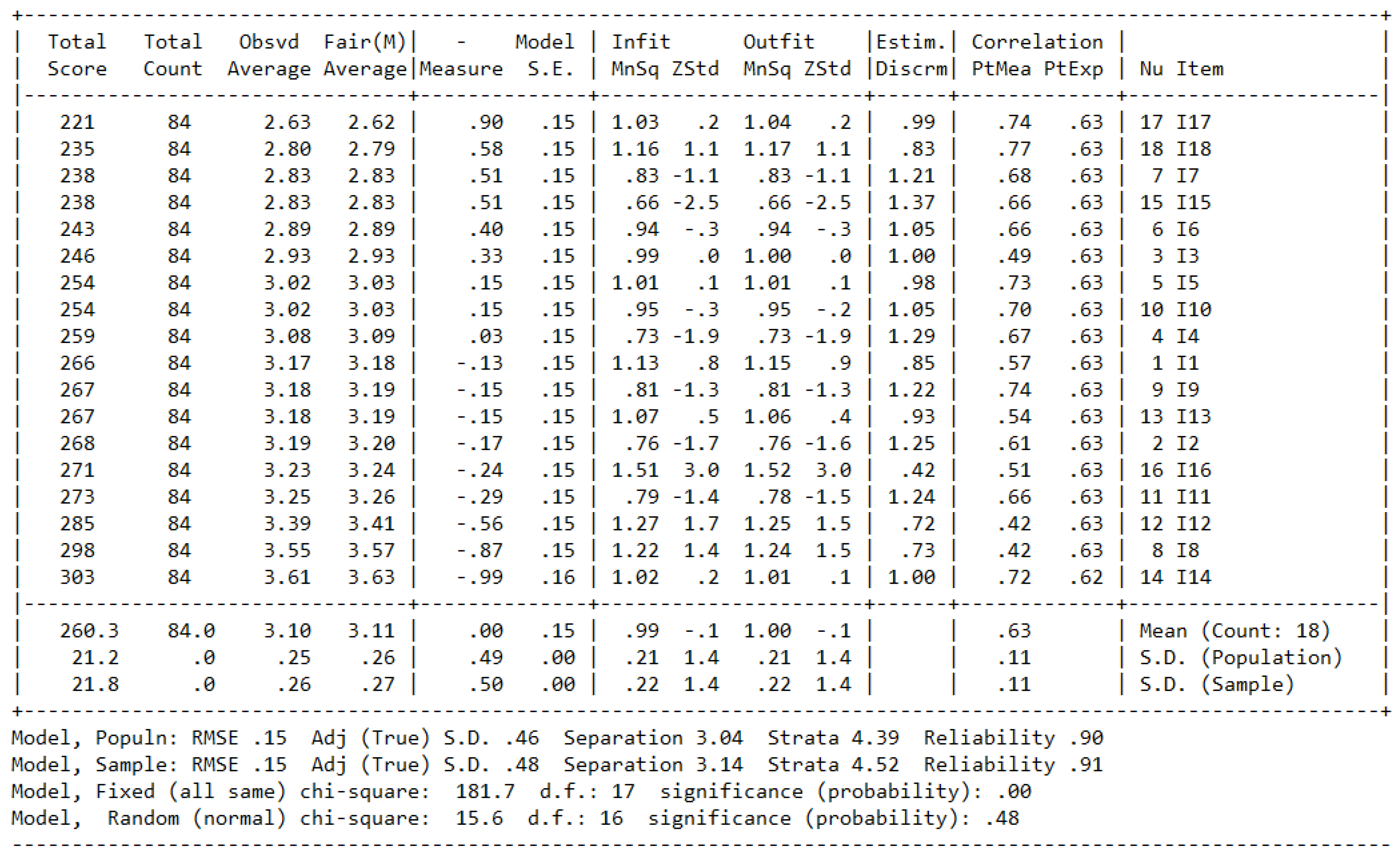

- Quantitative teacher feedback: Rasch measurement model

Meta-Analysis

- Identifying the general effect size of different variables on AI applications.

- Determining the effect size levels of AI use in terms of courses, implementation duration, and sample size.

Meta-Thematic Analysis

- 3.

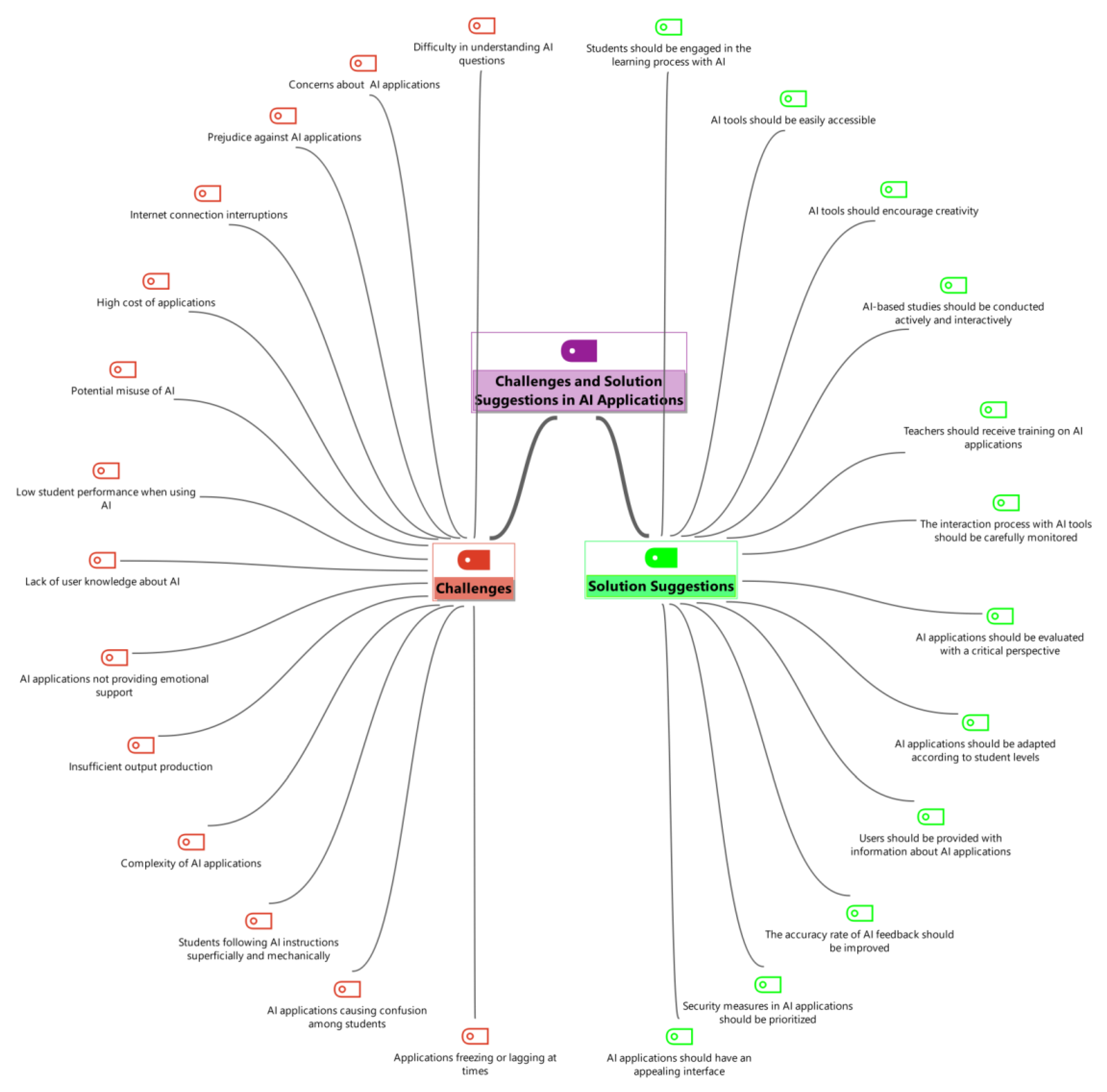

- Exploring the effects of AI applications on learning environments, identifying potential challenges in the application process, and offering solutions.

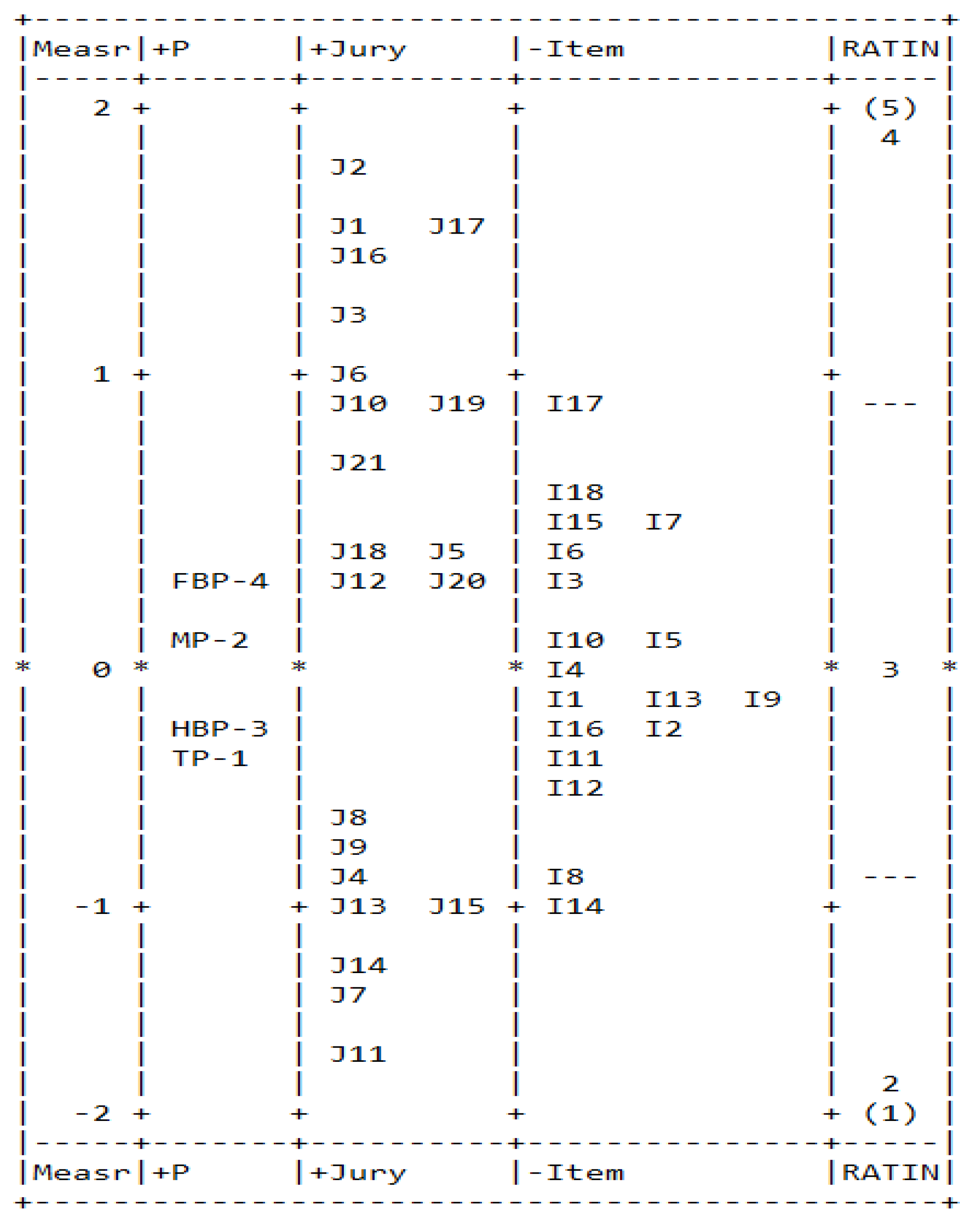

Rasch Measurement Model (Teacher Feedback)

- 4.

- Analyzing teachers’ general opinions on AI applications.

- 5.

- Examining jury tendencies towards strictness or leniency in evaluations.

- 6.

- Conducting item difficulty analysis for criteria related to AI applications.

2. Method

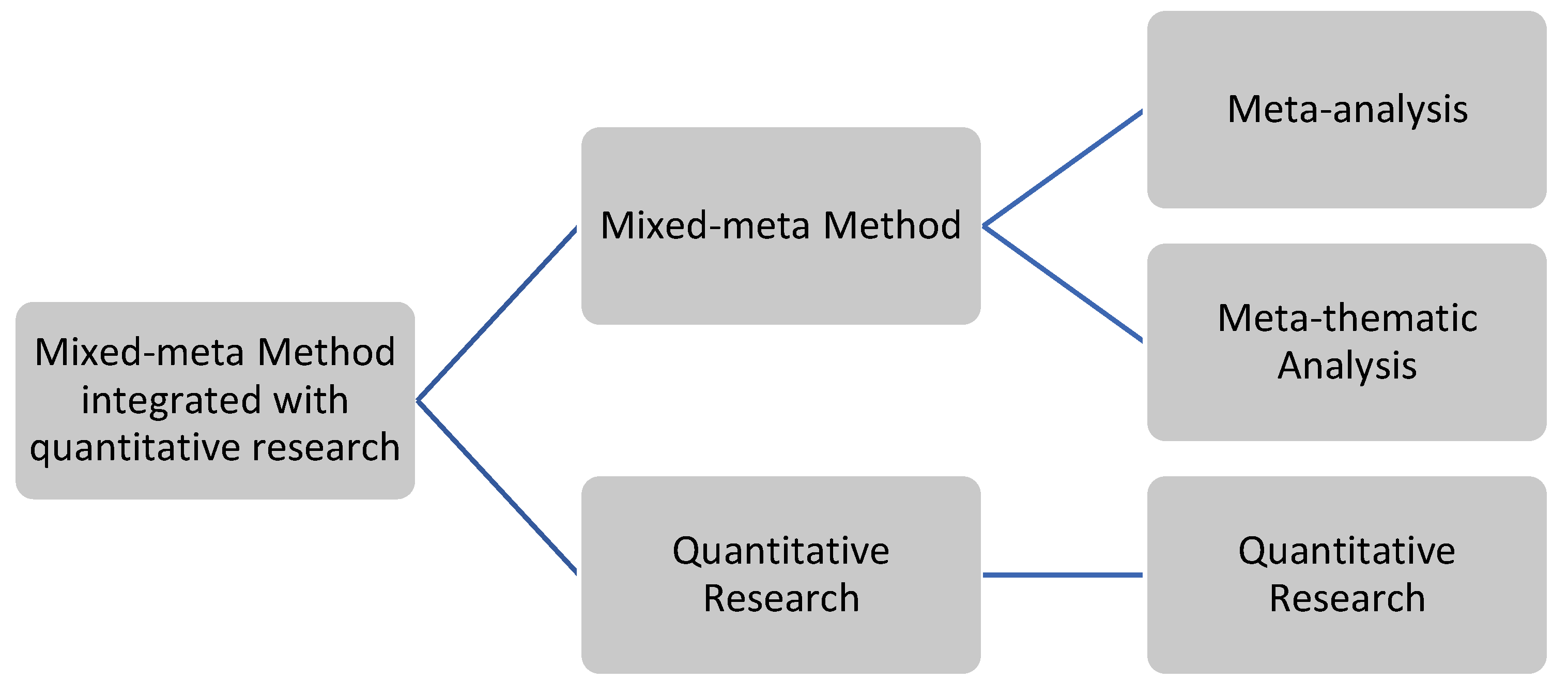

- Meta-analysis: A quantitative synthesis of data to determine the effect size of AI applications.

- Meta-thematic analysis: A qualitative examination of recurring themes in the literature, focusing on the effects of AI applications in educational contexts.

- Rasch measurement model: A quantitative analysis of participant opinions, providing insights into teacher perspectives and evaluating response consistency.

- This combination of methods ensures a scientifically robust and holistic research process. The research integrates findings from meta-analysis, meta-thematic analysis, and the Rasch model to comprehensively analyze AI applications in education. A visual representation of this methodological framework is presented in Figure 1.

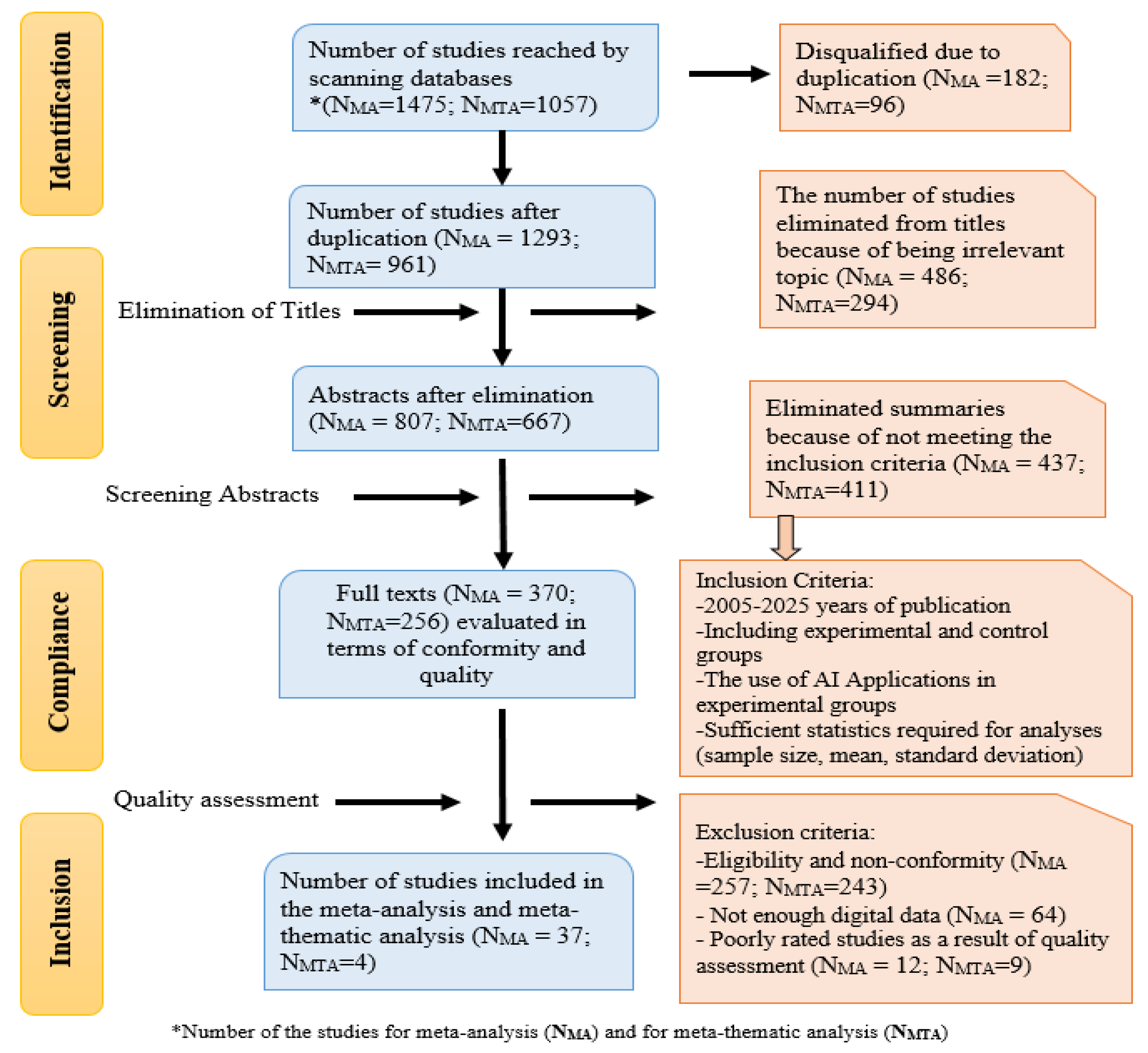

2.1. Meta-Analysis Process

2.1.1. Data Collection and Analysis

2.1.2. Effect Size and Model Selection

2.1.3. Moderator Analysis

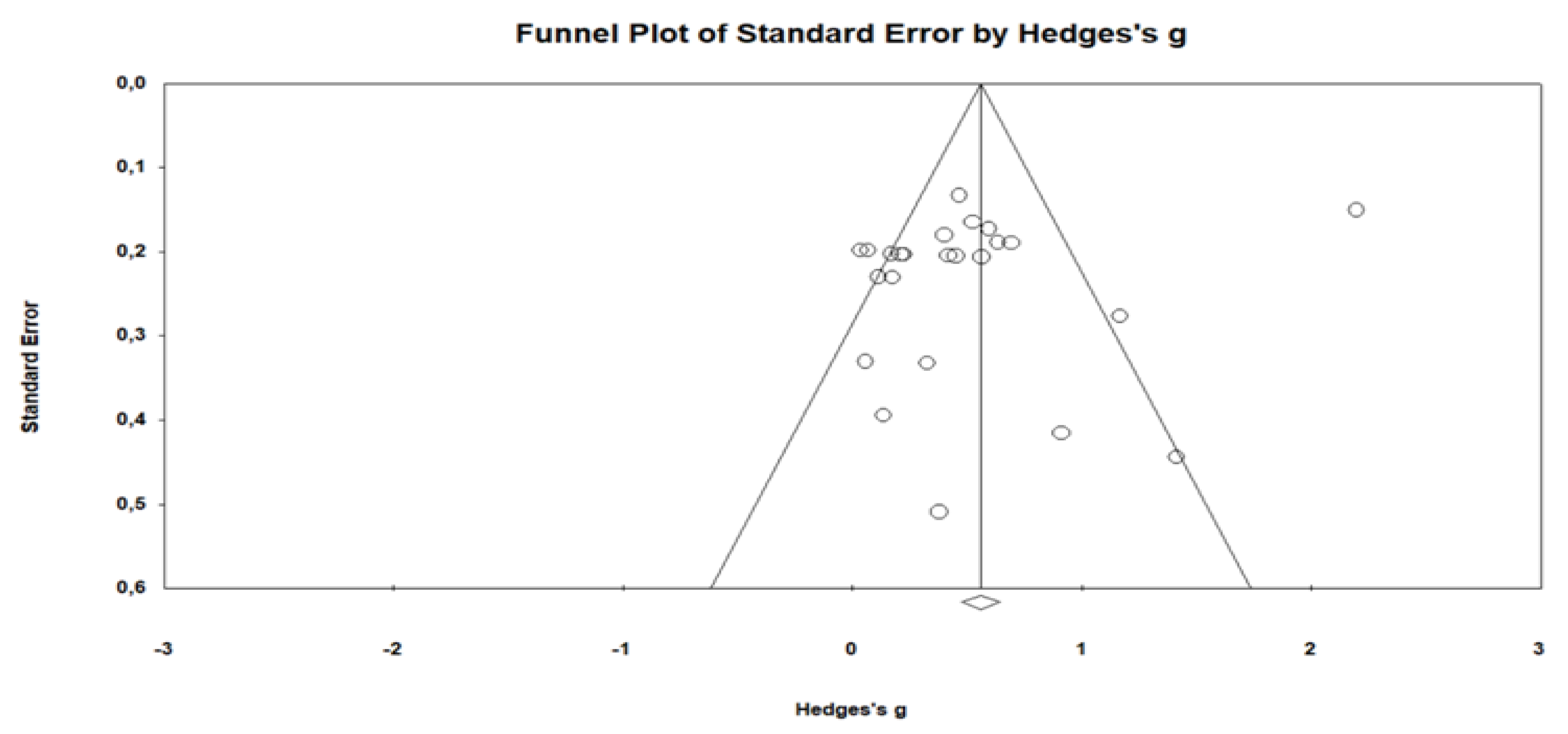

2.1.4. Publication Bias

2.2. Meta-Thematic Analysis Process

2.2.1. Data Collection and Review

2.2.2. Coding Process

2.2.3. Reliability in the Meta-Thematic Analysis Process

2.3. Rasch Measurement Model Analysis Process

2.3.1. Study Group

2.3.2. Research Data and Analysis

3. Findings

3.1. Meta-Analysis Findings on AI Applications

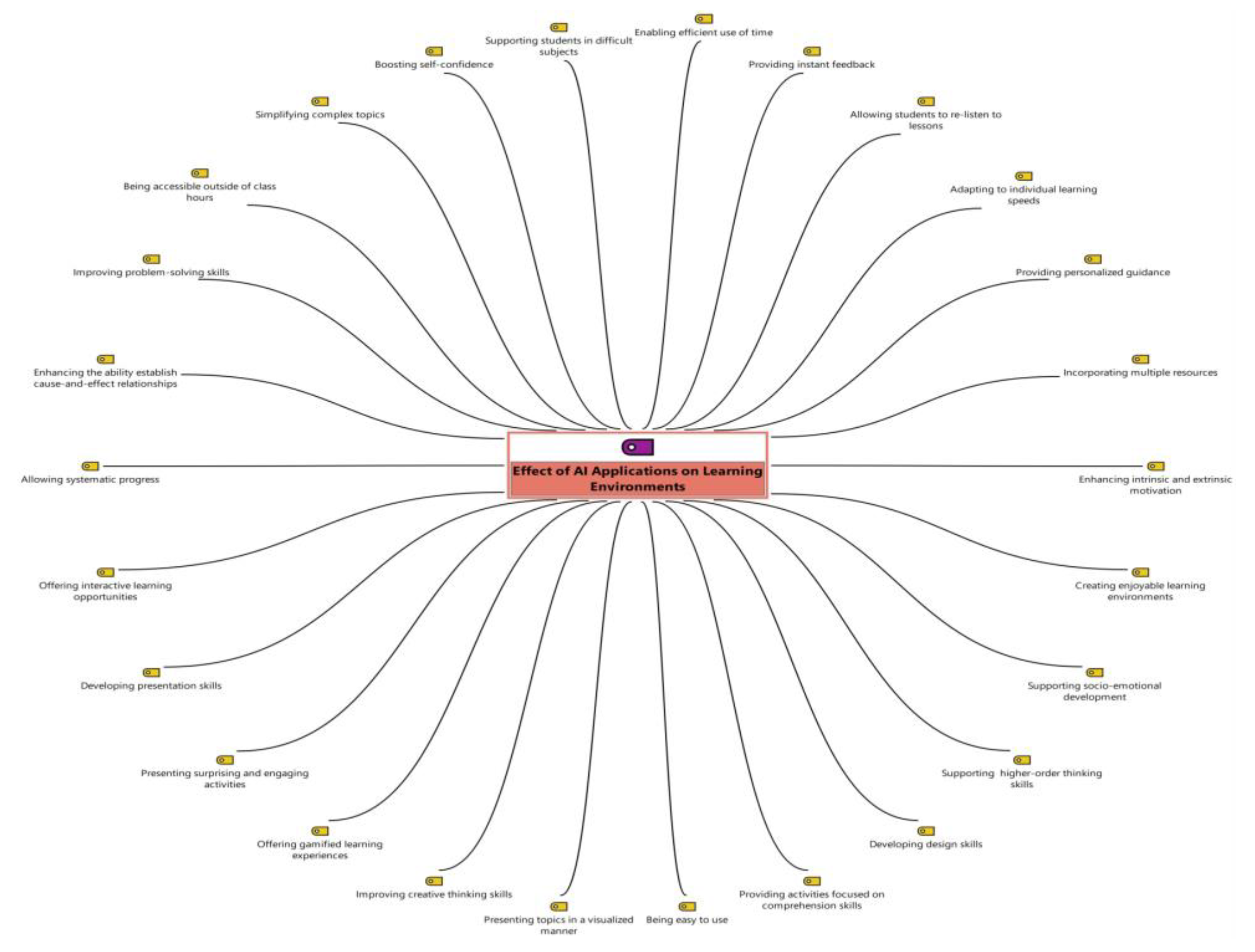

3.2. Meta-Thematic Findings Regarding Artificial Intelligence Applications

“I like to learn English with it (the AI coach) as it helps improve my English competence,” and“You can get (virtual) flowers and awards if you practice English with the AI coach every day and achieve good performance”.(M1-p. 6)

In another study: “He also started to improve his oral skills, and finally gave presentations in front of large audiences”.(M2-p. 1890)

“In my opinion, artificial intelligence is software that humans create, that we decide on the different things it learns and, after that, the computer adds them to other things it learned, like when we trained it with pictures, we also showed some pictures, and not always the computer was right, so we tried to give it more pictures and teach it things”.(M3, p. 187)

In the study (M2, p. 1822), “Students building basic robotic models benefit when they are working individually; meanwhile, students might work better in teams (ideally, two to three members per team) when working on advanced robotic models that include writing code (programming).”

3.4. Findings Related to the Rasch Measurement Model for Artificial Intelligence Applications

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Results of the Meta-Analysis Process

4.2. Results of the Meta-Thematic Analysis Process

4.3. Results Related to the Rasch Measurement Model Process

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Recommendations

- The application duration, subject areas, and sample sizes in AI-related research have significant effects on academic success and the impact of AI on educational environments. The use of the mixed-meta method, supported by the Rasch measurement model, has provided a more holistic perspective, allowing for a deeper exploration of the topic. Based on the limitations and findings of the study, the following recommendations are made:

- Research on AI applications in primary school subject areas such as art, music, and physical education can be conducted. In addition to quantitative methods, qualitative methods could be employed to explore the effectiveness and applicability of survey questions.

- The meta-analysis phase of the study could include investigations into the impact of AI applications on attitudes and long-term retention.

- Studies could explore teachers’ information and technology competencies (UNESCO, 2018) within other professional practice areas.

- The study focused on perspectives from classroom teachers. Including evaluators from different expertise levels could broaden the scope of the study.

- Despite teachers’ positive expectations regarding AI, it is essential that they first familiarize themselves with the technology and learn how to integrate it into their classrooms. Many teachers may regard AI as an advanced technological product without prior experience. In this regard, in-service training could increase teachers’ knowledge about AI and improve their integration of this technology, significantly enhancing student success and the learning experience (Kim NJ and Kim MK, 2022).

- Given the methodological diversity, the use of a mixed-meta method combined with quantitative analysis has allowed for a comprehensive examination of the findings, with detailed insights into how various variables affect the use of AI applications. Therefore, it is recommended to apply the mixed-meta method integrated with either qualitative or quantitative analyses in other areas to achieve comprehensive research findings.

- Policymakers should take necessary measures to address concerns related to ethics, data security, and human rights as AI becomes more integrated into education.

Appendix A. Agreement Value Ranges of Themes Related to Artificial Intelligence Applications

| Effect on Learning Environments | Problems Encountered | Related Solution Suggestions | Problems Encountered and Solution Suggestions | |||||||||||||||||||

| K2 | K2 | K2 | K2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| K1 | + | - | Σ | K1 | + | - | Σ | K1 | + | - | Σ | K1 | + | - | Σ | |||||||

| + | 26 | 2 | 28 | + | 14 | 1 | 15 | + | 12 | 1 | 13 | + | 26 | 2 | 28 | |||||||

| - | 3 | 18 | 21 | - | 0 | 9 | 9 | - | 1 | 7 | 8 | - | 1 | 16 | 17 | |||||||

| Σ | 29 | 20 | 49 | Σ | 14 | 10 | 24 | Σ | 13 | 8 | 21 | Σ | 27 | 18 | 45 | |||||||

| Kappa:.790 p:.000 |

Kappa: .913 p:.000 |

Kappa: .798 p:.000 |

Kappa:.860 p:.000 |

|||||||||||||||||||

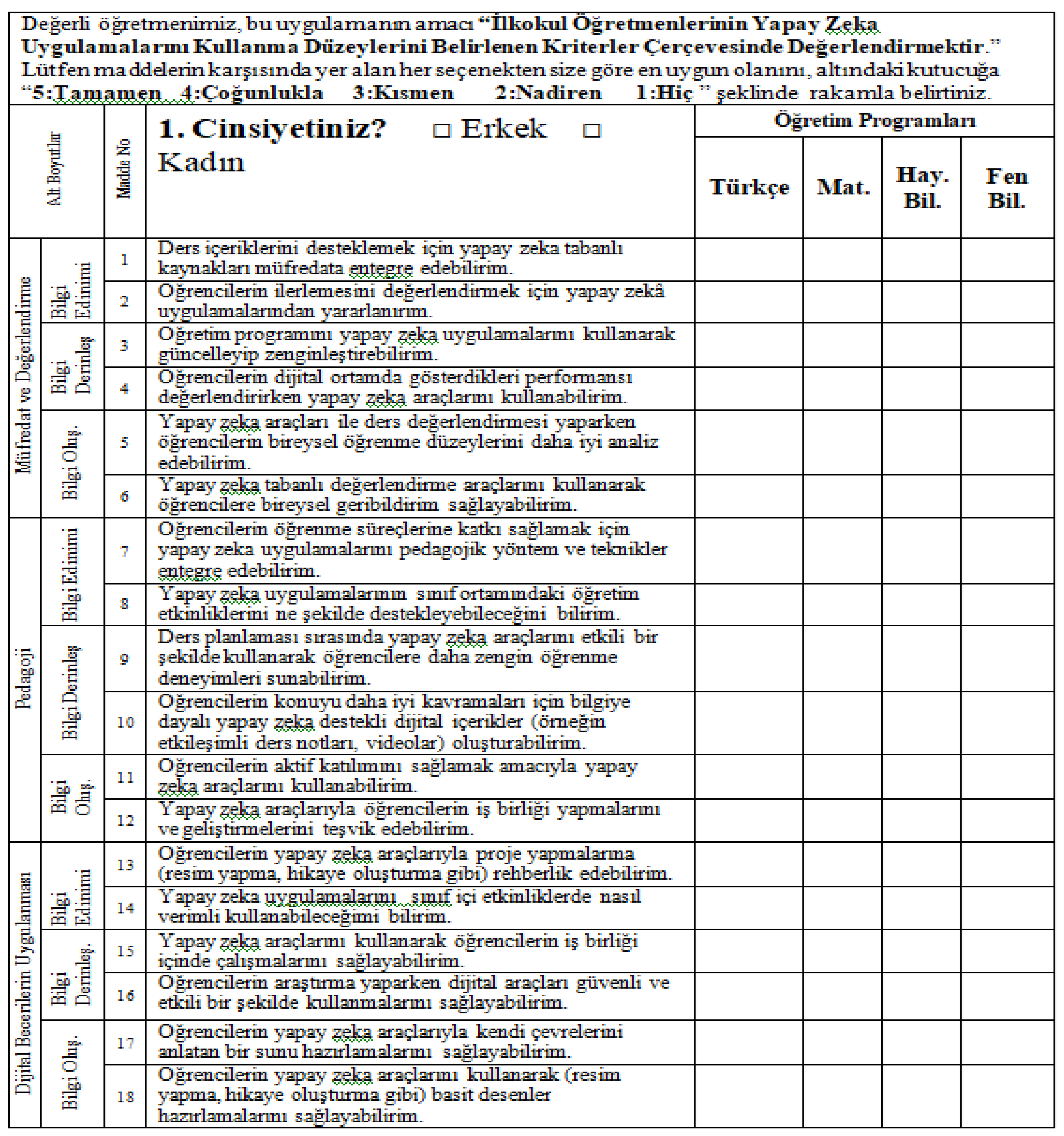

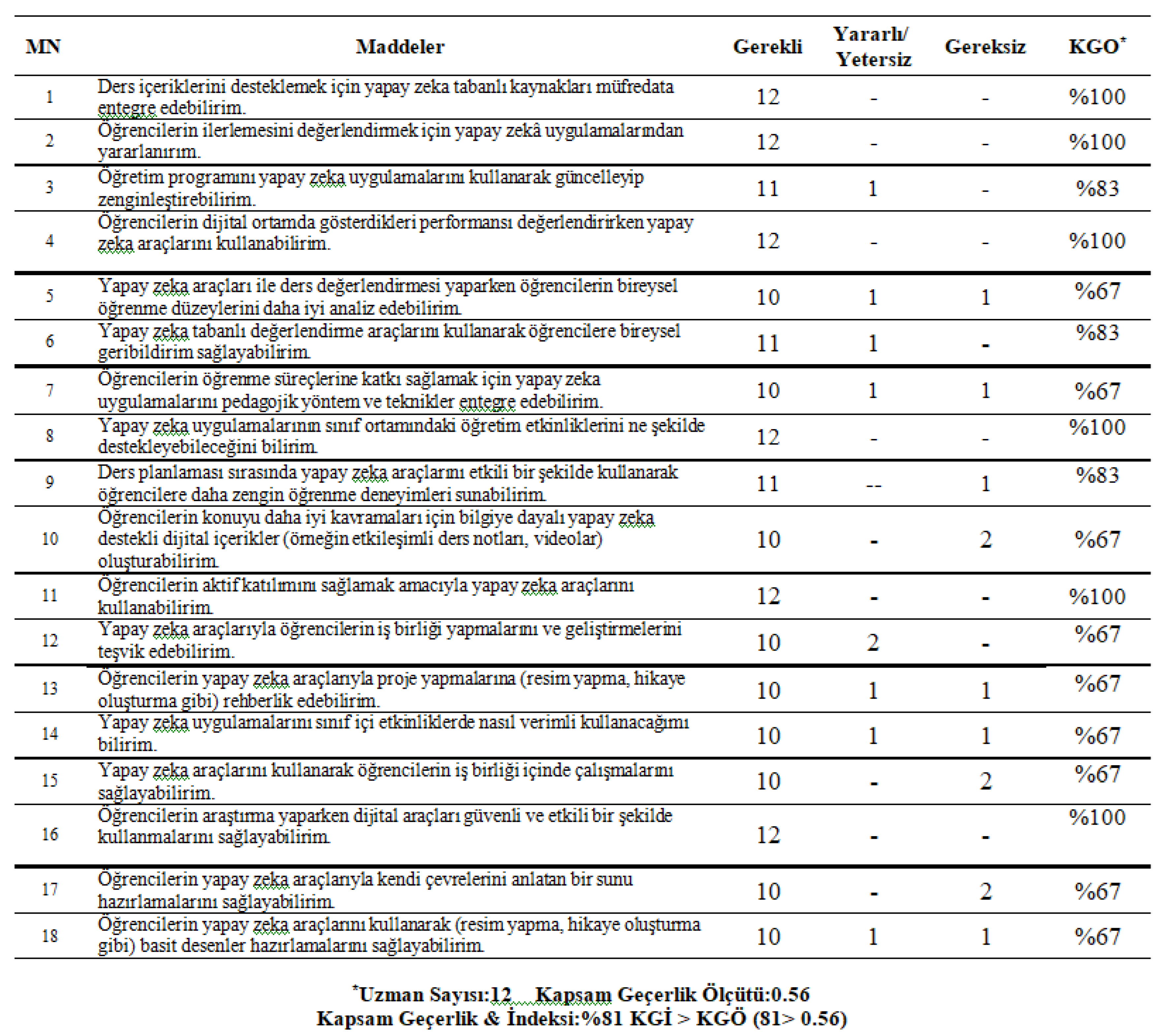

Appendix B. Primary School Teachers’ Artificial Intelligence Applications Evaluation Form

Appendix C. Content Validity Rates of Items for Evaluation of Artificial Intelligence Applications

References

- Akerkar, R. (2014). Introduction to artificial intelligence. PHI Learning Press.

- Anıl, Ö. ve Batdı, V. (2023). Use of augmented reality in science education: A mixed-methods research with the multi-complementary approach. Education and Information Technologies, 28(5), 5147-5185. [CrossRef]

- Avci, O., Abdeljaber, O., Kiranyaz, S., Hussein, M., Gabbouj, M. ve Inman, D. J. (2021). A review of vibration-based damage detection in civil structures: From traditional methods to machine learning and deep learning applications. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 147, Article 107077. [CrossRef]

- Baştürk, R. (2010). Bilimsel araştırma ödevlerinin çok yüzeyli Rasch ölçme modeli ile değerlendirilmesi. Journal of Measurement and Evaluation in Education and Psychology, 1(1), 51-57.

- Baştürk, R. ve Işıkoğlu, N. (2008). Okul öncesi eğitim kurumlarının işlevsel kalitelerinin çok yüzeyli Rasch modeli ile analizi. Kuram ve Uygulamada Eğitim Bilimleri, 8(1), 7-32.

- Batdı, V. (2014a). Ortaöğretim matematik öğretim programı içeriğinin Rasch ölçme modeli ve Nvıvo ile analizi. Turkish Studies, 9(11), 93-109. [CrossRef]

- Batdı, V. (2014b.). Kavram haritası tekniği ile geleneksel öğrenme yönteminin kullanılmasının öğrencilerin başarıları, bilgilerinin kalıcılığı ve tutumlarına etkisi: bir meta-analiz çalışması, Dumlupınar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 42, 93-102.

- Batdı, V. (2019). Meta-thematic analysis. In V. Batdı (Ed.), Meta-thematic analysis: sample applications (pp. 10–76). Anı Publication.

- Batdı, V. (2021). Yabancılara dil öğretiminde teknolojinin kullanımı: bir karma-meta yöntemi. Milli Eğitim Dergisi, 50(1), 1213-1244. [CrossRef]

- Batdı, V. (2024a). Farklı değişkenlerin öznel iyi oluş düzeyine etkisi: nitel analizle bütünleştirilmiş karma-meta yöntemi. Gaziantep Üniversitesi Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi, 8(1), 53-83.

- Batdı, V. (Ed.). (2024b). Meta-tematik analiz örnek uygulamalar. Anı Yayıncılık.

- Benvenuti, M., Cangelosi, A., Weinberger, A., Mazzoni, E., Benassi, M., Barbaresi, M. ve Orsoni, M. (2023). Artificial intelligence and human behavioral development: A perspective on new skills and competences acquisition for the educational context. Computers in Human Behavior, 148. [CrossRef]

- Barnard, Y. F. ve Sandberg, J. A. (1988). Applying artificial intelligence insights in a CAI program for “open sentence” mathematical problems in primary schools. Instructional Science, 17(3), 263-276. [CrossRef]

- *Bers, M. U., Flannery, L., Kazakoff, E. R. ve Sullivan, A. (2014). Computational thinking and tinkering: Exploration of an early childhood robotics curriculum. Computers & education, 72, 145-157. [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T. ve Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to Meta-analysis. Wiley.

- Bowen, G.A. (2008). Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qualitative Research, 8(1), 137–152. [CrossRef]

- Bracaccio, R., Hojaij, F. ve Notargiacomo, P. (2019). Gamification in the study of anatomy: The use of artificialintelligence to improve learning. The FASEB Journal, 33(1_supplement), 444-28. [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford university press.

- *Bush, J. B. (2021). Software-based intervention with digital manipulatives to support student conceptual understandings of fractions. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(6), 2299-2318. [CrossRef]

- Camnalbur, M. (2008). Bilgisayar destekli öğretimin etkililiği üzerine bir meta analiz çalışması [Yayımlanmamış yüksek lisans tezi]. Marmara Üniversitesi.

- Candan, F. ve Başaran, M. (2023). A meta-thematic analysis of using technology-mediated gamification tools in the learning process. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Chen, P. ve Lin, Z. (2020). Artificial intelligence in education: a review. IEEE Access, 8, 75264-75278. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S-Y., Lin, P-H. ve Chien, W-C. (2022). Children’s digital art ability training system based on aı-assisted learning: a case study of drawing color perception. Front in Psychol. 13. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T. K. (2021). A Holistic approach to the design of Artificial Intelligence (AI) education for k-12 schools. TechTrends, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T. K. F. ve Chai, C.-s. (2020). Sustainable curriculum planning for artificial ıntelligence education: a self-determination theory perspective. Sustainability, 12(14), 5568. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T. K., Xia, Q., Zhou, X., Chai, C. S. ve Cheng, M. (2023). Systematic literature review on opportunities, challenges, and future research recommendations of artificial intelligence in education. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 4, 100118. [CrossRef]

- *Christopoulos, A., Kajasilta, H., Salakoski, T. ve Laakso, M. J. (2020). Limits and virtues of educational technology in elementary school mathematics. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 59-81. [CrossRef]

- *Chu, H. C., Chen, J. M., Kuo, F. R. ve Yang, S. M. (2021). Development of an adaptive game-based diagnostic and remedial learning system based on the concept-effect model for improving learning achievements in mathematics. Educational Technology & Society, 24(4), 36-53. https://www.j-ets.net/collection/published-issues/24_4.

- *Chu, Y.-S., Yang, H.-C., Tseng, S.-S. ve Yang, C.-C. (2014). Implementation of a model-tracing-based learning diagnosis system to promote elementary students’ learning in mathematics. Educational Technology & Society, 17(2), 347–357. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.17.2.347.

- Cohen, J. A. (1960). Coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Education and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37-46.

- Cooper, H., Hedges, L. V. ve Valentine, J. C. (2009). The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (2. baskı.). Russell Sage Publication.

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Gutmann M, Hanson W. (2003). Advanced mixed methods research designs. Tashakkori A, Teddlie C (Eds.) Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research içinde. (s. 209–240). Sage.

- Creswell, J. W. ve Sözbilir, M. (2017). Karma yöntem araştırmalarına giriş. Pegem Akademi.

- Dağyar, M. (2014). Probleme dayalı öğrenmenin akademik başarıya etkisi: bir meta-analiz çalışması [Yayımlanmamış yüksek lisans tezi]. Hacettepe Üniversitesi.

- Doğan, O. ve Baloğlu, N. (2020). Üniversite öğrencilerinin endüstri 4.0 kavramsal farkındalık düzeyleri. TÜBAV Bilim Dergisi, 13(1), 126-142.

- Duval, S. ve Tweedie, R. (2000). A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Journal of the american statistical association, 95(449), 89-98.

- Ellis, R. D. ve Allaire, J. C. (1999). Modeling computer interest in older adults: The role of age, education, computer knowledge, and computer anxiety. Human factors, 41(3), 345-355.

- Fitton, V. A., Ahmedani, B. K., Harold, R. D. ve Shifflet, E. D. (2013). The role of technology on young adolescent development: Implications for policy, research and practice. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 30, 399-413. [CrossRef]

- *Francis, K., Rothschuh, S., Poscente, D. ve Davis, B. (2022). Malleability of spatial reasoning with short-term and long-term robotics interventions. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 27(3), 927-956. [CrossRef]

- Fu, S., Gu, H. ve Yang, B. (2020). The affordances of AI-enabled automatic scoring applications on learners’ continuous learning intention: An empirical study in China. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(5), 1674-1692. [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D. R. (2017). E-learning in the 21st century: A community of inquiry framework for research and practice. Routledge.

- Ginsenberg, M. (2012). Essentials of artificial intelligence. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

- Glass, G. V. (1976). Primary secondary and meta-analysis of research. Educational Researcher, 5, 3-8.

- Goldie, J. G. S. (2016). Connectivism: A knowledge learning theory for the digital age? Medical Teacher, 38(10), 1064–1069. [CrossRef]

- *González-Calero, J. A., Cózar, R., Villena, R., & Merino, J. M. (2019). The development of mental rotation abilities through robotics-based instruction: An experience mediated by gender. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(6), 3198-3213. [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.C.H. (2022). A model for putting connectivism into practice in a classroom environment. [Unpublished Master Thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa], NOVA Information Management School.

- Güler, N. ve Gelbal, S. (2010). A study based on classic test theory and many facet Rasch model. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 38, 108-125.

- Güneş, Z. (2021). Fen bilimlerinde FETEMM ( fen, teknoloj, matematik, mühendislik) uygulamalarının çoklu bütüncül yaklaşımla karşılaştırmalı analizi[Yayımlanmamış yüksek lisan tezi].Kilis 7 Aralık Üniversitesi.

- Hambleton, R. K. ve Swaminathan, H. (1985). Estimation of Item and Ability Parameters. Item Response Theory: Principles and Applications içinde (s. 125-150). Springer Netherlands.

- Hamet, P. ve Tremblay, J. (2017). Artificial intelligence in medicine. Metabolism Clinical and Experimental, 69,36-40. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J. ve Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj, 327(7414), 557-560.

- Holmes, W., Bialik, M. ve Fadel, C. (2019). Artificial intelligence in Education. Center for Curriculum Redesign. [CrossRef]

- Hoorn, J. F., Huang, I. S., Konijn, E. A. ve van Buuren, L. (2021). Robot Tutoring of Multiplication: Over One-Third Learning Gain for Most, Learning Loss for Some. Robotics, 10(1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Humble, N. ve Mozelius, P. (2019). Artificial Intelligence in Education-a Promise, a Threat or a Hype?. In European Conference on the Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Robotics 2019 (ECIAIR 2019), Oxford, UK 149– 156.

- İlhan, M. (2016). Açık uçlu sorularla yapılan ölçmelerde klasik test kuramı ve çok yüzeyli Rasch modeline göre hesaplanan yetenek kestirimlerinin karşılaştırılması. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 31(2), 346-368. [CrossRef]

- Jain, P., Coogan, S. C., Subramanian, S. G., Crowley, M., Taylor, S. ve Flannigan, M. D. (2020). A review of machine learning applications in wildfire science and management. Environmental Reviews, 28(4), 478–505. [CrossRef]

- Jia, J., He, Y. ve Le, H. (2020). A multimodal human-computer interaction system and its application in smart learning environments, in International Conference on Blended Learning, (Cham: Springer), 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Kablan, Z., Topan, B., ve Erkan, B. (2013). Sınıf içi öğretimde materyal kullanımının etkililik düzeyi: bir meta-analiz çalışması. Kuram ve Uygulamada Eğitim Bilimleri, 13(3), 1629-1644.

- **Kajiwara, Y., Matsuoka, A., Shinbo, F. (2023). Machine learning role playing game: Instructional design of AI education for age-appropriate in K-12 and beyond. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan-Rakowski, R., Grotewold, K., Hartwick, P. ve Papin, K. (2023). Generative AI ve teachers’ perspectives on ıts ımplementation in education. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 34(2), 313-338.Retrieved January 13, 2025 from https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/222363/.

- Ke, F. (2010). Examining online teaching, cognitive, and social presence for adult students. Computers & Education, 55(2), 808-820. [CrossRef]

- Kim NJ ve Kim MK (2022) Teacher’s Perceptions of Using an Artificial Intelligence-Based Educational Tool for Scientific Writing, Frontiers in Education. 7:755914. [CrossRef]

- Koçel, T. (2017). Yönetim ve organizasyonda metodoloji ve güncel kavramlar. İstanbul Üniversitesi İşletme Fakültesi Dergisi, 46, 3-8.

- Komalavalli, K., Hemalatha, R. ve Dhanalakshmi, S. (2020). A survey of artificial intelligence in smart phones and its applications among the students of higher education in and around Chennai City. Shanlax Internatıonal Journal of Education, 8(3), 89-95. [CrossRef]

- Köse, İ. A., Usta, H. G. ve Yandı, A. (2016). Sunum yapma becerilerinin çok yüzeyli rasch analizi ile değerlendirilmesi. Abant İzzet Baysal Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 16(4), 1853-1864.

- Lawshe, C. H. (1975). A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology, 28, 563–575.

- Li, B., Hou, B., Yu, W., Lu, X. ve Yang, C. (2017). Applications of artificial intelligence in intelligent manufacturing: A review. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering, 18(1), 86-96. [CrossRef]

- Li, M. ve Su, Y. (2020). Evaluation of online teaching quality of basic education based on artificial ıntelligence. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 15(16), 147–161. [CrossRef]

- *Li, X., Xiang, H., Zhou, X. ve Jing, H. (2023, June). An empirical study on designing STEM+ AI teaching to cultivate primary school students’ computational thinking perspective. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Distance Education and Learning (pp. 1-7).

- Liang, Y. ve Chen, L. (2018). Analysis of current situation, typical characteristics and development trend of artificial intelligence education application. China Electrofication Education, 2018(3), 24-30.

- *Lin, X. F., Wang, Z., Zhou, W., Luo, G., Hwang, G. J., Zhou, Y. ve Liang, Z. M. (2023). Technological support to foster students’ artificial intelligence ethics: An augmented reality-based contextualized dilemma discussion approach. Computers & Education, 201. [CrossRef]

- Linacre, J. M. (1993). Generalizability theory and many facet Rasch measurement. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED364573.pdf.

- Linacre, J. M. (2008). A user’s guide to winsteps, ministep Rasch-model computer programs, program manuel, 3.66, P.O. Box. 811322, Chicago IL 60681-1322.

- Litan, A. (2021). Hype Cycle for Blockchain 2021; More Action than Hype. Gartner. https://blogs.gartner.com/avivahlitan/2021/07/14/hype-cycle-for-blockchain-2021-moreaction-than-hype.

- Luckin, R., Holmes, W., Griffiths, M. ve Forcier, L.B. (2016). Intelligence Unleashed - an Argument for AI in Education. CL Knowledge Lab.

- Luo, D. (2018). Guide teaching system based on artificial ıntelligence. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 13(08), 90–102. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, B. K. ve McNamara, T. F. (1998). Using G-theory and many-facet Rasch measurement in the development of performance assessments of the ESL speaking skills of immigrants. Language Testing, 15(2), 158- 180. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, B. K. ve McNamara, T. F. (1998). Using G-theory and many-facet Rasch measurement in the development of performance assessments of the ESL speaking skills of immigrants. Language Testing, 15(2), 158-180.

- Maqbool, F., Ansari, S. ve Otero, P., 2021. The role of artificial ıntelligence and smart classrooms during covıd-19 pandemic and its impact on education. Journal of Independent Studies and Research Computing, 19(1), 7-14. [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. A Companion to Qualitative Research, 1(2), 159-176.

- MEB (2024). Eğitimde Kullanılan Yapay Zeka Araçları: Öğretmen El Kitabı. Çevrimiçi Kitap.

- Mijwil, M.M., Aggarwal, K., Mutar, D.S., Mansour, N. ve Singh, R.S.S., 2022. the position of artificial ıntelligence in the future of education: an overview. Asian Journal of Applied Sciences, 10(2), 102-108. [CrossRef]

- Miles, M, B. ve Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded Sourcebook. (2nd ed). Sage.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. 21;6(7). [CrossRef]

- Molina-Azorín, J. F., López-Gamero, M. D., Pereira-Moliner, J. ve Pertusa-Ortega, E. M. (2012). Mixed methods studies in entrepreneurship research: Applications and contributions. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(5-6), 425-456. [CrossRef]

- Mu, P. (2019). Research on artificial intelligence education and its value orientation. Paper presented at the 1stInternational Education Technology and Research Conference (IETRC 2019, China, Retrieved from https://webofproceedings.org/proceedings_series/ESSP/IETRC%202019/IETRC19165.pdf.

- Nichols, J. A., Herbert Chan, H. W. ve Baker, M. A. (2019). Machine learning: Applications of artificial intelligence to imaging and diagnosis. Biophysical reviews, 11(1), 111–118. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, F. ve Jiao, P. (2021). Artifcial intelligence in education: The three paradigms. Computers and Education: Artifcial Intelligence, 2, 100020.

- Panigrahi, C. M. A. (2020). Use of artificial intelligence in education. Management Accountant, 55, 64-67. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3606936.

- *Pareto, L. (2014). A teachable agent game engaging primary school children to learn arithmetic concepts and reasoning. International Journal of artificial intelligence in education, 24, 251-283. [CrossRef]

- Pedró, F., Subosa, M., Rivas, A. ve Valverde, P. (2019). Artificial intelligence in education: Challenges and opportunities for sustainable development. UNESCO.

- Qin, F., Li, K. ve Yan, J. (2020). Understanding user trust in artificial intelligence-based educational systems: evidence from China. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 51, 1693–1710. [CrossRef]

- Randall, N. (2019). A Survey of Robot-Assisted Language Learning (RALL). ACM Transactions on Human-Robot Interaction, 9(1), 1-36. [CrossRef]

- *Rau, M. A., Aleven, V. ve Rummel, N. (2017). Making connections among multiple graphical representations of fractions: Sense-making competencies enhance perceptual fluency, but not vice versa. Instructional Science, 45, 331-357. [CrossRef]

- *Rau, M. A., Aleven, V., Rummel, N. ve Pardos, Z. (2014). How should intelligent tutoring systems sequence multiple graphical representations of fractions? A multi-methods study. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 24, 125-161. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, B., Hancock, J. ve Liu, X. (2020). Social Robots Are Like Real People: First Impressions, Attributes, and Stereotyping of Social Robots. Technology, Mind, and Behavior, 1(1). [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.D.(2001).Glossary on meta-analysis. J.Epidemiol Community Health, 55(8). [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, R. D., Walker, E. A. ve Patchan, M. M. (2018). Facilitating peer tutoring and assessment in intelligentlearning systems. In S. D. Craig (Ed.), Tutoring and intelligent tutoring systems (pp. 41-68). Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

- Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 638–641. [CrossRef]

- Russell, S. J. ve Norvig, P. (2009). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Ryu, M. ve Han, S. (2018). The educational perception on artificial intelligence by elementary school teachers. J. Korean Assoc. Inform. Educ. 22, 317–324. [CrossRef]

- Sak, R., Sak, İ. T. Ş., Şendil, Ç. Ö. Ve Nas, E. (2021). Bir araştırma yöntemi olarak doküman analizi. Kocaeli Üniversitesi Eğitim Dergisi, 4(1), 227-256. [CrossRef]

- **Salas-Pilco, S.Z. (2020), The impact of AI and robotics on physical, social-emotional and intellectual learning outcomes: An integrated analytical framework. Br J Educ Technol, 51: 1808-1825. [CrossRef]

- Santos, O. C. (2016). Training the body: The potential of AIED to support personalized motor skills learning. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 26(2), 730-755. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F. L., Oh, I. S. ve Hayes, T. L. (2009). Fixed-versus random-effects models in meta-analysis: Model properties and an empirical comparison of differences in results. British journal of mathematical and statistical psychology, 62(1), 97-128. [CrossRef]

- Self, J. (2016). The birth of IJAIED. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 26(1), 4-12. [CrossRef]

- Semerci, Ç. (2011). Mikro öğretim uygulamalarının çok-yüzeyli Rasch ölçme modeli ile analizi. Eğitim ve Bilim, 36(161). https://egitimvebilim.ted.org.tr/index.php/EB/article/view/145 adresinden erişildi.

- Semerci, Ç. (2012). Öğrencilerin BÖTE bölümüne ilişkin görüşlerinin rasch ölçme modeline göre değerlendirilmesi (Fırat Üniversitesi örneği). Education Sciences, 7(2), 777-784.

- Shamir, G. ve Levin, I. (2021).Teaching machine learning in elementary school. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction.31 (2022). [CrossRef]

- **Shamir, G. ve Levin, I. (2024). Exploring a practical ımplementation of teaching machine learning in elementary schools. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R., Kamble, S. S., Gunasekaran, A., Kumar, V. ve Kumar, A. (2020). A systematic literature review on machine learning applications for sustainable agriculture supply chain performance. Computers and Operations Research, 119. [CrossRef]

- Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2. http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm.

- Sterne, J. A. ve Harbord, R. M. (2004). Funnel plots in meta-analysis. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 4(2), 127–141. [CrossRef]

- Streubert, H. J. ve Carpenter, D. R. (2011). Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic ımperative. Wolters Kluwer.

- Su, J. ve Yang, W. (2022). Artificial intelligence in early childhood education: A scoping review. In Computers and education: Artificial Intelligence, 3. [CrossRef]

- Talan, T. (2021). Artificial intelligence in education: A bibliometric study. International Journal of Research in Education and Science (IJRES), 7(3), 822-837. [CrossRef]

- Talan, H. (2020). Jigsaw tekniğinin çoklu bütüncül yaklaşımla analizi bağlamında fen bilgisi öğretim programında kullanılmasının değerlendirilmesi [Yayımlanmamış yüksek lisans tezi]. Kilis 7 Aralık Üniversitesi.

- Thalheimer, W. ve Cook, S. (2002). How to calculate effect sizes from published research: A simplified methodology. Work-Learning Research, 1(9), 1-9.

- Toivonen, T., Jormanainen, I., Kahila, J., Tedre, M., Valtonen, T. ve Vartiainen, H. (2020, July). Co-designing machine learning apps in K–12 with primary school children. In 2020 IEEE 20th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT) (pp. 308-310). IEEE.

- Topol, E. (2019). Deep medicine: How artificial intelligence can make healthcare human again. Basic Books.

- Toraman, S. (2021). Karma Yöntemler Araştırması: Kısa Tarihi, Tanımı, Bakış Açıları ve Temel Kavramlar. Nitel Sosyal Bilimler, 3(1), 1-29. [CrossRef]

- Tsagris, M. ve Fragkos, K. C. (2018). Meta-analyses of clinical trials versus diagnostic test accuracy studies. Diagnostic meta-analysis: A useful tool for clinical decision-making, 31-40.

- Uluman, M. ve Tavşancıl, E. (2017). Çok değişkenlik kaynaklı rasch ölçme modeli ve hiyerarşik puanlayıcı modeli ile kestirilen puanlayıcı parametrelerinin karşılaştırılması. İnsan ve Toplum Bilimleri Araştırmaları Dergisi, 6(2), 777-798. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO (2018). Öğretmenlere Yönelik Bilgi ve İletişim Teknolojileri Yetkinlik Çerçevesi. https://yegitek.meb.gov.tr/www/unesco-ogretmenlere-yonelik-bilgi-ve-iletisim-teknolojileri-yetkinlik-cercevesi/icerik/3146.

- UNESCO (2019). Artificial Intelligence in Education: Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Development. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366994.

- Veneziano L. ve Hooper J. (1997). A method for quantifying content validity of health-related questionnaires. American Journal of Health Behavior, 21(1), 67-70.

- ***Wang, X., Liu, Q., Pang, H., Tan, S. C., Lei, J., Wallace, M. P. ve Li, L. (2023). What matters in AI-supported learning: A study of human-AI interactions in language learning using cluster analysis and epistemic network analysis. Computers & Education, 194. [CrossRef]

- *Wang, X., Pang, H., Wallace, M. P., Wang, Q. ve Chen, W. (2024). Learners’ perceived AI presences in AI-supported language learning: A study of AI as a humanized agent from community of inquiry. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 37(4), 814-840. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C. (2014). Using wikis to facilitate interaction and collaboration among EFL learners: A social constructivist approach to language. System, 42, 383-390. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. P. ve Chen, Y. L. (2018). Effects of multimodal learning analytics with concept maps on college students’ vocabulary and reading performance. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 21(4), 12–25.

- Yang, W. (2022). Artificial Intelligence education for young children: Why, what, and how in curriculum design and implementation. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 3. [CrossRef]

- Yue, M., Jong, M. S. Y., & Dai, Y. (2022). Pedagogical design of K-12 artificial intelligence education: A systematic review. Sustainability, 14(23). [CrossRef]

- Yurdugül, H. (2005, Eylül). Ölçek Geliştirme Çalışmalarında Kapsam Geçerliği Için Kapsam Geçerlik Indekslerinin Kullanılması. XIV. Ulusal Eğitim Bilimleri Kongresi, Pamukkale Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi, Denizli.

- Zhang, K. ve Aslan, A. B. (2021). AI technologies for education: Recent research & future directions. Computers and Education, 2. [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Time Period | 2005-2025 |

| Publication Language | English and Turkish |

| Appropriateness of Teaching Method | Experimental and/or quasi-experimental designed studies with pre-test-post-test control groups using artificial intelligence applications |

| Statistical Data | Sample size (n), arithmetic mean (X), and standard deviation (ss) for effect size calculation |

| Test Type | Model | 95 %+ Confidence Interval | Heterogeneity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | g | Lower | Upper | Q | p | I2 | ||

| AA | FEM | 24 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 163.11 | 0.00 | 85.90 |

| REM | 24 | 0.51 | 0.28 | 0.74 | ||||

| Items | Groups | Effect Size and 95% Confidence Interval | Null Test | Heterogeneity | ||||||

| n | g | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Z-value | P-value | Q-value | df | P-value | ||

| Application Duration | 1-4 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.30 | 0.88 | 4.01 | 0.00 | |||

| 5+ | 0.09 | 0.09 | -0.15 | 0.33 | 0.75 | 0.45 | ||||

| Unspecified | 0.58 | 0.58 | -0.02 | 1.19 | 1.89 | 0.06 | ||||

| Total | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.50 | 3.54 | 0.00 | 7.69 | 2 | 0.02 | |

| Subjects | Maths | 19 | 0.44 | 0.18 | 0.71 | 3.25 | 0.01 | |||

| AI | 3 | 0.80 | 0.07 | 1.53 | 2.15 | 0.03 | ||||

| Others | 2 | 0.81 | 0.19 | 1.44 | 2.54 | 0.01 | ||||

| Total | 24 | 0.53 | 0.30 | 0.76 | 4.47 | 0.00 | 1.7 | 2 | 0.43 | |

| Sample Size | Small | 6 | 0.50 | 0.09 | 0.90 | 2.40 | 0.02 | |||

| Medium | 9 | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.55 | 3.93 | 0.00 | ||||

| Large | 6 | 0.63 | 0.18 | 1.08 | 2.75 | 0.01 | ||||

| Total | 24 | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.57 | 5.24 | 0.00 | 1.29 | 2 | 0.52 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).