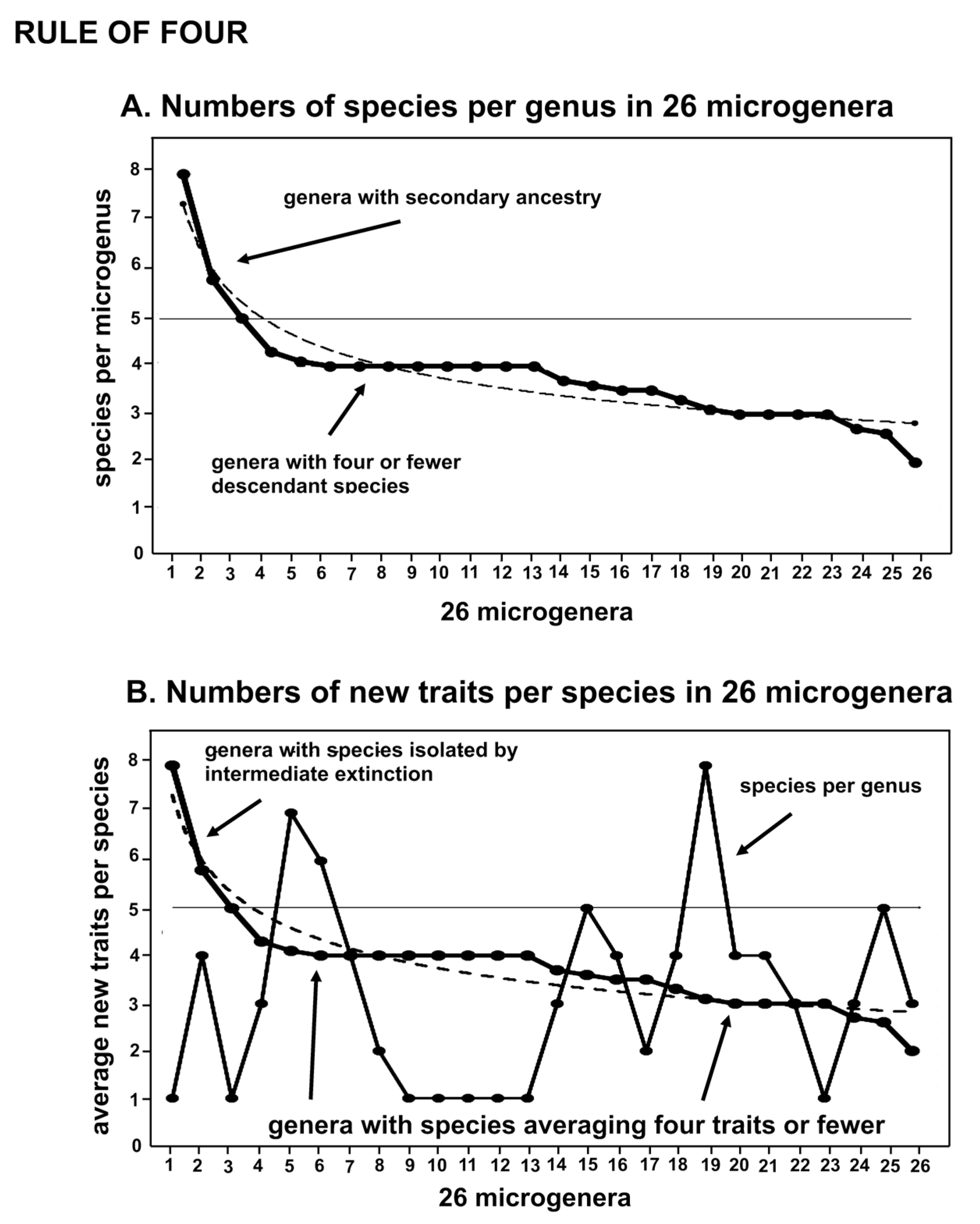

3.2. Graphed Rule of Four

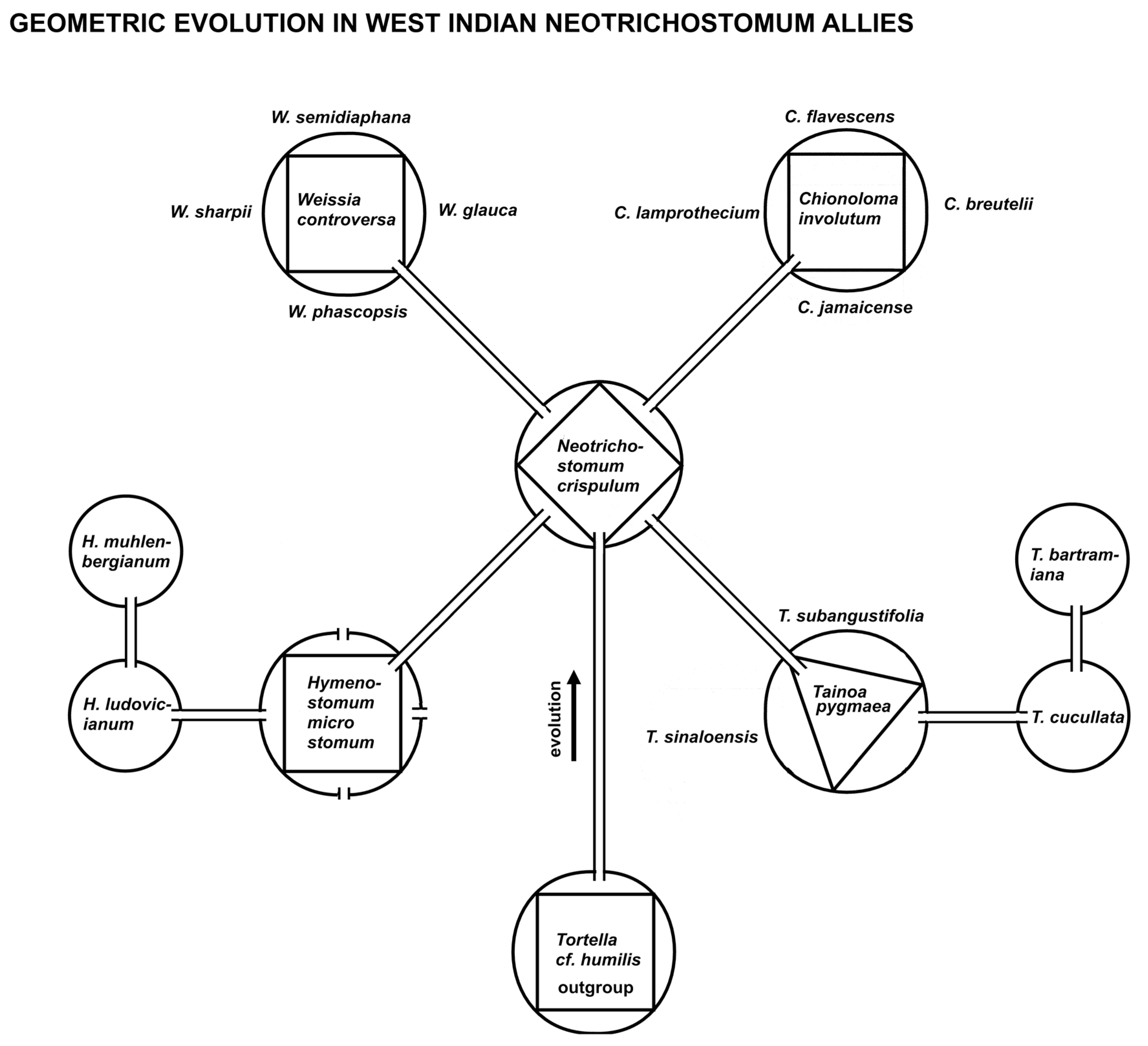

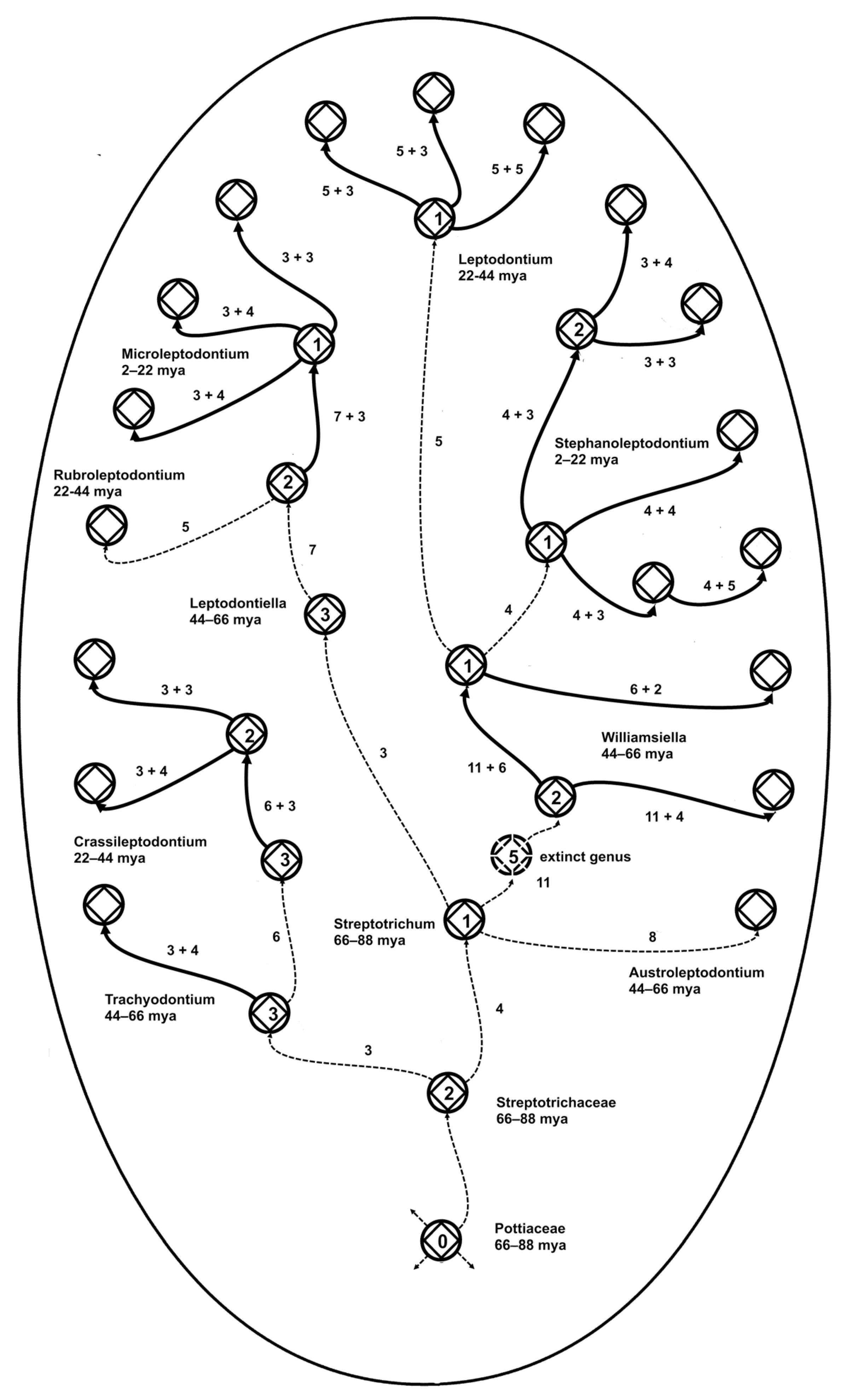

The evolutionary rule of four reflects the fact that four is the optimum number of new species generated by a single ancestral species (Fig. 1), with variation doubtless due to extinction and secondary ancestry. There is also an average maximum of four new traits involved in speciation. The rule for traits is sufficiently stable that among the 10 genera in the moss family Streptotrichaceae, mostly different from each other by about four new traits per speciation, the 11 new-trait distance between two of the contiguous ancestral species implies the extinction of one species or more probably, given an great ages of that portion of the lineage, an entire genus. That there is evidence for the extinction of only one genus across an estimated 88 million years of existence of this family [

22], implies that there may be lessons to be learned about evolutionary adaptive resilience in the face of environmental change.

Zander [

22,

35] showed that redundancy of apparently adaptive traits, similar to Shannon information optimization, is a key to survival of this family of mosses, and perhaps any large taxonomic group. Hamming Code error correction commonly requires 1/7 of the total bits to be redundant. The redundancy of fractal microgenera is massive, with every immediate descendant carrying the most recently gained traits of the ancestral species. The error correction is most likely natural selection, through balancing selection plus extinction and replacement. For descendant species established allopatrically, redundancy becomes mutualism as novon traits of species sharing an environmental niche mesh [

19] pp. 118 and 121 to form another redundancy-supported group, the realized niche. How this, or other ingrained algorithms, may operate in nature requires much more research but should be of great value. Analysis of Shannon information and entropy in nature [

51,

52] is doubtless a guide.

Guy [

45] lamented the fact that there are too few small integers for the multiplicity of processes involving simple relationships. Numbers with many numerals, including decimal fractions like pi or the square root of two, are unique and associated with particular processes in nature. As noted above in the discussion of balancing radiation, small whole numbers appear to be generated by a number of hidden processes that entail crowding or isolation. This is particularly true if associated with a power rule, or hollow curve, as illustrated in Figs. 2 and 6, which, at least, ensures the rarity of large numbers. Competition involving many traits, so descendant species as novel peripheral isolates may well be curtailed by complexity-based evolutionary processes restricting large numbers. Nature is apparently replete with processes governed or at least described by power rules and associated hollow curves implying fractal and self-similar results [

44,

53].

There are a number of rules of thumb regarding small whole numbers. The Rule of Five states that, with only five random samples from a population, there is a 0.9375 probability of having the median value between the smallest and the largest sample value [

54], which are evidence of fractal and self-similar processes. Other rules are generally psychological. On the other hand, one explanation of Zipf’s law is a law of least effort [

41], which restricts purposeful expenditure of negentropy, but, then, the similar physical law of least action [

41] is still much of a puzzle (pace R. Feynman, who suggested that quantum effects cancel out all vectors but one).

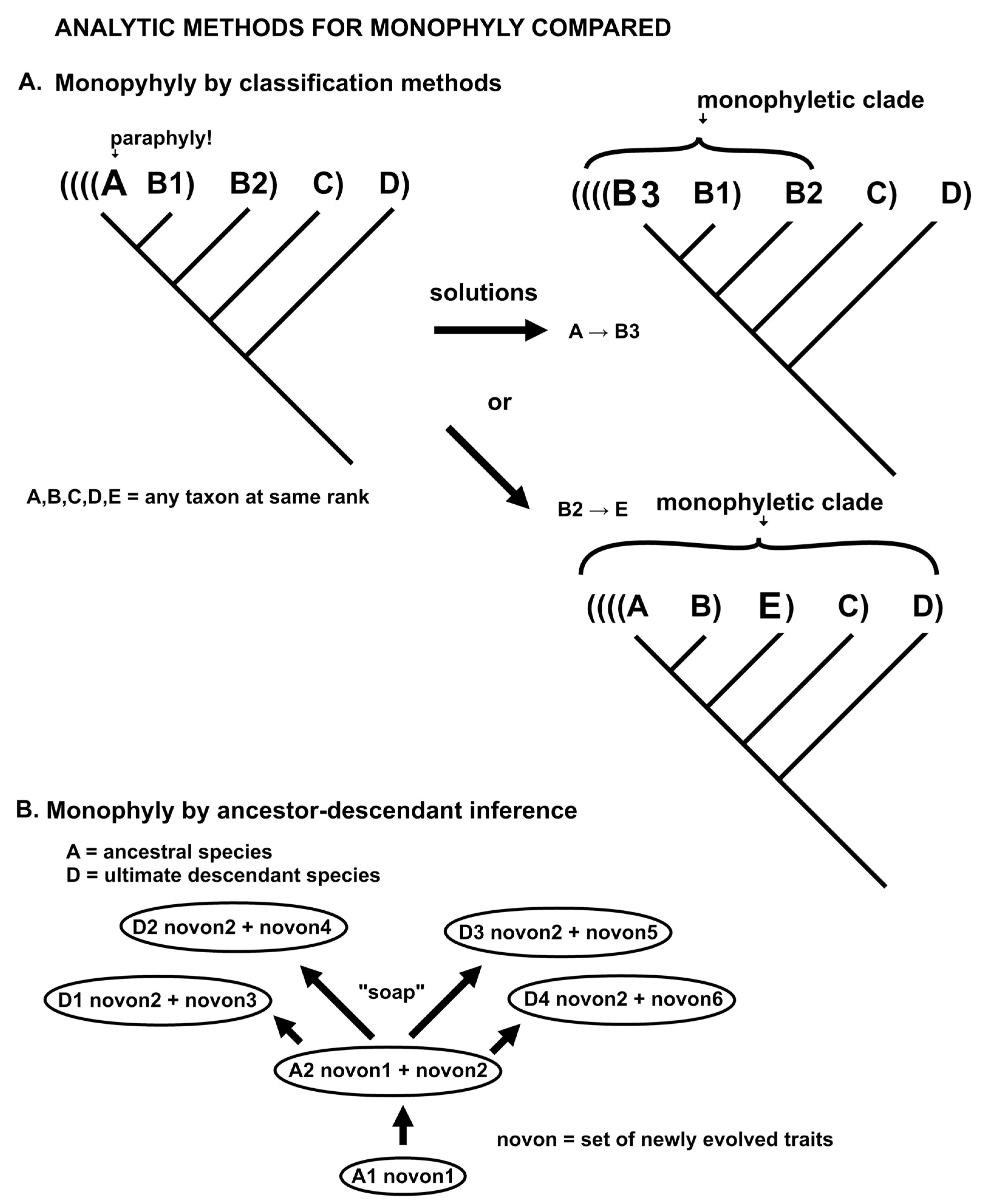

Some cladists treat cladograms as real things that may be directly observed rather than inferred [

55]. Clades form a nested hierarchy. A species may be paraphyletic (not monophyletic) if its definition excludes some morphological or molecular descendants, that is, if the ancestral population continues to be extant when some descendants are named a different taxon at the same rank. John Dewey [

56] p. 12 pointed out that “process,” as a universal, best embodied in modern natural science, is the “most revolutionary discovery yet made.” It replaces in philosophy such fixed and eternal absolutes as Being, Nature or the Universe, the Cosmos at large, Reality, or Truth. Dewey described a tension between those scholars with a fascination with sempiternal, immutable first principles and those with more pragmatic goals. This exists today, in my opinion, a similar tension with pattern cladists versus evolutionary taxonomists

The actual difference between taxa and clades is that

taxa are determined by trait changes between species modeling small bursts of speciation on a variously branching evolutionary model, while

clades are determined by trait differences between clusters on a dichotomous dendrogram, modeling evolutionary splits (or coalescence) of clusters on an optimally fully resolved cladogram. Clusters do not evolve and their analysis may be of the cladogram branching order not necessarily inferred evolution [

57]. The plausible evolutionary clustering of taxa on a cladogram is because evolution is such a powerful force that cluster analysis by any reasonable criterion results in plausible and apparently informative groupings. It is the fact that an enforced dichotomous tree cannot exhibit the distinctive patterns of taxa that the classification principle of holophyly is used to synonymize otherwise distinctive taxa into massive groups that are monophyletic in toto. The internal monophyly of minimally monophyletic groups (microgenera) is ignored as paraphyly.

The gradual replacement of taxon with clade, particularly in well-regarded list of accepted taxa, like the cladist-curated World Flora Online [

58], is also becoming common in vascular plant studies. The deprecation n in world-level online classification systems of many taxa, representing the results of long and tedious expert study of units of evolution in nature, cripples the understanding of biodiversity. I have pointed out that the minimally monophyletic group, one ancestor and a few immediate descendants, is the basic unit of resilient evolution [

5] and is a taxon, not a clade.

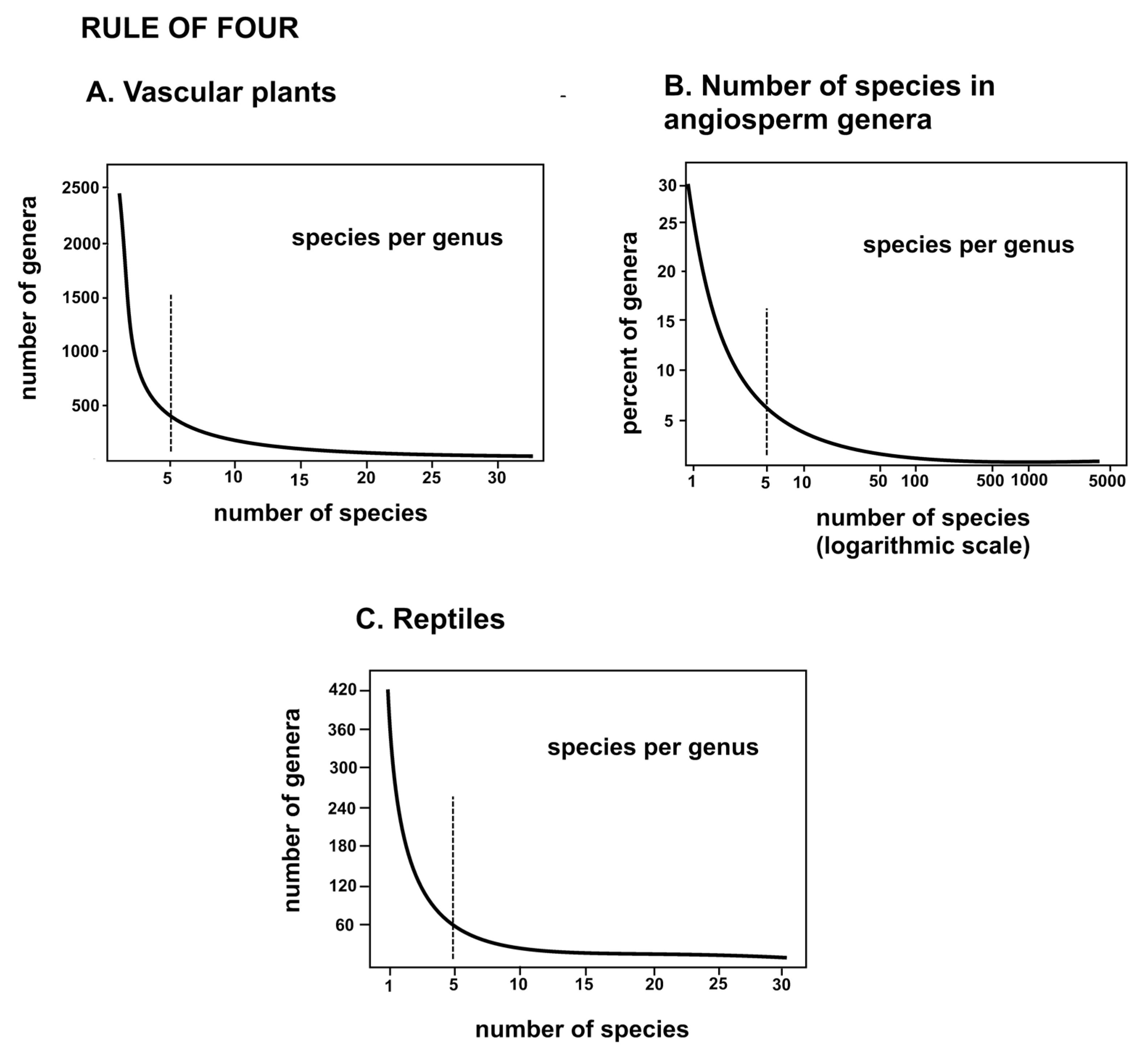

A suggestion for further study is that every process in nature that allows multiple elements to act as a unit leaves a power rule as evidence of the existence of that set of elements, in this case, taxa. Classical taxonomists have recognized these units, perhaps unknowingly, as demonstrated by the hollow curves in Fig. 2. It takes taxon familiarity and expertise to deal with evolution involving trait changes at the species level, but cladistic study is at least one step removed from examination of the process of evolution.

This section deals with paraphyly and its destructive effects. See discussion below for additional problems with cladistics analysis involving bad logic, modeling, sampling, and statistics.

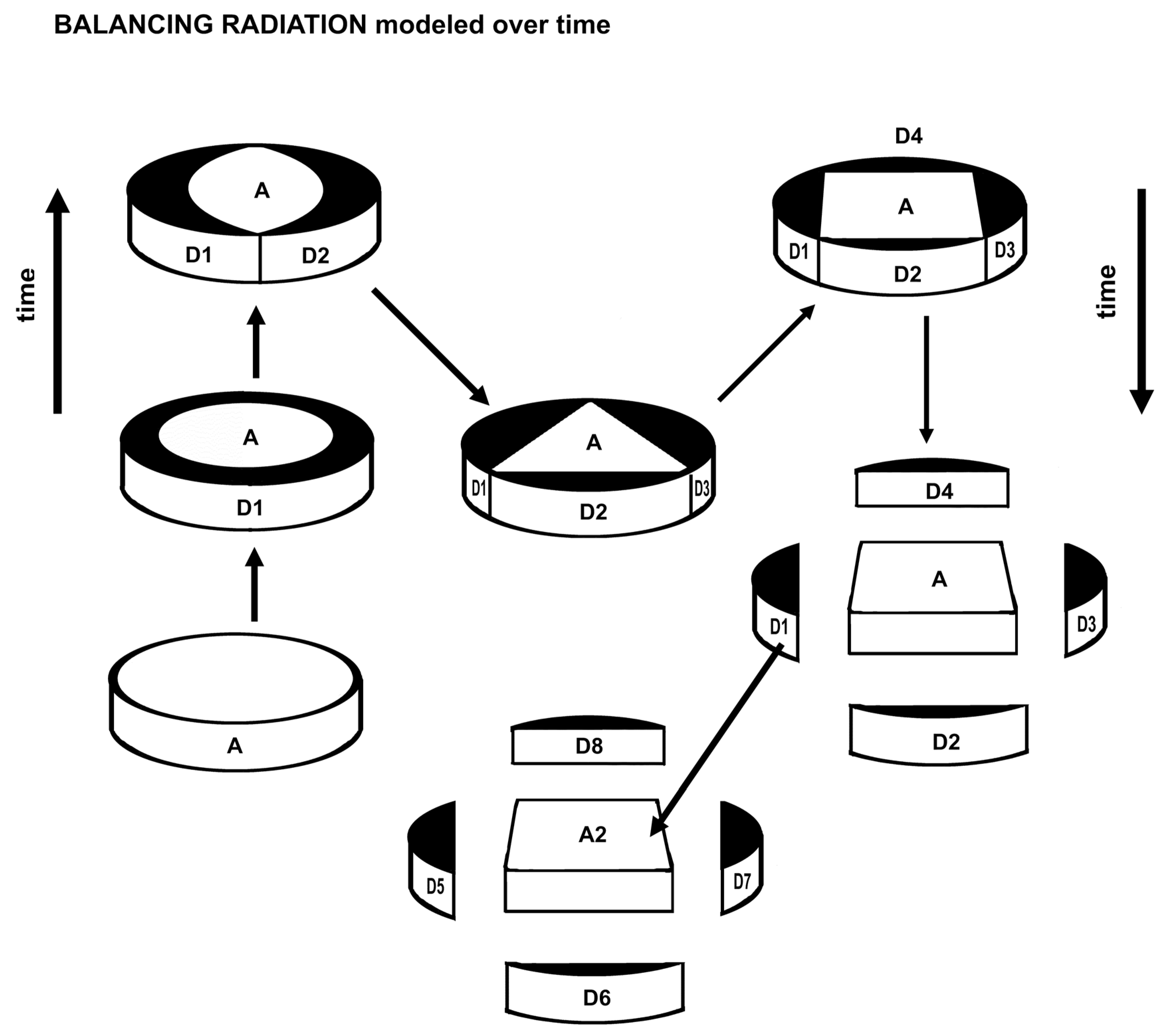

3.4. Peripatric Competition, Balanced Radiation, and Punctuated Equilibrium

A balanced radiation of one or two descendants may occupy up to half the area potentially held by the ancestral species. Regular polygons inscribed in a circle demonstrate rapid loss of potential habitat for increasing balanced numbers of descendant species occupying peripatric habitats without overlap with other descendant species.

More than five descendant species are liable to extinction by small size of available survival space (habitat, competition load, lack of mutualism). This model of balancing radiation provides a causal explanation for the fractal nature of evolution, where four products add to the generator to get the ratio 5:4, or a fractal dimension of 1.16 (log 5 divided by log 4), equivalent to the well-known Pareto distribution of 80:20.

This is the model with balanced distribution around a circle, but what about the periphery of a sphere? Externally, only two regular polygons can completely cover a sphere, viz. triangles and squares. Any genus then may generate a very few descendant species that balance each other in mutualism and competition. The above formulae do not involve squares (or cubes) and seem sufficient, however, to describe the effects of evolutionary processes in nature. Pentagons and regular polygons of more sides require additional, different polygons to completely cover a sphere. Penrose tilings can cover a sphere in an approximate manner but the areas of the two main tiles continue to approach the Golden Ratio of 1.618, that is, they remain unequal.

One might note that the soap analogy (Fig. 8) of new species in balance about half sympatric and half allopatric might apply to the realized niche, that is, the actual species in the somewhat slippery concept of a niche. The first colonizing species determines the nature of the survival traits and subsequent colonizers of different species match up their newly evolved traits while competing peripherally with geometric limitations on competition for size of survival areas. This assumes all species involved are about as similar as the descendant species of one ancestral species, that is, a shrub is not part of a geometrically affected realized niche of several mosses. No data is as yet available for this analogic hypothesis.

3.5. Sheaves of Hollow Curves

Numbers associated with statistics can be confusing. For a unimodal binary distribution (a bell-shaped curve), thirty samples are commonly considered sufficient to characterize that curve at 0.95 probability. This is because 95/100 is equivalent to 19/20, and information about the 1/19 of the distribution may be had with confidence if the numbers of samples were increased half-again from 20 to 30. This gives confidence in the known variability of the species.

A Shannon information bit represents halving the uncertainty. Each decision of which direction a trait has changed in evolution (i.e., as information of which species is ancestor and which descendant) is assigned one Shannon informational bit. The equation (4) shows bits

h(x) equal to the logarithm at base 2 of the inverse probability of

x, that is, of

P(x). Equation (5) demonstrates that for two alternative outcomes (two different trait change directions or probability 1/2), a decision on one of them yields one informational bit. Bits are additive and an odds table [

16] gives the Bayesian posterior probability that some one species is the descendant of the next.

This method of determining support is Bayesian because the statistical analysis is (1) second-order Markov chain, with support for the putative ancestor coming from both the matched primitiveness with the outgroup and it being more generalist than advanced traits of other species in the genus, and (2) it is sequential Bayes in which all bit assignments in a series may be added to derive a very high support measure for any length of concatenation in an evolutionary tree (i.e., as high an order of the Markov chain as there are n – 1 species, support being both backwards and forwards on the evolutionary dendrogram).

Five is an important figure in statistics because (1) bit distribution 1.0 to 4.3 (average) spans the first and second standard deviation of variation [

60] and (2) the “rule of five,” a rule of thumb which states that a random sample of five from a population will include, between the smallest and larges value, the medial (center value) of that population at 0.9375 probability [

54]. The upshot is that four descendant species, each with four new traits, have an excellent chance of efficiently addressing most of the contiguous allopatric habitat with adaptive traits. More descendant species and more new traits per speciation event may be superfluous and a burden on available survival-critical biomass and energy. Speculative? No. Empirical evidence for this explanation is present in the hollow curves of species per genus (Fig. 2) that are theoretically due to natural selection, while the worked out evolutionary skeletons are solidly articulated at the nodes. More work at this level is, of course, called for.

The empirical distribution of the evolutionary rule of four (four new descendants, four new traits) may be interpreted as dispersal of information. For a point source or stationary circle, measures of increases in information will involve unitary or fractional exponents. When a radius is increased, the circle enlarges and creates new information as a numeric square. The circumference of a circle inscribed or generated on a spherical surface increases with the radius half-way around, then decreases to a point on the other side. A saddle-shaped surface with frilly edges has the circumference increasing more rapidly as the radius increases. Areas associated with the periphery of the circumference increase with the square. Additional factors that affect rate and interspersal of peripatric generation and competition of descendant species include fragmentation by continents and islands, differential extinction, and serial compression by global glaciations. The devil is in the biasing context as we create information on geometric models as practical data sets relevant to analysis of natural processes. The rule of four signal seems to come through, however, both in the small (Fig. 1) and in the large (Fig. 2).

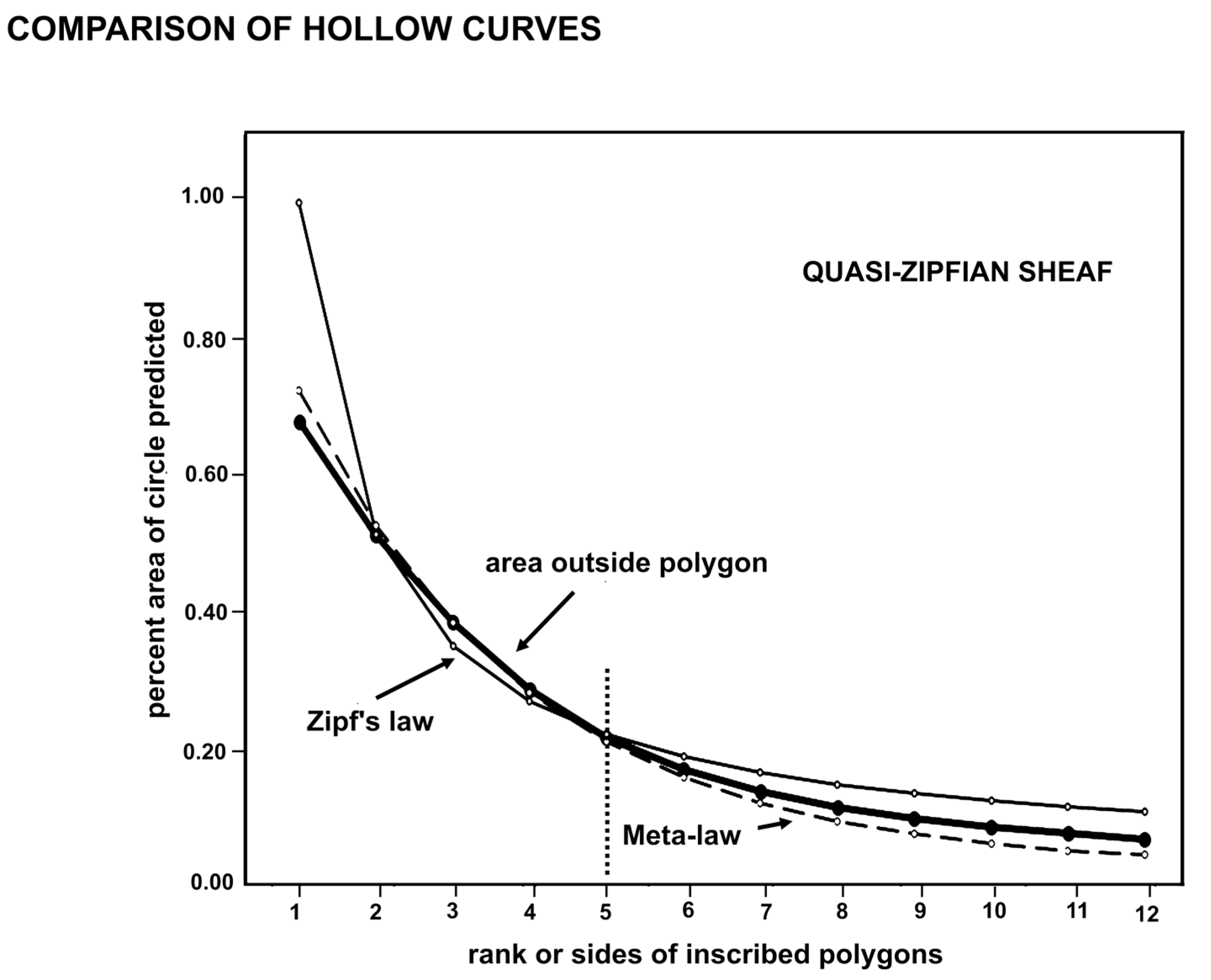

Using trendlines in MS Excel allowed characterization of the curves in Fig. 5. The curve for the Zipf’s law is clearly a power rule, matching the Excel trendline for power. The other hollow curves are exponential for higher values on the y-axis with values near one, but follow a power law in the tail, which together is apparently common in empirically derived curves found by “best fit.”

The close association of the hollow curves in Fig.5 may be interpreted in different ways. The curves could be each an approximation of some one basic curve that rules them all, or they could be each valid and accurate descriptions of the results of several closely related processes in nature. The second explanation is attractive and fits the modern recognition that there may be different but equally valid explanations for similar natural phenomena. This is why one searches for a best fitting curve rather than some obvious single solution. The hollow curves are integrated summaries of how the rule of four has constrained minimally monophyletic units over 88-million years of biogeographical modification of the modern flora. Certainly there are different rules for observed features of the quantum microcosm, Newtonian mesocosm, and Einsteinian macrocosm, while wave and particle observations are problematically explained as a single process, and the Theory of Everything remains obdurately hidden.

I suggest that—if there is a single formula that explains evolutionary information adequately, it will involve wrinkles in informational space-time. By this I mean that the informational context affects the description of the results of the process in nature. Just as inscribing a circle on a sphere or on a negatively curved surface (a saddle) must modify the exponent (assuming no change in the constant π) the geometric models may suffer from the confounding effects of inconstant Reality. For this reason, I suggest that the sheaf of curves in Fig. 6 reflects a conclusion that evolution is quasi-Zipfian, and describable only with Zipf-similar formulae, including the meta-law formula of Constantin et al. [

42].

Power law and exponential descriptions of the results of processes in nature may be traced to one feature, the dispersal of created information with increasing radius from the center. Speciation is a perfect example of creation of information around the periphery of an originating source, with increasing information, to get an exponent of minus one if information increases with no increase in radius, 2 if area, 3 if volume, 4 if an additional dimension is considered. All variables that are needed to give best fit to the data reflect the different contexts in nature, or wrinkles in informational space-time. The several hollow curves, both exponential and power law (depending on Excel trendline matches) are the informational bones of the skeleton of evolution, and all explain or at least reflect, variously, the Rule of Four in speciation.

3.7. Methods of Evolutionary Analysis and Classification

Critiques of scientific methods are generally ineffective unless an alternative, better method is offered. I have described, as macroevolutionary systematics, such an alternative in detail in several previous publication. It is new science but, like traditional cladistics, is based on numerical taxonomy. Essentially, it is high-resolution phylogenetics. Phylogenetics may be defined as studying the evolutionary relationships of organisms with numerical techniques, particularly of statistical support for dendrogram branches, reflecting its origin in computational systematics. Cladistics is the classification of organisms by shared derived traits, implying common ancestry of clusters. Phylogenetics is commonly identified with cladistics, however, there are other methods of inferring evolutionary relationships in a computational context. High resolution phylogenetics infers relationships of organisms by ancestor-descendant trait changes between species, emphasizing descent with modification, focusing on connections between minimally monophyletic groups.

The protocol, in short, is as follows: Morpho-species are segregated into small, closely related groups using any standard hierarchical method, limiting the relative data sets so as to minimize the effect of convergent traits. Genera are identified as (1) minimally monophyletic groups with one ancestral species that is most similar to the outgroup and also least generalist among the ingroup, (2) the newest traits of the ancestral species are found reproduced in each of the descendant species, and (3) there are usually up to four immediate descendant species in each genus and about four new traits in each species (4) a maximally parsimonious (maximum informational entropy) dendrogram is produced, which is a multichotomous tree with extant or inferred ancestral species at the nodes (a caulogram). Statistical support is through Turing-Shannon sequential Bayes using one bit per new trait on a second-order Markov chain.

The branching concatenation of ancestral species provides a monophyletic evolutionary skeleton to larger monophyletic groups. Confirmation of the morphological skeleton is presently by identification of paraphyletic species on molecular cladograms, which are presumed to be ancestral to other species. This has been proven true in a study of the moss clade

Chiololoma [

5] (Zander 2024e). One may hope that future molecular analysis using caulograms will provide more information. Mapping of morphological traits to molecular cladograms is now unnecessary.

This recasting is a major fix for the traditional methods of cladistic systematics, which is a 50-year-old technology. Originally, a cladogram was described as simply a branching network of ancestor-descendant relationships [

61] p. 28. Cladistics presently focuses only on estimated order of branching not order of taxa, and the former supposedly identifies common ancestry. It rejects ancestor-descendant analysis by suppressing information from any paraphyly, morphological or molecular. Hörandl [

62] has pointed out that commonly used sequence markers are limited to grouping evolutionarily, while expressed morphological traits that contribute to structure and function are deeply involved in selection, adaptation and co-evolution, and thus may be the proper bases for evolutionary grouping in classification. The classical morphological taxonomic method is based on hard-won informal genetic algorithms resulting in well-tested heuristics commonly known as expertise [

63,

64].

It is uncomfortable to suggest that cladistics is fundamentally anti-evolution [

57]. The PhyloCode [

65] glossary defines “phylogenetic” as of or pertaining to the history of ancestry and descent.” Abundant evidence in cladistic publications, however, suggests that cladism suppresses any suggestion of descent with modification, that is, of ancestor-descendant transitions between extant species, although lip service is paid to “common ancestry.” The fact is that evolution, either gradual or by short jumps of a few traits per speciation event, has so powerful an effect for grouping by similarity that any cluster analysis by any reasonable criteria will generate evolutionarily somewhat coherent groups. Without close analysis of ancestor-descendant changes at the species level, both morphological and molecular, cladistic study results in poor resolution of monophyly and large genera as clades bloated with holophyletic synonymy. Evidence that cladistics rejects or strongly minimizes evidence of descent with modification includes the following, to a great extent corrected in the new high-resolution phylogenetics:

1. A cladogram, as an enforcedly dichotomous dendrogram, cannot exhibit the distinctive multichotomous patterns of the little ancestor-descendant bursts of speciation characteristic of evolution. A cladogram originated as a visual aid to sorting out the nested parentheses of cluster analysis.

2. A cladogram does not have extant taxa assigned to an internal node, even though about half of all species are ancestral to other species. Determining common ancestry of bursts of 1 to 4 descendant species as pairs of taxa is fraught.

3. Phylogenetic analysis is restricted to a narrow form of eliminative induction, asking the question “which cladogram best explains the data?” not “which of any reasonable tree is optimal.” The “black box” of massively incomprehensible statistics (to the average taxonomist) obscures this essential bias.

4. The terms ancestor and descendant have been replaced with “paraphyletic” and “apophyletic,” respectively. These latter terms describe positions of nodes on the cladogram, not evolution.

5. Analysis with first order Markov chain on a dichotomous dendrogram selects optimal sister groups, that with second-order Markov chain on a multichotomous dendrogram selects optimal ancestor-descendant sets.

6. Clades have little value in floristic studies. A clade consisting of a paraphyletic species or genus plus all descendant species or genera has no or a much diluted evolutionary trajectory, characteristic ecology, or value in biodiversity study.

7. A large number of randomly sampled exemplars of a species can reveal the molecular paraphyly to identify an extant ancestral species. Looking for paraphyly as evidence of descent with modification is not a goal, however, even though funds for adequate sampling are abundant.

8. Rather than follow the PhyloCode [

65], clades are named as taxa although clades are not taxa. A

taxon is a set of organisms distinguished by expert evolutionary taxonomists intimately familiar with the group, its variation and ecological features. A taxon consists of organisms very similar in overall homologous traits, generally evinces a morphometric gap or distance, and seems to have a unique evolutionary trajectory. As presented here, a genus is the fundamental unit of resilient evolution [

5], defined as a minimal monophyletic group of one ancestral species and a few (ca. 1–4 immediate descendants) and exhibiting a rule of four (optimally four descendant species, all species with mostly four new traits). Given the fractal nature of the genus, self-similarity is evident at all other taxonomic ranks, species and families [

19] (Zander 2023). A species is a set of organisms describable by any of the usual definitions of species as long as such species can participate in evolutionary lineages in a minimally monophyletic genus.

A

clade is defined in the PhyloCode [

65] Art. 2 as “an ancestor (an organism, population, or species) and all of its descendants.” A clade differs from a taxon in its modification to follow the classification principle of holophyly, usually in practice of a paraphyletic species, genus, or family being merged with any apophyletic (descendant) taxa of the same rank. A taxon is an evolutionary unit, a clade is commonly a composite of more than one evolutionarily distinctive taxa. The moss family Pottiaceae Hampe is now a clade [

58] in the influential World Flora Online having been merged, because of paraphyly, with descendant families Cinclidotaceae Schimp., Ephemeraceae J. W. Griff. & Henfr., Splachnobryaceae A. K. Kop., Streptotrichaceae R. H. Zander. The pottiaceous genus

Syntrichia Brid. is now a clade because it has been stuffed with the well-established taxa

Calyptopogon (Mitt.) Broth.,

Dolotortula R. H. Zander,

Sagenotortula R. H. Zander,

Streptopogon Wilson ex Mitt., and

Willia Müll. Hal., and all their species were transferred [

66] to combinations in

Syntrichia. There are many other examples of clades presented with taxon names.

The Phylocode recommends (Rec. 6.1B) that the letter “P”, bracketed or in superscript, be used to designate clade names and the letter R used for rank-based names. Thus the taxon Pottiaceae, when appropriate would be addressed as Pottiaceae[R] but as a clade it would be Pottiaceae[P], If treated as both a clade and a family in the same publication, they should be clade Pottiaceae versus family Pottiaceae. I have not seen this done, and clades abound in the taxonomic literature that are not identified as such. The difference in biotic significance may be immense between a clade named as family, genus or species and a taxon named as family, genus or species.