1. Introduction

African swine fever is an important, infectious, hemorrhagic disease of domestic and wild pigs that can have a case fatality rate of up to 100%. It was first described more than 100 years ago [

1] and is caused by African swine fever virus (ASFV), the sole member of the

Asfarviridae [

2]. The virus particles are large (ca. 200 nm in diameter) and complex with a dsDNA genome of 170,000-190,000 bp (depending on the strain) and the multi-layered virions contain over 60 different viral proteins plus about 20 host proteins [

3].

Multiple genotypes of the virus are known to exist within Africa [

4], this classification is based on the DNA sequence of the VP72 coding region. Although initially identified within Africa, there have been several instances of virus spreading out of Africa. In the 1950’s, a genotype I virus caused disease within Spain and Portugal initially but also spread into Italy (Sardinia) and the Americas (e.g. Cuba and the Dominican Republic) [

5]. More recently, a genotype II virus entered Georgia (in the Caucasus) in 2007 and has spread from there into Asia (including China (the world’s largest pig producer), Vietnam and South Korea), across Europe and also into the Americas (Dominican Republic and Haiti), affecting on a global scale, 62 countries since 1

st January 2022 [

6]. The disease continues to have a severe economic impact within many of these countries.

Within Europe, the virus has been spreading mainly among wild boar but sometimes spillover into domestic pigs has also occurred. The virus is readily transmitted by direct contact between infected and uninfected animals [

7,

8]. However, in addition, transmission by indirect routes in contaminated feed or other objects has occurred (reviewed in [

9]). This is consistent with the “long distance” jumps of the virus, which are believed to have occurred due to human involvement [

10,

11]. ASFV can be present at high levels within the blood of infected animals [

7,

8,

12] and virus survival seems to be enhanced within blood [

13]. Serum has also been reported to have a stabilizing effect on the virus [

14,

15]. Furthermore, hematophagous insects (e.g. stable flies,

Stomoxys calcitrans) can take up the virus in blood meals from ASFV-infected pigs [

16,

17,

18] and spread it, by mechanical transmission, potentially into pig farm premises with high biosecurity [

19,

20]. Note, in eastern and southern Africa, ASFV can be transmitted via a sylvatic cycle involving soft ticks (

Ornithodorus spp.) and warthogs [

21] but the relevant soft tick species are not present within northern Europe but, even in their absence, extensive spread of the virus, e.g. in the Baltic states, Poland and Germany, has occurred [

11,

22].

It is apparent that indirect routes of virus transmission are critically dependent on the stability of the infectious virus in the environment as well as on the susceptibility of pigs to infection by oral uptake. Typically, the presence of virus within materials, e.g. feed and bedding, is assessed using either infectivity assays in cultured cells, which can be challenging due to the presence of potential contaminants, or by quantitative PCR (qPCR), which does not distinguish between infectious and non-infectious virus.

In previous studies, Dee et al. analyzed the survival of ASFV in feed ingredients and found a half-life of 1.3 to 2.2 days in a variety of different materials during a modelled transportation study. Samples that were still qPCR positive for ASFV but negative by virus isolation assays were also tested in a bioassay using intramuscular inoculation of pigs. It was found that this bioassay was able to detect residual virus infectivity in such samples [

23]. Analogous results have been observed from the analysis of different dried cured meat products from ASFV-infected pigs. Oral administration of these products to pigs resulted in infection, even when the same products tested negative for infectious virus using cell culture systems [

24]. Other studies have identified differences in the minimum infectious dose of the virus when administered to pigs in solid or liquid materials by the oral route [

25]. Much lower doses of ASFV were found to be able to initiate infection in pigs when in liquid rather than solid form.

In this study, an assay combining qPCR and cell culture based methods to assess the infectivity of samples potentially contaminated with ASFV has been used to assist with determining the influence of common farm materials, which may be contaminated with ASFV, on the survival of the virus under different conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

Closed Eppendorf tubes containing one of four different matrix materials as well as virus inoculation material were incubated for pre-determined lengths of time at different temperatures (in the range of 5-70 °C). Two replicate samples (A and B) for each combination of material, time and temperature were prepared (see

Table 1). At the pre-selected times, samples were removed from incubation, quickly put on ice, and stored at -80 °C.

2.2. Virus Inoculation Material

A pool of serum from four pigs that had been experimentally infected with ASFV/Podlaskie (as described in [

26]) was made and diluted 1:10 with normal (uninfected) pig serum. The undiluted pool had a Ct value of 20.0 in the ASFV DNA qPCR and a virus titer of 6.05 log

10 TCID

50/ml and, after dilution, the Ct value was 23.1. For each sample tube, 500 µl of this diluted serum pool was added to 50 mg straw or 100 mg of the other matrix materials or to an empty tube (positive control).

2.3. Incubation Matrix Materials

Four different matrix materials were chosen and collected from a pig farm in Denmark. The materials were: barley straw (local production, Denmark) finely chopped to fit into the sample tube; fine wood shavings (Vida strö, Sweden); sow feces and mixed dry feed (designed for weaning pigs in the age group of 4-6 weeks (optimized by feed consultant)). The mixed and finely ground meal feed consisted of 37.95 % wheat (local production, Denmark), 30 % barley (local production, Denmark), 17.3 % feed mix concentrate (for weaners), 8.85 % soya meal (AlphaSoy™ 530, AB Neo Denmark), 2.9 % technical pork fat SF92/15, 2% sugar beet pulp pellets, 1.5 % feed enzyme mix Porzyme® tp 100.

2.4. Sample Processing

Samples were processed, after incubation, to enable assessment of the presence of infectious virus. To each sample tube, two 3 mm stainless steel balls (Dejay Distribution Ltd., Launceston, UK) plus 500 µl of MEM 10xanti were added (in-house recipe using 500 ml of Minimum Essential Medium with Earle’s salts and L-glutamine (MEM, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with 1 ml of penicillin, 1.7 ml of amphotericin and 12.5 ml of streptavidin/neomycin, as added antibiotics (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)). The samples were homogenized in a TissueLyser II (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) at 25 Hz for 2 min. and then centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 5 min. The supernatants were passed through 0.45 µm sterile filters (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) into new Eppendorf tubes.

2.5. Virus Nucleic Acid Detection

Aliquots of the filtered supernatants (100 µl) were added to 250 µl MagNA Pure External Lysis Buffer and nucleic acids were extracted using the MagNA Pure 96 robot (Roche, Basel Switzerland) with the DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit and an elution volume of 50 µl. The ASFV DNA was detected using qPCR as described previously [

14,

27].

2.6. Assessment of ASFV Survival

Filtered samples were assayed for the presence of infectious virus by inoculation into primary cells, followed by identification using an immunoperoxidase monolayer assay (IPMA) essentially as described previously [

8,

28,

29]. In brief, the filtered homogenates (100 µl filtrate + 100 µl MEM with 10xanti) were added to porcine pulmonary alveolar macrophages (PPAM) (1.6 x 10

6 cells in 1 ml of medium containing 5 % fetal bovine serum (FBS)), in NUNC 24-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific), incubated for 3 days at 37 °C (with 5% CO

2) and then frozen (at -80 °C) (1

st blind passage). Thawed and mixed whole cell harvests (50 µl) were used to inoculate individual wells in a NUNC 96-well plate of PPAM (with 100 µl of medium with 1.6 x 10

5 cells per well) for IPMA (as above). Stained cells were identified under the microscope, taking care not to score stained monocytes as positive as these can retain color in the absence of virus. Samples indicating positive results in the IPMA (called “2

nd passage staining”) were subsequently titrated, when appropriate, using 10-fold dilutions in MEM, starting afresh from the sample filtrates and stained using 1

st passage PPAM in the same assay.

2.7. qPCR-Based Virus Infectivity Assay

To assess any increase in the level of viral DNA during the blind passaging in PPAM, selected filtered sample homogenates were 11-fold diluted in MEM (100 µl filtrate in a total of 1.2 ml volume as for the passages), and nucleic acids were extracted from 100 µl of this dilution and tested for the presence of ASFV DNA using the qPCR assay (as in section 2.5). The results were compared with similarly tested extracted nucleic acids present in samples of harvested first passage material (obtained using 100 µl filtered homogenate with 1.1 ml of MEM with PPAM) after 3 days of incubation at 37 °C. After freezing/thawing, as for the initial homogenate, 100 µl from the cell harvest was used for the nucleic acid extraction. A decrease in Ct value of at least 2 (ca. a 4-fold increase in target DNA) was considered to be positive. Note, for samples scored as negative, an increase in Ct value was often observed in the passaged material indicative of DNA degradation during incubation.

2.8. Visualization of Data

Graphs were prepared in GraphPad Prism version 10.2.3 for Windows (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts USA,

https://www.graphpad.com). Final figures containing two or more graphs were subsequently assembled and labelled using BioRender under an academic publication license (

https://app.biorender.com/).

3. Results

3.1. Pilot Studies

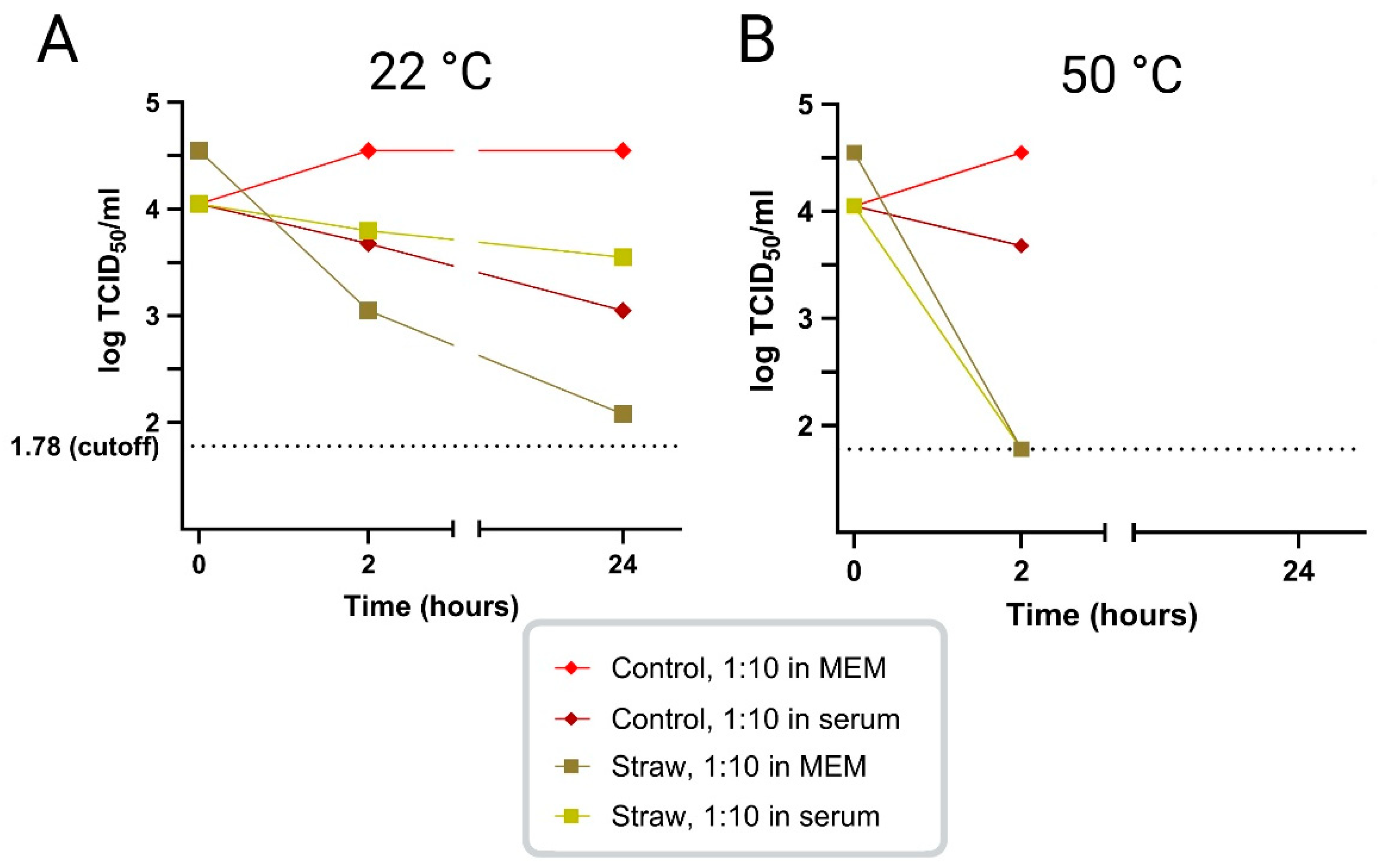

In an initial study, the survival of ASFV infectivity in virus-positive porcine serum, diluted 1:10 in MEM or in ASFV-negative porcine serum, was tested at two different temperatures, namely 22 °C and 50 °C, in the presence or absence of straw. At 22 °C, it was found that the virus survived well, for at least 24 h, in MEM, in the presence or absence of serum. The addition of straw, in the 1:10 dilution of virus positive serum in MEM seemed to reduce virus survival but the presence of high levels of serum (100%) seemed to mitigate this effect (

Figure 1 A). At a higher temperature, 50 °C, virus survival was little changed after 2 h but was markedly shortened in the presence of straw, however, no major difference was seen between the virus diluted in MEM vs. serum (

Figure 1 B). Based on these results, it was decided to perform the subsequent studies using porcine serum from ASFV-infected pigs diluted 1:10 in normal porcine serum instead of MEM.

3.2. Analysis of ASFV Survival in Spiked Samples Under Different Conditions

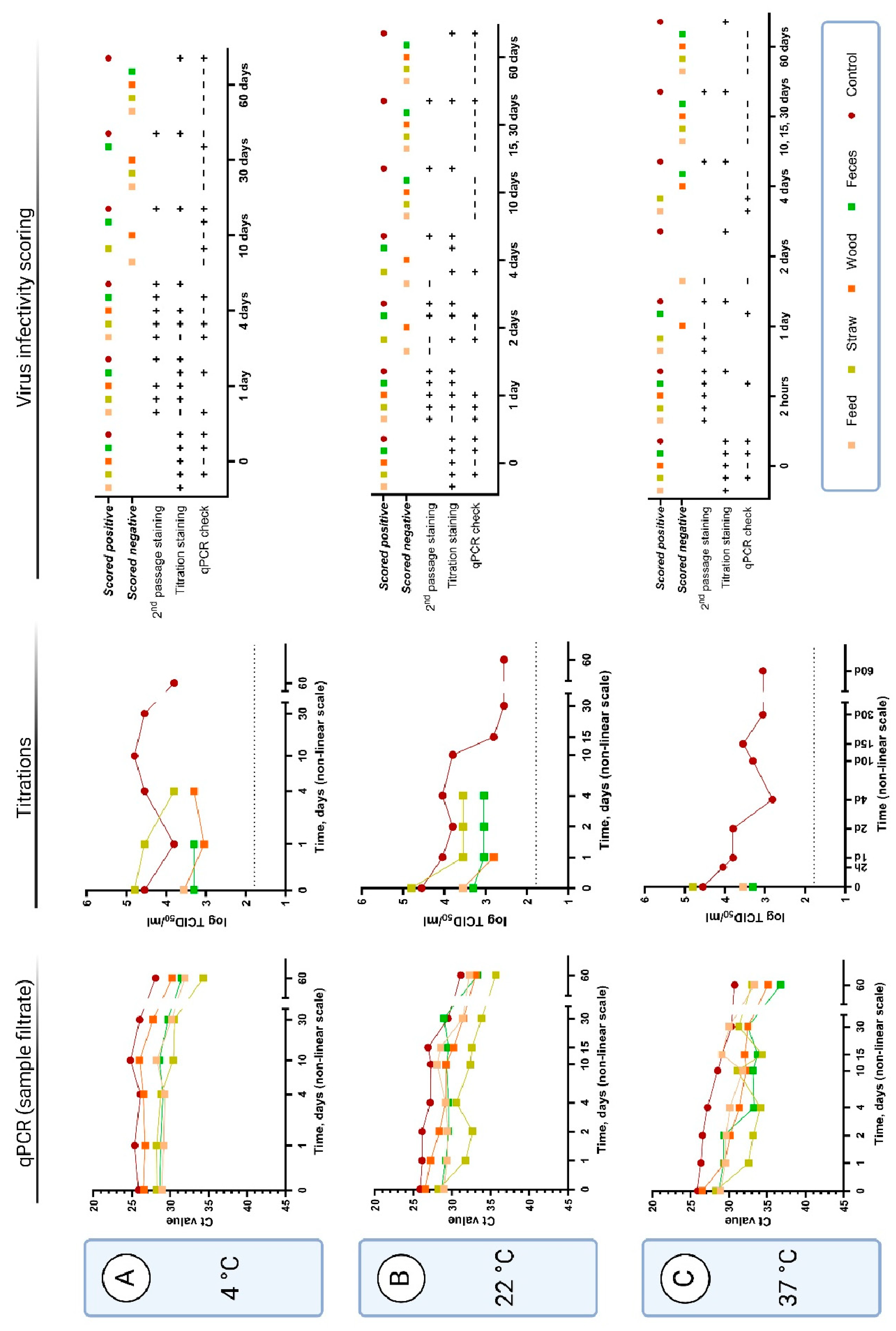

In all the following studies, 10x diluted pooled serum samples from ASFV-infected pigs were added to tubes alone (“positive controls”) or with feed, straw, wood shavings, or pig feces and incubated for the indicated times in closed tubes at different temperatures. Following these incubations, samples were assayed for the presence of infectious virus (using primary cells with detection of ASFV antigen staining/IPMA) or for the presence of ASFV DNA (by qPCR).

An assay combining cell-based assays with qPCR to assess the presence of infectious ASFV, termed the qPCR infectivity check, was also performed on selected samples to assist with the scoring of samples that were difficult to assess by antigen staining. The assay involved adding the filtered, treated samples to PPAM and, following incubation for 72 h at 37 °C, comparing the level of ASFV DNA in the initial filtrate and in the cell harvest. The presence of infectious virus was indicated by increased levels of ASFV DNA (for clarity, a decrease of at least 2 Ct was used to define virus replication, see

supplementary file S1). Using this assay, in combination with staining, the different sample categories could be scored as either negative or positive for the presence of infectious virus (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). For all but one of the performed qPCR checks with the samples treated with wood shavings, the infectivity results were negative or inconclusive (decrease in Ct value less than 2). For the other types of samples, qPCR checks were positive at low temperatures and at initial time points but became negative at different points through the course of the experiment – as may be expected.

3.2.1. Virus Survival at 4 °C

At 4 °C, the positive control sample (diluted serum with no added material) was found to contain infectious virus for at least 60 days, this was observed using both the conventional cell staining assays and the qPCR infectivity check assay (

Figure 2 A, second and third columns). Virus infectivity was also observed and could be measured as titers in the cell staining assays after incubation for 4 days in the presence of straw and wood shavings but only for 1 day in the presence of feces. Beyond these time points, the samples generated too much background in the cells to be readable. However, using the qPCR infectivity check assay, it was possible to detect virus infectivity in the samples incubated for at least 30 days in the presence of feces, for 10 days in the presence of straw and for 4 days in the presence of feed. Infectious virus was not detected with the qPCR check at this temperature for any of the tested incubation times in the presence of wood shavings even though cell staining was observed.

The stability of the ASFV DNA in these samples was also assessed using a qPCR assay on the sample filtrates (

Figure 2 A, first column). It was found that the level of ASFV DNA detected in the samples was little changed over a period of up to 30 days in the positive control and also in the presence of exogenous materials (feed, straw, wood shavings or feces). However, a marked decline in the level of viral DNA detected was apparent in all samples at the next sampling time, which was after 60 days of incubation.

3.2.2. Virus Survival at 22 °C

ASFV, in the positive control, retained infectivity for PPAM, following incubation at 22 °C, for at least 60 days as judged by the cell staining assay (

Figure 2 B, second and third columns). In the presence of straw and feces, then infectivity could be detected until only 4 days of incubation. For feed and wood, infectivity was only detected for samples incubated for up to just 1 day. ASFV DNA was readily detected, by qPCR, in all sample filtrates following the 60 days incubation (

Figure 2 B, first column).

3.2.3. Virus Survival at 37 °C

At 37 °C, the virus infectivity measured in the cell staining assay could be detected in the positive control after 60 days of incubation (

Figure 2 C, second and third columns). However, even after 30 min. of incubation at this temperature, with any of the exogenous materials tested, then it became impossible to read the cell staining titration assay with certainty. In contrast, it was possible to observe infectivity in the qPCR infectivity check assay after incubation of the samples containing feed or straw for 4 days and after 24 h in the presence of feces. The sample containing wood shavings was only scored positive up until 2 h of incubation. ASFV DNA could be measured by qPCR in all the samples even after 60 days incubation (

Figure 2 C, first column).

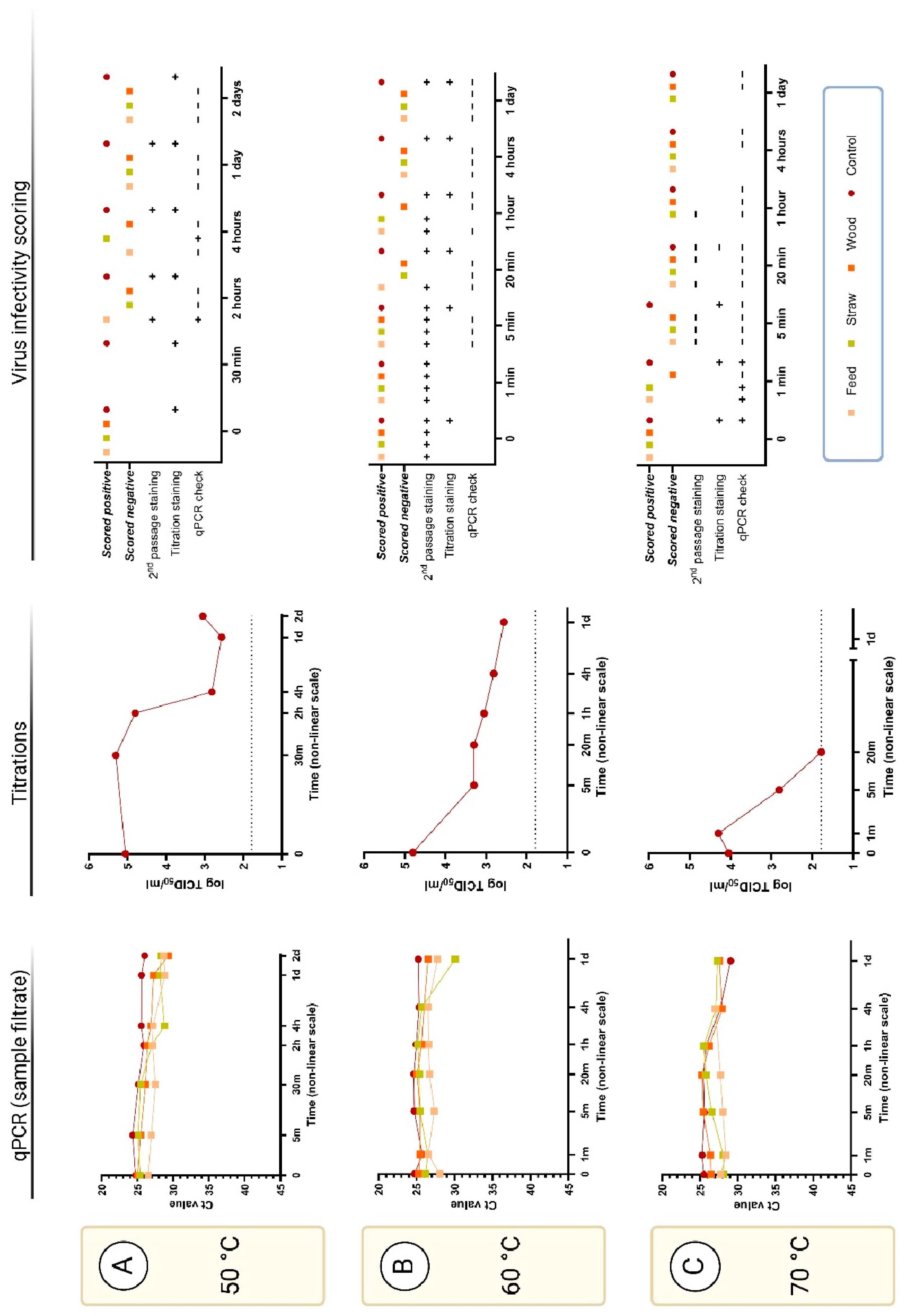

3.2.4. Virus Survival at Elevated Temperatures (50-70 °C)

The positive control sample contained infectious ASFV after incubation for 2 days at 50 °C (

Figure 3 A). However, no clear evidence for the presence of infectious virus could be obtained using the cell staining assays in the presence of any of the exogenous materials, except for feed, even after 2 h incubation at this temperature. On the other hand, virus replication could be detected by the qPCR infectivity check assay from the sample containing feed incubated for 2 h and straw for 4 h (

Figure 3 A, second and third columns). All samples incubated at 50 °C for up to 2 days contained readily detectable ASFV DNA (

Figure 3 A, first column).

Judging from the cell staining assays, ASFV infectivity was also retained in the positive control sample after incubation at 60 °C for 24 h. Blind passage staining also indicated infectious virus in the samples with feed and straw for up to 1 h of incubation at this temperature, and with wood only for 5 min. However, there was no evidence for virus infectivity for any of the selected and tested samples incubated at this temperature – including the control at 24 h in the qPCR infectivity check assay (

Figure 3 B, second and third column). Note, samples containing fecal material were not incubated at 60 or 70 °C.

Virus infectivity, judged by cell staining, was still observed from the positive control after 1 or 5 min. incubation at 70 °C but was lost after 20 min. incubation (

Figure 3 C, second and third column). Furthermore, the samples started coagulating after this time point due to the high serum content, which made it impossible to process. In the qPCR infectivity check assay, virus replication could be observed from the positive control as well as from the samples containing feed or straw after 1 min incubation but not after 5 min. The presence of ASFV DNA was again readily detectable in all samples tested after up to 24 h incubation at 60 or 70 °C (

Figure 3 B and C, first column).

3.3. Results Summary

The latest detected time points for virus survival for each sample category, after incubation at the different temperatures were plotted for an overview of the different virus survival experiments (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

A novel combination assay has been used here to assess the survival of infectious ASFV following incubations under different conditions. This combination assay includes a so-called “qPCR check” based on measuring the production of ASFV genomic DNA within PPAM (akin to the qPCR check assay described for assessing porcine parvovirus infectivity [

33]). Although this system may not appear to be very different from only using staining for ASFV antigens produced within infected PPAM, the qPCR check is less affected by some contaminants/chemicals within the virus samples that cause a high background during the antigen staining procedure. In multiple cases, the qPCR check assay demonstrated its ability to detect infectious ASFV under conditions when it was no longer possible to evaluate infectivity in the antigen staining assay, e.g. for feed and straw samples incubated for 4 days at 37 °C (see

Figure 3 B, third column). Furthermore, the qPCR check provides a measurable result (Ct difference between qPCR tests of specific nucleic acids in diluted sample filtrate and cell harvest material) in contrast to individual judgement when reading cell staining assays.

The use of these assays in combination also overcomes the major issue with the usual qPCR assays that only detect the presence of the ASFV DNA irrespective of whether this DNA is present within infectious virus or not. It is particularly noteworthy that following high temperature treatment of virus containing samples, that the signal for the presence of ASFV DNA in the sample filtrates was well maintained using the qPCR assay while the infectivity of the samples was destroyed (see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Thus, the qPCR assays alone are not suitable for assessing the risk posed by materials contaminated by ASFV.

Using these assays, it was possible to assess the duration of ASFV infectivity survival at different temperatures and in the presence of different exogenous materials. Each of the materials tested (feed, straw, wood shavings and feces) had a negative impact on the survival of ASFV (see

Figure 4) throughout the temperature range that was tested. It could be speculated about how these materials may cause these effects. The following considerations may be relevant: 1) the feed contains acidic substances (the medium turned yellow); 2) the straw probably contained molds; 3) the wood produced the most adverse effects perhaps because of tannins or other chemicals reacting with the virus and/or affecting the cells; 4) the feces were surprisingly benign for the cells and the virus, allowing detection of infectious virus after incubation for up to 30 days at 4 °C in our study in comparison to previously reported survival of up to 8.5 days in feces samples from experimentally infected pigs stored at the same temperature [

34].

In stability experiments performed at five different temperatures between -20 °C and 37 °C using plant-based materials, Blome et al used similar titers and volumes of virus (in EDTA-stabilized porcine blood spiked with virus). However, the matrix materials were of much larger quantities (e.g. 15 ml of grain and 15 g of straw) and it was difficult to recover infectious virus from the samples, while the presence of ASFV DNA was readily determined [

35]. In our studies, on the other hand, we were able to recover infectious virus from our samples for days instead of hours at these temperatures, which could, in part, be due to the lower amounts of matrix materials in each spiked sample. In another stability experiment, in which a larger volume of field crops (20 g wheat, barley, rye, triticale, corn and peas) were spiked with blood (ASFV titer of spiking material was 10

6 HAD

50/ml) it was also found that it was very difficult to recover infectious virus from dried and heat-treated crops. Hence, even after only 2 h drying at room temperature, infectious virus could not be detected in the spiked feed material using virus isolation in primary porcine cells. In line with our study, ASFV DNA was readily detected in dried and heat-treated virus spiked crops suggesting high stability of ASFV DNA after heat treatment [

36]. Interestingly, virus survival at elevated temperatures was markedly increased for control samples (serum) in the current study, compared to the control samples (blood) in the previous study [

36]. In blood controls, infectious virus could only be detected for up to 1 h at 50 °C and not after heat treatment at 55 °C [

36], while we still detected infectious virus in serum controls after incubation for up to two days at 50 °C, one day at 60 °C and ≤ 5 min. at 70 °C.

The collection of chosen materials and the scale of this study was not meant to make up an exhaustive investigation into all potential fomites relevant for ASFV transmission. Rather, it was meant to be the base-line for further studies with an assessment of virus infectivity using sensitive and specific assays. Optimizations could be made in the future to the “qPCR check” assay to enhance accuracy. For example, setting up dilutions of the filtrate for nucleic acid extraction completely in parallel with passaging the filtrate, instead of performing it within two separate workflows, as was done here.

It is worth noting that there were several limitations in these studies. Only two replicates were made at each combination of time, material and temperature, and most often, only one of the replicates was analyzed, while the other was kept as a backup. However, it could be argued that since these samples were from time-course experiments, then closely connected sample times are semi-replicates. Pilot studies were limited and did not indicate precisely which time points would be optimal to analyze. Therefore, it would be interesting to follow-up with additional samples around the times when changes are seen from positive to negative scoring (end-points,

Figure 4), as well as when there was disagreement between the qPCR check and blind passage staining, e.g. for the 60 °C samples (

Figure 3 B, third column).

All the assays used here for virus infectivity scoring are dependent on replication in primary cells, of which there is a limited supply in our laboratory. Furthermore, the cells could potentially be sensitive to chemical changes that would not necessarily affect the viability of the virus, leading to misinterpretation of virus inactivation, when cell viability is inhibited.

The adverse effect of the farm materials on ASFV survival, as measured here, may contribute to the short time window observed for the transmission of the virus from a contaminated environment (e.g. with feces and straw) to newly introduced pigs [

29,

37]. It has been found that blood can stabilize ASFV [

13] and it may be that if blood is shed from ASFV-infected pigs (as sometimes occurs, see [

8,

38,

39] that the transmission of the virus will be enhanced, potentially also extending the survival of the virus in the environment. In the current study, the materials and virus were incubated in the presence of porcine serum, which is also believed to have a stabilizing and protective effect on the virus [

14,

15].

It has been shown that infection of pigs with ASFV can occur by ingestion of contaminated materials, such as different feed materials [

25]. However, it is also apparent that inoculation of pigs with virus by the oral route is much less efficient than intranasal inoculation [

40]. Furthermore, Niederwerder et al., [

25] have reported that the infectious dose of ASFV in liquid form is much lower than the infectious dose within solid feed. These results suggest that the physical nature of the contaminated materials as well as the level of infectivity within them will determine whether the infectious virus will be able to cause a new round of infection. The survival of the virus within different materials and under different environmental conditions will clearly contribute to the potential for the indirect transmission of the virus to new host animals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, File S1: Collected data from qPCR checks of passages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.O. and A.B.; methodology, all authors; validation, C.M.L.; formal analysis, C.M.L.; investigation, C.M.L.; resources, A.S.O.; data curation, C.M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.L., G.J.B.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, C.M.L.; supervision, A.B. and G.J.B.; project administration, A.B., C.M.L. and G.J.B..; funding acquisition, A.S.O., A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded, in part, by Svineafgiftsfonden (Swine Levy Foundation, Denmark), grant for the project “Afrikansk Svinepest - risiko for smittespredning via virusholdige materialer” and, in part, by the Danish Veterinary and Food Administration (FVST) as part of the agreement of commissioned work between the Danish Ministry of Food and Agriculture and Fisheries with the University of Copenhagen and Statens Serum Institut.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

For this work, the contributions of lab technicians Jane Borch, Anita Pacht and Frank Hansen are greatly appreciated. In addition, laboratory technician Fie Fisker assisted with the qPCR assays. We are also grateful to cell lab technicians Hanne Egelund and Lone Koch Nielsen for the stock preparation of primary cells. Marianne Viuf Agerlin Schmidt at the University of Copenhagen is thanked for collecting the matrix materials from a Danish pig farm.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Montgomery, E. R. On A Form of Swine Fever Occurring in British East Africa (Kenya Colony). J. Comp. Pathol. Ther. 1921, 34, 159–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, C.; Borca, M.; Dixon, L.; Revilla, Y.; Rodriguez, F.; Escribano, J. M. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Asfarviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2018, 99, 613–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejo, A.; Matamoros, T.; Guerra, M.; Andrés, G. A Proteomic Atlas of the African Swine Fever Virus Particle. J. Virol. 2018, 92, (23):e01293–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quembo, C. J.; Jori, F.; Vosloo, W.; Heath, L. Genetic Characterization of African Swine Fever Virus Isolates from Soft Ticks at the Wildlife/Domestic Interface in Mozambique and Identification of a Novel Genotype. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costard, S.; Wieland, B.; de Glanville, W.; Jori, F.; Rowlands, R.; Vosloo, W.; Roger, F.; Pfeiffer, D. U.; Dixon, L. K. African Swine Fever: How Can Global Spread Be Prevented? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2009, 364, 2683–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WOAH (World Organization for Animal health). African Swine Fever (ASF) – Situation Report 52; 2024. https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2024/11/asf-report-58.pdf.

- Guinat, C.; Reis, A. L.; Netherton, C. L.; Goatley, L.; Pfeiffer, D. U.; Dixon, L. Dynamics of African Swine Fever Virus Shedding and Excretion in Domestic Pigs Infected by Intramuscular Inoculation and Contact Transmission. Vet. Res. 2014, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, A. S.; Lohse, L.; Boklund, A.; Halasa, T.; Gallardo, C.; Pejsak, Z.; Belsham, G. J.; Rasmussen, T. B.; Bøtner, A. Transmission of African Swine Fever Virus from Infected Pigs by Direct Contact and Aerosol Routes. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 211, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, A. S.; Belsham, G. J.; Bruun Rasmussen, T.; Lohse, L.; Bødker, R.; Halasa, T.; Boklund, A.; Bøtner, A. Potential Routes for Indirect Transmission of African Swine Fever Virus into Domestic Pig Herds. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. July 1, 2020, pp 1472–1484. [CrossRef]

- AHAW, E. African Swine Fever. EFSA J. 2015, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahantes, J. C.; Gogin, A.; Richardson, J.; Gervelmeyer, A. Epidemiological Analyses on African Swine Fever in the Baltic Countries and Poland. EFSA J. 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, C.; Soler, A.; Nieto, R.; Cano, C.; Pelayo, V.; Sánchez, M. A.; Pridotkas, G.; Fernandez-Pinero, J.; Briones, V.; Arias, M. Experimental Infection of Domestic Pigs with African Swine Fever Virus Lithuania 2014 Genotype II Field Isolate. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krug, P. W.; Davis, T.; O’Brien, C.; LaRocco, M.; Rodriguez, L. L. Disinfection of Transboundary Animal Disease Viruses on Surfaces Used in Pork Packing Plants. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 219, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, A. S.; Lazov, C. M.; Lecocq, A.; Accensi, F.; Jensen, A. B.; Lohse, L.; Rasmussen, T. B.; Belsham, G. J.; Bøtner, A. Uptake and Survival of African Swine Fever Virus in Mealworm (Tenebrio Molitor) and Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia Illucens) Larvae. Pathogens 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plowright, W.; Parker, J. The Stability of African Swine Fever Virus with Particular Reference to Heat and PH Inactivation. Arch. Gesamte Virusforsch. 1967, 21, (3–4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellor, P. S.; Kitching, R. P.; Wilkinson, P. J. Mechanical Transmission of Capripox Virus and African Swine Fever Virus by Stomoxys Calcitrans. Res. Vet. Sci. 1987, 43, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, A. S.; Hansen, M. F.; Rasmussen, T. B.; Belsham, G. J.; Bødker, R.; Bøtner, A. Survival and Localization of African Swine Fever Virus in Stable Flies (Stomoxys Calcitrans) after Feeding on Viremic Blood Using a Membrane Feeder. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 222, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, A. S.; Lohse, L.; Hansen, M. F.; Boklund, A.; Halasa, T.; Belsham, G. J.; Rasmussen, T. B.; Bøtner, A.; Bødker, R. Infection of Pigs with African Swine Fever Virus via Ingestion of Stable Flies (Stomoxys Calcitrans). Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, A. S.; Stelder, J. J.; Tjørnehøj, K.; Johnston, C. M.; Lohse, L.; Kjær, L. J.; Boklund, A. E.; Bøtner, A.; Belsham, G. J.; Bødker, R.; Rasmussen, T. B. Detection of African Swine Fever Virus and Blood Meals of Porcine Origin in Hematophagous Insects Collected Adjacent to a High-Biosecurity Pig Farm in Lithuania; A Smoking Gun? Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelder, J. J.; Mihalca, A. D.; Olesen, A. S.; Kjær, L. J.; Boklund, A. E.; Rasmussen, T. B.; Marinov, M.; Alexe, V.; Balmoş, O. M.; Bødker, R. Potential Mosquito Vector Attraction To- and Feeding Preferences for Pigs in Romanian Backyard Farms. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrith, M.-L.; Vosloo, W. Review of African Swine Fever: Transmission, Spread and Control. J S Afr Vet Assoc 2009, 80, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruszyński, M.; Śróda, K.; Juszkiewicz, M.; Siuda, D.; Olszewska, M.; Woźniakowski, G. Nine Years of African Swine Fever in Poland. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dee, S. A.; Bauermann, F. V.; Niederwerder, M. C.; Singrey, A.; Clement, T.; De Lima, M.; Long, C.; Patterson, G.; Sheahan, M. A.; Stoian, A. M. M.; Petrovan, V.; Jones, C. K.; De Jong, J.; Ji, J.; Spronk, G. D.; Minion, L.; Christopher-Hennings, J.; Zimmerman, J. J.; Rowland, R. R. R.; Nelson, E.; Sundberg, P.; Diel, D. G. Survival of Viral Pathogens in Animal Feed Ingredients under Transboundary Shipping Models. PLoS One 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrini, S.; Feliziani, F.; Casciari, C.; Giammarioli, M.; Torresi, C.; De Mia, G. M. Survival of African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV) in Various Traditional Italian Dry-Cured Meat Products. Prev. Vet. Med. 2019, 162, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederwerder, M. C.; Stoian, A. M. M.; Rowland, R. R. R.; Dritz, S. S.; Petrovan, V.; Constance, L. A.; Gebhardt, J. T.; Olcha, M.; Jones, C. K.; Woodworth, J. C.; Fang, Y.; Liang, J.; Hefley, T. J. Infectious Dose of African Swine Fever Virus When Consumed Naturally in Liquid or Feed. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, A. S.; Lohse, L.; Johnston, C. M.; Rasmussen, T. B.; Bøtner, A.; Belsham, G. J. Increased Presence of Circulating Cell-Free, Fragmented, Host DNA in Pigs Infected with Virulent African Swine Fever Virus. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tignon, M.; Gallardo, C.; Iscaro, C.; Hutet, E.; Van der Stede, Y.; Kolbasov, D.; De Mia, G. M.; Le Potier, M. F.; Bishop, R. P.; Arias, M.; Koenen, F. Development and Inter-Laboratory Validation Study of an Improved New Real-Time PCR Assay with Internal Control for Detection and Laboratory Diagnosis of African Swine Fever Virus. J. Virol. Methods 2011, 178, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bøtner, A.; Nielsen, J.; Bille-Hansen, V. Isolation of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) Virus in a Danish Swine Herd and Experimental Infection of Pregnant Gilts with the Virus. Vet. Microbiol. 1994, 40, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, A. S.; Lohse, L.; Accensi, F.; Goldswain, H.; Belsham, G. J.; Bøtner, A.; Netherton, C. L.; Dixon, L. K.; Portugal, R. Inefficient Transmission of African Swine Fever Virus to Sentinel Pigs from an Environment Contaminated by ASFV-Infected Pigs under Experimental Conditions. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, T. Created in BioRender. https://biorender.com/l98x811.

- Rasmussen, T. Created in BioRender. https://biorender.com/x73q111.

- Rasmussen, T. Created in BioRender. https://biorender.com/f84n232.

- Lecocq, A.; Alencar, A. L. F.; Lazov, C. M.; Rajiuddin, S. M.; Bøtner, A.; Belsham, G. J. Use of a Novel Feeding System to Assess the Survival of a Very Stable Mammalian Virus, Porcine Parvovirus, Within Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia Illucens) Larvae: A Comparison with Mealworm (Tenebrio Molitor) Larvae. Pathogens 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.; Goatley, L. C.; Guinat, C.; Netherton, C. L.; Gubbins, S.; Dixon, L. K.; Reis, A. L. Survival of African Swine Fever Virus in Excretions from Pigs Experimentally Infected with the Georgia 2007/1 Isolate. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blome, S.; Schäfer, M.; Ishchenko, L.; Müller, C.; Fischer, M.; Carrau, T.; Liu, L.; Emmoth, E.; Stahl, K.; Mader, A.; Wendland, M.; Kowalczyk, J.; Mateus-Vargas, R.; Pieper, R. Survival of African Swine Fever Virus in Feed, Bedding Materials and Mechanical Vectors and Their Potential Role in Virus Transmission. EFSA Support. Publ. 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Mohnke, M.; Probst, C.; Pikalo, J.; Conraths, F. J.; Beer, M.; Blome, S. Stability of African Swine Fever Virus on Heat-Treated Field Crops. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 2318–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, A. S.; Lohse, L.; Boklund, A.; Halasa, T.; Belsham, G. J.; Rasmussen, T. B.; Bøtner, A. Short Time Window for Transmissibility of African Swine Fever Virus from a Contaminated Environment. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018, 65, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, C.; Blome, S.; Malogolovkin, A.; Parilov, S.; Kolbasov, D.; Teifke, J. P.; Beer, M. Characterization of African Swine Fever Virus Caucasus Isolate in European Wild Boars. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 2342–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietschmann, J.; Guinat, C.; Beer, M.; Pronin, V.; Tauscher, K.; Petrov, A.; Keil, G.; Blome, S. Course and Transmission Characteristics of Oral Low-Dose Infection of Domestic Pigs and European Wild Boar with a Caucasian African Swine Fever Virus Isolate. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, A. S.; Lazov, C. M.; Accensi, F.; Johnston, C. M.; Rasmussen, T. B.; Bøtner, A.; Lohse, L.; Belsham, G. J. Evaluation of the Dose of African Swine Fever Virus Needed to Establish Infection in Pigs Following Oral Uptake. Pathogens 2024, (In preparation).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).