1. Introduction

African swine fever (ASF) is a hemorrhagic disease of both domestic pigs and wild boar. The disease is caused by infection with African swine fever virus (ASFV), a large dsDNA virus, the sole member of the

Asfarviridae family [

1,

2]. Since 2007, a genotype II strain of ASFV has been spreading outside Africa, and thus, ASF is now reaching pandemic proportions affecting Europe, Asia, Oceania and the Americas [

3] with a high case fatality rate in both domestic pigs and wild boar.

Although ASFV is an arbovirus, naturally transmitted by soft ticks of the genus

Ornithodoros, it is also efficiently transmitted via direct contact between animals [

1,

4]. In Europe, however, most virus introductions into domestic pig herds seem to be mediated via indirect virus transmission, e.g. via pig meat or pork products, materials contaminated with carcass material or blood from infected suids or potentially via blood-feeding insects [

5]. One likely mode-of-transmission from these different materials to pigs is via oral uptake. For meat products, it has been demonstrated that ASFV can be transmitted to pigs indirectly via oral uptake of different products containing the virus [

6,

7,

8] and infection of pigs has been demonstrated following ingestion of blood-fed stable flies [

9]. Proof for efficient transmission via an environment contaminated with ASFV has not been demonstrated in experimental settings. Indeed, on the contrary, transmission from an environment contaminated with the virus has been limited or absent in such studies [

10,

11,

12]. Studies using strict oral inoculation (i.e. oropharyngeal or via intragastric tube) with feed or insect larvae (used for food and feed) containing ASFV have also shown that it can be difficult to demonstrate infection. In one study, using doses from 1 to 10

8 TCID

50 in plant-based feed or liquid, the minimum infectious dose of ASFV for pigs in compound feed was reported to be 10

4 TCID

50 while in liquid it was found to be 1 TCID

50 [

13]. However, in another study, using commercial feed spiked with 10

4.3 to 10

5 TCID

50 of the virus, pigs did not become infected even after feeding with the virus-contaminated feed on 14 consecutive days [

14]. In a study using insect larvae (

Tenebrio molitor or

Hermetia illucens), which had fed on infectious ASFV, infection of pigs could not be demonstrated after feeding 50 virus-fed larvae to each pig. Each

T. molitor larva had fed on 5 µL serum from an infected pig (titer 10

3.3 TCID

50/5 µL), while

H. illucens had fed on feed containing a virus load of 10

5.0 TCID

50/g [

15].

Given the current information available, it seems as if it can be rather difficult to establish ASFV infection via the oral route. To our knowledge, except for one published study [

13], ASFV dose-studies have not used strict oral inoculations. For example, one dose study used intraoropharyngeal inoculation [

16], while another used oronasal inoculation [

17]. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the dose of a European genotype II ASFV needed to establish oral infection of pigs in our experimental settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pigs and Housing

Twenty-four male pigs, at six weeks of age, were included in the study. The pigs were Landrace x Large White and were obtained from a conventional swine herd in Catalonia, Spain. During the experiment, the pigs were housed, under high containment, at the Centre de Recerca en Sanitat Animal (IRTA-CReSA, Barcelona, Spain). On arrival at IRTA-CReSA, the pigs were found to be healthy upon veterinary inspection. Water and a commercial diet for weaned pigs were provided ad libitum.

The study was approved by the Ethical and Animal Welfare Committee of the Generalitat de Catalunya (Autonomous Government of Catalonia; permit number: 12187). All experimental procedures, animal care and maintenance were conducted in accordance with EU legislation on animal experimentation (EU Directive 2010/63/EU).

2.2. Virus and Inoculation Material

For inoculation of pigs, the highly virulent ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie was used. This virus was isolated from spleen material from an ASFV-infected wild boar in Poland in 2015, essentially as described previously but with an additional passage (i.e. three passages in total) in porcine pulmonary alveolar macrophages (PPAM) [

18,

19].

For intranasal inoculation of pigs, the third passage was diluted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to a final concentration of 103 TCID50/2 mL.

For oral inoculation (feeding) of pigs, the third passage virus was diluted to a final concentration of 103 TCID50/0.5 mL, 104 TCID50/0.5 mL and 105 TCID50/0.5 mL, respectively, in PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 5 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific). For each dilution, ice cubes (0.5 mL, ~1x1x1 cm) were then prepared using silicone ice trays. After freezing at -80 °C, one ice cube was put into one soft cake (~50 g, diameter of cake ~2 cm) per pig. This allowed the ice cubes to thaw within the cakes prior to feeding of the pigs, however, this method retained the thawed virus suspension within the cakes.

Prior to the animal experiment, a small pilot study was performed to investigate the stability of infectious ASFV within the ice cubes using different concentration of FBS. The pilot study was performed using the 103 TCID50, 104 TCID50 and 105 TCID50 (per 0.5 mL) doses of the third passage virus in either 100 % FBS, PBS with 5 % FBS or PBS without FBS (Gibco, Thermo Fischer Scientific). The titer of both freshly made virus dilutions and thawed ice cubes of the three virus dilutions with the different concentrations of FBS were determined in primary cells as described just below. This pilot study was performed in order to ensure that the final virus dose provided to the pigs was as expected after the preparation procedures.

Back titration of the samples from the pilot study and on the inoculums from the animal experiment (syringe with virus for intranasal inoculations, ice cubes with the three virus dilutions for oral inoculations) was carried out in PPAM. Following 72 h incubation at 37 °C (5% CO

2), virus-infected cells were stained using an immunoperoxidase monolayer assay (IPMA) [

18,

20]. Infected (red-colored) cells were identified using a light microscope and virus titers were calculated using the method described by Reed & Muench [

21].

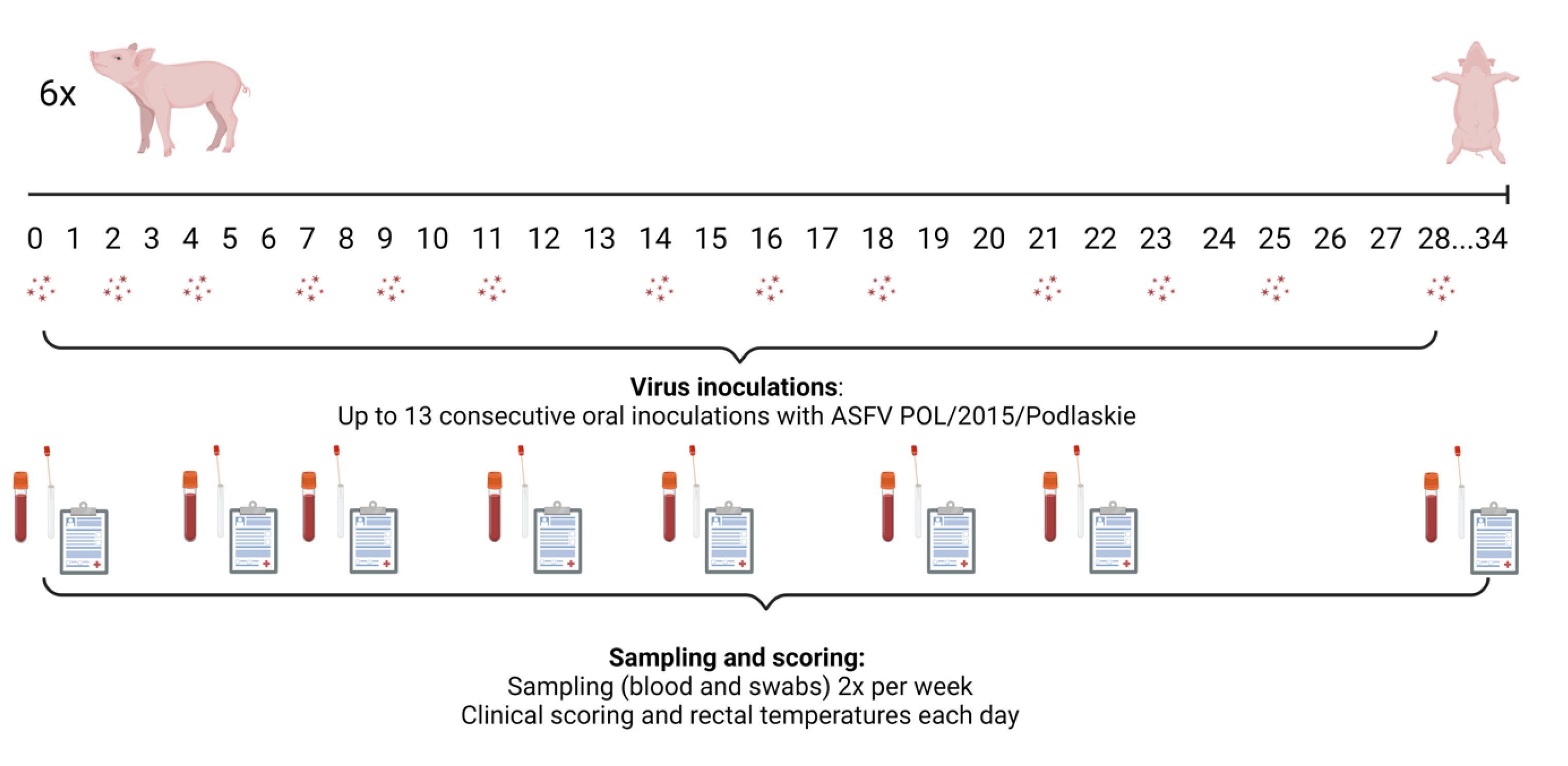

2.3. Study Design

The twenty-four pigs (numbered 51-74) were randomly allocated into four groups (labelled groups 1-4), with six pigs each. The pens were within two high containment stable units, termed boxes 5 and 6, respectively. Pigs 51-56 (group 1) and pigs 57-62 (group 2) were housed within two pens in box 5. These pens were separated by a ~2 m high solid metal wall to prevent direct contact between the groups. Pigs 63-68 (group 3) and pigs 69-74 (group 4) were housed in two similar pens in box 6. The box 5 and box 6 were completely separated from each other, with separate air supplies, equipment, clothing etc. Personnel showered upon exiting each of the two boxes.

After an acclimatization period of one week, the pigs (in groups 1-3) were fed different doses of ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie orally while pigs in group 4 were inoculated intranasally with ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie. Specifically, three groups of six pigs were fed cakes with 10

3 TCID

50 (pigs 51-56, group 1), 10

4 TCID

50 (pigs 57-62, group 2) or 10

5 TCID

50 (pigs 63-68, group 3) of the virus. In total, 13 oral inoculations were planned per group, on days 0, 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 14, 16, 18, 21, 23, 25 and 28 (

Figure 1). The pigs 69-74, (group 4) were inoculated intranasally just on day 0 with 10

3 TCID

50 virus administered using 1 mL per nostril.

2.4. Clinical Examinations and Euthanasia

Clinical scores and rectal temperatures were recorded for each pig on a daily basis. A total clinical score was calculated each day using the system described previously [

19]. Euthanasia was performed by intravascular injection of Pentobarbital following deep anesthesia either when pigs reached the pre-determined humane endpoints or at the end of the study period.

2.5. Sampling

EDTA-stabilized blood (EDTA-blood), unstabilized blood samples (for serum), nasal and oral swabs were obtained from the pigs twice a week, on days 0, 4, 7, 11, 18, 21 and at euthanasia as depicted in

Figure 1. Nasal and oral swabs were added to 1 ml PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Collected serum, EDTA-blood and swab samples were frozen at -80 °C until further use. Prior to analysis, the swab samples were vortexed and centrifuged briefly.

2.6. qPCR Analysis of EDTA-Blood and Swab Samples

Nucleic acids were isolated from EDTA-blood samples and the supernatants from the nasal and oral swabs using the MagNA Pure 96 system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and analyzed for the presence of ASFV DNA essentially as described previously [

18,

22] using the CFX Opus Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). qPCR results are presented as viral genome copy numbers per mL. Genome copy numbers were calculated based on a standard curve made from assaying a 10-fold dilution series of the pVP72 plasmid [

19]. A positive result was defined as giving a threshold cycle value (Cq) at which FAM (6-carboxy fluorescein) dye emission was above background within 42 cycles.

2.7. Detection of Infectious Virus in Nasal Swabs

Nasal swab samples in which ASFV DNA was readily detected (Cq value below 30) were added to PPAM and passaged once. Virus-infected cells were identified using the IPMA, essentially as described previously, but with minor modifications [

12]. Briefly, PPAM maintained in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM, Gibco, Thermo Fischer Scientific) with 5% FBS (Gibco, Thermo Fischer Scientific) were seeded into NUNC 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells (100µL with 1.6 x 10

6 cells/mL) were inoculated in triplicate with 50µL of a 1:1 mix of MEM 10xanti and swab filtrate. The MEM 10xanti contained 5% FBS and antibiotics (streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), neomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), amphotericin (Sigma-Aldrich), benzylpenicillin (Sigma-Aldrich))and the swab supernatants had been passed through a 0.45 µm filter (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The cells were incubated at 37 °C (in 5% CO

2) for 72 h, and virus-infected cells were identified using IPMA, as described in section 2.2.

2.8. Anti-ASFV Antibody Detection in Serum

Serum samples obtained from the pigs prior to inoculation and at euthanasia were tested for the presence of anti-ASFV antibodies using the Ingezim PPA Compac ELISA (®INGENASA INGEZIMPPA COMPAC K3 INGENASA, Madrid, Spain). The analysis was performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

In addition, an in-house indirect immunoperoxidase test (IPT) was used to test for the presence of anti-ASFV antibodies. Briefly, Vero cells were inoculated with a Vero-cell adapted ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie and fixed following 72 h incubation at 37 °C . Following addition of serum samples, protein A-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich) together with hydrogen peroxide and 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole (Sigma Aldrich) were used as chromogenic substrate.

2.9. Preparation of Long PCR Products from Viral DNA

DNA was extracted from the virus sample used as the inoculum (3

rd passage), as in section 2.6, and was used to generate overlapping long PCR products, as previously described [

23]. Briefly, amplicons derived from the inoculum sample were amplified by long PCR using AccuPrime high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in a final volume of 50 µl, then incubated at 94 °C for 30 s followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 12 min, with a final extension at 68 °C for 12 min. The PCR products were analyzed using the Genomic DNA ScreenTape on a 4200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) together with GeneRuler 1 kb Plus DNA Ladder (Thermo Scientific), and their concentrations were estimated Quant-iT™ 1X dsDNA broad-range kit (Invitrogen) on a FLUOstar® Omega (BMG LABTECH, Mornington, VIC, Australia) instrument.

2.10. Variant Calling

The overlapping PCR products were pooled for the inoculum and sequenced using MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with a modified Nextera XT DNA library protocol with the MiSeq reagent kit v2 (300 cycles), resulting in 2×150 bp paired-end reads. Reads were trimmed using AdapterRemoval [

24] by at least 30 bp at both the 5’ and 3’ ends, to ensure primer removal, as well as for quality (q30). Variant calling and annotation were performed using a combination of BWA-MEM, Samtools, Lo-Freq and SnpEff [

25,

26,

27,

28], as previously described [

23], together with the ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie reference sequence (MH681419.2). Variants were filtered for a minimum coverage of 50, frequency above 2%, and strand-bias Phred Score below 60.

2.11. Deletion Screening by PCR

Extracted DNA preparations from EDTA-blood samples in which ASFV DNA was readily detected (Cq value below 30, corresponding to above 6.4 log

10 genome copies/mL) were screened for the internal deletion event at pos. 6362-16849 (10487 bp) present within the population of viruses in the ASFV POL/Podlaskie/2015 inoculum as described previously [

23]. Briefly, the extracted DNAs were amplified by long PCR with primers spanning the deletion region at pos. 6188-17145 (del-PCR) or primers located within this region at pos. 6708-7668 (noDel-PCR). As positive controls, we used extracted DNA from the spleen or EDTA-blood from ASFV-infected pigs, derived from previous studies [

9,

23], which had been shown to lack or to have the deletion, respectively. UltraPure™ DNase/RNase-Free Distilled Water was used as a negative control. The PCR products were analyzed using the Genomic DNA ScreenTape or D5000 ScreenTape on a 4200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies) together with GeneRuler 1 kb Plus or GeneRuler 1kb DNA Ladder (Thermo Scientific).

2.12. Nanopore Sequencing

PCR products were cut out of agarose gels and purified using the GeneJET Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were then sequenced on the Nanopore (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) using a standard ligation sequencing of amplicons with native barcoding protocol for the SQK-LSK109 and native barcoding expansion kits on a R9.4.1 flow-cell. Reads were filtered for size (3200-4200 bp) using SeqKit [

29] and were trimmed using chopper [

30] by 30 bp at both the 5’ and 3’ ends to ensure primer removal, as well as for quality (q9). The trimmed reads were subsequently mapped to the ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie reference sequence using a combination of minimap2 [

31] and Samtools [

26].

3. Results

3.1. Preparation and Back-Titration of the Inoculation Material

A pilot study was performed with the three different dilutions of the third passage ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie, i.e. a low (103 TCID50), medium (104 TCID50) and high (105 TCID50) dose. The dilutions were made using 100 % FBS, or PBS with 5 % FBS or PBS without FBS, and were titrated in PPAM with, or without, a freeze/thaw cycle (one freeze/thaw cycle mimicked how the ice cubes used for inoculation of the pigs were handled). The pilot study indicated a stabilizing effect of both 5 % FBS and 100 % FBS during the freeze/thaw cycle, this stabilizing effect was especially apparent at the low (103) and medium (104) doses.Hence, the final inoculation material consisted of ice cubes made from the third passage ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie diluted in PBS with 5 % FBS.

Back titration of the inoculation material in PPAM yielded titers of between 4.5 to 4.7 log10 TCID50 per 0.5 mL with a mean of 4.7 log10 TCID50 for the high doses. The medium doses yielded titers from 2.5 to 3.5 log10 TCID50 per 0.5 mL with a mean of 3.1 log10 TCID50, and the low dose titers from 1.5 to 3.3 log10 TCID50 per 0.5 mL with a mean of 2.5 log10 TCID50. Note that back titrations were performed on the inoculums following two additional freeze/thaw cycles when compared to feeding of the pigs due to shipment of the samples from Barcelona to Denmark for laboratory analysis after the animal experiment.

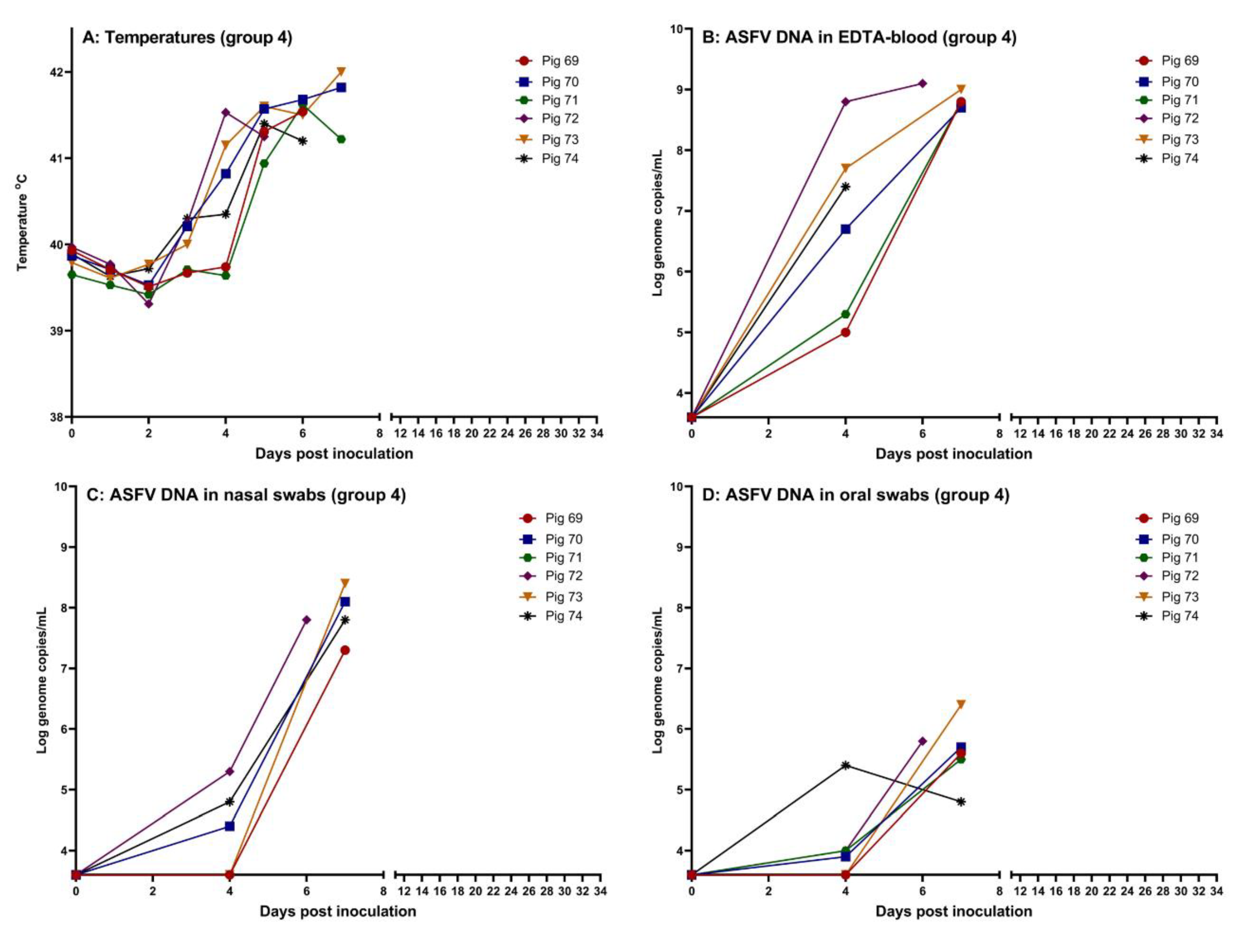

3.2. Course of Infection in Intranasally Inoculated Pigs

Following intranasal inoculation with 103 TCID50 of ASFV, all six inoculated pigs in group 4 (pigs 69-74) presented with high fever (rectal temperature above 41 °C ) from 4-5 dpi. Clinical signs included depression, dyspnea and ataxia. Pigs 72 and 74 were found dead upon entering the pens at 6 dpi and 7 dpi, respectively. Prior to this, high fever had been observed in both of the pigs for two consecutive days along with mild (pig 72) to moderate depression (pig 74) and slight dyspnea (pig 74).

EDTA-blood was drawn from the heart of the deceased pig 72 at 6 dpi, the same, however, was not possible from pig 74 at 7 dpi. The remaining four pigs were euthanised at 7 dpi for animal welfare reasons. Rectal temperatures, for each pig, are shown in

Figure 2 (panel A). Measurements of viremia, by qPCR, confirmed high levels of viral DNA were present in EDTA-blood from the infected animals (

Figure 2, panel B). ASFV DNA was also detectable in nasal and oral swabs from all six pigs, with higher levels of viral DNA in nasal swabs compared to oral swabs (

Figure 2, panels C and D). Using inoculation of PPAMs, infectious virus was detected in nasal swabs obtained from all six pigs at euthanasia. No anti-ASFV-specific antibodies were detected in serum from the pigs at euthanasia (see Supplementary S1 for a summary of data obtained for the pigs).

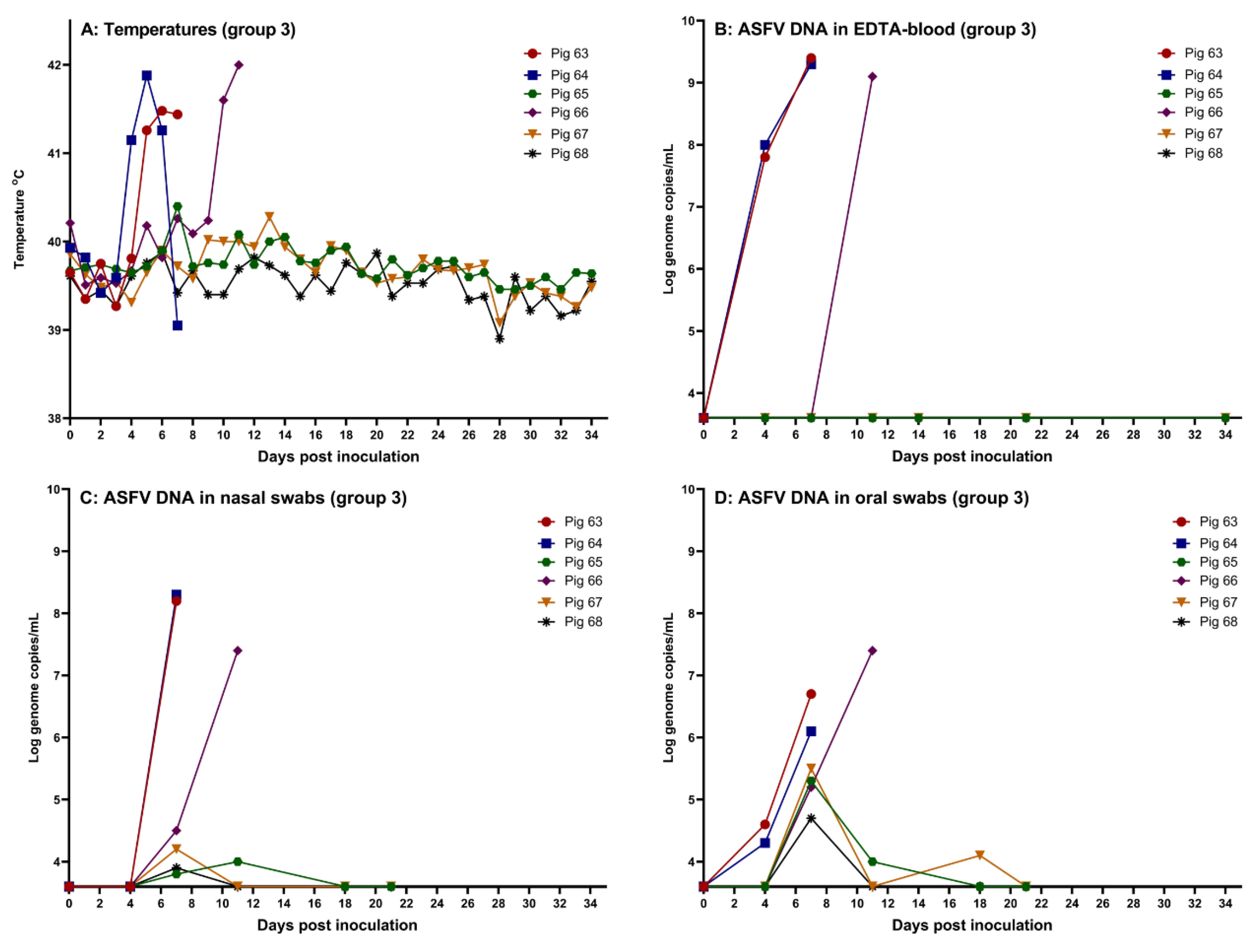

3.3. Course of ASFV Infection in Orally Inoculated Pigss

Following feeding of pigs in group 3 with the highest dose of the virus, ~10

5 TCID

50 (on days 0, 2 and 4), pigs 63 and 64 presented with high fever from day 4 or 5. Clinical signs included depression, dyspnea and reddening of the skin. Two pigs reached the humane endpoints at day 7 and were euthanized. Rectal temperatures are shown in

Figure 3 (panel A). As infection after feeding with the high dose was evident at this time point, no further feeding of pigs 65-68 with ASFV was performed on day 7 and onwards. In addition, pig 66 had a high fever from day 10 and was euthanized on the following day when it presented with depression and dyspnea. Except for transient mild depression and diarrhea on some days, the remaining three pigs, 65, 67 and 68, despite three repeated oral inoculations, did not develop clinical signs that could indicate an infection with ASFV during the study period (

Figure 3, panel B). These three pigs were euthanized on day 34, when the study was terminated. Assays for ASFV DNA in EDTA-blood provided results that were fully consistent with the clinical findings. High levels of ASFV DNA were readily detected in blood samples obtained from pigs 63, 64 and 66, while no ASFV DNA was detected in EDTA-blood from the three remaining pigs in this group (

Figure 3, panel B).

Among the nasal and oral swabs, the highest levels of ASFV DNA were found in the samples from the three infected pigs, while lower levels of the viral DNA were found in swabs obtained from the remaining three pigs in the pen. As also observed from the intranasally infected pigs, higher levels of viral DNA were present in nasal swabs than in oral swabs from the three infected pigs. However, for the three uninfected pigs (pigs 65, 67 and 68), the opposite was observed, i.e. higher levels of ASFV DNA were detected in oral swabs obtained from these pigs than in nasal swabs (

Figure 3, panels C and D). Infectious ASFV was also detected in nasal swabs obtained from pigs 63, 64 and 66 at euthanasia (see Supplementary S1).

Following feeding with either the low dose of ASFV (group 1) or the medium dose (group 2), respectively, one pig (pig 56, from group 1) that was fed the low dose presented with high fever (and nasal mucoid discharge) on days 9 and 10. This pig was euthanized on day 11 when it appeared depressed. However, no ASFV DNA was detected in the blood samples obtained from this pig. The remaining 11 pigs did not present with high fever (defined as rectal temperature above 41 °C ) nor with any clinical signs indicative of ASFV infection and no ASFV DNA was detected in their blood. These pigs were euthanized on day 34, when the study was terminated. At this time point they had each received 13 consecutive oral doses of ASFV. During the time course of the experiment, very low levels of viral DNA were detected in a few swab samples obtained from the pigs in the medium and low dose oral groups. Specifically, from the medium dose group (group 2), 3.7 and 4.5 log10 genome copies/mL were detected in two mouth swabs from pigs 59 and 62 on day 4, and 4.2 log10 genome copies/mL were present in a nasal swab from pig 61 at day 7. In the low dose oral group (group 1), 3.8 and 4.0 log10 genome copies/mL were detected in two oral swabs, from pig 56 (on day 7) and pig 51 (on day 11), respectively.

No anti-ASFV-specific antibodies were detected in the serum obtained at euthanasia from pigs within the three orally-inoculated groups (see Supplementary S1).

3.4. Variant Analysis of ASFV in the Inoculum

The ASFV DNA in the inoculum was screened for the presence of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertion and deletions (indels) in the MiSeq reads. All PCR fragments had read coverage ≥50 for the entirety of the fragments, except for fragments 05a, 06 and 14 which lacked this degree of coverage at 562, 124 and 405 genome positions in total, respectively. In the virus inoculum, a total of two silent SNPs were present, G33319A and A44769G, located in the MGF 505-2R and MGF 505-10R genes, respectively, at a frequency of 5.8% and 2.6%, respectively. Over 70 indels were identified, ranging in size from 1-3 bp, however, the majority were 1 bp in size (>68% deletions and >23% insertions), and were all located in homopolymeric regions.

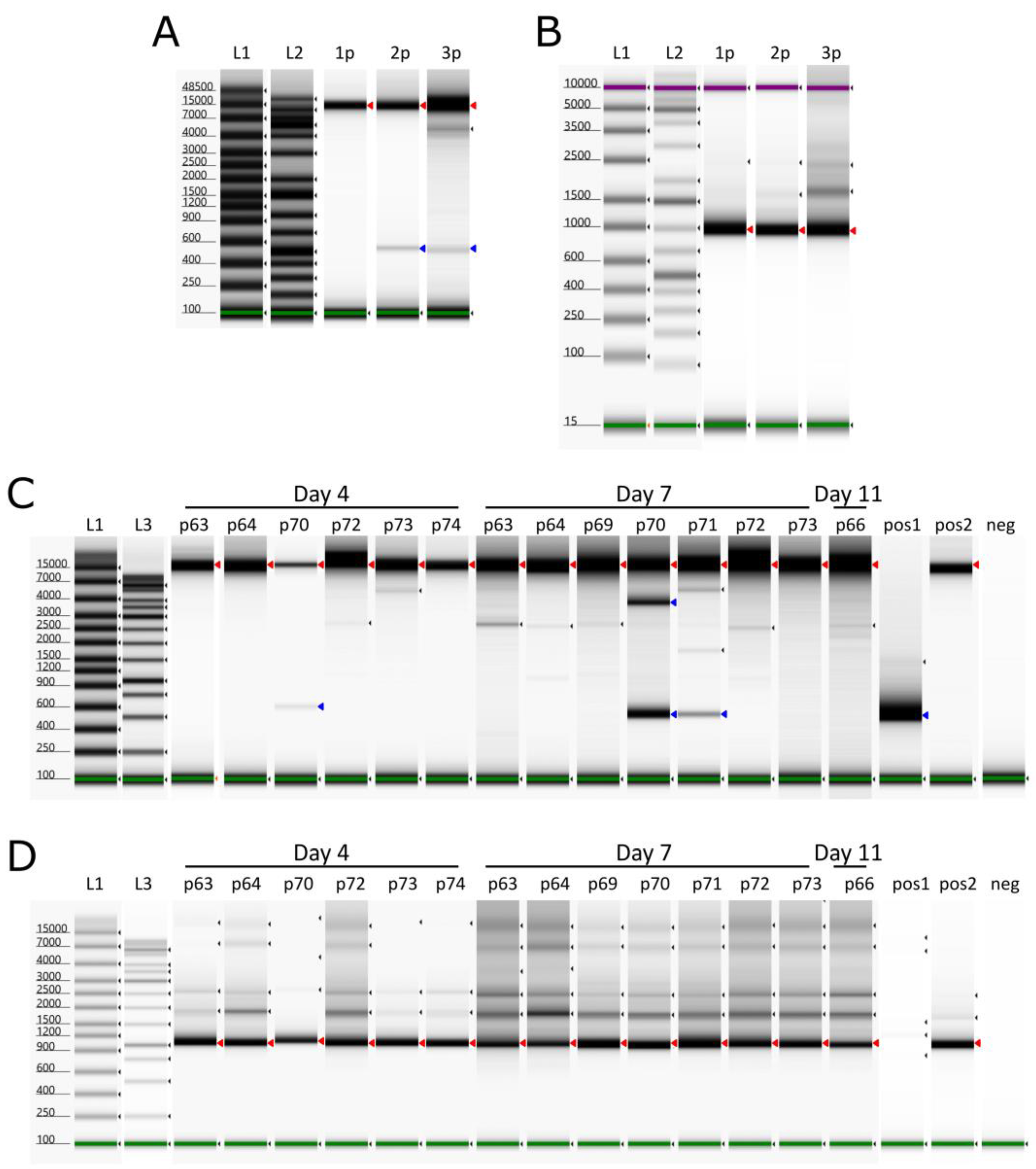

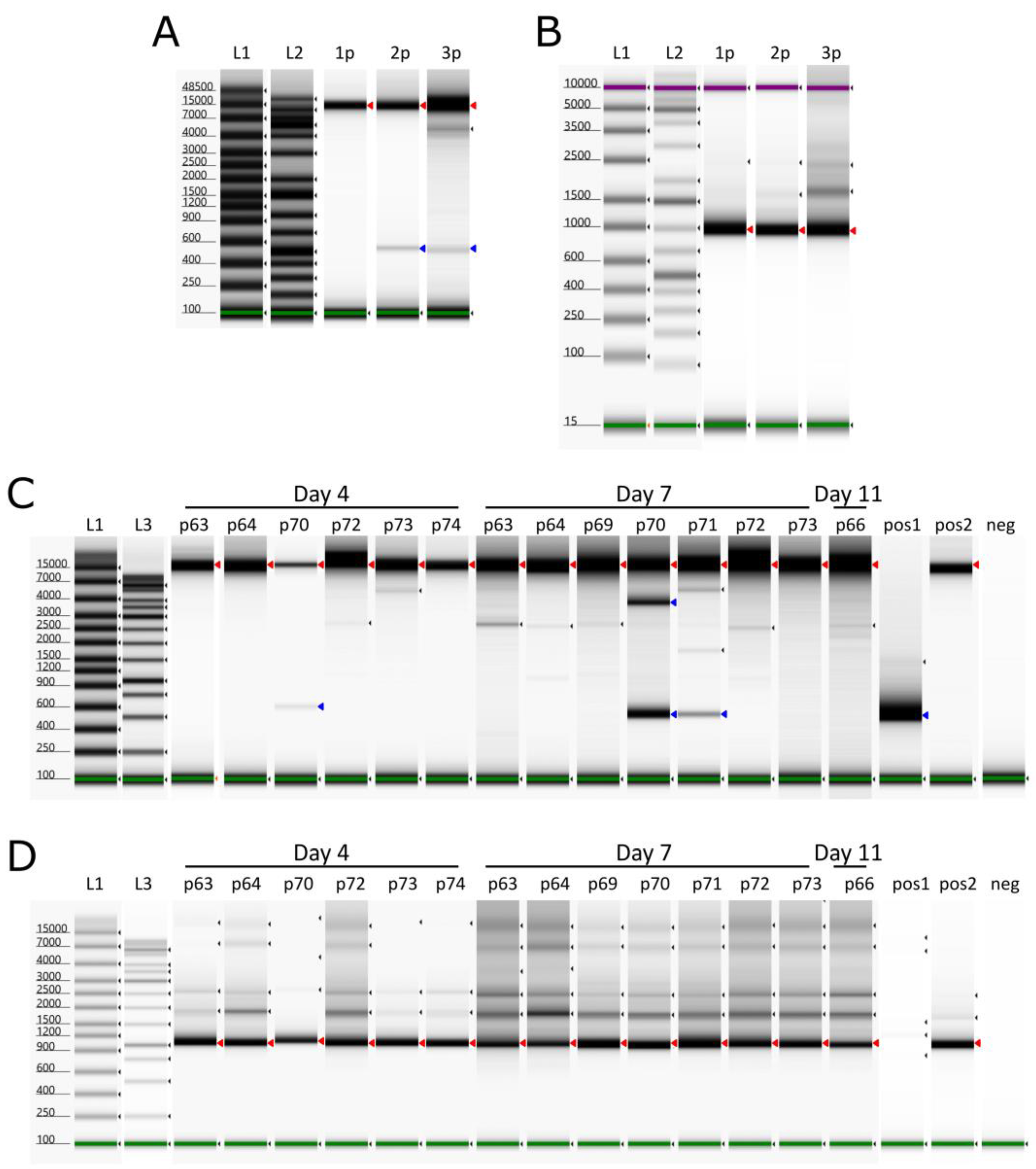

3.5. Deletion Screening by PCR and Sequencing

The EDTA-blood samples and the inoculum were screened for the presence of the internal deletion event at pos. 6362-16849 (10487 bp), which was previously found in the second passage of the virus in PPAM [

23]. The inoculum (third passage) produced products of both ~500 bp and ~11 kb in the del-PCR, which spans the deletion site, consistent with the presence of genomes, which had undergone the deletion event as well as the expected full-length PCR product, respectively (

Figure 4, panel A). The product of ~1 kb in the noDel PCR, from within the deletion, (

Figure 4, panel B), is consistent with the ability to produce full-length (11 kb) products in the del-PCR assay. All pigs yielded the full-length products (

Figure 4 panels C and D), however pigs 70 and 71 (from group 4) at day 7 also produced products consistent with harbouring the deletion variant virus. The blood sample from pig 70 also contained shortened virus genomes at day 4, however, pig 71 was not screened in this assay on day 4 due to the low level of viral DNA present in EDTA-blood at that time (Cq value above 30). The viral DNA from pig 70 also generated a prominent product of ~3700 bp (see

Figure 4, panel C), which was extracted and sequenced using Nanopore technology, which revealed that this other deletion occurred between positions 7115 and 14504, a total of 7389 bp; this deletion should result in a PCR product of ~3568 bp (consistent with the observed product). This deletion results in the loss of 15 complete genes; the majority are members of MGF 110 (3L-12L) family, with a 5’ truncation of the MGF 110-2L gene and a 3’ truncation of the MGF 110-13La-13Lb, as well as ASFV G ACD 00120, 00160, 00190, 00240, MGF100-1R and 285L.

4. Discussion

In this study, we were able to demonstrate infection with ASFV following feeding with a high dose (10

5 TCID

50) of the ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie. Oral administration of the lower doses of the same virus did not result in infection. In contrast, intranasal inoculation with the low dose (10

3 TCID

50) of ASFV was very efficient in establishing infection, underlining that infection with ASFV by the intranasal route is much easier to establish than infection via oral uptake. A higher efficiency of intranasal versus oral inoculation was described previously with the highly virulent ASFV-Malawi strain (genotype VIII, [

32]) [

16].

The relatively high dose needed for the ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie to establish oral infection in the current study is also consistent with other studies exposing pigs to ASFV via oral uptake of feed spiked with the virus. In one study, infection of pigs could not be established after 14 consecutive days being fed with commercial feed spiked with serum from a pig infected with ASFV Georgia 2007/1 at levels of ~10

4 to 10

5 TCID

50 [

14]. In another study, using virus doses ranging from 10

3 to 10

8 TCID

50, a minimum infectious dose of 10

4 TCID

50 was reported after one feed with compound feed spiked with spleen material from a pig infected with the ASFV Georgia 2007 [

13]. In studies using oral inoculation with different insects, feeding of 24 pigs with 50 virus-fed larvae, calculated to contain about 10

5 TCID

50 of the ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie in total, did not result in infection of any of the pigs [

15]. The larvae had either been fed on serum (

T. molitor) or spleen suspension from ASFV-infected pigs (

H. illucens). However, in an earlier study using the same virus, oral uptake of 20 blood-feeding flies fed on EDTA-blood containing infectious ASFV (calculated virus load in 20 flies was 10

5 TCID

50) did result in infection in 50 % of the exposed pigs [

9].

The reasons for the differences reported in the ability of ASFV to establish infection after feeding of pigs, even at medium to high doses (10

4 TCID

50 and up) could reflect other factors than the virus dose itself. The materials used for spiking and the feeding material themselves could also impact the outcome of the virus exposures. For spiking, blood (EDTA-blood or serum), organ material (spleen) and infected-cell supernatants have each been used in the various studies. It has previously been demonstrated that serum can have a stabilizing effect on ASFV [

15,

33], and it seems as if serum can enhance the infectivity of extracellular (but not intracellular) ASFV virions [

34]. It should be noted that the studies that did report successful oral infection used spleen suspension [

13], cell supernatant diluted in 5 % serum (current study) or EDTA-blood [

9]. On the other hand, the studies that failed to demonstrate infection of pigs used either spleen material [

15] or serum ([

14,

15]. Hence, a clear indication of the effect of the type of spiking material used cannot be made on the available evidence.

Another factor affecting the infection efficiency may be the feed material itself, i.e. the material and its preparation (e.g. the adsorption time of the spiking virus to the feed as also discussed previously by others [

14]). These processes could have an enhancing or inhibitory effect on either the stability of the virus or the delivery of the virus dose (e.g. for establishing contact between the oropharynx and the virus). Based on the differences in the minimum infectious dose observed for oral uptake of solid feed (10

4 TCID

50) versus liquid feed (1 TCID

50) in one study, it was suggested the liquid provided a more suitable medium for virus contact to the tonsils or other tissues where primary virus replication can occur following oronasal or intraoropharyngeal virus exposure [

13]. In the current study, the soft cakes most likely provided a “sticky matrix” that allowed for prolonged exposure of the inoculation material to the lymphoid tissues in the upper gastrointestinal tract. This would include the tonsils and the medial retropharyngeal lymph nodes; the latter have recently been identified as key entry points for infection with ASFV in both domestic pigs and wild boar [

35]. Even though the soft cakes have proven suitable for achieving oral infection, using either virus suspension in the current study or flies in a previous study [

9], future studies could aim at developing more user-friendly, highly palatable and standardized delivery systems for oral exposures with ASFV (e.g. for infection and possible vaccination). From the data available so far, it seems as if a delivery system that, like the quite sticky soft cakes, allows the virus to come into prolonged contact with the upper gastrointestinal tract (e.g. using gels), could be a feasible approach.

From back titration of the administered dose, it appears as if pigs in the low dose and medium dose groups could, unintentionally, have been given slightly lower doses than anticipated. Due to logistical reasons, back titrations were (non-optimally) performed after an additional two freeze/thaw cycles when compared to the time of inoculation, which could have affected the apparent level of the virus in the back titration. If so, this effect seems to have been more pronounced in the more diluted virus suspensions (low dose and medium dose) when compared to the high dose suspension. As serum seems to have a stabilizing effect on the virus [

15,

33,

34] a higher concentration of serum could be used for preparation of the inoculum in future studies. In the low dose and medium dose groups, the lack of infection of pigs following 13 consecutive inoculations with virus doses from ~10

2 to 10

4 TCID

50 is not consistent with earlier statistical model predictions from an earlier study [

13]. The model applied in that study was based on infection of 40 % of pigs that were exposed to 10

4 TCID

50 orally, and predicted that 10 oral exposures to 10

2, 10

3 or 10

4 TCID

50 would lead to infection of 25 %, 50 % and 100 % of the exposed pigs, respectively. For the high dose used in the current study, 10

5 TCID

50, the same model was based on 44 % of pigs being exposed to 10

5 TCID

50 in feed becoming infected with ASFV, leading to a prediction of 3 exposures resulting in 75 % of the exposed pigs becoming infected. In the current study, using a dose of 10

5 TCID

50, we found that only 33-50 % of the exposed pigs were infected with ASFV following up to three doses. Further studies are required to determine the effects of multiple oral inoculations of ASFV.

Due to the nature of the study design used here, it cannot be readily determined whether 2 or 3 pigs became infected due to feeding with the high dose of ASFV or after which of the three oral inoculations the infection was actually established. However, when comparing the time course of the infection in the three pigs to the course of infection in the intranasally inoculated pigs, it seems most likely that pigs 63 and 64 were infected already from the first inoculation at day 0. This is also in line with earlier results obtained from feeding of pigs with the same virus [

9]. The delayed appearance of infection in pig 66, could either indicate that infection was established in this pig after the inoculation on day 4, or that the pig was infected via direct contact to its infected pen mates (pigs 62 and 64). Using the same virus, a four-day delay in the course of infection has previously been observed between intranasally inoculated pigs and “in contact” animals [

18]. Interestingly, the lack of virus transmission to the last three pigs, pigs 65, 67 and 68, within the same pen, underlines that the transmission of ASFV is not always very efficient, especially when blood is not present in the pen environment [

12]. Assuming that ASFV DNA detected in oral and nasal swabs obtained from these three pigs at day 7 indicates exposure to virus excreted from their infected pen mates, it appears as if they were exposed primarily via the less efficient oral route.

The internal deletion event at pos. 6362-16849 (10487 bp) originally arose in the second passage in cell-culture [

23] and was clearly maintained in the third passage, used as inoculum for this study. It was maintained as a minority variant within the viral population of pigs 70 and 71, but does not seem to have affected pathogenicity. Pig 70 contained an additional internal deletion of 7389 bp within the same region of the genome as the 10847 bp deletion. This smaller deletion likely occurred independently in the viral population. It could be non-essential (i.e. selected due to quicker replication of smaller genomes) or could indicate that this region of the genome is under selective pressure, suggesting a complex evolutionary landscape, with different variants competing or coexisting.

NGS sequencing revealed that, at the consensus level, the sequence of the inoculum matched the published sequence of ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie, and that only minority SNPs and 1-3 base-pair indels in homopolymeric regions were detected in the variant analysis. It is difficult to determine the veracity of such short indels in homopolymeric regions by other means, as most sequencing technologies have difficulties with these [

36,

37,

38,

39].

In conclusion, we have confirmed that infection with ASFV was not easily established following oral uptake of the virus. Only a high dose of a genotype II virus, the ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie, was sufficient to establish infection of half of the pigs exposed by this route in our experimental setting. The high dose of ASFV needed in order to infect pigs orally could have implications for the dose needed for any future live-attenuated baited vaccine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.O., C.M.L., F.A., T.B.R., A.B., L.L. and G.J.B.; methodology, A.S.O., C.M.L., F.A., C.M.J., T.B.R., A.B., L.L., and G.J.B; investigation, A.S.O., C.M.L., F.A., and C.M.J.; resources, L.L. and G.J.B.; data curation, A.S.O, C.M.L., and C.M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.O.; writing—review and editing, C.M.L., F.A., C.M.J., T.B.R., A.B., L.L. and G.J.B.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Study design for the pigs (in groups 1-3) that were administered ASFV orally in cakes. The serum tubes indicate that sampling (blood and swabs) was performed from the pigs on these days. Clinical scores and rectal temperatures were recorded daily. Created in BioRender (Toronto, ON, Canada) under the license Olesen, A. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/c84u960.

Figure 1.

Study design for the pigs (in groups 1-3) that were administered ASFV orally in cakes. The serum tubes indicate that sampling (blood and swabs) was performed from the pigs on these days. Clinical scores and rectal temperatures were recorded daily. Created in BioRender (Toronto, ON, Canada) under the license Olesen, A. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/c84u960.

Figure 2.

Data obtained from the intranasally inoculated pigs (pigs 69-74, group 4). (A) Rectal temperatures, (B) Detection of ASFV DNA in EDTA-blood, (C) Detection of ASFV DNA in nasal swabs, (D) Detection of ASFV DNA in oral swabs. The threshold for detection of ASFV DNA in the qPCR is Cq 42, which corresponds to 3.6 log10 genome copies/mL. Created using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA).

Figure 2.

Data obtained from the intranasally inoculated pigs (pigs 69-74, group 4). (A) Rectal temperatures, (B) Detection of ASFV DNA in EDTA-blood, (C) Detection of ASFV DNA in nasal swabs, (D) Detection of ASFV DNA in oral swabs. The threshold for detection of ASFV DNA in the qPCR is Cq 42, which corresponds to 3.6 log10 genome copies/mL. Created using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA).

Figure 3.

Data obtained from the pigs fed the high dose of the virus orally (pigs 63-68, group 3). (A) Rectal temperatures, (B) Detection of ASFV DNA in EDTA-blood, (C) Detection of ASFV DNA in nasal swabs, (D) Detection of ASFV DNA in oral swabs. The threshold for detection of ASFV DNA in the qPCR is Cq 42, which corresponds to 3.6 log10 genome copies/mL. Created using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software).

Figure 3.

Data obtained from the pigs fed the high dose of the virus orally (pigs 63-68, group 3). (A) Rectal temperatures, (B) Detection of ASFV DNA in EDTA-blood, (C) Detection of ASFV DNA in nasal swabs, (D) Detection of ASFV DNA in oral swabs. The threshold for detection of ASFV DNA in the qPCR is Cq 42, which corresponds to 3.6 log10 genome copies/mL. Created using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software).

Figure 4.

Deletion screening of ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie inoculums (1p, 2p, 3p) together with group 1 (pig 63, 64, 66) and group 4 infected pigs from sampling days with Cq values in the ASFV qPCR below 30 in the EDTA-blood. (A) PCRs with primers covering nt 6188-17145 (del-PCR). (B) PCR with primers covering nt 6708-7668 (noDel-PCR). (C) PCR with primers covering nt 6188-17145 (del-PCR). (D) PCR with primers covering nt 6708-7668 (noDel-PCR). L1: TapeStation ladder, L2: GeneRuler 1 kb plus, L3: GeneRuler 1 kb, 1p: First passage, 2p: Second passage, 3p: Third passage, p63: Pig 63 EDTA-blood, p64: Pig 64 EDTA-blood, p66: Pig 66 EDTA-blood, p69: Pig 69 EDTA-blood, p70: Pig 70 EDTA-blood, p71: Pig 71 EDTA-blood, p72: Pig 72 EDTA-blood, p73: Pig 73 EDTA-blood, p74: Pig 74 EDTA-blood, pos1: Positive control with deletion, pos2: Positive control without deletion, neg: Negative control (H2O). Red arrowheads indicate wildtype, whereas blue arrowheads indicate deletion variant. Green and purple bands indicate lower and upper molecular weight markers, respectively, whereas small black arrowheads indicate bands detected by the TapeStation Analysis software (Agilent Technologies).

Figure 4.

Deletion screening of ASFV POL/2015/Podlaskie inoculums (1p, 2p, 3p) together with group 1 (pig 63, 64, 66) and group 4 infected pigs from sampling days with Cq values in the ASFV qPCR below 30 in the EDTA-blood. (A) PCRs with primers covering nt 6188-17145 (del-PCR). (B) PCR with primers covering nt 6708-7668 (noDel-PCR). (C) PCR with primers covering nt 6188-17145 (del-PCR). (D) PCR with primers covering nt 6708-7668 (noDel-PCR). L1: TapeStation ladder, L2: GeneRuler 1 kb plus, L3: GeneRuler 1 kb, 1p: First passage, 2p: Second passage, 3p: Third passage, p63: Pig 63 EDTA-blood, p64: Pig 64 EDTA-blood, p66: Pig 66 EDTA-blood, p69: Pig 69 EDTA-blood, p70: Pig 70 EDTA-blood, p71: Pig 71 EDTA-blood, p72: Pig 72 EDTA-blood, p73: Pig 73 EDTA-blood, p74: Pig 74 EDTA-blood, pos1: Positive control with deletion, pos2: Positive control without deletion, neg: Negative control (H2O). Red arrowheads indicate wildtype, whereas blue arrowheads indicate deletion variant. Green and purple bands indicate lower and upper molecular weight markers, respectively, whereas small black arrowheads indicate bands detected by the TapeStation Analysis software (Agilent Technologies).