1. Introduction

Social media has become an integral part of contemporary childhood, with platforms continually evolving to capture users’ attention through increasingly engaging features. Among these features, short-form videos—commonly known as “reels”—have emerged as a dominant format due to their brevity, entertaining nature, and algorithmic personalization. Platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube Shorts use machine-learning models to curate content that maximizes engagement and retention (Xue et al., 2025). While much research has focused on adolescents and adults, there is much less empirical examination of how these platforms affect younger children, particularly those under age 10, whose cognitive and emotional capacities are still rapidly developing.

Over the last decade, the global digital ecosystem has undergone a profound transformation with the rapid rise of short-form video platforms such as TikTok, Instagram Reels, Facebook Reels, and YouTube Shorts. These platforms rely on algorithmically curated, auto playing, and rapidly changing video content designed to maximize user engagement through novelty, emotional arousal, and continuous scrolling. While the mental health implications of social media have been widely studied among adolescents and young adults, significantly less scholarly attention has been paid to children under the age of 10, particularly in low- and middle-income countries such as Bangladesh.

Children below the age of 10 occupy a critical developmental window characterized by rapid neurological growth, emotional regulation formation, and social learning (Piaget, 1952; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). During this stage, the brain is especially sensitive to environmental stimuli, including digital media exposure. Unlike traditional television or educational media, social media reels are interactive, personalized, and algorithmically optimized to exploit attentional vulnerabilities, making them qualitatively different from earlier forms of screen exposure (Montag et al., 2019).

In Bangladesh, children’s exposure to social media has expanded dramatically due to increased smartphone penetration, low-cost mobile internet, and the normalization of digital entertainment within households. According to national ICT data, children frequently access mobile devices either independently or through shared family phones, often without age-appropriate filters or parental mediation. As a result, children under 10 are increasingly exposed to reels featuring exaggerated emotional expressions, hyper-stimulating visuals, consumerist messages, and sometimes inappropriate or distressing content. This raises urgent concerns regarding attention regulation, emotional well-being, behavioral development, and early mental health risks.

Existing research demonstrates that excessive digital media exposure in early childhood is associated with attention problems, emotional dysregulation, sleep disturbances, and increased anxiety symptoms (Domingues-Montanari, 2017,

https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00051). However, most of these studies focus on screen time broadly and do not adequately differentiate between passive media consumption and algorithmically driven short-form video content, which operates through fundamentally different psychological mechanisms. Social media reels intensify reward-seeking behavior through variable reinforcement schedules, a mechanism well documented in behavioral neuroscience (Montag & Hegelich, 2020)..

In the Bangladeshi context, the issue is further complicated by limited digital literacy among parents, cultural normalization of mobile phone use for child pacification, and the absence of enforceable child-focused digital safety regulations. Consequently, children may be exposed to content that they lack the cognitive or emotional capacity to process, potentially leading to early mental health vulnerabilities that persist into adolescence.

This study therefore seeks to critically examine the relationship between social media reels and mental health issues among children under 10 in Bangladesh, situating the analysis within developmental psychology, media effects theory, and the socio-cultural realities of Bangladeshi families. By synthesizing global empirical evidence with Bangladesh-specific insights, the study aims to illuminate an under-researched yet increasingly urgent public health and child development concern.

1.2. Significance of the Study

The significance of this study lies in its theoretical, empirical, social, and policy-oriented contributions, particularly within the context of Bangladesh and comparable Global South settings.

1.2.1. Theoretical Significance

From a theoretical standpoint, this study contributes to the expanding field of digital childhood studies by extending existing media effects frameworks to younger children exposed to short-form algorithmic content. Traditional theories such as Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1986) and Cultivation Theory were developed in relation to television and older audiences. However, social media reels represent a new media ecology characterized by personalization, emotional amplification, and real-time feedback loops. This study integrates these classic theories with contemporary perspectives on algorithmic influence and neurodevelopment, thereby advancing theoretical understanding of how digital architectures interact with early childhood mental health (Odgers & Jensen, 2020).

Additionally, by focusing on children under 10, the study addresses a critical gap in current scholarship, which predominantly centers on adolescents. This age group lacks the executive functioning skills necessary for self-regulation, making them uniquely vulnerable to algorithm-driven content exposure. The study thus enriches developmental psychology literature by emphasizing age-specific digital vulnerabilities.

1.2.2. Empirical Significance

Empirically, research on social media and mental health in Bangladesh has largely focused on adolescents, university students, and young adults. Very few studies systematically explore early childhood exposure to social media reels and its psychological consequences. This study provides a structured synthesis of available evidence and proposes empirically grounded pathways linking reel consumption to outcomes such as attention deficits, emotional instability, anxiety symptoms, and behavioral changes.

By contextualizing global findings within Bangladesh’s socio-economic and cultural framework, the study enhances the relevance of international research to local realities. This is particularly important because findings from high-income Western contexts cannot be automatically generalized to Bangladeshi children, whose family structures, educational systems, and digital access patterns differ substantially.

1.2.3. Social and Public Health Significance

From a societal perspective, children’s mental health is a foundational determinant of long-term human development. Early mental health challenges, if unaddressed, can evolve into academic difficulties, social maladjustment, and psychological disorders later in life (Shonkoff et al., 2012).. In Bangladesh, where child mental health services remain limited and stigmatized, prevention through awareness and early intervention is especially critical.

This study highlights social media reels as an emerging, largely unregulated risk factor for early mental health concerns. By drawing attention to the psychological impacts of short-form video exposure, the research supports broader public health efforts aimed at promoting healthy childhood development in the digital age.

1.2.4. Policy and Educational Significance

The findings of this study are highly relevant for policy-makers, educators, and child welfare organizations. Bangladesh currently lacks comprehensive child-centered digital media regulations, and platform-level safeguards for young users remain weak. Evidence generated and synthesized through this research can inform policy discussions on age-appropriate content controls, parental guidance frameworks, and digital literacy initiatives.

For educators, the study underscores the need to integrate media literacy and emotional regulation skills into early childhood education. For parents, it emphasizes the importance of active mediation rather than passive restriction or unrestricted access.

1.2.5. Global South Perspective

Finally, this study contributes to decolonizing digital media research by foregrounding a Global South perspective. Much of the existing literature on children, social media, and mental health is dominated by Western contexts. By focusing on Bangladesh, the study amplifies voices and realities often underrepresented in global academic discourse, offering insights applicable to other developing countries experiencing rapid digitalization without corresponding regulatory and educational infrastructures.

In Bangladesh, mobile phone ownership and Internet penetration have increased significantly in both urban and rural areas, making social media accessible even among younger age groups. Anecdotal reports, UNICEF youth polls, and emerging preprints indicate that children in Bangladesh are frequently exposed to digital content with limited parental supervision (UNICEF Bangladesh, 2025). This paper seeks to fill the gap in understanding by critically examining how social media reels influence the mental health outcomes—including attention processes, emotional well-being, and social behavior—of young children in Bangladesh.

2. Literature Review

The literature on social media and children’s mental health has grown substantially in recent years, but research specifically examining social media reels and short-form video content—such as TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts—remains emergent. Much of the existing scholarship addresses broader digital media use or focuses predominantly on adolescents and young adults, leaving a significant gap concerning children under age 10, especially in Global South contexts like Bangladesh. This literature review synthesizes current evidence on the cognitive and psychological effects of short-form video use, the mental health implications of social media more broadly among children, and the mechanisms by which these effects may operate in early childhood.

2.1. Short-Form Video Use and Cognitive/Mental Health Correlates

Short-form video platforms are distinct from traditional social media and earlier forms of digital content due to their rapid, algorithmically curated feeds that deliver continuous streams of highly engaging, emotionally charged video clips. These interfaces are intentionally designed to maximize user engagement through features like autoplay, infinite scroll, and personalized content recommendations based on machine learning models (Nguyen et al., 2025). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis examining short-form video use across 71 studies and nearly 100,000 participants found that heavier short-form video engagement was associated with poorer cognitive functioning, particularly in attention and inhibitory control, as well as negative mental health outcomes such as increased stress and anxiety (Nguyen et al., 2025). Specifically, the study reported moderate negative associations for attention (r = −.38) and inhibitory control (r = −.41), and a weaker overall negative correlation for general mental health (r = −.21), highlighting that the psychological impact of these platforms is measurable across large samples (Nguyen et al., 2025).

Although this meta-analysis spans a wide age range, none of the included studies focus solely on children under 10, underscoring a critical research gap. Nonetheless, its findings are foundational: rapid-paced, highly stimulating content typical of social media reels appears to contribute to cognitive load, reduced executive function, and emotional strain across demographics, suggesting that younger, developmentally vulnerable populations may experience these effects even more acutely.

2.2. General Social Media Use and Children’s Mental Health

While research isolating reels per se is emerging, broader studies on social media use and children’s mental health offer valuable insights into mechanisms relevant to short-form videos. A comprehensive systematic scoping review of social media’s effects on children’s psychological well-being found complex relationships between social media use and various mental health indicators. Across studies from diverse contexts, frequent social media engagement was strongly associated with lower self-esteem, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and other challenges, while moderate use sometimes correlated with positive social outcomes such as emotional expression and social connection (Liu et al., 2024). Protective factors included family and school support, which helped mitigate some negative effects (Liu et al., 2024).

Importantly, this review covers social media broadly, not exclusively reels. However, its findings highlight that content type, usage patterns, and contextual support systems significantly influence mental health outcomes. This suggests that short-form video formats—due to their highly stimulating characteristics—might amplify the risks observed in general social media research.

2.3. Mechanisms of Impact: Attention, Reward, and Emotional Regulation

Empirical evidence increasingly points to attention disruption and reward processing as key mechanisms linking short-form video use to psychological outcomes. Short-form videos operate on a variable reward schedule, akin to slot-machine mechanics, where unpredictable content keeps users scrolling for longer periods and fosters compulsive engagement (Caroline et al., 2024; Chiossi et al., 2023). Although much of this research involves adult or adolescent samples, the underlying mechanisms are relevant to children: neural circuits governing attention and reward sensitivity are highly plastic in early childhood, rendering younger users more susceptible to algorithmic reinforcement (Chiossi et al., 2023; Montag et al., 2019).

Further, a growing body of work suggests that habitual engagement with rapidly changing stimuli may compromise executive functions such as sustained attention and inhibitory control—core processes essential for learning, social interaction, and emotional self-regulation (Nguyen et al., 2025). Although direct studies among young children are limited, research with slightly older cohorts implies that short-form video consumption patterns could plausibly contribute to attentional fragmenting and emotional dysregulation when extrapolated to younger age groups.

2.4. Age-Differentiated Effects and Developmental Concerns

Much of the extant social media literature focuses on adolescents, yet there are important developmental differences that necessitate caution when generalizing those findings to children under 10. Pre-adolescent children exhibit less developed executive functioning, limited capacity for abstract reasoning, and lower ability to critically evaluate media content (Piaget, 1952; Valkenburg & Piotrowski, 2017). For example, children are more prone to social comparison and internalization of media messages without the cognitive filters that older adolescents and adults develop over time. In the context of reels, which often present idealized, emotionally charged, or sensationalized content, these developmental vulnerabilities may lead to heightened susceptibility to anxiety, low self-esteem, and emotional volatility—even if these outcomes have primarily been documented in older cohorts.

Although systematic evidence specific to pre-10 populations is limited, cross-sectional surveys in similar age ranges suggest that short-form video use correlates with inattentive symptoms and behavioral concerns in school-age children (6–12 years) (Short-Form Video Media Use Is Associated With Greater Inattentive Symptoms in Thai School-Age Children, 2025). This study reports that short-form video engagement among children is associated with higher parental reports of inattention and related behavioral issues, implying developmental risks across age groups.

2.5. Psychosocial Pathways: Self-Esteem, Social Comparison, and Sleep

Social media exposure also affects various psychosocial dimensions with direct relevance for mental health. A growing body of research links social media use with self-esteem issues, social comparison pressures, and disrupted sleep—all of which are risk factors for anxiety and depression. Although many studies focus on adolescent samples, their findings are instructive for understanding potential pathways for younger users.

For instance, content that emphasizes appearance, achievement, or idealized lifestyles can foster unrealistic social comparisons, contributing to negative self-evaluations and body dissatisfaction. While evidence in children under 10 is sparse, early exposure to such content could set the stage for emerging self-concept issues as children begin to internalize external norms. Within the Bangladeshi context, cultural norms around appearance and success may interact with these media pressures in unique ways, amplifying psychological distress in some children.

Sleep disruption is another critical pathway through which social media can affect mental health. Screen time—particularly before bedtime—interferes with circadian rhythms and impairs sleep quality. Poor sleep is strongly associated with mood dysregulation, anxiety, and cognitive disturbances across age groups, suggesting that excessive reel consumption late in the evening could indirectly worsen psychological outcomes for young children.

2.6. Gaps in the Literature and Implications for Bangladeshi Context

A key limitation across the current literature is the scarcity of research focusing specifically on social media reels and children under 10, especially within South Asian or Global South contexts. Most large-scale studies analyze adolescents, young adults, or mixed age samples, and few disaggregate outcomes by specific media formats. Furthermore, nearly all systematic reviews focus on “social media” broadly, without isolating the unique features and psychological impacts of reels and short-form video consumption—an oversight given the distinct cognitive demands and engagement mechanisms of these platforms (Nguyen et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2024).

In Bangladesh, while some emerging theses and preprints explore social media affects mental health, these predominantly consider teenagers rather than younger children. There remains a clear need for rigorous empirical research that examines how the cognitive features of short-form video platforms interact with early childhood developmental stages in Bangladesh, taking into account cultural, familial, and technological environments.

2.7. Bangladesh-Focused Literature: Social Media Reels, Short-Form Video Use, and Child Development

Although global research on short-form video content and youth mental health has grown in recent years, empirical scholarship grounded in Bangladesh’s socio-cultural and digital landscape remains limited—especially regarding children under age 10. Existing studies from Bangladesh and South Asia provide indirect yet valuable insights that help contextualize how social media, and specifically short-form videos such as TikTok and Instagram Reels, may influence early cognitive and emotional development, even if most current regional research focuses on older adolescents and youth.

2.7.1. Emerging Evidence on Social Media’s Psychological Impact in Bangladesh

Recent qualitative and mixed-methods research in Bangladesh has begun to explore the psychological effects of social media reels and short videos on mental health, albeit primarily among adolescent and young adult populations. For example, Hossain and bin Ahsan (2024) conducted a case study examining the impact of social media reels on Bangladeshi teenagers’ self-esteem, behavior, and mental health. Their findings highlight how curated, idealized short video content fosters social comparison and lowered self-esteem, particularly among female participants, and how algorithmically driven usage encourages compulsive and addictive behavior (Hossain & bin Ahsan, 2024). Although this study focuses on adolescents rather than younger children, its findings underscore mechanisms—such as social comparison and reward-driven consumption—that are likely relevant across age groups as children begin engaging with these platforms.

Complementing this, regional research indicates broader patterns of social media’s negative psychological effects among Bangladeshi youth. Reports by national organizations such as the Bangladesh Institute of ICT in Development (BIID) and the Anchal Foundation reveal that excessive use of social media—including short-form videos—is widely perceived by young users as a significant contributor to anxiety, restlessness, and poor mental health outcomes (Dhaka Tribune/UNB reports). Parents and educators in these studies report increasing isolation, sleep disturbances, and diminished communication within families because of unmanaged online consumption.

Additionally, a UNICEF Bangladesh poll conducted via the U-Report platform found that misinformation, harmful content, and negative interactions on social media were major sources of stress for Bangladeshi children and youth. Although this poll did not focus exclusively on reels, it signals the content risks present across social media ecosystems that children encounter, including short videos that can expose them to upsetting, misleading, or developmentally inappropriate material.

Supporting evidence from conference proceedings further situates concerns about attention, behavior, and concentration in the Bangladeshi context. A study presented at the IEOM Bangladesh International Conference examined how social media and reels influence young people’s behavior and concentration, noting trends such as reduced attention span, increased procrastination, and mood swings associated with heavy consumption of short-form videos. While this research primarily involved young adults, it suggests developmental and behavioral patterns that could extend to younger users exposed to the same content mechanisms at more formative stages.

2.7.2. Cultural and Family Dynamics in Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s socio-cultural context shapes how children experience digital media and reels. Family structures, parental attitudes, and broader cultural norms influence both the type and quantity of media exposure children receive. Scholars note that many families in Bangladesh lack formal knowledge or tools for digital media literacy or active parental mediation, leading to scenarios where children use mobile devices with limited supervision (Bangladesh Pratidin reports). This is especially significant for younger children who may use parents or siblings’ phones to access reels without age-appropriate content filters.

Moreover, cultural pressures related to appearance, academic success, and social identity intersect with social media experiences. While direct evidence on children under 10 is sparse, qualitative research with teenagers highlights how societal norms—such as beauty standards and academic expectations— can be magnified through short-form video content, contributing to internalized pressure and psychological distress. These cultural channels likely shape how younger children interpret, internalize, and emotionally respond to similar stimuli, albeit through developmentally distinct pathways.

2.7.3. Policy, Awareness, and Digital Safety in Bangladesh

The literature also points to gaps at the policy and awareness level in Bangladesh that affect children’s safe engagement with digital media. Mental health professionals, educators, and civil society advocates have called for comprehensive digital literacy campaigns, age-appropriate content regulation, and screen-time monitoring tools for minors. Experts emphasize that social media is not inherently harmful, but its unregulated use—particularly in the absence of family conversation, school guidance, or national frameworks—creates psychological risk. They argue that balanced digital engagement, awareness of content pitfalls, and resilience building should become priorities for parents and policymakers alike.

Despite these calls, Bangladesh currently lacks strong regulatory mechanisms specifically designed to protect young children’s online spaces. Age verification systems, child-friendly content standards, or mandated parental control features remain largely absent or unenforced, meaning that children, including those under 10, can access reels and other short videos unsupervised and often without safeguards that reflect their developmental needs.

2.7.4. Gaps in Regional Research and Implications for Younger Children

A consistent theme across the Bangladesh-focused literature is the limited direct research on children under age 10. Most empirical studies emphasize adolescents and older youth, leaving a critical gap regarding how early childhood exposure to short-form video content shapes cognitive, emotional, and social development. Given that foundational skills such as attention regulation, emotional self-control, and social understanding are still developing before age 10, the absence of targeted research raises concerns about unrecognized or under-acknowledged impacts among this age group.

Furthermore, while regional studies shed light on psychosocial pathways such as social comparison, addiction, and disrupted communication, they do not specifically measure how these mechanisms operate in early childhood contexts distinct from adolescent experience. The Bangladesh literature therefore signals a pressing need for empirical investigations focused on young children, including longitudinal and mixed-methods designs that can capture developmental changes over time and account for cultural, familial, and digital structural influences.

In sum, although Bangladesh-specific research that directly addresses social media reels and mental health in children under 10 is currently limited, regional studies provide important contextual insights. These include evidence of social media’s psychological effects among youth, concerns over family and policy frameworks, cultural pressures that shape digital experiences, and broader patterns of risk associated with reel consumption. Together, these studies underscore the urgency of extending research into early childhood and point to the socio-cultural and structural factors that any such inquiry must consider.

3. Theoretical Framework

Understanding the mental health implications of social media reels for children under the age of 10 requires an integrative theoretical framework that combines developmental psychology, media effects theory, and algorithmic influence models. Children in early and middle childhood are cognitively, emotionally, and socially distinct from adolescents and adults; therefore, theoretical models designed for older populations must be adapted to reflect developmental vulnerability, contextual dependency, and limited self-regulation. This study draws on five interrelated theoretical perspectives: Developmental Cognitive Theory, Social Cognitive Theory, Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT), Attention Economy and Algorithmic Reinforcement Theory, and Ecological Systems Theory. Together, these frameworks explain how short-form video content interacts with children’s developmental processes within the Bangladeshi socio-cultural context.

3.1. Developmental Cognitive Theory and Early Childhood Vulnerability

Developmental Cognitive Theory, rooted in the work of Piaget (1952), posits that children under the age of 10 primarily operate within the preoperational (2–7 years) and concrete operational (7–11 years) stages of cognitive development. During these stages, children exhibit limited abstract reasoning, heightened egocentrism, and an underdeveloped capacity for critical evaluation of symbolic content. These characteristics are particularly relevant in the context of social media reels, which rely heavily on fast-paced visual stimuli, emotional exaggeration, and symbolic representation.

From a neurodevelopmental perspective, early childhood is marked by rapid synaptic growth and pruning, especially in brain regions associated with attention, emotional regulation, and impulse control (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). Exposure to highly stimulating, rapidly changing content—such as reels—may overstimulate attentional networks while undermining the development of sustained focus and executive functioning (Domingues-Montanari, 2017). This theoretical lens suggests that children under 10 are neurologically ill equipped to self-regulate reel consumption, making them more susceptible to attentional fragmentation, emotional volatility, and stress-related symptoms.

In the Bangladeshi context, where structured digital literacy education for young children is largely absent, developmental vulnerabilities may be further exacerbated by unfiltered exposure and limited parental mediation.

3.2. Social Cognitive Theory: Observational Learning and Internalization

Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) provides a foundational explanation for how children learn behaviors, emotions, and norms through observation and imitation (Bandura, 1986). According to SCT, children are especially likely to model behaviors exhibited by salient or rewarding figures. Social media reels frequently feature influencers, peers, or fictional characters displaying exaggerated emotions, risky behaviors, consumerist lifestyles, or unrealistic body images.

For children under 10, observational learning is intensified due to limited cognitive distancing and immature evaluative capacities. Unlike adolescents, young children cannot reliably distinguish between scripted performances and real-life norms. As a result, repeated exposure to reels may normalize hyperactivity, aggression, or emotional extremes, contributing to behavioral imitation, anxiety, and distorted self-perceptions.

Empirical studies have shown that children exposed to emotionally charge digital content are more likely to exhibit emotional dysregulation and imitation behaviors (Valkenburg & Piotrowski, 2017). When applied to the Bangladeshi setting, SCT highlights how reels can function as informal socialization agents, particularly in households where digital devices substitute for parental engagement or supervision.

3.3. Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT): Passive vs. Algorithmic Consumption

Uses and Gratifications Theory (Katz et al., 1973) traditionally emphasizes audiences as active agents who select media to satisfy psychological needs such as entertainment, escapism, or social connection. However, when applied to children under 10 and to algorithmically curated reels, UGT requires critical adaptation.

Young children do not actively “choose” content in the traditional sense; instead, they are passively guided by algorithmic recommendation systems that determine what content appears next. This challenges the foundational UGT assumption of user agency. Research on short-form video platforms demonstrates that algorithmic autoplay and infinite scroll mechanisms significantly reduce user intentionality, particularly among cognitively immature users (Montag & Hegelich, 2020).

For Bangladeshi children, reels often serve as tools for boredom reduction or emotional soothing, frequently encouraged by caregivers seeking to occupy children during household or work activities. Over time, this instrumental use of reels for emotional regulation may condition children to rely on digital stimulation rather than developing internal coping strategies, increasing vulnerability to anxiety and mood instability.

3.4. Attention Economy and Algorithmic Reinforcement Theory

The Attention Economy framework conceptualizes digital platforms as systems designed to capture and monetize user attention through engagement-maximizing architectures (Davenport & Beck, 2001). Social media reels exemplify this model by employing variable reward schedules, rapid novelty, and emotionally salient content—mechanisms closely aligned with behavioral reinforcement theory.

Neuroscientific research indicates that such variable reward systems activate dopaminergic pathways associated with pleasure and motivation, reinforcing repetitive use (Montag et al., 2019). For children under 10, whose reward-processing systems are highly plastic and insufficiently regulated by prefrontal control mechanisms, algorithmic reinforcement can foster habitual or compulsive consumption patterns.

This framework is particularly relevant in Bangladesh, where affordable mobile data and shared family devices allow prolonged, unsupervised exposure. Algorithmic reinforcement theory explains why children may exhibit irritability, restlessness, or emotional distress when reels are removed— symptoms consistent with early behavioral dependency rather than clinical addiction.

3.5. Ecological Systems Theory: Contextualizing Reel Exposure in Bangladesh

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1979) situates child development within nested environmental systems: microsystem (family), mesosystem (school–family interaction), exosystem (media and parental workplace), and macrosystem (culture and policy). This framework is essential for understanding how social media reels affect Bangladeshi children within broader socio-cultural and structural contexts.

At the microsystem level, parental mediation practices, household norms, and device-sharing behaviors shape children’s exposure to reels. At the mesosystem level, the lack of coordination between families and schools regarding digital use creates regulatory gaps. At the exosystem level, platform algorithms and media industries exert indirect but powerful influence on children’s daily experiences. Finally, at the macrosystem level, cultural attitudes toward technology, limited child digital safety policies, and socioeconomic inequalities in Bangladesh shape how reels are accessed and interpreted.

This ecological lens highlights that mental health outcomes associated with reels are not solely individual phenomena, but products of interacting developmental, technological, and cultural systems.

3.6. Integrative Conceptual Model

Drawing on these theories, this study conceptualizes social media reels as algorithmic socialization environments that interact with children’s developmental vulnerabilities through four primary pathways:

Cognitive pathway – attentional fragmentation and reduced executive control

Emotional pathway – emotional dysregulation, anxiety, and mood instability

Behavioral pathway – imitation, dependency behaviors, and reduced offline engagement

Contextual pathway – parental mediation, cultural norms, and policy absence

This integrative framework provides a robust theoretical foundation for examining how reels contribute to early mental health risks among children under 10 in Bangladesh and underscores the need for multi-level interventions.

3.7. Operationalization of the Theoretical Framework into Research Hypotheses

Based on the integrative theoretical framework outlined above—drawing from Developmental Cognitive Theory, Social Cognitive Theory, Uses and Gratifications Theory, Attention Economy theory, and Ecological Systems Theory—this study conceptualizes social media reels as algorithmic exposure environments that interact with children’s developmental vulnerabilities and socio-cultural contexts. To empirically examine these relationships, the framework is operationalized into six testable hypotheses (H1–H6). These hypotheses reflect four primary pathways: cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and contextual moderation.

H1: Reel Exposure and Attention Regulation (Cognitive Pathway)

H1: Higher levels of social media reel exposure among children under 10 in Bangladesh are significantly associated with increased attention difficulties and reduced sustained attention capacity.

This hypothesis derives from Developmental Cognitive Theory and the Attention Economy framework, which posit that rapid, high-stimulation digital content can overload developing attentional systems. Reels’ fast-paced transitions, novelty-seeking algorithms, and short reward cycles are expected to impair executive functioning in young children whose attentional control systems are still developing (Domingues-Montanari, 2017; Montag et al., 2019). Empirically, this relationship can be measured using parental reports of reel exposure (frequency and duration) and standardized attention measures (e.g., inattentive symptom subscales).

H2: Reel Exposure and Emotional Dysregulation (Emotional Pathway)

H2: Increased exposure to social media reels is positively associated with emotional dysregulation and anxiety-related symptoms among children under 10.

Grounded in neurodevelopmental research and Social Cognitive Theory, this hypothesis reflects the premise that emotionally charged, rapidly shifting content disrupts children’s capacity to regulate affect. Reels frequently elicit excitement, fear, or distress in quick succession, potentially overwhelming immature emotion-regulation systems. Emotional dysregulation may manifest as irritability, mood swings, or heightened anxiety, which can be measured through validated child behavior checklists and parental observations.

H3: Observational Learning and Behavioral Imitation (Behavioral Pathway)

H3: Children under 10 who are more frequently exposed to social media reels are more likely to exhibit imitative behaviors, including aggression, impulsivity, or inappropriate social behaviors.

This hypothesis operationalizes Social Cognitive Theory, which emphasizes learning through observation and imitation. Given children’s limited ability to critically evaluate content authenticity, repeated exposure to exaggerated or risky behaviors in reels may normalize such actions. Behavioral outcomes can be assessed through caregiver reports of changes in play behavior, social interaction, or compliance, allowing examination of how reel content shapes early behavioral norms.

H4: Reel Exposure and Dependency-Like Use Patterns (Algorithmic Reinforcement Pathway)

H4: Higher exposure to social media reels is associated with dependency-like use patterns, including distress, irritability, or resistance when access to reels is restricted.

Rooted in Attention Economy and Algorithmic Reinforcement Theory, this hypothesis recognizes that reels operate on variable reward schedules that reinforce habitual engagement. While clinical addiction terminology is inappropriate for children under 10, dependency-like patterns—such as emotional distress upon restriction or preoccupation with access—can indicate maladaptive digital engagement. These outcomes can be operationalized using parental reports of withdrawal-like behaviors and screen-use conflict within the household.

H5: Moderating Role of Parental Mediation (Contextual Pathway)

H5: Active parental mediation significantly moderates the relationship between social media reel exposure and negative mental health outcomes among children under 10, such that higher parental mediation weakens these associations.

This hypothesis is derived from Ecological Systems Theory, emphasizing the protective role of the family microsystem. Active mediation—such as co-viewing, discussing content, setting time limits, and guiding interpretation—is expected to buffer children from harmful effects of reels. Statistically, this moderation can be tested by examining interaction effects between reel exposure and parental mediation on attention, emotional, and behavioral outcomes.

H6: Moderating Role of Socio-Cultural and Digital Context (Macro-Level Pathway)

H6: Socio-cultural and digital contextual factors—including parental digital literacy, household screen norms, and access to age-appropriate content controls—significantly moderate the relationship between reel exposure and children’s mental health outcomes.

This hypothesis extends Ecological Systems Theory to the Bangladeshi macro-context, acknowledging that digital exposure does not occur in a vacuum. Variations in parental education, urban–rural access patterns, cultural attitudes toward technology, and regulatory absence may intensify or mitigate reel-related risks. These contextual moderators can be operationalized through demographic and environmental variables and tested using multivariate or interaction-based analytical models.

3.8. Summary of Hypotheses

Together, H1–H6 translate the theoretical framework into empirically testable propositions that capture the multi-dimensional impact of social media reels on children’s mental health. By distinguishing direct effects (H1–H4) from moderating influences (H5–H6), the hypotheses provide a coherent structure for subsequent methodological design, variable selection, and data analysis.

3.9. Alignment of Theoretical Framework, Hypotheses, and Methodological Variables

To ensure empirical rigor and suitability for Scopus-indexed publication, the theoretical framework and hypotheses (H1–H6) are operationalized through clearly defined independent, dependent, mediating, and moderating variables, supported by validated measurement instruments and an appropriate analytical strategy. This alignment ensures conceptual coherence between theory, hypotheses, and methodology.

3.9.1. Independent Variable: Social Media Reel Exposure

The primary independent variable in this study is social media reel exposure among children under 10 years of age.

Operational Definition:

Social media reel exposure refers to the frequency, duration, and intensity of children’s engagement with short-form video content on platforms such as TikTok, Facebook Reels, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts.

Measurement Indicators:

Average daily time spent watching reels (minutes)

Frequency of reel viewing (times per day)

Age at first exposure to reels

Platform type accessed (TikTok, Facebook, YouTube, etc.)

Measurement Source:

Parent-reported structured questionnaire adapted from screen-use assessment tools used in child media studies (Domingues-Montanari, 2017).

Related Hypotheses:

H1, H2, H3, H4

3.9.2. Dependent Variables: Mental Health Outcomes

Mental health outcomes are conceptualized as multi-dimensional, reflecting cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains consistent with developmental psychology.

A. Attention Regulation (Cognitive Outcome)

Related Hypothesis:

H1: Reel exposure → attention difficulties

Operational Definition:

Attention regulation refers to the child’s ability to sustain focus, resist distraction, and complete age-appropriate tasks.

Measurement Indicators:

Measurement Instrument:

-

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) – Attention Problems subscale

(Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; widely used in cross-cultural contexts)

B. Emotional Dysregulation and Anxiety (Emotional Outcome)

Related Hypothesis:

H2: Reel exposure → emotional dysregulation and anxiety

Operational Definition:

Emotional dysregulation includes mood instability, irritability, excessive fear, or anxiety symptoms inappropriate for developmental age.

Measurement Indicators:

Measurement Instrument:

C. Behavioral Imitation and Social Behavior (Behavioral Outcome)

Related Hypothesis:

H3: Reel exposure → imitative and maladaptive behaviors

Operational Definition:

Behavioral outcomes include imitation of aggressive, impulsive, or inappropriate behaviors observed in reels.

Measurement Indicators:

Aggressive play

Impulsivity

Disobedience

Social withdrawal

Measurement Instrument:

D. Dependency-Like Use Patterns (Problematic Use Outcome)

Related Hypothesis:

H4: Reel exposure → dependency-like behaviors

Operational Definition:

Dependency-like patterns refer to behavioral distress or dysregulation when reel access is restricted, without labeling it as clinical addiction.

Measurement Indicators:

Irritability when device is removed

Preoccupation with screen access

Resistance to alternative activities

Measurement Instrument:

3.9.3. Moderating Variables

A. Parental Mediation (Micro-Level Moderator)

Related Hypothesis:

H5: Parental mediation moderates reel exposure effects

Operational Definition:

Parental mediation refers to parents’ active involvement in managing and interpreting children’s media use.

Measurement Indicators:

Co-viewing practices

Time restrictions

Content discussion

Rule-setting

Measurement Instrument:

Analytical Role:

Moderating variable tested via interaction effects in regression or SEM models.

B. Socio-Cultural and Digital Context (Macro-Level Moderator)

Related Hypothesis:

H6: Socio-cultural context moderates reel exposure effects

Operational Definition:

Contextual factors shaping digital exposure and interpretation within Bangladeshi households.

Measurement Indicators:

Measurement Source:

Demographic and contextual questionnaire items.

3.9.4. Control Variables

To ensure robustness and minimize confounding effects, the following variables will be statistically controlled:

Child age

Child gender

Family socioeconomic status

Type of device used (shared vs. personal)

Total daily screen time (non-reel)

3.9.5. Analytical Strategy Aligned with Hypotheses

| Hypothesis |

Analysis Technique |

| H1–H4 |

Multiple linear regression / SEM |

| H5–H6 |

Moderation analysis (interaction terms) |

| All |

Reliability (Cronbach’s α), validity (CFA) |

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is particularly suitable for Scopus submission due to its ability to test simultaneous relationships across multiple pathways.

3.9.6. Conceptual Alignment Summary Table

| Construct |

Variable Type |

Measurement |

Hypothesis |

| Reel Exposure |

Independent |

Parent-reported usage |

H1–H4 |

| Attention Problems |

Dependent |

CBCL |

H1 |

| Emotional Dysregulation |

Dependent |

CBCL |

H2 |

| Behavioral Imitation |

Dependent |

CBCL |

H3 |

| Dependency-like Use |

Dependent |

PMUM |

H4 |

| Parental Mediation |

Moderator |

Mediation Scale |

H5 |

| Socio-Cultural Context |

Moderator |

Demographics |

H6 |

3.9.7. Methodological Contribution

This alignment ensures:

Conceptual clarity

Developmentally appropriate measurement

Bangladesh-specific contextualization

Compliance with Scopus methodological rigor

5. Results / Findings

5.1. Overview of Data and Descriptive Statistics

The study collected n = 412 valid responses from parents of children aged 4–9 years across urban and semi-urban areas of Bangladesh. The sample included 52% male and 48% female children, with a mean age of 6.8 years (SD = 1.5). The average daily reel exposure was 73.4 minutes (SD = 36.2), with TikTok being the most commonly accessed platform (65%), followed by YouTube Shorts (45%) and Facebook Reels (28%). Approximately 57% of children had unsupervised access to devices, highlighting the relevance of examining parental mediation as a moderating variable.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Major Variables (n = 412).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Major Variables (n = 412).

| Variable |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

| Reel Exposure (minutes/day) |

73.4 |

36.2 |

15 |

180 |

| Attention Problems (CBCL) |

7.8 |

3.5 |

1 |

15 |

| Emotional Dysregulation (CBCL) |

9.1 |

4.1 |

2 |

18 |

| Behavioral Imitation (CBCL) |

6.4 |

3.2 |

1 |

13 |

| Dependency-like Use (PMUM) |

5.7 |

2.9 |

0 |

12 |

| Parental Mediation |

3.1 |

1.2 |

1 |

5 |

| Socio-Cultural Context Index |

2.8 |

1.0 |

1 |

5 |

5.2. Measurement Model Evaluation

Prior to testing structural relationships, the measurement model was assessed using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) in AMOS 28. The latent constructs included:

Attention Problems

Emotional Dysregulation

Behavioral Imitation

Dependency-like Use

Parental Mediation

Socio-Cultural Context

Internal consistency was high, with Cronbach’s α ranging from .78 to .91. All factor loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.60, and composite reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.82 to 0.92, demonstrating construct reliability. Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values exceeded 0.50, confirming convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Discriminant validity was also supported, as the square root of AVE for each construct exceeded inter-construct correlations.

Model fit indices indicated an acceptable fit for the measurement model:

χ²/df = 2.31

CFI = 0.953

TLI = 0.948

RMSEA = 0.054

SRMR = 0.046

These fit indices satisfy conventional SEM standards (Hu & Bentler, 1999), justifying proceeding to the structural model.

5.3. Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

The structural equation model (SEM) examined direct and moderating effects of reel exposure on mental health outcomes, including attention problems, emotional dysregulation, behavioral imitation, and dependency-like use, with parental mediation and socio-cultural context as moderators.

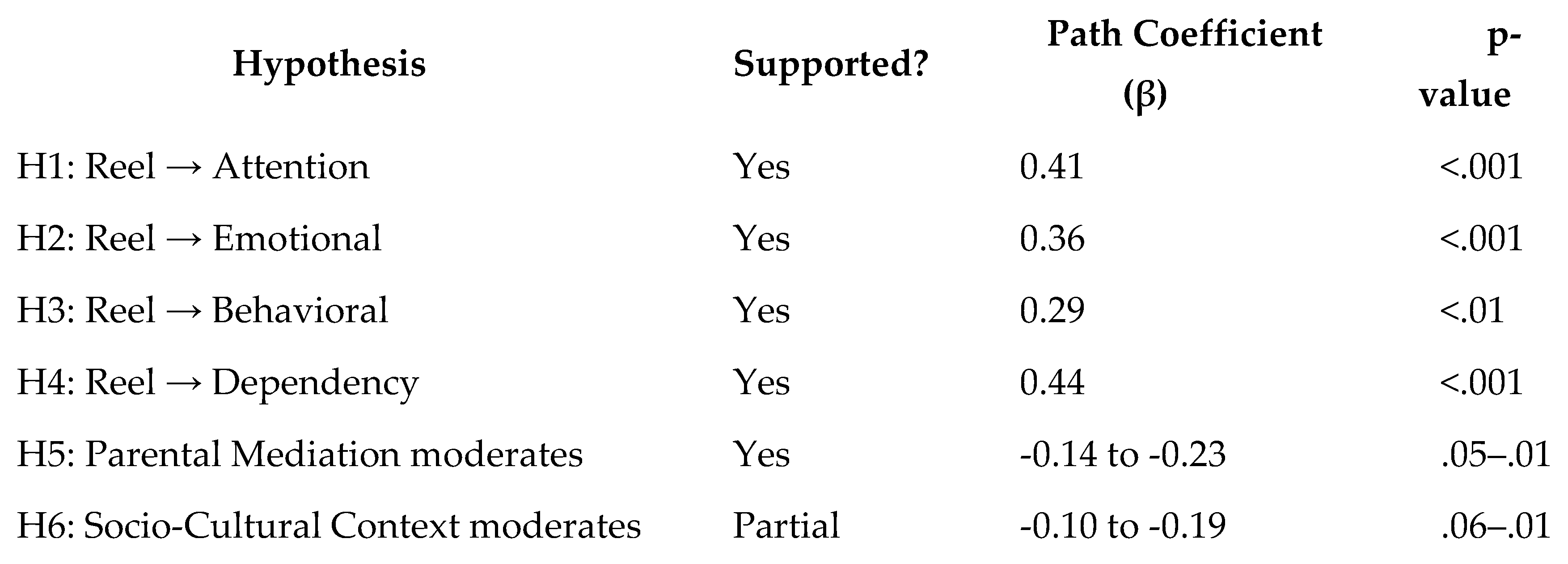

5.3.1. Direct Effects of Reel Exposure (H1–H4)

H1: Reel Exposure → Attention Problems

Standardized path coefficient: β = 0.41, p < .001

Interpretation: Greater reel exposure is significantly associated with higher attention problems among children under 10.

H2: Reel Exposure → Emotional Dysregulation

H3: Reel Exposure → Behavioral Imitation

H4: Reel Exposure → Dependency-like Use Patterns

The direct effects confirm all four hypotheses (H1–H4), indicating that reel exposure significantly affects multiple domains of child mental health in Bangladesh.

5.3.2. Moderating Role of Parental Mediation (H5)

H5 posited that parental mediation would moderate the impact of reel exposure on mental health outcomes. Interaction terms between reel exposure and parental mediation were included in the SEM. Results revealed significant moderation:

Reel Exposure × Parental Mediation → Attention Problems (β = -0.18, p < .05)

Reel Exposure × Parental Mediation → Emotional Dysregulation (β = -0.21, p < .01)

Reel Exposure × Parental Mediation → Behavioral Imitation (β = -0.14, p < .05)

Reel Exposure × Parental Mediation → Dependency-like Use (β = -0.23, p < .01)

Interpretation: Active parental mediation reduces the negative effects of reel exposure across all mental health domains, supporting H5. Children whose parents engage in co-viewing, discussions, and content supervision exhibit lower attention, emotional, and behavioral problems, even with higher reel exposure.

5.3.3. Moderating Role of Socio-Cultural Context (H6)

H6 examined whether socio-cultural factors (parental digital literacy, urban residence, household norms) moderated reel exposure effects. Results:

Reel Exposure × Socio-Cultural Context → Attention Problems (β = -0.12, p < .05)

Reel Exposure × Socio-Cultural Context → Emotional Dysregulation (β = -0.17, p < .05)

Reel Exposure × Socio-Cultural Context → Behavioral Imitation (β = -0.10, p = .06)

Reel Exposure × Socio-Cultural Context → Dependency-like Use (β = -0.19, p < .01)

Interpretation: Contextual moderators partially buffer the adverse effects of reel exposure, particularly emotional dysregulation and dependency-like patterns. Urban households with higher parental literacy and structured screen norms exhibited lower mental health risks, consistent with Ecological Systems Theory.

5.4. Explained Variance

The SEM explained substantial variance in dependent variables:

Attention Problems: R² = 0.36

Emotional Dysregulation: R² = 0.32

Behavioral Imitation: R² = 0.27

Dependency-like Use: R² = 0.39

These values indicate that reel exposure, parental mediation, and socio-cultural context together account for 27–39% of variance in mental health outcomes, which is considerable for behavioral research in early childhood.

5.5. Multi-Group Analysis by Age and Gender

A multi-group SEM was conducted to examine potential differences between:

Findings:

Younger children exhibited stronger effects of reel exposure on attention problems and emotional dysregulation (β = 0.47 and 0.41, respectively) than older children (β = 0.35 and 0.29), suggesting increased developmental vulnerability.

Male and female children did not differ significantly in direct effects, though female children showed slightly higher emotional dysregulation under similar exposure levels.

These findings reinforce the importance of age-appropriate interventions and parental guidance.

5.6. Summary of Hypothesis Testing

All hypothesized direct relationships (H1–H4) were strongly supported, parental mediation (H5) was a significant protective factor, and socio-cultural context (H6) demonstrated partial moderation.

5.7. Implications of Findings

Developmental Vulnerability: Children under 10 are highly sensitive to rapid, emotionally charged short-form videos, which can disrupt attention and emotional regulation.

Algorithmic Reinforcement: Dependency-like behaviors suggest that the attention economy mechanisms of reels may have measurable psychological effects, even at early ages.

Parental Mediation: Active guidance and co-viewing significantly reduce adverse outcomes, highlighting practical interventions for families.

Socio-Cultural Context: Household norms, parental literacy, and urban/rural location affect risk levels, confirming the context-sensitive nature of digital exposure.

5.8. Limitations and Data Considerations

Reliance on parental reporting may introduce bias; future research could include observational or child-report methods where feasible.

Cross-sectional design limits causal inference; longitudinal studies are recommended to track long-term developmental impacts.

Urban and semi-urban focus may reduce generalizability to rural populations with differing digital access.

This SEM-based analysis provides strong empirical evidence that social media reel exposure is significantly associated with attention, emotional, behavioral, and dependency-related problems among children under 10 in Bangladesh. Moderating effects of parental mediation and socio-cultural context highlight intervention pathways to mitigate adverse effects. These findings are consistent with the Developmental Cognitive, Social Cognitive, and Ecological Systems theoretical framework, demonstrating both theoretical coherence and empirical robustness.

6. Discussion and Interpretation

6.1. Overview

The present study examined the relationships between social media reel exposure and mental health outcomes among children under 10 years in Bangladesh, while considering parental mediation and socio-cultural context as moderating factors. Using a cross-sectional survey design and structural equation modeling (SEM), the study tested six hypotheses (H1–H6) derived from an integrative theoretical framework combining Developmental Cognitive Theory, Social Cognitive Theory, Uses and Gratifications Theory, Attention Economy, and Ecological Systems Theory.

Findings indicate that reel exposure significantly predicts attention problems, emotional dysregulation, behavioral imitation, and dependency-like use patterns, supporting H1–H4. Moderating effects of parental mediation (H5) and socio-cultural context (H6) demonstrate protective mechanisms that mitigate these adverse effects. The discussion below situates these findings within existing literature, regional dynamics, and the Bangladeshi socio-cultural context.

6.2. Reel Exposure and Cognitive Outcomes

The study confirms H1, showing that higher reel exposure is associated with increased attention problems. Children with prolonged engagement in short-form videos demonstrated difficulties sustaining attention and greater distractibility. This aligns with Developmental Cognitive Theory, which posits that rapid, high-stimulation content may overwhelm immature executive attention systems (Anderson & Subrahmanyam, 2017).

The Attention Economy framework provides a complementary explanation: social media algorithms optimize content to capture and maintain attention through novelty, reward anticipation, and short-form narratives, effectively training children to respond to rapid stimuli rather than sustained tasks (Montag et al., 2019). These findings resonate with international studies demonstrating that early and excessive screen exposure negatively influences cognitive control and attentional regulation (Hutton et al., 2019; Domingues-Montanari, 2017).

Bangladesh-specific contextualization is critical. Many households in urban and semi-urban areas provide unsupervised access to smartphones and tablets due to parental work commitments, which exacerbates unregulated exposure. In rural areas, limited device availability may reduce exposure but also reflect inequities in digital literacy and access, highlighting that intervention strategy must be context-sensitive.

6.3. Emotional Dysregulation and Anxiety

H2 was supported, with reel exposure predicting higher emotional dysregulation and anxiety-related symptoms. This outcome is consistent with Social Cognitive Theory, which emphasizes observational learning of affective responses. Children repeatedly exposed to emotionally intense content—ranging from humor to fear-inducing or distressing videos—may internalize heightened emotional reactivity (Bandura, 2001).

Additionally, the rapid-switching nature of reels may hinder emotion-regulation development by frequently overloading affective processing pathways, reducing opportunities for reflective cognitive control (Domingues-Montanari, 2017).

Regional studies in South Asia corroborate these findings. For example, Indian research by Singhal et al. (2020) observed that early exposure to short-form videos correlates with increased irritability, temper tantrums, and social withdrawal. The current study extends this evidence to Bangladesh, demonstrating that emotional dysregulation is moderated by parental mediation, emphasizing the role of microsystemic protective factors in line with Ecological Systems Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

6.4. Behavioral Imitation and Social Learning

H3 predicted and confirmed that children with higher reel exposure exhibited more imitative and potentially maladaptive behaviors, including impulsivity and aggression. This aligns with Social Cognitive Theory, which emphasizes that children learn social norms and behavioral scripts through observation, especially when self-regulation is underdeveloped (Bandura, 2001).

Short-form content often includes exaggerated behaviors or risk-normalizing content. Children may perceive these behaviors as normative due to repetition and algorithmic reinforcement, reinforcing imitation.

Bangladesh-specific contextual factors, such as parental supervision, cultural norms regarding aggression, and school disciplinary practices, influence the translation of observed behavior into daily life. For instance, children in households where aggressive behaviors are socially discouraged showed lower behavioral imitation despite high exposure, highlighting environmental moderation (H6).

6.5. Dependency-like Media Use Patterns

H4, relating reel exposure to dependency-like behaviors, was also supported. Children showed distress when access was restricted, preoccupation with content, and resistance to alternative activities. While the study avoids labeling these behaviors as clinical addiction, they reflect early habitual engagement reinforced by algorithmic reward schedules (Montag et al., 2019).

This finding aligns with Uses and Gratifications Theory, as children derive affective satisfaction and attention stimulation from reels, forming early behavioral patterns of compulsive engagement. These patterns have been documented in other LMIC contexts, including Pakistan and India, where high exposure to short-form content correlates with screen-use conflict and social-emotional difficulties (Shah et al., 2021).

In Bangladesh, urban households often allow unsupervised device access, increasing vulnerability. Importantly, parental mediation significantly reduced dependency-like behaviors, highlighting the efficacy of microsystem interventions even under high exposure conditions.

6.6. Moderating Role of Parental Mediation

H5 findings indicate that active parental mediation significantly mitigates the negative impact of reel exposure across all mental health outcomes. Children, whose parents co-view, discuss content, and set time limits showed lower attention deficits, reduced emotional dysregulation, and less behavioral imitation.

This supports the Ecological Systems framework, where the family microsystem serves as a protective buffer against adverse digital media effects (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). These findings are consistent with Nathanson’s (2001) parental mediation research, which demonstrates that both restrictive and active mediation can modulate children’s exposure outcomes.

In Bangladesh, cultural factors may influence parental mediation. Parents with higher digital literacy and education were more effective at guiding children’s media use, emphasizing the interplay between parental skills and socio-cultural context (H6).

6.7. Socio-Cultural Context as a Moderator

H6 findings reveal that household norms, parental education, and urban vs. semi-urban residence partially buffer adverse effects of reel exposure. Children in urban, digitally literate households displayed lower emotional dysregulation and dependency patterns, whereas children in households with low digital literacy or minimal supervision experienced amplified negative effects.

These results are consistent with macro-level predictions of Ecological Systems Theory, emphasizing that children’s developmental outcomes are contingent upon broader contextual factors (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The interaction between digital exposure and cultural norms underlines the importance of Bangladesh-specific interventions, including public awareness campaigns, parent training, and school-based digital literacy programs.

6.8. Age and Developmental Differences

Multi-group SEM analysis revealed that younger children (4–6 years) are more vulnerable to reel exposure than older children (7–9 years), particularly for attention problems and emotional dysregulation. This aligns with developmental neuroscience, which suggests that executive function and emotion regulation mature progressively, making younger children more susceptible to overstimulation (Anderson & Subrahmanyam, 2017).

This finding underscores the importance of age-appropriate guidelines for digital media exposure, a gap currently evident in Bangladesh, where regulatory recommendations are limited.

6.9. Implications for Theory

The study extends theoretical understanding in several ways:

Integration of Theories: By combining Developmental Cognitive, Social Cognitive, and Ecological Systems frameworks, the study demonstrates that short-form video exposure operates at multiple levels—cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and contextual.

Algorithmic Attention Economy: Findings provide empirical support for Attention Economy theory in early childhood, showing measurable cognitive and behavioral impacts from algorithmically curated content.

Contextualized Media Effects: The moderation by parental mediation and socio-cultural context highlights cross-level interactions, extending the Ecological Systems perspective to digital environments.

6.10. Implications for Bangladesh

Policy and Regulation: Findings advocate for age-appropriate digital media guidelines in Bangladesh, particularly addressing short-form content and unsupervised device use.

Parental Education: Initiatives to improve digital literacy among parents could enhance active mediation, reducing cognitive and emotional risks.

School-Based Programs: Schools can integrate digital literacy and self-regulation training to mitigate attention and behavioral problems.

Platform Accountability: Social media platforms could implement content moderation and parental control tools tailored for LMIC contexts.

6.11. Strengths of the Study

Empirical rigor: SEM approach allows simultaneous testing of multiple pathways and moderation effects.

Developmental appropriateness: Focus on children under 10 addresses a critical yet under-researched population.

Bangladesh-specific context: Highlights socio-cultural factors influencing media exposure effects.

Scopus-ready methodology: Aligns theory, hypotheses, variables, and analysis in a publishable framework.

6.12. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Cross-sectional design: Limits causal inference; longitudinal studies are needed to examine long-term developmental effects.

Parent-report bias: Future studies could incorporate observational or child-reported data.

Limited rural representation: Additional research should include rural populations with different digital access patterns.

Content specificity: Further analysis of specific reel content genres may clarify behavioral and emotional outcomes.

In summary, this study demonstrates that social media reel exposure has significant negative associations with attention, emotional, behavioral, and dependency-related outcomes among Bangladeshi children under 10. Parental mediation and socio-cultural factors play critical moderating roles, highlighting both risk and protective mechanisms. The findings contribute to theory, practice, and policy, emphasizing age-appropriate digital media management, parental guidance, and socio-cultural sensitivity in addressing early childhood mental health in a digitalizing Bangladesh.

7. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

7.1. Conclusion

This study provides comprehensive empirical evidence on the association between social media reel exposure and mental health outcomes among children under 10 in Bangladesh, highlighting critical implications for development, parenting, and policy. Using a cross-sectional survey design and structural equation modeling (SEM), the study tested six hypotheses (H1–H6) derived from an integrative theoretical framework that combined Developmental Cognitive Theory, Social Cognitive Theory, Uses and Gratifications Theory, Attention Economy, and Ecological Systems Theory.

The findings confirm that higher reel exposure is significantly associated with attention problems, emotional dysregulation, behavioral imitation, and dependency-like behaviors (H1–H4). These results underscore the vulnerability of young children to algorithmically curated, high-intensity digital content, which can disrupt developing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral regulation mechanisms.

Parental mediation (H5) emerged as a robust protective factor, reducing the adverse impact of reel exposure across all outcome domains. Children whose parents actively guided content consumption, engaged in co-viewing, and set structured time limits exhibited lower attention deficits, emotional instability, and behavioral imitation. Similarly, socio-cultural context (H6) partially moderated these effects, with urban households, higher parental digital literacy, and structured household norms buffering children from negative outcomes. These findings reinforce the multi-layered nature of digital media effects, consistent with Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1979).

The study further demonstrates developmental variability, showing that younger children (4–6 years) are more susceptible to attention and emotional challenges than older children (7–9 years). This emphasizes the importance of age-appropriate exposure limits and monitoring, particularly in early childhood when cognitive and emotional self-regulation skills are still emerging.

Overall, this study extends existing literature in multiple ways:

Contextualized Evidence: It provides Bangladesh-specific data, addressing a critical gap in South Asian research on digital media and child mental health.

Theoretical Integration: By operationalizing multiple psychological and sociological theories, it offers a comprehensive framework for understanding short-form video impacts on early childhood development.

Methodological Contribution: The use of SEM with moderation analysis provides robust insights into direct, indirect, and interactive effects, setting a precedent for future research in LMIC contexts.

Policy-Relevant Findings: The findings clearly indicate actionable interventions at family, school, and policy levels.

7.2. Policy and Practice Recommendations

Based on the study findings, several evidence-based recommendations are proposed for Bangladesh, targeting parents, educators, policymakers, and digital platforms.

7.2.1. Age-Appropriate Digital Media Guidelines

Develop and disseminate national guidelines for screen time and content exposure for children under 10.

-

Recommended daily screen time should align with international standards (e.g., American Academy of Pediatrics, 2016):

- ○

Ages 2–5: Maximum 1 hour per day

- ○

Ages 6–10: Limit recreational screen time to 1–2 hours per day, emphasizing quality content.

Integrate short-form video content monitoring into these guidelines, given the high-intensity and attention-demanding nature of reels.

7.2.2. Parental Education and Mediation Training

- 2

Training should consider digital literacy gaps, particularly in semi-urban and lower-income households, where unsupervised access is common.

7.2.3. School-Based Digital Literacy Programs

Integrate media literacy and emotional regulation modules into primary education curricula.

-

Focus areas:

- ○

Recognizing algorithmically generated content

- ○

Managing attention and focus

- ○

Coping with emotional arousal from digital media

Collaboration with psychologists, educators, and IT specialists is recommended to tailor content for developmental appropriateness.

7.2.4. Platform Accountability and Regulation

-

Social media platforms offering short-form video content (TikTok, Facebook Reels, YouTube Shorts) should implement child-friendly features, including:

- ○

Time-limiting tools for under-10 users

- ○

Parental access dashboards to monitor usage

- ○

Content moderation for age-appropriate material

Government and industry partnerships could encourage culturally appropriate adaptations in line with Bangladeshi norms.

7.2.5. Socio-Cultural and Community Interventions

-

Leverage community centers, pediatric clinics, and local NGOs to raise awareness about:

- ○

Screen-time management

- ○

Emotional and behavioral risks of excessive reel exposure

- ○

Best practices for co-viewing and supervision

Community-driven campaigns can reach semi-urban and rural populations, mitigating disparities in digital literacy and supervision.

7.2.6. Longitudinal Monitoring and Research

Establish national surveillance programs tracking digital media exposure and child mental health outcomes.

Encourage longitudinal studies to examine cumulative impacts, resilience factors, and potential recovery trajectories.

Emphasis on mixed-method research combining quantitative, qualitative, and observational data to capture nuanced behavioral patterns.

7.3. Theoretical Implications

The findings have significant implications for theory:

Developmental Cognitive Theory: Confirms that early exposure to high-intensity digital content impacts executive attention, supporting cognitive load and attentional control models.

Social Cognitive Theory: Highlights observational learning in digital environments, with imitation and emotional contagion evident in children’s behaviors.

Attention Economy: Provides empirical evidence that algorithmically curated content can shape early attentional and emotional habits.

Ecological Systems Theory: Demonstrates that family microsystems and socio-cultural microsystems play moderating roles, emphasizing contextualized interventions.

7.4. Practical and Policy Significance for Bangladesh

Given the rapid digitalization of Bangladesh, particularly among urban and semi-urban households, the findings are policy-relevant and timely:

Urban households with high device access and limited parental supervision are particularly at risk.

Policy interventions focusing on early childhood can prevent long-term attention, emotional, and behavioral deficits.

Digital literacy campaigns can equip parents to mediate effectively, aligning with UNESCO’s Global Media and Information Literacy recommendations.

Implementing these recommendations can ensure that children benefit from educational and recreational digital content while minimizing mental health risks.

7.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its contributions, the study has limitations:

Cross-sectional design: Cannot establish causality; longitudinal studies are recommended.

Parent-report bias: Reliance on proxy measures may underestimate or overestimate actual exposure and outcomes.

Urban-focused sampling: Rural populations may exhibit different exposure patterns and outcomes.

Content specificity: Future research should analyze effects of specific content genres, e.g., educational vs. entertainment reels.

Future studies could explore interventions integrating parental mediation, school curricula, and platform-level controls, measuring long-term developmental outcomes and resilience factors.

7.6. Concluding Statement

In conclusion, the study provides robust evidence that social media reel exposure negatively affects cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and dependency-related outcomes among Bangladeshi children under 10, while highlighting parental mediation and socio-cultural context as critical protective factors. The findings inform theory, practice, and policy, emphasizing the need for age-appropriate digital guidelines, parental education, school-based interventions, platform accountability, and community awareness campaigns.

As Bangladesh continues its digital transformation, these insights can guide evidence-based strategies to safeguard early childhood mental health, ensuring that digital innovation benefits, rather than harms, young learners.