In the global discussion on sustainable resource management, be it in the context of biodiversity or the climate crisis, thermodynamics plays almost no role, and even less so nonequilibrium thermodynamics. While the latter thermodynamics and “entropy” are only very rarely explained and mentioned in books and papers on environmental topics, e.g., in the book “A New Ecology Systems Perspective” (Nielsen and Plath 2020), which highlights the principles of ecosystem development and functioning, they are not yet used to assess the sustainability of certain technological ecosystem management or climate protection measures.

In the essay “Zufall und Komplexität sind Geschwister” (“Chance and complexity are siblings”, Weßling 2023), the author proposed for the first time entropy as a criterion for sustainability. In a following article (Weßling 2024), several further steps to apply entropy as a sustainability criterion in (semi)quantitative form are presented. This criterion was extensively described and derived from basic nonequilibrium thermodynamic principles in the author’s book (Weßling 2025). Here, a compact description of the entropy sustainability criterion will be presented. After some key principles of nonequilibrium thermodynamics are reviewed, we will develop some first steps toward a quantitative analysis of the energy demand and entropy production of the DAC, CCS (“Direct Air Capture, Carbon[dioxide] Capture & Storage”) and CCU (“Carbon[dioxide] Capture & Use”) processes. As will be shown, this makes it possible to determine whether such processes are sustainable. Entropy can thus be introduced into the discussion as a general criterion for sustainability. Finally, “MIPS” (material intensity per service unit), an indicator that was introduced several years ago but has since been forgotten, is presented as a simpler approach to this issue.

Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics and Dissipative Structures

Nonequilibrium thermodynamics was fundamentally developed by Ilya Prigogine, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1977 (Nobel Prize Committee 1977). He described self-organization into complex structures for the first time and called them “dissipative structures”. “Dissipative” because open systems are far from equilibrium owing to a supercritical energy input and cannot compensate (“dissipate”) the energy flow in any other way than by forming complex structures, which is associated with a strong entropy export to the environment outside the open system. Entropy exported to the outside of an open system means a reduction in entropy within this system, which is equivalent to an increase in the degree of complexity.

This is particularly easy to visualize when looking at Bénard cells. These are formed as soon as a glass dish filled with oil (containing fine metal filings for better visibility) is heated from below, and the heat supply is slowly increased. If a characteristic heat input is exceeded, 5- and 6-cornered cells suddenly form because the oil cannot dissipate the supercritical heat in any other way: the cells roll synchronously, effectively dissipating the excess heat.

Prigogine has also investigated cyclic reactions, including the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction. This reaction repeatedly forms ever changing complex patterns that look different in detail each time.

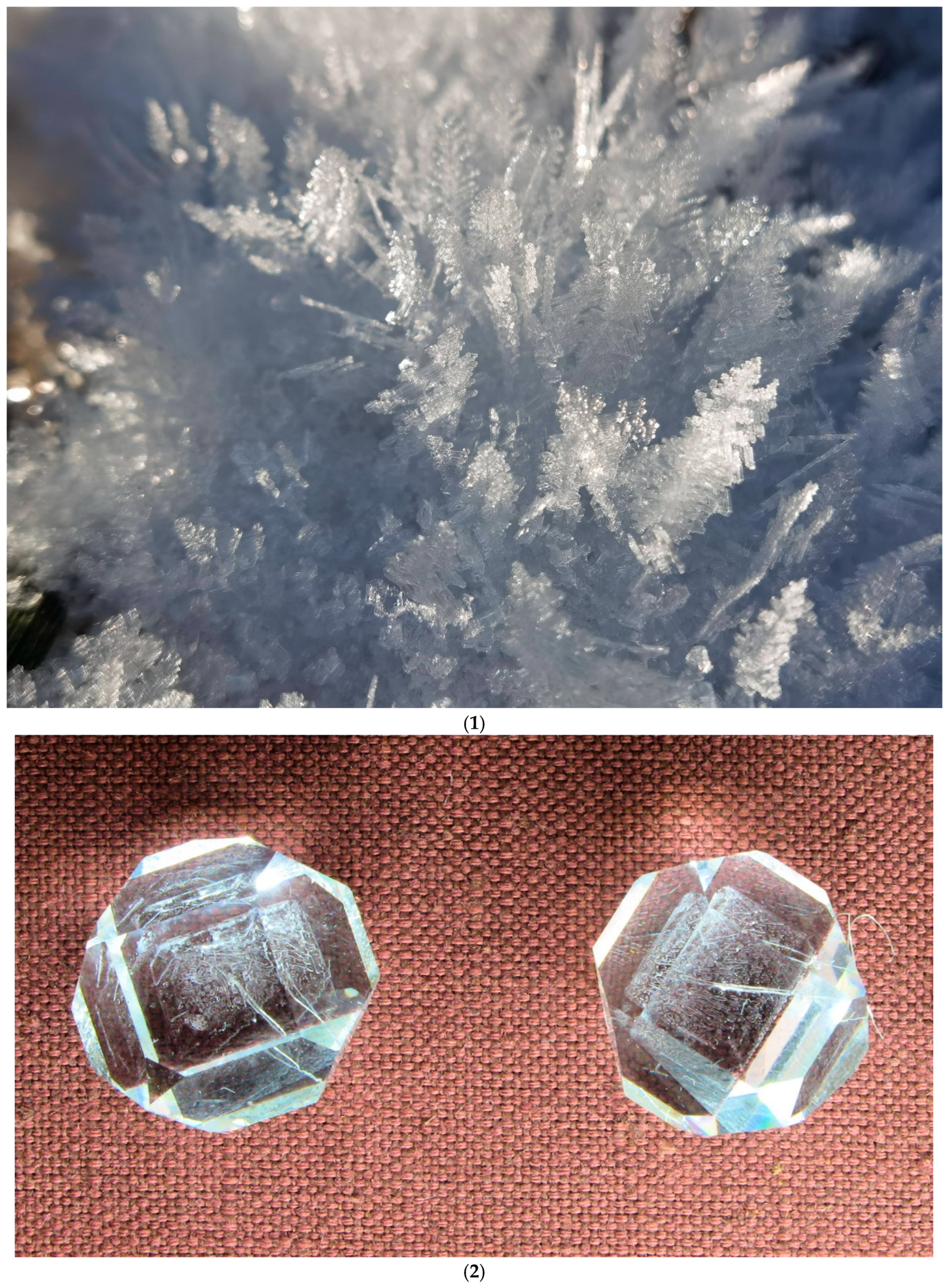

The differences between complex ice crystals and regularly grown single crystals (

Figure 1) also demonstrate the differences between the nonequilibrium dissipative structures and other structures formed at thermodynamic equilibrium:

With their regularity, single crystals are particularly “simple” (because they are symmetrical) and therefore have a maximum entropy. It is a mistake to believe that entropy is only a sign of “disorder” (cf. also Dyer 2019); rather, it is a sign of “simplicity”—in other words, a system in which the different volume elements are not distinguishable at all or almost indistinguishable but all look practically (or even in detail) identical, contains or represents a maximum of entropy. Like the elementary cells of a crystal, which can be found exactly the same everywhere in a single crystal (

Figure 1(2)), or like the distribution of dissolved sugar molecules in water, the same number of sugar molecules will be found in every volume element (if the solution is perfect), and their arrangement cannot be distinguished from one volume element to the next and to the third. These are equilibrium systems.

It is quite different in a complex system, such as the ice crystals in

Figure 1(1) or snowflakes: every volume element in

Figure 1(1), every snowflake falling from the clouds looks different (there are no 2 truly identical snowflakes, as explained in the author’s book (Wessling 2023)). Both types of crystals, such as those in

Figure 1(1) or snowflakes, are formed in nonequilibrium systems, where complex structures arise.

According to Prigogine, this is because a supercritical energy input forces an open system into a state far from equilibrium, and entropy is exported. This crucial point fundamentally expands the conventional understanding on the basis of classical equilibrium thermodynamics:

While entropy is constantly increasing in closed systems and on the scale of the entire universe, and entropy will only increase (2nd law of thermodynamics), this is not (necessarily) the case in an open system far from equilibrium. Entropy can be exported from these systems, i.e., it is decreasing insides such systems, and according to Boltzmann’s statistical interpretation, a higher degree of complexity is identical to a lower entropy content. The more complex the order is, the lower the entropy: a regular crystal has a higher entropy than an oak crown; there, the branches of two oaks are each in different volume segments, and the system elements (here, the cells that form branches and bark) are in different volume elements than those of another oak, even if they are genetically identical, have the same age and grow next to each other.

The reason for this Is that In all such nonequilibrium systems, processes that need to be described with nonlinear equations take place, and these processes also interact with each other, which leads to the entire system behaving in an extremely nonlinear way. In other words, in principle, it is not possible to predict how nonlinear processes, which still influence each other, ultimately behave. As a result, over time, while a supercritical amount of energy (and eventually matter) flows into the open system, “bifurcations” (as Prigogine called them) occur again and again: the system can suddenly and unpredictably take a different course.

In an equilibrium system, the (free) energy tends toward a minimum, and the corresponding processes occur spontaneously, are reversible, and the entropy reaches a maximum. Nonequilibrium systems are completely different: the energy influx can be more or less continuous, and the entropy can reach steadily lower values. However, the process flow is nonlinear, and relatively stable states of complex structures can be reached after a few bifurcation events. As soon as the supercritical energy flow ceases, the complex structures are subject to decay: the entropy increases.

Figure 3.

In equilibrium systems that have no energy or mass exchange with the environment, the free energy falls to a minimum (

Figure 3(1)) and the entropy accordingly to a maximum; in nonequilibrium systems that are far from equilibrium, which exist only as open systems with energy and mass exchange with the surrounding systems, the behavior is diametrically opposed (

Figure 3(2)). In these systems, the free energy increases, and the entropy decreases accordingly until adequate dissipative structures are formed in each case.

Figure 3.

In equilibrium systems that have no energy or mass exchange with the environment, the free energy falls to a minimum (

Figure 3(1)) and the entropy accordingly to a maximum; in nonequilibrium systems that are far from equilibrium, which exist only as open systems with energy and mass exchange with the surrounding systems, the behavior is diametrically opposed (

Figure 3(2)). In these systems, the free energy increases, and the entropy decreases accordingly until adequate dissipative structures are formed in each case.

We know this about life. However, it is often overlooked that “life” (e.g., organisms and ecosystems) and also inanimate dynamic systems such as rivers, weather or galaxies cannot be described by equilibrium thermodynamics but can be described only by nonequilibrium thermodynamics: entropy is constantly exported from open dynamic systems (ultimately into the universe, presumably into black holes); the processes behave nonlinearly, and they also interact nonlinearly with each other. Nonequilibrium is what keeps us alive, “equilibrium is decay and death” (quote from Ludwig von Bertalanffy 1968: “Biologically speaking, life is not the maintenance or restoration of equilibrium, but essentially the maintenance of imbalances, as the doctrine of the organism as an open system shows. Reaching equilibrium means death and consequent decay”. Bertalanffy is the creator of the term “steady state”, which is not an equilibrium at all but a nonequilibrium system, as he himself wrote.

Is That Relevant for Us? Yes, Not Only but Also as a Criterion for Sustainability

Some readers may think that these are rather theoretical and abstract considerations and that “entropy is at best interesting for an academic audience” (which is an occasional statement in discussions). This must be firmly contradicted. Prigogine’s thermodynamics is another pillar for understanding our world (cf. the Nobel Prize Committee’s justification for granting the prize to Prigogine 1977), which is on the basis of the theory of relativity, quantum physics or the theory of evolution. However, it is not perceived as such, and it is hardly taught at universities; in thermodynamics textbooks, Prigogine’s theory is only dealt with very briefly on barely more than 20 pages, whereas conventional equilibrium thermodynamics take up more than 900 pages. This is because, in reality, in the world around us and in industry, apart from very few real systems such as, e.g., sugar water or alcohol diluted with water, there are hardly any equilibrium systems or processes. The vast majority of industrial chemical processes are nonequilibrium processes; the vast majority of systems in the environment in which we live are nonequilibrium systems: weather, climate, life, ecosystems, economy, etc. (cf. Ebeling and Feistel, 2011).

In contrast to the other three fundamentally important theories, nonequilibrium thermodynamics are not a topic in high school at all. While if one wants to learn some introductory basics about relativity theory, quantum physics or evolution, one can find a sufficient number of popular science books and articles for different levels of education, but if one were to look for easy-to-understand books or articles on nonequilibrium thermodynamics or entropy, you would almost completely fail (except for the author’s book “What a Coincidence”, Wessling 2023).

Our linguistic images have not evolved accordingly: we are constantly complaining that something is “out of balance, out of equilibrium” (and wishing that it could be brought back into balance, as if it had ever been): ecosystems, the climate, currency exchange rates, the economy and the financial system in general. The German Constitution in Art. 109 (2) demands that “the requirements of macroeconomic equilibrium” are to be taken into account. Strangely, however, so-called “equilibrium” is only maintained if the economy is growing; even in the case of stagnation, i.e., zero growth, the equilibrium requirement is no longer considered to be met. However, in reality, the economy is a complex nonequilibrium system and has never been in equilibrium (if it were in equilibrium, nothing would happen: energy at minimum, entropy at maximum).

Figure 4.

Global energy budget: Reflected solar irradiation does not contribute to the energy influx, which is approximately 235 W/m2; the equivalent amount is exported as entropy in the form of longwave infrared radiation (Kiehl, Trenberth 1997).

Figure 4.

Global energy budget: Reflected solar irradiation does not contribute to the energy influx, which is approximately 235 W/m2; the equivalent amount is exported as entropy in the form of longwave infrared radiation (Kiehl, Trenberth 1997).

The fact that the world only exists and that we can live therein is because, fortunately, everything is NOT in equilibrium but moves in more or less stable dynamic processes far from equilibrium, is largely unknown. The significance and role of entropy are also largely not understood.

In the current climate debate, there are an increasing number of publications in various media about processes with which CO2 can be removed from the atmosphere and either stored in deep layers of the Earth or utilized in chemical processes (Zhao 2023 and Wikipedia). Investors and politicians are taking a serious look at this, one glaring example being “e-fuels” (synthetic fuels produced from water and CO2 via electrochemical processes, cf. “eFuel-Today” 2024).

Figure 5.

The CCS plant “Mammoth” of the company Climeworks, which has been under construction in Iceland since 2022; it has a capacity of 36,000 tonnes of CO2 per year (© Climeworks 2022). It started its operation at a reduced capacity in 2024; thus far, it has failed the predicted goals by at least one order of magnitude (Alexandersson 2025) and has a 2 to 3 times higher energy demand than previously announced.

Figure 5.

The CCS plant “Mammoth” of the company Climeworks, which has been under construction in Iceland since 2022; it has a capacity of 36,000 tonnes of CO2 per year (© Climeworks 2022). It started its operation at a reduced capacity in 2024; thus far, it has failed the predicted goals by at least one order of magnitude (Alexandersson 2025) and has a 2 to 3 times higher energy demand than previously announced.

The various technological experiments are by no means reported about uncritically, but the discussion is limited to risks (Lane 2021) and costs. Energy requirements are often mentioned without comment, if at all; thermodynamics and entropy in particular are not considered, neither by journalists nor by the operative companies, investors and politicians who decide on the climate protection measures to be taken. Whenever it is mentioned that the energy requirement for DAC, CCS or CCU is considerable (albeit without comparing it with the energy requirement or energy content of alternative processes or materials), the authors put readers off by pointing out that “renewable energies” (like Climeworks is using geothermal energy in Iceland) would be provided for this purpose: However, neither do we have an infinite amount of it, nor can we harvest it for free (but need raw materials, space, water ..., and euros or dollars), and this energy conversion also generates a lot of entropy.

Initial Assessment: Sustainability of Final CO2 Storage?

In the following, we first examine whether the capture of CO2 from the air and its final underground storage of CO2 are sustainable. We will also look at proposals for the utilization of CO2, i.e., the chemical conversion of CO2 into useful raw materials. It is widely publicized that final storage and chemical use of CO2, together with the avoidance of CO2 emissions, is a sufficient panacea for climate change in parallel with CO2 emission reduction. This is a mistake in itself because CO2 is a very important contribution to, but not a monocausal reason for climate change, and one must not forget that climate is a result of extremely complex nonlinear processes with unnumerous nonlinear interactions (Dethloff 2024). And the public, including large sections of the scientific community, overlooks the fact that climate change is not the only environmental crisis we are experiencing, but that the decline in biodiversity is at least as great an existential problem. An analysis of sustainability must therefore take into account effects on the climate as well as on biodiversity and the environment as a whole. The entropy can serve as a tool for judging sustainability in general terms without the need to specify or differentiate which effect in detail will be observed—entropy will tell us about the total loss of valuable energy, matter and complexity.

Energy Estimation of Final Disposal

We compare the enthalpy of formation of CO2 with the energy required to capture the gas and store it in deeper layers of the earth as CaCO3: 1 tonne of CO2 contains 22,727 moles of CO2, which corresponds to -8.9*106 kJ enthalpy of formation (molar value -393, cf. Sellnacht Lexicon), of which we were able to use less than a third (i.e., approximately 2.5*106 kJ) as available electrical energy when forming it in a power plant, with the remainder being waste heat, solid waste and entropy.

M. Fasahi et al. published a technoeconomic assessment of direct air capture systems (Fasihi 2019). As shown in Table 1, the total heat requirement for CCS is in the range of 1420–2250 kWh (thermal) per tonne of CO2, depending on the degree of heat integration. The required electrical power is 366–764 kWh per tonne of CO2. In the following, 2000 kWhth and 600 kWhel are used as the basis for further considerations. Similar values in the order of magnitude of these values can also be found in various other publications. (However, more recently, Climeworks disclosed that its real energy consumption was 2–3 times higher than estimated and claimed before, cf. Andersson and Grettison 2025.)

The heat required corresponds to 7.2*106 kJ (almost as much as the CO2 formation enthalpy) but is not provided with 100% efficiency; if it can be provided with 80% efficiency, one must start with 9*106 kJ of primary energy, which corresponds to the formation enthalpy. In addition, the electricity required corresponds to 2.16*106 kJ; with a global average efficiency of 31% for coal-fired power plants (EURACTIV), 7*106 kJ of primary energy must be provided, which is also consumed.

A total of 16*106 kJ (16 GJ) is needed, which is almost twice as much as the CO2 formation energy, so the energy requirement is approximately six times as high as the amount of energy that we were able to use during the formation of this 1 tonne of CO2.

The argument that we want to use renewable energy from the hot volcanic depths of Iceland or solar cell power plants in the desert does not hold water, because we could also just generate electricity and use it directly with high efficiency (which is also done in Iceland for aluminum production, for example). It is therefore a waste of energy and, as a result, a massive increase in entropy if we want to operate DAC or CCS plants while we still do not have enough renewable energy and most likely never will have.

Figure 6.

The Nesjavellir power plant near Þingvellir (

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nesjavellir-Kraftwerk) is the largest geothermal power plant in Iceland. It provides 120 MW of electrical energy and 300 MW of thermal energy but has been able to do so for only approximately 30 years since 1990, after which its output has steadily decreased. With this electrical output, only as much CO

2 would theoretically be possible to extract from the air and become stored in the ground as a small 20 MW conventional power plant generates CO

2.

Figure 6.

The Nesjavellir power plant near Þingvellir (

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nesjavellir-Kraftwerk) is the largest geothermal power plant in Iceland. It provides 120 MW of electrical energy and 300 MW of thermal energy but has been able to do so for only approximately 30 years since 1990, after which its output has steadily decreased. With this electrical output, only as much CO

2 would theoretically be possible to extract from the air and become stored in the ground as a small 20 MW conventional power plant generates CO

2.

Entropy Balance of Final Disposal

For the entropy analysis, we first consider the entropy of the atmosphere, which contains approximately 0.06% (by weight) CO2. Since we refer above to 1 tonne of CO2, we have to consider a mixture of CO2 with approximately 1,670 tonnes of other components of the air (nitrogen and oxygen and other components such as water, trace gases, etc.) (all of which a DAC plant pushes through the filter systems to capture 1 tonne of CO2).

The entropy S of air containing CO

2 is calculated approximately according to the formula for “mixing entropy” (or dilution entropy) (simplified for ideal gases and closed systems, which is approximately sufficient for our purposes; cf. Hägele 2005):

We have approximately 22,727 moles of CO2 (= 1 tonne) in the air, mixed with approximately 38*106 moles of other air components, if they would have the same molecular weight as CO2. However, the mixture of nitrogen and oxygen has a lower molecular weight, so we have approximately 38*106*1,5 = 57*106 moles of other air components in 100 wt% air (which contains 1 tonne of CO2).

One mole contains approximately 6*1023 molecules (this is the definition of “mole”). If we insert these values (with the Boltzmann constant k=1.3*10-23) into the above formula, we obtain an entropy value of 1,47 MJ/K.

Since we want to filter 1 tonne of CO2 out of the air, which has this extremely high entropy value, we have to reduce the entropy of the atmosphere by 1.47 MJ/K (albeit at ambient temperature, i.e., approximately 293 K), because if we obtain pure CO2 outside the atmosphere, its entropy of mixing is zero. (The mixing entropy of the other atmospheric components remains unchanged.) We have to add a further entropy contribution (by which the mixing entropy of the atmosphere will be reduced) because 2 to 5 molecules of water are adsorbed for every molecule of CO2 as well. If we take 2 molecules, we need to add 2.68 MJ/K so that the atmosphere will be reduced by 4.15 MJ/K for each tonne of CO2. This is the entropy equivalent of climate stabilization for any CO2 that contributes to climate change, i.e., the positive effect of the DAC.

As nonequilibrium thermodynamics show, an entropy decrease in an open system (here, atmosphere) can be achieved only if supercritically much energy is invested (we have already seen how much energy is needed: it is extremely much). The decrease in entropy (i.e., the export of entropy) causes (due to the 2nd law of thermodynamics) a significantly stronger increase in entropy outside the atmosphere and outside of any DAC or CCS plant. The entropy increase is associated mainly with the conversion and provision of process energy and the installation/operation of the necessary infrastructure (not considering anything that is necessary for building and maintaining the necessary infrastructure or for compressing and final storage of CO2).

The above results show that at least 16 GJ are needed to capture 1 tonne of CO2. Consequently, the entropy production for this is in the GJ range, i.e., at least a factor of 1,000 greater than the entropy reduction in the atmosphere, which is in the MJ range.

The argument that renewable energy conversion should be used for CCS does not change this. The answer to the question of whether we actually have a surplus of energy from renewable sources (wind and solar) that could allow us to utilize it wastefully is clear: “We do not have this surplus.

However, we should also take entropy into account: the statistical interpretation of entropy is well known; in a system where entropy increases, complexity also decreases.

We cause a drastic global entropy increase on the Earth’s surface by reducing the entropy of the atmosphere, for which a large amount of process energy is needed. Therefore, as the entropy increases, the complexity decreases somewhere else on Earth. We can notice this where we extract the raw materials for the production of the devices (with the help of which we provide the energy) and where we process them into the devices: silicon, etc., for solar cells with the entire electrical, electronic and mechanical fine structure; copper mining for cables; lithium mining for batteries; water (large quantities of industrial water for final storage); cement and glass fiber-reinforced polymers for wind power; power grids; and so on. All this requires land that is no longer available for biodiversity (natural complexity). The deterioration of biodiversity is an indicator of an increase in entropy, which is identical to damage to the environment.

Another aspect must also be taken into account, namely, the scale we have to address. Niall Mac Dowell et al. analyzed “the role of CO2 capture and use in mitigating climate change” (MacDowell 2017). Using the volume of CO2 that would have to be injected into deep underground storage facilities, they reported that these would have to amount to 1,033 million barrels of CO2 per day if only the global daily CO2 emissions had to be captured. Current global oil production is 87–91 million barrels per day. Then, they write: “This means that global CO2 production [in terms of volume] is about a factor of 10 bigger than global oil production today and could even be a factor of 20 bigger by 2050 at current growth rates.” This would mean, they continue saying, that by 2050 [i.e., within just 25 years from now], an industry “much larger than the global oil industry” would have to be built up, whereas the size of today’s global oil industry was built within an entire century. Even if it was conceivable to build up such a gigantic industry so quickly from next year onward, where would the raw materials for it come from, where would these enormous factories be located, where would the CO2 finally be stored, how many additional liquefaction plants would have to be built to ship the CO2 emitted in Germany alone to Norway and Denmark for final storage under the seabed, where would the gigantic amount of energy required for this come from? This infrastructure would already be needed for the actual CO2 emissions. Additional CO2 concentration reduction could still not be achieved, hence we would still be far away from reducing the CO2 concentration.

Figure 7.

Open-cast mining leads to the destruction of landscapes/ecosystems and to the extensive lowering of groundwater levels with far-reaching damage to the environment. Mining of copper in the Escondida copper mine in Chile (NASA image of the Escondida Mine in Chile, taken by en:ASTER on April 23, 2000).

Figure 7.

Open-cast mining leads to the destruction of landscapes/ecosystems and to the extensive lowering of groundwater levels with far-reaching damage to the environment. Mining of copper in the Escondida copper mine in Chile (NASA image of the Escondida Mine in Chile, taken by en:ASTER on April 23, 2000).

A “prudent” estimation of the geologic carbon storage potential shows that it is much more limited than generally assumed and would at best help reduce warming by 0.7 °C if fully used (Gidden et al. 2025). The analysis shows that thousands of DAC plants and an additional, as yet unquantifiable number of kilometers of CO2 pipelines would have to be built—a manifestation of entropy.

The enormous increase in entropy production indicates that the collateral damage of DAC and CCS processes will be many times greater than the hoped-for positive effect on the climate.

Converting CO2 Into Useful Raw Materials?

A number of processes are actually being researched or developed and tested (and numerously publicized), at least on a laboratory scale and, in some cases, already on a pilot scale, which converts CO2 into raw materials that are currently used in industry on a significant scale (Frick 2023).

CO2, which is very inert, is supposed to serve as a valuable raw material in this way; the economy is then supposed to become “sustainable” because “CO2-neutral”. But is “climate-neutal” simply the same as “sustainable”? Can such a promise of sustainability actually be realized? The drastically unfavorable energy and unsustainable entropy balance of removing CO2 from the atmosphere has already been shown in the previous sections. This means that the first step, the provision of CO2 for chemical processes, has already been recognized as unsustainable. In fact, further chemical conversion can not contribute at all to improving the negative sustainability balance.

This also seems to be the view of Covestra AG (formerly a part of Bayer AG), which has discontinued polyol production using CO2 as a raw material not only for economic reasons but also due to a lack of sustainability (which Covestra did not explain in detail, Frick 2023). Sustainability requires not only “customers who accept a surcharge in order to score points in the area of sustainability” (which Frick 2023 obviously declares to be a criterion for sustainability). This is because sustainability does not result from poorer economic efficiency (which could be compensated for with higher prices if they are accepted) but only from minimal entropy production.

We should therefore take a closer look at whether the chemical utilization of CO2 can be sustainable by means of subsequent chemical processes. We do not consider the individual reactions/processes described in the abovementioned article or many original research papers reporting diverse chemically feasible reactions but rather consider a very simple model reaction, as presented by Prof. Benjamin List (Nobel Prize winner 2021 for his work in the field of organic catalysis) in the ZEIT magazine of 11 May 2023 in the form of a question and some explanations. The magazine asked 12 renowned scientists about the “big unsolved questions in their field to which they would like to have an answer”. Prof. List asked: “Can we stop climate change by splitting carbon dioxide into its components?” and then burying the carbon again as coal, for example, in the Ruhr region, as he suggested, where in former decades, much coal had been mined.

If we want to split CO2 back into C and O2, we have to use at least the 393 kJ/mol enthalpy of formation that was released during the reaction of C and O2 to form CO2 in the combustion process. “At least” because the process of renewed fission also entails a loss of efficiency (i.e., further entropy generation). However, owing to the typical efficiency of power plants, only approximately one-third of the formation enthalpy, approximately 130 kJ/mol, of the energy was available for our use when we produced CO2!

Even catalysis (Prof. List’s speciality) cannot change this to the better because a suitable catalyst cannot change the reaction enthalpy but can only reduce the activation energy and increase the reaction rate.

In addition to the aspect of the miserable energy balance, there is also the aspect of entropy: this can be estimated by comparing the standard entropy values of the substances involved:C: 6 J/K*mol, O2: 205 J/K*mol; CO2 214 J/K*mol; i.e., we reduce the entropy from 214 to 211 J/K*mol (which appears as an entropy increase outside this system); this does not sound particularly dramatic, but it adds up to the entropy increase required to provide CO2 for splitting into C and O2. In addition, per tonne of CO2, these are already considerable amounts, namely, almost 70,000 J/K, and we are not dealing with one tonne of CO2 but with billions and billions of tonnes and that at approximately 293 K (ambient temperature).

If CO2 is to be chemically reduced by means of H2, as is necessary for the direct chemical utilization of carbon dioxide, the energy requirement, the efficiency and the associated entropy increase of hydrogen production must be added to the energy requirement for the provision of CO2 . It does not become more sustainable, but only more environmentally damaging, becoming even more absurd from an ecological point of view. We cannot ignore the fact that CO2 is an indicator of a large increase in entropy, and entropy can be reduced in CO2 only if entropy increases excessively outside the open system (in which we want to lower entropy). Hydrogen is not available for free, neither in terms of energy nor entropy: to produce 1 tonne of hydrogen, 40,000 to 80,000 kWh of electricity are needed (Heni, scinexx 2024). However, according to this source, wind power is found worldwide mostly where water of drinking water quality (as required for the electrolysis of water) is rather rare, often (like in desert areas), not even seawater. For solar energy used in PV plants, the same applies: no clean water is available. Therefore, desalination of seawater is necessary, which not only requires additional electricity but also causes massive damage to coastal marine ecosystems: desalination produces toxic brine, which is also contaminated by the chemicals required in the process. In addition, an unnumerable number of pipelines need to be built to bring clean water to wind or PV power plants.

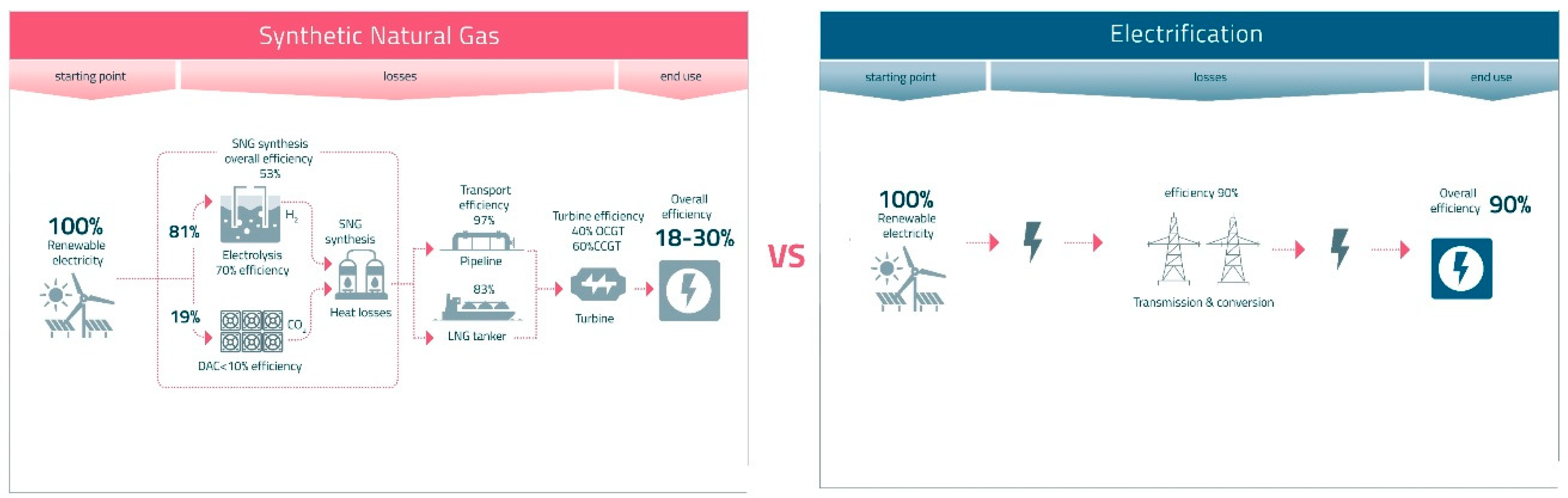

It is often referred to as “green hydrogen” if it is produced from renewable energy sources. However, the direct use of electricity from these sources (e.g., to power electric cars) is much more sustainable than the use of electricity for the electrolysis of water into hydrogen, the subsequent conversion of CO

2 into “e-fuels” and its use to power cars with internal combustion engines. In all steps, a drastic loss of efficiency in energy utilization must be taken into account, which corresponds to entropy production. This can be seen from the fact that the energy amount required to produce e-fuel for driving 100 km, for example, is approximately a factor of 10 (!) more than if the electricity from wind power (or the PV system) was used directly in the electric car (Tine Heni 2024, where a comparison is made with a diesel engine, which requires approximately 50% more energy than a comparable electric car). Similarly, this applies to any chemical that is produced from CO

2 via so-called “green” hydrogen (cf.

Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The graph on the right side shows the efficiency loss for the supply of electricity for direct use, e.g., in an electric car (10% loss), compared with that for synthetic methane, the graph on the left side (70–82% loss). (The author thanks the Future Cleantech Architects Thinktank, Remscheid, Germany, for providing this graph and allowing its use.).

Figure 8.

The graph on the right side shows the efficiency loss for the supply of electricity for direct use, e.g., in an electric car (10% loss), compared with that for synthetic methane, the graph on the left side (70–82% loss). (The author thanks the Future Cleantech Architects Thinktank, Remscheid, Germany, for providing this graph and allowing its use.).

A meta-study on the environmental aspects of CO2-based chemical production (Thonemann 2020) concluded that “there is no CO2-based chemical production technology that performs better in every IC [impact category] than the conventional production alternative”. This should come as no surprise to anyone looking at the entropy balance, as entropy is an indicator of negative environmental impacts.

While Mac Dowell et al. (2017) have shown that even if it were theoretically possible to somehow replace all organic feedstocks in the chemical industry with CO2-based chemicals (produced via CCU), the amount of feedstock required “highlights how negligible the contribution of CCU to the global CO2 mitigation challenge will be”: only 10% of the global annual CO2 emissions could be used for this CCU channel. Kätelhön et al. (2019) also conclude how absurd such an approach would be: “Exploiting this potential, however, requires more than 18.1 PWh of low-carbon electricity, corresponding to 55% of the projected global electricity production in 2030.” In other words, to eliminate (only theoretically) at best 10% of global annual CO2 emissions, the chemical industry would need 55% of the total global electricity generation (as forecast for 2030), not only electricity from renewables. In other words, this is nothing other than a manifestation of entropy.

This electricity requirement does not yet take into account the fact that CCS and DAC would require large proportions of the global electricity generation. With current annual CO2 emissions of approximately 36 gigatonnes, approximately 22 PWh of electrical energy (and 72 PWh of thermal energy) are needed to stabilize the CO2 concentration at the current level. This means that 2/3 of the total electricity generation of approx. 33 PWh forecast for 2030 would be required for CCS and DAC. Mind you: the total electricity demand, not just that from renewable energy sources. Which electricity would then be used to power the global infrastructure and industry? There would only be 9 PWh of conventional electricity left together with renewable generation for what today (2023) requires just under 30 PWh.

The 2nd law of thermodynamics, which states that entropy increases continuously, cannot be overridden. Nor can we get around the fact that if we want to reduce entropy in a particular open system (e.g., the atmosphere) or use materials with a high entropy content (e.g., CO2) and thus in turn reduce entropy, we have to invest an enormous amount of energy, which leads to several orders of magnitude higher entropy production on a global scale. The laws of nature cannot be overcome by ignoring them.

Conclusions

All this is not taken into account at all in the public debate, not even in science. The mixing entropy alone (which we have to export “into the environment” when separating the gases from the treated air, i.e., when separating the CO2 from the other components of the air, because CO2-poorer air contains less entropy) is enormous. In addition, much more entropy is generated during the provision of the required energy. This may seem very theoretical to some, but it is not as can be seen how entropy manifests itself: impoverished ecosystems; landscapes hostile to life; arable land practically lifeless due to pesticides and insecticides with, if at all, only one centimeter of humus; waste heat; mountains of waste; drinking water consumption (in hydrogen production); or polluted waters and seas. The damage to marine ecosystems caused by seawater desalination, microplastics, and a decline in biodiversity (birds, insects, etc.) and many more are signs of entropy-related environmental damage. Neither in terms of energy nor in terms of entropy is the disposal (final storage) or utilization of CO2 sustainable.

The climate and biodiversity problems can only be solved together. It cannot be expected that an article such as this can present a complete concept for solving this complex global problem. However, there will be no solution without the crucial contribution of photosynthesis: in ecosystems that are as close to nature as possible, as wild as possible (or renaturalized), with organic farming practised worldwide (Schmitz 2023, Buck-Wiese 2022, Wessling preprint 2025), the last one quantitatively shows how much organic bioagriculture can be delivered in terms of carbon capture and storage parallel to biodiversity recovery, as byproducts of the production of healthy and tasty food. Technology can help us with efficient industrial processes but not with CO2 capture and final storage. The chemical conversion of CO2 into useful substances should be left to plants, fungi and microbes.

Mixed forests (Lidong Mo et al., 2023) and fungal networks (Heidi-Jayne Hawkins et al. 2023) offer a capacity for CO2 fixation that has thus far been underestimated by orders of magnitude, but this requires allowing natural processes to occur in tranquility, space and time. Peatlands can store twice as much CO2 as all of the world’s forests combined (Temmink 2022)—although they only require a fraction of the area—and would “only” need to be rewetted; in addition, there is the storage potential of other wetlands and coastal seagrass meadows and kelp forests. The solution to our acute environmental problems, namely, the biodiversity crisis, lies in the combination of these natural processes. In the public debate and in science, it is often assumed that forests—and preferably even with fast-growing trees—have the best CO2 storage potential. This is a misconception that we cannot analyze in detail in this article. However, the fact that monocultures contribute nothing to solving the biodiversity crisis is directly understandable.

Figure 9.

Even-aged monoculture forests are neither efficient CO2 sinks nor do they contribute to increasing biodiversity. (Photo: wikimedia commons).

Figure 9.

Even-aged monoculture forests are neither efficient CO2 sinks nor do they contribute to increasing biodiversity. (Photo: wikimedia commons).

Compared with even-aged, single-species forests, mixed forests managed as permanent (continuous cover) forests (Puettmann 2015) and used for construction purposes (Churkina 2020) offer a powerful and sustainable CO2 sink and biodiversity source.

Figure 10.

A naturally developing mixed forest is a powerful carbon sink (not least because of the underground fungal network), especially if there are clearings that are grazed by ruminants, not to mention its contributions to biodiversity, water balance and air quality. (Photo: Commons Wikipedia).

Figure 10.

A naturally developing mixed forest is a powerful carbon sink (not least because of the underground fungal network), especially if there are clearings that are grazed by ruminants, not to mention its contributions to biodiversity, water balance and air quality. (Photo: Commons Wikipedia).

Figure 11.

Peatlands have an even greater capacity as carbon sinks, whereas drained peatlands emit CO2 on a large scale. Like all other wetlands, they are essential for biodiversity, not least because of their monotonous internal structures and complex natural environment. (Photo: Creative Commons License).

Figure 11.

Peatlands have an even greater capacity as carbon sinks, whereas drained peatlands emit CO2 on a large scale. Like all other wetlands, they are essential for biodiversity, not least because of their monotonous internal structures and complex natural environment. (Photo: Creative Commons License).

When other authors have discussed sustainability and tried to approach quantitative criteria, this has usually been limited to “1) exergy balance 2) the ratio or share of renewable energies, expressed as exergies 3) structural costs in the form of exergy” (Nielsen 2020, p. 234; “exergy” is understood as “energy usable for the performance of work”). Entropy has not yet been taken into account. However, this is unavoidable, as even, e.g., renewable energy is not available without having generated much entropy as well.

Ultimately, entropy alone could be seen as the key criterion for sustainability. Together with natural producers, all human processes should not generate more entropy in total than the Earth can radiate (approximately 230 W/m2 of the Earth’s surface, Ebeling/Feistel 2017). We are a long way from this, which means that we generate much more entropy than the Earth can radiate; consequently, entropy accumulates on Earth—where else could it end up? Therefore, we can only move toward a much more sustainable level of living and managing our economy, our agriculture and our ecosystems if we start to introduce entropy generation analysis for our industrial products and processes, including agricultural practices. This must also be done for measures to mitigate climate change and solve the biodiversity crisis.

References

- Andersson, Bjartmar O., Gettison, Valur, “Climeworks’ capture fails to cover its own emissions”. https://heimildin.is/grein/24581/.

- Bertalanffy, Ludwig von, in: “General Systems Theory”, edited by George Braziller, N. Y. 1968, p. 191. [CrossRef]

- Federal Agency for Nature Conservation: Climate protection—peatlands as carbon sinks and GHG sources. https://www.bfn.de/oekosystemleistungen-0#anchor-3817.

- Buck-Wiese, Hagen; Andskog, Mona; Ngyen, Ngyen; Hehemann, Jan-Hendrik; “Fucoid brown algae inject fucoidan carbon into the ocean”, PNAS 120 (1) e2210561119 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Churkina, G., Organschi, A., Reyer, C.P.O. et al. Buildings as a global carbon sink. Nat Sustain 3, 269–276 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Dethloff, Klaus, “Klimaturbulenzen” (book, German), SpringerNature . [CrossRef]

- Dyer, Dan, “Entropy as Disorder: History of a Misconception”, Phys. Teach. 57, 454–458 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ebeling, Werner; Feistel, Rainer; “Self-Organization in Nature and Society”, Conference “The Human World: Uncertainty as a Challenge”, Frolov Lectures 2017, retrieved here: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316878591_Selbstorganisation_in_Natur_und_Gesellschaft_und_Strategien_zur_Gestaltung_der_Zukunft, see also Feistel, R., Ebeling, W., “Physik der Selbstorganisation und Evolution”, Wiley-VCH 2011, p. 97/98. [CrossRef]

- eFuel-Today https://efuel-today.com/en/production-process-of-e-fuels/ (20. 1. 2024).

- EURACTIV: https://www.euractiv.com/opinion/analysis-efficiency-of-coal-fired-power-stations-evolution-and-prospects/.

- Fasihi, Mahdi; Efimova, Olga; Breyer, Christian; “Techno-economic assessment of CO2 direct air capture plants”, J. Cleaner Production, 224, pp. 957-980. [CrossRef]

- Frick, Frank, “Today’s culprit, tomorrow’s hero”, (German) Bild der Wissenschaft Spezial: Rohstoffe (Summer 2023), p. 78 ff.

- Gidden, M. J., Joshi, S., Armitage, J. J. et al., “A prudent planetary limit for geologic carbon storage”, nature Vol 645, Sept 4, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hägele, Peter (2005). https://www.uni-ulm.de/fileadmin/website_uni_ulm/archiv/haegele/Vorlesung/Grundlagen_II_05/_entropie-wahrsch.pdf.

- Heidi-Jayne Hawkins et al., “Mycorrhizal mycelium as a global carbon pool”, Current Biology 33, R560-R573, June 2023. [CrossRef]

- Heni, Tine, “The eternal CO2 cycle”, scinexx (23. 2. 2024), (German) https://www.scinexx.de/dossierartikel/der-ewige-co2-kreislauf/.

- Kätelhön, Arne; Mays, Raoul, Deutz, Sarah; Bardow, André; “Climate change mitigation potential of carbon capture and utilization in the chemical industry” PNAS 116 (23) 11187-11194 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Kiehl, J. T., Trenberth, K. E. Earth’s Annual Global Mean Energy Budget, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, February 1997. [CrossRef]

- Lane, Joe; Greig, Chris; Garnett, Andrew, “Uncertain storage prospects create a conundrum for carbon capture and storage ambitions” Nature Climate Change 11, 925-936 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Lidong Mo et al., “Integrated global assessment of the natural forest carbon potential” nature, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mac Dowell, Nigel; Fennell, Paul; Shah, Nilay; Maitland, Geoffry; “The role of CO2 capture and utilization in mitigating climate change” Nature Climate Change 7, 243-249 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Morris, Stephen, 2009 Photos and videos show a typical reaction sequence: https://www.flickr.com/photos/nonlin/3572095252/in/album-72157623568997798/(20. 1. 2024); Reprinted with the kind permission of Stephen Morris (Univ. of Toronto, Canada) and Mike Rogers.

- Nielsen, Soeren Nors, Fath, Brian, et al., A New Ecology Systems Perspective, 2nd edition, Elsevier Amsterdam, 2020.

- Nobel Prize Committee (1977) https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1977/press-release/ (20. 1. 2024) with links to further sources.

- Sellnacht Lexicon https://www.seilnacht.com/Lexikon/dhtabell.htm (20. 1. 2024).

- Schmidt-Bleek, Friedrich: “How much environment do people need? Factor 10—The measure for ecological management”. (German: Wieviel Umwelt braucht der Mensch?) Birkhäuser, 1993; DTV, Munich 1997. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, Oswald et al., “Trophic rewilding can expand natural climate solutions”, Nature Climate Change 13, 324-333 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Temmink, Ralph, et al., “Recovering wetland biogeomorphic feedbacks to restore the world’s biotic carbon hotspots”, Science 2022, Vol 376, Issue 6593. [CrossRef]

- Thonemann, Nils, “Environmental impacts of CO2-based chemical production: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis”, Appl. Energy 263, 114599 (2020). [CrossRef]

- University of Freiburg https://www.experimente.physik.uni-freiburg.de/Thermodynamik/waermeleitungundkonvektion/konvektion/ (20. 1. 2024) ; Reprinted with kind permission of the Faculty of Physics of the University of Freiburg.

- Weßling, Bernhard, “Zufall und Komplexität sind Geschwister”, Naturwiss Rundschau 9-2023, p. 484 ff.

- Weßling, Bernhard, “Entropie als Kriterium für Nachhaltigkeit”, Naturwiss Rundschau 5-2023, p. 228 ff.

- Weßling, Bernhard, “Was für ein Zufall! Zum Ursprung von Unvorhersehbarkeit, Komplexität, Krisen und Zeit”. 2nd (updated and extended) edition of the original 1st edition: “Was für ein Zufall!! Über Unvorhersehbarkeit, Komplexität und das Wesen der Zeit”, SpringerNature 2022, which (together with the English edition: Wessling, Bernhard, “What a Coincidence”, also published by SpringerNature, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-40671-4) was probably the world’s first popular science book to introduce nonequilibrium thermodynamics. [CrossRef]

- Wessling, Bernhard, “Sustainability through Bio-Agriculture: Carbon Dioxide Reduction (CDR) plus Biodiversity Recovery”, preprint 2025 https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202508.0443.

- Zhao, Yong et al., “Conversion of CO2 to multicarbon products in strong acid by controlling the catalyst microenvironment”, Nature Synthesis 2, 403-412 (2023). for a general description see Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbon_capture_and_storage (20. 1. 2024), or https://www.globalccsinstitute.com/ (20. 1. 2024), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbon_capture_and_utilization (20. 1. 2024). [CrossRef]

Short Biography of Authors

Dr. Bernhard Wessling is a chemist, entrepreneur and natural scientist. In a life full of complexity, he switched very early on from natural product chemistry to polymer chemistry, including conductive polymers and colloidal systems, nonequilibrium thermodynamics and turbulence physics. He took entrepreneurial risks very early on, which took him to China for 15 years. In addition, he carried out crane behaviour and cognitive abilities research on his own on a voluntary basis, also internationally, and actively contributed to several species conservation projects, especially to the North American Whooping Crane Recovery Program; since 2009, he has been involved in species conservation and climate stabilization as an investor and managing director of a now large organic farm (450 hectares of leased land, 7 own farm shops, 90 employees). He has published three books on his work: “What a coincidence! On unpredictability, complexity and the nature of time” (basically a popular-science introduction into nonequilibrium thermodynamics, in a narrative style), “The call of the cranes—expeditions into a mystrious world” (a narrative nonfiction book about his research on wild crane behavior (4 different species in Europe Asia and North America) and his contribution to several nature protection and the big and “Mein Sprung ins kalte Wasser—mit offenen Augen und Ohren in China leben und arbeiten“ (only German, about his 15 years work and life in China, an inter-cultural storytelling about his experience in China). In 2025, he has become a member of the Leibniz Society of Sciences, the oldest German Academy of Sciences.

https://www.bernhard-wessling.com

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |