1. Introduction

Educational access in the Philippines has been significantly challenged by geographic, infrastructural, and socio-economic barriers, particularly in remote, Indigenous, and disadvantaged communities. To address these disparities, the Department of Education (DepEd) introduced the Last Mile Schools (LMS) Program in 2019, targeting schools that meet specific criteria signaling severe resource constraints [

1]. LMS schools are defined as those having less than four classrooms, makeshift or nonstandard structures, no electricity, no repairs or new construction in four years, more than one hour of travel from town centers or difficult terrain, multigrade classes, fewer than five teachers, under 100 learners, and over 75% Indigenous Peoples (IP) learners [

1]. As of the latest reports, over 7,000 schools nationwide have been identified as Last Mile Schools [

2,

3]. These schools collectively serve more than 1.6 million learners, with a significant number located in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. Despite progress, many LMS projects remain delayed. For instance, 76 school facilities procured under the LMS Program were found by the Commission on Audit (COA) to be unfinished as of late 2023, with delays reaching up to 555 days [

4,

5]. In Western Visayas, including Iloilo Province, infrastructure deficits persist in remote schools, such as lack of electricity, inadequate toilet facilities, leaky roofs, and makeshift classrooms [

6,

7]. In Iloilo, initiatives such as

Bulig Eskwela sang Probinsya have provided tent-type makeshift classrooms to geographically isolated communities [

3]. While DepEd has allocated special budgets for electrification, classroom construction, teacher deployment, and connectivity, implementation remains uneven [

2]. Mina, Iloilo represents many municipalities with schools facing multiple Last Mile criteria. Examining a Last Mile School in Mina provides an opportunity to explore how infrastructure, human resources, community support, and environmental context interact, and where sustainability-oriented leverage points may generate meaningful improvements. Despite clear LMS criteria and targeted programs, project delays and misallocations hamper timely delivery of benefits. Localized research applying systems thinking and sustainability science in LMS contexts, particularly in Western Visayas, remains limited. Many LMS still lack basic amenities; thus, sustainability in maintenance, operations, and community integration is as critical as infrastructure provision. Equity concerns, especially for Indigenous Peoples, further necessitate context-sensitive studies that examine whether LMS interventions genuinely address learner needs. This study aims to analyze the SDG 4 performance of a Last Mile School (LMS) in Mina, Iloilo, Western Visayas Region and understand how the socio-ecological processes impact learning outcomes. Specifically, this case study aimed:

1. to describe the current conditions of the identified Last Mile School in terms of the means of implementation to achieve SDG 4;

2. to identify the SDG 4 performance in terms of learning outcomes of the identified Last Mile School (LMS);

3. to understand how the current conditions of the identified Last Mile School impact its SDG 4 performance from a socio-ecological systems perspective.

3. Results

Current Conditions of the Identified Last Mile School in Terms of the Means of Implementation to Achieve SDG 4

The Yugot Elementary School (YES- ID 137024) is a Last Mile School (LMS) identified by the Department of Education VI. It is a public basic education institution located in one of the remote barangays of the Municipality of Mina, Iloilo, in the Western Visayas Region of the Philippines. The school is officially classified by the Department of Education (DepEd) as a Last Mile School (LMS) based on multiple indicators of geographic isolation and resource deprivation. According to DepEd’s LMS criteria, these schools typically have fewer than four classrooms, makeshift or nonstandard school buildings, lack of electricity, absence of repairs or construction within the last four years, travel time of more than one hour from the town center or access through difficult terrain, multigrade classes, fewer than five teachers, fewer than 100 enrolled learners, and more than 75% Indigenous Peoples (IP) learners. Yugot Elementary School exhibits several of these conditions, making it representative of the systemic challenges experienced by LMS communities in Western Visayas. Situated far from Mina’s poblacion, the school is accessible only through rough, narrow roads that become difficult to traverse during the rainy season. These geographic constraints contribute to the school’s limited access to government services and logistical support. YES operates with a small teaching workforce managing multigrade classes due to its low but dispersed student population. Facilities are either makeshift or constructed from nonstandard materials, reflecting long-standing infrastructure gaps. The school’s lack of enough classrooms, limited access to water, and minimal instructional resources further constrain teaching and learning processes. Additionally, a significant proportion of the learners come from marginalized households whose livelihoods are tied to subsistence agriculture and seasonal labor, shaping the socio-economic context in which the school functions.

Figure 1.

Makeshift Canteen of Yugot Elementary School.

Figure 1.

Makeshift Canteen of Yugot Elementary School.

SDG Target 4.a Effective Learning Environments (Build and Upgrade Education Facilities that Child, Disability, and Gender Sensitive and Provide Safe, Non-Violent, Inclusive, and Effective Learning Environments for All)

The SDG4 Target 4.a. on effective learning environments recognizes and addresses the need for adequate physical infrastructure and safe, inclusive environments. These environments help nurture learning for all, regardless of the background, sex or disability status of children. YES facilities have been improving in recent years, with the construction of new classrooms. Electricity access is available to the school as of 2025. Recent data also suggests that access to computers is not available although internet is accessible to teachers only. There are five sanitation facilities and three handwashing facilities while drinking water is sourced from a deep well. SDG 4.a underscores the importance of safe, inclusive, and effective learning environments, recognizing that adequate physical infrastructure and essential services are prerequisites for achieving quality education. This target is particularly relevant for Last Mile Schools such as Yugot Elementary School (YES), where geographical isolation and socio-economic constraints historically limit resource availability and learning opportunities. At YES, recent years have seen incremental improvements in physical facilities, including the construction of new classrooms and the establishment of stable electricity access as of 2025 (

Table 1). The school now operates with five multigrade classrooms, a notable development for a geographically isolated school. These improvements signal progress in meeting SDG 4.a’s call for enhanced learning spaces. However, despite these gains, the school continues to face substantial gaps that directly affect pedagogy, student engagement, and equity. A critical concern is the absence of computers for pedagogical purposes, which restricts opportunities for digital literacy and ICT-integrated learning, skills that are increasingly essential in the 21st century and highlighted in SDG 4 competencies. While internet connectivity is available to teachers, the lack of learner-level ICT access limits the potential for interactive, technology-enhanced instruction and reduces opportunities to integrate learning management systems, online assessments, or multimedia resources. This digital divide is pronounced in Last Mile Schools and reinforces systemic inequities in access to contemporary learning tools. In terms of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) facilities, YES maintains five single-sex sanitation facilities and three functional handwashing stations. These contribute to a safer, more hygienic environment conducive to student well-being. However, the school’s reliance on a deep well for drinking water raises concerns about water potability, safety, and sustainability particularly during dry seasons or extreme weather, where supply may be disrupted. Reliable access to clean drinking water is not only a basic service but also directly affects attendance, learner comfort, and health outcomes. Despite improved classroom structures, the school still lacks several key facility types central to an enabling learning environment: no dedicated library, no laboratory, and only a makeshift canteen is available. The absence of a library limits opportunities for reading enrichment and research activities that support literacy development and independent learning. The lack of a science laboratory further constrains experiential learning and inquiry-based teaching, critical components of the K–12 curriculum and essential for fostering scientific literacy. Furthermore, YES has no adapted infrastructure or learning materials for students with disabilities, which runs counter to the SDG 4 commitment to inclusivity. Without assistive devices, accessible pathways, or specialized learning resources, learners with disabilities, if present, would face significant barriers to participation and equitable learning. Overall, while YES has made progress in expanding classroom infrastructure and securing basic utilities, its partial alignment with SDG 4.a reveals a learning environment that remains fragile, under resourced, and highly dependent on local socio-ecological conditions. The gaps in ICT resources, specialized learning facilities, inclusive infrastructure, and reliable water services illustrate how structural deprivation continues to shape educational experiences in Last Mile contexts. These conditions, when viewed through a socio-ecological systems perspective, interact with factors such as community capacity, environmental constraints, and teacher workload—ultimately influencing the school’s SDG 4 performance and student learning outcomes.

SDG Target 4.c Teachers and Educators (By 2030, substantially increase the supply of qualified teachers, including through international cooperation for teacher training in developing countries, especially least developed countries and small island developing States)

Teachers constitute the backbone of the education system and are central to the achievement of SDG 4: Quality Education. Target 4.c specifically emphasizes the need to increase the supply of qualified, trained, and supported teachers, recognizing that inequities in education are often amplified in remote and disadvantaged areas where teacher shortages, limited training opportunities, and uneven deployment persist. Ensuring that teachers are well-prepared, professionally supported, and equitably distributed is essential for guaranteeing quality learning outcomes, particularly in Last Mile Schools. In the Philippines, national policies such as Republic Act 7836 (The Philippine Teachers Professionalization Act of 1994) and DepEd hiring standards require that teachers possess at least a Bachelor of Elementary Education (BEEd) for primary education or an equivalent degree supplemented by a Certificate in Professional Education. Passing the Licensure Examination for Teachers (LET) is mandatory, ensuring a minimum level of professional competence among educators. These requirements align with the global call for a professionally qualified teaching workforce capable of advancing inclusive, equitable, and effective instruction. At Yugot Elementary School (YES), the teaching workforce consists of eight teachers, all of whom hold BEEd degrees and are LET passers (

Table 2). This demonstrates compliance with national qualification standards and reflects a baseline level of professional preparation necessary for delivering the K–12 curriculum. The presence of licensed teachers is a significant strength for a geographically isolated school, where recruitment and retention are often challenging due to difficult terrain, limited amenities, and the multi-grade teaching setup. However, despite meeting the minimum qualification requirements, none of the teachers at YES holds a master’s or doctorate degree, indicating an absence of advanced professional training. This gap has implications for SDG 4’s emphasis on strengthening teacher capacity and for DepEd’s broader goals of enhancing instructional quality through continuous professional development. Teachers with graduate-level training tend to have stronger pedagogical sophistication, deeper content knowledge, enhanced research literacy, and greater readiness to implement innovative or differentiated instructional strategies skills especially critical in complex learning environments such as multigrade classrooms. The lack of teachers with postgraduate training is further magnified in the socio-ecological context of a Last Mile School. Remote settings often limit access to graduate programs, mentorship opportunities, professional learning communities, and capacity-building initiatives typically available in urban centers. Travel constraints, financial limitations, and heavy workloads, particularly in multigrade settings, discourage teachers from pursuing higher degrees. As a result, the cycle of limited professional growth can perpetuate instructional challenges, affecting student learning outcomes and overall SDG 4 performance. Gender distribution at YES (five female and three male teachers) reflects typical patterns in the Philippine elementary education sector, but it is the capacity, not merely the composition, of the teaching staff that critically influences quality learning. Without advanced training, teachers may struggle to implement differentiated instruction, integrate ICT tools (especially given the lack of computers), manage multigrade classes effectively, and respond to diverse learner needs including those of Indigenous Peoples (IP) learners and potential learners with disabilities. Overall, while YES demonstrates compliance with basic teacher qualification standards, its limited access to advanced professional development presents a significant barrier to achieving SDG 4 targets related to high-quality teaching and learning. Strengthening teacher capacity in Last Mile Schools requires not only recruitment of qualified personnel but also sustained institutional and community support for continuous professional development. In the socio-ecological systems perspective, the professional growth of teachers is both shaped by and contributes to the broader learning environment, ultimately influencing learner outcomes and the school’s overall SDG 4 performance.

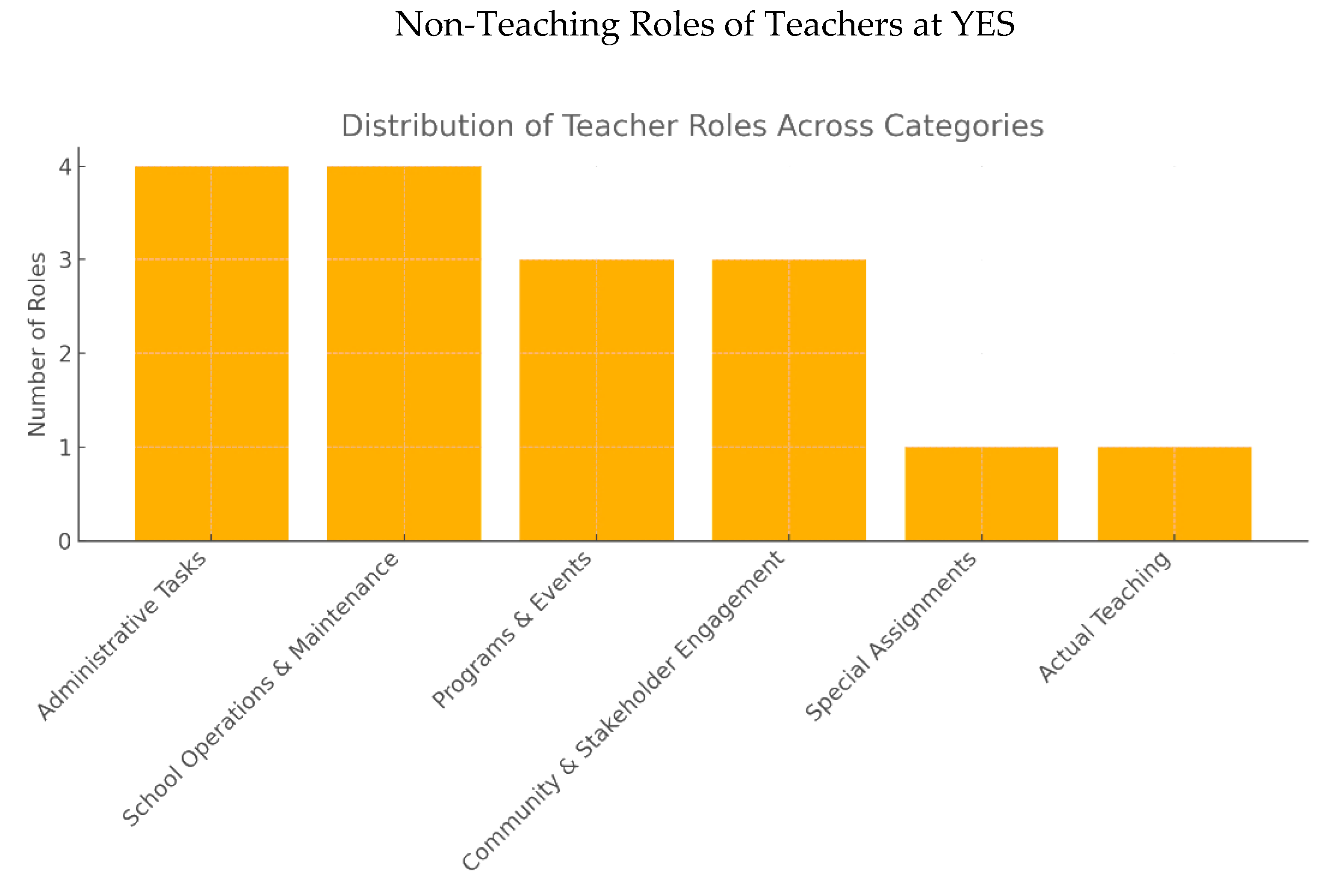

Teachers in Yugot Elementary School carry a wide range of non-teaching responsibilities (

Figure 2) that significantly shape their capacity to deliver quality instruction, a key requirement of SDG 4. Beyond classroom teaching, they handle extensive administrative work such as preparing school forms (SF 1, 2, 4, 5), updating learner information in LIS and EBEIS, and completing accomplishment reports. They also take charge of school operations and maintenance, including documentation for audits, property inventory, school beautification, and even minor classroom repairs tasks typically assigned to support staff in better resourced schools. In addition, teachers organize and manage school programs and events like Nutrition Month and serve on multiple committees throughout the year. Their roles extend to stakeholder engagement, participating in community outreach activities and clean-up drives, thereby strengthening school community ties but adding to their workload. As focal persons for programs such as GAD and DRRM, teachers coordinate with LGUs, communicate with parents, and assist in division or regional activities. Collectively, these non-teaching duties reflect the systemic realities of a Last Mile School, where limited personnel and resource constraints compel teachers to assume multiple roles. This heavy workload reduces the time available for lesson preparation, individualized support, and pedagogical improvement, ultimately affecting the school’s overall SDG 4 performance and highlighting the need for stronger institutional support to protect teachers’ instructional focus.

Teaching Roles

Actual teaching in YES follows a multigrade instructional model, requiring teachers to manage multiple grade levels simultaneously within a single classroom. The teaching flow typically begins with a whole-class routine such as morning greetings, shared discussions, or foundational skill review to establish structure and a sense of community among learners of different ages. After this shared opening, instruction shifts into small-group or independent learning activities that are carefully differentiated according to grade level competencies. While one group engages in seatwork, practice tasks, or self-directed learning, the teacher delivers focused, grade-specific instruction to another group, ensuring that each set of learners receives appropriate guidance aligned with their curriculum needs. The teacher then rotates among groups, balancing direct instruction, monitoring, and feedback across multiple grade levels. This continuous cycle of grouping, rotating, and managing independent tasks reflects the complex demands of multigrade teaching, where effective learning relies on strategic classroom organization, strong instructional planning, and the teacher’s ability to simultaneously address diverse learner needs within a resource-constrained environment.

SDG Target 4.1 (Universal primary and secondary education): By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes

The enrolment profile of Yugot Elementary School (YES) for School Year 2025–2026 (

Table 3) provides an initial picture of the school’s progress toward SDG Target 4.1, which aims to ensure that all children complete free, equitable, and quality primary education. The data show relatively stable enrolment across the upper primary grades, with 15 learners in Grade 4, 14 in Grade 5, and 20 in Grade 6, indicating that learners are generally staying in school through the later years of elementary education. This is significant for a Last Mile School, where geographic isolation, household responsibilities, and socio-economic constraints often lead to dropout or irregular attendance. The near-balanced gender distribution particularly the equal number of male and female learners in Grade 6 suggests that both boys and girls have equitable access to education, aligning with the equity dimension of SDG 4.1. However, the small cohort sizes also reflect the multigrade and low-enrolment nature of the school, which can influence learning conditions through limited peer interaction, combined classes, and shared teacher attention. While the enrolment data indicate that access to free primary education is being met, further analysis is needed to determine whether these learners are achieving relevant and effective learning outcomes, which is the core metric of SDG Target 4.1.

SDG 4 Performance in Terms of Learning Outcomes of the Identified Last Mile School (LMS)

4.1.1.b: Proportion of Children and Young People at the End of Primary School Achieving at Least a Minimum Proficiency Level

The Grade 4 Philippine Informal Reading Inventory (Phil-IRI) Group Screening Test (

Table 4) results provide crucial insight into SDG Indicator 4.1.1.b, which measures the proportion of children achieving at least a minimum proficiency level at the end of primary schooling. At Yugot Elementary School, the data reveal significant challenges in foundational literacy. Of the 15 Grade 4 learners assessed, more than half (8 learners) are at the Frustration Level, meaning they struggle with grade-level texts and cannot comprehend reading material without substantial support. Another six learners fall within the Instructional Level, capable of understanding texts only with guided assistance. Critically, only one learner reached the Independent Level, demonstrating mastery of grade-appropriate reading skills. This distribution shows that a majority of learners have not yet met the minimum proficiency standards expected by SDG 4.1.1.b. For a multigrade, resource-constrained school, this indicates systemic barriers limited access to reading materials, insufficient remedial instruction time, and competing instructional demands across grade levels. The results underscore an urgent need for targeted reading interventions, strengthened early-grade literacy instruction, and greater instructional support to ensure learners progress toward meaningful reading proficiency by the end of primary school.

More than half of Grade 4 learners are at the Frustration Level, indicating severe reading comprehension difficulties. Only one learner can independently handle grade-level texts. This suggests foundational reading skills are fragile and require intensive remediation.

Grade 5 demonstrates the most promising literacy performance across all tested grade levels (

Table 5). More than one-third of the learners can already read independently, confidently navigating grade-level texts without teacher assistance. A majority fall under the instructional level, meaning they can comprehend material with strategic guidance, an indicator that their foundational skills are steadily solidifying. Only one learner remains at the frustration level, showing that severe reading difficulties are significantly less prevalent in this cohort. The clear improvement from Grade 4 to Grade 5 reflects a positive developmental trajectory and may signal the impact of sustained reading exposure, stronger classroom routines, or targeted interventions such as guided reading sessions, peer-assisted learning, or small-group remediation. This pattern suggests that when instructional supports are consistent and developmentally attuned, learners in multigrade and resource-limited settings can still achieve meaningful gains in literacy proficiency.

Grade 5 has the strongest literacy performance among the three grade levels. A sizeable group (36%) can read independently, while the majority (57%) are instructional, meaning they can read with teacher support. The improvement from Grade 4 to 5 suggests that targeted reading interventions or a more stable learning environment may have contributed to progress.

Grade 6 presents a critical literacy concern, highlighting a significant setback in reading proficiency at Yugot Elementary School (

Table 6). None of the 20 learners assessed can read independently, and the majority which is 14 learners, or 70%, remain at the frustration level, struggling significantly with grade level texts. Only six learners are at the instructional level, able to read with teacher guidance, indicating that foundational literacy skills are largely fragile in this cohort. This sharp decline from the relatively stronger performance observed in Grade 5 suggests the presence of cumulative learning losses, which may stem from a combination of factors common in Last Mile Schools: interruptions in schooling, the complexities of multigrade instruction that divide teacher attention, limited access to reading materials, and socio-economic burdens that affect regular engagement and study time. The Grade 6 results underscore an urgent need for intensive, targeted literacy interventions to remediate foundational gaps and prevent further erosion of learning outcomes, ensuring that learners have the opportunity to achieve the minimum proficiency levels required by SDG 4.1.1.b.

Grade 6 shows a critical literacy crisis. Not a single learner can read independently. Seven out of ten learners struggle significantly. This sharp decline from Grade 5 indicates cumulative learning losses, possibly due to interrupted schooling, multigrade challenges, limited exposure to reading materials and socio-economic burdens that hinder consistent learning.

General Literacy Trends

Literacy achievement is highly inconsistent across grade levels. The high frustration rates in Grades 4 and 6 reflect systemic reading challenges. There is no upward trend from Grades 4 to 6, showing that as learners advance, literacy gaps widen.

Numeracy Profile

Grade 5 reveals serious numeracy challenges. Learners struggle with fundamental math concepts and computation. Grade 6 displays very low numeracy mastery. Almost all learners are “Low Proficient.” None reached grade-level proficiency. This indicates weak number sense, poor mastery of operations, difficulty with multi-step problems, and strong possibility of pandemic-related and LMS-related learning losses.

General Literacy and Numeracy Trends

The numeracy assessment at Yugot Elementary School highlights (

Table 7) serious challenges in learners’ mastery of fundamental mathematical concepts across all grade levels. In Grade 4, most learners are classified as emerging or low proficient, with none achieving grade-level proficiency. This indicates difficulties in understanding basic operations, number sense, and problem-solving skills. Grade 5 shows a similar pattern, with the majority of learners still at the emerging or low proficient level and only a few approaching developing proficiency. By Grade 6, the situation becomes critical: nearly all learners remain low proficient, and none have reached grade-level proficiency. This trend reflects weak foundational numeracy skills, poor mastery of computations, and significant struggles with multi-step problems. The progressive decline in proficiency from lower to upper grades suggests cumulative learning losses, likely exacerbated by the multigrade instructional setup, limited access to learning resources, interruptions in schooling (including pandemic-related disruptions), and socio-economic constraints typical of Last Mile Schools. These findings underscore the urgent need for targeted remedial instruction, differentiated teaching strategies, and structured support to strengthen learners’ numeracy skills and prevent further gaps in mathematical competence. Performance declines as learners progress to higher grades. Grades 5 and 6 have no Transitioning/Proficient learners. Learners retain basic concepts at earlier grades but fail to master more complex competencies. The literacy and numeracy performance of Grades 4–6 learners in Yugot Elementary School reveals significant challenges in achieving SDG 4: Quality Education, particularly in providing equitable and meaningful learning opportunities for children in Last Mile Schools. The consistently low proficiency rates especially the high number of learners in the frustration and low proficient levels indicate that while learners are progressing in grade level, they are not mastering foundational competencies required under SDG 4.1, which emphasizes minimum proficiency in reading and mathematics. These results reflect deeper inequities connected to the school’s Last Mile context, where multigrade teaching, limited instructional materials, absence of electricity, and socio-economic constraints affect consistent learning engagement, thereby highlighting concerns under SDG 4.5 on reducing educational disparities for marginalized groups. Moreover, the school’s nonstandard classrooms, inadequate learning facilities, and constrained physical environment directly hinder effective instruction and align with deficiencies described in SDG 4.a, which advocates for safe and conducive learning spaces. Finally, the limited number of teachers, who must simultaneously manage multiple grade levels and diverse learner needs, underscores challenges related to SDG 4.c, which calls for increasing the supply and support of qualified teachers in underserved areas. Collectively, these factors show that the school’s learning outcomes are shaped not only by learner ability but also by systemic barriers that must be addressed to realize the full intent of SDG 4 in Last Mile Schools.

4. Discussion

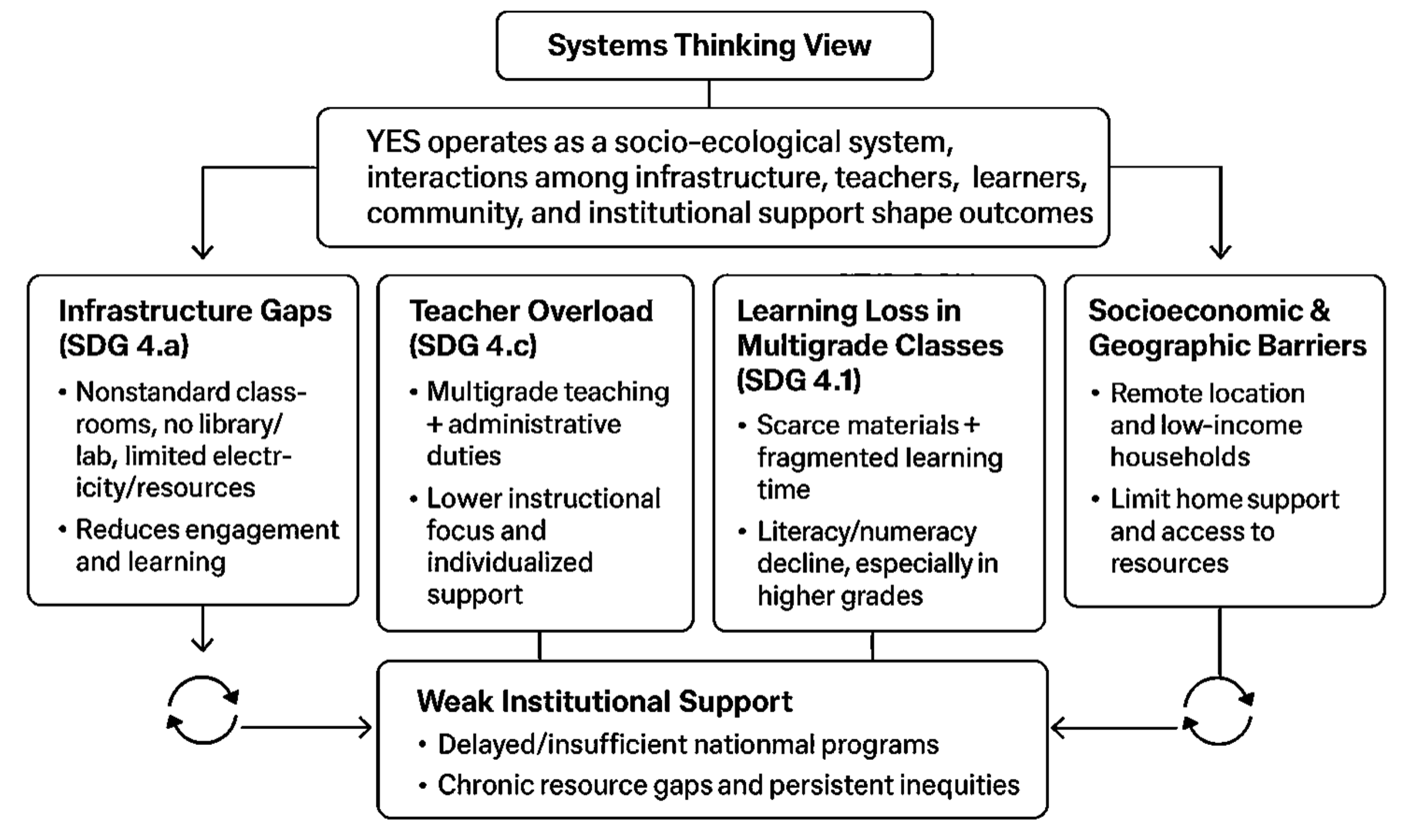

Understanding How the Current Conditions of the Identified Last Mile School Impact its SDG 4 Performance Using Systems Thinking Model

The current condition of YES in terms of SDG 4 means of implementation and learning outcomes can be understood through systems thinking model. Using a systems thinking lens, Yugot Elementary School (YES) operates as a socio-ecological system where physical infrastructure, teacher capacity, learner characteristics, community context, and institutional support interact in reinforcing or weakening loops that influence SDG 4 outcomes. In sustainability science, education quality emerges not from isolated inputs but from the dynamic interactions between subsystems; in YES, several feedback loops hinder the school’s ability to meet the SDG 4 targets.

1. Infrastructure Deficits as a Structural Constraint (SDG 4.a)

Yugot Elementary School (YES) exhibits characteristics typical of Last Mile Schools (LMS), including multigrade classes, nonstandard classrooms, limited electricity-dependent resources, absence of a library and laboratory, makeshift canteen, and no disability-inclusive facilities. These deficits directly constrain instructional delivery and indirectly affect learner engagement. A reinforcing loop emerges whereby poor infrastructure limits instructional strategies, weakening learning experiences, reducing learner proficiency, and decreasing motivation, thereby perpetuating poor outcomes [

1,

16]. The lack of computers, internet access, and adapted learning materials forms systemic barriers to SDG 4.a’s vision of “effective, inclusive learning environments” [

9,

11]. Even where electricity is available, its educational utility remains minimal due to the absence of equipment, highlighting the school’s low resilience and reliance on external support [

10,

12].

2. Teacher Overload and Multigrade Pressures (SDG 4.c)

YES teachers are fully licensed but face substantial non-teaching workloads, including administrative tasks, community outreach, school events, facility maintenance, and coordination with local government units. With eight teachers handling multigrade classes and multiple responsibilities, actual teaching time is reduced, creating a balancing loop that suppresses educational quality: additional non-teaching roles decrease instructional focus, reduce individualized teaching for struggling students, lower performance, and increase teacher burden due to remediation demands [

8,

9]. From a sustainability science perspective, this misalignment between mandated and actual teacher roles represents institutional inefficiency, compromising long-term educational quality [

11,

12].

3. Multigrade Structure and Learning Loss (SDG 4.1)

Multigrade teaching requires advanced planning and differentiated instruction, but YES faces scarce teaching materials, few reference books, no library, and limited quiet learning space. Consequently, learning time is fragmented across levels, and weak foundational skills lead to reinforcing learning-loss loops. Reading literacy declines sharply by grade level: in Grade 4, the majority of learners are at the frustration level, Grade 5 shows relatively stronger performance, but Grade 6 demonstrates a sharp decline, with nearly all learners at the frustration level. Numeracy follows a similar pattern, with no learners in Grades 5 and 6 reaching proficiency [

6,

9]. These cumulative deficits reflect a system unable to regenerate learning capacity across time, indicating low systemic resilience [

10,

12].

4. Socioeconomic and Geographic Barriers as External Stressors

YES is situated in a remote barangay with rough terrain access, and most learners come from low income households reliant on seasonal labor. These factors affect attendance, readiness to learn, and home literacy support, while LMS communities often lack reading materials and internet access, limiting learning opportunities outside school [

13,

14]. This external environment creates a pressure loop: low socioeconomic conditions limit home learning support, leading to weaker literacy and numeracy, higher remediation demand, and increased instructional strain on multigrade teachers. These findings indicate that learning outcomes are embedded within a broader socio-ecological system [

12].

5. Weak Institutional Support as a Systemic Leverage Gap

YES’s status as a Last Mile School highlights persistent gaps in institutional response. Despite national LMS programs, the school shows no new construction, lacks key facilities, and continues to rely on makeshift structures [

1,

5]. Delayed or insufficient central support generates chronic resource deprivation and sustained learning inequities. From a sustainability science perspective, institutional governance is a critical system component, and its weakness constrains overall resilience [

11,

16]. Empirical data from PIDS [

9], DepEd [

1], and EDCOM [

16] confirm that despite nationwide gains in enrollment and policy reforms, the Philippines continues to struggle with a “learning poverty” crisis especially in remote and underserved areas. The documented national patterns of infrastructure shortfalls, teacher overload, and weak institutional support resonate strongly with the on-the-ground realities observed at YES. By situating this case study within the broader national context, the research underscores how systemic, structural, and socio-ecological factors intersect to shape educational outcomes. The patterns observed at YES echo PIDS’s recommendation for holistic, integrated interventions from resource allocation and teacher support to community involvement and infrastructure development.

Figure 3.

Systems thinking perspective of the learning outcomes in an LMS.

Figure 3.

Systems thinking perspective of the learning outcomes in an LMS.

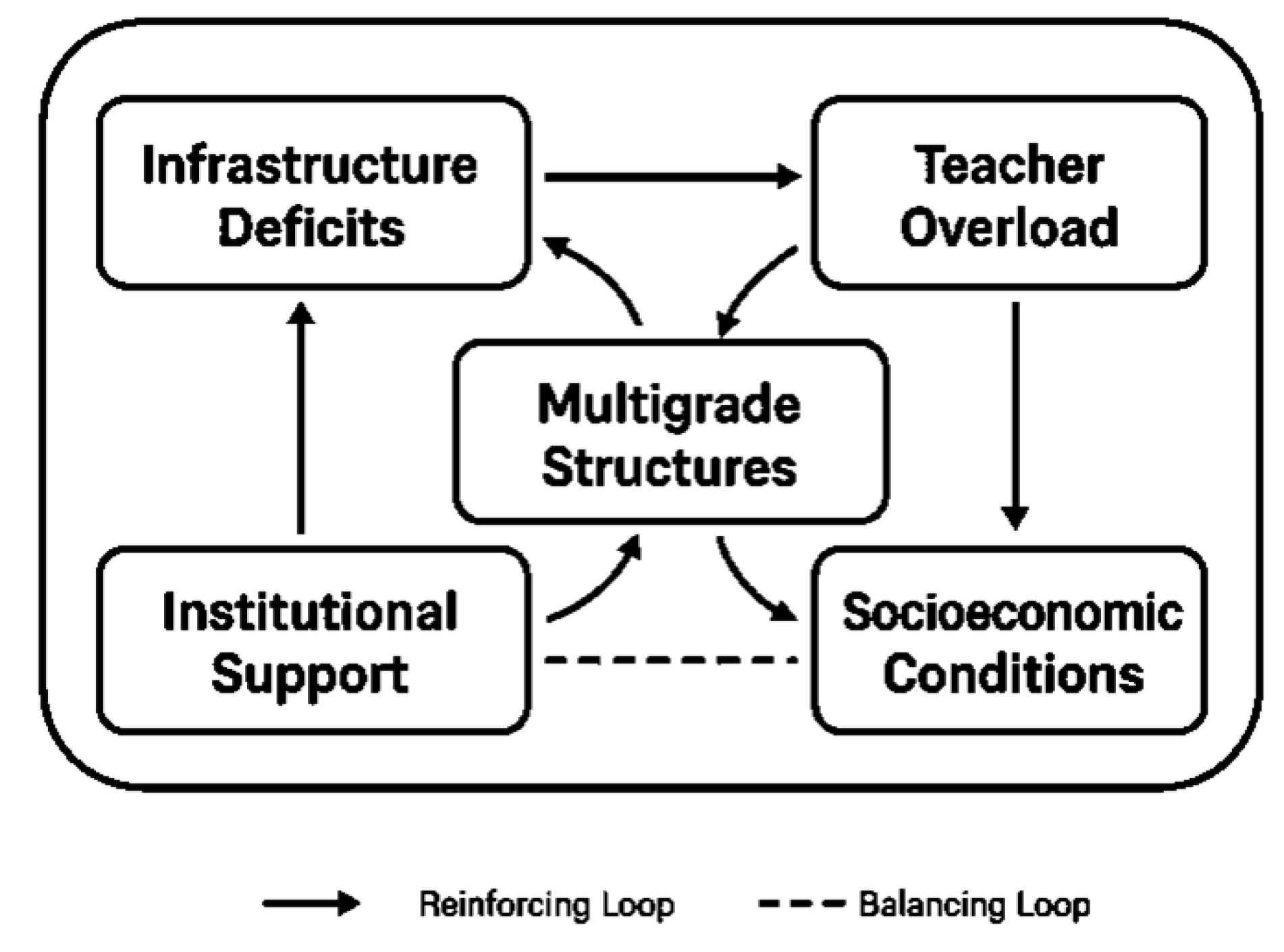

Integrating the Five Dimensions within a Socio-Ecological Systems Model

The socio-ecological systems model provides a holistic lens to understand how the multiple dimensions of Yugot Elementary School (YES) interact to shape its SDG 4 performance. In this framework, infrastructure deficits, teacher overload, multigrade structures, socioeconomic conditions, and institutional support function as interconnected subsystems whose interactions create reinforcing or balancing loops that influence learning outcomes [

10,

12]. Physical infrastructure limitations, such as nonstandard classrooms, lack of libraries and laboratories, and insufficient electricity-dependent resources, constrain instructional strategies and diminish learner engagement [

1,

16]. These constraints are amplified by teacher workload and multigrade pressures, which reduce individualized support and heighten remediation demands, thereby reinforcing learning loss [

8,

9].

Figure 4.

LMS as a socio-ecological system.

Figure 4.

LMS as a socio-ecological system.

Concurrently, learners’ socioeconomic and geographic realities including low household income, seasonal labor dependence, and limited access to reading materials exacerbate instructional challenges and reduce home learning support, creating external stressors that feed back into the system [

13,

14]. Weak institutional support, reflected in delayed construction, resource gaps, and limited policy implementation, serves as a systemic bottleneck, curbing the capacity of the school to adapt and recover from these compounded pressures [

5,

16]. Together, these interrelated subsystems illustrate a reinforcing cycle of structural constraints, pedagogical strain, and socio-ecological pressures that collectively undermine SDG 4 targets, particularly literacy and numeracy outcomes [

9,

11]. By framing YES as a socio ecological system, the study highlights that improvements in SDG 4 performance require integrated interventions targeting infrastructure, teacher capacity, multigrade pedagogy, socioeconomic support, and institutional governance, rather than isolated solutions, thereby providing actionable insights for policy and practice in Last Mile Schools. Thus, this case study does not merely provide a localized description, it contributes to a deeper understanding of how national-level educational inequities documented by PIDS, EDCOM, and DepEd manifest in Last Mile Schools, and how systemic reform, guided by a socio-ecological lens, may be necessary to meaningfully advance SDG 4 in marginal contexts.

5. Conclusions

Based on the findings of the study, the following conclusions are hereby advanced:

1. YES has weak SDG 4 performance

Literacy and numeracy results show that most learners in Grades 4–6 fail to meet minimum proficiency. The absence of independent readers in Grade 6 and the prevalence of “Low Proficient” numeracy levels reveal significant gaps in foundational learning.

2. The school’s physical environment does not meet SDG 4.a standards

Makeshift structures, no computer facilities, no laboratory, no library, lack of disability-inclusive facilities, and multigrade classrooms inhibit the creation of safe, inclusive, and effective learning environments.

3. Teacher capacity (SDG 4.c) is compromised by system overload

Teachers are licensed but carry an excessive number of non-teaching tasks, diminishing their ability to deliver quality instruction.

4. Systemic barriers reinforce each other

Infrastructure deficits, teacher overload, multigrade burdens, and socioeconomic constraints create a reinforcing cycle that depresses learning outcomes over time.

Overall, YES currently falls short of SDG 4 goals, not due to lack of effort from stakeholders, but due to structural, institutional, and contextual constraints characteristic of Last Mile Schools.