Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Region

2.2. Methodology Description

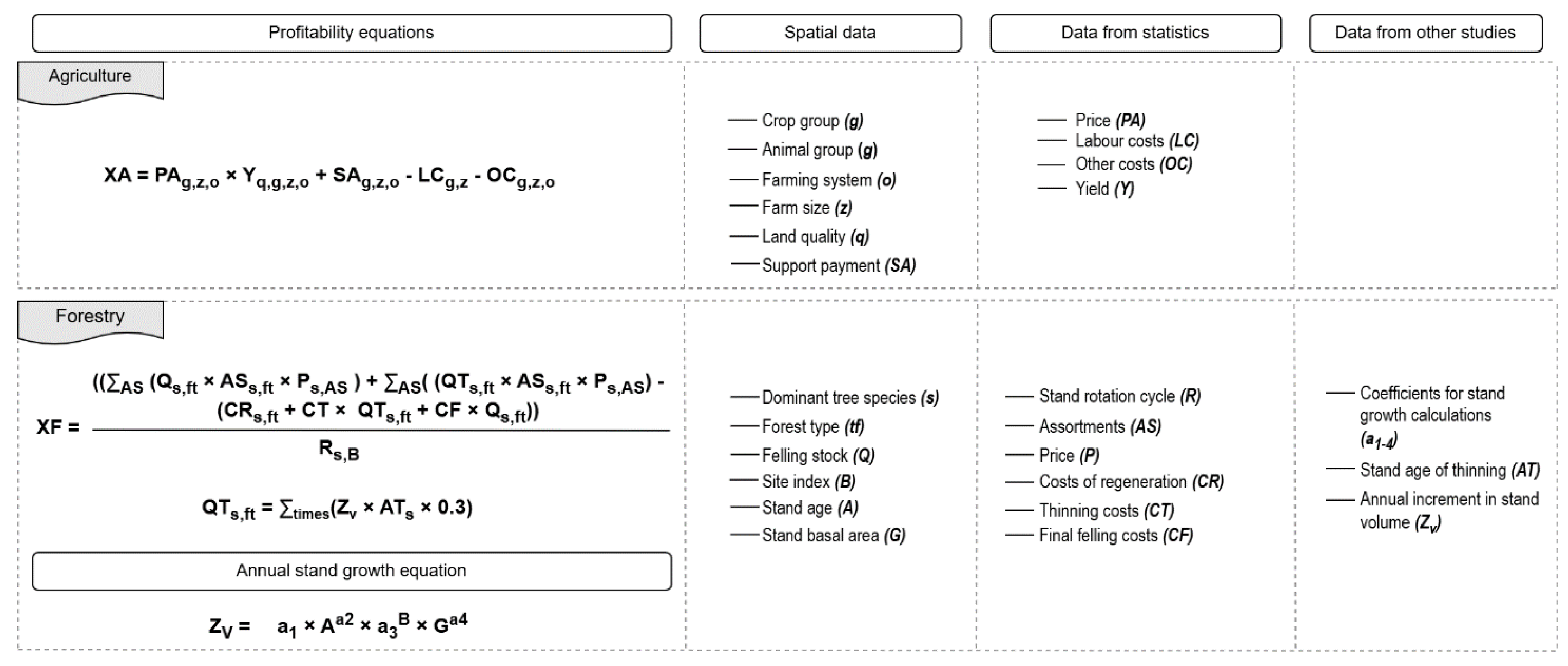

2.2.1. Profitability in Agriculture

2.2.2. Profitability in Forestry

2.3. Mapping at Parcel Level

2.4. Technical Implementation

3. Results

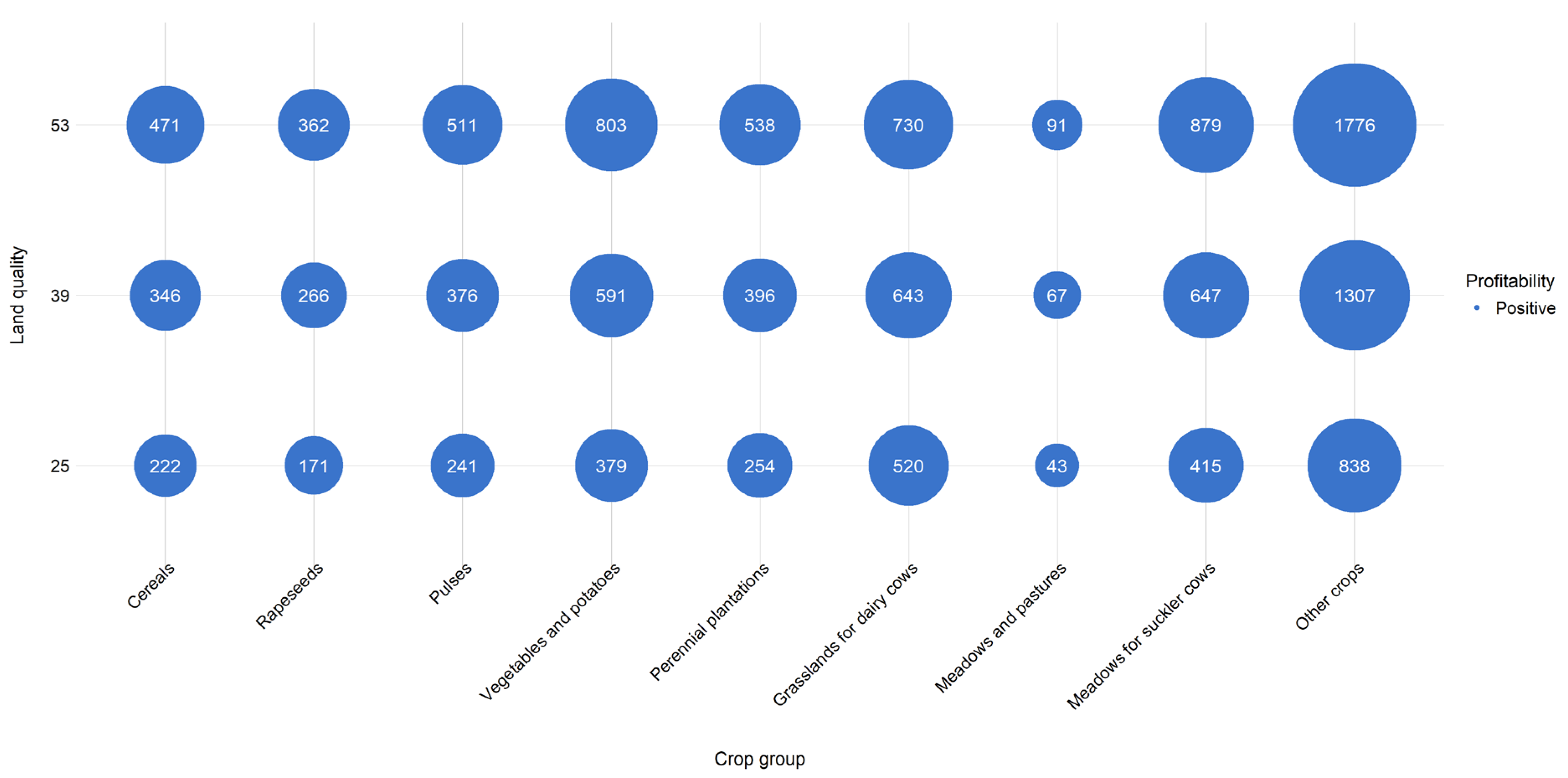

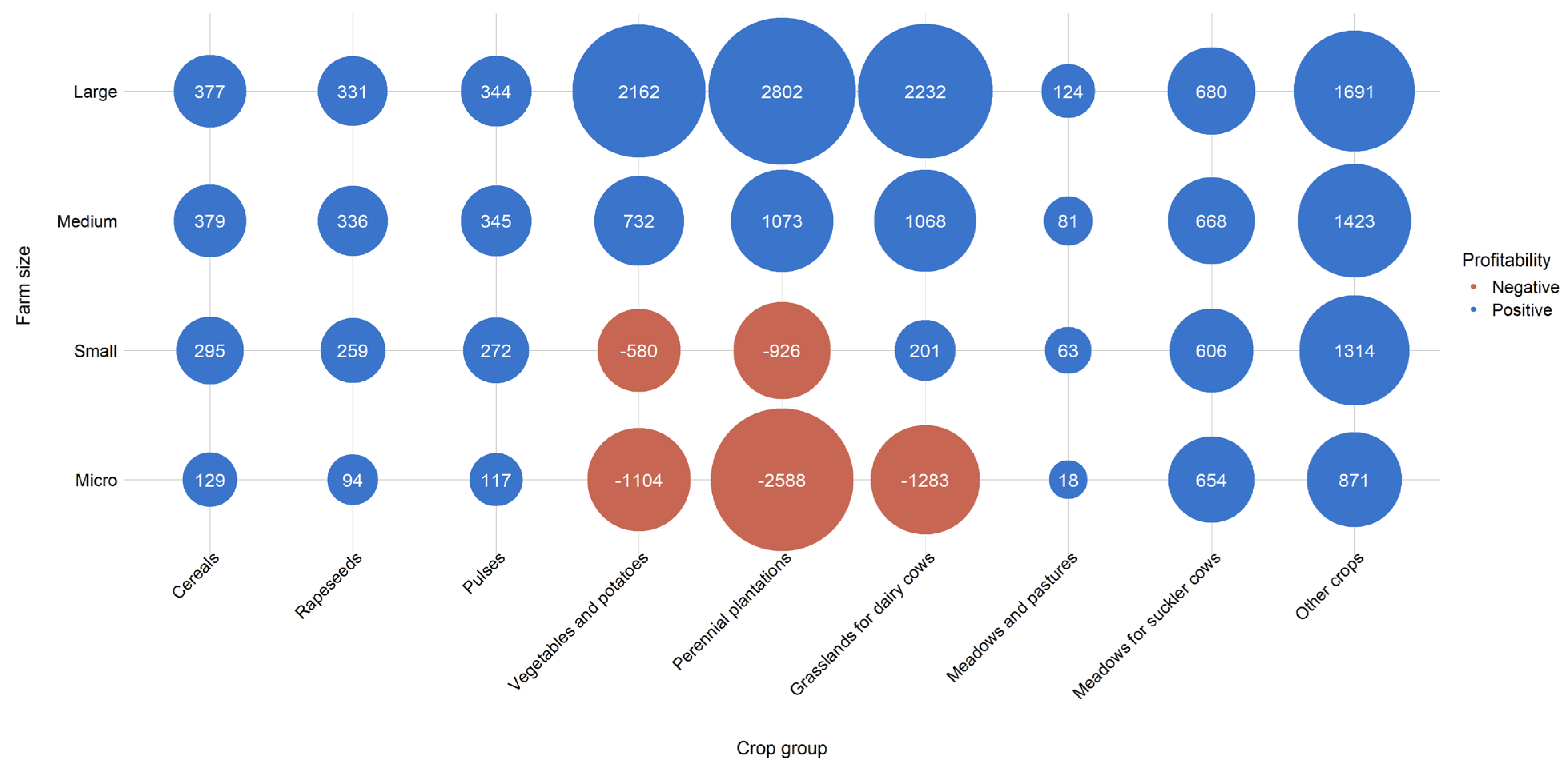

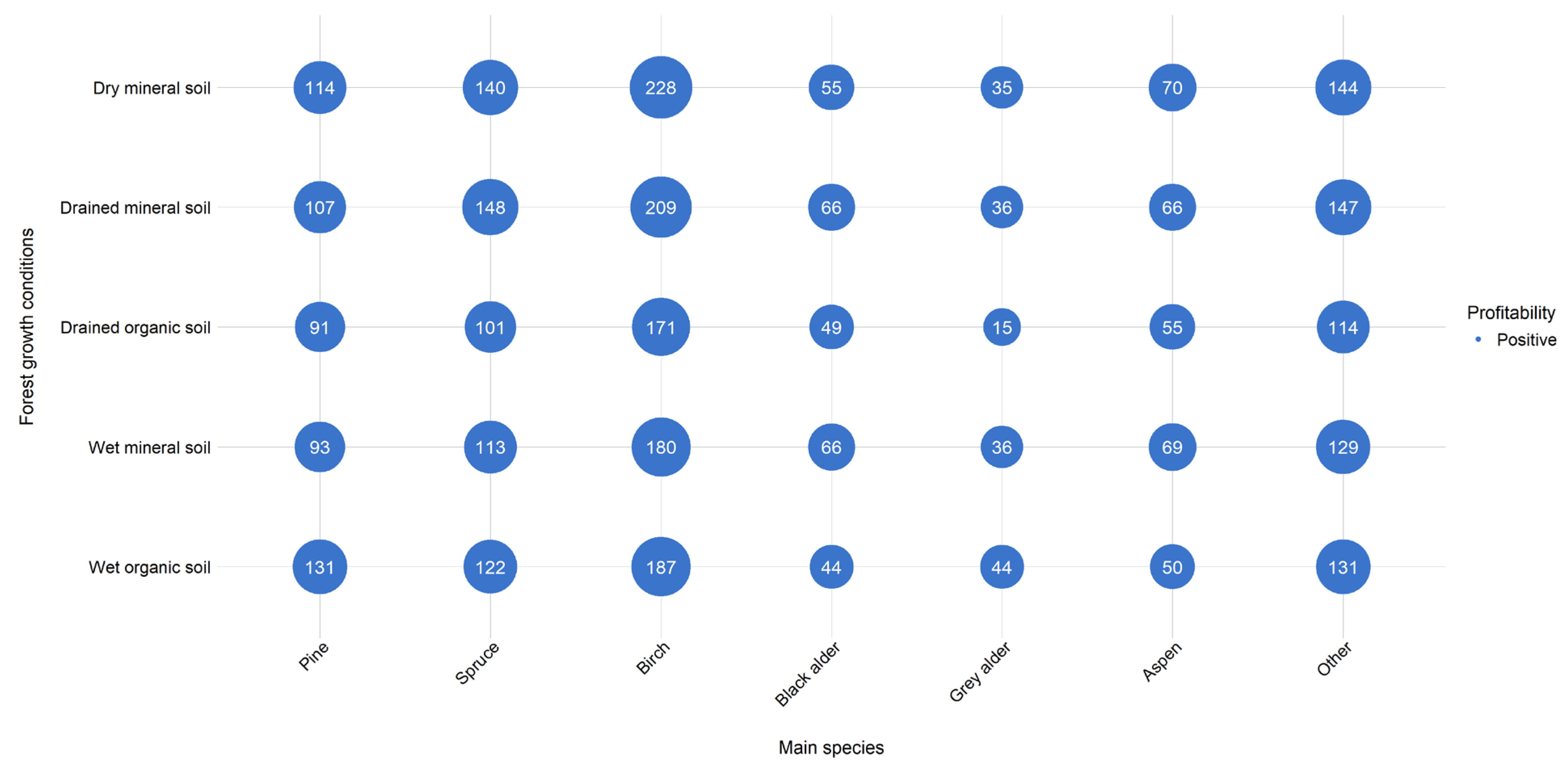

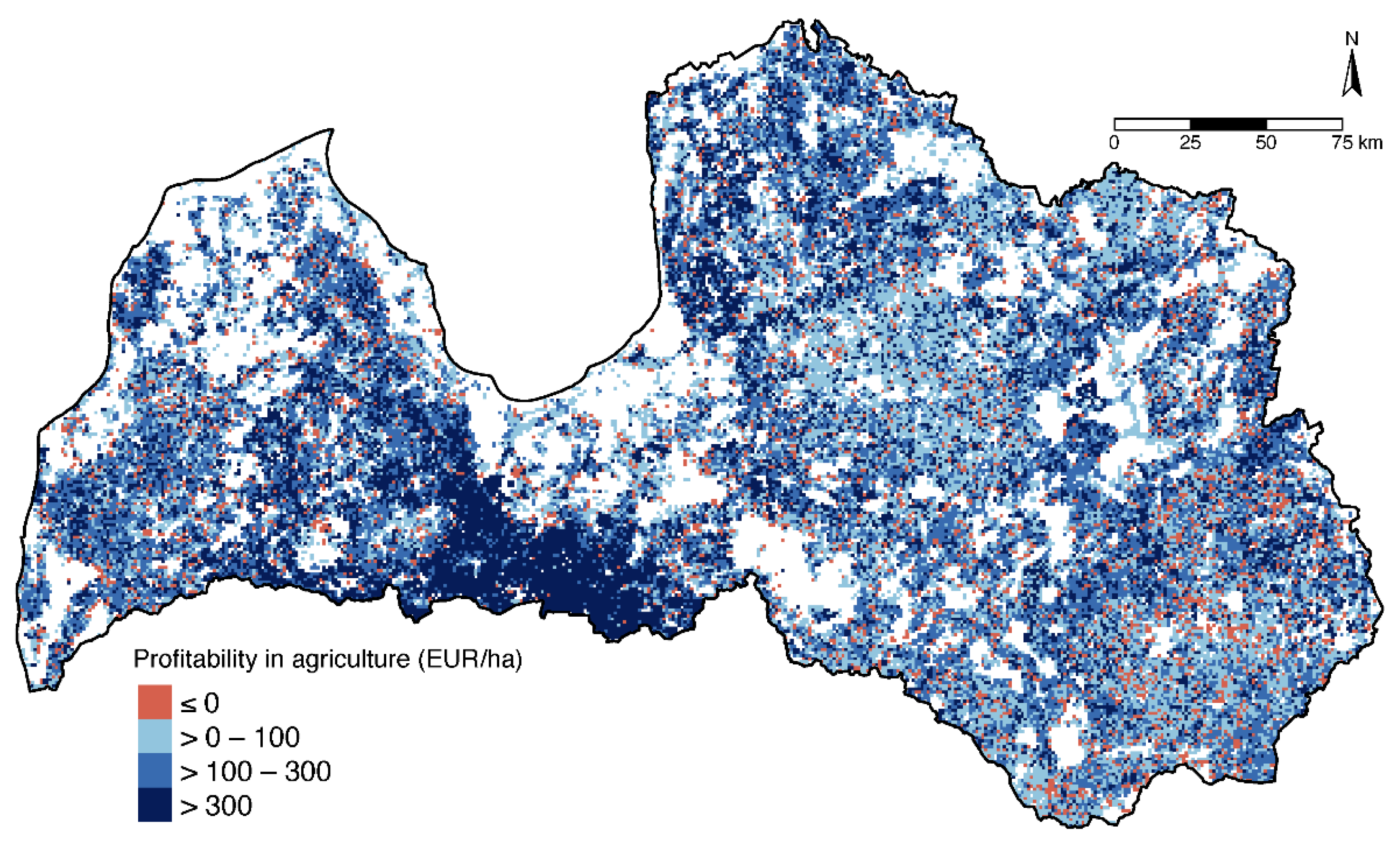

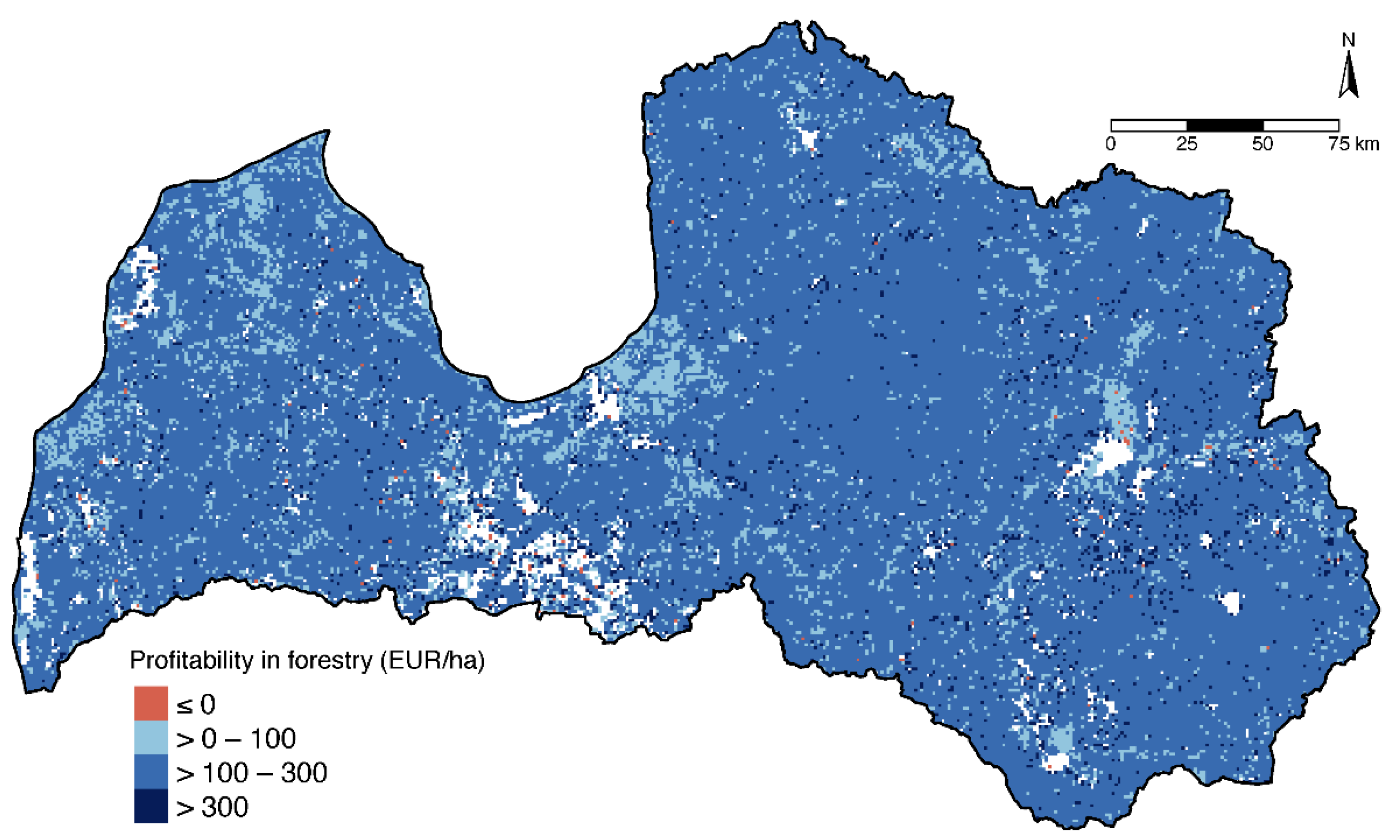

3.1. Per-Hectare Profitability Patterns for Agricultural and Forest Land

3.2. Mapping Agricultural and Forest Land Profitability

4. Discussion

4.1. Profitability Trade-Offs Between Agriculture And Forestry

4.2. Institutional Constraints and Policy Implications

4.3. Transferability and Generalisation of the Framework

4.4. Multi-Objective Land-Use Planning And Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A1

| Agricultural sector | Farm size, ha | |||

| Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms | |

| Cereals, rapeseeds, pulses | >300 | >100, ≤300 | >20, ≤100 | ≤20 |

| Vegetables (with potatoes) | >30 | >10, ≤30 | >2, ≤10 | ≤2 |

| Perennial plantations | >30 | >10, ≤30 | >2, ≤10 | ≤2 |

| Other crops (e.g. mustard, flaxseed, nectar plants, herbs, lavender, chamomile, caraway) | >150 | >50, ≤150 | >10, ≤50 | ≤10 |

| Fallow land | >300 | >100, ≤300 | >20, ≤100 | ≤20 |

| Grasslands | >300 | >100, ≤300 | >20, ≤100 | ≤20 |

| Meadows and pastures | >300 | >100, ≤300 | >20, ≤100 | ≤20 |

| Dairy cows (with calves) | >200 | >30, ≤200 | >4, ≤30 | ≤4 |

| Suckling cows (with calves) | >200 | >30, ≤200 | >4, ≤30 | ≤4 |

Appendix A2

| Factor | Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms |

| Conventional farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 196.84 | 196.84 | 177.16 | 157.47 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | land quality points * 0.1076574 | |||

| Support (EUR/ha) | 149.85 | 149.85 | 149.85 | 149.85 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 140.25 | 154.00 | 197.12 | 291.06 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 512.59 | 497.21 | 451.08 | 435.70 |

| Organic farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 272.07 | 272.07 | 244.87 | 217.66 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | land quality points * 0.1280373 | |||

| Support (EUR/ha) | 266.85 | 266.85 | 266.85 | 266.85 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 140.25 | 154.00 | 197.12 | 291.06 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 486.96 | 472.35 | 428.52 | 413.91 |

| Factor | Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms |

| Conventional farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 477.62 | 477.62 | 429.86 | 382.10 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | land quality points * 0.0426049 | |||

| Support (EUR/ha) | 187.85 | 187.85 | 187.85 | 187.85 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 140.25 | 154.00 | 197.12 | 291.06 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 627.10 | 608.29 | 551.85 | 533.03 |

| Organic farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 744.06 | 744.06 | 669.65 | 595.25 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | land quality points * 0.0525616 | |||

| Support (EUR/ha) | 266.85 | 266.85 | 266.85 | 266.85 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 140.25 | 154.00 | 197.12 | 291.06 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 595.74 | 577.87 | 524.26 | 506.38 |

| Factor | Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms |

| Conventional farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 251.81 | 251.81 | 226.63 | 201.45 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | land quality points * 0.0706193 | |||

| Support (EUR/ha) | 221.94 | 221.94 | 221.94 | 221.94 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 140.25 | 154.00 | 197.12 | 291.06 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 503.86 | 488.74 | 443.40 | 428.28 |

| Organic farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 413.44 | 413.44 | 372.10 | 330.75 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | land quality points * 0.0784871 | |||

| Support (EUR/ha) | 318.94 | 318.94 | 318.94 | 318.94 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 140.25 | 154.00 | 197.12 | 291.06 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 478.67 | 464.31 | 421.23 | 406.87 |

| Factor | Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms |

| Conventional farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 273.07 | 273.07 | 273.07 | 273.07 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 22.41 | 21.06 | 17.32 | 12.84 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 376.78 | 376.78 | 376.78 | 376.78 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 2 010.25 | 3 118.50 | 3 665.20 | 3 081.54 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 2 200.43 | 2 134.41 | 1 936.38 | 1 870.36 |

| Organic farms | ||||

| Price (EUR/t) | 427.65 | 427.65 | 427.65 | 427.65 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 9.30 | 7.86 | 7.18 | 5.68 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 939.90 | 939.90 | 939.90 | 939.90 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 2 010.25 | 3 118.50 | 3 665.20 | 3 081.54 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 2 090.41 | 2 027.69 | 1 839.56 | 1 776.84 |

| Factor | Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms |

| Price (EUR/t) | 1 737.43 | 1 737.43 | 1 737.43 | 1 737.43 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 7.30 | 6.86 | 5.64 | 4.18 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 285.64 | 285.64 | 285.64 | 285.64 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 2 187.90 | 3 395.70 | 3 985.52 | 3 354.12 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 7 978.81 | 7 739.45 | 7 021.35 | 6 781.99 |

| Factor | Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms |

| Conventional farms | ||||

| Revenue (EUR/ha) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 149.85 | 149.85 | 149.85 | 149.85 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 65.45 | 61.60 | 98.56 | 129.36 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 201.01 | 194.98 | 176.89 | 170.86 |

| Organic farms | ||||

| Revenue (EUR/ha) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 246.85 | 246.85 | 246.85 | 246.85 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 65.45 | 61.60 | 98.56 | 129.36 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 190.96 | 185.23 | 168.04 | 162.32 |

| Factor | Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms |

| Price (dry matter) (EUR/t) | 59.31 | 59.31 | 59.31 | 59.31 |

| Average yield (dry matter) (t/ha) | 4.68 | 4.68 | 4.68 | 4.68 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 149.85 | 149.85 | 149.85 | 149.85 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 149.60 | 231.00 | 271.04 | 406.56 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 102.02 | 98.96 | 89.78 | 86.72 |

| Factor | Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms |

| Price (EUR/t) | 36.90 | 36.90 | 36.90 | 36.90 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 3.81 | 3.02 | 2.46 | 1.87 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 149.85 | 149.85 | 149.85 | 149.85 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 28.05 | 46.20 | 55.44 | 83.16 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 138.42 | 134.27 | 121.81 | 117.66 |

| Factor | Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms |

| Price (EUR/t) | 2 700.00 | 2 700.00 | 2 700.00 | 2 700.00 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 149.85 | 149.85 | 149.85 | 149.85 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 514.25 | 793.10 | 936.32 | 1 390.62 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 374.65 | 363.41 | 329.69 | 318.45 |

| Factor | Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms |

| Price (EUR/t) | 318.01 | 308.37 | 279.46 | 240.92 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 8.81 | 6.20 | 5.70 | 4.32 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 235.87 | 235.87 | 235.87 | 235.87 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 813.45 | 816.20 | 1 207.36 | 1 787.94 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 662.58 | 642.71 | 583.07 | 563.20 |

| Factor | Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms |

| Price (EUR/t) | 3 180.10 | 3 180.10 | 3 180.10 | 3 180.10 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 132.01 | 132.01 | 132.01 | 132.01 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 224.40 | 246.40 | 338.80 | 300.30 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 331.07 | 321.14 | 291.34 | 281.41 |

| Factor | Large farms | Medium farms | Small farms | Micro farms |

| Price (EUR/t) | 2 750.00 | 2 750.00 | 2 750.00 | 2 750.00 |

| Average yield (t/ha) | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Support (EUR/ha) | 34.09 | 34.09 | 34.09 | 34.09 |

| Labor costs (EUR/ha) | 84.15 | 69.30 | 110.88 | 207.90 |

| Other costs and depreciation (EUR/ha) | 28.38 | 27.53 | 24.97 | 24.12 |

Appendix A3

| Dominant tree species | Type of assortments (proportion) | ||||

| Packing case timber | Veneer logs | Saw logs | Paper wood | Firewood | |

| Pine | 0.05 | - | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.05 |

| Spruce | 0.05 | - | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.05 |

| Birch | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.05 |

| Aspen | 0.25 | - | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.25 |

| Black alder | 0.05 | - | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.10 |

| Grey alder | 0.50 | - | - | - | 0.50 |

| Other species | 0.15 | - | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.10 |

| Dominant tree species | Type of assortments (proportion) | ||||

| Packing case timber | Veneer logs | Saw logs | Paper wood | Firewood | |

| Pine | 0.05 | - | 0.55 | 0.35 | 0.05 |

| Spruce | 0.20 | - | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.15 |

| Birch | 0.10 | 0.25 | - | 0.60 | 0.05 |

| Aspen | 0.35 | - | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.40 |

| Black alder | 0.05 | - | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.15 |

| Grey alder | 0.60 | - | - | - | 0.40 |

| Other species | 0.15 | - | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.10 |

| Dominant tree species | Price (EUR/m3) | ||||

| Packing case timber | Veneer logs | Saw logs | Paper wood | Firewood | |

| Pine | 73 | - | 95 | 85 | 42 |

| Spruce | 73 | - | 90 | 76 | 42 |

| Birch | 61 | 127 | 115 | 90 | 42 |

| Aspen | 61 | - | 85 | 68 | 42 |

| Black alder | 61 | - | 78 | 62 | 42 |

| Grey alder | 61 | - | - | - | 42 |

| Other species | 61 | - | 140 | 62 | 42 |

Appendix A4

| Dominant tree species | Forest type | Costs (EUR/ha) | |||||||||

| Maintenance of amelioration systems | Soil preparation | Seedlings | Planting | Forest protection | Forest replenishment | Tending | Young stand tending | Underbrush tending | TOTAL | ||

| Pine | Cladinoso – callunosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Pine | Vacciniosa | - | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 1915 |

| Pine | Myrtillosa | - | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 1915 |

| Pine | Hylocomniosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2086 |

| Pine | Oxalidosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2086 |

| Pine | Aegopodiosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2086 |

| Pine | Callunoso – sphagnosa | - | 242 | 236 | 297 | 136 | 72 | 184 | 184 | 250 | 1601 |

| Pine | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Pine | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Pine | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Pine | Dryopteriosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Pine | Sphagnosa | - | 242 | 236 | 297 | 136 | 72 | 184 | 184 | 250 | 1601 |

| Pine | Caricoso – phragmitosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Pine | Dryopterioso – caricosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Pine | Filipendulosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Pine | Callunosa mel. | 506 | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 2361 |

| Pine | Vacciniosa mel. | 506 | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 2421 |

| Pine | Myrtillosa mel. | 506 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2592 |

| Pine | Mercurialiosa mel. | 506 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2592 |

| Pine | Callunosa turf. mel. | 506 | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 2361 |

| Pine | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 506 | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 2421 |

| Pine | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 506 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2592 |

| Pine | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 506 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2592 |

| Spruce | Cladinoso - callunosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Spruce | Vacciniosa | - | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 1915 |

| Spruce | Myrtillosa | - | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 1915 |

| Spruce | Hylocomniosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2086 |

| Spruce | Oxalidosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2086 |

| Spruce | Aegopodiosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2086 |

| Spruce | Callunoso – sphagnosa | - | 242 | 236 | 297 | 136 | 72 | 184 | 184 | 250 | 1601 |

| Spruce | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Spruce | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Spruce | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Spruce | Dryopteriosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Spruce | Sphagnosa | - | 242 | 236 | 297 | 136 | 72 | 184 | 184 | 250 | 1601 |

| Spruce | Caricoso – phragmitosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Spruce | Dryopterioso – caricosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Spruce | Filipendulosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Spruce | Callunosa mel. | 368 | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 2223 |

| Spruce | Vacciniosa mel. | 368 | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 2283 |

| Spruce | Myrtillosa mel. | 368 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2454 |

| Spruce | Mercurialiosa mel. | 368 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2454 |

| Spruce | Callunosa turf. mel. | 368 | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 2223 |

| Spruce | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 368 | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 2283 |

| Spruce | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 368 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2454 |

| Spruce | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 368 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2454 |

| Birch | Cladinoso - callunosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Birch | Vacciniosa | - | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 1915 |

| Birch | Myrtillosa | - | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 1915 |

| Birch | Hylocomniosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2086 |

| Birch | Oxalidosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2086 |

| Birch | Aegopodiosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2086 |

| Birch | Callunoso – sphagnosa | - | 242 | 236 | 297 | 136 | 72 | 184 | 184 | 250 | 1601 |

| Birch | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Birch | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Birch | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Birch | Dryopteriosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Birch | Sphagnosa | - | 242 | 236 | 297 | 136 | 72 | 184 | 184 | 250 | 1601 |

| Birch | Caricoso – phragmitosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Birch | Dryopterioso – caricosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Birch | Filipendulosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Birch | Callunosa mel. | 276 | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 2131 |

| Birch | Vacciniosa mel. | 276 | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 2191 |

| Birch | Myrtillosa mel. | 276 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2362 |

| Birch | Mercurialiosa mel. | 276 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2362 |

| Birch | Callunosa turf. mel. | 276 | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 2131 |

| Birch | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 276 | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 2191 |

| Birch | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 276 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2362 |

| Birch | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 276 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2362 |

| Aspen | Cladinoso - callunosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Aspen | Vacciniosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 260 | 292 | 250 | 802 |

| Aspen | Myrtillosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 260 | 292 | 250 | 802 |

| Aspen | Hylocomniosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 814 |

| Aspen | Oxalidosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 814 |

| Aspen | Aegopodiosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 814 |

| Aspen | Callunoso – sphagnosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 184 | 184 | 250 | 618 |

| Aspen | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Aspen | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Aspen | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Aspen | Dryopteriosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Aspen | Sphagnosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 184 | 184 | 250 | 618 |

| Aspen | Caricoso – phragmitosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Aspen | Dryopterioso – caricosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Aspen | Filipendulosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Aspen | Callunosa mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 875 |

| Aspen | Vacciniosa mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 260 | 292 | 250 | 986 |

| Aspen | Myrtillosa mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 998 |

| Aspen | Mercurialiosa mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 998 |

| Aspen | Callunosa turf. mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 875 |

| Aspen | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 260 | 292 | 250 | 986 |

| Aspen | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 998 |

| Aspen | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 184 | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 998 |

| Black alder | Cladinoso - callunosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | - | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1719 |

| Black alder | Vacciniosa | - | 239 | 447 | 188 | - | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 1779 |

| Black alder | Myrtillosa | - | 239 | 447 | 188 | - | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 1779 |

| Black alder | Hylocomniosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | - | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 1950 |

| Black alder | Oxalidosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | - | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 1950 |

| Black alder | Aegopodiosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | - | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 1950 |

| Black alder | Callunoso – sphagnosa | - | 242 | 236 | 297 | - | 72 | 184 | 184 | 250 | 1465 |

| Black alder | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | - | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1719 |

| Black alder | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | - | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1719 |

| Black alder | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | - | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1719 |

| Black alder | Dryopteriosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | - | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1719 |

| Black alder | Sphagnosa | - | 242 | 236 | 297 | - | 72 | 184 | 184 | 250 | 1465 |

| Black alder | Caricoso – phragmitosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | - | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1719 |

| Black alder | Dryopterioso – caricosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | - | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1719 |

| Black alder | Filipendulosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | - | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1719 |

| Black alder | Callunosa mel. | 322 | 288 | 404 | 232 | - | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 2041 |

| Black alder | Vacciniosa mel. | 322 | 239 | 447 | 188 | - | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 2101 |

| Black alder | Myrtillosa mel. | 322 | 282 | 479 | 261 | - | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2272 |

| Black alder | Mercurialiosa mel. | 322 | 282 | 479 | 261 | - | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2272 |

| Black alder | Callunosa turf. mel. | 322 | 288 | 404 | 232 | - | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 2041 |

| Black alder | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 322 | 239 | 447 | 188 | - | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 2101 |

| Black alder | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 322 | 282 | 479 | 261 | - | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2272 |

| Black alder | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 322 | 282 | 479 | 261 | - | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2272 |

| Grey alder | Cladinoso - callunosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Grey alder | Vacciniosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 260 | 292 | 250 | 802 |

| Grey alder | Myrtillosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 260 | 292 | 250 | 802 |

| Grey alder | Hylocomniosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 814 |

| Grey alder | Oxalidosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 814 |

| Grey alder | Aegopodiosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 814 |

| Grey alder | Callunoso – sphagnosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 184 | 184 | 250 | 618 |

| Grey alder | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Grey alder | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Grey alder | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Grey alder | Dryopteriosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Grey alder | Sphagnosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 184 | 184 | 250 | 618 |

| Grey alder | Caricoso – phragmitosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Grey alder | Dryopterioso – caricosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Grey alder | Filipendulosa | - | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 691 |

| Grey alder | Callunosa mel. | 138 | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 829 |

| Grey alder | Vacciniosa mel. | 138 | - | - | - | - | - | 260 | 292 | 250 | 940 |

| Grey alder | Myrtillosa mel. | 138 | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 952 |

| Grey alder | Mercurialiosa mel. | 138 | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 952 |

| Grey alder | Callunosa turf. mel. | 138 | - | - | - | - | - | 217 | 224 | 250 | 829 |

| Grey alder | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 138 | - | - | - | - | - | 260 | 292 | 250 | 940 |

| Grey alder | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 138 | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 952 |

| Grey alder | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 138 | - | - | - | - | - | 268 | 296 | 250 | 952 |

| Other species | Cladinoso - callunosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Other species | Vacciniosa | - | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 1915 |

| Other species | Myrtillosa | - | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 1915 |

| Other species | Hylocomniosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2086 |

| Other species | Oxalidosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2086 |

| Other species | Aegopodiosa | - | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2086 |

| Other species | Callunoso – sphagnosa | - | 242 | 236 | 297 | 136 | 72 | 184 | 184 | 250 | 1601 |

| Other species | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Other species | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Other species | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Other species | Dryopteriosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Other species | Sphagnosa | - | 242 | 236 | 297 | 136 | 72 | 184 | 184 | 250 | 1601 |

| Other species | Caricoso – phragmitosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Other species | Dryopterioso – caricosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Other species | Filipendulosa | - | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 1855 |

| Other species | Callunosa mel. | 368 | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 2223 |

| Other species | Vacciniosa mel. | 368 | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 2283 |

| Other species | Myrtillosa mel. | 368 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2454 |

| Other species | Mercurialiosa mel. | 368 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2454 |

| Other species | Callunosa turf. mel. | 368 | 288 | 404 | 232 | 136 | 104 | 217 | 224 | 250 | 2223 |

| Other species | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 368 | 239 | 447 | 188 | 136 | 103 | 260 | 292 | 250 | 2283 |

| Other species | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 368 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2454 |

| Other species | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 368 | 282 | 479 | 261 | 136 | 114 | 268 | 296 | 250 | 2454 |

Appendix A5

| Harvesting and transportation | Costs (EUR/m3) |

| Thinning | 14.06 |

| Final felling | 9.39 |

| Transportation in thinning | 18.86 |

| Transportation in final felling | 16.27 |

| Dominant tree species | Forest type | Costs (EUR/ha) | |||

| Thinning | Final felling | Transportation | Total | ||

| Pine | Cladinoso – callunosa | 1 219 | 2 211 | 5 465 | 8 895 |

| Pine | Vacciniosa | 1 537 | 2 787 | 6 891 | 11 215 |

| Pine | Myrtillosa | 1 934 | 3 508 | 8 673 | 14 116 |

| Pine | Hylocomniosa | 2 384 | 4 325 | 10 693 | 17 403 |

| Pine | Oxalidosa | 2 212 | 4 013 | 9 921 | 16 146 |

| Pine | Aegopodiosa | 775 | 1 406 | 3 475 | 5 656 |

| Pine | Callunoso – sphagnosa | 1 172 | 2 127 | 5 257 | 8 556 |

| Pine | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | 1 676 | 3 040 | 7 515 | 12 230 |

| Pine | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | 2 067 | 3 749 | 9 267 | 15 082 |

| Pine | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | 2 086 | 3 785 | 9 356 | 15 227 |

| Pine | Dryopteriosa | 1 782 | 3 232 | 7 990 | 13 004 |

| Pine | Sphagnosa | 987 | 1 790 | 4 426 | 7 203 |

| Pine | Caricoso – phragmitosa | 1 331 | 2 415 | 5 970 | 9 717 |

| Pine | Dryopterioso – caricosa | 1 696 | 3 076 | 7 604 | 12 375 |

| Pine | Filipendulosa | 1 729 | 3 136 | 7 752 | 12 617 |

| Pine | Callunosa mel. | 1 729 | 3 136 | 7 752 | 13 123 |

| Pine | Vacciniosa mel. | 2 080 | 3 773 | 9 327 | 15 685 |

| Pine | Myrtillosa mel. | 2 252 | 4 085 | 10 099 | 16 942 |

| Pine | Mercurialiosa mel. | 2 186 | 3 965 | 9 802 | 16 459 |

| Pine | Callunosa turf. mel. | 1 219 | 2 211 | 5 465 | 9 401 |

| Pine | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 1 530 | 2 775 | 6 861 | 11 673 |

| Pine | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 1 682 | 3 052 | 7 544 | 12 785 |

| Pine | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 1 788 | 3 244 | 8 020 | 13 558 |

| Spruce | Cladinoso - callunosa | 4 171 | 5 503 | 15 130 | 24 804 |

| Spruce | Vacciniosa | 3 133 | 4 133 | 11 364 | 18 630 |

| Spruce | Myrtillosa | 3 388 | 4 469 | 12 289 | 20 146 |

| Spruce | Hylocomniosa | 3 015 | 3 977 | 10 934 | 17 926 |

| Spruce | Oxalidosa | 3 452 | 4 554 | 12 520 | 20 525 |

| Spruce | Aegopodiosa | 3 461 | 4 566 | 12 553 | 20 580 |

| Spruce | Callunoso – sphagnosa | 2 778 | 3 664 | 10 076 | 16 518 |

| Spruce | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | 3 106 | 4 097 | 11 265 | 18 467 |

| Spruce | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | 3 015 | 3 977 | 10 934 | 17 926 |

| Spruce | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | 3 142 | 4 145 | 11 397 | 18 684 |

| Spruce | Dryopteriosa | 3 270 | 4 313 | 11 859 | 19 442 |

| Spruce | Sphagnosa | 1 949 | 2 571 | 7 069 | 11 590 |

| Spruce | Caricoso – phragmitosa | 2 477 | 3 268 | 8 985 | 14 731 |

| Spruce | Dryopterioso – caricosa | 2 687 | 3 544 | 9 745 | 15 976 |

| Spruce | Filipendulosa | 2 942 | 3 881 | 10 670 | 17 493 |

| Spruce | Callunosa mel. | 3 743 | 4 938 | 13 577 | 22 626 |

| Spruce | Vacciniosa mel. | 3 379 | 4 457 | 12 256 | 20 460 |

| Spruce | Myrtillosa mel. | 3 315 | 4 373 | 12 025 | 20 081 |

| Spruce | Mercurialiosa mel. | 3 342 | 4 409 | 12 124 | 20 243 |

| Spruce | Callunosa turf. mel. | 2 960 | 3 905 | 10 736 | 17 969 |

| Spruce | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 2 823 | 3 725 | 10 241 | 17 157 |

| Spruce | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 2 996 | 3 953 | 10 868 | 18 186 |

| Spruce | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 3 097 | 4 085 | 11 232 | 18 781 |

| Birch | Cladinoso - callunosa | 988 | 2 199 | 5 134 | 8 321 |

| Birch | Vacciniosa | 1 258 | 2 799 | 6 537 | 10 594 |

| Birch | Myrtillosa | 1 646 | 3 664 | 8 557 | 13 868 |

| Birch | Hylocomniosa | 1 884 | 4 193 | 9 792 | 15 869 |

| Birch | Oxalidosa | 1 916 | 4 265 | 9 960 | 16 141 |

| Birch | Aegopodiosa | 1 695 | 3 773 | 8 810 | 14 277 |

| Birch | Callunoso – sphagnosa | 685 | 1 526 | 3 563 | 5 775 |

| Birch | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | 1 171 | 2 607 | 6 088 | 9 867 |

| Birch | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | 1 544 | 3 436 | 8 024 | 13 004 |

| Birch | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | 1 603 | 3 568 | 8 333 | 13 504 |

| Birch | Dryopteriosa | 1 409 | 3 136 | 7 323 | 11 867 |

| Birch | Sphagnosa | 664 | 1 478 | 3 451 | 5 593 |

| Birch | Caricoso – phragmitosa | 939 | 2 091 | 4 882 | 7 912 |

| Birch | Dryopterioso – caricosa | 1 106 | 2 463 | 5 752 | 9 321 |

| Birch | Filipendulosa | 1 306 | 2 908 | 6 790 | 11 003 |

| Birch | Callunosa mel. | 1 128 | 2 511 | 5 864 | 9 779 |

| Birch | Vacciniosa mel. | 1 468 | 3 268 | 7 632 | 12 644 |

| Birch | Myrtillosa mel. | 1 662 | 3 701 | 8 642 | 14 280 |

| Birch | Mercurialiosa mel. | 1 684 | 3 749 | 8 754 | 14 462 |

| Birch | Callunosa turf. mel. | 923 | 2 055 | 4 798 | 8 051 |

| Birch | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 1 058 | 2 355 | 5 499 | 9 188 |

| Birch | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 1 506 | 3 352 | 7 828 | 12 962 |

| Birch | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 1 446 | 3 220 | 7 519 | 12 462 |

| Aspen | Cladinoso - callunosa | 2 435 | 4 337 | 10 782 | 17 555 |

| Aspen | Vacciniosa | 1 815 | 3 232 | 8 034 | 13 081 |

| Aspen | Myrtillosa | 1 909 | 3 400 | 8 452 | 13762 |

| Aspen | Hylocomniosa | 2 273 | 4 049 | 10 065 | 16 388 |

| Aspen | Oxalidosa | 2 220 | 3 953 | 9 826 | 15 999 |

| Aspen | Aegopodiosa | 1 788 | 3 184 | 7 915 | 12 886 |

| Aspen | Callunoso – sphagnosa | 1 848 | 3 292 | 8 184 | 13 324 |

| Aspen | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | 1 916 | 3 412 | 8 482 | 13 810 |

| Aspen | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | 1 943 | 3 460 | 8 602 | 14 005 |

| Aspen | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | 2 091 | 3 725 | 9 259 | 15 075 |

| Aspen | Dryopteriosa | 1 666 | 2 968 | 7 377 | 12 011 |

| Aspen | Sphagnosa | 1 504 | 2 679 | 6 660 | 10 844 |

| Aspen | Caricoso – phragmitosa | 1 538 | 2 739 | 6 810 | 11 087 |

| Aspen | Dryopterioso – caricosa | 1 747 | 3 112 | 7 736 | 12 595 |

| Aspen | Filipendulosa | 1 606 | 2 859 | 7 108 | 11 573 |

| Aspen | Callunosa mel. | 1 781 | 3 172 | 7 885 | 13 022 |

| Aspen | Vacciniosa mel. | 1 815 | 3 232 | 8 034 | 13 265 |

| Aspen | Myrtillosa mel. | 2 226 | 3 965 | 9 856 | 16 231 |

| Aspen | Mercurialiosa mel. | 2 139 | 3 809 | 9 468 | 15 599 |

| Aspen | Callunosa turf. mel. | 1 768 | 3 148 | 7 825 | 12 925 |

| Aspen | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 1 511 | 2 691 | 6 690 | 11 077 |

| Aspen | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 2 341 | 4 169 | 10 364 | 17 058 |

| Aspen | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 2 220 | 3 953 | 9 826 | 16 183 |

| Black alder | Cladinoso - callunosa | 1 452 | 3 232 | 7 547 | 12 231 |

| Black alder | Vacciniosa | 1 225 | 2 727 | 6 369 | 10 321 |

| Black alder | Myrtillosa | 1 641 | 3 652 | 8 529 | 13 823 |

| Black alder | Hylocomniosa | 1 635 | 3 640 | 8 501 | 13 777 |

| Black alder | Oxalidosa | 2 013 | 4 481 | 10 465 | 16 960 |

| Black alder | Aegopodiosa | 1 743 | 3 881 | 9 063 | 14 686 |

| Black alder | Callunoso – sphagnosa | 1 554 | 3 460 | 8 080 | 13 095 |

| Black alder | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | 1 452 | 3 232 | 7 547 | 12 231 |

| Black alder | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | 1 614 | 3 592 | 8 389 | 13 595 |

| Black alder | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | 1 722 | 3 833 | 8 950 | 14 505 |

| Black alder | Dryopteriosa | 1 592 | 3 544 | 8 277 | 13 413 |

| Black alder | Sphagnosa | 1 139 | 2 535 | 5 920 | 9 594 |

| Black alder | Caricoso – phragmitosa | 1 279 | 2 847 | 6 650 | 10 776 |

| Black alder | Dryopterioso – caricosa | 1 376 | 3 064 | 7 155 | 11 595 |

| Black alder | Filipendulosa | 1 446 | 3 220 | 7 519 | 12 186 |

| Black alder | Callunosa mel. | 1 365 | 3 040 | 7 098 | 11 826 |

| Black alder | Vacciniosa mel. | 1 603 | 3 568 | 8 333 | 13 826 |

| Black alder | Myrtillosa mel. | 1 689 | 3 761 | 8 782 | 14 554 |

| Black alder | Mercurialiosa mel. | 1 759 | 3 917 | 9 147 | 15 145 |

| Black alder | Callunosa turf. mel. | 1 311 | 2 920 | 6 818 | 11 371 |

| Black alder | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 1 349 | 3 004 | 7 014 | 11 689 |

| Black alder | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 1 484 | 3 304 | 7 716 | 12 826 |

| Black alder | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 1 608 | 3 580 | 8 361 | 13 872 |

| Grey alder | Cladinoso - callunosa | 727 | 2 427 | 5 180 | 8 334 |

| Grey alder | Vacciniosa | 547 | 1 826 | 3 898 | 6 271 |

| Grey alder | Myrtillosa | 450 | 1 502 | 3 206 | 5 157 |

| Grey alder | Hylocomniosa | 626 | 2 091 | 4 462 | 7 179 |

| Grey alder | Oxalidosa | 633 | 2 115 | 4 513 | 7 261 |

| Grey alder | Aegopodiosa | 590 | 1 970 | 4 206 | 6 766 |

| Grey alder | Callunoso – sphagnosa | 450 | 1 502 | 3 206 | 5 157 |

| Grey alder | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | 612 | 2 042 | 4 359 | 7 014 |

| Grey alder | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | 594 | 1 982 | 4 231 | 6 807 |

| Grey alder | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | 612 | 2 042 | 4 359 | 7 014 |

| Grey alder | Dryopteriosa | 576 | 1 922 | 4 103 | 6 601 |

| Grey alder | Sphagnosa | 414 | 1 382 | 2 949 | 4 745 |

| Grey alder | Caricoso – phragmitosa | 446 | 1 490 | 3 180 | 5 116 |

| Grey alder | Dryopterioso – caricosa | 504 | 1 682 | 3 590 | 5 776 |

| Grey alder | Filipendulosa | 536 | 1 790 | 3 821 | 6 147 |

| Grey alder | Callunosa mel. | 856 | 2 859 | 6 103 | 9 957 |

| Grey alder | Vacciniosa mel. | 561 | 1 874 | 4 000 | 6 574 |

| Grey alder | Myrtillosa mel. | 622 | 2 079 | 4 436 | 7 275 |

| Grey alder | Mercurialiosa mel. | 633 | 2 115 | 4 513 | 7 399 |

| Grey alder | Callunosa turf. mel. | 608 | 2 030 | 4 334 | 7 110 |

| Grey alder | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 471 | 1 574 | 3 359 | 5 543 |

| Grey alder | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 673 | 2 247 | 4 795 | 7 853 |

| Grey alder | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 640 | 2 139 | 4 565 | 7 482 |

| Other species | Cladinoso - callunosa | 1 028 | 3 052 | 6 667 | 10 747 |

| Other species | Vacciniosa | 891 | 2 643 | 5 774 | 9 308 |

| Other species | Myrtillosa | 1 028 | 3 052 | 6 667 | 10 747 |

| Other species | Hylocomniosa | 1 178 | 3 496 | 7 638 | 12 312 |

| Other species | Oxalidosa | 1 247 | 3 701 | 8 084 | 13 031 |

| Other species | Aegopodiosa | 1 081 | 3 208 | 7 008 | 11 297 |

| Other species | Callunoso – sphagnosa | 822 | 2 439 | 5 328 | 8 589 |

| Other species | Vaccinioso – sphagnosa | 951 | 2 823 | 6 168 | 9 943 |

| Other species | Myrtilloso – sphagnosa | 1 052 | 3 124 | 6 824 | 11 001 |

| Other species | Myrtilloso – polytrichosa | 1 109 | 3 292 | 7 192 | 11 593 |

| Other species | Dryopteriosa | 976 | 2 896 | 6 326 | 10 197 |

| Other species | Sphagnosa | 680 | 2 018 | 4 410 | 7 108 |

| Other species | Caricoso – phragmitosa | 773 | 2 295 | 5 013 | 8 081 |

| Other species | Dryopterioso – caricosa | 870 | 2 583 | 5 643 | 9 097 |

| Other species | Filipendulosa | 907 | 2 691 | 5 879 | 9 477 |

| Other species | Callunosa mel. | 976 | 2 896 | 6 326 | 10 565 |

| Other species | Vacciniosa mel. | 1 004 | 2 980 | 6 509 | 10 861 |

| Other species | Myrtillosa mel. | 1 137 | 3 376 | 7 376 | 12 257 |

| Other species | Mercurialiosa mel. | 1 146 | 3 400 | 7 428 | 12 342 |

| Other species | Callunosa turf. mel. | 854 | 2 535 | 5 538 | 9 295 |

| Other species | Vacciniosa turf. mel. | 814 | 2 415 | 5 276 | 8 872 |

| Other species | Myrtillosa turf. mel. | 1 101 | 3 268 | 7 139 | 11 876 |

| Other species | Oxalidosa turf. mel. | 1 085 | 3 220 | 7 034 | 11 707 |

Appendix A6

| Dominant tree species | a1 | a2 | a3 | a4 |

| Pine | 3.9049 | -0.4473 | 0.8518 | 0.8571 |

| Spruce | 8.7959 | -0.5371 | 1.0000 | 0.6810 |

| Birch | 9.6997 | -0.4776 | 0.8772 | 0.6097 |

| Black alder | 10.7240 | -0.5133 | 0.8822 | 0.6234 |

| Aspen | 12.4910 | -0.3753 | 1.0000 | 0.4480 |

| Grey alder | 11.5837 | -0.4727 | 1.0000 | 0.4737 |

| Other species | 12.4910 | -0.3753 | 1.0000 | 0.4480 |

Appendix A7

| Dominant tree species | Site index | Maximum standing volume at felling age (m3/ha) |

| Pine | 5 | 214 |

| Pine | 4 | 306 |

| Pine | 3 | 381 |

| Pine | 2 | 453 |

| Pine | 1 | 525 |

| Pine | 0 | 586 |

| Spruce | 5 | 198 |

| Spruce | 4 | 332 |

| Spruce | 3 | 401 |

| Spruce | 2 | 494 |

| Spruce | 1 | 556 |

| Spruce | 0 | 600 |

| Birch | 5 | 200 |

| Birch | 4 | 285 |

| Birch | 3 | 346 |

| Birch | 2 | 392 |

| Birch | 1 | 460 |

| Birch | 0 | 481 |

| Black alder | 5 | 201 |

| Black alder | 4 | 289 |

| Black alder | 3 | 362 |

| Black alder | 2 | 416 |

| Black alder | 1 | 495 |

| Black alder | 0 | 562 |

| Aspen | 5 | 91 |

| Aspen | 4 | 157 |

| Aspen | 3 | 248 |

| Aspen | 2 | 321 |

| Aspen | 1 | 399 |

| Aspen | 0 | 482 |

| Grey alder | 5 | 99 |

| Grey alder | 4 | 138 |

| Grey alder | 3 | 183 |

| Grey alder | 2 | 238 |

| Grey alder | 1 | 284 |

References

- UN. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/423). Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, United Nations, 2019.

- Ferrari, L; Panaite, SA; Bertazzo, A; Visioli, F. Animal- and Plant-Based Protein Sources: A Scoping Review of Human Health Outcomes and Environmental Impact. Nutrients 2022, 14(23), 5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coeffey, A.A.; Lillywhite, R.; Oyebode, O. Meat versus meat alternatives: which is better for the environmentand health? A nutritional and environmental analysis of animal-based products compared with their plant-based alternatives. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2023, 36, 2147–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.C.; Güneralp, B.; Hutyra, L.R. Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109(40), 16083–16088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyfroidt, P., Roy Chowdhury, R., de Bremond, A., Ellis, E.C., Erb, K.-H., Filatova, T., Garrett, R.D., Grove, J.M., Heinimann, A., Kuemmerle, T., Kull, C.A., Lambin, E.F., Landon, Y., le Polain de Waroux, Y., Messerli, P., Müller, D., Nielsen, J.Ø., Peterson, G.D., Rodriguez García, V., Schlüter, M., Turner, B.L., Verburg, P.H., 2018. Middle-range theories of land system change. Global Environmental Change 2018, Volume 53, Pages 52-67. [CrossRef]

- EC. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on binding annual greenhouse gas emission reductions by Member States from 2021 to 2030 for a resilient Energy Union and to meet commitments under the Paris Agreement and amending Regulation No 525/2013 of the European Parliament and the Council on a mechanism for monitoring and reporting greenhouse gas emissions and other information relevant to climate change, COM(2016) 482 final, 2016, Brussels, 20.07.2016, European Commission.

- EC. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, Bringing nature back into our lives, European Commission, Brussels, 20.5.2020 COM(2020) 380 final, 2020.

- EC. Proposal for a Regulation Of The European Parliament And Of The Council on nature restoration, European Commission, Brussels, 22.6.2022 COM(2022) 304 final, 2022/0195 (COD), 2022.

- DAFM. Afforestation Scheme 2023-2027 Document. Forestry Division, Department of Agriculture, Food & the Marine, Ireland, April 2024.

- MITECO. Spanish Forest Strategy 2050 – Spanish Forest Plan 2022-2032. Executive Summary. Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge, 2023.

- PLANAVEG. Brazilian National Plan for Native Vegetation Recovery, Ministry of Environment, 2017.

- MEFCC. National Forest Policy. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, PIB Delhi, 2023.

- Doelman, J.C.; Stehfest, E.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Tabeau, A.; Hof, A.F.; Braakhekke, M.C.; Gernaat, D.E.H.J.; van den Berg, M.; van Zeist, W.J.; Daioglou, V.; van Meijl, H.; Lucas, P.L. Afforestation for climate change mitigation: Potentials, risks and trade-offs. Glob Change Biol. 2019, 26, 1576–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Dang, P.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, Ha.; Zhu, Hu.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, Z. Effects of tree species and soil properties on the composition and diversity of the soil bacterial community following afforestation. Forest Ecology and Management 2018, 427, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kārkliņš, A., Līpenīte, I. Apmežotas lauksaimniecībā izmantojamās zemes augsnes īpašību izpētes rezultāti. Zinātniski praktiskā konference Lauksaimniecības zinātne veiksmīgai saimniekošanai 2013, 21. – 22.02.2013., Jelgava, LLU.

- Nikodemus, O.; Kaupe, D.; Kukuls, I.; Brumelis, G.; Kasparinskis, R.; Dauskane, I.; Treimane, A. Effects of afforestation of agricultural land with grey alder (Alnus incana (L.) Moench) on soil chemical properties, comparing two contrasting soil groups. Forest Ecosystems 2020, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rämö, J.; Tupek, B.; Lehtonen, H.; Mäkipää, R. Towards climate targets with cropland afforestation – effect of subsidies on profitability. Land Use Policy 2023, 124, 106433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, T.A.P.; Monge, J.J.; Dowling, L.J.; Wakelin, S.J.; Gibbs, H.K. Promotion of afforestation in New Zealand’s marginal agricultural lands through payments for environmental services. Ecosystem Services 2020, 46, 101212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, R.; Lowenberg-Deboer, J. Precision Agriculture and Sustainability. Precision Agriculture 2004, 5(4), 359–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Enhancing smart farming through the applications of Agriculture 4.0 technologies. International Journal of Intelligent Networks 2022, 3, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khose, S.B., Dhokale, K.B., Shekhar, S. 2023. The Role of Precision Farming in Sustainable Agriculture: Advancements and Impacts. Agriculture & Food: E-Newsletter 2023, 5:9, E-ISSN: 2581 – 8317.

- Halperin, S.; Castro, A.J.; Quintas-Soriano, C.; Brandt, J.S. Assessing high quality agricultural lands through the ecosystem services lens: Insights from a rapidly urbanizing agricultural region in the western United States. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2023, 349, 108435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, L.C.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Harris, D.; Lyon, C.; Pereira, L.; Ward, C.F.M.; Simelton, E. Adaptation and development pathways for different types of farmers. Environmental Science & Policy 2020, 104, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valujeva, K.; Freed, E.K.; Nipers, A.; Jauhiainen, J.; Schulte, R.P.O. Pathways for governance opportunities: Social network analysis to create targeted and effective policies for agricultural and environmental development. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 325, 116563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardaker, A.; Healey, J. Financial evaluation of afforestation projects - basic steps: Economic aspects of woodland creation for timber production 1. Woodknowledge Wales in association with Bangor University. 2021. Available online: https://research.bangor.ac.uk/portal/files/38418360/forestry_economics_1_final.pdf.

- Evison, D. Estimating annual investment returns from forestry and agriculture in New Zealand. Journal of Forest Economics 2018, 33, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardaker, A. Is forestry really more profitable than upland farming? A historic and present day farm level economic comparison of upland sheep farming and forestry in the UK. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 98–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiesmeier, A.; Zander, P. Can agroforestry compete? A scoping review of the economic performance of agroforestry practices in Europe and North America. Forest Policy and Economics 2023, 150, 102939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSB. Statistical Yearbook of Latvia. Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia, 2023, ISBN 978-9984-06-598-4.

- CSP. Mežsaimniecība 2022. gadā. Informatīvais pārskats 23-018-000, Centrālā statistikas pārvalde (in Latvian), 2023.

- AREI. Latvijas lauku saimniecību uzskaites datu tīkls SUDAT. Agroresursu un ekonomikas institūts (in Latvian), 2021.

- LLKC. Lauksaimniecības bruto segumu aprēķini par 2021. gadu. SIA “Latvijas Lauku konsultāciju un izglītības centrs” (in Latvian), 2021.

- CSP. Purchase prices of agricultural products 2019 - 2021, EUR per ton (excluding VAT) [online]. Official statistics portal, database. [Viewed on January 20th 2025], 2024c. Available: https://stat.gov.lv/lv/statistikas-temas/noz/lauksaimn/tabulas/lac020-lauksaimniecibas-produktu-cenas?themeCode=LA.

- CSP. Sown area, total crop production, yield of agricultural crops 2000 – 2024. [online]. Official statistics portal, database. [Viewed on January 27th 2025], 2024d. Available: https://data.stat.gov.lv/pxweb/en/OSP_PUB/START__NOZ__LA__LAG/LAG020/.

- Boruks, A., Krūzmētra, M., Rivža, B., Rivža, P., Stokmane, I. Dabas un sociāli ekonomisko apstākļu mijiedarbība un ietekme uz Latvijas lauku attīstību. Jelgava, Latvijas Lauksaimniecības universitāte, 2000.

- Bardulis, A.; Ivanovs, J.; Bardule, A.; Lazdina, D.; Purvina, D.; Butlers, A.; Lazdins, A. Assessment of Agricultural Areas Suitable for Agroforestry in Latvia. Land 2022, 11(10), 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSP. Total crop production of agricultural crops 2020 - 2024, thousand tons [online]. Official statistics portal, database. [Viewed on January 20th 2025], 2024a. Available: https://stat.gov.lv/en/statistics-themes/business-sectors/agriculture/tables/lag020-sown-area-total-crop-production-yield.

- CSP. Hourly labour costs by kind of activity 2019 - 2021, EUR [online]. Official statistics portal, database. [Viewed on January 20th 2025], 2024e. Available: https://stat.gov.lv/lv/statistikas-temas/darbs/darbaspeka-izmaksas/tabulas/dis010-vienas-stundas-darbaspeka-izmaksas-pa.

- Veipane, U. D.; Pilvere, I.; Lilmets, J.; Bilande, K.; Nipers, A. Land Use and Production Practices Shape Unequal Labour Demand in Agriculture and Forestry. Land 2025, 14(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Gross value added and income by detailed industry (NACE Rev. 2): nama_10_a64 [Data set]. European Commission. Retrieved December 10, 2025, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/nama_10_a64/default/table?lang=en.

- Grege-Staltmane, E.; Tuherm, H. Importance of Discounting Rate in Latvian Forest Valuation. Baltic Forestry 2010, 16(2), 303–311. Available online: https://balticforestry.lammc.lt/bf/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&catid=12&id=35&Itemid=110.

- Chudy, R. P.; Cubbage, F. W. Research trends: Forest investments as a financial asset class. Forest policy and economics 2020, 119, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeima. Meža likums. LR likums. Latvijas Vēstnesis, 98/99, 16.03.2000. Rīga: Latvijas Republikas Saeima. Pieejams: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/2825 (in Latvian).

- Pilvere, I.; Sisenis, L.; Nipers, A. Dažādu zemes apsaimniekošanas modeļu sociāli ekonomiskais novērtējums; 2015; pp. 11–33. (in Latvian) [Google Scholar]

- CSP. Average purchase price of wood 2024, EUR per m3 (excluding VAT) [online]. Official statistics portal, database. [Viewed on January 20th 2025], 2024f. Available: https://stat.gov.lv/en/statistics-themes/business-sectors/forestry/tables/mei020-average-purchase-prices-wood-eurm3.

- LVM. Kopšanas ciršu rokasgrāmata. AS “Latvijas valsts meži”, 2012, 105 lpp. (in Latvian).

- CSP. Forest regeneration and cultivation expenses 2023, EUR per ha (excluding VAT) [online]. Official statistics portal, database. [Viewed on January 20th 2025], 2024b. Available: https://stat.gov.lv/en/statistics-themes/business-sectors/forestry/tables/mep010-forest-regeneration-and-cultivation.

- Columba. Mežsaimniecisko darbu pakalpojumu cenas [tiešsaiste]. SIA ‘Columba” mājaslapa [skatīts 2024.g. 24.jūl.]. Pieejams: http://www.columba.lv/lv/me%C5%BEsaimniec%C4%ABbas-pakalpojumi-78417/me%C5%BEsaimniec%C4%ABbas-pakalpojumu-cenas-87043 (in Latvian).

- Agrimatco. Kaitēkļiem, ērcēm, gliemežiem, atbaidītāji PROF [tiešsaiste]. Agrimatco Latvia mājaslapa [skatīts 2024.g. 24.jūl.], 2023. Pieejams: https://agrimatco.lv/produkti/augu-aizsardziba/insekticidi-akaricidi/1/205/cervacol-extra-0337-5kg (in Latvian).

- Nipers, A. Project of Refinement of the Functional Land Use Model, funded by the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Latvia and the Rural Support Service of the Republic of Latvia’s, No. 10.9.1-11/25/1536-e. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- CSP. Average expenses of forest exploitation (EUR/m³ (excluding VAT)) [online]. Official statistics portal, database. [Viewed on January 20th 2025], 2024g. Available: https://stat.gov.lv/en/statistics-themes/business-sectors/forestry/tables/mei010-average-expenses-forest-exploitation.

- VMD. State Register of Forests [online]. State Forestry Service. [Viewed on January 20th 2025], 2024. Available: https://www.vmd.gov.lv/lv/meza-valsts-registrs.

- Donis, J. Meža apsaimniekošanu un izmantošanu regulējošajos normatīvajos aktos izmantoto mežu raksturojošo rādītāju precizēšana. Pārskats par Meža attīstības fonda pētījumu, Latvijas Valsts mežzinātnes institūts „Silava”, 2019, 33. lpp. Pieejams: https://www.lbtu.lv/lv/projekti/apstiprinatie-projekti/2019/meza-apsaimniekosanu-un-izmantosanu-regulejosajos-normativajos (in Latvian).

- Roilo, S.; Paulus, A.; Alarcón-Segura, V.; Kock, L.; Beckmann, M.; Klein, N.; Cord, A. F. Quantifying agricultural land-use intensity for spatial biodiversity modelling: Implications of different metrics and spatial aggregation methods. Landscape Ecology 2024, 39(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubowski, R.N.; Plantinga, A.J.; Stavins, R.N. Land-use change and carbon sinks: Econometric estimation of the carbon sequestration supply function. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2006, 51(Issue 2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, T. A Literature Review on the Net Present Value (NPV) Valuation Method. Conference: 2022 2nd International Conference on Enterprise Management and Economic Development (ICEMED 2022), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nipers, A.; Pilvere, I.; Sisenis, L.; Feldmanis, R. Support Measures of the Rural Development Programme for the Forest Industry In Latvia. 20th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM 2020, 20:3.1, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipers, A.; Pilvere, I. Age Structure of Farm Owners and Managers: Problems and the Solutions Thereto in Latvia. Rural Sustainability Research 2020, 44(Issue 339), 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagiliūtė, R.; Kazanavičiūtė, V. Impact of Land-Use Changes on Climate Change Mitigation Goals: The Case of Lithuania. Land 2024, 13(2), 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Jiao, J.; Jia, Y.; Wang, D. Influence of Afforestation on the Species Diversity of the Soil Seed Bank and Understory Vegetation in the Hill-Gullied Loess Plateau, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14(10), 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, C.; Jiménez, M.; Fernández-Ondoño, E.; Navarro, F.B. Effects of Afforestation on Plant Diversity and Soil Quality in Semiarid SE Spain. Forests 2021, 12(12), 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.; Champan, D. Impacts of afforestation on groundwater resources and quality. Hydrogeology Journal 2001, 9, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A.A.; Fox, J. Giving credit to reforestation for water quality benefits. PLoS ONE 2019, 14(6), e0217756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahai, M.K.; Kabba, V.T.S.; Mansaray, L.R. Impacts of land-use and land-cover change on rural livelihoods: Evidence from eastern Sierra Leone. Applied Geography 2022, 147, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, C.; Valdiviezo, R.; Hernández, H.; Tafur, V.; Eche, D.; Jácome, E. Off-Farm Employment, Forest Clearing and Natural Resource Use: Evidence from the Ecuadorian Amazon. Sustainability 2020, 12(11), 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perunová, M.; Zimmermannová, M. Analysis of forestry employment within the bioeconomy labour market in the Czech Republic. Journal of Forest Science 2022, 68((10)), 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Farms and farmland in the European Union – statistics. Eurostat Statistics Explained, 2022. ISSN 2443-8219.

- Cheng, A.T.; Sims, K.R.E.; Yi, Y. Economic development and conservation impacts of China’s nature reserves. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2023, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. Summary of CAP Strategic Plans for 2023-2027: joint effort and collective ambition. European Commission, Brussels, 23.11.2023, COM(2023) 707 final.

- EU SCAR AKI. Preparing for Future AKIS in Europe. Standing Committee on Agricultural Research (SCAR), 4 th Report of the Strategic Working Group on Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems (AKIS), Brussels, European Commission, 2019.

- Dumanski, J.; Pieri, C. Land quality indicators: research plan. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2000, 81(2), 93–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Farm Accountancy Data Network Public Database, 2019. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/farm-accountancy-data-network-public-database?locale=en (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Bartkowski, B.; Beckmann, M.; Drechsler, M.; Kaim, A.; Liebelt, V.; Müller, B.; Witing, F.; Strauch, M. Aligning Agent-Based Modeling with Multi-Objective Land-Use Allocation: Identification of Policy Gaps and Feasible Pathways to Biophysically Optimal Landscapes. Front. Environ. Sci. 2020, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyfroidt, P., de Bremond, A., Ryan, C.M., Archer, E., Aspinall, R., Chhabra, A., Camara, G., Corbera, E., DeFries, R., Díaz, S., et al. Ten facts about land systems for sustainability, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, U.S.A. 119 (7) e2109217118. [CrossRef]

- Valujeva, K.; Debernardini, M.; Freed, E.K.; Nipers, A.; Schulte, R.P.O. Abandoned farmland: Past failures or future opportunities for Europe’s Green Deal? A Baltic case-study. Environmental Science & Policy 2022, 128, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merckx, T.; Pereira, H. M. Reshaping agri-environmental subsidies: From marginal farming to large-scale rewilding. Basic and Applied Ecology 2015, 16(2), 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilande, K.; Zeglova, K.; Donis, J.; Nipers, A. Assesing Landscape-Level Biodiversity Under Policy Scenarios: Integrating Spatial and Land Use Data. Earth 2025, 6(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).