1. Introduction

Red Angico (

Anadenanthera colubrina) and Mahogany (

Swietenia macrophylla) are two iconic hardwood species native to the tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas, with a particularly strong presence in Brazil. According to Delices et al [

1,

2], Red Angico, known locally as Angico Vermelho, is a native species, though not endemic to the country. Its confirmed geographic distribution includes the Northeast, Central-West, and Southeast regions of Brazil. The species occurs across several phytogeographic domains, including the Caatinga, Cerrado (Central Brazilian Savanna), and Atlantic Rainforest. It thrives in diverse vegetation types such as strict Caatinga, broad Cerrado, seasonally semi-deciduous forests, and ombrophyllous (tropical rain) forests. Red Angico is a tree valued for its dense, durable wood and medicinal properties, often used in traditional remedies [

1]. Mahogany, or big-leaf Mahogany (

Swietenia macrophylla), considered to be the original Mahogany species, is found in clustered formations along seasonal streams within transitional evergreen forests in southeastern Pará, Brazil [

3]. This species is one of the most prized tropical timbers in the world, renowned for its rich reddish-brown hue and fine grain, making it a staple in high-end furniture and musical instruments. In Brazil, both species play important ecological roles within the Atlantic Forest and Amazon biomes and are subject to conservation efforts due to historical overharvesting.

Chemically, Mahogany (

Swietenia macrophylla) seems to differ a lot between sites. Wood from Bangladesh showed relatively high contents of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, with values of 57.90%, 11.20%, and 28.50%, respectively [

4]. In contrast, Mahogany sawdust from Indonesia was dominated by lignin and cellulose, each present at around 35.40% and 35.38% by weight, while hemicellulose accounted for 28.94% [

5]. Another study from Indonesia reported cellulose content of 47.26%, hemicellulose at 27.37%, and lignin at 25.82% [

6]. Rajagopalan et al. [

7] reported that xylan extracted from Mahogany wood was predominantly composed of xylose (86.3%), with minor amounts of glucose (2%), mannose (1.8%), galactose (<1%), and arabinose (<1%), along with 7.5% uronic acid. Asmara et al. [

8] identified various phytochemicals in Mahogany wood, including flavonoids, tannins (such as gallic acid, ellagic acid, catechin, and epicatechin), and other phenolic compounds, which contribute to its antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties.

Regarding extractive content, several studies have highlighted its variation in Mahogany depending on tree age, wood type, position along the stem, and the solvent used, as reported by Arisandi et al. [

9] who determined extractives in several parts of young Mahogany trees aged five years, where extractive levels varied significantly. For n-hexane, values ranged from 1.29 ± 0.11% in the top sapwood to 2.39 ± 0.16% in the bottom heartwood. Methanol extractives showed the widest variation, from 5.19 ± 2.38% in the top sapwood to 7.81 ± 1.33% in the bottom heartwood. Hot water extractives ranged from 2.42 ± 0.86% in the top sapwood to 3.52 ± 0.62% in the bottom heartwood. Overall, total extractive content was lowest in the top sapwood (8.90 ± 2.29%) and highest in the bottom heartwood (13.7 ± 1.80%), indicating that heartwood and lower sections of the stem tend to contain more extractable compounds than the upper parts and sapwood. Additional studies support this variability. Batubara et al. [

10] and da Silva et al. [

11] reported extractive contents in Swietenia species ranging from 4.01% to 14.83%, depending on geographical region and solvent type. Taylor et al. [

12] observed even higher extractive yields, up to 28.1%, in Mahogany wood from Central and South America. In contrast, lower values, below 4%, were reported by Rutiaga Quiñones et al. [

13] and also Gala et al. [

14] in S. mahagoni from Indonesia. These differences are primarily attributed to factors such as species, environmental conditions, tree part, age, and the type of solvent used for extraction.

The chemical composition of Red Angico (

Anadenanthera colubrina) is not well documented, as relatively few studies have investigated this species in detail. Existing data reveal variability depending on geographic origin and analytical methods. Lignin content in Red Angico samples from different regions of Brazil ranged between 16.37% and 19.19% [

15] In contrast, wood from the Northeast Plants Association (APNE), derived from forest management areas located in rural settlements in the state of Pernambuco, showed a higher insoluble lignin content of approximately 24.89%, alongside a total extractives content of 20.68% and ash content of 1.78% [

16]

A more detailed compositional analysis by Villanueva et al. [

8] provides a comprehensive breakdown of Red Angico’s chemical constituents. Their results indicate that glucan is the most abundant component at 43.3%, which implies a high cellulose content. The hemicellulose-associated sugars, xylan (15.6%), arabinan (2.1%), mannan (1.4%), and galactan (2.1%) together account for approximately 21.2%, underscoring the presence of a substantial hemicellulose fraction. Lignin, comprising Klason lignin (18.8%) and acid-soluble lignin (1.2%), totals 20.0%, which aligns with values typically observed in hardwood species. The ash content is relatively low at 1.4%, indicating a minimal inorganic residue. The sample also contains significant amounts of extractives, including water-soluble extractives (12.6%) and ethanol-soluble extractives (1.7%), likely composed of phenolic compounds and other low-molecular-weight organics [

17]. Therefore, according to Red Angico wood is rich in structural polysaccharides, with an estimated cellulose content of approximately 43% (assuming all glucan is derived from cellulose), and a hemicellulose content near 21%. It is worth noting that the actual hemicellulose content may be slightly higher, as some glucose could originate from hemicellulosic polysaccharides. Furthermore, acetyl groups were not analyzed, which could contribute additional mass to the hemicellulose fraction [

17].

A variety of liquefaction agents have been explored for the conversion of lignocellulosic biomass, with the most common being phenol [

18,

19] typically employed alongside either acid or base catalysts and polyhydric alcohols, usually combined with acid catalysts [

20] represent another widely used class of solvents. Additional liquefaction media include cyclic carbonates [

21], ionic liquids, and dibasic esters, offering alternative pathways depending on the desired end products.

The choice of liquefaction agent directly influences the type of resin produced from the liquefied biomass. Phenol-based liquefaction generally leads to phenolic resins. For instance, Pan et al. [

22] synthesized novolac-type phenolic resins from acid-catalyzed phenol-liquefied wood.

Liquefaction with polyhydric alcohols results in distinct resin types. Kobayashi et al. successfully prepared epoxy resins from wood liquefied with polyhydric alcohols, highlighting the versatility of alcohol-based liquefaction processes for producing various bio-based polymers. Polyalcohol liquefaction is a well-known process to convert solid biomass into a usable liquid that can be used to produce several polymers. Liquefaction involves breaking down biomass under severe conditions using a solvent, through reactions such as hydrolysis, phenolysis, alcoholysis, or glycolysis [

23]. These reactions cleave biopolymers into smaller fragments, though competing condensation reactions can simultaneously lead to the formation of high molecular weight residues[

23].

The most used polyhydric alcohols are polyethylene glycol (PEG), polypropylene glycol (PPG), ethylene glycol and glycerol [

24,

25,

26]. Liquefaction has been applied to a wide range of biomass feedstocks, such as wood [

27], barks [

25,

28], several fruit nuts shells [

29,

30,

31], nut shells from different camelia[

32], scrubs [

33], etc. The extent of liquefaction depends on several factors, with reaction time, temperature, catalyst loading, and solvent-to-biomass ratio being the most critical [

23].

The main pre-treatment before polyurethane production is neutralizing the acid since the excess of acid groups in the liquefied product can adversely affect its properties since carboxyl groups might consume isocyanates and catalyst resulting in an unstable reaction and poor properties end-product[

34].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Red Angico (Anadenanthera colubrina) and Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) wood samples were sourced from managed forest reserves in the southeast region of Brazil. Upon collection, the samples were air-dried to constant weight, ground using a Wiley-type mill (Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, USA), and classified by particle size through standard sieving (Vibratory Sieve Shaker AS 200, Retsch GmbH, Germany) for 30 minutes at 50 rpm. The sieved material was divided into three granulometric fractions: >40 mesh (>0.450 mm), 40–60 mesh (0.250–0.425 mm) and <60 mesh (<0.250 mm). Prior to any analysis, all fractions were oven-dried at 100 °C for 24 hours. Unless stated otherwise, the 40–60 mesh fraction was selected for chemical characterization and liquefaction experiments. All reagents used throughout the procedures were of analytical grade.

2.2. Chemical Characterization

The 40–60 mesh wood fractions of Red Angico and Mahogany were analyzed for their chemical composition, including ash, extractives (organic solvents and water), lignin (acid-insoluble and soluble), α-cellulose, and hemicelluloses. Samples were conditioned by oven-drying at 105 °C for a minimum of 24 hours prior to analysis. All analyses were performed in triplicate according to the Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry (TAPPI) standards.

Ash content was quantified via calcination at 525 °C following the TAPPI T 211 om-93 method [

35]. Sequential Soxhlet extraction was employed for determining extractives, using 150 mL each of dichloromethane, ethanol, and hot distilled water, as described in TAPPI T 204 om-88 [

36]. Each solvent extraction was performed for 6 hours (dichloromethane) and 16 hours (ethanol and water), using 10 g of oven-dried sample per test.

Lignin quantification was carried out using a modified Klason procedure. Initially, 72% H₂SO₄ hydrolysis was conducted at 30 °C for 1 hour in a water bath, followed by secondary hydrolysis with 3% H₂SO₄ at 120 °C in an autoclave for 1 hour. The resulting acid-insoluble residue was filtered through a G2 sintered glass crucible, washed with warm water and acetone, and dried to constant weight at 100 °C. The percentage of Klason lignin was calculated using the following formula:

Soluble lignin content was determined spectrophotometrically by absorbance at 205 nm.

The holocellulose content of Red Angico and Mahogany samples was determined using the sodium chlorite-acetic acid delignification method, adapted from the Wise et al.[

37] procedure. Approximately 2.00 ± 0.01 g of extractive-free, oven-dried wood material (40–60 mesh fraction) was placed in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask. To this, 100 mL of distilled water was added, followed by 0.3 g of sodium chlorite (NaClO₂) and 0.2 mL of glacial acetic acid. The flask was sealed with a loose-fitting stopper and placed in a water bath at 70 °C. Every 1 hour, an additional 0.3 g of sodium chlorite and 0.2 mL of acetic acid were added, and the reaction was allowed to proceed for a total of 4 hours, with occasional swirling to ensure even contact.

Upon completion of the delignification, the mixture was cooled to room temperature. The solid residue was filtered using a G2 sintered glass crucible and washed thoroughly with cold distilled water until the filtrate was neutral (pH ~7). The retained material, composed of both cellulose and hemicelluloses, was then oven-dried at 105 °C until constant weight.

The holocellulose content was calculated based on the dry weight of the residue relative to the initial dry weight of the sample:

All determinations were carried out in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

The α-cellulose content of Red Angico and Mahogany samples was determined following standard alkaline extraction procedures adapted from TAPPI T 429 cm-23 [

38]. For each determination, 1.00 ± 0.01 g of holocellulose was treated with 17.5% sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution at room temperature. The sample was stirred gently in the NaOH solution for 30 minutes, promoting the dissolution of hemicelluloses and β-/γ-cellulose fractions. The suspension was then diluted with distilled water to reduce the NaOH concentration to approximately 8.3% and allowed to stand for 1 hour. The insoluble α-cellulose was filtered using a G2 sintered glass crucible, washed thoroughly with 1% acetic acid followed by multiple rinses with hot distilled water until the filtrate reached neutral pH. The residue was dried in an oven at 105 °C to constant weight.

The α-cellulose content was calculated as:

All measurements were performed in triplicate for accuracy.

Hemicellulose content was estimated by subtracting the values of Holocellulose and α-cellulose.

2.3. Liquefaction

Liquefaction trials were designed to investigate the influence of temperature and reaction time on the solvolysis of Red Angico and Mahogany wood. Experiments were conducted in a 600 mL double-jacketed stainless-steel reactor (Parr Instrument Company, USA) equipped with mechanical stirring and temperature control, heated externally with a thermostatic oil bath. Each liquefaction mixture contained 10 g of dried wood particles (40–60 mesh), 100 mL of a 1:1 (v/v) blend of glycerol (87%) and ethylene glycol as the solvent system, and 3% (w/w) sulfuric acid as a catalyst. The reaction conditions were varied as follows: fixed temperature at 180 °C, with reaction times of 15, 30, and 60 minutes and fixed reaction time of 60 minutes, with temperatures of 140 °C, 160 °C, and 180 °C.

Upon completion, the reaction mixtures were rapidly cooled to room temperature. The liquefied products were diluted with methanol and vacuum-filtered to separate unreacted residues. The efficiency of liquefaction was assessed based on the mass of residual solids and the solubility of the filtrate.

2.4. Polyurethane Foams Production

Polyurethane (PU) foams were produced using polyols obtained from liquefied Mahogany and Red Angico woods at 180ºC and 60 min. The polyols were neutralized with NaOH and dried before been used for the production of foams.

Polymeric methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (pMDI), with a 31% NCO content and 2.7 functionality, was used as the isocyanate source. Water served as the chemical blowing agent, reacting with the isocyanate to produce carbon dioxide, which promoted foam expansion. A silicone-based surfactant (Tegostab) was incorporated to stabilize the foam structure and ensure uniform cell morphology throughout the foaming process. No additional catalysts were added to the formulation.

Foam formulations were prepared by varying both the isocyanate index and the water content. The isocyanate index was adjusted from 1.0 to 4.9, based on the hydroxyl number of the liquefied wood polyols, to investigate the effect of crosslink density on foam properties. Water content was 5%, 7.5% and 10% relative to the total polyol weight, to evaluate the influence of gas generation on foam structure and mechanical performance.

In each experiment, the liquefied wood polyols, water, and Tegostab surfactant were first mixed at 1500 rpm for 1 minute using a high-speed mechanical stirrer to achieve a homogeneous mixture. Subsequently, the calculated amount of pMDI was added, and the mixture was stirred for an additional 1 minute at the same speed. The reactive mixture was then immediately poured into open cylindrical molds with a diameter of 35 mm and allowed to freely expand at room temperature. After full expansion, the foams were cured at ambient conditions for 48 hours before testing. A 35 mm high cylindrical shape sample was cut from the mold ensuring there was no empty spaces in the foam.

The resulting PU foams were characterized in terms of their apparent density, compressive strength, and compressive modulus. The apparent density was determined according to ASTM D1622 [

39], by measuring the mass and volume of the cured foam samples. Compressive strength and compressive modulus were measured following ASTM D1621 [

40] using a Servosis I-405/5 universal testing machine (Servosis, Madrid, Spain). All measurements were performed in triplicate, and the reported values represent the average of these measurements.

3. Results and Discussion

The chemical composition results obtained in this study reveal both similarities and notable differences when compared to previously published data for Red Angico wood (

Table 1). In terms of extractives, this study reports 0.22% dichloromethane-soluble extractives, 3.25% ethanol-soluble extractives, and 1.77% hot water-soluble extractives, totaling 5.24% (

Table 1). This is significantly lower than the 14.3% total extractives (12.6% water-soluble and 1.7% ethanol-soluble) reported by Villanueva et al.[

17], and also lower than the 20.68% extractive content found in wood samples from APNE-managed forests in Pernambuco[

16]. Such differences may stem from variations in extraction protocols, solvent polarity, wood origin, or the physiological characteristics of the trees sampled.

Regarding lignin content, the Klason lignin value determined in this study is 20.63%, which closely aligns with the 18.8% reported by Villanueva et al. [

17] and falls well within the general range observed in other regional studies, which span from 16.37% to 24.89% [

15]. This supports the classification of Red Angico as a hardwood species with a moderate to high lignin concentration.

The α-cellulose content in this study is 48.44%, which is higher than the 43.3% glucan reported by Villanueva et al [

17]. Assuming glucan primarily represents cellulose in their analysis, the elevated α-cellulose value may suggest a higher degree of fiber purity in the samples analyzed here. It may also reflect methodological differences, as α-cellulose quantification tends to more selectively isolate the pure cellulose fraction, excluding other polysaccharides.

For hemicelluloses, the value observed in this study is 25.68%, which exceeds the 21.2% reported by Villanueva et al. [

17] (based on the sum of xylan, arabinan, mannan, and galactan). Nevertheless, some galactan may also come from hemicelluloses and uronic acids did not seem to be accounted for. In conclusion, while the data from this study generally align with previously published values, particularly for lignin, it shows a higher content of structural polysaccharides (cellulose and hemicelluloses) and a lower proportion of extractives. These differences highlight the influence of geographic origin, forest management practices, and analytical techniques on the reported chemical composition of Red Angico wood.

The chemical composition of Mahogany varies widely across different studies and regions, which is evident when comparing the values presented in

Table 1 with previously reported data. Results show a low α-cellulose content of 18.24%, significantly lower than values reported for Mahogany wood from Bangladesh (57.90%) and Indonesia (ranging from 35.38% to 47.26%) [

4,

5,

6]. Conversely, the hemicellulose content of 56.11% is substantially higher than the typical 11.20% to 28.94% reported in these studies, indicating possible differences in sample preparation or analytical methods. The Klason lignin content of 19.51% aligns reasonably well with previously reported lignin values, which generally range between about 25.82% and 28.50% but also can be as low as 19% depending on location [

4,

5,

6]. This suggests the lignin content measured here is within the expected range but toward the lower end. Regarding extractives, results show relatively low extractive contents for dichloromethane (0.42%), ethanol (4.02%), and hot water (1.70%), which total about 6.14%. This is lower than many reported extractive yields in the literature, which often vary widely, from under 4% in some Indonesian samples [

13,

14] to over 28% in Central and South American Mahogany [

12]. This variability is consistent with the multiple factors influencing extractives content, including tree age, wood type, stem position, and extraction solvents, as detailed by Arisandi et al. [

9]. Overall, data suggest a Mahogany sample with unusually high hemicellulose and low cellulose compared to typical values, and relatively low extractives. These differences highlight the strong influence of geographic origin, environmental conditions, and analytical methods on the chemical composition of Mahogany wood.

The comparative chemical composition of Red Angico and Mahogany presented in

Table 1 reveals notable differences in their primary and extractive constituents, which may be indicative of their respective structural and functional adaptations. Both species were analyzed for extractives in dichloromethane, ethanol, and hot water, as well as for major lignocellulosic components—namely, Klason lignin, α-cellulose, and hemicelluloses. Red Angico exhibited a lower content of dichloromethane-soluble extractives (0.22%) compared to Mahogany (0.42%), suggesting a relatively lower concentration of non-polar or lipophilic compounds such as waxes, fats, or resin acids. Similarly, the ethanol extractives were higher in Mahogany (4.02%) than in Red Angico (3.25%), indicating a greater abundance of polar extractives such as phenolics and low-molecular-weight sugars in Mahogany. In contrast, the hot water-soluble fraction was nearly identical between the two species, with Red Angico at 1.77% and Mahogany at 1.70%, reflecting a comparable solubility of water-soluble polysaccharides or other hydrophilic substances.

A more substantial difference is observed in the lignocellulosic matrix. Red Angico has a higher α-cellulose content (48.44%) than Mahogany (18.24%), indicating a greater proportion of crystalline cellulose, which is crucial for mechanical strength and resistance to biodegradation. Conversely, Mahogany demonstrates a remarkably higher hemicellulose content (56.11%) compared to Red Angico (25.68%). Hemicelluloses, being more amorphous and branched than cellulose, can influence the flexibility and reactivity of the cell wall. The elevated hemicellulose content in Mahogany may reflect its ecological strategy or developmental plasticity, possibly correlating with faster growth or a different anatomical configuration. The total Klason lignin content is slightly higher in Red Angico (20.63%) than in Mahogany (19.51%), though the difference is marginal. This parameter suggests a comparable investment in lignin biosynthesis, which is essential for rigidity, water transport, and resistance to microbial attack.

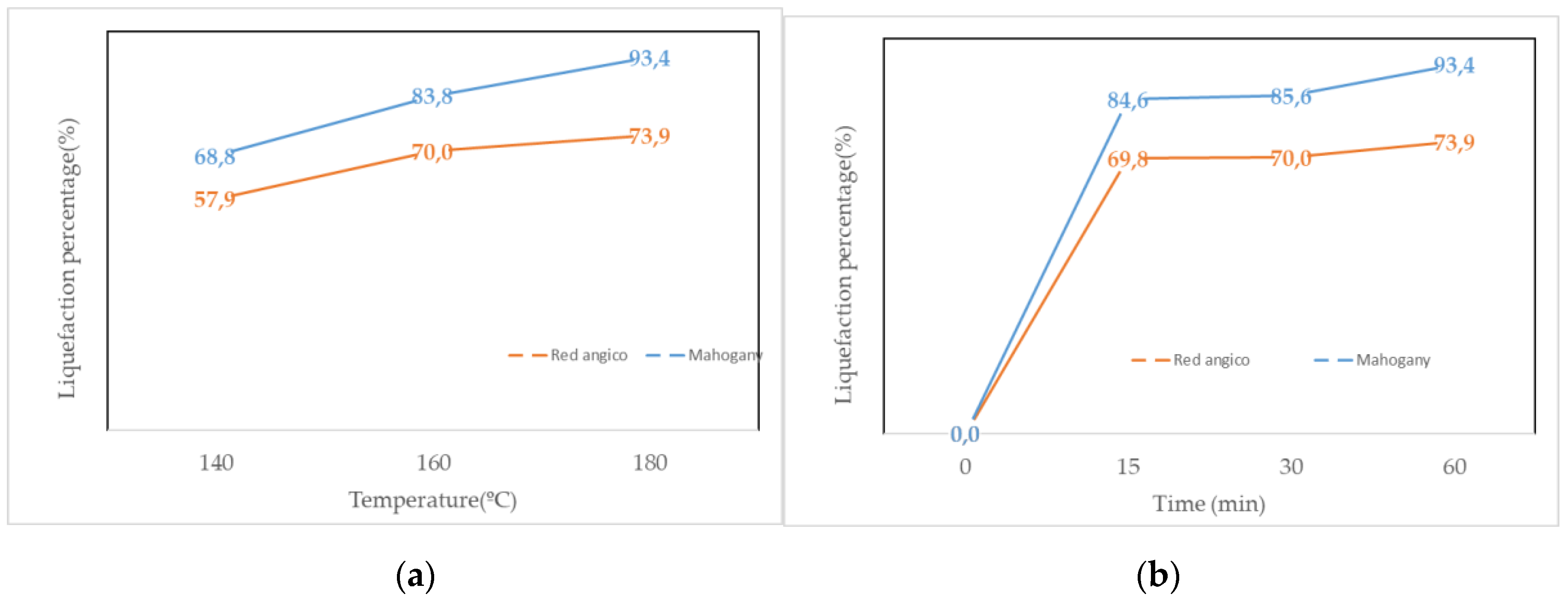

The liquefaction behavior of Red angico and Mahogany wood using polyalcohol liquefaction at a constant temperature of 180 °C across varying reaction times, and at a fixed reaction time of 60 minutes across different temperatures are presented in

Figure 1 (a) and (b). The results demonstrate clear distinctions in the reactivity and thermal behavior of the two wood species under the tested conditions. At 180 °C, both species exhibited rapid liquefaction within the first 15 minutes. Red angico reached a liquefaction percentage of 69.8%, while Mahogany achieved a significantly higher value of 84.6%, indicating greater susceptibility of Mahogany to chemical breakdown in the early stages of the reaction. This is most likely due to the higher hemicellulose content of Mahogany as seen in

Table 1. Hemicelluloses are known to be the most susceptible polymers to hydrolysis [

41]. As the reaction proceeded to 30 minutes, the liquefaction efficiency of Red Angico increased slightly to 70.0%, while Mahogany rose to 85.6%. By 60 minutes, Mahogany reached a liquefaction level of 93.4%, suggesting near-complete conversion, whereas Red Angico attained 73.9%, reflecting a slower or more limited reactivity under the same conditions. Red Angico exhibits a slower liquefaction rate due to its high cellulose and lignin content, making it more resistant to acid hydrolysis and requiring longer times or harsher conditions; its lower hemicellulose content results in a less easily degradable carbohydrate fraction initially, leading to a steady but slower liquefaction process with lower yields at shorter time intervals.

Temperature-dependent liquefaction at a fixed time of 60 minutes further highlighted the superior performance of Mahogany liquefaction. At 140 °C, Red Angico and Mahogany exhibited liquefaction percentages of 57.9% and 68.8%, respectively. Increasing the temperature to 160 °C enhanced liquefaction for both species, with Red Angico reaching 70.0% and Mahogany achieving 83.8%. Notably, while Mahogany continued to exhibit improved liquefaction at 180 °C (93.4%), Red Angico showed a slight increase to 73.9%. These results indicate that Mahogany is more efficiently liquefied by polyalcohol under thermal treatment than Red Angico, due to differences in their chemical composition and structural characteristics. For Mahogany, the combination of high temperature and extended reaction time leads to substantially higher liquefaction yields, whereas Red Angico appears to reach its optimal conversion efficiency at around 160 °C, with minimal improvement at higher temperatures. The findings underscore the importance of species-specific optimization in biomass liquefaction processes to maximize conversion efficiency and product yield.

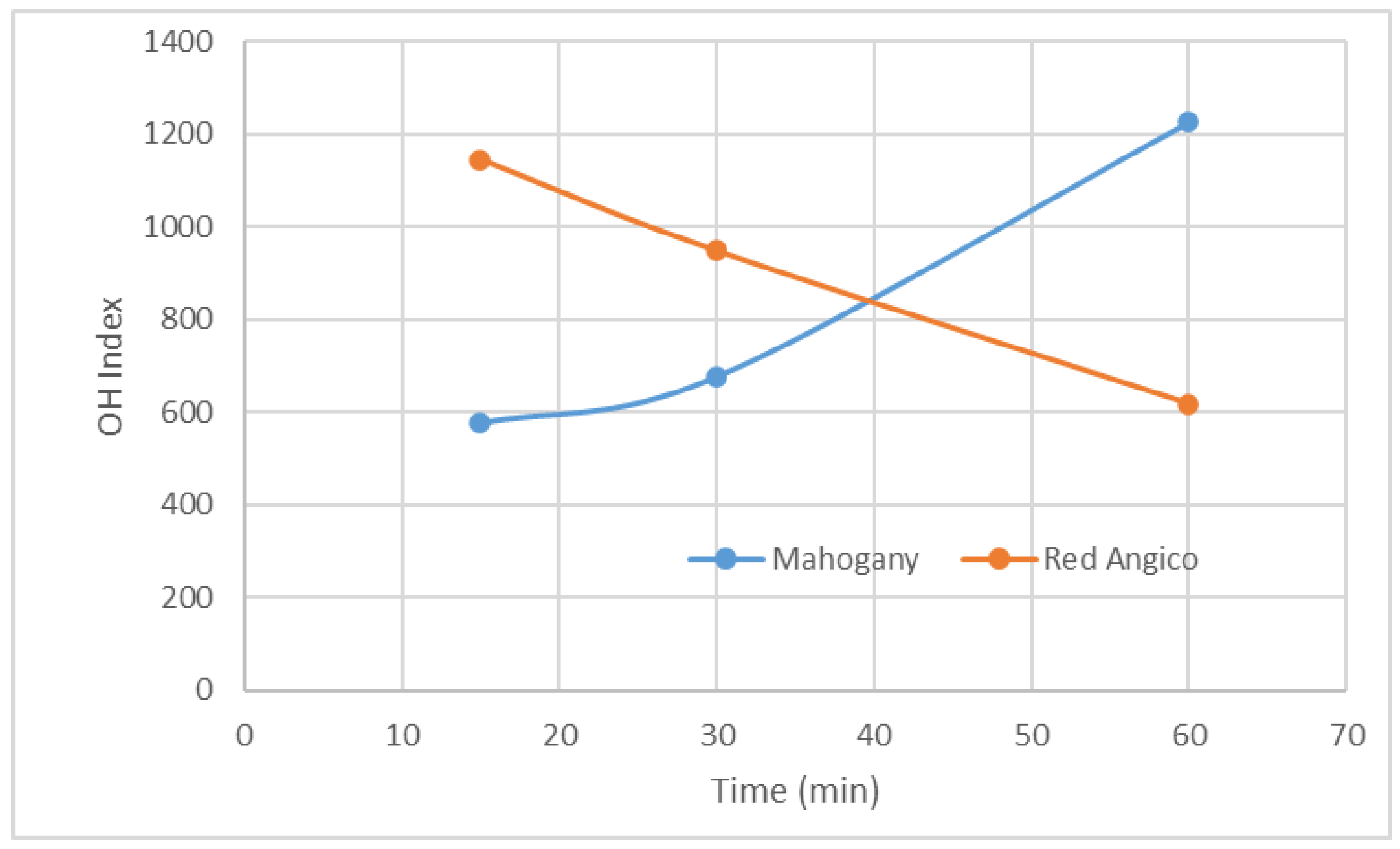

The hydroxyl (OH) index of polyols derived from the liquefaction of Mahogany and Red Angico using a glycerol and ethylene glycol cosolvent system illustrates the dynamic chemical changes occurring during thermal processing of lignocellulosic biomass. Liquefaction breaks down the complex structure of biomass, composed primarily of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, into smaller, reactive fragments. This initial depolymerization exposes or generates free hydroxyl groups, which typically results in an increase in the OH index, a key parameter reflecting the number of reactive sites available for further chemical modification, such as polyurethane synthesis.

The OH index trends observed for Mahogany and Red Angico during liquefaction at 180 °C reflect distinct differences in their chemical behavior under acidic conditions. Mahogany shows a continuous and significant increase in OH index, from approximately 580 at 15 minutes to over 1200 at 60 minutes. This steady rise indicates effective and ongoing depolymerization, primarily driven by its high hemicellulose content (56.11%), which is readily hydrolyzed in the presence of sulfuric acid. The continued increase beyond 30 minutes suggests that both hemicellulose and possibly some cellulose fractions are being converted into hydroxyl-rich products, contributing to a higher functional group density in the liquefied material. In contrast, Red Angico exhibits a declining OH index over the same time range, but starting from about 1120 at 15 minutes and decreasing then to around 620 at 60 minutes. The decreasing OH index over time implies that recondensation or cross-linking reactions may dominate as the reaction proceeds, leading to the consumption of free hydroxyl groups and a corresponding drop in the measured index.

Overall, the data indicate that Mahogany needs more time the achieve higher Hydroxyl values. In contrast, Red Angico, while initially reactive, may be prone to secondary reactions that reduce its functional group availability, suggesting a need for shorter reaction times or modified conditions to preserve its hydroxyl content. This decline is consistent with the occurrence of secondary reactions such as condensation, dehydration, and thermal degradation. These processes can consume hydroxyl groups, form water, or convert hydroxyls into other functional groups, thus reducing the overall OH content. Increased reaction time generally leads to a decrease in hydroxyl value as reported before by Jin et al. [

42]. As the liquefaction time increased, the hydroxyl value of the polyol from wheat-straw lignocellulose with steam-explosion pretreatment decreases.

A similar effect has been reported for higher temperatures. According to Lee et al. [

43] that studied liquefaction of empty fruit bunch lignin residue, as the reaction temperature increased from 130 °C to 190 °C, the hydroxyl number of biopolyols decreased. Similar results were presented before by Wang and An [

44]

These contrasting trends highlight the complex interaction of depolymerization and re-polymerization mechanisms during liquefaction. While early stages typically enhance the OH index due to fragmentation and exposure of new hydroxyl sites, prolonged reaction times often lead to a decline in OH content due to increased molecular weight through polycondensation and loss of hydroxyls. This species-specific behavior is crucial for tailoring liquefaction conditions to optimize the chemical functionality of resulting polyols for applications such as bio-based resins and foams.

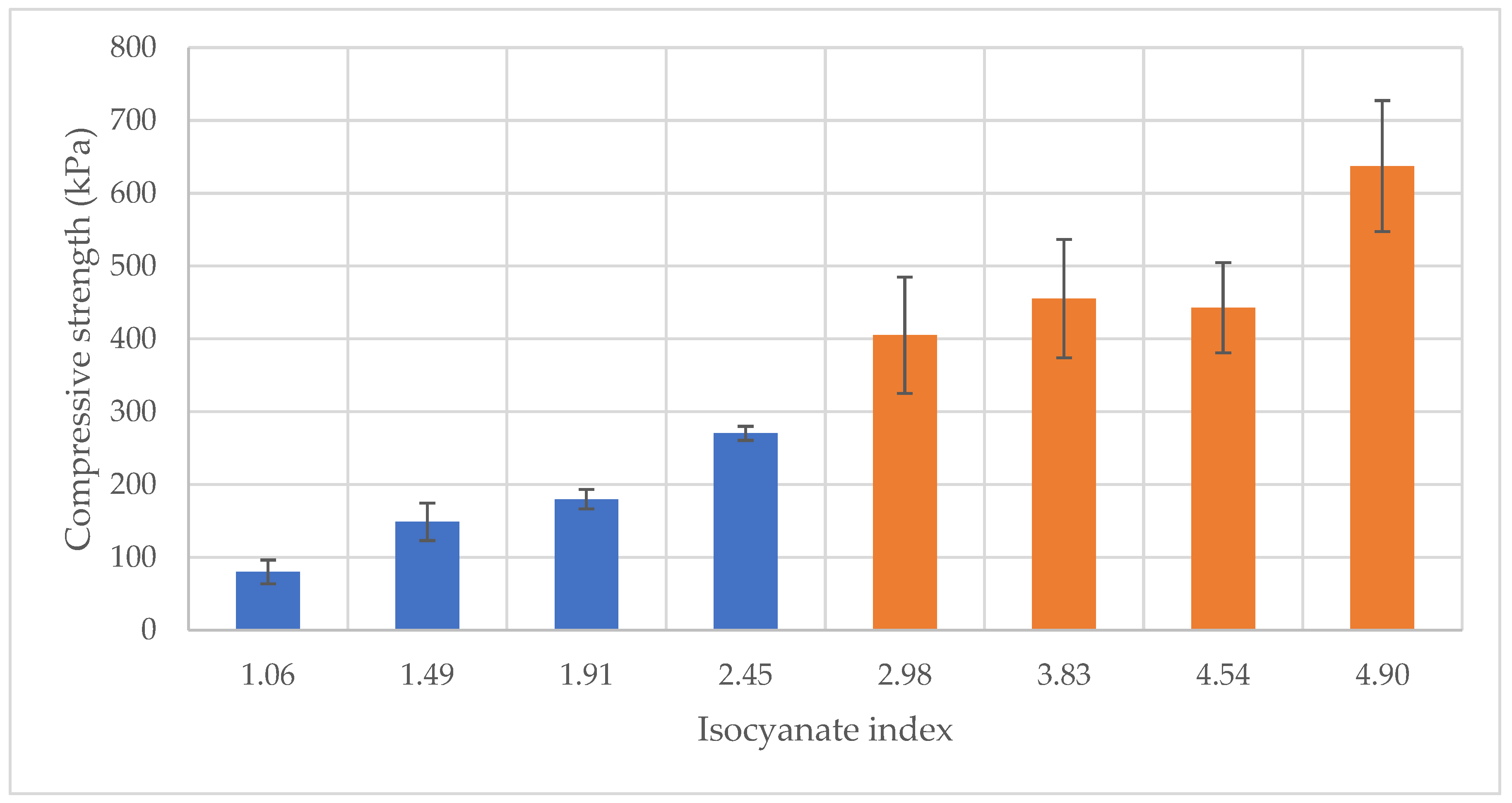

The compressive properties of foams synthesized from liquefied Red Angico wood demonstrated a clear dependency on the isocyanate index, as illustrated in

Figure 3. The compressive strength increased with rising isocyanate index, suggesting an enhancement in the mechanical integrity of the polymer matrix.

At an isocyanate index of 1.06, the compressive strength of Mahogany foams was approximately 80 kPa, indicating relatively weak structural cohesion, compared to higher Isocyanate indexes. As the isocyanate index increased to 1.49 and 1.92, the compressive strength rose to about 150 kPa and 180 kPa, respectively. At the highest isocyanate index of 2.45, compressive strength significantly improved to around 270 kPa. Starting at 2.98 isocyanate index, the compressive strength of Red Angico foams was approximately 400 kPa,. As the isocyanate index increased, the compressive strength rose to about 460 kPa. At the highest isocyanate index of 4.90, compressive strength significantly improved to around 640 kPa. This marked increase points to a more extensively crosslinked and structurally robust network. However, it is important to note the considerable variability in strength for higher isocyanate indexes, as evidenced by the large error bars, which may be attributed to inhomogeneities in the foam microstructure.

Figure 2.

Variation of OH index along liquefaction.

Figure 2.

Variation of OH index along liquefaction.

Overall, these results demonstrate that increasing the isocyanate index enhances compressive strength of liquefied Mahogany and Red Angico-based foams similarly to the presented before [

45,

46,

47]. The significant variability observed across samples suggests that optimization of formulation and processing conditions will be critical for improving consistency and mechanical reliability in future applications.

The comparison between Mahogany and Red Angico foams becomes particularly meaningful when considering that the first four columns of each series, those at isocyanate indices 1.06, 1.49, 1.91, and 2.45 for Mahogany and 2.98, 3.83, 4.54, and 4.90 for Red Angico, were all produced using the same absolute amounts of isocyanate. The difference in isocyanate index stems from the differing hydroxyl values of the polyols: Mahogany has a hydroxyl value of 1200 mg KOH/g, while Red Angico’s is 600 mg KOH/g. Since the isocyanate index is based on the molar ratio of NCO groups to OH groups, Mahogany’s higher hydroxyl value means a lower isocyanate index for the same isocyanate input.

With equal isocyanate dosage (different Hydroxyl value), Red Angico foams consistently exhibit higher compressive strength and modulus values across all corresponding points. This suggests that Red Angico’s lower hydroxyl content leads to a more isocyanate-rich system, favoring the formation of a stiffer, more crosslinked polymer network. In contrast, Mahogany, with more hydroxyl groups relative to the same amount of isocyanate, likely forms a network with lower crosslink density and more unreacted sites, resulting in softer foams.

Another question is the ideal hydroxyl value for polyurethane production. Several authors stated that the ideal hydroxyl value was between 300 and 800 [

48]. Lim et al. [

49] reported that the hydroxyl value of the polyol significantly influences the physical and thermal properties of rigid polyurethane foams. While properties like closed cell content, compression strength, and dimensional stability generally improve with increasing hydroxyl value due to higher crosslink density, other properties such as reaction times, density, and thermal conductivity show an optimal point around 500 Hydroxyl value, indicating a complex interplay between mixture mobility and crosslinking reactions. The high hydroxyl value (≈ 1200 mg KOH/g) of liquefied Mahogany wood polyol can contribute to the relatively low compressive strength observed in these rigid polyurethane foams. Hydroxyl value is known to be inversely related to the molecular weight of the polyol. A high hydroxyl number indicates a highly functional, short-chain polyol with numerous reactive OH groups, which in turn promotes very dense crosslinking in the polymer network. This results in a rigid, brittle foam structure that compromises the flexibility and performance needed for applications demanding cushioning and resilience [

50]. Additionally, high hydroxyl-value polyols are often highly viscous, which hinders effective mixing and uniform cell formation. Poor dispersion and rapid curing may lead to heterogeneous cell morphology, large cell size variance, and defects that impair strength. Lim et al. [

49], stated that this is due to the excessive allophanate crosslinking between urethane linkages and residual isocyanate groups that increases the viscosity of the reacting mixture, which slows down both the gelling and foaming processes.

Figure 3.

Variation of Compressive strength with Isocyanate index for Mahogany(blue) and Red Angico (Orange).

Figure 3.

Variation of Compressive strength with Isocyanate index for Mahogany(blue) and Red Angico (Orange).

Figure 4 shows how the compressive modulus of foam varies with the isocyanate index for the two types of biomass: Mahogany (blue bars) and Red Angico (orange bars). Overall, the compressive modulus tends to increase with the isocyanate index for both materials, but the trends and performance levels differ between them. For Mahogany-based foams, there is a gradual increase in compressive modulus as the isocyanate index rises from 1.06 to 2.45, maxing out at around 4.5 MPa. The variability in the data, indicated by the error bars, increases notably at an index of 1.91, suggesting inconsistent structural integrity at this ratio. Starting at an index of 2.98, Red Angico-based foams also show a compressive modulus increase with the isocyanate index, and continue to increase steadily, reaching about 5.7 MPa at an index of 4.90. Despite the improved mechanical performance at higher isocyanate indices, the broad error margins again highlight the influence of microstructural variability on the reproducibility of compressive properties.

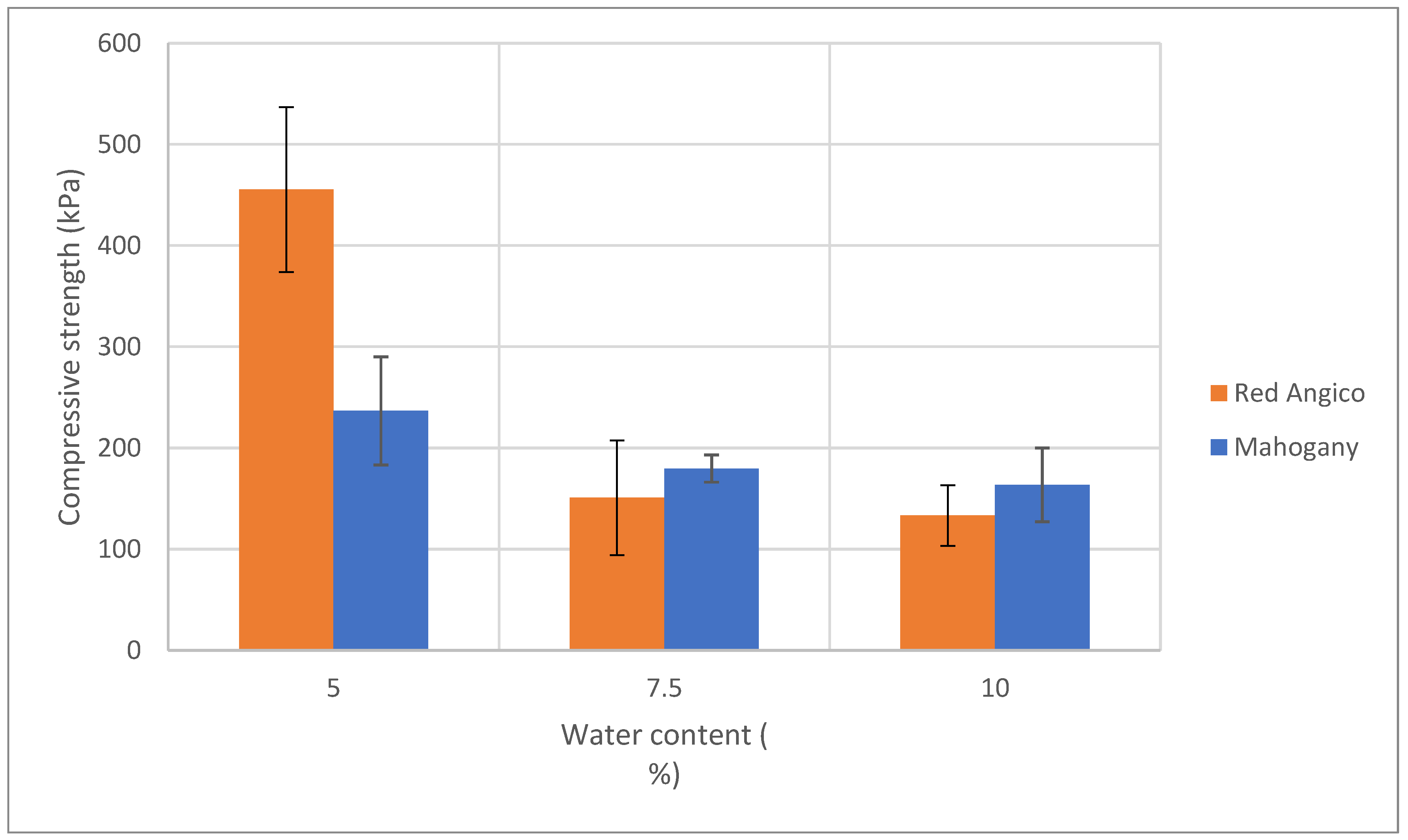

Figure 5 illustrates how the compressive strength of Mahogany and Angico-based polyurethane foams changes with varying water content, which acts as a chemical blowing agent. The trend shows a clear decrease in compressive strength as the water content increases from 5% to 10% and this decrease is observed for both polyols. This suggests that lower water levels lead to denser, more compact foam structures with stronger mechanical properties, but possibly also less consistency in cell structure. As water content increases, compressive strength decreases, which was expected because more water generates more CO₂ during the reaction, resulting in higher porosity and lower foam density. Excessive use of water can be damaging since in accordance to Lim et al. [

49] it causes a negative pressure gradient due to the rapid diffusion of CO

2 through the cell wall, causing cell deformation.

In summary, increasing water content reduces the compressive strength of foams due to increased porosity and decreased density. A trade-off exists between lightness and mechanical integrity, and an optimal blowing agent level should balance both, depending on the intended application.