Introduction: The Hardest Problem in Drug Discovery

Over the last 20 years, the number of new drug modalities have multiplied quickly [

1]. Despite this, the oldest modality, small molecules, still accounts for ~3/4 of drugs approved by the FDA over the last decade [

2,

3] . Small molecules continue to dominate and even flourish for three main reasons: (1) small molecules have inherent distribution advantages with potential to reach every organ, cell, and organelle in the body; (2) modern engineering principles enable us to scale production and deliver them economically worldwide in predictable ways; and (3) our increased understanding of how small molecules engage proteins has led to a renaissance of new small molecule targeting modalities, such as covalent modifiers, correctors, allosteric modulators, induced proximity, degraders, and RNA/splicing/PPI/condensate modulators.

However, the ability to modulate all functions in the body also belies the challenges of dialing in unpredictable pharmacokinetic and safety properties. Drug discoverers must optimize for high potency at the target while avoiding interactions with related or idiosyncratic off-target proteins. The discovery process must also navigate problematic ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) issues that would cause a candidate to fail in preclinical development or, worse yet, clinical trials. Thus, drug design requires a multiparameter optimization process that balances many different factors [

1,

3]. While every new target and related off-targets are unique to every program, the ADMET properties are shared, and thus the focused development of predictive tools would broadly enable small-molecule drug discovery. Over the last 40 years, we’ve come to understand ADMET issues are largely driven by a finite set of proteins and physicochemical properties that can be measured in individual assays. While pharmacophore models and heuristics have been created to tackle specific liabilities, the field has not taken a systematic approach to understanding and correcting ADMET liabilities. Additionally, structure-based design, which has become a key part of modern drug discovery, is seldom used beyond primary target binding.

Despite significant progress in structure-based design and affinity prediction, ADMET properties remain the main reason for failure in drug discovery. More than 90% of molecules created during discovery fail to meet basic ADME standards [

3,

4,

5]. Additionally, it is estimated that about 20% of drug candidates fail in preclinical toxicity tests, and around 30% of clinical failures are due to unexpected ADMET problems [

3,

4,

5]. Traditional methods that focus mainly on bulk molecular properties [

6], such as logP, solubility, or hydrogen bond donor counts, offer only vague guidance because they lack insight into the atomic-level interactions between drugs and the body’s complex systems. Several machine learning (ML) representations [

7], including chemical fingerprints, molecular graphs, 3D geometry-based models, and protein language models, are already aiding ADMET predictions. However, two key challenges hinder breakthroughs in predictive ADMET: the data remain extremely limited, and most models lack the atomistic detail needed for mechanistic understanding. What is missing from this perspective is a systematic, detailed understanding of the “Avoid-ome”: the broad set of proteins that influence the ADME and toxicity properties of all drug molecules [

8]. By focusing the tools of modern structure-based drug design on the Aviod-ome, drug discovery practice could be transformed.

Defining the Avoid-Ome

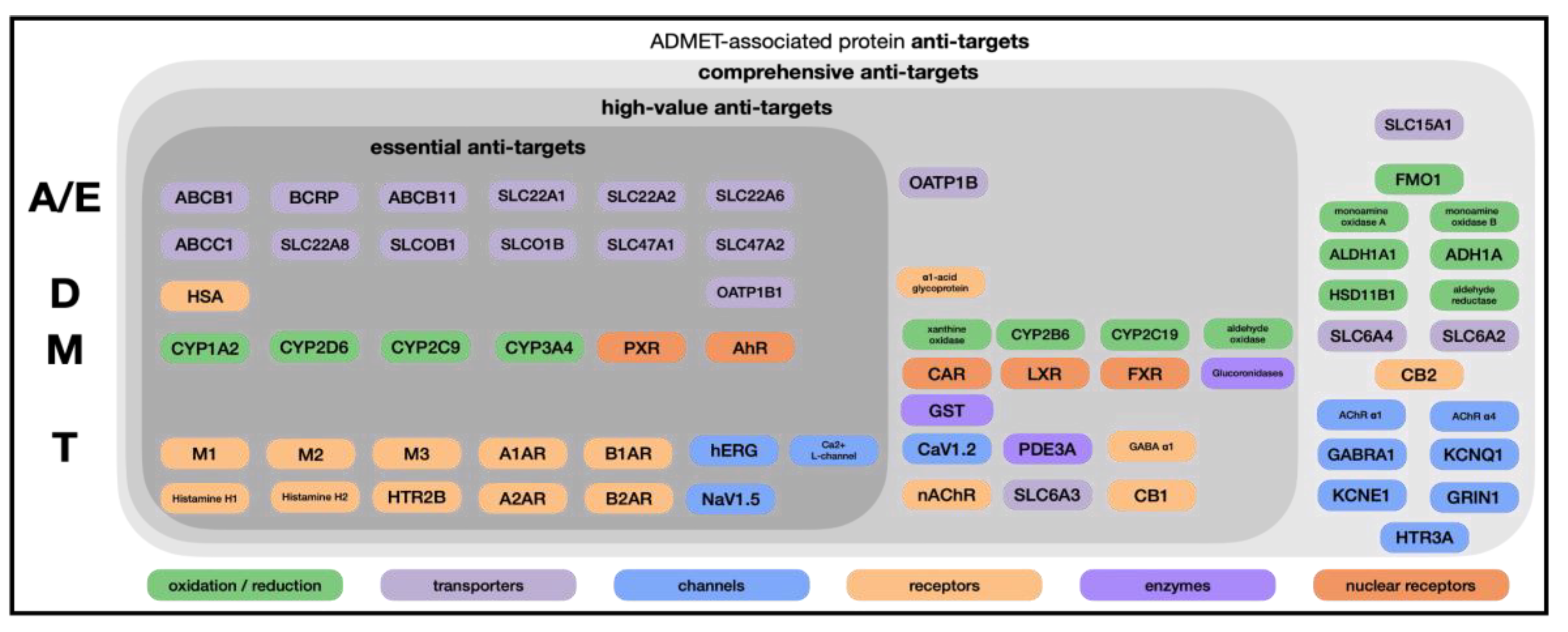

The Avoid-ome consists of enzymes, transporters, receptors, and channels that determine whether a compound reaches its intended target or fails due to off-target binding [

9,

10]. These include metabolic enzymes like cytochrome P450s (CYPs) [

11], aldehyde oxidase [

12], UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) [

13], and glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) [

14]; transporters from the ABC [

15] and SLC [

16] families; plasma proteins such as serum albumin [

17]; xenobiotic sensors like the pregnane X receptor (PXR) [

18] and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) [

19]; and common toxicity drivers such as the hERG potassium channel [

20], the voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.5 [

21], and L-type calcium channels [

22]. The primary Avoid-ome targets can be divided into four groups: absorption and excretion (A/E), distribution (D), metabolism (M), and toxicity (T) (

Figure 1).

Importantly, the Avoid-ome is a finite set: although thousands of proteins exist in the human proteome, only on the order of 50-100 proteins occur with high frequency as mediating ADMET properties; considering less common situations, perhaps a few hundred proteins in total are responsible for the preponderance of the ADMET challenges faced by discovery teams. This bounded scope makes the Avoid-ome problem tractable if we can systematically generate and share the correct data.

Some Avoid-ome proteins are exploited therapeutically, such as P-gp in cancer [

23] or SGLT2 in diabetes [

24]. However, in most cases, drugs must be engineered to avoid them. Avoid-ome proteins are therefore not generally “targets” (the intended binding partner of a drug) or “off-targets” (proteins related to the intended binding partner). Instead, they are “anti-targets” (proteins that must be considered as potential confounders in most drug development projects) .

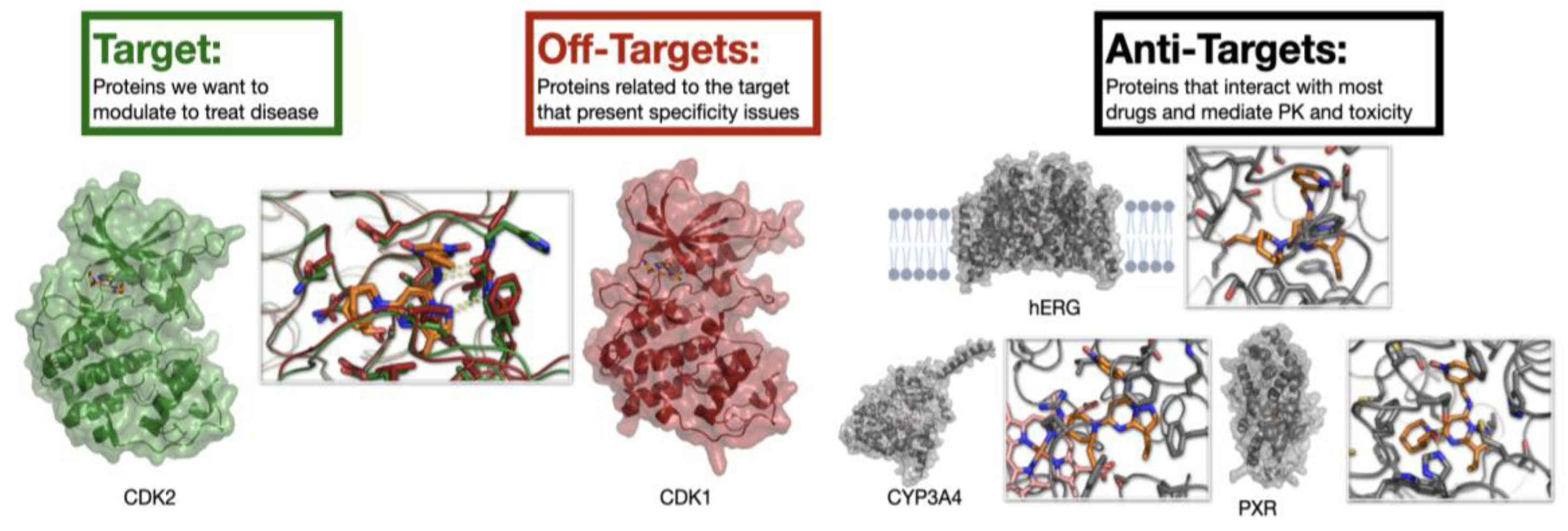

Consider an example of a kinase inhibitor to illustrate the distinctions between targets, off-targets, and anti-targets (

Figure 2). Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) [

25] is a vital serine/threonine protein kinase that plays a crucial role in regulating the eukaryotic cell cycle, particularly during the transition from the G1 phase to DNA synthesis (S phase). Abnormal (uncontrolled) activity of the CDK2/Cyclin E complex is commonly observed in many human cancers. This leads to increased cell proliferation and genomic instability, making CDK2 an important target for anti-cancer therapies. The primary off-targets of CDK2 inhibitors are usually other members of the CDK family because of their high similarity in ATP-binding sites. Ensuring off-target selectivity during the design of CDK2 inhibitors is essential for the safety and effectiveness of the drug. Lack of selectivity was a major reason why first-generation CDK2 inhibitors failed in early clinical trials. Additionally, anti-target selectivity against proteins such as CYPs and PXR is vital to prevent drug interactions, and avoiding the hERG ion channel is crucial in designing CDK2 inhibitors to prevent serious cardiac side effects. As the focus shifts from targets to off-targets and anti-targets, the number of binding sites and interactions to consider increases dramatically. The task of optimization is further complicated by the promiscuity of anti-targets, which have evolved to recognize a wide range of xenobiotics. This highlights the central challenge: success requires simultaneous optimization against every anti-target, yet systematic data on these interactions are almost entirely lacking.

The Case for OpenADMET

How can we enable breakthroughs in ADMET modeling? Deep learning approaches crave data [

26], yet very little is known about the ADMET properties of drug-like compounds. Publicly accessible databases, such as ChEMBL [

27] and the Therapeutics Data Commons [

28], include ADMET datasets compiled from the literature. However, this data has often been extracted from dozens of papers, each using different experimental procedures. As highlighted in a recent paper by Landrum and Riniker [

29], reported values in the literature are rarely consistent. The pharmaceutical industry could be a valuable source of ADMET data. In fact, important ADMET datasets are stored within pharmaceutical companies, and making this data publicly available would be beneficial. However, even full access to this data would still be insufficient. To gain a comprehensive understanding, we need to systematically examine the interactions between the most common Avoid-ome targets and diverse sets of ligands that broadly cover chemical space.

The convergence of multiple factors has created an opportunity to systematically improve ADMET optimization. Recent advances in structural biology have enabled higher-throughput data collection and will allow us to study the structures of Avoid-ome proteins on a much larger scale. Additionally, developments in mass spectrometry have made collecting experimental data more cost-effective. Finally, the availability of open-source machine learning models has provided the ability to link structural and assay data to develop new strategies for compound optimization.

OpenADMET (

http://openadmet.org), a major international open--science initiative initially funded by ARPA-H, the Gates Foundation, and the Astera Institute, aims to leverage these scientific advances and address the ADMET data gap by developing pre-competitive, open datasets covering metabolism, transport, distribution, and toxicity. We are creating platforms to make synthesizing compounds, conducting measurements, and learning from data cheaper and higher throughput. These large, openly accessible datasets will serve as a shared resource for the global research community. Our approach also leverages high-throughput structural biology to support model interpretability, identify outliers and cryptic binding modes, and ensure models are grounded in mechanistic, atomistic insights (

Figure 3).

In addition to the elements described above, genetic variation-aware predictions will be needed to realize the potential of pharmacogenomic analyses. We are integrating data such as VAMPseq [

30] protein expression levels and atomistic modeling of how variants alter ADMET risk by changing interactions between the compound and the anti-target. Pre-clinical species translation is another essential component, requiring structural models that explain why compounds behave differently across rats, dogs, monkeys, and humans [

31].

Another often-discussed alternative approach to feeding the data needs of machine learning approaches in ADMET is federated learning [

32], where models are trained behind a firewall that can observe data from companies without sharing the underlying molecular identities. While appealing in principle, such solutions tend to reinforce limitations: they remain confined to local chemical space, they struggle to generalize, and they rarely deliver the mechanistic clarity required to address Avoid-ome proteins. By contrast, active learning [

33] over diverse chemical space creates the conditions for truly generalizable models and deeper insights that can benefit the entire community. Freed from the constraints of having to generate molecules to “avoid” anti-targets, in OpenADMET we can synthesize and test compounds that are most informative for building predictive models. This close link between experiment and computation lets us ask, “which experiments will enable us to build the best model?”

Another key element of OpenADMET is the creation of blind community challenges to benchmark models using unreleased data, thereby promoting rigorous evaluation and continuous improvement. Collectively, these strategies will generate the data necessary for improved predictions and establish a framework for integrating functional data on specific anti-targets with bulk property assays, such as stability in the presence of liver microsomes, to connect mechanistic understanding with applied pharmacology.

Assays

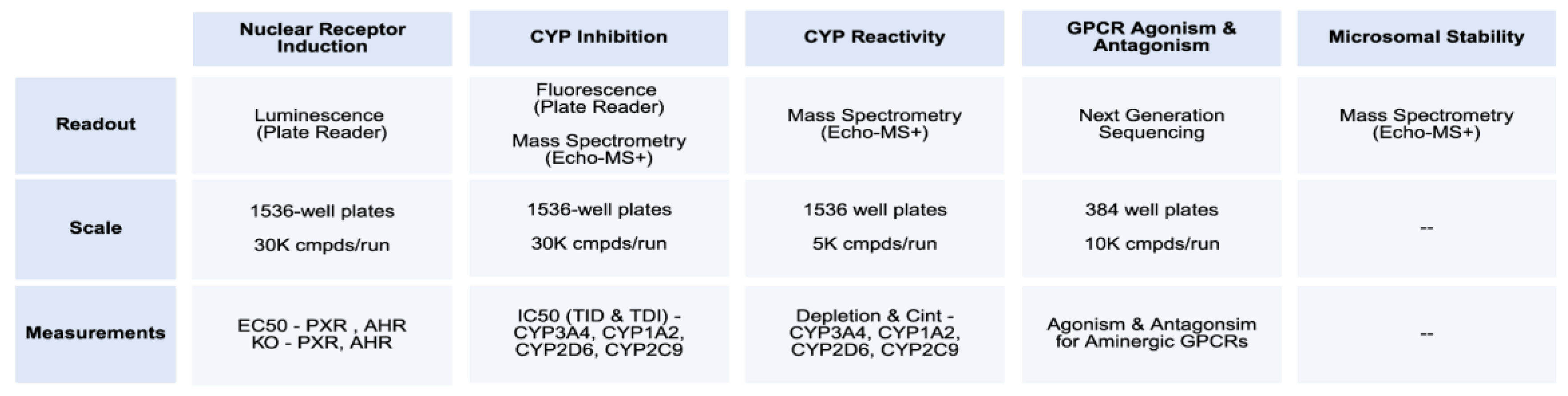

The OpenADMET initiative requires diverse assays across many anti-targets: biochemical assays for metabolism and transport, electrophysiology for ion channels, binding assays for plasma proteins, and transcriptional readouts for xenobiotic sensors (

Figure 4). A key goal is to modernize these assays, making them cheaper, more scalable, and more translatable. We begin by characterizing individual Avoid-ome targets to understand the mechanistic basis of ADMET liabilities before progressing to integrative assays like microsomal stability.

For metabolism and biochemical assays, we leverage scaled mass spectrometry [

34] to enhance throughput and reduce costs. For cellular assays, we employ synthetic biology [

35] to engineer high signal-to-noise genetic reporters and routinely include counter-assays with target knockouts to mitigate PAINS effects. Our goal is affordable, quantitative, scalable methods applicable to both purified compounds and those from next-generation direct-to-biology platforms. Currently, we evaluate CYP reactivity for thousands of compounds at <

$0.40 per compound using an Echo-MS+ ZenoTOF 7600 system. Luminescence and fluorescence assays cost

$0.05-

$0.30 per well and can screen tens of thousands of compounds weekly.

As we expand beyond initial targets, many assays can be built on existing capabilities and workflows. Some, like additional CYP targets or CAR, will be straightforward to implement. Others require further development: integrative endpoints, such as microsomal stability, will leverage our mass spectrometry platform but will require additional optimization for cost and scale. Meanwhile, aminergic GPCRs will utilize barcoded genetic reporters with sequencing readouts [

36] for multiplexed screening. Assays such as the hERG potassium channel pose significant technical challenges and will require evaluating multiple approaches, including electrophysiology and high-throughput fluorescence.

Chemistry

Our understanding of small-molecule Avoid-ome interactions is extremely sparse. There are, of course, existing examples of drugs known to interact with specific Avoid-ome targets. For example, terfenadine is a ~4µM inhibitor of hERG [

37] and ketoconazole inhibits CYP3A4 with an IC

50 of ~40nM [

38]

. However, public data is usually not available for close analogs of these compounds. Furthermore, little is known about the Avoid-ome interactions that might exist within larger collections of drug-like molecules. To improve learning, we aim to quickly synthesize libraries of analogs to hits to identify activity cliffs [

39], which are among the most valuable and challenging issues to predict over time. As with most drug discovery efforts, we have several methods to explore the structure-activity relationships (SAR) around compounds that bind to Avoid-ome targets. We can purchase compounds similar to known binders using an “analog by catalog” method, which has become a standard approach in pharmaceutical research. Starting with a library of 10,000 drug-like compounds, we typically have about 20 commercially available analogs for each one. These analogs can also be supplemented by synthesis-on-demand libraries [

40], which currently number in the billions, or through custom synthesis at contract research organizations (CROs). An internal synthesis capability can provide an additional way to explore the SAR around Avoid-ome targets. By synthesizing and stockpiling key scaffolds and intermediates, hundreds of analogs can be rapidly generated and characterized. This process can potentially be further streamlined by avoiding time-consuming purification steps and conducting assays on crude reaction mixtures [

41].

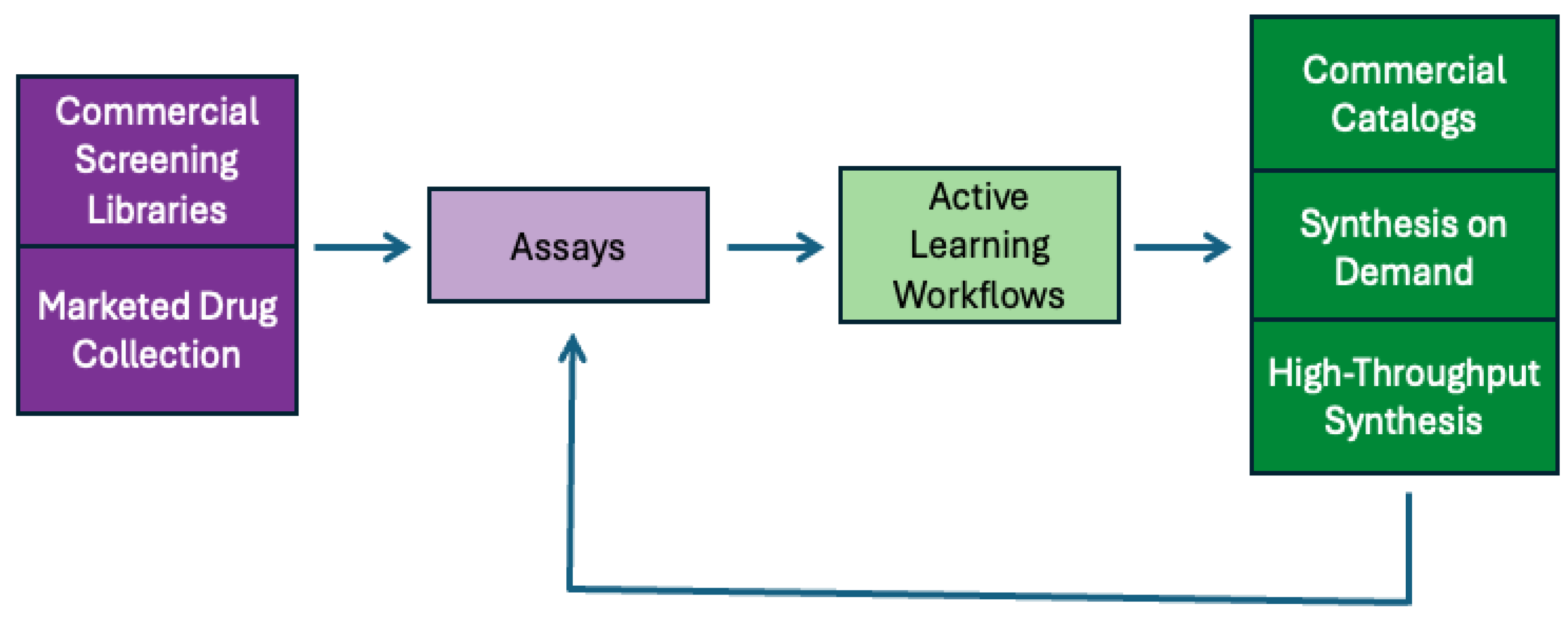

In addition to running assays on diverse chemical libraries, OpenADMET is also performing follow-up chemistry (

Figure 5) to further investigate SAR for Avoid-ome targets. The ADMET model-building process begins with screening commercial libraries or marketed drugs experimentally. After collecting an assay dataset, an active learning workflow can select additional compounds for synthesis and testing, which enhances the model’s accuracy. This active learning approach employs a machine learning model that includes a measure of uncertainty, helping to balance exploration and exploitation during model development. The compounds chosen through active learning can then be synthesized using the various routes described above.

Structural Biology’s Central Role

Structural biology must also extend beyond traditional target enablement to illuminate the Avoid-ome [

42]. Examples already include solving the structures of serum albumin complexes to explain drug partitioning, cryo-EM of transporters to decode efflux liabilities, and crystallography of PXR or CYP3A4 to guide metabolic risk mitigation. High-resolution structures provide critical insights, including snapshots of multiple conformations of proteins [

43] and ligands [

44], a framework for modeling species differences and human genetic variants, and the grounding required for mechanistic understanding when machine learning predictions diverge. Structural biology is also uniquely suited to seed exploration of new regions of chemical space, whether by identifying new chemical matter and binding sites through X-ray fragment screening campaigns [

45] or by testing the outcomes of virtual screens [

46]. Equally important, it allows us to define the structural basis of outliers identified by other models by directly solving their complexes. The breakthrough capabilities of CryoEM for membrane proteins will provide a mechanistic basis for many transport and toxicity targets. Determining the binding modes of compounds bound to Avoid-ome proteins is especially exciting from a structural and mechanistic perspective, precisely because they are promiscuous and often highly dynamic, able to accommodate diverse ligands in multiple poses [

47]. The promiscuity of Avoid-ome proteins may make them particularly difficult for co-folding methods (such as AlphaFold3) to discriminate binders from non-binders and to generalize to new chemical spaces with the correct binding poses [

48]. In addition, avoid-ome proteins often show strong species- and variant-specific differences, which is a frontier area for computational modeling at atomic-scale accuracy.

Computation

Over the past decade, there has been a notable increase in papers discussing the use of machine learning in chemistry and drug discovery. Unfortunately, the shortage of high-quality datasets has slowed progress in ADMET prediction. Most datasets used for training and benchmarking ADMET models are gathered from scientific literature. These datasets are often compiled from 20 to 50 different papers, each with distinct experimental conditions. Issues with reproducibility are demonstrated by a recent paper from Landrum and Riniker [

29], where the authors compared IC

50 values for the same compound tested against the same target in different papers. They found almost no correlation between the reported values. Given this variability, it is unrealistic to expect that datasets compiled from multiple literature sources will produce reliable machine learning models.

To build reliable models, we need large, consistently measured datasets of drug-like molecules that accurately reflect the data values observed in drug discovery. OpenADMET will create this data and share it with the community in a format suitable for training and evaluating machine learning models. This data will not only help train models but also promote the development of new molecular representations and algorithms. To advance the field, we must go beyond simple graph-based representations to scalable ones that accurately capture essential molecular interactions.

In addition to generating data, OpenADMET is developing a software framework, ANVIL, to record and codify best practices for machine learning model development. This open-source software allows users to easily test different molecular representations and machine learning algorithms. ANVIL also provides a range of tools for detailed evaluation and comparison of methods on high-quality datasets [

49].

Community Challenges and Collaboration

Blind prediction challenges, inspired by CASP [

50], CACHE [

51], and SAMPL [

52], will be a central component of OpenADMET. These challenges evaluate predictive models using unseen, high-quality data, promote open-source methods and reproducibility, and maintain a shared scoreboard to track progress across academia and industry. Rather than viewing these challenges just as competitions, OpenADMET will use them as a catalyst to advance the current state of ADMET modeling. After each challenge, we will convene the community to discuss the most effective approaches and collaborate on computational and experimental strategies that can lead to further improvements.

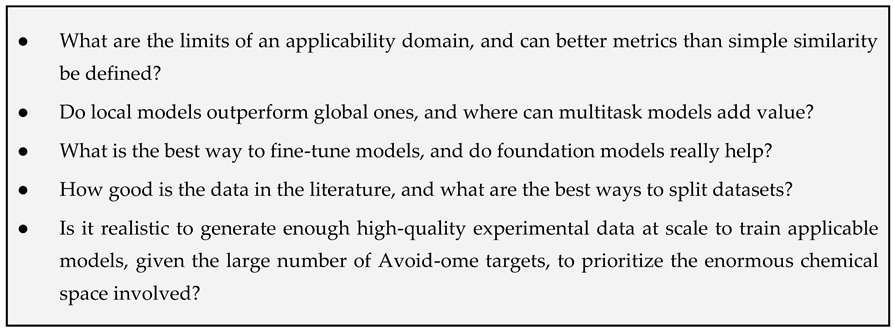

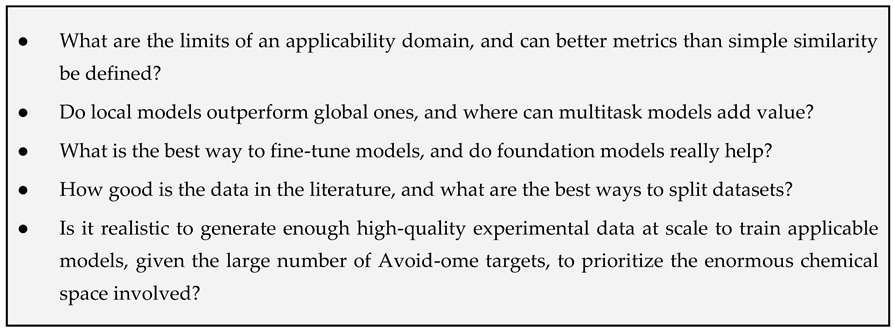

The shortage of high-quality datasets has limited the field’s ability to investigate key issues related to the application of ML models in ADMET prediction and drug discovery overall. Blind challenges, along with ML model development efforts within OpenADMET, provide a unique opportunity to explore fundamental questions about machine learning in ADMET; a sample of these questions is in Box 1. OpenADMET will generate the data needed to systematically study these questions.

Future Perspective: From Avoidance to Design

The next decade of drug discovery will require shifting from ignoring Avoid-ome liabilities until late in drug development to embracing them early. Several broader questions will shape the field, especially as new modalities emerge. Are higher molecular weight molecules less prone to metabolism and transport because nature has not evolved to catch them? How specific are transporters – can molecules with structures quite different from the known substrates be transported? What is the Avoid-ome for antisense oligonucleotides? For proteins and peptides, at what molecular weight threshold does the body treat a drug as a peptide versus a protein? In each case, such questions can be addressed only by building and testing appropriate libraries.

There are also practical considerations about how to embed Avoid-ome data into the discovery pipeline. For example, at what stage, hit-to-lead, lead optimization, or clinical candidate selection, should Avoid-ome predictive models or experiments be used either to triage ideas or to assist with multi-parameter optimization? Second, how can detailed Avoid-ome knowledge enable the exploitation of these anti-targets for the design of soft drugs or prodrugs? Third, can Avoid-ome efforts ever address unpredictable, rare toxicities like idiosyncratic DILI, which often only emerge late in Phase 3? Finally, how can interactions with “carrier” proteins such as serum albumin be optimized to extend drug half-life?

Conclusions

Understanding and navigating the Avoid-ome is the central universal challenge of modern drug discovery. By creating open, structural, and mechanistic datasets and benchmarking predictive models through blind challenges, OpenADMET provides the foundation for a new era of rational drug design. The best way to increase the effectiveness of drug discovery in the coming decade is to stop avoiding the Avoid-ome and instead study it directly.

References

- Segall, M. D. Multi-Parameter Optimization: Identifying High Quality Compounds with a Balance of Properties. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18 (9), 1292–1310.

- Murcko, M.A. What Makes a Great Medicinal Chemist? A Personal Perspective. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 7419–7424. [CrossRef]

- Kola, I.; Landis, J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 711–715. [CrossRef]

- Munson, M.; Lieberman, H.; Tserlin, E.; Rocnik, J.; Ge, J.; Fitzgerald, M.; Patel, V.; Garcia-Echeverria, C. Lead optimization attrition analysis (LOAA): a novel and general methodology for medicinal chemistry. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 978–987. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.A.; Kavanagh, S.L.; Mellor, H.R.; Pollard, C.E.; Robinson, S.; Platz, S.J. Reducing attrition in drug development: smart loading preclinical safety assessment. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 341–347. [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.C.G.; Sousa, G.H.M.; Calil, R.L.; Trossini, G.H.G. Absorption matters: A closer look at popular oral bioavailability rules for drug approvals. Mol. Informatics 2023, 42. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, K.V.; Gunsalus, L.M.; Keiser, M.J. Learning Molecular Representations for Medicinal Chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 8705–8722. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J.S.; Murcko, M.A. Structure is beauty, but not always truth. Cell 2024, 187, 517–520. [CrossRef]

- Bowes, J.; Brown, A.J.; Hamon, J.; Jarolimek, W.; Sridhar, A.; Waldron, G.; Whitebread, S. Reducing safety-related drug attrition: the use of in vitro pharmacological profiling. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 909–922. [CrossRef]

- Whitebread, S.; Dumotier, B.; Armstrong, D.; Fekete, A.; Chen, S.; Hartmann, A.; Muller, P.Y.; Urban, L. Secondary pharmacology: screening and interpretation of off-target activities – focus on translation. Drug Discov. Today 2016, 21, 1232–1242. [CrossRef]

- Denisov, I.G.; Makris, T.M.; Sligar, S.G.; Schlichting, I. Structure and Chemistry of Cytochrome P450. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2253–2278. [CrossRef]

- Manevski, N.; King, L.; Pitt, W.R.; Lecomte, F.; Toselli, F. Metabolism by Aldehyde Oxidase: Drug Design and Complementary Approaches to Challenges in Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 10955–10994. [CrossRef]

- Oda, S.; Fukami, T.; Yokoi, T.; Nakajima, M. A comprehensive review of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase and esterases for drug development. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2015, 30, 30–51. [CrossRef]

- Aloke, C.; Onisuru, O.O.; Achilonu, I. Glutathione S-transferase: A versatile and dynamic enzyme. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 734, 150774. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Tampé, R. Structural and Mechanistic Principles of ABC Transporters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2020, 89, 605–636. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Yee, S.W.; Kim, R.B.; Giacomini, K.M. SLC transporters as therapeutic targets: emerging opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 543–560. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.; Qaiser, H.; Tariq, S.; Khalid, A.; Makeen, H.A.; Alhazmi, H.A.; Ul-Haq, Z. Unraveling the versatility of human serum albumin – A comprehensive review of its biological significance and therapeutic potential. Curr. Res. Struct. Biol. 2023, 6, 100114. [CrossRef]

- Ramanjulu, J.M.; Williams, S.P.; Lakdawala, A.S.; DeMartino, M.P.; Lan, Y.; Marquis, R.W. Overcoming the Pregnane X Receptor Liability: Rational Design to Eliminate PXR-Mediated CYP Induction. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 1396–1404. [CrossRef]

- Willson, T.M.; Kliewer, S.A. Pxr, car and drug metabolism. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002, 1, 259–266. [CrossRef]

- Garrido, A.; Lepailleur, A.; Mignani, S.M.; Dallemagne, P.; Rochais, C. hERG toxicity assessment: Useful guidelines for drug design. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 195, 112290. [CrossRef]

- Abriel, H. Cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 and interacting proteins: Physiology and pathophysiology. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010, 48, 2–11. [CrossRef]

- Lipscombe, D.; Helton, T. D.; Xu, W. L-Type Calcium Channels: The Low down. J. Neurophysiol. 2004, 92 (5), 2633–2641.

- Robinson, K.; Tiriveedhi, V. Perplexing Role of P-Glycoprotein in Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 265. [CrossRef]

- Hsia, D.S.; Grove, O.; Cefalu, W.T. An update on sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2017, 24, 73–79. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.; Hei, R.; Li, X.; Cai, H.; Wu, X.; Zheng, Q.; Cai, C. CDK Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy, an Overview of Recent Development. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11 (5), 1913–1935.

- Chen, J.; Chung, Y.; Tynan, J.; Cheng, C.; Yang, S.; Cheng, A.C. Data Scaling and Generalization Insights for Medicinal Chemistry Deep Learning Models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 5887–5898. [CrossRef]

- Gaulton, A.; Bellis, L.J.; Bento, A.P.; Chambers, J.; Davies, M.; Hersey, A.; Light, Y.; McGlinchey, S.; Michalovich, D.; Al-Lazikani, B.; et al. ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D1100–D1107. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Fu, T.; Gao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Roohani, Y.; Leskovec, J.; Coley, C.W.; Xiao, C.; Sun, J.; Zitnik, M. Artificial intelligence foundation for therapeutic science. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022, 18, 1033–1036. [CrossRef]

- Landrum, G. A.; Riniker, S. Combining IC50 or Ki Values from Different Sources Is a Source of Significant Noise. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64 (5), 1560–1567.

- Matreyek, K.A.; Starita, L.M.; Stephany, J.J.; Martin, B.; Chiasson, M.A.; Gray, V.E.; Kircher, M.; Khechaduri, A.; Dines, J.N.; Hause, R.J.; et al. Multiplex assessment of protein variant abundance by massively parallel sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 874–882. [CrossRef]

- Musther, H.; Olivares-Morales, A.; Hatley, O.J.; Liu, B.; Hodjegan, A.R. Animal versus human oral drug bioavailability: Do they correlate? Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 57, 280–291. [CrossRef]

- Heyndrickx, W.; Mervin, L.; Morawietz, T.; Sturm, N.; Friedrich, L.; Zalewski, A.; Pentina, A.; Humbeck, L.; Oldenhof, M.; Niwayama, R.; et al. MELLODDY: Cross-pharma Federated Learning at Unprecedented Scale Unlocks Benefits in QSAR without Compromising Proprietary Information. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 64, 2331–2344. [CrossRef]

- Reker, D. Practical considerations for active machine learning in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today: Technol. 2019, 32-33, 73–79. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Jiao, B.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, W.; Ouyang, Z. Miniaturization of Mass Spectrometry Systems: An Overview of Recent Advancements and a Perspective on Future Directions. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 9111–9125. [CrossRef]

- Kain, S.R.; Ganguly, S. Overview of Genetic Reporter Systems. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2001, 68, 9.6.1–9.6.12. [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.M.; Jajoo, R.; Cancilla, D.; Lubock, N.B.; Wang, J.; Satyadi, M.; Chong, R.; de March, C.; Bloom, J.S.; Matsunami, H.; et al. A Scalable, Multiplexed Assay for Decoding GPCR-Ligand Interactions with RNA Sequencing. Cell Syst. 2019, 8, 254–260.e6. [CrossRef]

- Thouta, S.; Lo, G.; Grajauskas, L.; Claydon, T. Investigating the state dependence of drug binding in hERG channels using a trapped-open channel phenotype. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4962. [CrossRef]

- Eagling, V.A.; Tjia, J.F.; Back, D.J. Differential selectivity of cytochrome P450 inhibitors against probe substrates in human and rat liver microsomes. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1998, 45, 107–114. [CrossRef]

- Guha, R.; Van Drie, J. H. Structure--Activity Landscape Index: Identifying and Quantifying Activity Cliffs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2008, 48 (3), 646–658.

- Kuan, J.; Radaeva, M.; Avenido, A.; Cherkasov, A.; Gentile, F. Keeping pace with the explosive growth of chemical libraries with structure-based virtual screening. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hendrick, C.E.; Jorgensen, J.R.; Chaudhry, C.; Strambeanu, I.I.; Brazeau, J.-F.; Schiffer, J.; Shi, Z.; Venable, J.D.; Wolkenberg, S.E. Direct-to-Biology Accelerates PROTAC Synthesis and the Evaluation of Linker Effects on Permeability and Degradation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 1182–1190. [CrossRef]

- Stoll, F.; Göller, A.H.; Hillisch, A. Utility of protein structures in overcoming ADMET-related issues of drug-like compounds. Drug Discov. Today 2011, 16, 530–538. [CrossRef]

- A Wankowicz, S.; Ravikumar, A.; Sharma, S.; Riley, B.; Raju, A.; Hogan, D.W.; Flowers, J.; Bedem, H.v.D.; A Keedy, D.; Fraser, J.S. Automated multiconformer model building for X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM. eLife 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Flowers, J.; Echols, N.; Correy, G.J.; Jaishankar, P.; Togo, T.; Renslo, A.R.; Bedem, H.v.D.; Fraser, J.S.; A Wankowicz, S. Expanding automated multiconformer ligand modeling to macrocycles and fragments. eLife 2025, 14. [CrossRef]

- Krojer, T.; Fraser, J.S.; von Delft, F. Discovery of allosteric binding sites by crystallographic fragment screening. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2020, 65, 209–216. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Mailhot, O.; Glenn, I.S.; Vigneron, S.F.; Bassim, V.; Xu, X.; Fonseca-Valencia, K.; Smith, M.S.; Radchenko, D.S.; Fraser, J.S.; et al. The impact of library size and scale of testing on virtual screening. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2025, 21, 1039–1045. [CrossRef]

- E Watkins, R.; Noble, S.M.; Redinbo, M.R. Structural insights into the promiscuity and function of the human pregnane X receptor.. 2002, 5, 150–8.

- krinjar, P.; Eberhardt, J.; Tauriello, G.; Schwede, T.; Durairaj, J. Have Protein-Ligand Cofolding Methods Moved beyond Memorisation? bioRxiv, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ash, J.R.; Wognum, C.; Rodríguez-Pérez, R.; Aldeghi, M.; Cheng, A.C.; Clevert, D.-A.; Engkvist, O.; Fang, C.; Price, D.J.; Hughes-Oliver, J.M.; et al. Practically Significant Method Comparison Protocols for Machine Learning in Small Molecule Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2025, 65, 9398–9411. [CrossRef]

- Gilson, M.K.; Eberhardt, J.; Škrinjar, P.; Durairaj, J.; Robin, X.; Kryshtafovych, A. Assessment of Pharmaceutical Protein–Ligand Pose and Affinity Predictions in CASP16. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ackloo, S.; Al-Awar, R.; Amaro, R.E.; Arrowsmith, C.H.; Azevedo, H.; Batey, R.A.; Bengio, Y.; Betz, U.A.K.; Bologa, C.G.; Chodera, J.D.; et al. CACHE (Critical Assessment of Computational Hit-finding Experiments): A public–private partnership benchmarking initiative to enable the development of computational methods for hit-finding. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 287–295. [CrossRef]

- Amezcua, M.; Setiadi, J.; Ge, Y.; Mobley, D.L. An overview of the SAMPL8 host–guest binding challenge. J. Comput. Mol. Des. 2022, 36, 707–734. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).