1. Introduction

Influenza A virus (IAV) based vectors have emerged as versatile platforms for vaccination [

1,

2] and targeted delivery of immunomodulatory molecules [

3]. In addition to their natural tropism for the respiratory tract, IAVs can enter any cell expressing sialic-acid receptors, including tumor cells, which broadens their applicability for parenteral delivery and intratumoral administration. Their well-defined genetics, intrinsic innate adjuvanticity, and capacity to express foreign sequences have made IAV an attractive backbone for recombinant vector design [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Since the first demonstrations that foreign genes can be stably expressed from modified NS segments [

7], IAV-based vectors have evolved into powerful tools for antigen delivery and local immunomodulation. Early work by Kittel et al. showed that the NS segment can express cytokines such as IL-2 without abolishing viral replication [

3], while studies by Ferko and colleagues demonstrated that NS1-modified strains support robust heterologous gene expression and exhibit strong interferon-dependent self-adjuvanting activity [

8]. Importantly, IL-2 expressing IAV vectors enhanced antiviral immunity even in aged mice, partially compensating for immunosenescence [

9].

Influenza viruses naturally suppress innate and adaptive immunity through the interferon-antagonist NS1 protein [

4,

10]. Therefore, NS1-deleted or truncated vectors were developed; these viruses lack anti-interferon activity and therefore display markedly increased immunogenicity, including enhanced dendritic-cell activation and efficient CD8⁺ T-cell priming [

11]. NS1-deficient IAVs also exhibit notable oncolytic properties, replicating selectively but often non-productively in interferon-defective tumor cells [

12,

13]. However, because their replication in tumors is insufficient for effective intratumoral amplification, additional boosting approaches such as co-expression of cytokines or chemokines or repeated vector administration - may be required to maximize their antitumor efficacy.

Interferon-inducible chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 play a central role in antiviral and antitumor immunity by engaging the CXCR3 receptor on activated CD8⁺ T cells, NK cells, γδ T cells, and Th1 CD4⁺ lymphocytes [

14,

15,

16]. This axis directs effector-cell trafficking to inflamed tissues, promotes Th1 polarization, and enhances clearance of infected or malignant cells. Elevated CXCR3-ligand expression during respiratory infection correlates with increased CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration and improved viral control [

17]. Beyond attracting effector cells, CXCR3 ligands modulate early adaptive immunity by di-recting antigen-experienced CXCR3⁺ T cells to draining lymph nodes, while concurrently recruiting inflammatory dendritic cells and Th1 helpers. Thus, inclusion of CXCR3 lig-ands within NS1-modified IAV vectors may provide a strong additional adjuvant effect, enhancing both magnitude and breadth of T-cell immunity.

Viral vectors have been widely used to achieve localized chemokine expression in vivo. Replication-deficient adenoviral CXCL10 constructs, such as AdCXCL10, induce rapid and sustained infiltration of CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells, greatly exceeding control vectors [

18]. Local CXCL10 expression creates a strong CXCR3-dependent gradient, elevates inflammatory cytokines, and supports robust T-cell activation. CXCL10-armed vectors have been applied in cancer models to improve T-cell trafficking, enhance intratumoral cytotoxicity, and overcome immune suppression [

19,

20]. In glioma, vector-mediated CXCL9/10 delivery sensitizes tumors to immunotherapy by promoting T-cell infiltration and improving responses to checkpoint blockade [

21]. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that localized expression of CXCR3 ligands can substantially amplify T-cell responses and impose a pronounced Th1-skewed immune profile at the site of vector activity.

In this study, we explored the feasibility of constructing NS1-truncated influenza A virus vectors designed to express CXCL9, CXCL10, or CXCL11. A recombinant virus expressing CXCL10 was successfully rescued and exhibited stable chemokine expression. In contrast, repeated attempts to rescue the CXCL9-expressing virus were unsuccessful, suggesting that CXCL9 may interfere with early stages of the influenza replication cycle. Consequently, our subsequent analysis was focused on the CXCL10-expressing vector, including evaluation of its replication properties, chemokine production, and capacity to modulate the development of adaptive immune responses.

2. Materials and Methods

Cells

The Vero (ATCC #CCL-81, USA) and MDCK (#FR-58; IRR, USA) cell lines were used. Vero cells were cultivated in OptiPro medium (Gibco, USA) with 2% GlutaMax (Gibco, USA). MDCK cells were cultured in AlphaMEM medium (Biolot, Russia) supplemented with 10% SC-biol fetal serum (Biolot, Russia).

Generation of Recombinant Virus

Recombinant influenza virus A/PR8/NS124-CXCL10 (H1N1) based on the A/PR/8/1934 strain with the NS124-CXCL10 chimeric protein obtained by reverse genetics [

22]. Vero cells were transfected with a set of 8 bidirectional plasmids encoding influenza virus genes using the Nucleofector II (Amaxa) and the Nucleofection Kit V reagent kit (Lonza #VCA-1003, Switzerland). After transfection cells were incubated in a medium with 1 μg/ml TPCK-trypsin (Sigma) until the development of a specific cytopathic effect and then were propagated in 10-12-day-old developing chicken embryos (CE) (Sinyavinskaya Poultry Farm, Russia).

The infectious activity was assessed by the limiting dilution assay in MDCK cells and in the CE. The virus dilutions for infection of MDCK cells were prepared in the AlphaMEM medium with 1% of antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco, USA) and TPCK-trypsin 1 μg/ml. Dilutions for infecting CE were prepared in DPBS buffer (Biolot, Russia) with 1% of antibiotic-antimycotic. The 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) or egg infectious dose (EID50) was calculated according to the Reed and Mench method and expressed in lg [

23].

Animals

Female BALB/c and C57Bl/6 mice (16–18 g) were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Nursery Pushchino (Shemyakin and Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry RAS, Moscow, Russia) or from state facility “RAPPOLOVO” laboratory animals’ nursery of the Russian academy of medical sciences. All procedures involving animals were performed in compliance with international regulations (Directive 2010/63/EU) and were approved by the local Bioethics Committee of the Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza.

Viral Infectious Activity Analysis

Viral shedding was assessed on days 3 and 5 following immunization. The mice were euthanized, and their lungs were collected and homogenized using a TissueLyser II bead homogenizer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The viral titters were determined by infecting MDCK cells with the tissue homogenates, followed by hemagglutination assays using a 0.5% suspension of chicken red blood cells. The tissue infectivity was quantified as the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50), calculated with the Reed and Muench method [

23], and expressed as lg TCID50 per milliliter (lg TCID50/mL).

Immunization

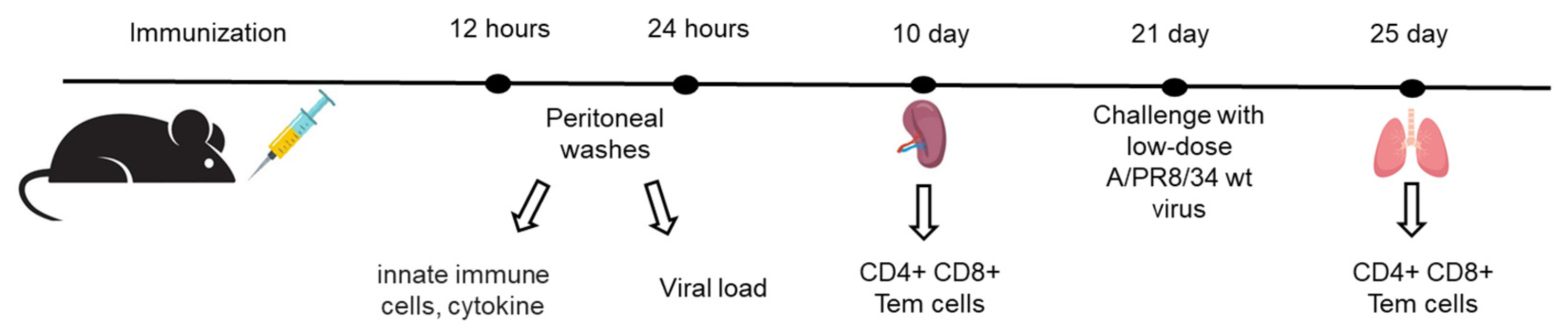

Female C57BL/6 mice (16–18 g) received intraperitoneal immunization with either the NS124_SS_CXCL10 strain or the NS124 empty-vector control at a dose of 7 lg EID50 per mouse. To evaluate the dynamics of innate immune cell recruitment, peritoneal exudate cells were collected after 12 and 24 hours post immunization (Figure 3). The adaptive immune response was assessed by harvesting spleens 10 days after immunization. To examine mucosal T-cell responses, mice were challenged with A/PR8 wild-type virus (3 lg EID50 per mouse) 21 days post-immunization, and lungs were collected 3 days after challenge.

Real-Time PCR for Detection of Influenza A

Total RNA was isolated from homogenized mouse lungs using RNA Isolation Kit (Biolabmix, Russia). Peritoneal washes were processed without prior isolation of total RNA from the samples. Reaction was performed using the BioMaster RT-PCR-Extra (2x) reagent kit (Biolabmix, Russia) and the CDC-recommended specific for influenza A primers InfA-F (GACCRATCCTGTCACCTCTGAC), InfA-R (AGGGCATTYTGGACAAAKCGTCTA) and InfA-P oligonucleotide probe (TGCAGTCCTCGCTCACTGGGCACG) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cytokine Production Analysis

Cytokine concentrations in peritoneal washes were determined using the LEGENDplex multiplex system (Biolegend, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Leukocytes Isolation and Stimulation

Briefly, lung, spleen and peritoneal washes leukocytes were harvested from mice [

24] and mechanically dissociated. Lung tissue was additionally digested with collagenase/DNase (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA). Cells were filtered through 70 µm strainers, and erythrocytes were lysed using RBC lysis buffer (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Prepared single-cell suspensions were seeded at a density of 1 × 10

6 cells per well in 96-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). For intracellular cytokine staining (ICS), cells were stimulated with 5 µg/mL influenza A/PR8 virus or with the NP

366–374 peptide (Verta Ltd., Saint Petersburg, Russia) in the presence of brefeldin A (BioLegend).

Flow Cytometry

To detect CD4+/CD8+ Tem cells that produce cytokines, cells were stained with CD8-PC7, CD4-PC5.5, CD62L-APC-A750, CD44-KO525, IFNγ-FITC, TNFα-PB450, and IL2-PE antibodies (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) using the Fixation and Permeabilization Solution reagent kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Phenotyping of innate immune cells was performed using a panel of fluorescently labeled antibodies: CD11b-PE/Cy7, CD11c-PE, MHCII-Alexa Fluor 488, Ly6G-PerCP-Cy5.5, Ly6C-Alexa Fluor 700, CD103-BV605, CD45-APC/Cy7, CD64-BV421, and CD24-BV510 (all from BioLegend, USA). The following cell populations were identified based on established surface marker expression: neutrophils (SSChiCD45+Ly6G+), macrophages (CD45+MHCII+CD64+CD11c/CD11b+), monocytes (CD45+MHCII-CD64+CD11c/CD11b+) and dendritic cells (CD45+MHCII+CD64-CD24+CD11c/CD11b+CD103+/CD103-). Data was acquired on a CytoFlex flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Bray, CA, USA) and analyzed using Kaluza Analysis 2.2 software (Beckman Coulter, Bray, CA, USA).

Challenge with Influenza Viruses

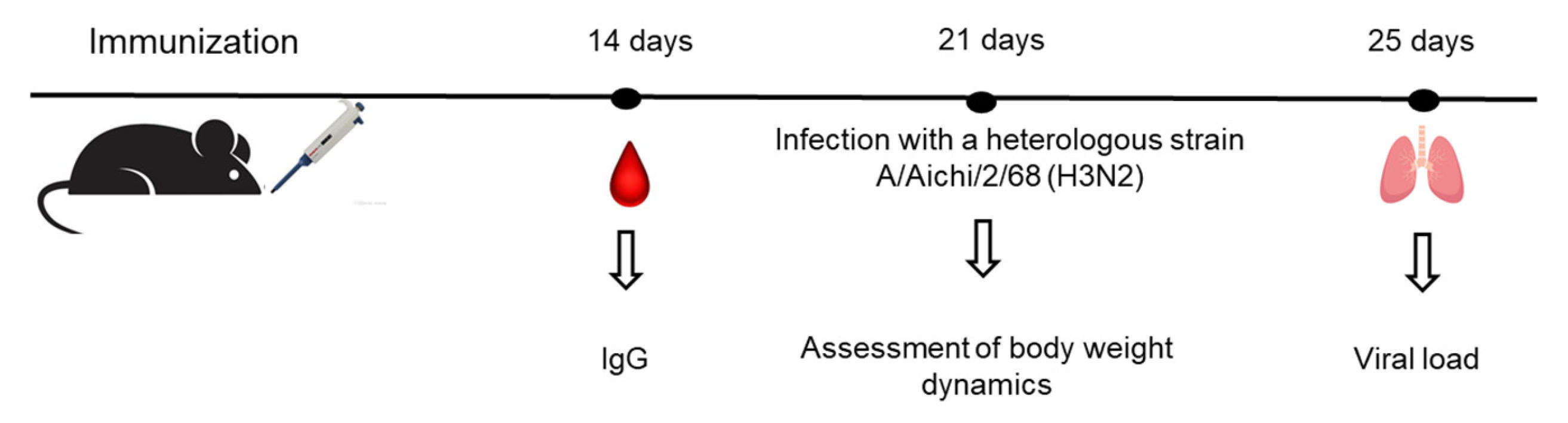

For lethal challenge experiments, mouse-adapted influenza strains A/Aichi/2/68 (H3N2) was used in a dose of 10 LD50. 21 days after the administration (Figure 12), mice were challenged intranasally (i.n.) under inhalation anesthesia. The animals were monitored for weight loss daily for five days. On the fifth day after infection, lungs were collected to measure the viral load.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

To measure influenza-specific antibodies, ELISA was performed. 96-well plates (NuncMaxisorp, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were coated with purified A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 virus at a concentration of 2 µg/mL in DPBS. HRP-conjugated antibodies (Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA) were used for detection, and the reaction was visualized with TMB substrate (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), followed by stopping with 1M H2SO4. Absorbance was measured at 450/620 nm using a Multiskan SkyHigh microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 10.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way or two-way ANOVA or unpaired t test.

3. Results

3.1. Construction of Influenza Vectors Expressing CXCR3 Receptor Ligands

To generate influenza vectors expressing the chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, we used the A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) strain (PR8) carrying a truncated NS1 protein of 124 amino acids (PR8/NS124). To enable chemokine expression, we employed the overlapping stop/start codon strategy (TAATG) described by Kittel et al. for the expression of human IL-2 [

3]. Briefly, the upstream stop codon terminated translation of the NS1 protein to 124 amino acid residues, while the downstream AUG initiated translation of the chemokine open reading frame, including its native signal peptide.

Recombinant influenza viruses were rescued by plasmid transfection of Vero + MDCK cells and subsequently amplified in 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs. The CXCL9-expressing construct could not be rescued despite multiple attempts. In contrast, the CXCL10- and CXCL11-expressing vectors were successfully propagated in the allantoic cavity, reaching hemagglutination titers of 1:64 and 1:32 respectively.

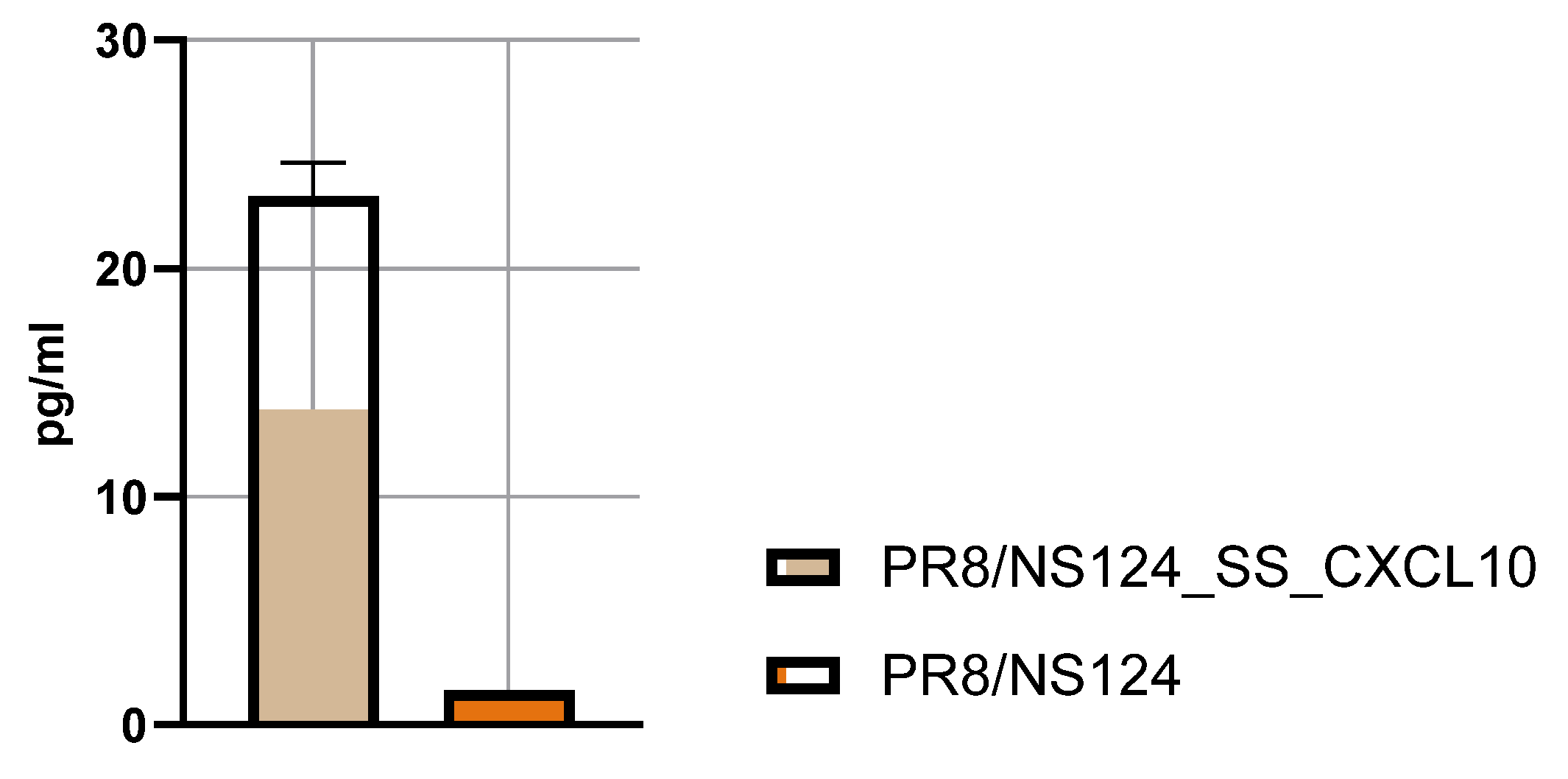

Chemokine expression in the allantoic fluid was quantified by ELISA. Embryonated chicken eggs were infected with 2 × 10⁵ PFU per egg of the CXCL10 or CXCL11 vector. Allantoic fluids were harvested 48 hours post-infection and analyzed using the LEGEND MAX™ Human CXCL10 (IP-10) and CXCL11 ELISA Kit (BioLegend, USA). The results demonstrated robust production of CXCL10 (23.5 ± 3.7 pg/ml;

Figure 1), confirming efficient replication and transgene expression. In contrast, CXCL11 was not detected in the allantoic fluid (date not shown). Consequently, subsequent experiments were performed exclusively with the PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 vector.

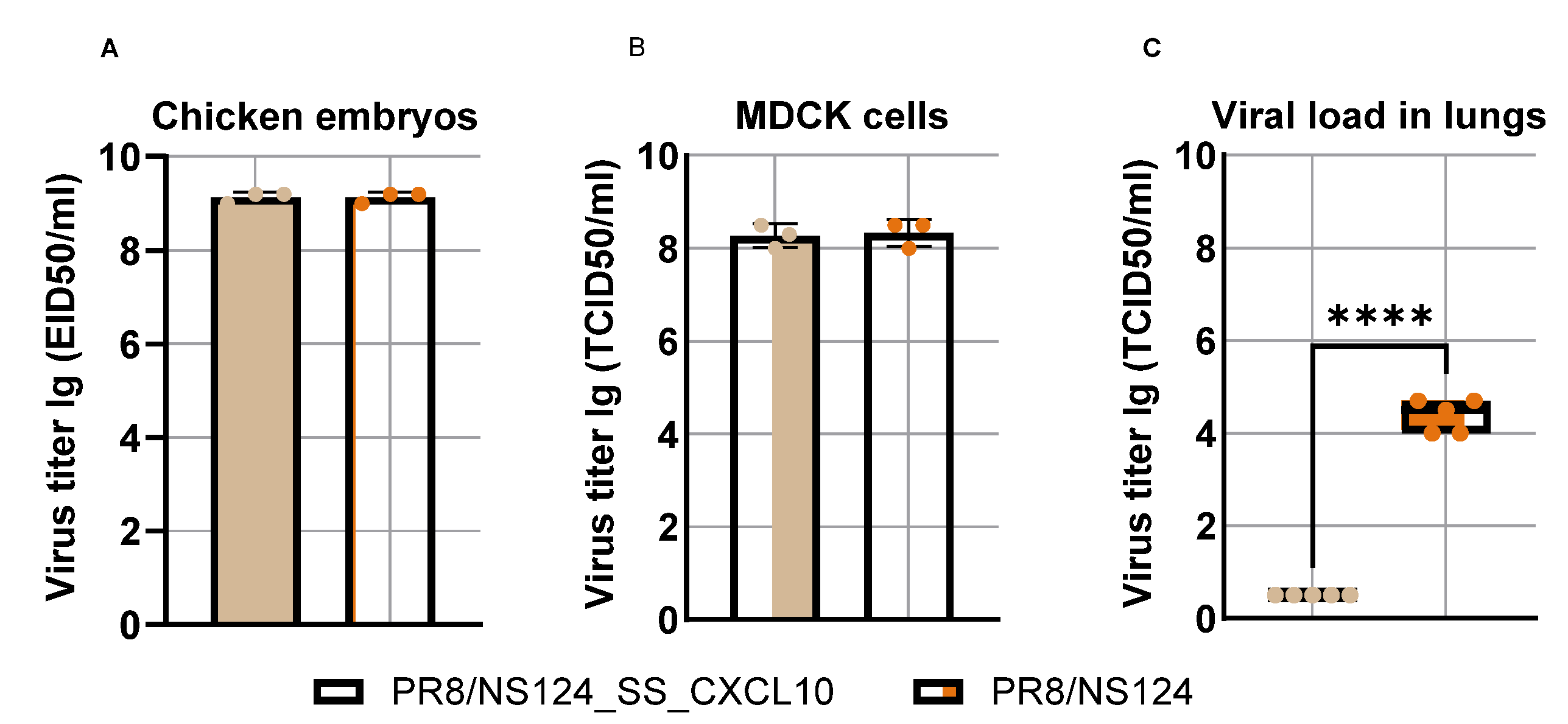

3.2. Attenuation of the PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 Vector in Mice

Although the PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 vector replicated efficiently in embryonated chicken eggs and MDCK cells, reaching titers of up to 9.0 and 8.0 lg, respectively, comparable to those of the parental PR8/NS124 virus (empty vector control) (

Figure 2), its replication in mouse lungs was markedly attenuated compared with the control virus.

Upon mouse intranasal immunization (Balb/c or C57 BL/6), the PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 vector exhibited a high degree of attenuation, displaying an almost replication-defective phenotype in vivo, whereas the parental PR8/NS124 virus replicated in the lungs to titers of 4,5

+ 0,4 lg (

Figure 2). Thus, while the vector replicated efficiently in eggs and MDCK cells systems that lack adaptive T-cell immunity its replication in mice was dramatically reduced, suggesting that CXCL10 expression contributed to immune-mediated restriction of viral replication in vivo.

3.3. Innate Immune Response

Because replication of the chemokine-expressing vector and the control NS124 virus in the lungs differed by more than 1,000-fold, their comparative immunogenicity was assessed following intraperitoneal administration, a route in which differences in replication are expected to be minimal. C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 500 μl of either PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the empty PR8/NS124 vector at a dose of 7 lg EID50 per mouse; control animals received PBS. To analyze the kinetics of innate immune cell recruitment, peritoneal exudate cells were collected 12- and 24-hour post-immunization (

Figure 3).

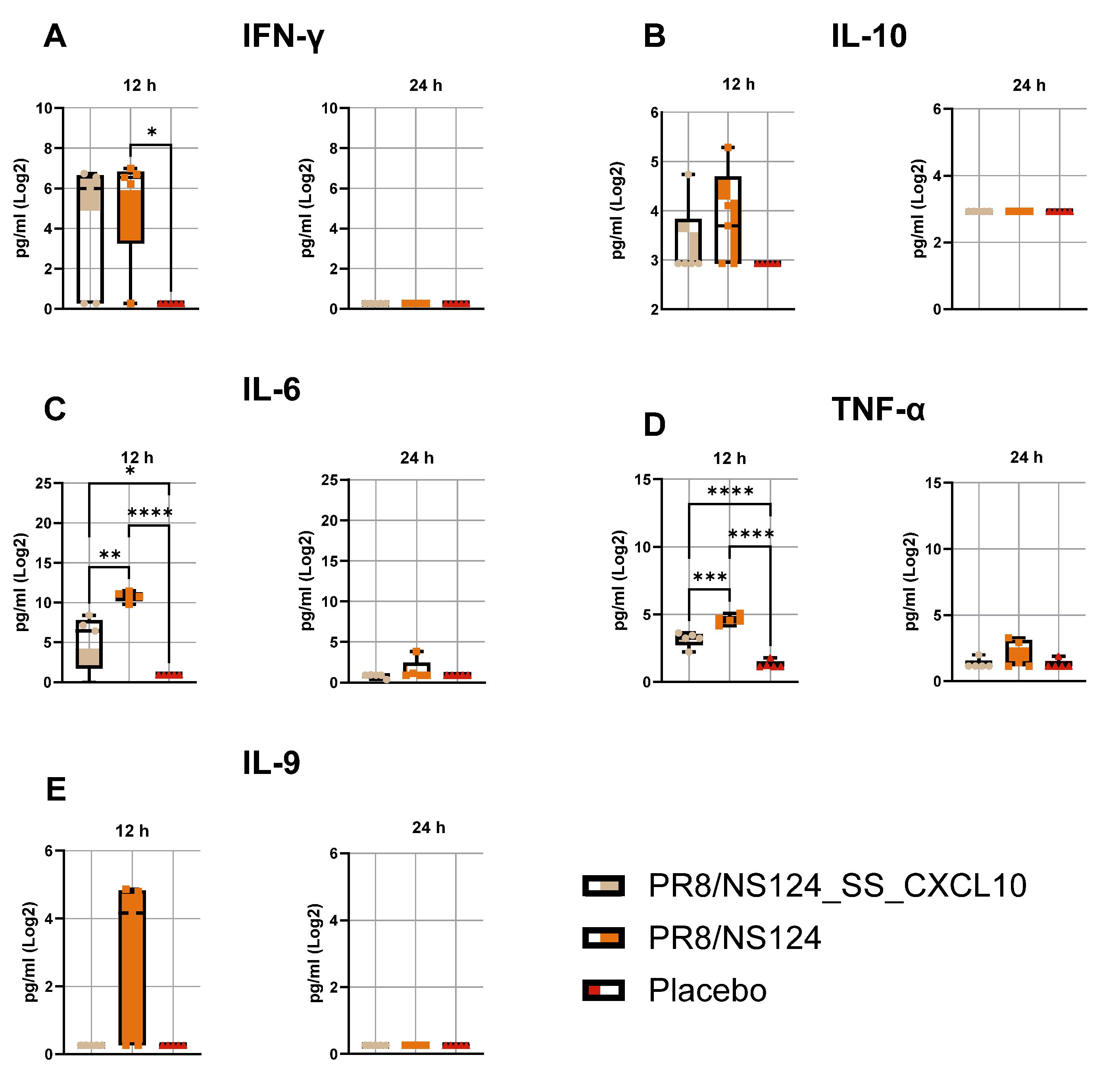

Both viral vectors provoked a rapid inflammatory response, characterized by elevated cytokine levels at 12 hours that declined by 24 hours (

Figure 4). The empty NS124 vector induced the highest levels of IFN-γ, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-9, consistent with strong virus-driven activation of innate immunity. In contrast, the CXCL10-expressing vector elicited slightly lower or comparable cytokine levels, suggesting that CXCL10 expression did not amplify but rather moderated the acute inflammatory response.

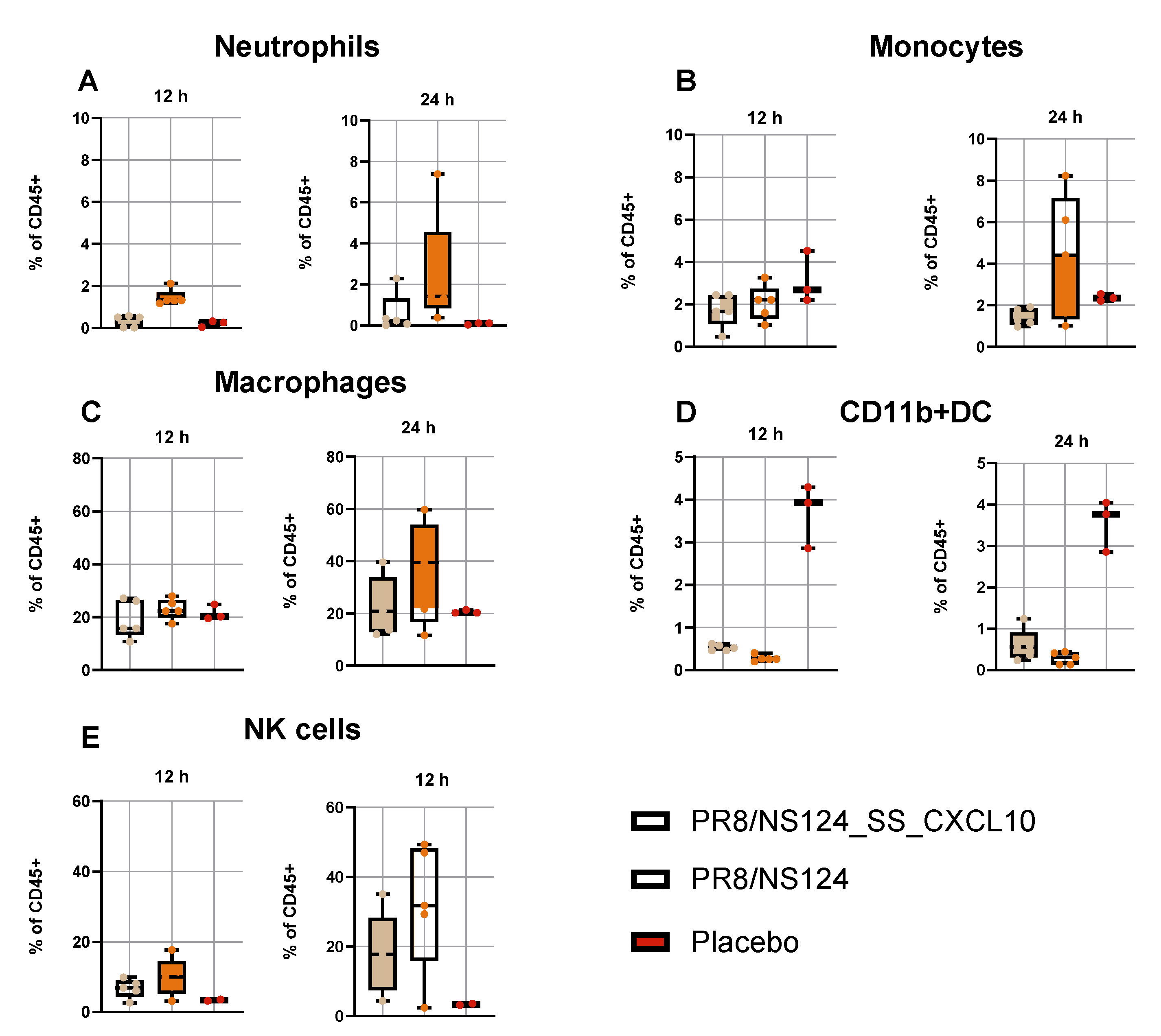

Analysis of peritoneal exudate cells confirmed robust innate recruitment following infection with both vectors (

Figure 5). Across all cell populations examined, the empty NS124 vector induced higher frequencies of neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and NK cells than the CXCL10-expressing virus, in line with the stronger cytokine induction. The proportion of CD11b⁺ dendritic cells remained low and variable in all groups.

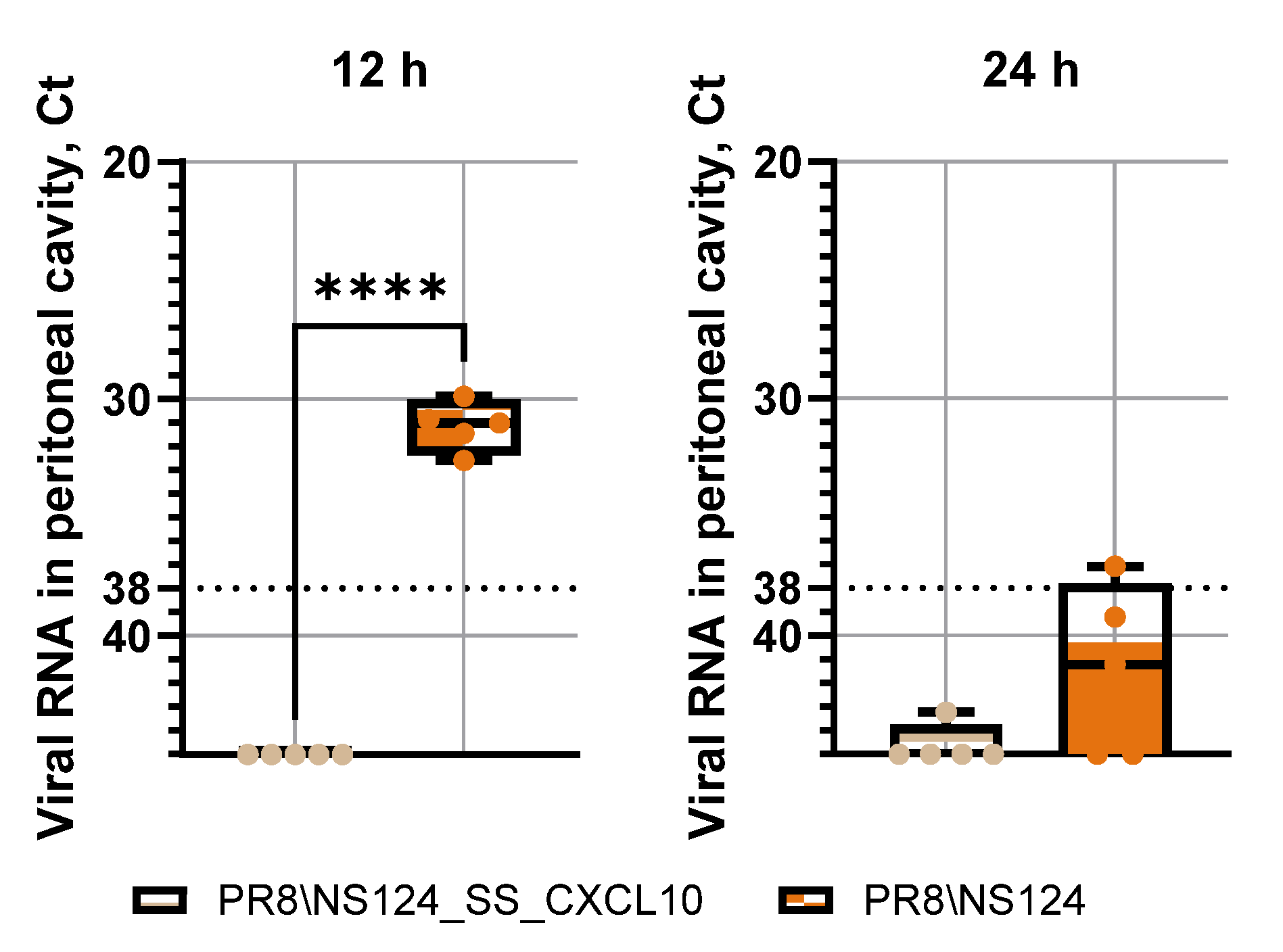

To determine whether reduced viral replication might explain the diminished innate immune response of the CXCL10-expressing vector, we evaluated viral RNA levels in the peritoneal cavity. Quantitative PCR analysis demonstrated that replication of PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 was markedly attenuated compared with the empty vector (

Figure 6). At 12 hours post-inoculation, viral RNA levels were significantly lower for the CXCL10 vector, indicating absence of productive infection; by 24 hours, viral RNA for both vectors were close to the detection threshold. This attenuation likely reflects early induction of nonspecific antiviral response triggered by CXCL10 expression. Taken together, these results indicate that intraperitoneal administration of NS124 influenza vector elicits a potent innate immune response primarily driven by viral infection itself, whereas CXCL10 expression limits viral replication and may slightly temper the magnitude of the early inflammatory reaction at the time points examined.

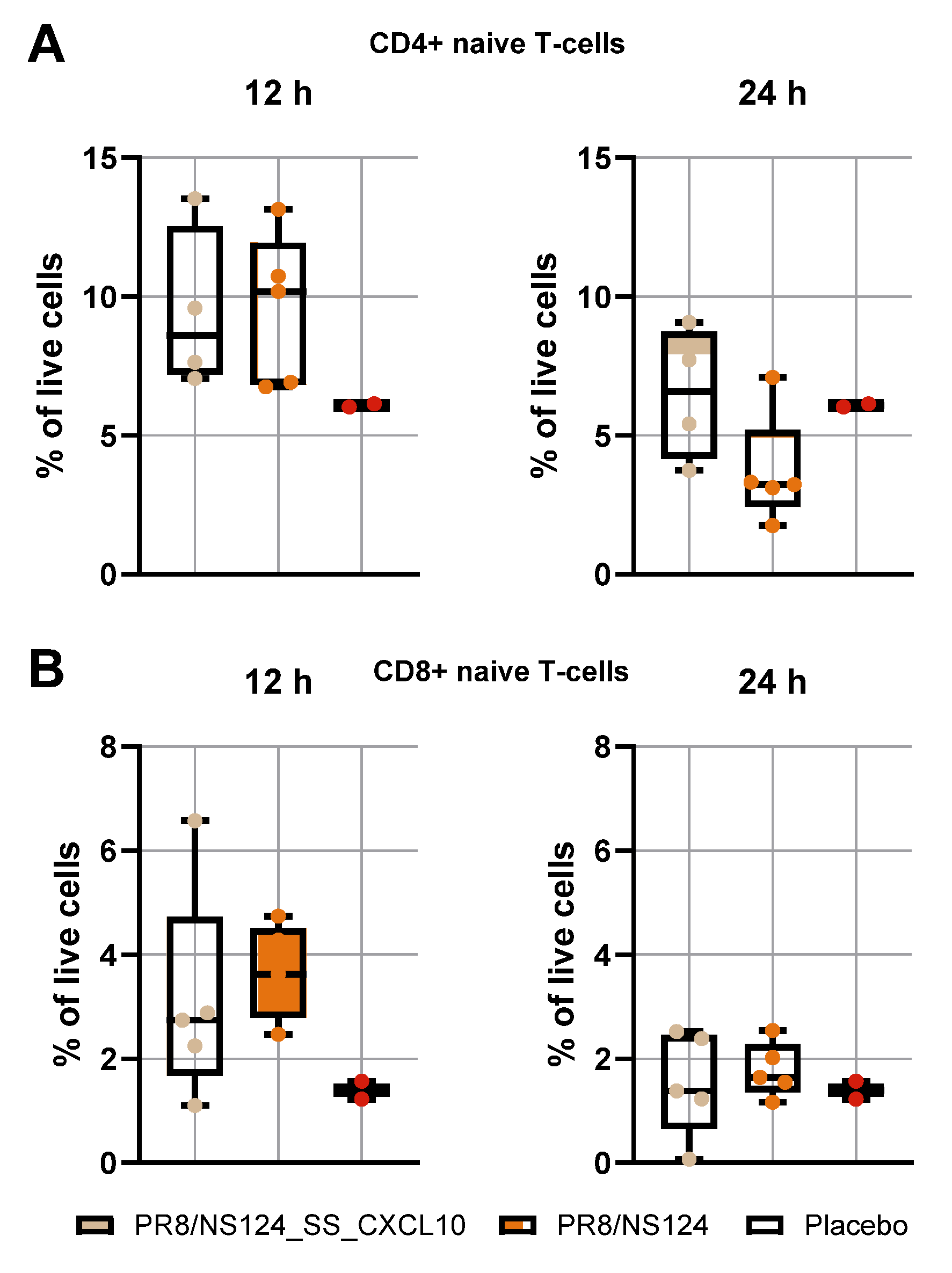

3.3. Early Naïve CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T-Cell Recruitment

We examined naïve CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration in the peritoneal cavity at 12- and 24-hours post-immunization (

Figure 7). Both viral vectors induced a comparable early influx of CD4⁺ T cells at 12 hours (9.5 ± 2.9% vs. 9.5 ± 2.7%; placebo: 6.1 ± 0.1%). This indicates that early lymphocyte recruitment is primarily driven by the initial viral exposure and local sensing of incoming particles rather than by subsequent viral amplification.

By 24 hours, CD4⁺ T-cell frequencies declined in both groups, but the decrease was less pronounced in animals receiving the CXCL10-expressing vector (6.4 ± 2.4% vs. 3.7 ± 1.9%), suggesting a minor CXCL10-mediated retention effect. CD8⁺ T-cell frequencies followed the same pattern: similar levels at 12 hours for both vectors (3.1 ± 2.0% vs. 3.6 ± 0.9%; placebo: 1.3 ± 0.3%) and minimal changes by 24 hours, consistent with the delayed kinetics of cytotoxic T-cell activation. Together, these results show that although the CXCL10 vector replicates less efficiently in the peritoneal cavity, early lymphocyte influx is largely replication-independent and only modestly influenced by CXCL10 expression at the early time points examined.

3.4. Adaptive Immune Response

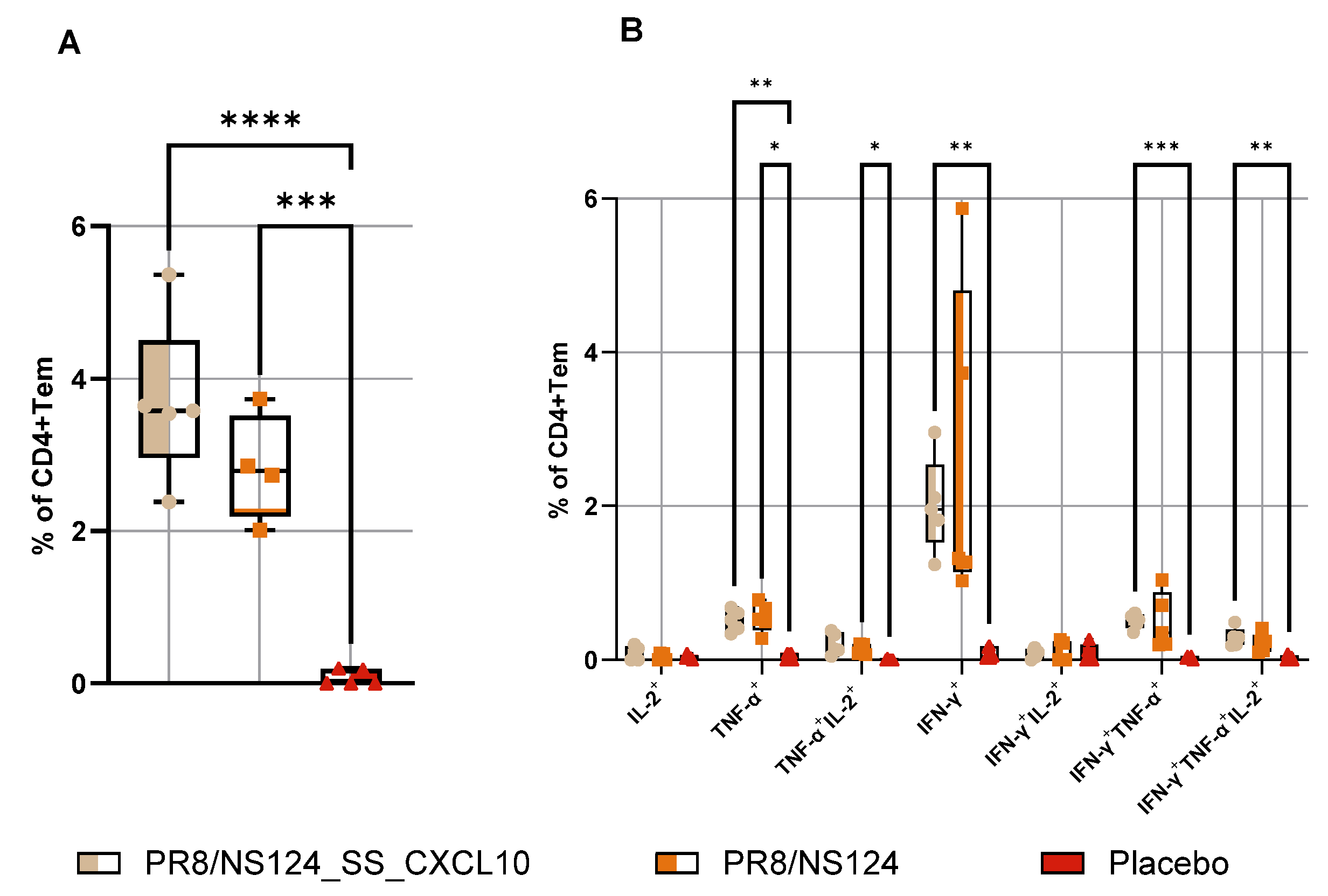

To define the impact of CXCL10 expression on the development of the adaptive immune response, we quantified antigen-specific CD8⁺ and CD4⁺ effector-memory T cells producing IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 in the spleen 10 days after intraperitoneal immunization (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). Despite the markedly attenuated replication of the PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 vector in the peritoneal cavity, mice immunized with this construct developed significantly stronger CD8⁺ Tcells responses. The frequencies of IFN-γ⁺, IFN-γ⁺TNF-α⁺, and multifunctional IFN-γ⁺TNF-α⁺IL-2⁺ CD8⁺ T cells were markedly elevated compared to the NS124 empty vector, and the overall pool of cytokine-producing CD8⁺ T cells was also significantly increased in the CXCL10 vector group compared to placebo group (p < 0.0001).

A similar enhancement was observed in the CD4⁺ T cells compartment. PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 induced the highest frequencies of IFN-γ⁺, IFN-γ⁺TNF-α⁺ and multifunctional IFN-γ⁺TNF-α⁺IL-2⁺ CD4⁺ T cells, with levels significantly elevated relative to the placebo group (p < 0.01). In contrast, PR8/NS124 alone generated only modest IFN-γ-based CD4⁺ responses, and overall cytokine production remained substantially lower than in the CXCL10 group. TNF-α⁺IL-2⁺ and multifunctional CD4⁺ subsets remained relatively low across groups.

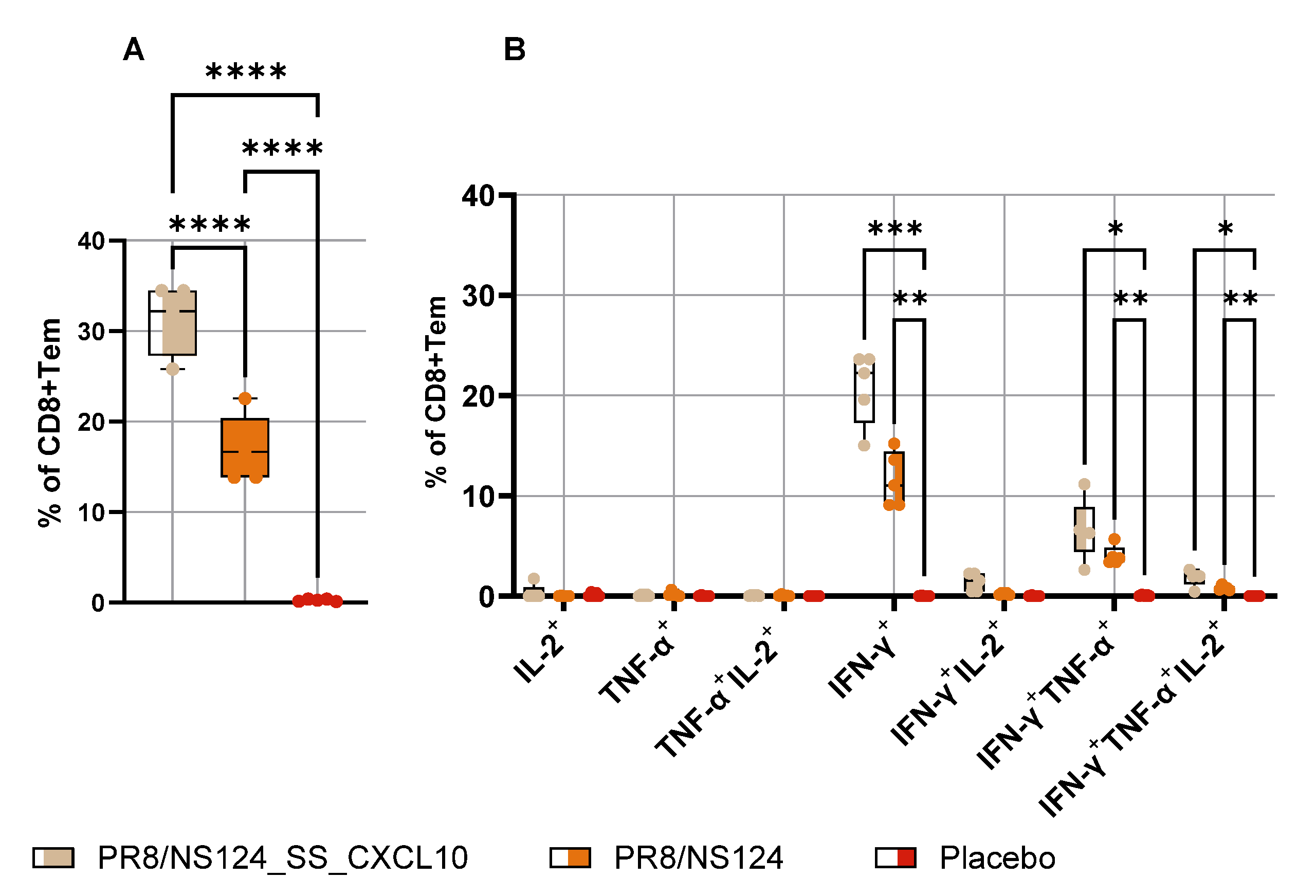

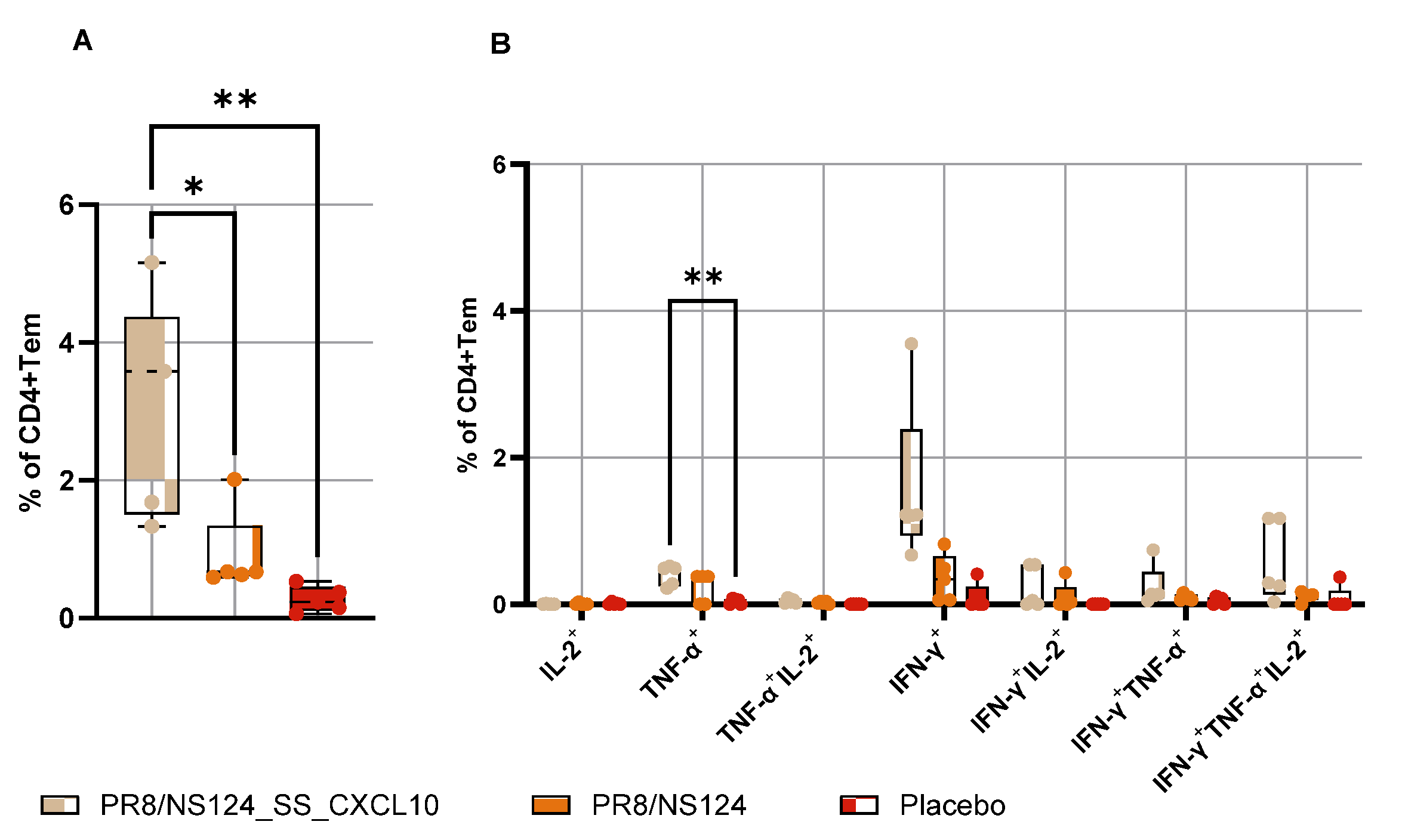

To determine whether systemic immunization could also elicit mucosal memory, mice were infected intranasally with a very low dose (3 lg EID50 per mouse) of A/PR8 wt virus on day 21, and lungs were collected on day 25 (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). Following this low-dose challenge, PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 elicited the strongest lung CD8⁺ T response, with significantly elevated frequencies of IFN-γ⁺, TNF-α⁺, and multifunctional IFN-γ⁺TNF-α⁺IL-2⁺ CD8⁺ cells compared to placebo group (p < 0.05). Lung CD4⁺ T cell responses showed a similar pattern, with significantly higher TNF-α⁺ CD4⁺ T-cell frequencies in the CXCL10 group (p < 0.01), whereas IL-2⁺ and IFN-γ⁺ subsets remained low and did not differ significantly. Despite its substantial attenuation in vivo, the CXCL10-expressing vector was nonetheless able to drive a significantly enhanced and functionally superior adaptive T-cell response.

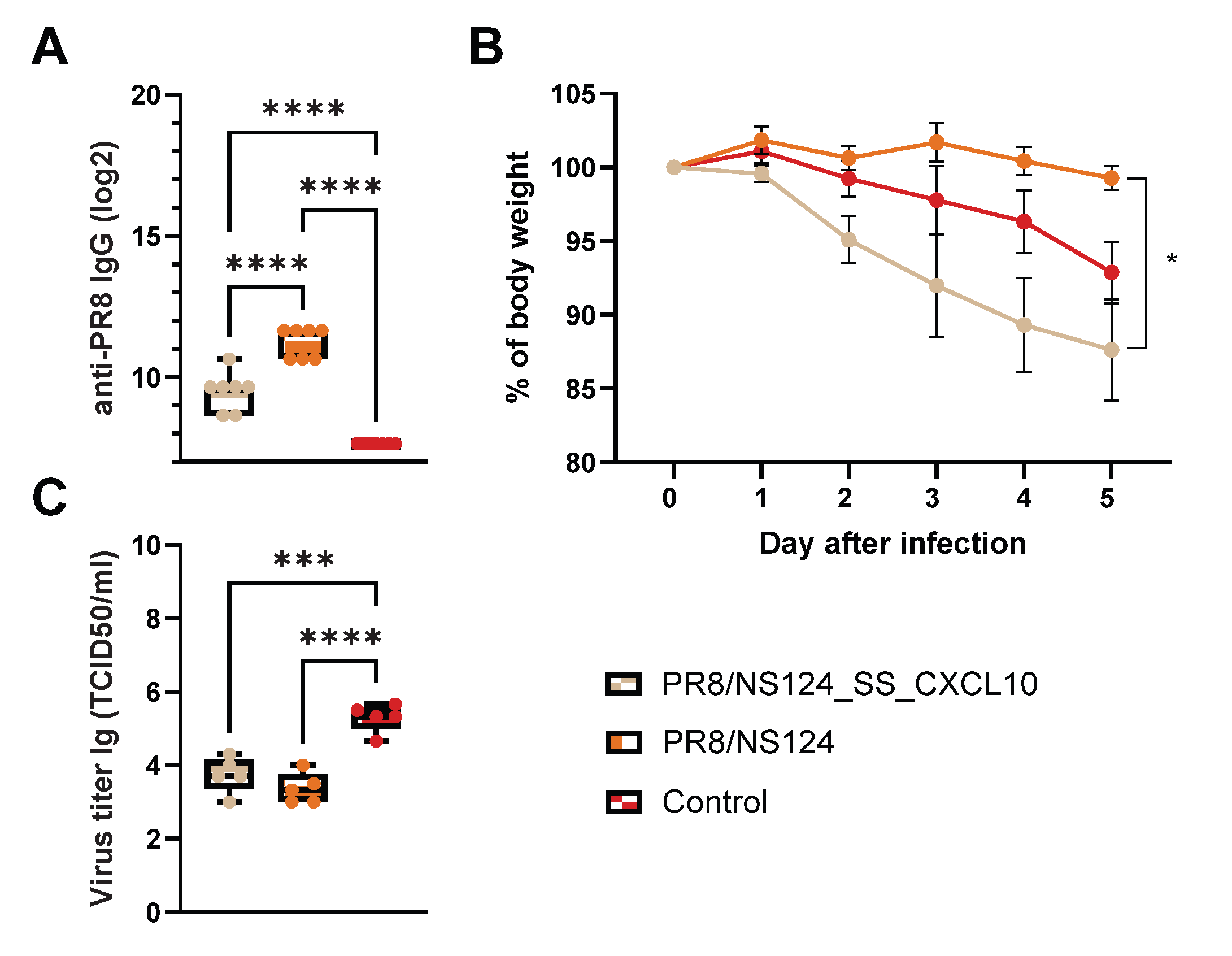

3.4. Intranasal Immunization with CXCL10 Expressing Vector Provoked Lung Damage in Mice

To assess CD8⁺ T cells functional relevance in a viral challenge model C57BL/6mice were immunized intranasally of dose of 6 lg EID50 per mouse; control animals received PBS (30 μl). 21 days after immunization, the mice were infected with the strain A/Aichi/2/68 (H3N2) at a dose of 10MLD50 (

Figure 12).

Both PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 and PR8/NS124 vaccinated mice developed high titers of anty-PR8 IgG compared with control animals, in which antibodies were almost undetectable (p < 0.0001 vs. control). IgG levels were significantly higher in the PR8/NS124 group than in the PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 group (p < 0.0001). These result indicate that, CXCL10 appears to bias the immune response toward a CXCR3⁺ Th1/effector phenotype rath helper (Tfh) cells.

Body weight was monitored for five days following infection to assess disease severity across treatment groups. Mice infected with PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 exhibited the most pronounced weight loss, beginning on day 1 and continuing through day 5, reaching approximately 87% of their starting body weight. In contrast, mice infected with PR8/NS124 maintained body weight more effectively throughout the observation period, with only minimal loss and ending near 98% of baseline weight by day 5. Control mice displayed an intermediate phenotype, with gradual weight reduction to approximately 92% by day 5. A statistically significant difference in body weight among the groups was observed at day 5, indicating that expression of the SS_CXCL10 construct in the PR8/NS124 backbone exacerbated disease severity relative to PR8/NS124 alone.

Both PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 and PR8/NS124 vaccination significantly reduced viral loads compared to control mice (p ≤ 0.001). Notably, the CXCL10 group exhibited more weight loss despite having lower viral titers. This pattern suggests that the observed pathology is likely driven by T cell-mediated or cytokine-driven immunopathology rather than direct virus-induced damage.

Figure 13.

CD8⁺ T cells functional relevance in a viral challenge model. C57BL/6 mice were immunized intranasally with 30 μl of 6 lg ELD50 per mouse; control animals received PBS. 21 days after immunization, the mice were infected with the strain A/Aichi/2/68 (H3N2) at a dose of 10MLD50. Total serum IgG (A), body weight (B) and viral load in lungs (C). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 13.

CD8⁺ T cells functional relevance in a viral challenge model. C57BL/6 mice were immunized intranasally with 30 μl of 6 lg ELD50 per mouse; control animals received PBS. 21 days after immunization, the mice were infected with the strain A/Aichi/2/68 (H3N2) at a dose of 10MLD50. Total serum IgG (A), body weight (B) and viral load in lungs (C). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001).

4. Discussion

In this article, we describe the attenuation profile and immunogenic properties of an influenza A virus vector engineered to express human CXCL10. The PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 construct demonstrated a markedly replication-restricted phenotype in vivo, yet it elicited enhanced systemic and mucosal T-cell responses compared with the empty NS124 vector. This dual behavior - strong attenuation combined with robust T-cell immunogenicity-highlights the potential of CXCL10-expressing influenza vectors as versatile immunomodulatory platforms.

The markedly enhanced T-cell immunity induced by the CXCL10-expressing vector suggests potential applications beyond classical antiviral vaccination. CXCL10 is a well-established chemoattractant for activated CD8⁺ T cells and NK cells, functioning through the CXCR3 axis to guide effector lymphocytes into inflamed tissues [

25]. Several viral platforms, including adenovirus, HSV-1, vaccinia, and VSV, have successfully incorporated CXCL10 to enhance intratumoral T-cell infiltration and antitumor efficacy [

19,

26,

27]. In this context, the PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 vector may represent a novel candidate for oncolytic or immunotherapeutic development. Influenza viruses naturally infect epithelial tissues, can be engineered for controlled replication, and possess potent innate stimulatory properties, making them attractive tools for reshaping tumor microenvironments toward antitumor immunity.

Of particular interest is the immune-excluded nature of high-grade gliomas, where impaired CXCR3-CXCL10 signaling contributes to insufficient recruitment of effector T cells [

28,

29]. A CXCL10-expressing influenza backbone could help overcome this barrier by generating strong chemotactic gradients and promoting early infiltration of cytotoxic lymphocytes. Importantly, the safety profile of such a strategy may be favorable. In this study, the PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 vector demonstrated a strongly attenuated phenotype in two anatomical compartments. Following intranasal inoculation, viral replication in the lungs remained near the detection threshold, and even after intraperitoneal administration, where both vectors access susceptible cells, CXCL10 expression markedly restricted replication relative to the empty vector. This replication limiting effect appears to be a general in vivo property of the vector, an advantageous feature for intratumoral or intracranial delivery, although dedicated neurovirulence and biodistribution studies are required.

Beyond oncological applications, CXCL10-expressing influenza vectors may also enhance mucosal vaccination strategies. The PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 virus exhibited substantial attenuation after intranasal inoculation yet elicited strong systemic and mucosal T-cell responses, a combination desirable for next-generation intranasal vaccines aimed at inducing cross-protective T-cell immunity. Heterosubtypic immunity against influenza, particularly against drifted or antigenically distinct strains, is mediated largely by CD8⁺ T cells recognizing conserved internal antigens such as NP and M1 [

30,

31]. CXCL10-mediated recruitment of effector T cells to the respiratory mucosa may therefore broaden the magnitude and durability of such responses. Incorporating CXCL10 into NS1-modified live attenuated influenza vaccine strains may provide a means of enhancing cellular immunogenicity while preserving acceptable attenuation profiles.

However, our findings also demonstrate that CXCL10 expression alters the balance between immune recall and viral control in ways that can be detrimental during heterologous challenge. In the H3N2 challenge experiment, mice were immunized intranasally - without secondary antigenic stimulation and the PR8/NS124 vector provided effective protection despite the absence of strain-matched neutralizing antibodies. This outcome aligns with established principles of heterosubtypic immunity: protection is mediated by early mucosal imprinting, local innate activation, and tissue-resident memory T cells (Trm) recognizing conserved viral epitopes [

30,

31]. Because PR8/NS124 replicated efficiently in the lungs during primary immunization, it likely established stronger local antigen presentation, antiviral conditioning, and early Trm seeding, all contributing to rapid control of the heterologous challenge.

In contrast, the CXCL10 vector replicated only minimally in the lungs during primary immunization, limiting early mucosal priming and leaving the respiratory tract permissive to rapid H3N2 replication. Although CXCL10-primed memory T cells recognized conserved internal epitopes and mounted strong effector responses upon infection, this vigorous T-cell recall occurred in the context of high viral burden. Strong T-cell responses, particularly those dominated by TNF-α production, are known to contribute to immunopathology when elicited in tissues with substantial viral replication [

32]. This imbalance - robust T-cell recall in the setting of insufficient early viral control - offers a plausible mechanism for the VAERD-like pathology observed in CXCL10-immunized mice and is consistent with T-cell-mediated immunopathology rather than antibody-dependent enhancement.

It is important to clarify that the lung T-cell responses in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 were obtained under experimental conditions designed specifically to measure antigen-driven recall, not the baseline mucosal memory established by the priming immunization. Mice were initially immunized intraperitoneally, a route that does not efficiently seed Tem in the lungs, and were subsequently given a low-dose PR8 infection 3 days prior to lung harvest, a time frame optimal for capturing recall-driven recruitment and expansion of circulating memory T cells. Thus, the elevated lung Tem frequencies observed in CXCL10-vaccinated mice after PR8 restimulation represent enhanced recall responsiveness rather than superior primary Tem formation.

The TNF-α dominance within the CD4⁺ Tem compartment of CXCL10-vaccinated mice further supports this interpretation. This cytokine profile reflects an effector-oriented Th1-like memory state capable of rapid inflammatory licensing, dendritic cell maturation, and upregulation of endothelial adhesion molecules [

33]. While such TNF-weighted helper responses may be advantageous for antitumor immunity or control of homologous viral infection, they may exacerbate tissue damage when activated in a setting of high heterologous viral replication, as observed here.

Taken together, these findings highlight the broad immunological potential of CXCL10-expressing influenza vectors and outline multiple avenues for future development. Their unique balance of strong attenuation and T-cell-enhancing properties positions them as promising candidates for oncolytic virotherapy, especially for immune-excluded tumors such as glioma, and for improving the performance of intranasal influenza vaccines. At the same time, the VAERD-like outcome observed during heterologous challenge underscores the need to carefully consider the interplay between mucosal priming, T-cell recall kinetics, and viral replication when designing chemokine-expressing influenza vaccines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AE. and OO.; methodology, OO., MSh., APS. AP.; software, MSh. AP.; validation, OO., MSh. and AM.; formal analysis, AM.; investigation, OO., AM.; resources, MSt.; data curation, MSt.; writing—original draft preparation, OO.; writing—review and editing, AE. APS.; visualization, OO.; supervision, MSt.; project administration, MSt.; funding acquisition, MSt. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation government contract, grant 124021200035-2 «Preclinical studies and development of a finished dosage form of an oncolytic vector drug based on a modified influenza A virus for the complex therapy of malignant gliomas»

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Independent Bioethics Committee at the Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza (Approval #19 dated 03 September 2025).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IAV |

Influenza A virus |

| ANOVA |

analysis of variance |

| DC |

Dendritic cells |

| CXCR3 |

C-X-C motif receptor 3 |

| CXCL10 |

High serum C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 |

| NK |

Natural killer |

| NS |

Nonstructural protein |

| CE |

Chicken embryos |

| EID50 |

50% embryonic infectious dose |

| TCID50 |

50% culture infectious dose |

| TMB |

3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine |

| MDCK |

Madin-Darby canine kidney cell |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| MLD50 |

50% mice lethal Dose |

| PCR |

polymerase chain reaction |

| HSV-1, |

Human herpesvirus 1 |

| VAERD |

Vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease |

| VSV |

Vesicular stomatitis virus |

| SEM |

standard error of the mean |

| SD |

standard deviation |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

References

- Bian, C.; Liu, S.; Liu, N.; Zhang, G.; Xing, L.; Song, Y.; Duan, Y.; Gu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, P.; et al. Influenza Virus Vaccine Expressing Fusion and Attachment Protein Epitopes of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Induces Protective Antibodies in BALB/c Mice. Antiviral Res 2014, 104, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugybayeva, D.; Kydyrbayev, Z.; Zinina, N.; Assanzhanova, N.; Yespembetov, B.; Kozhamkulov, Y.; Zakarya, K.; Ryskeldinova, S.; Tabynov, K. A New Candidate Vaccine for Human Brucellosis Based on Influenza Viral Vectors: A Preliminary Investigation for the Development of an Immunization Schedule in a Guinea Pig Model. Infect Dis Poverty 2021, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittel, C.; Ferko, B.; Kurz, M.; Voglauer, R.; Sereinig, S.; Romanova, J.; Stiegler, G.; Katinger, H.; Egorov, A. Generation of an Influenza A Virus Vector Expressing Biologically Active Human Interleukin-2 from the NS Gene Segment. J Virol 2005, 79, 10672–10677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, A.; Brandt, S.; Sereinig, S.; Romanova, J.; Ferko, B.; Katinger, D.; Grassauer, A.; Alexandrova, G.; Katinger, H.; Muster, T. Transfectant Influenza A Viruses with Long Deletions in the NS1 Protein Grow Efficiently in Vero Cells. J Virol 1998, 72, 6437–6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurygina, A.P.; Shuklina, M.; Ozhereleva, O.; Romanovskaya-Romanko, E.; Kovaleva, S.; Egorov, A.; Lioznov, D.; Stukova, M. Truncated NS1 Influenza A Virus Induces a Robust Antigen-Specific Tissue-Resident T-Cell Response and Promotes Inducible Bronchus-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Formation in Mice. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stukova, M.A.; Sereinig, S.; Zabolotnyh, N. V; Ferko, B.; Kittel, C.; Romanova, J.; Vinogradova, T.I.; Katinger, H.; Kiselev, O.I.; Egorov, A. Vaccine Potential of Influenza Vectors Expressing Mycobacterium Tuberculosis ESAT-6 Protein. Tuberculosis 2006, 86, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luytjes, W.; Krystai, M.; Enami, M.; Parvin, J.D.; Ralese, P. Amplification, Expression, and Packaging of a Foreign Gene by Influenza Virus. Cell 1989, 59, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferko, B.; Stasakova, J.; Romanova, J.; Kittel, C.; Sereinig, S.; Katinger, H.; Egorov, A. Immunogenicity and Protection Efficacy of Replication-Deficient Influenza A Viruses with Altered NS1 Genes. J Virol 2004, 78, 13037–13045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferko, B.; Kittel, C.; Romanova, J.; Sereinig, S.; Katinger, H.; Egorov, A. Live Attenuated Influenza Virus Expressing Human Interleukin-2 Reveals Increased Immunogenic Potential in Young and Aged Hosts. J Virol 2006, 80, 11621–11627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sastre, A.; Egorov, A.; Matassov, D.; Brandt, S.; Levy, D.E.; Durbin, J.E.; Palese, P.; Muster, T. Influenza A Virus Lacking the NS1 Gene Replicates in Interferon-Deficient Systems. Virology 1998, 252, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilyev, K.A.; Yukhneva, M.A.; Shurygina, A.-P.S.; Stukova, M.A.; Egorov, A.Y. Enhancement of the Immunogenicity of Influenza A Virus by the Inhibition of Immunosuppressive Function of NS1 Protein. Microbiology Independent Research Journal (MIR Journal) 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muster, T.; Rajtarova, J.; Sachet, M.; Unger, H.; Fleischhacker, R.; Romirer, I.; Grassauer, A.; Url, A.; García-Sastre, A.; Wolff, K.; et al. Interferon Resistance Promotes Oncolysis by Influenza Virus NS1-Deletion Mutants. Int J Cancer 2004, 110, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Rikxoort, M.; Michaelis, M.; Wolschek, M.; Muster, T.; Egorov, A.; Seipelt, J.; Doerr, H.W.; Cinatl, J. Oncolytic Effects of a Novel Influenza A Virus Expressing Interleukin-15 from the NS Reading Frame. PLoS One 2012, 7, e36506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loetscher, P.; Pellegrino, A.; Gong, J.H.; Mattioli, I.; Loetscher, M.; Bardi, G.; Baggiolini, M.; Clark-Lewis, I. The Ligands of CXC Chemokine Receptor 3, I-TAC, Mig, and IP10, Are Natural Antagonists for CCR3. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 2986–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, J.R.; Luster, A.D. CXCR3 Ligands: Redundant, Collaborative and Antagonistic Functions. Immunol Cell Biol 2011, 89, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Doshi, M.; Hack, B.K.; Alexander, J.J.; Quigg, R.J. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Rat Factor H-Related Protein That Is up-Regulated in Glomeruli under Complement Attack. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 48351–48358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikucki, M.E.; Fisher, D.T.; Matsuzaki, J.; Skitzki, J.J.; Gaulin, N.B.; Muhitch, J.B.; Ku, A.W.; Frelinger, J.G.; Odunsi, K.; Gajewski, T.F.; et al. Non-Redundant Requirement for CXCR3 Signalling during Tumoricidal T-Cell Trafficking across Tumour Vascular Checkpoints. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 7458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifilo, M.J.; Lane, T.E. Adenovirus-Mediated Expression of CXCL10 in the Central Nervous System Results in T-Cell Recruitment and Limited Neuropathology. J Neurovirol 2003, 9, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, M.; Yuan, M.; Ye, J.; Zhang, W.; Xu, L.; Wu, X.; Hui, B.; Yang, Y.; Wei, B.; et al. CXCL10-Armed Oncolytic Adenovirus Promotes Tumor-Infiltrating T-Cell Chemotaxis to Enhance Anti-PD-1 Therapy. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feodoroff, M.; Hamdan, F.; Antignani, G.; Feola, S.; Fusciello, M.; Russo, S.; Chiaro, J.; Välimäki, K.; Pellinen, T.; Branca, R.M.; et al. Enhancing T-Cell Recruitment in Renal Cell Carcinoma with Cytokine-Armed Adenoviruses. Oncoimmunology 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Roemeling, C.A.; Patel, J.A.; Carpenter, S.L.; Yegorov, O.; Yang, C.; Bhatia, A.; Doonan, B.P.; Russell, R.; Trivedi, V.S.; Klippel, K.; et al. Adeno-Associated Virus Delivered CXCL9 Sensitizes Glioblastoma to Anti-PD-1 Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, E.; Neumann, G.; Hobom, G.; Webster, R.G.; Kawaoka, Y. “Ambisense” Approach for the Generation of Influenza A Virus: VRNA and MRNA Synthesis from One Template. Virology 2000, 267, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A Simple Method of Estimating Fifty per Cent Endpoints. Am J Epidemiol 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilyev, K.; Shurygina, A.-P.; Sergeeva, M.; Stukova, M.; Egorov, A. Intranasal Immunization with the Influenza A Virus Encoding Truncated NS1 Protein Protects Mice from Heterologous Challenge by Restraining the Inflammatory Response in the Lungs. Microorganisms 2021, Vol. 9, 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, R.; Zhang, W.; Naseem, M.; Puccini, A.; Berger, M.D.; Soni, S.; McSkane, M.; Baba, H.; Lenz, H.J. CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11/CXCR3 Axis for Immune Activation – A Target for Novel Cancer Therapy. Cancer Treat Rev 2018, 63, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.; Khan, A.A.; Chilukuri, S.; Syed, S.A.; Tran, T.T.; Furness, J.; Bahraoui, E.; BenMohamed, L. CXCL10/CXCR3-Dependent Mobilization of Herpes Simplex Virus-Specific CD8 + T EM and CD8 + T RM Cells within Infected Tissues Allows Efficient Protection against Recurrent Herpesvirus Infection and Disease. J Virol 2017, 91, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steain, M.; Gowrishankar, K.; Rodriguez, M.; Slobedman, B.; Abendroth, A. Upregulation of CXCL10 in Human Dorsal Root Ganglia during Experimental and Natural Varicella-Zoster Virus Infection. J Virol 2011, 85, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Zhang, J.; Tong, H.; Xie, T.; Chen, X.; Zhou, B.; Wu, P.; Zhong, P.; Du, X.; Guo, Y.; et al. Effects of BMPER, CXCL10, and HOXA9 on Neovascularization During Early-Growth Stage of Primary High-Grade Glioma and Their Corresponding MRI Biomarkers. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 497108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maru, S. V.; Holloway, K.A.; Flynn, G.; Lancashire, C.L.; Loughlin, A.J.; Male, D.K.; Romero, I.A. Chemokine Production and Chemokine Receptor Expression by Human Glioma Cells: Role of CXCL10 in Tumour Cell Proliferation. J Neuroimmunol 2008, 199, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenburg, A.F.; Rimmelzwaan, G.F.; de Vries, R.D. Virus-Specific T Cells as Correlate of (Cross-)Protective Immunity against Influenza. Vaccine 2015, 33, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebe, K.M.; Yewdell, J.W.; Bennink, J.R. Heterosubtypic Immunity to Influenza A Virus: Where Do We Stand? Microbes Infect 2008, 10, 1024–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.A.; Rittchen, S.; Li, J.; Hasnain, S.Z.; Phipps, S. DP1 Prostanoid Receptor Activation Increases the Severity of an Acute Lower Respiratory Viral Infection in Mice via TNF-α-Induced Immunopathology. Mucosal Immunol 2021, 14, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Su, Y.; Jiao, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B. T Cells in Health and Disease. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 2023 8:1 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

CXCL10 expression rate. To measure the CXCL10 concentration 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs were infected with PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 and allantoic fluid was harvested at 2 days postinfection. CXCL10 concentrations in the allantoic fluid were analyzed using a LEGEND MAX™ Human CXCL10 (IP-10) ELISA Kit.

Figure 1.

CXCL10 expression rate. To measure the CXCL10 concentration 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs were infected with PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 and allantoic fluid was harvested at 2 days postinfection. CXCL10 concentrations in the allantoic fluid were analyzed using a LEGEND MAX™ Human CXCL10 (IP-10) ELISA Kit.

Figure 2.

Reproductive activity of PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 virus in chicken embryos (A), MDCK cells (B) and mice (C). To determine the viral load, BALB/c mice were immunized intranasally at a dose of 6 lg per mouse in a volume of 30 μL. Viral shedding was evaluated on day 3 post-immunisation. Viral titers were determined by titrating tissue homogenates in MDCK cells. Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by unpaired t test (****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Reproductive activity of PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 virus in chicken embryos (A), MDCK cells (B) and mice (C). To determine the viral load, BALB/c mice were immunized intranasally at a dose of 6 lg per mouse in a volume of 30 μL. Viral shedding was evaluated on day 3 post-immunisation. Viral titers were determined by titrating tissue homogenates in MDCK cells. Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by unpaired t test (****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Sampling plan for the assessment of the PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 virus immunogenicity.

Figure 3.

Sampling plan for the assessment of the PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 virus immunogenicity.

Figure 4.

Early cytokine profile in the peritoneal cavity. To measure cytokine concentrations C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with the NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the NS124 (empty vector) strains at a dose of 7 lg EID50 per mouse. The control group received PBS in the corresponding volume (500 μl per mouse). Peritoneal washes were collected 12 and 24 hours after immunization. Cytokine concentration was measured using the LEGENDplex multiplex system (Biolegend, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of IFN-γ, (A), IL-6 (B), TNF-α (C), IL-10 (D) and IL-9 (E) are shown as box and whiskers plots (min and max with individual values and the median indicated). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 4.

Early cytokine profile in the peritoneal cavity. To measure cytokine concentrations C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with the NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the NS124 (empty vector) strains at a dose of 7 lg EID50 per mouse. The control group received PBS in the corresponding volume (500 μl per mouse). Peritoneal washes were collected 12 and 24 hours after immunization. Cytokine concentration was measured using the LEGENDplex multiplex system (Biolegend, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of IFN-γ, (A), IL-6 (B), TNF-α (C), IL-10 (D) and IL-9 (E) are shown as box and whiskers plots (min and max with individual values and the median indicated). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 5.

Early innate immune cell recruitment. To measure innate immune cell recruitment C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with the NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the NS124 (empty vector) strains at a dose of 7 lg EID50 per mouse. The control group received PBS in the corresponding volume (500 μl per mouse). Peritoneal washes were collected 12 and 24 hours after immunization. Innate immune response in the peritoneal cavity was assessed at 12- and 24-hours p.im. The percentage of neutrophils in the parent population (CD45+ live cells) (A), the percentage of monocytes in the grandparent population (CD45+ live cells) (B), the percentage of macrophages in the grandparent population (CD45+ live cells) (C), and the percentage of dendritic cells in the grandparent population (CD45+ live cells) (D) are shown as box and whiskers plots (min and max with individual values and the median indicated).

Figure 5.

Early innate immune cell recruitment. To measure innate immune cell recruitment C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with the NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the NS124 (empty vector) strains at a dose of 7 lg EID50 per mouse. The control group received PBS in the corresponding volume (500 μl per mouse). Peritoneal washes were collected 12 and 24 hours after immunization. Innate immune response in the peritoneal cavity was assessed at 12- and 24-hours p.im. The percentage of neutrophils in the parent population (CD45+ live cells) (A), the percentage of monocytes in the grandparent population (CD45+ live cells) (B), the percentage of macrophages in the grandparent population (CD45+ live cells) (C), and the percentage of dendritic cells in the grandparent population (CD45+ live cells) (D) are shown as box and whiskers plots (min and max with individual values and the median indicated).

Figure 6.

Viral loads in peritoneal cavity. To measure viral loads in peritoneal cavity C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with the NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the NS124 (empty vector) strains at a dose of 7 lg EID50 per mouse. The control group received PBS in the corresponding volume (500 μl per mouse). Peritoneal washes were collected 12 and 24 hours after immunization. Ct values above 38 were considered below the threshold for biologically meaningful replication and interpreted as minimal or non-productive viral activity. Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by unpaired t test (****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 6.

Viral loads in peritoneal cavity. To measure viral loads in peritoneal cavity C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with the NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the NS124 (empty vector) strains at a dose of 7 lg EID50 per mouse. The control group received PBS in the corresponding volume (500 μl per mouse). Peritoneal washes were collected 12 and 24 hours after immunization. Ct values above 38 were considered below the threshold for biologically meaningful replication and interpreted as minimal or non-productive viral activity. Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by unpaired t test (****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 7.

Early naïve CD4⁺ (A) and CD8⁺ (B) T-cell recruitment. C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the empty PR8/NS124 vector at 7 lg EID50 per mouse. Control animals received PBS (500 μl). Peritoneal washes were collected 12 and 24 hours after immunization. The percentages of CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells among live cells are shown as box-and-whisker plots (min to max with individual values and the median).

Figure 7.

Early naïve CD4⁺ (A) and CD8⁺ (B) T-cell recruitment. C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with PR8/NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the empty PR8/NS124 vector at 7 lg EID50 per mouse. Control animals received PBS (500 μl). Peritoneal washes were collected 12 and 24 hours after immunization. The percentages of CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells among live cells are shown as box-and-whisker plots (min to max with individual values and the median).

Figure 8.

Antigen-specific CD8+Tem response in the spleen. To measure Tem response in the spleen C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with the NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the NS124 (empty vector) strains at a dose of 7 lg EID50 per mouse. The control group received PBS in the corresponding volume (500 μl per mouse). Spleens were collected at 10 d.p.im. Tem response in the spleen was assessed by intracellular cytokine staining after 6 h of in vitro stimulation with the NP366–374 peptide. The total percentage of cytokine-producing CD8+ Trm lymphocytes (A) and the percentage of CD8+ Tem producing any combination of IFN-γ, IL-2, or TNF-α (B) are shown as box and whiskers plots (min and max with individual values and the median indicated). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 8.

Antigen-specific CD8+Tem response in the spleen. To measure Tem response in the spleen C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with the NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the NS124 (empty vector) strains at a dose of 7 lg EID50 per mouse. The control group received PBS in the corresponding volume (500 μl per mouse). Spleens were collected at 10 d.p.im. Tem response in the spleen was assessed by intracellular cytokine staining after 6 h of in vitro stimulation with the NP366–374 peptide. The total percentage of cytokine-producing CD8+ Trm lymphocytes (A) and the percentage of CD8+ Tem producing any combination of IFN-γ, IL-2, or TNF-α (B) are shown as box and whiskers plots (min and max with individual values and the median indicated). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 9.

Antigen-specific CD4+Tem response in the spleen. To measure Tem response in the spleen C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with the NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the NS124 (empty vector) strains at a dose of 7 lg EID50 per mouse. The control group received PBS in the corresponding volume (500 μl per mouse). Spleens were collected at 10 d.p.im. Tem response in the spleen was assessed by intracellular cytokine staining after 24 h of in vitro stimulation with the A/PR8 wt virus. The total percentage of cytokine-producing CD4+ Tem lymphocytes (A) and the percentage of CD8+ Tem producing any combination of IFN-γ, IL-2, or TNF-α (B) are shown as box and whiskers plots (min and max with individual values and the median indicated). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 9.

Antigen-specific CD4+Tem response in the spleen. To measure Tem response in the spleen C57BL/6 mice were immunized intraperitoneally with the NS124_SS_CXCL10 or the NS124 (empty vector) strains at a dose of 7 lg EID50 per mouse. The control group received PBS in the corresponding volume (500 μl per mouse). Spleens were collected at 10 d.p.im. Tem response in the spleen was assessed by intracellular cytokine staining after 24 h of in vitro stimulation with the A/PR8 wt virus. The total percentage of cytokine-producing CD4+ Tem lymphocytes (A) and the percentage of CD8+ Tem producing any combination of IFN-γ, IL-2, or TNF-α (B) are shown as box and whiskers plots (min and max with individual values and the median indicated). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 10.

Antigen-specific CD8+Tem response in the lung. To measure the development of a mucosal T-cell response after peritoneal immunization animals were challenged with A/PR8 wt virus (3 lg EID50 per mouse) on 21 days, lungs were isolated on day 25. Tem response in the lung was assessed by intracellular cytokine staining after 6 h of in vitro stimulation with the NP366–374 peptides. The total percentage of cytokine-producing CD8+ Tem lymphocytes (A) and the percentage of CD8+ Tem producing any combination of IFN-γ, IL-2, or TNF-α (B) are shown as box and whiskers plots (min and max with individual values and the median indicated). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 10.

Antigen-specific CD8+Tem response in the lung. To measure the development of a mucosal T-cell response after peritoneal immunization animals were challenged with A/PR8 wt virus (3 lg EID50 per mouse) on 21 days, lungs were isolated on day 25. Tem response in the lung was assessed by intracellular cytokine staining after 6 h of in vitro stimulation with the NP366–374 peptides. The total percentage of cytokine-producing CD8+ Tem lymphocytes (A) and the percentage of CD8+ Tem producing any combination of IFN-γ, IL-2, or TNF-α (B) are shown as box and whiskers plots (min and max with individual values and the median indicated). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 11.

Antigen-specific CD4+Tem response in the lung. To measure the development of a mucosal T-cell response after peritoneal immunization animals were challenged with A/PR8 wt virus (3 lg EID50 per mouse) on 21 days, lungs were isolated on day 25. Tem response in the lung was assessed by intracellular cytokine staining after 24 h of in vitro stimulation with A/PR8 wt virus. The total percentage of cytokine-producing CD4+ Tem lymphocytes (A) and the percentage of CD4+ Tem producing any combination of IFN-γ, IL-2, or TNF-α (B) the total percentage of cytokine-producing CD4+ Tem lymphocytes (B) are shown as box and whiskers plots (min and max with individual values and the median indicated). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 11.

Antigen-specific CD4+Tem response in the lung. To measure the development of a mucosal T-cell response after peritoneal immunization animals were challenged with A/PR8 wt virus (3 lg EID50 per mouse) on 21 days, lungs were isolated on day 25. Tem response in the lung was assessed by intracellular cytokine staining after 24 h of in vitro stimulation with A/PR8 wt virus. The total percentage of cytokine-producing CD4+ Tem lymphocytes (A) and the percentage of CD4+ Tem producing any combination of IFN-γ, IL-2, or TNF-α (B) the total percentage of cytokine-producing CD4+ Tem lymphocytes (B) are shown as box and whiskers plots (min and max with individual values and the median indicated). Data were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05, as determined by one-or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001, ****: p < 0.0001).

Figure 12.

Sampling plan for challenge experiment.

Figure 12.

Sampling plan for challenge experiment.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).