1. Introduction

Traditional Ugandan cheeses represent an important component of the country’s culinary heritage and nutritional landscape; however, their production largely occurs under artisanal or semi-industrial conditions with minimal standardization. These cheeses are commonly produced from raw or only lightly processed milk and lack defined starter cultures, resulting in diverse and unregulated microbial communities [

1,

2]. Characterizing these microbial populations is essential for improving food safety, ensuring product consistency, and supporting the development of starter cultures suitable for traditional cheese production.

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are key contributors to dairy fermentations. Their ability to ferment carbohydrates into lactic acid drives acidification, which aids in coagulation, texture development, and inhibition of spoilage microorganisms. In addition to acidification, LAB synthesize a range of antimicrobial metabolites including bacteriocins, hydrogen peroxide, and diacetyl. These metabolites play important roles in microbial antagonism and contribute to the safety and stability of fermented foods [

3,

4,

5]. Yeasts also participate actively in ripening processes. Species such as

Yarrowia lipolytica and

Debaryomyces hansenii promote proteolysis, lipolysis, and aroma formation, influencing the sensory attributes that characterize many traditional cheeses [

6,

7].

With the global rise in antimicrobial resistance (AMR), assessing the safety of microorganisms used in foods has become increasingly important. Although LAB are generally regarded as safe, several studies have reported the presence of intrinsic or acquired antibiotic resistance genes within food-associated LAB, raising concerns about their potential contribution to the horizontal transfer of resistance determinants in the human gut [

8,

9,

10]. These risks may be exacerbated in informal dairy systems where hygienic oversight is limited and microbial diversity is high. At the same time, certain LAB and yeasts possess antimicrobial properties—such as bacteriocin production, competitive exclusion, and killer toxin secretion—that make them promising candidates for natural biopreservation strategies [

3,

11,

12,

13].

The technological suitability of LAB and yeasts is also strongly influenced by their physiological responses to environmental factors such as pH and temperature. Growth kinetics provide insight into microbial resilience and functional performance during fermentation, ripening, and storage. Acid-tolerant LAB, for example, dominate early fermentation stages, whereas yeasts and staphylococci often become more prevalent later as surface pH increases [

14,

15,

16]. Evaluating these characteristics helps identify strains capable of contributing reliably to cheese production, particularly in artisanal settings with naturally variable conditions.

Therefore, this study aimed to characterize LAB and yeast isolates from selected ripened Ugandan cheeses varieties. We assessed their antimicrobial activity, antibiotic susceptibility, and pH-dependent growth kinetics. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the microbial ecology of Ugandan cheeses and support the identification of safe and functional strains suitable for potential use as starter or adjunct cultures in artisanal and semi-industrial cheese production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection and Identification of Microbial Isolates

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and yeast isolates were obtained from previously characterized microbial collections derived from selected three months old varieties of ripened cheese (Gouda, Parmesan, Cheddar, and Jack) that were purchased from a local cheese-processing facility in southwestern Uganda. Samples were collected in triplicates, in sterile containers and transported under aseptic conditions to the laboratory of microbiology at Medical University of Graz, Austria for analysis. The LAB isolates included

Pediococcus pentosaceus,

Pediococcus acidilactici,

Lactococcus lactis,

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, and

Levilactobacillus brevis. These isolates had been identified through morphological, biochemical, and MALDI-TOF MS approaches as described by Abarquero et al. [

17]. The yeast

Yarrowia lipolytica and the rind-associated bacterium

Staphylococcus equorum were included due to their technological relevance in cheese surface ripening [

18].

All isolates were revived from −80 °C glycerol stocks on appropriate selective media. LAB cultures were grown on de Man–Rogosa–Sharpe (MRS) agar, yeasts were cultured on Yeast Peptone Dextrose (YPD) agar, and staphylococci on Mannitol Salt Agar (MSA), (all media purchased from Merck, Austria). Pure colonies were subcultured twice before subsequent assays.

2.2. Antimicrobial Activity Assays

2.2.1. Agar Well Diffusion Method

Antimicrobial activity of isolates against

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29219,

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27837 was assessed using the agar well diffusion method following Balouiri et al. [

19] and Perez et al. [

20], with slight modifications.

LAB were incubated in MRS broth (Merck, Austria) at 37 °C for 48 h. Cultures were centrifuged (4000 ×g, 10 min), and the resulting cell-free supernatant (CFS) was filtered (0.22 µm). Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA, Merck Austria) plates were inoculated with standardized pathogen suspensions (0.5 McFarland). Wells (6 mm) were cut aseptically, filled with 100 µL of CFS, and plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Inhibition zone diameters were measured to the nearest millimeter.

2.2.2. Disc Spotting Confirmation Assay

To validate the well diffusion results, isolates were further tested using a disc-spot assay described by Yang et al. [

21]. Sterile filter discs were spotted with 10 µL of overnight cultures and placed on freshly inoculated MHA plates. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C, after which inhibition zones were recorded. Positive controls included nisin solution (10 µg/mL). Negative controls consisted of uninoculated broth processed identically to test samples.

2.3. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Antibiotic susceptibility was evaluated using the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method according to European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (

EUCAST) and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (

CLSI) recommendations [

22,

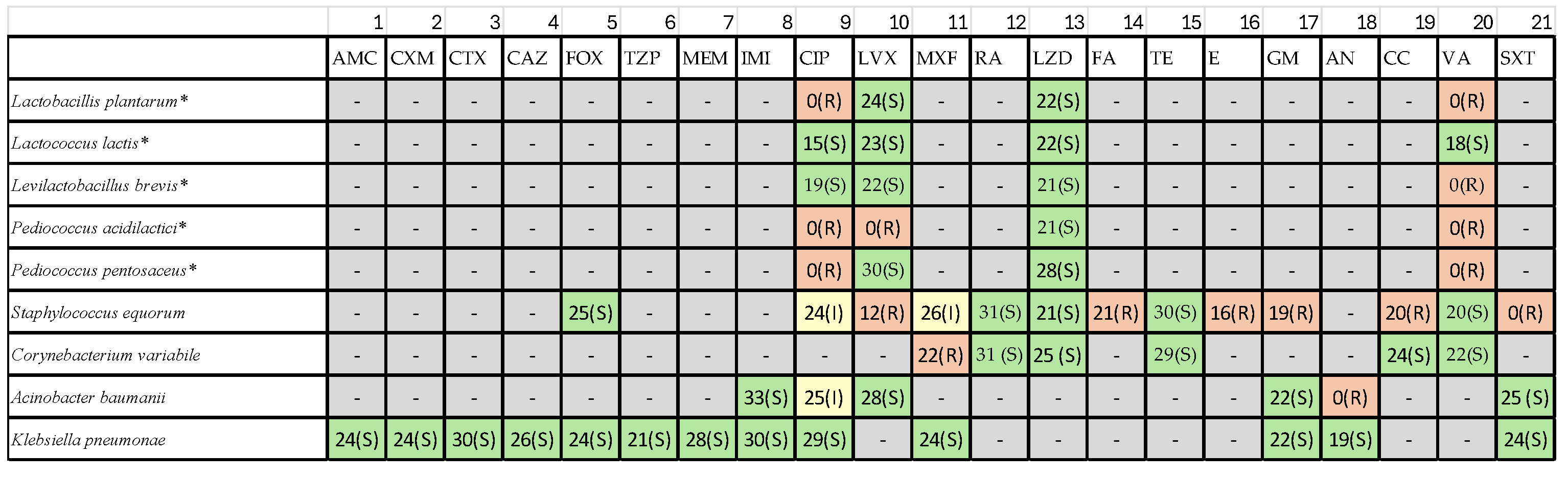

23]. A broad panel of 21 antibiotic discs (Becton Dickinson, Austria) was used (

Table 1) under the classes such as β-lactams, Fluoroquinolones, Macrolides, Tetracyclines, Aminoglycosides, Oxazolidinones, Glycopeptides and Sulfonamides.

LAB isolates were grown in MRS broth for 18–24 h, adjusted to 0.5 McFarland, and spread on Mueller–Hinton agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood where required. Plates were incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 24 h. Where LAB-specific breakpoints were not available,

Enterococcus spp. breakpoints were used as recommended for safety assessment of food-associated LAB [

24]. Control strains included

E. coli ATCC 25922,

S. aureus ATCC 29219, and

P. aeruginosa ATCC 27837.

2.4. Growth Kinetics Across pH Conditions

Growth kinetics were assessed using a Bioscreen C automated growth analysis system (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland) following Rodríguez et al. [

25] and methods adapted to cheese fermentation conditions.

Lysogeny Broth (LB, Merck, Austria) broth was adjusted to nine pH levels (2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, 5.5, 6.5, 7.0, and 8.0) using HCl or NaOH. Cultures were standardized to 0.5 McFarland (~10⁶ CFU/mL), inoculated into microplate wells (300 µL per well), and incubated at 30 °C for 72 h with continuous shaking.

Optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) was recorded every 15 min. Growth curves were smoothed using Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing (LOESS), and curves were truncated at 3600 min to remove late-stage artifacts. Differences in growth profiles were interpreted based on known physiological characteristics of LAB, yeasts, and staphylococci under acidic and near-neutral conditions.

3. Results

3.1. Antimicrobial Activity of Isolates

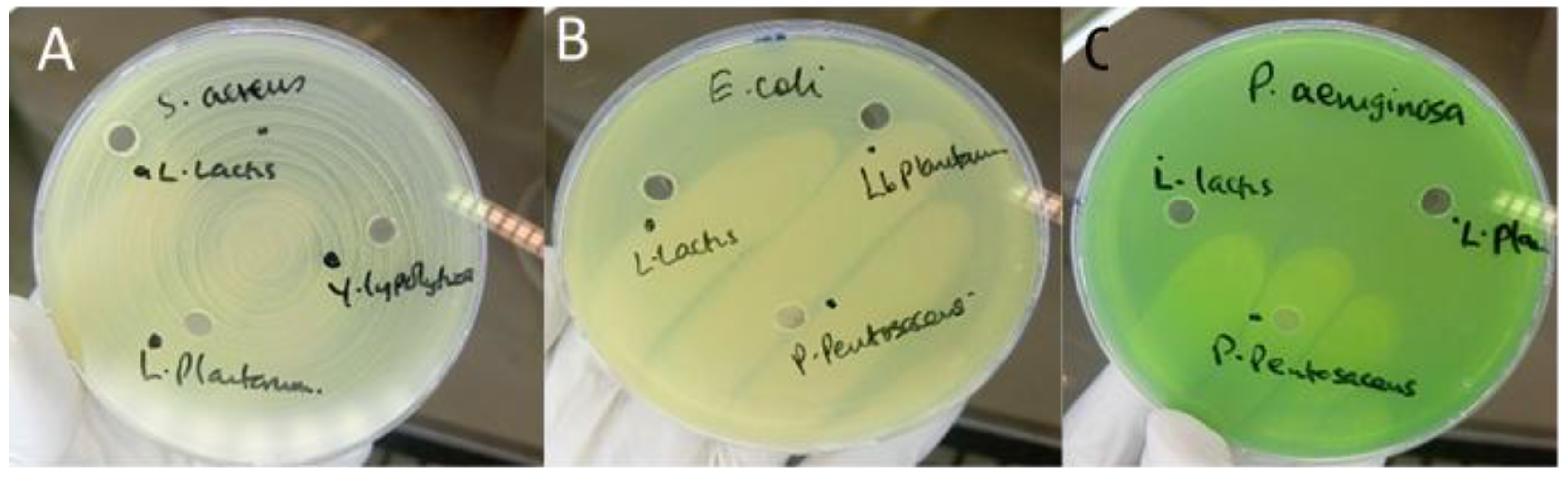

Antimicrobial screening revealed notable differences among the isolates tested. The majority of LAB strains—including

Lactococcus lactis,

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum,

Levilactobacillus brevis, and

Pediococcus acidilactici showed no detectable inhibition of

S. aureus,

Escherichia coli, or

P. aeruginosa in either agar well diffusion or disc-spot assays (

Figure 1). These findings indicate an absence of secreted antimicrobial metabolites capable of producing measurable zones of inhibition under the conditions employed.

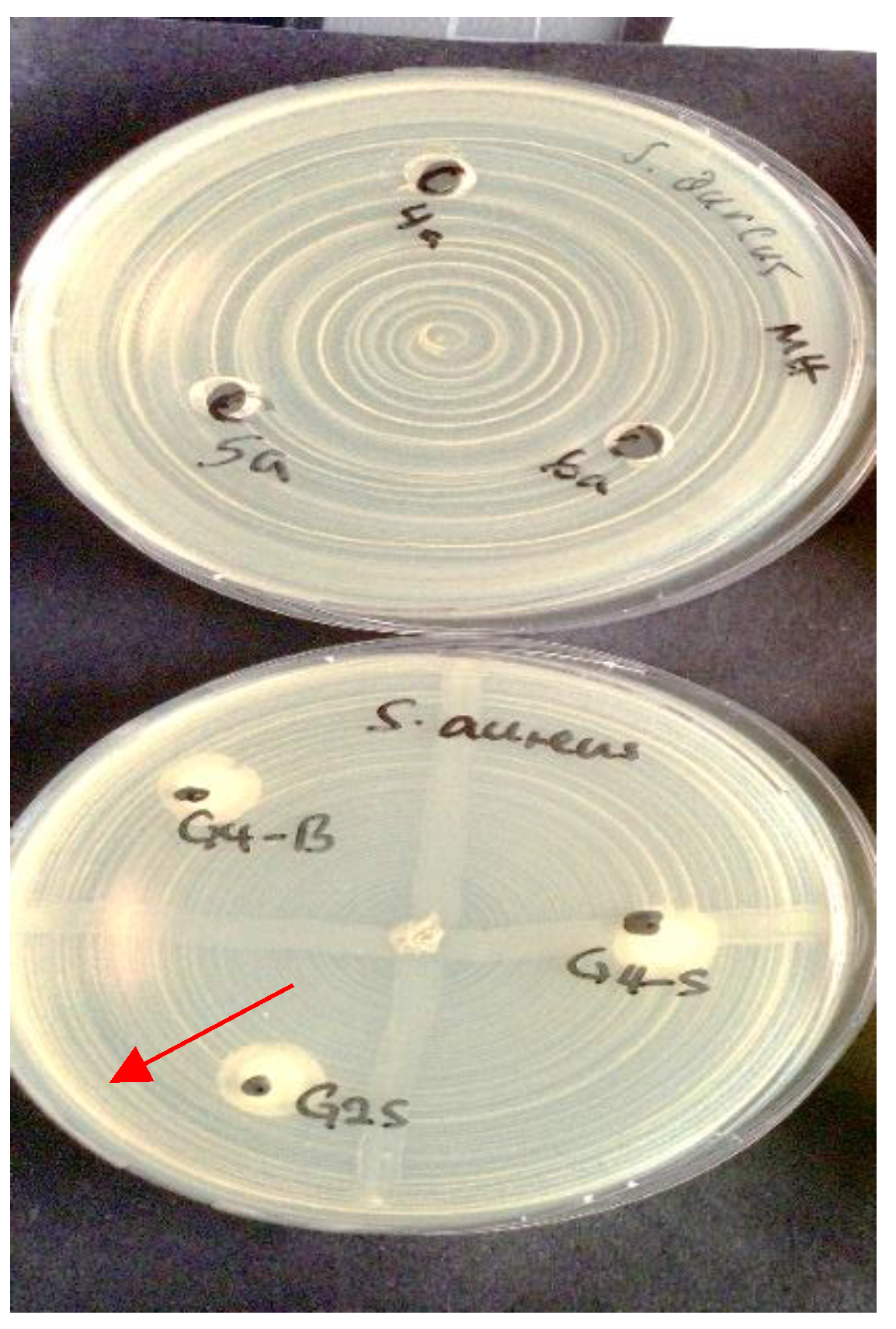

In contrast, Pediococcus pentosaceus demonstrated clear inhibitory activity against

S. aureus, producing measurable zones of inhibition in both assay formats (

Figure 2).

This activity is consistent with the strain’s known ability to produce bacteriocin-like compounds.

No isolate exhibited inhibitory effects against Gram-negative pathogens (E. coli and P. aeruginosa), which aligns with the intrinsic resistance conferred by the outer membrane barrier typical of these organisms.

3.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiles

Antibiotic susceptibility testing revealed substantial variability among isolates (

Table 2),

3.2.1. Pediococcus Species

Pediococcus acidilactici exhibited multidrug resistance, including resistance to β-lactams, Macrolides, Fluoroquinolones, Tetracycline. Pediococcus pentosaceus displayed moderate resistance, with susceptibility to rifampin and linezolid but reduced susceptibility or resistance to erythromycin and tetracycline.

3.2.2. Lactobacillales

LAB isolates in general were susceptible to Rifampin, Linezolid and Moxifloxacin. The resistance to erythromycin and tetracycline was frequently observed across multiple LAB strains.

3.2.3. Contaminant Staphylococci and Gram-Negative Bacteria

S. aureus showed expected sensitivity patterns based on EUCAST quality-control ranges. Acinetobacter baumannii contaminants exhibited high-level resistance to aminoglycosides, including amikacin—consistent with global AMR trends. These findings highlight the importance of screening artisanal cheese microbiota for transferable resistance traits to ensure safe starter culture selection.

3.3. Growth Kinetics Across pH Conditions

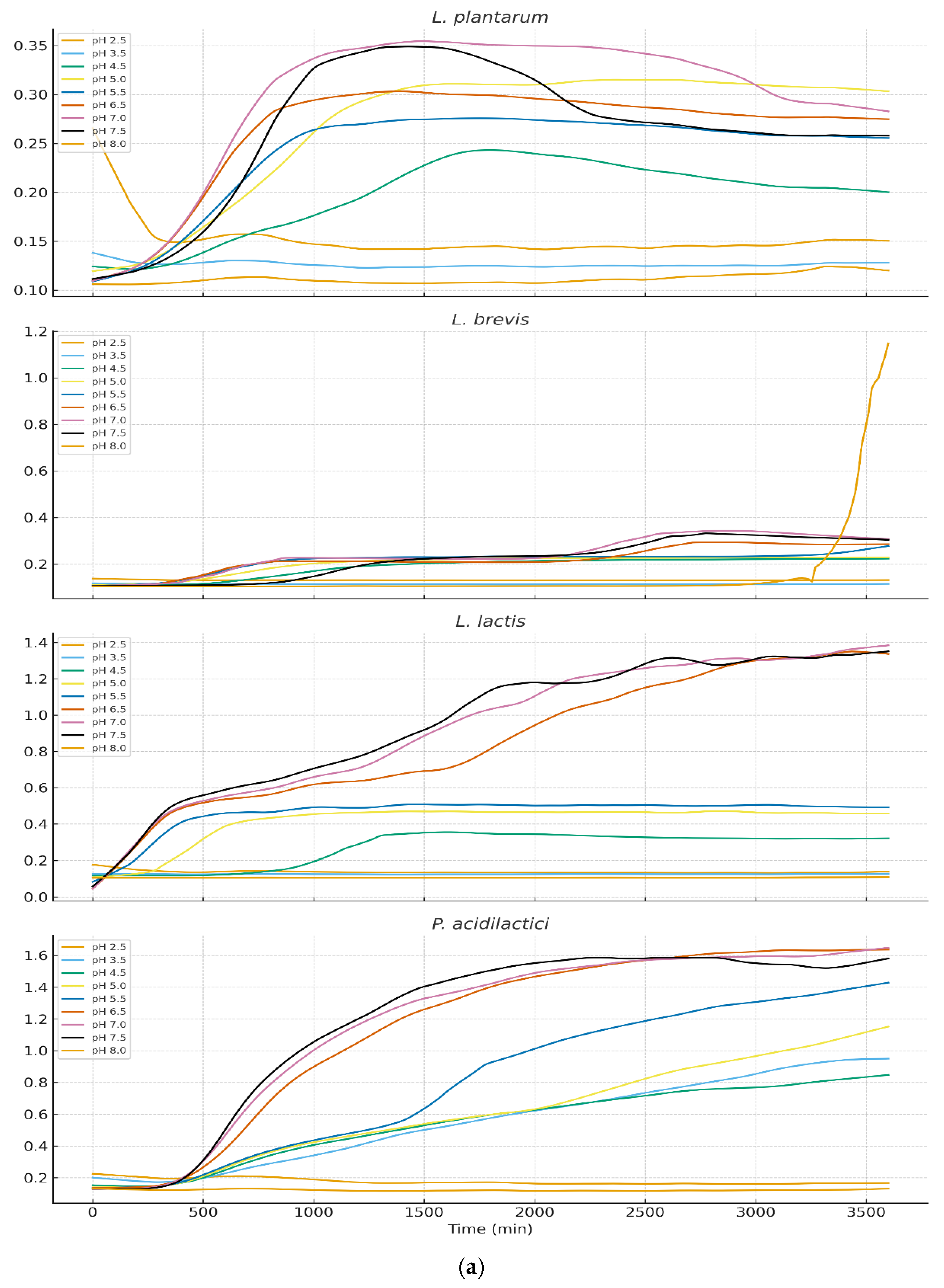

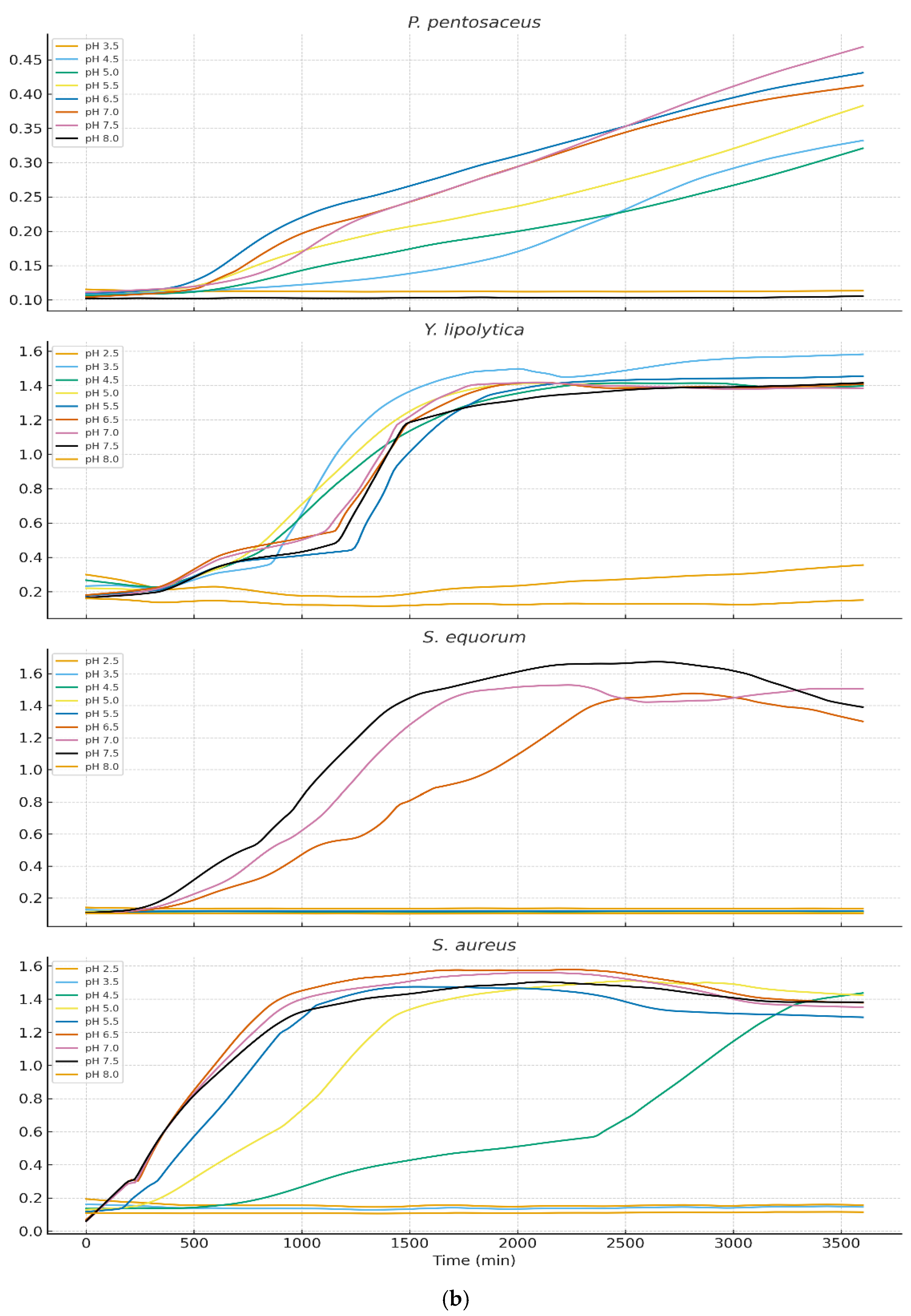

Growth behavior across nine pH levels (2.5–8.0) varied markedly among isolates (

Figure 3a and 3b). LOESS-smoothed OD₆₀₀ curves (truncated at 3600 min) illustrate clear physiological distinctions between LAB, yeasts, and staphylococci.

3.3.1. Growth of Lactic Acid Bacteria

LAB exhibited strong acid tolerance with optimal growth at pH 4.5–5.5 for Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, Lactococcus lactis, Pediococcus acidilactici. The moderate growth persisted at pH 3.5, although with prolonged lag phases. Pediococcus pentosaceus showed the highest acid tolerance, maintaining growth even at pH 3.0. These results align with the ecological role of LAB during early cheese fermentation when pH is low. Levilactobacillus brevis displayed markedly reduced acid tolerance when exposed to pH 2.5. Growth curves revealed an extended lag phase exceeding 48 hours, during which no appreciable increase in optical density was observed. Only minimal growth was detected thereafter, and in several replicates the strain failed to reach exponential growth within the incubation period. these findings confirm that L. brevis is poorly adapted to survive or proliferate at pH 2.5, exhibiting phenotypic profiles characteristic of acid-sensitive heterofermentative LAB.

3.3.2. Growth of Yeasts and Staphylococci

Yarrowia lipolytica and Staphylococcal species showed markedly different profiles. Near-neutral pH (6.5–7.5) supported optimal growth however growth below pH 4.5 was minimal or undetectable. S. equorum and S. aureus showed rapid proliferation at pH 7 but were strongly inhibited at lower pH. This pattern supports the known ecological succession in cheese: LAB dominate early (low pH), while yeasts and staphylococci proliferate during later ripening as surface pH increases.

3.3.3. Overall Physiological Trends

The data demonstrated a clear ecological separation among the microbial groups:Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) exhibited acidophilic behavior, consistent with their dominance during the early stages of fermentation when pH values are low.Yeasts and Staphylococcus spp. showed neutrophilic preferences, aligning with their roles as late-ripening, surface-colonizing microbes that thrive as the cheese environment becomes less acidic. Together, these patterns confirm pH as a primary driver of microbial niche differentiation in traditional Ugandan cheeses.

4. Discussion

4.1. Antimicrobial Activity of LAB and Yeasts

Most LAB isolates exhibited no measurable inhibition against

S. aureus,

Escherichia coli, or

P. aeruginosa. This outcome is consistent with reports showing that antimicrobial activity in LAB is highly strain-specific and influenced by environmental conditions, nutrient availability, and physiological state [

3,

11]. LAB often rely on organic acid production and competitive exclusion rather than strong bacteriocin-mediated inhibition, which may explain the absence of clear zones in both agar well diffusion and disc-spot assays.

By contrast,

Pediococcus pentosaceus displayed distinct inhibition of

S. aureus, suggesting the production of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances, a known characteristic of several

Pediococcus strains [

12,

26]. Because Gram-negative bacteria possess an outer membrane barrier that limits diffusion of many antimicrobial compounds, the lack of inhibition against

E. coli and

P. aeruginosa is expected and consistent with observations across multiple LAB species [

27].

The overall pattern suggests that the LAB and yeast isolates evaluated in this study may rely primarily on acidification, ecological competition, and biofilm-associated mechanisms, rather than broad-spectrum antimicrobial metabolite production, to influence microbial dynamics in cheese environments [

28].

4.2. Antibiotic Resistance and Safety Implications for Starter Culture Use

Antibiotic susceptibility testing revealed diverse resistance phenotypes among isolates. The multidrug resistance profile observed in

Pediococcus acidilactici is noteworthy. While

Pediococcus species are generally considered non-pathogenic and rarely cause infections, the presence of acquired antibiotic resistance genes raises concern. Such genes, if transferrable, could potentially be spread to other microorganisms in the human gastrointestinal tract, even though the species itself is not typically infectious. This is particularly relevant for food-associated lactic acid bacteria used in starter cultures, which ideally should not carry transferable resistance determinants. [

9,

24].

Resistance to macrolides and tetracycline was frequent among LAB isolates, consistent with global trends in dairy-associated LAB [

8,

10]. Fluoroquinolone resistance observed in some strains may be associated with efflux pump activity or chromosomal mutations, mechanisms widely reported in Gram-positive bacteria [

29,

30,

31].

Opportunistic contaminants such as

Acinetobacter baumannii, a well-known hospital-associated pathogen already recognized as a major concern in antimicrobial resistance, displayed resistance to aminoglycosides, including amikacin, patterns that mirror global AMR surveillance data for this species [

32,

33]. These findings underscore the importance of hygiene control in artisanal cheese production, where environmental and equipment-associated contaminants may persist [

34,

35].

International regulatory bodies such as EFSA and the FDA emphasize that starter cultures must be free of mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance [

17]. Therefore, strains exhibiting concerning resistance profiles especially

Pediococcus acidilactici require genomic screening to determine the presence or absence of plasmid-borne resistance determinants before consideration for commercial application.

4.3. Physiological Interpretation of pH-Dependent Growth Kinetics

Growth kinetics revealed clear physiological differences among isolates, reflecting their ecological roles in cheese fermentation and ripening. LAB such as

L. lactis,

Lpb. plantarum, and

Lb. brevis thrived under moderately acidic conditions (pH 4.5–5.5), consistent with their dominance during early cheese fermentation when lactose metabolism drives pH reduction. Acid tolerance in LAB is associated with mechanisms such as ATPase-mediated proton extrusion, cell membrane adaptations, and cytoplasmic pH homeostasis [

36,

37].

Pediococcus pentosaceus demonstrated exceptional acid tolerance, growing at pH levels as low as 3.0. This resilience aligns with previous findings describing robust acid-stress response systems in

Pediococcus spp., including cell-wall reinforcement and protective solute transport systems [

38].

In contrast,

Yarrowia lipolytica,

Staphylococcus equorum, and

S. aureus exhibited poor growth below pH 4.5 but proliferated rapidly under near-neutral conditions (pH 6.5–7.5). These patterns match their known ecological roles as late-ripening surface-associated microbiota, which colonize cheese rinds after LAB-driven acidification subsides and surface pH increases due to yeast-driven deacidification [

39,

40,

41].

This sequential occupation of acidic versus neutral microenvironments underscores pH as a key selective force structuring microbial succession and niche specialization during cheese ripening. Such findings are consistent with classical cheese ecology and reinforce the importance of acid dynamics in shaping microbial community composition in artisanal Ugandan cheese varieties.

4.4. Technological and Application Implications

The ability of LAB isolates to grow under acidic conditions suggests suitability for early fermentation steps, particularly for cheeses produced under artisanal conditions with limited pH control. Lpb. plantarum and L. lactis demonstrated desirable growth robustness, supporting their potential as starter or adjunct culture candidates, pending safety evaluation.

Pediococcus pentosaceus, with its selective antimicrobial activity, may represent a promising bioprotective culture for inhibiting Gram-positive spoilage organisms—although further characterization of its antimicrobial compounds is warranted.

However, the detection of multidrug-resistant LAB emphasizes the need for rigorous safety screening. Any strain intended for starter culture development must undergo whole-genome sequencing, assessment for mobile resistance genes, evaluation for virulence factors, verification of metabolic suitability (e.g., gas production, proteolytic activity).

4.5. Relevance to Ugandan Cheese Production Systems

Ugandan cheeses are produced under conditions characterized by raw milk use; limited temperature control; absence of standardized cultures; manual handling and artisanal practices. These factors contribute to high microbial diversity, which can be advantageous for sensory complexity but also increases risks related to spoilage and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) dissemination. The present study provides foundational insights into the microbial ecology of Ugandan cheeses, identifying strains with technological value while highlighting safety concerns that must be addressed through genomic and functional characterization.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a detailed characterization of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts isolated from Ugandan ripened cheeses, revealing substantial microbial diversity with functional traits that influence their technological suitability. Microbial interactions appear driven primarily by acidification and competitive dynamics rather than strong bacteriocin activity. Antibiotic resistance patterns varied considerably, with some strains—such as Pediococcus acidilactici—showing multidrug resistance, underscoring the need for strict safety assessments, including genomic screening for mobile resistance genes. The detection of contaminants like Acinetobacter baumannii further highlights the importance of improved hygiene in artisanal production settings. Growth kinetics across nine pH conditions demonstrated clear ecological separation, with LAB thriving under acidic conditions typical of early fermentation, while Yarrowia lipolytica and staphylococci favored near-neutral pH associated with later ripening stages. Collectively, these findings identify promising LAB candidates, particularly Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, Lactococcus lactis, and Pediococcus pentosaceus, for future starter or adjunct culture development, while emphasizing the need to exclude antibiotic-resistant strains. Continued research through whole-genome sequencing, bacteriocin analysis, and controlled fermentation trials will be essential to validate the safety and technological performance of these candidate cultures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.M.M., E.M and G.Z.; Methodology: A.M.M., E.M., and C.K.; Investigation: A.M.M.; Formal Analysis: A.M.M. and P.A.W.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: A.M.M.; Writing—Review and Editing: E.M., G.Z. and C.K.; Supervision: E.M., G.Z. and C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Kyambogo University, the Medical University of Graz, and the ERASMUS+ mobility program. No additional external funding was received.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Kyambogo University, the Medical University of Graz, and the ERASMUS+ programme for providing laboratory facilities, mobility support, and technical assistance throughout this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in data collection, analysis, or interpretation; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Afshari, R.; Pillidge, C.J.; Read, E.; Rochfort, S.; Dias, D.A.; Osborn, A.M.; Gill, H. Microbiota and metabolite profiling combined with integrative analysis for differentiating cheeses of varying ripening ages. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 592060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruvalcaba-Gómez, J.M.; Piña-Gutiérrez, J.M.; Guerrero-Barrera, A.L.; Pérez-Rodríguez, F.; Manzanares-Papayanopoulos, L.I.; Ascencio, F. Bacterial succession through artisanal processing and seasonal effects defining bacterial communities of raw-milk Adobera cheese. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, C.C.G.; Silva, S.P.M.; Ribeiro, S.C. Application of bacteriocins and protective cultures in dairy food preservation. Microorganisms 2018, 6, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebbia, S.; Lamberti, C.; Lo Bianco, G.; Cirrincione, S.; Laroute, V.; Cocaign-Bousquet, M.; Cavallarin, L.; Giuffrida, M.G.; Pessione, E. Antimicrobial potential of food lactic acid bacteria: Bioactive peptide decrypting and bacteriocin production. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frediansyah, A.; Nisa, I.K.; Permatasari, D.A. Fermentation of Jamaican cherry juice using Lactobacillus plantarum as starter culture. Molecules 2021, 26, 149. [Google Scholar]

- De Filippis, F.; Genovese, A.; Ferranti, P.; Gilbert, J.A.; Ercolini, D. Metatranscriptomics reveals temperature-driven functional changes in microbiome impacting cheese maturation rate. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatoum, R.; Labrie, S.; Fliss, I. Antimicrobial and probiotic properties of yeasts: From fundamentals to applications. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floris, I.; Bisutti, V.; Sassella, A.; Drigo, I.; Zaninelli, M.; Losasso, C. Antibiotic resistance in lactic acid bacteria from raw milk dairy products. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, N.; Aljaloud, S.O.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Antimicrobial resistance: A growing serious threat for global public health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarinou, C.S.; Papadimitriou, K.; Sakkas, L.; Georgalaki, M.D.; Tsakalidou, E. Mapping technological and functional properties of indigenous LAB from Greek cheeses. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choinska, R.; Piasecka-Jóźwiak, K.; Chabłowska, B.; Dumka, J.; Łukaszewicz, A. Biocontrol ability of yeasts and production of antimicrobial volatile compounds. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumariya, R.; Garsa, A.K.; Rajput, Y.S.; Sood, S.K.; Akhtar, N.; Patel, S. Bacteriocins: Classification, synthesis, mechanism of action and resistance development. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 128, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Degraeve, P.; Oulahal, N. Bioprotective yeasts for food safety improvement. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oštarić, F.; Jeličić, I.; Tratnik, L.; Božanić, R. Innovative technologies in cheese production: A review. Processes 2022, 10, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomas, E.; Sakaridis, I.; Boukouvala, E.; Karatzia, M.-A.; Ekateriniadou, L.V.; Samouris, G. Indigenous LAB from raw Graviera cheese and technological properties. Foods 2023, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, B.E.; Button, J.E.; Santarelli, M.; Dutton, R.J. Cheese rind microbial communities. Cell 2014, 158, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarquero, D.; Bodelón, R.; Flórez, A.B.; Fresno, J.M.; Renes, E.; Mayo, B.; Tornadijo, M.E. Safety and technological assessment of LAB for cheese starter cultures. LWT 2023, 180, 114709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastman, E.K.; Kamelamela, N.; Norville, J.W.; Cosetta, C.M.; Dutton, R.J.; Wolfe, B.E. Biotic interactions shape distributions of Staphylococcus species. mBio 2016, 7, e01157–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2016, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.; Pauli, M.; Bazerque, P. An antibiotic assay by the agar-well diffusion method. Acta Biológica y Farmacéutica 1990, 1, 113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, E.; Fan, L.; Yan, J.; Jiang, Y.; Doucette, C.; Fillmore, S.; Walker, B. A. Influence of culture media, pH and temperature on growth and bacteriocin production of bacteriocinogenic lactic acid bacteria. AMB Express 2018, 8(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; 31st ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: 2021.

- EUCAST. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing guidelines. European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing 2021.

- Morandi, S.; Silvetti, T.; Vezzini, M.; Morozzo, E.; Brasca, M. Antibiotic resistance and safety of LAB in raw milk cheese. J. Food Saf. 2015, 35, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Membre, J. M., Leporq, B., Vialette, M., Mettler, E., Perrier, L., & Zwietering, M. H. Experimental protocols and strain variability of cardinal values (pH and aw) of bacteria using Bioscreen C: Microbial and statistical aspects. In L. Axelsson, E. S. Tronrud, & K. J. Merok (Eds.), Food Micro 2002: Microbial adaptation to changing environments (pp. 143–146).

- Qiao, Y.; et al. Effect of bacteriocin-producing Pediococcus acidilactici strains on the immune system and intestinal flora of normal mice. Food Science and Human Wellness 2022, 11(1), 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warda, A.K.; et al. Gram-negative resistance to bacteriocins. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 855093. [Google Scholar]

- Mgomi, F.C.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, G.; Yang, Z. LAB biofilms and antimicrobial potential. Biofilm 2023, 5, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anes, J.; McCusker, M.P.; Fanning, S.; Martins, M. Efflux pump systems in antibiotic resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 587. [Google Scholar]

- Tenover, F.C. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, K.; Ding, C.; et al. Resistance mechanisms in multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.S.; et al. Acinetobacter diversity and resistance in dairy environments. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 350. [Google Scholar]

- Luísa, C.S.A.; Visca, P.; Towner, K.J. Evolution of A. baumannii as a global pathogen. Pathog. Dis. 2014, 71, 292–301. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, S.R.L.; Shrivastava, P.S.; Ramasamy, J. WHO priority AMR pathogen list. J. Med. Soc. 2018, 32, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, M.J.; Legido-Quigley, H.; Hsu, L.Y. Antimicrobial resistance in One Health systems. Adv. Sci. Tech. Sec. Appl. 2020, 209–229. [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson, L. Lactic acid bacteria physiology and stress responses. In Lactic Acid Bacteria; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, P.; et al. Cytoplasmic pH homeostasis in acid-tolerant bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e02783–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Han, Y.; Zhou, Z. Acid stress response in Pediococcus pentosaceus. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 817–825. [Google Scholar]

- Mathe, C.; Nicaud, J.-M. Lipid metabolism and ecology of Yarrowia lipolytica. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, K.; Heilmann, C.; Peters, G. Pathogenicity of staphylococci at low pH. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, B.E.; Dutton, R.J. Microbial succession in cheese rinds. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).