1. Introduction

Granitic rocks in Southeast Asia serve as key geological markers of magmatic and tectonic processes associated with the amalgamation of continental fragments along the northern margin of Gondwana. In Thailand, granitoids are broadly categorized into three principal belts: Eastern, Central, and Western in which each representing distinct tectonomagmatic domains and evolutionary histories [

1]. The Western Granitoid Belt (WGB) is particularly significant due to its complex magmatic evolution, structural framework, and metallogenic potential, especially for tin (Sn), tungsten (W), and lithium (Li) mineralization [

2,

3].

The WGB extends from southern Myanmar through western Thailand into Peninsular Malaysia and is underlain by the Sibumasu Terrane, a microcontinental block derived from Gondwana that collided with the Indochina Terrane during the Late Paleozoic to Mesozoic[

4]. This continental convergence triggered widespread crustal melting and the emplacement of both I-type and S-type granites, with magmatism spanning from the Triassic to the Paleogene. For example, the Tak Batholith represents arc-related I-type granitoids formed during subduction processes [

5], whereas the southern WGB encompassing the Ranong, Lam Pi, Ban Lam Ru, and Phuket areas comprises evolved S-type and A-type granites that are predominantly ilmenite-series and peraluminous, indicating derivation through crustal anatexis [

1].

Zircon U–Pb dating of these granitoids reveals multiple magmatic episodes. Granites from Ban Lam Ru, Ranong, and Phuket yield Late Cretaceous ages (~88–84 Ma), while younger intrusions such as the Lam Pi body crystallized at ~60 Ma [

1,

6]. These ages correspond to syn- to post-collisional phases following the Sibumasu–West Burma collision. Geochemically, negative Eu anomalies coupled with enrichment in Nb, U, Ta, and light rare earth elements (LREEs) indicate advanced magmatic differentiation under reducing, crustal-dominated conditions [

3,

7].

From a metallogenic perspective, the WGB forms part of the Southeast Asian Tin Belt, one of the world’s most important provinces for rare and strategic metals. Tin–tungsten–lithium mineralization is closely associated with greisen-bordered vein systems, pegmatites, and highly evolved granites [

8,

9]. Lepidolite-bearing pegmatites in Phang Nga, for example, are spatially linked with fractionated S-type granites [

2]. Fluid inclusion studies show low to moderate salinity aqueous and aqueous–carbonic inclusions, suggesting a deep-seated plutonic origin and contact metamorphic overprinting [

9]. Comparative studies in southern Myanmar further support this tectonomagmatic model, documenting peraluminous, Sn–W-bearing granites of syn- to post-collisional origin with U–Pb zircon ages of ~85–83 Ma [

10,

11].

The tectonic evolution of the WGB reflects complex interactions between crustal shortening, slab rollback, and transtensional shearing. The transition from compressional to extensional regimes during post-collisional collapse facilitated magma ascent through ductile shear zones and emplacement at upper crustal levels [

12,

13,

14]. Petrologically, I-type granites are distinguished by hornblende–biotite assemblages, magnetite ± ilmenite, and high Zr and LREE contents, whereas S-type granites display ilmenite–sulfide assemblages, high A/CNK ratios, and sedimentary isotopic signatures [

5,

12,

13]. However, overlapping compositional and textural characteristics between these granite types suggest source heterogeneity and hybrid magmatic processes [

14].

Within this regional framework, the granitoids of Kanchanaburi Province occupy a critical yet understudied segment of the WGB. Despite their potential significance for understanding the crustal evolution of western Thailand, detailed investigations remain scarce. Whole-rock geochemical and isotopic data are limited, and most interpretations rely on extrapolation from adjacent regions [

15,

16]. Moreover, there have been no in situ studies of accessory minerals such as zircon or apatite, which are essential for constraining magma evolution and mineralization potential [

16,

17]. As a result, petrogenetic interpretations for Kanchanaburi granitoids remain largely inferential, and their relationship to regional metallogenic events is poorly defined.

To address these gaps, this study integrates petrographic analysis, whole-rock geochemistry, zircon U–Pb geochronology, and magnetic susceptibility measurements to (1) classify granitoid types across key exposures in Kanchanaburi Province, (2) reconstruct their petrogenesis and emplacement history within a tectonic framework, and (3) assess their implications for rare-metal mineralization within the broader Southeast Asian Tin Belt.

2. Tectonic Framework and Geological Setting

Kanchanaburi Province in western Thailand is situated along the tectonic boundary between the Sibumasu and Indochina terranes. This suture zone preserves the record of the Indosinian Orogeny, which occurred during the Late Triassic and was marked by crustal thickening, regional metamorphism, and widespread granitoid intrusions [

18]. The dominant S-type granitoids in the region, particularly those found in the Central Granite Belt, are indicative of anatexis of metasedimentary crust and are associated with the Southeast Asian Tin Belt [

2,

18].

In addition to the Triassic magmatism, the region also underwent significant tectonic reactivation during the Cenozoic. This was driven by the development of major strike-slip systems such as the Mae Ping Shear Zone (MPSZ), which facilitated the emplacement of syn-kinematic granitoids and gneissic rocks dated to 45–32 Ma [

18]. These tectonic processes contributed to prolonged magmatism, deformation, and crustal exhumation that extended into the Eocene–Oligocene.

The granitoids of Kanchanaburi belong to the Western Granite Belt (WGB), which forms part of the Sibumasu Terrane and represents the westernmost magmatic province of Thailand [

8,

19,

20]. The WGB consists predominantly of Late Triassic to Early Jurassic peraluminous S-type, ilmenite-series granites, emplaced during and shortly after the collision between the Sibumasu and Indochina terranes. These granites exhibit low magnetic susceptibility, high-K calc-alkaline to shoshonitic affinity, and enrichment in Rb, Th, and U, indicating crustal anatexis under reduced redox conditions [

21,

22]. Subsequent Late Cretaceous granites (85–70 Ma) in Kanchanaburi and adjacent areas record post-collisional to within-plate extensional magmatism, related to reactivation of the Sibumasu crust and associated Sn–W metallogeny [

8,

23]. This contrasts with the more oxidized I-type and magnetite-series granitoids of the Central Belt and Sukhothai arc, reflecting distinct crustal sources and redox regimes across the Indosinian suture.

Geologically, the province is underlain by a variety of rock units ranging in age from Precambrian to Quaternary. These include basement rocks such as gneiss, quartzite, and marble in the west, and sedimentary successions composed of shale, sandstone, volcaniclastic rocks, and carbonates in other parts of the province. Triassic red beds and Jurassic clastic rocks dominate the central and eastern zones, while Quaternary alluvium and colluvium cover the lowland areas. Granitoid intrusions are primarily Triassic S-type granites and Cretaceous biotite-hornblende granites and granodiorites. The S-type granitoids show peraluminous signatures with high aluminum saturation indices (ASI > 1.1), enrichment in Rb, and depletion in Ba, Nb, and Ti, pointing to a pelitic crustal source [

7].

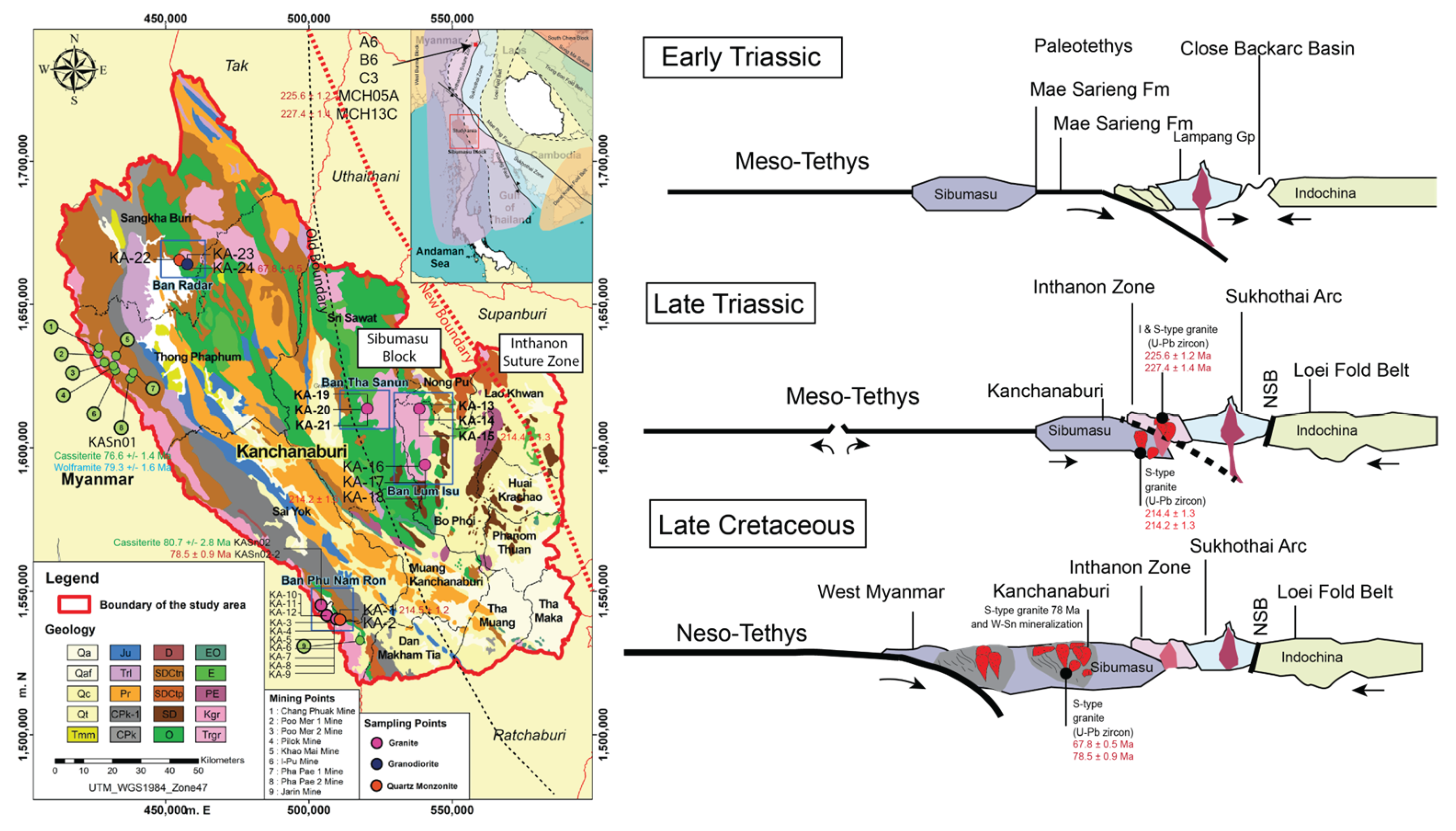

U–Pb zircon geochronology constrains the emplacement of the Triassic granitoids to ca. 211 Ma, while zircon ages from the Mae Ping Shear Zone indicate a younger magmatic phase between 45–32 Ma associated with strike-slip tectonics [

18]. Structurally, the province is transected by NW–SE and NE–SW trending faults and shear zones. These structures not only controlled magma emplacement but also played a significant role in localizing Sn-W-Zn-Pb mineralization, particularly near mining areas such as Bo Phloi, Pilok, and Chang Phuak (

Figure 1).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Petrography

Seventy-three granitoid samples were collected from four key areas along Kanchanaburi Province: [

1] Ban Phu Nam Ron, [

3] Ban Lum Isu, [

1] Ban Tha Sanun, and [

1] Ban Radar (

Figure 1).

Petrographic analysis was conducted on thin sections using a Nikon polarized light microscope. For each sample, a minimum of 2,000 points were counted to determine the modal abundances of constituent minerals (

Table 1). Magnetic susceptibility measurements were performed in the field using a portable magnetic susceptibility meter to characterize the magnetic behavior of the granitoids.

3.2. Whole-Rock Geochemistry

Loss on ignition (LOI), which is essential for assessing moisture content and volatile components in rocks, was determined by heating powdered samples (0.5 g) at 110 °C for 1 hour to assess moisture, followed by heating at 900 °C for 1 hour to measure volatile loss. Major element compositions were analyzed using a PANalytical Zetium PW5400 X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer (wavelength-dispersive system) at the Radiation Laboratory, Mahidol University, Kanchanaburi Campus, Thailand. For XRF analysis, samples were prepared as fused glass beads by mixing the LOI-analyzed powder with 6.5 g of flux composed of 49.75% lithium tetraborate (LiB₄O₇), 49.75% lithium metaborate (LiBO₂), and 0.5% lithium bromide (LiBr).

3.3. LA-ICPMS U-Pb Geochronology

The selected seven granitoid samples were analyzed for zircon dating using a quadrupole Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (LA-ICP-MS) at the Centre for Ore Deposit and Earth Sciences (CODES), University of Tasmania (UTAS), Australia. The selected rock samples were crushed, and approximately 500 g of rock chips were repeatedly ground in a Cr-steel ring mill to achieve a grain size of less than 400 µm. Heavy minerals were initially separated using gold pans, followed by magnetic separation with a handheld magnet. Zircon grains, along with other heavy minerals such as apatite, monazite, and titanite, were handpicked and mounted on double-sided adhesive tape. Epoxy resin was then poured into a 25 mm diameter mold to embed the grains. The mounts then were taken to dry in the oven under 60 °C. Once dried, samples were polished using sandpaper and a polishing lap to expose internal grain surfaces. The polished mounts were subsequently cleaned in distilled water using an ultrasonic bath. Detailed analytical procedures on the LA-ICP-MS are outlined in [

26].

Cassiterite and wolframite were also separated from tin-tungsten-bearing granitoid samples (KASn01 and KASn02) to perform U-Pb dating on rock chips mounted into 1-inch epoxy resin mount at the CODES, UTAS. The detailed analyses and calibration with standards are described in [

27].

Data reduction was accomplished using the LADR software developed by the Norris Scientific. The resulting geochronological data were processed and visualized using CODES in-house developed application and IsoplotR [

28] to generate age calculation, concordia and other statistical age diagrams, e.g., probability density plots. Complex zonation within individual crystals was examined using interval integration in the LADR software, applied specifically to grains exhibiting compositional heterogeneity. Trace element data from zircons were filtered to remove analyses that potentially affected by commonly found mineral inclusions in zircons (e.g., apatite, titanite, monazite), which can present anomalously high concentrations. Analyses were excluded using the following thresholds: La > 2 ppm, Fe > 5,000 ppm, P > 2,000 ppm, or Ti > 50 ppm. The filtered data were imported into the ioGAS software for geochemical analysis and visualization

.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Descriptions

Figure 2 shows representative hand specimens and photomicrographs of the studied granitoid samples under a polarizing microscope. None of the samples exhibit linear structures. All samples display medium- to coarse-grained granular textures without any preferred orientation. The rocks are mainly composed of quartz (Qz), plagioclase [

15], potassium feldspar (Kfs), and biotite (Bt), with variable amounts of muscovite [

30] and hornblende (Hbl) (

Table 1).

Sample KA-9 from Ban Phu Nam Ron shows a monzogranitic texture characterized by abundant K-feldspar, plagioclase, and quartz, with minor tourmaline (Tmr) and magnetite (Mag). Sample KA-10 from the same locality contains quartz, K-feldspar, plagioclase, biotite, and clinopyroxene (Cpx). Samples KA-3 from Ban Phu Nam Ron and KA-21 from Ban Tha Sanun are composed predominantly of quartz, plagioclase, K-feldspar, and biotite, with muscovite and magnetite occurring as accessory phases. Sample KA-16 from Ban Lum Isu consists of quartz, plagioclase, biotite, and muscovite, with accessory zircon (Zr) and apatite (Apt). Sample KA-21 also contains biotite and hornblende with minor titanite (Ttn) and magnetite, indicating a more mafic mineral assemblage. Samples MCH13C and MCH05A from the Mae Chan area exhibit coarse-grained textures dominated by quartz, plagioclase, and K-feldspar, typical of granitic to granodioritic composition. Accessory minerals observed in most samples include zircon, apatite, ilmenite, and titanite.

The modal mineral compositions of the studied samples on a Q–A–P (Quartz–Alkali Feldspar–Plagioclase) ternary diagram (after [

29]) (

Figure 3). The majority of samples plot within the quartz rich granitoid field, with a few extending toward syeno-granite and monzogranite compositions. This classification supports petrographic observations, indicating that the rocks range from peraluminous granitic to intermediate compositions formed under similar magmatic conditions but with variable feldspar proportions.

4.2. Magnetic Susceptibility

Magnetic susceptibility values of the studied granitoid samples (

Figure 4). Granitic rocks are classified as ilmenite-series when their magnetic susceptibility lower than 3 × 10

-3 SI units and as magnetite-series when it is higher [

19]. The low magnetic susceptibility values indicate that the studied granitoids belong to the ilmenite-series, suggesting that they crystallized from relatively reduced magmas. Such reduced conditions likely reflect partial melting or assimilation of organic-rich sedimentary material in the source region [

19,

21]. The magnetic susceptibility values of the studied samples range from 0.0001 × 10

-3 to 0.16 × 10

-3 SI units, which are well below the 3 × 10

-3 SI threshold, indicating that all samples belong to the ilmenite-series. Samples from Ban Phu Nam Ron, Ban Lum Isu, and Ban Tha Sanun exhibit very low magnetic susceptibilities (<0.002 × 10

-3 SI), consistent with reduced magmatic conditions. Samples from Ban Radar show slightly higher values (0.0177–0.0199 × 10

-3 SI), but still within the ilmenite-series range, suggesting minor local oxidation during emplacement. The Mae Chan samples (MCH05A, MCH13C, A6, B6, and C3) display the highest magnetic susceptibility values (0.07–0.16 × 10

-3 SI), yet they remain below the magnetite-series boundary. These overall low values imply that the studied granitoids crystallized under reduced redox conditions, likely influenced by organic-rich or sedimentary material in their crustal source regions.

4.3. Whole-Rock Geochemical Compositions

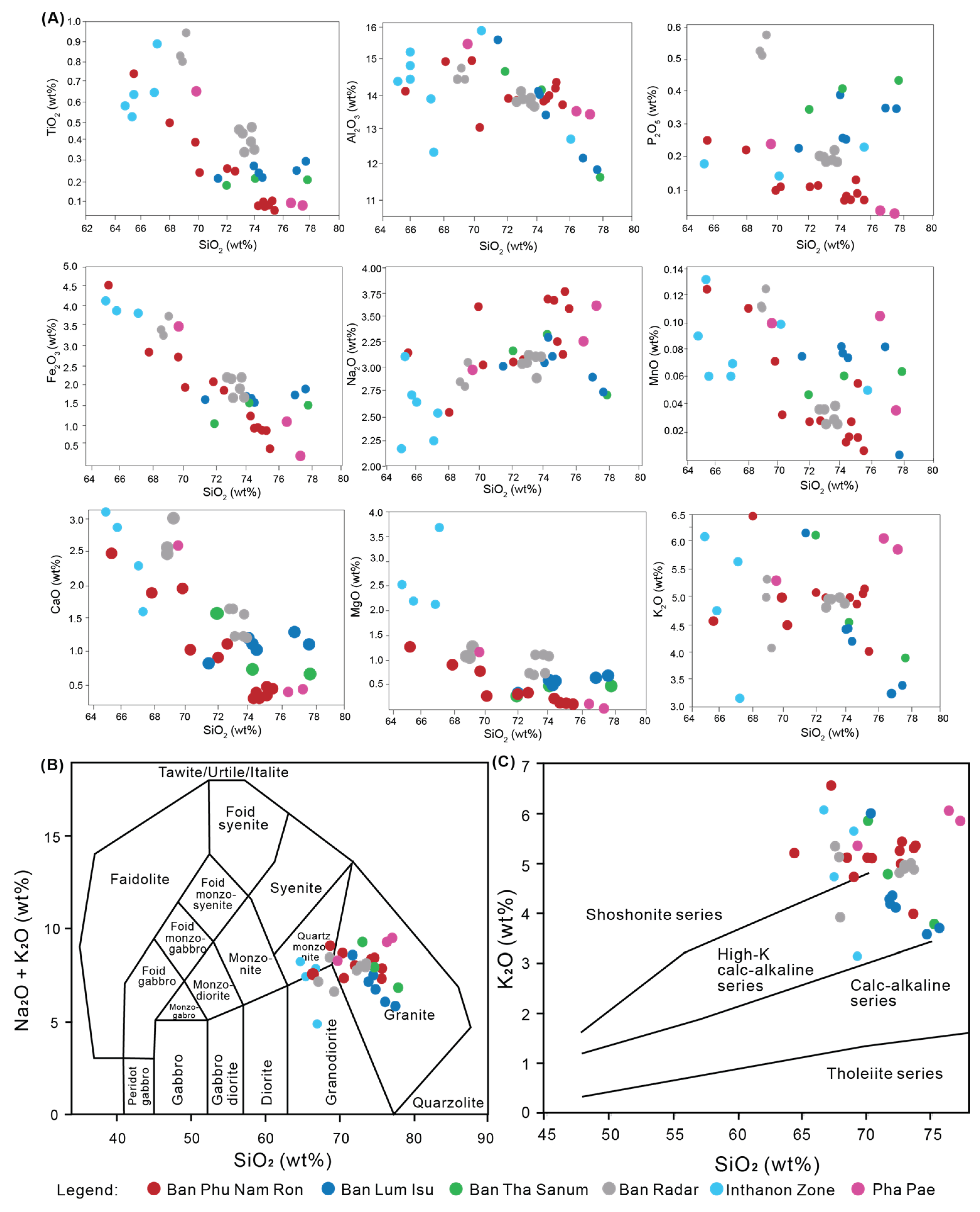

The results of whole-rock geochemical analysis are presented in

Table 2. The major element compositions of the studied granitoid samples show relatively narrow ranges in SiO₂ (65.3–77.9 wt%) and moderate variations in Fe₂O₃

t, MgO, CaO, Na₂O, and K₂O (

Table 2,

Figure 5A). Most of all studied granitoid samples plot within the granite field on the total alkali versus SiO₂ (TAS) diagram (

Figure 5B), confirming their felsic composition. This distribution indicates modest modal variability across the suite but an overall granitic affinity. On the K₂O versus SiO₂ diagram (

Figure 5C), most samples fall within the high-K calc-alkaline to shoshonite series. These characteristics indicating that the magmas were moderately to strongly enriched in potassium during differentiation. The samples exhibit decreasing Fe₂O₃

t, MgO, CaO, TiO₂, and P₂O₅ with increasing SiO₂, suggesting fractional crystallization of mafic minerals such as biotite, hornblende, and magnetite, together with plagioclase [

30]. Magnetic susceptibility data indicate that all samples belong to the ilmenite-series [

19], implying crystallization under reduced redox conditions typical of magmas derived from crustal sources containing organic matter [

24]. Such enrichment is typical of crustal-derived granitoids emplaced in continental arc or post-collisional tectonic settings [

31], where partial melting of the lower crust and assimilation of sedimentary material contribute to elevated K₂O contents. Combined with their ilmenite-series affinity and reduced redox conditions, these features suggest that the granitoids were generated from I-type magmas [

30,

32] derived from a mixed crustal source under low oxygen fugacity, evolving through fractional crystallization and limited interaction with oxidized mantle-derived components.

Table 2.

Results of whole-rock geochemical analysis of the studied granite samples.

Table 2.

Results of whole-rock geochemical analysis of the studied granite samples.

| Location |

Ban Phu Nam Ron |

| Sample No. |

KA-1 |

KA-2 |

KA-3 |

KA-4 |

KA-5 |

KA-6 |

KA-7 |

KA-8 |

KA-9 |

KA-10 |

| SiO2 (wt%) |

67.95 |

65.37 |

69.77 |

75.16 |

74.48 |

74.28 |

75.09 |

74.65 |

75.45 |

72.05 |

| TiO2

|

0.50 |

0.74 |

0.40 |

0.10 |

0.09 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

0.07 |

0.05 |

0.27 |

| Al2O3

|

15.01 |

14.14 |

15.00 |

14.38 |

13.88 |

13.80 |

14.24 |

14.00 |

13.75 |

13.89 |

| Fe2O3(tot)

|

2.82 |

4.50 |

2.71 |

0.85 |

0.93 |

1.26 |

0.87 |

0.92 |

0.41 |

2.11 |

| MnO |

0.11 |

0.12 |

0.07 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

0.01 |

0.03 |

| MgO |

0.90 |

1.25 |

0.78 |

0.12 |

0.16 |

0.20 |

0.10 |

0.09 |

0.03 |

0.30 |

| CaO |

1.91 |

2.50 |

1.95 |

0.47 |

0.38 |

0.30 |

0.37 |

0.32 |

0.46 |

0.93 |

| Na2O |

2.55 |

3.15 |

3.61 |

3.77 |

3.66 |

3.67 |

3.12 |

3.25 |

3.59 |

3.04 |

| K2O |

6.45 |

4.54 |

4.99 |

5.11 |

5.30 |

4.97 |

5.03 |

4.84 |

4.00 |

5.07 |

| P2O5

|

0.22 |

0.25 |

0.09 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

0.06 |

0.12 |

0.07 |

0.07 |

0.10 |

| LOI |

0.56 |

0.26 |

0.32 |

0.38 |

0.24 |

0.40 |

0.42 |

0.28 |

0.26 |

0.98 |

| Total |

98.98 |

96.82 |

99.68 |

100.44 |

99.21 |

99.04 |

99.51 |

98.52 |

98.06 |

98.76 |

Table 2.

(cont.).

| Location |

Ban Phu Nam Ron |

Ban Lum Isu |

| Sample No. |

KA-11 |

KA-12 |

KA-34 |

KA-35 |

KA-36 |

KA-37 |

KA-13 |

KA-14 |

KA-15 |

KA-16 |

KA-17 |

| SiO2 (wt%) |

72.61 |

70.17 |

76.95 |

70.63 |

77.47 |

71.24 |

76.88 |

77.68 |

73.97 |

74.40 |

71.39 |

| TiO2

|

0.26 |

0.24 |

0.17 |

0.59 |

0.08 |

0.28 |

0.25 |

0.31 |

0.28 |

0.22 |

0.21 |

| Al2O3

|

13.84 |

13.07 |

13.71 |

15.29 |

14.27 |

16.29 |

12.21 |

11.92 |

14.11 |

13.42 |

15.58 |

| Fe2O3(tot)

|

1.86 |

1.95 |

1.38 |

3.37 |

0.90 |

1.87 |

1.73 |

1.89 |

1.71 |

1.56 |

1.63 |

| MnO |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.10 |

0.07 |

0.12 |

0.08 |

0.00 |

0.08 |

0.07 |

0.07 |

| MgO |

0.31 |

0.28 |

0.17 |

1.00 |

0.06 |

0.53 |

0.62 |

0.67 |

0.61 |

0.57 |

0.57 |

| CaO |

1.13 |

1.06 |

0.66 |

1.47 |

0.31 |

1.87 |

1.32 |

1.14 |

1.20 |

1.06 |

0.83 |

| Na2O |

3.07 |

3.01 |

3.11 |

2.56 |

3.35 |

4.87 |

2.90 |

2.74 |

3.05 |

3.10 |

2.99 |

| K2O |

4.96 |

4.47 |

5.29 |

6.82 |

4.83 |

3.90 |

3.24 |

3.37 |

4.41 |

4.18 |

6.16 |

| P2O5

|

0.11 |

0.11 |

0.28 |

0.23 |

0.24 |

0.58 |

0.35 |

0.35 |

0.39 |

0.25 |

0.22 |

| LOI |

1.04 |

1.16 |

1.38 |

0.56 |

0.78 |

1.42 |

0.72 |

0.94 |

0.58 |

0.90 |

0.78 |

| Total |

99.21 |

95.55 |

103.13 |

102.61 |

102.36 |

102.97 |

100.31 |

101.00 |

100.38 |

99.72 |

100.42 |

Table 2.

(cont.).

| Location |

Ban Lum Isu |

Ban Tha Sanun |

Ban Radar |

Pha Pae |

| Sample No. |

KA-18 |

KA-19 |

KA-20 |

KA-21 |

KA-22 |

KA-23 |

KA-24 |

KA-31 |

KA-32 |

KA-33 |

| SiO2 (wt%) |

74.14 |

71.97 |

77.85 |

74.15 |

68.82 |

69.19 |

68.78 |

77.35 |

69.46 |

76.46 |

| TiO2

|

0.25 |

0.18 |

0.21 |

0.22 |

0.81 |

0.94 |

0.83 |

0.05 |

0.64 |

0.07 |

| Al2O3

|

14.00 |

14.69 |

11.72 |

14.14 |

14.81 |

14.51 |

14.50 |

13.50 |

15.60 |

13.59 |

| Fe2O3(tot)

|

1.68 |

1.03 |

1.54 |

1.54 |

3.33 |

3.71 |

3.36 |

0.70 |

3.65 |

1.51 |

| MnO |

0.08 |

0.05 |

0.06 |

0.06 |

0.11 |

0.12 |

0.11 |

0.04 |

0.10 |

0.11 |

| MgO |

0.54 |

0.30 |

0.48 |

0.52 |

1.07 |

1.28 |

1.09 |

0.02 |

1.14 |

0.11 |

| CaO |

1.09 |

1.62 |

0.70 |

0.71 |

2.49 |

3.04 |

2.56 |

0.20 |

2.60 |

0.21 |

| Na2O |

3.27 |

3.17 |

2.72 |

3.32 |

2.82 |

3.04 |

2.83 |

3.61 |

2.97 |

3.26 |

| K2O |

4.41 |

6.11 |

3.87 |

4.52 |

5.30 |

4.07 |

4.97 |

5.89 |

5.32 |

6.07 |

| P2O5

|

0.25 |

0.35 |

0.44 |

0.41 |

0.51 |

0.57 |

0.52 |

0.01 |

0.23 |

0.01 |

| LOI |

0.56 |

0.98 |

0.86 |

0.96 |

0.40 |

0.38 |

0.42 |

0.48 |

0.98 |

0.90 |

| Total |

100.27 |

100.43 |

100.45 |

100.56 |

100.48 |

100.85 |

99.97 |

101.85 |

102.69 |

102.28 |

Table 2.

(cont.).

| Location |

Mae Chan |

| Sample No. |

A6 |

B6 |

C3 |

MCH25D (D12) |

MCH05A |

MCH13C |

| SiO2 (wt%) |

66.91 |

65.56 |

67.16 |

64.82 |

66.94 |

67.44 |

| TiO2

|

0.66 |

0.65 |

0.90 |

0.59 |

0.66 |

0.63 |

| Al2O3

|

13.60 |

15.32 |

12.27 |

14.42 |

13.61 |

13.86 |

| Fe2O3(tot)

|

3.84 |

3.88 |

6.35 |

4.15 |

3.81 |

4.06 |

| MnO |

0.06 |

0.06 |

0.07 |

0.09 |

0.06 |

0.07 |

| MgO |

2.13 |

2.19 |

3.69 |

2.51 |

2.13 |

2.06 |

| CaO |

2.31 |

2.89 |

1.62 |

3.12 |

2.30 |

2.69 |

| Na2O |

2.26 |

2.72 |

1.77 |

2.18 |

2.28 |

2.46 |

| K2O |

5.64 |

4.75 |

3.13 |

6.09 |

5.66 |

4.08 |

| P2O5

|

0.22 |

0.20 |

0.27 |

0.18 |

0.21 |

0.20 |

| LOI |

2.01 |

1.37 |

2.45 |

1.45 |

1.99 |

2.09 |

| Total |

99.64 |

99.59 |

99.68 |

99.60 |

99.65 |

99.64 |

Table 2.

(cont.).

| Location |

Ban Phu Nam Ron |

Ban Lum Isu |

Ban Radar |

Mae Chan |

| Sample No. |

KA-9 |

KA-10 |

KA-14 |

KA-16 |

KA-24 |

A6 |

B6 |

C3 |

MCH25D (D12) |

| Ba (ppm) |

74.80 |

405.00 |

156.50 |

213.00 |

852.00 |

1325.00 |

1515.00 |

1165.00 |

709.00 |

| Ce |

32.40 |

151.50 |

55.80 |

41.50 |

82.70 |

179.00 |

116.50 |

155.00 |

105.00 |

| Cr |

180.00 |

710.00 |

90.00 |

100.00 |

190.00 |

690.00 |

200.00 |

410.00 |

570.00 |

| Cs |

14.30 |

10.30 |

26.80 |

32.00 |

10.50 |

12.75 |

14.00 |

3.92 |

21.90 |

| Dy |

4.02 |

3.19 |

5.01 |

3.47 |

7.34 |

3.13 |

5.59 |

7.27 |

6.28 |

| Er |

2.09 |

1.50 |

3.09 |

1.99 |

4.08 |

1.58 |

2.91 |

3.86 |

3.48 |

| Eu |

0.22 |

0.86 |

0.46 |

0.50 |

1.34 |

1.51 |

1.52 |

1.27 |

1.63 |

| Ga |

24.10 |

23.10 |

18.40 |

18.30 |

20.30 |

19.90 |

18.60 |

13.50 |

21.30 |

| Gd |

3.20 |

5.62 |

4.57 |

3.40 |

8.24 |

5.22 |

6.93 |

9.30 |

7.64 |

| Hf |

1.70 |

6.40 |

4.90 |

3.30 |

8.30 |

6.80 |

7.60 |

9.20 |

9.80 |

| Ho |

0.75 |

0.54 |

1.03 |

0.68 |

1.46 |

0.60 |

1.09 |

1.41 |

1.24 |

| La |

15.00 |

78.90 |

27.40 |

20.40 |

41.30 |

94.20 |

58.70 |

78.60 |

52.00 |

| Lu |

0.34 |

0.18 |

0.55 |

0.40 |

0.52 |

0.26 |

0.43 |

0.51 |

0.47 |

| Nb |

40.20 |

21.00 |

15.50 |

10.20 |

27.50 |

11.00 |

18.60 |

23.50 |

21.00 |

| Nd |

13.00 |

55.70 |

23.80 |

17.80 |

37.80 |

64.10 |

49.30 |

65.50 |

46.90 |

| Pr |

3.89 |

16.95 |

6.87 |

5.16 |

10.15 |

20.10 |

14.05 |

18.65 |

13.10 |

| Rb |

503.00 |

445.00 |

330.00 |

368.00 |

318.00 |

275.00 |

252.00 |

214.00 |

235.00 |

| Sm |

3.16 |

8.55 |

4.76 |

3.62 |

7.80 |

8.48 |

8.73 |

11.25 |

8.77 |

| Sn |

10.00 |

10.00 |

24.00 |

19.00 |

8.00 |

5.00 |

7.00 |

7.00 |

8.00 |

| Sr |

22.90 |

128.00 |

54.50 |

56.70 |

237.00 |

367.00 |

341.00 |

205.00 |

312.00 |

| Ta |

6.90 |

2.30 |

3.60 |

1.50 |

2.40 |

0.90 |

2.20 |

3.00 |

2.50 |

| Tb |

0.63 |

0.65 |

0.77 |

0.56 |

1.24 |

0.62 |

0.95 |

1.33 |

1.11 |

| Th |

14.50 |

62.60 |

18.95 |

13.75 |

29.00 |

59.70 |

40.10 |

57.10 |

49.90 |

| Tm |

0.35 |

0.21 |

0.55 |

0.37 |

0.60 |

0.23 |

0.45 |

0.57 |

0.51 |

| U |

34.50 |

5.51 |

12.15 |

6.56 |

7.56 |

10.90 |

11.10 |

11.15 |

15.40 |

| V |

<5 |

8.00 |

22.00 |

17.00 |

69.00 |

54.00 |

71.00 |

60.00 |

66.00 |

| W |

8.00 |

3.00 |

2.00 |

4.00 |

1.00 |

3.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| Y |

22.80 |

15.70 |

30.10 |

19.90 |

40.00 |

16.10 |

29.30 |

38.80 |

33.50 |

| Yb |

2.44 |

1.24 |

3.70 |

2.56 |

3.54 |

1.44 |

2.80 |

3.52 |

3.23 |

| Zr |

38.00 |

209.00 |

146.00 |

94.00 |

311.00 |

232.00 |

259.00 |

322.00 |

345.00 |

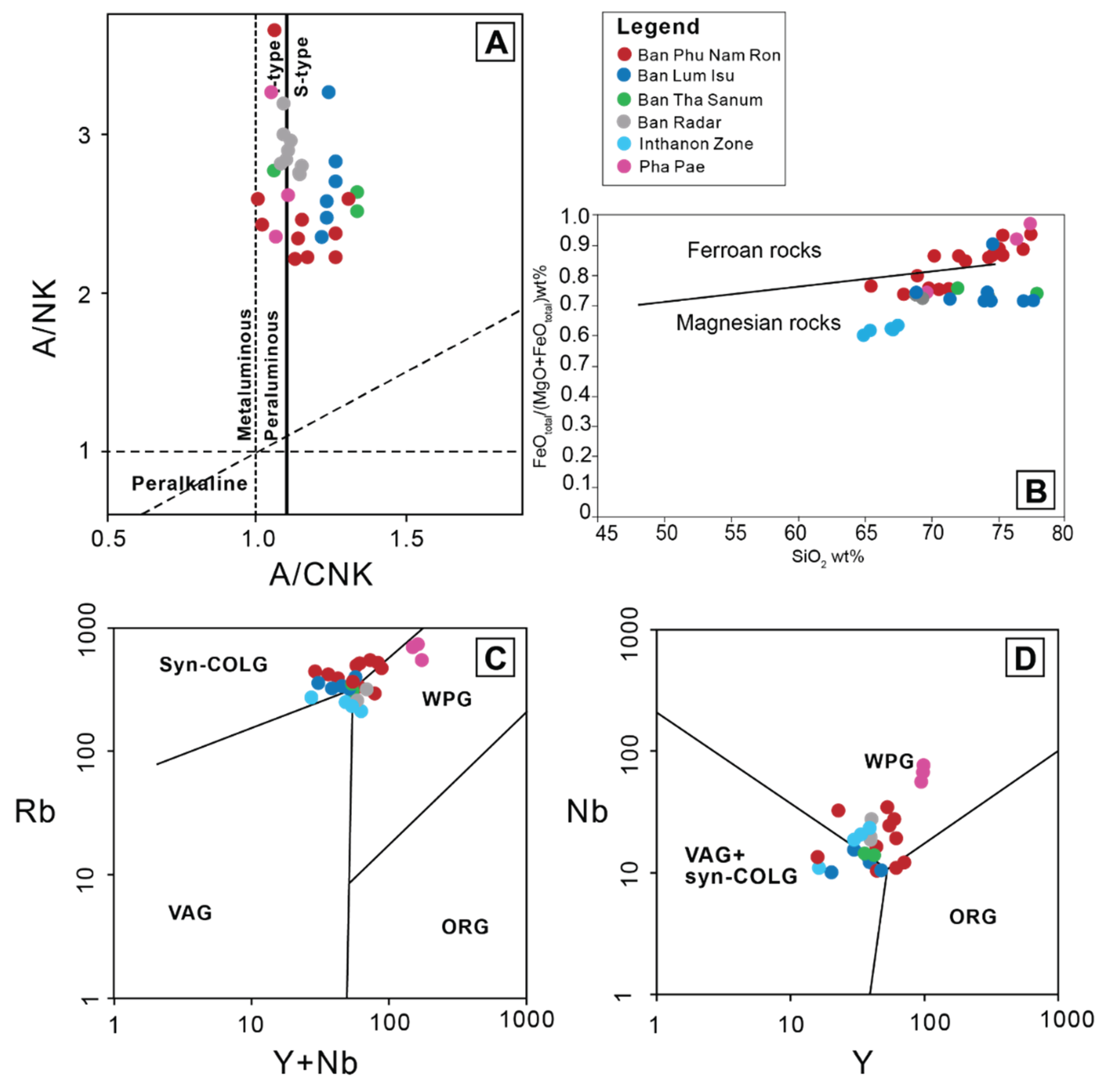

On the A/NK versus A/CNK plot, the samples exhibit A/CNK ratios of 1.0–1.1, defining a peraluminous field (

Figure 6A), which is characteristic of S-type granites derived from sedimentary or metasedimentary crustal sources [

19,

21,

30]. The FeO

total/(Mgo+FeO

total) versus SiO₂ diagram (

Figure 6B) shows that most samples fall within the magnesian field, consistent with reduced ilmenite-series S-type granites derived from crustal melting. However, a few samples plot near or within the ferroan field, suggesting limited Fe enrichment during magmatic differentiation [

35,

36]. This shift likely reflects the effects of fractional crystallization of mafic phases and minor variations in redox conditions during magma evolution [

30,

32]. The overall magnesian affinity supports formation from reduced, sedimentary crustal sources, whereas the ferroan trend in a subset of samples may indicate a transition toward slightly more oxidized or evolved melts under late-stage extensional conditions [

13,

34,

35].

Nb versus Y plots (after [

36]) are used to identify the tectonic setting of granitic magmatism (

Figure 6C, D). Most samples plot within the volcanic arc granite (VAG) and syn-collisional granite (syn-COLG) fields, with a few extending slightly toward the within-plate granite (WPG) field. These patterns indicate that the granitoids were emplaced in a continental arc environment related to subduction processes, with some samples reflecting minor post-collisional magmatic influence. The overall distribution supports the interpretation that the studied rocks represent ilmenite-series, peraluminous S-type granites formed from reduced, crustal-derived magmas in a subduction-related to transitional post-collisional tectonic setting [

19,

21,

30,

31,

32,

33,

36].

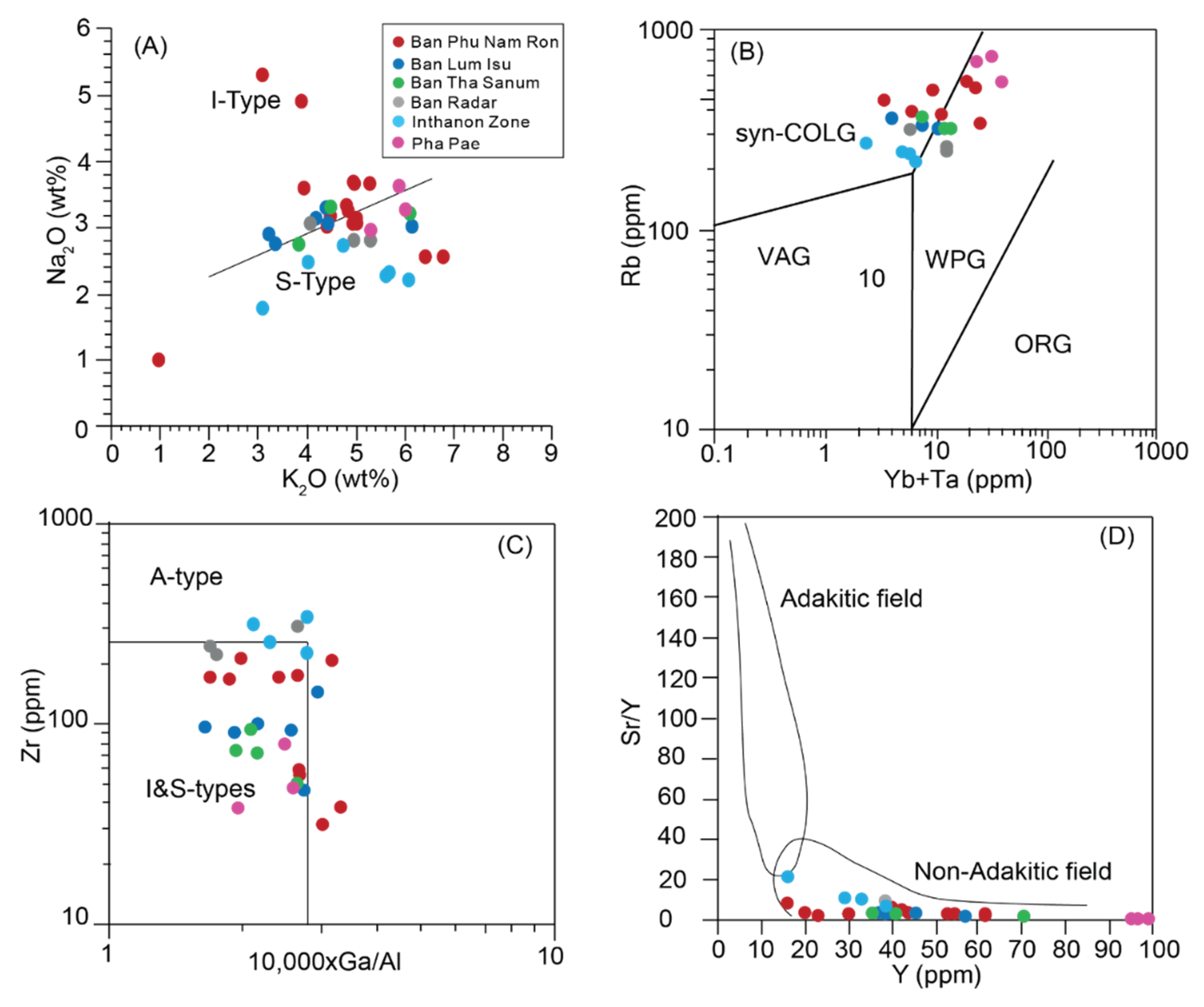

On the Na₂O versus K₂O diagram (

Figure 7A; after [

32], most samples plot within the S-type granite field, with a few overlapping into the I-type domain, indicating a crustal-derived magma source involving partial melting of sedimentary protoliths. The Rb versus (Y + Nb) tectonic discrimination diagram (

Figure 7B; after [

36]) shows that the majority of samples fall within the volcanic arc granite (VAG) and syn-collisional granite (syn-COLG) fields, suggesting that emplacement occurred in a continental arc to post-collisional tectonic environment. In the Zr versus 10,000 × Ga/Al diagram (

Figure 7C; after [

13]) all samples plot in the I- and S-type granite field, confirming their calc-alkaline affinity and lack of A-type (anorogenic) characteristics. Finally, on the Sr/Y versus Y diagram (

Figure 7D; after [

37]), all samples lie in the non-adakitic (calc-alkaline) field, indicating that the magmas did not originate from high-pressure melting of garnet-bearing lower crust but rather from medium- to low-pressure partial melting of crustal material. Altogether, these geochemical features confirm that the studied granitoids are ilmenite-series, peraluminous S-type granites generated in a subduction-related to post-collisional setting through partial melting of reduced, metasedimentary crustal sources.

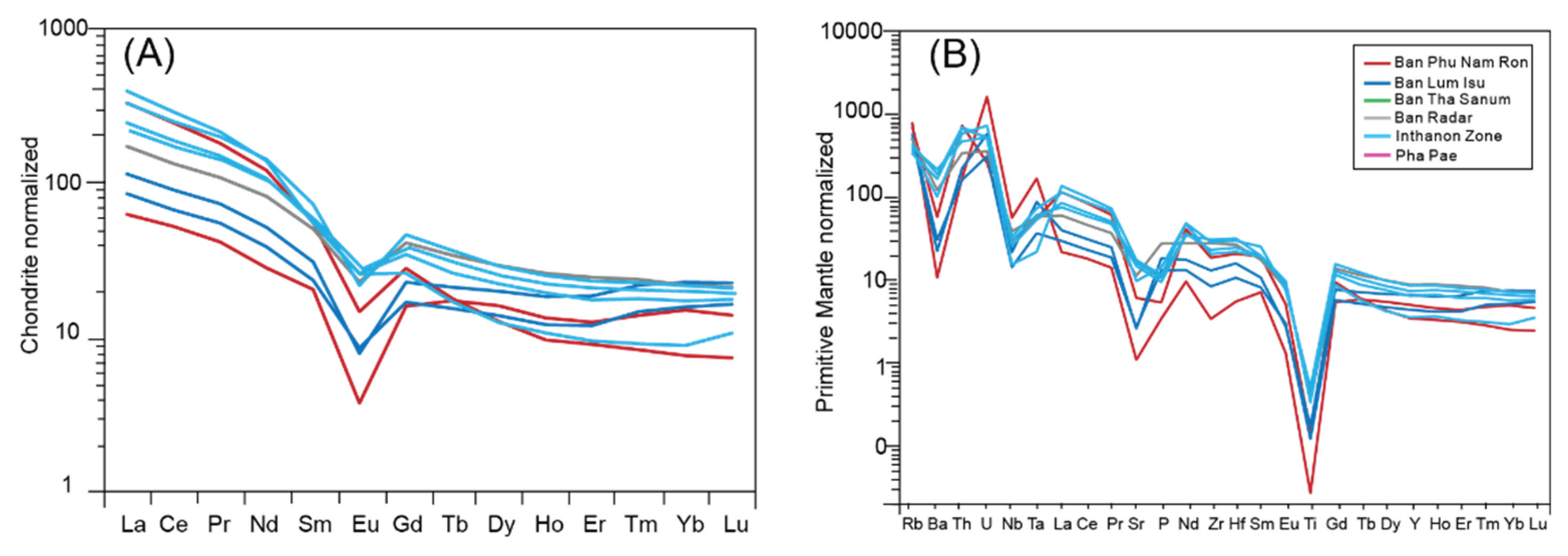

The chondrite-normalized rare-earth element [

20] patterns [

38] (

Figure 8A) show strong light rare-earth element (LREE; La–Sm) enrichment relative to heavy rare-earth elements (HREE; Gd–Lu), producing steep (La/Yb)ₙ ratios. All samples display pronounced negative Eu anomalies (Eu/Eu* < 1), indicating plagioclase fractionation during magmatic evolution or residual plagioclase in the source. These features steep LREE/HREE fractionation, negative Eu anomalies, and peraluminous composition are typical of S-type granitoids derived from partial melting of metasedimentary crustal sources under reduced conditions.

Primitive mantle–normalized trace element patterns [

39] (

Figure 8B) show pronounced enrichment in Rb, Th, and U, along with significant depletion in Ba, Nb, Sr, and Ti, but no notable depletion in P. The overall geochemical pattern, characterized by large-ion lithophile element (LILE) enrichment and negative Nb–Ti anomalies, indicates derivation from a crustal source modified by subduction-related processes. The absence of P depletion suggests limited apatite fractionation during magma evolution. These features collectively point to a syn- to post-collisional tectonic environment, where crustal anatexis occurred under reduced, ilmenite-series conditions.

4.4. Zircon U-Pb Dating

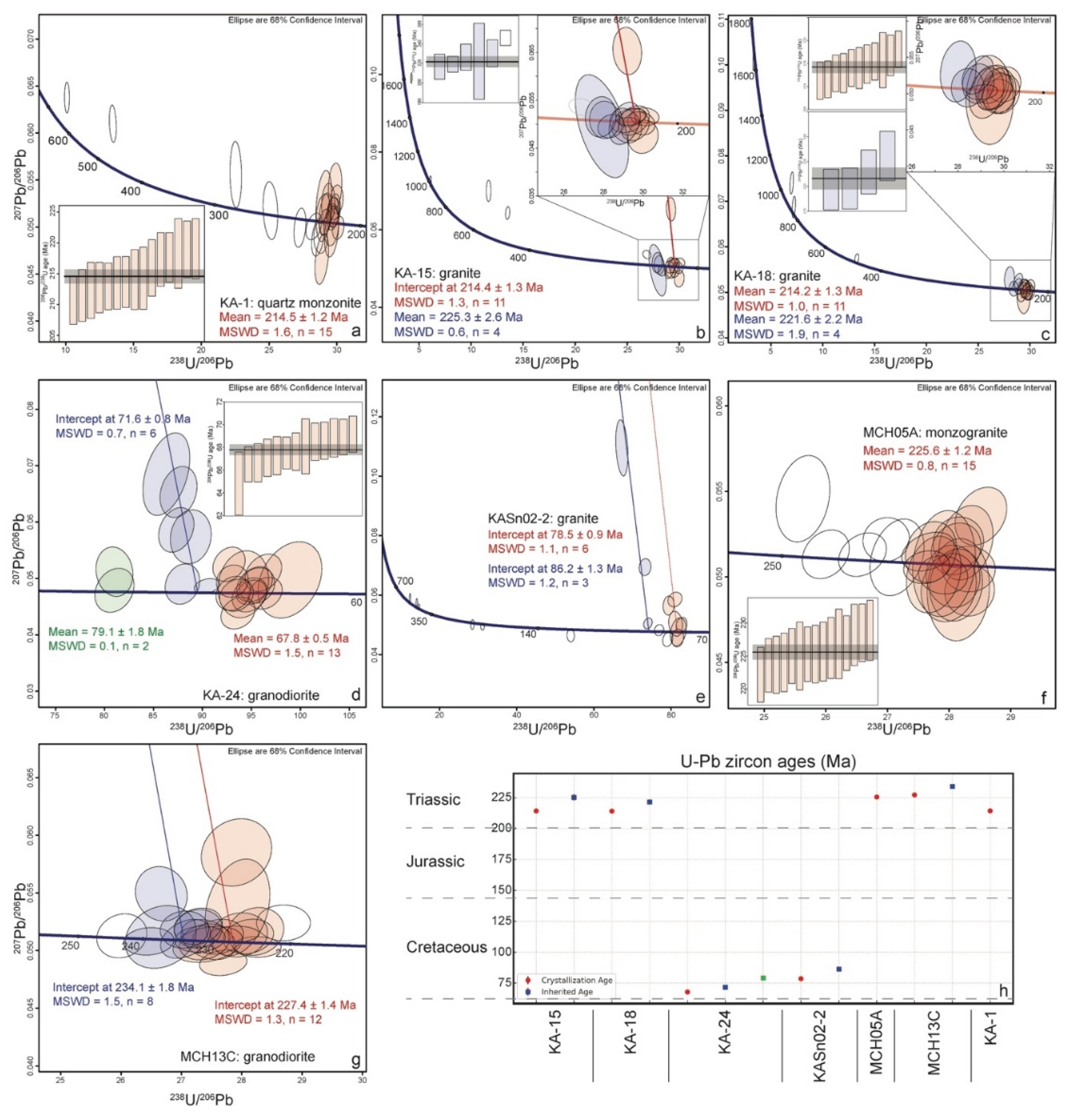

Summary of zircon U-Pb ages from seven granitoids are presented in

Table 3 and

Figure 9A to 9h. Detailed zircon U-Pb geochronological data are provided in Table S1. The analyzed samples from the Western and Northern Thailand resulted in two different ages: 1) Late Triassic (~227-214 Ma), and 2) Late Cretaceous (~79-68 Ma).

4.4.1. Kanchanaburi in Western Thailand (Western Belt Granite)

Five granitic rock samples from Kanchanaburi Province, Western Thailand, were analyzed and classified into two major age groups: the Late Triassic and the Late Cretaceous. The Late Triassic group includes samples KA-1, KA-15, and KA-18, while the Late Cretaceous group comprises samples KA-24 and KASn02-2. U–Pb zircon geochronology reveals that fifteen zircons from quartz monzonite (KA-1) and eleven zircons from granite (KA-18) yielded concordant weighted mean ages of 214.5 ± 1.2 Ma (MSWD = 1.57;

Figure 9A) and 214.2 ± 1.3 Ma (MSWD = 1.02;

Figure 9C), respectively. Similarly, eleven zircons from granite sample KA-15 provided a lower intercept age of 214.4 ± 1.3 Ma (MSWD = 1.33;

Figure 9B). These ages are interpreted as representing the crystallization ages of the respective plutons and are broadly consistent with Late Triassic granitoids within the Western and Central Granite Provinces along the Myanmar–Thailand border[

20,

40,

41]. In addition, both KA-15 and KA-18 yielded additional older weighted mean ages of approximately 225 Ma and 221 Ma, respectively (

Figure 9B and 9c). These may reflect the presence of inherited zircon cores or earlier magmatic pulse within the same tectono-magmatic event. Such age complexity suggests either prolonged magmatic activity or multiple intrusive phases.

In contrast, thirteen zircons from granodiorite sample KA-24 gave a younger weighted mean age of 67.8 ± 0.5 Ma (MSWD = 1.5;

Figure 9D), with additional second and third concordia ages of 71.6 ± 0.8 Ma and 79.1 ± 1.8 Ma, respectively. Similarly, granite sample KASn02-2 yielded a lower intercept age of 78.5 ± 0.9 Ma (MSWD = 1.1; n = 6) and a second intercept age of 86.2 ± 1.3 Ma (MSWD = 1.2;

Figure 9E). These Late Cretaceous ages are interpreted as crystallization ages corresponding to a younger magmatic event. This episode likely correlates with the emplacement of Late Cretaceous granitic bodies in the Western Granite Province, as reported by previous studies (e.g.,[

40,

41,

42,

43]). The presence of multiple concordia ages in these samples may again suggest prolonged or multi-phase emplacement histories during the Late Cretaceous.

4.4.2. Mae Chan in Northern Thailand (Inthanon Zone)

Fifteen zircon grains from MCH05A yielded a weighted mean

206Pb/

238U age of 225.6 ± 1.2 Ma (MSWD = 0.8;

Figure 9F). This age falls within the Middle to Late Triassic period and is interpreted as the timing of crystallization. Additionally, the granodiorite sample (MCH13C) from the same region provided a lower intercept age of 227.4 ± 1.4 Ma, with a second intercept age of 234.1 ± 1.8 Ma (

Figure 9G), further supporting a Late Triassic magmatic episode in Northern Thailand. These Triassic ages are consistent with the timing of granitic magmatism in the Central Granite Province, as previously documented (e.g.,[

40]).

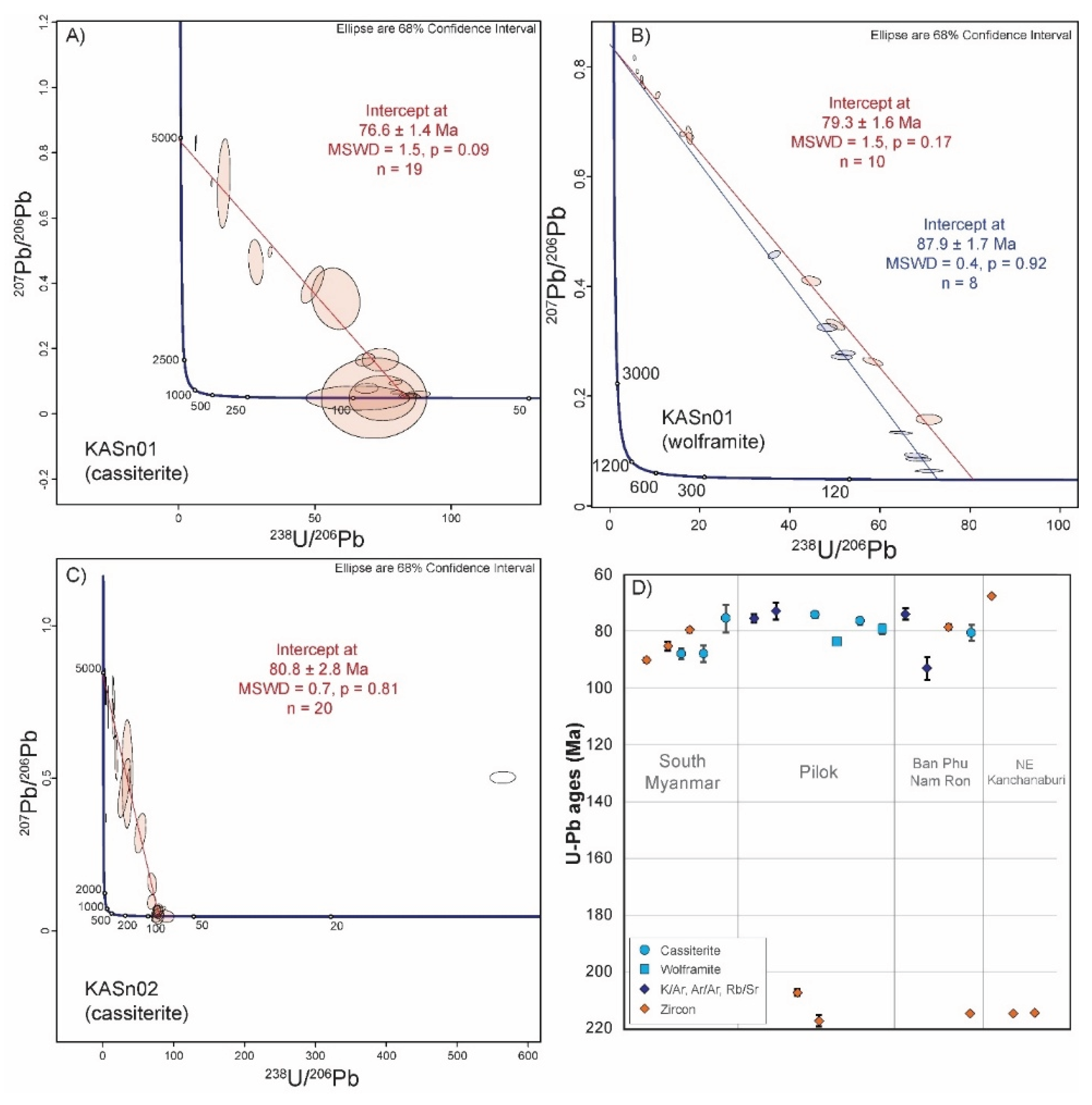

4.5. Cassiterite and Wolframite U-Pb Dating

The U-Pb geochronological data for cassiterite and wolframite separated from the two granitoid samples are presented in

Table 3 and visualized in

Figure 10. Detailed analytical data are compiled in Table S2. The resulting crystallization ages constrain the timing of mineralization to between 75 and 83 Ma (Late Cretaceous), indicating spatially distinct, minor variations in the timing of cassiterite formation between the two localities and timing of cassiterite-wolframite in Pilok.

Nineteen spot analyses performed on cassiterite from sample KASn01 yielded a lower intercept age of 76.6 ± 1.4 Ma (MSWD=1.5;

Figure 10A). In contrast, twenty spots from KASn02 provided a slightly older lower intercept age of 80.8 ± 2.8 Ma (MSWD=0.8;

Figure 10C). Wolframite was detected exclusively in sample KASn01 and resulted in a lower intercept age of 79.3 ± 1.5 Ma, suggesting a xenocrystic or inheritance age of 87.9 ± 1.7 Ma (

Figure 10B). Collectively, these ages indicate that the mineralization event occurred during the Late Cretaceous (approx. 83–75 Ma).

5. Discussion

5.1. Petrogenesis and Magmatic Evolution

The granitoids of Kanchanaburi Province record at least two major magmatic episodes, which collectively reflect the tectonomagmatic evolution of the western Thailand segment of the Sibumasu Block: (1) a province-wide Late Triassic pulse (~215 Ma) associated with the Sibumasu–Indochina collision, and (2) a younger Late Cretaceous event (~68–67 Ma) linked to post-collisional crustal melting and Sn–W mineralization (

Figure 9). For comparison, an earlier Late Triassic magmatic phase (~227–225 Ma) occurred farther north in the Inthanon Zone, representing a separate subduction-related I-type event rather than part of the Kanchanaburi granitoid suite.

5.1.1. Early Late-Triassic (~227–225 Ma) Magmatism (From Northern Thailand)

The oldest granitoids, represented by samples MCH05A and MCH13C in northern Thailand (Mae Chan area), are peraluminous to weakly metaluminous I-type granodiorite–monzogranite containing hornblende + biotite ± magnetite. On tectonic discrimination diagrams (Rb vs. Y+Nb; Nb vs. Nb), the Mae Chan granitoids (MCH05A, MCH13C) plot predominantly within the volcanic-arc to syn-collisional granite (VAG+syn-COLG) fields, although a few samples extend toward the within-plate granite (WPG) field (

Figure 6B–C). This distribution suggests transitional geochemical signatures, possibly reflecting the waning stage of subduction and partial involvement of crustal sources during late-arc to early collisional magmatism., suggesting derivation from mantle-influenced crustal melts related to active continental margin magmatism prior to the collision between Sibumasu and Indochina [

40,

41,

42,

43]. Decreasing P₂O₅ with increasing SiO₂ and moderate magnetic susceptibility values indicate fractionation of apatite from oxidized I-type magmas [

19].

The clustering of ages between ~225–235 Ma across different lithologies and locations suggests regionally extensive Triassic magmatism, possibly related to post-collisional tectonic processes following the Indosinian orogeny. Furthermore, the presence of both weighted mean and intercept ages may imply episodic magma emplacement or the presence of inherited zircon components. This temporal consistency marks the significance of the Triassic as a major magmatic phase in the tectono-magmatic evolution of the Indochina Terrane.

5.1.2. Late Triassic (~215 Ma) Magmatism in Kanchanaburi

Extensive magmatic pulse is recorded across Kanchanaburi by identical zircon U–Pb ages of ~215 Ma from KA-1 (Ban Phu Nam Ron) and KA-15 (Ban Tha Sanun). These granitoids are peraluminous monzogranite to leucogranite, belonging to the S-type to transitional I/S-type series, characterized by biotite ± muscovite ± garnet and accessory zircon. Opaque minerals dominated by ilmenite define a reduced ilmenite-series affinity [

21,

32]. Geochemical indices (A/CNK > 1.1; ASI > 1.0), pronounced negative Eu anomalies, and enrichment in Rb and LREE indicate partial melting of metasedimentary protoliths under syn- to early post-collisional anatexis following the Sibumasu–Indochina collision [

8,

40]. The coeval timing and shared peraluminous, reduced nature of KA-1 and KA-15 granitoids demonstrate a unified Sibumasu-affiliated magmatic domain across the province, contradicting previous models that proposed the Inthanon Suture cutting through central Kanchanaburi [

23].

This suggests a prolonged magmatic episode in this region during the Late Triassic, which appears to be younger than previously reported ages (e.g.,), potentially indicating a revision of the magmatic history in this belt.

5.1.3. Late-Cretaceous (~68–67 Ma) Magmatism

The youngest granitoids, represented by KA-23–KA-24 near Ban Radar and Pilok, yield zircon U–Pb ages of ~68 Ma. They are highly evolved, reduced S-type leucogranites associated with pegmatitic and greisen veins hosting Sn–W–Li mineralization [

8,

23]. The rocks exhibit strong negative Eu anomalies, high Rb/Sr and Nb/Ta ratios, and steep REE fractionation patterns. Elevated Ga/Al values and enrichment in F, Li, Nb, and Ta reflect advanced fractional crystallization and fluid evolution under reduced, low-Ti conditions [

13,

33]. These features resemble Late Cretaceous rare-metal granites along the Southeast Asian Tin Belt in southern Thailand and Myanmar, marking a renewed period of crustal melting during post-collisional extension.

5.2. Timing of Sn-W Mineralization

Cassiterite and wolframite are the principal ore minerals in tin and tungsten deposits, and U–Pb geochronology has recently become a widely accepted method for constraining the timing of Sn–W mineralization (e.g.,[

10,

40]).

40Ar/

39Ar ages were reported at Pilok Mine suggesting Sn and W mineralization occurred during the Late Cretaceous. Our U-Pb ages of cassiterite and wolframite in the Pha Pae Mine near Pilok (

Figure 1) are 76.6 ± 1.4 Ma and 79.3 ± 1.6 Ma respectively suggesting that the Sn mineralization formed slightly after the W mineralization consistent to cassiterite (74.3 ± 1.1 Ma) and wolframite (83.8 ± 1.0 Ma) U-Pb ages previously dated from ore-bearing granite at the Pilok Mine [

43]. Additionally, another cassiterite U-Pb age of 80.8 ± 2.8 Ma was obtained from Jarin Mine further southeast of the Pilok Mine (

Figure 1). More efforts to acquire and constrain the Sn-W mineralization ages in the SE Asia Tin Belt using cassiterite-wolframite U-Pb geochronology have been done in the adjacent area, such as Southern Myanmar indicating similar (~75 Ma) and slightly older cassiterite ages (~88 Ma).

It is worth noting that granitic rocks at Pilok and Pha Pae area formed much earlier (215-207 Ma [

40,

41] than the Sn-W mineralization events (85-74 Ma) (

Figure 10D) while the U-Pb data from Jarin Mine indicate coeval rock and ore-forming events (

Figure 10D) suggesting that in Kanchanaburi the Sn-W mineralization events occurred during the Late Cretaceous. Further study on geochronology and metallogeny is required to clarify relationship between the granitic rocks and the Sn-W mineralization.

5.3. Tectomomagmatic Implications

The temporal and geochemical evolution from I-type arc-related granites (ca. 227 Ma) to peraluminous S-type syn-collisional granites (ca. 215 Ma), and finally to rare-metal granites (ca. 68 Ma), reflects a progressive transition from subduction-related to crustal anatectic and extensional magmatism within the Sibumasu Block [

1,

8,

23]. This evolution aligns with regional tectonic reconstructions that interpret the Late Triassic Sibumasu–Indochina amalgamation, followed by Late Cretaceous lithospheric thinning and reactivation of crustal melts [

40,

48,

49]. Collectively, the integrated age and geochemical evidence indicate that Kanchanaburi granitoids belong entirely to the western Sibumasu magmatic domain, and the proposed Inthanon Suture likely lies farther east than previously illustrated by [

1] (

Figure 11).

6. Conclusions

The granitoid suites of Kanchanaburi Province reveal a complex and prolonged magmatic history that records the tectonomagmatic evolution of western Thailand within the Sibumasu Terrane. Integrated zircon U–Pb geochronology, petrography, and geochemical data define at least two major intrusive episodes Late Triassic (~215 Ma) and Late Cretaceous (~68 Ma) that correspond to distinct tectonic regimes along the Southeast Asian Tin Belt.

1. The Late Triassic granitoids (KA-1, KA-15) represent syn- to early post-collisional S-type magmatism generated through partial melting of metasedimentary crust following the Sibumasu–Indochina collision. Their peraluminous, reduced, ilmenite-series affinity (A/CNK > 1.1; ASI > 1.0), strong negative Eu anomalies, and enrichment in Rb and LREE indicate crustal anatexis under low-fO₂ conditions. These granitoids form a coherent Sibumasu-affiliated magmatic province across Kanchanaburi, refuting earlier models that place the Inthanon Suture through central Thailand.

2. The Late Cretaceous granitoids (KA-23–KA-24) mark a renewed post-collisional extensional magmatism characterized by highly evolved, reduced S-type leucogranites and associated pegmatitic and greisen veins bearing Sn–W–Li mineralization. Their elevated Ga/Al, Rb/Sr, and Nb/Ta ratios, coupled with pronounced negative Eu anomalies, indicate advanced fractional crystallization and fluid-rich evolution consistent with rare-metal granite systems elsewhere in the Southeast Asian Tin Belt.

3. In contrast, earlier Triassic I-type granodiorite–monzogranite magmatism (~227–225 Ma) in northern Thailand reflects a preceding subduction-related episode prior to the main Sibumasu–Indochina collision, marking the transition from active continental margin to collisional regimes.

Overall, the magmatic evolution from Early Triassic I-type to Late Triassic S-type and Late Cretaceous rare-metal granites documents a shift from subduction-related to crustal-derived and extensional magmatism within the Sibumasu Block. This progressive evolution supports a tectonic model in which the Sibumasu–Indochina amalgamation was followed by Late Cretaceous lithospheric thinning and crustal re-melting, producing mineralized granitic systems characteristic of the Southeast Asian Tin Belt. Consequently, all granitoid bodies in Kanchanaburi are interpreted to belong to the western Sibumasu magmatic domain, implying that the Inthanon Suture Zone lies farther east than previously proposed.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

The authors acknowledge the use of generative artificial intelligence tools in the preparation of this manuscript. Specifically, ChatGPT (OpenAI) was employed to assist with language editing and paraphrasing. All content generated by the AI was reviewed and verified by the authors to ensure accuracy and compliance with ethical standards. The authors accept full responsibility for the integrity and originality of the content presented.

Author Contributions

Patchawee Nualkhao: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Supervision; Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing – Original Draft; Project Administration; Funding Acquisition. Ekkachak Chandon: Investigation; Resources; Writing – Review & Editing. Peerapong Sritangsirikul: Resources; Writing – Original Draft. Khin Zaw: Validation; Writing – Review & Editing. Dylan Sonnemans: Writing – Review & Editing; Funding Acquisition. Punya Charusiri: Writing – Review & Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Processed geochemical, petrographic, and mineralogical datasets supporting the findings of this study are included within the article and its Supplementary Materials. The raw analytical files (including full-resolution thin-section images, XRF/ICP-MS instrument outputs, and zircon U–Pb laser ablation data) are not publicly available due to institutional data management policies and laboratory confidentiality agreements. However, these data may be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express sincere gratitude to Mahidol University Kanchanaburi Campus for providing laboratory facilities throughout this research. This study was funded by Thailand Government and SE Asia project, CODES, University of Tasmania, Australia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Uchida, E.; Yokokura, T.; Niki, S.; Hirata, T. Geochemical Characteristics and U–Pb Dating of Granites in the Western Granitoid Belt of Thailand. Geosciences 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Fanka, A.; Kasiban, C.; Tsunogae, T.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Sutthirat, C. Petrochemistry and Zircon U-Pb Geochronology of Felsic Xenoliths in Late Cenozoic Gem-Related Basalt from Bo Phloi Gem Field, Kanchanaburi, Western Thailand. Journal of Earth Science 2021, 32, 1035-1052. [CrossRef]

- Buranrom, S.; Tangwattananukul, L.; Rattanaphra, D.; Kingkam, W.; Nuchdang, S. Petrochemistry of Bang Tha Cham granitoid, Chonburi Province, Central Granite Belt, Thailand. ScienceAsia 2024, 50. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, X.; Cawood, P.A.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xing, X.; Senebouttalath, V.; Gan, C. Prototethyan Accretionary Orogenesis Along the East Gondwana Periphery. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Singtuen, V.; Phajuy, B.; Wichaiya, K. Geochemical characteristics of arc fractionated I-type granitoids of eastern Tak Batholith, Thailand. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sritangsirikul, P.; Meffre, S.; Zaw, K.; Belousov, I.; Lai, Y.J.; Richards, A.; Charusiri, P. Using compositions of zircon to reveal fertile magmas for the formation of porphyry deposits in the Loei and Truong Son fold belts, northern Laos. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2024, 272. [CrossRef]

- Fanka, A.; Tadthai, J. Petrology and geochemistry of Li-bearing pegmatites and related granitic rocks in southern Thailand. Frontiers in Earth Science 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Cobbing, E.J.; Mallick, D.I.J.; Pitfield, P.E.J.; Teoh, L.H. The granites of the Southeast Asian tin belt. Journal of the Geological Society 1986, 143, 537-550. [CrossRef]

- Linnen, R. Depth of emplacement, fluid provenance and metallogeny in granitic terranes. Mineralium Deposita 1998, 33, 461-476. [CrossRef]

- Oo, Z.M.; Zaw, K.; Belousov, I.; Putthapiban, P.; Makoundi, C. Tectonic and metallogenic implications of W-Sn related granitoid rocks in the Kawthaung-Bankachon area. Geosystems and Geoenvironment 2023, 2. [CrossRef]

- Phyo, A.P.; Li, H.; Hu, X.J.; Ghaderi, M.; Myint, A.Z.; Faisal, M. Geology, geochemistry, and zircon U-Pb geochronology of the Nanthila and Pedet granites. Ore Geology Reviews 2025, 178. [CrossRef]

- Appleby, S.K.; Gillespie, M.R.; Graham, C.M.; Hinton, R.W.; Oliver, G.J.; Kelly, N.M. Do S-type granites commonly sample infracrustal sources? Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 2010, 160, 115-132. [CrossRef]

- Whalen, J.B.; Chappell, B.W. Opaque mineralogy and mafic mineral chemistry of I-and S-type granites of the Lachlan fold belt, southeast Australia. American Mineralogist 1988, 73, 281-296.

- Todd, V.; Shaw, S. S-type granitoids and an IS line in the Peninsular Ranges batholith, southern California. Geology 1985, 13, 231-233. [CrossRef]

- Kirwin, D.J. Geological Belts, Plate Boundaries, and Mineral Deposits in Myanmar; 2018.

- Xu, B.; Hou, Z.Q.; Griffin, W.L.; Yu, J.X.; Long, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, T.; Fu, B.; Belousova, E.; O’Reilly, S.Y. Apatite halogens and Sr-O and zircon Hf-O isotopes: Recycled volatiles in Jurassic porphyry ore systems in southern Tibet. Chemical Geology 2022, 605. [CrossRef]

- Cherniak, D. Diffusion in accessory minerals: zircon, titanite, apatite, monazite and xenotime. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 2010, 72, 827-869. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.L.; Lee, T.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Iizuka, Y.; Quek, L.X.; Charusiri, P. Zircon U-Pb geochronology of the Lan Sang gneisses and its tectonic implications for the Mae Ping shear zone, NW Thailand. Frontiers in Earth Science 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, S. The magnetite-series and ilmenite-series granitic rocks. Mining Geology 1977, 27, 293-305. [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, N.; Searle, M.; Morley, C.; Whitehouse, M.; Spencer, C.; Robb, L. The closure of Palaeo-Tethys in Eastern Myanmar and Northern Thailand: new insights from zircon U–Pb and Hf isotope data. Gondwana Research 2016, 39, 401-422. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, S. The granitoid series and mineralization; 1981.

- Searle, M.; Whitehouse, M.; Robb, L.; Ghani, A.; Hutchison, C.; Sone, M.; Ng, S.P.; Roselee, M.; Chung, S.L.; Oliver, G. Tectonic evolution of the Sibumasu–Indochina terrane collision zone in Thailand and Malaysia. Journal of the Geological Society 2012, 169, 489-500. [CrossRef]

- Zaw, K.; Meffre, S.; Lai, C.K.; Burrett, C.; Santosh, M.; Graham, I.; Manaka, T.; Salam, A.; Kamvong, T.; Cromie, P. Tectonics and metallogeny of mainland Southeast Asia—A review and contribution. Gondwana Research 2014, 26, 5-30. [CrossRef]

- Department of Mineral, R. Geological map of Thailand scale 1:250,000. 2007.

- Department of Mineral, R. Mineral resources map of Thailand. 2007.

- Thompson, J.M.; Meffre, S.; Danyushevsky, L. Impact of air, laser pulse width and fluence on U–Pb dating of zircons by LA-ICPMS. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry 2018, 33, 221-230. [CrossRef]

- Htun, K.T.; Zaw, K.; Belousov, I.; Yonezu, K.; Makoundi, C.; Watanabe, K.; Goemann, K. U-Pb zircon and cassiterite geochronology of Sn-W bearing granitoids at the Tagu mining area in the Myeik region, Southern Myanmar: Insight into ore genesis and metallogenic implication. Geosystems and Geoenvironment 2025. [CrossRef]

- Vermeesch, P. (anchored) isochrons in IsoplotR. Geochronology Discussions 2024, 6, 397-416. [CrossRef]

- Streckeisen, A. To each plutonic rock its proper name. Earth-Science Reviews 1976, 12, 1-33. [CrossRef]

- Frost, B.R.; Barnes, C.G.; Collins, W.J.; Arculus, R.J.; Ellis, D.J.; Frost, C.D. A geochemical classification for granitic rocks. Journal of Petrology 2001, 42, 2033-2048. [CrossRef]

- Maniar, P.D.; Piccoli, P.M. Tectonic discrimination of granitoids. Geological Society of America Bulletin 1989, 101, 635-643. [CrossRef]

- Chappell, B.W.; White, A.J.R. Two contrasting granite types. Pacific Geology 1974, 8, 173-174.

- Peccerillo, A.; Taylor, S.R. Geochemistry of Eocene calc-alkaline volcanic rocks from the Kastamonu area, northern Turkey. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1976, 58, 63-81. [CrossRef]

- Collins, W.J.; Beams, S.D.; White, A.; Chappell, B. Nature and origin of A-type granites with particular reference to southeastern Australia. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 1982, 80, 189-200. [CrossRef]

- Eby, G.N. Chemical subdivision of the A-type granitoids: petrogenetic and tectonic implications. Geology 1992, 20, 641-644. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A.; Harris, N.B.; Tindle, A.G. Trace element discrimination diagrams for the tectonic interpretation of granitic rocks. Journal of Petrology 1984, 25, 956-983. [CrossRef]

- Defant, M.J.; Drummond, M.S. Derivation of some modern arc magmas by melting of young subducted lithosphere. Nature 1990, 347, 662-666. [CrossRef]

- Boynton, W.V. Cosmochemistry of the rare earth elements: meteorite studies. In Rare Earth Element Geochemistry, Henderson, P., Ed.; Elsevier: 1984.

- Sun, S.S.; McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: implications for mantle composition and processes. In Magmatism in the Ocean Basins, Saunders, A.D.E.D.N.M.J., Ed.; 1989; Volume 42.

- Jiang, H.; Zhao, K.; Jiang, S.; Li, W.; Zaw, K.; Zhang, D. Late Triassic post-collisional high-K two-mica granites in Peninsular Thailand, SE Asia: Petrogenesis and Sn mineralization potential. 2023.

- Liu, L.; Hu, R.-Z.; Fu, Y.-Z.; Yang, J.-H.; Zhou, M.-F.; Mao, W.; Tang, Y.-W.; Fanka, A.; Li, Z. Cassiterite and zircon U–Pb ages and compositions from ore-bearing and barren granites in Thailand: Constraints on the formation of tin deposits in Southeast Asia. Ore Geology Reviews 2024, 174, 106282. [CrossRef]

- Putthapiban, P.; Gray, C. Age and tin-tungsten mineralization of the Phuket granites, Thailand. Geology and Mineral Resources of Thailand 1983, 19-28.

- Charusiri, P.; Clark, A.; Farrar, E.; Archibald, D.; Charusiri, B. Granite belts in Thailand: evidence from the 40Ar/39Ar geochronological and geological syntheses. Journal of Southeast Asian Earth Sciences 1993, 8, 127-136. [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Zhong, H.; Yang, J.; Tang, Y.; Liu, L.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sein, K.; Aung, S.M.; Li, J.; et al. Combined zircon, molybdenite, and cassiterite geochronology and cassiterite geochemistry of the Kuntabin tin-tungsten deposit in Myanmar. Economic Geology 2020, 115, 603-625.

- Charusiri, P. Lithophile Metallogenic Epochs of Thailand, A Geological and Geochronological Investigation.

- Ph.D. Thesis. Queen’s University, 1989.

- Beckinsale, R.D.; Suensilpong, S.; Nakapadungrat, S.; Walsh, J.N. Geochronology and geochemistry of granite magmatism in Thailand in relation to a plate tectonic model. Journal of the Geological Society 1979, 136, 529-537.

- Burton, C.K.; Bignell, J.D. Cretaceous-tertiary events in Southeast Asia. Geological Society of America Bulletin 1969, 80, 681-688.

- Schwartz, M.; Rajah, S.; Askury, A.; Putthapiban, P.; Djaswadi, S. The southeast Asian tin belt. Earth-Science Reviews 1995, 38, 95-293. [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, N.J.; Hawkesworth, C.J.; Robb, L.J.; Whitehouse, M.J.; Roberts, N.M.; Kirkland, C.L.; Evans, N.J. Contrasting granite metallogeny through the zircon record: A case study from Myanmar. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 748-748. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Geologic map of the study area with mining and sample locations. Geological map modified from Geological map of mineral resources in Kanchanaburi Province and Mineral Resources Map Kanchanaburi [

24,

25].

Figure 1.

Geologic map of the study area with mining and sample locations. Geological map modified from Geological map of mineral resources in Kanchanaburi Province and Mineral Resources Map Kanchanaburi [

24,

25].

Figure 2.

Photographs (left) and photomicrographs (right) taken using a polarizing microscope under crossed-polars showing representative granite samples: (A) KA-9, (B) KA-10, (C) KA-3 from Ban Phu Nam Ron granite body, (D) KA-21 from the Ban Tha Sanun granite body, (E) KA-16 from Ban Lum Isu granite body, (F) KA-21 from Ban Radar granite body, (G) MCH13C, and (H) MCH05A from Mae Chan granite body. Abbreviations: Qz, quartz; Pl, plagioclase; Kfs, K-feldspar (microcline/orthoclase); Bt, biotite; Ms, muscovite; Hbl, hornblende; Cpx, clinopyroxene; Mag, magnetite; Ilm, ilmenite; Ttn, titanite (sphene); Apt, apatite; Zr, zircon; Tmr, tourmaline.

Figure 2.

Photographs (left) and photomicrographs (right) taken using a polarizing microscope under crossed-polars showing representative granite samples: (A) KA-9, (B) KA-10, (C) KA-3 from Ban Phu Nam Ron granite body, (D) KA-21 from the Ban Tha Sanun granite body, (E) KA-16 from Ban Lum Isu granite body, (F) KA-21 from Ban Radar granite body, (G) MCH13C, and (H) MCH05A from Mae Chan granite body. Abbreviations: Qz, quartz; Pl, plagioclase; Kfs, K-feldspar (microcline/orthoclase); Bt, biotite; Ms, muscovite; Hbl, hornblende; Cpx, clinopyroxene; Mag, magnetite; Ilm, ilmenite; Ttn, titanite (sphene); Apt, apatite; Zr, zircon; Tmr, tourmaline.

Figure 3.

Q–A–P (Quartz–Alkali feldspar–Plagioclase) ternary diagram for classification of the studied granitoid samples (after [

29]).

Figure 3.

Q–A–P (Quartz–Alkali feldspar–Plagioclase) ternary diagram for classification of the studied granitoid samples (after [

29]).

Figure 4.

Magnetic susceptibilities at the granite sample locations.

Figure 4.

Magnetic susceptibilities at the granite sample locations.

Figure 5.

(A) Harker variation diagrams showing major element oxides (SiO₂ vs. Al₂O₃, Fe₂O₃t, MgO, CaO, Na₂O, K₂O, TiO₂, and P₂O₅), (B) Na

2O+K

2O vs. SiO

2 (TAS), (C) K₂O versus SiO₂ diagram (after [

33] for the studied granitoid samples.

Figure 5.

(A) Harker variation diagrams showing major element oxides (SiO₂ vs. Al₂O₃, Fe₂O₃t, MgO, CaO, Na₂O, K₂O, TiO₂, and P₂O₅), (B) Na

2O+K

2O vs. SiO

2 (TAS), (C) K₂O versus SiO₂ diagram (after [

33] for the studied granitoid samples.

Figure 6.

(A) Diagram of Al2O3/(Na2O+K2O) vs. Al2O3/(CaO+Na2O+K2O) showing the classification of the studied samples as metaluminous and peraluminous, as well as I- and S-types (x, x), (B) SiO2-FeOtotal-MgO diagram, (C) and (D) Tectonic setting discrimination diagram (x) for the studied granite samples. Abbreviations: Syn-COLG, syn-collision granite; VAG, volcanic arc granite; WPG, within-plate granite; ORG, ocean ridge granite.

Figure 6.

(A) Diagram of Al2O3/(Na2O+K2O) vs. Al2O3/(CaO+Na2O+K2O) showing the classification of the studied samples as metaluminous and peraluminous, as well as I- and S-types (x, x), (B) SiO2-FeOtotal-MgO diagram, (C) and (D) Tectonic setting discrimination diagram (x) for the studied granite samples. Abbreviations: Syn-COLG, syn-collision granite; VAG, volcanic arc granite; WPG, within-plate granite; ORG, ocean ridge granite.

Figure 7.

(A) Diagram of Na

2O vs. K

2O showing the classification of the studied granite samples as I- and S-types [

32], (B) Tectonic setting discrimination diagram for the studied granite samples [

36]. Abbreviations: syn-COLG, syn-collision granite; VAG, volcanic arc granite; WPG, within-plate, (C) Zr vs. 10,000 × Ga/Al diagram showing the classification of the studied samples as I&S- and A-types [

13] and (D) Sr/Y vs. Y diagram showing their classification as adakitic and non-adakitic rocks (calc-alkaline rocks) [

37].

Figure 7.

(A) Diagram of Na

2O vs. K

2O showing the classification of the studied granite samples as I- and S-types [

32], (B) Tectonic setting discrimination diagram for the studied granite samples [

36]. Abbreviations: syn-COLG, syn-collision granite; VAG, volcanic arc granite; WPG, within-plate, (C) Zr vs. 10,000 × Ga/Al diagram showing the classification of the studied samples as I&S- and A-types [

13] and (D) Sr/Y vs. Y diagram showing their classification as adakitic and non-adakitic rocks (calc-alkaline rocks) [

37].

Figure 8.

Chondrite normalized and primitive mantle normalized rare-earth element patterns for the studied samples [

39].

Figure 8.

Chondrite normalized and primitive mantle normalized rare-earth element patterns for the studied samples [

39].

Figure 9.

Concordia diagrams of U-Pb zircon ages from different locations (a), (b), (e) from Ban Phu Nam Ron, (c) from Ban Lum Isu, (d) from Ban Radar in Kanchanaburi and (f)-(g) from Mae Chan and (h) summary of zircon crystallization and inheritance ages.

Figure 9.

Concordia diagrams of U-Pb zircon ages from different locations (a), (b), (e) from Ban Phu Nam Ron, (c) from Ban Lum Isu, (d) from Ban Radar in Kanchanaburi and (f)-(g) from Mae Chan and (h) summary of zircon crystallization and inheritance ages.

Figure 10.

Cassiterite and wolframite U-Pb ages from granite in Kanchanaburi (A)-(B) KASn01 from Pha Pae Mine, and (C) KaSn02 from Ban Phu Nam Ron. (D) U-Pb ages comparison between South Myanmar [

10,

44] and Kanchaburi Province (this study, [

42,

43,

45,

46,

47]).

Figure 10.

Cassiterite and wolframite U-Pb ages from granite in Kanchanaburi (A)-(B) KASn01 from Pha Pae Mine, and (C) KaSn02 from Ban Phu Nam Ron. (D) U-Pb ages comparison between South Myanmar [

10,

44] and Kanchaburi Province (this study, [

42,

43,

45,

46,

47]).

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram showing the tectonic evolution and granite formation between the Western Granite Belt on Shibumasu Terrane and Inthanon Zone. Modified after [

1,

6,

10,

41].

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram showing the tectonic evolution and granite formation between the Western Granite Belt on Shibumasu Terrane and Inthanon Zone. Modified after [

1,

6,

10,

41].

Table 1.

Modal composition of the analyzed granite samples.

Table 1.

Modal composition of the analyzed granite samples.

| Granite Body |

Sample No. |

Rock Type |

Magnetic

susceptibility

x10-3(SI) |

Qz |

Plg |

Kfs |

Bt |

Hbl |

Zr |

Apt |

Ms |

Ttn |

Cpx |

Mt |

Ilm |

Gar |

| Ban Phu Nam Ron |

KA-1 |

Quartz monzonite |

0.0008 |

64.5 |

16.6 |

6.9 |

10.0 |

- |

1.0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.4 |

0.7 |

- |

| KA-2 |

Quartz monzonite |

0.0012 |

68.0 |

14.2 |

6.5 |

9.0 |

- |

0.8 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.0 |

0.6 |

- |

| KA-3 |

Granite |

0.0011 |

67.7 |

12.8 |

7.0 |

9.4 |

- |

0.8 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.8 |

0.6 |

- |

| KA-4 |

Granite |

0.0005 |

74.0 |

14.4 |

6.3 |

5.5 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| KA-5 |

Granite |

0.0011 |

72.6 |

15.3 |

7.8 |

4.1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.3 |

- |

- |

| KA-6 |

Granite |

0.0006 |

72.9 |

15.1 |

5.8 |

6.3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| KA-7 |

Granite |

0.0005 |

73.4 |

11.5 |

8.2 |

5.1 |

- |

- |

- |

1.1 |

- |

- |

0.3 |

0.6 |

- |

| KA-8 |

Granite |

0.0001 |

67.9 |

22.1 |

5.5 |

0.4 |

- |

- |

- |

3.5 |

- |

- |

- |

0.8 |

- |

| KA-9 |

Granite |

0.0004 |

75.1 |

13.5 |

8.7 |

1.9 |

- |

- |

- |

0.6 |

- |

- |

0.1 |

0.2 |

- |

| KA-10 |

Granite |

0.0022 |

63.3 |

8.6 |

17.0 |

4.3 |

- |

0.4 |

- |

3.6 |

- |

2.1 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

- |

| KA-11 |

Granite |

0.0011 |

56.2 |

8.2 |

18.4 |

8.7 |

- |

0.2 |

- |

4.3 |

- |

2.1 |

1.5 |

0.6 |

- |

| KA-12 |

Granite |

0.0009 |

53.9 |

13.5 |

16.0 |

9.9 |

- |

0.3 |

- |

3.0 |

- |

2.3 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

0.2 |

| Ban Lum Isu |

KA-13 |

Granite |

0.0007 |

64.3 |

14.2 |

2.5 |

11.4 |

- |

1.0 |

- |

3.7 |

- |

- |

2.6 |

0.3 |

- |

| KA-14 |

Granite |

0.0004 |

63.9 |

18.1 |

7.0 |

7.8 |

- |

0.6 |

- |

2.5 |

- |

- |

0.1 |

0.2 |

- |

| KA-15 |

Granite |

0.0009 |

47.1 |

15.3 |

8.9 |

19.2 |

- |

2.2 |

- |

6.0 |

- |

- |

1.3 |

0.2 |

- |

| KA-16 |

Granite |

0.0002 |

54.3 |

21.6 |

2.2 |

11.2 |

- |

1.6 |

- |

6.3 |

- |

- |

1.2 |

1.8 |

- |

| KA-17 |

Granite |

0.0004 |

54.0 |

30.4 |

1.6 |

10.4 |

- |

0.8 |

- |

2.3 |

- |

- |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

| KA-18 |

Granite |

0.0002 |

46.3 |

19.8 |

6.5 |

17.2 |

- |

2.3 |

0.3 |

5.3 |

- |

- |

1.7 |

0.8 |

- |

| Ban Tha Sanun |

KA-19 |

Granite |

0.0014 |

59.7 |

10.4 |

15.2 |

5.1 |

- |

0.1 |

- |

7.1 |

- |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

| KA-20 |

Granite |

0.0005 |

44.0 |

22.1 |

19.9 |

8.1 |

- |

- |

- |

3.8 |

- |

1.7 |

0.5 |

|

0.2 |

| KA-21 |

Granite |

0.0006 |

69.8 |

11.2 |

6.2 |

8.1 |

- |

- |

- |

3.0 |

- |

0.5 |

1.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

| Ban Radar |

KA-22 |

Quartz monzonite |

0.0177 |

56.6 |

23.5 |

3.7 |

13.4 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

- |

- |

0.6 |

- |

1.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

| KA-23 |

Granodiorite |

0.0189 |

55.9 |

25.6 |

5.2 |

8.9 |

- |

0.6 |

0.3 |

- |

0.6 |

- |

1.9 |

- |

1.3 |

| KA-24 |

Granodiorite |

0.0199 |

58.6 |

24.8 |

6.5 |

7.4 |

- |

0.4 |

- |

- |

0.3 |

- |

2.2 |

- |

- |

| Mae Chan |

MCH05A |

Monzogranite |

0.0700 |

26 |

38 |

24 |

11 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| MCH13C |

Granodiorite |

0.1000 |

32 |

16 |

36 |

11 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| A6 |

granodiorite |

0.0700 |

40 |

34 |

18 |

4.4 |

2.2 |

- |

0.4 |

- |

- |

0.4 |

- |

- |

- |

| B6 |

Monzogranite |

0.1600 |

47 |

25 |

17 |

11 |

|

- |

- |

0.4 |

- |

0.4 |

- |

- |

- |

| C3 |

Monzogranite |

0.1000 |

39 |

23 |

16 |

20 |

2.2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.4 |

- |

- |

- |

Table 3.

U-Pb ages of the granite, cassiterite and wolframite in this study.

Table 3.

U-Pb ages of the granite, cassiterite and wolframite in this study.

| Sample no. |

Materials |

Age (Ma) ± 2σ |

MSDW |

| KA-1 |

zircon |

214.5 ± 1.2 |

1.57 (n=15) |

| KA-15 |

zircon |

214.4 ± 1.3 |

1.33 (n=11) |

| KA-18 |

zircon |

214.2 ± 1.3 |

1.02 (n=11) |

| KA-24 |

zircon |

67.8 ± 0.5 |

1.51 (n=13) |

| KASn02-2 |

zircon |

78.5 ± 0.9 |

1.05 (n=6) |

| MCH05A |

zircon |

225.6 ± 1.2 |

0.76 (n=15) |

| MCH13C |

zircon |

227.4 ± 1.4 |

1.28 (n=12) |

| KASn01 |

cassiterite |

76.6 ± 1.4 |

1.47 (n=19) |

| KASn01 |

wolframite |

79.3 ± 1.6 |

1.5 (n=10) |

| KASn02 |

cassiterite |

80.8 ± 2.8 |

0.72 (n=20) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).