1. Introduction

Proteus mirabilis is a gram-negative, motile, non-sporulating bacterium from the

Enterobacteriaceae family. This bacterium is a pathogen of significant clinical concern, particularly as a leading cause of catheter-associated and complicated urinary tract infections (UTIs), where it is implicated in 10-44% of long-term catheter-associated cases [

1]. Its virulence is enhanced by swarming motility, robust biofilm formation, and urease production, which can lead to severe complications such as urolithiasis, bacteremia, and sepsis [

1,

2]. Importantly, the therapeutic management of

P. mirabilis is increasingly compromised by a high prevalence of antibiotic resistance [

3], with recent studies reporting multi-drug resistance in up to 48% of isolates and the emergence of pan-drug-resistant strains [10.2147/IDR.S448335]. Control of UTIs caused by antibiotic-sensitive

Proteus strains is difficult due to the "shield" provided by the biofilm formation [

4]. The

Proteus features, including the escalating resistance underscores the urgent need for alternative therapeutic strategies, among which phage therapy has re-emerged as a promising precision antimicrobial approach [

5].

Bacteriophages (phages) are traditionally regarded as highly specific antimicrobial agents that lyse their bacterial hosts. However, the clinical efficacy can be limited by narrow host ranges, the potential for bacterial resistance, and complex unpredictable interactions with the host immune system [

6]. In turn, a complex interplay between the particular phage, the infecting bacterium, and the mammalian host's immune system can enhance the efficacy of phage therapy [

7]. This interaction can lead to a beneficial "phage-immune synergy," wherein bacterial clearance is achieved through a combination of direct phage-mediated lysis and the recruitment of host immune components [

8]. Notably, while some phages exhibit immunomodulatory properties, clinical trials using phages as standalone antibacterial agents have sometimes failed to demonstrate clear superiority over standard care, highlighting a gap in our understanding [

9]. Therefore, a pivotal and unresolved question is whether phages function merely as direct lytic agents or can also act as strategic immunomodulators that actively prime and shape pathogen-specific adaptive immunity. Investigating these phage-immune interactions—specifically the potential for phages to serve as immune adjuvants—is essential for optimizing therapeutic protocols, overcoming current limitations, and achieving durable clinical outcomes against resilient pathogens like

P. mirabilis [

10,

11].

It has been shown that phages interact with the mammalian immune system in several ways [

12], including phage phagocytosis [

13], the recognition of phage nucleic acids by intracellular pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), the production of anti-phage antibodies, and the modulation of cytokine responses [

14]. Despite this, the mechanisms by which phages influence the development of adaptive immunity against bacterial pathogens remain poorly understood.

Our previous study demonstrated that intravenous administration of the

P. mirabilis phage PM16 into mice induces a transient increase in blood levels of the tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and interleukins (IL-1β and IL-6) [

15]. However, it fails to elicit a long-term anti-phage antibody response, suggesting an inability of the particular phage to independently induce B-cell memory, possibly due to suppressed IL-27 [

15]. Therefore, it was hypothesized that the PM16 phage could function as an adjuvant during

P. mirabilis infection, enhancing the specific adaptive immune response against the pathogen.

The aim of the current study is to evaluate the effect of PM16 therapy on the course of the first and second P. mirabilis infection in vivo, to investigate the development of a pathogen-specific antibody response, and to elucidate the underlying mechanism by studying the direct interaction between PM16 and macrophages in vitro including production of proinflammatory cytokines and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) as well as macrophage bactericidal activity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

A cohort of two-month-old male Balb/c mice was procured from the animal care facility at the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR in Novosibirsk. Mice were housed under controlled light-dark conditions and provided with food and water ad libitum. All procedures performed on animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of EU Directive 2010/63/EU and received approval from the Inter-institutional Bioethics Committee of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics SB RAS, Russia (protocol code 70, date of approval 21 January 2020).

2.2. P. mirabilis and its Podophage PM16

The

P. mirabilis CEMTC 73 strain and its podophage PM16 [

16] were sourced from the Collection of Extremophilic Microorganisms and Type Cultures (CEMTC) at the Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine (ICBFM), SB RAS, and the bacterial strain was cultivated in Lysogeny Broth (LB) at 37 °C. Previously, the susceptibility of the

P. mirabilis CEMTC 73 strain to antibiotics was tested using the disk diffusion method (OXOID, Basingstoke, UK) in accordance with the EUCAST recommendations (

https://www.eucast.org, accessed: 25 June 2025). The following antimicrobials were used: beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, chloramphenicol, and sulphonamides and it was indicated that this strain is resistant to cefotaxime and levofloxacin.

To propagate the PM16 podophage,

P. mirabilis CEMTC 73 culture was grown to OD600 of 0.6, inoculated with PM16 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1, and incubated at 37 °C with agitation until the onset of bacterial lysis. Phage particles were precipitated from the lysate using polyethylene glycol 8,000 (Appli-Chem, Darmstadt, Germany) in the presence of 2.5 M sodium chloride. Following centrifugation, the resulting pellet was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 8.0. Phage purification was carried out by centrifugation (22,000 rpm, 2 hours, 4 °C) through a cesium chloride gradient [

17]. After dialysis against PBS, the phage titer was measured as 5 × 10¹¹ plaque-forming units per milliliter (PFU/mL).

2.3. Limulus Amebocyte Lysate Assay

To assess endotoxin content, purified PM16 was serially diluted in sterile 0.9% NaCl to final concentrations ranging from 10⁶ to 10¹² PFU/mL. The endotoxin levels of these dilutions were quantified using the Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) assay (Charles River Laboratories Inc., Charleston, SC, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. For parenteral pharmaceutical formulations, an endotoxin concentration of 0.5 endotoxin units (EU) per milliliter is considered acceptable. A PM16 preparation with a titer of 109 PFU/mL was found to correspond to an endotoxin level of 0.5 EU/mL.

2.4. Subcutaneous Infection Model

Balb/c mice were infected with P. mirabilis using 108 CFU in 100 µL of PBS per mouse. One day later, the mice were divided into 4 groups (n = 8), each treated with different con-centration of PM16 (all in 100 µL of PBS): the first group received only PBS, the second, third, and fourth groups were injected with 107 PFU per mouse, 108 PFU per mouse, and 109 PFU per mouse, respectively. All treatments were applied lateral to the site where P. mirabilis was injected. Four weeks after the first P. mirabilis infection, the second P. mirabilis infection procedure was performed (108 CFU in 100 µL of PBS), but without applying the phage therapy. The infiltrate size was monitored on days 3 and 10 after the onset of both the first and second infection. Blood samples were collected two and four weeks after the first infection. Individual serum samples from each mouse were used for immunological experiments.

2.5. Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± SD. For inflammatory infiltrate size at each time point (Days 3 and 10 of the first and second infections), the Brown Forsythe and Welch ANOVA test was used, followed by Games-Howell’s multiple comparisons test to com-pare each phage-treated group to the control group (0 PFU). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.6. Assessment of Serum IgG to P. mirabilis Infection

P. mirabilis cells were immobilized on the surface of 96-well mu-plate (ibidi, Gräfelfing, Germany) and opsonized using the collected mice sera (dilution 1:500) over-night at 4 °C. Then, wells were washed three times with PBS and stained using anti-IgG Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibodies (Invitrogen, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Bacterial cells were stained using intercalating stain Hoechst 33342 (Life technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA). Fluorescent signals were detected using LSM710 confocal microscope at 1000× magnification. Images were acquired using a 405 nm laser line for Hoechst 33342 (detection window: 415–480 nm) and a 488 nm laser line for Alexa Fluor 488 (detection window: 493–580 nm). Sequential scanning was used to eliminate cross-talk between channels. All images were acquired in a single session using identical microscope settings to ensure valid comparison between subgroups. Image seg-mentation and measurement were performed with the CellProfiler software. Object identification was first conducted based on the anti-IgG signal in the AF488 channel to demarcate bacterial cells. Subsequently, segmentation based on the Hoechst signal was per-formed, applying a threshold adjustment of +0.5 µm to the nuclear stain to ensure the resulting masks encompassed the periplasmic space. This established segmentation proto-col was then uniformly applied to all subsequent images from the remaining serum samples. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) per identified bacterial cell was calculated.

2.7. Preparation of Stimulated Macrophages

Primary murine bone marrow–derived macrophages were plated at 5,000 cells per glass-bottom dish or 24-well plates and stimulated with 20 ng/ml Granulocyte–Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) for 24 hours in DMEM/F12 culture medium supplemented with Fetal Culf Serum (10%) at 37 °C.

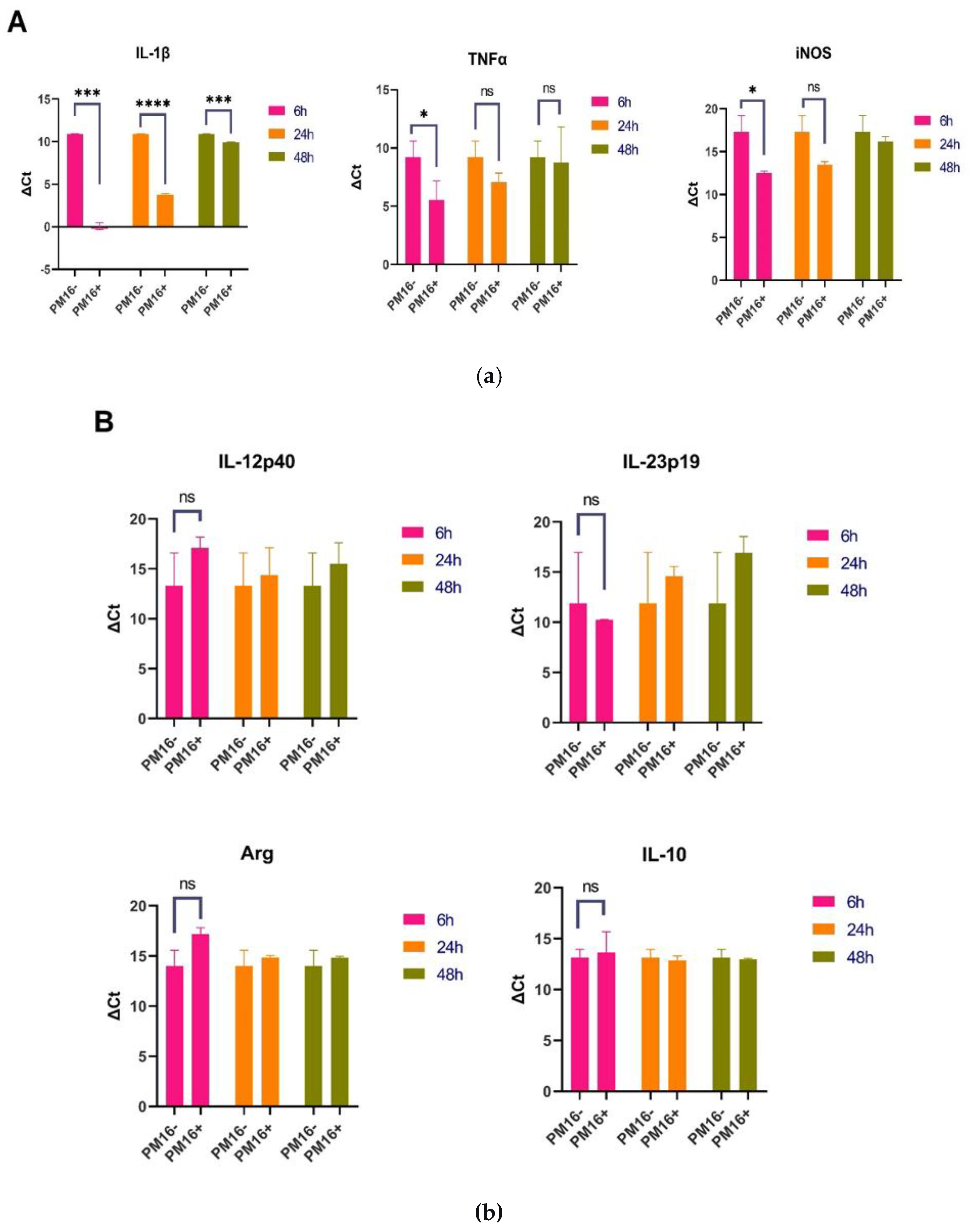

2.8. Real-Time PCR

To characterize the macrophage-intrinsic response to PM16, cytokine and activation marker expression was measured in primary murine bone marrow–derived macro-phages stimulated with GM-CSF and exposed to purified PM16 at a different titer in the absence of bacteria. Total RNA was isolated 6, 24, and 48 hours after phage addition. cDNA was synthesized using standard reverse transcription procedures, and transcript levels of proinflammatory (IL-1β, TNFα, iNOS), regulatory (IL-10), and polarization-associated (Arg1, IL-12p40, IL-23p19) genes were quantified by real-time PCR using gene-specific intron-skipping primers (

Table 1) designed with NCBI Primer-BLAST tool so that each primer should cover exon-exon junction on target mRNA. The amplification was performed using BioMaster RT-qPCR SYBR Blue (Biolabmix LLC, Novosibirsk, Russia) and the real-time machine CFX96 (Biorad, USA). The conditions for PCR were as follow: Initial denaturation 95°C (5 minutes); Cycling: 95°C for 15 sec, Annealing Tm+3°C for 15 seconds, Elongation 72°C for 30 seconds. The maximum number of 34 cycles were utilized for each primer set. Relative expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method, with GM-CSF–stimulated macrophages without PM16 serving as the reference control. Gene expression values were normalized to β-actin (Actb) as the housekeeping gene. All data were presented as mean ± SD. For cytokine production level at each time point, the Welch’s t test was used. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

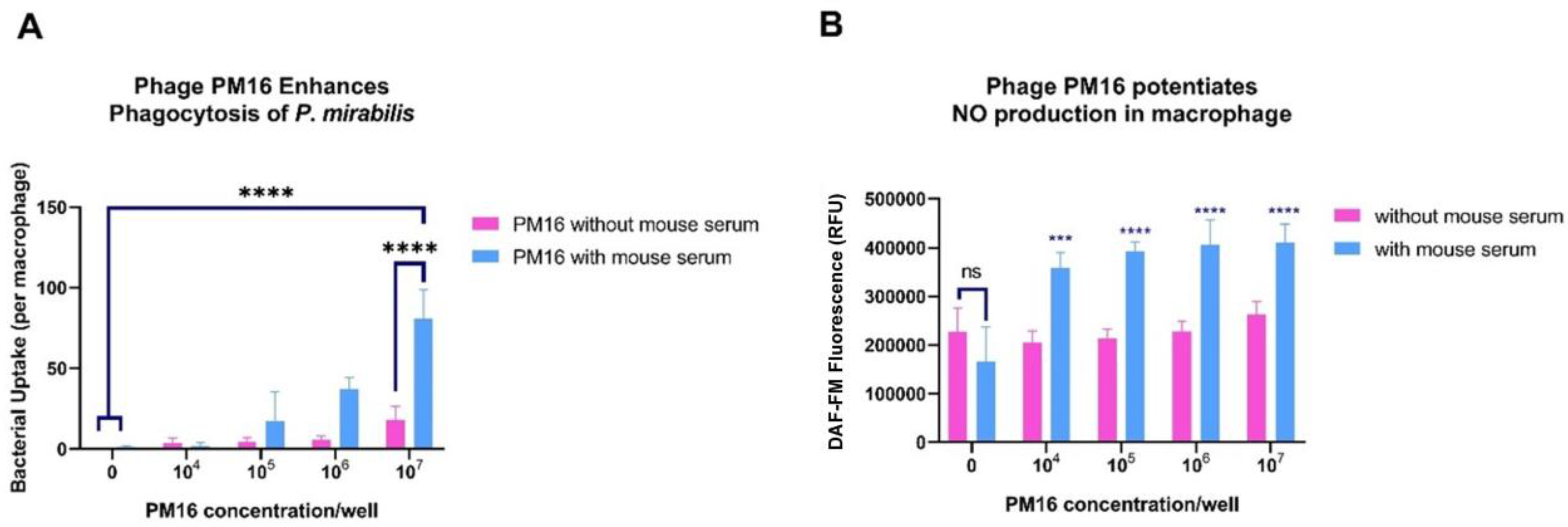

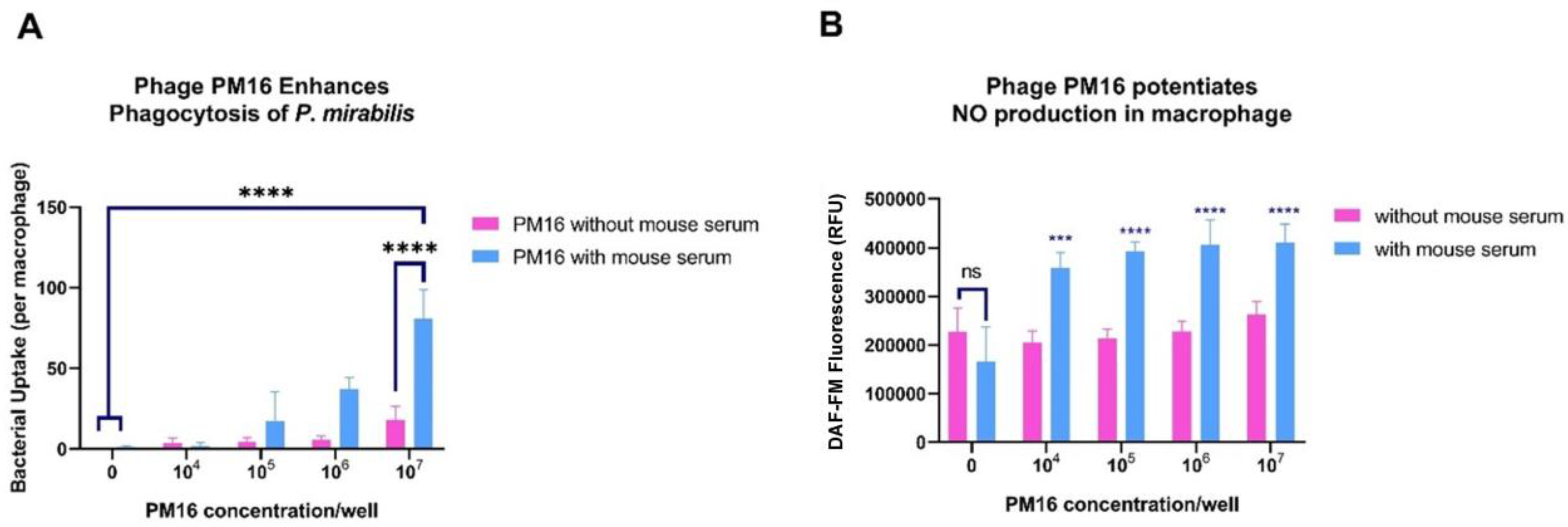

2.9. Microscopy and Bacterial Enumeration

To determine whether PM16 enhances macrophage capacity for bacterial uptake and intracellular killing, GM-CSF-stimulated primary murine bone marrow–derived macrophages were then incubated with purified PM16 for 30 minutes at different titers (0, 104 PFU/mL, 105 PFU/mL, 106 PFU/mL, or 107 PFU/mL). Hoechst-labelled P. mirabilis was added at 10⁷ CFU/well in the presence or absence of normal mouse serum obtained from non-immune BALB/c mice (The serum has been characterized as non-binding for P. mirabilis and PM16 with ELISA and microscopy experiments). Macrophages were imaged 5 hours after bacterial addition using confocal microscopy. Intracellular bacteria were enumerated using CellProfiler software and the median number of bacteria per macrophage was calculated. Three independent experiments were per-formed, yielding three biological replicates per group. All data are presented as mean ± SD. For bacterial enumeration at each PM16 concentration, the Two-way ANOVA test was used, followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This approach enabled quantitative assessment of phage-induced enhancement of bacterial internalization.

2.10. Measurement of Nitric Oxide Production

To assess nitric oxide (NO) production in response to PM16 exposure, primary murine bone marrow–derived macrophages were seeded at 5,000 cells per glass-bottom dish and stimulated with GM-CSF for 24 hours. Cells were subsequently incubated with purified PM16 for 5 hours at concentrations of 0, 10⁴, 10⁵, 10⁶, or 10⁷ PFU/well. Intracellular NO production was quantified by adding the fluorescent probe DAF-FM diacetate (SA100, Lumiprobe, Beutelsbach, Baden-Württemberg) to the cultures, followed by measurement of fluorescence intensity using Flow Cytometer Novocyte 3000 (ACEA biosciences, USA). Fluorescence values from GM-CSF–only controls were used as the baseline for comparison. Two-way ANOVA test was used to estimate NO production by macriphages, followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This assay enabled evaluation of PM16-induced enhancement of macrophage nitric oxide production.

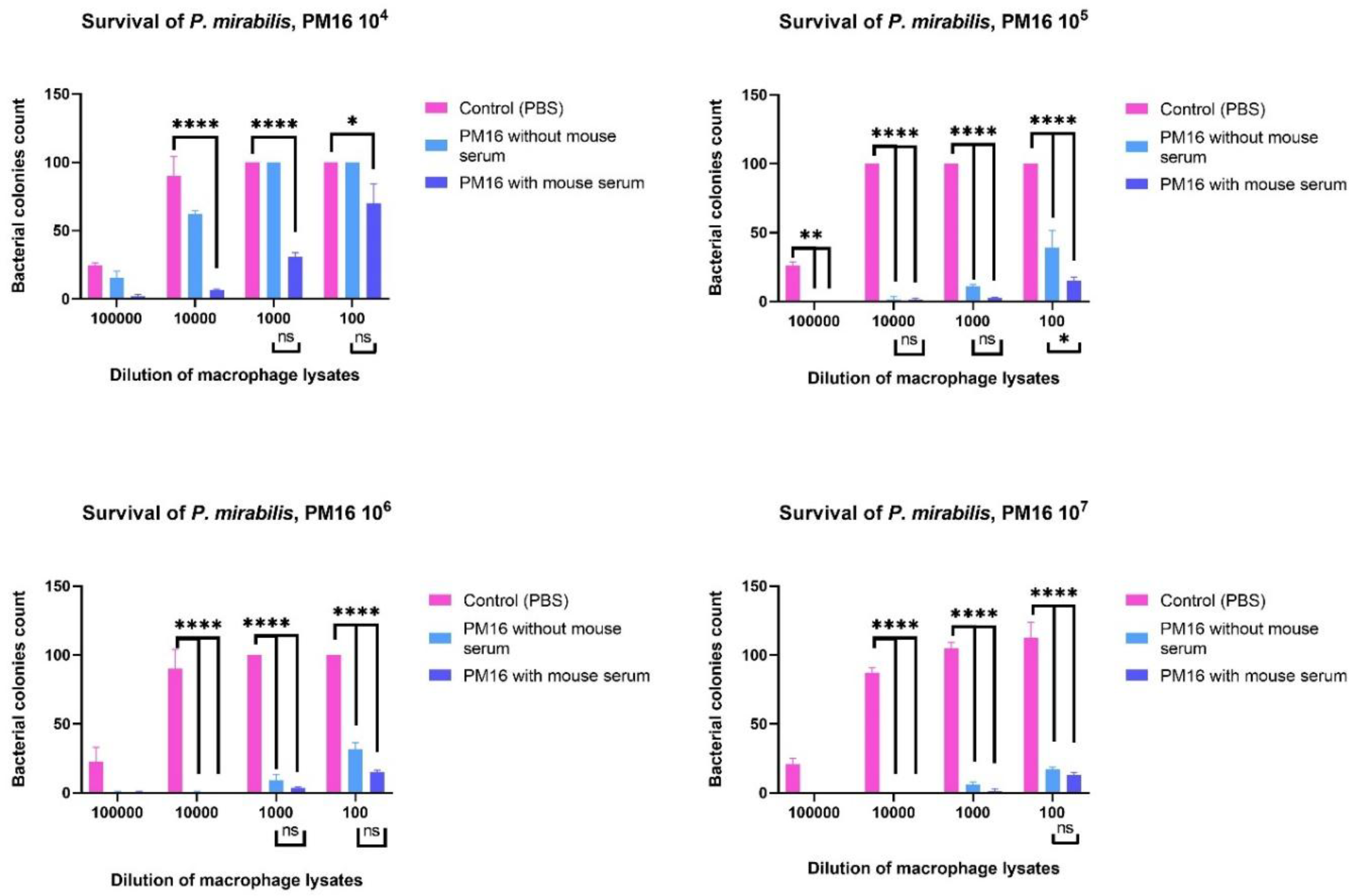

2.11. Analysis of Bacterial Survival Within Macrophages

To quantify the impact of PM16 on intracellular P. mirabilis survival, GM-CSF-stimulated primary murine bone marrow–derived macrophages were seeded into 24-well plates, stimulated with GM-CSF for 24 h, and then exposed to P. mirabilis (10⁷ CFU/ well) for 5 h. After the loading period, cultures were treated with PM16 at the indicated titers (0, 104 PFU/mL, 105 PFU/mL, 106 PFU/mL, or 107 PFU/mL) with or without the addition of mouse serum. Twenty-four hours after phage addition, macrophages were lysed with sterile water to release intracellular bacteria. Lysates were serially diluted (1:100; 1:1,000; 1:10,000; and 1:100,000) and plated onto non-selective agar plates to enumerate viable P. mirabilis colonies. Plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C and CFU per dilution were counted; confluent growth was recorded as >100 colonies. The number of colonies recovered from macrophage lysates was used to assess PM16-dependent, dose-responsive effects on intracellular bacterial viability. Data were analyzed using Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

3. Results

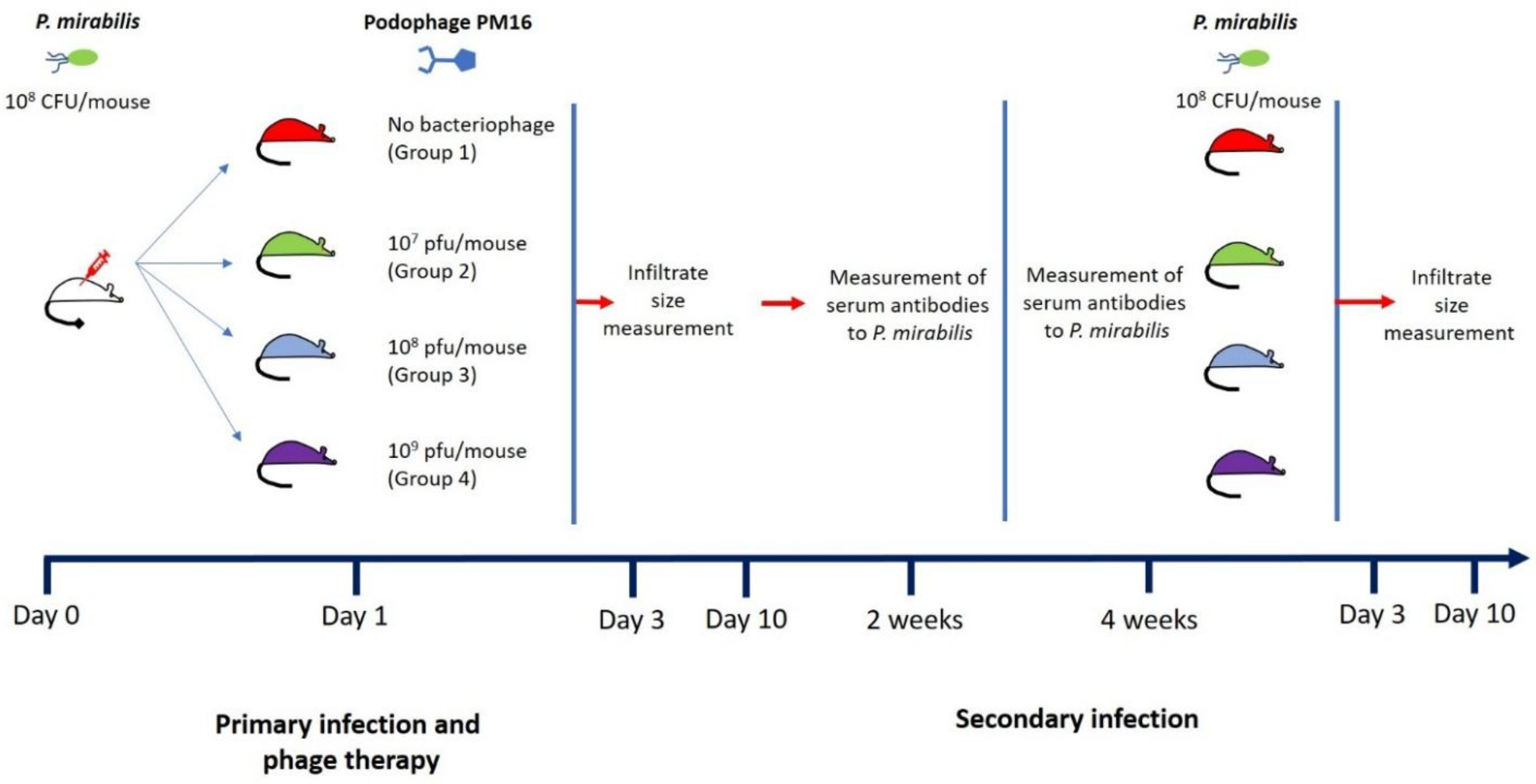

3.1. PM16 Phage Therapy Attenuates P. mirabilis Infection and Induces Long-Term Protective Immunity

To evaluate the therapeutic and immunomodulatory efficacy of the PM16 phage

in vivo, we established a murine model of subcutaneous

P. mirabilis infection. Mice were infected with 10

8 CFU of P. mirabilis and, after 24 hours, received a single dose of PM16 at varying titers (0, 10

7 PFU/mouse, 10

8 PFU/mouse, or 10

9 PFU/mouse) lateral to the infection site (

Figure 1). The primary outcome measure was the size of the local inflammatory infiltrate.

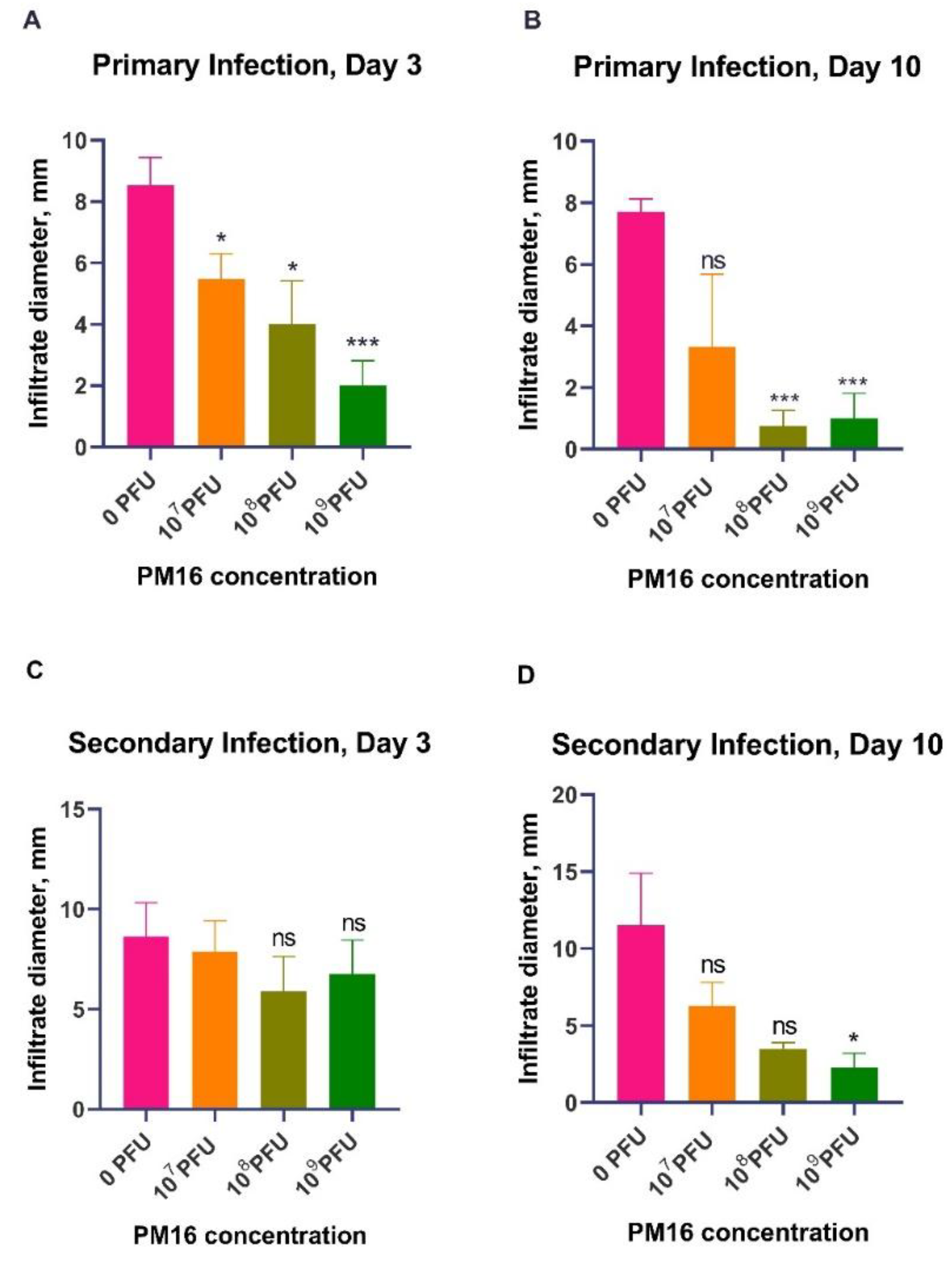

PM16 therapy exhibited a significant, dose-dependent reduction in infiltrate size during

P. mirabilis infection (

Figure 2A). By day 3 post-infection, all phage-treated groups had notably smaller infiltrates compared to the control group (0 PFU). The control group developed infiltrates with a mean size of 8.5 mm, while mice treated with 10

9 PFU of PM16 exhibited a mean infiltrate size of 2.0 mm (p = 0.0002). This therapeutic effect became more pronounced by day 10 (

Figure 2B). While the control group still presented significant infiltrates (mean = 7.7 mm), the protective effect was the highest in the 10

8 PFU and 10

9 PFU groups (mean = ~1.0 mm, p ≤ 0.0002), with several mice showing complete resolution. In contrast, the lowest dose (10

7 PFU) was no longer different from the control by day 10 (p = 0.094), underscoring the dose-dependent nature of the response.

To determine residual immunity after the bacterial clearance, we challenged the same mice with the second

P. mirabilis infection four weeks later, without phage therapy (

Figure 1). The measurement of the size of the local inflammatory infiltrate upon reinfection indicated that a single prior treatment with PM16 induced robust, dose-dependent protective immunity (

Figure 2C, 2D). Mice initially treated with high-dose PM16 (10

8 and 10

9 PFU) were profoundly protected. On day 3, no significant difference was observed in infiltrate sizes. The control group and mice that were injected with 10

7 PFU mean infiltrate sizes of were 8.6 and 7.8 mm while groups that were injected with 10

8 and 10

9 PFU during first infection had slightly lower (though not significantly) mean infiltrate sizes of 5.9 and 6.8 mm. However, by day 10, we have observed the pattern of decreased infiltrate sizes in accordance with the increased bacteriophage dose during the first injection, with mean in-filtrate size for Group 3 and Group 4 of 3.5 mm (p < 0.001) and 2.25 mm (p = 0.002). In stark contrast, the control group developed infiltrates of a similar magnitude during both infections (mean = 11 mm). The lowest dose group (107 PFU) also showed decreased but not statistically significant mean infiltrate size of 6.3 mm compared to the control (

Figure 2C, 2D).

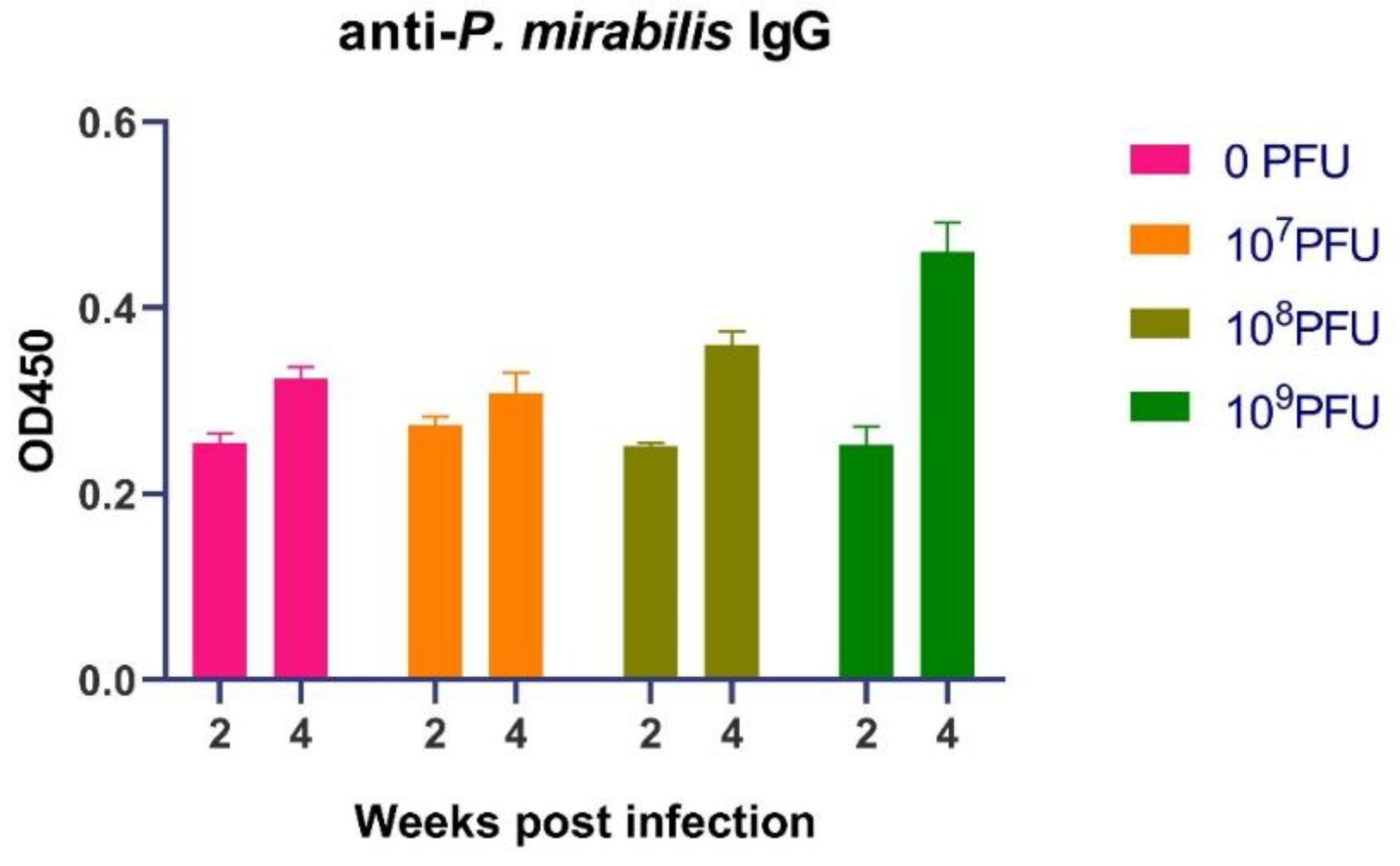

3.2. PM16 Phage Therapy Potentiates a Robust and Sustained Humoral Immune Response against P. mirabilis

The protection against reinfection suggested the induction of adaptive immuno-logical memory. To investigate the role of humoral immunity, we quantified serum levels of P. mirabilis-specific IgG following the first infection. The initial humoral response, measured at two weeks post infection, was uniform across all groups (

Figure 3). IgG levels in all cohorts clustered within a narrow range (approximately 0.225 to 0.285 OD), indicating a nascent, low-titer antibody response. This early equivalence confirms that the initial antigenic stimulus was consistent across all mice.

A divergence in IgG titers emerged at the four-week mark. While the control group (0 PFU) and the low-dose phage group (10

7 PFU) showed only a moderate increase, the groups that received higher phage doses exhibited a pronounced and significant boost in antigen-specific antibody levels (

Figure 3). The response was dose-dependent. The 10

8 PFU-group showed enhanced IgG, with values (0.368–0.376 OD) exceeding those of the control group (~0.31–0.33 OD). The 10

9 PFU-group demonstrated the most robust response, with peak IgG levels reaching approximately 0.48 OD, representing a nearly 1.5-fold in-crease over the control group's peak.

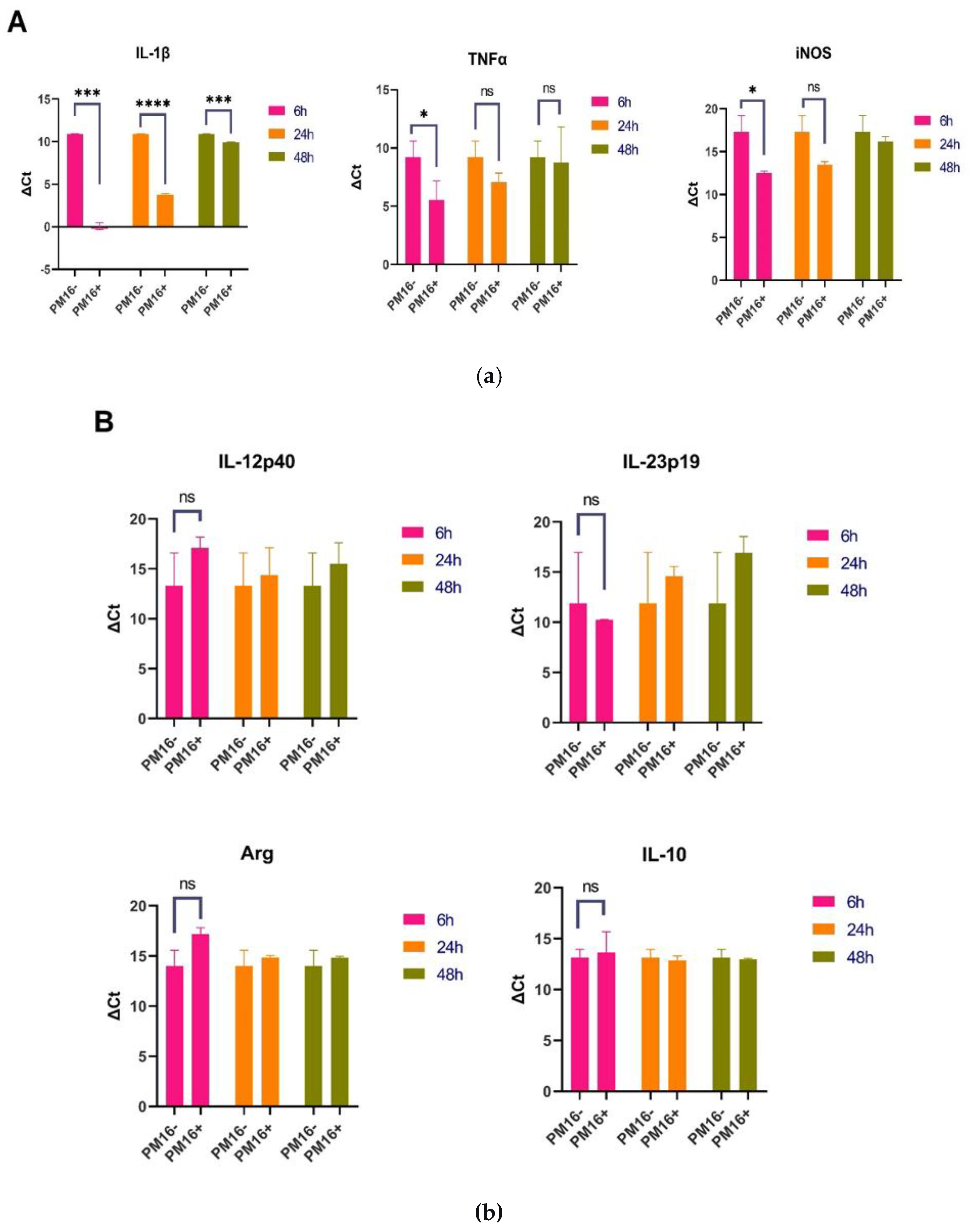

3.3. PM16 Phage Activates Macrophages, Inducing Proinflammatory Cytokines and iNOS

The Given that PM16 therapy enhances adaptive immunity in vivo, we investigated the underlying cellular mechanisms. We hypothesized that the phage primes innate im-munity, with macrophages as a primary target. We therefore analyzed the direct transcriptional response of primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages to PM16 (109 PFU/ml) exposure in the absence of bacteria.

PM16 directly induced a robust proinflammatory gene expression profile in macrophages, consistent with classical M1 polarization (Figure 4A). Six hours post-stimulation, the most pronounced upregulation was observed in the gene encoding IL-1β, which increased over 146-fold relative to GM-CSF-stimulated controls (p<0.001). Expression of TNFα was also significantly elevated, showing an approximate 17-fold in-crease (p<0.05). Furthermore, we observed substantial upregulation of iNOS, with expression levels increased 24- to 31-fold (p<0.05). This shift suggests that PM16 not only triggers inflammatory signaling, but also equips macro-phages with machinery for enhanced direct bacterial killing.

This proinflammatory signature was specific. Expression of IL-12p40 was negligible, and IL-23p19 was uninduced (Figure 4B). Markers associated with alternative (M2) activation, Arginase-1 (Arg) and IL-10, remained at baseline levels. The strong induction of IL-1β, TNFα, and iNOS without a concomitant rise in Arg or IL-10 defines a macro-phage activation state skewed toward host defense.

The macrophage response to PM16 was temporally regulated. By 48 hours post-stimulation, the cytokine landscape had evolved. The upregulation of IL-1β had sub-sided to a modest 2-fold increase, whereas TNFα expression became more variable. In contrast, iNOS expression remained elevated above baseline (2- to 3-fold), suggesting a sustained potential for antimicrobial activity (Figure 4A). The absence of IL-23p19, Arg, and IL-10 expressions was maintained (Figure 4B).

3.4. PM16 Enhances the Bactericidal Activity of Macrophages against P. mirabilis

Taking into consideration that PM16 drives macrophages toward a proinflammatory state, we next assessed whether this activation enhances their ability to internalize and kill P. mirabilis. Using a combination of microscopy, fluorescence assays, and bacteriological culture, we evaluated bacterial uptake, NO production, and intracellular killing. Pre-incubation with PM16 significantly increased bacterial internalization by macrophages (Figure 5A). In the presence of normal mouse serum, the median bacterial count per macrophage rose with increasing phage doses. At the highest phage concentration (107 PFU/well), the median bacterial load reached 64-100 bacteria per cell, compared to 0-2 bacteria per cell in the no-phage control (p<0.0001).

Next, we measured NO production, a key bactericidal mechanism of activated macrophages. PM16 treatment, in the presence of murine serum, triggered an increase in NO production (Figure 4B) in comparison with control, stimulated with GM-CSF only, group (p≤0.0003).

To determine the net effect on bacterial viability, we performed a survival assay by lysing macrophages 24 hours post-treatment with PM16 and enumerating viable bacteria (Figure 6). PM16 treatment resulted in a dose-dependent reduction in recoverable colonies. At 105 PFU/well, colony counts at the 1:100,000 dilution decreased from ~25 in controls to 0-3 in PM16-treated groups. At 107 PFU/well, the bactericidal effect was nearly complete, with minimal colony formation even at lower dilutions, while controls showed confluent growth (recorded as 100+ colonies). No significant difference was detected in between “without serum” and “with serum” groups.

4. Discussion

In this study, we present evidence that the Proteus phage PM16 acts not only as an antibacterial agent, but also as a potent modulator of the immune response, enhancing the development of long-term, specific immunity against its bacterial host, P. mirabilis.

Our

in vivo results clearly indicated a dose-dependent protective effect of PM16 during both the first and second infections. In addition, the consequences of the protective effect of a single PM16 treatment were observed when mice were injected with

P. mirabilis in a month after treatment. This protective immunity was directly correlated with elevated levels of pathogen-specific IgG, indicating the successful induction of a robust adaptive immune response. Crucially, since we have previously shown that PM16 alone is unable to induce a long-term anti-phage antibody response [

15], the observed enhancement cannot be attributed to the immunogenicity of the phage virions themselves. This finding contradicts the hypothesis that PM16 functions as a classic antigenic adjuvant.

Instead, we propose a mechanism centered on the priming of innate immunity. Our

in vitro experiments established that PM16 is a direct and potent activator of macro-phages, driving a specific transcriptional program, which is consistent with classical M1 polarization. The potent induction of proinflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β) likely oc-curs through the recognition of phage nucleic acids by intracellular pattern recognition receptors, such as TLR9, a common pathway for immunostimulatory phages [

18]. This activation is characterized by a robust, early upregulation of these key cytokines and a sustained induction of iNOS. More importantly, we demonstrated that this transcriptional shift is functionally significant: PM16-treated macrophages exhibit a dramatic increase in both bacterial uptake and intracellular killing. This aligns with the established concept of phage-mediated opsonization [

12,

19,

20], where phages coating bacteria enhance their recognition and phagocytosis by immune cells. The potent, dose-dependent reduction in recoverable bacterial colonies in our survival assay confirms that the increased phagocyto-sis culminates in enhanced bacterial clearance, with nitric oxide being a key mediator of this bactericidal effect.

Thus, we hypothesize that PM16 exerts a dual function during therapy: (1) direct lytic activity that reduces the bacterial load, and (2) immune modulation that primes macrophages, leading to a more aggressive and effective innate immune response. This combined activity creates an immunological environment conducive to the development of a potent adaptive response. The efficient clearance of bacteria by activated macrophages likely facilitates superior antigen presentation and T-cell help, ultimately driving the clonal expansion and affinity maturation of B-cells that we observed as elevated, durable IgG titers.

Our observation that PM16 induces a strong proinflammatory cytokine profile stands in contrast to studies of other phages, such as T4, which have demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties, including the inhibition of NF-κB and reduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in immune cells [

21]. This highlights the critical concept that phage-immune interactions are phage-specific. The immune net outcome—whether pro-inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, or neutral—depends on the specific phage, its structural components, and its interaction with host receptors [

12,

22]. The robust M1 polarization induced by PM16 suggests it engages different signaling pathways than other phages, which elicited anti-inflammatory markers like IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL1RN) or suppress LPS-driven inflammation [

22,

23,

24]. This specificity underscores the importance of a detailed characterization of the immunomodulatory "fingerprint" of each therapeutic phage candidate.

Finally, the translational implication of this primed state is significant. By enhancing phagocytosis and intracellular killing, PM16 not only aids in direct bacterial clearance but also promotes more efficient processing of bacterial antigens. This process is essential for linking innate detection to adaptive immunity. The observed long-term protective memory likely stems from this optimized antigen presentation, a hypothesis supported by models of phage-immune synergy [

25] where effective pathogen handling by primed innate cells is a prerequisite for durable adaptive responses. Future work should directly trace the fate of bacterial antigens from PM16-treated mice to B and T-cell activation to con-firm this proposed link.

In conclusion, this study repositions the PM16 podophage from a simple antibacterial agent to an active partner and primer of the immune system. Its specific capacity to skew macrophages toward a bactericidal, proinflammatory phenotype via innate receptor recognition creates a local microenvironment that ensures effective pathogen clearance and orchestrates a superior adaptive immune response, resulting in durable protection against reinfection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.C., N.V.T.; Investigation, L.A., A.V.C., V.V.M., Y.N.K., T.A.U.; Data Curation, V.V.M., Y.N.K.; Visualization, L.A., A.V.C.; Formal analysis, L.A., A.V.C.; Project administration, A.V.C., N.V.T.; writing—original draft, L.A., A.V.C.; writing—review and editing, A.V.C., N.V.T.; Supervision, N.V.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Russian Scientific Foundation, research project No. 25-64-00030. Bacterial strain Proteus mirabilis CEMTC 73 and PM16 phage were obtained and cultivated by the staff of the Collection of Extremophilic Microorganisms and Type Cultures of ICBFM SB RAS, which is supported by the Ministry of Education and Science, Project No. 125012300671-8.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Inter-institutional Bioethics Committee of Institute of Cytology and Genetics Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk, Russia (protocol code 70, date of approval 21 January 2020).

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schaffer, J.N.; Pearson, M.M. Proteus Mirabilis and Urinary Tract Infections. Microbiol Spectr 2015, 3. [CrossRef]

- Complicated Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections Due to Escherichia Coli and Proteus Mirabilis | Clinical Microbiology Reviews Available online: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/cmr.00019-07 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Stock, I. Natural Antibiotic Susceptibility of Proteus Spp., with Special Reference to P. Mirabilis and P. Penneri Strains. J Chemother 2003, 15, 12–26. [CrossRef]

- Kynshi, M.A.L., Kharkamni, E., Borah, V.V. Proteus mirabilis: Insights into biofilm formation, virulence mechanisms, and novel therapeutic strategies. The Microbe 2025, 8, 100450. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Yu, Y. Phage therapy as a revitalized weapon for treating clinical diseases. Microbiome Res Rep 2025, 4, 35. [CrossRef]

- Youssef, R.A., Sakr, M., Shebl, R.I., Aboshanab, K.M. Recent insights on challenges encountered with phage therapy against gastrointestinal-associated infections. Gut Pathogens 2026, 17, 60. [CrossRef]

- Levin, B.R.; Bull, J.J. Population and Evolutionary Dynamics of Phage Therapy. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004, 2, 166–173. [CrossRef]

- Marchi, J.; Zborowsky, S.; Debarbieux, L.; Weitz, J.S. The Dynamic Interplay of Bacteriophage, Bacteria and the Mammalian Host during Phage Therapy. iScience 2023, 26, 106004. [CrossRef]

- Weissfuss, C., Li, J., Behrendt, U., Hoffmann, K., Bürkle, M., Tan, C., Krishnamoorthy, G., Korf, I., Rohde, C., Gaborieau, B., Debarbieux, L., Ricard, J-D., Witzenrath, M., Felten, M., Nouailles, G. Adjunctive phage therapy improves antibiotic treatment of ventilator-associated-pneumonia with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 4500. [CrossRef]

- Górski, A., Dąbrowska, K., Międzybrodzki, R., Weber-Dąbrowska, B., Łusiak-Szelachowska, M., Jończyk-Matysiak, E., Borysowski, J. Phages and immunomodulation. Future Microbiol 2017, 12, 905-914. [CrossRef]

- Górski, A., Międzybrodzki, R., Łobocka, L., Głowacka-Rutkowska, A., Bednarek, A., Borysowski, J., Jończyk-Matysiak, E., Łusiak-Szelachowska, M., Weber-Dąbrowska, B., Bagińska, N., Letkiewicz, S., Dąbrowska, K., Scheres, J. Phage Therapy: What Have We Learned? Viruses 2018, 10, 288. [CrossRef]

- Van Belleghem, J.; Dąbrowska, K.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Barr, J.; Bollyky, P. Interactions between Bacteriophage, Bacteria, and the Mammalian Immune System. Viruses 2018, 11, 10. [CrossRef]

- Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Owczarek, B.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Łusi-ak-Szelachowska, M.; Łodej, N.; Górski, A. Phage-Phagocyte Interactions and Their Implications for Phage Application as Therapeutics. Viruses 2017, 9, 150. [CrossRef]

- Podlacha, M.; Grabowski, Ł.; Kosznik-Kawśnicka, K.; Zdrojewska, K.; Stasiłojć, M.; Węgrzyn, G.; Węgrzyn, A. Interactions of Bacteriophages with Animal and Human Organisms—Safety Issues in the Light of Phage Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 8937. [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, J.N.; Pearson, M.M. Proteus Mirabilis and Urinary Tract Infections. Microbiol Spectr 2015, 3. [CrossRef]

- Complicated Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections Due to Escherichia Coli and Proteus Mirabilis | Clinical Microbiology Reviews Available online: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/cmr.00019-07 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Stock, I. Natural Antibiotic Susceptibility of Proteus Spp., with Special Reference to P. Mirabilis and P. Penneri Strains. J Chemother 2003, 15, 12–26. [CrossRef]

- Chechushkov, A.; Kozlova, Y.; Baykov, I.; Morozova, V.; Kravchuk, B.; Ushakova, T.; Bardasheva, A.; Zelentsova, E.; Allaf, L.A.; Tikunov, A.; et al. Influence of Caudovirales Phages on Humoral Immunity in Mice. Viruses 2021, 13, 1241. [CrossRef]

- Morozova, V.; Kozlova, Yu.; Shedko, E.; Kurilshikov, A.; Babkin, I.; Tupikin, A.; Yunusova, A.; Chernonosov, A.; Baykov, I.; Кondratov, I.; et al. Lytic Bacteriophage PM16 Specific for Proteus Mirabilis: A Novel Member of the Genus Phikmvvirus. Arch Virol 2016, 161, 2457–2472. [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual; 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y, 2001; Vol. 1; ISBN 978-0-87969-577-4.

- Popescu, M.; Van Belleghem, J.D.; Khosravi, A.; Bollyky, P.L. Bacteriophages and the Immune System. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2021, 8, annurev-virology-091919-074551. [CrossRef]

- Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Łusiak-Szelachowska, M.; Kłak, M.; Bubak, B.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Żaczek, M.; Fortuna, W.; Rogóż, P.; Letkiewicz, S.; et al. The Effect of Bacteriophage Preparations on Intracellular Killing of Bacteria by Phagocytes. J Immunol Res 2015, 2015, 482863. [CrossRef]

- Górski, A.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Borysowski, J.; Dąbrowska, K.; Wierzbicki, P.; Ohams, M.; Korczak-Kowalska, G.; Olszowska-Zaremba, N.; Łusiak-Szelachowska, M.; Kłak, M.; et al. Phage as a Modulator of Immune Responses: Practical Implications for Phage Therapy. Adv Virus Res 2012, 83, 41–71. [CrossRef]

- Międzybrodzki, R.; Borysowski, J.; Kłak, M.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Obmińska-Mrukowicz, B.; Suszko-Pawłowska, A.; Bubak, B.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Górski, A. In Vivo Studies on the Influence of Bacteriophage Preparations on the Autoimmune Inflammatory Process. Biomed Res Int 2017, 2017, 3612015. [CrossRef]

- Bacteriophage Preparation Inhibition of Reactive Oxygen Species Generation by Endotoxin-Stimulated Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes - PubMed Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17996972/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- T4 Phage Tail Adhesin Gp12 Counteracts LPS-Induced Inflammation In Vivo - Pub-Med Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27471503/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Responses of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells Induced by Staphylococcus Aureus and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Phages | Scientific Re-ports Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-08336-9 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Roach, D.R.; Leung, C.Y.; Henry, M.; Morello, E.; Singh, D.; Di Santo, J.P.; Weitz, J.S.; Debarbieux, L. Synergy between the Host Immune System and Bacteriophage Is Essential for Successful Phage Therapy against an Acute Respiratory Pathogen. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 38-47.e4. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Subcutaneous P. mirabilis infection model.

Figure 1.

Subcutaneous P. mirabilis infection model.

Figure 2.

Persistence PM16 phage therapy attenuates primary infection and confers protective immunity against P. mirabilis reinfection. (A, B) Primary infection. Mice (n=8 per group) were infected subcutaneously with 108 CFU of P. mirabilis and treated 24 hours later with a single dose of PM16 (0, 107 PFU, 108 PFU, or 109 PFU). Inflammatory infiltrate size was measured on day 3 (A) and day 10 (B) post-infection. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was determined by Welch's ANOVA with Dunnett's T3 post-hoc test comparing each group to the control (0 PFU). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. (C, D) The second infection challenge. The same cohorts of mice were rechallenged with P. mirabilis at the contralateral site four weeks after the primary infection, without phage therapy. Infiltrate size was measured on day 3 (C) and day 10 (D) post-reinfection. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis as in (A, B).

Figure 2.

Persistence PM16 phage therapy attenuates primary infection and confers protective immunity against P. mirabilis reinfection. (A, B) Primary infection. Mice (n=8 per group) were infected subcutaneously with 108 CFU of P. mirabilis and treated 24 hours later with a single dose of PM16 (0, 107 PFU, 108 PFU, or 109 PFU). Inflammatory infiltrate size was measured on day 3 (A) and day 10 (B) post-infection. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was determined by Welch's ANOVA with Dunnett's T3 post-hoc test comparing each group to the control (0 PFU). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. (C, D) The second infection challenge. The same cohorts of mice were rechallenged with P. mirabilis at the contralateral site four weeks after the primary infection, without phage therapy. Infiltrate size was measured on day 3 (C) and day 10 (D) post-reinfection. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis as in (A, B).

Figure 3.

PM16 phage therapy potentiates a robust and sustained humoral immune response against P. mirabilis. Serum levels of P. mirabilis-specific IgG were measured by ELISA at two and four weeks post-primary infection in mice (n = 8 per group) treated with the indicated doses of PM16. At two weeks, all groups showed equivalent, low-level IgG titers, confirming a consistent initial antigenic stimulus. By four weeks, a significant, dose-dependent enhancement of the antibody response was observed in the high-dose phage groups. Data are presented as individual data points with mean ± SEM.

Figure 3.

PM16 phage therapy potentiates a robust and sustained humoral immune response against P. mirabilis. Serum levels of P. mirabilis-specific IgG were measured by ELISA at two and four weeks post-primary infection in mice (n = 8 per group) treated with the indicated doses of PM16. At two weeks, all groups showed equivalent, low-level IgG titers, confirming a consistent initial antigenic stimulus. By four weeks, a significant, dose-dependent enhancement of the antibody response was observed in the high-dose phage groups. Data are presented as individual data points with mean ± SEM.

Figure 4.

PM16 phage directly induces a specific and temporally regulated proinflammatory program in macrophages. Primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages were stimulated with PM16 (109 PFU/ml). Gene expression of key markers was analyzed by RT-qPCR at 6, 24, and 48 hours post-stimulation and is presented as fold change relative to GM-CSF-stimulated controls. (A) PM16 induced a robust, early proinflammatory response. At 6 hours, significant upregulation of IL-1β (>146-fold), TNFα (~17-fold), and iNOS (24-31 fold) was observed. By 48 hours, cytokine expression subsided, while iNOS remained elevated. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by Welch’s t test; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 vs. control at the respective time point. (B) The PM16-induced signature was specific. Expression of IL-12p40, IL-23p19, Arginase-1 (Arg), and IL-10 remained at baseline levels (approximately 1-fold change) at both time points, indicating a clear polarization toward a classical (M1) activation state without induction of alternative (M2) or other inflammatory markers.

Figure 4.

PM16 phage directly induces a specific and temporally regulated proinflammatory program in macrophages. Primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages were stimulated with PM16 (109 PFU/ml). Gene expression of key markers was analyzed by RT-qPCR at 6, 24, and 48 hours post-stimulation and is presented as fold change relative to GM-CSF-stimulated controls. (A) PM16 induced a robust, early proinflammatory response. At 6 hours, significant upregulation of IL-1β (>146-fold), TNFα (~17-fold), and iNOS (24-31 fold) was observed. By 48 hours, cytokine expression subsided, while iNOS remained elevated. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by Welch’s t test; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 vs. control at the respective time point. (B) The PM16-induced signature was specific. Expression of IL-12p40, IL-23p19, Arginase-1 (Arg), and IL-10 remained at baseline levels (approximately 1-fold change) at both time points, indicating a clear polarization toward a classical (M1) activation state without induction of alternative (M2) or other inflammatory markers.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic PM16 enhances bacterial uptake and NO production in macrophages. (A) Bacterial internalization by macrophages. Primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages were pretreated with the indicated doses of PM16 for 30 minutes and then infected with P. mirabilis (10⁷ CFU/well) in the presence or absence of normal mouse serum. Intracellular bacteria were enumerated by confocal microscopy 5 hours post-infection. Data are presented as the median number of bacteria per macrophage from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test; ****p < 0.0001 compared to the no-phage control. (B) NO production in macrophages. Macrophages were treated with the indicated doses of PM16 for 5 hours in the presence or absence of serum, and intracellular NO was measured using DAF-FM fluorescence. Data are presented as fluorescence intensity relative to GM-CSF-only controls from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test; ***p ≤ 0.0003 compared to the control group.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic PM16 enhances bacterial uptake and NO production in macrophages. (A) Bacterial internalization by macrophages. Primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages were pretreated with the indicated doses of PM16 for 30 minutes and then infected with P. mirabilis (10⁷ CFU/well) in the presence or absence of normal mouse serum. Intracellular bacteria were enumerated by confocal microscopy 5 hours post-infection. Data are presented as the median number of bacteria per macrophage from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test; ****p < 0.0001 compared to the no-phage control. (B) NO production in macrophages. Macrophages were treated with the indicated doses of PM16 for 5 hours in the presence or absence of serum, and intracellular NO was measured using DAF-FM fluorescence. Data are presented as fluorescence intensity relative to GM-CSF-only controls from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test; ***p ≤ 0.0003 compared to the control group.

Figure 6.

PM16 treatment enhances intracellular killing of P. mirabilis by macrophages in a dose-dependent manner. Primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages were infected with P. mirabilis (10⁷ CFU/well) for 5 hours and then treated with the indicated doses of PM16, with or without mouse serum. Twenty-four hours post-treatment, macrophages were lysed, and the lysates were plated at the indicated dilutions to enumerate viable intracellular bacteria via colony counting. Data are representative of three independent experiments. PM16 treatment resulted in a significant, dose-dependent reduction in recoverable colonies, with near-complete bacterial clearance at the highest dose (107 PFU/well). Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 6.

PM16 treatment enhances intracellular killing of P. mirabilis by macrophages in a dose-dependent manner. Primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages were infected with P. mirabilis (10⁷ CFU/well) for 5 hours and then treated with the indicated doses of PM16, with or without mouse serum. Twenty-four hours post-treatment, macrophages were lysed, and the lysates were plated at the indicated dilutions to enumerate viable intracellular bacteria via colony counting. Data are representative of three independent experiments. PM16 treatment resulted in a significant, dose-dependent reduction in recoverable colonies, with near-complete bacterial clearance at the highest dose (107 PFU/well). Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Sidak's multiple comparisons test.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used for RT-PCR analysis.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used for RT-PCR analysis.

| Cytokine |

Primer set |

Tm |

| Murine IL-1b |

Forward: 5’ TGCCACCTTTTGACAGTGATG 3’

Reverse: 5’ TGATGTGCTGCTGCGAGATT 3’ |

60 |

| Murine IL12p40 |

Forward: 5’ GGAGGGGTGTAACCAGAAAGG 3’

Reverse: 5’ TAGCGATCCTGAGCTTGCAC 3’

|

59 |

| Murine IL23 |

Forward: 5’ ACCAGCGGGACATATGAATCT 3’

Reverse: 5’ AGACCTTGGCGGATCCTTTG 3’

|

59 |

| Murine inducible NO-synthase |

Forward: 5’ GCTCCCTATCTTGAAGCCCC 3’

Reverse: 5’ TGGAAGCCACTGACACTTCG 3’

|

58 |

| Murine IL10 |

Forward: 5’ GTAGAAGTGATGCCCCAGGC 3’

Reverse: 5’ GACACCTTGGTCTTGGAGCTTATT 3’

|

60 |

| Murine Arginase 1 |

Forward: 5’ TTTCTCAAAAGGACAGCCTCG 3’

Reverse: 5’ CAGACCGTGGGTTCTTCACA 3’

|

58 |

| Murine IL4 |

Forward: 5’ TCACAGCAACGAAGAACACCA 3’

Reverse: 5’ CAGGCATCGAAAAGCCCGAA 3’

|

58 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).