Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Design and Reporting

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

- Concept A (cancer):(cancer* OR neoplasm* OR oncolog*)

- Concept B (NLP/SA):("natural language processing" OR "text mining" OR sentiment OR emotion* OR classifier* OR lexicon* OR transformer*)

- Concept C (patient voice/platforms):("social media" OR Twitter OR Reddit OR forum* OR blog* OR "patient review" OR "free text")

- Concept D (adherence/concordance):(adheren* OR nonadheren* OR concordan* OR complian* OR persistence OR discontinu* OR "shared decision*")

Automation sensitivity.

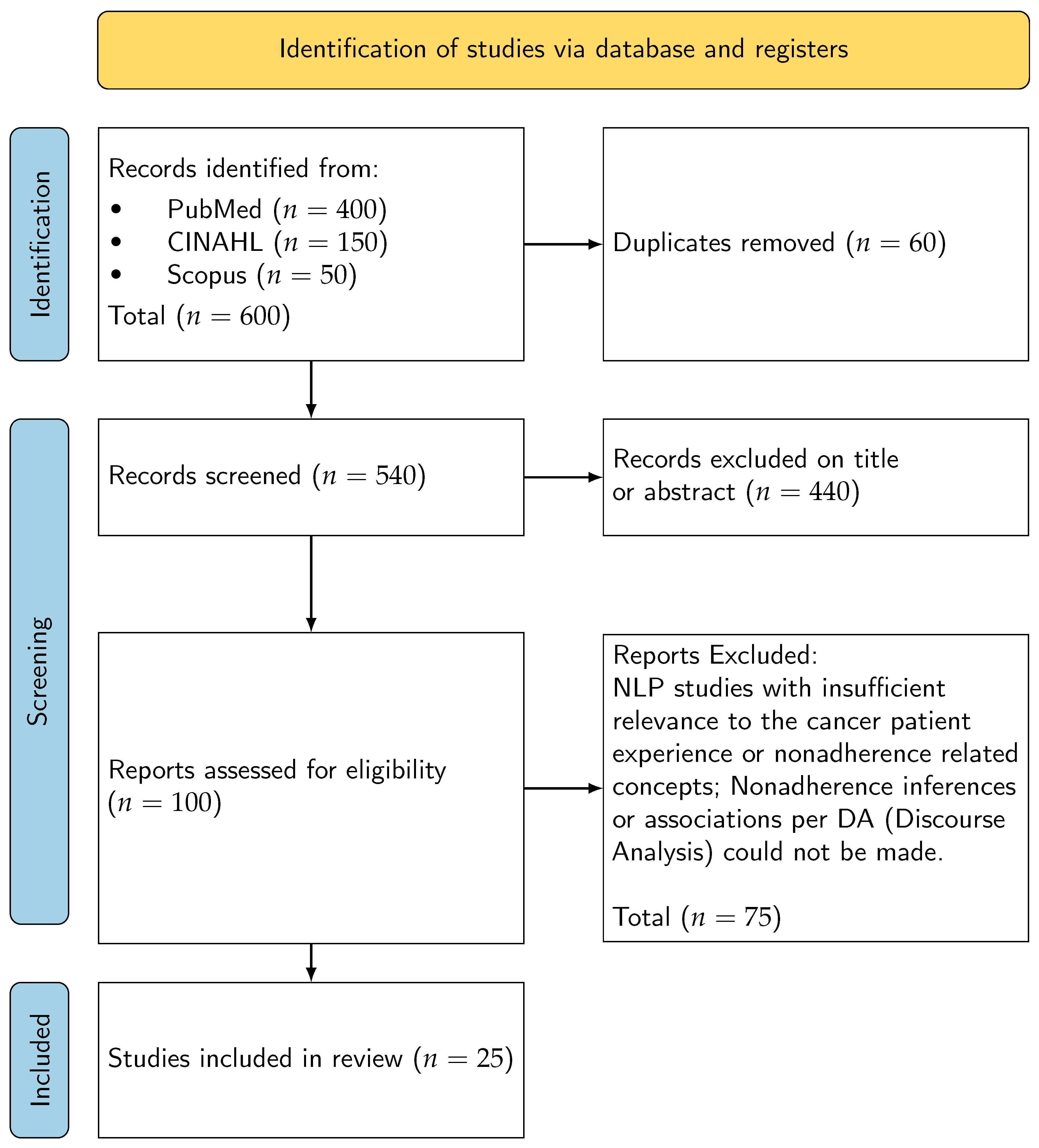

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Charting

2.6. Critical Appraisal

2.7. Ethical Considerations for Online Patient Generated Data

2.8. Synthesis Approach

2.9. Synthesis Without Meta Analysis (SWiM)

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Overview

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

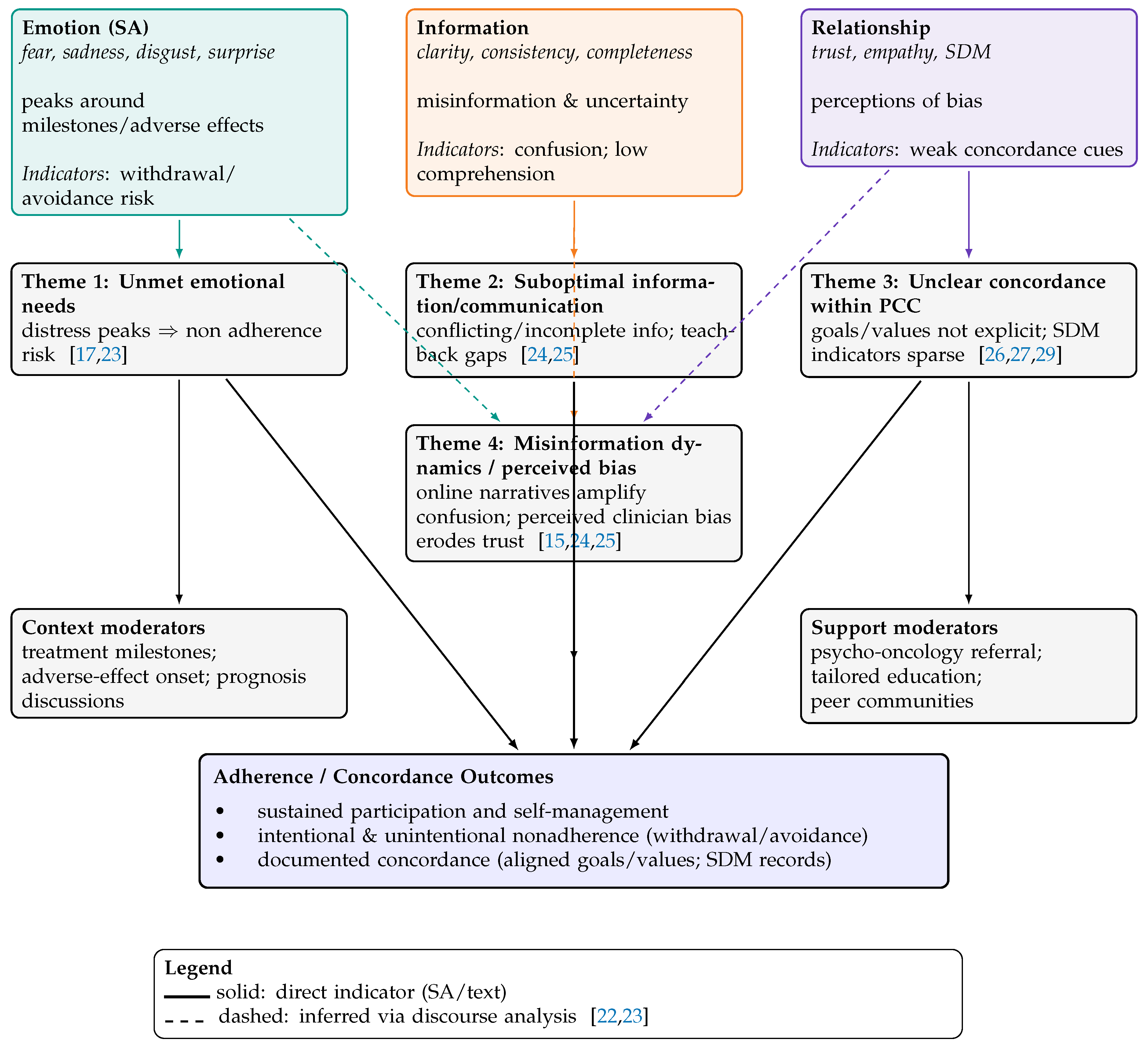

3.3. Emergent Patient-Side Themes

- Unmet Emotional Needs: Emotions such as fear, sadness, disgust, and surprise peaked around treatment milestones and adverse effects, often correlating with withdrawal or intentional nonadherence.

- Suboptimal Information and Communication: Conflicting or incomplete information, including misleading framings (e.g., “good cancer”), contributed to confusion and reduced trust in care teams.

- Unclear Concordance within Person-Centred Care (PCC): Patient narratives often lacked explicit indicators of shared decision-making (SDM) or goal alignment, suggesting missed opportunities for concordance checks.

- Online Misinformation Dynamics and Perceived Clinician Bias: Online narratives amplified confusion and sometimes reflected perceived bias, further eroding trust and complicating adherence.

3.4. Theme Prevalence Across Studies

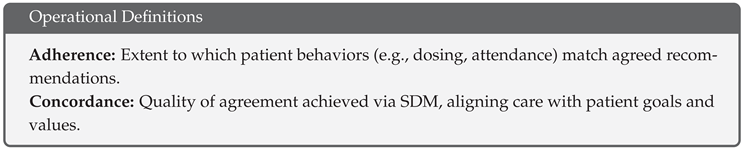

3.5. Operational Definitions of Adherence and Concordance

3.6. Emotion–Behavior–Response Framework

3.7. Narrative Summary

4. Discussion

4.1. Linking Findings to Review Questions

4.2. Conceptual Contributions

4.3. Platform and Methodological Insights

4.4. Appraisal Informed Interpretation

4.5. Implications for Practice

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belcher; S. M. Mackler; E. Muluneh; B. Ginex; P. K. Anderson; M. K. Bettencourt; E. DasGupta; R. K. Elliott; J. Hall; E. Karlin; M. Kostoff; D. Marshall; V. K. Millisor; V. E. Molnar; M. Schneider; S. M. Tipton; J. Yackzan; S. LeFebvre; K. B. Sivakumaran; K.;Waseem; H. ONS Guidelines™ to Support Patient Adherence to Oral Anticancer Medications. Oncology Nursing Forum 2022, 49(4), 279–295. [CrossRef]

- Sabaté, W. H. O. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. World Health Organization, Switzerland 2003, 198. Available online: https://www.google.com.au/books/edition/Adherence_to_Long_term_Therapies/kcYUTH8rPiwC?hl=en&gbpv=0.

- Brown, M. T.; Bussell, J. K. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc 2011, 86(4), 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wreyford; L. Gururajan; R.; Zhou; X. When can cancer patient treatment nonadherence be considered intentional or unintentional? A scoping review. Unknown Journal 2023, 18(5), e0282180. [CrossRef]

- Chung; E. H. Mebane; S. Harris; B. S. White; E.; Acharya; K. S. Oncofertility research pitfall? Recall bias in young adult cancer survivors. F S Rep 2023, 4(1), 98–103. [CrossRef]

- Felipe; D. David; E. Mario; M.; Qiao; W. Bias in patient satisfaction surveys: a threat to measuring healthcare quality. BMJ Global Health 2018, 3(2), e000694. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindberg; P. Netter; P. Koller; M. Steinger; B.; Klinkhammer-Schalke; M. Breast cancer survivors’ recollection of their quality of life: Identifying determinants of recall bias in a longitudinal population-based trial. PLoS One 2017, 12(2), e0171519. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A. M.; Yan, X.; Tariq, S.; Ali, M. What patients like or dislike in physicians: Analyzing drivers of patient satisfaction and dissatisfaction using a digital topic modeling approach. Information Processing & Management 2021, 58(3), 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawab; K. Ramsey; G.; Schreiber; R. Natural Language Processing to Extract Meaningful Information from Patient Experience Feedback. Appl Clin Inform 2020, 11(2), 242–252. [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.; Luk, B. Patient satisfaction: Concept analysis in the healthcare context. Patient education and counseling 2019, 102(4), 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasala, R.; Santoleri, F. Association between adherence to oral therapies in cancer patients and clinical outcome: A systematic review of the literature. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2022, 88(5), 1999–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoder; A. K. Dong; E. Yu; X. Echeverria; A. Sharma; S. Montealegre; J.; Ludwig; M. S. Effect of Quality of Life on Radiation Adherence for Patients With Cervical Cancer in an Urban Safety Net Health System. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics 2023, 116(1), 182–190. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.; Jones, T.; Alapati, A.; Ukandu, D.; Danforth, D.; Dodds, D. A Sentiment Analysis of Breast Cancer Treatment Experiences and Healthcare Perceptions Across Twitter. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.09959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpen, T.; Matthews, L.; Matthews, S. G.; Guney, E. Beneath the surface of talking about physicians: A statistical model of language for patient experience comments. Patient Experience Journal 2019, 6(1), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai; Rayson; P. Payne; S.; Liu; Y. Analysing Emotions in Cancer Narratives: A Corpus-Driven Approach. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Patient-Oriented Language Processing (CL4Health) @ LREC-COLING 2024, Torino, Italia, 2024; pp. 73–83.

- Mishra, M. V.; Bennett, M.; Vincent, A.; Lee, O. T.; Lallas, C. D.; Trabulsi, E. J.; Gomella, L. G.; Dicker, A. P.; Showalter, T. N. Identifying barriers to patient acceptance of active surveillance: content analysis of online patient communications. PLOS ONE 2013, 8(9), e68563. [CrossRef]

- Yin; Z. Malin; B. Warner; J. Hsueh; P.; Chen; C. The Power of the Patient Voice: Learning Indicators of Treatment Adherence From An Online Breast Cancer Forum. Eleventh International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Babel; R. Taneja; R. Mondello; M. Monaco; A.; Donde; S. Artificial Intelligence Solutions to Increase Medication Adherence in Patients With Non-communicable Diseases [Review]., Volume 3 - 2021. Frontiers in Digital Health 2021, 3. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.; Vicha, E. Twitter Sentiment at the Hospital and Patient Level as a Measure of Pediatric Patient Experience. Open Journal of Pediatrics 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim; J. A. Huang; X. Horan; M. R. Baker; J. N.; Huang; I. C. Using natural language processing to analyze unstructured patient-reported outcomes data derived from electronic health records for cancer populations: a systematic review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2024, 24(4), 467–475. [CrossRef]

- Babel; R. Taneja; R. Mondello; M. Monaco; A.; Donde; S. Artificial Intelligence Solutions to Increase Medication Adherence in Patients With Non-communicable Diseases [Review]. Frontiers in Digital Health 2021, 3. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Fu, J.; Lai, J.; Sun, L.; Zhou, C.; Li, W.; Jian, B.; Deng, S.; Zhang, Y; Guo, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, S.; Hou, M.; Wang, R; Chen, Q.; Wu, Y. Construction of an Emotional Lexicon of Patients with Breast Cancer: Development and Sentiment Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2023, 25, e44897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chichua, M.; Filipponi, C.; Mazzoni, D.; Pravettoni, G. The emotional side of taking part in a cancer clinical trial. PLOS ONE 2023, 18(4), e0284268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, R. A.; Viswanath, K.; Vaz-Luis, I.; Keating, N. L. Learning from social media: utilizing advanced data extraction techniques to understand barriers to breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2016, 158(2), 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verberne, S.; Batenburg, A.; Sanders, R.; van Eenbergen, M.; Das, E.; Lambooij, M. S. Analyzing Empowerment Processes Among Cancer Patients in an Online Community: A Text Mining Approach. JMIR Cancer 2019, 5(1), e9887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene; S. M. Tuzzio; L.; Cherkin; D. A framework for making patient-centered care front and center. Perm J 2012, 16(3), 49–53. [CrossRef]

- Robinson; J. H. Callister; L. C. Berry; J. A.; Dearing; K. A. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008, 20(12), 600–607. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fix; G. M. VanDeusen Lukas; C. Bolton; R. E. Hill; J. N. Mueller; N. LaVela; S. L.; Bokhour; B. G. Patient-centred care is a way of doing things: How healthcare employees conceptualize patient-centred care. Health Expect 2018, 21(1), 300–307. [CrossRef]

- Mead, H.; Wang, Y.; Cleary, S.; Arem, H.; Pratt-Chapman, L. M. Defining a patient-centered approach to cancer survivorship care: development of the patient centered survivorship care index (PC-SCI). BMC Health Services Research 2021, 21(1), 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights (Second Edition). Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2020. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/australian-charter-healthcare-rights-second-edition-a4-accessible.

- Moralejo, D.; Ogunremi, T.; Dunn, K. Critical Appraisal Toolkit (CAT) for assessing multiple types of evidence. Can Commun Dis Rep 2017, 43(9), 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeat, J.; Roddam, H. The qual-CAT: Applying a rapid review approach to qualitative research to support clinical decision-making in speech-language pathology practice. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention 2019, 13(1-2), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASP. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; CASP UK - OAP Ltd, 2023; Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Cho, J. E.; Tang, N.; Pitaro, N.; Bai, H.; Cooke, P. V.; Arvind, V. Sentiment Analysis of Online Patient-Written Reviews of Vascular Surgeons. Ann Vasc Surg 2023, 88, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, M.; Spada, G. E.; Fragale, E.; Pezzolato, M.; Munzone, E.; Sanchini, V.; Pietrobon, R.; Teixeira, L.; Valencia, M.; Machiavelli, A.; Woloski, R.; Marzorati, C.; Pravettoni, G. Adherence to oral anticancer treatments: network and sentiment analysis exploring perceived internal and external determinants in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer 2024, 32(7), 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ure, C.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, C.; Liu, J.; Zhou, C.; Jian, B.; Sun, L.; Li, W.; Xie, L.; Mai, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; Lai, J.; Fu, J.; Wu, Y. Listening to voices from multiple sources: A qualitative text analysis of the emotional experiences of women living with breast cancer in China. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11, 1114139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meksawasdichai, S.; Lerksuthirat, T.; Ongphiphadhanakul, B.; Sriphrapradang, C. Perspectives and Experiences of Patients with Thyroid Cancer at a Global Level: Retrospective Descriptive Study of Twitter Data. JMIR Cancer 2023, 9, e48786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podina, I. R.; Bucur, A.-M.; Todea, D.; Fodor, L.; Luca, A.; Dinu, L. P.; Boian, R. F. Mental health at different stages of cancer survival: a natural language processing study of Reddit posts. Frontiers in Psychology 2023, 14, 1150227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, M.; Piperis, M.; Aasaithambi, S.; Chauhan, J.; Sagkriotis, A.; Vieira, C. Social Media Listening to Understand the Lived Experience of Individuals in Europe With Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Systematic Search and Content Analysis Study. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12, 863641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Yada, S.; Aramaki, E.; Yajima, H.; Kizaki, H.; Hori, S. Extracting Multiple Worries From Breast Cancer Patient Blogs Using Multilabel Classification With the Natural Language Processing Model Bidirectional Encoder Representations From Transformers: Infodemiology Study of Blogs. JMIR Cancer 2022, 8(2), e37840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cercato, M. C.; Colella, E.; Fabi, A.; Bertazzi, I.; Giardina, B. G.; Di Ridolfi, P.; Mondati, M.; Petitti, P.; Bigiarini, L.; Scarinci, V; Franceschini, A.; Servoli, F.; Terrenato, I.; Cognetti, F.; Sanguineti, G.; Cenci, C. Narrative medicine: feasibility of a digital narrative diary application in oncology. Journal of International Medical Research 2021, 50(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K.; Turpeinen, S.; Kvist, T.; Ryden-Kortelainen, M.; Nelimarkka, S.; Enshaeifar, S.; Faithfull, S. Experience of Ambulatory Cancer Care: Understanding Patients’ Perspectives of Quality Using Sentiment Analysis. Cancer Nursing 2021, 44(6), E331–E338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, E. H.; Auil, M. J.; Spears, P. A.; Berg, K.; Winnette, R. Voice Analysis of Cancer Experiences Among Patients With Breast Cancer: VOICE-BC. Journal of Patient Experience 2021, 8, 23743735211048058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerrapragada, G.; Siadimas, A.; Babaeian, A.; Sharma, V.; O’Neill, T. J. Machine Learning to Predict Tamoxifen Nonadherence Among US Commercially Insured Patients With Metastatic Breast Cancer. JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics 2021, 5, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraliyage, H.; De Silva, D.; Ranasinghe, W.; Adikari, A.; Alahakoon, D.; Prasad, R.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Bolton, D. Cancer in Lockdown: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Patients With Cancer. The Oncologist 2021, 26(2), e342–e344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, A.; Idicula, S. M.; Jones, J. Deep learning-based analysis of sentiment dynamics in online cancer community forums: An experience. Health Informatics Journal 2021, 27(2), 14604582211007537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A. M.; Yan, X.; Tariq, S.; Ali, M. What patients like or dislike in physicians: Analysing drivers of patient satisfaction and dissatisfaction using a digital modelling approach. Information Processing & Management 2021, 58(3), 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditi, C.; Walther, D.; Gilles, I.; Lesage, S.; Griesser, A.-C.; Bienvenu, C.; Eicher, M.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I. Computer-assisted textual analysis of free-text comments in the Swiss Cancer Patient Experiences (SCAPE) survey. BMC Health Services Research 2020, 20, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adikari, A.; Ranasinghe, W.; de Silva, D.; Alahakoon, D.; Prasad, R.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Bolton, D. Can online support groups address psychological morbidity of cancer patients? An AI-based investigation of prostate cancer trajectories. PloS one 2020, 15(3), e0229361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikal, J.; Hurst, S.; Conway, M. Codifying Online Social Support for Breast Cancer Patients: Retrospective Qualitative Assessment. J Med Internet Res 2019, 21(10), e12880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbers, L.A.; Minot, J.R.; Gramling, R.; Brophy, M.T.; Do, N.V. Sentiment analysis of medical record notes for lung cancer patients at the Department of Veterans Affairs. PLOS ONE 2023, 18(1), e0280931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M. R.; Friese, C. R.; Mendelsohn-Victor, K.; et al. Clinician Perspectives on Electronic Health Records, Communication, and Patient Safety Across Diverse Medical Oncology Practices. J Oncol Pract 2019, 15(6), e529–e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author & Title | Method | Data Sources | Sample | Results | NLP Technique | Nonadherence/ Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clark et al., 2018. [13] A Sentiment Analysis of Breast Cancer Treatment Experiences and Healthcare Perceptions Across Twitter |

Quantitative | ∼5.3 million “breast cancer” related tweets. CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium |

Invisible patient-reported outcomes (iPROs) captured; positive experiences shared; fear of legislation causing loss of coverage. | Supervised machine learning combined with NLP | US context: fear of not receiving care salient; analogous issues elsewhere may include lack of insurance and long waiting periods. | |

| Turpen et al., 2019. [14] Beneath the surface of talking about Physicians: A statistical model of language for patient experience comments |

Analysis of patient comments from surveys | Anonymous patient satisfaction surveys | 25,161 surveys. CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium |

Statistically significant differences in language used for higher- vs lower-rated physicians. | Frequency of 300 pre-selected n-grams | Time spent with patients matters; longer physician times can enhance treatment adherence. |

| Mishra et al., 2013. [16] Identifying barriers to patient acceptance of active surveillance: Content analysis of online patient communications |

Qualitative | Online conversations (prostate cancer patients) | 34 websites; 3,499 online conversations. CAT: Strength = Weak; Quality = Low |

Patients often believed specialist information was biased. | NLP to identify content & sentiment; ML; internal data dictionary | Perceived physician bias undermines trust and concordance; may influence treatment nonadherence; “suspicion of bias” emerged as a new theme. |

| Yin et al., 2017. [17] The Power of the Patient Voice: Learning Indicators of Treatment Adherence from an Online Breast Cancer Forum |

Quantitative | Breastcancer.org | Retrospective study of 130,000 posts from 10,000 patients over 9 years. CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium |

Results correlated with traditional adherence surveys; emotions/personality readily detected online; scale increases relevance. | Logistic Regression (ML); emotion analysis | Treatment completion associated with joy (and some disgust/sadness); fear, especially of side effects, persistent and sometimes overlooked. |

| Li J et al., 2023. [22] Construction of an Emotional Lexicon of Patients with Breast Cancer: Development and Sentiment Analysis |

Qualitative | Weibo (Chinese social media platform) | 150 written materials; 17 interviews; 6,689 posts/comments. CAT: Strength = Weak; Quality = Low |

Emotional lexicon with fine-grained categories; new perspective for recognizing emotions/needs; enables tailored emotional management plans. | Emotional lexicon; manual annotation (two general lexicons + BC-specific) | Emotional expressions may predict adherence; effective emotional management may be as important as information; without support, intentional nonadherence influenced by poor provider relationships. |

| Chichua et al., 2023. [23] The emotional side of taking part in a cancer clinical trial |

Quantitative | Public posts re: clinical trials; Reddit communities | 129 cancer patients; 112 caregivers. CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium |

Fear identified as the highest emotion. | Keywords; NRC Emotion Lexicon; sentiment analysis | Sharing emotional experiences may increase fear of treatment withdrawal; trust in the physician is an important factor (potential barrier) in clinical trials. |

| Freedman et al., 2016. [24] Learning from social media: utilizing advanced data extraction techniques to understand barriers to breast cancer treatment |

Qualitative | Message boards; blogs; topical sites; content-sharing sites; social networks | 1,024,041 social media posts about breast cancer treatment. CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium |

Fear was the most common emotional sentiment expressed. | Machine Learning (ConsumerSphere software) | Fear of side effects dominant; links to poor physician relationships and lack of treatment concordance; rudeness a factor in poor communication. |

| Verberne et al., 2019. [25] Analysing empowerment Processes Among Cancer Patients in an Online Community: A Text Mining Approach |

Posts labelled for empowerment and psychological processes | Forum for cancer patients and relatives | 5,534 messages in 1,708 threads by 2,071 users. CAT: Strength = Weak; Quality = Medium |

The need for informational support exceeded emotional support. | LIWC | Lack of information may result in unintentional treatment nonadherence. |

| Author & Title | Method | Data Sources | Sample | Results | NLP Technique | Nonadherence/ Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cho et al., 2023. [35] Sentiment Analysis of Online Patient-Written Reviews of Vascular Surgeons | Quantitative (sentiment analysis and machine learning) | SVS member directory cross-referenced with a patient–physician review website | 1,799 vascular surgeons.CAT: Strength = Weak; Quality = Medium | The positivity/negativity of reviews largely related to words associated with the patient–doctor experience and pain. | Word-frequency assessments; multivariable analyses | Physician communication is a key factor influencing patient dissatisfaction and potentially nonadherence. |

| Masiero et al., 2024. [36] Adherence to oral anticancer treatments: network and sentiment analysis exploring perceived internal and external determinants in patients with metastatic breast cancer | Qualitative | Division of Senology, European Institute of Oncology | 19 female metastatic breast cancer patients.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium | Themes: individual clinical pathway; barriers to adherence; resources to adherence; perception of new technologies. | Word-cloud plots; network analysis; sentiment analysis | Patients experience fear related to clinical values; ineffective communication; discontinuity of patient care. |

| Li C et al., 2023. [37] Listening to voices from multiple sources: A qualitative text analysis of the emotional experiences of women living with breast cancer in China | Qualitative | (1) Six tertiary hospitals (expressive writing);(2) Semi-structured interviews;(3) Weibo | 5,675 Weibo posts.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium | Breast cancer patients require benefit finding and cognitive re-appraisal with strong social support; patients require screening for emotional support. | Python web crawler (Weibo posts/comments) | Emotional distress is an unmet need; healthcare professionals should provide multiple support channels; peer support may alleviate distress. |

| Meksawasdichai et al., 2023. [38] Perspectives and Experiences of Patients with Thyroid Cancer at a Global Level: Retrospective Descriptive Study of Twitter Data | Quantitative | Retrospective tweets relevant to thyroid cancer | 13,135 tweets.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Low | Twitter may provide an opportunity to improve patient–physician engagement or serve as a research data source. | Twitter scraping; sentiment analysis | Support in self-management is a main topic; physicians may need to recommend online resources; lack of support may lead to unintentional nonadherence. |

| Podina et al., 2023. [39] Mental Health at Different Stages of Cancer Survival: A Natural Language Processing Study of Reddit Posts | Mixed methods | 187 users; 72,524 posts.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium | Short-term survivors are more likely to suffer depression than long-term; support in daily needs is lacking. | Lexicon and machine learning | Need for online social media support; patients do not typically discuss aspects of their disease with health professionals; lack of trust and concordance influence treatment nonadherence. | |

| Manuelita Mazza et al., 2022. [40] Social media Listening to Understand the Lived Experience of Individuals in Europe with Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Systematic Search and Content Analysis Study | Non-interventional retrospective analysis of public social media | Social media posts (Twitter; patient forums) | 76,456 conversations during 2018–2020.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium | Twitter was the most common platform; 61% authored by patients, 15% by friends/family, 14% by caregivers. | Predefined search string; content analysis | Poor communication and suboptimal relationships may influence treatment nonadherence. |

| Watanabe et al., 2022. [41] Extracting Multiple Worries from Breast Cancer Patient Blogs: Infodemiology Study of Blogs | Quantitative | Blog posts by patients with breast cancer in Japan | 2,272 blog posts.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium | Results helpful to identify worries and give timely social support. | BERT (context-aware NLP) | Concerns of patients change over time; a potential physician factor that may influence treatment nonadherence. |

| Cercato et al., 2021. [42] Narrative Medicine: feasibility of a digital narrative diary application in oncology | Qualitative (focus groups; thematic qualitative analysis) | National Cancer Institute (Rome) | 31 cancer patients.CAT: Strength = Weak; Quality = Medium | Digital narrative medicine could improve oncologist relationship with greater patient input. | Narrative prompts for patients | Lack of patient-centred care; therapeutic alliance will promote adherence and improve treatment concordance; neglect could result in unintentional nonadherence. |

| Author & Title | Method | Data Sources | Sample | Results | NLP Technique | Nonadherence/ Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehviläinen-Julkunen et al., 2021. [43] Experience of Ambulatory Cancer Care. Understanding Patients’ Perspectives of Quality Using Sentiment Analysis | Mixed methods qualitative analysis (survey sentiment + focus groups) | National Cancer Patient Survey data; focus groups | 92 participants (>65 years avg) and 7 focus groups (31 patients).CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium | NLP automated sentiment analysis supported with focus groups informed the initial thematic analysis. | Automated sentiment analysis algorithm + focus groups | Communication is vital to quality of care (and in enhancing treatment adherence); not actively soliciting patient feedback could result in nonadherence. |

| Law et al., 2021. [44] Voice Analysis of Cancer Experiences among Patients with Breast Cancer: VOICE BC | Observational (voice/text analysis) | Online breast cancer forums | ∼15,000 posts; 3,906 unique users.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium | Engagement scores ranked relationships with HCPs as high; information needs are extremely high. | Lexicon-based analysis | Lack of information may result in unintentional treatment nonadherence; emotional needs may be of greater concern than informational needs. |

| Yerrapragada et al., 2021. [45] Machine Learning to Predict Tamoxifen Nonadherence among US Commercially Insured Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer | Machine learning (insurance claims; population-based) | Commercial claims & encounters; Medicare claims | 3,022 breast cancer patients.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = High | 48% of patients were tamoxifen nonadherent. | Algorithms trained to predict nonadherence from claims features | High rates of nonadherence confirmed via ML; results correlate with traditional surveys. |

| Moraliyage et al., 2021. [46] Cancer in Lockdown: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Patients with Cancer | Mixed methods (Quant ML / Qual NLP) | Online support groups; Twitter | 2,469,822 tweets and 21,800 patient discussions.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium | Cancer patient information needs, expectations, mental health, and emotional wellbeing states can be extracted. | PRIME on Twitter; machine learning algorithms | Fear underestimated in traditional surveys; may give rise to unintentional treatment nonadherence. |

| Balakrishnan, 2021. [47] Deep learning-based analysis of sentiment dynamics in online cancer community forums | Quantitative | Breastcancer.org (3 OHS forums) | 150,000 posts.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium | Deep learning more effective than machine learning. | Co-training: word embedding & sentiment embedding; domain-dependent lexicon | Patients need current information; emotions highest during the treatment phase; information needs change along the disease trajectory. |

| Shah et al., 2021. [48] What Patients like or dislike in physicians: Analysing drivers of patient satisfaction and dissatisfaction using a digital modelling approach | Quantitative | National Health Service subsidiary website | 53,724 online reviews of 3,372 doctors.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium | Unstructured text mining identified key topics of satisfaction and dissatisfaction. | Sentic-LDA topic model; text mining | Functional quality (communication; waiting times) may outweigh empathy; attitude & communication dominate dissatisfaction. |

| Arditi et al., 2020. [49] Computer-Assisted Textual Analysis of free-text comments in the Swiss Cancer Patient Experiences (SCAPE) survey | Cross-sectional survey (free-text comments) | Swiss Cancer Patients survey | 844 patient comments.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium | Free text allows patients greater expression “in their own words”; enhances patient-centred care. | Computer-assisted textual analysis; manual expert corpus formatting | Poor communication and lack of information most common; loneliness emerges as hidden factor—unmet support need. |

| Author & Title | Method | Data Sources | Sample | Results | NLP Technique | Nonadherence/ Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adikari et al., 2020. [50] Can online support groups address psychological morbidity of cancer patients? An AI-based investigation of prostate cancer trajectories | Quantitative / Qualitative | Conversations in ten international OCSGs | 18,496 patients; 277,805 conversations.CAT: Strength=Moderate; Quality = Medium | Patients joining pre-treatment had improved emotions; long-term participation increased wellbeing; lower negative emotions after 12 months vs post-treatment. | Validated AI techniques and NLP framework | Most patients sought treatment information initially; transitioned to emotional support over time. |

| Mikal et al., 2019. [51] Codifying Online Social Support for Breast Cancer Patients: Retrospective Qualitative Assessment | Qualitative | 30 breast cancer survivors; ∼100,000 lines of data.CAT: Strength = Weak; Quality = Medium | Coding schema identified social support exchange at diagnosis and transition off therapy; social media support buffers stress. | Systematic coding (retrospective) | Emotional support prioritized over informational support; greater focus on emotional support may enhance adherence. |

| Theme | % of selected sources |

|---|---|

| Unmet emotional needs (distress, fear, sadness, disgust, surprise) [15,17,23,24] | 41% |

| Suboptimal information and communication (conflicting/insufficient info; perceived bias) [21,24,25] | 50% |

| Concordance within PCC unclear (goal alignment, shared decision making indicators limited) [26,27,29] | 55% |

| Online misinformation dynamics / perceived clinician bias [24,25,38] | (subset; qualitatively frequent) |

| Emotion signal | Likely behavior | Concordance oriented response |

|---|---|---|

| Fear/ anxiety | Delay, dose skipping | SDM Team talk: acknowledge fear; distress screen; Option talk: clarify risks; Decision talk: values clarification. |

| Sadness/ hopelessness | Withdrawal from self care | Psycho-oncology referral; follow up within 72 h; problem solving supports. |

| Disgust (AEs) | Refusal/cessation | AE management options; normalize toxicity; reframe goals. |

| Confusion/ surprise | Inconsistent adherence | Teach back; simplified plan; bilingual materials. |

| Positive emotions | Sustained engagement | Reinforce self efficacy; document concordance; milestone planning. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).