Introduction

Bioethics is defined as the systematic study of the moral dimensions of life sciences and healthcare. This definition acknowledges the inherent moral nature of actions, behaviours, and health policies [

1].

The life experience of patients with advanced cancer and limited survival expectancy is unique and profoundly complex. Symptomatic burden, functional decline, emotional impact, family support, social environment, spirituality, moral values, life history, cultural context, and the conditions of the patient's care setting significantly influence the coping strategy for the end-of-life process [

2,

3,

4,

5]. It is a complex process because it depends on the continuous and non-linear interaction of multiple multidimensional variables, maintaining a frequently unstable balance with not always predictable outcomes [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

In the complex end-of-life scenario, the patient, family, and healthcare professionals actively participate in the decision-making process. The healthcare professional provides objective information about the disease and its treatment, based on scientific evidence. However, each patient assigns a unique and subjective value and meaning to their illness. This dynamic and inter-subjective process often leads to moral discrepancies among the various individuals involved in decision-making.

Ethical reflection emerges when the commonly accepted codes, rules, or habits guiding the decision-making process become uncertain. The widely accepted ethical principles of beneficence, autonomy, justice, and non-maleficence govern the actions of healthcare professionals [

14]. Ethical issues arise when, in a specific situation, one of these principles is violated, conflicts with another, or is interpreted differently by the various individuals involved.

Published studies focus on the narrative description of ethical issues in the end-of-life process from a theoretical perspective or detail, through surveys, the most common ethical concerns among professionals [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. However, the literature provides very little data on the prevalence of ethical issues in the end-of-life process in real clinical practice. In 2021, our group published the only prospective study on the prevalence of ethical dilemmas in the end-of-life process of patients with advanced cancer. This study, based on a systematic multidimensional evaluation of all patients included in the prospective cohort for the development of the PALCOM scale for complexity of palliative care needs, identified a prevalence of ethical issues of 27.8% [

13].

The PALCOM scale is a multidimensional assessment tool designed to measure the complexity of palliative needs in patients with advanced cancer. This scale comprises five assessment domains, including the identification of ethical or existential issues. In 2018, our group published a prospective cohort study that led to the creation and development of the PALCOM scale (development cohort) [

9]. In 2021, we published the aforementioned secondary analysis on the prevalence of ethical issues, based exclusively on the development cohort [

13]. In 2023 and 2024, we published two validation studies that used the same inclusion criteria and assessment system (validation cohort) [

10,

11]. At this time, we believe that conducting a pooled analysis of data from the development and validation cohorts of the PALCOM scale is timely and will help reinforce the consistency of prevalence data on ethical issues. The objective of this study is to determine the overall and specific prevalence of different ethical issues observed in the end-of-life process in patients with advanced cancer. Our hypothesis is that the prevalence of ethical issues is high, that there are no significant differences between the values observed by different teams and in different study periods (development and validation cohorts), and that the overall prevalence decreases during follow-up, likely because early detection allows for specific intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis of the pooled data from the development and validation cohorts of the PALCOM scale, which measures the complexity of palliative needs in patients with advanced cancer. Both cohorts were prospective and multicentre, with a maximum follow-up of 6 months. They applied the same inclusion criteria and used the same methodology for both the assessment and the recording of variables.

2.1. Setting and Study Periods

The development cohort, aimed at constructing a model for complexity of palliative care needs (PALCOM scale), included patients from November 2012 to January 2013. The validation cohort, aimed at confirming the consistency and predictive value of the PALCOM scale, included patients from December 2020 to April 2021. Both studies involved multiple public healthcare centres across all levels of care in the Autonomous Community of Catalonia (Spain): primary care, hospitals, hospital and home palliative care (PC), and medium-long stay units. The development cohort included 24 healthcare centres (16 primary care, 3 hospitals, 3 home palliative care teams, and 2 medium-long stay centres). The validation cohort included 7 healthcare centres (1 primary care, 2 hospitals, 3 home PC teams, and 1 medium-long stay centre).

The results from the development and validation cohorts, along with a secondary analysis of the prevalence of ethical issues based solely on the development cohort, were published in 2018, 2023, and 2021, respectively [

9,

10,

11,

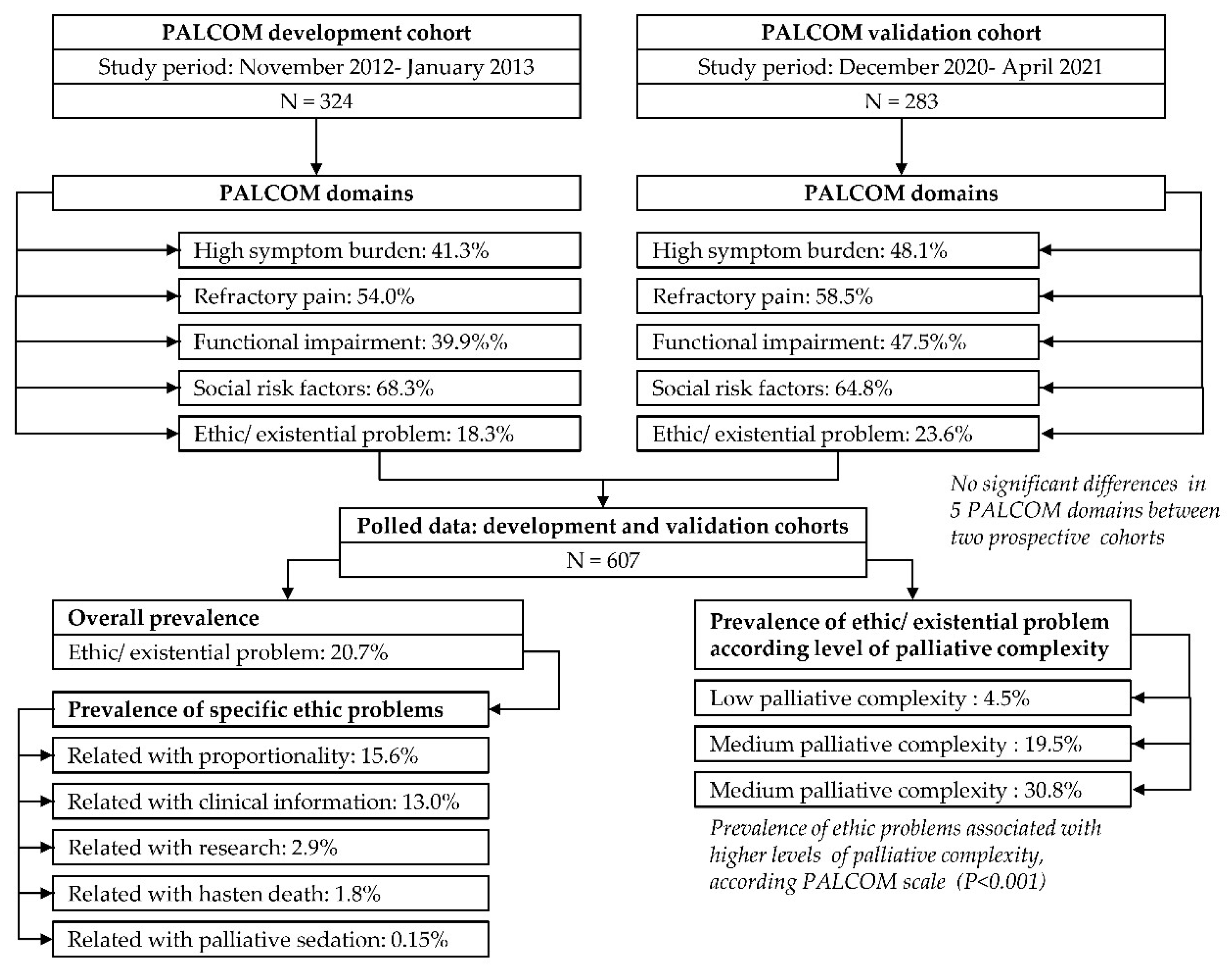

13]. Current study presents a secondary analysis of the prevalence of ethical issues using pooled data from both cohorts. The objectives are to increase sample size and consistency, compare results between the two cohorts, and analyze their evolution during follow-up (

Figure 1).

2.2. PALCOM Scale of Palliative Complexity

The PALCOM scale is a predictive tool for assessing complexity of palliative care needs, consisting of five multidimensional domains: (a) symptomatic burden; (b) refractory pain; (c) functional decline; (d) socio-family risk factors; and (e) ethical issues (

Table 1). Each domain is scored dichotomously, with 0 indicating absence and 1 indicating the presence of the corresponding variables [

9,

10,

11]. The final score is the sum of the values across all domains. Patients scoring 4-5 are classified as high complexity and require systematic, intensive intervention by multidisciplinary palliative care (PC) teams, whether shared with referring teams or not. Those scoring 2-3 are classified as medium complexity and need systematic intervention by multidisciplinary PC teams, at an intensity adjusted to their needs, whether shared with referring teams or not. Patients scoring 0-1 are classified as low complexity and generally do not require systematic intervention by multidisciplinary PC teams, except for occasional consultations.

2.3. Definition of Ethical Issues

The identification of ethical issues can depend on the individual interpretation of observers. Therefore, the research team agreed on the following operational definition for both cohorts: a discrepancy in shared decision-making in a specific situation where it is necessary to choose between opposing options, morally or existentially acceptable from the individual perspective of the different participants in the deliberation. The observed ethical issues were classified according to the sub-categories identified in the analysis of the fifth domain of the PALCOM scale in the development cohort [

9]:

a) Related to information; b) Related to the proportionality of therapeutic and supportive measures (discrepancies in proportionality among family members, between the patient/family and the care team, and among care team members); c) Related to research and clinical trials; d) Related to palliative sedation; e) Related to the desire to hasten death; f) Other unspecified issues.

2.4. Objectives

The main objective of this study was to determine the overall prevalence of ethical issues in patients with advanced cancer. The secondary objectives were: a) to identify the prevalence of different sub-categories of ethical issues; b) to compare the prevalence between the two cohorts and assess their consistency; c) to describe the evolution of these issues over the 6-month follow-up period of the study.

2.5. Inclusion Criteria

We proposed to consecutively include in the study all patients who met the following inclusion criteria: age ≥ 18 years, diagnosis of advanced cancer, clinically estimated life expectancy ≤ 6 months, and signed informed consent.

2.6. Main Outcome Variable

The main variable in this study was the prevalence of ethical issues in patients with end-of-life cancer at the baseline visit. The prevalence of ethical issues was evaluated both globally and broken down into the aforementioned sub-categories (information, proportionality, research, palliative sedation, miscellaneous) at the baseline visit and monthly during follow-up.

2.7. Descriptive Variables

The following descriptive and clinical variables were recorded and analyzed: age, gender, primary origin of the cancer, survival, place of death, level of palliative care complexity, and domains of the PALCOM scale: a) high symptom burden (≥5 symptoms of at least moderate intensity, in a systematic record of 10 symptoms based on the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale model [

24]); b) potentially refractory pain, according to the Edmonton Classification System for Cancer Pain [

25,

26,

27]; c) Karnofsky Performance Status; d) socio-familial risk factors.

2.8. Data Collection, Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

All study variables were recorded directly by the treating professional in an electronic data collection notebook, coded to ensure the confidentiality of participants’ personal data. No individuals outside the research project had access to the coded database.

In both cohorts, the sample size estimation was based on previous studies and the maximum recruitment capacity of the participating centres, considering that the variables had to be recorded under the conditions of their daily clinical practice. The prevalence of patients presenting ethical issues and the frequencies of sub-categories were evaluated both generally and stratified by the level of complexity of the PALCOM scale and by month of follow-up. The prevalence observed in the development and validation cohorts were compared, considering that they were conducted at different times and by different care teams. Categorical or dichotomous variables were analyzed using absolute and relative frequencies. Continuous variables were described by calculating the mean value and standard deviation (SD) with a 95% confidence interval. For the comparison of variables according to complexity levels, Fisher’s exact test and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test were used.

3. Results

A total of 607 patients were included in the pooled analysis, with 324 (53.4%) from the development cohort and 283 (46.6%) from the validation cohort. Monthly follow-up data were available only for the validation cohort, as this variable was not recorded in the development cohort.

In the pooled data, the mean age of the patients was 70 years (SD ±11), and 350 were men (57.7%). Three hundred fifty-five patients were included in the hospital (58.5%), and 255 (41.5%) in community health centres. The most common primary cancer origins were lung (23.1%), followed by colon (15.5%), prostate (7.6%), and breast (6.8%). Five hundred patients had metastatic disease (82.4%), and 107 had advanced loco-regional disease (17.6%). At the time of inclusion, 462 (76.1%) patients were undergoing cancer treatment. The most frequent symptoms were asthenia (93.6%), pain (80.7%), anorexia (78.9%), anxiety (69.5%), sadness (69.4%), and insomnia (60.6%). The frequencies of the five domains of the PALCOM scale were: a) high symptom burden 44.5%; b) potentially refractory pain 56.2%; c) Karnofsky Performance Status ≤60% 43.5%; d) socio-familial risk factors 66.7%; e) ethical issues 23.4%. Three hundred seventy-nine patients (62.4%) died before the end of the maximum follow-up period of 6 months. No significant differences were observed between the two cohorts in terms of symptom frequencies or the domains of the PALCOM scale (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

3.1. Prevalence of Ethical Issues

In the pooled data, 126 patients (20.7%) presented at least one ethical issue (59 from the development cohort and 67 from the validation cohort) (

Table 4). A total of 204 ethical issues were recorded (117 in the development cohort and 87 in the validation cohort). Therefore, the average number of ethical issues per patient was 1.6 (1.9 in the development cohort and 1.3 in the validation cohort). No significant differences were observed between the two cohorts.

In the pooled data, 79 patients (13.0%) presented issues related to information. This was slightly more frequent in the development cohort (15.7%) than in the validation cohort (10.0%), but the difference was not statistically significant. In the pooled data, 95 patients (15.6%) presented issues related to the proportionality of therapeutic or supportive measures, with no significant differences between the development cohort (16.7%) and the validation cohort (14.5%). The discrepancies in proportionality were: a) among different family members in 47 patients (7.7%); b) between the patient or their family and the healthcare team in 27 patients (4.4%); c) among different members of the healthcare team in 25 patients (4.1%). No significant differences were observed between the frequencies in the development and validation cohorts. In the pooled data, 18 patients (2.9%) presented issues related to research, with no significant differences between the development cohort (2.5%) and the validation cohort (3.5%). In the pooled data, 11 patients (1.8%) explicitly, consistently, and repeatedly expressed the desire to hasten death, with no significant differences between the development cohort (1.2%) and the validation cohort (2.4%).

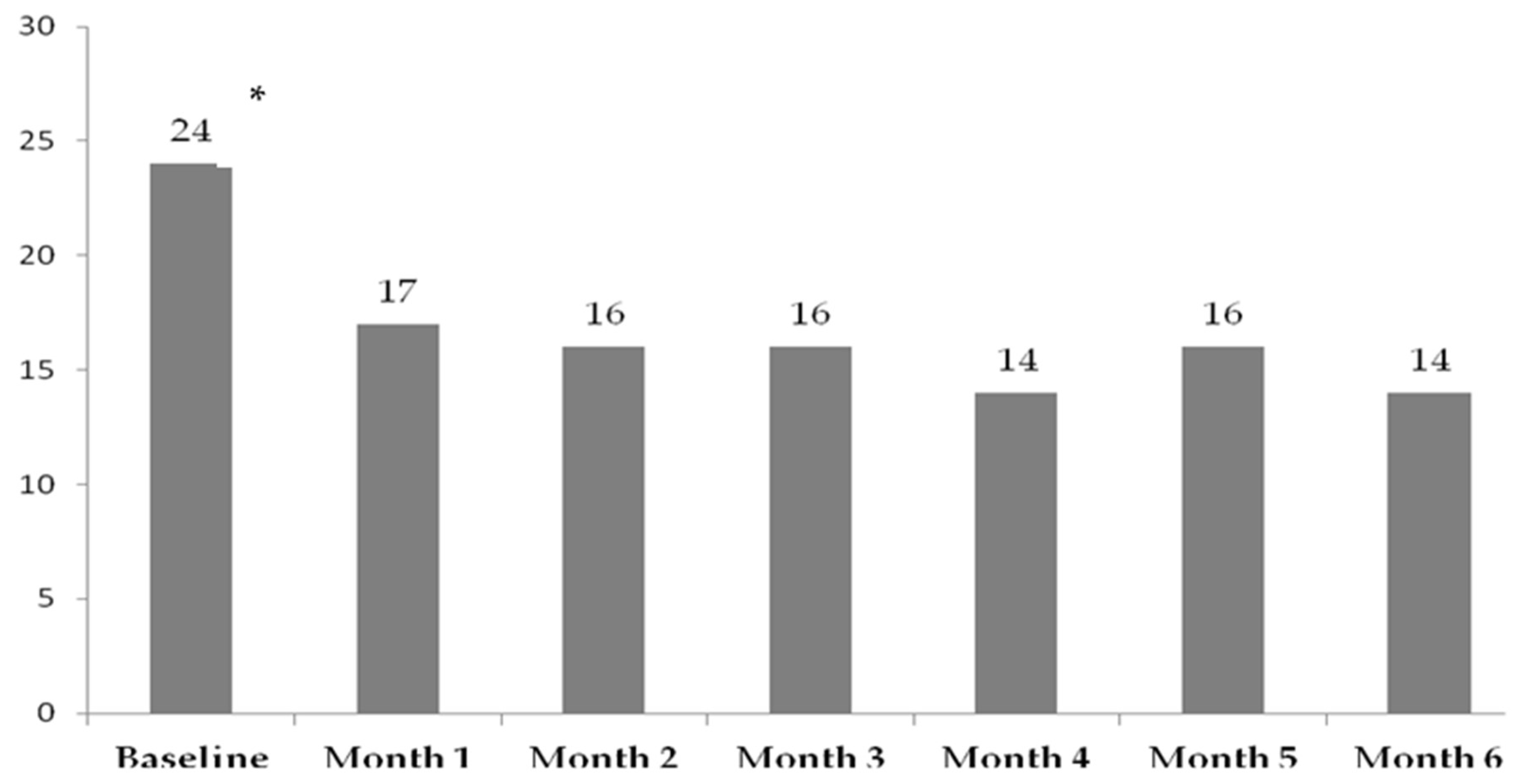

3.2. Evolution During Follow-Up

The monthly probability of presenting ethical issues during the 6-month follow-up was evaluable only in the validation cohort. A total of 67 patients (23.7%) presented ethical issues at the baseline visit. Among the patients who were alive in the first month of follow-up, 44 (17.1%) presented ethical issues, 32 (15.9%) in the second month, 25 (15.9%) in the third month, 18 (14.1%) in the fourth month, 18 (15.8%) in the fifth month, and 14 (14.4%) in the sixth month (

Figure 2). The probability of presenting ethical issues was significantly higher at the baseline visit (p<0.001), with no significant differences in this monthly probability from the first month of follow-up onwards.

3.3. Prevalence of Ethical Issues According to Palliative Complexity Level on the PALCOM Scale

The level of palliative complexity according to the PALCOM scale depends on the interaction of five assessment domains: symptom burden, potentially refractory pain, functional impairment, socio-familial risk, and ethical issues. The presence of 4-5 affected domains corresponds to high complexity cases, 2-3 to medium complexity, and 0-1 to low complexity.

In the aggregated data, 118 patients (19.5%) were classified as having low palliative complexity, 306 (50.5%) as medium, and 182 (30.0%) as high. Higher complexity levels are significantly associated with increased six-month mortality (low 43.2%, medium 62.7%, high 75.8%) (p<0.001) and a higher probability of in-hospital death (low 7.6%, medium 16.0%, high 28.6%) (p<0.001). The likelihood of presenting ethical issues, both in the aggregated data and when broken down between the two cohorts, is significantly higher at greater levels of palliative complexity according to the PALCOM scale (p<0.001): low 4.2%; medium 19.5%; and high 30.8% (

Table 3).

Discussion

We believe that the analysis of pooled data from the development and validation cohorts of the PALCOM scale is appropriate to expand the study sample and improve the consistency of the preliminary results published regarding the prevalence of ethical issues, which were initially based solely on the development cohort. The absence of significant differences in socio-demographic characteristics, the frequency of the five domains of the PALCOM scale, the identified levels of palliative complexity, and six-month mortality between both cohorts confirms the consistency of their combined analysis.

4.1. Overall Prevalence of Ethical Issues

In the polled data, 21% of patients presented at least one ethical issue according to the treating professionals. It is noteworthy that many of these patients simultaneously presented multiple ethical issues (an average of 1.6 ethical issues per patient). It is clear that ethical issues can cause significant discomfort for all parties involved in their discussion. The first step in addressing such a problem is its identification, and the second is to manage the conflict explicitly and respectfully. Conflict management skills can be essential for health professionals in resolving these issues. In fact, it is noteworthy that the prevalence of ethical issues in this study was significantly higher at the baseline visit compared to the prevalence observed during the subsequent six months of follow-up. These data suggest that early identification and intervention can reduce the frequency of ethical issues and, therefore, improve the outcomes of patient support measures. Overall, we consider these findings to be novel and relevant due to the high observed prevalence and the lack of previously published data in this area.

1.1. Prevalence of Different Categories of Ethical Issues

In this study, ethical issues were classified into five different categories: information, proportionality, research, palliative sedation, and the desire to hasten death. This classification was agreed upon by the research team of the development and validation cohorts of the PALCOM scale. It was based on multiple expert opinion publications that described the theoretical aspects of the issues or surveys that identified the main ethical concerns of healthcare professionals in the end-of-life process [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Interestingly, all 214 ethical issues detected in the aggregated data of this study could be included in one of these predetermined categories.

4.1.1. Ethical Issues Related to Information

Communication between doctor and patient is a process of information exchange aimed at providing the patient with the necessary knowledge to make reflective and autonomous decisions in a specific clinical context. It is an asymmetric and bidirectional process. The healthcare professional, who has knowledge of the clinical data, must explain and advise the patient clearly, truthfully, comprehensibly, and personally about everything concerning their health, and must recognize the value and meaning the patient attributes to the received information [

28,

29,

30]. Available literature confirms that adequate communication can improve adherence to proposed treatments, quality of life, and patient satisfaction, as well as reduce uncertainty and emotional impact [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

In the complex process of informing about the diagnosis, extent, treatment options, and prognosis of cancer, ethical issues may arise. These issues are related to both the quality and quantity of the information provided, which is often modulated according to the professional’s criteria in response to the patient’s or family’s reaction, as well as the timing and context in which the information is offered. The healthcare professional must manage multiple and unpredictable coping styles to the life-threatening nature of the disease, where the patient’s expectations and hopes are not always realistic, and where there may be tendencies towards compassionate limitation of information by the family.

In this study, 13% of patients presented one of the following decision-making problems related to information: a) information exceeding the patient’s desired limits; b) adaptive denial; c) conspiracy of silence. Information exceeding the patient’s desired limits was described as that which caused a high emotional impact and hindered their participation in decision-making because it was provided rapidly in all its aspects, without respecting the patient’s opinion on the amount, timing, or context in which it was given. Denial was described as an adaptive process in which the patient, implicitly or explicitly, preferred not to know all aspects of their disease, especially the prognosis, or adopted alternative arguments to avoid recognizing a reality they felt was unmanageable. The conspiracy of silence was defined as the explicit agreement of the family to avoid providing information, especially the prognosis, with a compassionate intention based on the belief that the patient does not have sufficient emotional resources to face the life-threatening situation.

Various studies indicate that between 20% and 69% of patients with advanced and incurable cancer are unaware of both the prognosis and the palliative intent of chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment [

40,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. Communication with the patient is an ethical and clinical imperative for all healthcare professionals. If a patient has insufficient information, it is the healthcare professional’s duty to expand it truthfully, comprehensibly, and personally to ensure autonomy in decision-making. In this study, the prevalence of ethical issues related to information was limited to situations where the previously provided information or the adaptive reaction to it generated an ethical issue that hindered shared decision-making with the patient. This is likely the reason for the observed differences between the general record on the lack of knowledge about the disease prognosis mentioned earlier (20-69%) and the data provided by this study (13%).

In 2018, the healthcare ethics consultation service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York published a retrospective study on the prevalence of ethical issues consulted. According to this study, 8% of these consultations were related to communication problems and 13% to cases of denial by the patient or their family [

51].

4.2.2. Ethical Issues Related to Proportionality

Deliberation on the proportionality of healthcare interventions caused an ethical issue in 16% of the cases included in this study. The observed issues focused on two distinct situations: futility and treatment refusal. Futility is defined as a medical act considered useless or disproportionate due to its unlikely efficacy and lack of reasonable benefit in an individual clinical condition, according to available scientific evidence [

52,

53]. Refusal of treatment that healthcare professionals consider appropriate requires careful deliberation but is not ethically disputable if it is based on the patient’s reflective reasoning and the conditions of their autonomy of will are met (cognitive competence, complete information, and absence of external interferences) [

54,

55,

56].

In this study, most discrepancies regarding proportionality were observed among the patient’s family members (8%). Less frequently, proportionality conflicts were recorded between the patient/family and the healthcare team (4%) or among the different healthcare professionals involved in the patient’s care (4%). Discrepancies regarding the withdrawal of life support were observed in very few cases (0.5%).

In the previously mentioned study by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, 22% of the consultations to the healthcare ethics service were related to the futility of healthcare interventions, 5% to treatment refusal, and 2% to the withdrawal of life support. Additionally, they observed that in 11% of these consultations, there were discrepancies among the patient’s family members, in 3% between the patient/family and the healthcare team, and in 5% among the members of the treating team [

51].

4.2.3. Ethical Issues Related to Research

Research in patients with advanced cancer who have not responded to conventional treatments undeniably represents an ethical challenge. The vulnerability of these patients and the desperate need to find therapies that delay the progression of their disease can lead to misinterpretation of information, affect the informed consent process, and encourage acceptance of inclusion in an early-phase clinical trial [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61].

In this study, ethical issues related to research were detected in 3% of the included patients. As expected, all patients participating in clinical trials received verbal and written information and signed an informed consent form. However, researchers identified that some of these patients’ expectations were not fully aligned with the actual expected outcomes, or they accepted inclusion in the trial out of fear of being abandoned by the healthcare system. It is noteworthy that conflicts related to research represented 2% of the consultations to the healthcare ethics service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York [

51].

4.2.4. Ethical Issues Related to Palliative Sedation

Palliative sedation is defined as the deliberate administration of sedatives in the necessary doses and combinations to reduce the level of consciousness of a terminal patient for the time required to adequately relieve one or more refractory symptoms [

62,

63,

64]. Approximately 25% (10-50%) of patients with advanced cancer require palliative sedation in the final days of life [

64].

Both the ethical aspects and procedures for the application of terminal sedation, as well as the differential criteria with euthanasia, are widely accepted. However, in daily clinical practice, dilemmas can occasionally arise related to the interpretation of the ethical requirements of palliative sedation: a) definition of refractory symptoms; b) adequacy of sedative doses proportional to the goal of reducing the level of consciousness, not shortening life span; c) involvement of the patient or their family in the sedation decision (explicit, implicit, or delegated consent).

Currently, ethical issues related to palliative sedation are infrequent. In fact, in this study, only one case was detected where the decision for palliative sedation was ethically complex (0.15%). In 2016, a study based on a survey of professionals was published to determine the frequency and difficulty of resolving 20 previously agreed-upon ethical dilemmas in the end-of-life process. The analysis of the responses concluded that the frequency and difficulty of ethical issues related to palliative sedation were low, ranking 18th among the 20 ethical dilemmas examined [

16]. In the study by the healthcare ethics service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, no consultations related to palliative sedation were recorded [

51].

4.2.5. Ethical Issues Related to the Desire to Hasten Death

In the context of incurable cancer, some patients may wish to end their lives. The desire to hasten death is a complex phenomenon influenced by various dimensions of human suffering (physical, emotional, social, spiritual) [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. In some cases, intolerable and refractory physical or psychological suffering may be the determining factor. In others, it may be physical dependency, unwanted loneliness, lack of social support, or the feeling of being a burden to others. It can also appear in patients who have serenely accepted death and consider the remaining time to live as useless and painful.

In this study, the desire to hasten death was recorded as the idea of not wanting to continue living in conditions that the patient considered intolerable and that violated their concept of personal dignity, argued reflectively and repeatedly. Therefore, patients who occasionally expressed the desire to die in the context of a specific crisis of physical or psychological suffering, or those who expressed it as a symptom of major depression, were not included. Identification was carried out in the context of the study’s systematic multidimensional evaluation, according to the clinical judgment of the treating professional, without using any instrument specifically designed to detect the desire to hasten death.

The prevalence of the desire to hasten death in this study was 1.8%. The available literature on the prevalence of the desire to hasten death is very heterogeneous, ranging from 1.5% to 35%, depending on the detection instrument used, the agreed cutoff point, and the care setting [

67,

68,

69].

In recent years, euthanasia has been a topic of social debate in many developed countries. The core of the discussion is whether a person suffering from an incurable and progressive disease that causes intolerable and refractory physical or psychological suffering can decide when, how, and where to die. It is a discussion that seeks to harmonize the right to life and the right to freedom and dignity from a pluralistic and possibilistic perspective. Seven countries worldwide have approved laws regulating euthanasia [

70]. In Spain, where this study was conducted, euthanasia was legalized in March 2021 [

71]. It is noteworthy that the study presented was carried out before this law came into effect (June 2021). We do not know if the implementation of this law will influence the free and spontaneous expression of the desire to hasten death.

4.1. Ethical Aspects and Palliative Complexity

Complex systems are defined as those that depend on the interaction of multiple variables in an unstable equilibrium, highly sensitive to changes in initial conditions, with an outcome that is not always predictable [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

The PALCOM scale identified five domains (symptom burden, refractory pain, functional deterioration, social risk, ethical issues), whose continuous interaction determined the level of complexity of palliative needs in patients with advanced cancer in real clinical practice. Higher complexity levels were associated with high instability (rapid change or death), consumption of PC resources, mortality, and in-hospital death [

9,

10,

11]. Identifying palliative complexity allows for consistent adjustment of referrals to multidisciplinary PC teams and the intensity of their shared intervention with referring teams.

Ethical issues were identified as a variable with high predictive power for the level of palliative complexity. The data provided by this aggregated analysis confirm that the probability of high palliative complexity is significantly higher in patients presenting ethical issues.

4.1. Study Limitations

The PALCOM scale, the source of the data for this study, was designed for adult patients with advanced cancer. Therefore, the results are not generalizable to patients with non-oncological chronic diseases or to the pediatric population.

This study was conducted within a public healthcare system with universal access for all citizens, which includes palliative care in its service portfolio. We do not know if the observed data are generalizable to different healthcare settings.

The data provided correspond to two prospective cohorts of patients with advanced cancer, conducted with the same inclusion and evaluation system by different teams at different times. We believe that the absence of statistically significant differences between socio-demographic and outcome variables in the comparison of both cohorts confirm the consistency of the aggregated analysis and the absence of inclusion or evaluation biases.

Conclussions

This study confirms that ethical issues are highly prevalent in the end-of-life process of patients with advanced cancer. Ethical issues related to information and proportionality in the shared decision-making process are the most frequent. The presence of ethical dilemmas directly influences the complexity of palliative care needs. Early identification and addressing of ethical issues reduce their frequency during patient follow-up. Most observed ethical issues are directly or indirectly associated with patient autonomy.

Practical Implications

The data provided by this study confirm that, in routine clinical practice, it is essential to systematically explore the individual value and meaning each patient attributes to their illness and to identify emerging ethical conflicts. Early identification and addressing of these issues can improve the outcomes of supportive care. In this context, communication skills and basic training in bioethics play a crucial role for all healthcare professionals attending to incurable and life-threatening conditions.

Implications for Research

Due to the high prevalence of ethical issues in the end-of-life process of patients with advanced cancer and their impact on palliative complexity in real clinical practice, we believe it would be interesting to design prospective studies specifically aimed at analyzing the prevalence of different ethical issues and the determining factors for their occurrence.

We do not know the impact of euthanasia regulation laws on the prevalence of patients expressing a consistent desire to hasten death. An update of the PALCOM study would allow us to determine if there are differences in the prevalence of the desire to hasten death between a period before and after the implementation of the euthanasia regulation law in our country.

Author Contributions

A.T. is the director of the PALCOM project and participated in the conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, supervision and writing of the manuscript. M.V. participated in conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, data monitoring and writing of the manuscript. G.C., L.L., C.B., M.C., J.M-H., J.P., C.Z-M., E.H-G., T.G., A.P. and E.F. participated in the field investigation and discussion of the results. N.C. External reviewer as an expert in Clinical Ethics (Former Ethics Professor at the School of Nursing, University of Barcelona). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, University of Barcelona (code: HCB/2016/0611, September 19, 2016). The management of the obtained information was carried out in accordance with Spanish data protection laws.

Informed Consent Statement

All patients received prior written information about the study. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be shared upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Chair of Palliative Care of the University of Barcelona for methodological and administrative support. This study was advised by the Medical Statistics Core Facility, IDIBAPS—Hospital Clinic Barcelona.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Reich, WT. Introduction. In Encyclopedia of Bioethics; Reich WT (editor); Ed. Simon and Schuster Macmillan, New York, USA,1995; Vol 1, pp 1.

- Sallnow L, Smith R, Ahmedzai SH, Bhadelia A, Chamberlain C, Cong Y, Doble B, Dullie L, Durie R, Finkelstein EA, Guglani S, Hodson M, Husebø BS, Kellehear A, Kitzinger C, Knaul FM, Murray SA, Neuberger J, O'Mahony S, Rajagopal MR, Russell S, Sase E, Sleeman KE, Solomon S, Taylor R, Tutu van Furth M, Wyatt K; Lancet Commission on the Value of Death. Report of the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death: bringing death back into life. Lancet 2022, Feb 26;399(10327):837-884.

- Martin-Rosello ML, Sanz-Amores MR, Salvador-Comino MR. Instruments to evaluate complexity in end-of-life care. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2018, Dec;12(4):480-488. [CrossRef]

- Grant M, de Graaf E, Teunissen S. A systematic review of classifications systems to determine complexity of patient care needs in palliative care. Palliat Med 2021, Apr;35(4):636-650. [CrossRef]

- Grant MP, Philip JAM, Deliens L, Komesaroff PA. Understanding Complexity in Care: Opportunities for Ethnographic Research in Palliative Care. J Palliat Care 2022, Feb 15:8258597221078375. [CrossRef]

- Glouberman, S.; Zimmerman, B. Complicated and complex systems: What would successful reform of Medicare look like? Romanow Pap 2002, 2, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Munday, D.F.; Johnson, S.A.; Griffiths, F.E. Complexity theory and palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2003, 17, 308–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodiamont, F.; Jünger, S.; Leidl, R.; Maier, B.O.; Schildmann, E. Understanding complexity– the palliative care situation as a complex adaptive system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019, 19, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuca A, Gómez-Martínez M, Prat A.Tuca A, et al. Predictive model of complexity in early palliative care: a cohort of advanced cancer patients (PALCOM study). Support Care Cancer. 2018, Jan;26(1):241-249. [CrossRef]

- Viladot M, Gallardo-Martínez JL, Hernandez-Rodríguez F, Izcara-Cobo J, Majó-LLopart J, Peguera-Carré M, Russinyol-Fonte G, Saavedra-Cruz K, Barrera C, Chicote M, Barreto TD, Carrera G, Cimerman J, Font E, Grafia I, Llavata L, Marco-Hernandez J, Padrosa J, Pascual A, Quera D, Zamora-Martínez C, Bozzone AM, Font C, Tuca A. Validation Study of the PALCOM Scale of Complexity of Palliative Care Needs: A Cohort Study in Advanced Cancer Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Aug 20;15(16):4182. [CrossRef]

- Tuca A, Viladot M, Carrera G, Llavata L, Barrera C, Chicote M, Marco-Hernández J, Padrosa J, Zamora-Martínez C, Grafia I, Pascual A, Font C, Font E. Evolution of Complexity of Palliative Care Needs and Patient Profiles According to the PALCOM Scale (Part Two): Pooled Analysis of the Cohorts for the Development and Validation of the PALCOM Scale in Advanced Cancer Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2024 Apr 29;16(9):1744. [CrossRef]

- Cerullo G, Videira-Silva A, Carrancha M, Rego F, Nunes R. Complexity of patient care needs in palliative care: a scoping review. Ann Palliat Med. 2023 Jul;12(4):791-802. [CrossRef]

- Tuca A, Viladot M, Barrera C, Chicote M, Casablancas I, Cruz C, Font E, Marco-Hernández J, Padrosa J, Pascual A, Codorniu N, Román. Prevalence of ethical dilemmas in advanced cancer patients (secondary analysis of the PALCOM study). Support Care Cancer. 2021 Jul;29(7):3667-3675. [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp T, Childress J. Moral norms. In: Principles of biomedical ethics, 5th edn. Oxford University Press, New York, USA, 2001; pp 1–25.

- Ong WY, Yee CM, Lee A (2012) Ethical dilemmas in the care of cancer patients near the end of life. Singap Med J 53(1):11–16. 1: Singap Med J 53(1).

- Chih AH, Su P, Hu WY, Yao CA et al. The changes of ethical dilemmas in palliative care. A lesson learned from comparison between 1998 and 2013 in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95(1):e2323. [CrossRef]

- Huang HL, Yao CA, HuWY, Cheng SY, Hwang SJ, Chen CD, Lin WY, Lin YC, Chiu TY. Prevailing ethical dilemmas encountered by physicians in terminal cancer care changed after the enactment of the Natural Death Act: 15 years’ follow-up survey. J Pain Symptom Manag 2018, 55(3):843–850.

- Guevara-López U, Altamirano-BustamanteMM, Viesca-Treviño C (2015) New frontiers in the future of palliative care: real-world bioethical dilemmas and axiology of clinical practice. BMC Med Ethics 2015, 16:11.

- Chiu TY, Hu WY, Huang HL, Yao CA, Chen CY. Prevailing ethical dilemmas in terminal care for patients with cancer in Taiwan. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27(24): 3964–3968. [CrossRef]

- Kinzbrunner, BM. Ethical dilemmas in hospice and palliative care. Support Care Cancer 1995, 3(1):28–36. [CrossRef]

- Blanco Portillo, A. , García-Caballero, R., Real de Asúa, D. et al. What ethical conflicts do internists in Spain, México and Argentina encounter? An international cross-sectional observational study based on a self-administrated survey. BMC Med Ethics 2024, 25, 123.

- Cherny NI, Ziff-Werman B.Cherny NI, et al. Ethical considerations in the relief of cancer pain. Support Care Cancer 2023, Jun 23, 31(7):414.

- Crico, C. , Sanchini, V. , Casali, P.G. et al. Ethical issues in oncology practice: a qualitative study of stakeholders’ experiences and expectations. BMC Med Ethics 2022, 23, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui D, Bruera E. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System 25 Years Later: Past, Pre-sent, and Future Developments. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2017, 53 (3), 630-643. [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Bruera, E. A personalized approach to assessing and managing pain in patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol 2014, 32, 1640–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainsinger, R.L.; Nekolaichuk, C.L. A “TNM” classification system for cancer pain: The Edmonton Classification System for Cancer Pain (ECS-CP). Support. Care Cancer 2008, 16, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainsinger, R.L.; Nekolaichuk, C.L.; Lawlor, P.G.; Neumann, C.M.; Hanson, J.; Vigano, A. A multicenter study of the revised Edmonton Staging System for classifying cancer pain in advanced cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 2005, 29, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan T, Coyle N, Frankel RM, Berry DL, Bohlke K, Epstein RM, Finlay E, Jackson VA, Lathan CS, Loprinzi CL, Nguyen LH, Seigel C, Baile WF. Patient-Clinician Communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2017, Nov 1;35(31):3618-3632.

- Katz SJ, Belkora J, Elwyn G: Shared decision making for treatment of cancer: challengesand opportunities. J Oncol Pract 2014, 10 (3): 206-8.

- Witteman HO, Julien AS, Ndjaboue R, et al.: What Helps People Make Values-Congruent Medical Decisions? Eleven Strategies Tested across 6 Studies. Med Decis Making 2020, 40 (3):266-278. [CrossRef]

- Ong LM, Visser MR, Lammes FB, et al.: Doctor-patient communication and cancer patients' quality of life and satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns 2000, 41 (2): 145-56.

- Zachariae R, Pedersen CG, Jensen AB, et al.: Association of perceived physician communication style with patient satisfaction, distress, cancer-related self-efficacy, and perceived control over the disease. Br J Cancer 2003, 88 (5): 658-65.

- Lorusso D, Bria E, Costantini A, et al.: Patients' perception of chemotherapy sideeffects: Expectations, doctor-patient communication and impact on quality of life – An Italian survey. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2017, 26 (2).

- Pozzar RA, Xiong N, Hong F, et al.: Perceived patient-centered communication, qualityof life, and symptom burden in individuals with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2021, 163 (2):408-418. [CrossRef]

- Mack JW, Fasciano KM, Block SD: Communication About Prognosis With Adolescent andYoung Adult Patients With Cancer: Information Needs, Prognostic Awareness, andOutcomes of Disclosure. J Clin Oncol 2018, 36 (18): 1861-1867.

- Shin JA, El-Jawahri A, Parkes A, et al.: Quality of Life, Mood, and Prognostic Understanding in Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer. J Palliat Med 2016, 19 (8): 863-9. [CrossRef]

- Lin JJ, Chao J, Bickell NA, et al.: Patient-provider communication and hormonal therapyside effects in breast cancer survivors. Women Health 2017, 57 (8): 976-989.

- Jacobs JM, Pensak NA, Sporn NJ, et al.: Treatment Satisfaction and Adherence to Oral Chemotherapy in Patients With Cancer. J Oncol Pract 13 (5): e474-e485, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Albrecht TL, Eggly SS, Gleason ME, et al.: Influence of clinical communication on patients decision making on participation in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26 (16): 2666-73. [CrossRef]

- Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al.: Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012, 367 (17): 1616-25. [CrossRef]

- Lobb EA, Halkett GK, Nowak AK: Patient and caregiver perceptions of communicationof prognosis in high grade glioma. J Neurooncol 2011, 104 (1): 315-22.

- Liu PH, Landrum MB, Weeks JC, et al.: Physicians' propensity to discuss prognosis isassociated with patients' awareness of prognosis for metastatic cancers. J Palliat Med 2014, 17 (6): 673-82.

- Tang ST, Wen FH, Hsieh CH, et al.: Preferences for Life-Sustaining Treatments andAssociations With Accurate Prognostic Awareness and Depressive Symptoms inTerminally Ill Cancer Patients' Last Year of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016, 51 (1): 41-51.e1.

- Graham J, Ramirez A: Improving the working lives of cancer clinicians. Eur J Cancer Care(Engl) 2002, 11 (3): 188-92.

- Cherny NI, Nortjé N, Kelly R, Zimmermann C, Jordan K, Kreye G et al. A taxonomy of the factors contributing to the overtreatment of cancer patients at the end of life. What is the problem? Why does it happen? How can it be addressed? ESMO Open 2025, Vol. 10 Issue 1,Published online: January 6, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chen AB, Cronin A, Weeks JC, et al.: Expectations about the effectiveness of radiationtherapy among patients with incurable lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 31 2013, (21): 2730-5.

- Epstein AS, Prigerson HG, O’Reilly EM, Maciejewski PK. Discussions of life expectancy and changes in illness understanding in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016, 34(20):2398–2403. [CrossRef]

- Enzinger AC, Zhang B, Schrag D, Prigerson HG. Outcomes of prognostic disclosure: associations with prognostic understanding, distress, and relationship with physician among patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015, 33(32):3809–3816. [CrossRef]

- Justo Roll I, Simms V, Harding R (2009) Multidimensional problems among advanced cancer patients in Cuba: awareness of diagnosis is associated with better patient status. J Pain Symptom Manag 2008, 37:325–330.

- Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Katsouda E, Vlahos L. Patterns and barriers in information disclosure between health care professionals and relatives with cancer patients in Greek society. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2005,14(2):175–181. [CrossRef]

- Corbett V, Epstein AS, McCabe MS. Characteristics and Outcomes of Ethics Consultations on a Comprehensive Cancer Center's Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology Service. HEC Forum 2018, 30(4):379-387. [CrossRef]

- Bernat, JL. Medical futility. Definition, determination, and disputes in critical care. Neurocrit Care 2005, 2:198–205. [CrossRef]

- Rolak S, Elhawary A, Diwan T, Watt KD, Rolak S, et al. Futility and poor outcomes are not the same thing: A clinical perspective of refined outcomes definitions in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2024, Apr 1;30(4): 421-430. [CrossRef]

- AMA Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 2.1.3. Available at: https:// www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/ withholdinginformation-patients. Accessed January 2025.

- Code of Medical Ethics (2016) Organización Médica Colegial de España. Available at: https://www.cgcom.es/ sites/ default/files/ code_of_medical_ethics/ index. html. Accessed January 2025.

- Foster C. Autonomy should chair, not rule. Lancet 2010, 375(9712):368–369. [CrossRef]

- Guindalini, R.S.C., Riechelmann, R.P., Arai, R.J. (2018). In: Araújo, R., Riechelmann, R. (eds) Methods and Biostatistics in Oncology. Springer, Cham. https://doi-org.sire.ub.edu/10.1007/978-3-319-71324-3_15. Accessed January 2025.

- Daugherty, CK. Ethical issues in the development of new agents. Investig New Drugs 1999,17: 145–53. [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer MH, Krantz DS, Wichman A, et al. The impact of disease severity on the informed consent process in clinical research. Am J Med 1996, 100:261–8. [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, CK. Impact of therapeutic research on informed consent and the ethics of clinical trials: a medical oncology perspective. J Clin Oncol 1999, 17:1601–17. [CrossRef]

- Meropol NJ, Weinfurt KP, Burnett CB, et al. Perceptions of patients and physicians regarding phase I cancer clinical trials: implications for physician-patient communication. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2589–96. [CrossRef]

- Twycross, R. Reflections on palliative sedation. Palliative Care: Research and Treatment. 2019,12.

- Materstvedt LJ. Distinction between euthanasia and palliative sedation is clear-cut. J Med Ethics 2020, 46(1):55–56. [CrossRef]

- Cherny NI, ESMO Guidelines Working Group. ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of refractory symptoms at the end of life and the use of palliative sedation. Ann Oncol 2014, 25 Suppl 3:iii143–iii152.

- A Balaguer, C Monforte-Royo, J Porta-Sales, et al. An international consensus definition of the wish to hasten death and its related factors, PLoS One 2016, 11: 1-14.

- A Rodríguez-Prat, A Balaguer, A Booth, et al. Understanding patients’ experiences of the wish to hasten death: an updated and expanded systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Open 2017, 7 ,16659. [CrossRef]

- A Belar, M Arantzamendi, Y Santesteban, et al. Cross-sectional survey of the wish to die among palliative patients in Spain: one phenomenon, different experiences. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2021, 11:156-162. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Prat A, Pergolizzi D, Crespo I, Julià-Torras J, Balaguer A, Kremeike K, Voltz R, Monforte-Royo C.Rodríguez-Prat A, et al. The Wish to Hasten Death in Patients With Life-Limiting Conditions. A Systematic Overview. J Pain Symptom Manage 2024, Aug; 68(2):e91-e115. [CrossRef]

- M Bellido-Pérez, C Monforte-Royo, J Tomás-Sábado, et al. Assessment of the wish to hasten death in patients with advanced disease: a systematic review of measurement instruments. Palliat Med 2017, 31:510-525. [CrossRef]

- World Population Review. Countries Where Euthanasia is Legal in 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/ country-rankings/where-is-euthanasia-legal. Accessed January 2025.

- Ley Orgánica 3/2021, de 24 de marzo, de regulación de la eutanasia. Ministerio de la Presidencia, Justicia y relaciones con las Cortes. Gobierno de España. Boletín Oficial del Estado. núm. 72, de 25 de marzo de 2021. https://www.boe.es/buscar/ act.php?id=BOE-A-2021-4628. Accessed January 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).