Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Trial

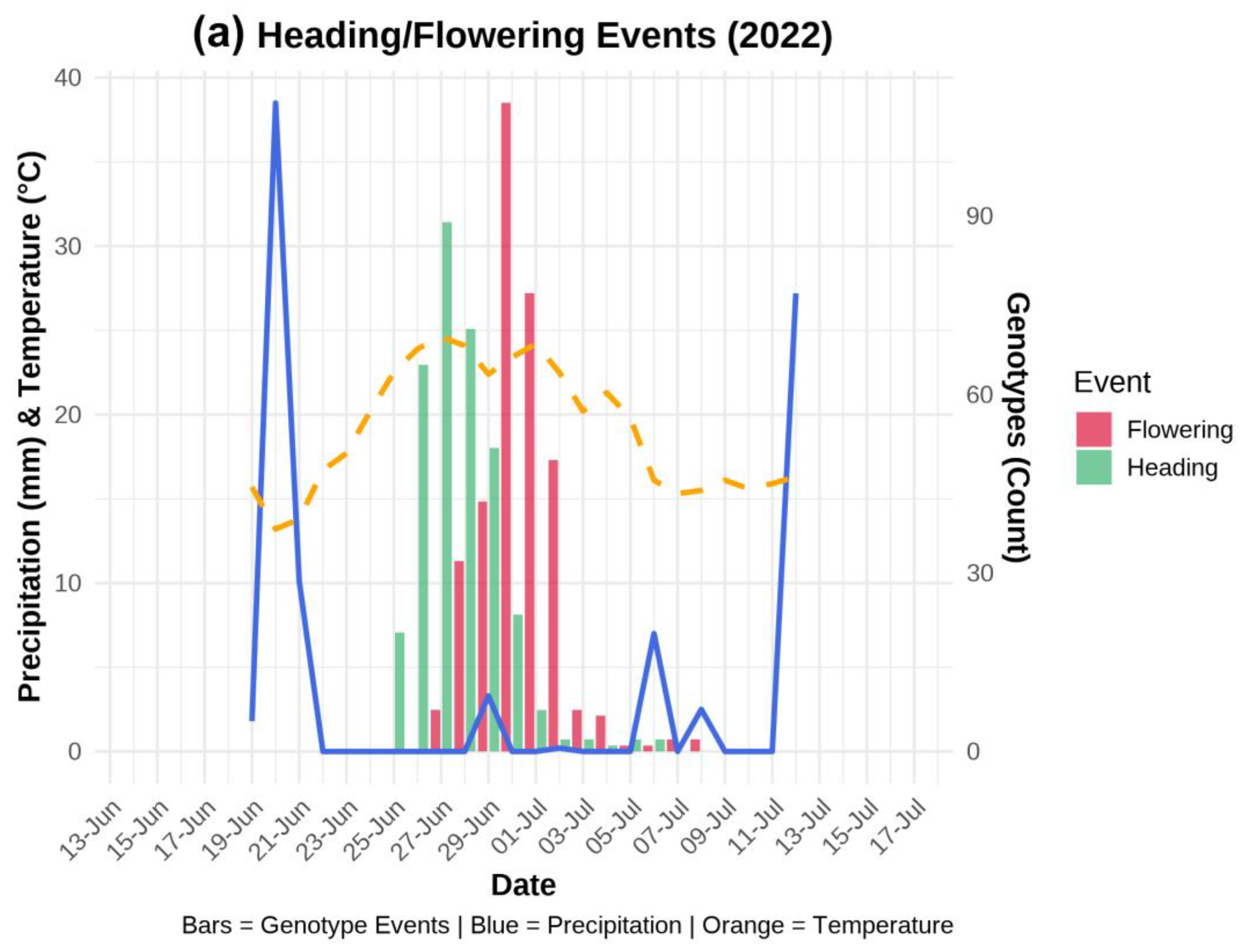

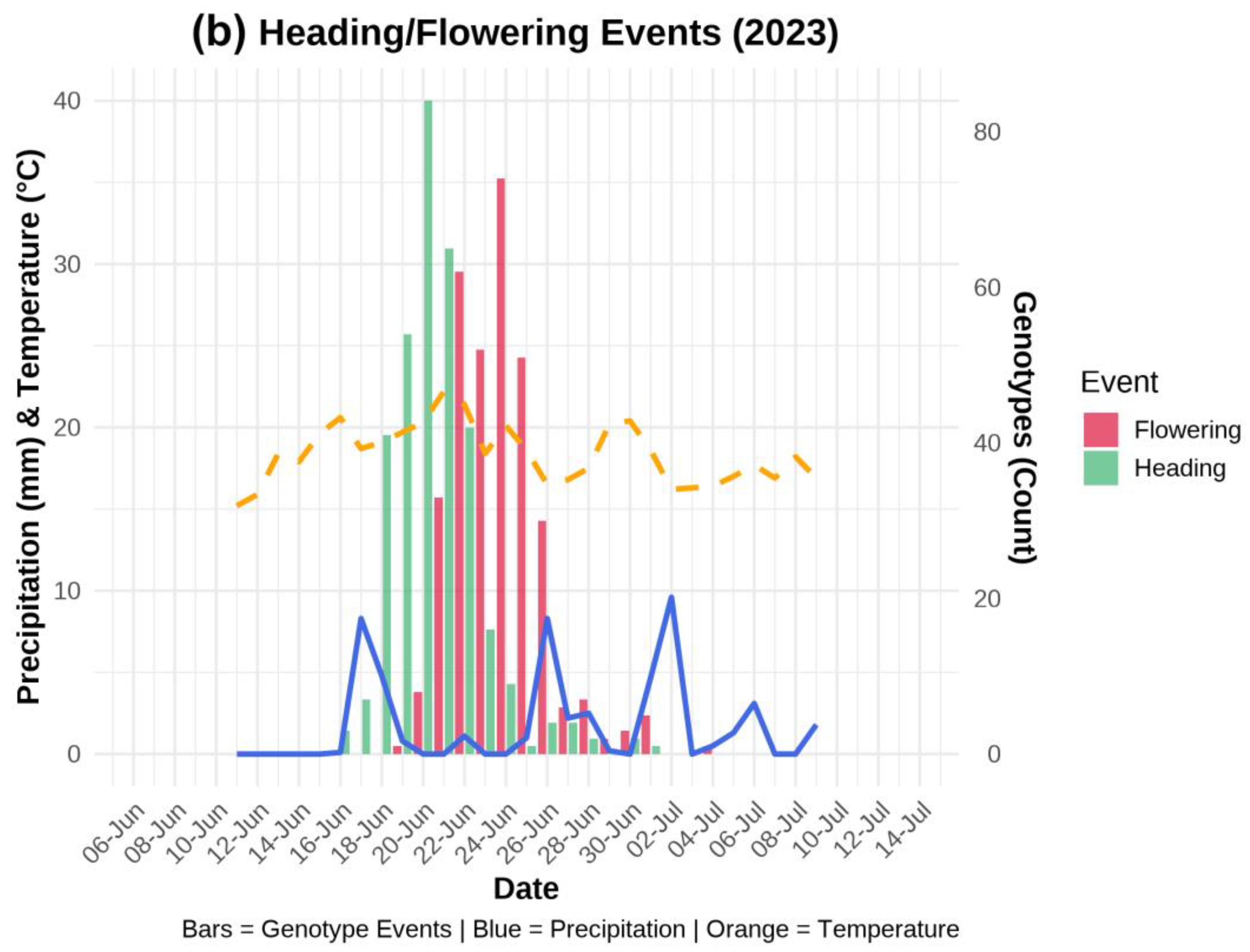

2.2. Meteorological Data

2.3. Evaluation of Morphological and Phenological Traits

2.4. Evaluation of FHB Severity

2.5. Genotyping for Rht Alleles Identification

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Genotypic Effect on Morpho-Phenological and FHB Severity

3.2. Phenotypic Variability and Genotypic/Year Effects on Morpho-Phenological and FHB Severity

3.3. Year-Wise Association Between Phenological Traits and Plant Height with FHB Severity

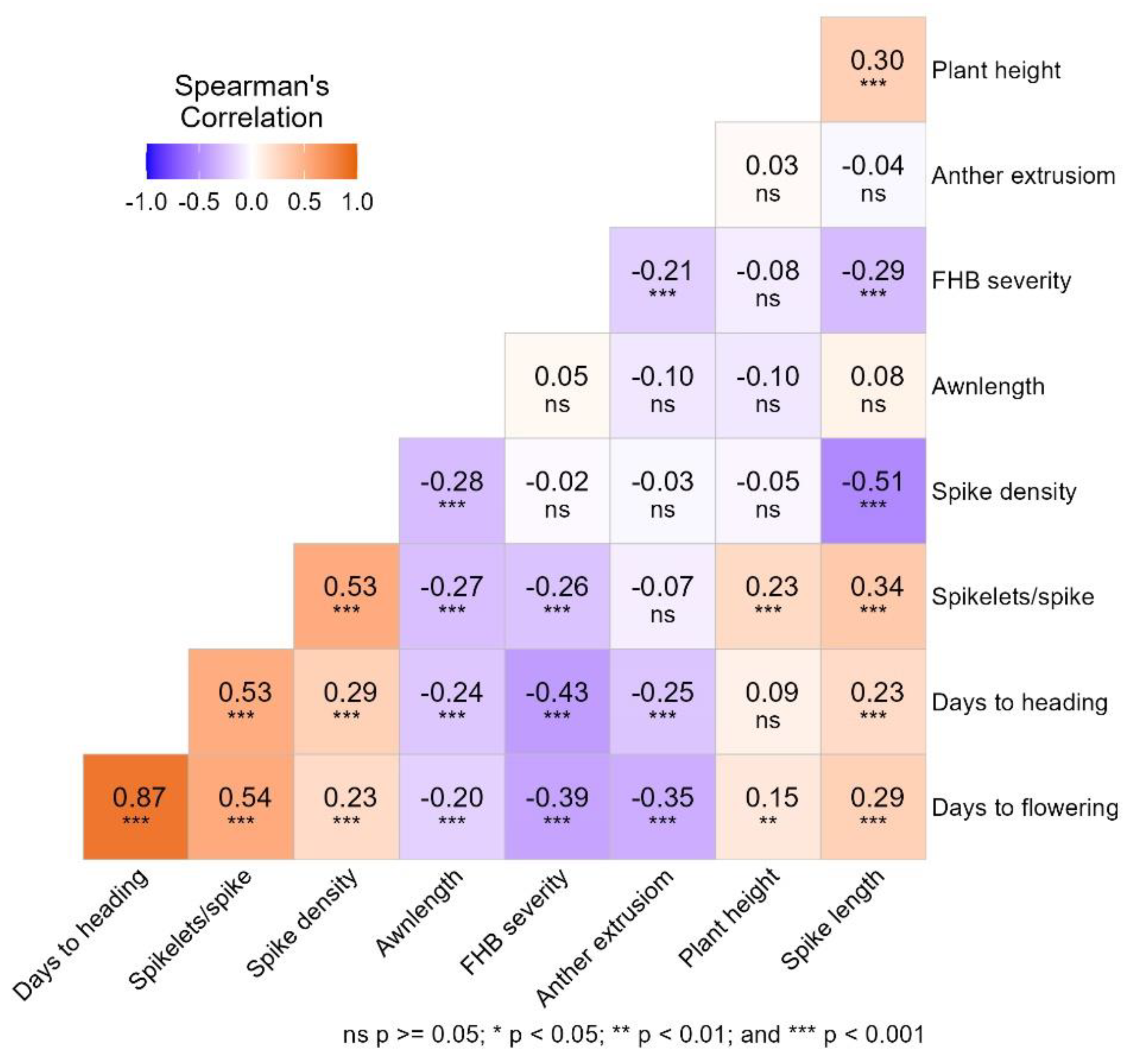

3.4. Correlation Analysis Between Morpho-Phenological and FHB Traits over Two Years

3.4.1. Association Between Morphological Traits and Phenological Traits

3.4.2. Association Between Morpho-Phenological and FHB Traits

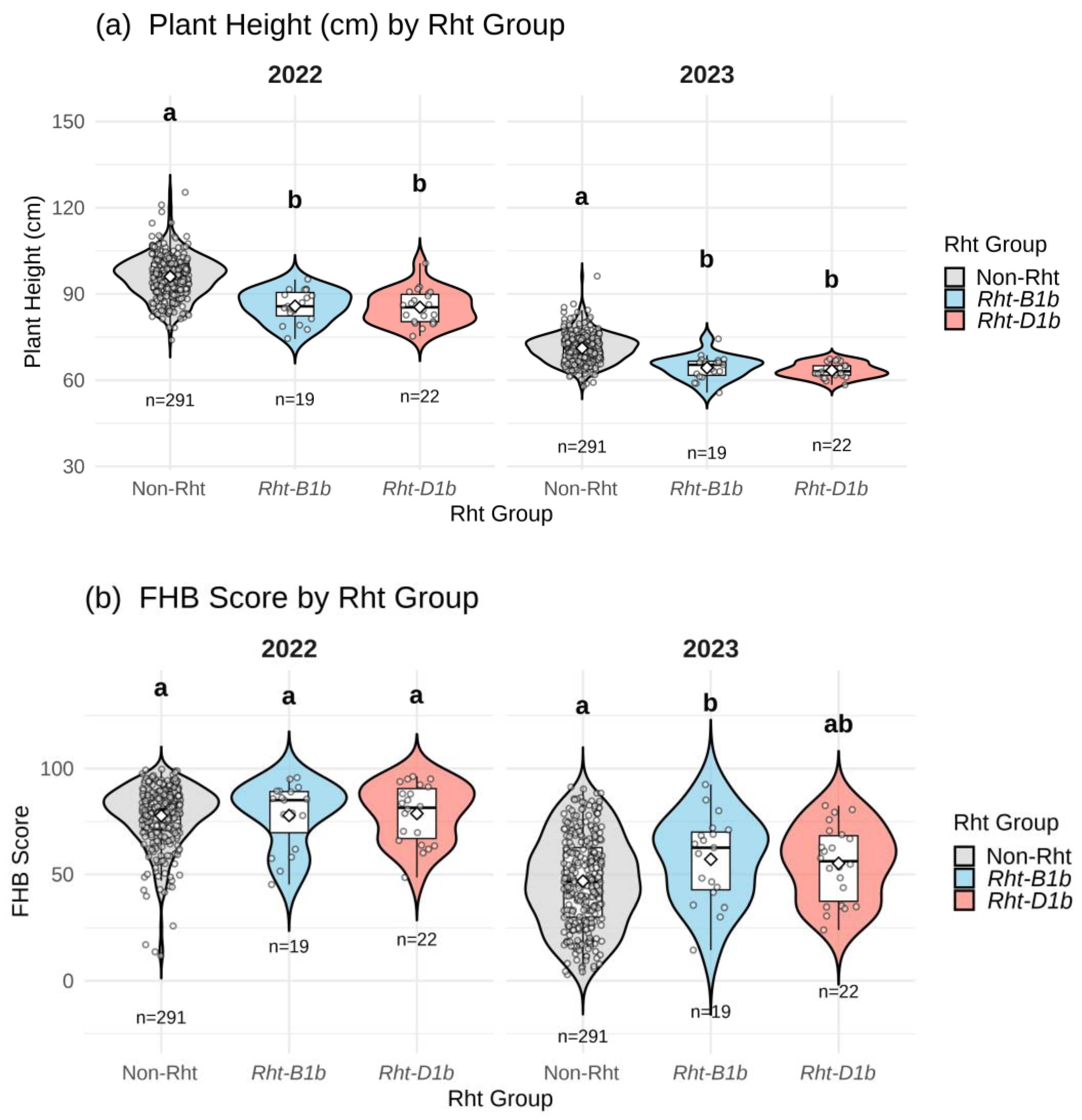

3.5. Influence of Rht Genes on Plant Height and Its Association with FHB Susceptibility

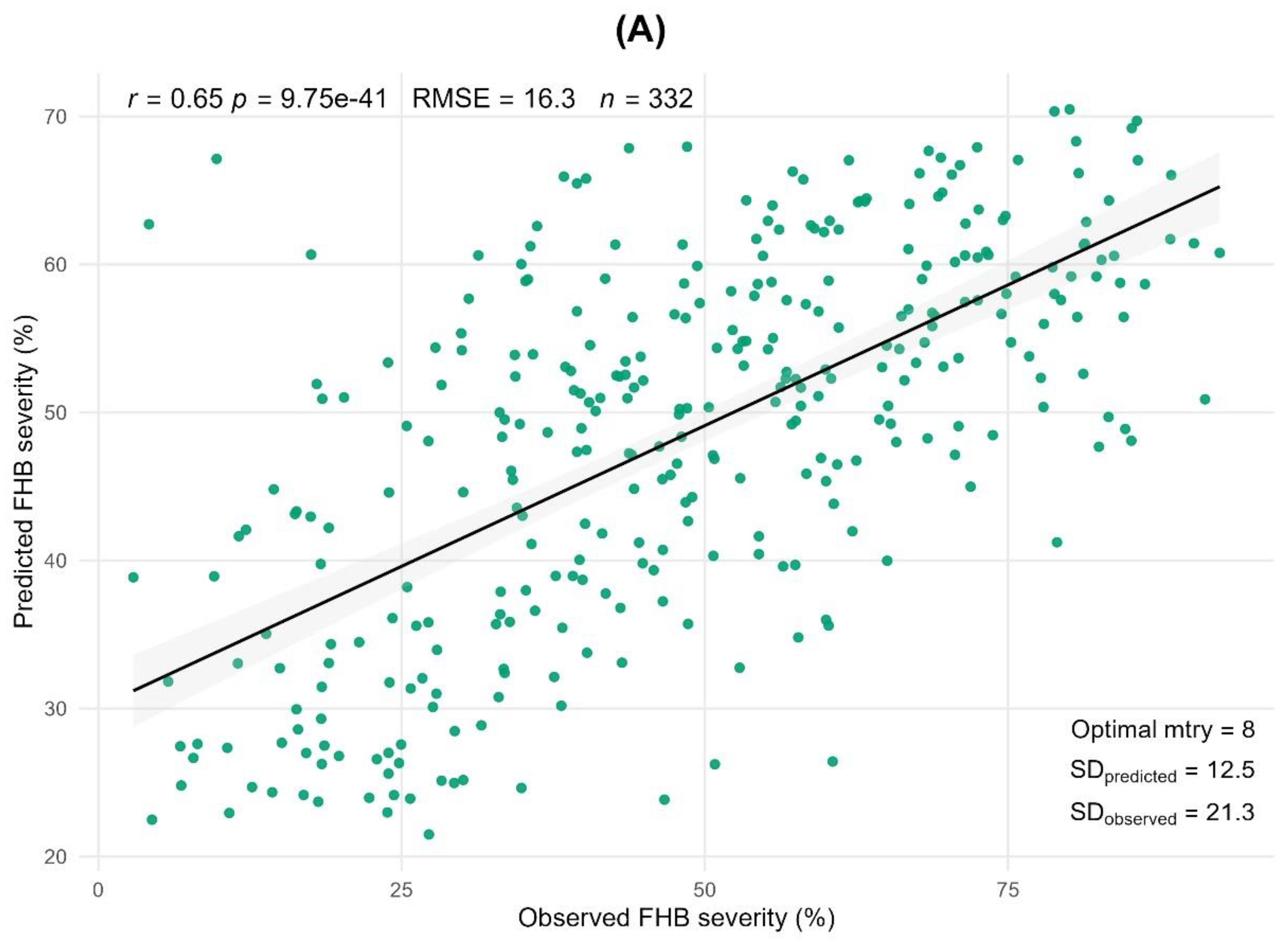

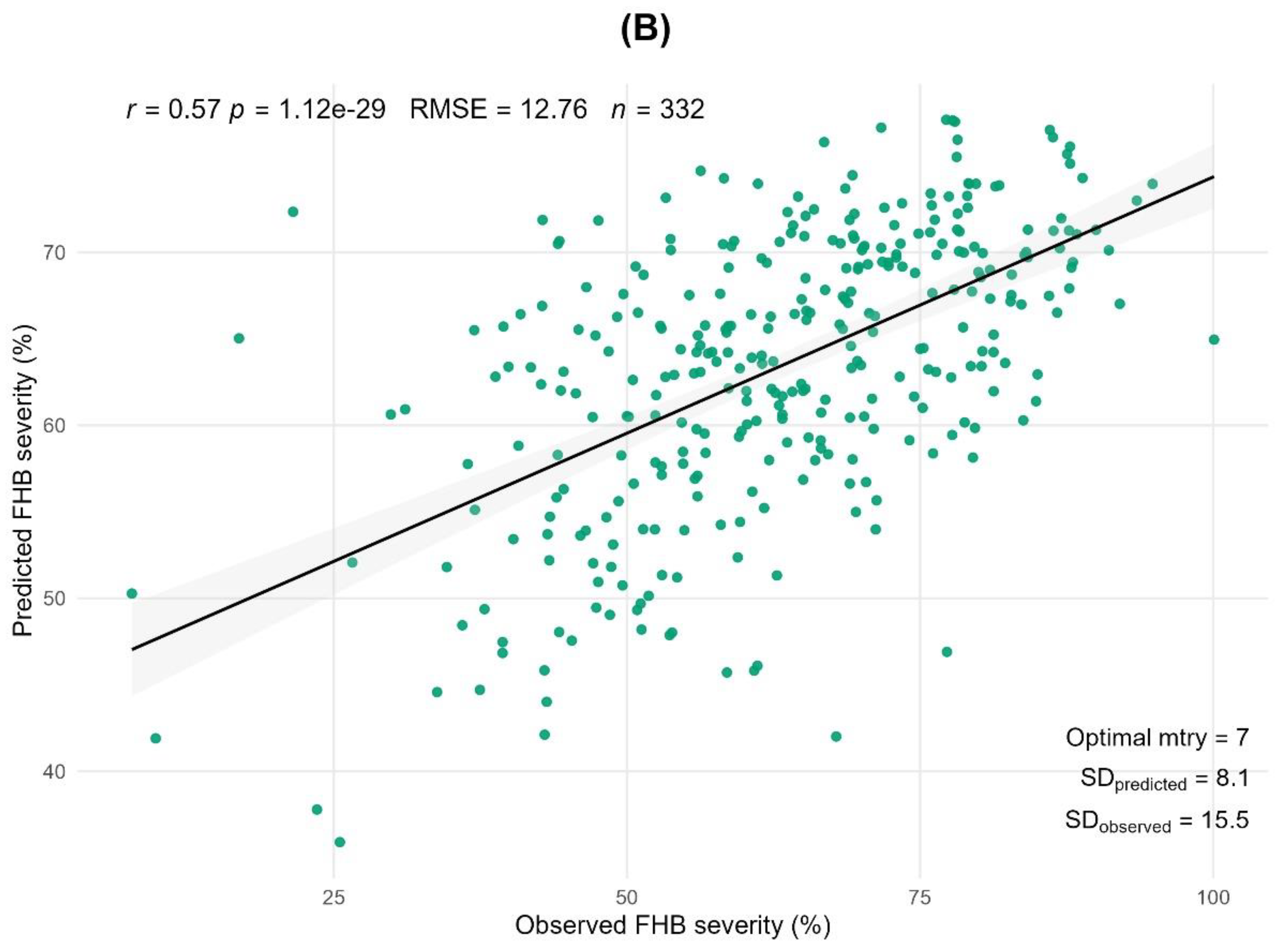

3.6. Prediction of Resistance on the Basis of Morpho-Phenological Traits

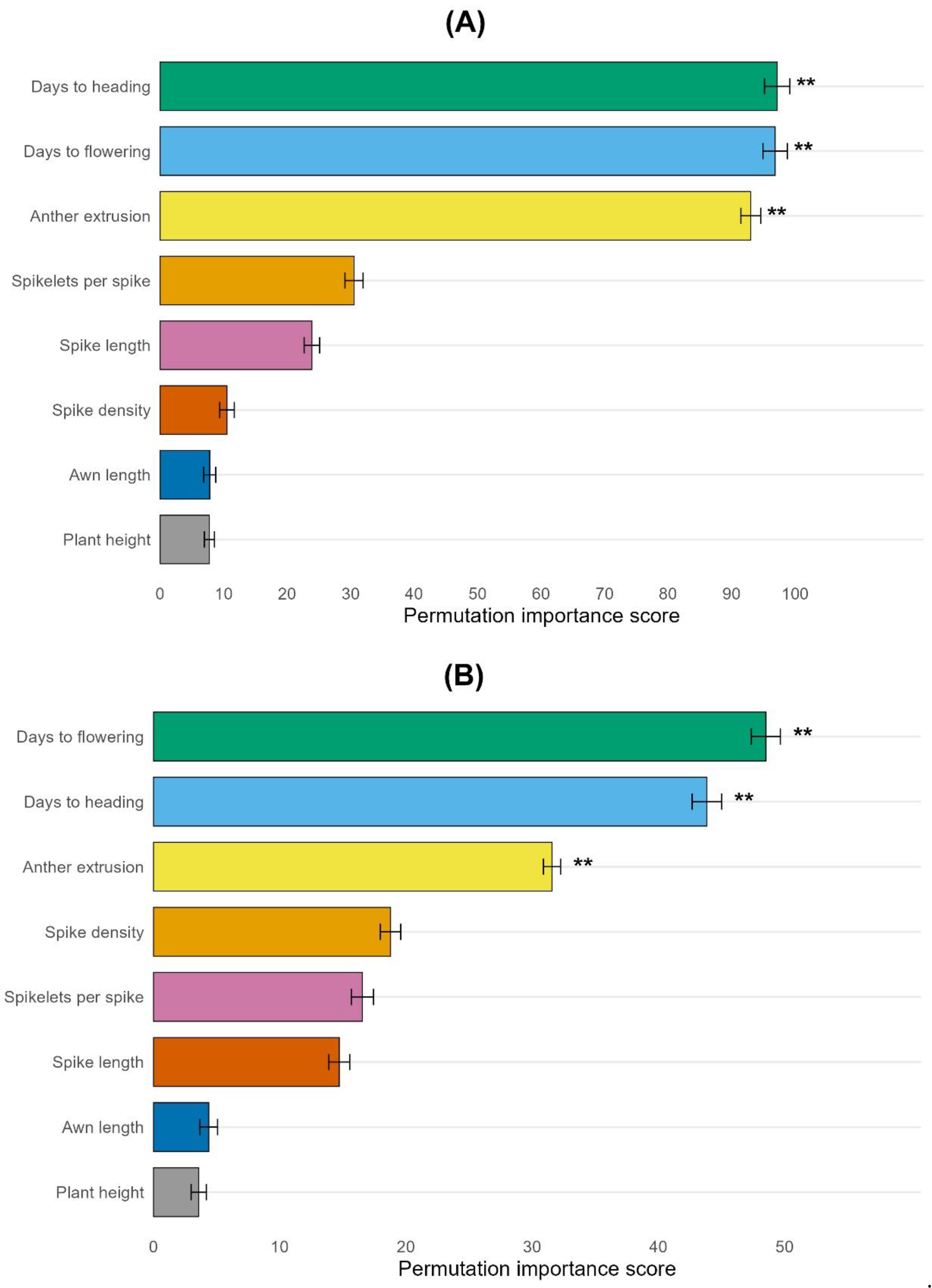

3.7. Ranking of Morpho-Phenological Traits by Their Importance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bottalico, A.; Perrone, G. Toxigenic Fusarium Species and Mycotoxins Associated with Head Blight in Small-Grain Cereals in Europe. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2002, 108, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, D.W.; Jenkinson, P.; McLEOD, L. Fusarium Ear Blight (Scab) in Small Grain Cereals—a Review. Plant Pathology 1995, 44, 207–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronaitis, T.; Simpfendorfer, S.; Hüberli, D. Importance of Fusarium Spp. in Wheat to Food Security: A Global Perspective. In Plant Diseases and Food Security in the 21st Century; Scott, P., Strange, R., Korsten, L., Gullino, M.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 127–159. ISBN 978-3-030-57899-2. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, S.G. Influence of Agricultural Practices on Fusarium Infection of Cereals and Subsequent Contamination of Grain by Trichothecene Mycotoxins. Toxicology Letters 2004, 153, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lori, G.A.; Sisterna, M.N.; Sarandón, S.J.; Rizzo, I.; Chidichimo, H. Fusarium Head Blight in Wheat: Impact of Tillage and Other Agronomic Practices under Natural Infection. Crop Protection 2009, 28, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Lillemo, M.; Skinnes, H.; He, X.; Shi, J.; Ji, F.; Dong, Y.; Bjørnstad, A. Anther Extrusion and Plant Height Are Associated with Type I Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight in Bread Wheat Line Shanghai-3/Catbird. Theor Appl Genet 2013, 126, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Rooney, A.P.; Proctor, R.H.; Brown, D.W.; McCormick, S.P.; Ward, T.J.; Frandsen, R.J.N.; Lysøe, E.; Rehner, S.A.; Aoki, T.; et al. Phylogenetic Analyses of RPB1 and RPB2 Support a Middle Cretaceous Origin for a Clade Comprising All Agriculturally and Medically Important Fusaria. Fungal Genetics and Biology 2013, 52, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburic-Ilincic, L.; Wragg, A.; Schaafsma, A. Mycotoxin Accumulation and Fusarium Graminearum Chemotype Diversity in Winter Wheat Grown in Southwestern Ontario. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2015, 95, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegulo, S.N.; Baenziger, P.S.; Hernandez Nopsa, J.; Bockus, W.W.; Hallen-Adams, H. Management of Fusarium Head Blight of Wheat and Barley. Crop Protection 2015, 73, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Singh, P.K.; Dreisigacker, S.; Singh, S.; Lillemo, M.; Duveiller, E. Dwarfing Genes Rht-B1b and Rht-D1b Are Associated with Both Type I FHB Susceptibility and Low Anther Extrusion in Two Bread Wheat Populations. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. Epidemiology of Fusarium Graminearum Diseases of Wheat and Corn; 1994; pp. 19–36. ISBN 978-0-9624407-5-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dill-Macky, R.; Jones, R.K. The Effect of Previous Crop Residues and Tillage on Fusarium Head Blight of Wheat. Plant Disease 2000, 84, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisaac, E.; Mahlein, A.-K. Fusarium Head Blight on Wheat: Biology, Modern Detection and Diagnosis and Integrated Disease Management. Toxins 2023, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerstmayr, H.; Ban, T.; Anderson, J.A. QTL Mapping and Marker-Assisted Selection for Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Wheat: A Review. Plant Breeding 2009, 128, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesterházy, Á.; Bartók, T.; Mirocha, C.G.; Komoróczy, R. Nature of Wheat Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight and the Role of Deoxynivalenol for Breeding. Plant Breeding 1999, 118, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Han, B. Natural Variations and Genome-Wide Association Studies in Crop Plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2014, 65, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paillard, S.; Schnurbusch, T.; Tiwari, R.; Messmer, M.; Winzeler, M.; Keller, B.; Schachermayr, G. QTL Analysis of Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight in Swiss Winter Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). Theor Appl Genet 2004, 109, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesterházy, A. Types and Components of Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight of Wheat. Plant Breeding 1995, 114, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Sha, J.; Sun, Y.; Hu, Z.; Gong, L.; Dai, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Wheat Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight and Breeding Strategies. Crop Health 2025, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesterhazy, A. What Is Fusarium Head Blight (FHB) Resistance and What Are Its Food Safety Risks in Wheat? Problems and Solutions—A Review. Toxins 2024, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerstmayr, M.; Buerstmayr, H. Comparative Mapping of Quantitative Trait Loci for Fusarium Head Blight Resistance and Anther Retention in the Winter Wheat Population Capo × Arina. Theor Appl Genet 2015, 128, 1519–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, J.K.; N’Diaye, A.; Walkowiak, S.; Nilsen, K.T.; Clarke, J.M.; Kutcher, H.R.; Steiner, B.; Buerstmayr, H.; Pozniak, C.J. Fusarium Head Blight in Durum Wheat: Recent Status, Breeding Directions, and Future Research Prospects. Phytopathology® 2019, 109, 1664–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Farooqi, A.; Foulkes, J.; Sparkes, D.L.; Linforth, R.; Ray, R.V. Canopy and Ear Traits Associated With Avoidance of Fusarium Head Blight in Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesterhazy, A. Updating the Breeding Philosophy of Wheat to Fusarium Head Blight (FHB): Resistance Components, QTL Identification, and Phenotyping—A Review. Plants (Basel) 2020, 9, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.P.T. The Identification of Physiological Traits in Wheat Confering Passive Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight. Available online: https://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/28786/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Couture, L. Receptive De Cultivars De Cereals De Printemps A La Contamination Des Graines Sur Inflorescence Par Les Fusarium Spp. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1982, 62, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton; Jenkinson; Hollins; Parry. Relationship between Cultivar Height and Severity of Fusarium Ear Blight in Wheat. Plant Pathology 1999, 48, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerstmayr, M.; Buerstmayr, H. The Semidwarfing Alleles Rht-D1b and Rht-B1b Show Marked Differences in Their Associations with Anther-Retention in Wheat Heads and with Fusarium Head Blight Susceptibility. Phytopathology® 2016, 106, 1544–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Szabo-Hever, A.; Bjørnstad, Å.; Lillemo, M.; Semagn, K.; Mesterhazy, A.; Ji, F.; Shi, J.; Skinnes, H. Two Major Resistance Quantitative Trait Loci Are Required to Counteract the Increased Susceptibility to Fusarium Head Blight of the Rht-D1b Dwarfing Gene in Wheat. Crop Science 2011, 51, 2430–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasachary, S.; Gosman, N.; Steed, A.; Hollins, T.W.; Bayles, R.; Jennings, P.; Nicholson, P. Semi-Dwarfing Rht-B1 and Rht-D1 Loci of Wheat Differ Significantly in Their Influence on Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight. Theor Appl Genet 2009, 118, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessmann, E.W.; Van Sanford, D.A. Associations between Morphological and FHB Traits in a Soft Red Winter Wheat Population. Euphytica 2019, 215, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedaner, T.; Voss, H.-H. Effect of Dwarfing Rht Genes on Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Two Sets of Near-Isogenic Lines of Wheat and Check Cultivars. Crop Science 2008, 48, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.F.; Lori, G.A.; Cendoya, G.; Alonso, M.P.; Panelo, J.S.; Malbrán, I.; Mirabella, N.E.; Pontaroli, A.C. Spike Architecture Traits Associated with Type II Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight in Bread Wheat. Euphytica 2021, 217, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.F.; Lori, G.A.; Cendoya, M.G.; Panelo, J.S.; Alonso, M.P.; Mirabella, N.E.; Malbrán, I.; Pontaroli, A.C. Using Anthesis Date as a Covariate to Accurately Assessing Type II Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight in Field-Grown Bread Wheat. Crop Protection 2021, 142, 105504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, K.; Fujita, M.; Kawada, N.; Nakajima, T.; Nakamura, K.; Maejima, H.; Ushiyama, T.; Hatta, K.; Matsunaka, H. Minor Differences in Anther Extrusion Affect Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight in Wheat. Journal of Phytopathology 2013, 161, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinnes, H.; Tarkegne, Y.; Dieseth, J.; Bjørnstad, Å. Associations between Anther Extrusion and Fusarium Head Blight in European Wheat. CEREAL RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS 2008, 36, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xu, F.; Qin, D.; Li, M.; Fedak, G.; Cao, W.; Yang, L.; Dong, J. Molecular Mapping of QTLs Conferring Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Chinese Wheat Cultivar Jingzhou 66. Plants 2020, 9, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, M.; Bergstrom, G.; De Wolf, E.; Dill-Macky, R.; Hershman, D.; Shaner, G.; Van Sanford, D. A Unified Effort to Fight an Enemy of Wheat and Barley: Fusarium Head Blight. Plant Dis 2012, 96, 1712–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, L.; Dedryver, F.; Morlais, J.-Y.; Bodusseau, V.; Negre, S.; Bilous, M.; Groos, C.; Trottet, M. Mapping of Quantitative Trait Loci for Field Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight in an European Winter Wheat. Theor Appl Genet 2003, 106, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedaner, T.; Flamm, C.; Oberforster, M. The Importance of Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in the Cereal Breeding Industry: Case Studies from Germany and Austria. Plant Breeding 2024, 143, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinnes, H.; Semagn, K.; Tarkegne, Y.; Marøy, A.G.; Bjørnstad, Å. The Inheritance of Anther Extrusion in Hexaploid Wheat and Its Relationship to Fusarium Head Blight Resistance and Deoxynivalenol Content. Plant Breeding 2010, 129, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Aleliūnas, A.; Lillemo, M.; Gorash, A. Analyses of Wheat Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight Using Different Inoculation Methods. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Aleliūnas, A.; Armonienė, R.; Brazauskas, G.; Gorash, A. GWAS Analysis of Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in a Nordic-Baltic Spring Wheat Panel. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissonnette, K. Scouting for Fusarium Head Blight (FHB) and Harvest Considerations; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, M.; He, X.; Singh, R.P.; Duveiller, E.; Lillemo, M.; Pereyra, S.A.; Westerdijk-Hoks, I.; Kurushima, M.; Yau, S.-K.; Benedettelli, S.; et al. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of CIMMYT’s 15th International Fusarium Head Blight Screening Nursery of Wheat. Euphytica 2015, 205, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R: Epsilon-Squared. Available online: https://search.r-project.org/CRAN/refmans/rcompanion/html/epsilonSquared.html (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Alvarado, G.; Rodríguez, F.M.; Pacheco, A.; Burgueño, J.; Crossa, J.; Vargas, M.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Lopez-Cruz, M.A. META-R: A Software to Analyze Data from Multi-Environment Plant Breeding Trials. The Crop Journal 2020, 8, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivoto, T.; Lúcio, A.D. Metan: An R Package for Multi-Environment Trial Analysis. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2020, 11, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.N.; Ziegler, A. Ranger: A Fast Implementation of Random Forests for High Dimensional Data in C++ and R. Journal of Statistical Software 2017, 77, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Machine Learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, A.; Toloşi, L.; Sander, O.; Lengauer, T. Permutation Importance: A Corrected Feature Importance Measure. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buerstmayr, M.; Steiner, B.; Buerstmayr, H. Breeding for Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Wheat—Progress and Challenges. Plant Breeding 2020, 139, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedaner, T.; Sieber, A.-N.; Desaint, H.; Buerstmayr, H.; Longin, C.F.H.; Würschum, T. The Potential of Genomic-Assisted Breeding to Improve Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Winter Durum Wheat. Plant Breeding 2017, 136, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Amores, J.; Michel, S.; Miedaner, T.; Longin, C.F.H.; Buerstmayr, H. Genomic Predictions for Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in a Diverse Durum Wheat Panel: An Effective Incorporation of Plant Height and Heading Date as Covariates. Euphytica 2020, 216, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Abate, Z.A.; Lu, H.; Musket, T.; Davis, G.L.; McKendry, A.L. QTL Associated with Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in the Soft Red Winter Wheat Ernie. Theor Appl Genet 2007, 115, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, D.J.; Fedak, G.; Savard, M. Molecular Mapping of Novel Genes Controlling Fusarium Head Blight Resistance and Deoxynivalenol Accumulation in Spring Wheat. Genome 2003, 46, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirgozliev, S.R.; Edwards, S.G.; Hare, M.C.; Jenkinson, P. Strategies for the Control of Fusarium Head Blight in Cereals. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2003, 109, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, J.D.; Madden, L.V.; Paul, P.A. Quantifying the Effects of Fusarium Head Blight on Grain Yield and Test Weight in Soft Red Winter Wheat. Phytopathology® 2015, 105, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanic, V.; Cosic, J.; Zdunic, Z.; Drezner, G. Characterization of Agronomical and Quality Traits of Winter Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.) for Fusarium Head Blight Pressure in Different Environments. Agronomy 2021, 11, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semagn, K.; Henriquez, M.A.; Iqbal, M.; Brûlé-Babel, A.L.; Strenzke, K.; Ciechanowska, I.; Navabi, A.; N’Diaye, A.; Pozniak, C.; Spaner, D. Identification of Fusarium Head Blight Sources of Resistance and Associated QTLs in Historical and Modern Canadian Spring Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slafer, G.A. Physiology of Determination of Major Wheat Yield Components. In Proceedings of the Wheat Production in Stressed Environments; Buck, H.T., Nisi, J.E., Salomón, N., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2007; pp. 557–565. [Google Scholar]

- Faris, J.D.; Zhang, Z.; Garvin, D.F.; Xu, S.S. Molecular and Comparative Mapping of Genes Governing Spike Compactness from Wild Emmer Wheat. Mol Genet Genomics 2014, 289, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.-F.; Ma, F.-F.; Zhang, J.-P.; Liu, H.; Li, L.-H.; An, D.-G. Unraveling the Genetic Basis of Grain Number-Related Traits in a Wheat-Agropyron Cristatum Introgressed Line through High-Resolution Linkage Mapping. BMC Plant Biology 2023, 23, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemati, M.; Hokmalipour, S. The Study of the Relationship Between Traits and Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight (FHB) in Spring Wheat Genotypes. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, B.; Lemmens, M.; Griesser, M.; Scholz, U.; Schondelmaier, J.; Buerstmayr, H. Molecular Mapping of Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight in the Spring Wheat Cultivar Frontana. Theor Appl Genet 2004, 109, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerstmayr, M.; Lemmens, M.; Steiner, B.; Buerstmayr, H. Advanced Backcross QTL Mapping of Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight and Plant Morphological Traits in a Triticum Macha × T. Aestivum Population. Theor Appl Genet 2011, 123, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancaspro, A.; Giove, S.L.; Zito, D.; Blanco, A.; Gadaleta, A. Mapping QTLs for Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in an Interspecific Wheat Population. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleliūnas, A.; Gorash, A.; Armonienė, R.; Tamm, I.; Ingver, A.; Bleidere, M.; Fetere, V.; Kollist, H.; Mroz, T.; Lillemo, M.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals 18 QTL for Major Agronomic Traits in a Nordic–Baltic Spring Wheat Germplasm. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanke, C.D.; Ling, J.; Plieske, J.; Kollers, S.; Ebmeyer, E.; Korzun, V.; Argillier, O.; Stiewe, G.; Hinze, M.; Neumann, K.; et al. Whole Genome Association Mapping of Plant Height in Winter Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e113287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerstmayr, M.; Buerstmayr, H. The Effect of the Rht1 Haplotype on Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Relation to Type and Level of Background Resistance and in Combination with Fhb1 and Qfhs.Ifa-5A. Theor Appl Genet 2022, 135, 1985–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, B.; Buerstmayr, M.; Michel, S.; Schweiger, W.; Lemmens, M.; Buerstmayr, H. Breeding Strategies and Advances in Line Selection for Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Wheat. Trop. plant pathol. 2017, 42, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Ponte, E.M.; Fernandes, J.M.C.; Pierobom, C.R. Factors Affecting Density of Airborne Gibberella Zeae Inoculum. Fitopatol. bras. 2005, 30, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, E.M.; Zoldan, S.M.; Zanata, M. Interactions between Temperature and Wheat Head Wetting Duration on Fusarium Head Blight Intensity. Summa phytopathol. 2023, 49, e268908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louppe, G. Understanding Random Forests: From Theory to Practice 2015.

- Goldstein, B.A.; Polley, E.C.; Briggs, F.B.S. Random Forests for Genetic Association Studies - PMC. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3154091/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Salman, H.A.; Kalakech, A.; Steiti, A. Random Forest Algorithm Overview. Babylonian Journal of Machine Learning 2024, 2024, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verges, V.L.; Lyerly, Jeanette; Dong, Y.; Sanford, D.A.V. Frontiers | Training Population Design With the Use of Regional Fusarium Head Blight Nurseries to Predict Independent Breeding Lines for FHB Traits. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.01083/full (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Thapa, S.; Gill, H.S.; Halder, J.; Rana, A.; Ali, S.; Maimaitijiang, M.; Gill, U.; Bernardo, A.; St. Amand, P.; Bai, G.; et al. Integrating Genomics, Phenomics, and Deep Learning Improves the Predictive Ability for Fusarium Head Blight–Related Traits in Winter Wheat. The Plant Genome 2024, 17, e20470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Salsman, E.; Fiedler, J.D.; Hegstad, J.B.; Green, A.; Mergoum, M.; Zhong, S.; Li, X. Genetic Mapping and Prediction Analysis of FHB Resistance in a Hard Red Spring Wheat Breeding Population. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Luo, P.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, H. Controlling Fusarium Head Blight of Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.) with Genetics. ABB 2011, 02, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulthess, A.W.; Zhao, Y.; Longin, C.F.H.; Reif, J.C. Advantages and Limitations of Multiple-Trait Genomic Prediction for Fusarium Head Blight Severity in Hybrid Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). Theor Appl Genet 2018, 131, 685–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, L.; Akdemir, D.; Girard, A.-L.; Neumayer, A.; Reddy Nannuru, V.K.; Shahinnia, F.; Stadlmeier, M.; Hartl, L.; Holzapfel, J.; Isidro-Sánchez, J.; et al. Leveraging Trait and QTL Covariates to Improve Genomic Prediction of Resistance to Fusarium Head Blight in Central European Winter Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Amores, J.; Michel, S.; Löschenberger, F.; Buerstmayr, H. Dissecting the Contribution of Environmental Influences, Plant Phenology, and Disease Resistance to Improving Genomic Predictions for Fusarium Head Blight Resistance in Wheat. Agronomy 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trait | χ² | df | ε2 | Residual portion | p-value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE_2023 | 636.16 | 331 | 0.92 | 0.08 | 1.64E-21 | *** |

| AE_2025 | 485.01 | 331 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 6.67E-08 | *** |

| AL_2022 | 833.00 | 331 | 0.76 | 0.24 | 4.31E-45 | *** |

| AL_2023 | 2379.07 | 331 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 5.4E-306 | *** |

| PH_2022 | 924.39 | 331 | 0.89 | 0.11 | 1.59E-57 | *** |

| PH_2023 | 1396.69 | 331 | 0.64 | 0.36 | 1.1E-130 | *** |

| SL_2022 | 1853.26 | 331 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 1.2E-209 | *** |

| SL_2023 | 1977.72 | 331 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 5E-232 | *** |

| S/S_2022 | 1701.48 | 330 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 3.9E-183 | *** |

| S/S_2023 | 1798.45 | 331 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 7E-200 | *** |

| SD _2022 | 1434.12 | 331 | 0.42 | 0.58 | 6.5E-137 | *** |

| SD_2023 | 1202.78 | 331 | 0.24 | 0.76 | 3.2E-99 | *** |

| DH_2022 | 586.91 | 331 | 0.77 | 0.23 | 1.56E-16 | *** |

| DH_2023 | 604.52 | 331 | 0.82 | 0.18 | 2.92E-18 | *** |

| DF_2022 | 526.93 | 331 | 0.59 | 0.41 | 3.8E-11 | *** |

| DF_2023 | 584.47 | 331 | 0.76 | 0.24 | 2.67E-16 | *** |

| FHB severity 2022 | 4730.33 | 330 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0 | *** |

| FHB severity 2023 | 3815.31 | 331 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0 | *** |

| Traits | 2022 | 2023 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | CV | Mean | SD | CV | |

| AE | 3.87* | 0.62* | 16.02* | 3.16 | 0.96 | 30.43 |

| AL | 2.75 | 1.83 | 66.64 | 2.40 | 1.99 | 82.94 |

| PH | 94.62 | 8.39 | 8.87 | 70.17 | 6.54 | 9.32 |

| SL | 8.11 | 0.92 | 11.29 | 8.13 | 0.95 | 11.65 |

| S/S | 15.72 | 1.79 | 11.41 | 14.58 | 1.85 | 12.71 |

| SD | 1.95 | 0.30 | 15.18 | 1.81 | 0.27 | 14.95 |

| DF | 70.53 | 2.30 | 3.27 | 56.05 | 2.40 | 4.28 |

| DH | 67.85 | 2.03 | 2.99 | 52.76 | 2.24 | 4.24 |

| FHB Severity | 77.93 | 23.62 | 30.31 | 48.37 | 30.93 | 63.95 |

| Trait | Genotype ◊ | Year ◊ | G × E □ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ε2 | Significance | ε2 | Significance | ε2 | Significance | |

| AE | 0.30 | *** | 0.16 | *** | 0.14 | *** |

| AL | 0.53 | *** | 0.02 | *** | 0.04 | *** |

| PH | 0.14 | *** | 0.64 | *** | 0.04 | *** |

| SL | 0.42 | *** | 0.00 | ns | 0.10 | *** |

| S/S | 0.35 | *** | 0.09 | *** | 0.14 | *** |

| SD | 0.27 | *** | 0.07 | *** | 0.05 | *** |

| DH | -0.07 | ns | 0.75 | *** | 0.03 | *** |

| DF | -0.10 | ns | 0.75 | *** | 0.03 | *** |

| FHB severity | 0.24 | *** | 0.21 | *** | 0.19 | *** |

| Trait/Year | Severity 2022 | Severity 2023 | Severity average |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days to Flowering 2022 | -0.14* | -0.38*** | -0.32*** |

| Days to Flowering 2023 | -0.09ns | -0.49*** | -0.37*** |

| Days to Flowering average | -0.14* | -0.49*** | -0.40*** |

| Days to Heading 2022 | -0.14** | -0.44*** | -0.37*** |

| Days to Heading 2023 | -0.10ns | -0.50*** | -0.39*** |

| Days to Heading average | -0.15** | -0.51*** | -0.43*** |

| Plant Height 2022 | 0.08ns | -0.07ns | -0.01ns |

| Plant Height 2023 | -0.04ns | -0.09ns | -0.12* |

| Plant Height average | 0.01ns | -0.12* | -0.08ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).