1. Introduction

With the rise of internalizing problems, poor mental health among children and adolescents is a substantial public health concern. Internalizing problems in childhood primarily involves anxious and depressive symptoms [

1]. Internalizing symptoms often stem from negative self-directed behaviors aimed inwardly towards oneself [

2]. An example of this could be children’s inability to self-regulate when faced with a worrying or saddening situation, leading them to catastrophize the situation, put blame towards themselves, and engage in negative self-talk [

3]. If these symptoms continue overtime, they could reach diagnostic criteria for anxiety and depressive disorders [

4].

Anxiety is one of the most common mental health issues among children and adolescents [

5]. It is often categorized as feelings of prolonged feelings of tension and worry surrounding future events [

6]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 7.1% of children and adolescents ages 3-17 have been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder [

7]. If severe, anxiety symptoms can negatively interfere with day-to-day functioning, including (but not limited to) work performance, academic achievement, and social relationships [

6,

8]. Of the children and adolescents with anxiety symptoms severe enough to be diagnosable, 80% do not get treatment as anxiety symptoms are often minimized and ignored by primary agents such as parents [

9].

Depression is also one of the most common mental health issues among children and adolescents [

7]. It is often categorized as prolonged extreme sadness and despair [

10]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 3.2% of children and adolescents ages 3-17 have been diagnosed with an depressive disorder [

7]. If severe, depressive symptoms can interfere with day-to-day functioning, including (but not limited to) work performance, academic performance, and social relationships [

11]. Of the children and adolescents with depressive symptoms severe enough to be diagnosable, 60% do not get treatment [

12,

13]. Similar to anxiety, internalized depressive symptoms often do not get noticed which can lead to unresolved symptoms and worse outcomes [

3]. It is quite common to be diagnosed with both an anxiety and depressive disorder; in fact, nearly half of people diagnosed with depression have a comorbid anxiety diagnosis [

12].

Given the rise of internalizing problems among children and adolescents, parents play an increasingly important role in affecting how their children develop into adolescence and beyond [

14]. Being a parent, although rewarding at times, can be difficult. Roughly one-in-four (41%) of parents report that being a parent is tiring, and 29% report that being a parent is stressful [

15]. When parents are stressed, the ways they respond emotionally towards their child can be negatively impacted [

16]. When parents are under stress and their children are around, some may display healthy emotional regulation skills, which have been shown to contribute to fewer internalizing problems in children [

17]. On the other hand, some may display maladaptive emotional regulation skills which could contribute to hostile family interactions that promote more internalizing problems in children [

17,

18]. Parents with difficulties regulating their emotions often engage in negative parenting behaviors [

17] which can include showing aggravation and verbal aggression towards their children.

Parental aggravation is defined as feelings of frustration and annoyance with tainted perceptions of their children stemming from the high demands of being a parent [

19]. From a 1997 sample of American family households conducted by the National Survey of America’s Families (NSAF), 9% of children nationally lived with a parent who had reported feeling highly aggravated [

20]. Harshness and anger are also common traits of parental aggravation, which can manifest into stained parent-child relationships and poorer developmental trajectories in children, including an increase in internalizing symptoms [

2,

21,

22].

Verbal aggression is defined as repetitive harmful verbalized behaviors which are commonly unprovoked [

23]. Verbal aggression, which could be due to parental aggravation, can take the forms of insulting, swearing, and/or threatening [

24]. From surveying 3,346 American parents, 63% reported one or more instances of verbal aggression towards their children [

25]. In addition, it was found that children who endured parental verbal aggression exhibited higher rates of physical aggression, delinquency, and interpersonal issues [

25]. With this insight, the role of parental aggravation and subsequent verbal aggression in child wellbeing needs to be further addressed and studied.

Previous developmental studies have found that individuals who have high internalizing symptoms during childhood are likely to experience a continuation of these problems going into adolescence [

26]. Consequences of these trajectories include interpersonal issues, substance abuse, poorer physical health, and worsened financial stability [

27,

28]. With these negative continuous trends, the question arises about who and what influences children to experience these internalizing problems at different severity levels, with a specific interest surrounding anxiety and depression symptoms. Research emphasis is put on family factors, with maternal aggravation promoting verbal aggression, therefore putting them at a higher risk for developing internalizing symptoms [

2].

Despite empirical studies pertaining to negative parenting and its effects on children, there is limited research surrounding how maternal aggravation could transform into verbal aggression towards their children, which could then lead to an increase in childhood internalizing symptoms. Equally important, there are no known studies pertaining to the reciprocal processes of how children who exhibit internalizing symptoms could influence their parents to exhibit verbal aggression, which could then transform into aggravation towards them. Taken together, this study aims to study the longitudinal associations among maternal aggravation, verbal aggression, and internalizing problems from childhood to adolescence and to further explore the possible reciprocal effects between these maternal behaviors and child wellbeing.

1.1. Theoretical Perspectives

Poor parental attitudes and behaviors can be detrimental to child outcomes regarding psychological and social wellbeing [

20,

29]. Family socialization theory [

30] applies to this phenomenon. In broad terms, socialization refers to how individuals are taught characteristics needed to function in society through interacting with and observing others; these characteristics can involve behaviors, values, standards, and motives [

31]. From a human development standpoint, socialization begins with parent-child relationships. Families (deemed as primary agents) have the first and strongest contact with the child [

32,

33]. As children often adopt characteristics from their strongest contact, these first contacts are critical regarding socioemotional development. Parents have direct influences over their children’s self-regulation, emotion, thinking, and behavior [

34]. According to Bandura [

35], most human thought processes and behaviors are learned through those surrounding them; therefore, through observing and interacting with parents, children could develop either positive or negative thought and behavior processes depending on the socialization provided by their parents.

Poor parental socialization can bring harmful consequences to children including a deficit in socioemotional development. Since family socialization theory is loosely based on social learning theory [

35], we can attest that children learn and model behavior shown from their parents. For example, children who observe their parents responding maladaptively to stress learn that showing excessive aggravation is acceptable, resulting in them adopting those poor emotional regulation techniques when feelings of aggravation arise [

30]. This is critical, as children with poorer emotional regulation skills are at higher risks for developing internalizing symptoms [

36]. This is further supported in the literature, as Cabecinha-Alati and O’Hara found that adults whose parents were unsupportive (i.e., giving minimizing and/or punitive responses), when displaying negative emotions such as sadness and anxiety during childhood have higher overall anxiety in adulthood due to their use of maladaptive emotional regulation strategies learned from their parents [

37]. Furthermore, Seddon et al. found that children of parents who were unsupportive towards them when dealing with difficult emotions experienced heightened depressive symptoms [

38]. Children of parents who exhibit high levels of aggravation are also less well-adjusted and experience more negative outcomes regarding social wellbeing [

29], stressing the importance of proper family socialization from a young age.

Family systems theory (FST) [

39] emphasizes that families are interdependent units where all its members are connected emotionally [

40]. All members within the family are often affected by other members’ thoughts, feelings, and/or actions. When one family member displays feelings such as distress, other family members within that unit may feel increasingly distressed as well [

39]. Parents tend to be one of the most influential members emotionally to the family unit, especially in relation to children’s mental wellbeing [

8]. Based on family projection processes (FPP) [

41] which is a component of FST, parents who provide warm, non-distressing environments for their children help minimize risks of their children developing mental health issues. In comparison, parents who provide hostile, distressing environments for their children, perhaps through showing aggravation and verbal aggression, increase the risks of their children developing internalizing symptoms such as anxiety and depression [

1]. On the other hand, problems in children could also lead to negative reactions from their parents, including aggravation and aggression. This could be due to spillover effects between the parents and their children regarding poor parental functioning and poor child functioning [

40,

41].

1.2. Parental Aggravation and Child Internalizing ...

According to parents, feeling aggravated stems mostly from the stress parenthood brings [

19]. This is especially the case in low-income families. According to Moore and Ehrle, parents are more likely to report feeling aggravated when living in a low-income household (14%) and/or when being a single parent (16%) [

20]. These statistics show that not only does being a parent alone contribute to parental aggravation, but external stressors such as financial strain and partner dissolution also have an impact on parental aggravation [

29].

When a parent expresses aggravation towards their children, the children may feel responsible and blame themself for their parents’ negative emotions and, in turn, attempt to mitigate their parents’ distress [

41]. These acts make children feel more heightened and sensitive to their parents’ dysregulation and increase their vulnerability to develop internalizing symptoms [

40,

41]. Related research has shown that parental negativity (e.g., hostility) has been linked to putting children at higher risks for internalizing issues [

42]. Suh and Luthar [

43] studied a sample from 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health which involved a sample of approximately 36,000 caregivers in the U.S. Their study partly aimed at examining what predicts childhood internalizing symptoms, with emphasis on parental aggravation and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) (i.e., parental separation and low socioeconomic status). Both researchers found that internalizing issues were more prominent when parents reported being aggravated [

43]. In addition, parental aggravation had larger effects on child maladjustment than ACEs [

43], emphasizing how important parenting attitudes and behaviors are for child wellbeing.

1.3. Bidirectional Effects

When examining childhood internalizing symptoms longitudinally using both family systems and socialization theories, we can presume that parent-child dyads have reciprocal influences [

44]. Not only does displaying parental aggravation impact children in developing internalizing symptoms, but their internalizing symptoms impact their parents in displaying verbal aggression brought on by feelings of aggravation. Regarding parent effects, parents who act and/or respond to stressors around their children with a positive, calm demeanor are likely to see similar responses in their children when faced with a stressor [

45] and thus, experience positive family functioning. In comparison, parents who act and/or respond to stressors around their children with a negative, reactive demeanor (perhaps, through verbally aggressing) are likely to see similar responses in their children [

45]. Then, when children respond negatively to future stressors (i.e., through internalizing symptoms), parental aggravation continues, continuing the maladaptive cycle.

Regarding child effects, children dealing with internalizing symptoms could lead to an increase in stress and dysfunction for all family members, but mostly the parents [

43]. This increase of stress and dysfunction creates an influx of parental aggravation behaviors towards children, which can include the usage of verbal aggression. In response to these behaviors, the children could exhibit more internalizing symptoms which dysregulates the family system and further aggravates the parents; thus, creating an everlasting cycle of poor wellbeing for children and their families. Taken together, it is possible that not only do parental aggravation influence anxiety symptoms in children, but their anxiety symptoms can also influence parental aggravation through verbal aggression.

1.4. Verbal Aggression as a Mediating Factor

Parents may display their aggravation through projecting anger towards their children and/or through invalidating their negative emotions [

14,

16]. This suggests that aggravated parents may have an increased proclivity to act verbally aggressive towards their children which can involve yelling, threatening, insulting, and/or criticizing [

14]. Yang et al. found there is a high correlation between parental aggravation and child abuse, which can include verbal aggression [

46]. Since parental verbal aggression is associated with increased anxiety and depression levels in children [

47], it is possible that parental aggravation leads to verbal aggression towards their children, which then results in children experiencing heightened internalizing symptoms.

Since parents of children with internalizing disorders experience higher stress [

15], those stressed parents may act verbally aggressive towards their children as a form of coping with aggravation, which unintentionally creates an ongoing cycle of being aggravated towards their children, verbally aggressing, and then their children experiencing heightened anxious/depressive symptoms. It is also crucial to acknowledge the bidirectional effects that internalizing symptoms in childhood have on parental aggravation; since it can be stressful for parents to watch their children suffer with anxiety and/or depression symptoms, those parents may start verbally aggressing towards their child(ren) (i.e., insulting, invalidating, etc.) due to feeling aggravated.

1.5. Child Gender

Previous literature has suggested that girls have higher prevenances of developing internalizing symptoms compared to boys [

48]. Further, child gender may influence responses to maternal aggravation. Karababa [

49] studied the association between parental hostility and adolescent emotional problems through surveying approximately 1,500 adolescents and their cohabiting parents. Karababa found that, when exposed to maternal hostility, adolescent girls reported more emotional problems than boys did. It is possible that children may be influenced more by the parent who shares their same gender. Referring back to FST, children often learn how to cope with stressful situations through observing their parents; therefore, children may be more inclined to adopt the same response to stress as their same-sex parent, whether maladaptive or not. Based on the literature pertaining to parent-child interactions and gender, it would make sense that girls who are exposed to maternal aggravation and verbal aggression would have higher levels of internalizing symptoms.

1.6. The Present Study

Guided by the theoretical perspectives of family systems theory [

39] and socialization theory [

30], we addressed the limitations in the previous literature by examining the longitudinal and reciprocal processes of maternal aggravation to child internalizing symptoms through maternal verbal aggression. We specifically focused on a vulnerable population of low-income, single mothers and their children to get a better understanding of mental health outcomes among children growing up in these conditions, which could inform intervention programs for better assisting these low-income, single mothers and their children to mitigate potential poor parenting practices and child mental health outcomes.

Using a large, longitudinal, national dataset, we hypothesized that there would be bidirectional influences of maternal aggravation and child internalizing symptoms from childhood to adolescence (H1). We further hypothesized that maternal verbal aggression would mediate the reciprocal associations (H2). Based on the literature, child gender would be considered in examining the processes.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

Table 2 presents the correlations among maternal aggravation, verbal aggression, and child internalizing symptoms across waves III through VI. The correlations suggested that maternal aggravation, verbal aggression, and child internalizing symptoms were correlated within waves. For example, the correlation between maternal aggravation and verbal aggression in Wave III was .19 (

p < .01), and the correlation between verbal aggression and child internalizing symptoms in Wave III was .17 (

p < .01). There were also significant correlations across waves; for example, the correlation between maternal aggravation in Wave III and verbal aggression in Wave IV was .19 (

p < .01), and the correlation between maternal verbal aggression in Wave IV and child internalizing symptoms in Wave V was .10 (

p < .01). The correlation table also shows significance in reciprocal relations between child internalizing symptoms and maternal verbal aggression and aggravation cross waves. For example, the correlation between child internalizing symptoms in Wave III and maternal verbal aggression in Wave IV was .11 (

p < .01). Child internalizing symptoms in Wave III were also correlated with maternal aggravation in Wave VI (.14,

p < .01). These correlations showed preliminary support for both our hypotheses.

3.2. Hypotheses Testing

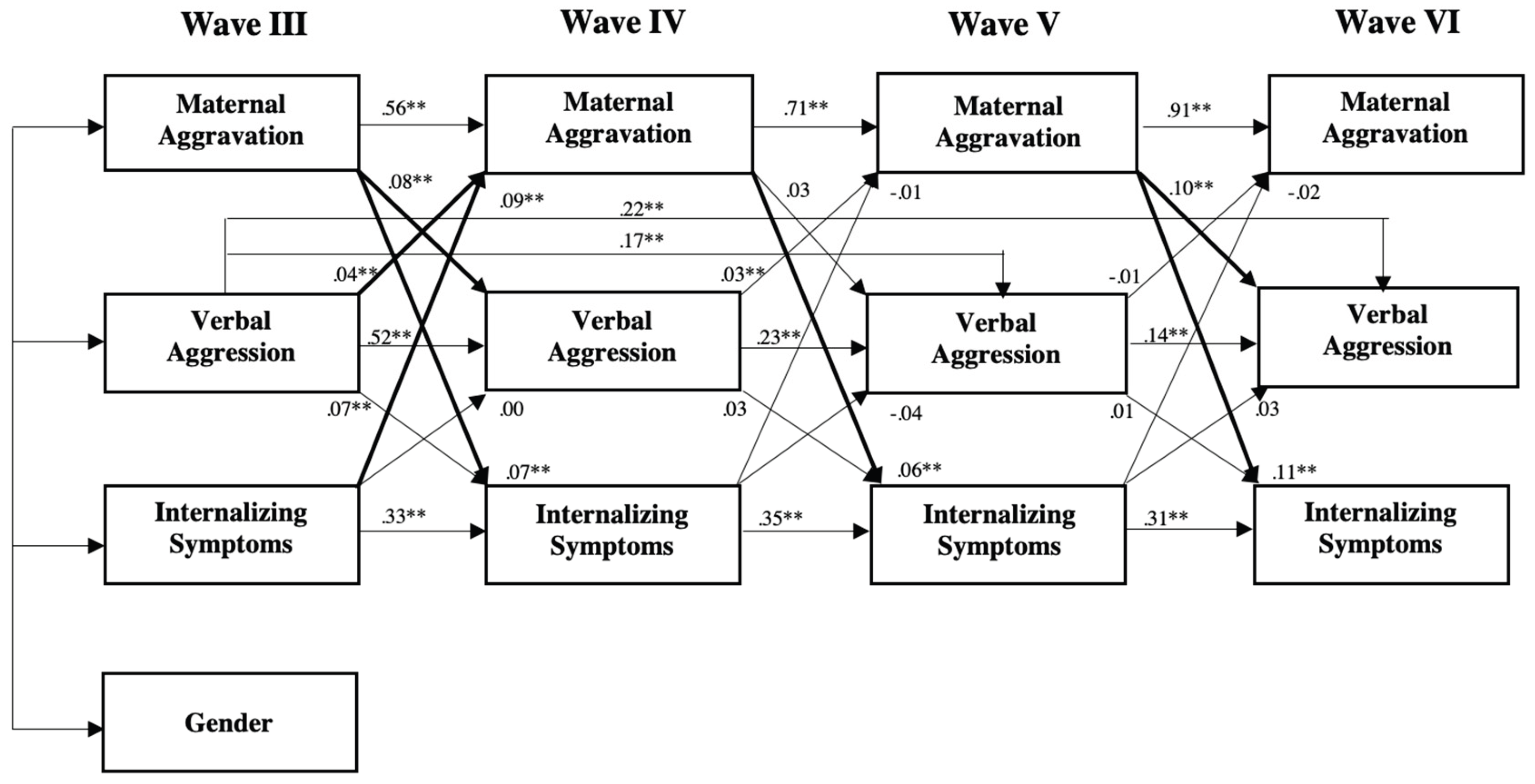

The cross-lagged autoregressive model was constructed so that each variable was specified for each wave. Residuals were correlated among the variables within each timepoint from Wave III through Wave VI. Standardized path coefficients were reported. Overall, this model showed a relatively good fit. χ2 (25) = 72.96, p = .000; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .02, p-close = 1.00. All stability paths were significant (e.g., = .56 from maternal aggravation wave III to Wave IV). There were two significant paths between non-adjacent constructs - from verbal aggression Waves III to V (= .17, p < .01) and to VI ( = .22, p < .01). We now turn to the cross-lagged paths of hypotheses testing.

To test the portion from maternal aggravation to child internalizing symptoms through verbal aggression, Wave III maternal aggravation had a significant path to Wave IV verbal aggression ( = .08, p < .01), and Wave V maternal aggravation had a significant path to Wave VI verbal aggression ( = .10 p < .01). Wave IV maternal aggravation was not significant to Wave V verbal aggression ( = .03, ns). Continuing from verbal aggression to child internalizing problems, Wave III verbal aggression had a significant path to Wave IV internalizing symptoms ( = .07 p < .05), but Wave IV verbal aggression to Wave V internalizing symptoms ( = .03, ns) and Wave V verbal aggression to Wave VI internalizing symptoms (= .01, ns) were not significant. The direct paths from maternal aggravation to internalizing problems at each subsequent waves, however, were all significant (.07, .06, and .11, respectively, p < .01 for all three paths). This finding suggested that maternal aggravation at Waves III and V was predictive of verbal aggression at the subsequent wave, and verbal aggression at Wave III was predictive of child internalizing problems at Wave IV. Maternal aggravation was directly predictive of child internalizing problems at all waves. Taken together, parent effects from maternal aggravation to child/adolescent internalizing symptoms was generally supported but mediation through maternal verbal aggression was not supported.

To test the portion from child internalizing problems to maternal aggravation through verbal aggression, Wave III child internalizing symptoms did have a significant path with Wave IV maternal aggravation ( = .09, p < .01), but not through verbal aggression. No other paths from child internalizing problems to maternal aggravation or verbal aggression were significant. This suggested that the child effects hypothesis and the mediating mechanisms were not supported. Within maternal aggravation and verbal aggression, verbal aggression at Wave III was significantly related to maternal aggravation at Wave IV (= .04, p < .01) and verbal aggression at Wave IV was significantly related to maternal aggravation at Wave V ( = .03, p = .05), suggesting some reciprocity within maternal attitudes and behaviors.

Although gender (1 = male, 2 = female) was not shown in the cross-lagged autoregressive model, it was included in the model. Four significant paths were found and included. Specifically, gender was significantly related to verbal aggression at Wave IV (= -.04, p < .05) and Wave VI (= -.06, p < .01), suggesting lower levels of maternal aggravation and verbal aggression toward girls. The path from gender to internalizing problems at Wave V ( = -.04, p < .05) and Wave VI (= .07, p < .01) sent mixed messages.

4. Discussion

Within recent years, there has been a drastic rise in internalizing problems in children; so much so, that this increase has been deemed a public health concern. Consequential future outcomes can occur for children who reach diagnostic criteria for an internalizing disorder, including poor work performance, academic achievement, and social relationships [

8,

11]. With anxious and depressive symptoms being the most common internalizing issues among children [

5,

7], family researchers and practitioners have been questioning what causes these increases in childhood internalizing symptoms. As parents have major influences on child psychoemotional wellbeing [

14], researchers have been looking into maladaptive parenting behaviors for more insight.

This current study expands the current literature on the effects of negative parenting attitudes (i.e., aggravation) and behaviors (i.e., verbal aggression) on child wellbeing regarding the development of internalizing symptoms, as well as possible reciprocal effects. Based on the theoretical frameworks of family systems theory and family socialization theory, along with related literature, we proposed longitudinal and bidirectional influences of maternal aggravation and child internalizing symptoms (H1) and that maternal verbal aggression would mediate those associations (H2). With a sample of 4,898 mothers and children from low-income families from the national dataset of FFCWS, results from our cross-lagged autoregressive model provided some support to the hypotheses, but also mixed findings.

4.1. “Parent Effects” on Child Internalizing Symptoms

Theories and previous literature have linked negative parenting attitudes with the development of internalizing symptoms in children. Based on the works of Moore and Ehrle [

20], parents are more likely to report feeling aggravated when living in a low-income household (14%) and/or when being a single parent (16%), consistent with our current sample. With this knowledge, parents may show aggravation towards their children as a maladaptive way of coping with their external stressors. Researchers have also stated that internalizing symptoms were more prominent among children whose parents act aggravated and/or hostile towards them [

42,

43]. These findings are consistent with our hypothesis that aggravation from mothers is linked to childhood internalizing symptoms (i.e., “parent effects”).

Our cross-lagged autoregressive model found significant, direct paths of maternal aggravation to child internalizing symptoms across all waves, supporting the parent effects portion of our H1 while highlighting the important role of maternal aggravation. Our findings showing direct influences of maternal aggravation to child internalizing symptoms is consistent with the theoretical framework of FST [

39]. For instance, displays of parental aggravation can disrupt the family unit, making children feel more heightened and sensitive to their parents’ dysregulation; thus, increasing their vulnerability to develop internalizing symptoms [

40,

41]. “Parent effects” are also consistent with family socialization theory [

30]. For instance, children who observe aggravated behaviors from their parents may model those same poor emotional regulation skills. This is crucial, as poor emotional regulation skills are linked to childhood internalizing symptoms [

30,

36]. Overall, both theories supported the direct effects from H1 in this current study. Based on both theories and previous literature, it is suggested that maternal aggression influences internalizing symptoms from early childhood to adolescence, emphasizing the importance of researching the long-term effects of maladaptive mothering processes on child anxiety and depression. This suggests that children may have lower risks of developing internalizing symptoms when their mothers display positive attitudes towards them versus negative attitudes.

4.2. “Child Effects” on Maternal Aggravation

Besides maternal aggravation leading to child internalizing symptoms, the current literature provided limited evidence that there could be possible reciprocal effects (i.e., “child effects”) of internalizing symptoms to maternal aggravation [

44] at least during early stage of child development. Minkin and Horowitz [

15] found that parents of children with internalizing disorders experience higher stress. In addition, Woodman et al. [

57] found a correlation between child internalizing symptoms and high stress in parents, which can turn into aggravation.

In our study, we found limited evidence of “child effects” because child internalizing symptoms were found to be directly related to maternal aggravation only during earlier stages of development (i.e., Wave III, when the child was three years old). The implications could be that children have greater influences on maternal wellbeing when younger compared to when they are older. Since younger children have higher support needs and sometimes experience unstable emotions, responding to such demands, mothers may experience heightened stress.

4.3. Verbal Aggression as a Mediator

Research has suggested that aggravated parents may have an increased proclivity to act verbally aggressive towards their children [

14,

16]. In this case, verbal aggression is viewed as an negative, outward response to aggravation. Verbal aggression, which includes yelling, threatening, insulting, and/or criticizing someone [

14] has been found to be associated with increased symptoms of anxiety and depression in children [

47]. Based on the ongoing literature, the current study proposed that verbal aggression mediated the linkage between maternal aggravation influencing child internalizing symptoms, and vice-versa.

The findings from this study, however, did not support this hypothesis. Even though our model revealed significant paths from child internalizing problems at Wave III to maternal aggravation at Wave IV and from maternal aggravations at Waves III and IV to subsequent aggravation, mediation paths were not formed by these significant paths, and therefore, mediation hypotheses were not supported. In other words, our findings support direct effects from maternal aggravation to child internalizing symptoms, but not through verbal aggression. These null findings could also be due to methodological restrictions, such as the specific sample and the measurements. These are further discussed in the limitations section.

4.4. Gender as a Covariate

There were some interesting findings about gender differences. Girls were associated with lower levels of maternal verbal aggression. This could be due to a plethora of reasons; perhaps, because girls were viewed to be more emotional compared to boys [

58] and received less verbal aggression from parents to spare their feelings. Alongside this finding, girls were more positively associated with internalizing symptoms at Wave VI. This was not a surprising find, as the literature did state that girls do have a higher prevalence of developing internalizing symptoms compared to boys [

48]. The negative association between gender and internalizing problems at Wave V, however, was inconsistent with the literature.

4.5. Practical Contributions

Our findings were important and supplemental to the ongoing literature about parental behaviors on child wellbeing. This study bridged the literature gap of examining maternal aggravation on child internalizing symptoms. As childhood internalizing issues are becoming more prevalent, this study could help navigate family practitioners of all domains (i.e., physicians, psychologists, etc.) in understanding that sometimes, the onset of child internalizing symptoms starts within the home. With this understanding, more practitioners could consider adopting a stronger family systems lens when providing treatments and/or interventions. Overall, our findings suggested stronger evidence of “parent” effects than “child” effects and direct effects than mediating effects.

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the strengths of this longitudinal study with a national dataset, there were a few limitations from this study which must be addressed. First, the numbers of items were inconsistent across the four waves in some measures. To measure internalizing symptoms, Wave III used eight items, Wave IV used 14 items, Wave V used 13 items, and Wave IV used six items from the CBCL [

24]. Two items remained consistent throughout all four waves (i.e., [child] is nervous, high strung, [or tense],” and “[child] is too fearful [or anxious]”); however, only using those two items would not cover depressive symptoms, only anxious symptoms. It seemed as though the unequal representation of items was due to FFCWS needing items to maintain age-appropriateness across waves (e.g., “[child] clings to adults” in Wave III would not be as applicable in Wave IV). Although the choice was understandable given the nature of this longitudinal dataset, validity could be difficult to test. There also were some inconsistencies among items when measuring for verbal aggression through the CTSPC [

53]. Wave III through Wave V used five of the same items to access verbal aggression, while Wave VI combined two items from previous waves (i.e., “shouted, yelled, or screamed at him/her” and “swore or cursed at him/her”) to create one item (i.e., “shouted, yelled, screamed, swore or cursed”). Not only were these measurement items inconsistent, but using a single item to test verbal aggression could be problematic to the validity of the current study. These issues in measurements could be a reason for not finding limited evidence for “child” effects and mediation effects. Future studies should employ measures that are consistent in measurement items across waves, and acquire a sufficient number of items.

Second, it should be noted that all measures were reported by mothers. For example, even though it is reasonable to have mother reports of CBCL on young children’s problems and it is necessary to keep the same reporters across waves in a longitudinal study, when mothers reported the prevalence of internalizing symptoms seen in their children, there is a chance of reporting error or bias [

59]; especially in internalizing symptoms where symptoms could be masked and cannot be easily observed. Despite mothers being around their children often, it could be difficult to know what their children are internally going through. As for self-reports of maternal aggravation and verbal aggression, mothers may feel inclined to report minimal rates of aggravation towards their children due to social desirability [

60]. This could also apply to verbal aggression, which is perhaps why there were no mediating effects found. Implications could be that mothers do not want to admit to inflicting abuse onto their children, whether psychological or not. Future studies should consider using multi-informant methods and including observational data.

Third, this study only considered the potential mediating effect by maternal verbal aggression. The null finding on mediation may also suggest that there could be other possible mediating mechanisms. Researchers should look into other possible mediators between maternal aggravation and child internalizing symptoms. For instance, mothers may display their feelings of aggravation in other ways than verbally aggressing. Thus, other maladaptive maternal behaviors such as physical aggression may serve as a better mediator.

Fourth, due to the complexity of the cross-lagged autoregressive model, this study only considered gender as a covariate. Future studies should explore the role of other possible theory-driven covariates, such as mothers’ relationship partner status and living arrangement (e.g., whether the mother is cohabiting with a partner could influence child outcomes through having another supportive parental figure in the household). The potential moderating roles of these factors should also be considered.

In addition, future studies could further take advantage of the rich FFCWS dataset. For example, future studies could expand the dependent variables to include both child internalizing symptoms and externalizing symptoms. This would allow for researchers to get a thorough understanding of which childhood psychoemotional difficulties are associated with maternal maltreatment. Lastly, FFCWS recently published results from Wave VII (age 22). Researchers who wish to continue studying childhood outcomes past adolescence and into young adulthood are encouraged to view that dataset.