Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

14 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Attachment and Phubbing

1.2. Materialism

1.3. Attachment, Materialism, and Phubbing

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Design

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Attachment

2.3.2. Materialism

2.3.3. Enacted Phubbing

2.3.4. Perceived Phubbing

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. Correlations

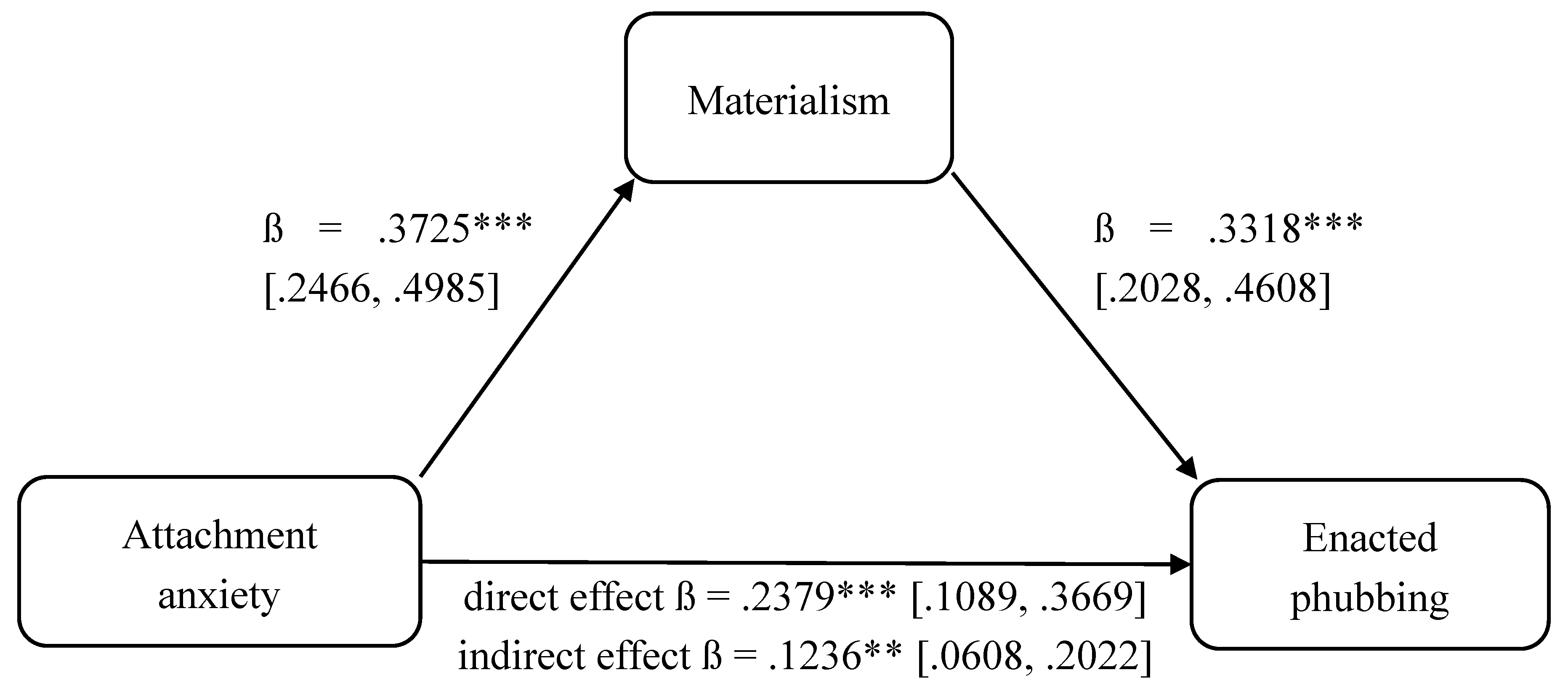

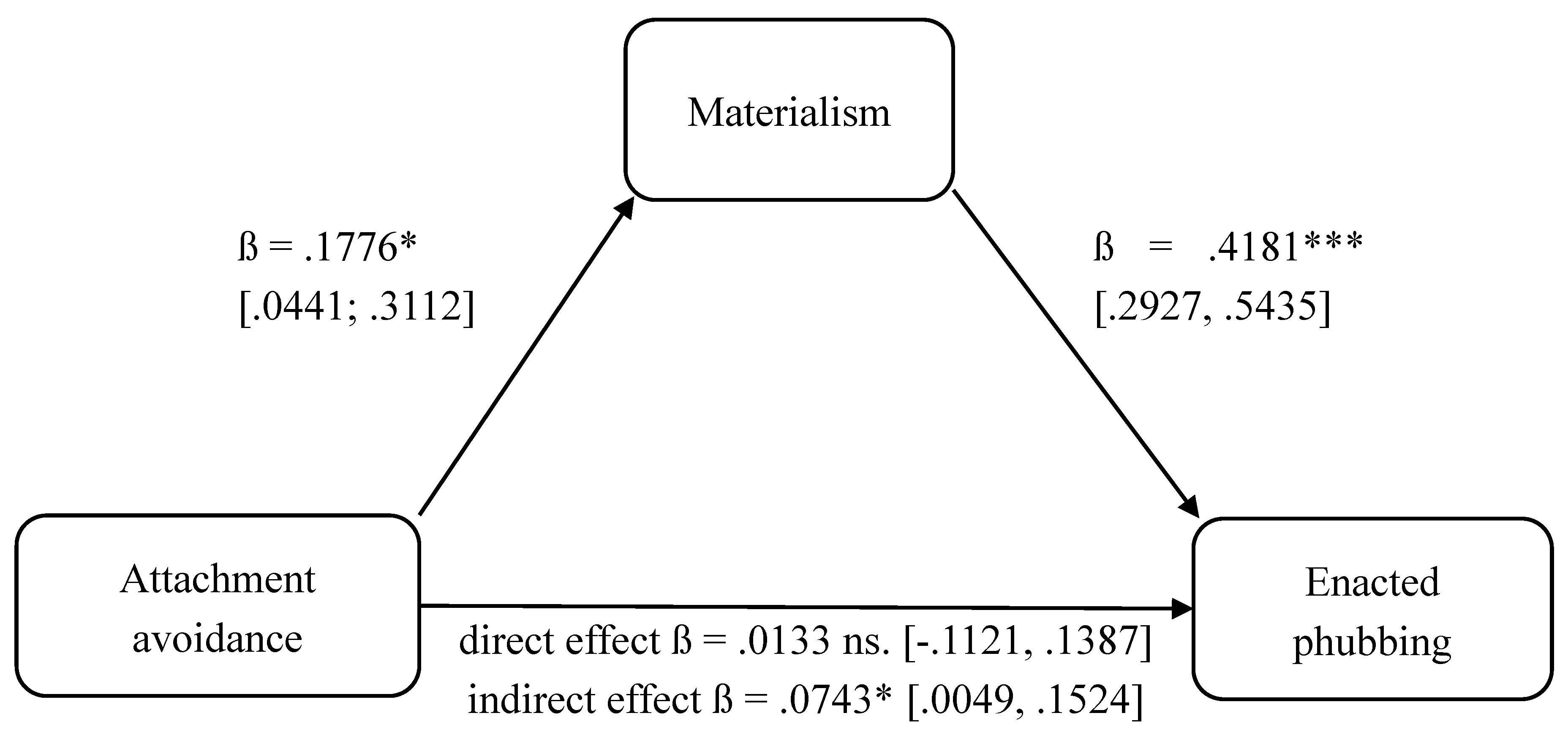

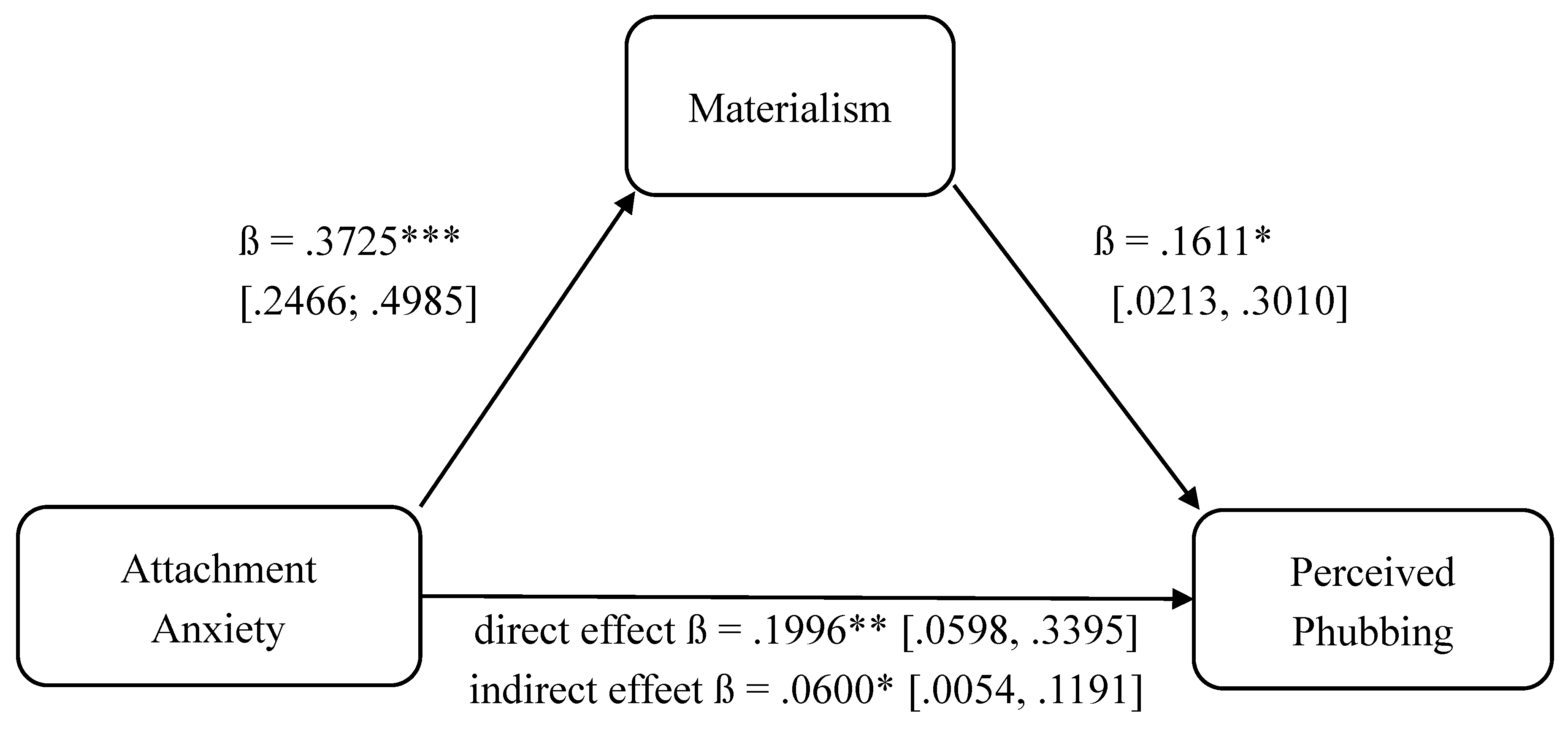

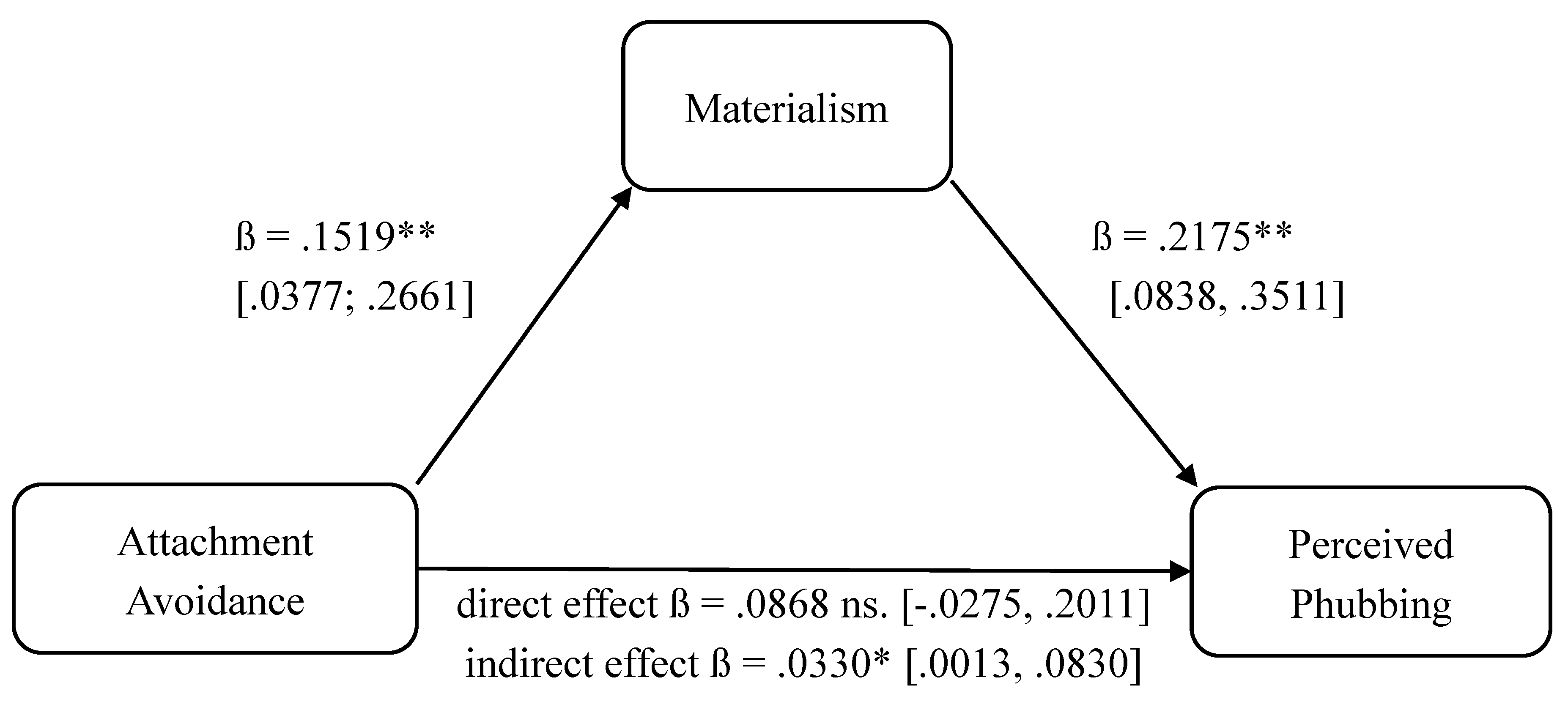

3.3. Mediation Analyses

3.4. Replicabilty and Post-Hoc Power

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

Data availability

Ackowledgments

Declaration of Interest Statement

Appendix A: Translation of the Phubbing Scale & the pPhubbing Scale

| Original Items | German Version | |

| 1. | My eyes start wandering on my phone when I’m together with others. | Wenn ich mit anderen zusammen bin, beginnt mein Blick zu meinem Handy zu wandern. |

| 2. | I am always busy with my mobile phone when I’m with my friends. | Ich bin immer mit meinem Handy beschäftigt, wenn ich mit meinen Freund/innen zusammen bin. |

| 3. | People complain about me dealing with my mobile phone. |

Andere beschweren sich darüber, dass ich mich mit meinem Handy befasse. |

| 4. | I’m busy with my mobile phone when I’m with friends. |

Ich bin mit meinem Handy beschäftigt, wenn ich mit Freund/innen zusammen bin. |

| 5. | I don’t think that I annoy my partner when I’m busy with my mobile phone. |

Ich denke nicht, dass ich meine/n Partner/in damit nerve, wenn ich mit meinem Handy beschäftigt bin. |

| 6. | My phone is always within my reach. |

Mein Handy ist immer in Reichweite. |

| 7. | When I wake up in the morning, I first check the messages on my phone. | Wenn ich morgens aufwache, checke ich zuerst die Nachrichten auf meinem Handy. |

| 8. | I feel incomplete without my mobile phone. | Ohne mein Handy fühle ich mich unvollständig. |

| 9. | My mobile phone use increases day by day. | Meine Handy-Nutzung wird von Tag zu Tag mehr. |

| 10. | The time allocated to social, personal or professional activities decreases because of my mobile phone. | Die Zeit, die ich sozialen, persönlichen oder beruflichen Aktivitäten widme, nimmt aufgrund meiner Handy-Nutzung ab. |

| Original Items | German Version | |

| 1. | During a typical mealtime that my partner and I spend together, my partner pulls out and checks his/her cell phone (slight modification). |

Während einer typischen Mahlzeit, die mein/e Partner/in und ich gemeinsam verbringen, holt mein/e Partner/in sein/ihr Handy raus und überprüft es. |

| 2. | My partner places his or her cell phone where they can see it when we are together. | Wenn wir zusammen sind, platziert mein/e Partner/in sein/ihr Handy so, dass er/sie es sehen kann. |

| 3. | My partner keeps his or her cell phone in their hand when he or she is with me. | Mein/e Partner/in behält sein/ihr Handy in der Hand, wenn er/sie mit mir zusammen ist. |

| 4. | When my partner’s cell phone rings or beeps, he/she pulls it out even if we are in the middle of a conversation (slight modification). | Wenn das Handy meines Partners/meiner Partnerin klingelt oder piept, holt er/sie es heraus, auch wenn wir mitten im Gespräch sind. |

| 5. | My partner glances at his/her cell phone when talking to me. |

Mein/e Partner/in schaut auf sein/ihr Handy, während er/sie mit mir spricht. |

| 6. | During leisure time that my partner and I are able to spend together, my partner uses his/her cell phone (slight modification). | In der Freizeit, die mein/e Partner/in und ich zusammen verbringen können, nutzt mein/e Partner/in sein/ihr Handy. |

| 7. | My partner does not use his or her phone when we are talking. | Mein/e Partner/in nutzt sein/ihr Handy nicht, wenn wir uns unterhalten. |

| 8. | My partner uses his or her cell phone when we are out together. | Mein/e Partner/in nutzt sein/ihr Handy, wenn wir gemeinsam unterwegs sind. |

| 9. | If there is a lull in our conversation, my partner will check his or her cell phone. |

Gibt es eine Pause in unserem Gespräch, checkt mein/e Partner/in sein/ihr Handy. |

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. N. (1978). Patterns of attachment: a psychological study of the strange situation. Erlbaum, Lawrence.

- Al-Saggaf, Y., & MacCulloch, R. (2018). Phubbing: how frequent? Who is phubbed? In which situation? And using which apps? 39th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2018): Bridging the internet of people, data, and things, San Francisco, USA.

- Al-Saggaf, Y., MacCulloch, R., & Wiener, K. (2019). Trait Boredom Is a Predictor of Phubbing Frequency. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 4(3), 245-252. [CrossRef]

- Al-Saggaf, Y., & O’Donnell, S. B. (2019). Phubbing: Perceptions, reasons behind, predictors, and impacts. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 1(2), 132-140. [CrossRef]

- Alicke, M., Zell, E., & Guenther, C. L. (2013). Chapter Four - Social Self-Analysis: Constructing, Protecting, and Enhancing the Self. In J. M. Olson & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 48, pp. 173-234). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, X. B., & Kumashiro, M. (2019). Walking a security tightrope: relationship-induced changes in attachment security. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 121-126. [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, X. B., Kumashiro, M., Finkel, E. J., VanderDrift, L. E., & Luchies, L. B. (2014). Filling the Void: Bolstering Attachment Security in Committed Relationships. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(4), 398-406. [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, X. B., Kumashiro, M., Simpson, J. A., & Overall, N. C. (2018). Revising Working Models Across Time: Relationship Situations That Enhance Attachment Security. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(1), 71-96. [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K. J., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. Journal of personality and social psychology, 61(2), 226-244. [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. W. (2015). Culture and materialism. In S. Ng & A. Y. Lee (Eds.), Handbook of culture and consumer behavior (pp. 299-323). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Bierhoff, H.-W., & Rohmann, E. (2020). Bindung, Partnerzufriedenheit und Kultur. In T. Ringeisen, P. Genkova, & F. T. L. Leong (Eds.), Handbuch Stress und Kultur: Interkulturelle und kulturvergleichende Perspektiven (pp. 1-20). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. [CrossRef]

- Błachnio, A., & Przepiorka, A. (2019). Be Aware! If You Start Using Facebook Problematically You Will Feel Lonely: Phubbing, Loneliness, Self-esteem, and Facebook Intrusion. A Cross-Sectional Study. Social Science Computer Review, 37(2), 270-278. [CrossRef]

- Bound Alberti, F. (2018). This “Modern Epidemic”: Loneliness as an Emotion Cluster and a Neglected Subject in the History of Emotions. Emotion Review, 10(3), 242-254. [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss Volume I Attachment. Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and Loss Volume II Separation. Basic Books.

- Brailovskaia, J., Ozimek, P., Rohmann, E. & Bierhoff, H.W. (2023). Vulnerable narcissism, fear of missing out (FoMo) and addictive social media use: A gender comparison from Germany. Computers in Human Behavior, 144, 107725.

- Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46-76). Guilford Press.

- Bröning, S., & Wartberg, L. (2022). Attached to your smartphone? A dyadic perspective on perceived partner phubbing and attachment in long-term couple relationships. Computers in Human Behavior, 126, 10. [CrossRef]

- Büttner, C. M., Gloster, A. T., & Greifeneder, R. (2022). Your phone ruins our lunch: Attitudes, norms, and valuing the interaction predict phone use and phubbing in dyadic social interactions. Mobile Media & Communication, 10(3), 387-405. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Boldry, J., & Kashy, D. A. (2005). Perceptions of Conflict and Support in Romantic Relationships: The Role of Attachment Anxiety. Journal of personality and social psychology, 88(3), 510–531. [CrossRef]

- Canevello, A., & Crocker, J. (2010). Creating Good Relationships: Responsiveness, Relationship Quality, and Interpersonal Goals. Journal of personality and social psychology, 99(1), 78-106. [CrossRef]

- Carnelley, K. B., Vowels, L. M., Stanton, S. C. E., Millings, A., & Hart, C. M. (2023). Perceived partner phubbing predicts lower relationship quality but partners’ enacted phubbing does not. Computers in Human Behavior, 147, 107860. [CrossRef]

- Çelik, E., & Büyükşakar, S. (2024). Attachment Styles and Loneliness as Predictors of Phubbing amongst University Students [Sosyotelİzm’İn yordayicilari olarak baĞlanma stİllerİ ve yalnizlik]. Sakarya University Journal of Education, 14(1), 18-32. [CrossRef]

- Chang, B., Zhang, J., & Fang, J. (2023). Low self-concept clarity reduces subjective well-being: the mediating effect of materialism. Current Psychology, 43, 14751-14759. [CrossRef]

- Chang, L., & Arkin, R. M. (2002). Materialism as an attempt to cope with uncertainty. Psychology & Marketing, 19(5), 389-406. [CrossRef]

- Cho, H. J., Jin, B., & Watchravesringkan, K. T. (2016). A cross-cultural comparison of materialism in emerging and newly developed Asian markets. International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology, 6(1), 1-10.

- Chotpitayasunondh, V., & Douglas, K. M. (2016). How “phubbing” becomes the norm: The antecedents and consequences of snubbing via smartphone. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 9-18. [CrossRef]

- Chotpitayasunondh, V., & Douglas, K. M. (2018). The effects of “phubbing” on social interaction. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 48(6), 304-316. [CrossRef]

- Christopher, A. N., Drummond, K., Jones, J. R., Marek, P., & Therriault, K. M. (2006). Beliefs about one’s own death, personal insecurity, and materialism. Personality and individual differences, 40(3), 441-451. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M. S., Greenberg, A., Hill, E., Lemay, E. P., Clark-Polner, E., & Roosth, D. (2011). Heightened interpersonal security diminishes the monetary value of possessions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(2), 359-364. [CrossRef]

- D21-Digital-Index 2023/24: Jährliches Lagebild zur Digitalen Gesellschaft. (2024). https://initiatived21.de/publikationen/d21-digital-index.

- D’Arienzo, M. C., Boursier, V., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Addiction to Social Media and Attachment Styles: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(4), 1094-1118. [CrossRef]

- David, M. E., & Roberts, J. A. (2017). Phubbed and Alone: Phone Snubbing, Social Exclusion, and Attachment to Social Media. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2(2), 155-163. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2014). Autonomy and Need Satisfaction in Close Relationships: Relationships Motivation Theory. In N. Weinstein (Ed.), Human Motivation and Interpersonal Relationships: Theory, Research, and Applications (pp. 53-73). Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Destatis. (2022a). Daten aus den Laufenden Wirtschaftsrechnungen (LWR) zur Ausstattung privater Haushalte mit Informationstechnik https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Einkommen-Konsum-Lebensbedingungen/Ausstattung-Gebrauchsgueter/Tabellen/a-infotechnik-d-lwr.html.

- Destatis. (2022b, 28.04.2022). Record low of marriages and record high of births in 2021 https://www.destatis.de/EN/Press/2022/04/PE22_181_126.html.

- Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., & Kasser, T. (2014). The Relationship Between Materialism and Personal Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of personality and social psychology, 107(5), 879-924. [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H., & Isham, A. (2022). Materialistic value orientation and wellbeing. Current Opinion in Psychology, 46, 6, Article 101337. [CrossRef]

- duden online. (2024). Cornelsen Verlag GmbH. Retrieved 3.7.2024 from https://www.duden.de/node/94602/revision/1228187.

- Ergün, N., Göksu, İ., & Sakız, H. (2020). Effects of Phubbing: Relationships With Psychodemographic Variables. Psychological Reports, 123(5), 1578-1613. [CrossRef]

- Faber, R., & O’Guinn, T. (1992). A Clinical Screener for Compulsive Buying. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 459-469. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J., Wang, X., Wen, Z., & Zhou, J. (2020). Fear of missing out and problematic social media use as mediators between emotional support from social media and enacted phubbing. Addictive Behaviors, 107, 106430. [CrossRef]

- Feeney, B. (2004). A Secure Base: Responsive Support of Goal Strivings and Exploration in Adult Intimate Relationships. Journal of personality and social psychology, 87(5), 631-648. [CrossRef]

- Frackowiak, M., Hilpert, P., & Russell, P. S. (2022). Partner’s perception of phubbing is more relevant than the behavior itself: A daily diary study. Computers in Human Behavior, 134, 107323. [CrossRef]

- Frackowiak, M., Hilpert, P., & Russell, P. S. (2024). Impact of partner phubbing on negative emotions: a daily diary study of mitigating factors. Current Psychology, 43, 1835-1854. [CrossRef]

- Fraley, R. C., & Dugan, K. A. (2021). The consistency of attachment security across time and relationships. In R. A. Thompson, J. A. Simpson, & L. J. Berlin (Eds.), Attachment: The Fundamental Questions (pp. 147-153). Guilford Press.

- Gasiorowska, A., Folwarczny, M., & Otterbring, T. (2022). Anxious and status signaling: Examining the link between attachment style and status consumption and the mediating role of materialistic values. Personality and individual differences, 190, 111503. [CrossRef]

- Ger, G., & Belk, R. W. (1996). Cross-cultural differences in materialism. Journal of Economic Psychology, 17(1), 55-77. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M., Babin, B. J., & Christensen, F. (2004). A cross-cultural investigation of the materialism construct: Assessing the Richins and Dawson’s materialism scale in Denmark, France and Russia. Journal of Business Research, 57(8), 893-900. [CrossRef]

- Harlow, H. F., & Zimmermann, R. R. (1959). Affectional Response in the Infant Monkey. Science, 130(3373), 421-432. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis a regression-based approach (Second edition ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of personality and social psychology, 52(3), 511-524. [CrossRef]

- Helm, P. J., Jimenez, T., Bultmann, M., Lifshin, U., Greenberg, J., & Arndt, J. (2020). Existential isolation, loneliness, and attachment in young adults. Personality and individual differences, 159, 109890. [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.-m., & Tsang, O. s. (2017). The role of materialism in self-disclosure within close relationships. Personality and individual differences, 111, 174-177. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, A., Gorbaniuk, O., Błachnio, A., Przepiórka, A., Mraka, N., Polishchuk, V., & Gorbaniuk, J. (2020). Mobile Phone Addiction, Phubbing, and Depression Among Men and Women: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Psychiatric Quarterly, 91(3), 655-668. [CrossRef]

- Jang, K., Park, N., & Song, H. (2016). Social comparison on Facebook: Its antecedents and psychological outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 147-154. [CrossRef]

- Jeste, D. V., Lee, E. E., & Cacioppo, S. (2020). Battling the Modern Behavioral Epidemic of Loneliness: Suggestions for Research and Interventions. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(6), 553-554. [CrossRef]

- Jie Long & Pengcheng Wang & Shuoyu Liu & Li Lei (2021). Materialism and adolescent problematic smartphone use: The mediating role of fear of missing out and the moderating role of narcissism. Current Psychology, 40:5842–5850.

- Kadylak, T., Makki, T. W., Francis, J., Cotten, S. R., Rikard, R. V., & Sah, Y. J. (2018). Disrupted copresence: Older adults’ views on mobile phone use during face-to-face interactions. Mobile Media & Communication, 6(3), 331-349. [CrossRef]

- Karadag, E., Betül Tosuntaş, Ş., Erzen, E., Duru, P., Bostan, N., Mizrak Şahín, B., Çulha, Í., & Babadag, B. (2015). Determinants of Phubbing, which is the Sum of Many Virtual Addictions: A Structural Equation Model. Journal of behavioral addictions, 4(2), 60-74. [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T. (2016). Materialistic Values and Goals. Annual review of psychology, 67(1), 489-514. [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further Examining the American Dream: Differential Correlates of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(3), 280-287. [CrossRef]

- Kemper, C. J., Beierlein, C., Bensch, D., Kovaleva, A., & Rammstedt, B. (2012). Eine Kurzskala zur Erfassung des Gamma-Faktors sozial erwünschten Antwortverhaltens: Die Kurzskala Soziale Erwünschtheit-Gamma (KSE-G). GESIS Working Papers 2012|25.

- Kroenke, K., Strine, T. W., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Berry, J. T., & Mokdad, A. H. (2009). The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 114(1), 163-173. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. Y. (2013). The role of attachment style in building social capital from a social networking site: The interplay of anxiety and avoidance. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1499-1509. [CrossRef]

- Li, T., & Chan, D. K.-S. (2012). How anxious and avoidant attachment affect romantic relationship quality differently: A meta-analytic review. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(4), 406-419. [CrossRef]

- Longmire, S. J., Chan, E. Y., & Lawry, C. A. (2021). Find me strength in things: Fear can explain materialism. Psychology & Marketing, 38(12), 2247-2258. [CrossRef]

- Maftei, A., & Măirean, C. (2023). Put your phone down! Perceived phubbing, life satisfaction, and psychological distress: the mediating role of loneliness. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 332. [CrossRef]

- Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in Infancy, Childhood, and Adulthood: A Move to the Level of Representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1/2), 66-104. [CrossRef]

- Martin, C., Czellar, S., & Pandelaere, M. (2019). Age-related changes in materialism in adults – A self-uncertainty perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 78, 16-24. [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. (2003). The Attachment Behavioral System In Adulthood: Activation, Psychodynamics, And Interpersonal Processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 53-152. [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. (2007). Boosting Attachment Security to Promote Mental Health, Prosocial Values, and Inter-Group Tolerance. Psychological Inquiry, 18(3), 139-156. [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Gal, I. (2021). An Attachment Perspective on Solitude and Loneliness. In R. J. Coplan, J. C. Bowker, & L. J. Nelson (Eds.), The Handbook of Solitude (Second ed., pp. 31-41). Wiley-Blackwell. [CrossRef]

- Miller-Ott, A., & Kelly, L. (2015). The Presence of Cell Phones in Romantic Partner Face-to-Face Interactions: An Expectancy Violation Theory Approach. Southern Communication Journal, 80(4), 253-270. [CrossRef]

- Miller-Ott, A. E., & Kelly, L. (2017). A Politeness Theory Analysis of Cell-Phone Usage in the Presence of Friends. Communication Studies, 68(2), 190-207. [CrossRef]

- Moldes, O., & Ku, L. (2020). Materialistic cues make us miserable: A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence for the effects of materialism on individual and societal well-being. Psychology & Marketing, 37(10), 1396-1419. [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. R., Turner, A., Gilbertson, C. H., Corner, G., Mendez, A. J., & Saxbe, D. E. (2021). Physical touch during father-infant interactions is associated with paternal oxytocin levels. Infant Behavior and Development, 64, 101613. [CrossRef]

- Müller, A., Smits, D. J., Claes, L., Gefeller, O., Hinz, A., & de Zwaan, M. (2013). The German version of the Material Values Scale. GMS Psycho-Social-Medicine, 10, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, E., Rohmann, E., & Bierhoff, H.-W. (2007). Entwicklung und Validierung von Skalen zur Erfassung von Vermeidung und Angst in Partnerschaften. Diagnostica, 53(1), 33-47. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, E., Rohmann, E., & Sattel, H. (2023). The 10-Item Short Form of the German Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR-G-10)—Model Fit, Reliability, and Validity. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 935. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/13/11/935.

- Noftle, E. E., & Shaver, P. R. (2006). Attachment dimensions and the big five personality traits: Associations and comparative ability to predict relationship quality. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(2), 179-208. [CrossRef]

- Noguti, V., & Bokeyar, A. L. (2014). Who am I? The relationship between self-concept uncertainty and materialism. International Journal of Psychology, 49(5), 323-333. [CrossRef]

- Norris, J. I., Lambert, N. M., Nathan DeWall, C., & Fincham, F. D. (2012). Can’t buy me love?: Anxious attachment and materialistic values. Personality and individual differences, 53(5), 666-669. [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P., Baer, F., & Förster, J. (2017). Materialists on facebook : the self-regulatory role of social comparisons and the objectification of Facebook friends. Heliyon, 3(11), e00449. [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P., Brailovskaia, J., Bierhoff, H.-W., & Rohmann, E. (2024). Materialism in social media–More social media addiction and stress symptoms, less satisfaction with life. Telematics and Informatics Reports, 13, 100117. [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, P., & Förster, J. (2021). The Social Online-Self-Regulation-Theory: A Review of Self-Regulation in Social Media. Journal of media psychology, 33(4), 181-190. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, R. A., Baker, G. A., & Truluck, C. S. (2012). Celebrity Worship, Materialism, Compulsive Buying, and the Empty Self. Psychology & Marketing, 29(9), 674-679. [CrossRef]

- Richins, M., & Fournier, S. (1991). Some theoretical and popular notions concerning materialism. Journal of social behavior and personality, 6(6), 403-414.

- Richins, M. L. (2004). The Material Values Scale: Measurement Properties and Development of a Short Form. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 209-219. [CrossRef]

- Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A Consumer Values Orientation for Materialism and Its Measurement: Scale Development and Validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 303-316. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. A., & David, M. E. (2016). My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: Partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 134-141. [CrossRef]

- Rohmann, E., Küpper, B., & Schmohr, M. (2006). Wie stabil sind Bindungsangst und Bindungsvermeidung? Der Einfluss von Persönlichkeit und Beziehungsveränderungen auf die partnerbezogenen Bindungsdimensionen. Journal of family research, 18(1), 4-26. [CrossRef]

- Rom, E., & Alfasi, Y. (2014). The Role of Adult Attachment Style in Online Social Network Affect, Cognition, and Behavior. Journal of Psychology and Psychotherapy Research, 1(1), 24-34. [CrossRef]

- Ross, L. R., & Spinner, B. (2001). General and Specific Attachment Representations in Adulthood: Is there a Relationship? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18(6), 747-766. [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, D., Karsay, K., Matthes, J., & Stevic, A. (2019). “Looking Up and Feeling Down”. The influence of mobile social networking site use on upward social comparison, self-esteem, and well-being of adult smartphone users. Telematics and Informatics, 42, 101240. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F. M., & Hitzfeld, S. (2021). I Ought to Put Down That Phone but I Phub Nevertheless: Examining the Predictors of Enacted phubbing. Social Science Computer Review, 39(6), 1075-1088. [CrossRef]

- Schokkenbroek, J. M., Hardyns, W., & Ponnet, K. (2022). Phubbed and curious: The relation between partner phubbing and electronic partner surveillance. Computers in Human Behavior, 137, 107425. [CrossRef]

- Segev, S., Shoham, A., & Gavish, Y. (2015). A closer look into the materialism construct: the antecedents and consequences of materialism and its three facets. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 32(2), 85-98. [CrossRef]

- Shrum, L. J., Chaplin, L. N., & Lowrey, T. M. (2022). Psychological causes, correlates, and consequences of materialism. Consumer Psychology Review, 5(1), 69-86. [CrossRef]

- Shrum, L. J., Wong, N., Arif, F., Chugani, S. K., Gunz, A., Lowrey, T. M., Nairn, A., Pandelaere, M., Ross, S. M., Ruvio, A., Scott, K., & Sundie, J. (2013). Reconceptualizing materialism as identity goal pursuits: Functions, processes, and consequences. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 1179-1185. [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M. J., Yu, G. B., Lee, D.-J., Joshanloo, M., Bosnjak, M., Jiao, J., Ekici, A., Atay, E. G., & Grzeskowiak, S. (2021). The Dual Model of Materialism: Success Versus Happiness Materialism on Present and Future Life Satisfaction. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16(1), 201-220. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., & Miller, C. H. (2023a). Insecure Attachment Styles and Phubbing: The Mediating Role of Problematic Smartphone Use. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2023, 4331787. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., & Miller, C. H. (2023b). Smartphone Attachment and Self-Regulation Mediate the Influence of Avoidant Attachment Style on Phubbing. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2023, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Wang, L., Jiang, J., & Wang, R. (2020). Your love makes me feel more secure: Boosting attachment security decreases materialistic values. International Journal of Psychology, 55(1), 33-41. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T. T., Carnelley, K. B., & Hart, C. M. (2022). Phubbing in romantic relationships and retaliation: A daily diary study. Computers in Human Behavior, 137, 107398. [CrossRef]

- Thyroff, A., & Kilbourne, W. E. (2018). Self-enhancement and individual competitiveness as mediators in the materialism/consumer satisfaction relationship. Journal of Business Research, 92, 189-196. [CrossRef]

- Trivers, R. L. (1971). The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism. The Quarterly review of biology, 46(1), 35-57. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M. A., Hassan, M., Siddique, H. M. A., & Mehar, R. (2020). A Quantitative Research: Exploring Factors Influencing Purchase Intention for Expensive Smart Phones. International Journal of Accounting Research, 5(1), 27-36.

- Vanden Abeele, M. M. P., Antheunis, M. L., & Schouten, A. P. (2016). The effect of mobile messaging during a conversation on impression formation and interaction quality. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 562-569. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. (2020). On Increasing Divorce Risks. In D. Mortelmans (Ed.), Divorce in Europe: New insights in trends, causes and consequences of relation break-ups (Vol. 21, pp. 37-61). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., Nie, J., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Zhao, F., Xie, X., Lei, L., & Ouyang, M. (2020). How are smartphones associated with adolescent materialism? Journal of Health Psychology, 25(13-14), 2406-2417. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Chen, W.-F., Hong, Y.-Y., & Chen, Z. (2022). Perceiving high social mobility breeds materialism: The mediating role of socioeconomic status uncertainty. Journal of Business Research, 139, 629-638. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Xie, X., Wang, Y., Wang, P., & Lei, L. (2017). Partner phubbing and depression among married Chinese adults: The roles of relationship satisfaction and relationship length. Personality and individual differences, 110, 12-17. [CrossRef]

- Young, L., Kolubinski, D. C., & Frings, D. (2020). Attachment style moderates the relationship between social media use and user mental health and wellbeing. Heliyon, 6(6), e04056. [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1 Attachment anxiety | - | -.164* | .373*** | .362*** | .260*** |

| 2 Attachment avoidance | - | .178** | .088 | .140* | |

| 3 Materialism | - | .420*** | .236*** | ||

| 4 Enacted phubbing | - | .222*** | |||

| 5 Perceived phubbing | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).