Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

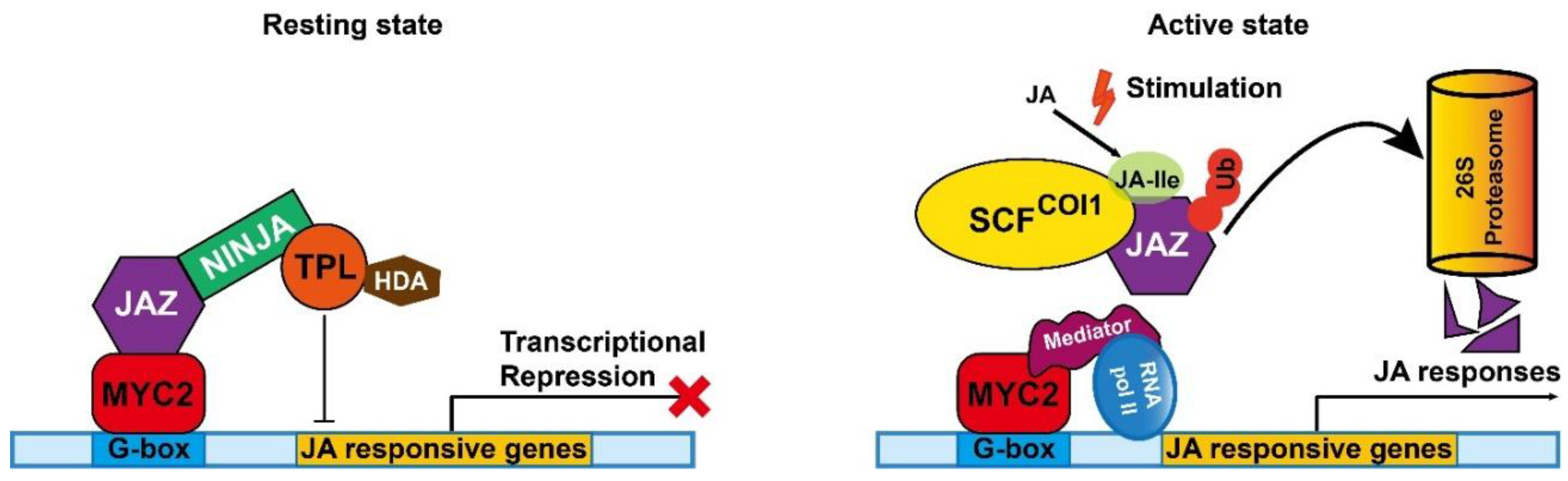

Brassica crops (genus Brassica) represent globally important vegetables and oilseeds yet are continuously threatened by insect pests that reduce yield and quality. While classical physiological and chemical defence mechanisms such as the glucosinolate–myrosinase system have been well documented, recent advances in genomics and molecular biology are beginning to unravel the genetic basis of insect resistance in Brassica species. Notably, emerging evidence highlights the central role of jasmonic acid (JA) signalling and the transcription factor MYC2 as a master regulator of inducible defence responses, where stress-induced degradation of JAZ repressors releases MYC2 to activate downstream defence genes and secondary metabolite biosynthesis. This review synthesizes the current understanding of defence mechanisms in Brassica against herbivores, highlights identified resistance genes and their functional roles, and examines the knowledge gaps that hinder progress in molecular breeding. We then explore future molecular approaches including high-throughput omics, gene editing, and resistance gene mining that hold promise for designing durable insect-resistant Brassica cultivars. Recognising the scarcity of major insect-resistance loci relative to pathogen resistance, we argue for integrated strategies combining classical breeding, biotechnology, and ecological management to accelerate the development of resilient Brassica germplasm.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Insect Pests in Brassica Crops

3. Morphological and Physiological Defence Mechanisms

4. Biochemical Defence Mechanisms: The Glucosinolate–Myrosinase System

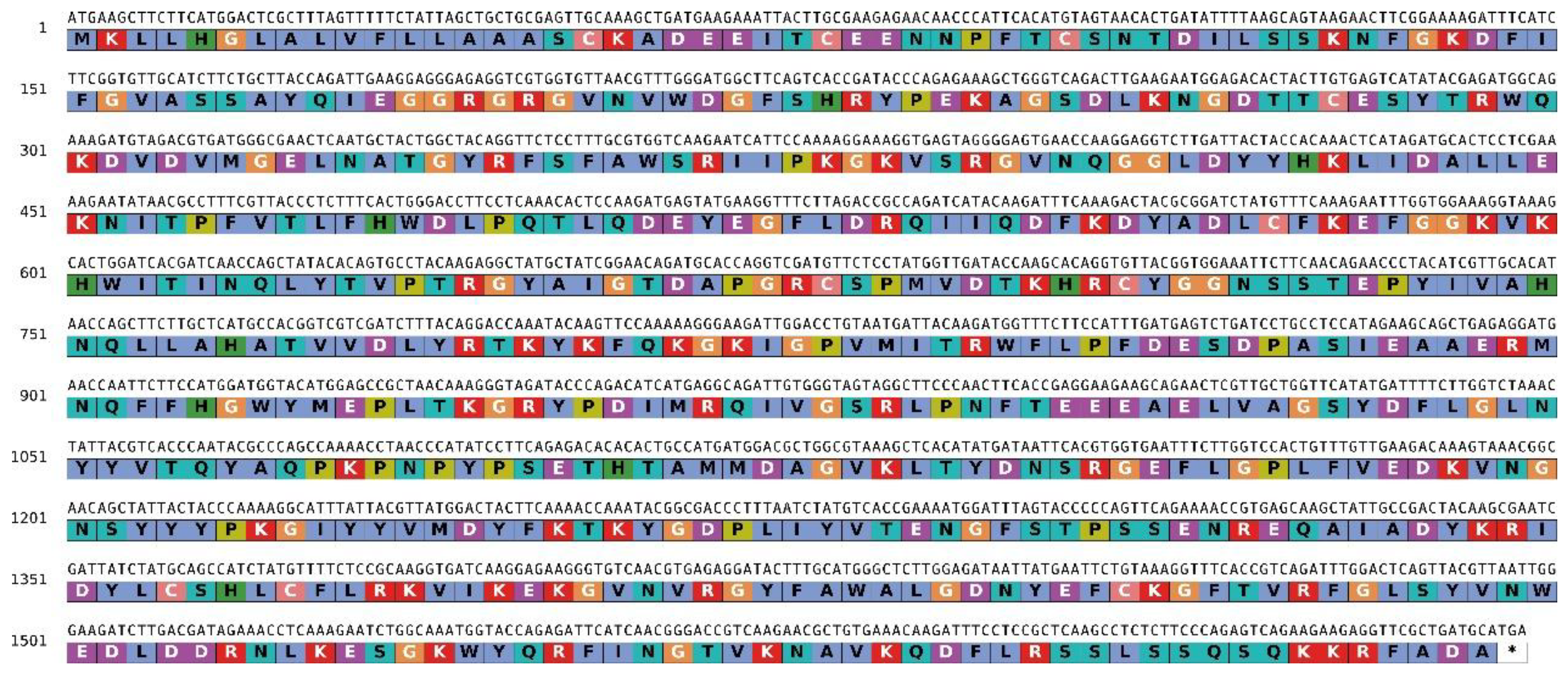

5. Identified Resistance Genes and Molecular Genetic Evidence

6. Omics and Future Molecular Tools for Insect Resistance

7. Knowledge Gaps and Challenges

8. Future Molecular Approaches and Breeding Strategies

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ritonga, F.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Gao, J.; Li, C.; Li, J. Exploiting Brassica rapa L. subsp. pekinensis Genome Research. Plants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Fan, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, X.; Ma, Y. Transcriptome profiling of yellow leafy head development during the heading stage in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa subsp. pekinensis). Physiol. Plant. 2019, 165, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabusam, J.; Liu, M.; Luo, L.; Zulfiqar, S.; Shen, S.; Ma, W.; Zhao, J. Physiological Control and Genetic Basis of Leaf Curvature and Heading in Brassica rapa L. Journal of Advanced Research 2023, 53, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Poveda, J.; Zuluaga, D.L.; Boccaccio, L.; Hassan, Z.; akram, M.; Ali, J. Defence of Brassicaceae plants against generalist and specialised insect pests through the development of myrosinase mutants: A review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 228, 120945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, A.; Hafeez, F.; Aziz, M.A.; Hashim, M.; Naeem, A.; Yousaf, H.K.; Saleem, M.J.; Hussain, S.; Hafeez, M.; Ali, Q.; et al. Assessment of sublethal and transgenerational effects of spirotetramat, on population growth of cabbage aphid, Brevicoryne brassicae L. (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Frontiers in Physiology 2022, 13–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Ban, N.; Hussain, S.; Batool, R.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Liu, T.-X.; Cao, H.-H. Preference and performance of the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae on three Brassicaceae vegetable plants and its association with amino acids and glucosinolates. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0269736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S. Brassica-aphid interaction: Challenges and prospects of genetic engineering for integrated aphid management. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019, 108, 101442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Gil, J.D.B.; Keeley, J.; Jansen, K. The use of pesticides in developing countries and their impact on health and the right to food; European Union, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gaddam, N.R.; Devi, T.M.; Rupali, J.; Reddy, G.R. Exploiting induced plant resistance for sustainable pest management: mechanisms, elicitors, and applications: a review. Journal of Experimental Agriculture International 2024, 46, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Ritonga, F.N.; Yu, H.; Ding, C.; Zhao, X. Effects of Exogenous Antioxidant Melatonin on Physiological and Biochemical Characteristics of Populus cathayana × canadansis ‘Xin Lin 1’ under Salt and Alkaline Stress. Forests 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Tang, H.; Wei, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Su, H.; Niu, L.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X. BrWAX3, Encoding a β-ketoacyl-CoA Synthase, Plays an Essential Role in Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis in Chinese Cabbage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, N.; Liu, F.; Wang, P.; Yan, X.; Gao, H.; Zeng, X.; Wu, G. Overexpression of BraLTP2, a Lipid Transfer Protein of Brassica napus, Results in Increased Trichome Density and Altered Concentration of Secondary Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, S.; Pope, T.W.; Holaschke, M.; Powell, G. The effect of β-aminobutyric acid on the growth of herbivorous insects feeding on Brassicaceae. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2006, 148, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhajed, S.; Misra, B.B.; Tello, N.; Chen, S. Chemodiversity of the Glucosinolate-Myrosinase System at the Single Cell Type Resolution. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemann, J.; Starosta, E.; Kaczmarek, J.; Pawłowicz, I.; Bocianowski, J. Expression Profiling and Interaction Effects of Three R-Genes Conferring Resistance to Blackleg Disease in Brassica napus. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 11613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Zhu, X.; Yuan, S.; Xu, X.; Shi, J.; Zuo, J.; Yue, X.; Su, T.; Wang, Q. Transcriptomic, metabolomic, and physiological analysis of two varieties of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis) that differ in their storability. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 210, 112750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qiu, M.; Ritonga, F.N.; Wang, F.; Zhou, D.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, J. Metabolite Profiling and Comparative Metabolomics Analysis of Jiaozhou Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis) Planted in Different Areas. Frontiers in bioscience (Landmark edition) 2023, 28, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.J.; Hwang, Y.J.; Park, Y.J.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, M.-H. Metabolomics Reveals Lysinibacillus capsici TT41-Induced Metabolic Shifts Enhancing Drought Stress Tolerance in Kimchi Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. subsp. pekinensis). Metabolites 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez i Marti, A.; Dodd, R.S. Using CRISPR as a gene editing tool for validating adaptive gene function in tree landscape genomics. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2018, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Koopmann, B.; Ulber, B.; von Tiedemann, A. A Global Survey on Diseases and Pests in Oilseed Rape—Current Challenges and Innovative Strategies of Control. Frontiers in Agronomy 2020, 2–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, I.; Rohloff, J.; Bones, A.M. Defence mechanisms of Brassicaceae: implications for plant-insect interactions and potential for integrated pest management. In Sustainable Agriculture; Springer, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 623–670. [Google Scholar]

- Satpathy, S.; Gotyal, B.; Babu, V.R. Impact of climate change on insect pest dynamics and its mitigation. In Conservation agriculture and climate change; CRC Press, 2022; pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Suijkerbuijk, H.A.; Poelman, E.H. Insect herbivory differentially affects the behaviour of two pollinators of Brassica rapa. Oecologia 2025, 207, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlov, M.V.; Zverev, V. Losses of Foliage to Defoliating Insects Increase with Leaf Damage Diversity Due to the Complementarity Effect. Insects 2025, 16, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Costamagna, A.C.; Beran, F.; You, M. Biology, ecology, and management of flea beetles in Brassica crops. Annu. Rev. Entomol 2024, 69, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzo, E.; Moreno, A.; Plaza, M.; Fereres, A. Feeding behavior and virus-transmission ability of insect vectors exposed to systemic insecticides. Plants 2020, 9, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, D.M.; Hart, A.J.; Long, S.J.; Richardson, P.N.; Chandler, D. Susceptibility of cabbage root fly Delia radicum, in potted cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis) to isolates of entomopathogenic nematodes (Steinernema and Heterorhabditis spp.) indigenous to the UK. Nematology 2002, 4, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.-P.; Zhan, H.-X.; Wang, Y.-L.; Hou, S.-M. How Cabbage Aphids Brevicoryne brassicae (L.) Make a Choice to Feed on Brassica napus Cultivars. Insects 2019, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palial, S.; Kumar, S.; Atri, C.; Sharma, S.; Banga, S.S. Antixenosis and antibiosis mechanisms of resistance to turnip aphid, Lipaphis erysimi (Kaltenbach) in Brassica juncea-fruticulosa introgression lines. J. Pest Sci. 2022, 95, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, K.D.; Keller, M.A.; Baxter, S.W. Genome-wide analysis of diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella L., from Brassica crops and wild host plants reveals no genetic structure in Australia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, I.M.; Samara, R.; Renaud, J.B.; Sumarah, M.W. Plant growth regulator-mediated anti-herbivore responses of cabbage (Brassica oleracea) against cabbage looper Trichoplusia ni Hübner (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2017, 141, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Kaur, S.; Kumar, J.; Gupta, Y. Development of white butterfly, Pieris brassicae L. in cabbage ecosystem. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2018, 6, 1270–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, R.; Xu, L.; Hao, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, Y. Transcriptome Dynamics of Brassica juncea Leaves in Response to Omnivorous Beet Armyworm (Spodoptera exigua, Hübner). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devetak, M.; Vidrih, M.; Trdan, S. Cabbage moth (Mamestra brassicae [L.]) and bright-line brown-eyes moth (Mamestra oleracea [L.])-presentation of the species, their monitoring and control measures. Acta Agriculturae Slovenica 2010, 95, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, B.; Hartl, T.; Prager, S. Water and nutrient stress modify aster leafhopper probing behavior in canola plants. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 2025, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittapelly, P.; Guelly, K.N.; Hussain, A.; Cárcamo, H.A.; Soroka, J.J.; Vankosky, M.A.; Hegedus, D.D.; Tansey, J.A.; Costamagna, A.C.; Gavloski, J. Flea beetle (Phyllotreta spp.) management in spring-planted canola (Brassica napus L.) on the northern Great Plains of North America. GCB Bioenergy 2024, 16, e13178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Rho, H.Y.; Kim, S. The Effects of Climate Change on Heading Type Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. Pekinensis) Economic Production in South Korea. Agronomy 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gakuru, P.N.; Muhashy Habiyaremye, F.; Noël, G.; Caparros Megido, R.; Francis, F. Assessment of Cabbage (Brassica oleracea Linnaeus) Insect Pests and Management Strategies in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Sun, B.; Gurr, G.M.; Vasseur, L.; Xue, M.; You, M. Gut Microbiota Mediate Insecticide Resistance in the Diamondback Moth, Plutella xylostella (L.). Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebretsadik, K.G.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Qin, A.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, E.; Song, X.; Gao, P.; Xie, Y. Plant-aphid interactions: recent trends in plant resistance to aphids. Stress Biology 2025, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifenrath, K.; Riederer, M.; Müller, C. Leaf surface wax layers of Brassicaceae lack feeding stimulants for Phaedon cochleariae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2005, 115, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, D.; Chakraborty, A.; Biswas, T.; Meher, D.; Singh, A.P. Role of trichomes in plant defence-A crop specific review. Crop Research 2022, 57, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Liu, T. Cuticular proteins: Essential molecular code for insect survival. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2025, 104402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskar, V.; Park, S.W. Molecular characterization of BrMYB28 and BrMYB29 paralogous transcription factors involved in the regulation of aliphatic glucosinolate profiles in Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis. C. R. Biol. 2015, 338, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shi, W.; Zhou, S.; Wang, G. Oral secretions: A key molecular interface of plant–insect herbivore interactions. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 1342–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasantha-Srinivasan, P.; Noh, M.Y.; Park, K.B.; Kim, T.Y.; Jung, W.-J.; Senthil-Nathan, S.; Han, Y.S. Plant immunity to insect herbivores: mechanisms, interactions, and innovations for sustainable pest management. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, I.; Kanedawara, T.; Inoue, K.; Watanabe, S.; Ômura, H. Cabbage Leaf Epicuticular Wax Deters Female Oviposition and Larval Feeding of Pieris rapae. J. Chem. Ecol. 2025, 51, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Tang, J.; Yang, D.; Yang, T.; Liu, H.; Luo, W.; Wu, J.; Jianqiang, W.; Wang, L. Jasmonoyl-l-isoleucine and allene oxide cyclase-derived jasmonates differently regulate gibberellin metabolism in herbivory-induced inhibition of plant growth. Plant Sci. 2020, 300, 110627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, R.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Z.; Gao, T.; Qin, M.; Hu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Li, T. Insights into glucosinolate accumulation and metabolic pathways in Isatis indigotica Fort. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mithen, R.F. Glucosinolates and their degradation products; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mbudu, K.G.; Witzel, K.; Börnke, F.; Hanschen, F.S. Glucosinolate profile and specifier protein activity determine the glucosinolate hydrolysis product formation in kohlrabi (Brassica oleracea var. gongylodes) in a tissue-specific way. Food Chem. 2025, 465, 142032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Q.; Li, X.; Fan, B.; Zhu, C.; Chen, Z. The Cellular and Subcellular Organization of the Glucosinolate–Myrosinase System against Herbivores and Pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.J.; Zhang, P.J.; van Loon, J.J.; Dicke, M. Silencing defense pathways in Arabidopsis by heterologous gene sequences from Brassica oleracea enhances the performance of a specialist and a generalist herbivorous insect. J. Chem. Ecol. 2011, 37, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Escamilla-Treviño, L.; Zeng, L.; Lalgondar, M.; Bevan, D.; Winkel, B.; Mohamed, A.; Cheng, C.-L.; Shih, M.-C.; Poulton, J.; et al. Functional genomic analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana glycoside hydrolase family 1. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004, 55, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Cai, L.; Ding, T.; Tian, E.; Yan, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, K.; Chen, Z. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Molecular Basis of Brassica napus in Response to Aphid Stress. Plants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhlian, L.; Koramutla, M.K.; Subramanian, S.; Chamola, R.; Bhattacharya, R. Comparative transcriptomics revealed differential regulation of defense related genes in Brassica juncea leading to successful and unsuccessful infestation by aphid species. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, S.R.; Jo, J.S.; Lee, J.G. Comparison of Glucosinolate Profiles in Different Tissues of Nine Brassica Crops. Molecules 2015, 20, 15827–15841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.B.; Li, X.; Kim, S.-J.; Kim, H.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Park, S.U. MYB Transcription Factors Regulate Glucosinolate Biosynthesis in Different Organs of Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis). Molecules 2013, 18, 8682–8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmathilake, K.R.E.; Fernando, W.G.D. Leptosphaeria maculans-Brassica napus Battle: A Comparison of Incompatible vs. Compatible Interactions Using Dual RNASeq. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Miao, L.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Xi, D.; Zhang, D.; Gao, L.; Zhu, Y.; Dai, S.; Zhu, H. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis between Resistant and Susceptible Pakchoi Cultivars in Response to Downy Mildew. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ren, X.; Ibrahim, E.; Kong, H.; Wang, M.; Xia, J.; Wang, H.; Shou, L.; Zhou, T.; Li, B.; et al. Response of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa subsp. pekinensis) to bacterial soft rot infection by change of soil microbial community in root zone. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfalz, M.; Vogel, H.; Mitchell-Olds, T.; Kroymann, J. Mapping of QTL for resistance against the crucifer specialist herbivore Pieris brassicae in a new Arabidopsis inbred line population, Da (1)-12× Ei-2. PLOS ONE 2007, 2, e578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, J. Evaluation of Flea Beetle (Phyllotreta spp.) Resistance in Spring and Winter-type Canola (Brassica napus); University of Guelph, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Obermeier, C.; Mason, A.S.; Meiners, T.; Petschenka, G.; Rostás, M.; Will, T.; Wittkop, B.; Austel, N. Perspectives for integrated insect pest protection in oilseed rape breeding. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 3917–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neequaye, M.; Steuernagel, B.; Saha, S.; Trick, M.; Troncoso-Rey, P.; van den Bosch, F.; Traka, M.H.; Østergaard, L.; Mithen, R. Characterisation of the Introgression of Brassica villosa Genome Into Broccoli to Enhance Methionine-Derived Glucosinolates and Associated Health Benefits. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 855707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, T.J.; Matthes, M.C.; Chamberlain, K.; Woodcock, C.M.; Mohib, A.; Webster, B.; Smart, L.E.; Birkett, M.A.; Pickett, J.A.; Napier, J.A. cis-Jasmone induces Arabidopsis genes that affect the chemical ecology of multitrophic interactions with aphids and their parasitoids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2008, 105, 4553–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G. Novel approaches for evaluating brassica germplasm for insect resistance; University of Birmingham, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Timko, M.P. Jasmonic Acid Signaling and Molecular Crosstalk with Other Phytohormones. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C.; Song, S. Jasmonates: biosynthesis, metabolism, and signaling by proteins activating and repressing transcription. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1303–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweizer, F.; Fernández-Calvo, P.; Zander, M.; Diez-Diaz, M.; Fonseca, S.; Glauser, G.; Lewsey, M.G.; Ecker, J.R.; Solano, R.; Reymond, P. Arabidopsis basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors MYC2, MYC3, and MYC4 regulate glucosinolate biosynthesis, insect performance, and feeding behavior. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 3117–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Dong, Y.; Saqib, H.S.A.; Vasseur, L.; Zhou, W.; Zheng, L.; Lai, Y.; Ma, X.; Lin, L.; Xu, X.; et al. Functions of duplicated glucosinolate sulfatases in the development and host adaptation of Plutella xylostella. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 119, 103316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.; Jiang, X.; Reichelt, M.; Gershenzon, J.; Pandit, S.S.; Giddings Vassão, D. Tritrophic metabolism of plant chemical defenses and its effects on herbivore and predator performance. eLife 2019, 8, e51029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eakteiman, G.; Moses-Koch, R.; Moshitzky, P.; Mestre-Rincon, N.; Vassão, D.G.; Luck, K.; Sertchook, R.; Malka, O.; Morin, S. Targeting detoxification genes by phloem-mediated RNAi: a new approach for controlling phloem-feeding insect pests. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 100, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israni, B.; Wouters, F.C.; Luck, K.; Seibel, E.; Ahn, S.-J.; Paetz, C.; Reinert, M.; Vogel, H.; Erb, M.; Heckel, D.G.; et al. The Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda Utilizes Specific UDP-Glycosyltransferases to Inactivate Maize Defensive Benzoxazinoids. Frontiers in Physiology 2020, 11–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.C.; Sharma, K.K.; Seetharama, N.; Ortiz, R. Prospects for using transgenic resistance to insects in crop improvement. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2000, 3, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang Hong-jun, L.D.-l.W.G.-l.L.Y.-h.Z.Z.; Li, X.-h. An Insect-Resistant Transgenic Cabbage Plant with Cowpea Trypsin Inhibitor(CpTI) Gene. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 39.

- Ram, C.; Koramutla, M.K.; Bhattacharya, R. Identification and comprehensive evaluation of reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis of host gene-expression in Brassica juncea-aphid interaction using microarray data. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 116, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagers, C.L.; Londo, J.P.; Bautista, N.; Lee, E.H.; Watrud, L.S.; King, G. Benefits of Transgenic Insect Resistance in Brassica Hybrids under Selection. Agronomy 2015, 5, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahakoon, U.I.; Taheri, A.; Nayidu, N.K.; Epp, D.; Yu, M.; Parkin, I.; Hegedus, D.; Bonham-Smith, P.; Gruber, M.Y. Hairy canola (Brasssica napus) re-visited: down-regulating TTG1 in an AtGL3-enhanced hairy leaf background improves growth, leaf trichome coverage, and metabolite gene expression diversity. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahakoon, U.; Adamson, J.; Grenkow, L.; Soroka, J.; Bonham-Smith, P.; Gruber, M. Field growth traits and insect-host plant interactions of two transgenic canola (Brassicaceae) lines with elevated trichome numbers. The Canadian Entomologist 2016, 148, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, N.; Caarls, L.; Bukovinszkine’Kiss, G.; El-Soda, M.; van Veen, J.; Bouwmeester, K.; Zwaan, B.J.; Schranz, M.E.; Bonnema, G.; Fatouros, N.E. Genetic analysis reveals three novel QTLs underpinning a butterfly egg-induced hypersensitive response-like cell death in Brassica rapa. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, I.; Rohloff, J.; Bones, A.M. Defence mechanisms of Brassicaceae: implications for plant-insect interactions and potential for integrated pest management. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2010, 30, 311–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Du, J.; Sun, Y.; Liang, A. Novel insect resistance in Brassica napus developed by transformation of chitinase and scorpion toxin genes. Plant Cell Rep. 2005, 24, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, J.; Cai, X.; Li, Y.; Xi, X.; Lin, R.; Liang, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, J. Improved Reference Genome Annotation of Brassica rapa by Pacific Biosciences RNA Sequencing. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Adhikary, D.; Kav, N.N.V.; Scandola, S.; Uhrig, R.G.; Rahman, H. Proteomics Integrated with Transcriptomics of Clubroot Resistant and Susceptible Brassica napus in Response to Plasmodiophora brassicae Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, L.; Huang, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Sun, R.; Zhao, J.; Li, G. Integrated Volatile Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Analyses Reveal the Influence of Infection TuMV to Volatile Organic Compounds in Brassica rapa. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.R.; Siddique, M.I.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, E.S.; Han, K.; Kim, S.G.; Lee, H.E. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing to confer turnip mosaic virus (TuMV) resistance in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa). Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Demirer, G.S. Synthetic biology for plant genetic engineering and molecular farming. Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 1182–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawson, R.; Heaney, R.K.; Zdunczyk, Z.; Kozłowska, H. Rapeseed meal-glucosinolates and their antinutritional effects. Part 6. Taint in end-products. Die Nahrung 1995, 39, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilson, D. The evolution of plant response to herbivory: simultaneously considering resistance and tolerance in Brassica rapa. Evol. Ecol. 2000, 14, 457–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Park, Y.D. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Mutagenesis of BrLEAFY Delays the Bolting Time in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Insect | Scientific name | Type of oral appendage | Distribution | Host Plant | References |

| Cabbage aphid | Brevicoryne brassicae L. | Sucking | China, South Asia | Cabbage, oilseed rape | [5,28] |

| Green peach aphid | Myzus persicae Sulzer. | Sucking | China and Europe | Chinese cabbage, cabbage, radish | [6] |

| Turnip aphid | Lipaphis erysimi Kaltenbach. | Sucking | South Asia | Indian mustard | [29] |

| Diamondback moth | Plutella xylostella L. | Chewing | Australia, Asia, Africa | Broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, kale, mustard, turnip | [30] |

| Cabbage looper | Trichoplusia ni Hübner. | Chewing | North American native found throughout the US, Canada, and Mexico | Broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, kale, collards, mustard, rutabaga, turnip | [31] |

| Cabbage butterfly | Pieris brassicae L. | Chewing | North Africa across Europe and Asia to the Himalayas | Kale, cabbage, turnip, black mustard, Ethiopian mustard, swede | [32] |

| Beet armyworm | Spodoptera exigua Hübner. | Chewing | Southeast Asia, Eastern Asia | mustard | [33] |

| Cabbage moth | Mamestra brassicae L. | Chewing | Europe, North Africa (Libya, Canary Islands), Japan and sub- tropical Asia, including India | Cabbage, red cabbage, mustard, turnip, | [34] |

| Leafhoppers | Cicadelliade sp. | Sucking | Asia, Europe | canola | [35] |

| Flea beetles | Phyllotreta cruciferae | Chewing | Europe, North America | canola | [36] |

| Insect | Scientific name | Gene name | Application | Function | Model plant | References |

| diamondback moth | P. xylostella |

GSS1 GSS2 |

CRISPR/Cas9 | Increase insect resistance | Arabidopsis thaliana | [71] |

| diamondback moth | P. xylostella | GSS1 | RNAi | Increase insect resistance | Arabidopsis thaliana | [72] |

| Silverleaf whitefly | Bemisia tabaci | BtGSTs5 | RNAi | detoxification mechanisms | Gossypium hirsutum | [73] |

| fall armyworm | podoptera frugiperda | UGT33 and UGT40 | RNAi | detoxification enzymes secondary metabolytes |

maize | [74] |

| cabbage looper and cabbage butterfly | Trichoplusia ni and Pieris rapae | Cry1C | NA | Increase insect resistance | broccoli (Brassica oleracea ssp. italica) | [75] |

| C. suppressalis | C. suppressalis and Sesamia inferens ( | CpTI | traditional transgenic transformation (Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer) | Increase insect resistance |

Brassica oleracea var. capitata cultivars Yingchun and Jingfeng |

[76] |

| mustard aphids | Lipaphis erysimi | CAC, TUA and DUF179 | microarray | Increase aphid resistance | B. juncea | [77] |

| diamondback moth | P. xylostella | Bt Cry1Ac | transgenic (genetically modified) approach | Increase insect resistance | Brassica napus L. (canola) and Brassica rapa | [78] |

| flea beetles | Phyllotreta cruciferae and P. striolata | AtGL3 | classical transgenic insertion (T-DNA) and modified expression via transgenic constructs | Increase leaf trichome coverage | Brassica napus | [79,80] |

| flea beetles | Phyllotreta cruciferae and P. striolata | BnTTG1 | classical transgenic insertion (T-DNA) and modified expression via transgenic constructs | Increase leaf trichome coverage | Brassica napus | [79,80] |

| cabbage butterfly | P. brassicae | LecRK-I.1 | classical genetic mapping / QTL mapping | Increase insect resistance | B. rapa | [81] |

| diamondback moth | P. xylostella | Bt cry1C | NA | Increase insect resistance | collard and Indian mustard | [82] |

| diamondback moth | P. xylostella | Chitinase (chi) |

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation |

Increase insect resistance | Brassica napus | [83] |

| diamondback moth | P. xylostella | BmkIT(Bmk) |

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation |

Increase insect resistance | Brassica napus | [83] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).