Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

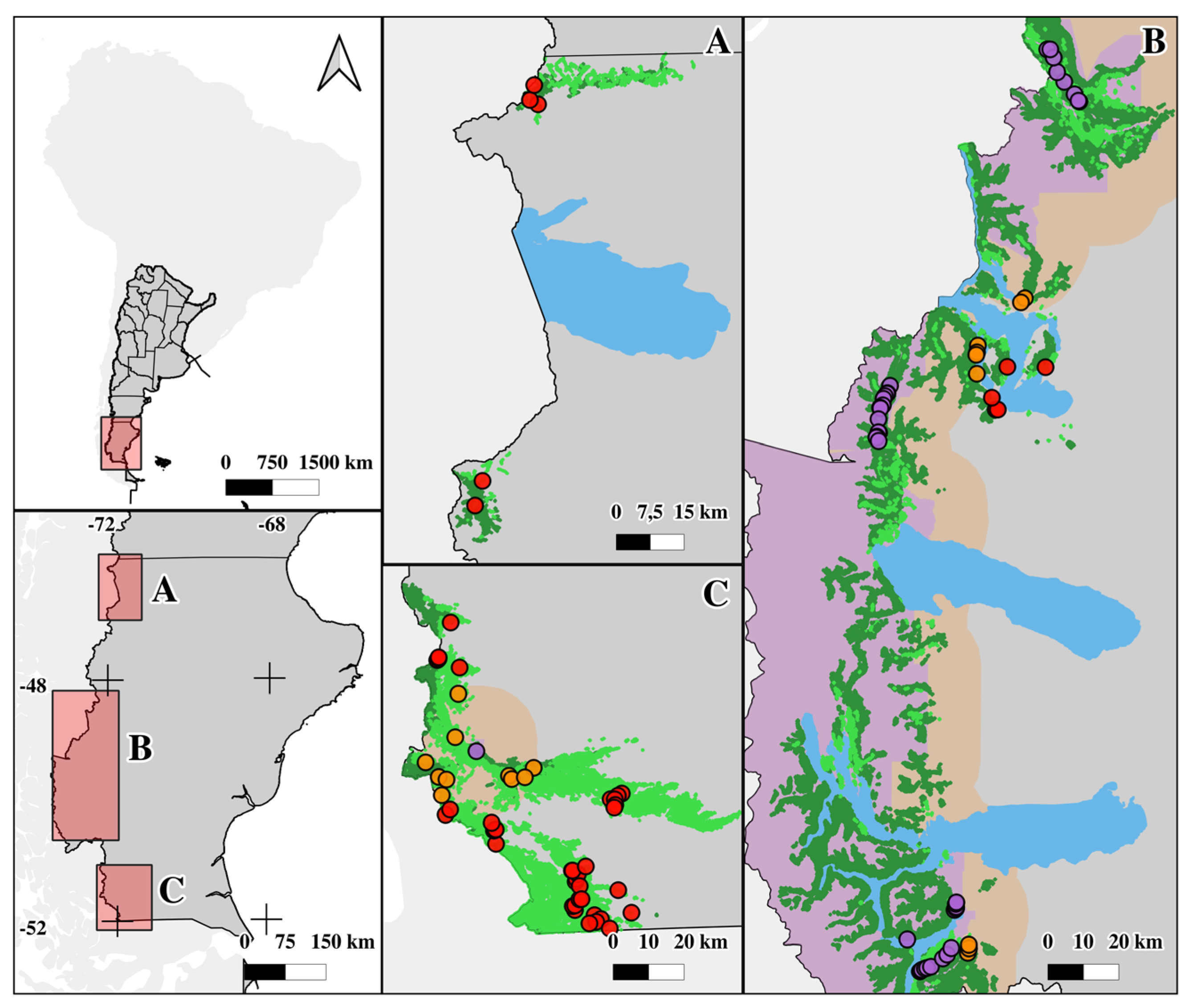

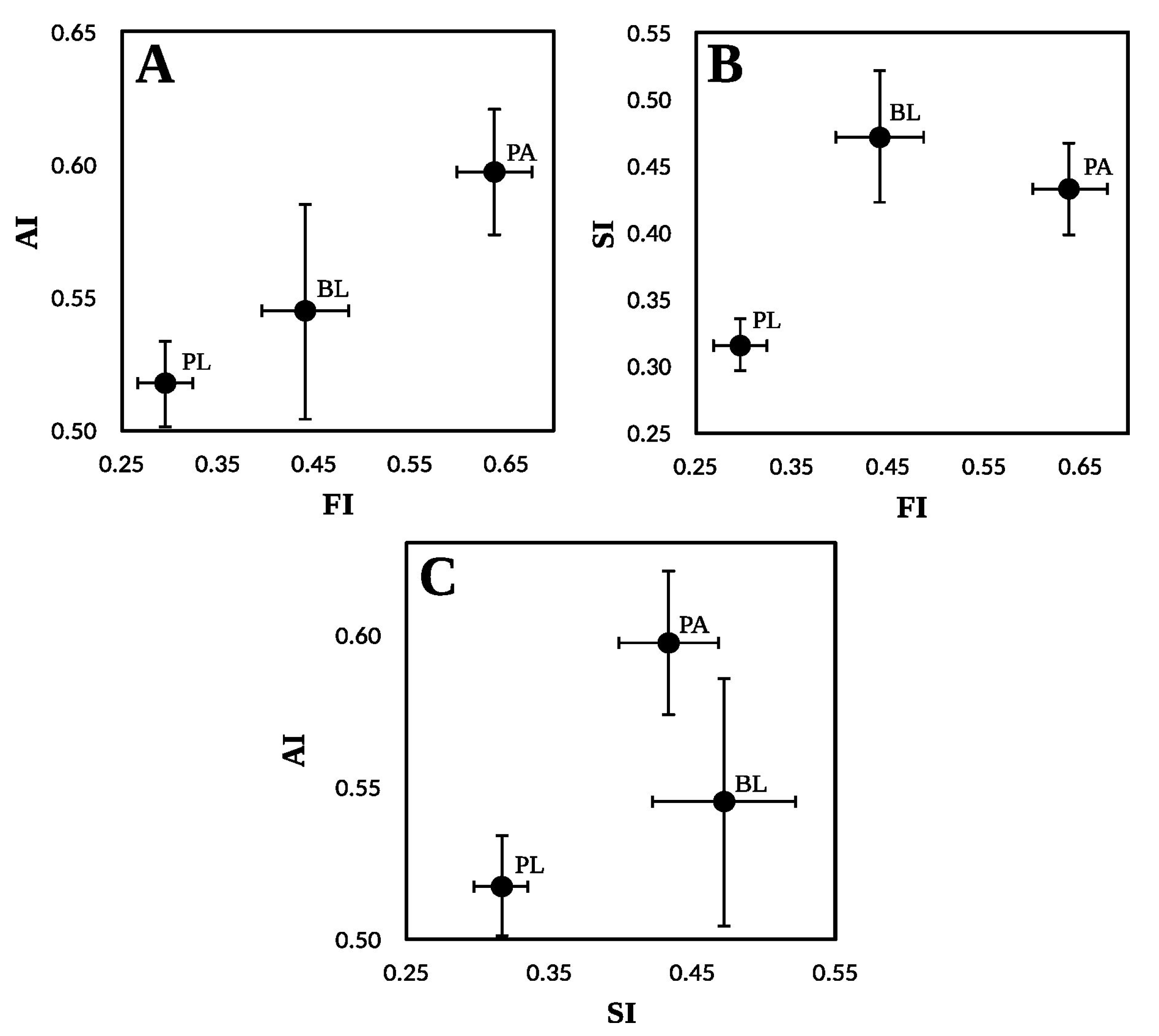

Protected areas (PA) constitute a fundamental strategy for mitigating biodiversity loss. Land-sparing approach has expanded in response to international agreements, but expansion of PA does not guarantee conservation objectives. The objective was to assess PA effectiveness in conserving Nothofagus antarctica forests in Santa Cruz (Argentina) evaluating human impacts (fire, animal use, harvesting). The research was conducted within pure native forests in Santa Cruz, Argentina. This province encompasses 52 protected areas, representing the highest concentration of conservation units within the forested landscapes of the country. At least eight of these areas include N. antarctica forests. Three land tenure categories were evaluated: protected areas (PA), buffer of 15-km from PA boundaries on private lands (BL), and private lands (PL). 103 sampling plots were established, where 38 variables were assessed (impacts, soil, forest structure, understory, animal use). Three indices were developed to analyze ecosystem integrity: forest structure (FI), soil (SI), and animal use (AI). PA presents highest FI (0.64 for PA, 0.44 for BL, 0.30 for PL) and AI (0.60 for PA, 0.55 for BL, 0.52 for PL), and together with buffer zones, the highest SI (0.43 for PA, 0.47 for BL, 0.32 for PL. PA showed superior integrity regarding compared to BL and PL, indicating effective preservation despite anthropogenic impacts.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Taking and Data Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA | Protected areas |

| BL | Buffer lands |

| PL | Private lands |

| FI | Forest structure index |

| SI | Soil index |

| AI | Animal use index |

| NP | National parks |

References

- Arora, N.K.; Mishra, I. Life on land: progress, outcomes and future directions to achieve the targets of SDG 15. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 7, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, V.M.; Chauvenet, A.L.; Stoudmann, N.; Gurney, G. G.; Brockington, D.; Kuempel, C.D. Multiple-use protected areas are critical to equitable and effective conservation. One Earth 2023, 6, 1173–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.N.; Lemieux, C.J.; Grantham, H.S.; Rao, M.; Clyne, P.J.; Rathbone, V.; Sharma, R. What will count? Evidence for the global recognition of other effective area-based conservation measures. Conserv. Lett. 2025, 18, e13150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Vilca, O.J.; Diaz, L.J.; García, J.D.; Cruz, J.A. Contaminación y pérdida de biodiversidad por actividades mineras y agropecuarias: estado del arte. Rev. Inv. Altoandin. 2024, 26, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A.; Ranacher, L.; Hesser, F.; Stern, T.; Schuster, K.C. Bridging business and biodiversity: An analysis of biodiversity assessment tools. Environ. Sustain. Ind. 2025, 26, e100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, H.D.; Bingham, H.C.; Bennett, N.J.; Woodley, S.; Zlatanova, R.; Howland, E.; Belle, E.; Upton, J.; Gottlieb, B.; Kamath, V.; et al. Global status and emerging contribution of other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) towards the ‘30x30’ biodiversity Target 3. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2024, 5, e1447434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneth, A.; Leadley, P.; Claudet, J.; Coll, M.; Rondinini, C.; Rounsevell, M.D.; Shin, Y.J.; Alexander, P.; Fuchs, R. Making protected areas effective for biodiversity, climate and food. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 3883–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, K.M. Adaptabilidad y optimización de una herramienta de evaluación de efectividad de manejo de áreas protegidas (Ecuador). Rev. Latinoam. Cien. Soc. Hum. 2024, 5, 4565–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; West, P.; Thakholi, L.; Suryawanshi, K.; Supuma, M.; Straub, D.; Sithole, S.S.; Sharma, R.; Schleicher, J.; Ruli, B.; et al. Governance and conservation effectiveness in protected areas and indigenous and locally managed areas. Ann. Rev. Environ. Res. 2023, 48, 559–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.J.; Noble, B.P.; Veneros, J.; East, A.; Goetz, S.J.; Supples, C.; Watson, J.E.M.; Jantz, P.A.; Pillay, R.; Jetz, W.; et al. Toward monitoring forest ecosystem integrity within the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, e12822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazco, S.J.E.; Bedrij, N.A.; Rojas, J.L.; Keller, H.A.; Ribeiro, B.R.; De Marco, P. Quantifying the role of protected areas for safeguarding the uses of biodiversity. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 268, e109525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, E.; Mori, G.M.; Barboza, E.; Briceño, N.B.R.; Guzmán, C.T.; Oliva-Cruz, M.; Chavez-Quintana, S.G.; Salas López, R.; López de la Lama, R.; Sevillano-Ríos, S.; et al. Efectividad de áreas de conservación privada comunal en bosques montanos nublados del norte de Perú. Pirineos 2021, 176, e067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaSala, D.A.; Mackey, B.; Kormos, C.F.; Young, V.; Boan, J.J.; Skene, J.L.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Kun, Z.; Selva, N.; Malcolm, J.R.; et al. Measuring forest degradation via ecological-integrity indicators at multiple spatial scales. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 302, 110939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essbiti, M.C.; Namous, M.; Krimissa, S.; Elaloui, A.; Hajaj, S.; Mosaid, H.; Ismaili, M.; Hajji, S.; El Atiq, J.; El Kamouni, F.E. Emerging trends and future directions in remote-sensing techniques and platforms for sustainable forest degradation monitoring: a review. Mediter. Geosci. Rev. 2025, 7, 953–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzwarth, S.; Thonfeld, F.; Kacic, P.; Abdullahi, S.; Asam, S.; Coleman, K.; Eisfelder, C.; Gessner, U.; Huth, J.; Kraus, T.; et al. Earth-observation-based monitoring of forests in Germany. Recent progress and research Frontiers: A review. Remote Sen. 2023, 15, e4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsellino, M.L.; Zufiaurre, E.; Bilenca, D.N. La investigación científica y la conservación de la biodiversidad en parques nacionales de la Argentina. Dónde estamos y hacia dónde podríamos ir. Ecol. Austr. 2022, 32, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, V.M. Análisis de situación y perspectivas de la gestión del Sistema de áreas protegidas de la provincia de Santa Cruz. Inf. Cient. Téc. UNPA 2025, 17, 19–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, Y.M.; Peri, P.L.; Martínez Pastur, G. Assessment of provisioning ecosystem services in terrestrial ecosystems of Santa Cruz Province, Argentina. In Ecosystem Services in Patagonia: A Multi-Criteria Approach for an Integrated Assessment; Peri, P.L., Martínez Pastur, G., Nahuelhual, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, P.L.; Ormaechea, S.G. Relevamiento de los bosques nativos de ñire (Nothofagus antarctica) en Santa Cruz: Base para su conservación y manejo; Ed. INTA: Río Gallegos, Argentina, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, G.; Correa, M.; Figueroa, S.; San Martín, J. Variation in the growth habit and habitat of Nothofagus antarctica in South-Central Chile. Bosque 1985, 6, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliani, C.; Marchelli, P.; Mondino, V.; Pastorino, M.; Mattera, M.G.; Gallo, L.; Aparicio, A.; Torres, A.D.; Tejera, L.; Schinelli, C.T. Nothofagus pumilio and N. antarctica: The most widely distributed and cold-tolerant southern beeches in Patagonia. In Low intensity breeding of native forest trees in Argentina; Pastorino, M., Marchelli, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Rosas, Y.M.; Chaves, J.E.; Cellini, J.M.; Barrera, M.D.; Favoretti, S.; Lencinas, M.V.; Peri, P.L. Changes in forest structure values along the natural cycle and different management strategies in Nothofagus antarctica forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 2021, 486, e118973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, P.L.; López, D.; Rusch, V.; Rusch, G.; Rosas, Y.M.; Martínez Pastur, G. State and transition model approach in native forests of Southern Patagonia (Argentina): Linking ecosystemic services, thresholds and resilience. Int. J. Biodiv. Sci. Ecosyst. Ser. Manage. 2017, 13, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, R.; Lencinas, M.V.; Martínez Pastur, G.; Rosas, Y.M.; Bustamante, G.; Espelta, J.M. Forest regrowth in Tierra del Fuego, Southern Patagonia: Landscape drivers and effects on forest structure, soil, and understory attributes. Reg. Environ. Change 2022, 22, e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Rodríguez-Souilla, J.; Rosas, Y.M.; Politi, N.; Rivera, L.; Silveira, E.M.O.; Olah, A.M.; Pidgeon, A.M.; Lencinas, M.V.; Peri, P.L. Conservation value and ecosystem service provision of Nothofagus antarctica forests based on phenocluster categories. Discov. Conserv. 2025, 2, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattera, M.G.; Gonzalez-Polo, M.; Peri, P.L.; Moreno, D.A. Intraspecific variation in leaf (poly) phenolic content of a southern hemisphere beech (Nothofagus antarctica) growing under different environmental conditions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, e20050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huertas Herrera, A.; Toro-Manríquez, M.D.; Sanhueza, J.S.; Guínez, F.R.; Lencinas, M.V.; Martínez Pastur, G. Relationships among livestock, structure, and regeneration in Chilean Austral Macrozone temperate forests. Trees For. People. 2023, 13, e100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichancourt, J.B. Navigating the complexities of the forest land sharing vs sparing logging dilemma: analytical insights through the governance theory of social-ecological systems dynamics. PeerJ 2024, 12, e16809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Herrera, L.A.; Sepulveda, C.; Jiménez, J.A.; Betanzos Simon, J.E.; Pérez-Sánchez, E.; Niño, L. Landscape connectivity in extensive livestock farming: an adaptive approach to the land sharing and land sparing dilemma. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1345517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioiosa, M.; Spada, A.; Cammerino, A.R.B.; Ingaramo, M.; Monteleone, M. Can agriculture conserve biodiversity? Structural biodiversity analysis in a case study of wild bird communities in Southern Europe. Environments 2025, 12, e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustiny, E.; Frehner, A.; Green, A.; Mathys, A.; Rosa, F.; Pfister, S.; Muller, A. Empirical evidence supports neither land sparing nor land sharing as the main strategy to manage agriculture-biodiversity tradeoffs. PNAS Nexus 2025, 4, pgraf251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Rogel, P.; Aravena, J.C.; Villalba, R.; Bringas, C.; Meier, W.; Gonzalez-Reyes, A.; Grießinger, J. Two Nothofagus species in Southernmost South America are recording divergent climate signals. Forests 2022, 13, e794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafaqat, W.; Sanchez, P.; Botnen, D.; Fernandez-Anez, N. Analysing historical events and current management strategies of wildfires in Norway. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, e24905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggirello, M.J.; Bustamante, G.; Soler, R. Nothofagus pumilio regeneration failure following wildfire in the sub-Antarctic forests of Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. Forestry 2025, 98, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onditi, K.O.; Li, X.; Song, W.; Li, Q.; Musila, S.; Mathenge, J.; Kioko, E.; Jiang, X. The management effectiveness of protected areas in Kenya. Biodiv. Conserv. 2021, 30, 3813–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitterlich, W. The relascope idea. Relative measurements in forestry; Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux: Farnham Royal, UK, 1984; p. 242. [Google Scholar]

- Ivancich, H.S.; Martínez Pastur, G.; Lencinas, M.V.; Cellini, J.M.; Peri, P.L. Proposals for Nothofagus antarctica diameter growth estimation: Simple vs. global models. J. For. Sci. 2014, 60, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivancich, H.S. Relaciones entre la estructura forestal y el crecimiento del bosque de Nothofagus antarctica en gradientes de edad y calidad de sitio. PhD. Thesis, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Frazer, G.W.; Fournier, R.A.; Trofymow, J.A.; Hall, R.J. A comparison of digital and film fisheye photography for analysis of forest canopy structure and gap light transmission. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2001, 109, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil agricultural chemical analysis; China Agric. Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, M.; Gregorich, E. Soil sampling and methods of analysis; Taylor and Francis: Boca Ratón, USA, 2007; p. 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Cellini, J.M.; Chaves, J.E.; Rodríguez-Souilla, J.; Benitez, J.; Rosas, Y.M.; Soler, R.; Lencinas, M.V.; Peri, P.L. Changes in forest structure modify understory and livestock occurrence along the natural cycle and different management strategies in Nothofagus antarctica forests. Agrofor. Syst. 2022, 96, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Liu, Y. Landscape ecological integrity assessment to improve protected area management of forest ecosystem. Ecologies 2025, 6, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatPoint Technologies. Statgraphics Centurion XVI (Version 16.1.11); Warrenton, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Faúndez Pinilla, J.; Castillo Soto, M.; Navarro Cerrillo, R.M. Impactos de los incendios forestales de magnitud en áreas silvestres protegidas de Chile Central. Bosque 2023, 44, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughton, E.H.; Sonnier, G.; Gomez-Casanovas, N.; Bernacchi, C.; DeLucia, E.; Sparks, J.; Swain, H.; Anderson, E.; Brinsko, K.; Gough, A.M. Impact of patch-burn grazing on vegetation composition and structure in subtropical humid grasslands. Range. Ecol. Manage. 2025, 98, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, N. Assessing wildfire impact on vegetation in protected areas using the dNBR index: Insights from the designated location in Serbia. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijic. 2025, 75, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardalau, D.; Codrean, C.; Iordache, D.; Fedorca, M.; Ionescu, O. The expanding thread of ungulate browsing: A review of forest ecosystem effects and management approaches in Europe. Forests 2024, 15, e1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Poudyal, N.C.; Silwal, T.; Joshi, O.; Bhandari, A.R.; Pant, G.; Hodges, D.G. Effectiveness of protected area revenue-sharing program: Lessons from the key informants of Nepal's buffer zone program. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 367, e121980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Versendaal, L.; Schickhoff, U. The evolution of threats to protected areas during crises: insights from the COVID-19 pandemic in Madagascar. Hum. Ecol. 2024, 52, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D.; Bortolamiol, S.; Gogarten, J.F.; Hartter, J.; Hou, R.; Kagoro, W.; Omeja, P.; Tumwesigye, C.; Chapman, C.A. Exploring multiple dimensions of conservation success: Long-term wildlife trends, anti-poaching efforts and revenue sharing in Kibale National Park, Uganda. Anim. Conserv. 2022, 25, 532–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, B.M.; Montoya, E.; Sakschewski, B.; Nascimento, N.; Staal, A.; Betts, R.A.; Levis, C.; Lapola, D.M.; Esquível-Muelbert, A.; Jakovac, C.; et al. Critical transitions in the Amazon forest system. Nature 2024, 626, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yu, J.; Wu, W.; Hou, R.; Yang, Z.; Owens, J.R.; Gu, X.; Xiang, Z.; Qi, D. Evaluating the efficacy of zoning designations for national park management. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 27, e01562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ziegler, A.D.; Wu, J.; Liang, S.; Wang, D.; Xu, R.; Duangnamon, D.; Li, H.; Zeng, Z. Effectiveness of protected areas in preventing forest loss in a tropical mountain region. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, e108697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schooler, S.L.; Finnegan, S.P.; Fowler, N.L.; Kellner, K.F.; Lutto, A.L.; Parchizadeh, J.; van den Bosch, M.; Zubiria Perez, A.; Masinde, L.M.; Mwampeta, S.B.; et al. Factors influencing lion movements and habitat use in the western Serengeti ecosystem, Tanzania. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, e18890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Ye, S.; Gao, P.; Ren, S.; Liu, C.; Song, C. Analyzing spatial patterns and driving factors of cropland change in China's National Protected Areas for sustainable management. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, e169102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Granados, C.; Schuchmann, K.L. The sound of the illegal: Applying bioacoustics for long-term monitoring of illegal cattle in protected areas. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 74, 101981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veblen, T.T.; Mermoz, M.; Martin, C.; Kitzberger, T. Ecological impacts of introduced animals in Nahuel Huapi National Park, Argentina. Conserv. Biol. 1992, 6, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, P.G.; Núñez, C.I. Livestock activity in Norwestern Patagonian protected areas. Environ. Anal. Ecol. Stu. 2023, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grass, I.; Batáry, P.; Tscharntke, T. Combining land-sparing and land-sharing in European landscapes. In Advances in ecological research; Bohan, D.A., Vanbergen, A.J., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2021; pp. 251–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, F.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z. Integrating forest restoration into land-use planning at large spatial scales. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, R452–R472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, P.L.; Rosas, Y.M.; Lopez, D.; Lencinas, M.V.; Cavallero, L.; Martínez Pastur, G. Marco conceptual para definir estrategias de manejo en sistemas silvopastoriles para los bosques nativos. Ecol. Austral 2022, 32, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggirello, M.J.; Bustamante, G.; Fulé, P.Z.; Soler, R. Drivers of post-fire Nothofagus antarctica forest recovery in Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, e1113970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veblen, T.T.; Donoso, C.; Kitzberger, T.; Rebertus, A.J. The ecology of southern Chilean and Argentinean Nothofagus forests. In Ecology of southern Chilean and Argentinean Nothofagus forests; Veblen, T.T., Hill, R.S., Read, J., Eds.; Yale University Press: New Haven, Connecticut, USA, 1996; pp. 293–353. [Google Scholar]

- Ceccherini, G.; Girardello, M.; Beck, P.S.A.; Migliavacca, M.; Duveiller, G.; Dubois, G.; Avitabile, V.; Battistella, L.; Barredo, J.I.; Cescatti, A. Spaceborne LiDAR reveals the effectiveness of European protected areas in conserving forest height and vertical structure. Comm. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Progress in research on the effects of environmental factors on natural forest regeneration. Front. For. Glob. Change 2025, 8, e1525461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wei, S.; Hao, D.; Jia, L.; Liang, W. Optimizing adaptive disturbance in planted forests: Resource allocation strategies for sustainable regeneration from seedlings to saplings. Plant Cell. Environ. 2025, 48, 8114–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.M.; Cannon, J.B.; Ex, S.; Ocheltree, T.W.; Redmond, M.D. Canopy-mediated microclimate refugia do not match narrow regeneration niches in a managed dry conifer forest. For. Ecol. Manage. 2024, 553, e121566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwagrzyk, J.; Gazda, A.; Cacciatori, C.; Tomski, A.; Maciejewski, Z.; Zwijacz-Kozica, T.; Zięba, A.; Foremnik, K.; Madalcho, A.B.; Bodziarczyk, J. Species-specific branching architecture influences sapling resilience to ungulate browsing pressure in temperate forests. Forestry 2025, cpaf033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamorano-Elgueta, C.; Becerra-Rodas, C. Successional dynamics are influenced by cattle and selective logging in Nothofagus deciduous forests of Western Patagonia. Forests 2025, 16, e580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, M.M.; Peri, P.L.; Lencinas, M.V.; Soler Esteban, R.M.; Rovere, A.E.; González Peñalba, M.; Chauchard, L.; Urretavizcaya, M.F.; Loguercio, G.; Mundo, I.A.; Cellini, J.M.; et al. Región Patagónica (Bosques Andino Patagónicos). In Uso sostenible del bosque: Aportes desde la Silvicultura Argentina; Peri, P.L., Martínez Pastur, G., Schlichter, T., Eds.; MAyDS: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2021; pp. 692–809. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Aravena Acuña, M.C.; Silveira, E.M.O.; Von Müller, A.; La Manna, L.; González-Polo, M.; Chaves, J.E.; Cellini, J.M.; Lencinas, M.V.; Radeloff, V.C.; et al. Mapping soil organic carbon content in Patagonian forests based on climate, topography and vegetation metrics from satellite imagery. Rem. Sen. 2022, 14, e5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelemeijer, I.A.; Severholt, I.; Ehrlén, J.; De Frenne, P.; Jönsson, M.; Hylander, K. Canopy cover and soil moisture influence forest understory plant responses to experimental summer drought. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; Zheng, H.; Wei, W.; Wang, P.; Bi, H.; Zhang, J.; Wei, T.; Wang, R.; Wang, L. Natural forests accelerate soil hydrological processes and enhance water-holding capacities compared to planted forests after long-term restoration. Water Res. 2025, 61, e2025WR040857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llano, M.P. Spatiotemporal variability of monthly precipitation concentration in Argentina. JSHESS 2023, 73, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, E.; Groenewoud, R.; de Vries, J.; van der Zee, J.; Nabuurs, G.J.; Vos, M.; Sterck, F. Canopy cover at the crown-scale best predicts spatial heterogeneity of soil moisture within a temperate Atlantic forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 363, e110431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobre, A.C.; Pascu, I.S.; Leca, Ș.; Garcia-Duro, J.; Dobrota, C.E.; Tudoran, G.M.; Badea, O. Applications of TLS and ALS in evaluating forest ecosystem services: A southern carpathians case study. Forests 2021, 12, e1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, M.M.; Chillo, V.; Enríquez, A. Sustainable timber production in afforestations: Trade-offs and synergies in the provision of multiple ecosystem services in northwest Patagonia. For. Ecol. Manage. 2024, 574, e122345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutgesell, M.; McCann, K.; O’Connor, R.; KC, K.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Moore, J.C.; McMeans, B.; Donohue, I.; Bieg, C.; Ward, C.; et al. The productivity-stability trade-off in global food systems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 2135–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, D.G.; Blache, D.; Lockwood, A.L.; Maloney, S.K.; Norman, H.C.; Refshauge, G.; Hancock, S.N. Shelter and shade for grazing sheep: Implications for animal welfare and production and for landscape health. Animal Prod. Sci. 2023, 63, 623–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, N.; Timmins, H.L.; Stolton, S.; Watson, J.E. Effectively incorporating small reserves into national systems of protected and conserved areas. Diversity 2024, 16, e216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, J.S.; Childs, D.Z.; Carrasco, L.R.; Edwards, D.P. Indigenous lands in protected areas have high forest integrity across the tropics. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 4949–4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, E.R.; Conedera, M.; Bebi, P.; Zürcher, S.; Bareiss, A.; Ramstein, L.; Giacomelli, N.; Bottero, A. High potential but little success: Ungulate browsing increasingly impairs silver fir regeneration in mountain forests in the southern Swiss Alps. Forestry 2025, 98, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, C.A.; Berdugo, M.; Eldridge, D.J.; Eisenhauer, N.; Singh, B.K.; Cui, H.; Abades, S.; Alfaro, F.D.; Bamigboye, A.R.; Bastida, F.; et al. Global hotspots for soil nature conservation. Nature 2022, 610, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | H–O | H–Int | F–O | F–Int | A–O | A–Int | IMP |

| PL | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.51 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.38 | 0.45 |

| BL | 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.78 | 0.64 | 0.53 |

| PA | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.46 | 0.44 |

| F (p) |

1.97 (0.145) |

1.62 (0.204) |

0.92 (0.402) |

0.22 (0.801) |

| Level | DH | CC | BA | TOBV | PBA–M | VIG |

| PL | 5.2a | 45.48a | 17.7a | 64.9a | 89.35 | 1.78a |

| BL | 7.9b | 65.71b | 24.9ab | 110.7a | 80.58 | 1.95a |

| PA | 9.1b | 76.51b | 37.9b | 177.2b | 89.35 | 2.35b |

| F (p) |

27.48 (<0.001) |

20.98 (<0.001) |

12.46 (<0.001) |

18.92 (<0.001) |

0.98 (0.378) |

22.69 (<0.001) |

| Level | CAN | DSE | HSE | DSP | HSP | FI |

| PL | 9.4 | 48.8b | 21.8 | 1.53 | 1.78a | 0.30a |

| BL | 4.3 | 17.5ab | 29.7 | 1.24 | 1.94ab | 0.44b |

| PA | 3.3 | 8.1a | 21.0 | 1.56 | 2.48b | 0.64c |

| F (p) |

2.49 (0.088) |

4.29 (0.016) |

1.53 (0.221) |

0.05 (0.955) |

7.58 (0.001) |

27.54 (<0.001) |

| Level | SD | SWC | C | SOC | pH | SI |

| PL | 0.905b | 29.5a | 5.47a | 13.2a | 5.2 | 0.32a |

| BL | 0.775ab | 37.6ab | 9.82b | 18.0b | 5.4 | 0.47b |

| PA | 0.723a | 67.9b | 7.82b | 14.9ab | 5.3 | 0.43b |

| F (p) |

8.58 (<0.001) |

5.19 (0.007) |

6.39 (0.003) |

5.52 (0.005) |

0.68 (0.507) |

7.05 (0.001) |

| Level | SD | SWC | C | SOC | pH | SI |

| PL | 0.905b | 29.5a | 5.47a | 13.2a | 5.2 | 0.32a |

| BL | 0.775ab | 37.6ab | 9.82b | 18.0b | 5.4 | 0.47b |

| PA | 0.723a | 67.9b | 7.82b | 14.9ab | 5.3 | 0.43b |

| F (p) |

8.58 (<0.001) |

5.19 (0.007) |

6.39 (0.003) |

5.52 (0.005) |

0.68 (0.507) |

7.05 (0.001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).