1. Introduction

Thailand's beef cattle industry exhibits considerable variation in both population structure and production systems, with an estimated 9.6 million head nationwide [

1]. Beef cattle raised in Thailand were originally Thai native breeds, an indigenous type characterized by small body size, short hair, and variable coat color, typically weighing between 200 and 350 kg. Based on their genetic characteristics, beef cattle in Thailand are classified into three groups. The first group, accounting for approximately 61% of the population, consists of Thai native cattle belonging to the

Bos indicus species, including breeds such as White Lamphun, Kolan, and Kochon. These native cattle exhibit low growth rates, small body size, and relatively low carcass yields: heifers at 24 months weigh between 150 and 200 kg, steers weigh between 200 and 250 kg, and carcass yields average 32 to 33%, equivalent to roughly 50 to 60 kg per animal [

2,

3]. The second group consists of Brahman and Brahman-crossbred cattle, representing 35% of the national herd. These cattle are commonly used in production systems that rely on natural pastures and agricultural by-products. The third group, beef fattening cattle, includes hybrids produced by crossing Thai native or Thai Brahman cattle with

Bos taurus breeds such as Charolais, Beefmaster, Angus, and Wagyu. These high-grade hybrids are well adapted to Thailand’s climate and exhibit faster growth rates than traditional Thai cattle, although they still grow more slowly than purebred Western breeds. Beef finishing systems in Thailand typically aim to grow cattle efficiently to market weight, relying on Angus, Beefmaster, and Wagyu crossbreds selected for marbling and growth rate.

Beef consumers prioritize overall meat quality, which is influenced by attributes such as color, aroma, flavor, juiciness, and especially tenderness and intramuscular fat (marbling) [

4,

5,

6]. In Thailand, about 1% of cattle produce high-quality beef sold at premium prices, making meat quality improvement a key objective for producers [

7]. Although low cattle prices in 2007 reduced profitability, increasing demand from China and Vietnam shifted Thailand into the role of both exporter and transit hub for regional cattle movement [

4]. Cooperative production systems now play a central role, with contractual agreements among farmers, slaughterhouses, and retailers aimed at improving production capacity, processing efficiency, and supply chain management.

Meat tenderness is influenced by numerous environmental, biological, and postmortem factors, including animal age, fattening period, stress, carcass handling, cooling rate, muscle fiber type, connective tissue composition, glycogen reserves, and proteolytic activity [

8,

9]. Tenderness remains one of the most important attributes shaping consumer perception, yet substantial variation is still observed. The WBSF test is the standard method for evaluating tenderness, originating from early work by Warner and later refinements by Bratzler. Thresholds such as 4.1 kg have been proposed as indicators of consumer acceptability [

10], although variation among studies has led to the adoption of categorical classifications (<3.0 kg, 3.0–5.7 kg, >5.7 kg) as proposed by Wheeler et al. [

11]. Tenderness also varies among individual muscles, as demonstrated by Belew et al. [

12]. Postmortem biochemical processes, particularly glycolysis-driven pH decline and ATP depletion, govern the development of rigor mortis and structural changes within muscle. Improper early chilling may induce cold shortening, resulting in tougher meat, whereas maintaining muscle temperature near 15°C during rigor helps minimizes excessive contraction [

13]. Carcass suspension techniques can further influence sarcomere length and ultimately affect tenderness.

At the molecular level, proteolysis by endogenous enzymes is one of the most significant contributors to postmortem tenderization. This process proceeds optimally at approximately pH 6.3 and continues until enzymes lose activity [

14]. The calpain system, particularly micro-calpain (

CAPN1) and macro-calpain (

CAPN2), regulates postmortem protein degradation, with activity modulated by the endogenous inhibitor, calpastatin (

CAST).

CAPN1 and

CAPN2 are heterodimers composed of an 80 kDa catalytic subunit and a 28 kDa regulatory subunit, encoded on chromosomes 29 and 16, respectively. Calpastatin, encoded by a complex gene with 35 exons and multiple isoforms, inhibits calpain activity until postmortem calcium accumulation disrupts this interaction, thereby activating proteolysis [

15,

16,

17].

Genetic variability, particularly single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), plays a crucial role in the variation observed in meat tenderness. SNPs occur approximately every 700 base pairs (bp) in

Bos taurus and every 300 bp in

Bos indicus [

18]. Several SNPs within

CAPN1 and

CAST genes have been identified as important markers for meat tenderness. CAPN1 316 (AF252504:g.5709C>G) in exon 14 and CAPN1 4751 (AF248054.2:g.6545C>T) in intron 17 are associated with variation in shear force, with the CC genotype at both loci consistently linked to more tender meat [

19,

20,

21]. The CAST 2959 SNP (AF159246:g.2959G>A) located in the 3′UTR affects mRNA stability, altering calpastatin expression and thereby influencing tenderness; the A allele is associated with lower meat shear force [

22,

23]. These markers are already incorporated into commercial genetic tests for meat quality.

High-resolution melting (HRM) analysis is a rapid, PCR-based method for detecting genetic variation using third-generation intercalating dyes that bind to double-stranded DNA [

24]. Differences in a melting temperature (Tm) and curve profiles enable discrimination among SNP genotypes based on GC content, fragment length, and sequence composition [

25]. When combined with qPCR, HRM offers enhanced precision and resolution, making it highly suitable for genotyping

CAPN1 and

CAST markers in cattle.

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the association between micro-calpain gene markers (CAPN1 316 and CAPN1 4751) and the calpastatin gene marker (CAST 2959) with meat tenderness in crossbred beef cattle, and to develop quantitative PCR–high-resolution melting (qPCR-HRM) protocols for differentiating the CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 markers in these cattle.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Sample Collection

Beef samples were collected from crossbred cattle slaughtered at the Kamphaeng Saen Beef Cooperative Ltd. slaughterhouse between November 2023 and July 2024. The study population consisted of crossbred animals raised according to the cooperative’s regulations. A total of 86 individuals were selected based on available resources, recognizing that the relatively small sample size could limit statistical power and increase the risk of Type II error. Seven-day postmortem chilled meat samples were obtained from the Longissimus Dorsi muscle (12th to 13th thoracic vertebra), transported in iceboxes to maintain the cold chain, and stored at –20°C until analysis. Each sample was divided into two portions: one portion was processed for DNA extraction and SNP analysis, and the other portion was used to evaluate meat tenderness.

2.2. Molecular Analysis

For molecular analysis, genomic DNA was extracted from tissue using the proteinase-K, silica membrane column method following the FavorPrep™ Tissue Genomic DNA Extraction Mini Kit protocol (Favorgen Biotech Corp., Taiwan). Primers for detecting polymorphisms at CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 were designed using NCBI Primer-BLAST (

Table 1). qPCR-HRM reactions were prepared in a total volume of 20 μL, containing 20 ng of genomic DNA, 250 nM of each primer, 10 μL of SsoFast™ EvaGreen® Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA), and RNase/DNase-free water to achieve the final volume (

Table 2). PCR cycling conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 4 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, annealing at 59.6°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 10 seconds. HRM analysis was performed from 65°C to 95°C with 0.02°C-per-second increments, and normalized melting curves were generated using Bio-Rad CFX Manager™ 3.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Genotyping accuracy was validated by sequencing selected qPCR products using BTSeq™ (Barcode-Tagged Sequencing™) technology (Celemics, Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea) by U2Bio (Thailand) Co., Ltd. (Bangkok, Thailand). Resulting sequence data were analyzed using BioEdit v7.2.5.

2.3. Meat Tenderness Measurement by Warner-Bratzler Shear Force Method

Meat tenderness was assessed using the Warner–Bratzler shear force (WBSF) test. Steak samples were cut to approximately 1 inch in thickness in a chilled environment, vacuum-packed, and stored at –20°C until analysis. Before testing, frozen samples were thawed at 2–5°C for 24 hours, and 3 g of tissue was collected for DNA extraction. The remaining steak was then vacuum-repacked for cooking. Steaks were cooked in hot water at 95–100°C until reaching an internal temperature of 71°C, with a maximum cooking time of 30 minutes. After cooking, samples were cooled to 2–5°C before coring. Six cylindrical cores (1.2 cm in diameter and approximately 4 cm in length) were extracted from each steak parallel to the muscle fiber orientation. Cores that were misaligned, uneven in diameter, or contained excessive connective tissue were excluded. Shear force measurements were performed using a Brookfield AMETEK® CT3 25K texture analyzer (AMETEK Brookfield, Middleboro, MA, USA). Each core was sheared once at the center, perpendicular to the muscle fibers, at a crosshead speed of 3.8 mm/sec (290 mm/min). The mean shear force of the six cores was calculated for each sample to determine meat tenderness.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Allelic and genotypic frequencies of CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 were calculated, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was tested using the chi-square method.

General formula of Hardy-Weinberg equation

The p represents the frequency of the dominant allele, and q represents the frequency of the recessive allele. p² is the frequency of individuals dominating the homozygous dominant genotype, 2pq is the frequency of heterozygous individuals, and q² is the frequency of individuals dominating the homozygous recessive genotype.

A Chi-squared test of

x2 was used to determine whether observed genotypic frequencies deviate significantly from the expected frequencies given HWE:

where

O is the observed frequency and

E is the expected frequency. Degrees of freedom for Chi-squared test were calculated by number of genotypes minus 1. A

p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant, suggesting deviation from HWE.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between markers was evaluated using D, D′, and r² coefficients to examine non-random associations between loci.

The D, linkage disequilibrium estimate, is raw difference in frequency between the observed number of AB pairs and the expected allele distributions under independence assumption. The amount of such deviation is represented by the scalar D in estimated as followed:

The LD was estimated using the raw D, then scaled as D′, linkage disequilibrium estimate spanning the range [-1,1].

The effect of SNP markers on meat tenderness was assessed by first fitting a linear model to adjust WBSF values for fixed effects including marbling score, fattening period, permanent teeth, live weight, hot carcass weight, and coefficient of variation.

First fitted linear equation

where

Yijklmno is the WBSF value, μ is the grand mean, MAR is the fixed effect of the ith marbling score, FAT is the fixed effect of the jth fattening period in month, TEE is the fixed effect of the kth effect of permanent teeth as a surrogate measure of cattle age, WEI is the fixed effect of the lth live weight, CAR is the fixed effect of the mth hot carcass weight, CV is the fixed effect of the nth coefficient of variation of WBSF and ε

ijklmno is the random residual error for individuals oth of ith, jth, lth ,kth, mth, and nth. The residuals from this first fitted linear model, referred to as the residual-adjusted model for adjusted WBSF (aWBSF) in the mixed-effect model.

The residual-adjusted model for adjusted WBSF (aWBSF) values were then used in a linear mixed effects model to evaluate the association of each genotype (CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959) with meat tenderness, converting genotypes into dummy variables representing favorable alleles (0, 1, or 2). The linear mixed effects model as followed:

where

Ypqrs is the WBSF value, μ is the grand mean, T1 is the fixed effect of the pth genotype of CAPN1 316 marker (CC = 2, CG = 1 and GG = 0), T2 is the fixed effect of the qth genotype of CAPN1 4751 marker (CC = 2, CT = 1 and TT = 0), T3 is the fixed effect of the rth genotype of CAST 2959 marker (AA = 2, AG = 1 and GG = 0), R

WBSF is the fixed effect of the sth genotype of adjusted WBSF, Z

farm is the random effect of farms and ε

pqrsis the residual error.

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.5.0 [

26]. The statistical significance was set at

p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. SNPs Genotyping by HRM

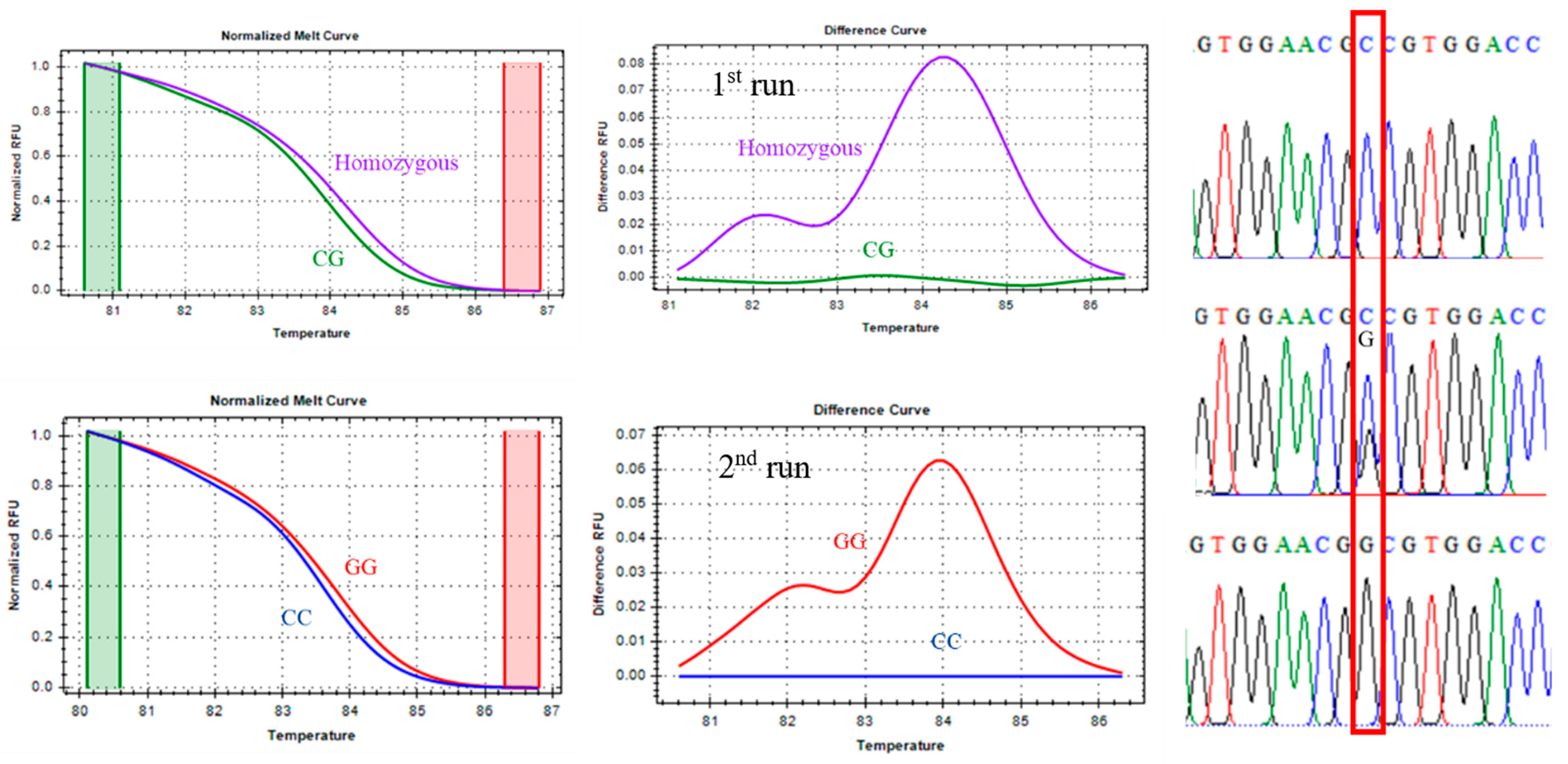

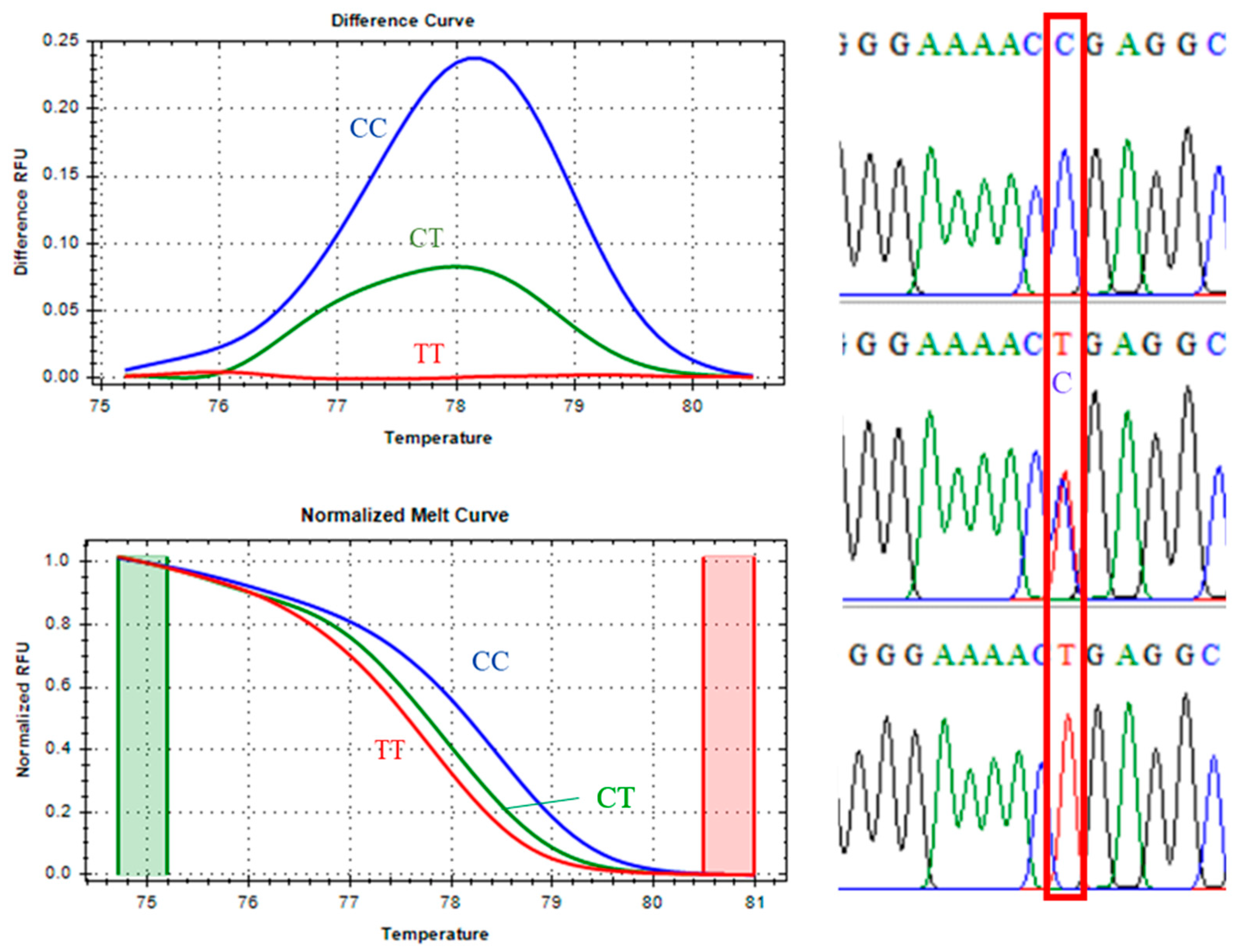

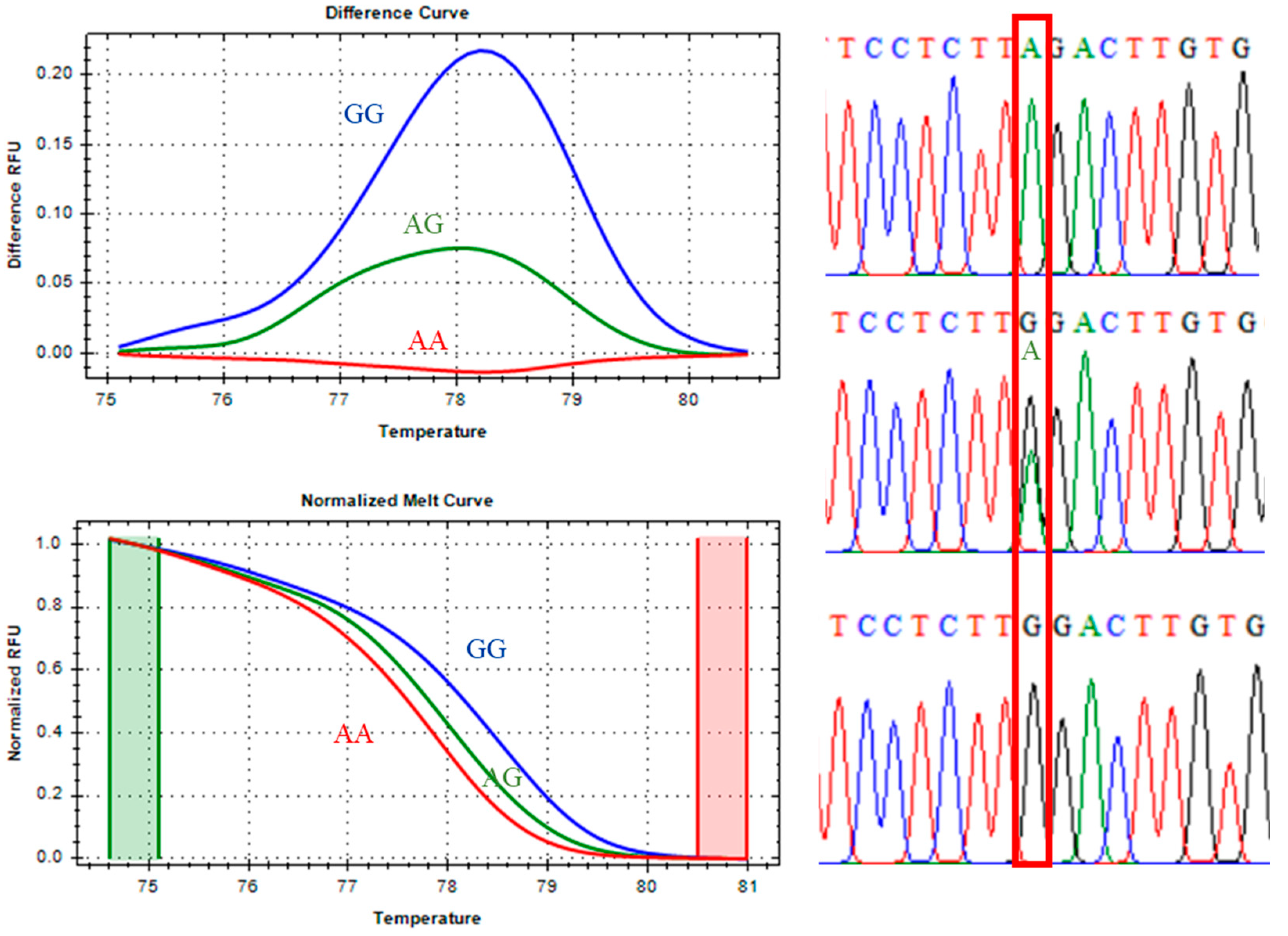

The quantitative polymerase chain reaction with high-resolution melting analysis (qPCR-HRM) using the newly developed primers enabled clear discrimination between heterozygous and homozygous genotypes for the CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 tenderness markers. Each marker produced distinct and highly reproducible melting curve profiles across replicates, demonstrating the reliability of the method.

The amplicons generated for these markers were approximately 80–90 bp in length, indicating that the primer design effectively amplified the intended regions while minimizing non-specific amplification. The melting temperatures (Tm) were highly sensitive to genotype differences, with homozygous and heterozygous genotypes displaying clearly distinguishable melting transitions.

Direct DNA sequencing of positive controls confirmed the accuracy of the genotype assignments inferred from melting curve profiles. Each genotype exhibited a unique melting transition and corresponding Tm differences, as summarized in

Table 3. Selected genotypic variants were further validated by Sanger sequencing (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), supporting the precision and robustness of the qPCR-HRM genotyping approach.

3.1.1. CAPN1 316 Marker Genotyping

For the CAPN1 316 marker, classified as a class III SNP, distinct melting behaviors were observed between homozygous and heterozygous genotypes. As shown in

Figure 1, the heterozygous genotype (green line) exhibited a melting profile clearly different from the homozygous genotype cluster (violet line). However, differentiating between the two homozygous genotypes—CC (favorable, blue line) and GG (unfavorable, red line)—was challenging due to their highly similar Tm values and melting curve patterns.

To address this limitation, the analysis first focused on accurately distinguishing homozygous from heterozygous samples. Subsequently, the method described by Liew et al. (2004) [

27] was applied to enhance resolution between homozygous genotypes. This approach involved spiking approximately 30% wild-type homozygous DNA into the reaction mixture to induce heteroduplex formation, thereby increasing the sensitivity of the melting curve analysis. The effectiveness of this strategy in separating the CC and GG genotypes is demonstrated in

Figure 1.

3.1.2. CAPN1 4751 Marker Genotyping

For the CAPN1 4751 marker, classified as a class I SNP,

Figure 2 shows clear discrimination among the homozygous CC (blue line), heterozygous CT (green line), and homozygous TT (red line) genotypes in both the normalized melt curves and the melting-difference curves. This distinct separation allowed accurate and straightforward genotype identification. Sanger sequencing of selected samples confirmed the presence of the expected nucleotide substitutions for each genotype, validating the reliability of the qPCR-HRM analysis for this marker.

Melting peak analysis demonstrated that the CC genotype had the highest Tm at 85.00°C, consistent with the greater stability of C–G base pairs, which contain three hydrogen bonds. The heterozygous CT genotype had a Tm of 84.80°C, while the TT genotype melted at 84.40°C, reflecting the lower thermal stability of T–A base pairs with only two hydrogen bonds. The stepwise decrease in Tm was therefore consistent with the reduced number of hydrogen bonds in each genotype. Minor mutations adjacent to the SNP site were detected in some samples, as indicated by slight variations in melting profiles.

3.1.3. CAST 2959 Marker Genotyping

The CAST 2959 marker, classified as a class I SNP, displayed distinct melting profiles for all three genotypes. As shown in

Figure 3, the unfavorable homozygous GG genotype (blue line), the heterozygous AG genotype (green line), and the favorable homozygous AA genotype (red line) were clearly differentiated in both the melting-difference curves and the normalized melt curves. Sanger sequencing confirmed the expected nucleotide substitutions in each genotype, further validating the reliability of qPCR-HRM for CAST 2959 genotyping.

Melting peak analysis revealed that the favorable AA genotype had a Tm of 77.80°C, the heterozygous AG genotype melted at 78.00°C, and the unfavorable GG genotype at 78.40°C. These differences reflect inherent variations in hydrogen bonding stability, with G–C base pairs producing higher thermal stability (and therefore higher Tm) than A–T pairs.

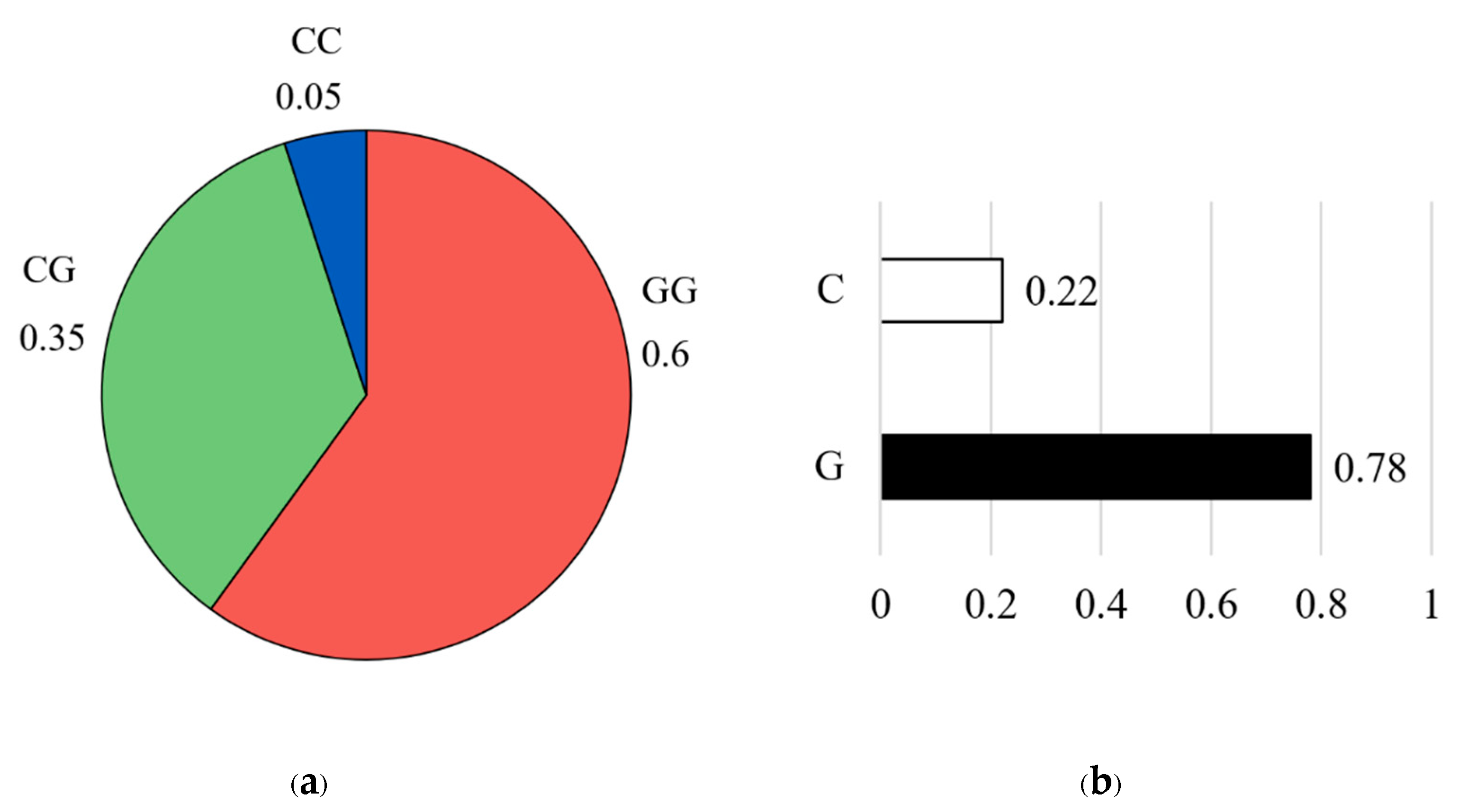

3.2. Genotype and Allele Frequencies

For the CAPN1 316 marker, the genotype distribution showed that the homozygous GG genotype was the most prevalent, accounting for 60% of the population (n = 46), followed by the heterozygous CG genotype at 35% (n = 30), and the homozygous CC genotype at 5% (n = 4) (

Figure 4a). Allele frequency analysis further indicated that the unfavorable G allele was predominant (G = 0.78), while the favorable C allele was less common (C = 0.22) (

Figure 4b).

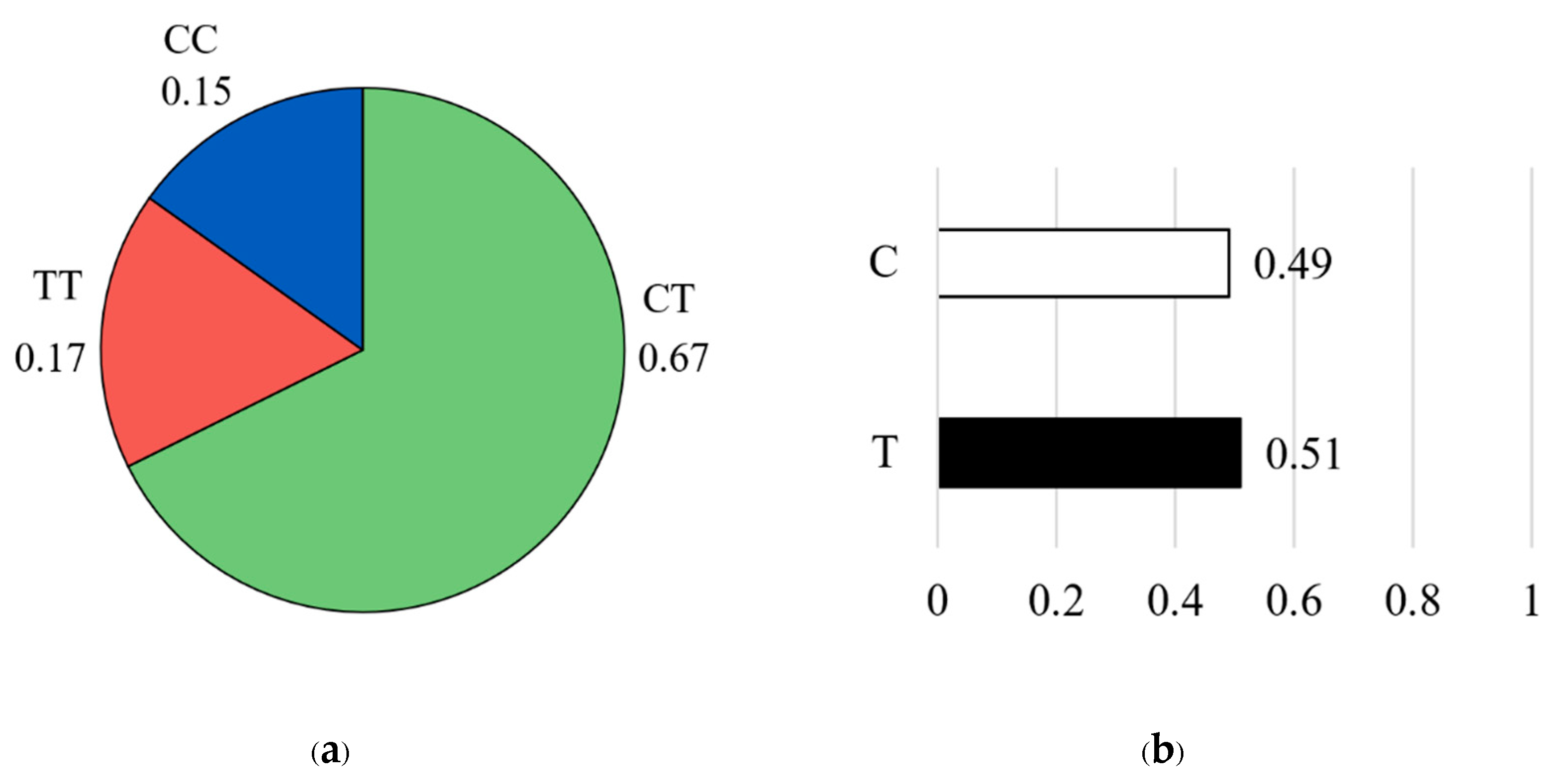

For the CAPN1 4751 marker, genotype frequencies showed that the heterozygous CT genotype was the most common, accounting for 67% of the population (n = 58). This was followed by the homozygous TT genotype at 17% (n = 15) and the homozygous CC genotype at 15% (n = 13) (

Figure 5a). Allele frequency analysis revealed an almost equal distribution of the favorable C allele and the unfavorable T allele, with the T allele being slightly more frequent (T = 0.51, C = 0.49) (

Figure 5b).

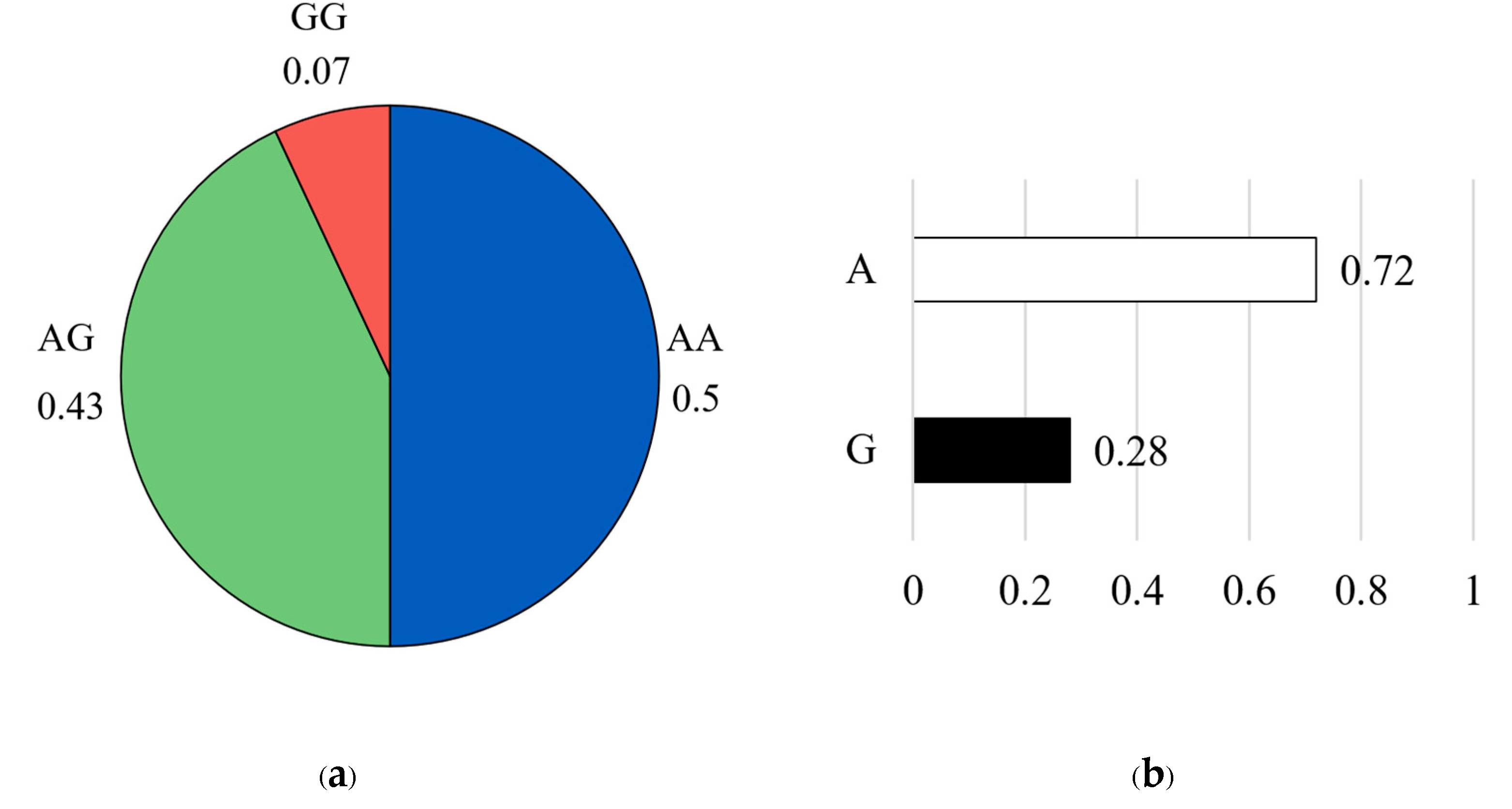

For the CAST 2959 marker, the genotype distribution showed that the favorable homozygous AA genotype was the most common, representing approximately 50% of the population (n = 43). This was followed by the heterozygous AG genotype at 43% (n = 37), while the unfavorable homozygous GG genotype was rare, occurring in only 7% of individuals (n = 6) (

Figure 6a). Allele frequency analysis further confirmed the high prevalence of the favorable A allele (A = 0.72) compared with the G allele (G = 0.28) (

Figure 6b).

These results demonstrate varying distributions of favorable and unfavorable alleles across the three markers, which may have important implications for selection strategies aimed at improving meat tenderness in the studied crossbred beef population.

Table 4 summarizes the distribution of genotype combinations obtained from the three single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers—CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959. Theoretically, a total of 27 possible genotype combinations can arise from these three loci; however, only 13 combinations were observed in the sampled population. The observed genotype combinations, along with their corresponding counts and frequencies, are presented in descending order of occurrence.

Among all detected combinations, GG/CT/AA was the most frequent, occurring in 17 samples (23%), followed by GG/CT/AG with 13 samples (18%), and CG/CT/AA with 9 samples (12%), all of which represented a substantial proportion of the population. In contrast, some genotype combinations—such as CG/TT/GG and GG/TT/GG—were rare, each occurring in only one sample (<1%).

3.3. Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

The HWE test was done for each CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 genotypes by comparing the observed genotype counts and the expected genotype counts.

For the CAPN1 316 marker, the CC genotype had an expected count below five, making Fisher’s exact test more appropriate than Pearson’s chi-square test for assessing Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium at this locus. The test yielded a p-value of 1.0, indicating that the population is in equilibrium, with the observed genotype frequencies closely matching the expected values (

Table 5). Overall, the G allele is the dominant allele at CAPN1 316, and the population at this marker is in HWE, with no evidence of selection, inbreeding, or other evolutionary forces acting on this locus.

The HWE test for the CAPN1 4751 locus revealed a significant deviation from equilibrium assumptions (χ² = 10.51, p = 0.0016). The observed genotype frequencies differed markedly from those expected under HWE (

Table 6). Specifically, the number of observed heterozygotes (CT) was substantially higher than expected (58.00 observed vs. 42.98 expected), whereas both homozygous genotypes were less frequent than expected (CC: 13 observed vs. 20.51 expected; TT: 15 observed vs. 22.51 expected). This significant deviation from HWE (p < 0.05) indicated that one or more assumptions of the Hardy–Weinberg model may be violated in this population, potentially due to non-random mating, selection pressure, genetic drift, or other evolutionary forces acting on this locus.

For CAST 2959, the observed and expected genotype counts were nearly identical (

Table 7), and the p-value of 0.54 was much greater than 0.05. This indicated that the studied population is in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) at this locus. Overall, the A allele was the dominant allele at CAST 2959, and the population showed no evidence of selection, inbreeding, or other evolutionary forces acting on this marker.

3.4. Linkage Disequilibrium

Pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis among the three SNP loci (CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959) revealed varying degrees of non-random association. The LD between CAPN1 316 and CAPN1 4751 was intermediate in terms of D′ (0.2672), but showed very low allelic association (r² = 0.0212), with the chi-square test indicating marginal significance (χ² = 3.649, p = 0.056). This suggests only a weak tendency toward linkage and minimal shared allele variance between these loci. The LD between CAST 2959 and CAPN1 316 was even lower, with D′ = 0.1076 and r² = 0.0083, and the association was not statistically significant (χ² = 1.419, p = 0.234), demonstrating largely independent segregation in the population. In contrast, CAST 2959 and CAPN1 4751 exhibited the strongest evidence of LD among all marker pairs, with an intermediate D′ value (0.4731), low but higher r² (0.0851), and a highly significant chi-square result (χ² = 14.642, p = 0.00013). These results indicate a statistically non-random association in which approximately 8.5% of the variation at one locus can be explained by the other. The average pairwise LD across all three SNPs was intermediate, with a mean D′ of approximately 0.283, largely driven by the LD between CAPN1 4751 and CAST 2959, while the other pairs contributed much lower LD. The near-independence between CAPN1 316 and CAST 2959 suggests that these markers provide complementary and non-overlapping genetic information for mapping or association analyses. In contrast, the moderate LD between CAST 2959 and CAPN1 4751 may reflect physical proximity or shared selective pressures, potentially making either marker useful as a tag SNP when genotyping resources are limited. Overall, the generally intermediate LD observed among the markers supports the inclusion of all three SNPs to more comprehensively capture genetic variation related to meat quality traits.

3.5. Warner-Bratzler Shear Force Measurement

The Warner–Bratzler shear force (WBSF) test was used to evaluate meat tenderness in the study population (n = 86), with six replicate shear-force measurements obtained for each sample and the mean value recorded in grams. As shown in

Table 8, the mean WBSF was 3,868.63 g with a standard deviation of 1,252.01 g, while the minimum and maximum values were 1,604.70 g and 7,220.00 g, respectively; the median was 3,621.84 g, and the mode was 2,480.00 g. The distribution of shear-force values was approximately normal, supported by the close correspondence between the mean and median and the generally symmetrical spread of the data. The interquartile range (IQR) extended from 2,774.17 g (Q1) to 4,913.00 g (Q3), reflecting the central tendency and variability of meat tenderness within the population. Overall, these results indicate substantial variation in WBSF values and support the assumption of normality, thereby justifying the use of parametric statistical methods for subsequent genotype–phenotype association analyses.

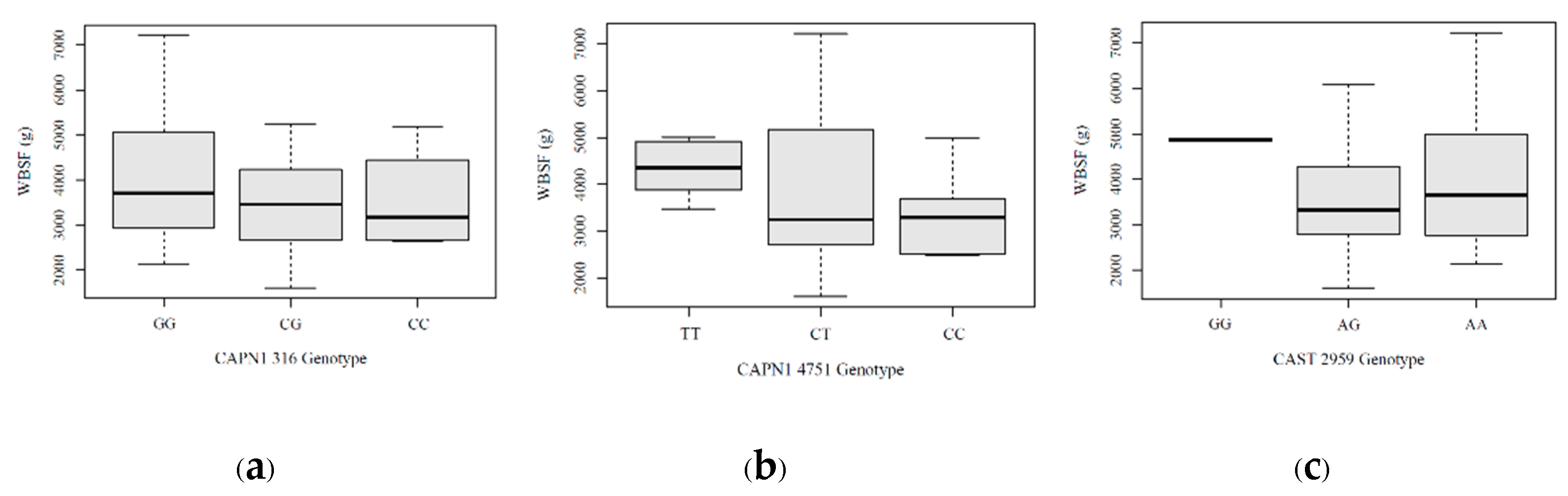

As shown in

Figure 7, the association between genotypes and meat tenderness measured by WBSF revealed distinct patterns across the three markers. For CAPN1 316, the CC genotype was rare (n = 4) and exhibited a mean WBSF of 3,552 g, while the CG genotype (n = 30) showed a mean WBSF of 3,675 g, and the GG genotype (n = 49) had the highest mean WBSF at 4,001 g, indicating a trend toward tougher beef associated with the G allele. For CAPN1 4751, the CC genotype (n = 12) had the lowest mean WBSF value at 3,294 g, followed by the CT genotype (n = 57) with a mean of 3,901 g, whereas the TT genotype (n = 14) exhibited the highest mean WBSF at 4,191 g, suggesting a possible association between the T allele and tougher beef. For CAST 2959, the AA genotype was the most common and had a mean WBSF of approximately 3,883 g with a wide range (2,053.50 to 7,220.00 g). The AG genotype showed a slightly lower mean WBSF of 3,693 g with a similar distribution, while the GG genotype, although rare (n = 5), exhibited the highest mean WBSF at 4,865 g—suggesting tougher beef, but with limited interpretive confidence due to the small sample size.

3.6. Significant SNP Marker Associations with Beef Tenderness

3.6.1. Relationship Between Each Marker and Adjusted Warner–Bratzler Shear Force

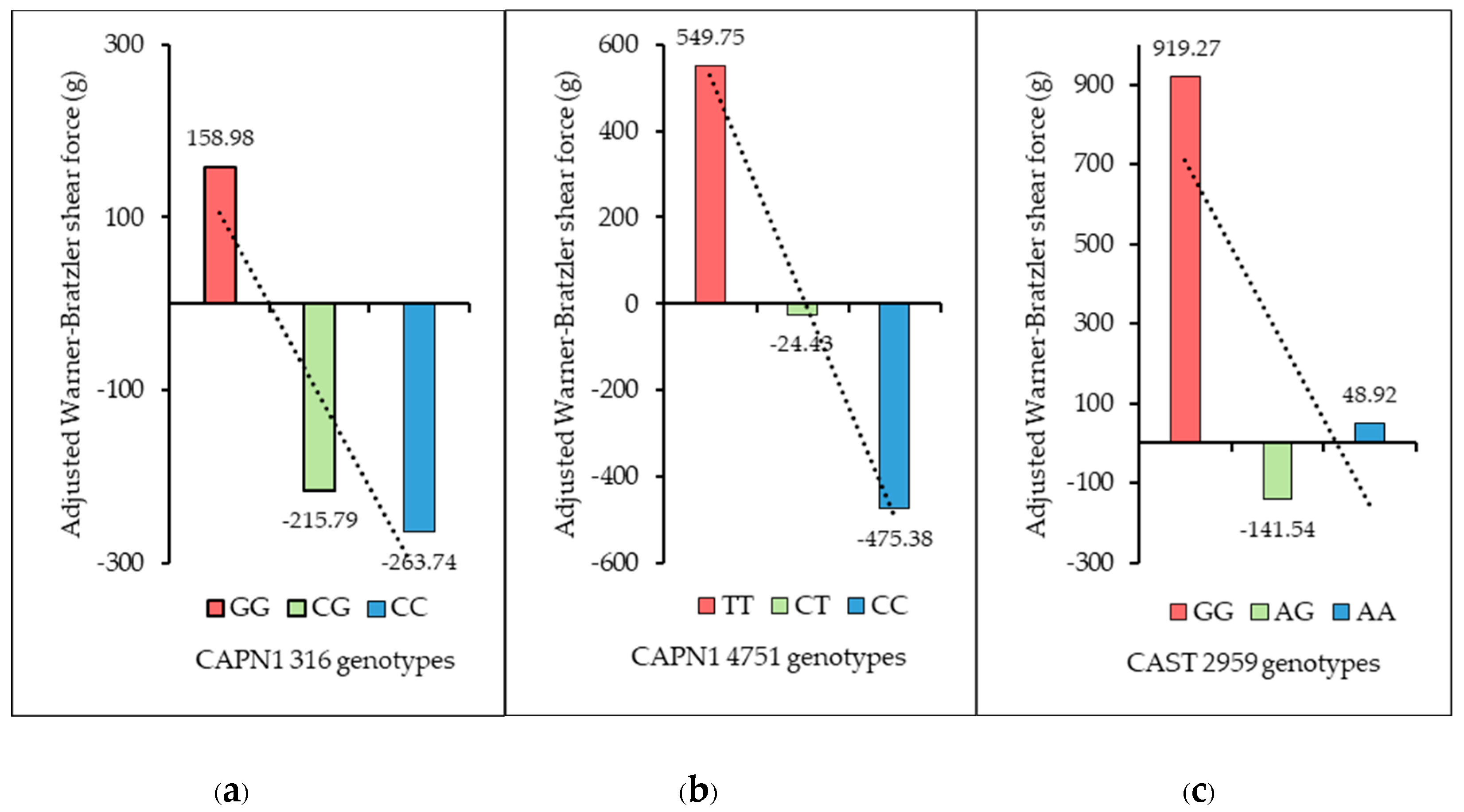

As shown in

Figure 8, the relationship between the genotypes of CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 and the adjusted Warner–Bratzler shear force (aWBSF) values revealed clear patterns in meat tenderness across all three markers. For CAPN1 316, the unfavorable GG genotype exhibited the highest mean aWBSF (158.98 g), followed by the CG genotype (–215.79 g) and the favorable CC genotype (–263.74 g), with corresponding standard deviations of 1333.36 g, 989.61 g, and 1150.50 g, respectively—showing a decreasing trend in aWBSF from GG to CC. For CAPN1 4751, the unfavorable TT genotype showed the highest mean aWBSF (549.75 g), followed by the CT genotype (–24.43 g) and the favorable CC genotype (–475.38 g), with standard deviations of 648.44 g, 1335.80 g, and 726.31 g, respectively, again demonstrating a decreasing pattern from TT to CC. For CAST 2959, the unfavorable GG genotype had the highest mean aWBSF (919.27 g), followed by AA (48.92 g), while the AG genotype exhibited the lowest mean aWBSF (–141.54 g), with standard deviations of 489.97 g, 1112.19 g, and 1302.62 g, respectively—indicating a decreasing trend from GG to AG, with a slight increase at AA. Overall, these patterns suggest that favorable alleles across the three loci were consistently associated with lower adjusted WBSF values and therefore improved meat tenderness.

3.6.2. Significant Marker Combination Associations with Beef Tenderness

After adjusting WBSF values using the first fitted linear model and conducting a second linear model with pairwise comparison analysis, the results indicate that allelic substitution at the CAPN1 4751 locus exerts the strongest and most consistent influence on meat tenderness among the markers evaluated. As shown in

Table 9, a significant association was detected between the CG/TT/AA and CG/CC/AA genotype combinations (CAPN1 316 / CAPN1 4751 / CAST 2959), with a substantial difference of 792.24 ± 207.98 g in WBSF values (p = 0.02). This demonstrates that animals carrying the CG/TT/AA combination produce significantly tougher meat than those with the CG/CC/AA combination. Two additional contrasts in which TT animals were compared with CC or CT genotypes at CAPN1 316 yielded similar effect sizes (523.34 ± 172.62 g and 565.89 ± 187.72 g, respectively), although their p-values (0.052–0.056) indicated marginal statistical significance.

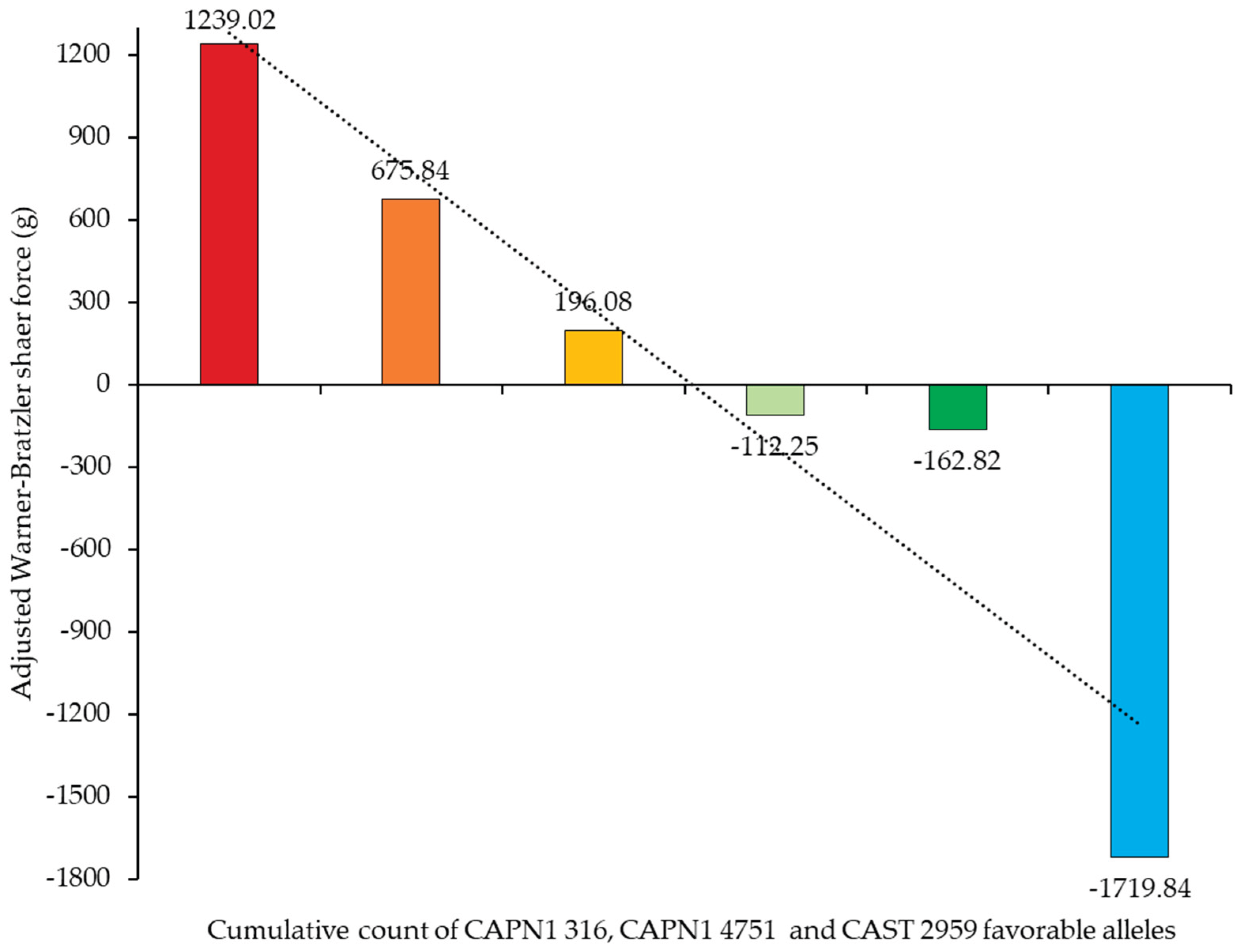

Figure 9 demonstrates the association between the cumulative count of favorable alleles of the CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 marker and the corresponding aWBSF values. A clear negative trend was observed, indicating that as the number of favorable alleles increased, aWBSF values decreased. This pattern suggested that favorable alleles at these loci exerts an additive effect on improving meat tenderness. Beef samples with no favorable alleles exhibited the highest aWBSF values, whereas those carrying five favorable alleles showed the lowest value, suggesting a cumulative genetic effect of

CAPN1 and

CAST on reducing shear force and enhancing beef tenderness.

4. Discussion

In this study, we used qPCR-HRM to genotype SNPs at CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751 and CAST 2959 loci, which were associated with beef tenderness. Our results indicated that the TT genotype of CAPN1 4751 was a consistent indicator of tougher beef, as evidenced by significantly higher WBSF values, making it a reliable marker for tenderness prediction. In contrast, the CAST 2959 locus showed no significant phenotypic effect in the studied population. Although the combination of CAPN1 4751 and CAPN1 316 appeared to exert some influence on tenderness, the evidence remained inconclusive. These findings aligned with previous studies by Van Eenennaam, Li [

28] and White, Casas [

29], which also reported strong associations between the CAPN1 4751 and beef tenderness. Interpretation of these genetic effects must also account for pedigree-related factors, as the crossbred cattle population used in this study likely varied in their proportion of

Bos taurus and

Bos indicus ancestry, which differed in both SNP distribution and phenotypic expression. Such genetic heterogeneity added complexity to marker evaluation and highlighted the importance of larger sample sizes or detailed pedigree information to improve the accuracy of SNP effect estimates. Additionally, slaughtering, aging, and cooking conditions can influence meat tenderness. Although all samples were collected from a single slaughterhouse to minimize environmental variability, the relatively short 7-day aging period may have reduced proteolytic enzyme activity and limited the detectable influence of genetic differences compared with longer 14 – 21 days aging periods commonly used in tenderness studies [

30].

The HWE analysis provided additional insight into population structure. The CAPN1 316 locus showed genotype frequencies consistent with HWE, and Fisher’s exact test confirmed equilibrium despite the small expected count for the CC genotype, suggesting that random mating rather than selection was shaping allele distribution at this locus. The sample size (n = 86), although modest, was sufficient to detect moderate deviations and support the interpretation of genetic stability at CAPN1 316. In contrast, CAPN1 4751 significantly deviated from HWE (χ² = 10.51), showing an excess of CT heterozygotes and fewer CC and TT homozygotes than expected. This pattern may indicate heterozygote advantage, non-random mating, genetic drift, or sampling error; however, the consistent overrepresentation of heterozygotes suggested that evolutionary forces such as selection could be acting on this locus. A larger and more diverse sample was needed to determine whether selection was influencing CAPN1 4751 allele frequencies. Meanwhile, the CAST 2959 locus remained in equilibrium, with observed and expected genotype counts nearly identical, indicating that allele A is stable in the population and not strongly affected by selection or inbreeding. Although the relatively small sample size increases the likelihood of false negatives, the clear deviation observed only at CAPN1 4751 suggested that different evolutionary pressures may be influencing each of the three loci.

The analysis of LD revealed that the CAST 2959 × CAPN1 4751 pair exhibited a low level of association (r² = 0.0851) but the moderate degree of linkage disequilibrium (D’ = 0.4731), accompanied by a highly significant chi-squared value (χ² = 14.642). Despite this, the negative correlation (r = −0.2918) indicated an inverse allelic relationship, in which the minor allele of CAPN1 4751 was frequently associated with the major allele of CAST 2959. Such patterns may reflect historical recombination events or selective breeding pressures that have shaped current haplotype structures. In contrast, LD among the remaining marker pairs was low, and the average D′across all pairs (approximately 0.283) indicated overall weak to moderate linkage, supporting the absence of strong linkage blocks and suggesting that each SNP contributes independent genetic information. This independence is advantageous for association mapping, particularly between CAPN1 316 and CAST 2959, while the significant chi-square value for CAPN1 4751 and CAST 2959 suggested that a tag SNP may be useful when resources are limited. Collectively, the LD patterns support the use of all three SNPs to capture broader genetic variation associated with meat quality traits.

Moreover, the study demonstrated that qPCR-HRM was an efficient, sensitive, and cost-effective method for SNP genotyping, provided that primer design was sufficiently specific to prevent the formation of multiple melting domains and that sequencing-verified positive controls were included. Although class III and IV SNPs remain challenging to differentiate, such as CAPN1 316, due to the formation of double-stranded DNA stabilized by an equal number of hydrogen bonds, the characteristics of the amplicon generated by the novel primers, combined with the resolution limits of the Bio-Rad CFX Connect Real-Time PCR System may further restrict the discriminatory ability of this technique.

The qPCR-HRM is applicable to tissue, blood, or semen samples, making it suitable for integration into commercial breeding programs. Looking forward, although CAPN1 4751 emerged as a strong candidate marker for beef tenderness, incorporating additional SNPs associated with other meat quality traits and exploring multiplex qPCR-HRM could further enhance the precision of genetic selection and the efficiency of high-throughput screening. Future research should also assess economic feasibility and conduct longitudinal studies to evaluate the long-term effects of selection based on CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 on meat quality improvement and overall cattle production profitability.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, qPCR-HRM represents a promising and efficient approach for improving beef tenderness and other economically important genetic traits in cattle, offering significant potential to enhance genetic improvement, meat quality, and the long-term efficiency, profitability, and sustainability of livestock breeding programs. When integrated with other genomic tools, this technology provides a practical pathway for the genetic advancement of beef cattle populations, such as those in Thailand, where the beef industry is a substantial component of the agricultural sector. In this study, polymorphisms at CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 markers exhibited interactive effects on meat quality traits, with the TT genotype at CAPN1 4751 notably increasing adjusted WBSF by approximately 792 g, clearly identifying it as an unfavorable variant for tenderness. The observed confidence interval, ranging from 72.85 to 1,512.64 g, underscores the strength of the genetic signal and confirms that these three markers act polygenically rather than in isolation. These robust marker effects provide a solid foundation for marker-assisted selection strategies aimed at managing the TT genotype at CAPN1 4751, while also monitoring secondary loci, thereby accelerating genetic gain in meat tenderness across commercial cattle populations. Overall, these findings highlight the polygenic nature of meat tenderness and emphasize the importance of using multiple SNPs markers in combination to accurately describe the genetic potential for meat quality traits in cattle populations.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, T.T.; S.T.; P.L. and T.R.; methodology, T.T.; S.T.; P.L.; N.H. and T.R.; software, T.T. and N.H.; validation, T.T.; S.T. and N.H.; formal analysis, T.T. and N.H.; investigation, T.T.; resources, S.T.; P.L. and T.R.; data curation, T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.; writing—review and editing, S.T.; P.L.; N.H. and T.R.; visualization, T.T.; supervision, T.R.; project administration, T.T..; funding acquisition, T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC was funded by Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for the study because the animals were slaughtered for commercial purposes and not specifically for research. Only carcass tissues from animals certified as fit for human consumption by veterinary authorities were used. Therefore, no live animals were handled, subjected to experimental procedures, or exposed to any additional harm or distress for the purpose of this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Molecular Laboratory Unit at Kamphaeng Saen Veterinary Diagnostic Center (KVDC) for providing facilities and equipment for this study; and Kamphaeng Saen Beef Cooperative Ltd. (KU-BEEF) for supplying beef samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, or significant financial support that could have influenced the outcome of this publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| aWBSF |

Adjusted Warner-Bratzler shear force |

| bp |

Base pairs |

| CAPN1 |

Micro-Calpain |

| CAST |

Calpastatin |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DNase |

Deoxyribonuclease |

| g |

Gram |

| HRM |

High-resolution melting analysis |

| kg |

Kilogram |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| qPCR |

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic acid |

| RNase |

Ribonuclease |

| Tm |

Melting temperature |

| μl |

Microliter |

| μM |

Micromolar |

| mg |

Milligram |

| pH |

Potential of hydrogen |

| SNPs |

Single nucleotide polymorphisms |

| WBSF |

Warner-Bratzler shear force |

References

- Department of Livestock Development (DLD). Livestock Statistics of Thailand, 2023. 2023. Available online: https://certify2.dld.go.th/livestock-in-thailand-2023 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Wangkumhang, P.; Wilantho, A.; Shaw, P.J.; Flori, L.; Moazami-Goudarzi, K.; Gautier, M.; Duangjinda, M.; Assawamakin, A.; Tongsima, S. Genetic analysis of Thai cattle reveals a Southeast Asian indicine ancestry. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yodsoi, S.; Chaiwang, N.; Yammuen-art, S.; Sringarm, K.; Suwansirikul, S.; Jaturasitha, S. Meat quality of Mountainous and white Lamphun cattle compared to Brahman crossbred. Khon Kaen Agr. J. 2013, 41 Suppl. 1), 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bunmee, T.; Chaiwang, N.; Kaewkot, C.; Jaturasitha, S. Current situation and future prospects for beef production in Thailand - A review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henchion, M.M.; McCarthy, M.; Resconi, V.C. Beef quality attributes: A systematic review of consumer perspectives. Meat Sci. 2017, 128, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R. Drivers of consumer liking for beef, pork, and lamb: A review. Foods 2020, 9, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackelford, S.D.; Wheeler, T.L.; Meade, M.K.; Reagan, J.O.; Byrnes, B.L.; Koohmaraie, M. Consumer impressions of tender select beef. J. Anim. Sci. 2001, 79, 2605–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špehar, M.; Vincek, D.; Žgur, S. Beef quality: factors affecting tenderness and marbling. Stočarstvo 2008, 62, 463–478. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, S.H.A.; Kaster, N.; Khan, R.; Abdelnour, S.A.; El-Hack, M.E.A.; Khafaga, A.F.; Taha, A.; Ohran, H.; Swelum, A.A.; Schreurs, N.M.; Zan, L. The role of microRNAs in muscle tissue development in beef cattle. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, K.L.; Miller, M.F.; Hoover, L.C.; Wu, C.K.; Brittin, H.C.; Ramsey, C.B. Effect of beef tenderness on consumer satisfaction with steaks consumed in the home and restaurant. J. Anim. Sci. 1996, 74, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, T.; Shackelford, S.; Koohmaraie, M. Standardizing collection and interpretation of Warner-Bratzler shear force and sensory tenderness data. Proc. Recip. Meat Conf. 1997, 50, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Belew, J.B.; Brooks, J.C.; McKenna, D.R.; Savell, J.W. Warner–Bratzler shear evaluations of 40 bovine muscles. Meat Sci. 2003, 64, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devine, C.E.; Wahlgren, N.M.; Tornberg, E. Effect of rigor temperature on muscle shortening and tenderisation of restrained and unrestrained beef m. longissimus thoracicus et lumborum. Meat Sci. 1999, 51, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dransfield, E. Optimisation of tenderisation, ageing and tenderness. Meat Sci. 1994, 36, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynaud, P.; Gillard, M.; Parr, T.; Bardsley, R.; Amarger, V.; Levéziel, H. Correlation between bovine calpastatin mRNA transcripts and protein isoforms. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005, 440, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.L.; Davies, P.L. Structure–function relationships in calpains. Biochem. J. 2012, 447, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveau, C.; Lundén, A.; Lundström, K.; Examensarbete; Näsholm, A. Candidate genes for beef quality – allele frequencies in Swedish beef cattle by Carina Leveau. 2008. Available online: https://stud.epsilon.slu.se/11165/1/leveau_c_170926.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Seidel, G.E. Brief introduction to whole-genome selection in cattle using single nucleotide polymorphisms. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2009, 22, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, B.T.; Casas, E.; Heaton, M.P.; Cullen, N.G.; Hyndman, D.L.; Morris, C.A.; Crawford, A.M.; Wheeler, T.L.; Koohmaraie, M.; Keele, J.W.; Smith, T.P.L. Evaluation of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in CAPN1 for association with meat tenderness in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 80, 3077–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, E.; White, S.N.; Riley, D.G.; Smith, T.P.L.; Brenneman, R.A.; Olson, T.A.; Johnson, D.D.; Coleman, S.W.; Bennett, G.L.; Chase, C.C., Jr. Assessment of single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes residing on chromosomes 14 and 29 for association with carcass composition traits in Bos indicus cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 83, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curi, R.A.; Chardulo, L.A.L.; Mason, M.C.; Arrigoni, M.D.B.; Silveira, A.C.; de Oliveira, H.N. Effect of single nucleotide polymorphisms of CAPN1 and CAST genes on meat traits in Nellore beef cattle (Bos indicus) and in their crosses with Bos taurus. Anim. Genet. 2009, 40, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.A.; Cullen, N.G.; Hickey, S.M.; Dobbie, P.M.; Veenvliet, B.A.; Manley, T.R.; Pitchford, W.S.; Kruk, Z.A.; Bottema, C.D.K.; Wilson, T. Genotypic effects of calpain 1 and calpastatin on the tenderness of cooked M. longissimus dorsi steaks from Jersey×Limousin, Angus and Hereford-cross cattle. Anim. Genet. 2006, 37, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattrass, G.S.; Cafe, L.M.; McIntyre, B.L.; Gardner, G.E.; McGilchrist, P.; Robinson, D.L.; Wang, Y.H.; Pethick, D.W.; Greenwood, P.L. A post-transcriptional mechanism regulates calpastatin expression in bovine skeletal muscle. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittwer, C.T.; Reed, G.H.; Gundry, C.N.; Vandersteen, J.G.; Pryor, R.J. High-resolution genotyping by amplicon melting analysis using LCGreen. Clin. Chem. 2003, 49, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, G.H.; Kent, J.O.; Wittwer, C.T. High-resolution DNA melting analysis for simple and efficient molecular diagnostics. Pharmacogenomics 2007, 8, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Liew, M.; Pryor, R.; Palais, R.; Meadows, C.; Erali, M.; Lyon, E.; Wittwer, C. Genotyping of single-nucleotide polymorphisms by high-resolution melting of small amplicons. Clin. Chem. 2004, 50, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eenennaam, A.L.; Li, J.; Thallman, R.M.; Quaas, R.L.; Dikeman, M.E.; Gill, C.A.; Franke, D.E.; Thomas, M.G. Validation of commercial DNA tests for quantitative beef quality traits. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.N.; Casas, E.; Wheeler, T.L.; Shackelford, S.D.; Koohmaraie, M.; Riley, D.G.; Chase, C.C., Jr.; Johnson, D.D.; Keele, J.W.; Smith, T.P.L. A new single nucleotide polymorphism in CAPN1 extends the current tenderness marker test to include cattle of Bos indicus, Bos taurus, and crossbred descent. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 83, 2001–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Eler, J.P.; Bonin, M.N.; Rezende, F.M.; Biase, F.H.; Meirelles, F.V.; Regitano, L.C.A.; Coutinho, L.L.; Balieiro, J.C.C.; Ferraz, J.B.S. Genotypic and allelic frequencies of gene polymorphisms associated with meat tenderness in Nellore beef cattle. Genet. Mol. Res. 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

CAPN1 316 marker, melting curve, and Sanger sequencing confirmation. (*The first run was performed to discriminate between homozygous and heterozygous genotypes. The second run was performed only on homozygous samples to discriminate between homozygous CC and GG genotypes in the CAPN1 316 marker.).

Figure 1.

CAPN1 316 marker, melting curve, and Sanger sequencing confirmation. (*The first run was performed to discriminate between homozygous and heterozygous genotypes. The second run was performed only on homozygous samples to discriminate between homozygous CC and GG genotypes in the CAPN1 316 marker.).

Figure 2.

CAPN1 4751 marker, melting curve, and Sanger sequencing confirmation.

Figure 2.

CAPN1 4751 marker, melting curve, and Sanger sequencing confirmation.

Figure 3.

CAST 2959 marker, melting curve, and Sanger sequencing confirmation.

Figure 3.

CAST 2959 marker, melting curve, and Sanger sequencing confirmation.

Figure 4.

Genotype frequency (a) and allele frequency (b) for CAPN1 316 marker. The pie chart on the left illustrates the distribution of genotypes in the studied population: the CC genotype (blue color), the CG genotype (green color), and the GG genotype (red color). The bar graph on the right shows the corresponding allele frequencies: the C allele (white color) and the G allele (black color).

Figure 4.

Genotype frequency (a) and allele frequency (b) for CAPN1 316 marker. The pie chart on the left illustrates the distribution of genotypes in the studied population: the CC genotype (blue color), the CG genotype (green color), and the GG genotype (red color). The bar graph on the right shows the corresponding allele frequencies: the C allele (white color) and the G allele (black color).

Figure 5.

Genotype frequency (a) and allele frequency (b) for CAPN1 4751 marker. The pie chart on the left illustrates the distribution of genotypes in the studied population: the CC genotype (blue color), the CT genotype (green color), and the TT genotype (red color). The bar graph on the right shows the corresponding allele frequencies: the C allele (white color) and the T allele (black color).

Figure 5.

Genotype frequency (a) and allele frequency (b) for CAPN1 4751 marker. The pie chart on the left illustrates the distribution of genotypes in the studied population: the CC genotype (blue color), the CT genotype (green color), and the TT genotype (red color). The bar graph on the right shows the corresponding allele frequencies: the C allele (white color) and the T allele (black color).

Figure 6.

Genotype frequency (a) and allele frequency (b) for CAST 2959 marker. The pie chart on the left illustrates the distribution of genotypes in the studied population: the AA genotype (blue color), the AG genotype (green color), and the GG genotype (red color). The bar graph on the right shows the corresponding allele frequencies: the A allele (white color) and the G allele (black color).

Figure 6.

Genotype frequency (a) and allele frequency (b) for CAST 2959 marker. The pie chart on the left illustrates the distribution of genotypes in the studied population: the AA genotype (blue color), the AG genotype (green color), and the GG genotype (red color). The bar graph on the right shows the corresponding allele frequencies: the A allele (white color) and the G allele (black color).

Figure 7.

Warner-Bratzler shear force (g) distribution for each marker: (a) CAPN1 316 marker; (b) CAPN1 4751 marker; (c) CAST 2959 marker.

Figure 7.

Warner-Bratzler shear force (g) distribution for each marker: (a) CAPN1 316 marker; (b) CAPN1 4751 marker; (c) CAST 2959 marker.

Figure 8.

Effect of each marker on mean adjusted Warner–Bratzler shear force: (a) CAPN1 316 marker; (b) CAPN1 4751 marker; (c) CAST 2959 marker.

Figure 8.

Effect of each marker on mean adjusted Warner–Bratzler shear force: (a) CAPN1 316 marker; (b) CAPN1 4751 marker; (c) CAST 2959 marker.

Figure 9.

Effect of cumulative count of CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751 and CAST 2959 favorable alleles on adjusted Warner–Bratzler shear force. ( ■ = 0 favorable allele, ■ = 1 favorable allele, ■ = 2 favorable alleles, ■ = 3 favorable alleles, ■ = 4 favorable alleles, ■ = 5 favorable alleles).

Figure 9.

Effect of cumulative count of CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751 and CAST 2959 favorable alleles on adjusted Warner–Bratzler shear force. ( ■ = 0 favorable allele, ■ = 1 favorable allele, ■ = 2 favorable alleles, ■ = 3 favorable alleles, ■ = 4 favorable alleles, ■ = 5 favorable alleles).

Table 1.

qPCR primers and product size to detect polymorphism of CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751 and CAST 2959 markers.

Table 1.

qPCR primers and product size to detect polymorphism of CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751 and CAST 2959 markers.

| SNP |

Accession |

Primer |

Annealing Temperature (°C) |

Amplicon (bp) |

CAPN1

316 |

AF 252504 |

Forward |

5’- CAGCTCCTCG

GAGTGGAAC -3’ |

59.60 |

76 |

| Reverse |

5’- AACTCCCCAT

CCTCCATCTT -3’ |

59.60 |

CAPN1

4751 |

AF 248054 |

Forward |

5’- CTGGCATCCT

CCCCTTGACT -3’ |

59.60 |

86 |

| Reverse |

5’- GGGTCACCTG

TAGACGAGGC -3’ |

59.60 |

CAST

2959 |

AF 159246 |

Forward |

5’- CGATGCCTCAC

GTGTTCTTC -3’ |

59.60 |

77 |

| Reverse |

5’- ACATCAAACAC

AGTCCACAAGT -3’ |

59.60 |

Table 2.

qPCR component for reaction setup.

Table 2.

qPCR component for reaction setup.

| qPCR Component |

Volume per reaction |

Concentration per reaction |

| SsoFast™ EvaGreen® Supermix |

10 µL |

1x |

| Forward primer |

0.5 µL |

250 nM |

| Reverse primer |

0.5 µL |

250 nM |

| RNase/DNase-free water |

8 µL |

- |

| DNA template |

1 µL |

20 ng |

| Total volume |

20 µL |

|

Table 3.

Melting Temperature of Genotypes for CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 Markers.

Table 3.

Melting Temperature of Genotypes for CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 Markers.

| Markers |

Genotypes |

Melting Temperature (°C) |

| CAPN1 316 |

CC |

84.20 (83.60*) |

| CG |

84.00 |

| GG |

84.20 (83.80*) |

| CAPN1 4751 |

CC |

85.00 |

| CT |

84.80 |

| TT |

84.40 |

| CAST 2959 |

AA |

77.80 |

| AG |

78.00 |

| GG |

78.40 |

Table 4.

Genotype distribution for CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 combinations.

Table 4.

Genotype distribution for CAPN1 316, CAPN1 4751, and CAST 2959 combinations.

| CAPN1 316/CAPN1 4751/CAST 2959 genotypes combination |

Count |

Frequency |

| GG/CT/AA |

17 |

0.23 |

| GG/CT/AG |

13 |

0.18 |

| CG/CT/AA |

9 |

0.12 |

| CG/CT/AG |

8 |

0.11 |

| CC/CT/AG |

4 |

0.05 |

| CG/CC/AA |

4 |

0.05 |

| GG/CC/AA |

4 |

0.05 |

| GG/TT/AG |

4 |

0.05 |

| CG/CC/AG |

3 |

0.04 |

| CG/TT/AA |

3 |

0.04 |

| GG/TT/AA |

3 |

0.04 |

| CG/TT/GG |

1 |

0.01 |

| GG/TT/GG |

1 |

0.01 |

Table 5.

Observed and expected genotype counts for the CAPN1 316 genotype.

Table 5.

Observed and expected genotype counts for the CAPN1 316 genotype.

| CAPN1 316 genotype |

Observed Count |

Expected Count |

| CC (favorable) |

4 |

4.20 |

| CG |

30 |

29.60 |

| GG (unfavorable) |

52 |

52.20 |

Table 6.

Observed and expected genotype counts for the CAPN1 4751 genotype.

Table 6.

Observed and expected genotype counts for the CAPN1 4751 genotype.

| CAPN1 4751 genotype |

Observed Count |

Expected Count |

| CC (favorable) |

13 |

20.51 |

| CT |

58 |

42.98 |

| TT (unfavorable) |

15 |

22.51 |

Table 7.

Observed and expected genotype counts for the CAST 2959 genotype.

Table 7.

Observed and expected genotype counts for the CAST 2959 genotype.

| CAST 2959 genotype |

Observed Count |

Expected Count |

| AA (favorable) |

43 |

43.98 |

| AG |

37 |

35.04 |

| GG (unfavorable) |

6 |

6.98 |

Table 8.

The summary statistics for Warner-Bratzler shear force.

Table 8.

The summary statistics for Warner-Bratzler shear force.

| Descriptive data |

WBSF (g) |

| Count |

86 |

| Mean WBSF |

3868.63 |

| Standard deviation |

1252.01 |

| Mode |

2480.00 |

| Min |

1604.67 |

| 25% |

2774.17 |

| 50% |

3621.84 |

| 75% |

4914.00 |

| Max |

7220.00 |

Table 9.

Significant marker combination associations with beef tenderness.

Table 9.

Significant marker combination associations with beef tenderness.

| Marker combination and pairwise comparison |

Estimate different |

SE |

p-value |

| CAPN1 316/ CAPN1 4751/ CAST 2959 |

CG/TT/AA - CG/CC/AA |

792.24 |

207.98 |

0.02 |

| CAPN1 316/ CAPN1 4751 |

CG/TT - CG/CC |

523.34 |

172.62 |

0.05 |

| CAPN1 316/ CAPN1 4751 |

CG/TT - CC/CT |

565.89 |

187.73 |

0.06 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).