1. Introduction

Polygonatum odoratum is a perennial herb that is widely used in traditional Chinese medicine for its various health benefits, including immune regulation and anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties [

1,

2]. The rhizomes of

Polygonatum odoratum are highly valued as the primary medicinal component and contain various bioactive components, such as polysaccharides, steroidal glycosides, dipeptides, flavonoids, amino acids, and trace mineral elements. Among these, polysaccharides are considered one of the primary active components responsible for their medicinal effects [

3]. Polysaccharides play crucial roles in plant growth, development, and stress responses, with their contents varying significantly depending on the plant’s growth stage and environmental conditions [

4]. As important bioactive components in

Polygonatum odoratum, polysaccharides exhibit immunomodulatory, antidiabetic, antiaging, antitumor, and antioxidant effects [

5,

6,

7]. These pharmacological properties make them highly promising for applications in modern medicine and health supplements.

Polysaccharides are a class of complex carbohydrate compounds with high molecular weights formed by the dehydration of multiple monosaccharide molecules through condensation reactions. All carbohydrates and their derivatives that meet the definition of macromolecules can be classified as polysaccharides [

8]. On the basis of the types of their constituent units, polysaccharides can be divided into two major categories: homopolysaccharides and heteropolysaccharides. Homopolysaccharides are composed of identical monosaccharide repeating units, such as starch and β-glucan; on the other hand, heteropolysaccharides are composed of two or more different monosaccharides, such as glucuronic acid and pectin.

Polygonatum odoratum polysaccharides are a typical example of heteropolysaccharides and are primarily composed of various monosaccharides, including mannose, galactose, glucose, fructose, rhamnose, arabinose, and galacturonic acid [

9].

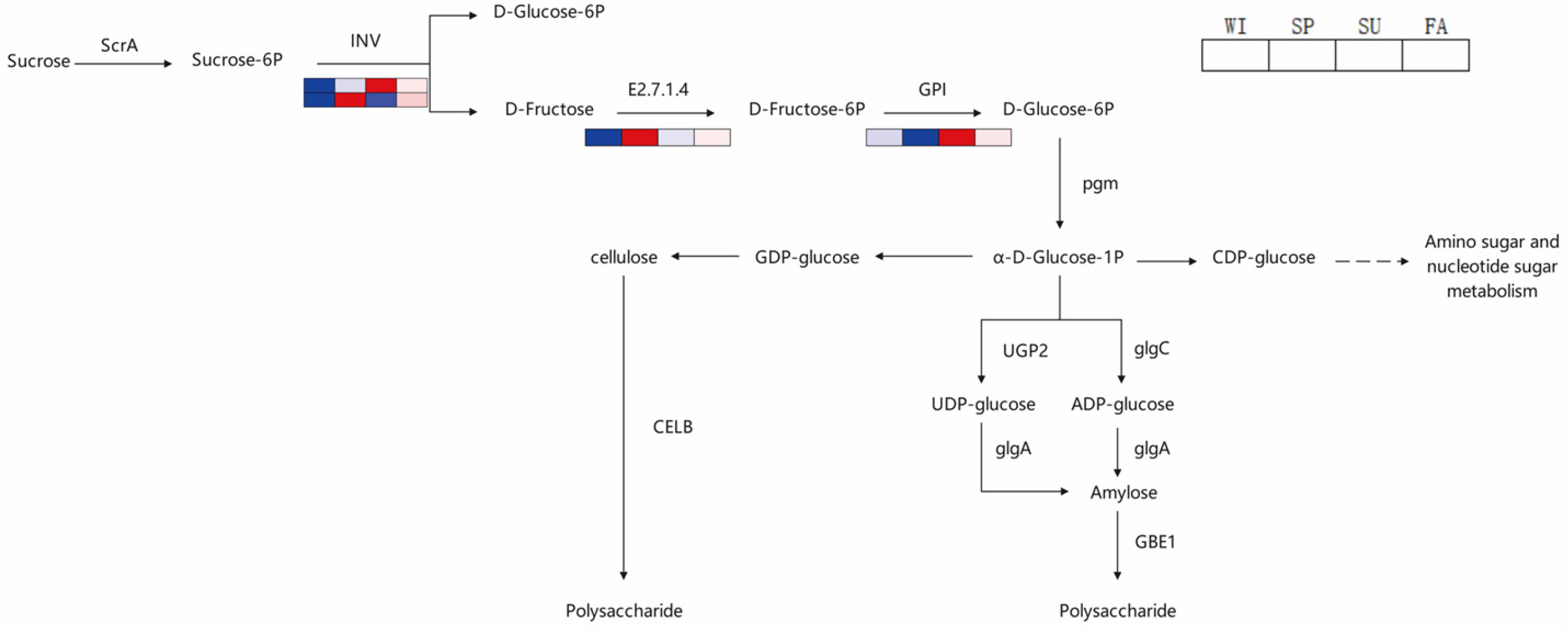

Research has shown that the synthesis and accumulation of

Polygonatum odoratum polysaccharides involve the action of multiple key enzymes, such as UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (UGPase), sucrose phosphorylase (SUS), and glucose transferases (GTs), which play crucial roles in the polysaccharide polymerization process [

10]. Polysaccharide biosynthesis occurs through three main processes [

5,

11]. First, sucrose is converted into glucose-6-phosphate and fructose by β-fructofuranosidase, and fructose is subsequently converted into fructose-6-phosphate by hexokinase and fructokinase [

12]. Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase catalyzes the isomerization of glucose-6-phosphate to glucose-1-phosphate, while UDP-glucose and GDP-mannose are produced from glucose-1-phosphate and fructose-6-phosphate precursors, respectively [

12,

13]. Second, several NDP-sugar interconversion enzymes catalyze the conversion of UDP-Glc or GDP-Man into other NDP sugars [

14]. Finally, different glycosyltransferases remove monosaccharides from sugar nucleotides. The donor is bound to growing polysaccharide polymers, and these repeating units polymerize and output to form plant polysaccharides [

15,

16].

There are various methods for extracting

Polygonatum odoratum polysaccharides, including hot water extraction, enzymatic extraction, and ultrasonic-assisted extraction. The traditional

Polygonatum odoratum processing methods primarily include the “sugar-rubbing” method and steaming and roasting, both of which yield high contents of

Polygonatum odoratum polysaccharides [

17]. The modern processing method employed is ultrafine grinding, which significantly increases the polysaccharide content compared with traditional methods, providing new avenues for the extraction and application of

Polygonatum odoratum polysaccharides. Subsequently, techniques such as ion exchange chromatography and gel permeation chromatography can be used to separate and purify

Polygonatum odoratum polysaccharides further, yielding polysaccharide components with specific molecular weights and structures.

This study aimed to investigate the seasonal dynamic changes in polysaccharide content in

Polygonatum odoratum rhizomes and explore the metabolic and proteomic changes associated with different growth stages. By integrating metabolomics and proteomics methods, we seek to comprehensively understand the changes in polysaccharide biosynthesis and accumulation [

18,

19]. This study also aimed to investigate the synthesis and regulatory mechanisms of secondary metabolites in

Polygonatum odoratum at different growth stages, which may help optimize the harvest time to maximize the yield of polysaccharides and other major active components. To our knowledge, previous studies have rarely utilized multiomics integration methods to investigate changes in secondary metabolites in

Polygonatum odoratum at different growth stages.

The results of this study lay the foundation for future genetic and metabolic engineering research on Polygonatum odoratum and other medicinal plants. By identifying key metabolic pathways and proteins involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis, this study opens new avenues for improving the quality and efficacy of Polygonatum odoratum as a medicinal resource.

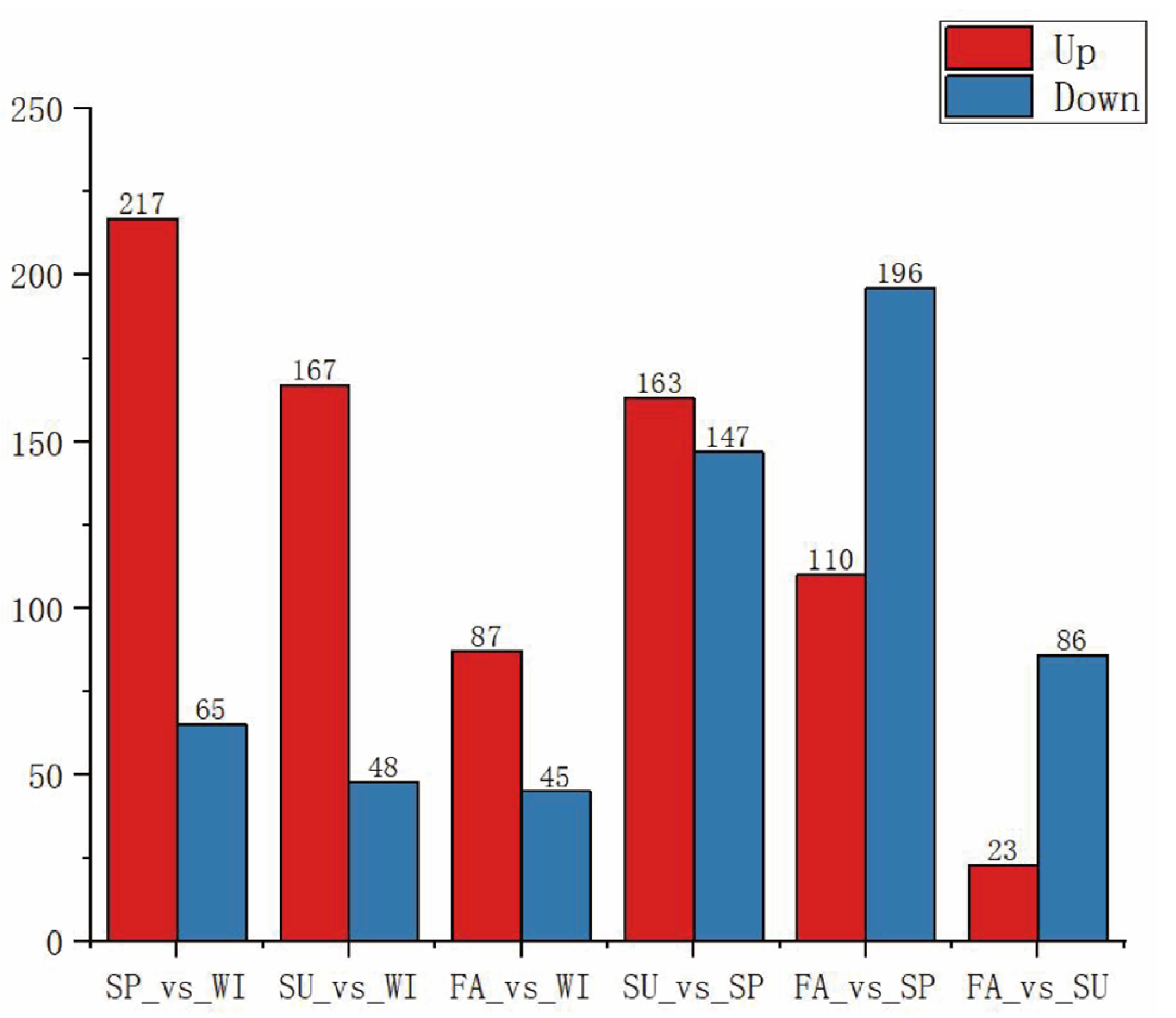

3. Discussion

Polygonatum odoratum, a traditional Chinese herbal medicine, contains polysaccharides in its rhizomes, which are considered one of the primary active components. This study integrated metabolomics and proteomics methods to systematically analyze the seasonal variations in polysaccharide content and their molecular regulatory mechanisms in Polygonatum odoratum rhizomes across different growth seasons. The results not only revealed the key periods and regulatory networks for polysaccharide synthesis in Polygonatum odoratum but also provided an important theoretical basis for the quality control and cultivation of Polygonatum odoratum.

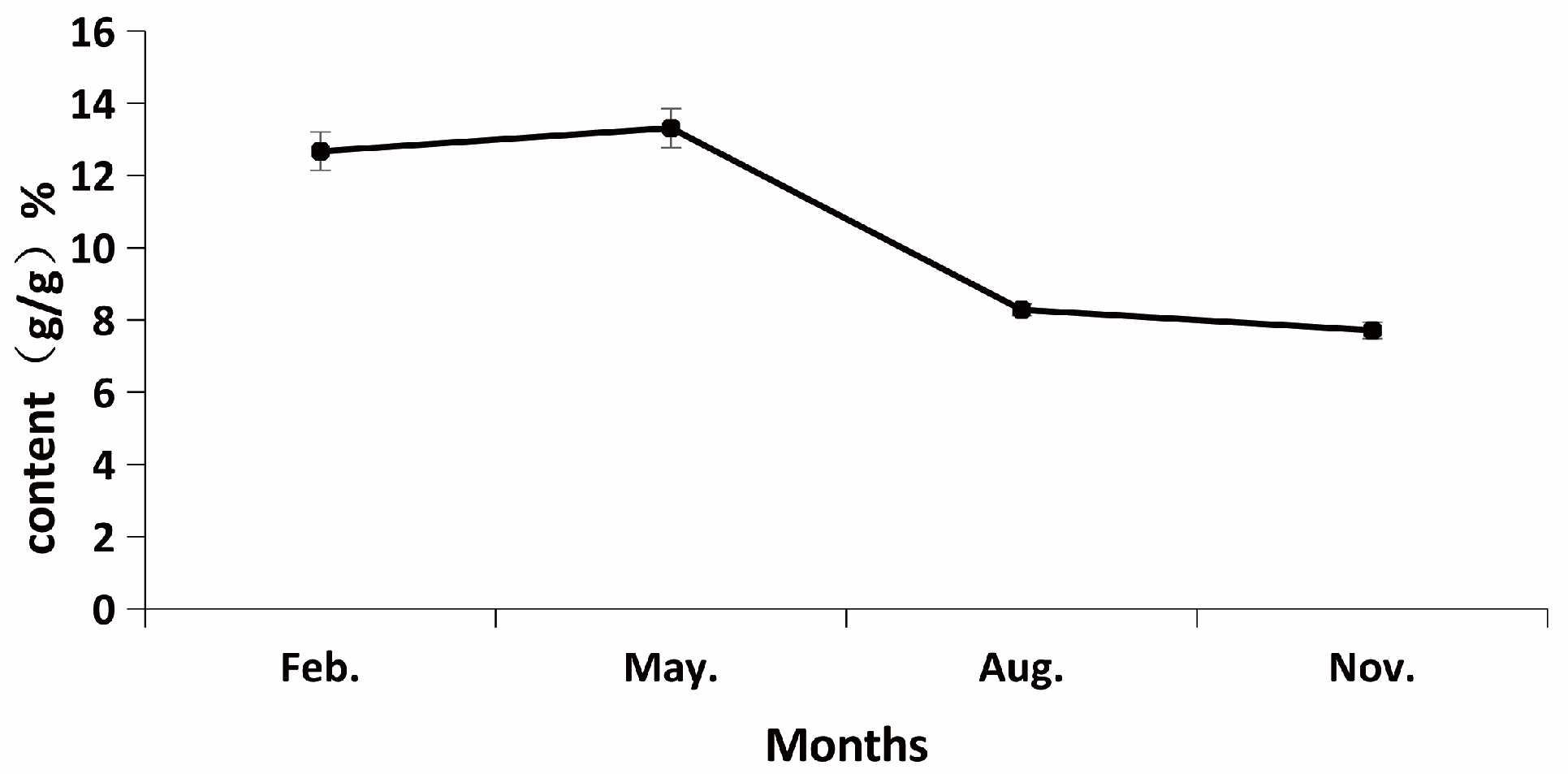

Through systematic seasonal sampling analysis, this study clarified the dynamic changes in polysaccharide content in the rhizomes of

Polygonatum odoratum. The results revealed that the polysaccharide content of

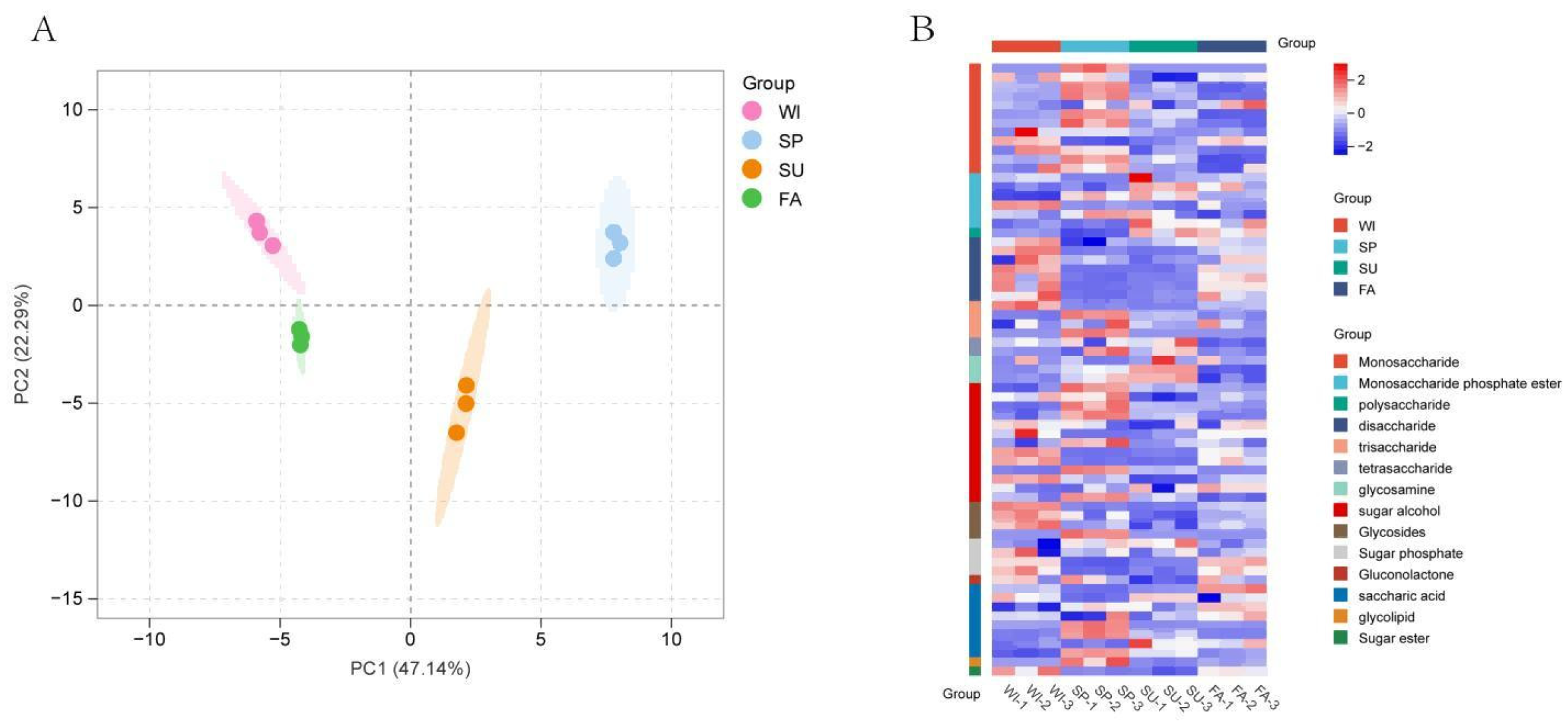

Polygonatum odoratum reached its peak (13.3%) in May (spring), which is consistent with the accumulation patterns of secondary metabolites in many medicinal plants. Spring is the rapid growth period for most plants, during which carbon metabolism is active, providing ample substrates for the synthesis of macromolecules such as polysaccharides. Our metabolomics data indicate that the contents of precursor substances such as monosaccharides and trisaccharides significantly increase at this time (

Figure 2B), which is highly consistent with the increasing trend in polysaccharide content.

Notably, the polysaccharide compositions of the winter (WI) and autumn (FA) samples were highly similar (

Figure 2A), which may be related to the relatively dormant state of the plants during these seasons. The polysaccharide content decreases in the summer (SU) samples, which is likely due to plants allocating more resources to growth metabolism rather than the synthesis of storage compounds under high-temperature conditions. This seasonal variation pattern suggests that seasonal factors should be particularly considered in the cultivation management and harvest timing selection of

Polygonatum odoratum.

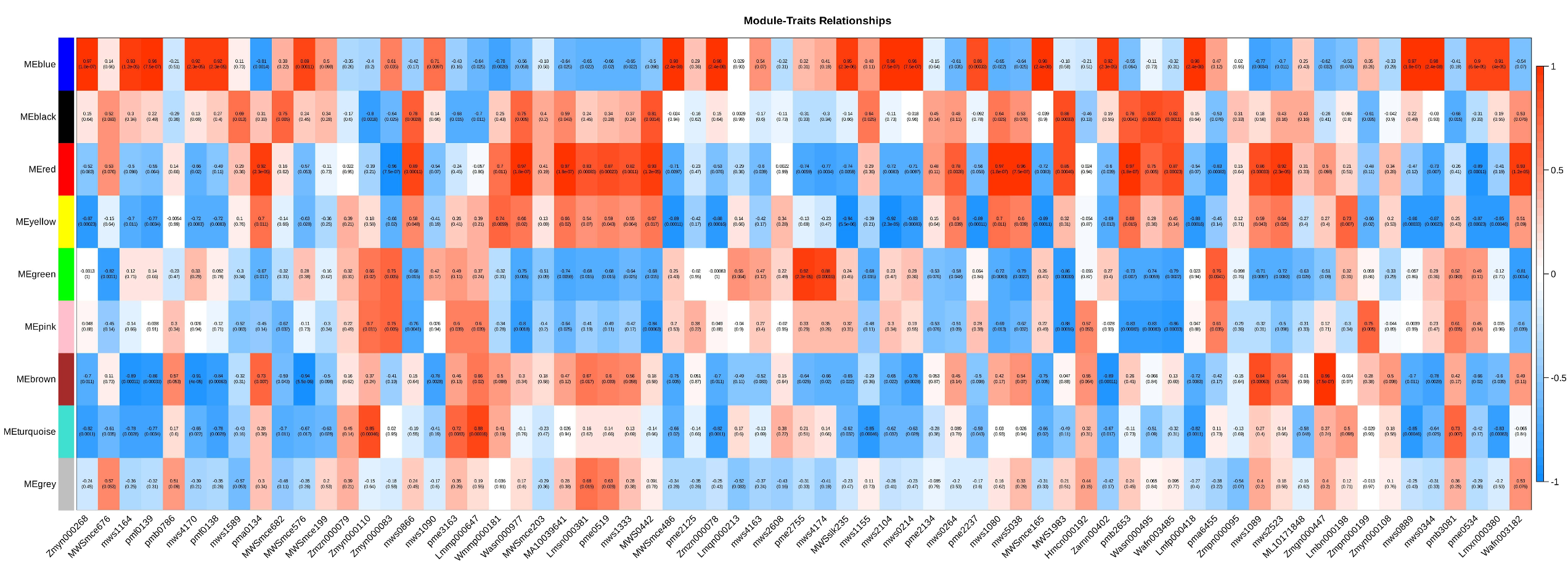

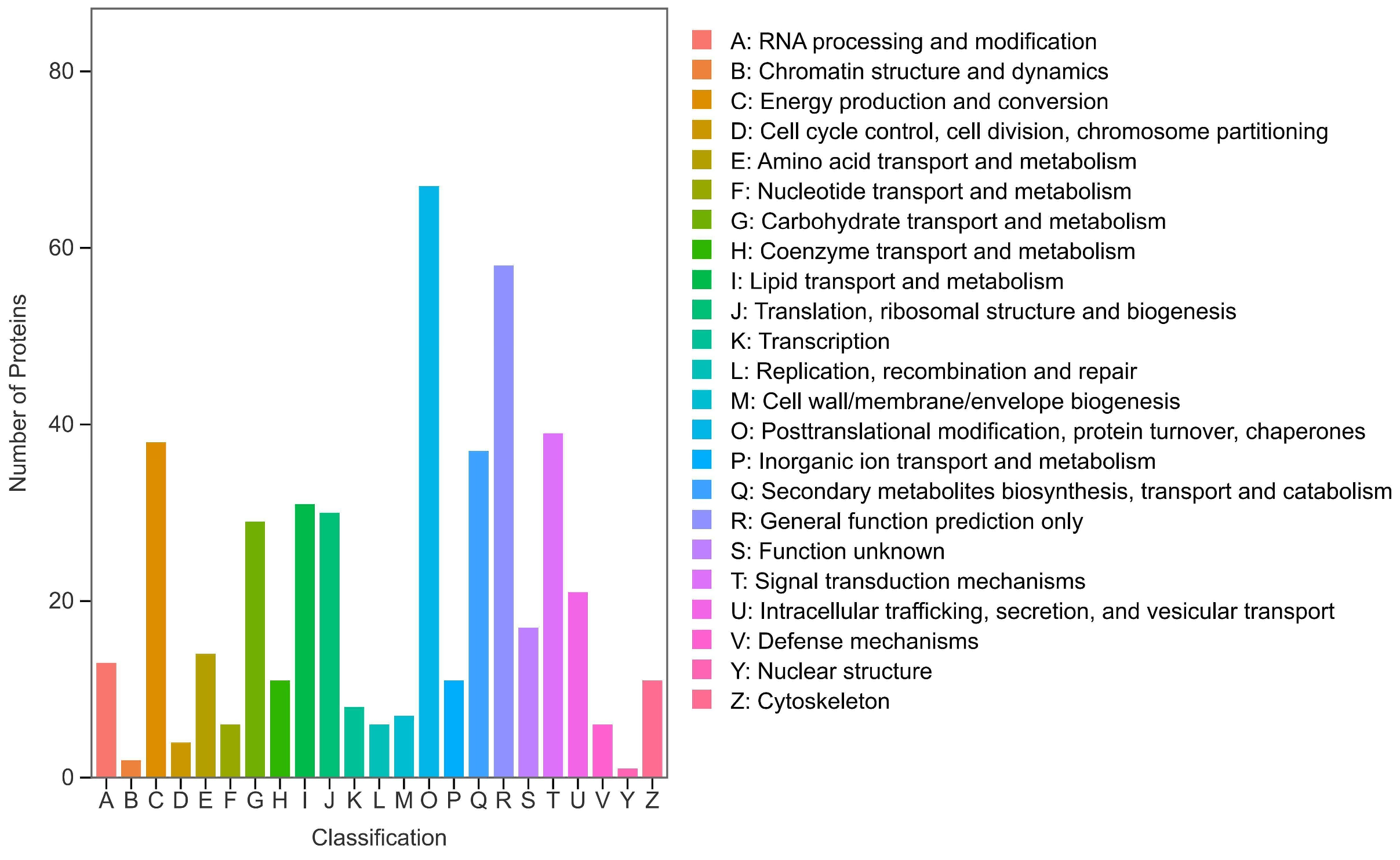

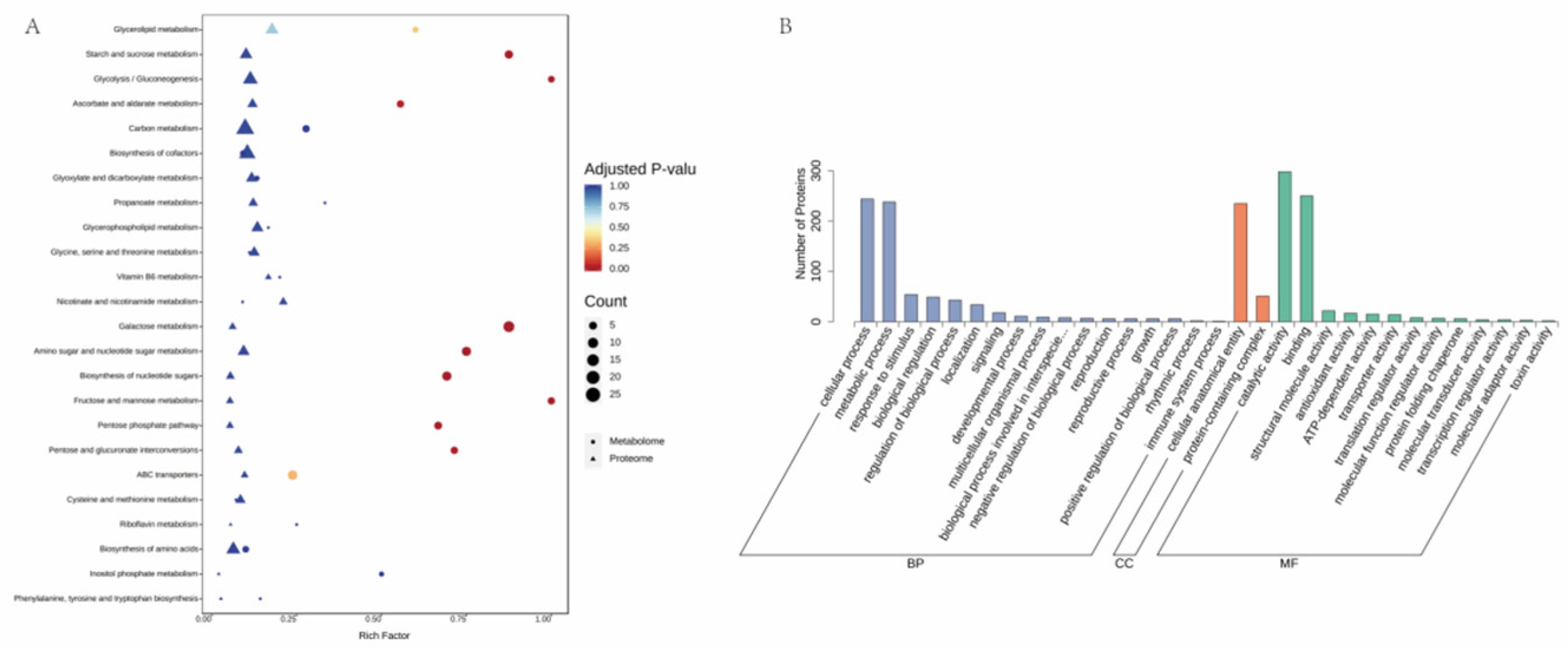

Through WGCNA, we identified a blue module significantly associated with polysaccharide content. The DEPs in this module may play a key role in polysaccharide biosynthesis or regulation, providing clues for understanding the molecular basis of polysaccharide biosynthesis in Polygonatum odoratum.

Among these DEPs, several key enzymes deserve special attention. The first is invertase (INV), which is significantly upregulated in spring (

Figure 5). Invertase catalyzes the hydrolysis of sucrose into glucose and fructose, a step considered one of the rate-limiting steps in polysaccharide synthesis. Our results revealed that the expression level of INV was significantly positively correlated with polysaccharide content (

Figure 8), strongly suggesting its key role in polysaccharide synthesis in

Polygonatum odoratum. INV (invertase), as the key enzyme for sucrose hydrolysis, is upregulated in expression, which may be closely linked to the elongation of photoperiods and rising temperatures in spring. Research indicates that INV activity in various plants is regulated by light signaling pathways (such as those involving phytochrome-interacting factors (PIFs)) and temperature-sensitive transcription factors (such as HSFs). Higher average daily temperatures and abundant light in spring may activate these transcription factors, thereby promoting INV gene expression. This accelerates the conversion of sucrose into glucose and fructose, supplying ample precursors for polysaccharide synthesis. Additionally, increased soil moisture and nitrogen availability in spring may indirectly increase INV activity through hormonal signaling (e.g., gibberellins, auxins), further promoting the allocation of carbon sources toward stored polysaccharides. The second is hexokinase (E2.7.1.4), which promotes the production of UDP-glucose by phosphorylating glucose, and UDP-glucose is a direct precursor for the synthesis of various polysaccharides. Hexokinase (E2.7.1.4) is a key enzyme in hexose phosphorylation, and its springtime upregulation may reflect the high demand for energy and carbon skeletons during the rapid growth phase of

Polygonatum odoratum. Like INV, hexokinase expression is also regulated by environmental factors. For example, in sugarcane and rice, hexokinase expression is significantly influenced by circadian rhythms and temperature fluctuations. The relatively moderate diurnal temperature variation in spring may favor maintaining stable hexokinase activity, thereby ensuring a continuous supply of nucleotide sugars such as UDP-glucose. Notably, the expression pattern of hexokinase in

Polygonatum odoratum differs from that in some temperate medicinal plants, such as Panax ginseng: hexokinase expression peaks in autumn in ginseng, potentially because of its physiological strategy of accumulating storage compounds to withstand severe cold. In contrast,

Polygonatum odoratum tends to rapidly synthesize polysaccharides in spring to support vegetative growth and reproductive preparation. This divergence may reflect species-specific ecological adaptation mechanisms.

Additionally, we identified several enzymes potentially involved in polysaccharide modification, such as glycosyltransferases and glycosidases. The expression of these enzymes also exhibited distinct seasonal variations (

Figure 5), suggesting that they may play important roles in regulating the structural and functional diversity of polysaccharides. These findings provide new directions for understanding the biosynthetic pathways of

Polygonatum odoratum polysaccharides.

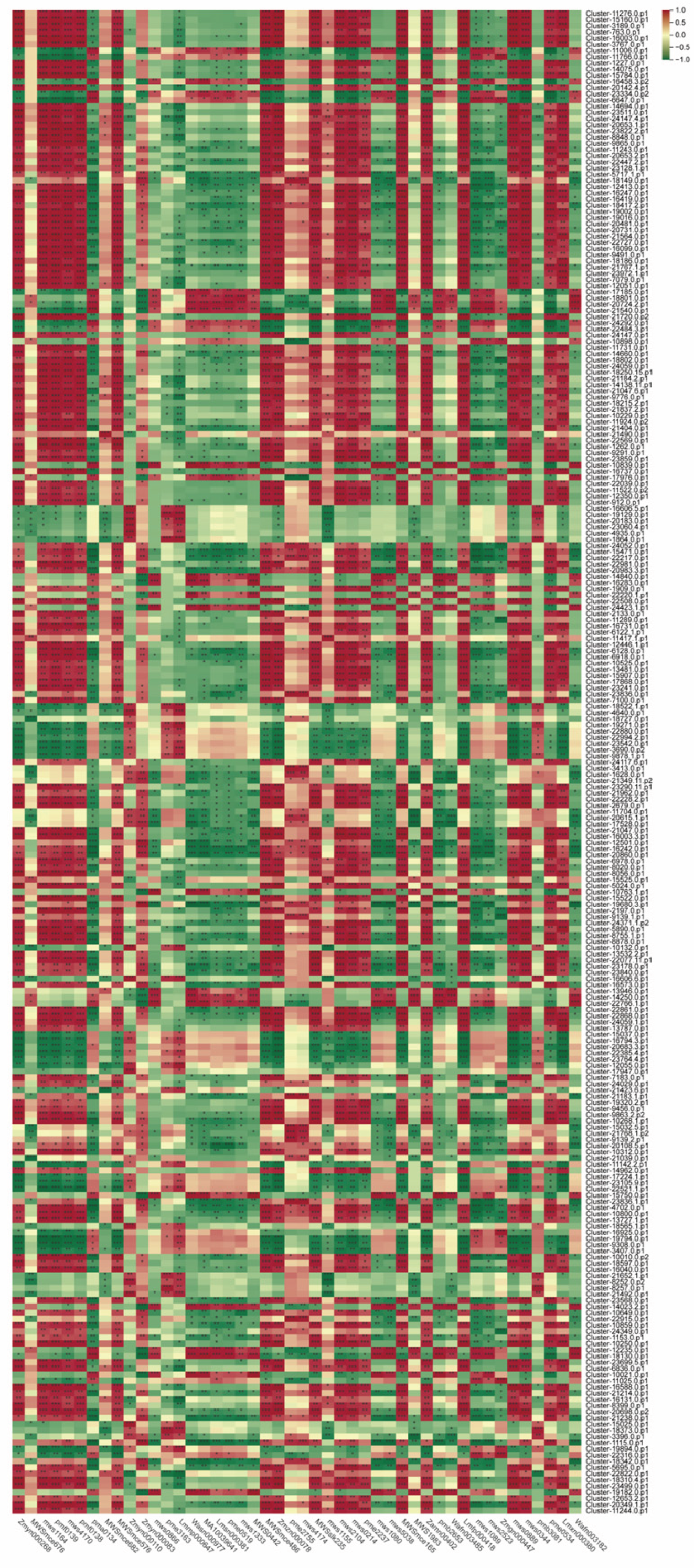

By integrating metabolomics and proteomics data, we constructed a regulatory network for polysaccharide synthesis in

Polygonatum odoratum (

Figure 8). Correlation analysis revealed complex regulatory relationships between DEPs and polysaccharide metabolites (

Figure 8). Most DEPs (e.g., INV and E2.7.1.4) were positively correlated with polysaccharide content, suggesting that these proteins may directly participate in the polysaccharide synthesis process. However, we also observed several interesting phenomena: some DEPs were negatively correlated with polysaccharide content, suggesting that these proteins may be involved in polysaccharide degradation or competitive metabolic pathways; others exhibited dual regulatory effects, implying the existence of more refined feedback regulatory mechanisms. In the network diagram, protein Cluster-15784.0.p1 stands out because of its strong positive correlation with the highest number of polysaccharide metabolites, including various monosaccharide phosphates and oligosaccharides. These findings suggest that this protein may serve as a pivotal hub in the polysaccharide synthesis network of

Polygonatum odoratum. We hypothesize that it may function as a glycosyltransferase with multiple substrate specificities or as a signaling node regulating the activity of several downstream enzymes. This protein could synergistically promote the flow of multiple carbohydrate branch pathways, thereby efficiently directing precursor substances toward polysaccharide synthesis. Therefore, Cluster-15784.0.p1 is considered a highly promising molecular target. Future functional validation through overexpression experiments could identify this gene as a key factor in the breeding of

Polygonatum odoratum varieties with high polysaccharide contents. Conversely, negatively correlated DEPs within the network also carry significant biological implications. These proteins, which are negatively correlated with polysaccharide accumulation, are likely not “detrimental factors” but rather manifestations of the fine-tuned metabolic balance regulation of the plant. These enzymes may initiate polysaccharide degradation—for example, certain glycosidases or amylase enzymes may activate once polysaccharide synthesis reaches a threshold, preventing excessive accumulation or recycling of carbon sources for other physiological activities. or participants in competing pathways. These DEPs may contribute to cell wall component synthesis (cellulose, lignin) or redirect carbon toward other secondary metabolites (flavonoids, saponins), thereby competing with polysaccharide synthesis for shared substrate pools. During spring, while polysaccharide synthesis dominates, mild activation of these competing pathways may aid in cell wall construction and structural maintenance. These genes may also function as regulators of energy and reducing power balance, with some negatively correlated DEPs potentially involved in respiration or oxidative stress responses. When carbohydrate metabolism becomes excessive, the upregulation of these proteins helps maintain intracellular ATP and NADPH homeostasis, preventing metabolic stress caused by accelerated carbon flux.

This complex regulatory network may reflect the adaptive strategies of plants to environmental changes. For example, under suitable growth conditions in spring, plants tend to accumulate stored polysaccharides; under high environmental stress, they may degrade polysaccharides to provide energy and carbon skeletons. This flexible metabolic regulatory capacity is highly important for the survival and accumulation of bioactive components in Polygonatum odoratum.

In terms of molecular mechanisms, the key enzymes identified in this study also have conserved functions in polysaccharide synthesis in other plants. However, certain DEPs unique to Polygonatum odoratum (such as some glycosyltransferase subtypes) may be associated with the unique structure of its polysaccharides. These findings provide new insights into the commonalities and characteristics of polysaccharides in different medicinal plants.

The results of this study have important practical implications. First, spring is the critical period for polysaccharide accumulation in Polygonatum odoratum, providing a scientific basis for determining the optimal harvest period. Second, the identified key DEPs can serve as molecular markers for the breeding and quality evaluation of superior Polygonatum odoratum varieties. Additionally, these findings provide potential targets for enhancing polysaccharide content in Polygonatum odoratum through genetic engineering.

Future research could validate the functions of key DEPs via gene editing technology; investigate the regulatory mechanisms of polysaccharide synthesis influenced by environmental factors (such as temperature, light, and moisture); conduct comparative studies of Polygonatum odoratum from different regions to analyze the impact of geographical variation on polysaccharide synthesis; and explore the relationship between polysaccharide structure and pharmacological activity.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

In a standardized experimental field in Nanling County, Wuhu city, Anhui Province (31°33′N, 118°38′E), the rhizomes of Polygonatum odoratum were planted for three years. Fresh Polygonatum odoratum rhizome samples were collected on February 2, 2022 (winter, abbreviated as WI), May 2 (spring, abbreviated as SP), August 2 (summer, abbreviated as SU), and November 2 (fall, abbreviated as FA). The samples were identified by Professor Fu Hongwei of Zhejiang Sci-tech University of Technology and stored at the College of Life Sciences and Medicine, Zhejiang Sci-tech University. The experimental field was managed with uniform fertilization, irrigation, and pesticide application measures. Polygonatum odoratum rhizomes were harvested in the third year after planting. At each sampling, 20 fresh rhizomes of Polygonatum odoratum were excavated from five fixed points (four corners and the central intersection point) in the experimental field and subjected to uniform processing. The rhizomes were washed with purified water, cut into 0.5 cm pieces, rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C for subsequent experiments.

4.2. Broad-Target Metabolomics Analysis

Biological samples were first dried via a freeze dryer (Scientz-100F) and then ground into powder via an MM 400 grinder (Retsch, China) [

27]. Fifty milligrams of powder (using an MS105DM electronic balance, Sartorius, Germany) was accurately weighed, and 1.2 mL of prechilled 70% methanol aqueous solution containing an internal standard was added to reach -20 °C. The sample was subjected to six vortex treatments followed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was collected and filtered for subsequent UPLC‒MS/MS analysis. Metabolomic analysis was performed by Met-ware Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Metabolite peak area integration was conducted for all the samples via mass spectrometry, and the metabolite peaks were corrected. For group comparisons, differentially abundant metabolites (DAMs) were screened on the basis of P values (P < 0.05) and absolute Log2FC values (|Log2FC| ≥ 1.0). For multigroup comparisons, DAMs were identified on the basis of P values (P < 0.05, via analysis of variance). Additionally, metabolic pathways associated with DAMs were retrieved from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database.

4.3. Determination of Total Polysaccharide Content

The phenol‒sulfuric acid method was used to determine the polysaccharide content in dried

Polygonatum odoratum rhizome samples [

28,

29]. Each sample (February, May, August, and November) was mixed with 100 mL of distilled water, and the dried powder (0.2 g) was extracted twice at 100 °C in boiling distilled water for 1 hour each time. After extraction, the sample was precipitated by adding 95% ethanol (10 mL). The sample was then centrifuged, and the precipitate was dissolved in distilled water (50 mL) containing 4% phenol (1 mL) and sulfuric acid (7 mL). The absorbance of each sample was measured at 490 nm via a UV spectrophotometer (JASCO Corporation, Japan). The polysaccharide content was determined via three biological replicates.

4.4. Proteomic Analysis

Proteins were extracted from the samples via the acetone precipitation method. The specific steps were as follows: the samples were ground into a powder in liquid nitrogen and homogenized, after which an extraction mixture containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was added. Next, the protein sample was boiled for 15 minutes, sonicated in an ice bath for 10 minutes to lyse the cells, and centrifuged to obtain a clear protein mixture. Four times the volume of frozen acetone was added to the protein mixture, which was then incubated at -20 °C overnight to precipitate the proteins. The precipitate was then collected by centrifugation at 4 °C. The precipitate was washed with cold acetone and dissolved in 8 M urea. Finally, the protein concentration was determined via the BCA method according to the kit instructions.

For each sample, an equal amount of protein was used for trypsin digestion. 8 M urea was added to the supernatant to a volume of 200 µL, which was then treated with 10 mM DTT at 37 °C for 45 minutes for reduction, followed by treatment with 50 mM iodacetamide (IAM) at room temperature in the dark for 15 minutes for alkylation. Next, four volumes of ice-cold acetone were added, and the peptide segments were precipitated at -20 °C for 2 hours. After centrifugation, the protein precipitate was air-dried and resuspended in 200 µL of 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate solution. Three microliters of trypsin (trypsin-to-protein mass ratio of 1:50, Promega) was added, and the mixture was digested overnight at 37 °C. After digestion, the peptide segments were desalted via a C18 column (IonOpticks, Australia), dried in a vacuum concentrator, concentrated via vacuum centrifugation, and finally dissolved in 0.1% (v/v) formic acid solution.

4.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

WGCNA: WGCNA was performed on differentially expressed metabolites and proteins to identify coexpressed gene modules and explore the associations between gene networks and the phenotype of interest, as well as the core genes in the network [

30]. WGCNA was conducted via MetWare Cloud (a free online data analysis platform (

https://cloud.metware.cn/)).

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis: Bioinformatics analysis of differentially expressed metabolites and proteins on the basis of the KEGG biological pathway database to understand the biological pathways enriched by metabolites and proteins [

27,

31,

32,

33].

GO enrichment analysis: Identification of significantly enriched biological functions, molecular activities, or cellular localizations from DEPs to help explain the potential roles of these genes [

33,

34,

35].

PCA: Principal component analysis was performed on the DAMs and DEPs to understand the variation rates and differences in each principal component [

36,

37]. PCA was conducted via the MetWare Cloud.

5. Conclusions

Through integrated metabolomics and proteomics analyses, this study systematically revealed the seasonal patterns and molecular regulatory mechanisms underlying polysaccharide accumulation in Polygonatum odoratum rhizomes. The results confirmed that spring (May) was the peak accumulation period (reaching 13.3% content), with a significant decline in summer, whereas autumn and winter presented similar polysaccharide compositions. Metabolomic data revealed significant accumulation of precursor substances such as monosaccharides and trisaccharides in spring, providing raw materials for polysaccharide synthesis. Proteomic analysis further revealed that key enzymes such as invertase (INV) and hexokinase (E2.7.1.4) were significantly upregulated in spring, and their expression levels were highly positively correlated with polysaccharide content.

WGCNA revealed a blue module highly positively correlated with polysaccharide content, where hub proteins (e.g., Cluster-15784.0.p1) may play central roles in the polysaccharide synthesis network. This module was significantly enriched in pathways related to “starch and sucrose metabolism.” This study also revealed that some DEPs were negatively correlated with polysaccharide accumulation, suggesting potential regulatory mechanisms involving metabolic balance and resource reallocation during seasonal growth.

These findings provide scientific support for the rationality of spring harvesting of Polygonatum odoratum and offer potential molecular targets for breeding high-polysaccharide varieties. Future research should further elucidate the regulatory network of polysaccharide synthesis in Polygonatum odoratum through gene functional validation and environmental regulation studies.